Tibet (1912–1951) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Tibet was a ''de facto'' independent state between the collapse of the

Tibet came under the rule of the

Tibet came under the rule of the

"Tibet Facts No.17: British Relations with Tibet"

. Tibet, however, altered its position on the McMahon Line in the 1940s. In late 1947, the Tibetan government wrote a note presented to the newly independent Indian Ministry of External Affairs laying claims to Tibetan districts south of the McMahon Line. According to

Since the expulsion of the

Since the expulsion of the

—but the Tibetans claim that they rejected China's proposal that Tibet should be a part of China, and in turn demanded the return of territories east of the Drichu (

In 1935, Lhamo Dhondup was born in Amdo in eastern Tibet and recognized by all concerned as the incarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama. On 26 January 1940, the Regent

In 1935, Lhamo Dhondup was born in Amdo in eastern Tibet and recognized by all concerned as the incarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama. On 26 January 1940, the Regent

"Self-Determination in Tibet: The Politics of Remedies"

. Under orders from the In 1947, Tibet sent a delegation to the

In 1947, Tibet sent a delegation to the  In 1947–49, Lhasa sent a trade mission led by Finance Minister

In 1947–49, Lhasa sent a trade mission led by Finance Minister

After the 13th Dalai Lama had assumed full control over Tibet in the 1910s, he began to build up the

After the 13th Dalai Lama had assumed full control over Tibet in the 1910s, he began to build up the

File:Stamp-tibet-1912-50-green.jpg, Snow lion stamp issued in 1912

File:Tibet Stamp 1912 face value two annas.jpg, Snow lion stamp issued in 1912

File:Tibet Stamp 1912 face value three annas.jpg, Snow lion stamp issued in 1912

File:Tibet stamp 1912 face value four annas.jpg, Snow lion stamp issued in 1912

File:Tibet stamp 1912 face value one trangka.jpg, Snow lion stamp issued in 1912

File:Tibet stamp 1912 face value one sang.jpg, Snow lion stamp issued in 1912

File:1920tibet4t.jpg, Snow lion stamp issued in 1920

File:Tibet stamp 1933.jpg, Snow lion stamps issued in 1933

Tibet created its own postal service in 1912. It printed its first postage stamps in Lhasa and issued them in 1912. It issued telegraph stamps in 1950.

The division of China into military cliques kept China divided, and the 13th Dalai Lama ruled but his reign was marked with border conflicts with Han Chinese and Muslim warlords, which the Tibetans lost most of the time. At that time, the government of Tibet controlled all of

The division of China into military cliques kept China divided, and the 13th Dalai Lama ruled but his reign was marked with border conflicts with Han Chinese and Muslim warlords, which the Tibetans lost most of the time. At that time, the government of Tibet controlled all of

The Tibetan government issued banknotes and coins.

The Tibetan government issued banknotes and coins.

Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

-led Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in 1912 and its annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

by the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

in 1951.

;

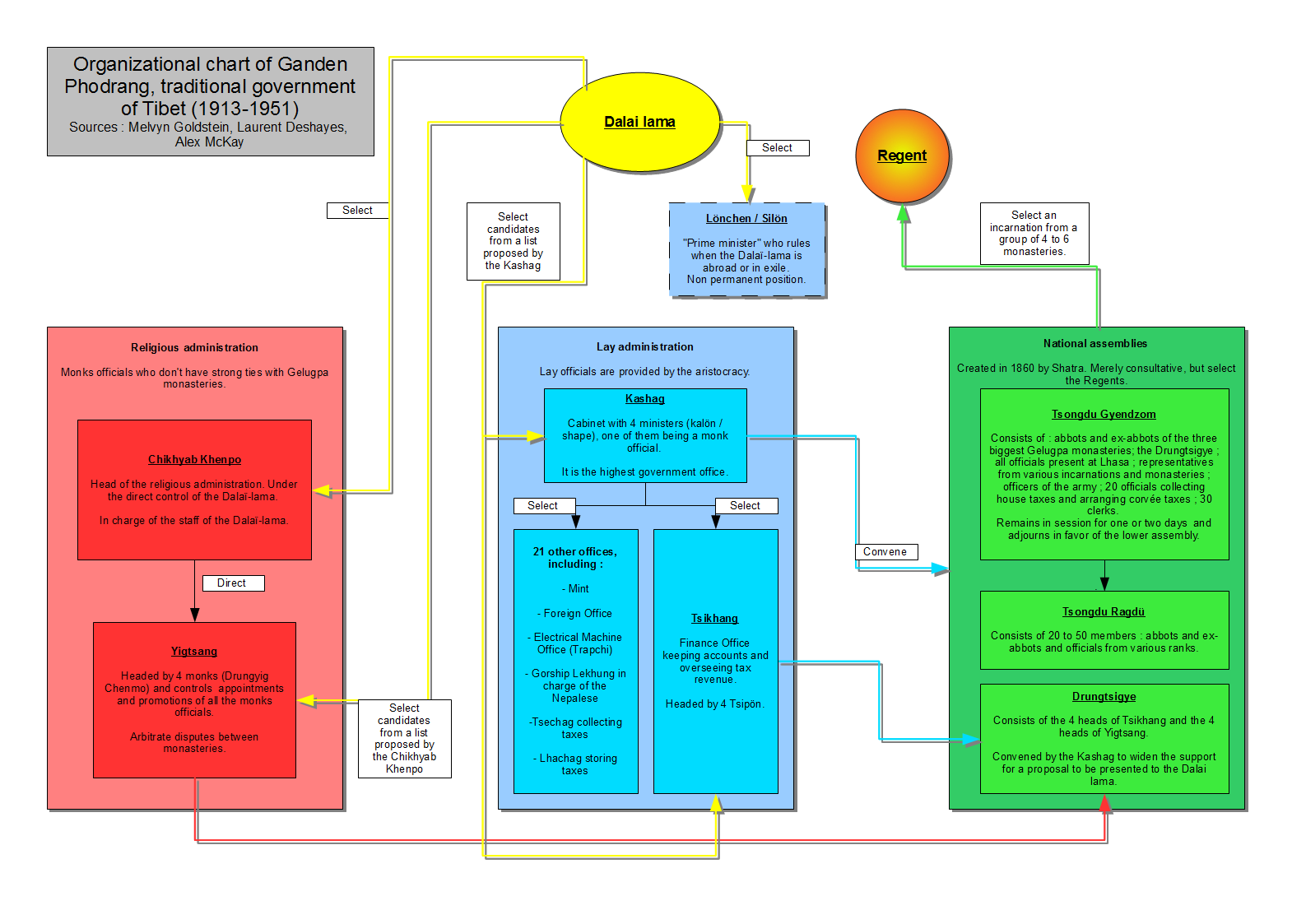

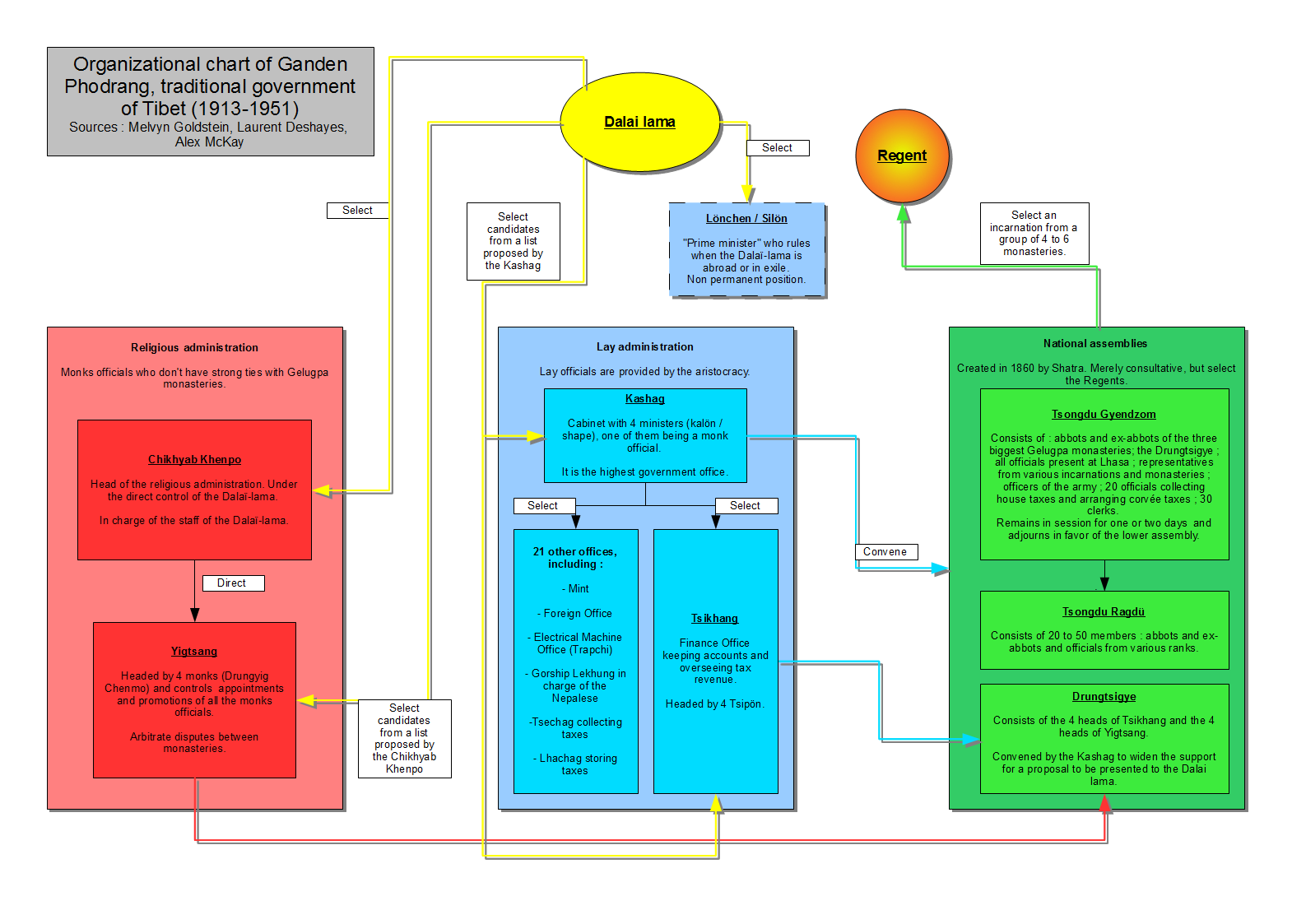

The Tibetan Ganden Phodrang

The Ganden Phodrang or Ganden Podrang (; ) was the Tibetan system of government established by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1642; it operated in Tibet until the 1950s. Lhasa became the capital of Tibet again early in this period, after the Oirat lo ...

regime was a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its in ...

of the Qing dynasty until 1912. When the provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or ...

of the Republic of China was formed, it received an imperial edict giving it control over all the territories of the Qing dynasty. However, it was unable to assert any authority in Tibet. The Dalai Lama declared that Tibet's relationship with China ended with the fall of the Qing dynasty and proclaimed independence. Tibet and Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was the name of a territory in the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China from 1691 to 1911. It corresponds to the modern-day independent state of Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. The historical region gain ...

also signed a treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal per ...

proclaiming mutual recognition of their independence from China. With its proclamation of independence and conduct of its own internal and external affairs in this period, Tibet is regarded as a "''de facto'' independent state" as per international law, although its independence was not formally recognized by any foreign power.

After the 13th Dalai Lama's death in 1933, a condolence mission sent to Lhasa by the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

-ruled Nationalist government to start negotiations about Tibet's status was allowed to open an office and remain there, although no agreement was reached.

The era ended after the Nationalist government of the Republic of China lost the civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

against the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

, when the People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the China, People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five Military branch, service branches: the People's ...

entered Tibet in 1950 and the Seventeen Point Agreement was signed to reaffirm China's sovereignty over Tibet the following year.

History

Fall of Qing dynasty (1911–1912)

Tibet came under the rule of the

Tibet came under the rule of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

of China in 1720 after the Qing expelled the forces of the Dzungar Khanate

The Dzungar Khanate, also written as the Zunghar Khanate, was an Inner Asian khanate of Oirat Mongol origin. At its greatest extent, it covered an area from southern Siberia in the north to present-day Kyrgyzstan in the south, and from t ...

. But by the end of the 19th century, the Chinese authority in Tibet was no more than symbolic.: "From 792on, the Qing dynasty became increasingly preoccupied with problems in the interior, and court officials in Peking found it less and less easy to intervene in Tibetan affairs.... by the second half of the nineteenth century, the Qing ambans, who represented the Qing emperor and Qing authority, could do little more than exercise ritualistic and symbolic influence." Following the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of ...

in 1911–1912, Tibetan militia launched a surprise attack on the Qing garrison stationed in Tibet after the Xinhai Lhasa turmoil. After the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the Qing officials in Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhasa ...

were then forced to sign the "Three Point Agreement" for the surrender and expulsion of Qing forces in central Tibet. In early 1912, the Government of the Republic of China

The Government of the Republic of China, is the national government of the Republic of China whose ''de facto'' territory currently consists of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other island groups in the " free area". Governed by the ...

replaced the Qing dynasty as the government of China and the new republic asserted its sovereignty over all the territories of the previous dynasty, which included 22 Chinese provinces

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman '' provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions ou ...

, Tibet and Outer Mongolia

Outer Mongolia was the name of a territory in the Manchu people, Manchu-led Qing dynasty of China from 1691 to 1911. It corresponds to the modern-day independent state of Mongolia and the Russian republic of Tuva. The historical region gain ...

. This claim was provided for in the Imperial Edict of the Abdication of the Qing Emperor

The Imperial Edict of the Abdication of the Qing Emperor (; lit. "Xuantong Emperor's Abdication Edict") was an official decree issued by the Empress Dowager Longyu on behalf of the six-year-old Xuantong Emperor, the last emperor of the Qing d ...

signed by the Empress Dowager Longyu

Jingfen (; 28 January 1868 – 22 February 1913), of the Manchu Bordered Yellow Banner Yehe Nara clan, was the wife and empress consort of Zaitian, the Guangxu Emperor. She was Empress consort of Qing from 1889 until her husband's death in 19 ...

on behalf of the six-year-old Xuantong Emperor

Aisin-Gioro Puyi (; 7 February 1906 – 17 October 1967), courtesy name Yaozhi (曜之), was the last emperor of China as the eleventh and final Qing dynasty monarch. He became emperor at the age of two in 1908, but was forced to abdicate on 1 ...

: "...the continued territorial integrity of the lands of the five races, Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

, Han, Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

, Hui, and Tibetan

Tibetan may mean:

* of, from, or related to Tibet

* Tibetan people, an ethnic group

* Tibetan language:

** Classical Tibetan, the classical language used also as a contemporary written standard

** Standard Tibetan, the most widely used spoken diale ...

into one great Republic of China" (...). The Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China

After victory in the Xinhai Revolution, the Nanjing Provisional Government of the Republic of China, led by Sun Yat-sen, framed the Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China (, 1912), which was an outline of basic regulations with the qua ...

adopted in 1912 specifically established frontier regions of the new republic, including Tibet, as integral parts of the state.

Following the establishment of the new Republic, China's provisional President Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 1859 – 6 June 1916) was a Chinese military and government official who rose to power during the late Qing dynasty and eventually ended the Qing dynasty rule of China in 1912, later becoming the Emperor of China. H ...

sent a telegram to the 13th Dalai Lama, restoring his earlier titles. The Dalai Lama spurned these titles, replying that he "intended to exercise both temporal and ecclesiastical rule in Tibet." In 1913, the Dalai Lama, who had fled to India when the Qing sent a military expedition to establish direct Chinese rule over Tibet in 1910, returned to Lhasa and issued a proclamation that stated that the relationship between the Chinese emperor and Tibet "had been that of patron and priest and had not been based on the subordination of one to the other." "We are a small, religious, and independent nation," the proclamation stated.

In January 1913, Agvan Dorzhiev

Agvan Lobsan Dorzhiev, also Agvan Dorjiev or Dorjieff and Agvaandorj (russian: link=no, Агван Лобсан Доржиев, bua, Доржиин Агбан, bo, ངག་དབང་བློ་བཟང་; 1853, Khara-Shibir ulus, — Ja ...

and three other Tibetan representativesUdo B. Barkmann, ''Geschichte der Mongolei'', Bonn 1999, p380ff signed a treaty between Tibet and Mongolia in Urga, proclaiming mutual recognition and their independence from China. The British diplomat Charles Bell wrote that the 13th Dalai Lama told him that he had not authorized Agvan Dorzhiev to conclude any treaties on behalf of Tibet. Because the text was not published, some initially doubted the existence of the treaty, but the Mongolian text was published by the Mongolian Academy of Sciences

The Mongolian Academy of Sciences (, ''Mongol ulsyn Shinjlekh ukhaany Akademi'') is Mongolia's first centre of modern sciences. It came into being in 1921 when the government of newly

independent Mongolia issued a resolution declaring the establ ...

in 1982.

Simla Convention (1914)

In 1913–1914, a conference was held inSimla

Shimla (; ; also known as Simla, the official name until 1972) is the capital and the largest city of the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh. In 1864, Shimla was declared as the summer capital of British India. After independence, th ...

between the UK, Tibet, and the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

. The British suggested dividing Tibetan-inhabited areas into an Outer and an Inner Tibet (on the model of an earlier agreement between China and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

over Mongolia). Outer Tibet, approximately the same area as the modern Tibet Autonomous Region

The Tibet Autonomous Region or Xizang Autonomous Region, often shortened to Tibet or Xizang, is a province-level autonomous region of the People's Republic of China in Southwest China. It was overlayed on the traditional Tibetan regions ...

, would be autonomous under Chinese suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is ca ...

. In this area, China would refrain from "interference in the administration." In Inner Tibet, consisting of eastern Kham

Kham (; )

is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being Amdo in the northeast, and Ü-Tsang in central Tibet. The original residents of Kham are called Khampas (), and were governed locally by chieftains and monasteries. Kham ...

and Amdo

Amdo ( �am˥˥.to˥˥ ) is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being U-Tsang in the west and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Amdo is also the bi ...

, China would have rights of administration and Lhasa would retain control of religious institutions.

When negotiations broke down over the specific boundary between Inner and Outer Tibet, the boundary of Tibet defined in the Convention also included what came to be known as the McMahon Line

The McMahon Line is the boundary between Tibet and British India as agreed in the maps and notes exchanged by the respective plenipotentiaries on 24–25 March 1914 at Delhi, as part of the 1914 Simla Convention.

The line delimited the r ...

, which delineated the Tibet-India border, in the Assam Himalayan region. The boundary included in India the Tawang tract, which had been under indirect administration of Tibet via the control of the Tawang monastery.

The Simla Convention was initialled by all three delegations, but was immediately rejected by Beijing because of dissatisfaction with the boundary between Outer and Inner Tibet. McMahon and the Tibetans then signed the document as a bilateral accord with a note denying China any of the rights under the Convention until it signed. The British Government initially rejected McMahon's bilateral accord as being incompatible with the 1907 Anglo-Russian Convention.

The 1907 Anglo-Russian Treaty, which had earlier caused the British to question the validity of Simla, was renounced by the Russians in 1917 and by the Russians and British jointly in 1921.Free Tibet Campaign"Tibet Facts No.17: British Relations with Tibet"

. Tibet, however, altered its position on the McMahon Line in the 1940s. In late 1947, the Tibetan government wrote a note presented to the newly independent Indian Ministry of External Affairs laying claims to Tibetan districts south of the McMahon Line. According to

Alastair Lamb

Alastair Lamb is a diplomatic historian who has authored several books on the Sino-Indian border dispute and the Indo-Pakistani dispute over Kashmir. He has also worked in archaeology and ethnography in Asia and Africa.

Career

Alastair Lam ...

, by refusing to sign the Simla documents, the Chinese Government had escaped giving any recognition to the McMahon Line.

After the death of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1933

Since the expulsion of the

Since the expulsion of the Amban

Amban ( Manchu and Mongol: ''Amban'', Tibetan: ་''am ben'', , Uighur:''am ben'') is a Manchu language term meaning "high official", corresponding to a number of different official titles in the imperial government of Qing China. For insta ...

from Tibet in 1912, communication between Tibet and China had taken place only with the British as mediator. Direct communications resumed after the 13th Dalai Lama's death in December 1933, when China sent a "condolence mission" to Lhasa headed by General Huang Musong Huang or Hwang may refer to:

Location

* Huang County, former county in Shandong, China, current Longkou City

* Yellow River, or Huang River, in China

* Huangshan, mountain range in Anhui, China

* Huang (state), state in ancient China.

* Hwang Riv ...

.

Soon after the 13th Dalai Lama died, according to some accounts, the Kashag

The Kashag (; ), was the governing council of Tibet during the rule of the Qing dynasty and post-Qing period until the 1950s. It was created in 1721, and set by Qianlong Emperor in 1751 for the Ganden Phodrang in the 13-Article Ordinance for ...

reaffirmed its 1914 position that Tibet remained nominally part of China, provided Tibet could manage its own political affairs. In his essay ''Hidden Tibet: History of Independence and Occupation'' published by the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives

The Library of Tibetan Works and Archives (LTWA) is a Tibetan library in Dharamshala, India. The library was founded by Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama on 11 June 1970, and is considered one of the most important libraries and institutions o ...

at Dharamsala, S.L. Kuzmin cited several sources indicating that the Tibetan government had not declared Tibet a part of China, despite an intimation of Chinese sovereignty made by the Kuomintang government. Since 1912 Tibet had been ''de facto'' independent of Chinese control, but on other occasions it had indicated willingness to accept nominal subordinate status as a part of China, provided that Tibetan internal systems were left untouched, and provided China relinquished control over a number of important ethnic Tibetan areas in Kham and Amdo. In support of claims that China's rule over Tibet was not interrupted, China argues that official documents showed that the National Assembly of China and both chambers of parliament had Tibetan members, whose names had been preserved all along.

China was then permitted to establish an office in Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhasa ...

, staffed by the Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission

The Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission (MTAC) was a ministry-level commission of the Executive Yuan in the Republic of China. It was disbanded on 15 September 2017.

History

The first model was created during the Qing dynasty in 1636 ...

and headed by Wu Zhongxin (Wu Chung-hsin), the commission's director of Tibetan Affairs,

which Chinese sources claim was an administrative bodyTibet during the Republic of China (1912–1949)—but the Tibetans claim that they rejected China's proposal that Tibet should be a part of China, and in turn demanded the return of territories east of the Drichu (

Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

). In response to the establishment of a Chinese office in Lhasa, the British obtained similar permission and set up their own office there.

The 1934 Khamba Rebellion led by Pandastang Togbye and Pandatsang Rapga

Pandatsang Rapga (; 1902–1974) was a Khamba revolutionary during the first half of the 20th century in Tibet. He was pro-Kuomintang and pro-Republic of China, anti-feudal, anti-communist. He believed in overthrowing the Dalai Lama's feudal regim ...

broke out against the Tibetan Government during this time, with the Pandatsang family leading Khamba tribesmen against the Tibetan Army

The Tibetan Army () was the military force of Tibet after its ''de facto'' independence in 1912 until the 1950s. As a ground army modernised with the assistance of British training and equipment, it served as the ''de facto'' armed forces of th ...

.

1930s to 1949

In 1935, Lhamo Dhondup was born in Amdo in eastern Tibet and recognized by all concerned as the incarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama. On 26 January 1940, the Regent

In 1935, Lhamo Dhondup was born in Amdo in eastern Tibet and recognized by all concerned as the incarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama. On 26 January 1940, the Regent Reting Rinpoche

Reting Rinpoche () was a title held by abbots of Reting Monastery, a Buddhist monastery in central Tibet.

History of the lineage

Historically, the Reting Rinpoche has occasionally acted as the selector of the new Dalai Lama incarnation. It is f ...

requested the Chinese Government to exempt Lhamo Dhondup from lot-drawing process using Golden Urn

The Golden Urn refers to a method for selecting Tibetan reincarnations by drawing lots or tally sticks from a Golden Urn introduced by the Qing dynasty of China in 1793. After the Sino-Nepalese War, the Qianlong Emperor promulgated the 29-Article ...

to become the 14th Dalai Lama, and the Chinese government agreed. After a ransom of 400,000 silver dragons had been paid by Lhasa to the Hui Muslim warlord Ma Bufang

Ma Bufang (1903 – 31 July 1975) (, Xiao'erjing: ) was a prominent Muslim Ma clique warlord in China during the Republic of China era, ruling the province of Qinghai. His rank was Lieutenant-general.

General Ma started an industrialization pro ...

, who ruled Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

(Chinghai) from Xining, Ma Bufang released him to travel to Lhasa in 1939. He was then enthroned by the Ganden Phodrang government at the Potala Palace on the Tibetan New Year.

The People's Republic of China claims that the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

Government 'ratified' the current 14th Dalai Lama, and that Kuomintang representative General Wu Zhongxin presided over the ceremony; both the ratification order of February 1940 and the documentary film of the ceremony still exist intact. Wu Zhongxin (along with other foreign representatives) was present at the ceremony.

The British Representative Sir Basil Gould

Sir Basil John Gould, CMG, CIE (29 December 1883 – 27 December 1956) was a British Political Officer in Sikkim, Bhutan and Tibet from 1935 to 1945.

Biography

Known as "B.J.", Gould was born in Worcester Park, Surrey, to Charles and Mary ...

who was present at the ceremony disputes the Chinese claim to have presided over it. He criticised the Chinese account as follows:

Tibetan author Nyima Gyaincain wrote that based on Tibetan tradition, there was no such thing as presiding over an event, and wrote that the word "主持 (preside or organize)" was used in many places in communication documents. The meaning of the word was different than what we understand today. He added that Wu Zhongxin spent a lot of time and energy on the event, his effect of presiding over or organizing the event was very obvious.

In 1942, the U.S. government told the government of Chiang Kai-shek that it had never disputed Chinese claims to Tibet. In 1944, the USA War Department produced a series of seven documentary films on Why We Fight

''Why We Fight'' is a series of seven propaganda films produced by the US Department of War from 1942 to 1945, during World War II. It was originally written for American soldiers to help them understand why the United States was involved in the ...

; in the sixth series, The Battle of China

''The Battle of China'' (1944) was the sixth film of Frank Capra's ''Why We Fight'' propaganda film series.

Summary

Following its introductory credits, which are displayed to the Army Air Force Orchestra's cover version of "March of the Volunte ...

, Tibet is incorrectly called a province of China. (The official name is Tibet Area, and it's not a province.) In 1944, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, two Austrian mountaineers, Heinrich Harrer and Peter Aufschnaiter

Peter Aufschnaiter (2 November 1899 – 12 October 1973) was an Austrian mountaineer, agricultural scientist, geographer and cartographer. His experiences with fellow climber Heinrich Harrer during World War II were depicted in the 1997 film ' ...

, came to Lhasa, where Harrer became a tutor and friend to the young Dalai Lama, giving him sound knowledge of Western culture and modern society, until Harrer chose to leave in 1949.

Tibet established a Foreign Office in 1942, and in 1946 it sent congratulatory missions to China and India (related to the end of World War II). The mission to China was given a letter addressed to Chinese President Chiang Kai-shek which states that, "We shall continue to maintain the independence of Tibet as a nation ruled by the successive Dalai Lamas through an authentic religious-political rule." The mission agreed to attend a Chinese constitutional assembly in Nanjing as observers.Smith, Daniel"Self-Determination in Tibet: The Politics of Remedies"

. Under orders from the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

government of Chiang Kai-shek, Ma Bufang repaired the Yushu airport in 1942 to deter Tibetan independence. Chiang also ordered Ma Bufang to put his Muslim soldiers on alert for an invasion of Tibet in 1942.Ma Bufang complied, and moved several thousand troops to the border with Tibet. Chiang also threatened the Tibetans with bombing if they did not comply.

In 1947, Tibet sent a delegation to the

In 1947, Tibet sent a delegation to the Asian Relations Conference

The Asian Relations Conference was an international conference that took place in New Delhi from 23 March to 2 April, 1947. Organized by the Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA), the Conference was hosted by Jawaharlal Nehru, then the Vice-P ...

in New Delhi, India, where it represented itself as an independent nation, and India recognised it as an independent nation from 1947 to 1954. This may have been the first appearance of the Tibetan national flag at a public gathering.

André Migot

André Migot (1892–1967) was a French doctor, traveler and writer.

He served as an army medical officer in World War I, winning the Croix de Guerre. After the war he engaged in research in marine biology, and then practised as a doctor in F ...

, a French doctor who travelled for many months in Tibet in 1947, described the complex border arrangements between Tibet and China, and how they had developed:

In 1947–49, Lhasa sent a trade mission led by Finance Minister

In 1947–49, Lhasa sent a trade mission led by Finance Minister Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa

Tsepon Wangchuk Deden Shakabpa (, January 11, 1907 – February 23, 1989) was a Tibetan nobleman, scholar, statesman and former Finance Minister of the government of Tibet.

Biography

Tsepon Shakabpa was born in Lhasa Tibet. His father, Laja Tas ...

to India, China, Hong Kong, the US, and the UK. The visited countries were careful not to express support for the claim that Tibet was independent of China and did not discuss political questions with the mission. These Trade Mission officials entered China via Hong Kong with their newly issued Tibetan passports that they applied at the Chinese Consulate in India and stayed in China for three months. Other countries did, however, allow the mission to travel using passports issued by the Tibetan government. The U.S. unofficially received the Trade Mission. The mission met with British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

in London in 1948.

Annexation by the People's Republic of China

In 1949, seeing that the Communists were gaining control of China, the Kashag government expelled all Chinese officials from Tibet despite protests from both the Kuomintang and the Communists. On 1 October 1949, the10th Panchen Lama

Lobsang Trinley Lhündrub Chökyi Gyaltsen (born Gönbo Cêdän; 19 February 1938 – 28 January 1989) was the tenth Panchen Lama, officially the 10th Panchen Erdeni (), of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. According to Tibetan Buddhis ...

wrote a telegraph to Beijing, expressing his congratulations for the liberation of northwest China and the establishment of People's Republic of China, and his excitement to see the inevitable liberation of Tibet. The Chinese Communist

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victorious in the Chinese Ci ...

government led by Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

which came to power in October lost little time in asserting a new Chinese presence in Tibet. In June 1950 the British government stated in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

that His Majesty's Government "have always been prepared to recognise Chinese suzerainty over Tibet, but only on the understanding that Tibet is regarded as autonomous". In October 1950, the People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the China, People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five Military branch, service branches: the People's ...

entered the Tibetan area of Chamdo

Chamdo, officially Qamdo () and also known in Chinese as Changdu, is a prefecture-level city in the eastern part of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China. Its seat is the town of Chengguan in Karuo District. Chamdo is Tibet's third largest city ...

, defeating sporadic resistance from the Tibetan Army

The Tibetan Army () was the military force of Tibet after its ''de facto'' independence in 1912 until the 1950s. As a ground army modernised with the assistance of British training and equipment, it served as the ''de facto'' armed forces of th ...

. In 1951, representatives of the Tibetan authorities, headed by Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, with the Dalai Lama's authorization, participated in negotiations in Beijing with the Chinese government. It resulted in the Seventeen Point Agreement which affirmed China's sovereignty over Tibet. The agreement was ratified in Lhasa a few months later. China described the entire process as the "peaceful liberation of Tibet".

Politics

Government

Military

After the 13th Dalai Lama had assumed full control over Tibet in the 1910s, he began to build up the

After the 13th Dalai Lama had assumed full control over Tibet in the 1910s, he began to build up the Tibetan Army

The Tibetan Army () was the military force of Tibet after its ''de facto'' independence in 1912 until the 1950s. As a ground army modernised with the assistance of British training and equipment, it served as the ''de facto'' armed forces of th ...

with support from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, which provided advisors and weapons. This army was supposed to be large and modern enough to not just defend Tibet, but to also conquer surrounding regions like Kham

Kham (; )

is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being Amdo in the northeast, and Ü-Tsang in central Tibet. The original residents of Kham are called Khampas (), and were governed locally by chieftains and monasteries. Kham ...

which were inhabited by Tibetan peoples. The Tibetan Army was constantly expanded during the 13th Dalai Lama's reign, and had about 10,000 soldiers by 1936. These were adequately armed and trained infantrymen for the time, though the army almost completely lacked machine guns, artillery, planes and tanks. In addition to the regular army, Tibet also made use of great numbers of poorly armed village militias. Considering that it was usually outgunned by their opponents, the Tibetan Army performed relatively well against various Chinese warlords in the 1920s and 1930s. Overall, the Tibetan soldiers proved to be "fearless and tough fighters" during the Warlord Era.

Despite this, the Tibetan Army was wholly inadequate to resist the People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the China, People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five Military branch, service branches: the People's ...

(PLA) during the Chinese invasion of 1950. It consequently disintegrated and surrendered without much resistance.

Postal service

Foreign relations

The division of China into military cliques kept China divided, and the 13th Dalai Lama ruled but his reign was marked with border conflicts with Han Chinese and Muslim warlords, which the Tibetans lost most of the time. At that time, the government of Tibet controlled all of

The division of China into military cliques kept China divided, and the 13th Dalai Lama ruled but his reign was marked with border conflicts with Han Chinese and Muslim warlords, which the Tibetans lost most of the time. At that time, the government of Tibet controlled all of Ü-Tsang

Ü-Tsang is one of the three traditional provinces of Tibet, the others being Amdo in the north-east, and Kham in the east. Ngari (including former Guge kingdom) in the north-west was incorporated into Ü-Tsang. Geographically Ü-Tsang covered ...

(Dbus-gtsang) and western Kham

Kham (; )

is one of the three traditional Tibetan regions, the others being Amdo in the northeast, and Ü-Tsang in central Tibet. The original residents of Kham are called Khampas (), and were governed locally by chieftains and monasteries. Kham ...

(Khams), roughly coincident with the borders of the Tibet Autonomous Region

The Tibet Autonomous Region or Xizang Autonomous Region, often shortened to Tibet or Xizang, is a province-level autonomous region of the People's Republic of China in Southwest China. It was overlayed on the traditional Tibetan regions ...

today. Eastern Kham, separated by the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

, was under the control of Chinese warlord Liu Wenhui

Liu Wenhui (; 1895 – 24 June 1976) was a Chinese general and warlord of Sichuan province (Sichuan clique). At the beginning of his career, he was aligned with the Kuomintang (KMT), commanding the Sichuan-Xikang Defence Force from 1927 to 1929. ...

. The situation in Amdo (Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

) was more complicated, with the Xining

Xining (; ), alternatively known as Sining, is the capital of Qinghai province in western China and the largest city on the Tibetan Plateau.

The city was a commercial hub along the Northern Silk Road's Hexi Corridor for over 2000 years, and w ...

area controlled after 1928 by the Hui warlord Ma Bufang

Ma Bufang (1903 – 31 July 1975) (, Xiao'erjing: ) was a prominent Muslim Ma clique warlord in China during the Republic of China era, ruling the province of Qinghai. His rank was Lieutenant-general.

General Ma started an industrialization pro ...

of the family of Muslim warlords known as the Ma clique

The Ma clique or Ma family warlords is a collective name for a group of Hui (Muslim Chinese) warlords in Northwestern China who ruled the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Ningxia for 10 years from 1919 until 1928. Following the collapse ...

, who constantly strove to exert control over the rest of Amdo (Qinghai). Southern Kham along with other parts of Yunnan belonged to the Yunnan clique

The Yunnan clique () was one of several mutually hostile cliques or factions that split from the Beiyang Government in the Republic of China's warlord era. It was named for Yunnan Province.

History

Kunming Uprising

When the 1911 Revolutio ...

from 1915 till 1927, then to Governor and warlord Long (Lung) Yun until near the end of the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

, when Du Yuming

Du Yuming (; 28 November 1904 – 7 May 1981), was a Kuomintang field commander. He was a graduate of the first class of Whampoa Academy, took part in Chiang's Northern Expedition, and was active in southern China and in the Burma theatre of th ...

removed him under the order of Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

. Within territory under Chinese control, war was being waged against Tibetan rebels in Qinghai during the Kuomintang Pacification of Qinghai

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

.

In 1918, Lhasa

Lhasa (; Lhasa dialect: ; bo, text=ལྷ་ས, translation=Place of Gods) is the urban center of the prefecture-level Lhasa City and the administrative capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in Southwest China. The inner urban area of Lhasa ...

regained control of Chamdo

Chamdo, officially Qamdo () and also known in Chinese as Changdu, is a prefecture-level city in the eastern part of the Tibet Autonomous Region, China. Its seat is the town of Chengguan in Karuo District. Chamdo is Tibet's third largest city ...

and western Kham. A truce set the border at the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

. At this time, the government of Tibet controlled all of Ü-Tsang and Kham west of the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

, roughly the same borders as the Tibet Autonomous Region

The Tibet Autonomous Region or Xizang Autonomous Region, often shortened to Tibet or Xizang, is a province-level autonomous region of the People's Republic of China in Southwest China. It was overlayed on the traditional Tibetan regions ...

has today. Eastern Kham was governed by local Tibetan princes of varying allegiances. Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

was controlled by ethnic Hui and pro-Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

warlord Ma Bufang

Ma Bufang (1903 – 31 July 1975) (, Xiao'erjing: ) was a prominent Muslim Ma clique warlord in China during the Republic of China era, ruling the province of Qinghai. His rank was Lieutenant-general.

General Ma started an industrialization pro ...

. In 1932 Tibet invaded Qinghai, attempting to capture southern parts of Qinghai province, following contention in Yushu, Qinghai over a monastery in 1932. Ma Bufang's Qinghai army defeated the Tibetan armies.

During the 1920s and 1930s, China was divided by civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

and occupied with the anti-Japanese war

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese ...

, but never renounced its claim to sovereignty over Tibet, and made occasional attempts to assert it.

In 1932, the Muslim Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

and Han-Chinese Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

armies of the National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

led by Ma Bufang and Liu Wenhui defeated the Tibetan Army

The Tibetan Army () was the military force of Tibet after its ''de facto'' independence in 1912 until the 1950s. As a ground army modernised with the assistance of British training and equipment, it served as the ''de facto'' armed forces of th ...

in the Sino-Tibetan War

The Sino-Tibetan War (, lit. Kham–Tibet dispute) was a war that began in 1930 when the Tibetan Army under the 13th Dalai Lama responded to the attempted seizure of a monastery. Chinese-administered eastern Kham region (later called Xikang), ...

when the 13th Dalai Lama tried to seize territory in Qinghai and Xikang. They warned the Tibetans not to dare cross the Jinsha river again. A truce was signed, ending the fighting. The Dalai Lama had cabled the British in India for help when his armies were defeated, and started demoting his Generals who had surrendered.

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai

Sheng Shicai (; 3 December 189513 July 1970) was a Chinese warlord who ruled Xinjiang from 1933 to 1944. Sheng's rise to power started with a coup d'état in 1933 when he was appointed the ''duban'' or Military Governor of Xinjiang. His rule o ...

expelled 30,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, Hui led by General Ma Bufang

Ma Bufang (1903 – 31 July 1975) (, Xiao'erjing: ) was a prominent Muslim Ma clique warlord in China during the Republic of China era, ruling the province of Qinghai. His rank was Lieutenant-general.

General Ma started an industrialization pro ...

massacred their fellow Muslim Kazakhs, until there were 135 of them left.

From Northern Xinjiang over 7,000 Kazakhs fled to the Tibetan-Qinghai plateau region via Gansu and were wreaking massive havoc so Ma Bufang solved the problem by relegating the Kazakhs into designated pastureland in Qinghai, but Hui, Tibetans, and Kazakhs in the region continued to clash against each other.

Tibetans attacked and fought against the Kazakhs as they entered Tibet via Gansu and Qinghai.

In northern Tibet Kazakhs clashed with Tibetan soldiers and then the Kazakhs were sent to Ladakh.

Tibetan troops robbed and killed Kazakhs 400 miles east of Lhasa at Chamdo when the Kazakhs were entering Tibet.

In 1934, 1935, 1936–1938 from Qumil Eliqsan led the Kerey Kazakhs to migrate to Gansu and the amount was estimated at 18,000, and they entered Gansu and Qinghai.

In 1951, the Uyghur Yulbars Khan was attacked by Tibetan troops as he fled Xinjiang to reach Calcutta.

The anti-communist American CIA agent Douglas Mackiernan was killed by Tibetan troops on 29 April 1950.

Economy

Currency

The Tibetan government issued banknotes and coins.

The Tibetan government issued banknotes and coins.

Society and culture

Traditional Tibetan society consisted of a feudalclass structure

A social class is a grouping of people into a set of hierarchical social categories, the most common being the upper, middle and lower classes. Membership in a social class can for example be dependent on education, wealth, occupation, inco ...

, which was one of the reasons the Chinese Communist Party claims that it had to liberate Tibet and reform its government.

Professor of Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

and Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

an studies Donald S. Lopez stated that at the time:

These institutional groups retained great power until 1959.

The 13th Dalai Lama had reformed the pre-existing serf system in the first decade of the 20th century, and by 1950, slavery itself had probably ceased to exist in central Tibet, though perhaps persisting in certain border areas. Slavery did exist, for example, in places like the Chumbi Valley

The Chumbi Valley, called Dromo or Tromo in Tibetan,

is a valley in the Himalayas that projects southwards from the Tibetan plateau, intervening between Sikkim and Bhutan. It is coextensive with the administrative unit Yadong County in the T ...

, though British observers like Charles Bell

Sir Charles Bell (12 November 177428 April 1842) was a Scottish surgeon, anatomist, physiologist, neurologist, artist, and philosophical theologian. He is noted for discovering the difference between sensory nerves and motor nerves in the spin ...

called it 'mild', and beggars (''ragyabas'') were endemic. The pre-Chinese social system however was rather complex.

Estates (''shiga''), roughly similar to the English manorial system

Manorialism, also known as the manor system or manorial system, was the method of land ownership (or "tenure") in parts of Europe, notably France and later England, during the Middle Ages. Its defining features included a large, sometimes forti ...

, were granted by the state and were hereditary, though revocable. As agricultural properties they consisted of two kinds: land held by the nobility or monastic institutions (demesne land), and village land (tenement or villein land) held by the central government, though governed by district administrators. Demesne land consisted on average of one-half to three-quarters of an estate. Villein land belonged to the estates, but tenants normally exercised hereditary usufruct rights in exchange for fulfilling their corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

obligations. Tibetans outside the nobility and the monastic system were classified as serfs, but two types existed and functionally were comparable to tenant farmers

A tenant farmer is a person ( farmer or farmworker) who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management ...

. Agricultural serfs, or "small smoke" (''düchung''), were bound to work on estates as a corvée obligation (''ula'') but they had title to their own plots, owned private goods, were free to move about outside the periods required for their tribute labor, and were free of tax obligations. They could accrue wealth and on occasion became lenders to the estates themselves, and could sue the estate owners: village serfs (''tralpa'') were bound to their villages but only for tax and corvée purposes, such as road transport duties (''ula''), and were only obliged to pay taxes. Half of the village serfs were man-lease serfs (''mi-bog''), meaning that they had purchased their freedom. Estate owners exercised broad rights over attached serfs, and flight or a monastic life was the only venue of relief. Yet no mechanism existed to restore escaped serfs to their estates, and no means to enforce bondage existed, though the estate lord held the right to pursue and forcibly return them to the land.

Any serf who had absented himself from his estate for three years was automatically granted either commoner (''chi mi'') status or reclassified as a serf of the central government. Estate lords could transfer their subjects to other lords or rich peasants for labor, though this practice was uncommon in Tibet. Though rigid structurally, the system exhibited considerable flexibility at ground level, with peasants free of constraints from the lord of the manor once they had fulfilled their corvée obligations. Historically, discontent or abuse of the system, according to Warren W. Smith, appears to have been rare. Tibet was far from a meritocracy, but the Dalai Lamas were recruited from the sons of peasant families, and the sons of nomads could rise to master the monastic system and become scholars and abbots.Donald S Lopez Jr., ''Prisoners of Shangri-La,'' p. 9.

See also

*Arunachal Pradesh

Arunachal Pradesh (, ) is a state in Northeastern India. It was formed from the erstwhile North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) region, and became a state on 20 February 1987. It borders the states of Assam and Nagaland to the south. It shares ...

* South Tibet

South Tibet is a claimed area by China with the literal translation of the Chinese term '' (), which may refer to different geographic areas:

* The southern part of Tibet, covering the middle reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River Valley between ...

* Captive Nations

"Captive Nations" is a term that arose in the United States to describe nations under undemocratic regimes. During the Cold War, when the phrase appeared, it referred to nations under Communist administration, primarily Soviet rule.

As a part o ...

* Flag of Tibet

Tibet is a region in East Asia covering much of the Tibetan Plateau that is currently administered by People's Republic of China as the Tibet Autonomous Region and claimed by the Republic of China as the Tibet Area and the Central Tibetan Adm ...

* Four Rugby Boys

The 1910s saw an attempt to turn four young Tibetans – the Four Rugby Boys – into the vanguard of "modernisers" through the medium of an English public school education.British Intelligence on China in Tibet, 1903–1950'', Formerly classifi ...

* Ganden Phodrang

The Ganden Phodrang or Ganden Podrang (; ) was the Tibetan system of government established by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1642; it operated in Tibet until the 1950s. Lhasa became the capital of Tibet again early in this period, after the Oirat lo ...

* Historical money of Tibet

The use of historical money in Tibet started in ancient times, when Tibet had no coined currency of its own. Bartering was common, gold was a medium of exchange, and shell money and stone beads were used for very small purchases. A few coins fr ...

* History of Tibet (1950–present)

The history of Tibet from 1950 to the present includes the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950, and the Battle of Chamdo. Before then, Tibet had been a ''de facto'' independent nation. In 1951, Tibetan representatives in Beijing signed the Seven ...

* Kashag

The Kashag (; ), was the governing council of Tibet during the rule of the Qing dynasty and post-Qing period until the 1950s. It was created in 1721, and set by Qianlong Emperor in 1751 for the Ganden Phodrang in the 13-Article Ordinance for ...

* Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission

The Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission (MTAC) was a ministry-level commission of the Executive Yuan in the Republic of China. It was disbanded on 15 September 2017.

History

The first model was created during the Qing dynasty in 1636 ...

* Tibet Area (administrative division)

The Tibet Area was a province-level administrative division of the Republic of China which consisted of Ü-Tsang (central Tibet) and Ngari (western Tibet) areas, but excluding the Amdo and Kham areas. However, the Republic of China never exerc ...

* Tibet under Qing rule

Tibet under Qing rule refers to the Qing dynasty's relationship with Tibet from 1720 to 1912. The political status of Tibet during this period has been the subject of political debate. The Qing called Tibet a ''fanbang'' or ''fanshu'', which has ...

Notes

References

Citations

Sources

* * * * Berkin, Martyn. ''The Great Tibetan Stonewall of China'' (1924) Barry Rose Law Publishes Ltd. . * Chapman, F. Spencer. ''Lhasa the Holy City'' (1977) Books for Libraries. ; first published 1940 by Readers Union Ltd., London. * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * ** * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Tibet (1912-51) History of Tibet Former countries in Asia Former theocracies .1912 . . . .1950 Disputed territories in Asia Former countries in Chinese history Former unrecognized countries Former monarchies Former monarchies of Asia Neutral states in World War II 1912 establishments in Tibet 1912 establishments in Asia 1951 disestablishments in Asia 1951 disestablishments in China 20th century in Tibet