Tibesti on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Tibesti Mountains are a

The mountains lie on the border between Chad and

The mountains lie on the border between Chad and

mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

in the central Sahara, primarily located in the extreme north of Chad, with a small portion located in southern Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

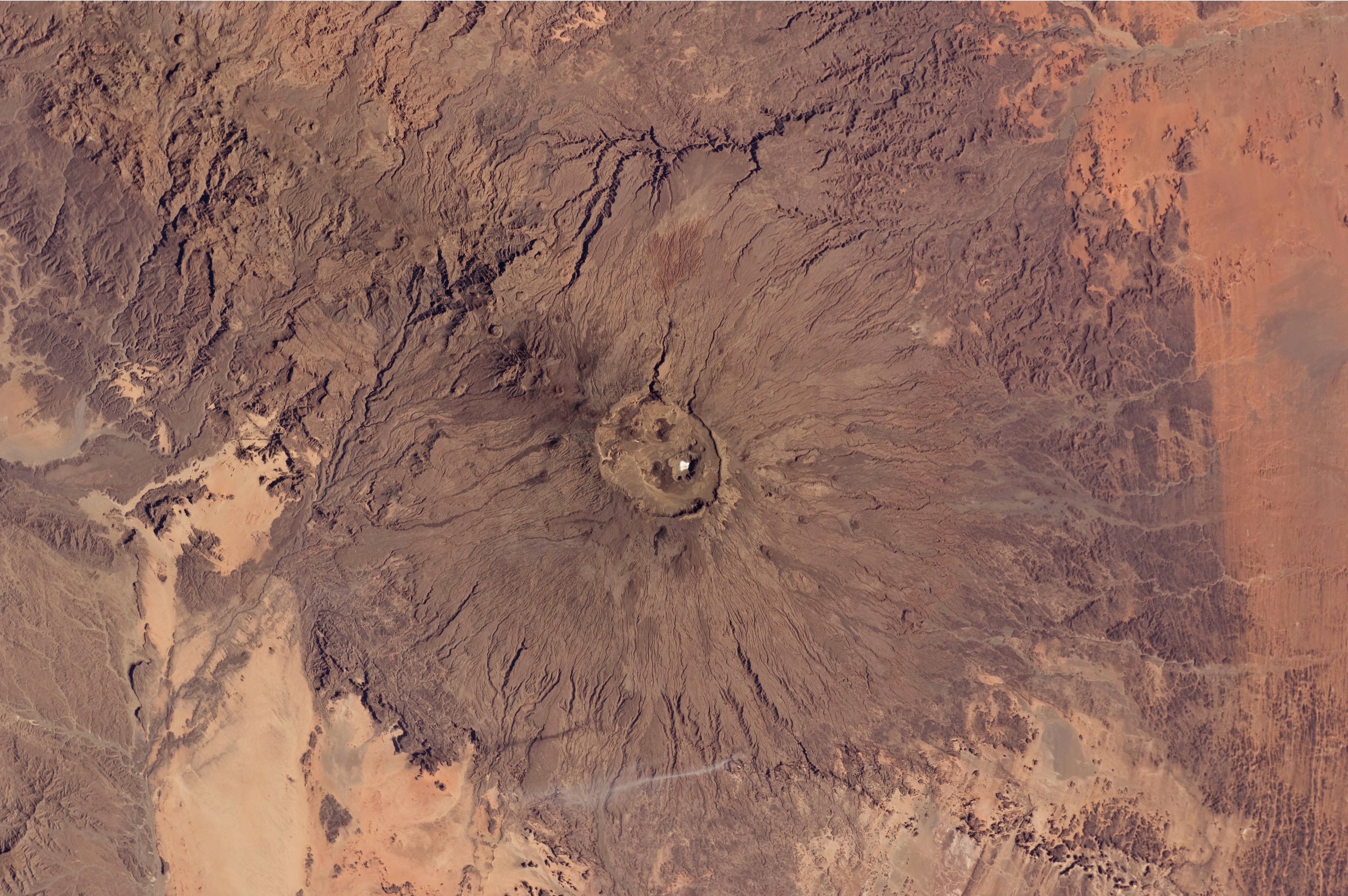

. The highest peak in the range, Emi Koussi

Emi Koussi (also known as Emi Koussou) is a high pyroclastic shield volcano that lies at the southeast end of the Tibesti Mountains in the central Sahara, in the northern Borkou Region of northern Chad. The highest mountain of the Sahara, the vo ...

, lies to the south at a height of and is the highest point in both Chad and the Sahara. Bikku Bitti, the highest peak in Libya, is located in the north of the range. The central third of the Tibesti is of volcanic origin and consists of five volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the Crust (geology), crust of a Planet#Planetary-mass objects, planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and volcanic gas, gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Ear ...

es topped by large depressions: Emi Koussi, Tarso Toon

Tarso Toon (sometimes also known as Tarso Toh; "Tarso" means "high plateau".) is a volcano in the central Tibesti mountains.

The volcano reaches a maximum height of and a width of , covering a surface of . It also features a caldera wide, with a ...

, Tarso Voon, Tarso Yega and Toussidé. Major lava flows have formed vast plateaus that overlie Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

sandstone. The volcanic activity was the result of a continental hotspot that arose during the Oligocene and continued in some places until the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

, creating fumaroles, hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by c ...

s, mud pool

A mudpot, or mud pool, is a sort of acidic hot spring, or fumarole, with limited water. It usually takes the form of a pool of bubbling mud. The acid and microorganisms decompose surrounding rock into clay and mud.

Description

The mud of a mud ...

s and deposits of natron

Natron is a naturally occurring mixture of sodium carbonate decahydrate ( Na2CO3·10H2O, a kind of soda ash) and around 17% sodium bicarbonate (also called baking soda, NaHCO3) along with small quantities of sodium chloride and sodium sulfate. ...

and sulfur. Erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is dis ...

has shaped volcanic spires and carved an extensive network of canyons through which run rivers subject to highly irregular flows that are rapidly lost to the desert sands.

Tibesti, which means "place where the mountain people live", is the domain of the Toubou people. The Toubou live mainly along the wadi

Wadi ( ar, وَادِي, wādī), alternatively ''wād'' ( ar, وَاد), North African Arabic Oued, is the Arabic term traditionally referring to a valley. In some instances, it may refer to a wet (ephemeral) riverbed that contains water ...

s, on rare oases where palm tree

The Arecaceae is a family of perennial flowering plants in the monocot order Arecales. Their growth form can be climbers, shrubs, tree-like and stemless plants, all commonly known as palms. Those having a tree-like form are called palm ...

s and limited grains grow. They harness the water that collects in gueltas, the supply of which is highly variable from year-to-year and decade-to-decade. The plateaus are used to graze livestock in the winter and harvest grain in the summer. Temperatures are high, although the altitude ensures that the range is cooler than the surrounding desert. The Toubou, who were settled in the range by the 5th century BC, adapted to these conditions and turned the range into a large natural fortress. They arrived in several waves, taking refuge in times of conflict and dispersing in times of prosperity, although not without intense internal hostility at times.

The Toubou came into contact with the Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

, Berbers, Tuaregs

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym: ''Imuhaɣ/Imušaɣ/Imašeɣăn/Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group that principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern ...

, Ottomans and the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, as well as the French colonists who first entered the range in 1914 and took control of the area in 1929. The independent spirit of the Toubou and the geopolitics of the region has complicated the exploration of the range as well as the ascent of its peaks. Tensions continued after Chad and Libya gained independence in the mid-20th century, with hostage-taking and armed struggles occurring amid disputes over the allocation of natural resources. The geopolitical situation and the lack of infrastructure has hampered the development of tourism.

The Saharomontane flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' ...

and fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is ''funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as ''Biota (ecology ...

, which include the rhim gazelle

The rhim gazelle or rhim (''Gazella leptoceros''), also known as the slender-horned gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder's gazelle, is a pale-coated gazelle with long slender horns and well adapted to desert life. It is considered an endangered ...

and Barbary sheep

The Barbary sheep (''Ammotragus lervia''), also known as aoudad (pronounced �ɑʊdæd is a species of caprine native to rocky mountains in North Africa. While this is the only species in genus ''Ammotragus'', six subspecies have been descri ...

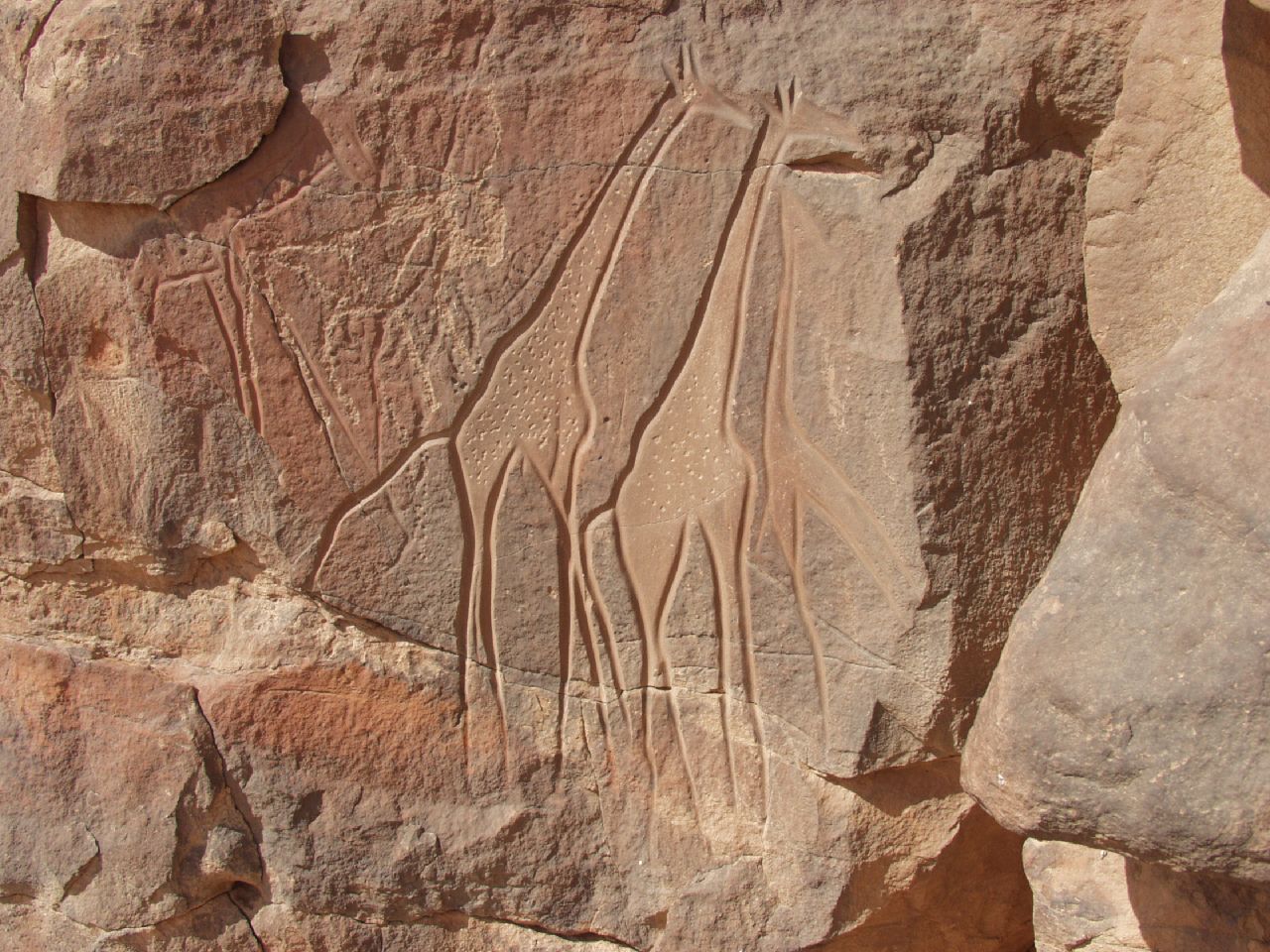

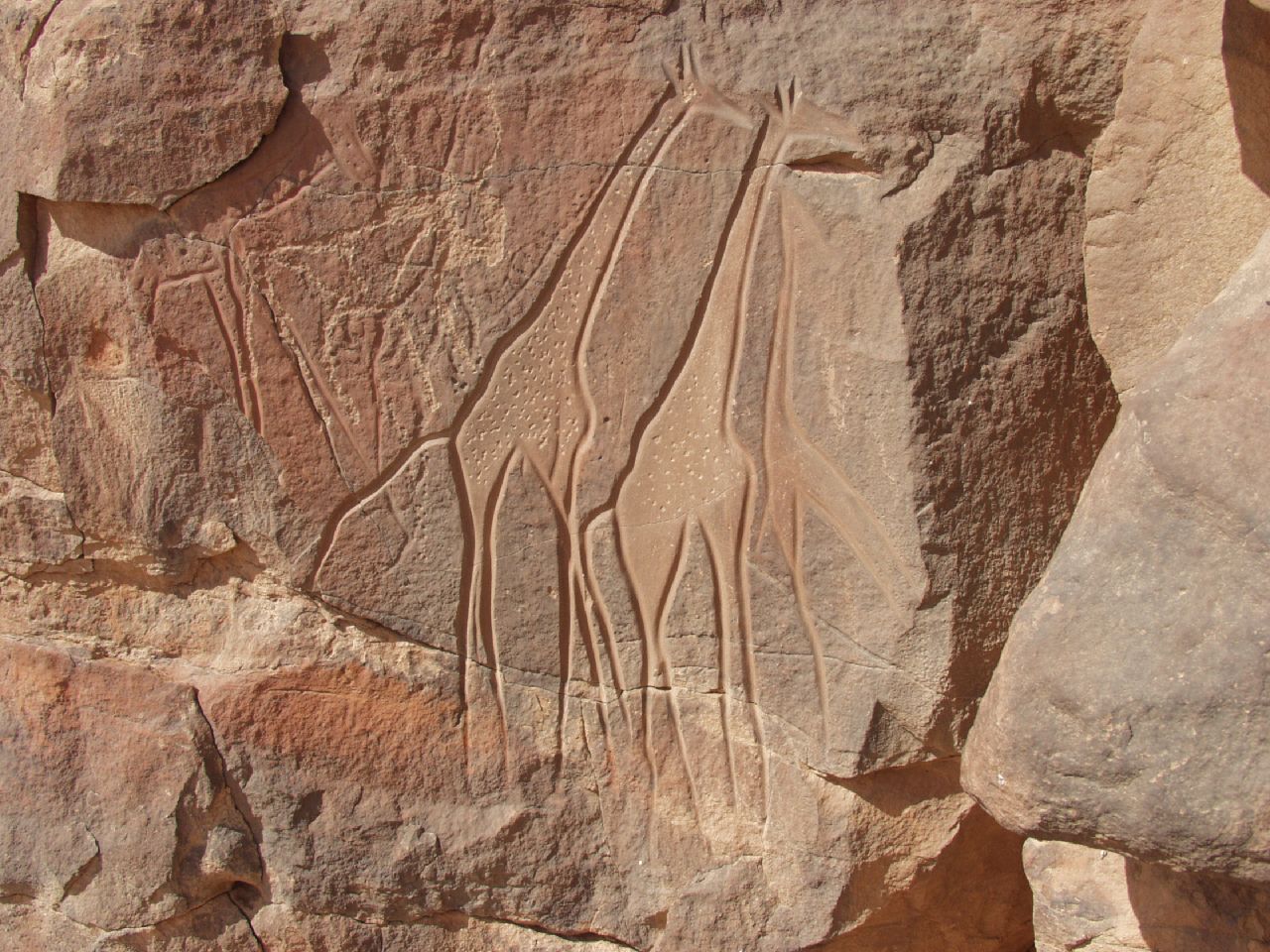

, have adapted to the mountains, yet the climate has not always been as harsh. Greater biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (''genetic variability''), species (''species diversity''), and ecosystem (''ecosystem diversity'') l ...

existed in the past, as evidenced by scenes portrayed in rock and parietal art found throughout the range, which date back several millennia, even before the arrival of the Toubou. The isolation of the Tibesti has sparked the cultural imagination in both art and literature.

Toponymy

The Tibesti Mountains are named for the Toubou people, also written ''Tibu'' or ''Tubu'', that inhabit the area. In theKanuri language

Kanuri () is a dialect continuum spoken in Nigeria, Niger, Chad and Cameroon, as well as in small minorities in southern Libya and by a diaspora in Sudan.

Background

At the turn of the 21st century, its two main dialects, Manga Kanuri and Yerwa ...

, ''tu'' means "rocks" or "mountain" and ''bu'' means "a person" or "dweller," and thus ''Toubou'' roughly translates to "people of the mountains" and ''Tibesti'' to the "place where the mountain people live".

Most of the mountain names are derived from Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

as well as the Tedaga and Dazaga languages. The term ''ehi'' precedes the names of peaks and rocky hills, ''emi'' precedes those of larger mountains, and ''tarso'' precedes high plateaus and gently-sloping mountainsides. For example, the Ehi Mousgou is a stratovolcano near Tarso Voon. The name Toussidé means "that which killed the Tou," as in the Toubou, reflecting the danger of the still active volcano. The name of Bardaï, the principal town in the range, means "cold" in Chadian Arabic

Chadian Arabic ( ar, لهجة تشادية), also known as Shuwa Arabic, Baggara Arabic, Western Sudanic Arabic, or West Sudanic Arabic (WSA), is a variety of Arabic and the first language of 1.6 million people, both town dwellers and nomadic c ...

. In the Tedaga language, the town is known as ''Goumodi'', which means "red pass," signifying the color of the mountains at dusk.

Geography

Location

The mountains lie on the border between Chad and

The mountains lie on the border between Chad and Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

, straddling the Chadian region of Tibesti and the Libyan districts of Murzuq and Kufra

Kufra () is a basinBertarelli (1929), p. 514. and oasis group in the Kufra District of southeastern Cyrenaica in Libya. At the end of nineteenth century Kufra became the centre and holy place of the Senussi order. It also played a minor role in ...

, around north of N'djamena

N'Djamena ( ) is the capital and largest city of Chad. It is also a special statute region, divided into 10 districts or ''arrondissements''.

The city serves as the centre of economic activity in Chad. Meat, fish and cotton processing are the c ...

and south-southeast of Tripoli. The range is adjacent to Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesGulf of Sidra and Lake Chad, just south of the

The range includes five shield volcanoes with broad bases whose diameter can reach : Emi Koussi; Tarso Toon, which rises above sea level; Tarso Voon; Tarso Yega; and Tarso Toussidé, which culminates in the peak of the same name. Several of these peaks are topped with large calderas. Tarso Yega has the largest caldera, with a diameter of and a depth of approximately , while Tarso Voon has the deepest caldera, with a depth of approximately and a diameter of . They are complemented by four large lava dome complexes, high and several km wide, all located in the central part of the mountain range: Tarso Tieroko; Ehi Yéy; Ehi Mousgou; and Tarso Abeki, which rises to above sea level. These volcanic complexes are now considered inactive, but according to the

The range includes five shield volcanoes with broad bases whose diameter can reach : Emi Koussi; Tarso Toon, which rises above sea level; Tarso Voon; Tarso Yega; and Tarso Toussidé, which culminates in the peak of the same name. Several of these peaks are topped with large calderas. Tarso Yega has the largest caldera, with a diameter of and a depth of approximately , while Tarso Voon has the deepest caldera, with a depth of approximately and a diameter of . They are complemented by four large lava dome complexes, high and several km wide, all located in the central part of the mountain range: Tarso Tieroko; Ehi Yéy; Ehi Mousgou; and Tarso Abeki, which rises to above sea level. These volcanic complexes are now considered inactive, but according to the

Five rivers in the northern half of the Tibesti Mountains flow to Libya, while the southern half belongs to the

Five rivers in the northern half of the Tibesti Mountains flow to Libya, while the southern half belongs to the  Two other major rivers cut into the mountains: the Enneri Yebige flows northward until its riverbed disappears on the ''Serir Tibesti'', while Enneri Touaoul joins the south-flowing Enneri Ke to form Enneri Miski, which then disappears in the plains of Borkou. Their basins are separated by an high watershed that runs from Tarso Tieroko in the west to Tarso Mohi in the east. The Enneri Tijitinga is the longest wadi in the range, flowing some southward. It forms in the west of the range and peters out in the

Two other major rivers cut into the mountains: the Enneri Yebige flows northward until its riverbed disappears on the ''Serir Tibesti'', while Enneri Touaoul joins the south-flowing Enneri Ke to form Enneri Miski, which then disappears in the plains of Borkou. Their basins are separated by an high watershed that runs from Tarso Tieroko in the west to Tarso Mohi in the east. The Enneri Tijitinga is the longest wadi in the range, flowing some southward. It forms in the west of the range and peters out in the

The Tibesti Mountains are a large area of

The Tibesti Mountains are a large area of

Volcanic activity in the Tibesti took place in several phases. In the first phase, uplift and extension of the Precambrian basement occurred in the central area. The first structure to be formed was probably Tarso Abeki, followed by Tarso Tamertiou, Tarso Tieroko, Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon and Ehi Yéy. The product of this early volcanic activity has been completely obscured by later eruptions. In the second phase, the volcanic activity moved north and east, forming Tarso Ourari and the ignimbrite bases of the vast ''tarsos'', as well as Emi Koussi to the southeast. Thereafter, during the third phase, the outpouring of lava and ejecta deposits increased from Tarso Yega,

Volcanic activity in the Tibesti took place in several phases. In the first phase, uplift and extension of the Precambrian basement occurred in the central area. The first structure to be formed was probably Tarso Abeki, followed by Tarso Tamertiou, Tarso Tieroko, Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon and Ehi Yéy. The product of this early volcanic activity has been completely obscured by later eruptions. In the second phase, the volcanic activity moved north and east, forming Tarso Ourari and the ignimbrite bases of the vast ''tarsos'', as well as Emi Koussi to the southeast. Thereafter, during the third phase, the outpouring of lava and ejecta deposits increased from Tarso Yega,  The Trou au Natron and Doon Kidimi craters have formed even more recently, with the former dissecting the earlier Toussidé calderas. Lava flows, minor pyroclastic deposits, and the appearance of small cinder cones, and the formation of the Era Kohor crater are the most recent volcanic activities on Emi Koussi. there are reports of volcanic activity in various parts of the massif, including hot springs at the Soborom geothermal field and fumaroles on Tarso Voon, Yi Yerra near Emi Koussi and Pic Toussidé.

The Trou au Natron and Doon Kidimi craters have formed even more recently, with the former dissecting the earlier Toussidé calderas. Lava flows, minor pyroclastic deposits, and the appearance of small cinder cones, and the formation of the Era Kohor crater are the most recent volcanic activities on Emi Koussi. there are reports of volcanic activity in various parts of the massif, including hot springs at the Soborom geothermal field and fumaroles on Tarso Voon, Yi Yerra near Emi Koussi and Pic Toussidé.

The flora in the Tibesti is Saharomontane, mixing

The flora in the Tibesti is Saharomontane, mixing  Saharomontane

Saharomontane

The town of Bardaï, located on the northern flank of the mountains at an elevation of , is the capital of the Tibesti region. It is connected to the town of Zouar, to the southwest, by a track that crosses Tarso Toussidé. The village of Omchi is accessible from Bardaï via Aderké, or from the town of Aouzou via Irbi. These rough tracks extend southward towards Yebbi Souma and Yebbi Bou, and then follow the course of Enneri Misky. The eastern half of the Tibesti is cut off from the western half, and the eastern village of Aozi is accessible from Libya via Ouri. Zouar has an

The town of Bardaï, located on the northern flank of the mountains at an elevation of , is the capital of the Tibesti region. It is connected to the town of Zouar, to the southwest, by a track that crosses Tarso Toussidé. The village of Omchi is accessible from Bardaï via Aderké, or from the town of Aouzou via Irbi. These rough tracks extend southward towards Yebbi Souma and Yebbi Bou, and then follow the course of Enneri Misky. The eastern half of the Tibesti is cut off from the western half, and the eastern village of Aozi is accessible from Libya via Ouri. Zouar has an  The vast majority of the population is Teda, one of the two ethnicities of the Toubou people. However, some clans are Daza, the other Toubou ethnicity, who left their traditional homes in the lowlands to the south and moved north to the Tibesti. The Toubou live primarily in northern Chad, but also in southern Libya and eastern Niger. The Toubou language has two main dialects, Tedaga, spoken by the Teda, and Dazaga, spoken by the Daza. Despite their differences, the two Toubou groups generally identify as a single ethnic group. The Toubou elect a chief, the '' Derdé'', from the Tomagra clan, although never from the same family consecutively. Historically, individual clans rarely had more than a thousand members and were quite dispersed throughout the Tibesti. the population of the Tibesti was officially estimated at 21,000 inhabitants. that number has risen to 54,000 inhabitants. Yet the Toubou, in general, are semi-nomadic, moving between the mountains and other regions, and thus the Tibesti may have no more than 10,000 to 15,000 permanent residents.

Traditional Toubou life is punctuated by the seasons, divided between animal husbandry and

The vast majority of the population is Teda, one of the two ethnicities of the Toubou people. However, some clans are Daza, the other Toubou ethnicity, who left their traditional homes in the lowlands to the south and moved north to the Tibesti. The Toubou live primarily in northern Chad, but also in southern Libya and eastern Niger. The Toubou language has two main dialects, Tedaga, spoken by the Teda, and Dazaga, spoken by the Daza. Despite their differences, the two Toubou groups generally identify as a single ethnic group. The Toubou elect a chief, the '' Derdé'', from the Tomagra clan, although never from the same family consecutively. Historically, individual clans rarely had more than a thousand members and were quite dispersed throughout the Tibesti. the population of the Tibesti was officially estimated at 21,000 inhabitants. that number has risen to 54,000 inhabitants. Yet the Toubou, in general, are semi-nomadic, moving between the mountains and other regions, and thus the Tibesti may have no more than 10,000 to 15,000 permanent residents.

Traditional Toubou life is punctuated by the seasons, divided between animal husbandry and

There is evidence of human occupation of the Tibesti dating back to the Stone Age, when denser paleovegetation facilitated human habitation. The Toubou were settled in the region by the 5th century BC and eventually established trade relations with the Carthaginian civilization. Around this time,

There is evidence of human occupation of the Tibesti dating back to the Stone Age, when denser paleovegetation facilitated human habitation. The Toubou were settled in the region by the 5th century BC and eventually established trade relations with the Carthaginian civilization. Around this time,  The Toubou settled in the Tibesti in several waves. Generally, newcomers either killed or absorbed the previous clans after battles that were often both long-lasting and bloody. The Teda clans, considered indigenous to the area, were first established around Enneri Bardagué. Namely, these clans were the Cerdegua, Zouia, Kossseda (nicknamed ''yobat'' or "hunters of well water"), and possibly the Ederguia, although the Ederguia's origin may be Zaghawa and only go back to the 17th century. These clans controlled the palm groves, and made a peace pact with the Tomagra, a nearby clan of camel herders who practiced ''

The Toubou settled in the Tibesti in several waves. Generally, newcomers either killed or absorbed the previous clans after battles that were often both long-lasting and bloody. The Teda clans, considered indigenous to the area, were first established around Enneri Bardagué. Namely, these clans were the Cerdegua, Zouia, Kossseda (nicknamed ''yobat'' or "hunters of well water"), and possibly the Ederguia, although the Ederguia's origin may be Zaghawa and only go back to the 17th century. These clans controlled the palm groves, and made a peace pact with the Tomagra, a nearby clan of camel herders who practiced ''

In 1978, war broke out between Chad and Libya ostensibly over the Aouzou Strip, a borderland between Chad and Libya that extends into the Tibesti Mountains and is rumored to contain

In 1978, war broke out between Chad and Libya ostensibly over the Aouzou Strip, a borderland between Chad and Libya that extends into the Tibesti Mountains and is rumored to contain

Due to its isolation and geopolitical situation, the Tibesti Mountains were long unexplored by scientists. The German

Due to its isolation and geopolitical situation, the Tibesti Mountains were long unexplored by scientists. The German

Although

Although

As the Sahara's highest mountain range, with geothermal features, a distinctive culture, and numerous rock and parietal artworks, the Tibesti has tourism potential. However, tourist accommodations are limited at best. In the early 2010s, the French adventure travel company Point-Afrique financed the repair of the

As the Sahara's highest mountain range, with geothermal features, a distinctive culture, and numerous rock and parietal artworks, the Tibesti has tourism potential. However, tourist accommodations are limited at best. In the early 2010s, the French adventure travel company Point-Afrique financed the repair of the

The Tibesti Mountains are renowned for their rock and parietal art. Around 200 engraving sites and 100 painting sites have been identified. Many date as early as the 6th millennium BC, long before the arrival of the Toubou. The art has suffered the effects of time, including weathering from sand blown by the wind. The earliest works often portray animals that have since died out in the region due to

The Tibesti Mountains are renowned for their rock and parietal art. Around 200 engraving sites and 100 painting sites have been identified. Many date as early as the 6th millennium BC, long before the arrival of the Toubou. The art has suffered the effects of time, including weathering from sand blown by the wind. The earliest works often portray animals that have since died out in the region due to

The Tibesti Mountains

University of Applied Sciences Burgenland

Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands

World Wildlife Fund {{Authority control Stratovolcanoes Hotspot volcanoes Mountain ranges of Libya Mountain ranges of Chad Volcanoes of Chad Saharan rock art Potentially active volcanoes Inactive volcanoes Volcanic groups Sahara

Tropic of Cancer

The Tropic of Cancer, which is also referred to as the Northern Tropic, is the most northerly circle of latitude on Earth at which the Sun can be directly overhead. This occurs on the June solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted tow ...

. The East African Rift is to the east and the Cameroon line lies to the southwest.

The range is in length, in width, and spans . It draws a large triangle with sides of and vertices facing south, northwest and northeast in the heart of the Sahara, making it the largest mountain range of the desert.

Topography

The highest peak in the Tibesti Mountains, as well as the highest point in Chad and the Sahara Desert, is the Emi Koussi, located at the southern end of the range. Other prominent peaks include Pic Toussidé at and the Timi on its western side, the Tarso Yega, the Tarso Tieroko, the Ehi Mousgou, the Tarso Voon, the Ehi Sunni, and the Ehi Yéy near the center of the range. The Mouskorbé is a peak notable for its height in the northeastern part of the mountain range. The Bikku Bitti, the highest point in Libya, is nearby, on the other side of the border. The average elevation of the Tibesti Mountains is about ; sixty percent of its area exceeds in elevation.Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

were active during the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

. Tarso Toussidé is an active volcano that has spewed lava over the past two millennia. Gases escaping from fumarole

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or other rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volcani ...

s on Toussidé are visible when evaporation is low. The volcano's crater, Trou au Natron, is in diameter and deep. On the northwest side of Tarso Voon is the Soborom geothermal field, which contains mud pools and fumaroles that vent sulfuric acid. The sulfur has stained the surrounding soil bright colors. Fumaroles are also present at the Yi Yerra hot springs on Emi Koussi. Tarso Tôh was an active volcano in the early Holocene. The volcanic area of the Tibesti Mountains is located entirely in Chad; it covers about a third of the total area of the Tibesti Mountains and is responsible for between of rock.

The rest of the Tibesti Mountains consists of volcanic plateau

A volcanic plateau is a plateau produced by volcanic activity. There are two main types: lava plateaus and pyroclastic plateaus.

Lava plateau

Lava plateaus are formed by highly fluid basaltic lava during numerous successive eruptions throu ...

s (''tarsos''), located between elevation, as well as lava fields and ejecta deposits. The plateaus are larger and more numerous in the east: the Tarso Emi Chi, the Tarso Aozi, the Tarso Ahon to the north of Emi Koussi, and the Tarso Mohi. In the center is Tarso Ourari at about . To the west, in the vicinity of Tarso Toussidé, is the aforementioned Tarso Tôh, a small plateau at just , and the even smaller Tarso Tamertiou at . The plateaus are strewn with volcanic spires and are separated by canyons that have been formed by the irregular flow of wadi

Wadi ( ar, وَادِي, wādī), alternatively ''wād'' ( ar, وَاد), North African Arabic Oued, is the Arabic term traditionally referring to a valley. In some instances, it may refer to a wet (ephemeral) riverbed that contains water ...

s. After often-violent rains, they see the formation of ephemeral streams and flora. The southern, southwestern and eastern slopes of the mountain range have a gentle rise, while the northern slope of the range is a cliff overlooking the vast Libyan desert pavement

A desert pavement, also called reg (in the western Sahara), serir (eastern Sahara), gibber (in Australia), or saï (central Asia) is a desert surface covered with closely packed, interlocking angular or rounded rock fragments of pebble and cob ...

known as the ''Serir Tibesti''.

Hydrology

Five rivers in the northern half of the Tibesti Mountains flow to Libya, while the southern half belongs to the

Five rivers in the northern half of the Tibesti Mountains flow to Libya, while the southern half belongs to the endorheic basin

An endorheic basin (; also spelled endoreic basin or endorreic basin) is a drainage basin that normally retains water and allows no outflow to other external bodies of water, such as rivers or oceans, but drainage converges instead into lakes ...

of Lake Chad. However, none of the rivers travel long distances, as the water evaporates in the desert heat or seeps into the ground, although the latter may flow great distances through subterranean aquifer

An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing, permeable rock, rock fractures, or unconsolidated materials ( gravel, sand, or silt). Groundwater from aquifers can be extracted using a water well. Aquifers vary greatly in their characteris ...

s.

The wadis in the Tibesti are called ''enneris''. The water mainly originates from the storms that periodically rage over the mountains. Their flow is highly variable. For example, the largest wadi, named Bardagué (or Enneri Zoumeri on its upstream portion) and located in the northern part of the range, recorded a flow of in 1954, yet over the next nine years it experienced four years of total drought, four years of flow less than and one year where three different flow rates were measured: .

Two other major rivers cut into the mountains: the Enneri Yebige flows northward until its riverbed disappears on the ''Serir Tibesti'', while Enneri Touaoul joins the south-flowing Enneri Ke to form Enneri Miski, which then disappears in the plains of Borkou. Their basins are separated by an high watershed that runs from Tarso Tieroko in the west to Tarso Mohi in the east. The Enneri Tijitinga is the longest wadi in the range, flowing some southward. It forms in the west of the range and peters out in the

Two other major rivers cut into the mountains: the Enneri Yebige flows northward until its riverbed disappears on the ''Serir Tibesti'', while Enneri Touaoul joins the south-flowing Enneri Ke to form Enneri Miski, which then disappears in the plains of Borkou. Their basins are separated by an high watershed that runs from Tarso Tieroko in the west to Tarso Mohi in the east. The Enneri Tijitinga is the longest wadi in the range, flowing some southward. It forms in the west of the range and peters out in the Bodélé Depression

The Bodélé Depression (), located at the southern edge of the Sahara Desert in north central Africa, is the lowest point in Chad. It is 500 km long, 150 km wide and around 160 m deep. Its bottom lies about 155 meters above sea leve ...

, as does Enneri Miski a little further to the east, along with other wadis such as the Enneri Korom and Enneri Aouei. Several rivers flow radially on the southern slopes of the Emi Koussi before seeping into the sands of Borkou and then reemerging at escarpment

An escarpment is a steep slope or long cliff that forms as a result of faulting or erosion and separates two relatively level areas having different elevations.

The terms ''scarp'' and ''scarp face'' are often used interchangeably with ''esca ...

s up to south of the summit, near the Ennedi Plateau

The Ennedi Plateau is located in the northeast of Chad, in the regions of Ennedi-Ouest and Ennedi-Est. It is considered a part of the group of mountains known as the Ennedi Massif found in Chad, which is one of the nine countries that make up ...

.

At the bottom of many canyons are gueltas, wetlands that accumulate water mainly during storms. Above , ''enneri'' beds sometimes contain sequential pools of water that . The water is replenished several times a year during flooding, and salinity levels are low. The Mare de Zoui is a small permanent body of water above sea level, located in the northern part of the mountains in the wadi of the Enneri Bardagué, east of Bardaï. Supplied by sources upstream of the wadi, in heavy rains it overflows and spills into small wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The p ...

s.

The Yi Yerra hot springs is located on the southern flank of Emi Koussi at about elevation. Water emerges from the springs at . A dozen hot springs are also located at the Soborom geothermal field on the northwest side of Tarso Voon, where water emerges at temperatures ranging between .

Geology

The Tibesti Mountains are a large area of

The Tibesti Mountains are a large area of tectonic uplift

Tectonic uplift is the geologic uplift of Earth's surface that is attributed to plate tectonics. While isostatic response is important, an increase in the mean elevation of a region can only occur in response to tectonic processes of crustal th ...

that, according to contemporary theory, resulted from a mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hot ...

in the craton

A craton (, , or ; from grc-gre, κράτος "strength") is an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere, which consists of Earth's two topmost layers, the crust and the uppermost mantle. Having often survived cycles of merging an ...

of the African lithosphere, which is about thick. This tectonic uplift may have been accompanied by the opening, and subsequent closure via subduction, of a rift zone

A rift zone is a feature of some volcanoes, especially shield volcanoes, in which a set of linear cracks (or rifts) develops in a volcanic edifice, typically forming into two or three well-defined regions along the flanks of the vent. Believed t ...

. A system of regional faults, although partially obscured by the volcanic product, has two distinct orientations: a NNE-SSW alignment that could be an extension of Cameroon line, and a NW-SE alignment that could extend to the Great Rift Valley

The Great Rift Valley is a series of contiguous geographic trenches, approximately in total length, that runs from Lebanon in Asia to Mozambique in Southeast Africa. While the name continues in some usages, it is rarely used in geology as it ...

; however, the relationship between these fault systems has not been conclusively demonstrated.

The basement of the Tibesti is composed of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies under ...

, diorite

Diorite ( ) is an intrusive igneous rock formed by the slow cooling underground of magma (molten rock) that has a moderate content of silica and a relatively low content of alkali metals. It is intermediate in composition between low-sili ...

and schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

, one of six exposures of Precambrian crystalline rock in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

. These are overlaid by sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

of the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

era, while the peaks consist of volcanic rock

Volcanic rock (often shortened to volcanics in scientific contexts) is a rock formed from lava erupted from a volcano. In other words, it differs from other igneous rock by being of volcanic origin. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic ...

. The continental hotspot activity began as early as the Oligocene, although most of the volcanic rock dates from the Lower Miocene

The Early Miocene (also known as Lower Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene Epoch made up of two stages: the Aquitanian and Burdigalian stages.

The sub-epoch lasted from 23.03 ± 0.05 Ma to 15.97 ± 0.05 Ma (million years ago). It was prec ...

to the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

and, in places, to the Holocene. Due to the comparatively slow movement of the African plate—roughly between per year since the Lower Miocene—there is no relationship between the age of the volcanoes and their dimensions, geographic distribution or alignment, in contrast to hotspots such as the Hawaiian–Emperor and Cook- Austral seamount chains. This phenomenon is also seen in Martian volcanoes, particularly Elysium Mons

Elysium Mons is a volcano on Mars located in the volcanic province Elysium, at , in the Martian eastern hemisphere. It stands about above its base, and about above the Martian ''datum'', making it the third tallest Martian mountain in terms o ...

. Early volcanic activity created trap basalt

A flood basalt (or plateau basalt) is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that covers large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava. Many flood basalts have been attributed to the onset of a hotspot reach ...

formations that extend tens of kilometers and stack up to thick. Basanite and andesite

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predo ...

are also found in the volcanic layer. More recently in geologic time, volcanic activity has deposited dacite

Dacite () is a volcanic rock formed by rapid solidification of lava that is high in silica and low in alkali metal oxides. It has a fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic texture and is intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite ...

, rhyolite and ignimbrite

Ignimbrite is a type of volcanic rock, consisting of hardened tuff. Ignimbrites form from the deposits of pyroclastic flows, which are a hot suspension of particles and gases flowing rapidly from a volcano, driven by being denser than the surro ...

, as well as trachyte

Trachyte () is an extrusive igneous rock composed mostly of alkali feldspar. It is usually light-colored and aphanitic (fine-grained), with minor amounts of mafic minerals, and is formed by the rapid cooling of lava enriched with silica and al ...

and trachyandesite. This trend towards the production of more felsic, viscous lavas could be a sign of a waning mantle plume.

Geomorphology

Volcanic activity in the Tibesti took place in several phases. In the first phase, uplift and extension of the Precambrian basement occurred in the central area. The first structure to be formed was probably Tarso Abeki, followed by Tarso Tamertiou, Tarso Tieroko, Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon and Ehi Yéy. The product of this early volcanic activity has been completely obscured by later eruptions. In the second phase, the volcanic activity moved north and east, forming Tarso Ourari and the ignimbrite bases of the vast ''tarsos'', as well as Emi Koussi to the southeast. Thereafter, during the third phase, the outpouring of lava and ejecta deposits increased from Tarso Yega,

Volcanic activity in the Tibesti took place in several phases. In the first phase, uplift and extension of the Precambrian basement occurred in the central area. The first structure to be formed was probably Tarso Abeki, followed by Tarso Tamertiou, Tarso Tieroko, Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon and Ehi Yéy. The product of this early volcanic activity has been completely obscured by later eruptions. In the second phase, the volcanic activity moved north and east, forming Tarso Ourari and the ignimbrite bases of the vast ''tarsos'', as well as Emi Koussi to the southeast. Thereafter, during the third phase, the outpouring of lava and ejecta deposits increased from Tarso Yega, Tarso Toon

Tarso Toon (sometimes also known as Tarso Toh; "Tarso" means "high plateau".) is a volcano in the central Tibesti mountains.

The volcano reaches a maximum height of and a width of , covering a surface of . It also features a caldera wide, with a ...

, Tarso Tieroko and Ehi Yéy; the collapse of these structures formed the first calderas. This phase also saw the formation of the Bounaï lava dome and Tarso Voon. To the east, the lava flows formed the large plateaus of Tarso Emi Chi, Tarso Ahon and Tarso Mohi. Emi Koussi increased in height. The fourth phase saw the formation of Tarso Toussidé and the lava flows of Tarso Tôh in the west, the collapse of the caldera on the summit of Tarso Voon and associated ejecta deposits in the center, and the decline in lava production in the east, with the exception of Emi Koussi, which continued to rise. In the fifth phase, volcanic activity became much more localized and lava production continued to wane. Calderas formed on top of Tarso Toussidé and Emi Koussi, and the lava domes Ehi Sosso and Ehi Mousgou appeared. Finally, in the sixth phase, Pic Toussidé formed on the western rim of several pre-Trou au Natron calderas, along with new lava flows, including Timi on the northern slope of Tarso Toussidé. With scarce time for erosion, these lava flows have a dark, youthful appearance.

The Trou au Natron and Doon Kidimi craters have formed even more recently, with the former dissecting the earlier Toussidé calderas. Lava flows, minor pyroclastic deposits, and the appearance of small cinder cones, and the formation of the Era Kohor crater are the most recent volcanic activities on Emi Koussi. there are reports of volcanic activity in various parts of the massif, including hot springs at the Soborom geothermal field and fumaroles on Tarso Voon, Yi Yerra near Emi Koussi and Pic Toussidé.

The Trou au Natron and Doon Kidimi craters have formed even more recently, with the former dissecting the earlier Toussidé calderas. Lava flows, minor pyroclastic deposits, and the appearance of small cinder cones, and the formation of the Era Kohor crater are the most recent volcanic activities on Emi Koussi. there are reports of volcanic activity in various parts of the massif, including hot springs at the Soborom geothermal field and fumaroles on Tarso Voon, Yi Yerra near Emi Koussi and Pic Toussidé. Carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate ...

deposits in the Trou au Natron and Era Kohor craters are also representative of more recent volcanic activity.

The study of fluvial terrace

Fluvial terraces are elongated terraces that flank the sides of floodplains and fluvial valleys all over the world. They consist of a relatively level strip of land, called a "tread", separated from either an adjacent floodplain, other fluvial t ...

s has revealed coarse sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class o ...

and gravel alternating with terraces of silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

, clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

and fine sand. This alternation highlights repeated changes in the dominant fluvial or wind patterns in the valleys of Tibesti during the Quaternary Period

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million years ...

. The phases of erosion and sendimentation are indicative of the climate alternating between dry and wet conditions, the latter of which fostered vegetation in the Tibesti that was likely significantly denser than that which exists today. Furthermore, the discovery of calcified charophyta

Charophyta () is a group of freshwater green algae, called charophytes (), sometimes treated as a division, yet also as a superdivision or an unranked clade. The terrestrial plants, the Embryophyta emerged within Charophyta, possibly from terre ...

(particularly of the family Characeae) and gastropod fossils in Trou au Natron indicates the presence of a lake at least deep during the Late Pleistocene. These phenomena are associated with various changes in climate, most notably during the last glacial maximum

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

, which increased precipitation and reduced evaporation due to lower temperatures. In fact, the Tibesti supplied a considerable amount of water to the Paleolake Chad until the 5th millennium BC

The 5th millennium BC spanned the years 5000 BC to 4001 BC (c. 7 ka to c. 6 ka). It is impossible to precisely date events that happened around the time of this millennium and all dates mentioned here are estimates mostly based on geological an ...

.

Climate

The Tibesti climate is substantially less dry than that of the surroundingSahara Desert

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, but rainfall events are highly variable from year to year. In the south of the range, this variation is largely due to oscillations of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which steadily moves northward toward northern Chad from November until August, accompanied by humid monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal osci ...

al air. Normally, the ITCZ repels the Harmattan, a dry trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisph ...

that blows west or southwest from the Sahara Desert, and brings rainfall to southern Tibesti. However, sometimes the front retires early, before reaching the Tibesti, leaving its southern portion dry. In the arid northern Tibesti, where the monsoon has little influence, storms are caused by episodic Sahara-Sudanese weather systems. For example, between 1957 and 1968, Bardaï, on the northern flank of the range, saw an average of of precipitation annually, yet some years were completely dry while others saw of rainfall. In general, the range receives less than of rainfall per year. However, precipitation increases with altitude; for example Trou au Natron receives annually. When the rainfall coincides with low temperatures, it can fall as snow. This occurs, on average, once every seven years.

The average monthly maximum temperature is in the central Tibesti Mountains, while the average monthly minimum is . Lows of are not uncommon. Bardaï, located above sea level, experiences average temperatures ranging between in January, between in April, and between in August. The combination of high temperatures and low humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation, dew, or fog to be present.

Humidity dep ...

results in potentially high evaporation rates, ranging from in January to in May, parching many ''enneris'' before they can exit the mountain range.

Flora and fauna

Like an island surrounded by ocean, theecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

of the Tibesti Mountains is distinguishable from that of the surrounding desert. As such, the mountains lie within their own biome

A biome () is a biogeographical unit consisting of a biological community that has formed in response to the physical environment in which they are found and a shared regional climate. Biomes may span more than one continent. Biome is a broader ...

, the Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands ecoregion, along with the Jebel Uweinat, a disjunct mountain range that also rises from the Sahara to the east. Much of the ecoregion remains unexplored due to its remoteness and persistent political instability, yet it is known to contain a number of endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

and endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and in ...

species. Indeed, the isolation of the region is a benefit to its flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' ...

and fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is ''funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as ''Biota (ecology ...

, serving as a sort of refuge, allowing plants to grow untrammeled and animals to roam unmolested. Nevertheless, hunting is unregulated in the region, and vegetation has suffered from overgrazing in the past.

Flora

The flora in the Tibesti is Saharomontane, mixing

The flora in the Tibesti is Saharomontane, mixing Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

, Sahara, Sahel and Afromontane vegetation. Biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (''genetic variability''), species (''species diversity''), and ecosystem (''ecosystem diversity'') l ...

and endemism levels are higher in the Tibesti than in the Aïr Mountains

The Aïr Mountains or Aïr Massif ( tmh, Ayăr; Hausa: Eastern ''Azbin'', Western ''Abzin'') is a triangular massif, located in northern Niger, within the Sahara. Part of the West Saharan montane xeric woodlands ecoregion, the ...

or the Ennedi Plateau, although the vegetation's coverage is highly dependent on rainfall. Oases lie along the courses of the ''enneris'', such as Enneri Yebige. These oases, which are more numerous to the north and west of the range, are scattered with acacia, figs

The fig is the edible fruit of ''Ficus carica'', a species of small tree in the flowering plant family Moraceae. Native to the Mediterranean and western Asia, it has been cultivated since ancient times and is now widely grown throughout the world ...

, palms and tamarisk

The genus ''Tamarix'' (tamarisk, salt cedar, taray) is composed of about 50–60 species of flowering plants in the family Tamaricaceae, native to drier areas of Eurasia and Africa. The generic name originated in Latin and may refer to the Ta ...

s. Most gueltas are lined with macrophytes—including smooth flatsedge (''Cyperus laevigatus'') and branched horsetail (''Equisetum ramosissimum'')—and bryophyte

The Bryophyta s.l. are a proposed taxonomic division containing three groups of non-vascular land plants (embryophytes): the liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Bryophyta s.s. consists of the mosses only. They are characteristically limited in s ...

s—including '' Oxyrrhynchium speciosum'' and species of ''Bryum

''Bryum'' is a genus of mosses in the family Bryaceae. It was considered the largest genus of mosses, in terms of the number of species (over 1000), until it was split into three separate genera in a 2005 publication. As of 2013, the classificat ...

''. Egyptian acacia (''Vachellia nilotica'' syn. ''Acacia nilotica'') grows near these water basins. Saharan myrtle (''Myrtus nivellei'') and oleander (''Nerium oleander'') grow between elevations of in the western part of the range, while Nile tamarisk (''Tamarix nilotica'') grows at similar elevations in its northern part. Downstream, where the current of the ''enneris'' is slower and the riverbed is deeper, there are dense thickets of Athel tamarisk (''Tamarix aphylla'' syn. ''Tamarix articulata'') and arak (''Salvadora persica'').

Around the edge of the Tibesti, where the canyons exit the range, are doum palms (''Hyphaene thebaica''). The banks of Mare de Zoui are home to dense stands of reeds (''Phragmites australis

''Phragmites australis'', known as the common reed, is a species of plant. It is a broadly distributed wetland grass that can grow up to tall.

Description

''Phragmites australis'' commonly forms extensive stands (known as reed beds), which may ...

'' and '' Typha capensis''), along with sedges

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus ''Carex'' wit ...

(''Scirpoides holoschoenus''), sea rush Sea rush is a common name for several rushes in the genus ''Juncus'' and may refer to:

*''Juncus kraussii'', native to the Southern hemisphere

*''Juncus maritimus

''Juncus maritimus'', known as the sea rush, is a species of rush that grows on c ...

(''Juncus maritimus''), toad rush (''Juncus bufonius'') and branched horsetail (''E. ramosissimum''), while pondweed

Pondweed refers to many species and genera of aquatic plants and green algae:

*''Potamogeton'', a diverse and worldwide genus

*''Elodea'', found in North America

*''Aponogeton'', in Africa, Asia and Australasia

*''Groenlandia

''Groenlandia'' is ...

(''Potamogeton'' spp.) grows in the open water. Although the lake appears rich in phytoplankton, it has not been thoroughly studied. To the south and southwest of the range, between elevation, the wadis support woody species characteristic of the Sahel, such as Egyptian balsam (''Balanites aegyptiaca''), grey-leaved cordia (''Cordia sinensis''), red-leaved fig (''Ficus ingens''), sycamore fig

''Ficus sycomorus'', called the sycamore fig or the fig-mulberry (because the leaves resemble those of the mulberry), sycamore, or sycomore, is a fig species that has been cultivated since ancient times.

The term '' sycamore'' spelled with an A ...

(''F. sycomorus''), wonderboom (''F. salicifolia'') and gay acacia (''Senegalia laeta'' syn. ''Acacia laeta''). '' Chrysopogon plumulosus'' is the most common grass

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns a ...

in the area. Other plants have more Mediterranean characteristics, such as globularia (''Globularia alypum'') and lavender

''Lavandula'' (common name lavender) is a genus of 47 known species of flowering plants in the mint family, Lamiaceae. It is native to the Old World and is found in Cape Verde and the Canary Islands, and from Europe across to northern and easte ...

(''Lavandula pubescens'') or the more tropical sweet Indian mallow (''Abutilon fruticosum'') and least snout-bean (''Rhynchosia minima'' syn. ''Rhynchosia memnonia''). The liverwort '' Plagiochasma rupestre'' is found around the wadis at these elevations, as are mosses of the genera '' Fissidens'', '' Gymnostomum'' and '' Timmiella''.

grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses ( Poaceae). However, sedge ( Cyperaceae) and rush ( Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur na ...

s are found on the slopes, plateaus and the upper portions of the wadis at elevations between . They are dominated by '' Stipagrostis obtusa'' and '' Aristida caerulescens'', as well some '' Eragrostis papposa'' locally. In addition, shrubs represented by jointed anabis (''Anabasis articulata''), '' Fagonia flamandii'' and '' Zilla spinosa'' dot this environment. On the sheltered upper slopes of Emi Koussi is the endemic grass '' Eragrostis kohorica'', named after the volcano's crater.

The vegetation above consists of dwarf shrubs, which are generally limited to in height and do not exceed . The shrubbery consists of the species '' Pentzia monodiana'', '' Artemisia tilhoana'' and ''Ephedra tilhoana Ephedra may refer to:

* Ephedra (medicine), a medicinal preparation from the plant ''Ephedra sinica''

* ''Ephedra'' (plant), genus of gymnosperm shrubs

See also

* Ephedrine

Ephedrine is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is oft ...

''. At the highest elevations of the Tibesti, tree heath

''Erica arborea'', the tree heath or tree heather, is a species of flowering plant (angiosperms) in the heather family Ericaceae, native to the Mediterranean Basin and Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania in East Africa. It is also cultivated as an or ...

(''Erica arborea'') grows from moist crevices formed by early lava flows, while 24 different species of moss provide substrate for the tree heath. Various genera of mosses also grow around fumaroles, including ''Fissidens'', '' Campylopus'', ''Gymnostomum'' and '' Trichostomum''. Lichens, though rare in the dry climate of the Tibesti, also grow at these elevations, with green rock shield (''Xanthoparmelia conspersa''), scrambled-egg lichen (''Fulgensia fulgens''), sunken disk lichen (''Aspicilia'' spp.) and '' Squamarina crassa'' found on the highest peaks.

Fauna

Mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur o ...

abound in the Tibesti. Bovid

The Bovidae comprise the biological family of cloven-hoofed, ruminant mammals that includes cattle, bison, buffalo, antelopes, and caprines. A member of this family is called a bovid. With 143 extant species and 300 known extinct species, ...

s include the endangered addax (''Addax nasomaculatus'') along with the dorcas gazelle

The dorcas gazelle (''Gazella dorcas''), also known as the ariel gazelle, is a small and common gazelle. The dorcas gazelle stands about at the shoulder, with a head and body length of and a weight of . The numerous subspecies survive on vegeta ...

(''Gazella dorcas''), rhim gazelle

The rhim gazelle or rhim (''Gazella leptoceros''), also known as the slender-horned gazelle, African sand gazelle or Loder's gazelle, is a pale-coated gazelle with long slender horns and well adapted to desert life. It is considered an endangered ...

(''Gazella leptoceros'') and a significant population of Barbary sheep

The Barbary sheep (''Ammotragus lervia''), also known as aoudad (pronounced �ɑʊdæd is a species of caprine native to rocky mountains in North Africa. While this is the only species in genus ''Ammotragus'', six subspecies have been descri ...

(''Ammotragus lervia''). Rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are n ...

s are the most represented order of mammals, and include the spiny mouse (''Acomys'' spp.), bushy-tailed jird

The bushy-tailed jird or bushy-tailed dipodil (''Sekeetamys calurus'') is a species of rodent in the family Muridae. It is the only species in the genus ''Sekeetamys''. It is found in Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan. Its natural ha ...

(''Sekeetamys calurus'') and the North African gerbil (''Dipodillus campestris'' syn. ''Gerbillus campestris''). Also present are cat

The cat (''Felis catus'') is a domestic species of small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and is commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from the wild members of ...

s such as the African wildcat

The African wildcat (''Felis lybica'') is a small wildcat species native to Africa, West and Central Asia up to Rajasthan in India and Xinjiang in China. It has been listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List in 2022.

In Cyprus, an African wil ...

(''Felis lybica'') and, more rarely, the cheetah

The cheetah (''Acinonyx jubatus'') is a large cat native to Africa and central Iran. It is the fastest land animal, estimated to be capable of running at with the fastest reliably recorded speeds being , and as such has evolved specialized ...

(''Acinonyx jubatus''), as well as several canine species, including the golden jackal

The golden jackal (''Canis aureus''), also called common jackal, is a wolf-like canid that is native to Southeast Europe, Southwest Asia, South Asia, and regions of Southeast Asia. The golden jackal's coat varies in color from a pale creamy ...

(''Canis aureus''), fennec fox

The fennec fox (''Vulpes zerda'') is a small crepuscular fox native to the deserts of North Africa, ranging from Western Sahara to the Sinai Peninsula. Its most distinctive feature is its unusually large ears, which serve to dissipate heat and ...

(''Vulpes zerda'') and Rüppell's fox

Rüppell's fox (''Vulpes rueppellii''), also called Rüppell's sand fox, is a fox species living in desert and semi-desert regions of North Africa, the Middle East, and southwestern Asia. It has been listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List ...

(''Vulpes rueppellii''). The striped hyena (''Hyaena hyaena'') may also occupy the range. African wild dog

The African wild dog (''Lycaon pictus''), also called the painted dog or Cape hunting dog, is a wild canine which is a native species to sub-Saharan Africa. It is the largest wild canine in Africa, and the only extant member of the genus '' Lyca ...

s (''Lycaon pictus'') formerly roamed the range, although these populations are now extirpated

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

. Olive baboon

The olive baboon (''Papio anubis''), also called the Anubis baboon, is a member of the family Cercopithecidae Old World monkeys. The species is the most wide-ranging of all baboons, being native to 25 countries throughout Africa, extending fr ...

s (''Papio anubis''), found as recently as 1960, are now likely extirpated as well. Bat

Bats are mammals of the order Chiroptera.''cheir'', "hand" and πτερόν''pteron'', "wing". With their forelimbs adapted as wings, they are the only mammals capable of true and sustained flight. Bats are more agile in flight than most ...

s are heavily represented in the Tibesti, including the Egyptian mouse-tailed bat (''Rhinopoma cystops''), Egyptian slit-faced bat

The Egyptian slit-faced bat (''Nycteris thebaica'') is a species of slit-faced bat broadly distributed throughout Africa and the Middle East. It is a species of microbat in the family Nycteridae. Six subspecies are known.

Description

The Egypt ...

(''Nycteris thebaica'') and the trident bat

The trident bat or trident leaf-nosed bat (''Asellia tridens'') is a species of bat in the family Hipposideridae. It is widely distributed in the Middle East, South and Central Asia, and North, East, and Central Africa. Its natural habitats a ...

(''Asellia tridens''). The Cape hare

The Cape hare (''Lepus capensis''), also called the brown hare and the desert hare, is a hare native to Africa and Arabia extending into India.

Taxonomy

The Cape hare was one of the many mammal species originally described by Carl Linnaeus ...

(''Lepus capensis'') and the rock hyrax

The rock hyrax (; ''Procavia capensis''), also called dassie, Cape hyrax, rock rabbit, and (in the King James Bible) coney, is a medium-sized terrestrial mammal native to Africa and the Middle East. Commonly referred to in South Africa as the da ...

(''Procavia capensis'') also populate the area.

Reptiles and amphibians, on the other hand, are sparse. Snake

Snakes are elongated, limbless, carnivorous reptiles of the suborder Serpentes . Like all other squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales. Many species of snakes have skulls with several more j ...

species include the braid snake (''Platyceps rhodorachis'' syn. ''Coluber rhodorachis'') and the long-nosed worm snake (''Myriopholis macrorhyncha'' syn. ''Leptotyphlops macrorhynchus''). Among the lizards are Bibron's agama (''Agama impalearis''), the ringed wall gecko (''Tarentola annularis'') and the Sudan mastigure (''Uromastyx dispar''). Mid-20th-century herpetological studies noted the presence of brown frogs (''Rana'' sp.) and true toads (''Bufo'' sp.).

Many resident bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s can be found in the Tibesti. These include the crowned sandgrouse (''Pterocles coronatus''), bar-tailed lark

The bar-tailed lark or bar-tailed desert lark (''Ammomanes cinctura'') is a species of lark in the family Alaudidae. Two other species, the rufous-tailed lark and the Cape clapper lark are both also sometimes referred to using the name bar-ta ...

(''Ammomanes cincturus''), blackstart

__NOTOC__

The blackstart (''Oenanthe melanura'') is a chat found in desert regions in North Africa, the Middle East and the Arabian Peninsula. It is resident throughout its range.

The blackstart is 14 cm long and is named for its black ...

(''Oenanthe melanura'' syn. ''Cercomela melanura''), desert lark

The desert lark (''Ammomanes deserti'') breeds in deserts and semi-deserts from Morocco to western India. It has a very wide distribution and faces no obvious threats, and surveys have shown that it is slowly increasing in numbers as it expands ...

(''Ammomanes deserti''), desert sparrow (''Passer simplex''), fulvous babbler (''Argya fulva''), greater hoopoe-lark (''Alaemon alaudipes''), Lichtenstein's sandgrouse (''Pterocles lichtensteinii''), pale crag martin (''Ptyonoprogne obsoleta''), trumpeter finch

The trumpeter finch (''Bucanetes githagineus'') is a small passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. It is mainly a desert species which is found in North Africa and Spain through to southern Asia. It has occurred as a vagrant in are ...

(''Bucanetes githagineus'') and the white-crowned wheatear (''Oenanthe leucopyga'').

The gueltas are flushed periodically each year by stormwater, maintaining low salinity and supporting several species of freshwater fish. These include the African sharptooth catfish (''Clarias gariepinus''), East African red-finned barb (''Enteromius apleurogramma'' syn. ''Barbus apleurogramma''), Tibesti labeo

''Labeo'' is a genus of carps in the family Cyprinidae. They are found in freshwater habitats in the tropics and subtropics of Africa and Asia.

It contains the typical labeos in the subfamily Labeoninae, which may not be a valid group, however ...

(''Labeo tibestii'', an endemic species) and the redbelly tilapia

The redbelly tilapia (''Coptodon zillii'', syn. ''Tilapia zillii''), also known as the Zille's redbreast tilapia or St. Peter's fish (a name also used for other tilapia in Israel), is a species of fish in the cichlid family. This fish is found ...

(''Coptodon zillii'').

Population

airport

An airport is an aerodrome with extended facilities, mostly for commercial air transport. Airports usually consists of a landing area, which comprises an aerially accessible open space including at least one operationally active surfa ...

, as does Bardaï at Zougra. Bardaï also has a hospital, although the medical supply is very much dependent upon the prevailing political situation.

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people t ...

. Twentieth-century anthropological

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

studies show Toubou, particularly around palm groves, living in primitive round huts built with stone walls bound by mortar or clay, or built from clay or salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quant ...

blocks. In the highlands, the buildings were built of stone, forming circles in diameter and high, which served as shelters for goats, or as granaries, or as human shelters and defense structures. In other cases, the Toubou lived in tents that could be easily moved between the fields and the palm groves.

History

Human settlement

There is evidence of human occupation of the Tibesti dating back to the Stone Age, when denser paleovegetation facilitated human habitation. The Toubou were settled in the region by the 5th century BC and eventually established trade relations with the Carthaginian civilization. Around this time,

There is evidence of human occupation of the Tibesti dating back to the Stone Age, when denser paleovegetation facilitated human habitation. The Toubou were settled in the region by the 5th century BC and eventually established trade relations with the Carthaginian civilization. Around this time, Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

mentioned the Toubou, whom he labeled "Aethiopia

Ancient Aethiopia, ( gr, Αἰθιοπία, Aithiopía; also known as Ethiopia) first appears as a geographical term in classical documents in reference to the upper Nile region of Sudan, as well as certain areas south of the Sahara desert. Its ...

ns", and described them as having a language akin to the "cry of bats".

Herodotus further remarked on a conflict between the Toubou and the civilization of Garamantes

The Garamantes ( grc, Γαράμαντες, translit=Garámantes; la, Garamantes) were an ancient civilisation based primarily in present-day Libya. They most likely descended from Iron Age Berber tribes from the Sahara, although the earliest kn ...

based in present-day Libya. Between AD 83 and 92, a Roman traveler, likely a trader, named Julius Maternus

The gens Julia (''gēns Iūlia'', ) was one of the most prominent patrician families in ancient Rome. Members of the gens attained the highest dignities of the state in the earliest times of the Republic. The first of the family to obtain the ...

, explored the territory of the Tibesti Mountains with, or under the charge of, the king of Garamantes. The Tibesti are suspected by modern historians to have been part of an unidentified country named Agisymba, and Maternus's expedition may have been part of a broader military campaign by Garamantes against the populace of Agisymba.

In the 12th century, the geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, or simply al-Idrisi ( ar, أبو عبد الله محمد الإدريسي القرطبي الحسني السبتي; la, Dreses; 1100 – 1165), was a Muslim geographer, cartogra ...

spoke of a "country of Zaghawa negroes", or camel herders, that had converted to Islam. The historian Ibn Khaldun described the Toubou in the 14th century. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Al-Maqrizi and Leo Africanus

Joannes Leo Africanus (born al-Hasan Muhammad al-Wazzan, ar, الحسن محمد الوزان ; c. 1494 – c. 1554) was an Andalusian diplomat and author who is best known for his 1526 book '' Cosmographia et geographia de Affrica'', later ...

referred to the "country of the Berdoa", meaning Bardaï, the former associating the Toubou with the Berbers and the latter describing them as Numidian relatives of the Tuareg

The Tuareg people (; also spelled Twareg or Touareg; endonym: ''Imuhaɣ/Imušaɣ/Imašeɣăn/Imajeɣăn'') are a large Berber ethnic group that principally inhabit the Sahara in a vast area stretching from far southwestern Libya to southern Alg ...

.

Ghazw

A ''ghazi'' ( ar, غازي, , plural ''ġuzāt'') is an individual who participated in ''ghazw'' (, '' ''), meaning military expeditions or raiding. The latter term was applied in early Islamic literature to expeditions led by the Islamic prophe ...

''. It was upon the agreement to this pact at the end of the 16th century that power was consolidated under the Derdé, the principal regulator of the clans, whose appointment is always made from the Tomagra clan.

There is evidence of early Daza settlements in the Tibesti; however, these early clans—the Goga, Kida, Terbouna and Obokina—were assimilated into later Daza clans, who arrived in the Tibesti between the 15th and 18th centuries, possibly having fled the Kanem-Bornu Empire in the southwest. These later Daza arrivals include the Arna Souinga in the south, Gouboda in the center-west, Tchioda and Dirsina in the west, Torama in the northwest and center-east, and the Derdekichia (literally, "descendants of the chief," the products of a union between an Arna Souinga and an Emmeouia) in the north. The Tibesti then played the role of an impregnable mountain stronghold for the newcomers. Meanwhile, constant migration between the north and southwest of Chad, along with significant mixing of the populations, forged a significant degree of cohesion among the Toubou ethnicities. Periods of territorial expansion in the 10th and 13th centuries and periods of recession in the 15th and 16th centuries likely coincided with more or less pronounced wet and dry periods.

Several clans with traditions similar to those of the Donzas of the Borkou region, south of the Tibesti, settled in the range in the 16th and 17th centuries. These include the Keressa and Odobaya in the west, Foctoa in the northwest and northeast, and Emmeouia in the north. Several other clans—the Mogode in the west, Terintere in the north, Tozoba in the center, and Tegua and Mada in the south—are originally clans of the Bideyat people who immigrated from the Ennedi Plateau, southeast of Tibesti, around the same time. The Mada, however, have since largely emigrated to Borkou, Kaouar