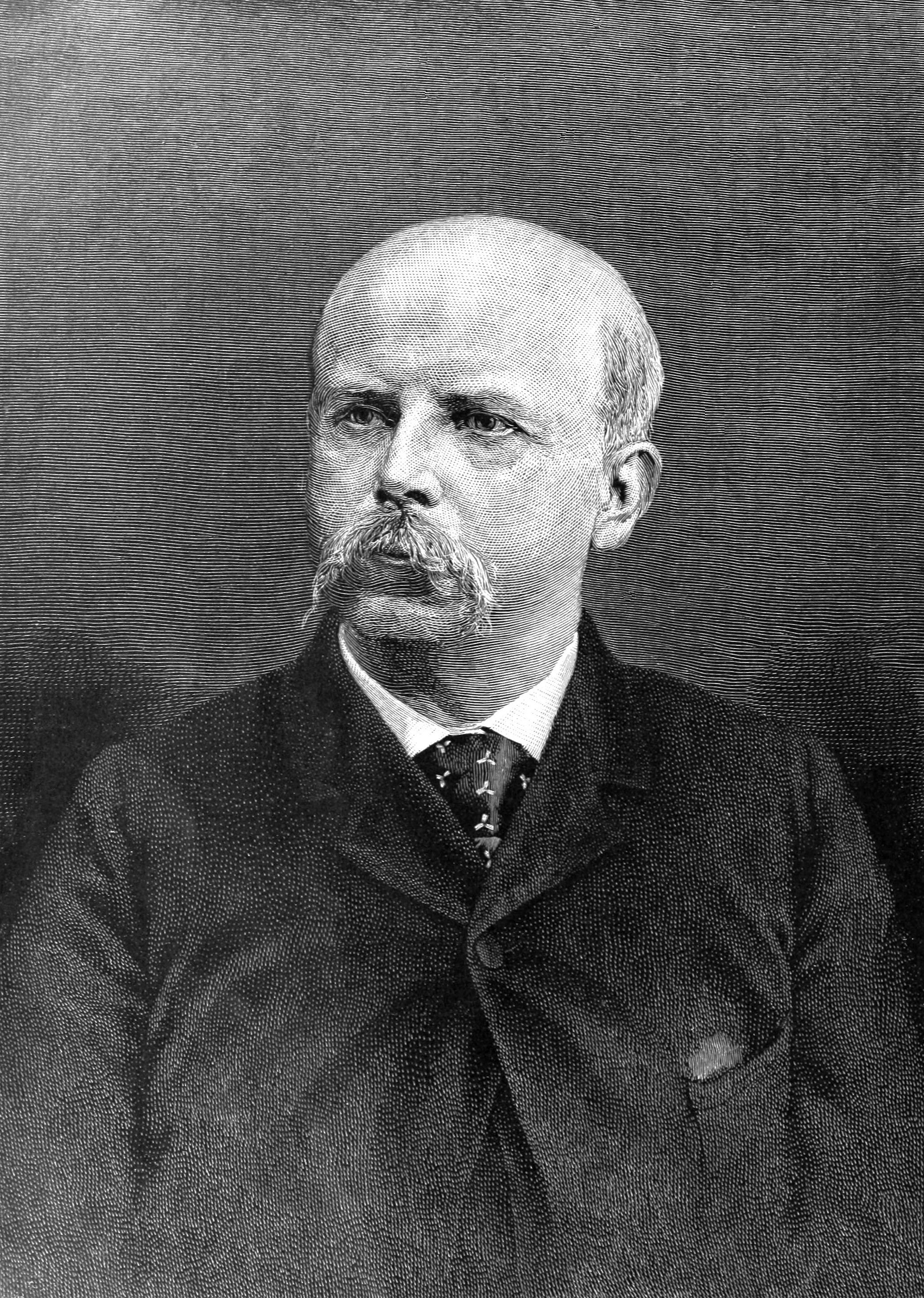

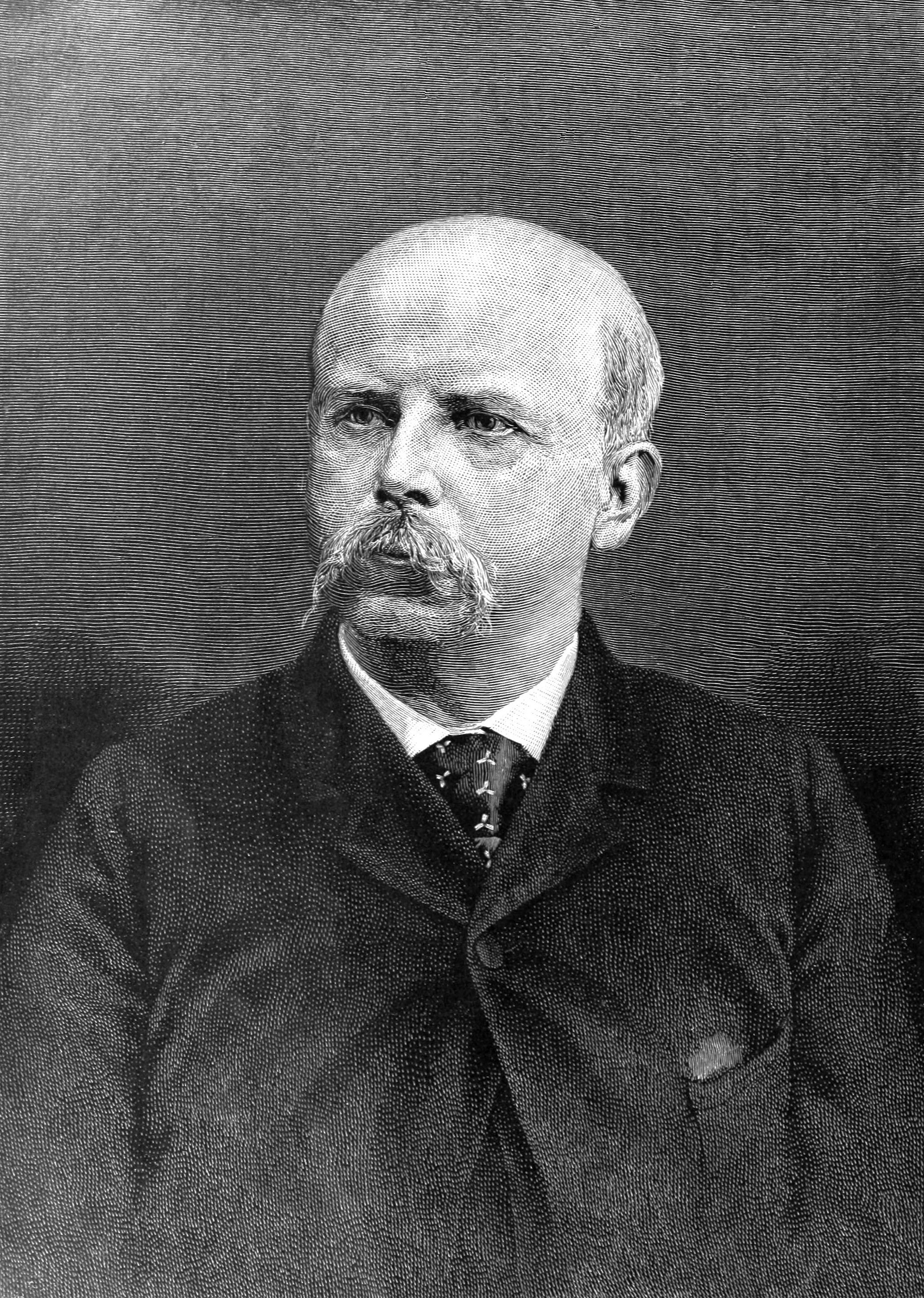

Thomas Corwin Mendenhall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Corwin Mendenhall (October 4, 1841 – March 23, 1924) was an American autodidact

Mendenhall was born in

Mendenhall was born in

The Birth of Ohio Stadium He was later awarded the first ever honorary Ph.D. from The Ohio State University in 1878. In 1878, on the recommendation of

In 1878, on the recommendation of  He became professor at the U.S. Signal Corps in 1884, introducing of systematic observations of

He became professor at the U.S. Signal Corps in 1884, introducing of systematic observations of  Mendenhall was appointed president of the

Mendenhall was appointed president of the

A portrait by famous artist and Columbus, Ohio native George Bellows was commissioned by the Ohio State University in 1913. The largest collection of images, historical documents and handwritten material relating to Thomas Corwin Mendenhall is with Mendenhall family member documentary filmmaker Sybil Drew.

/ref> *Elected a member of the

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

and meteorologist

A meteorologist is a scientist who studies and works in the field of meteorology aiming to understand or predict Earth's atmospheric phenomena including the weather. Those who study meteorological phenomena are meteorologists in research, while t ...

. He was the first professor hired at Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best publ ...

in 1873 and the superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey (now known as NOAA) from 1889 to 1894. Alongside his work, he was also an advocate for the adoption of the metric system by the United States and is the father of author profiling.

Biography

Mendenhall was born in

Mendenhall was born in Hanoverton, Ohio

Hanoverton is a village in western Columbiana County, Ohio, United States. The population was 354 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Salem micropolitan area, miles east of Canton and southwest of Youngstown.

History

Hanoverton was lai ...

, to Stephen Mendenhall, a farmer and carriage-maker, and Mary Thomas. In 1852 the family moved to Marlboro

Marlboro (, ) is an American brand of cigarettes, currently owned and manufactured by Philip Morris USA (a branch of Altria) within the United States and by Philip Morris International (now separate from Altria) outside the US. The largest Mar ...

, a Quaker community outside of Akron, Ohio

Akron () is the fifth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and is the county seat of Summit County. It is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau, about south of downtown Cleveland. As of the 2020 Census, the city prop ...

. His parents were strong abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

s and frequently opened their home to escaped slaves heading north along the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. ...

. Mendenhall became principal of the local primary school in 1858. He formalized his teaching qualifications at National Normal University

National Normal University was a teacher's college in Lebanon, Ohio. Located in southwestern Ohio, it opened in 1855 as Southwestern Normal School and took the name National Normal University in 1870. Alfred Holbrook was the first president a ...

in 1861 with an ''Instructor Normalis

Instructor may refer to:

Education

* Instructor, a teacher of a specialised subject that involves skill:

** Teaching assistant

** Tutor

** Lecturer

** Fellow

** Teaching fellow

*** Teaching associate

*** Graduate student instructor

** Professor

S ...

'' degree.Carey (1999)

While living in Columbus, Ohio, he married Susan Allan Marple in 1870. The couple had one child, Charles Elwood Mendenhall

Charles Elwood Mendenhall (August 1, 1872 – August 18, 1935) was an American physicist and professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Early life

Charles Elwood Mendenhall was born on August 1, 1872, in Columbus, Ohio. He was the so ...

(1872–1935), teacher and chairman of the Physics Department at University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United Stat ...

for 34 years.

He taught at a number of schools in Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

including Central High School in Columbus, gaining an impressive reputation as a teacher and educator. In 1873, although he lacked conventional academic credentials, he was appointed professor of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

and mechanics at the Ohio Agricultural and Mechanical College. The college ultimately became Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best publ ...

, Mendenhall being the first member of the original faculty.The Birth of Ohio Stadium He was later awarded the first ever honorary Ph.D. from The Ohio State University in 1878.

In 1878, on the recommendation of

In 1878, on the recommendation of Edward S. Morse

Edward Sylvester Morse (June 18, 1838 – December 20, 1925) was an American zoologist, archaeologist, and oriental studies, orientalist. He is considered the "Father of Japanese archaeology."

Early life

Morse was born in Portland, Maine, ...

, he was recruited to help the modernization of Meiji Era Japan as one of the ''o-yatoi gaikokujin

The foreign employees in Meiji Japan, known in Japanese as ''O-yatoi Gaikokujin'' ( Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: , "hired foreigners"), were hired by the Japanese government and municipalities for their specialized knowledge and skill to assist in the ...

'' (hired foreigners), serving as visiting professor of physics at Tokyo Imperial University

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

. In connection with this appointment, he founded a meteorological observatory to make systematic observations during his residence in Japan. From measurements using a Kater's pendulum

A Kater's pendulum is a reversible free swinging pendulum invented by British physicist and army captain Henry Kater in 1817 for use as a gravimeter instrument to measure the local acceleration of gravity. Its advantage is that, unlike previous ...

of the force of gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

at sea level and at the summit of Mount Fuji, Mendenhall deduced a value for the mass of the Earth that agreed closely with estimates that Francis Baily

Francis Baily (28 April 177430 August 1844) was an English astronomer. He is most famous for his observations of "Baily's beads" during a total eclipse of the Sun. Baily was also a major figure in the early history of the Royal Astronomical S ...

had made in England by another method. He also made a series of elaborate measurements of the wavelengths of the solar spectrum by means of a large spectrometer

A spectrometer () is a scientific instrument used to separate and measure spectral components of a physical phenomenon. Spectrometer is a broad term often used to describe instruments that measure a continuous variable of a phenomenon where the ...

. He also became interested in earthquakes while in Japan, and was one of the founders of the Seismological Society of Japan (SSJ). During his time in Japan, he also gave public lectures on various scientific topics to general audiences in temples and in theaters.

Returning to Ohio in 1881, Mendenhall was instrumental in developing the Ohio State Meteorological Service. He devised a system of weather signals for display on railroad trains. This method became general throughout the United States and Canada.

He became professor at the U.S. Signal Corps in 1884, introducing of systematic observations of

He became professor at the U.S. Signal Corps in 1884, introducing of systematic observations of lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an avera ...

, and investigating methods for determining ground temperatures. He was the first to establish stations in the United States for the systematic observation of earthquake phenomena. Resigning in 1886, Mendenhall took up the presidency of the Rose Polytechnic Institute

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

in Terre Haute, Indiana before becoming superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1889. During his time as superintendent, he issued the Mendenhall Order

The Mendenhall Order marked a decision to change the fundamental standards of length and mass of the United States from the customary standards based on those of England to metric standards. It was issued on April 5, 1893, by Thomas Corwin Mend ...

and oversaw the consequent transition of the United States's weights and measures

A unit of measurement is a definite magnitude of a quantity, defined and adopted by convention or by law, that is used as a standard for measurement of the same kind of quantity. Any other quantity of that kind can be expressed as a multi ...

from the customary system, based on that of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, to the metric system

The metric system is a system of measurement that succeeded the decimalised system based on the metre that had been introduced in France in the 1790s. The historical development of these systems culminated in the definition of the Interna ...

. Mendenhall remained a strong proponent for the official adoption of the metric system all his life. Also, as superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, he was also responsible for defining the exact national boundary between Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

and Canada. The Mendenhall Valley

The Mendenhall Valley (historically Mendenhall, colloquially The Valley) is the drainage area of the Mendenhall River in the U.S. state of Alaska. The valley contains a series of neighborhoods, comprising the largest populated place within the ...

and Glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

in Juneau, Alaska was named for him in 1892.

Mendenhall invented the portable Mendenhall Gravimeter

Gravimetry is the measurement of the strength of a gravitational field. Gravimetry may be used when either the magnitude of a gravitational field or the properties of matter responsible for its creation are of interest.

Units of measurement

Gr ...

in 1890 while he was superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, and at that time it provided the most accurate relative measurements of the local gravitational field of the Earth. The gravimeters were used at over 340 survey stations across the US and around the world including Germany, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's mos ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, Haiti, Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the ar ...

, Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

, Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

, Canada, and Mexico. The swing of the pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward th ...

was more regular than the most accurate clocks of the era, and as the "world's best clock" it was used by Albert A. Michelson

Albert Abraham Michelson FFRS HFRSE (surname pronunciation anglicized as "Michael-son", December 19, 1852 – May 9, 1931) was a German-born American physicist of Polish/Jewish origin, known for his work on measuring the speed of light and esp ...

to measure the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant that is important in many areas of physics. The speed of light is exactly equal to ). According to the special theory of relativity, is the upper limit ...

, for which he won a Nobel Prize in 1907. An early model of the original 1890s Mendenhall Gravimeter is on display at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

in Washington, D.C.

Mendenhall was appointed president of the

Mendenhall was appointed president of the Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) is a Private university, private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts. Founded in 1865 in Worcester, WPI was one of the United States' first engineering and technology universities and now has 14 ac ...

from 1894 until 1901, when he emigrated to Europe. He returned to the United States in 1912. He was appointed to the board of trustees of the Ohio State University in 1919 and is remembered for his successful efforts to close the College of Homeopathic Medicine and his unsuccessful effort to limit the capacity of Ohio Stadium to 45,000 seats, contending that it would never be able to fill to its design capacity of 63,000 seats. He continued to serve as a trustee until his death at Ravenna, Ohio

Ravenna is a city in Portage County, Ohio, United States. It is located east of Akron. It was formed from portions of Ravenna Township in the Connecticut Western Reserve. The population was 11,323 in the 2020 Census. It is the county seat of Por ...

in 1924.

His portrait is currently part of the Smithsonian Institution National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. It was painted by his former pupil Annie Ware Sabine Siebert, who was the first recipient of a Master of Arts degree from The Ohio State University in 1886, and one of the first women to earn an architecture degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

(MIT) in 188A portrait by famous artist and Columbus, Ohio native George Bellows was commissioned by the Ohio State University in 1913. The largest collection of images, historical documents and handwritten material relating to Thomas Corwin Mendenhall is with Mendenhall family member documentary filmmaker Sybil Drew.

Work on stylometry

In 1887 Mendenhall published one of the earliest attempts atstylometry

Stylometry is the application of the study of linguistic style, usually to written language. It has also been applied successfully to music and to fine-art paintings as well. Argamon, Shlomo, Kevin Burns, and Shlomo Dubnov, eds. The structure o ...

also known as author profiling, the quantitative analysis of writing style. Prompted by a suggestion made by the English mathematician Augustus de Morgan in 1851, Mendenhall attempted to characterize the style of different authors through the frequency distribution

In statistics, the frequency (or absolute frequency) of an event i is the number n_i of times the observation has occurred/recorded in an experiment or study. These frequencies are often depicted graphically or in tabular form.

Types

The cumula ...

of words of various lengths. In this article Mendenhall mentioned the possible relevance of this technique to the Shakespeare authorship question, and several years later the idea was picked up by a supporter of the theory

A theory is a rational type of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the results of such thinking. The process of contemplative and rational thinking is often associated with such processes as observational study or research. Theories may be ...

that Sir Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both n ...

was the true author of the works usually attributed to Shakespeare. He paid for a team of two people to undertake the counting required, but the results did not appear to support the theory. For comparison, in 1901 Mendenhall also had works by Christopher Marlowe analysed, and proponents of the Marlovian theory of Shakespeare authorship welcomed his finding that "in the characteristic curve of his plays Christopher Marlowe agrees with Shakespeare about as well as Shakespeare agrees with himself."

Honors

* Honorary Ph.D. from The Ohio State University, (1878) *Honorary Ph.D. fromUniversity of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

(1887)

*Member of the National Academy of Sciences (1887)

*President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), founded in 1848, is the world's largest general scientific society. It serves 262 affiliated societies and academies of science and engineering, representing 10 million individuals wo ...

(1889)

*The Mendenhall Valley

The Mendenhall Valley (historically Mendenhall, colloquially The Valley) is the drainage area of the Mendenhall River in the U.S. state of Alaska. The valley contains a series of neighborhoods, comprising the largest populated place within the ...

and Mendenhall Glacier in Juneau, Alaska were named for him (1892)Mendendall Glacier Visitor Center home page/ref> *Elected a member of the

American Antiquarian Society

The American Antiquarian Society (AAS), located in Worcester, Massachusetts, is both a learned society and a national research library of pre-twentieth-century American history and culture. Founded in 1812, it is the oldest historical society i ...

in 1895

*Cullum Geographical Medal

The Cullum Geographical Medal is one of the oldest awards of the American Geographical Society. It was established in the will of George Washington Cullum, the vice president of the Society, and is awarded "to those who distinguish themselves by ...

of the American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows from around the ...

(1901)

* Order of the Sacred Treasure, Japan (1911)

*Honorary Ph.D. from Case Western Reserve University (1912)

*Franklin Medal

The Franklin Medal was a science award presented from 1915 until 1997 by the Franklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and the center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the Am ...

(1918)

*Mendenhall Laboratory on the campus of the Ohio State University is named for himAlexander (1926)

Bibliography

* * * *Mendenhall, Thomas Corwin and Drew, Sybil (2017) "An American Scientist In Japan 1878-1881 And Japan Revisited After Thirty Years" ''Jan & Brooklyn'' *Mendenhall, Thomas Corwin and Drew, Sybil (2017) "The Alaska Boundary Line And Twenty Unsettled Miles: The History Of St. Croix River" ''Jan & Brooklyn''Notes

References

;Obituary *''Science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

'', July 11, 1924

Further reading

* * * * *Rubinger, Richard (1989) ''American Scientist in Early Meiji Japan: The Autobiographical Notes of Thomas C. Mendenhall'', *Carey, C. W. (1999) "Mendenhall, Thomas Corwin", ''American National Biography

The ''American National Biography'' (ANB) is a 24-volume biographical encyclopedia set that contains about 17,400 entries and 20 million words, first published in 1999 by Oxford University Press under the auspices of the American Council of Le ...

'', Oxford University Press, 15: 297-298,

* non.(2001) "Mendenhall, Thomas Corwin", ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'', Deluxe CDROM edition

*Hebra, A. & Hebra, A. J. (2003) ''Measure for Measure: The Story of Imperial, Metric, and Other Units''

*Drew, Sybil (2016) ''Self Styled Genius: The Life of Thomas Corwin Mendenhall'' Jan & Brooklyn

External links

* * * Sybil Drew https://www.imdb.com/name/nm3091159/ {{DEFAULTSORT:Mendenhall, Thomas Corwin American meteorologists American seismologists 1841 births 1924 deaths Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences United States Coast and Geodetic Survey personnel Foreign advisors to the government in Meiji-period Japan Foreign educators in Japan American expatriates in Japan Ohio State University trustees Presidents of Worcester Polytechnic Institute Recipients of the Cullum Geographical Medal People from Hanoverton, Ohio 19th-century American physicists 20th-century American physicists Members of the American Antiquarian Society People from Stark County, Ohio Scientists from Ohio Presidents of the American Physical Society