Thomas Brassey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Brassey (7 November 18058 December 1870) was an English civil engineering contractor and manufacturer of building materials who was responsible for building much of the world's railways in the 19th century. By 1847, he had built about one-third of the railways in Britain, and by time of his death in 1870 he had built one in every twenty miles of railway in the world. This included three-quarters of the lines in France, major lines in many other European countries and in Canada, Australia, South America and India. He also built the structures associated with those railways, including docks, bridges, viaducts, stations, tunnels and drainage works.

As well as railway engineering, Brassey was active in the development of steamships, mines, locomotive factories, marine telegraphy, and water supply and sewage systems. He built part of the London sewerage system, still in operation today, and was a major shareholder in

Thomas Brassey was educated at home until the age of 12, when he was sent to The King's School in Chester. Aged 16, he became an articled

Thomas Brassey was educated at home until the age of 12, when he was sent to The King's School in Chester. Aged 16, he became an articled

Following the success of the early railways in Britain, the French were encouraged to develop a railway network, in the first place to link with the railway system in Britain. To this end the Paris and

Following the success of the early railways in Britain, the French were encouraged to develop a railway network, in the first place to link with the railway system in Britain. To this end the Paris and

In 1852 Brassey took out the largest contract of his career, which was to build the

In 1852 Brassey took out the largest contract of his career, which was to build the

Brassey played a part in helping the British forces to success in the

Brassey played a part in helping the British forces to success in the

In addition to building more railways in Britain and in other European countries, Brassey undertook contracts in other continents. In South America his railways totalled , in Australia , and in India and Nepal .

In 1866 there was a great economic slump, caused by the collapse of the bank of Overend, Gurney and Company, and many of Brassey's colleagues and competitors became insolvent. However, despite setbacks, Brassey survived the crisis and drove ahead with the projects he already had in hand. These included the Lemberg (now

In addition to building more railways in Britain and in other European countries, Brassey undertook contracts in other continents. In South America his railways totalled , in Australia , and in India and Nepal .

In 1866 there was a great economic slump, caused by the collapse of the bank of Overend, Gurney and Company, and many of Brassey's colleagues and competitors became insolvent. However, despite setbacks, Brassey survived the crisis and drove ahead with the projects he already had in hand. These included the Lemberg (now

Brassey's works were not limited to railways and associated structures. In addition to his factories in Birkenhead, he built an engineering works in France to supply materials for his contracts there. He built a number of drainage systems, and a waterworks at

Brassey's works were not limited to railways and associated structures. In addition to his factories in Birkenhead, he built an engineering works in France to supply materials for his contracts there. He built a number of drainage systems, and a waterworks at

In most of Brassey's contracts he worked in partnership with other contractors, in particular with Peto and Betts. The planning of the details of the projects was done by the engineers. Sometimes there would be a consulting engineer and below him another engineer who was in charge of the day-to-day activities. During his career Brassey worked with many engineers, the most illustrious being Robert Stephenson, Joseph Locke and

In most of Brassey's contracts he worked in partnership with other contractors, in particular with Peto and Betts. The planning of the details of the projects was done by the engineers. Sometimes there would be a consulting engineer and below him another engineer who was in charge of the day-to-day activities. During his career Brassey worked with many engineers, the most illustrious being Robert Stephenson, Joseph Locke and

Weston Homes PLC, 25 January 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2017. In 1870 Brassey purchased

accessed 29 January 2007. Walker regards him as "one of the giants of the nineteenth century".

None of his three sons became involved in their father's work and the business was wound up by administrators. The sons created a memorial to their parents in

None of his three sons became involved in their father's work and the business was wound up by administrators. The sons created a memorial to their parents in

accessed 29 January 2007. * * * * * *

Lecture on Joseph Locke and Thomas Brassey

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brassey, Thomas 1805 births 1870 deaths English civil engineering contractors People from Cheshire West and Chester British railway civil engineers British people of the Crimean War

Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "one ...

's '' The Great Eastern'', the only ship large enough at the time to lay the first transatlantic telegraph cable across the North Atlantic, in 1864. He left a fortune of over £5 million, equivalent to about £600 million in 2020.

Background

Thomas Brassey was the eldest son of John Brassey, a prosperous farmer, and his wife Elizabeth, and member of a Brassey family that had been living at Manor Farm in Buerton, a small settlement in the parish ofAldford

Aldford is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Aldford and Saighton, in the county of Cheshire, England. (). The village is approximately to the south of Chester, on the east bank of the River Dee, Wales, River Dee. The Aldf ...

, south of Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

, from at least 1663.

Early years

Thomas Brassey was educated at home until the age of 12, when he was sent to The King's School in Chester. Aged 16, he became an articled

Thomas Brassey was educated at home until the age of 12, when he was sent to The King's School in Chester. Aged 16, he became an articled apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

to a land surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

and agent, William Lawton. Lawton was the agent of Francis Richard Price of Overton, Flintshire

, settlement_type = County

, image_skyline =

, image_alt =

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, image_shield = Arms of Flint ...

. During the time Brassey was an apprentice he helped to survey the new Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

to Holyhead

Holyhead (,; cy, Caergybi , "Cybi's fort") is the largest town and a community in the county of Isle of Anglesey, Wales, with a population of 13,659 at the 2011 census. Holyhead is on Holy Island, bounded by the Irish Sea to the north, and i ...

road (this is now the A5), assisting the surveyor of the road. While he was engaged in this work he met the engineer for the road, Thomas Telford

Thomas Telford FRS, FRSE, (9 August 1757 – 2 September 1834) was a Scottish civil engineer. After establishing himself as an engineer of road and canal projects in Shropshire, he designed numerous infrastructure projects in his native Scot ...

. When his apprenticeship ended at the age of 21, Brassey was taken into partnership by Lawton, forming the firm of "Lawton and Brassey". Brassey moved to Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liv ...

where their business was established. Birkenhead at that time was a very small place; in 1818 it consisted of only four houses. The business flourished and grew, extending into areas beyond land surveying. At the Birkenhead site a brickworks

A brickworks, also known as a brick factory, is a factory for the manufacturing of bricks, from clay or shale. Usually a brickworks is located on a clay bedrock (the most common material from which bricks are made), often with a quarry for ...

and lime kiln

A lime kiln is a kiln used for the calcination of limestone ( calcium carbonate) to produce the form of lime called quicklime (calcium oxide). The chemical equation for this reaction is

: CaCO3 + heat → CaO + CO2

This reaction can take pla ...

s were built. The business either owned or managed sand and stone quarries

A quarry is a type of open-pit mine in which dimension stone, rock, construction aggregate, riprap, sand, gravel, or slate is excavated from the ground. The operation of quarries is regulated in some jurisdictions to reduce their envir ...

in Wirral. Amongst other ventures, the firm supplied the bricks for building the custom house

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting ...

for the port which was developing in the town. Many of the bricks needed for the growing city of Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

were supplied by the brickworks and Brassey devised new methods of transporting his materials, including a system similar to the modern method of pallet

A pallet (also called a skid) is a flat transport structure, which supports goods in a stable fashion while being lifted by a forklift, a pallet jack, a front loader, a jacking device, or an erect crane. A pallet is the structural founda ...

ting, and using a gravity train

A gravity train is a theoretical means of transportation for purposes of commuting between two points on the surface of a sphere, by following a straight tunnel connecting the two points through the interior of the sphere.

In a large body such ...

to take materials from the quarry to the port. When Lawton died, Brassey became sole manager of the company and sole agent and representative for Francis Price. It was during these years that he gained the basic experience for his future career.

Early contracts in Britain

Brassey's first experiences of civil engineering were the construction of of the New Chester Road atBromborough

Bromborough is a town within the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, in Merseyside, England. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Cheshire, it is situated on the Wirral Peninsula, to the south east of Bebington and to the north of East ...

, and the building of a bridge at Saughall Massie

Saughall Massie () is a village on the Wirral Peninsula, Merseyside, England. It is part of the Moreton West & Saughall Massie Ward of the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral and the parliamentary constituency of Wallasey. A small village primarily ...

, on the Wirral. During that time he met George Stephenson

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was a British civil engineer and mechanical engineer. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians

In the history of the United Kingdom and the ...

, who needed stone to build the Sankey Viaduct

The Sankey Viaduct is a railway viaduct in North West England. It is a designated Grade I listed building and has been described as being "the earliest major railway viaduct in the world".

In 1826, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway Company ( ...

on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway (L&MR) was the first inter-city railway in the world. It opened on 15 September 1830 between the Lancashire towns of Liverpool and Manchester in England. It was also the first railway to rely exclusively ...

. Stephenson and Brassey visited a quarry in Storeton

Storeton is a small village on the Wirral Peninsula, England. It is situated to the west of the town of Bebington and is made up of Great Storeton and Little Storeton, which is classified as a hamlet. At the 2001 Census the population of Storeto ...

, a village near Birkenhead, following which Stephenson advised Brassey to become involved in building railways. Brassey's first venture into railways was to submit a tender for building the Dutton Viaduct

Dutton Viaduct is on the West Coast Main Line where it crosses the River Weaver and the Weaver Navigation between the villages of Dutton and Acton Bridge in Cheshire, England (), not far from Dutton Horse Bridge. It is recorded in the Nationa ...

on the Grand Junction Railway

The Grand Junction Railway (GJR) was an early railway company in the United Kingdom, which existed between 1833 and 1846 when it was amalgamated with other railways to form the London and North Western Railway. The line built by the company w ...

, but he lost the contract to William Mackenzie, who had submitted a lower bid. In 1835 Brassey submitted a tender for building the Penkridge Viaduct, further south on the same railway, between Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in th ...

and Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunians ...

, together with of track. The tender was accepted, the work was successfully completed, and the viaduct opened in 1837. Initially the engineer for the line was George Stephenson

George Stephenson (9 June 1781 – 12 August 1848) was a British civil engineer and mechanical engineer. Renowned as the "Father of Railways", Stephenson was considered by the Victorians

In the history of the United Kingdom and the ...

, but he was replaced by Joseph Locke

Joseph Locke FRSA (9 August 1805 – 18 September 1860) was a notable English civil engineer of the nineteenth century, particularly associated with railway projects. Locke ranked alongside Robert Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel as on ...

, Stephenson's pupil and assistant. During this time Brassey moved to Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in th ...

. Penkridge Viaduct still stands and carries trains on the West Coast Main Line

The West Coast Main Line (WCML) is one of the most important railway corridors in the United Kingdom, connecting the major cities of London and Glasgow with branches to Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester and Edinburgh. It is one of the busiest ...

.

On completion of the Grand Junction Railway, Locke moved on to design part of the London and Southampton Railway

The London and Southampton Railway was an early railway company between London and Southampton, in England. It opened in stages from 1838 to 1840 after a difficult construction period, but was commercially successful.

On preparing to serve Por ...

and encouraged Brassey to submit a tender, which was accepted. Brassey undertook work on the section of the railway between Basingstoke

Basingstoke ( ) is the largest town in the county of Hampshire. It is situated in south-central England and lies across a valley at the source of the River Loddon, at the far western edge of The North Downs. It is located north-east of Southa ...

and Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, and on other parts of the line. The following year Brassey won contracts to build the Chester and Crewe Railway with Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS HFRSE FRSA DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of his father ...

as engineer and, with Locke as the engineer, the Glasgow, Paisley and Greenock Railway and the Sheffield and Manchester Railway.

Early contracts in France

Following the success of the early railways in Britain, the French were encouraged to develop a railway network, in the first place to link with the railway system in Britain. To this end the Paris and

Following the success of the early railways in Britain, the French were encouraged to develop a railway network, in the first place to link with the railway system in Britain. To this end the Paris and Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

Railway Company was established, and Locke was appointed as its engineer. He considered that the tenders submitted by French contractors were too expensive, and suggested that British contractors should be invited to tender. In the event only two British contractors took the offer seriously, Brassey and William Mackenzie. Instead of trying to outbid each other they tendered jointly, and their tender was accepted in 1841. This set a pattern for Brassey, who from then on worked in partnership with other contractors in most of his ventures. Between 1841 and 1844 Brassey and Mackenzie won contracts to build four French railways, with a total mileage of , the longest of which was the Orléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and Bordeaux Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

Railway. Following the (US) and Bordeaux Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectu ...

French revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

of 1848 there was a financial crisis in the country and investment in the railways almost ceased. This meant that Brassey had to seek foreign contracts elsewhere.

The collapse of the Barentin Viaduct

In January 1846, during the building of the long Rouen andLe Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

line, one of the few major structural disasters of Brassey's career occurred, the collapse of the Barentin Viaduct

Barentin Viaduct is a railway viaduct that crosses the Austreberthe River on the Paris–Le Havre line near to the town of Barentin, Normandy, France, about from Rouen. It was constructed of brick with 27 arches, high with a total length of ...

. The viaduct was built of brick at a cost of about £50,000 and was high. The reason for the collapse was never established, but a possible cause was the nature of the lime used to make the mortar. The contract stipulated that this had to be obtained locally, and the collapse occurred after a few days of heavy rain. Brassey rebuilt the viaduct at his own expense, this time using lime of his own choice. The rebuilt viaduct still stands and is in use today.

"Railway mania"

During the time Brassey was building the early French railways, Britain was experiencing what was known as the "railway mania

Railway Mania was an instance of a stock market bubble in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in the 1840s. It followed a common pattern: as the price of railway shares increased, speculators invested more money, which further increa ...

", when there was massive investment in the railways. Large numbers of lines were being built, but not all of them were built to Brassey's high standards. Brassey was involved in this expansion but was careful to choose his contracts and investors so that he could maintain his standards. During the one year of 1845 he agreed no less than nine contracts in England, Scotland and Wales, with a mileage totalling over . In 1844 Brassey and Locke began building the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway

The Lancaster and Carlisle Railway was a main line railway opened between those cities in 1846. With its Scottish counterpart, the Caledonian Railway, the Company launched the first continuous railway connection between the English railway netwo ...

of , which was considered to be one of their greatest lines. It passed through the Lune Valley

The River Lune (archaically sometimes Loyne) is a river in length in Cumbria and Lancashire, England.

Etymology

Several elucidations for the origin of the name ''Lune'' exist. Firstly, it may be that the name is Brittonic in genesis and de ...

and then over Shap Fell. Its summit was high and the line had steep gradients, the maximum being 1 in 75. To the south the line linked by way of the Preston–Lancaster line to the Grand Junction Railway. Two important contracts undertaken in 1845 were the Trent Valley Railway

The Trent Valley line is a railway line between Rugby and Stafford in England, forming part of the West Coast Main Line. It is named after the River Trent which it follows. The line was built to provide a direct route from London to North West ...

of and the Chester and Holyhead line of . The former line joined the London and Birmingham Railway

The London and Birmingham Railway (L&BR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom, in operation from 1833 to 1846, when it became part of the London and North Western Railway (L&NWR).

The railway line which the company opened in 1838, betw ...

at Rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

to the Grand Junction Railway south of Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in th ...

providing a line from London to Scotland which bypassed Birmingham. The latter line provided a link between London and the ferries sailing from Holyhead

Holyhead (,; cy, Caergybi , "Cybi's fort") is the largest town and a community in the county of Isle of Anglesey, Wales, with a population of 13,659 at the 2011 census. Holyhead is on Holy Island, bounded by the Irish Sea to the north, and i ...

to Ireland and included Robert Stephenson's tubular Britannia Bridge

Britannia Bridge ( cy, Pont Britannia) is a bridge across the Menai Strait between the island of Anglesey and the mainland of Wales. It was originally designed and built by the noted railway engineer Robert Stephenson as a tubular bridge of w ...

over the Menai Strait

The Menai Strait ( cy, Afon Menai, the "river Menai") is a narrow stretch of shallow tidal water about long, which separates the island of Anglesey from the mainland of Wales. It varies in width from from Fort Belan to Abermenai Point to from ...

. Also in 1845 Brassey received contracts for the Caledonian Railway

The Caledonian Railway (CR) was a major Scottish railway company. It was formed in the early 19th century with the objective of forming a link between English railways and Glasgow. It progressively extended its network and reached Edinburgh an ...

which linked the railway at Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers Eden, Caldew and Petteril. It is the administrative centre of the City ...

with Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

and Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, covering a total distance of and passing over Beattock Summit. His engineer on this project was George Heald. That same year he also began contracts for other railways in Scotland, and in 1846 he started building parts of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway

The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR) was a major British railway company before the 1923 Grouping. It was incorporated in 1847 from an amalgamation of several existing railways. It was the third-largest railway system based in northern ...

between Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

and Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, across the Pennines

The Pennines (), also known as the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of uplands running between three regions of Northern England: North West England on the west, North East England and Yorkshire and the Humber on the east. Common ...

.

A contract for the Great Northern Railway was agreed in 1847, with William Cubitt

Sir William Cubitt FRS (bapt. 9 October 1785 – 13 October 1861) was an eminent English civil engineer and millwright. Born in Norfolk, England, he was employed in many of the great engineering undertakings of his time. He invented a type o ...

as engineer-in-chief, although much of the work was done by William's son Joseph, who was the resident engineer. Brassey was the sole contractor for the line of . A particular problem was met in the marshy country of The Fens

The Fens, also known as the , in eastern England are a naturally marshy region supporting a rich ecology and numerous species. Most of the fens were drained centuries ago, resulting in a flat, dry, low-lying agricultural region supported by a ...

in providing a firm foundation for the railway and associated structures. Brassey was assisted in solving the problem by one of his agents, Stephen Ballard. Rafts or platforms were made of layers of faggot-wood and peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and ...

sods. As these sank, they dispersed the water and so a firm foundation was made. This line is still in use and forms part of the East Coast Main Line

The East Coast Main Line (ECML) is a electrified railway between London and Edinburgh via Peterborough, Doncaster, York, Darlington, Durham and Newcastle. The line is a key transport artery on the eastern side of Great Britain running b ...

. Also in 1847 Brassey began to build the North Staffordshire Railway. By this time the "railway mania" was coming to an end and contracts in Britain were becoming increasingly more difficult to find. By the end of the "railway mania", Brassey had built one-third of all the railways in Britain.

Expansion in Europe

Following the end of the "railway mania" and the drying up of contracts in France, Brassey could have retired as a rich man. Instead he decided to expand his interests, initially in other European countries. His first venture in Spain was theBarcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

and Mataró

Mataró () is the capital and largest town of the ''comarca'' of the Maresme, in the province of Barcelona, Catalonia Autonomous Community, Spain. It is located on the Costa del Maresme, to the south of Costa Brava, between Cabrera de Mar and ...

Railway of in 1848. In 1850 he undertook his first contract in the Italian States, a short railway of , the Prato

Prato ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, Italy, the capital of the Province of Prato. The city lies in the north east of Tuscany, at the foot of Monte Retaia, elevation , the last peak in the Calvana chain. With more than 200,000 ...

and Pistoia

Pistoia (, is a city and ''comune'' in the Italian region of Tuscany, the capital of a province of the same name, located about west and north of Florence and is crossed by the Ombrone Pistoiese, a tributary of the River Arno. It is a ty ...

Railway. This was to lead to bigger contracts in Italy, the next being the Turin–Novara line of in 1853, followed by the Central Italian Railway of . In Norway, with Sir Morton Peto and Edward Betts, Brassey built the Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

to Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Vestland county on the Western Norway, west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the list of towns and cities in Norway, secon ...

Railway of which passes through inhospitable terrain and rises to nearly . In 1852 he resumed work in France with the Mantes and Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Febr ...

Railway of . The Dutch were relatively slow to start building railways but in 1852 with Locke as engineer, Brassey built the Dutch Rhenish Railway

The Dutch Rhenish Railway or Dutch–Rhenish Railway ( nl, 'Nederlandsche Rhijnspoorweg' or ) was a Dutch railway company active from 1845 until 1890.

History

The Dutch Rhenish Railway Company Limited was founded in Amsterdam on 3 July 1845 to t ...

of . Meanwhile, he continued to build lines in England, including the Shrewsbury and Hereford Railway

The Shrewsbury and Hereford Railway was an English railway company that built a standard gauge line between those places. It opened its main line in 1853.

Its natural ally seemed to be the Great Western Railway. With other lines it formed a rout ...

of , the Hereford, Ross and Gloucester Railway of , the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway of and the North Devon Railway

The North Devon Railway was a railway company which operated a line from Cowley Bridge Junction, near Exeter, to Bideford in Devon, England, later becoming part of the London and South Western Railway's system. Originally planned as a broad gaug ...

from Minehead

Minehead is a coastal town and civil parish in Somerset, England. It lies on the south bank of the Bristol Channel, north-west of the county town of Taunton, from the boundary with the county of Devon and in proximity of the Exmoor National ...

to Barnstaple

Barnstaple ( or ) is a river-port town in North Devon, England, at the River Taw's lowest crossing point before the Bristol Channel. From the 14th century, it was licensed to export wool and won great wealth. Later it imported Irish wool, bu ...

of .

The Grand Trunk Railway of Canada

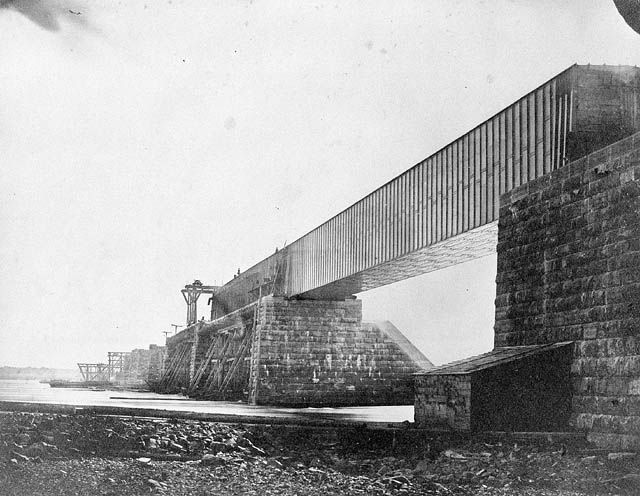

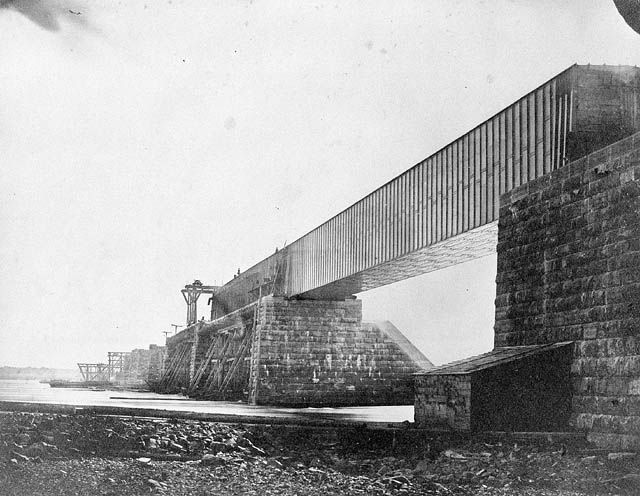

In 1852 Brassey took out the largest contract of his career, which was to build the

In 1852 Brassey took out the largest contract of his career, which was to build the Grand Trunk Railway

The Grand Trunk Railway (; french: Grand Tronc) was a railway system that operated in the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and in the American states of Connecticut, Maine, Michigan, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont. The rail ...

of Canada. This line passed from Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

, along the valley of the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

, and then to the north of Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

to Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the anch ...

. The line totalled in length. The consulting engineer for the project was Robert Stephenson and the company's engineer for the whole undertaking was Alexander Ross. Brassey worked in partnership with Peto, Betts and Sir William Jackson. The line crossed the river at Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

by the Victoria Bridge. This was a tubular bridge designed by Robert Stephenson and was the longest bridge in the world at the time, measuring some . The bridge opened in 1859 and the formal opening ceremony was carried out the following year by the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

. The construction of the line caused considerable problems. The main problem was the raising of the necessary finance and at one stage Brassey travelled to Canada to appeal personally for assistance. Other difficulties arose from the severity of the Canadian winter, the waterways being frozen for around six months each year, and resistance from Canadian businessmen. The line was an engineering success but a financial failure, with the contractors losing £1 million.

The Canada Works

The contract for the Grand Trunk Railway included all the materials required for building the bridge and the railway, including therolling stock

The term rolling stock in the rail transport industry refers to railway vehicles, including both powered and unpowered vehicles: for example, locomotives, freight and passenger cars (or coaches), and non-revenue cars. Passenger vehicles ca ...

. To manufacture the metallic components, Brassey built a new factory in Birkenhead which he called ''The Canada Works''. A suitable site was found by George Harrison, Brassey's brother-in-law, and the factory was built with a quay alongside to take ocean-going ships. The works was managed by George Harrison with a Mr. Alexander and William Heap as assistants. The machine

A machine is a physical system using power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolecul ...

shop was in length and included a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, gr ...

s' shop with 40 furnaces, anvil

An anvil is a metalworking tool consisting of a large block of metal (usually forged or cast steel), with a flattened top surface, upon which another object is struck (or "worked").

Anvils are as massive as practical, because the higher ...

s and steam hammer

A steam hammer, also called a drop hammer, is an industrial power hammer driven by steam that is used for tasks such as shaping forgings and driving piles. Typically the hammer is attached to a piston that slides within a fixed cylinder, but ...

s, a coppersmith

A coppersmith, also known as a brazier, is a person who makes artifacts from copper and brass. Brass is an alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an ...

s' shop, and fabrication, woodwork

Woodworking is the skill of making items from wood, and includes cabinet making (cabinetry and furniture), wood carving, joinery, carpentry, and woodturning.

History

Along with stone, clay and animal parts, wood was one of the first mater ...

and pattern

A pattern is a regularity in the world, in human-made design, or in abstract ideas. As such, the elements of a pattern repeat in a predictable manner. A geometric pattern is a kind of pattern formed of geometric shapes and typically repeated li ...

shops. There was also a well-stocked library and a reading room for all the workforce.

The fitting shop was designed to manufacture 40 locomotive

A locomotive or engine is a rail transport vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. If a locomotive is capable of carrying a payload, it is usually rather referred to as a multiple unit, motor coach, railcar or power car; the ...

s a year and a total of 300 were produced in the next eight years. The first locomotive, given its trial in May 1854, was named ''Lady Elgin'', after the wife of the Governor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada (french: gouverneure générale du Canada) is the federal viceregal representative of the . The is head of state of Canada and the 14 other Commonwealth realms, but resides in oldest and most populous realm ...

of the time, the Earl of Elgin

Earl of Elgin is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in 1633 for Thomas Bruce, 3rd Lord Kinloss. He was later created Baron Bruce, of Whorlton in the County of York, in the Peerage of England on 30 July 1641. The Earl of Elgin is the h ...

. For the bridge hundreds of thousands of components were required and all were manufactured in Birkenhead or in other English factories to Brassey's specifications. These were all stamped and coded, loaded into ships to be taken to Quebec and then by rail to the site of the bridge for assembly. The central tube of the bridge contained over 10,000 pieces of iron, perforated by holes for half a million rivet

A rivet is a permanent mechanical fastener. Before being installed, a rivet consists of a smooth cylindrical shaft with a head on one end. The end opposite to the head is called the ''tail''. On installation, the rivet is placed in a punched ...

s, and when it was assembled every piece and hole was true.

The Grand Crimean Central Railway

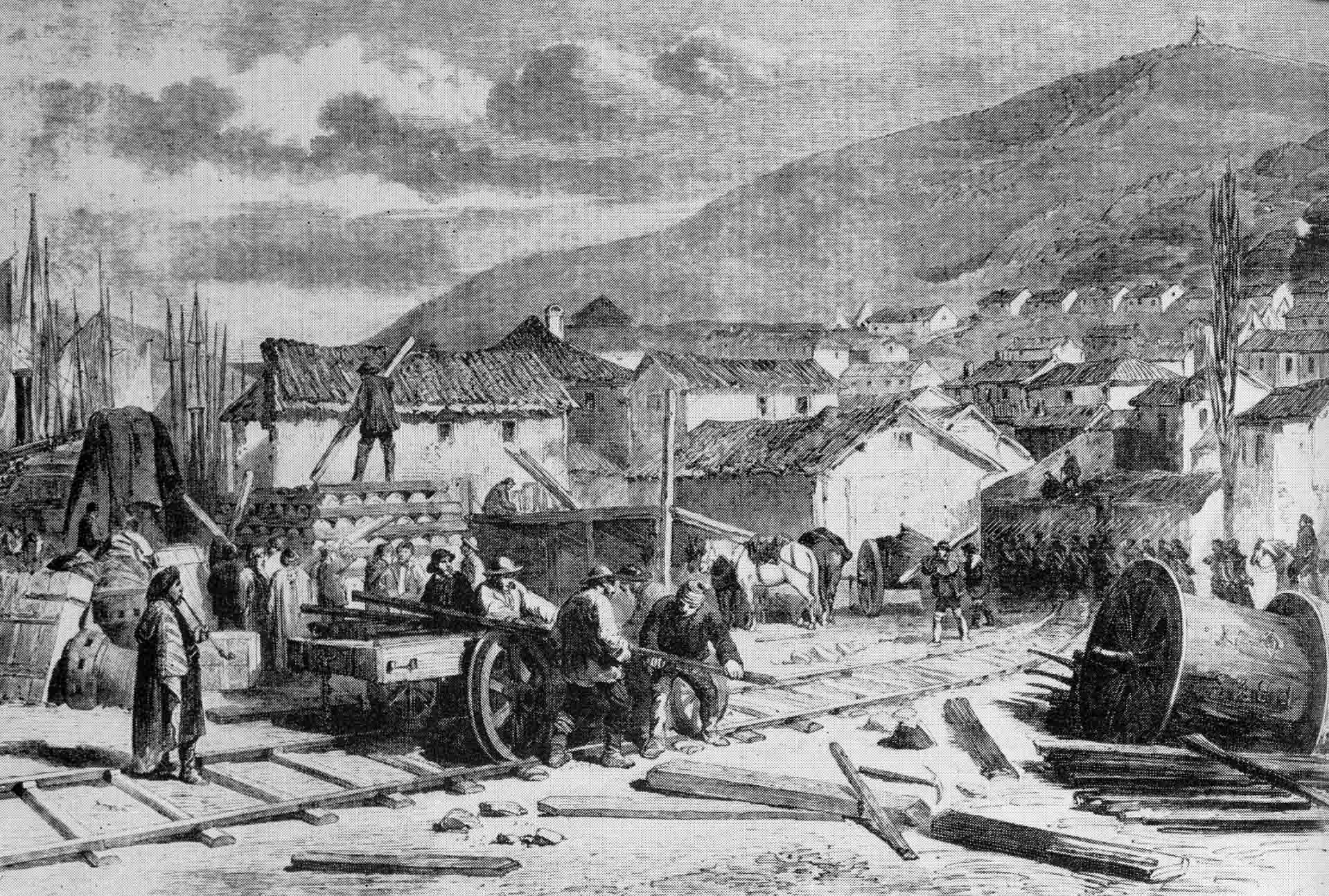

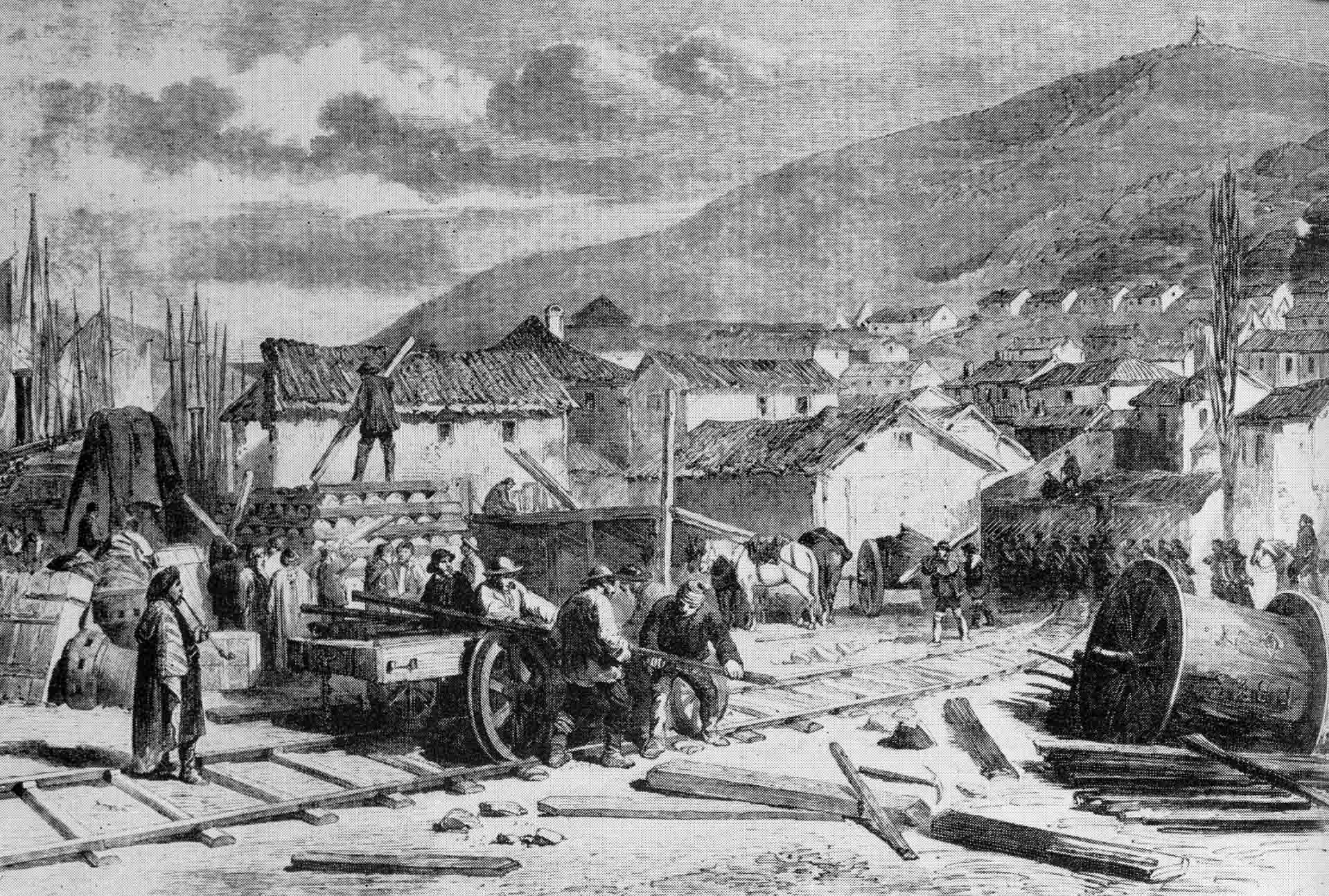

Brassey played a part in helping the British forces to success in the

Brassey played a part in helping the British forces to success in the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

. The Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

port of Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

was held by the Russians. The British government, in alliance with the French and the Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic ...

, sent an army of 30,000 to Balaclava, another port in a neighbouring bay of the Black Sea, from which to attack Sevastopol. Sevastopol was besieged in September 1854 by the British and allied forces. It was hoped that the siege would be short but with the coming of winter the conditions were appalling and it was proving difficult to transport clothing, food, medical supplies and weaponry from Balaclava to the front. When news of the problem arrived in Britain, Brassey joined with Peto

Peto may refer to:

People

* Peto (surname), includes a list of people with the surname Peto

* Kawu Peto Dukku (1958–2010), Nigerian politician, Senator for the Gombe North constituency of Gombe State, Nigeria

Other uses

* PETO, a German party

* ...

and Betts Betts is an English Patronymic surname, deriving from the medieval personal name Bett, a short form of Bartholomew, Beatrice, or Elizabeth. It is also the americanized spelling of German Betz. The surname may refer to

* Alejandro Jacobo Betts (1947 ...

in offering to build a railway ''at cost'' to transport these necessary supplies. They shipped out the equipment and materials for building the railway, which had been intended for other undertakings, together with an army of navvies to carry out the work. Within seven weeks, in severe winter conditions, the railway from Balaclava to the troops besieging Sevastopol was completed. It then became possible to move supplies easily to the front and Sevastopol was finally taken in September 1855.

Worldwide expansion

In addition to building more railways in Britain and in other European countries, Brassey undertook contracts in other continents. In South America his railways totalled , in Australia , and in India and Nepal .

In 1866 there was a great economic slump, caused by the collapse of the bank of Overend, Gurney and Company, and many of Brassey's colleagues and competitors became insolvent. However, despite setbacks, Brassey survived the crisis and drove ahead with the projects he already had in hand. These included the Lemberg (now

In addition to building more railways in Britain and in other European countries, Brassey undertook contracts in other continents. In South America his railways totalled , in Australia , and in India and Nepal .

In 1866 there was a great economic slump, caused by the collapse of the bank of Overend, Gurney and Company, and many of Brassey's colleagues and competitors became insolvent. However, despite setbacks, Brassey survived the crisis and drove ahead with the projects he already had in hand. These included the Lemberg (now Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

) and Czernowicz (now Chernivtsi

Chernivtsi ( uk, Чернівці́}, ; ro, Cernăuți, ; see also other names) is a city in the historical region of Bukovina, which is now divided along the borders of Romania and Ukraine, including this city, which is situated on the u ...

) Railway in Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

(part of Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

) which continued to be constructed despite the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

which was taking place in the locality.

From 1867 Brassey's health was beginning to decline, but he continued to negotiate further contracts, including the Czernowicz and Suczawa Railway in the Austrian Empire. In 1868 he suffered a mild stroke but he continued to work and in April 1869 he embarked on an extensive tour of over in Eastern Europe. By the time of his death he had built one mile in every twenty miles of railway in the world.

Non-railway contracts

Brassey's works were not limited to railways and associated structures. In addition to his factories in Birkenhead, he built an engineering works in France to supply materials for his contracts there. He built a number of drainage systems, and a waterworks at

Brassey's works were not limited to railways and associated structures. In addition to his factories in Birkenhead, he built an engineering works in France to supply materials for his contracts there. He built a number of drainage systems, and a waterworks at Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

. Brassey built docks at Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, located in the west central Lowland ...

, Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liv ...

, Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a port town in Cumbria, England. Historically in Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1867 and merged with Dalton-in-Furness Urban District in 1974 to form the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness. In 2023 t ...

and London. His London docks were the Victoria Docks which had a water area of over . The contract for this was agreed in 1852 in partnership with Peto and Betts and the docks were opened in 1857. Also included in the contract were warehouses and wine vaults totalling an area of about . The dockside machinery was worked by hydraulic

Hydraulics (from Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counte ...

power supplied by William Armstrong. The dock had links to Brassey's London, Tilbury and Southend Railway and thereby to the entire British rail system.

In 1861 Brassey built part of the London sewerage system

The London sewer system is part of the water infrastructure serving London, England. The modern system was developed during the late 19th century, and as London has grown the system has been expanded. It is currently owned and operated by Thames ...

for Joseph Bazalgette. This was a stretch of the Metropolitan Mid Level Sewer of which started at Kensal Green

Kensal Green is an area in north-west London. It lies mainly in the London Borough of Brent, with a small part to the south within Kensington and Chelsea. Kensal Green is located on the Harrow Road, about miles from Charing Cross.

To the w ...

, passed under Bayswater Road

Bayswater Road is the main road running along the northern edge of Hyde Park in London. Originally part of the A40 road, it is now designated part of the A402 road.

Route

In the east, Bayswater Road originates at Marble Arch roadway at ...

, Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major road in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, running from Tottenham Court Road to Marble Arch via Oxford Circus. It is Europe's busiest shopping street, with around half a million daily visitors, and ...

and Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell () is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an ancient parish from the mediaeval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington.

The well after which it was named was redis ...

to the River Lea

The River Lea ( ) is in South East England. It originates in Bedfordshire, in the Chiltern Hills, and flows southeast through Hertfordshire, along the Essex border and into Greater London, to meet the River Thames at Bow Creek. It is one of ...

. It was one of the earliest ventures to use steam cranes. The undertaking was considered to have been one of Brassey's most difficult. The sewer is still in operation today. He also worked with Bazalgette to build the Victoria Embankment

Victoria Embankment is part of the Thames Embankment, a road and river-walk along the north bank of the River Thames in London. It runs from the Palace of Westminster to Blackfriars Bridge in the City of London, and acts as a major thoroughfar ...

on the north bank of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

from Westminster Bridge

Westminster Bridge is a road-and-foot-traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, linking Westminster on the west side and Lambeth on the east side.

The bridge is painted predominantly green, the same colour as the leather seats in the ...

to Blackfriars Bridge

Blackfriars Bridge is a road and foot traffic bridge over the River Thames in London, between Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Railway Bridge, carrying the A201 road. The north end is in the City of London near the Inns of Court and Temple Ch ...

.

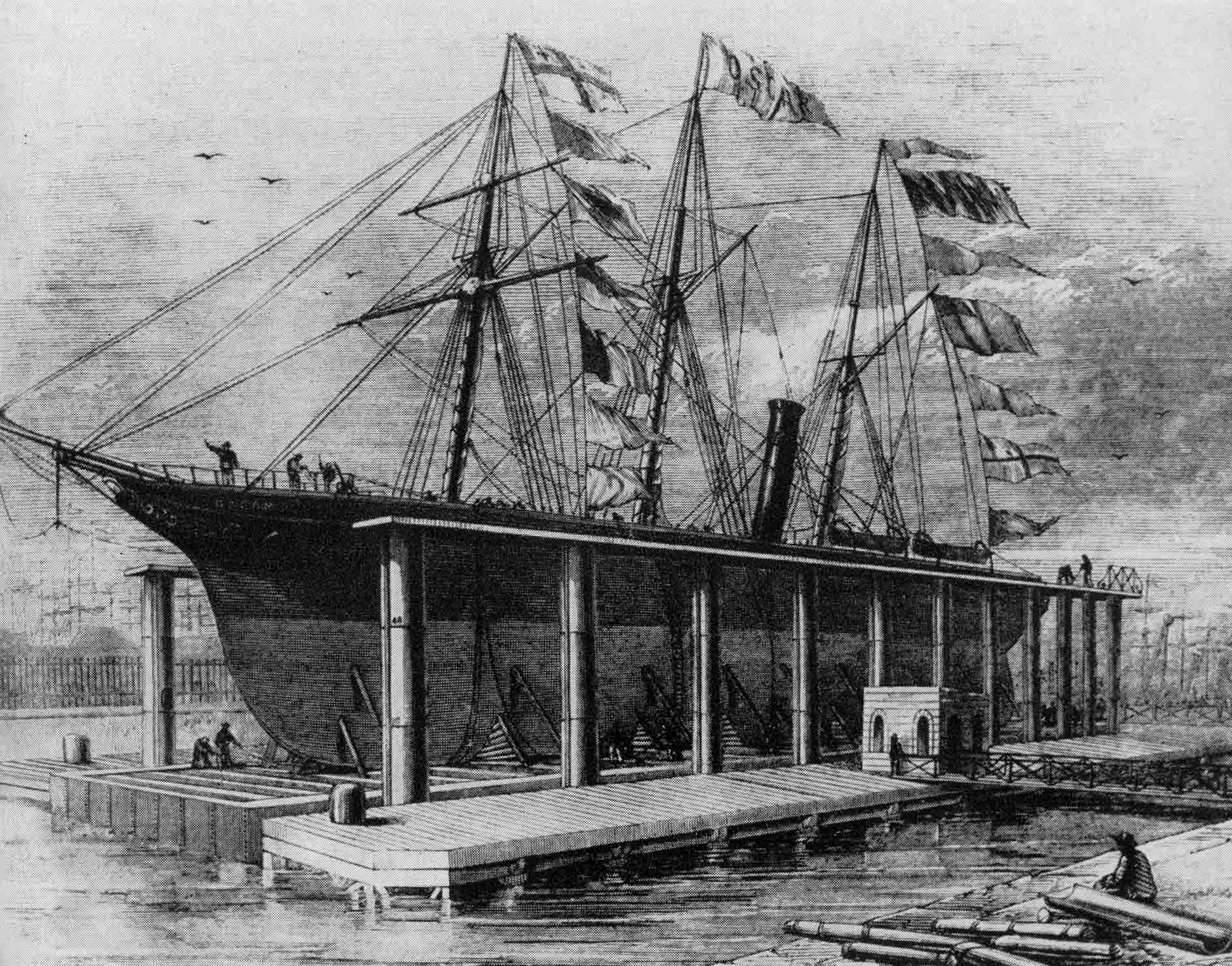

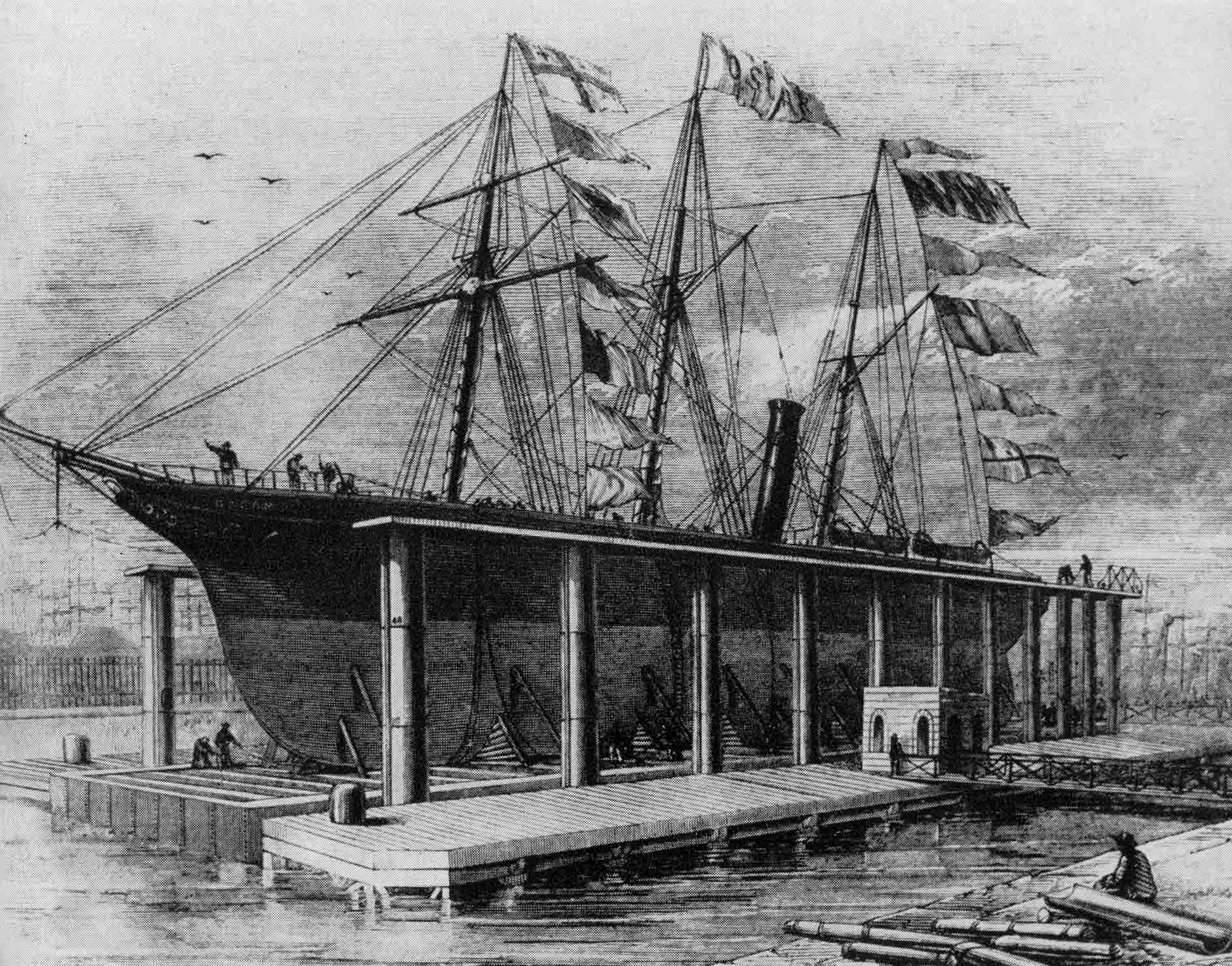

Brassey gave financial help to Brunel to build his ship ''Leviathan'', which was later called '' Great Eastern'' and which in 1854 was six times larger than any other vessel in the world. Brassey was a major shareholder in the ship and after Brunel's death, he, together with Gooch and Barber, bought the ship for the purpose of laying the first Transatlantic telegraph cable

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is now an obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and data a ...

across the North Atlantic in 1864.

Brassey had other ideas which were ahead of his time. He tried to interest the governments of the United Kingdom and Europe in the idea of a tunnel under the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" ( Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), ( Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Ka ...

but this came to nothing. He also wanted to build a canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface f ...

through the Isthmus of Darién (now the Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama ( es, Istmo de Panamá), also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien (), is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country ...

) but this idea similarly had no success.

Working methods

In most of Brassey's contracts he worked in partnership with other contractors, in particular with Peto and Betts. The planning of the details of the projects was done by the engineers. Sometimes there would be a consulting engineer and below him another engineer who was in charge of the day-to-day activities. During his career Brassey worked with many engineers, the most illustrious being Robert Stephenson, Joseph Locke and

In most of Brassey's contracts he worked in partnership with other contractors, in particular with Peto and Betts. The planning of the details of the projects was done by the engineers. Sometimes there would be a consulting engineer and below him another engineer who was in charge of the day-to-day activities. During his career Brassey worked with many engineers, the most illustrious being Robert Stephenson, Joseph Locke and Isambard Kingdom Brunel

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859) was a British civil engineer who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history," "one of the 19th-century engineering giants," and "on ...

. The day-to-day work was overseen by agents, who managed and controlled the activities of the subcontractors.

The actual work was done by labourers, in those days known as navvies

Navvy, a clipping of navigator ( UK) or navigational engineer ( US), is particularly applied to describe the manual labourers working on major civil engineering projects and occasionally (in North America) to refer to mechanical shovels and ea ...

, supervised by gangers (or foremen). In the early days the navvies were mainly English and many of them had formerly worked on building the canals. They were later joined by men from Scotland, Wales and Ireland. The number of Irish workers particularly increased following the Great Famine. Brassey paid his navvies and gangers a wage and provided food, clothing, shelter and, in some projects, a lending library. On overseas contracts local labour would be used if it were available, but the work was often done or supplemented by British workers. The agent on the site had overall responsibility for a project. He had to be a man of great capability, working for a fee plus a percentage of the profits, with penalties for late finishing and inducements to complete the work early.

Brassey had considerable skill in choosing good men to work in this way and in delegating the work. Having taken on a contract at an agreed price he would make a suitable sum of money available to the agent to meet the costs. If the agent were able to fulfil the work at a lower cost he could keep the remainder of the money. If unforeseen problems arose and these were reasonable, Brassey would cover these additional costs. He used hundreds of such agents. At the peak of his career, for well over 20 years, Brassey was employing on average some 80,000 people in many countries in four continents.

Despite this he had neither an office nor office staff, dealing with all the correspondence himself. Much of the detail of his works were held in his memory. He travelled with a personal valet and later had a cashier. But all his letters were written by him; it is recorded that on one occasion after the rest of his party had gone to bed, 31 letters had been written by Brassey overnight. Although he won a large number of contracts, his bids were not always successful. It has been calculated that for every contract awarded, around six others had been unsuccessful.

Brassey was given a number of honours to celebrate his achievements, including the French Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

, the Italian Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus

The Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus ( it, Ordine dei Santi Maurizio e Lazzaro) (abbreviated OSSML) is a Roman Catholic dynastic order of knighthood bestowed by the royal House of Savoy. It is the second-oldest order of knighthood in the ...

and the Austrian Iron Crown (the first time this had been awarded to a foreigner).

Marriage and children

In 1831 he married Maria Harrison, the second daughter of Joseph Harrison, a forwarding and shipping agent with whom he had come into contact during his early days in Birkenhead. Maria gave Thomas considerable support and encouragement throughout his career. She encouraged him to bid for the contract for Dutton Viaduct and, when that was unsuccessful, to apply for the next available contract. Thomas' work led to frequent moves of home in their early years; from Birkenhead toStafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in th ...

, Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames (hyphenated until 1965, colloquially known as Kingston) is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, southwest London, England. It is situated on the River Thames and southwest of Charing Cross. It is notable as ...

, Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

and then Fareham

Fareham ( ) is a market town at the north-west tip of Portsmouth Harbour, between the cities of Portsmouth and Southampton in south east Hampshire, England. It gives its name to the Borough of Fareham. It was historically an important manufac ...

. On each occasion Maria supervised the packing of their possessions and the removal. The Harrison children had been taught to speak French, while Thomas himself was unable to do so. Therefore, when the opportunity arose to apply for the French contracts, Maria was willing to act as interpreter and encouraged Thomas to bid for them. This resulted in moves to Vernon in Normandy, then to Rouen, on to Paris and back again to Rouen. Thomas refused to learn French and Maria acted as interpreter for all his French undertakings. Maria organised the education of their three sons. In time the family established a more-or-less permanent base in Lowndes Square, Belgravia

Belgravia () is a district in Central London, covering parts of the areas of both the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Belgravia was known as the 'Five Fields' during the Tudor Period, and became a danger ...

, London. They had three surviving sons, who all gained distinction in their own right:

*Thomas Brassey, 1st Earl Brassey

Thomas Brassey, 1st Earl Brassey (11 February 1836 – 23 February 1918), was a British Liberal Party politician, Governor of Victoria and founder of '' The Naval Annual''.

Background and education

Brassey was the eldest son of the railway m ...

(1836–1918), eldest son, a Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Plymouth Devonport in Devon (1865) and for Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

in Sussex (1868–86) who served as Governor of Victoria

The governor of Victoria is the representative of the monarch, King Charles III, in the Australian state of Victoria. The governor is one of seven viceregal representatives in the country, analogous to the governors of the other states, and t ...

. He was elevated to the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Be ...

in 1886 as Baron Brassey, "of Bulkeley in the County Palatine of Chester", and in 1911 was created Viscount Hythe, "of Hythe in the County of Kent" and Earl Brassey. His only son Thomas Brassey, 2nd Earl Brassey

Thomas Allnutt Brassey, 2nd Earl Brassey TD, DL, JP, MInstNA, AMICE (7 March 1863 – 12 November 1919), styled Viscount Hythe between 1911 and 1918, was a British peer, who was for many years editor or joint editor of '' Brassey's Naval Ann ...

(1863–1919) died childless when all the titles became extinct.

* Henry Arthur Brassey (1840–1891), DL, of Preston Hall, Aylesford, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

and of Bath House, Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Cour ...

, London, a Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Sandwich

A sandwich is a food typically consisting of vegetables, sliced cheese or meat, placed on or between slices of bread, or more generally any dish wherein bread serves as a container or wrapper for another food type. The sandwich began as a po ...

in Kent. He was the father of Henry Brassey, 1st Baron Brassey of Apethorpe

Henry Leonard Campbell Brassey, 1st Baron Brassey of Apethorpe (7 March 1870 – 22 October 1958), DL (known from 1922 to 1938 as Sir Henry Brassey, 1st Baronet), of Apethorpe Hall in Northamptonshire, was a British Conservative politician.

Or ...

, a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

politician, who was elevated to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

in 1938.

*Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

Albert Brassey

Colonel Albert Brassey (22 February 1844 – 7 January 1918) was a British rowing (sport), rower, soldier and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member of Parliament for Banbury (UK Parliament constituen ...

(1844–1918), a rower

Rowing, sometimes called crew in the United States, is the sport of racing boats using oars. It differs from paddling sports in that rowing oars are attached to the boat using oarlocks, while paddles are not connected to the boat. Rowing is ...

, soldier and Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Banbury

Banbury is a historic market town on the River Cherwell in Oxfordshire, South East England. It had a population of 54,335 at the 2021 Census.

Banbury is a significant commercial and retail centre for the surrounding area of north Oxfordshir ...

1895–1906.

*a fourth son who died in infancy.

Later years

In 1870 Brassey was told that he had cancer but he continued to visit his working sites. One of his last visits was to theWolverhampton and Walsall Railway

The Midland Railway branches around Walsall were built to give the Midland Railway independent access to Wolverhampton, and to a colliery district at Brownhills. The Midland Railway had a stake in the South Staffordshire Railway giving it acces ...

, only a few miles from his first railway contract at Penkridge. In the late summer of 1870 he took to his bed at his home in St Leonards-on-Sea. There he was visited by members of his work force, not only his engineers and agents, but also his navvies, many of whom had walked for days to come and pay their respects.

When Brassey's business friend, Edward Betts, became insolvent in 1867, Brassey bought Betts' estate at Preston Hall, Aylesford in Kent on behalf of his second son, Henry.Preston Hall HistoryWeston Homes PLC, 25 January 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2017. In 1870 Brassey purchased

Heythrop Park

Heythrop Park is a Grade II* listed early 18th-century English country house, country house southeast of Heythrop in Oxfordshire. It was designed by the architect Thomas Archer in the Baroque style for Charles Talbot, 1st Duke of Shrewsbury. A fi ...

, a baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

house situated in an estate of northeast of Oxford as a wedding present for his third son, Albert.

On 8 December 1870 Thomas Brassey died from a brain haemorrhage in Victoria Hotel, St Leonards and was buried in the churchyard of St Laurence's Church, Catsfield, Sussex where a memorial stone has been erected. His estate was valued at £5,200,000 which consisted of "under £3,200,000 in UK" and "over £2,000,000" in a trust fund. The ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' describes him as "one of the wealthiest of the self-made Victorians".

Thomas Brassey, the man

It is not easy to be objective about the nature of Thomas Brassey's character because the earliest biography by Helps was commissioned by the Brassey family and the latest, rather short, biography was written by his great-great-grandson, Tom Stacey. There is virtually no remaining material of value to a biographer available today. There is no private correspondence, there are no diaries and none of his personal reminiscences. Judging by his achievements alone, he must have been a remarkable man. He had enormous drive, an ability to remain calm despite enormous pressures, and extreme skill in organisation. He was a man of honour who always kept his word and his promise. He had no interest in public honours and refused invitations to stand for Parliament. Although he accepted honours from France and Austria, he mislaid the medals and had to request duplicates to please his wife. His great-great-grandson considers that he was successful because he inspired people rather than drove them. Walker, in his 1969 biography, tried to make an accurate assessment of Brassey using Helps and other sources. He found it difficult to discover anyone who had a bad word to say about him, either during his life or since. Brassey expected a high standard of work from his employees; Cooke states that his "standards of quality were fastidious in the extreme". There can be no doubt about some of his qualities. He was exceptionally hardworking, and had an excellent memory and ability to perform mental arithmetic. He was a good judge of men, which enabled him to select the best people to be his agents. He was scrupulously fair with his subcontractors and kind to his navvies, supporting them financially at their times of need. He would at times undertake contracts of little benefit to himself to provide work for his navvies. The only faults which his eldest son could identify were a tendency to praise traits and actions of other people he would condemn in his own family, and an inability to refuse a request. No criticism of him could be found from the engineers with whom he worked, his business associates, his agents or his navvies. He paid his men fairly and generously. The ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'' states "His greatest achievement was to raise the status of the civil engineering contractor to the eminence already attained in the mid-nineteenth century by the engineer".Brooke, David 'Brassey, Thomas (1805–1870)', ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, October 200accessed 29 January 2007. Walker regards him as "one of the giants of the nineteenth century".

Commemorations

None of his three sons became involved in their father's work and the business was wound up by administrators. The sons created a memorial to their parents in

None of his three sons became involved in their father's work and the business was wound up by administrators. The sons created a memorial to their parents in St Erasmus

Erasmus of Formia, also known as Saint Elmo (died c. 303), was a Christian saint and martyr. He is venerated as the patron saint of sailors and abdominal pain. Erasmus or Elmo is also one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers, saintly figures of Chr ...

' Chapel in Chester cathedral

Chester Cathedral is a Church of England cathedral and the mother church of the Diocese of Chester. It is located in the city of Chester, Cheshire, England. The cathedral, formerly the abbey church of a Benedictine monastery dedicated to Sa ...

. This consists of a backcloth to the altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in pagan ...

inscribed to their parents' memory, and a bust

Bust commonly refers to:

* A woman's breasts

* Bust (sculpture), of head and shoulders

* An arrest

Bust may also refer to:

Places

* Bust, Bas-Rhin, a city in France

*Lashkargah, Afghanistan, known as Bust historically

Media

* ''Bust'' (magazin ...

of their father to the north of the altar. The memorial is by Sir Arthur Blomfield

Sir Arthur William Blomfield (6 March 182930 October 1899) was an English architect. He became president of the Architectural Association in 1861; a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1867 and vice-president of the RIBA in ...

and the bust by M. Wagmiller. There is also a bust of Thomas in Chester's Grosvenor Museum and plaques to his memory in Chester station. Streets named after him in Chester are Brassey Street and Thomas Brassey Close (which is off Lightfoot Street). By the waterworks in Boughton, Chester. There are three street names in a row off the main road which spell 'Lord' 'Brassey' of 'Bulkeley'.

In November 2005, Penkridge celebrated the bicentenary of Brassey's birth and a special commemorative train was run from Chester to Holyhead. In January 2007, children from Overchurch Junior School in Upton, Wirral celebrated the life of Brassey. In April 2007 a plaque was placed on Brassey's first bridge at Saughall Massie. In the village of Bulkeley

Bulkeley () is a village and civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. The village is on the A534 road, west of Nantwich. In the 2011 census it had a population of 239.

History

T ...

, near Malpas, Cheshire

Malpas is an ancient market town and a civil parish in the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. Malpas is now referred to as a village after losing its town status. It lies near the borde ...

, is a tree called the 'Brassey Oak' on land once owned by the Brassey family. This was planted to celebrate Thomas' 40th birthday in 1845. It was surrounded by four inscribed sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

pillars tied together by iron rails but due to the growth of the tree these burst and the stones fell. They were recovered and in 2007 were replaced in a more accessible place with an information board.

In 2019 a blue plaque was installed by Conservation Areas Wirral on the remaining structure of his Canada Works building in Beaufort Road, now part of the Wirral Waters area in Birkenhead.

Statue

The Thomas Brassey Society (http://www.thomasbrasseysociety.org) is planning the design and erection of a statue of Thomas Brassey outside Chester Railway Station. Fundraising is underway and currently; Oct 2022; has pledges and donations for some 70% of the sum needed. (http://www.thomasbrasseysociety.org)See also

* List of structures built by Thomas Brassey.References

Notes

Bibliography used for notes

* Brooke, David 'Brassey, Thomas (1805–1870)', ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography