The David Frost Show on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''ITV News''. 1 September 2013. A

David Frost

David Frost

on TV Cream

TV Cream on Paradine Productions

{{DEFAULTSORT:Frost, David 1939 births 2013 deaths Al Jazeera people Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge BAFTA fellows BBC newsreaders and journalists British broadcast news analysts British reporters and correspondents British television producers English comedians English game show hosts English memoirists English Methodists English satirists English social commentators English political writers English television personalities English television talk show hosts International Emmy Founders Award winners Knights Bachelor Officers of the Order of the British Empire People educated at Gillingham Grammar School, Kent People educated at St Hugh's School, Woodhall Spa People from Raunds People from Tenterden People from Test Valley People from Wellingborough People who died at sea Primetime Emmy Award winners 20th-century British businesspeople

Sir David Paradine Frost (7 April 1939 – 31 August 2013) was a British television host, journalist, comedian and writer. He rose to prominence during the

"Obituary: Sir David Frost"

''

''TimeLine Theatre Company''. Retrieved 8 October 2022. While living in Gillingham, Kent, he was taught in the Bible class of the Sunday school at his father's church (Byron Road Methodist) by David Gilmore Harvey, and subsequently started training as a Methodist

''BBC News''. 2 September 2013. Frost attended Barnsole Road Primary School in Gillingham,

"The Saturday interview: David Frost"

''The Guardian''. London. The new satirical magazine ''

, Teletronic Frost, according to Kitty Muggeridge in 1967, had "risen without a trace." He was involved in the station's early years as a presenter. On 20 and 21 July 1969, during the

"Sir David Frost: Pioneering journalist and broadcaster whose fame often equalled that of his interviewees"

''The Independent'' London. he part-financed ''

Frost was one of the "Famous Five" who launched

Frost was one of the "Famous Five" who launched

Frost was the only person to have interviewed all eight

Frost was the only person to have interviewed all eight

Frost was known for several relationships with high-profile women. In the mid-1960s, he dated British actress Janette Scott, between her marriages to songwriter

Frost was known for several relationships with high-profile women. In the mid-1960s, he dated British actress Janette Scott, between her marriages to songwriter

for a ten-day cruise in the satire boom

The satire boom was the output of a generation of British satirical writers, journalists and performers at the beginning of the 1960s. The satire boom is often regarded as having begun with the first performance of '' Beyond the Fringe'' on 22 Aug ...

in the United Kingdom when he was chosen to host the satirical programme ''That Was the Week That Was

''That Was the Week That Was'', informally ''TWTWTW'' or ''TW3'', is a satirical television comedy programme that aired on BBC Television in 1962 and 1963. It was devised, produced, and directed by Ned Sherrin and Jack (aka John) Duncan, and pr ...

'' in 1962. His success on this show led to work as a host on American television. He became known for his television interviews with senior political figures, among them the Nixon interviews with US president Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

in 1977 which were adapted into a stage play and film

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmospher ...

. Frost interviewed all eight British prime ministers serving between 1964 and 2016 and all seven American presidents in office between 1969 and 2008.

Frost was one of the people behind the launch of ITV station TV-am

TV-am was a TV company that broadcast the ITV franchise for breakfast television in the United Kingdom from 1 February 1983 until 31 December 1992. The station was the UK's first national operator of a commercial breakfast television franchis ...

in 1983. He was the inaugural host of the US news magazine programme ''Inside Edition

''Inside Edition'' is an American news broadcasting newsmagazine program that is distributed in first-run syndication by CBS Media Ventures. Having premiered on January 9, 1989, it is the longest-running syndicated-newsmagazine program that is no ...

''. He hosted the Sunday morning interview programme '' Breakfast with Frost'' for the BBC from 1993 to 2005, and spent two decades as host of '' Through the Keyhole''. From 2006 to 2012, he hosted the weekly programme '' Frost Over the World'' on Al Jazeera English

Al Jazeera English (AJE; ar, الجزيرة, translit=al-jazīrah, , literally "The Peninsula", referring to the Qatar Peninsula) is an international 24-hour English-language news channel owned by the Al Jazeera Media Network, which is o ...

, and the weekly programme ''The Frost Interview'' from 2012. He received the BAFTA Fellowship

The BAFTA Fellowship, or the Academy Fellowship, is a lifetime achievement award presented by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) in recognition of "outstanding achievement in the art forms of the moving image". The award is t ...

from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

in 2005 and the Lifetime Achievement Award

Lifetime achievement awards are awarded by various organizations, to recognize contributions over the whole of a career, rather than or in addition to single contributions.

Such awards, and organizations presenting them, include:

A

* A.C. ...

at the Emmy Awards

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

in 2009.

Frost died on 31 August 2013, aged 74, on board the cruise ship , where he had been engaged as a speaker. His memorial stone was unveiled in Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

in March 2014.

Early life

David Paradine Frost was born inTenterden

Tenterden is a town in the borough of Ashford in Kent, England. It stands on the edge of the remnant forest the Weald, overlooking the valley of the River Rother. It was a member of the Cinque Ports Confederation. Its riverside today is ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, on 7 April 1939, the son of a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

minister of Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

descent,Jeffries, Stuart (1 September 2013)"Obituary: Sir David Frost"

''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

''. London. the Rev. Wilfred John "W. J." Paradine Frost, and his wife, Mona (Aldrich); he had two elder sisters."Frost/Nixon"''TimeLine Theatre Company''. Retrieved 8 October 2022. While living in Gillingham, Kent, he was taught in the Bible class of the Sunday school at his father's church (Byron Road Methodist) by David Gilmore Harvey, and subsequently started training as a Methodist

local preacher

A Methodist local preacher, also known as a licensed preacher, is a layperson who has been accredited by the Methodist Church to lead worship and preach on a frequent basis. With separation from the Church of England by the end of the 18th century ...

, which he did not complete."Obituary: Sir David Frost"''BBC News''. 2 September 2013. Frost attended Barnsole Road Primary School in Gillingham,

St Hugh's School, Woodhall Spa

, established = 1925

, type = Preparatory day and boarding school

, religious_affiliation = Anglican

, head_label = Headmaster

, head = Jeremy Wyld

, chair_label = Chairman ...

, Gillingham Grammar School and finally – while residing in Raunds, Northamptonshire – Wellingborough Grammar School. Throughout his school years he was an avid football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly ...

and cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by st ...

player, and was offered a contract with Nottingham Forest F.C. For two years before going to university he was a lay preacher, following his witnessing of an event presided over by Christian evangelist Billy Graham

William Franklin Graham Jr. (November 7, 1918 – February 21, 2018) was an American evangelist and an ordained Southern Baptist minister who became well known internationally in the late 1940s. He was a prominent evangelical Christi ...

.

Frost studied at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, often referred to simply as Caius ( ), is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1348, it is the fourth-oldest of the University of Cambridge's 31 colleges and one of t ...

, from 1958, graduating with a Third in English. He was editor of both the university's student paper, '' Varsity'', and the literary magazine ''Granta

''Granta'' is a literary magazine and publisher in the United Kingdom whose mission centres on its "belief in the power and urgency of the story, both in fiction and non-fiction, and the story’s supreme ability to describe, illuminate and ma ...

''. He was also secretary of the Footlights

Cambridge University Footlights Dramatic Club, commonly referred to simply as the Footlights, is an amateur theatrical club in Cambridge, England, founded in 1883 and run by the students of Cambridge University.

History

Footlights' inaugural ...

Drama Society, which included actors such as Peter Cook

Peter Edward Cook (17 November 1937 – 9 January 1995) was an English actor, comedian, satirist, playwright and screenwriter. He was the leading figure of the British satire boom of the 1960s, and he was associated with the anti-establishme ...

and John Bird. During this period Frost appeared on television for the first time in an edition of Anglia Television

ITV Anglia, previously known as Anglia Television, is the ITV franchise holder for the East of England. The station is based at Anglia House in Norwich, with regional news bureaux in Cambridge and Northampton. ITV Anglia is owned and operated b ...

's ''Town And Gown'', performing several comic characters. "The first time I stepped into a television studio", he once remembered, "it felt like home. It didn't scare me. Talking to the camera seemed the most natural thing in the world."

According to some accounts, Frost was the victim of snobbery from the group with which he associated at Cambridge, which has been confirmed by Barry Humphries

John Barry Humphries (born 17 February 1934) is an Australian comedian, actor, author and satirist. He is best known for writing and playing his on-stage and television alter egos Dame Edna Everage and Sir Les Patterson. He is also a film pr ...

. Christopher Booker

Christopher John Penrice Booker (7 October 1937 – 3 July 2019) was an English journalist and author. He was a founder and first editor of the satirical magazine '' Private Eye'' in 1961. From 1990 onward he was a columnist for '' The Sunday ...

, while asserting that Frost's one defining characteristic was ambition, commented that he was impossible to dislike. According to satirist John Wells, Old Etonian

Eton College () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI of England, Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. i ...

actor Jonathan Cecil

Jonathan Hugh Gascoyne-Cecil (22 February 1939 – 22 September 2011), known as Jonathan Cecil, was an English theatre, film, and television actor.

Early life

Cecil was born in London, England, the son of Lord David Cecil and the gr ...

congratulated Frost around this time for "that wonderfully silly voice" he used while performing, but then discovered that it was Frost's real voice.

After leaving university, Frost became a trainee at Associated-Rediffusion

Associated-Rediffusion, later Rediffusion London, was the British ITV franchise holder for London and parts of the surrounding counties, on weekdays between 22 September 1955 and 29 July 1968. It was the first ITA franchisee to go on air, ...

. Meanwhile, having already gained an agent, Frost performed in cabaret at the Blue Angel nightclub in Berkeley Square

Berkeley Square is a garden square in the West End of London. It is one of the best known of the many squares in London, located in Mayfair in the City of Westminster. It was laid out in the mid 18th century by the architect William Ke ...

, London during the evenings.

''That Was the Week That Was''

Frost was chosen by writer and producerNed Sherrin

Edward George Sherrin (18 February 1931 – 1 October 2007) was an English broadcaster, author and stage director. He qualified as a barrister and then worked in independent television before joining the BBC. He appeared in a variety of r ...

to host the satirical programme ''That Was the Week That Was

''That Was the Week That Was'', informally ''TWTWTW'' or ''TW3'', is a satirical television comedy programme that aired on BBC Television in 1962 and 1963. It was devised, produced, and directed by Ned Sherrin and Jack (aka John) Duncan, and pr ...

'', or ''TW3'', after Frost's flatmate John Bird suggested Sherrin should see his act at The Blue Angel. The series, which ran for less than 18 months during 1962–63, was part of the satire boom

The satire boom was the output of a generation of British satirical writers, journalists and performers at the beginning of the 1960s. The satire boom is often regarded as having begun with the first performance of '' Beyond the Fringe'' on 22 Aug ...

in early 1960s Britain and became a popular programme.

The involvement of Frost in ''TW3'' led to an intensification of the rivalry with Peter Cook who accused him of stealing material and dubbed Frost "the bubonic plagiarist".Hattenstone, Simon (2 July 2011)"The Saturday interview: David Frost"

''The Guardian''. London. The new satirical magazine ''

Private Eye

''Private Eye'' is a British fortnightly satirical and current affairs news magazine, founded in 1961. It is published in London and has been edited by Ian Hislop since 1986. The publication is widely recognised for its prominent critici ...

'' also mocked him at this time. Frost visited the U.S. during the break between the two series of ''TW3'' in the summer of 1963 and stayed with the producer of the New York City production of ''Beyond The Fringe''. Frost was unable to swim, but still jumped into the pool, and nearly drowned until he was saved by Peter Cook. At the memorial service for Cook in 1995, Alan Bennett

Alan Bennett (born 9 May 1934) is an English actor, author, playwright and screenwriter. Over his distinguished entertainment career he has received numerous awards and honours including two BAFTA Awards, four Laurence Olivier Awards, and two ...

recalled that rescuing Frost was the one regret Cook frequently expressed.

For the first three editions of the second series in 1963, the BBC attempted to limit the team by scheduling repeats of ''The Third Man

''The Third Man'' is a 1949 British film noir directed by Carol Reed, written by Graham Greene and starring Joseph Cotten, Alida Valli, Orson Welles, and Trevor Howard. Set in postwar Vienna, the film centres on American Holly Martins (Cotten ...

'' television series after the programme, thus preventing overruns. Frost took to reading synopses of the episodes at the end of the programme as a means of sabotage. After the BBC's Director General Hugh Greene

Sir Hugh Carleton Greene (15 November 1910 – 19 February 1987) was a British television executive and journalist. He was director-general of the BBC from 1960 to 1969.

After working for newspapers in the 1930s, Greene spent most of his later ...

instructed that the repeats should be abandoned, ''TW3'' returned to being open-ended. More sombrely, on 23 November 1963, a tribute to the assassinated President John F. Kennedy, an event which had occurred the previous day, formed an entire edition of ''That Was the Week That Was''.

An American version of ''TW3'' ran after the original British series had ended. Following a pilot episode on 10 November 1963, the 30-minute US series, also featuring Frost, ran on NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

from 10 January 1964 to May 1965. In 1985, Frost produced and hosted a television special in the same format, ''That Was the Year That Was'', on NBC.

After ''TW3''

Frost fronted various programmes following the success of ''TW3'', including its immediate successor, ''Not So Much a Programme, More a Way of Life

''Not So Much a Programme, More a Way of Life'' (commonly abbreviated to ''NSMAPMAWOL'', pronounced ens-map-may-wall and stylised as Not so much a programme, more a way of Life) is a BBC-TV satire programme produced by Ned Sherrin, which aired d ...

'', which he co-chaired with Willie Rushton

William George Rushton (18 August 1937 – 11 December 1996) was an English cartoonist, satirist, comedian, actor and performer who co-founded the satirical magazine ''Private Eye''.

Early life

Rushton was born 18 August 1937 in 3 Wilbraham Plac ...

and poet P. J. Kavanagh

P. J. Kavanagh

FRSL (6 January 1931 – 26 August 2015) was an English poet, lecturer, actor, broadcaster and columnist. His father was the ''ITMA'' scriptwriter Ted Kavanagh.

Life

Patrick Joseph Kavanagh worked as a Butlin's Redcoat, th ...

. Screened on three evenings each week, this series was dropped after a sketch was found to be offensive to Catholics and another to the British royal family. More successful was '' The Frost Report'', broadcast between 1966 and 1967. The show launched the television careers of John Cleese

John Marwood Cleese ( ; born 27 October 1939) is an English actor, comedian, screenwriter, and producer. Emerging from the Cambridge Footlights in the 1960s, he first achieved success at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and as a scriptwriter and ...

, Ronnie Barker

Ronald William George Barker (25 September 1929 – 3 October 2005) was an English actor, comedian and writer. He was known for roles in British comedy television series such as ''Porridge'', ''The Two Ronnies'', and '' Open All Hours''.

...

, and Ronnie Corbett

Ronald Balfour Corbett (4 December 1930 – 31 March 2016) was a Scottish actor, broadcaster, comedian and writer. He had a long association with Ronnie Barker in the BBC television comedy sketch show ''The Two Ronnies''. He achieved promine ...

, who appeared together in the Class sketch

The ''Class sketch'' is a comedy sketch first broadcast in an episode of David Frost's satirical comedy programme '' The Frost Report'' on 7 April 1966. It has been described as a "genuinely timeless sketch, ingeniously satirising the British cl ...

.

Frost signed for Rediffusion

Rediffusion was a business that distributed radio and TV signals through wired relay networks. The business gave rise to a number of other companies, including Associated-Rediffusion, later known as Rediffusion London, the first ITV ( commer ...

, the ITV weekday contractor in London, to produce a "heavier" interview-based show called ''The Frost Programme''. Guests included Oswald Mosley and Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of So ...

n premier Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to 1 ...

. His memorable dressing-down of insurance fraudster Emil Savundra

Michael Marion Emil Anacletus Pierre Savundranayagam (6 July 1923 – 21 December 1976), usually known as Emil Savundra, was a Sri Lankan swindler. The collapse of his Fire, Auto and Marine Insurance Company left about 400,000 motorists in t ...

, regarded as the first example of " trial by television" in the UK, led to concern from ITV executives that it might affect Savundra's right to a fair trial. Frost's introductory words for his television programmes during this period, "Hello, good evening and welcome", became his catchphrase

A catchphrase (alternatively spelled catch phrase) is a phrase or expression recognized by its repeated utterance. Such phrases often originate in popular culture and in the arts, and typically spread through word of mouth and a variety of mass ...

and were often mimicked.

Frost was a member of a successful consortium, including former executives from the BBC, that bid for an ITV franchise in 1967. This became London Weekend Television

London Weekend Television (LWT) (now part of the non-franchised ITV London region) was the ITV network franchise holder for Greater London and the Home Counties at weekends, broadcasting from Fridays at 5.15 pm (7:00 pm from 1968 un ...

, which began broadcasting in July 1968. The station began with a programming policy that was considered "highbrow

Used colloquially as a noun or adjective, "highbrow" is synonymous with intellectual; as an adjective, it also means elite, and generally carries a connotation of high culture. The term, first recorded in 1875, draws its metonymy from the pseudo ...

" and suffered launch problems with low audience ratings and financial problems. A September 1968 meeting of the Network Programme Committee, which made decisions about the channel's scheduling, was particularly fraught, with Lew Grade

Lew Grade, Baron Grade, (born Lev Winogradsky; 25 December 1906 – 13 December 1998) was a British media proprietor and impresario. Originally a dancer, and later a talent agent, Grade's interest in television production began in 19 ...

expressing hatred of Frost in his presence."British TV History: The ITV Story: Part 10: The New Franchises", Teletronic Frost, according to Kitty Muggeridge in 1967, had "risen without a trace." He was involved in the station's early years as a presenter. On 20 and 21 July 1969, during the

British television Apollo 11 coverage

British television coverage of the Apollo 11 mission, humanity's first to land on the Moon, lasted from 16 to 24 July 1969. All three UK television channels, BBC1, BBC2 and ITV, provided extensive coverage. Most of the footage covering the event ...

, he presented ''David Frost's Moon Party'' for LWT, a ten-hour discussion and entertainment marathon from LWT's Wembley Studios

Fountain Studios was an independently owned television studio in Wembley Park, northwest London. The company was last part of the Avesco Group plc.

Several companies owned the site before it was bought by Fountain in 1993. Originally a film st ...

, on the night Neil Armstrong

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut and aeronautical engineer who became the first person to walk on the Moon in 1969. He was also a naval aviator, test pilot, and university professor.

...

walked on the moon. Two of his guests on this programme were British historian A. J. P. Taylor and entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr. Around this time Frost interviewed Rupert Murdoch

Keith Rupert Murdoch ( ; born 11 March 1931) is an Australian-born American business magnate. Through his company News Corp, he is the owner of hundreds of local, national, and international publishing outlets around the world, including ...

whose recently acquired Sunday newspaper, the ''News of the World

The ''News of the World'' was a weekly national red top tabloid newspaper published every Sunday in the United Kingdom from 1843 to 2011. It was at one time the world's highest-selling English-language newspaper, and at closure still had one ...

'', had just serialised the memoirs of Christine Keeler

Christine Margaret Keeler (22 February 1942 – 4 December 2017) was an English model and showgirl. Her meeting at a dance club with society osteopath Stephen Ward drew her into fashionable circles. At the height of the Cold War, she became s ...

, a central figure in the Profumo scandal of 1963. For the Australian publisher, this was a bruising encounter, although Frost said that he had not intended it to be. Murdoch confessed to his biographer Michael Wolff that the incident had convinced him that Frost was "an arrogant bastard, nda bloody bugger".

In the late 1960s Frost began an intermittent involvement in the film industry. Setting up David Paradine Ltd in 1966,Leapman, Michael (1 September 2013)"Sir David Frost: Pioneering journalist and broadcaster whose fame often equalled that of his interviewees"

''The Independent'' London. he part-financed ''

The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer

''The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer'' is a 1970 British satirical film starring Peter Cook, and co-written by Cook, John Cleese, Graham Chapman, and Kevin Billington, who directed the film. The film was devised and produced by David Frost u ...

'' (1970), in which the lead character was based partly on Frost, and gained an executive producer credit. In 1976, Frost was the executive producer of the British musical film

Musical film is a film genre in which songs by the characters are interwoven into the narrative, sometimes accompanied by dancing. The songs usually advance the plot or develop the film's characters, but in some cases, they serve merely as brea ...

''The Slipper and the Rose

''The Slipper and the Rose: The Story of Cinderella'' is a 1976 British musical film retelling the classic fairy tale of Cinderella. The film was chosen as the Royal Command Performance motion picture selection for 1976.

Directed by Bryan Forb ...

'', retelling the story of Cinderella

"Cinderella",; french: link=no, Cendrillon; german: link=no, Aschenputtel) or "The Little Glass Slipper", is a folk tale with thousands of variants throughout the world.Dundes, Alan. Cinderella, a Casebook. Madison, Wis: University of Wisconsi ...

.

Frost was the subject of ''This Is Your Life This Is Your Life may refer to:

Television

* ''This Is Your Life'' (American franchise), an American radio and television documentary biography series hosted by Ralph Edwards

* ''This Is Your Life'' (Australian TV series), the Australian versio ...

'' in January 1972 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews

Eamonn Andrews, (19 December 1922 – 5 November 1987) was an Irish radio and television presenter, employed primarily in the United Kingdom from the 1950s to the 1980s. From 1960 to 1964 he chaired the Radio Éireann Authority (now the RTÉ A ...

at London's Quaglino's

Quaglino's is a restaurant in central London which was founded in 1929, closed in 1977, and revived in 1993. From the 1930s through the 1950s, it was popular among the British aristocracy, including the royal family, many of whom were regulars ...

restaurant.

American career from 1968 to 1980

In 1968, he signed a contract worth £125,000 to appear on American television in his own show on three evenings each week, the largest such arrangement for a British television personality at the time. From 1969 to 1972, Frost kept his London shows and fronted ''The David Frost Show'' on the Group W (U.S. Westinghouse Corporation) television stations in the U.S. His 1970 TV special, ''Frost on America'', featured guests such asJack Benny

Jack Benny (born Benjamin Kubelsky, February 14, 1894 – December 26, 1974) was an American entertainer who evolved from a modest success playing violin on the vaudeville circuit to one of the leading entertainers of the twentieth century wit ...

and Tennessee Williams

Thomas Lanier Williams III (March 26, 1911 – February 25, 1983), known by his pen name Tennessee Williams, was an American playwright and screenwriter. Along with contemporaries Eugene O'Neill and Arthur Miller, he is considered among the thr ...

.

In a declassified transcript of a 1972 telephone call between Frost and Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, President Nixon's national security advisor A national security advisor serves as the chief advisor to a national government on matters of security. The advisor is not usually a member of the government's cabinet but is usually a member of various military or security councils.

National sec ...

and secretary of state, Frost urged Kissinger to call chess Grandmaster Bobby Fischer

Robert James Fischer (March 9, 1943January 17, 2008) was an American chess grandmaster and the eleventh World Chess Champion. A chess prodigy, he won his first of a record eight US Championships at the age of 14. In 1964, he won with an 11� ...

and urge him to compete in that year's World Chess Championship

The World Chess Championship is played to determine the world champion in chess. The current world champion is Magnus Carlsen of Norway, who has held the title since 2013.

The first event recognized as a world championship was the 1886 matc ...

. During this call, Frost revealed that he was working on a novel.

Frost interviewed heavyweight boxer Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, ...

in 1974 at his training camp in Deer Lake, Pennsylvania

Deer Lake is a borough in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. The population was 670 at the 2020 census. The mayor of the borough is Larry Kozlowski.

History

The community was founded as a resort community serving coal barons and other members of ...

before "The Rumble in the Jungle

George Foreman vs. Muhammad Ali, billed as ''The Rumble in the Jungle'', was a heavyweight championship boxing match on October 30, 1974, at the 20th of May Stadium (now the Stade Tata Raphaël) in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of t ...

" with George Foreman

George Edward Foreman (born January 10, 1949) is an American former professional boxer, entrepreneur, minister and author. In boxing, he was nicknamed "Big George" and competed between 1967 and 1997. He is a two-time world heavyweight champi ...

. Ali remarked, "Listen David, when I meet this man, if you think the world was surprised when Nixon resigned, wait till I whip Foreman's behind."

In 1977, the Nixon Interviews, which were five 90-minute interviews with former U.S. President Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

, were broadcast. Nixon was paid $600,000 plus a share of the profits for the interviews, which had to be funded by Frost himself after the U.S. television networks turned down the programme, describing it as " checkbook journalism". Frost's company negotiated its own deals to syndicate the interviews with local stations across the U.S. and internationally, creating what Ron Howard

Ronald William Howard (born March 1, 1954) is an American director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. He first came to prominence as a child actor, guest-starring in several television series, including an episode of '' The Twilight Zone''. ...

described as "the first fourth network". Frost taped around 29 hours of interviews with Nixon over four weeks. Nixon, who had previously avoided discussing his role in the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's contin ...

that had led to his resignation as president in 1974, expressed contrition saying, "I let the American people down and I have to carry that burden with me for the rest of my life". Frost asked Nixon whether the president could do something illegal in certain situations such as against antiwar groups and others if he decides "it's in the best interests of the nation or something". Nixon replied: "Well, when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal", by definition.

Following the 1979 Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dyna ...

, Frost was the last person to interview Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 Octob ...

, the deposed Shah

Shah (; fa, شاه, , ) is a royal title that was historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies.Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) It was also used by a variety of ...

of Iran. The interview took place on Contadora Island in Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

in January 1980, and was broadcast by the American Broadcasting Company

The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) is an American commercial broadcast television network. It is the flagship property of the ABC Entertainment Group division of The Walt Disney Company. The network is headquartered in Burbank, Calif ...

in the U.S. on 17 January. The Shah talks about his wealth, his illness, the SAVAK

SAVAK ( fa, ساواک, abbreviation for ''Sâzemân-e Ettelâ'ât va Amniat-e Kešvar'', ) was the secret police, domestic security and intelligence service in Iran during the reign of the Pahlavi dynasty. SAVAK operated from 1957 until prim ...

, the torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

during his reign, Khomeini

Ruhollah Khomeini, Ayatollah Khomeini, Imam Khomeini ( , ; ; 17 May 1900 – 3 June 1989) was an Iranian political and religious leader who served as the first supreme leader of Iran from 1979 until his death in 1989. He was the founder of ...

, his threat of extradition to Iran and draws a summary of the current situation in Iran.

Frost was an organiser of the Music for UNICEF Concert at the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

in 1979. Ten years later, he was hired as the anchor of new American tabloid news program ''Inside Edition

''Inside Edition'' is an American news broadcasting newsmagazine program that is distributed in first-run syndication by CBS Media Ventures. Having premiered on January 9, 1989, it is the longest-running syndicated-newsmagazine program that is no ...

''. He was dismissed after only three weeks because of poor ratings. It seems he was "considered too high-brow for the show's low-brow format."

After 1980

Frost was one of the "Famous Five" who launched

Frost was one of the "Famous Five" who launched TV-am

TV-am was a TV company that broadcast the ITV franchise for breakfast television in the United Kingdom from 1 February 1983 until 31 December 1992. The station was the UK's first national operator of a commercial breakfast television franchis ...

in February 1983; however, like LWT in the late 1960s, the station began with an unsustainable "highbrow" approach. Frost remained a presenter after restructuring. ''Frost on Sunday'' began in September 1983 and continued until the station lost its franchise at the end of 1992. Frost had been part of an unsuccessful consortium, CPV-TV

CPV-TV (from Chrysalis, Paradine and Virgin) was a company which had bid for three ITV franchises at the 1991 ITV franchise auction.

It was a consortium led by Sir David Frost and Richard Branson with further backing from the Chrysalis Group ...

, with Richard Branson

Sir Richard Charles Nicholas Branson (born 18 July 1950) is a British billionaire, entrepreneur, and business magnate. In the 1970s he founded the Virgin Group, which today controls more than 400 companies in various fields.

Branson expressed ...

and other interests, which had attempted to acquire three ITV contractor franchises prior to the changes made by the Independent Television Commission

The Independent Television Commission (ITC) licensed and regulated commercial television services in the United Kingdom (except S4C in Wales) between 1 January 1991 and 28 December 2003.

History

The creation of ITC, by the Broadcasting Act ...

in 1991. After transferring from ITV, his Sunday morning interview programme '' Breakfast with Frost'' ran on the BBC from January 1993 until 29 May 2005. For a time it ran on BSB before moving to BBC 1

BBC One is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's flagship network and is known for broadcasting mainstream programming, which includes BBC News television bulletins, ...

.

Frost hosted '' Through the Keyhole'', which ran on several UK channels from 1987 until 2008 and also featured Loyd Grossman. Produced by his own production company, the programme was first shown in prime time and on daytime television in its later years.

Frost worked for Al Jazeera English

Al Jazeera English (AJE; ar, الجزيرة, translit=al-jazīrah, , literally "The Peninsula", referring to the Qatar Peninsula) is an international 24-hour English-language news channel owned by the Al Jazeera Media Network, which is o ...

, presenting a live weekly hour-long current affairs programme, '' Frost Over The World'', which started when the network launched in November 2006. The programme regularly made headlines with interviewees such as Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of t ...

, President Omar al-Bashir of Sudan, Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto ( ur, بینظیر بُھٹو; sd, بينظير ڀُٽو; Urdu ; 21 June 1953 – 27 December 2007) was a Pakistani politician who served as the 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 t ...

of Pakistan and President Daniel Ortega

José Daniel Ortega Saavedra (; born 11 November 1945) is a Nicaraguan revolutionary and politician serving as President of Nicaragua since 2007. Previously he was leader of Nicaragua from 1979 to 1990, first as coordinator of the Junta of Na ...

of Nicaragua. The programme was produced by the former ''Question Time

A question time in a parliament occurs when members of the parliament ask questions of government ministers (including the prime minister), which they are obliged to answer. It usually occurs daily while parliament is sitting, though it can be ca ...

'' editor and ''Independent on Sunday

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publishe ...

'' journalist Charlie Courtauld. Frost was one of the first to interview the man who authored the Fatwa on Terrorism

The ''Fatwa on Terrorism and Suicide Bombings'' is a 600-page (Urdu version), 512-page (English version) Islamic decree by scholar Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri which demonstrates from the Quran and Sunnah that terrorism and suicide bombings are unjust ...

, Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri

Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri ( ur, ; born 19 February 1951) is a Pakistani–Canadian Islamic scholar and former politician who founded Minhaj-ul-Quran International and Pakistan Awami Tehreek.

He was also a professor of international co ...

.

During his career as a broadcaster, Frost became one of Concorde

The Aérospatiale/BAC Concorde () is a retired Franco-British supersonic airliner jointly developed and manufactured by Sud Aviation (later Aérospatiale) and the British Aircraft Corporation (BAC).

Studies started in 1954, and France an ...

's most frequent fliers, having flown between London and New York an average of 20 times per year for 20 years.

In 2007, Frost hosted a discussion with Libya's leader Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by '' The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

as part of the Monitor Group

Monitor Deloitte is the multinational strategy consulting practice of Deloitte Consulting. Monitor Deloitte specializes in providing strategy consultation services to the senior management of major organizations and governments. It helps its clie ...

's involvement in the country. In June 2010, Frost presented ''Frost on Satire'', an hour-long BBC Four

BBC Four is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It was launched on 2 March 2002

documentary looking at the history of television satire.

Achievements

Frost was the only person to have interviewed all eight

Frost was the only person to have interviewed all eight British prime ministers

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the principal minister of the crown of His Majesty's Government, and the head of the British Cabinet. There is no specific date for when the office of prime minister first appeared, as the role was no ...

serving between 1964 and 2016 (Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

, Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 to 1975. Heath a ...

, James Callaghan

Leonard James Callaghan, Baron Callaghan of Cardiff, ( ; 27 March 191226 March 2005), commonly known as Jim Callaghan, was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1976 to 1979 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1976 to 1980. Callaghan is ...

, Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

, John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament (MP) for Huntingdon, formerly Hunting ...

, Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of t ...

, Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chancellor of the Exchequer in Tony ...

, and David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

) and all seven U.S. presidents in office between 1969 and 2008 (Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

, Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

, Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

, and George W. Bush).

He was a patron and former vice-president of the Motor Neurone Disease Association

The Motor Neurone Disease Association (MND Association) focuses on improving access to care, research and campaigning for those people living with or affected by motor neurone disease (MND) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. MND is also know ...

charity, as well as being a patron of the Alzheimer's Research Trust

Alzheimer's Research UK (ARUK) is a dementia research charity in the United Kingdom, founded in 1992 as the Alzheimer's Research Trust.

ARUK funds scientific studies to find ways to treat, cure or prevent all forms of dementia, including Alzhei ...

, Hearing Star Benevolent Fund, East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

's Children's Hospices, the Home Farm Trust and the Elton John AIDS Foundation

The Elton John AIDS Foundation (EJAF) is a nonprofit organization, established by rock musician Sir Elton John in 1992 in the United States and 1993 in the United Kingdom to support innovative HIV prevention, education programs, direct care a ...

. He was also recognised for his contributions to the women's charity "Wellbeing for Women".

After having been in television for 40 years, Frost was estimated to be worth £200 million by the ''Sunday Times Rich List

The ''Sunday Times Rich List'' is a list of the 1,000 wealthiest people or families resident in the United Kingdom ranked by net wealth. The list is updated annually in April and published as a magazine supplement by British national Sunday new ...

'' in 2006, a figure he considered a significant overestimate in 2011. The valuation included the assets of his main British company and subsidiaries, plus homes in London and the country.

''Frost/Nixon''

''Frost/Nixon'' was originally a play written byPeter Morgan

Peter Julian Robin Morgan, (10 April 1963) is a British screenwriter and playwright. He is the playwright behind '' The Audience'' and '' Frost/Nixon'' and the screenwriter of ''The Queen'' (2006), '' Frost/Nixon'' (2008), '' The Damned Unit ...

, developed from the interviews that Frost had conducted with Richard Nixon in 1977. '' Frost/Nixon'' was presented as a stage production in London in 2006 and on Broadway in 2007. Frank Langella

Frank A. Langella Jr. (; born January 1, 1938) is an American stage and film actor. He has won four Tony Awards: two for Best Leading Actor in a Play for his performance as Richard Nixon in Peter Morgan's '' Frost/Nixon'' and as André in Flor ...

won a Leading Actor Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual c ...

for his portrayal of Nixon; the play also received nominations for Best Play and Best Direction.

The play was adapted into a Hollywood motion picture entitled '' Frost/Nixon'' and starring Michael Sheen

Michael Christopher Sheen OBE (born 5 February 1969) is a Welsh actor, television producer and political activist. After training at London's Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA), he worked mainly in theatre throughout the 1990s with stage rol ...

as Frost and Langella as Nixon, both reprising their stage roles. The film was released in 2008 and directed by Ron Howard

Ronald William Howard (born March 1, 1954) is an American director, producer, screenwriter, and actor. He first came to prominence as a child actor, guest-starring in several television series, including an episode of '' The Twilight Zone''. ...

. It was nominated for five Golden Globe Award

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of ...

s, winning none: Best Motion Picture-Drama, Best Director-Drama, Best Actor-Drama (Langella), Best Screenplay, and Best Original Score. It was also nominated for five Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

s, again winning none: Best Picture, Best Actor (Langella), Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Film Editing.

In February 2009, Frost was featured on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is the national broadcaster of Australia. It is principally funded by direct grants from the Australian Government and is administered by a government-appointed board. The ABC is a publicly-owne ...

's international affairs programme ''Foreign Correspondent

A correspondent or on-the-scene reporter is usually a journalist or commentator for a magazine, or an agent who contributes reports to a newspaper, or radio or television news, or another type of company, from a remote, often distant, locat ...

'' in a report titled "The World According To Frost", reflecting on his long career and portrayal in the film ''Frost/Nixon''.

Personal life

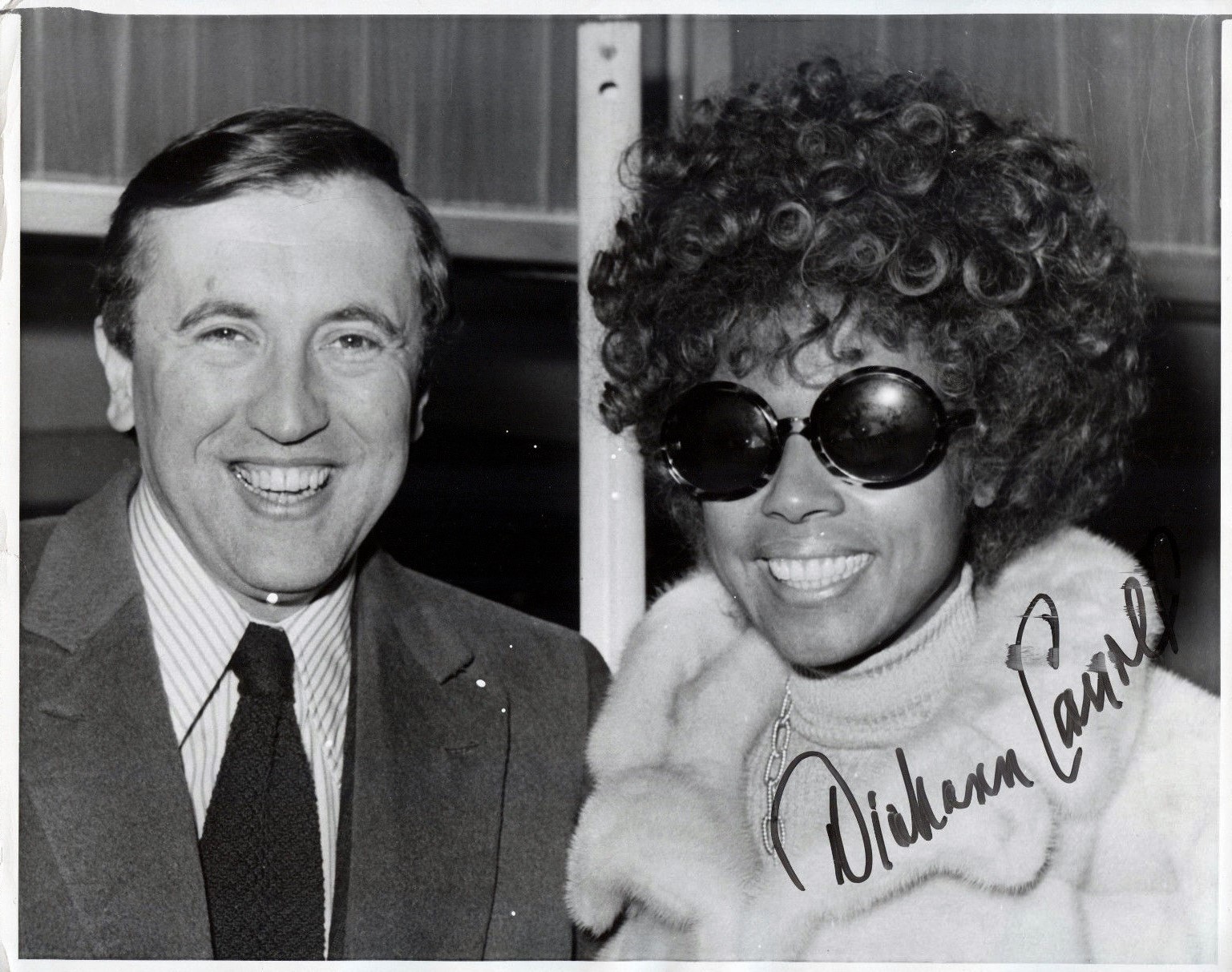

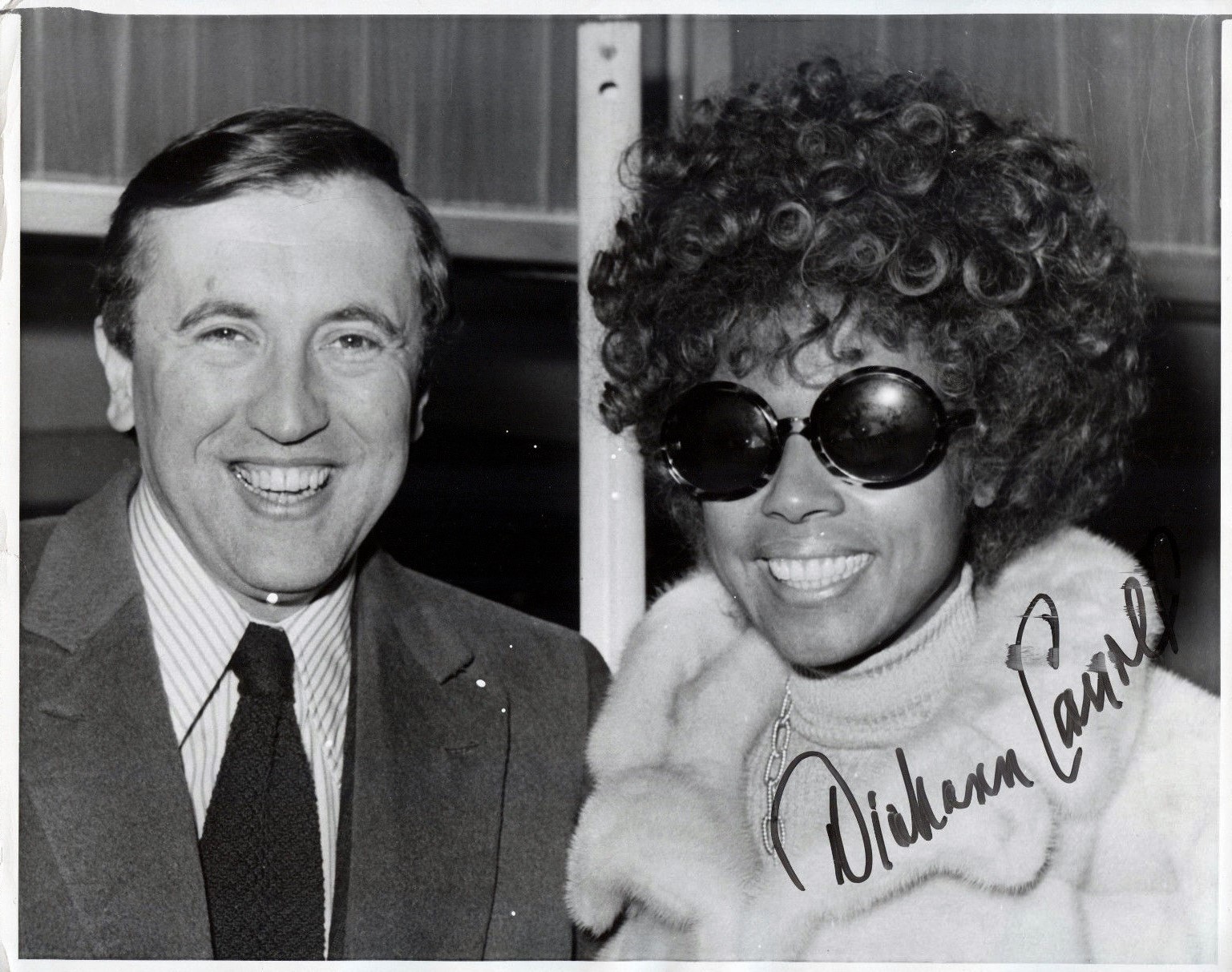

Frost was known for several relationships with high-profile women. In the mid-1960s, he dated British actress Janette Scott, between her marriages to songwriter

Frost was known for several relationships with high-profile women. In the mid-1960s, he dated British actress Janette Scott, between her marriages to songwriter Jackie Rae

John Arthur Rae, CM, DFC (May 14, 1921 – October 5, 2006) was a Canadian singer, songwriter and television performer.

Biography

He was born John Arthur Cohen to immigrants in Winnipeg, Manitoba in 1921. His father Goodman Cohen was Lithu ...

and singer Mel Tormé

Melvin Howard Tormé (September 13, 1925 – June 5, 1999), nicknamed "The Velvet Fog", was an American musician, singer, composer, arranger, drummer, actor, and author. He composed the music for " The Christmas Song" ("Chestnuts Roasting on an ...

; in the early 1970s he was engaged to American actress Diahann Carroll

Diahann Carroll (; born Carol Diann Johnson; July 17, 1935 – October 4, 2019) was an American actress, singer, model, and activist. She rose to prominence in some of the earliest major film studio, major studio films to feature black cas ...

; between 1972 and 1977 he had a relationship with British socialite Caroline Cushing; in 1981, he married Lynne Frederick, widow of Peter Sellers

Peter Sellers (born Richard Henry Sellers; 8 September 1925 – 24 July 1980) was an English actor and comedian. He first came to prominence performing in the BBC Radio comedy series ''The Goon Show'', featured on a number of hit comic songs ...

, but they divorced the following year. He also had an 18-year intermittent affair with American actress Carol Lynley

Carol Lynley (born Carole Ann Jones; February 13, 1942 – September 3, 2019) was an American actress known for her roles in the films ''Blue Denim'' (1959) and '' The Poseidon Adventure'' (1972).

Lynley was born in Manhattan to an Irish ...

.

On 19 March 1983, Frost married Lady Carina Fitzalan-Howard, daughter of the 17th Duke of Norfolk. Three sons were born to the couple over the next five years. His second son, Wilfred Frost

Wilfred Frost (born 7 August 1985) is a contributor for Sky News, NBC and CNBC.

Early life and education

Frost is the son of Sir David Frost, an interviewer and television host, and Lady Carina Fitzalan-Howard, a daughter of the 17th Duke of Nor ...

, followed in his father's footsteps and currently works as an anchor at Sky News

Sky News is a British free-to-air television news channel and organisation. Sky News is distributed via an English-language radio news service, and through online channels. It is owned by Sky Group, a division of Comcast. John Ryley is the he ...

and CNBC

CNBC (formerly Consumer News and Business Channel) is an American basic cable business news channel. It provides business news programming on weekdays from 5:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m., Eastern Time, while broadcasting talk s ...

. They lived for many years in Chelsea, London

Chelsea is an affluent area in west London, England, due south-west of Charing Cross by approximately 2.5 miles. It lies on the north bank of the River Thames and for postal purposes is part of the south-western postal area.

Chelsea histori ...

, and kept a weekend home at Michelmersh Court

Michelmersh Court is a former rectory in the village of Michelmersh in Hampshire, southern England. A Listed building#England and Wales, Grade II* listed building, it is now a private house.

Built in the late 18th century, it was altered and exte ...

in Hampshire.

Death

On 31 August 2013, Frost was aboard theCunard

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Ber ...

cruise ship when he died of a heart attack at the age of 74.Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

, ending in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

."Sir David Frost has died"''ITV News''. 1 September 2013. A

post-mortem

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any d ...

found that Frost had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM, or HOCM when obstructive) is a condition in which the heart becomes thickened without an obvious cause. The parts of the heart most commonly affected are the interventricular septum and the ventricles. This r ...

. Frost's son Miles died from the same condition at the age of 31 in 2015.

A funeral service was held at Holy Trinity Church in Nuffield, Oxfordshire, on 12 September 2013, after which he was interred in the church's graveyard.

On 13 March 2014, a memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, at which Frost was honoured with a memorial stone in Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

.

Tributes

British Prime MinisterDavid Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

paid tribute, saying: "He could be—and certainly was with me—both a friend and a fearsome interviewer." Michael Grade

Michael Ian Grade, Baron Grade of Yarmouth, (born 8 March 1943) is an English television executive and businessman. He has held a number of senior roles in television, including controller of BBC1 (1984–1986), chief executive of Channel 4 (1 ...

commented: "He was kind of a television renaissance man

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

. He could put his hand to anything. He could turn over Richard Nixon or he could win the comedy prize at the Montreux Golden Rose festival."

Selected awards and honours

* 1970: Officer of theOrder of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

(OBE)

* 1970: Honorary Doctor of Laws

A Doctor of Law is a degree in law. The application of the term varies from country to country and includes degrees such as the Doctor of Juridical Science (J.S.D. or S.J.D), Juris Doctor (J.D.), Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), and Legum Doctor ...

degree of Emerson College

Emerson College is a private college with its main campus in Boston, Massachusetts. It also maintains campuses in Hollywood, Los Angeles, California and Well, Limburg, Netherlands ( Kasteel Well). Founded in 1880 by Charles Wesley Emerson as a ...

* 1993: Knight Bachelor

The title of Knight Bachelor is the basic rank granted to a man who has been knighted by the monarch but not inducted as a member of one of the organised orders of chivalry; it is a part of the British honours system. Knights Bachelor are ...

* 1994: Honorary doctoral degree of the University of Sussex

, mottoeng = Be Still and Know

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £14.4 million (2020)

, budget = £319.6 million (2019–20)

, chancellor = Sanjeev Bhaskar

, vice_chancellor = Sasha Roseneil

, ...

* 2000: Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet ...

* 2005: Fellowship of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

BAFTA

* 2009: Honorary Doctor of Letters

Doctor of Letters (D.Litt., Litt.D., Latin: ' or ') is a terminal degree in the humanities that, depending on the country, is a higher doctorate after the Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) degree or equivalent to a higher doctorate, such as the Docto ...

degree of the University of Winchester

, mottoeng = Wisdom and Knowledge

, established = 1840 - Winchester Diocesan Training School1847 - Winchester Training College1928 - King Alfred's College2005 - University of Winchester

, type = Public research university

...

* 2009: Lifetime Achievement Award

Lifetime achievement awards are awarded by various organizations, to recognize contributions over the whole of a career, rather than or in addition to single contributions.

Such awards, and organizations presenting them, include:

A

* A.C. ...

at the Emmy Award

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

s

Bibliography

; Non-fiction * ''How to Live Under Labour – or at Least Have as Much Chance as Anyone Else'' (1964) * ''To England with Love'' (1968). WithAntony Jay

Sir Antony Rupert Jay, (20 April 1930 – 21 August 2016) was an English writer, broadcaster, producer and director. With Jonathan Lynn, he co-wrote the British political comedies '' Yes Minister'' and ''Yes, Prime Minister'' (1980–88). He al ...

.

* ''The Presidential Debate, 1968: David Frost talks with Vice-President Hubert H. Humphrey (and others)'' (1968).

* ''The Americans'' (1970)

* ''Billy Graham Talks with David Frost'' (1972)

* ''Whitlam and Frost: The Full Text of Their TV Conversations Plus Exclusive New Interviews'' (1974)

* ''"I Gave Them a Sword": Behind the Scenes of the Nixon Interviews'' (1978). Reissued as ''Frost/Nixon'' in 2007.

* ''David Frost's Book of Millionaires, Multimillionaires, and Really Rich People'' (1984)

* ''The World's Shortest Books'' (1987)

* ''An Autobiography. Part 1: From Congregations to Audiences'' (1993)

; With Michael Deakin and illustrated by Willie Rushton

William George Rushton (18 August 1937 – 11 December 1996) was an English cartoonist, satirist, comedian, actor and performer who co-founded the satirical magazine ''Private Eye''.

Early life

Rushton was born 18 August 1937 in 3 Wilbraham Plac ...

* ''I Could Have Kicked Myself: David Frost's Book of the World's Worst Decisions'' (1982)

* ''Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?'' (1983)

* ''If You'll Believe That'' (1986)

; With Michael Shea

* ''The Mid-Atlantic Companion, or, How to Misunderstand Americans as Much as They Misunderstand Us'' (1986)

* ''The Rich Tide: Men, Women, Ideas and Their Transatlantic Impact'' (1986)

References

External links

* * * *David Frost

BBC News

BBC News is an operational business division of the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) responsible for the gathering and broadcasting of news and current affairs in the UK and around the world. The department is the world's largest broadc ...

profile

David Frost

on TV Cream

TV Cream on Paradine Productions

{{DEFAULTSORT:Frost, David 1939 births 2013 deaths Al Jazeera people Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge BAFTA fellows BBC newsreaders and journalists British broadcast news analysts British reporters and correspondents British television producers English comedians English game show hosts English memoirists English Methodists English satirists English social commentators English political writers English television personalities English television talk show hosts International Emmy Founders Award winners Knights Bachelor Officers of the Order of the British Empire People educated at Gillingham Grammar School, Kent People educated at St Hugh's School, Woodhall Spa People from Raunds People from Tenterden People from Test Valley People from Wellingborough People who died at sea Primetime Emmy Award winners 20th-century British businesspeople