Thomas Dixon Jr. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. (January 11, 1864 – April 3, 1946) was an American

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him relate to the working man's plight. Dixon grew up after the

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him relate to the working man's plight. Dixon grew up after the

/nowiki>clerical_robes.html" ;"title="clerical_robes.html" ;"title="/nowiki>clerical robes">/nowiki>clerical robes">clerical_robes.html" ;"title="/nowiki>clerical robes">/nowiki>clerical robes/nowiki> in the hope of adding to my dignity on Sunday by the judicious use of dry goods."

In 1896 Dixon's ''Failure of Protestantism in New York and its causes'' appeared.

"Dixon decided to move on and form a new church, the People's Church (sometimes described as the People's Temple), in the auditorium of the Academy of Music;" this was a

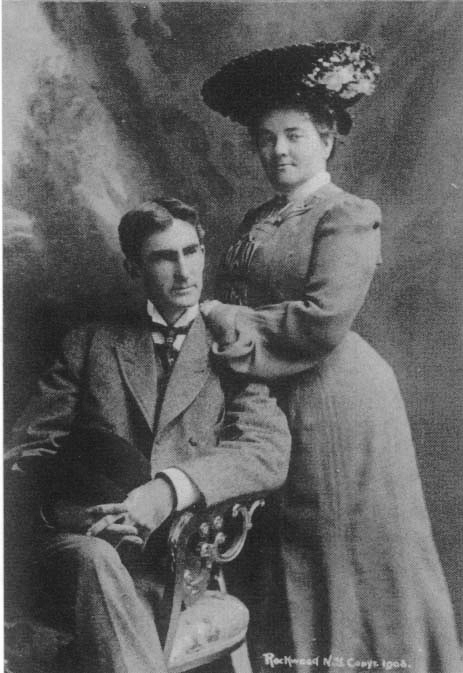

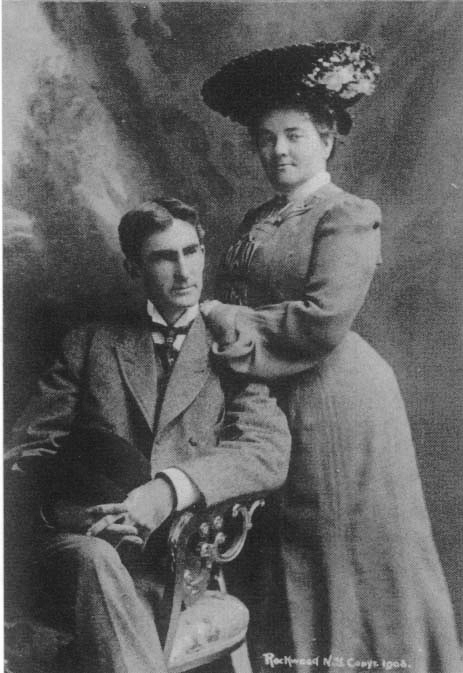

Dixon married Harriet Bussey on March 3, 1886. The couple eloped to

Dixon married Harriet Bussey on March 3, 1886. The couple eloped to

''The Southerner: A Romance of the Real Lincoln''

(1913) (First of three novels on Southern heroes) * ''The Victim: A Romance of the Real Jefferson Davis'' (1914) (Second of three novels on Southern heroes

Text from FadedPage.Text from Project Gutenberg.Original pages, from Kentucky Digital Library.

* '' The Foolish Virgin: A Romance of Today'' (1915) (opposes emancipation of women) * ''

''The Way of a Man. A Story of the New Woman''

(1918)

''The Man in Gray. A Romance of North and South''

(1921), on Robert E. Lee (Third of three novels on Southern heroes)

''The Black Hood''

(1924) (on the Ku Klux Klan) * ''The Love Complex'' (1925). Based on ''The Foolish Virgin''. * ''The Sun Virgin'' (1929) (On

''A Man of the People. A Drama of Abraham Lincoln''

(1920). "The three-act drama dealt with the Republican National Committee's request that Lincoln stand down as candidate for president at the end of his first term in office and Lincoln's conflict with

IMDb cast list

''Living problems in religion and social science'' (sermons)

(1889) * ''What is religion? : an outline of vital ritualism : four sermons preached in Association Hall, New York, December 1890'' (1891)

''Dixon on Ingersoll. Ten discourses, delivered in Association Hall, New York. With a Sketch of the Author by Nym Crinkle''

(1892)

''The failure of Protestantism in New York and its causes''

(1896) * ''An open letter from Rev. Thomas Dixon to J.C. Beam. Read it.'' (self-published pamphlet, 1896?) * ''Dixon's sermons. Vol. i, no. i-v. i, no. 4. : a monthly magazine'' (1898) (Pamphlets on the Spanish–American War.) * ''The Free lance. Vol. i, no. 5-v. i, no. 9. : a monthly magazine'' (1898–1899) (Collection of five speeches, published in the magazine, on the

''Dixon's Sermons : Delivered in the Grand Opera House, New York, 1898-1899''

(1899)

''The Life Worth Living: A Personal Experience''

(1905) * ''The hope of the world; a story of the coming war'' (self-published pamphlet, 1925) * ''The Inside Story of the Harding Tragedy''. New York: The Churchill Company, 1932. With Harry M. Daugherty. * ''A dreamer in Portugal; the story of

Historical Information from Historical Marker Database

* * * *

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Dixon, Thomas Jr. 1864 births 1946 deaths American people of Scottish descent American people of English descent 20th-century American novelists American male screenwriters Southern Baptist ministers Democratic Party members of the North Carolina House of Representatives North Carolina lawyers People from Shelby, North Carolina Wake Forest University alumni Novelists from North Carolina 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights American male novelists Writers of American Southern literature American male dramatists and playwrights Novelists of the Confederacy Screenwriters from North Carolina Kappa Alpha Order Baptists from North Carolina American white supremacists Ku Klux Klan Race-related controversies in literature American Protestant ministers and clergy Johns Hopkins University alumni Lecturers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American screenwriters American anti-communists People born in the Confederate States Neo-Confederates

white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

, Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

minister, politician, lawyer, lecturer, novelist, playwright, and filmmaker. Referred to as a "professional racist", Dixon wrote two best-selling novels, '' The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' (1902) and '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905), that romanticized Southern white supremacy, endorsed the Lost Cause of the Confederacy

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. Fir ...

, opposed equal rights for black people, and glorified the Ku Klux Klan as heroic vigilante

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a person who ...

s. Film director D. W. Griffith adapted ''The Clansman'' for the screen in ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Clan ...

'' (1915). The film inspired the creators of the 20th-century rebirth of the Klan.

Early years

Dixon was born inShelby, North Carolina

Shelby is a city in and the county seat of Cleveland County, North Carolina, United States. It lies near the western edge of the Charlotte combined statistical area. The population was 20,323 at the 2010 census.

History

The area was originally ...

, the son of Thomas Jeremiah Frederick Dixon II and Amanda Elvira McAfee, daughter of a planter and slave-owner from York County, South Carolina

York County is a county in the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 282,090, making it the seventh most populous county in the state. Its county seat is the city of York, and its largest city is Rock Hill. The ...

. He was one of eight children, of whom five survived to adulthood. His elder brother, preacher Amzi Clarence Dixon, helped to edit ''The Fundamentals

''The Fundamentals: A Testimony To The Truth'' (generally referred to simply as ''The Fundamentals'') is a set of ninety essays published between 1910 and 1915 by the Testimony Publishing Company of Chicago. It was initially published quarterly in ...

'', a series of articles (and later volumes) influential in fundamentalist Christianity

Christian fundamentalism, also known as fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism. In its modern form, it began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among British and ...

. "He won international acclaim as one of the greatest ministers of his day." His younger brother Frank Dixon was also a preacher and lecturer. His sister, Elizabeth Delia Dixon-Carroll, became a pioneer woman physician in North Carolina and was the doctor for many years at Meredith College in Raleigh, N.C.

Dixon's father, Thomas J. F. Dixon Sr., son of an English–Scottish father and a German mother, was a well-known Baptist minister and a landowner and slave-owner. His maternal grandfather, Frederick Hambright

Frederick Hambright (May 1, 1727 n.s.– March 9, 1817) was a military officer who fought in both the local militia and in the North Carolina Line of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. He is best known for his participation in th ...

(possible namesake for the fictional North Carolina town of Hambright in which ''The Leopard's Spots'' takes place), was a German Palatine

Palatines (german: Pfälzer), also known as the Palatine Dutch, are the people and princes of Palatinates ( Holy Roman principalities) of the Holy Roman Empire. The Palatine diaspora includes the Pennsylvania Dutch and New York Dutch.

In 1 ...

immigrant who fought in both the local militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and in the North Carolina Line

The North Carolina Line refers to North Carolina units within the Continental Army. The term "North Carolina Line" referred to the quota of infantry regiments assigned to North Carolina at various times by the Continental Congress. These, together ...

of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. Dixon Sr. had inherited slaves and property through his first wife's father, which were valued at $100,000 in 1862.

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him relate to the working man's plight. Dixon grew up after the

In his adolescence, Dixon helped out on the family farms, an experience that he hated, but he would later say that it helped him relate to the working man's plight. Dixon grew up after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, during the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

period. The government confiscation of farmland, coupled with what Dixon saw as the corruption of local politicians, the vengefulness of Union troops, along with the general lawlessness of the period, all served to embitter him, and he became staunchly opposed to the reforms of Reconstruction.

Family involvement in the Ku Klux Klan

Dixon's father, Thomas Dixon Sr., and his maternal uncle, Col. Leroy McAfee, both joined the Klan early in the Reconstruction era with the aim of "bringing order" to the tumultuous times. McAfee was head of the Ku Klux Klan inPiedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, North Carolina. "The romantic colonel made a lasting impression on the boy's imagination", and ''The Clansman'' was dedicated "To the memory of a Scotch-Irish leader of the South, my uncle, Colonel Leroy McAfee, Grand Titan of the Invisible Empire Ku Klux Klan". Dixon claimed that one of his earliest recollections was of a parade of the Ku Klux Klan through the village streets on a moonlit night in 1869, when Dixon was 5. Another childhood memory was of the widow of a Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

soldier. She had served under McAfee accusing a black man of the rape of her daughter and seeking Dixon's family's help. Dixon's mother praised the Klan after it had hanged and shot the alleged rapist in the town square.Roberts, p. 202.

Education

In 1877, Dixon entered the Shelby Academy, where he earned a diploma in only two years. In September 1879, at the age of 15, Dixon followed his older brother and enrolled at the BaptistWake Forest College

Wake Forest University is a private research university in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Founded in 1834, the university received its name from its original location in Wake Forest, north of Raleigh, North Carolina. The Reynolda Campus, the u ...

, where he studied history and political science. As a student, Dixon performed remarkably well. In 1883, after only four years, he earned a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

. His record at Wake Forest was outstanding, and he earned the distinction of achieving the highest student honors ever awarded at the university until then. As a student there, he was a founding member of the chapter of Kappa Alpha Order

Kappa Alpha Order (), commonly known as Kappa Alpha or simply KA, is a social fraternity and a fraternal order founded in 1865 at Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia. As of December 2015, the Kappa Alph ...

fraternity, and delivered the 1883 Salutatory Address with "wit, humor, pathos and eloquence".

"After his graduation from Wake Forest, Dixon received a scholarship to enroll in the political science program at Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

, "then the leading graduate school in the nation". There he met and befriended fellow student and future President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

. Wilson was also a Southerner, and Dixon says in his memoirs that "we became intimate friends.... I spent many hours with him in ilson's room" It is documented that Wilson and Dixon took at least one class together: "As a special student in history and politics he undoubtedly felt the influence of Herbert Baxter Adams

Herbert Baxter Adams (April 16, 1850 – July 30, 1901) was an American educator and historian who brought German rigor to the study of history in America; a founding member of the American History Association; and one of the earliest ed ...

and his circle of Anglo-Saxon historians, who sought to trace American political institutions back to the primitive democracy of the ancient Germanic tribes. The Anglo-Saxonists were staunch racists in their outlook, believing that only latter-day Aryan or Teutonic nations were capable of self-government." But after only one semester, despite the objections of Wilson, Dixon left Johns Hopkins to pursue journalism and a career on the stage.

Dixon headed to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

, and while he tells us in his autobiography that he enrolled briefly at an otherwise unknown Frobisher School of Drama, what he acknowledged publicly was his enrollment in a correspondence course

Distance education, also known as distance learning, is the education of students who may not always be physically present at a school, or where the learner and the teacher are separated in both time and distance. Traditionally, this usually in ...

given by the one-man American School of Playwriting, of William Thompson Price. Apparently as an advertisement for the school, he reproduced in the program

Program, programme, programmer, or programming may refer to:

Business and management

* Program management, the process of managing several related projects

* Time management

* Program, a part of planning

Arts and entertainment Audio

* Progra ...

his handwritten thank-you note.

As an actor, Dixon's physical appearance was a problem. He was but only , making for a very lanky appearance. One producer remarked that he would not succeed as an actor because of his appearance, but Dixon was complimented for his intelligence and attention to detail. The producer recommended that Dixon put his love for the stage into scriptwriting. Despite the compliment, Dixon returned home to North Carolina in shame.

Upon his return to Shelby, Dixon quickly realized that he was in the wrong place to begin to cultivate his playwriting skills. After the initial disappointment from his rejection, Dixon, with the encouragement of his father, enrolled in the short-lived Greensboro Law School, in Greensboro, North Carolina

Greensboro (; formerly Greensborough) is a city in and the county seat of Guilford County, North Carolina, United States. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, third-most populous city in North Carolina after Charlotte, North Car ...

. An excellent student, Dixon received his law degree in 1885.

Political career

It was during law school that Dixon's father convinced Thomas Jr. to enter politics. After graduation, Dixon ran for the local seat in the North Carolina General Assembly as aDemocrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

. Despite being only 20 years of age and too young to vote, he won the 1884 election by a 2-1 margin, a victory that was attributed to his eloquence.Cook, ''Thomas Dixon'', p. 36; Gillespie, ''Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America'' Dixon retired from politics in 1886 after only one term in the legislature. He said that he was disgusted by the corruption and the backdoor deals of the lawmakers, and he is quoted as referring to politicians as "the prostitutes of the masses."Cook, ''Thomas Dixon'', p. 38. However short, Dixon's political career gained him popularity throughout the South as he was the first to champion Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

veterans' rights.Cook, ''Thomas Dixon'', pp. 38-39.

Following his career in politics, Dixon practiced private law for a short time, but he found little satisfaction as a lawyer and soon left the profession to become a minister.

Dixon's thought

Dixon saw himself, and wanted to be remembered as a man of ideas. He described himself as a reactionary. Dixon claimed to be a friend of black people, but he believed that they would never be the equal of whites, who he believed had superior intelligence; according to him, blacks could not benefit much even from the best education. He thought giving them the vote was a mistake, if not a disaster, and the Reconstruction Amendments were "insane". He favored returning black people to Africa, although there were far too many people for this to happen; even the whole U.S. Navy could not keep up with the ones being born, much less the adults. Historian Albert Bushnell Hart indicates the implacability of Dixon's opposition to the advancement of blacks, quoting Dixon: "Make a negro a scientific and successful farmer, and let him plant his feet deep in your soil, and it will mean a race war." In his autobiography, Dixon claims to have personally seen the following: * The Freedmens Bureau arrived in Shelby and told the black people there they could have the franchise (meaning the vote), if they swore to support the constitutions of the United States and North Carolina. The black people then brought to their meetings with the agent enormous baskets, large jugs, huge bags, wheelbarrows, and wagons, as "all" thought the "franchise

Franchise may refer to:

Business and law

* Franchising, a business method that involves licensing of trademarks and methods of doing business to franchisees

* Franchise, a privilege to operate a type of business such as a cable television p ...

" was something tangible.

* He listened as a widow with daughter told his uncle about the rape of her daughter, by a black person who Reconstruction governor William W. Holden had just pardoned and freed from prison. Dixon saw him lynched by the Klan.

* A Freedmens Bureau agent told a former slave of Dixon's grandmother that he was free and could go where he pleased. The man did not want to leave, and when the agent kept repeating his message, threw a hatchet at him, which missed.

* In Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the List of capitals in the United States, capital of the U.S. state of South Carolina. With a population of 136,632 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is List of municipalities in South Carolina, the second-largest ...

, about 1868, he saw "a black driver of a truck strike a little white boy of about six with a whip." The boy's mother rebuked him, so she was arrested, and he followed them into a courtroom where a black magistrate fined her $10 for "insulting a freedman". His uncle and a friend paid the fine for her.

* In the South Carolina House of Representatives

The South Carolina House of Representatives is the lower house of the South Carolina General Assembly. It consists of 124 representatives elected to two-year terms at the same time as U.S. congressional elections.

Unlike many legislatures, seati ...

there were 94 black people and 30 whites, 23 of them not from South Carolina. When he went there, aged 7, he saw that some members were well dressed, "preachers in frock coats". "A lot" were barefooted, "many of them were in overalls covered with red mud", and "the space behind the seats of the members was strewn with corks, broken bottles, stale crusts, greasy pieces of paper and bones picked clean". Without debate the legislature voted the presiding officer $2000 for "the arduous duties...performed this week for the State". A page told Dixon that he was not receiving his $20/day pay. The chamber "reek dof vile cigars and stale whisky", and "the odor of perspiring negroes", which he mentions twice. Karen Crowe finds his memories about this trip "particularly confused"; his chronology is not correct.

* In the elections of 1870, the Klan warned black people in North Carolina who could not read their ballot not to cast it. His uncle was their chief.

In addition, because his uncle was very involved in both the Klan and other local politics—residents funded him to go to Washington on their behalf—he got many reports about other alleged misconduct by black people and their white allies who controlled government in North Carolina.

Dixon had a particular hatred for Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

, leader in the House of Representatives, because he supported land confiscation from whites and its distribution to blacks (see 40 acres and a mule

Forty acres and a mule was part of Special Field Orders No. 15, a wartime order proclaimed by Union General William Tecumseh Sherman on January 16, 1865, during the American Civil War, to allot land to some freed families, in plots of land no la ...

), and according to Dixon wanted "to make the South Negroid territory". Historians do not support many of his charges.

Dixon opposed women having the right to vote. "His prejudices against women are more subtle." "For him, though a woman's real fulfillment lies most assuredly in marriage, the best example of that institution is one in which she takes an equal part."

Dixon was also concerned with threats of communism and war. "Civilization was threatened by socialists, by involvement of the U.S. in European affairs, finally, by communists... He saw civilization as a somewhat fragile quality thing threatened with wreck and ruin from all sides."

Minister

Dixon was ordained as aBaptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

minister on October 6, 1886. That month, church records show that he moved to the parsonage at 125 South John Street in Goldsboro, North Carolina, to serve as the Pastor of the First Baptist Church. Already a lawyer and fresh out of Wake Forest Seminary, life in Goldsboro must not have been what young Dixon had been expecting for a first preaching assignment. The social upheaval that Dixon portrays in his later works was largely melded through Dixon's experiences in the post-war Wayne County during Reconstruction.

On April 10, 1887, Dixon moved to the Second Baptist Church in Raleigh, North Carolina

Raleigh (; ) is the capital city of the state of North Carolina and the seat of Wake County in the United States. It is the second-most populous city in North Carolina, after Charlotte. Raleigh is the tenth-most populous city in the Southe ...

. His popularity rose quickly, and before long, he was offered a position at the large Dudley Street Baptist Church (razed in 1964) in Roxbury, Boston, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. He was unpleasantly surprised to find prejudice there against black people; he always said he was a friend of black people. As his popularity on the pulpit grew, so did the demand for him as a lecturer. While preaching in Boston, Dixon was asked to give the commencement address at Wake Forest University. Additionally, he was offered a possible honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

from the university. Dixon himself rejected the offer, but he sang high praises about a then-unknown man Dixon believed deserved the honor, his old friend Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

. A reporter at Wake Forest who heard Dixon's praises of Wilson put a story on the national wire

Overhead power cabling. The conductor consists of seven strands of steel (centre, high tensile strength), surrounded by four outer layers of aluminium (high conductivity). Sample diameter 40 mm

A wire is a flexible strand of metal.

Wire is c ...

, giving Wilson his first national exposure.

In August 1889, although his Boston congregation was willing to double his pay if he would stay, Dixon accepted a post in New York City. There he would preach at new heights, rubbing elbows with the likes of John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

and Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

(whom he helped in a campaign for New York governor

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor ha ...

). He had "the largest congregation of any Protestant minister in the United States." "As pastor of the Twenty-third Street Baptist Church in New York City…his audiences soon outgrew the church and, pending the construction of a new People's Temple, Dixon was forced to hold services in a neighboring YMCA." Thousands were turned away. John D. Rockefeller

John Davison Rockefeller Sr. (July 8, 1839 – May 23, 1937) was an American business magnate and philanthropist. He has been widely considered the wealthiest American of all time and the richest person in modern history. Rockefeller was ...

offered a $500,000 matching grant for Dixon's dream, "the building of a great temple". However, it never took place.

In 1895, Dixon resigned his position, saying that "for reaching of the non-church-going masses, I am convinced that the machinery of a strict Baptist church is a hindrance", and that he wished for "a perfectly free pulpit". The Board of the church had expressed to him three times their desire to leave Association Hall and return to the church's building; according to them, the crowds attending were not making enough donations to cover the Hall's rental, for which reason there was "a gradual increase of the indebtedness of the church, without any prospect for a change for the better." It was also reported at the time of his resignation that "For a long time past there have been dissensions among the members of the Twenty-Third street Baptist church, due to the objections of the more conservative members of the congregation to the 'sensational' character of the sermons preached during the last five years by the pastor, Rev. Thomas Dixon, Jr." A published letter from "An Old-Fashioned Clergyman" accused him of "sensationalism in the pulpit"; he responded that he was sensationalistic, but this was preferable to "the stupidity, failure, and criminal folly of tradition," an example of which was "putting on women's clothes nondenominational

A non-denominational person or organization is one that does not follow (or is not restricted to) any particular or specific religious denomination.

Overview

The term has been used in the context of various faiths including Jainism, Baháʼí Fait ...

church. He continued preaching there until 1899, when he began to lecture full-time.

When absent giving lectures, "the only man I could find who could hold my big crowd" was socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate of the Soc ...

, who Dixon speaks very highly of.

"While pastor of the People's church icin New York he was once indicted on a charge of criminal libel for his pulpit attacks on city officials. When the warrant of arrest was served on him he set about looking up the records of the members of the grand jury which had indicted him. Then he denounced the jury from his pulpit. The proceedings were dropped."

Lecturer

Dixon was someone "who had something to say to the world and meant to say it." He had "something burning in his heart for utterance." He insisted repeatedly that he was only telling the truth, furnished documentation when challenged, and asked his critics to point out any untruths in his works, even announcing a reward for anyone who could. The reward was not claimed. Dixon enjoyed lecturing, and found it "an agreeable pastime". "Success on the platform was the easiest thing I ever tried." He went on theChautauqua

Chautauqua ( ) was an adult education and social movement in the United States, highly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Chautauqua assemblies expanded and spread throughout rural America until the mid-1920s. The Chautauqua br ...

circuit, and was often hailed as the best lecturer in the nation. He tells us in his autobiography that as a lecturer, "I always spoke without notes after careful preparation". Over four years he was heard by an estimated 5,000,000 attendees, sometimes exceeding 6,000 at a single program. He gained an immense following throughout the country, particularly in the South, where he played up his speeches on the plight of the working man and what he called the horrors of Reconstruction.

About 1896, Dixon had a breakdown caused by overwork. He had lived on 94th St. in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

and on Staten Island, but did not like the weather, "and the doctor had come to see us every week". The doctor said he should "live in the country". Now wealthy, in 1897 Dixon purchased "a stately colonial home, Elmington Manor", in Gloucester County, Virginia

Gloucester County () is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 38,711. Its county seat is Gloucester Courthouse. The county was founded in 1651 in the Virginia Colony and is named for Henry Stuart, ...

. The house had 32 rooms and the grounds were . He had his own post office

A post office is a public facility and a retailer that provides mail services, such as accepting letters and parcels, providing post office boxes, and selling postage stamps, packaging, and stationery. Post offices may offer additional ser ...

, Dixondale. The same year he had an steam yacht

A steam yacht is a class of luxury or commercial yacht with primary or secondary steam propulsion in addition to the sails usually carried by yachts.

Origin of the name

The English steamboat entrepreneur George Dodd (1783–1827) used the term ...

built, which required a crew of "two men and a boy"; he named it Dixie

Dixie, also known as Dixieland or Dixie's Land, is a nickname for all or part of the Southern United States. While there is no official definition of this region (and the included areas shift over the years), or the extent of the area it cover ...

. He says in his autobiography that one year he paid income tax on $210,000. "I felt...I had more money than I could possibly spend."

Becoming a novelist

It was during such a lecture tour that Dixon attended a theatrical version of Harriet Beecher Stowe's ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

''. Dixon could hardly contain his anger and outrage at the play, and it is said that he literally "wept at he play'smisrepresentation of southerners." Dixon vowed that the "true story" of the South should be told. As a direct result of that experience, Dixon wrote his first novel, ''The Leopard's Spots

''The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' is the first novel of Thomas Dixon's Reconstruction trilogy, and was followed by '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905), and '' The Traitor: A ...

'' (1902), which uses several characters, including Simon Legree

Simon may refer to:

People

* Simon (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name Simon

* Simon (surname), including a list of people with the surname Simon

* Eugène Simon, French naturalist and the genu ...

, recycled from Stowe's novel. It and its successor, ''The Clansman

''The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' is a novel published in 1905, the second work in the Ku Klux Klan trilogy by Thomas Dixon Jr. (the others are ''The Leopard's Spots'' and '' The Traitor''). Chronicling the American Civ ...

'', were published by Doubleday, Page & Company

Doubleday is an American publishing company. It was founded as the Doubleday & McClure Company in 1897 and was the largest in the United States by 1947. It published the work of mostly U.S. authors under a number of imprints and distributed th ...

(and contributed significantly to the publisher's success). Dixon turned to Doubleday because he had a "long friendship" with fellow North Carolinian Walter Hines Page

Walter Hines Page (August 15, 1855 – December 21, 1918) was an American journalist, publisher, and diplomat. He was the United States ambassador to the United Kingdom during World War I.

He founded the ''State Chronicle'', a newspaper in Rale ...

. Doubleday accepted ''The Leopard's Spots'' immediately. The entire first edition was sold before it was printed—"an unheard of thing for a first novel". It sold over 100,000 copies in the first 6 months, and the reviews were "generous beyond words".

Dixon as novelist

Dixon turned to writing books as a way to present his ideas to an even larger audience. Dixon's "Trilogy of Reconstruction" consisted of ''The Leopard's Spots

''The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' is the first novel of Thomas Dixon's Reconstruction trilogy, and was followed by '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905), and '' The Traitor: A ...

'' (1902), ''The Clansman

''The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' is a novel published in 1905, the second work in the Ku Klux Klan trilogy by Thomas Dixon Jr. (the others are ''The Leopard's Spots'' and '' The Traitor''). Chronicling the American Civ ...

'' (1905), and '' The Traitor'' (1907). (In his autobiography, he says that in creating trilogies, he was following the model of Polish novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz.) Dixon's novels were best-sellers in their time, despite being racist pastiches of historical romance

Historical romance is a broad category of mass-market fiction focusing on romantic relationships in historical periods, which Walter Scott helped popularize in the early 19th century.

Varieties Viking

These books feature Vikings during the Dar ...

fiction. They glorify an antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ...

American South white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

viewpoint. Dixon claimed to oppose slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, but he espoused racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

and vehemently opposed universal suffrage and miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

. He was "a spokesman for southern Jim Crow segregation and for American racism in general. Yet he did nothing more than reiterate the comments of others."

Dixon's Reconstruction-era novels depict Northerners as greedy carpetbaggers

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the l ...

and white Southerners as victims. Dixon's ''Clansman'' caricatures the Reconstruction as an era of "black rapists" and "blonde-haired" victims, and if his racist opinions were unknown, the vile and gratuitous brutality and Klan terror in which the novel revels might be read as satire

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming ...

. If "Dixon used the motion picture as a propaganda tool for his often outrageous opinions on race, communism, socialism, and feminism," D. W. Griffith, in his movie adaptation of the novel, ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Clan ...

'' (1915), is a case in point. Dixon wrote a highly successful stage adaptation of ''The Clansman'' in 1905. In ''The Leopard's Spots'', the Reverend Durham character indoctrinates Charles Gaston, the protagonist, with a foul-mouthed diatribe of hate speech. One critic notes that the term for marriage, "the Holy of Holies", may be a crude euphemism for the vagina

In mammals, the vagina is the elastic, muscular part of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vestibule to the cervix. The outer vaginal opening is normally partly covered by a thin layer of mucosal tissue called the hymen ...

. Equally, Dixon's opposition to miscegenation seemed to be as much about confused sexism as it was about racism, as he opposed relationships between white women and black men but not between black women and white men.

Another pet hate for Dixon and the focus of another trilogy was socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

: '' The One Woman: A Story of Modern Utopia'' (1903), '' Comrades: A Story of Social Adventure in California'' (1909), and '' The Root of Evil'' (1911), the latter of which also discusses some of the problems involved in modern industrial capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

. The book ''Comrades'' was made into a motion picture, entitled '' Bolshevism on Trial'', released in 1919. In the play ''The Sins of the Father'', which was produced in 1910–1911, Dixon himself played the leading role.

Dixon wrote 22 novels, as well as many plays, sermons, and works of non-fiction. W.E.B. DuBois said he was more widely read than Henry James

Henry James ( – ) was an American-British author. He is regarded as a key transitional figure between literary realism and literary modernism, and is considered by many to be among the greatest novelists in the English language. He was the ...

. His writing centered on three major themes: racial purity, the evils of socialism, and the traditional family role of woman as wife and mother. (Dixon opposed female suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

.) A common theme found in his novels is violence against white women, mostly by Southern black men. The crimes are almost always avenged through the course of the story, the source of which might stem from a belief of Dixon's that his mother had been sexually abused as a child. He wrote his last novel, ''The Flaming Sword'', in 1939 and not long after was disabled by a cerebral hemorrhage.Gillespie, ''Thomas Dixon Jr. and the Birth of Modern America''; Davenport, F. Garvin. ''Journal of Southern History'', August 1970.

While ''The Birth of a Nation'' is still viewed for its crucial role in the birth of the feature film

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

, none of Dixon's novels have stood the test of time. In 1925, when ''Publishers Weekly'' documented the best-selling fiction of the past quarter century, no novel by Dixon was included."

Dixon as playwright

Dixon would not be happy to learn that he is mainly remembered as a novelist. He saw himself as a man of ideas above all, and if he wrote fiction, it was only because at that moment, he considered it the best medium to transmit his ideas to a large public. Making a play of ''The Clansman'' would reach twice as many people "and with an emotional power ten times as great as in cold type". In the years between the composition of ''The Clansman'' (1905) and ''The Birth of a Nation'' (1915), Dixon was primarily known as a playwright.Dixon as filmmaker

Turning it into a movie was the next step, reaching more people with even more impact. As he said ''à propos'' of ''The Fall of a Nation'' (1916): the movie "reached more than thirty million people and was, therefore, thirty times more effective than any book I might have written." "Out of the royalties of ''Birth of a Nation'' I bought an orange grove in the heart of movielandollywood

The Odia film industry, colloquially known as Ollywood, is the Odia language Indian film industry, based in Bhubaneshwar and Cuttack in Odisha, India. The name Ollywood is a portmanteau of the words Odia and Hollywood.

Industry

In 1974, the G ...

and built on it the first fully equipped Studio and Laboratory combined which the town had seen. In it I made my second picture and directed it."

Attitudes towards the revived Klan

Dixon was an extremenationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

, chauvinist, racist, reactionary ideologue

An ideology is a set of beliefs or philosophies attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely epistemic, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones." Formerly applied pri ...

, although "at the height of his fame, Dixon might well have been considered a liberal by many." He spoke favorably several times of Jews and Catholics. He distanced himself from the "bigotry" of the revived "second era" Ku Klux Klan, which he saw as "a growing menace to the cause of law and order", and its members "unprincipled marauders" (and they in turn attacked Dixon). It seems that he inferred that the "Reconstruction Klan" members were not bigots. "He condemned the secret organization for ignoring civilized government and encouraging riot, bloodshed, and anarchy." He denounced antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

as "idiocy", pointing out that the mother of Jesus was Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

. "The Jewish race Is the most persistent, powerful, commercially successful race that the world has ever produced." While lauding the "loyalty and good citizenship" of Catholics, he claimed it was the "duty of whites to lift up and help" the supposedly "weaker races."

Family

Dixon married Harriet Bussey on March 3, 1886. The couple eloped to

Dixon married Harriet Bussey on March 3, 1886. The couple eloped to Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico. In the 202 ...

after Bussey's father refused to give his consent to the marriage.Cook, ''Thomas Dixon'', p. 39.

Dixon and Harriet Bussey had three children together: Thomas III, Louise, and Gordon.

Final years

Dixon's final years were not financially comfortable. "He had lost his house on Riverside Drive in New York, which he had occupied for twenty-five years.... His books no longer became...best sellers." The money he earned from his first books he lost on the stock and cotton exchanges in the crash of 1907. "His final venture in the late 1920s was a vacation resort," Wildacres Retreat, inLittle Switzerland, North Carolina

Little Switzerland is an unincorporated community in McDowell and Mitchell counties of North Carolina, United States. It is located along North Carolina Highway 226A (NC 226A) off the Blue Ridge Parkway, directly north of Marion and south o ...

. "After he had spent a vast amount of money on its development, the enterprise collapsed as speculative bubbles in land across the country began to burst before the crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

." He ended his career as an impoverished court clerk in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Harriet died on 29 December 1937, and fourteen months later, on February 26, 1939, Dixon had a debilitating cerebral hemorrhage. Less than a month later, from his hospital bed, Dixon married Madelyn Donovan, an actress thirty years his junior, who had played a role in a film adaptation of ''Mark of the Beast''. She had also been his research assistant on ''The Flaming Sword'', his last novel. The marriage "induced indignation and outrage among his remaining relatives", who viewed her as a "bad woman". She cared for him for the next seven years, taking over his duties as clerk when he could no longer work. He tried to provide for her future financial security, giving her the rights to all his property. He says nothing about her in his autobiography.

Dixon died on April 3, 1946. He is buried, with Madelyn, in Sunset Cemetery in Shelby, North Carolina.

Archival material

The Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. Collection, in the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Gardner-Webb University inBoiling Springs, North Carolina

Boiling Springs is a town in Cleveland County, North Carolina, United States and is located in the westernmost part of the Charlotte metropolitan area, located approximately 50 miles away from the city. As of the 2010 census, the town's popula ...

, contains documents, manuscripts, biographical works, and other materials pertaining to the life and literary career of Thomas Dixon. It also holds fifteen hundred volumes from Dixon's personal book collection and nine paintings which became illustrations in his novels.

Additional archival material is in the Duke University Library

Duke University Libraries is the library system of Duke University, serving the university's students and faculty. The Libraries collectively hold some 6 million volumes.

The collection contains 17.7 million manuscripts, 1.2 million public docume ...

.

List of works

Novels

* ''The Leopard's Spots

''The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' is the first novel of Thomas Dixon's Reconstruction trilogy, and was followed by '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905), and '' The Traitor: A ...

: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' (1902) (Part 1 of the trilogy on Reconstruction)

* '' The One Woman: A Story of Modern Utopia'' (1903) (Part 1 of the trilogy on socialism)

* '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905) (Part 2 of the trilogy on Reconstruction)

* '' The Traitor: A Story of the Fall of the Invisible Empire'' (1907) (Part 3 of the trilogy on Reconstruction)

* '' Comrades: A Story of Social Adventure in California'' (1909) (Part 2 of the trilogy on socialism)

* '' The Root of Evil'' (1911) (Part 3 of the trilogy on socialism) An attack on capitalism

* '' The Sins of the Father: A Romance of the South'' (1912), on miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is the interbreeding of people who are considered to be members of different races. The word, now usually considered pejorative, is derived from a combination of the Latin terms ''miscere'' ("to mix") and ''genus'' ("race") ...

''The Southerner: A Romance of the Real Lincoln''

(1913) (First of three novels on Southern heroes) * ''The Victim: A Romance of the Real Jefferson Davis'' (1914) (Second of three novels on Southern heroes

Text from FadedPage.

* '' The Foolish Virgin: A Romance of Today'' (1915) (opposes emancipation of women) * ''

The Fall of a Nation

''The Fall of a Nation'' is a 1916 American silent drama film directed by Thomas Dixon Jr., and a sequel to the 1915 film ''The Birth of a Nation'', directed by D. W. Griffith. Dixon, Jr. attempted to cash in on the success of the controversia ...

. A Sequel to The Birth of a Nation'' (1916)

''The Way of a Man. A Story of the New Woman''

(1918)

''The Man in Gray. A Romance of North and South''

(1921), on Robert E. Lee (Third of three novels on Southern heroes)

''The Black Hood''

(1924) (on the Ku Klux Klan) * ''The Love Complex'' (1925). Based on ''The Foolish Virgin''. * ''The Sun Virgin'' (1929) (On

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

.)

* ''Companions'' (1931) (Based on The One Woman.)

* '' The Flaming Sword'' (1939), on the dangers of Communism for the United States (in the novel, Communists take over the country)

Theater

* ''From College to Prison'', play, ''Wake Forest Student'', January 1883. * ''The Clansman

''The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' is a novel published in 1905, the second work in the Ku Klux Klan trilogy by Thomas Dixon Jr. (the others are ''The Leopard's Spots'' and '' The Traitor''). Chronicling the American Civ ...

'' (1905). Produced by George H. Brennan. Multiple touring companies simultaneously.

* '' The Traitor'' (1908), written in collaboration with Channing Pollock, whose name got first billing over that of Dixon

* '' The Sins of the Father'' (1909) Antedates 1912 publication of the novel. Dixon toured playing a main part after the actor was killed. "The Dixon family was of the opinion that he was absolutely lousy on stage."

* ''Old Black Joe

"Old Black Joe" is a parlor song by Stephen Foster (1826–1864). It was published by Firth, Pond & Co. of New York in 1860. Ken Emerson, author of the book ''Doo-Dah!'' (1998), indicates that Foster's fictional Joe was inspired by a servant in th ...

'', one act (1912)

* ''The Almighty Dollar'' (1912)

* ''The Leopard's Spots

''The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden—1865–1900'' is the first novel of Thomas Dixon's Reconstruction trilogy, and was followed by '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905), and '' The Traitor: A ...

'' (1913)

* ''The One Woman'' (1918)

* ''The Invisible Foe'' (1918). Written by Walter C. Hackett; produced and directed by Dixon.

* ''The Red Dawn: A Drama of Revolution'' (1919, unpublished)

* ''Robert E. Lee'', a play in five acts (1920)

''A Man of the People. A Drama of Abraham Lincoln''

(1920). "The three-act drama dealt with the Republican National Committee's request that Lincoln stand down as candidate for president at the end of his first term in office and Lincoln's conflict with

George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

. The third-act climax had Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee receiving news of General Sherman's capture of Atlanta. Lincoln reappeared in the epilogue to deliver his second inaugural address." According to IMDb

IMDb (an abbreviation of Internet Movie Database) is an online database of information related to films, television series, home videos, video games, and streaming content online – including cast, production crew and personal biographies, ...

, it had only 15 performancesIMDb cast list

Cinema

* ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Clan ...

'' (1915)

* ''The Fall of a Nation

''The Fall of a Nation'' is a 1916 American silent drama film directed by Thomas Dixon Jr., and a sequel to the 1915 film ''The Birth of a Nation'', directed by D. W. Griffith. Dixon, Jr. attempted to cash in on the success of the controversia ...

'' (1916) (lost)

* '' The Foolish Virgin'' (1916)

* ''The One Woman'' (1918)

* '' Bolshevism on Trial'', based on ''Comrades'' (1919)

* '' Wing Toy'' (1921) (lost)

* '' Where Men Are Men'' (1921)

* '' Bring Him In'' (1921) "Based on a story by H. H. Van Loan."

* ''Thelma

Thelma is a female given name. It was popularized by Victorian writer Marie Corelli who gave the name to the title character of her 1887 novel ''Thelma (novel), Thelma''. It may be related to a Greek word meaning "will, volition" see ''thelema''). ...

'' (1922)

* ''The Mark of the Beast'' (1923) The only film Dixon directed as well as wrote and produced. It is equally important for bringing Madelyn Donovan openly into his life.

* '' The Brass Bowl'' (1924) "Based on the novel by Louis Joseph Vance

Louis Joseph Vance (September 19, 1879 – December 16, 1933) was an American novelist, screenwriter and film producer. He created the popular character Michael Lanyard, a criminal-turned-detective known as The Lone Wolf.

Biography

Louis J ...

."

* ''The Great Diamond Mystery'' (1924) "Based on a story by Shannon Fife

Manning Shannon Fife (February 16, 1888 – May 7, 1972) was an American journalist, humorist and film scenario writer. He worked on at least 86 motion pictures over the silent film era before returning to journalism to write for magazines and n ...

."

* ''The Painted Lady'' (1924) "Based on the Saturday Evening Post story by Larry Evans."

* '' The Foolish Virgin'' (1924) (lost)

* '' Champion of Lost Causes'' (1925) "Based on the ''Flynn's'' magazine story by Max Brand

Frederick Schiller Faust (May 29, 1892 – May 12, 1944) was an American writer known primarily for his Western (genre), Western stories using the pseudonym Max Brand. He (as Max Brand) also created the popular fictional character of young ...

."

* ''The Trail Rider

''The Trail Rider'' is a 1925 American silent Western film directed by W. S. Van Dyke and starring Buck Jones. Based on the 1924 novel ''The Trail Rider: A Romance of the Kansas Range'' by George Washington Ogden, the film is about a trail rid ...

'' (1925) "Based on the novel by George Washington Ogden."

* ''The Gentle Cyclone

''The Gentle Cyclone'' is a 1926 American silent Western comedy film directed by W. S. Van Dyke and starring Buck Jones featuring Oliver Hardy. It was produced and released by the Fox Film Corporation. Even though a 38-second movie trailer has ...

'' (1926) "Based on the Western Story Magazine

''Western Story Magazine'' was a pulp magazine published by Street & Smith, which ran from 1919 to 1949.Doug Ellis, John Locke, and John Gunnison, (editors),''The Adventure House Guide to the Pulps'', Adventure House, 2000. (pp. 311–12). It was ...

story "Peg Leg and Kidnapper" by Frank R. Buckley."

* ''The torch; a story of the paranoiac who caused a great war'' (screenplay, self-published, 1934). On John Brown, who Dixon presents as a madman, receiving "most of the blame for having touched off the 'powder keg' that caused the Civil War."

* ''Nation Aflame

''Nation Aflame'' is a 1937 American drama film. Directed by Victor Halperin, the film stars Noel Madison, Norma Trelvar, and Lila Lee. It was released on October 16, 1937.

Cast list

* Noel Madison as Frank Sandino, aka Sands

* Norma Trelvar as ...

'' (1937)

Non-fiction

''Living problems in religion and social science'' (sermons)

(1889) * ''What is religion? : an outline of vital ritualism : four sermons preached in Association Hall, New York, December 1890'' (1891)

''Dixon on Ingersoll. Ten discourses, delivered in Association Hall, New York. With a Sketch of the Author by Nym Crinkle''

(1892)

''The failure of Protestantism in New York and its causes''

(1896) * ''An open letter from Rev. Thomas Dixon to J.C. Beam. Read it.'' (self-published pamphlet, 1896?) * ''Dixon's sermons. Vol. i, no. i-v. i, no. 4. : a monthly magazine'' (1898) (Pamphlets on the Spanish–American War.) * ''The Free lance. Vol. i, no. 5-v. i, no. 9. : a monthly magazine'' (1898–1899) (Collection of five speeches, published in the magazine, on the

Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

.)

''Dixon's Sermons : Delivered in the Grand Opera House, New York, 1898-1899''

(1899)

''The Life Worth Living: A Personal Experience''

(1905) * ''The hope of the world; a story of the coming war'' (self-published pamphlet, 1925) * ''The Inside Story of the Harding Tragedy''. New York: The Churchill Company, 1932. With Harry M. Daugherty. * ''A dreamer in Portugal; the story of

Bernarr Macfadden

Bernarr Macfadden (born Bernard Adolphus McFadden, August 16, 1868 – October 12, 1955) was an American proponent of physical culture, a combination of bodybuilding with nutritional and health theories. He founded the long-running magazine pu ...

's mission to continental Europe'' (1934)

* ''Southern Horizons : The Autobiography of Thomas Dixon'' (1984)

Articles

* *References

Bibliography

* Republished from * * * * *McGee, Brian R. "The Argument from Definition Revised: Race and Definition in the Progressive Era", pp. 141–158, ''Argumentation and Advocacy'', Vol. 35 (1999) *Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. ''Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1986-1920.'' Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996. *Williamson, Joel. ''A Rage for Order: Black-White Relations in the American South Since Emancipation'', Oxford, 1986. * * * *External links

Historical Information from Historical Marker Database

* * * *

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Dixon, Thomas Jr. 1864 births 1946 deaths American people of Scottish descent American people of English descent 20th-century American novelists American male screenwriters Southern Baptist ministers Democratic Party members of the North Carolina House of Representatives North Carolina lawyers People from Shelby, North Carolina Wake Forest University alumni Novelists from North Carolina 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights American male novelists Writers of American Southern literature American male dramatists and playwrights Novelists of the Confederacy Screenwriters from North Carolina Kappa Alpha Order Baptists from North Carolina American white supremacists Ku Klux Klan Race-related controversies in literature American Protestant ministers and clergy Johns Hopkins University alumni Lecturers 20th-century American male writers 20th-century American screenwriters American anti-communists People born in the Confederate States Neo-Confederates