Theories of the Black Death on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Theories of the Black Death are a variety of explanations that have been advanced to explain the nature and transmission of the Black Death (1347–51). A number of epidemiologists from the 1980s to the 2000s challenged the traditional view that the Black Death was caused by

Several possible causes have been advanced for the Black Death; the most prevalent is the bubonic plague theory. Efficient transmission of ''Yersinia pestis'' is generally thought to occur only through the bites of fleas whose mid guts become obstructed by replicating ''Y. pestis'' several days after feeding on an infected host. This blockage results in starvation and aggressive feeding behaviour by fleas that repeatedly attempt to clear their blockage by regurgitation, resulting in thousands of plague bacteria being flushed into the feeding site, infecting the host. However, modelling of

Several possible causes have been advanced for the Black Death; the most prevalent is the bubonic plague theory. Efficient transmission of ''Yersinia pestis'' is generally thought to occur only through the bites of fleas whose mid guts become obstructed by replicating ''Y. pestis'' several days after feeding on an infected host. This blockage results in starvation and aggressive feeding behaviour by fleas that repeatedly attempt to clear their blockage by regurgitation, resulting in thousands of plague bacteria being flushed into the feeding site, infecting the host. However, modelling of

plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

based on the type and spread of the disease. The confirmation in 2010 and 2011 that ''Yersinia pestis

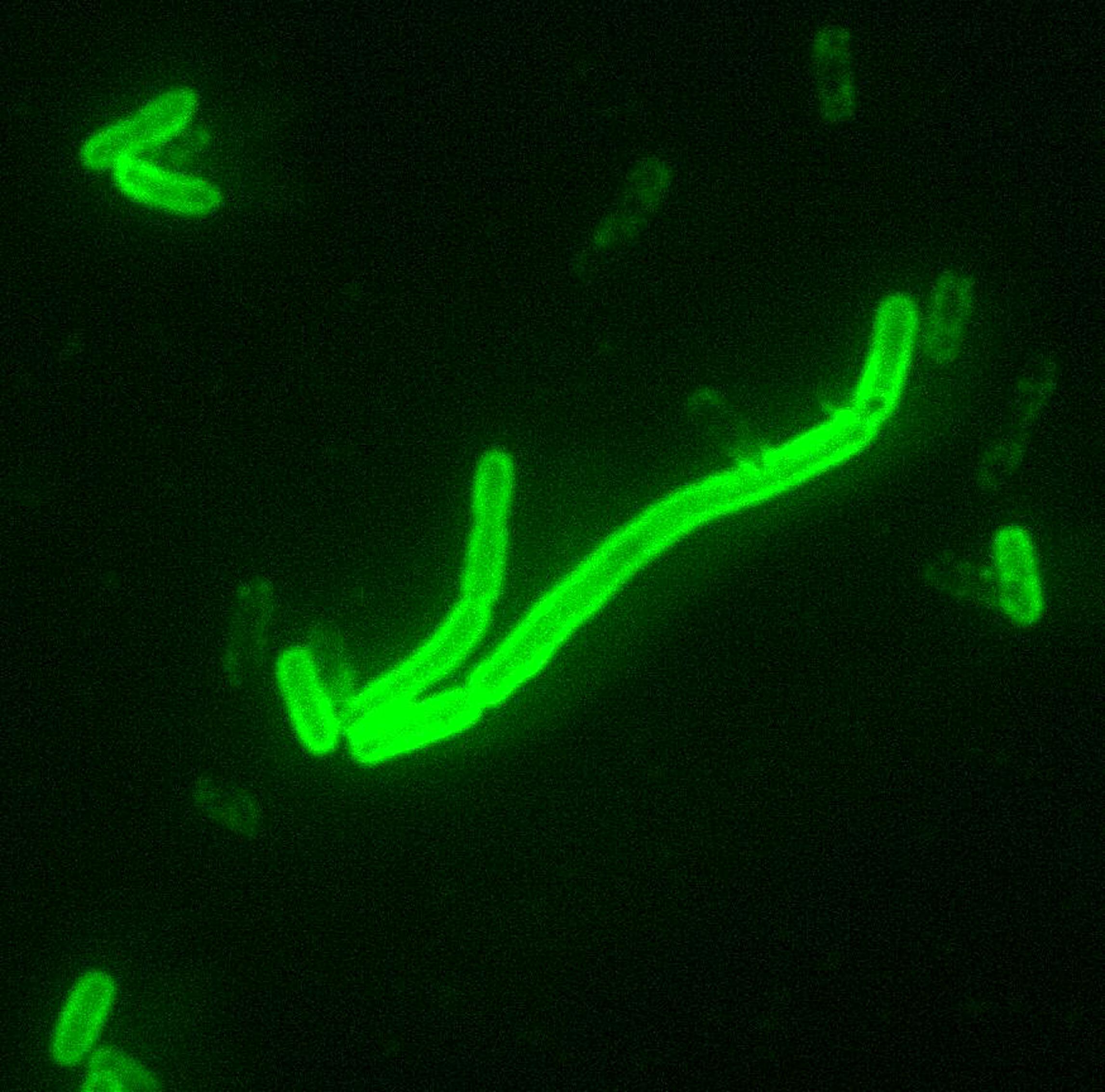

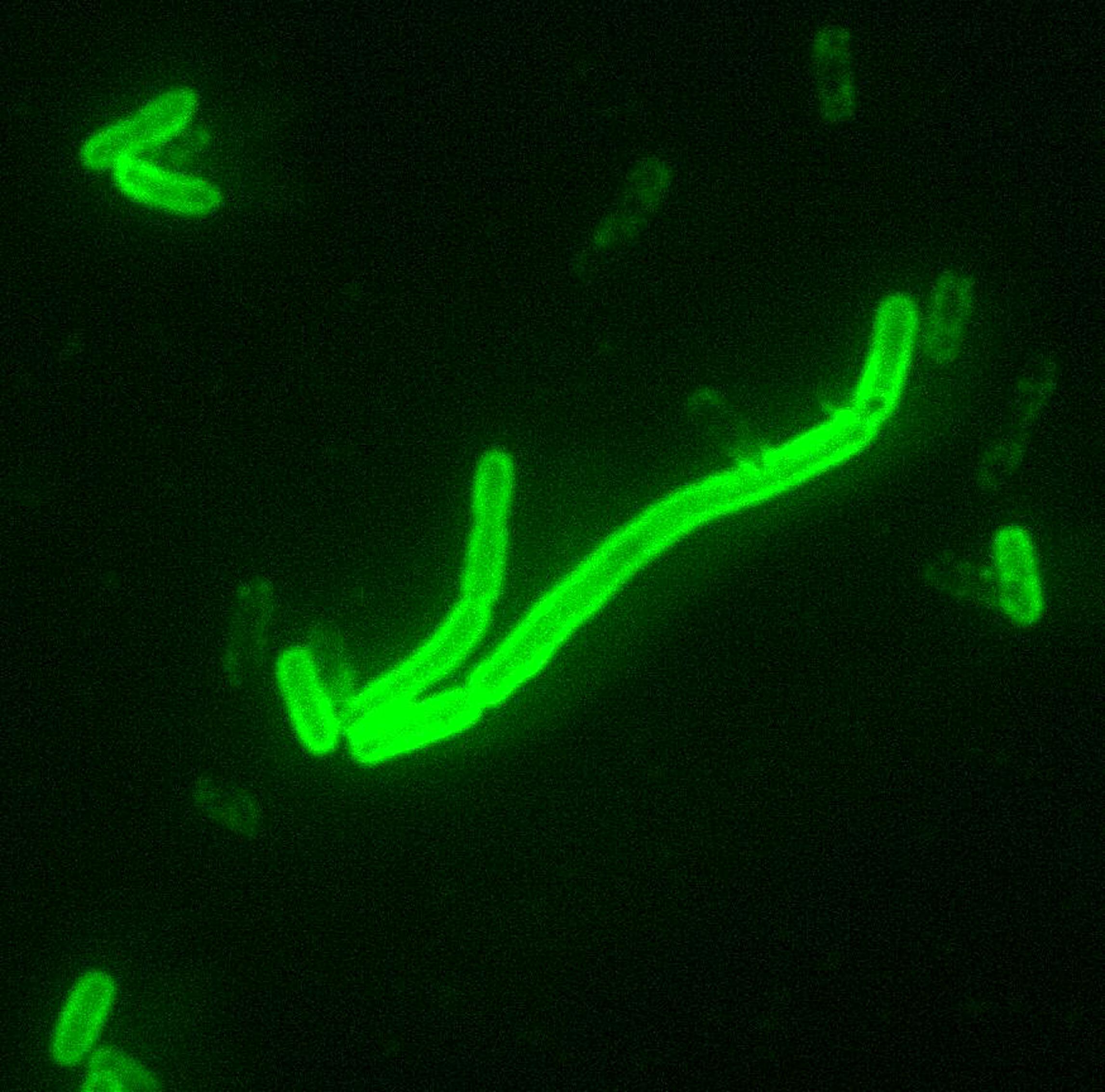

''Yersinia pestis'' (''Y. pestis''; formerly '' Pasteurella pestis'') is a gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacillus bacterium without spores that is related to both ''Yersinia pseudotuberculosis'' and ''Yersinia enterocolitica''. It is a facult ...

'' DNA was associated with a large number of plague sites has led researchers to conclude that "Finally, plague is plague."

Plague

Several possible causes have been advanced for the Black Death; the most prevalent is the bubonic plague theory. Efficient transmission of ''Yersinia pestis'' is generally thought to occur only through the bites of fleas whose mid guts become obstructed by replicating ''Y. pestis'' several days after feeding on an infected host. This blockage results in starvation and aggressive feeding behaviour by fleas that repeatedly attempt to clear their blockage by regurgitation, resulting in thousands of plague bacteria being flushed into the feeding site, infecting the host. However, modelling of

Several possible causes have been advanced for the Black Death; the most prevalent is the bubonic plague theory. Efficient transmission of ''Yersinia pestis'' is generally thought to occur only through the bites of fleas whose mid guts become obstructed by replicating ''Y. pestis'' several days after feeding on an infected host. This blockage results in starvation and aggressive feeding behaviour by fleas that repeatedly attempt to clear their blockage by regurgitation, resulting in thousands of plague bacteria being flushed into the feeding site, infecting the host. However, modelling of epizootic

In epizoology, an epizootic (from Greek: ''epi-'' upon + ''zoon'' animal) is a disease event in a nonhuman animal population analogous to an epidemic in humans. An epizootic may be restricted to a specific locale (an "outbreak"), general (an "epi ...

plague observed in prairie dogs, suggests that occasional reservoirs of infection such as an infectious carcass, rather than "blocked fleas" are a better explanation for the observed epizootic behaviour of the disease in nature.

One hypothesis about the epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

It is a cornerstone of public health, and shapes policy decisions and evide ...

—the appearance, spread, and especially disappearance—of plague from Europe is that the flea-bearing rodent reservoir of disease was eventually succeeded by another species. The black rat (''Rattus rattus'') was originally introduced from Asia to Europe by trade, but was subsequently displaced and succeeded throughout Europe by the bigger brown rat

The brown rat (''Rattus norvegicus''), also known as the common rat, street rat, sewer rat, wharf rat, Hanover rat, Norway rat, Norwegian rat and Parisian rat, is a widespread species of common rat. One of the largest muroids, it is a brown o ...

(''Rattus norvegicus''). The brown rat was not as prone to transmit the germ-bearing fleas to humans in large die-offs due to a different rat ecology. The dynamic complexities of rat ecology, herd immunity

Herd immunity (also called herd effect, community immunity, population immunity, or mass immunity) is a form of indirect protection that applies only to contagious diseases. It occurs when a sufficient percentage of a population has become im ...

in that reservoir, interaction with human ecology, secondary transmission routes between humans with or without fleas, human herd immunity, and changes in each might explain the eruption, dissemination, and re-eruptions of plague that continued for centuries until its unexplained disappearance.

Signs and symptoms of the three forms of plague

Theplague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pe ...

comes in three forms and it brought an array of signs and symptoms to those infected. The classic sign of bubonic plague was the appearance of bubo

A bubo (Greek βουβών, ''boubṓn'', 'groin') is adenitis or inflammation of the lymph nodes and is an example of reactive lymphadenopathy.

Classification

Buboes are a symptom of bubonic plague and occur as painful swellings in the thigh ...

es in the groin, the neck, and armpits, which oozed pus and bled. Most victims died within four to seven days after infection. The septicaemic plague is a form of "blood poisoning", and pneumonic plague

Pneumonic plague is a severe lung infection caused by the bacterium ''Yersinia pestis''. Symptoms include fever, headache, shortness of breath, chest pain, and coughing. They typically start about three to seven days after exposure. It is one ...

is an airborne plague that attacks the lungs before the rest of the body.

The bubonic plague was the most commonly seen form during the Black Death. The bubonic form of the plague has a mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

of thirty to seventy-five percent and symptoms include fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a temperature above the normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature set point. There is not a single agreed-upon upper limit for normal temperature with sources using val ...

of 38–41 ° C (101–105 °F), headaches, painful aching joints, nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. While not painful, it can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the ...

and vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis and throwing up) is the involuntary, forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteri ...

, and a general feeling of malaise. The second most common form is the pneumonic plague and has symptoms that include fever, cough, and blood-tinged sputum. As the disease progressed, sputum became free flowing and bright red and death occurred within 2 days. The pneumonic form of the plague has a high mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

at ninety to ninety-five percent. Septicemic plague is the least common of the three forms, with a mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of d ...

close to one hundred percent. Symptoms include high fevers and purple skin patches (purpura

Purpura () is a condition of red or purple discolored spots on the skin that do not blanch on applying pressure. The spots are caused by bleeding underneath the skin secondary to platelet disorders, vascular disorders, coagulation disorders, ...

due to DIC). Both pneumonic and septicemic plague can be caused by flea bites when the lymph

Lymph (from Latin, , meaning "water") is the fluid that flows through the lymphatic system, a system composed of lymph vessels (channels) and intervening lymph nodes whose function, like the venous system, is to return fluid from the tissues ...

nodes are overwhelmed. In this case they are referred to as ''secondary'' forms of the disease.

David Herlihy identifies from the records another potential sign of the plague: freckle-like spots and rashes. Sources from Viterbo, Italy refer to "the signs which are vulgarly called ''lenticulae''", a word which bears resemblance to the Italian word for freckles, ''lentiggini''. These are not the swellings of buboes, but rather "darkish points or pustules which covered large areas of the body".

The uncharacteristically rapid spread of the plague could be due to respiratory droplet

A respiratory droplet is a small aqueous droplet produced by exhalation, consisting of saliva or mucus and other matter derived from respiratory tract surfaces. Respiratory droplets are produced naturally as a result of breathing, speaking, snee ...

transmission, and low levels of immunity in the European population at that period. Historical examples of pandemics of other diseases in populations without previous exposure, such as smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

transmitted by aerosol amongst Native Americans, show that the first instance of an epidemic spreads faster and is far more virulent than later instances among the descendants of survivors, for whom natural selection has produced characteristics that are protective against the disease.

Vectors of ''Y. pestis''

Historians who believe that the Black Death was indeed caused by bubonic plague have put forth several theories questioning the traditional identification of ''Rattus'' sp. and their associated fleas as plague's primaryvector

Vector most often refers to:

*Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

*Vector (epidemiology), an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematic ...

.

A 2012 report from the University of Bergen

The University of Bergen ( no, Universitetet i Bergen, ) is a research-intensive state university located in Bergen, Norway. As of 2019, the university has over 4,000 employees and 18,000 students. It was established by an act of parliament in 194 ...

acknowledges that ''Y. pestis'' could have been the cause of the pandemic, but states that the epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population.

It is a cornerstone of public health, and shapes policy decisions and evide ...

of the disease is different, most importantly the rapid spread and the lack of rats in Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

and other parts of Northern Europe. ''R. rattus'' was present in Scandinavian cities and ports at the time of the Black Death but was not found in small, inland villages. Based on archaeological evidence from digs all over Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

, the black rat population was present in sea ports but remained static in the cold climate and would only have been sustained if ships continually brought black rats and that the rats would be unlikely to venture across open ground to remote villages. It argues that while healthy black rats are rarely seen, rats suffering from bubonic plague behave differently from healthy rats; where accounts from warmer climates mention rats falling from roofs and walls and piling high in the streets, Samuel Pepys, who described trifling observations and events of the London plague of 1665 in great detail, makes no mention of sick or dead rats, nor does Absalon Pederssøn in his diary, which contains detailed descriptions of a plague epidemic in Bergen in 1565. Ultimately, Hufthammer and Walløe offer the possibility of human flea

The human flea (''Pulex irritans'') – once also called the house flea – is a cosmopolitan flea species that has, in spite of the common name, a wide host spectrum. It is one of six species in the genus '' Pulex''; the other five are all confi ...

s and lice in place of rats.

University of Oslo

The University of Oslo ( no, Universitetet i Oslo; la, Universitas Osloensis) is a public research university located in Oslo, Norway. It is the highest ranked and oldest university in Norway. It is consistently ranked among the top universit ...

researchers concluded that ''Y. pestis'' was likely carried over the Silk Road via fleas on giant gerbils from Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

during intermittent warm spells.

Michael McCormick, a historian supporting bubonic plague as the Black Death, explains how archaeological research has confirmed that the black or "ship" rat (''Rattus rattus)'' was already present in Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

and medieval Europe

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. Also, the DNA of ''Y. pestis'' has been identified in the teeth of the human victims, the same DNA which has been widely believed to have come from the infected rodents. Pneumonic expression of ''Y. pestis'' can be transmitted by human-to-human contact, but McCormick states that this does not spread as easily as previous historians have imagined. According to him, the rat is the only plausible agent of transmission that could have led to such a wide and quick spread of the plague. This is because of rats' proclivity to associate with humans and the ability of their blood to withstand very large concentrations of the bacillus

''Bacillus'' (Latin "stick") is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum '' Bacillota'', with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of other so-shaped bacteria; and the plural ''Bacill ...

. When rats died, their fleas (which were infected with bacterial blood) found new hosts in the form of humans and animals. The Black Death tapered off in the eighteenth century, and according to McCormick, a rat-based theory of transmission could explain why this occurred. The plague(s) had killed a large portion of the human host population of Europe and dwindling cities meant that more people were isolated, and so geography and demography did not allow rats to have as much contact with Europeans. Greatly curtailed communication and transportation systems due to the drastic decline in human population also hindered the replenishment of devastated rat colonies.

Alternative explanations

Although ''Y. pestis'' as the causative agent of plague was still widely accepted during this period, scientific and historical investigations in the late 20th century through publication of conclusive evidence in 2011 led some researchers to doubt the long-held belief that the Black Death was an epidemic of bubonic plague.Evidence against ''Y. pestis''

The arguments for an alternate causative agent were based on differences in mortality levels, disease diffusion rates, rat distribution, flea reproduction and climate, and distribution of human population. In 1984, Graham Twigg published ''The Black Death: A Biological Reappraisal'', where he argued that the climate and ecology of Europe and particularly England made it nearly impossible for rats and fleas to have transmitted bubonic plague. Combining information on the biology of ''Rattus rattus

The black rat (''Rattus rattus''), also known as the roof rat, ship rat, or house rat, is a common long-tailed rodent of the stereotypical rat genus ''Rattus'', in the subfamily Murinae. It likely originated in the Indian subcontinent, but is ...

'', ''Rattus norvegicus

''Rattus'' is a genus of muroid rodents, all typically called rats. However, the term rat can also be applied to rodent species outside of this genus.

Species and description

The best-known ''Rattus'' species are the black rat (''R. rattus'') ...

'', and the common fleas ''Xenopsylla cheopis

The Oriental rat flea (''Xenopsylla cheopis''), also known as the tropical rat flea or the rat flea, is a parasite of rodents, primarily of the genus ''Rattus'', and is a primary vector for bubonic plague and murine typhus. This occurs when a fl ...

'' and ''Pulex irritans

The human flea (''Pulex irritans'') – once also called the house flea – is a cosmopolitan flea species that has, in spite of the common name, a wide host spectrum. It is one of six species in the genus '' Pulex''; the other five are all confi ...

'' with modern studies of plague epidemiology, particularly in India, where the ''R. rattus'' is a native species and conditions are nearly ideal for plague to be spread, Twigg concluded that it would have been nearly impossible for ''Yersinia pestis'' to have been the causative agent of the plague, let alone its explosive spread across Europe. Twigg also showed that the common alternate theory of entirely pneumonic spread does not hold up. He proposed, based on a reexamination of the evidence and symptoms, that the Black Death may actually have been an epidemic of pulmonary anthrax caused by '' Bacillus anthracis''.

In 2002, Samuel K. Cohn published the controversial article, “The Black Death: End of the Paradigm”.

Cohn argued that the medieval and modern plagues were two distinct diseases differing in their symptoms, signs, and epidemiologies. Cohn's argument that medieval plague was not rat-based is supported by his claims that the modern and medieval plagues occurred in different seasons (a claim supported in a 2009 article by Mark Welford and Brian Bossak), had unparalleled cycles of recurrence, and varied in the manner in which immunity was acquired. The modern plague reaches its peak in seasons with high humidity and a temperature of between and , as rats' fleas thrive in this climate. In comparison, the Black Death is recorded as occurring in periods during which rats' fleas could not have survived, i.e. hot Mediterranean summers above . In terms of recurrence, the Black Death on average did not resurface in an area for between five and fifteen years after it had occurred. In contrast, modern plagues often recur in a given area yearly for an average of eight to forty years. Last, Cohn presented evidence displaying that individuals gained immunity to the Black Death, unlike the modern plague, during the fourteenth century. He stated that in 1348, two-thirds of those suffering from plague died, in comparison to one-twentieth by 1382. Statistics display that immunity to the modern plague has not been acquired in modern times.

In the Encyclopedia of Population, Cohn pointed to five major weaknesses in the bubonic plague theory:

* very different transmission speeds – the Black Death was reported to have spread 385 km in 91 days (4.23 km/day) in 664, compared to 12–15 km a year for the modern bubonic plague, with the assistance of trains and cars

* difficulties with the attempt to explain the rapid spread of the Black Death by arguing that it was spread by the rare pneumonic form of the disease – in fact this form killed less than 0.3% of the infected population in its worst outbreak (Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

in 1911)

* different seasonality – the modern plague can only be sustained at temperatures between 10 and 26 °C and requires high humidity, while the Black Death occurred even in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

in the middle of the winter and in the Mediterranean in the middle of hot dry summers

* very different death rates – in several places (including Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

in 1348) over 75% of the population appears to have died; in contrast the highest mortality for the modern bubonic plague was 3% in Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second-m ...

in 1903

* the cycles and trends of infection were very different between the diseases – humans did not develop resistance to the modern disease, but resistance to the Black Death rose sharply, so that eventually it became mainly a childhood disease

Cohn also pointed out that while the identification of the disease as having buboes relies on accounts of Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was some ...

and others, they described buboes, abscesses, rash

A rash is a change of the human skin which affects its color, appearance, or texture.

A rash may be localized in one part of the body, or affect all the skin. Rashes may cause the skin to change color, itch, become warm, bumpy, chapped, dry, c ...

es and carbuncle

A carbuncle is a cluster of boils caused by bacterial infection, most commonly with ''Staphylococcus aureus'' or ''Streptococcus pyogenes''. The presence of a carbuncle is a sign that the immune system is active and fighting the infection. The ...

s occurring all over the body, the neck or behind the ears. In contrast, the modern disease rarely has more than one bubo, most commonly in the groin, and is not characterised by abscesses, rashes and carbuncles. This difference, he argued, ties in with the fact that fleas caused the modern plague and not the Black Death. Since flea bites do not usually reach beyond a person's ankles, in the modern period the groin was the nearest lymph node that could be infected. As the neck and the armpit were often infected during the medieval plague, it appears less likely that these infections were caused by fleas on rats.

Ebola-like virus

In 2001, Susan Scott and Christopher Duncan, respectively a demographer and zoologist fromLiverpool University

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

, proposed the theory that the Black Death might have been caused by an Ebola-like virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsk ...

, not a bacterium. Their rationale was that this plague spread much faster and the incubation period was much longer than other confirmed ''Y. pestis''–caused plagues. A longer period of incubation will allow carriers of the infection to travel farther and infect more people than a shorter one. When the primary vector

Vector most often refers to:

*Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

*Vector (epidemiology), an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematic ...

is humans, as opposed to birds, this is of great importance. Epidemiological studies suggest the disease was transferred between humans (which happens rarely with ''Yersinia pestis'' and very rarely for ''Bacillus anthracis''), and some gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s that determine immunity to Ebola-like viruses are much more widespread in Europe than in other parts of the world. Their research and findings are thoroughly documented in ''Biology of Plagues''. More recently the researchers have published computer modeling

demonstrating how the Black Death has made around 10% of Europeans resistant to HIV.

Anthrax

In a similar vein, historianNorman Cantor

Norman Frank Cantor (November 19, 1929 – September 18, 2004) was a Canadian-American historian who specialized in the medieval period. Known for his accessible writing and engaging narrative style, Cantor's books were among the most widely rea ...

, in ''In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It Made'' (2001), suggested the Black Death might have been a combination of pandemics including a form of anthrax, a cattle murrain

Murrain (also known as distemper) is an antiquated term for various infectious diseases affecting cattle and sheep. The word originates from Middle English ''moreine'' or ''moryne'', as a derivative of Latin ''mori'' "to die".

The word ''murra ...

. He cited reported disease symptoms not in keeping with the known effects of either bubonic or pneumonic plague, the discovery of anthrax spores in a plague pit

A plague pit is the informal term used to refer to mass graves in which victims of the Black Death were buried. The term is most often used to describe pits located in Great Britain, but can be applied to any place where bubonic plague victims were ...

in Scotland, and the fact that meat from infected cattle was known to have been sold in many rural English areas prior to the onset of the plague. The means of infection varied widely, with infection in the absence of living or recently dead humans in Sicily (which speaks against most viruses). Also, diseases with similar symptoms were generally not distinguished between in that period (see ''murrain'' above), at least not in the Christian world; Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

and Muslim medical records can be expected to yield better information which however only pertains to the specific disease(s) which affected these areas.

Cutaneous anthrax infection in humans shows up as a boil-like skin lesion that eventually forms an ulcer with a black center (eschar

An eschar (; Greek: ''ἐσχάρᾱ'', ''eskhara''; Latin: ''eschara'') is a slough or piece of dead tissue that is cast off from the surface of the skin, particularly after a burn injury, but also seen in gangrene, ulcer, fungal infections, ...

), often beginning as an irritating and itchy skin lesion or blister that is dark and usually concentrated as a black dot. Cutaneous infections generally form within the site of spore penetration between two and five days after exposure. Without treatment about 20% of cutaneous skin infection cases progress to toxemia and death. Respiratory infection in humans initially presents with cold or flu-like symptoms

Influenza-like illness (ILI), also known as flu-like syndrome or flu-like symptoms, is a medical diagnosis of possible influenza or other illness causing a set of common symptoms. These include fever, shivering, chills, malaise, dry cough, loss ...

for several days, followed by severe (and often fatal) respiratory collapse. Historical mortality was 92%.Bravata DM, Holty JE, Liu H, McDonald KM, Olshen RA, Owens DK (2006), Systematic review: a century of inhalational anthrax cases from 1900 to 2005, ''Annals of Internal Medicine

''Annals of Internal Medicine'' is an academic medical journal published by the American College of Physicians (ACP). It is one of the most widely cited and influential specialty medical journals in the world. ''Annals'' publishes content relevan ...

''; 144(4): 270–280. Gastrointestinal infection in humans is most often caused by eating anthrax-infected meat and is characterized by serious gastrointestinal difficulty, vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis and throwing up) is the involuntary, forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteri ...

of blood, severe diarrhea, acute inflammation of the intestinal tract, and loss of appetite. After the bacteria invades the bowel system, it spreads through the bloodstream throughout the body, making more toxins on the way.

Molecular evidence for ''Y. pestis''

However recently the more and more evidences appear that the causative agent of the Black Death was ''Y. pestis''. In 2000, Didier Raoult and others reported finding ''Y. pestis'' DNA by performing a "suicide PCR" on tooth pulp tissue from a fourteenth-century plague cemetery in Montpellier. Drancourt and Raoult reported similar findings in a 2007 study. However, other researchers argued the study was flawed and cited contrary evidence. In 2003, Susan Scott of theUniversity of Liverpool

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

argued that there was no conclusive reason to believe the Montpellier teeth were from Black Death victims.

Also in 2003, a team led by Alan Cooper from Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

tested 121 teeth from sixty-six skeletons found in 14th century mass graves, including well-documented Black Death plague pits in East Smithfield

East Smithfield is a small locality in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, east London, and also a short street, a part of the A1203 road.

Once broader in scope, the name came to apply to the part of the ancient parish of St Botolph without ...

and Spitalfields. Their results showed no genetic evidence for ''Y. pestis'', and Cooper concluded that though in 2003 " cannot rule out ''Yersinia'' as the cause of the Black Death ... right now there is no molecular evidence for it." Other researchers argued that those burial sites where ''Y. pestis'' could not be found had nothing to do with the Black Death in the first place.

In October 2010 the journal ''PLoS Pathogens

''PLOS Pathogens'' is a peer-reviewed open-access medical journal. All content in ''PLOS Pathogens'' is published under the Creative Commons "by-attribution" license.

''PLOS Pathogens'' began operation in September 2005. It was the fifth journa ...

'' published a paper by Haensch et al. (2010), a multinational team that investigated the role of ''Yersinia pestis'' in the Black Death. The paper detailed the results of new surveys that combined ancient DNA analyses and protein-specific detection which were used to find DNA and protein signatures specific for ''Y. pestis'' in human skeletons from widely distributed mass graves in northern, central and southern Europe that were associated archaeologically with the Black Death and subsequent resurgences. The authors concluded that this research, together with prior analyses from the south of France and Germany

:"...ends the debate about the etiology of the Black Death, and unambiguously demonstrates that ''Y. pestis'' was the causative agent of the epidemic plague that devastated Europe during the Middle Ages."

Significantly, the study also identified two previously unknown but related clades (genetic branches) of the ''Y. pestis'' genome that were associated with distinct medieval mass graves. These were found to be ancestral to modern isolates of the modern ''Y. pestis'' strains Orientalis and Medievalis, suggesting that these variant strains (which are now presumed to be extinct) may have entered Europe in two distinct waves.

The presence of ''Y. pestis'' during the Black Death and its phylogenetic placement was definitely established in 2011 with the publication of a ''Y. pestis'' genome using new amplification techniques used on DNA extracts from teeth from over 100 samples from the East Smithfield

East Smithfield is a small locality in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, east London, and also a short street, a part of the A1203 road.

Once broader in scope, the name came to apply to the part of the ancient parish of St Botolph without ...

burial site in London.

Surveys of plague pit remains in France and England indicate that the first variant entered western Europe through the port of Marseilles around November 1347 and spread through France over the next two years, eventually reaching England in the spring of 1349, where it spread through the country in three successive epidemics. However, surveys of plague pit remains from the Netherlands town of Bergen op Zoom

Bergen op Zoom (; called ''Berrege'' in the local dialect) is a municipality and a city located in the south of the Netherlands.

Etymology

The city was built on a place where two types of soil meet: sandy soil and marine clay. The sandy soil ...

showed that the ''Y. pestis'' genotype responsible for the pandemic that spread through the Low Countries from 1350 differed from that found in Britain and France, implying that Bergen op Zoom (and possibly other parts of the southern Netherlands) was not directly infected from England or France in AD 1349, suggesting that a second wave of plague infection, distinct from those in Britain and France, may have been carried to the Low Countries from Norway, the Hanseatic

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=German language, Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Norther ...

cities, or another site.

References

{{Black Death Black Death