Thomas Abernethy (explorer) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Abernethy (1803 – 13 April 1860) was a Scottish seafarer, gunner in the

Sir William Parry is known for many Arctic naval expeditions, particularly in trying to discover a route for a

Sir William Parry is known for many Arctic naval expeditions, particularly in trying to discover a route for a

In 1827 Parry again took , this time in an attempt to reach the

In 1827 Parry again took , this time in an attempt to reach the

In 1829, Sir John Ross led another Northwest Passage expedition and appointed Abernethy as second mate to join the crew of ''Victory'', a sailing ship and steam paddle steamer of 30

In 1829, Sir John Ross led another Northwest Passage expedition and appointed Abernethy as second mate to join the crew of ''Victory'', a sailing ship and steam paddle steamer of 30  They formed good relations with the local

They formed good relations with the local

On 15 May 1831 Abernethy was on James Ross's team of six which attempted to reach the

On 15 May 1831 Abernethy was on James Ross's team of six which attempted to reach the

A three-strong advance party, including Abernethy, located the scene of ''Fury''s wreckage and the entire expedition was able to use the stores and boats left there and build a substantial shelter, "Somerset House". In July Prince Regent Inlet cleared of ice but by August they found Lancaster Sound completely blocked so they had to return to Fury Beach for the next winter in Somerset House. On 14 August 1833 Abernethy spotted an open lead in the sea ice and so they set off rowing at 4:00 next morning, eventually reaching Cape York (the cape at the northwest point of the

A three-strong advance party, including Abernethy, located the scene of ''Fury''s wreckage and the entire expedition was able to use the stores and boats left there and build a substantial shelter, "Somerset House". In July Prince Regent Inlet cleared of ice but by August they found Lancaster Sound completely blocked so they had to return to Fury Beach for the next winter in Somerset House. On 14 August 1833 Abernethy spotted an open lead in the sea ice and so they set off rowing at 4:00 next morning, eventually reaching Cape York (the cape at the northwest point of the

Sailing east they reached a 200-foot ice cliff which they called the Great Southern Barrier, now the

Sailing east they reached a 200-foot ice cliff which they called the Great Southern Barrier, now the

For more magnetic readings, they left for

For more magnetic readings, they left for

In 1845 Sir

In 1845 Sir

Meeting other search ships off Cape York (the cape on the northwest coast of Greenland), it was found that translations of different local Inuit accounts variously said that nearby Franklin's party had not been seen at all or that everyone had been murdered. At the later official Admiralty Board of Enquiry Abernethy said he had never believed the murder story. Ross credited Abernethy and Charles Phillips with finding the graves of three of Franklin's men near the shore of

Meeting other search ships off Cape York (the cape on the northwest coast of Greenland), it was found that translations of different local Inuit accounts variously said that nearby Franklin's party had not been seen at all or that everyone had been murdered. At the later official Admiralty Board of Enquiry Abernethy said he had never believed the murder story. Ross credited Abernethy and Charles Phillips with finding the graves of three of Franklin's men near the shore of

In 1852, succumbing to public pressure, the Admiralty dispatched five search vessels on a new expedition and Lady Franklin funded a sixth vessel, her own steam yacht ''

In 1852, succumbing to public pressure, the Admiralty dispatched five search vessels on a new expedition and Lady Franklin funded a sixth vessel, her own steam yacht ''

For most of Abernethy's married life he had been away at sea. In 1854 his wife Barbara died, aged 44, with her husband at her side, and Abernethy returned to live in Peterhead. In 1857 he married Rebecca Young but he was only to live for another three years. He died of "ulcersation of the stomach" on 13 April 1860 and his wife erected a gravestone in Peterhead Old Kirkyard. The local newspaper carried a very brief death notice.

According to Alex Buchan, Abernethy's biographer, in the 19th century Royal Naval officers were almost always from the landed gentry and they had purchased their commissions. Certain of their superiority, they wrote accounts of their expeditions keeping the credit for themselves. Indeed, at the end of an expedition, commanders often required any records kept by the crew to be given to them for inclusion at their discretion in the official report. Possibly because of this Abernethy left no written records. According to Sir Joseph Hooker, a distinguished scientist, concerning crewmen, "And where have you seen or heard that their services are in the least appreciated? The Admiralty have not as much as sent a letter of thanks to the men".

Although Abernethy has largely disappeared from history his contributions were sufficiently outstanding for accounts to have been left of him, even though he was neither an officer nor a gentleman. Sir Clements Markham, who had been president of the

For most of Abernethy's married life he had been away at sea. In 1854 his wife Barbara died, aged 44, with her husband at her side, and Abernethy returned to live in Peterhead. In 1857 he married Rebecca Young but he was only to live for another three years. He died of "ulcersation of the stomach" on 13 April 1860 and his wife erected a gravestone in Peterhead Old Kirkyard. The local newspaper carried a very brief death notice.

According to Alex Buchan, Abernethy's biographer, in the 19th century Royal Naval officers were almost always from the landed gentry and they had purchased their commissions. Certain of their superiority, they wrote accounts of their expeditions keeping the credit for themselves. Indeed, at the end of an expedition, commanders often required any records kept by the crew to be given to them for inclusion at their discretion in the official report. Possibly because of this Abernethy left no written records. According to Sir Joseph Hooker, a distinguished scientist, concerning crewmen, "And where have you seen or heard that their services are in the least appreciated? The Admiralty have not as much as sent a letter of thanks to the men".

Although Abernethy has largely disappeared from history his contributions were sufficiently outstanding for accounts to have been left of him, even though he was neither an officer nor a gentleman. Sir Clements Markham, who had been president of the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

, and polar explorer. Because he was neither an officer nor a gentleman, he was little mentioned in the books written by the leaders of the expeditions he went on, but was praised in what was written. In 1857, he was awarded the Arctic Medal for his service as an able seaman on the 1824–25 voyage of HMS Hecla, the first of his five expeditions for which participants were eligible for the award. He was in parties that, for their time, reached the furthest north, the furthest south (twice), and the nearest to the South Magnetic Pole. In 1831, along with James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

's team of six, Abernethy was in the first party ever to reach the North Magnetic Pole

The north magnetic pole, also known as the magnetic north pole, is a point on the surface of Earth's Northern Hemisphere at which the planet's magnetic field points vertically downward (in other words, if a magnetic compass needle is allowed t ...

.

Early and personal life

Thomas Abernethy was born in 1803 atLongside

Longside is a village located in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, consisting of a single main street. It lies seven miles inland from Peterhead and two miles from Mintlaw on the A950. Its population in 2001 was 721. The River Ugie flows through it.

I ...

in northeast Scotland. While he was a child, his family moved to Peterhead

Peterhead (; gd, Ceann Phàdraig, sco, Peterheid ) is a town in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It is Aberdeenshire's biggest settlement (the city of Aberdeen itself not being a part of the district), with a population of 18,537 at the 2011 Census. ...

, a nearby port. His parents were James Abernethy, a stonemason, and Isabella Robertson. Thomas had an elder sister, Ann, who was born in 1801, and twin brothers, James and William, who were both born in 1816. Thomas went to sea at the age of ten and when he was about twelve he was apprenticed as a merchant seaman on the sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

''Friends''. He travelled to the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

and twice to Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

. In 1819, he became a greenhand on the maiden voyage of the Peterhead whaling ship ''Hannibal'', which hunted bowhead whale

The bowhead whale (''Balaena mysticetus'') is a species of baleen whale belonging to the family Balaenidae and the only living representative of the genus '' Balaena''. They are the only baleen whale endemic to the Arctic and subarctic waters, a ...

s around the eastern coast of Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

, and in its third season sailed into the Davis Strait

Davis Strait is a northern arm of the Atlantic Ocean that lies north of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. To the north is Baffin Bay. The strait was named for the English explorer John ...

on the western coast, where ice conditions can be much heavier. In 1829, Abernethy married Barbara Fiddes, the daughter of a ship's carpenter, and they lived at Deptford

Deptford is an area on the south bank of the River Thames in southeast London, within the London Borough of Lewisham. It is named after a Ford (crossing), ford of the River Ravensbourne. From the mid 16th century to the late 19th it was home ...

, southeast London, near the Royal Naval docks. They had no children.

Abernethy was nearly six feet tall and well built – there are no known photographs or portraits of him. He had dark hair and a ruddy complexion. In 1829, John Ross described him as "decidedly the best-looking man in the ship" and he thought that men of his appearance were best able to endure cold. Clements Markham

Sir Clements Robert Markham (20 July 1830 – 30 January 1916) was an English geographer, explorer and writer. He was secretary of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) between 1863 and 1888, and later served as the Society's president for ...

described him as "a handsome man with a well-knit frame, and was resourceful and thoroughly reliable."

Arctic with Parry, 1824–1827

Northwest Passage

Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago

The Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland (an autonomous territory of Denmark).

Situated in the northern extremity of ...

.

For his third attempt, in 1824, Parry took the vessels , under Henry Hoppner and , with Parry himself in command, and Abernethy signed on as one of the 75-strong ''Hecla'' crew. He was an able seaman

An able seaman (AB) is a seaman and member of the deck department of a merchant ship with more than two years' experience at sea and considered "well acquainted with his duty". An AB may work as a watchstander, a day worker, or a combination o ...

, just one rank above ordinary seaman

__NOTOC__

An ordinary seaman (OS) is a member of the deck department of a ship. The position is an apprenticeship to become an able seaman, and has been for centuries. In modern times, an OS is required to work on a ship for a specific amount ...

in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

. Leaving London in May 1824, the expedition reached Lancaster Sound

Lancaster Sound () is a body of water in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located between Devon Island and Baffin Island, forming the eastern entrance to the Parry Channel and the Northwest Passage. East of the sound lies Baffin Bay ...

, but they had to winter at the Brodeur Peninsula

The Brodeur Peninsula is an uninhabited headland on Baffin Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the northwestern part of the island and is bounded by Prince Regent Inlet to the west, Lancaster Sound to the north, a ...

in the northwest part of Baffin Island

Baffin Island (formerly Baffin Land), in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, is the largest island in Canada and the fifth-largest island in the world. Its area is , slightly larger than Spain; its population was 13,039 as of the 2021 Canadia ...

, due to ice. Several shore parties explored the region, but there is no record of Abernethy's involvement. When free of ice, they voyaged down Prince Regent Inlet, but ''Fury'' became wrecked (at Fury Beach) and ''Hecla'', with both crews, returned to London in October 1825. Abernethy was paid off and left the navy to again become a merchant seaman. He was awarded an Arctic Medal for his service when it was instituted in 1857.

Towards North Pole

In 1827 Parry again took , this time in an attempt to reach the

In 1827 Parry again took , this time in an attempt to reach the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

using small boats and sledges. Second in command was James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

and assistant surgeon was Robert McCormick. Abernethy took part, now promoted to the rank of gunnery petty officer. Departing London in March 1827, they sailed to Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in northern Nor ...

where they found a safe anchorage at Sorgfjorden

Sorgfjorden is a fjord at the northeastern coast of Spitsbergen, Svalbard. It cuts into Ny-Friesland, from the northern part of Hinlopen Strait

The Hinlopen Strait ( no, Hinlopenstretet) is the strait between Spitsbergen and Nordaustlandet i ...

, Ny-Friesland

Ny-Friesland is the land area between Wijdefjorden and Hinlopen Strait on Spitsbergen, Svalbard.

The area is named after the Dutch province of Friesland

Friesland (, ; official fry, Fryslân ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia ...

, in the far north. Abernethy participated in the expedition north, but, beset by difficulties, they turned back at 82° 45' N – a record for furthest north that stood for almost fifty years. On the expedition's return Abernethy was enlisted in the Royal Navy on a permanent basis.

Arctic, with John Ross, 1829–1833

Northwest Passage

In 1829, Sir John Ross led another Northwest Passage expedition and appointed Abernethy as second mate to join the crew of ''Victory'', a sailing ship and steam paddle steamer of 30

In 1829, Sir John Ross led another Northwest Passage expedition and appointed Abernethy as second mate to join the crew of ''Victory'', a sailing ship and steam paddle steamer of 30 horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are t ...

. James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

, Ross's nephew, was second-in-command. By October they had reached Prince Regent Inlet

Prince Regent Inlet () is a body of water in Nunavut, Canada between the west end of Baffin Island (Brodeur Peninsula) and Somerset Island on the west. It opens north into Lancaster Sound and to the south merges into the Gulf of Boothia. The Arc ...

and then far south into the Gulf of Boothia

The Gulf of Boothia is a body of water in Nunavut, Canada. Administratively it is divided between the Kitikmeot Region on the west and the Qikiqtaaluk Region on the east. It merges north into Prince Regent Inlet, the two forming a single bay w ...

where they anchored for the winter at Felix Harbour.

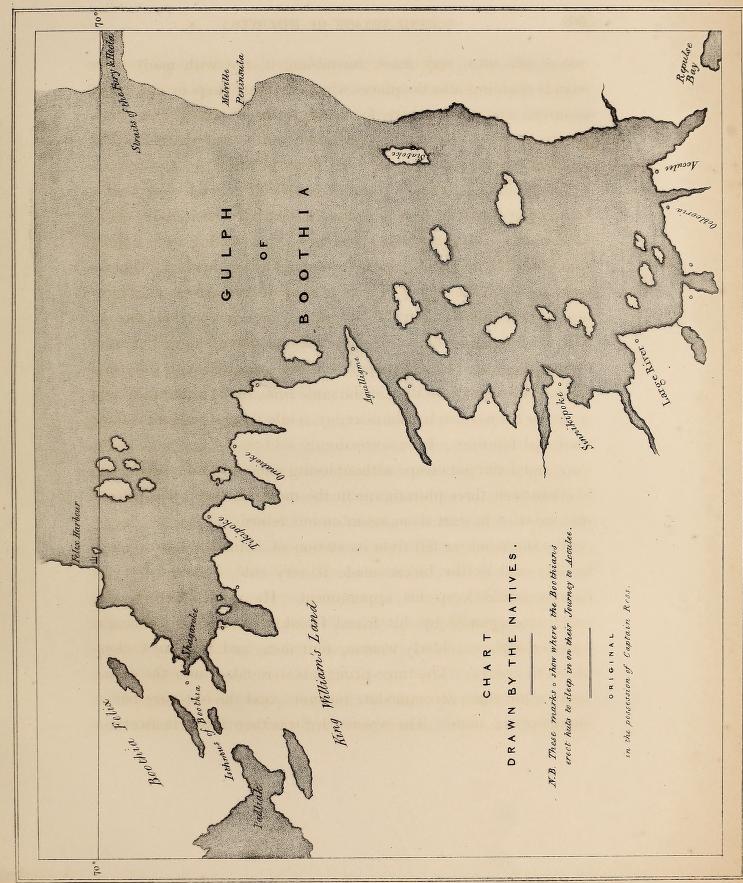

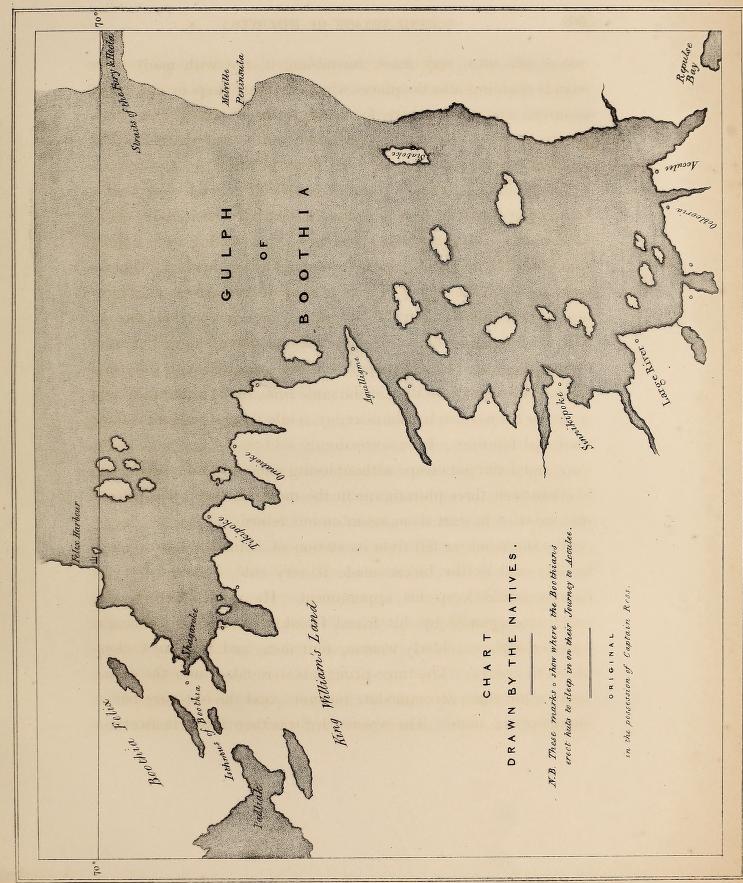

They formed good relations with the local

They formed good relations with the local Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

who drew knowledgeable maps of the region which showed that there was no seaway to the west from where they were, or any further south in the Gulf although there was a narrow strait to the north (Bellot Strait

Bellot Strait is a strait in Nunavut that separates Somerset Island to its north from the Murchison Promontory of Boothia Peninsula to its south, which is the northernmost part of the mainland of the Americas. The and strait connects the Gulf ...

). Following the guidance of the Inuit they experimented with dog sledges and were able to cross the Boothia Peninsula

Boothia Peninsula (; formerly ''Boothia Felix'', Inuktitut ''Kingngailap Nunanga'') is a large peninsula in Nunavut's northern Canadian Arctic, south of Somerset Island. The northern part, Murchison Promontory, is the northernmost point of ...

. A small party led by James Ross, including Abernethy, explored northwards but were unable to locate Bellot Strait. Again James Ross chose Abernethy for a westward expedition starting on 17 May 1830, crossing the Boothia Peninsula and the sea ice of James Ross Strait

James Ross Strait, an arm of the Arctic Ocean, is a channel between King William Island and the Boothia Peninsula in the Canadian territory of Nunavut.

long, and to wide, it connects M'Clintock Channel to the Rae Strait to the south. Islands ...

to King William Island

King William Island (french: Île du Roi-Guillaume; previously: King William Land; iu, Qikiqtaq, script=Latn) is an island in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, which is part of the Arctic Archipelago. In area it is between and making it the 6 ...

, reaching a point at the north of the island which Ross named after Abernethy. They went a way down the northwest coast of the island and then, 200 miles in a direct line from their ship, they returned on 13 June – after a journey of one month they looked like "human skeletons". Abernethy was on another sledging expedition to the south confirming that there was no way out from the Gulf of Boothia in that direction. Only by September could ''Victory'' head north but they only got a few miles before they were frozen in again for the next winter.

North Magnetic Pole

On 15 May 1831 Abernethy was on James Ross's team of six which attempted to reach the

On 15 May 1831 Abernethy was on James Ross's team of six which attempted to reach the North Magnetic Pole

The north magnetic pole, also known as the magnetic north pole, is a point on the surface of Earth's Northern Hemisphere at which the planet's magnetic field points vertically downward (in other words, if a magnetic compass needle is allowed t ...

. They were equipped with a dip circle {{Refimprove, date=November 2011

Dip circles (also ''dip needles'') are used to measure the angle between the horizon and the Earth's magnetic field (the dip angle). They were used in surveying, mining and prospecting as well as for the demonstra ...

and on 1 July they reached where the angle of dip was 89°59'. For two days they retested using different observers at slightly different locations attaining an average 89°59'28" so discovering a slight daily change in the position of the magnetic pole. This was the first time the magnetic pole had been reached and, inevitably, they erected the Union Jack. Ross decided to explore a few miles further north before turning back so he chose Abernethy as his sole companion. On returning to the ship Ross named an island they passed after Abernethy. In 21 days they had travelled about 300 miles and the map they had been able to draw remained the standard for over 100 years.

By late August 1831 ''Victory'' was free of ice but immediately became trapped again. Through the winter they hunted for food – as well as catching seals Abernethy was good at shooting hares and grouse so becoming called "the gamekeeper". By May 1832 they realised there was little hope of the ship becoming free of the ice that year so they left ''Victory'' using their own small boats/sledges hoping to find ''Fury''s boats, abandoned by Parry in 1825.

Return home

A three-strong advance party, including Abernethy, located the scene of ''Fury''s wreckage and the entire expedition was able to use the stores and boats left there and build a substantial shelter, "Somerset House". In July Prince Regent Inlet cleared of ice but by August they found Lancaster Sound completely blocked so they had to return to Fury Beach for the next winter in Somerset House. On 14 August 1833 Abernethy spotted an open lead in the sea ice and so they set off rowing at 4:00 next morning, eventually reaching Cape York (the cape at the northwest point of the

A three-strong advance party, including Abernethy, located the scene of ''Fury''s wreckage and the entire expedition was able to use the stores and boats left there and build a substantial shelter, "Somerset House". In July Prince Regent Inlet cleared of ice but by August they found Lancaster Sound completely blocked so they had to return to Fury Beach for the next winter in Somerset House. On 14 August 1833 Abernethy spotted an open lead in the sea ice and so they set off rowing at 4:00 next morning, eventually reaching Cape York (the cape at the northwest point of the Brodeur Peninsula

The Brodeur Peninsula is an uninhabited headland on Baffin Island in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the northwestern part of the island and is bounded by Prince Regent Inlet to the west, Lancaster Sound to the north, a ...

). At Navy Board Inlet

Navy Board Inlet is a body of water in Nunavut's Qikiqtaaluk Region. It is an arm of Lancaster Sound, after which it proceeds southerly before it empties into Eclipse Sound. It is long and wide.

The inlet separates Baffin Island to the west f ...

, after a spell of 20 hours continuous rowing, a distant sail was spotted so the men rowed on but the ship sailed out of reach. They then spotted a second ship, also sailing away, but they were spotted and rescued by the Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

whaler ''Isabella''. The captain told them they had been given up for dead two years previously "not by them alone, but by all England". By the time they reached Hull, where they received a civic reception, they had been away for four years and 149 days – Abernethy was paid £329:14:8d in back pay at double rates. John Ross wrote of Abernethy "I have no hesitation in recommending him strongly to the Admiralty ..." so they promoted him to HMS ''Seringapatam''. By now James Ross regarded him as an essential member of any future expedition.

Antarctica with James Ross, 1839–1843

Ross Sea, 1839–1841

With James Ross in command of the ships and , three-mastbarque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing vessel with three or more masts having the fore- and mainmasts rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) rigged fore and aft. Sometimes, the mizzen is only partly fore-and-aft rigged, b ...

s, Abernethy set off on a scientific expedition to Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

in 1839, supported by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

, later Sir Joseph but then a young naturalist, took part but because it was a naval expedition he had to be appointed as assistant surgeon. Throughout the expedition a major aim was to take magnetic readings at various ports of call starting with Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

, Tenerife

Tenerife (; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands. It is home to 43% of the total population of the Archipelago, archipelago. With a land area of and a population of 978,100 inhabitant ...

, Cape Verde

, national_anthem = ()

, official_languages = Portuguese

, national_languages = Cape Verdean Creole

, capital = Praia

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, demonym ...

, Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

, St Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

, Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, and the Crozet and Kerguelen

The Kerguelen Islands ( or ; in French commonly ' but officially ', ), also known as the Desolation Islands (' in French), are a group of islands in the sub-Antarctic constituting one of the two exposed parts of the Kerguelen Plateau, a large ...

islands. In a storm the boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, is the most senior rate of the deck department and is responsible for the components of a ship's hull. The boatswain supervis ...

was swept off ''Erebus'' so two boats were launched to rescue him, unsuccessfully. Abernethy was in command of one boat but, just as it got back to ''Erebus'', the other boat was hit by a wave and all four crew were washed overboard. Abernethy cast off again and was able to rescue them.

When they reached Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/ Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

they learned that the Wilkes expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

and D'Urville expedition had already sighted Antarctica so Ross decided to explore a different unknown region. McCormick (from Parry's north polar days) who was ships' surgeon and Abernethy became close associates – and in New Zealand the pair collected natural history specimens. Ross chose 170°E as the longitude to follow south and this turned out to be the future usual route for Antarctic voyages. The ships headed into what became known as the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

reaching pack ice

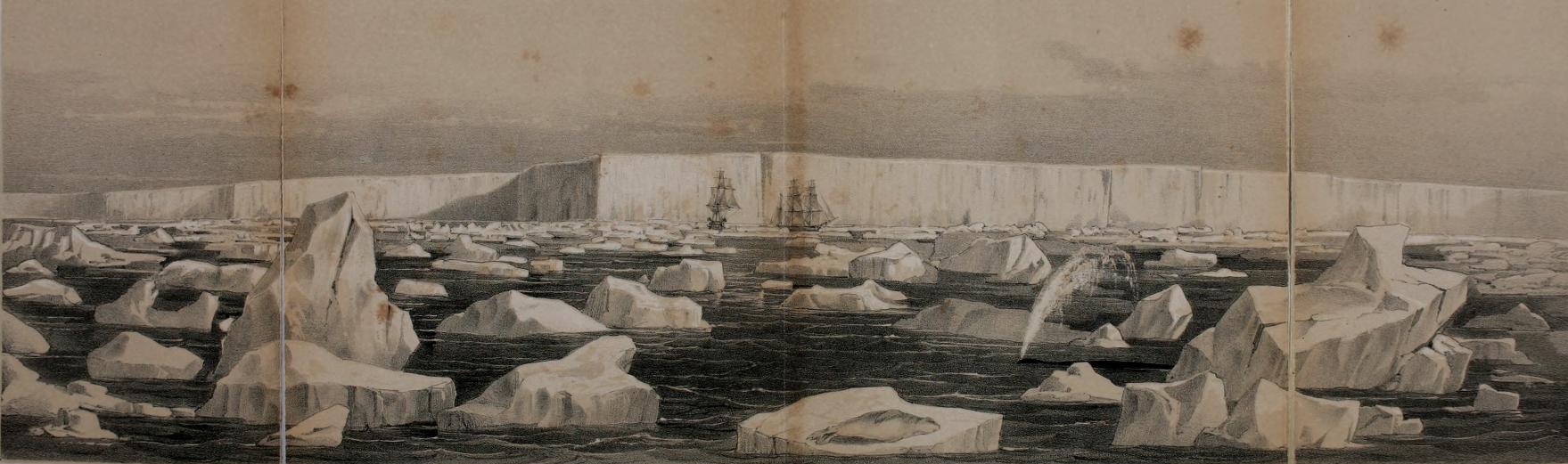

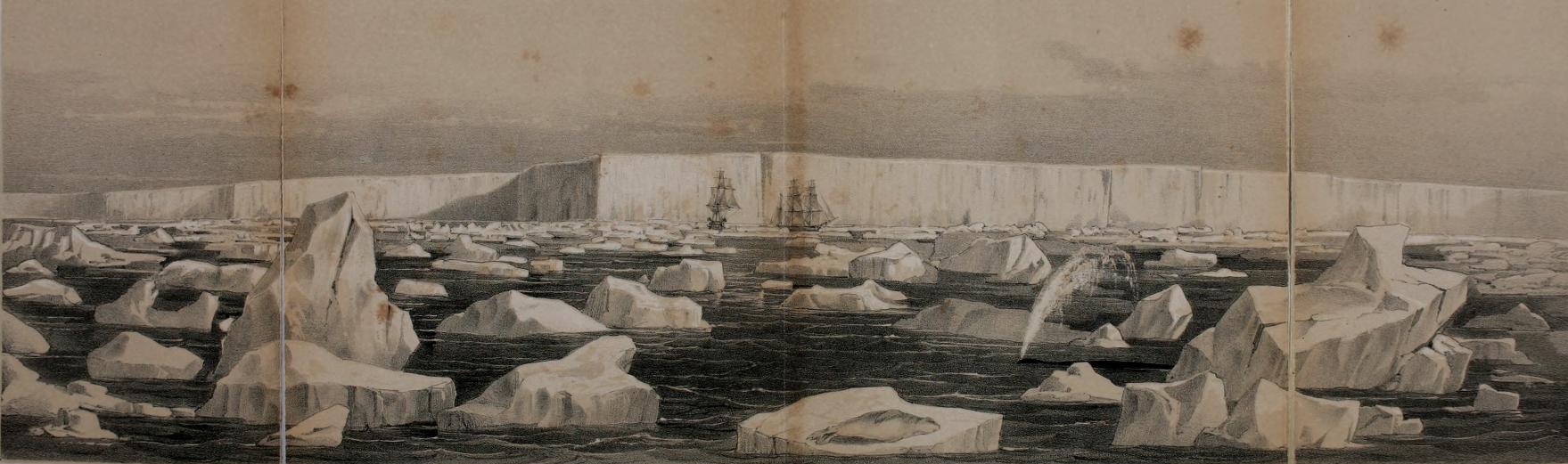

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "faste ...

at 66°55'S in January 1840 – they then forced their way into the pack ice, the first time this had been attempted. Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen began ...

wrote "Few people of the present day are capable of rightly appreciating this heroic deed, this brilliant proof of human courage and energy ... These men were heroes ...", and Scott

Scott may refer to:

Places Canada

* Scott, Quebec, municipality in the Nouvelle-Beauce regional municipality in Quebec

* Scott, Saskatchewan, a town in the Rural Municipality of Tramping Lake No. 380

* Rural Municipality of Scott No. 98, Sask ...

wrote "... all must concede that it deserves to rank among the most brilliant and famous ntarctic expeditionsthat have been made. ... few things could have looked more hopeless than an attack upon the great ice-bound region" They then emerged into open sea at 69°15'S and, sailing further south hoping to reach the South Magnetic Pole, they spotted land and mountains which they named Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70°30'S to 78°00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Antarctic Plateau. I ...

and the Admiralty Range, and cleared Cape Adare

Cape Adare is a prominent cape of black basalt forming the northern tip of the Adare Peninsula and the north-easternmost extremity of Victoria Land, East Antarctica.

Description

Marking the north end of Borchgrevink Coast and the west ...

. With Abernethy as coxswain

The coxswain ( , or ) is the person in charge of a boat, particularly its navigation and steering. The etymology of the word gives a literal meaning of "boat servant" since it comes from ''cock'', referring to the cockboat, a type of ship's boa ...

their first boat reached a coastal island, Possession Island, but they did not reach the Antarctic mainland. Onward, they crossed the latitude of Weddel's record of furthest south and landed on Franklin Island.

Soon, in the distance, they spotted what McCormick described as "a stupendous volcanic mountain in a high state of activity" and, getting closer, "a dense column of black smoke, intermingled with flashes of red flame". Hooker wrote of "a sight so surpassing everything that can be imagined". Ross named it Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus () is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica (after Mount Sidley), the highest active volcano in Antarctica, and the southernmost active volcano on Earth. It is the sixth-highest ultra mountain on the continent.

With a sum ...

, after his ship and the nearby mountain became Mount Terror.

Sailing east they reached a 200-foot ice cliff which they called the Great Southern Barrier, now the

Sailing east they reached a 200-foot ice cliff which they called the Great Southern Barrier, now the Ross Ice Shelf

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between h ...

, and followed it so reaching 78°4'S. By depth sounding adjacent to the ice they determined the ice was floating and was therefore 1000 feet thick. At a low point in the ice cliffs they could see from the masthead "an enormous plain of frosted silver" and they were certain there was no open sea further south. After following the barrier for over 250 miles and with the Antarctic winter approaching they returned to the west but, near Mount Erebus, could not get ashore. They were 160 miles from the south magnetic pole – 700 miles nearer than anyone had been before. After passing Cape Adare, they again succeeded in breaking through the pack ice and reached Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

on 6 April 1841 to be greeted by John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through t ...

and crowds of well-wishers. As it happens ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'' were the last vessels to navigate the Ross Sea using only sail.

Weddell Sea, 1841–1843

For more magnetic readings, they left for

For more magnetic readings, they left for Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

in July 1841 continuing to New Zealand's Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area on the east coast of the Far North District of the North Island of New Zealand. It is one of the most popular fishing, sailing and tourist destinations in the country, and has been renowned internationally for it ...

. In November they set sail south,

this time heading south along 146°W hoping to again reach the Ross Ice Shelf. This time they became trapped in the pack ice and it took 58 days to reach through 800 miles of pack to open water. They sighted what became Edward VII Land and, reaching their new furthest south of 78°9'S, they again saw the Ice Shelf. With the sea beginning to freeze solid, Ross headed north and set course for the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

. The two ships became pinched between two barrier icebergs and collided several times with both ships severely damaged and facing capsize. ''Terror'' managed to sail clear but ''Erebus'' was trapped with the only means of to escape being to "stern board" (sailing stern first) with Abernethy as ice-master. Abernethy "one of the most experienced icemen of our day – ever vigilant and on the watch" was able to guide them through a gap hardly wider than the ship. At last, after rounding Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

, they reached East Falkland

East Falkland ( es, Isla Soledad) is the largest island of the Falklands in the South Atlantic, having an area of or 54% of the total area of the Falklands. The island consists of two main land masses, of which the more southerly is known as La ...

in April 1842 and refitted the ships. For more magnetic readings they sailed for Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

, arriving in September but it was too early in the season to head south again so they took extended readings and then returned to the Falkland Islands, setting off on 17 December down 55°W aiming to reach the Antarctic coast at 40°W through the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

. This time they failed to penetrate any distance into the pack ice so they retreated, heading for the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

arriving in April 1843, and sailing home via St Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

, Ascension Island

Ascension Island is an isolated volcanic island, 7°56′ south of the Equator in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is about from the coast of Africa and from the coast of South America. It is governed as part of the British Overseas Territory of ...

and Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

. They arrived back in England on 23 September 1843, after which Abernethy has been briefly lost to history.

Searches for John Franklin's lost expedition party

With James Ross, 1848–1849

In 1845 Sir

In 1845 Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through t ...

commanded an expedition along with Francis Crozier

Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier (17 October 1796 – disappeared 26 April 1848) was an Irish officer of the Royal Navy and polar explorer who participated in six expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctic. In May 1845, he was second-in-comman ...

who had been on Ross's Antarctic expedition, again using ''Erebus'' and ''Terror'', and again trying to find a Northwest Passage. In what became known as Franklin's lost expedition

Franklin's lost expedition was a failed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain (Royal Navy), Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, and , and was assigned to traverse the last unnavigated sect ...

, both ships were eventually lost and 129 men were to die but Abernethy had not been included in the vast crew. By 1847 fears developed over what had happened so in 1848 three expeditions set off to search for Franklin, the main one commanded by James Ross in , with Robert McClure

Vice-Admiral Sir Robert John Le Mesurier McClure (28 January 1807 – 17 October 1873) was an Irish explorer of Scots descent who explored the Arctic. In 1854 he traversed the Northwest Passage by boat and sledge, and was the first to ci ...

, Francis McClintock

Sir Francis Leopold McClintock (8 July 1819 – 17 November 1907) was an Irish explorer in the British Royal Navy, known for his discoveries in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. He confirmed explorer John Rae's controversial report gather ...

and Abernethy as icemaster; and . The ships were accompanied by steam pinnaces

Pinnace may refer to:

* Pinnace (ship's boat), a small vessel used as a tender to larger vessels among other things

* Full-rigged pinnace

The full-rigged pinnace was the larger of two types of vessel called a pinnace in use from the sixteenth ...

. The ice was exceptionally bad in Lancaster Sound but they were able to winter at Port Leopold

The locality Port Leopold is an abandoned trading post in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It faces Prince Regent Inlet at the northeast tip of Somerset Island.

Elwin Bay is to the south, while Prince Leopold Island is to the north.

...

. Early next season they carefully checked in Peel Sound

Peel Sound is an Arctic waterway in the Qikiqtaaluk, Nunavut, Canada. It separates Somerset Island on the east from Prince of Wales Island on the west. To the north it opens onto Parry Channel while its southern end merges with Franklin Strai ...

by sledge, not realising this had actually been Franklin's route, and returned to ''Enterprise'' after 500 miles and 39 days. Ross presumed Franklin had got beyond Melville Island from where he would try and escape south to a region covered by one of the other search expeditions. Only by 28 August 1849 after they had sawed a two-mile canal could their ship be freed from the ice but to the west they found continuous ice. Although trapped, the ships drifted east for 250 miles at about 10 miles per day from where, starting on 24 September, they headed home.

With John Ross, 1850–1851

TheAdmiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

offered rewards for finding (or even hearing news of) Franklin so

the 73-year-old John Ross set off with ''Felix'', a steam schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

, with Abernethy as master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

of the vessel.

At this time he was describing Abernethy as "my old shipmate". Ross sought Abernethy's advice about crew which led to many of Abernethy's relatives being signed on.

''Felix'' left Ayr

Ayr (; sco, Ayr; gd, Inbhir Àir, "Mouth of the River Ayr") is a town situated on the southwest coast of Scotland. It is the administrative centre of the South Ayrshire council area and the historic county town of Ayrshire. With a population ...

on 20 May 1850 but at Loch Ryan in a near mutiny many of the crew had gone ashore and got drunk so Ross had to leave eight of them behind,

including Abernethy himself. A letter from Ross to the Hudson Bay Company

and a report in the ''Shipping Gazette'' were bitterly critical of Abernethy,

blaming him for instigating the whole thing. All the same, ''Felix'' set sail with Abernethy again on board.

Meeting other search ships off Cape York (the cape on the northwest coast of Greenland), it was found that translations of different local Inuit accounts variously said that nearby Franklin's party had not been seen at all or that everyone had been murdered. At the later official Admiralty Board of Enquiry Abernethy said he had never believed the murder story. Ross credited Abernethy and Charles Phillips with finding the graves of three of Franklin's men near the shore of

Meeting other search ships off Cape York (the cape on the northwest coast of Greenland), it was found that translations of different local Inuit accounts variously said that nearby Franklin's party had not been seen at all or that everyone had been murdered. At the later official Admiralty Board of Enquiry Abernethy said he had never believed the murder story. Ross credited Abernethy and Charles Phillips with finding the graves of three of Franklin's men near the shore of Beechey Island

Beechey Island ( iu, Iluvialuit, script=Latn) is an island located in the Arctic Archipelago of Nunavut, Canada, in Wellington Channel. It is separated from the southwest corner of Devon Island by Barrow Strait. Other features include Wellington ...

at the entrance to Wellington Channel

The Wellington Channel () (not to be confused with Wellington Strait) is a natural waterway through the central Canadian Arctic Archipelago in Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut. It runs north–south, separating Cornwallis Island and Devon Island. Quee ...

although Phillips later said he had been called to the scene. Ross wintered on Cornwallis Island and next year searched the island and Wellington Channel. Again Ross found Abernethy drunk and his spirit allowance was stopped – later in an open letter to the ''Nautical Standard and Steam Navigation Gazette'' Ross said he had lost all confidence in Abernethy due to his insubordination and intemperance. In August 1851 when the ice melted they returned home with Ross saying "we parted good friends at last".

With Edward Inglefield, 1852

In 1852, succumbing to public pressure, the Admiralty dispatched five search vessels on a new expedition and Lady Franklin funded a sixth vessel, her own steam yacht ''

In 1852, succumbing to public pressure, the Admiralty dispatched five search vessels on a new expedition and Lady Franklin funded a sixth vessel, her own steam yacht ''Isabel

Isabel is a female name of Spanish origin. Isabelle is a name that is similar, but it is of French origin. It originates as the medieval Spanish form of '' Elisabeth'' (ultimately Hebrew ''Elisheva''), Arising in the 12th century, it became popul ...

'', a two-masted brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Ol ...

, under Edward Inglefield. Abernethy was ice master and second in command of ''Isabel''. Contrary to instructions Inglefield explored around Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arc ...

and reached Wolstenholme Bay, near Cape York, where Franklin and his men had supposedly been murdered. However, they found nothing suspicious buried in the cairn that had been said to be their burial place.

Sailing on north they reached Smith Sound

Smith Sound ( da, Smith Sund; french: Détroit de Smith) is an uninhabited Arctic sea passage between Greenland and Canada's northernmost island, Ellesmere Island. It links Baffin Bay with Kane Basin and forms part of the Nares Strait.

On the ...

and discovered it provided a hitherto unknown entrance to the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

. On 29 August, with a heavy swell, thick fog, and ice forming, on Abernethy's advice that they only had four or five days before they would be trapped, they turned to the south and reached Beechey Island

Beechey Island ( iu, Iluvialuit, script=Latn) is an island located in the Arctic Archipelago of Nunavut, Canada, in Wellington Channel. It is separated from the southwest corner of Devon Island by Barrow Strait. Other features include Wellington ...

to leave surplus stores for the ships there. They left earlier on the same day that McCormick arrived – in his book McCormick wrote of his disappointment about having missed his "old shipmate and friend at both the Poles, Abernethy." After surviving severe storms they abandoned the thought of overwintering and in ferocious weather returned home in November 1852.

Death, assessments and legacy

For most of Abernethy's married life he had been away at sea. In 1854 his wife Barbara died, aged 44, with her husband at her side, and Abernethy returned to live in Peterhead. In 1857 he married Rebecca Young but he was only to live for another three years. He died of "ulcersation of the stomach" on 13 April 1860 and his wife erected a gravestone in Peterhead Old Kirkyard. The local newspaper carried a very brief death notice.

According to Alex Buchan, Abernethy's biographer, in the 19th century Royal Naval officers were almost always from the landed gentry and they had purchased their commissions. Certain of their superiority, they wrote accounts of their expeditions keeping the credit for themselves. Indeed, at the end of an expedition, commanders often required any records kept by the crew to be given to them for inclusion at their discretion in the official report. Possibly because of this Abernethy left no written records. According to Sir Joseph Hooker, a distinguished scientist, concerning crewmen, "And where have you seen or heard that their services are in the least appreciated? The Admiralty have not as much as sent a letter of thanks to the men".

Although Abernethy has largely disappeared from history his contributions were sufficiently outstanding for accounts to have been left of him, even though he was neither an officer nor a gentleman. Sir Clements Markham, who had been president of the

For most of Abernethy's married life he had been away at sea. In 1854 his wife Barbara died, aged 44, with her husband at her side, and Abernethy returned to live in Peterhead. In 1857 he married Rebecca Young but he was only to live for another three years. He died of "ulcersation of the stomach" on 13 April 1860 and his wife erected a gravestone in Peterhead Old Kirkyard. The local newspaper carried a very brief death notice.

According to Alex Buchan, Abernethy's biographer, in the 19th century Royal Naval officers were almost always from the landed gentry and they had purchased their commissions. Certain of their superiority, they wrote accounts of their expeditions keeping the credit for themselves. Indeed, at the end of an expedition, commanders often required any records kept by the crew to be given to them for inclusion at their discretion in the official report. Possibly because of this Abernethy left no written records. According to Sir Joseph Hooker, a distinguished scientist, concerning crewmen, "And where have you seen or heard that their services are in the least appreciated? The Admiralty have not as much as sent a letter of thanks to the men".

Although Abernethy has largely disappeared from history his contributions were sufficiently outstanding for accounts to have been left of him, even though he was neither an officer nor a gentleman. Sir Clements Markham, who had been president of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

and who had known Abernethy well, wrote in 1921 "The gunner of the ''Erebus'' must not be left out, as he was a very exceptional character and had very wide Arctic experience ... Abernethy was a splendid seaman". In 1828 Sir John Ross had described him as "the most steady and active, as well as the most powerful man in the ship".

Three capes were named after Abernethy: in Wolstenholme Fjord

Wolstenholme Fjord ( kl, Uummannap Kangerlua) is a fjord in Avannaata municipality, Northwest Greenland. It is located to the north of the Thule Air Base and adjacent to the abandoned Inuit settlement of Narsaarsuk.

The area was contaminated in ...

in Baffin Bay

Baffin Bay (Inuktitut: ''Saknirutiak Imanga''; kl, Avannaata Imaa; french: Baie de Baffin), located between Baffin Island and the west coast of Greenland, is defined by the International Hydrographic Organization as a marginal sea of the Arc ...

, on King William Island

King William Island (french: Île du Roi-Guillaume; previously: King William Land; iu, Qikiqtaq, script=Latn) is an island in the Kitikmeot Region of Nunavut, which is part of the Arctic Archipelago. In area it is between and making it the 6 ...

, and on an island west of Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island ( iu, script=Latn, Umingmak Nuna, lit=land of muskoxen; french: île d'Ellesmere) is Canada's northernmost and third largest island, and the tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Br ...

. In 1983 Abernethy Flats

Abernethy Flats is a gravel plain cut by braided streams at the head of Brandy Bay

James Ross Island is a large island off the southeast side and near the northeastern extremity of the Antarctic Peninsula, from which it is separated by Prince ...

on James Ross Island

James Ross Island is a large island off the southeast side and near the northeastern extremity of the Antarctic Peninsula, from which it is separated by Prince Gustav Channel. Rising to , it is irregularly shaped and extends in a north–south ...

was also given his name. His gravestone still stands and in 2016 his biography was published.

Notes

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Abernethy, Thomas 1803 births 1860 deaths Explorers of the Arctic 19th-century explorers Scottish polar explorers 19th-century Scottish people People from Peterhead Explorers of Antarctica 19th-century Royal Navy personnel Royal Navy sailors Recipients of the Polar Medal