The Black Country on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Black Country is an area of the

The Black Country has no single set of defined boundaries. Some traditionalists define it as "the area where the coal seam comes to the surface – so

The Black Country has no single set of defined boundaries. Some traditionalists define it as "the area where the coal seam comes to the surface – so

Official use of the name came in 1987 with the

Official use of the name came in 1987 with the

A few Black Country places such as Wolverhampton, Bilston and Wednesfield are mentioned in Anglo-Saxon charters and chronicles and the forerunners of a number of Black Country towns and villages such as Cradley, Dudley, Smethwick, and Halesowen are included in the

A few Black Country places such as Wolverhampton, Bilston and Wednesfield are mentioned in Anglo-Saxon charters and chronicles and the forerunners of a number of Black Country towns and villages such as Cradley, Dudley, Smethwick, and Halesowen are included in the  In the middle of the 18th century, Bilston became well known for the craft of

In the middle of the 18th century, Bilston became well known for the craft of  In 1913, the Black Country was the location of arguably one of the most important strikes in British trade union history when the workers employed in the area's steel tube trade came out for two months in a successful demand for a 23 shilling minimum weekly wage for unskilled workers, giving them pay parity with their counterparts in nearby Birmingham. This action commenced on 9 May in Wednesbury, at the Old Patent tube works of John Russell & Co. Ltd., and within weeks upwards of 40,000 workers across the Black Country had joined the dispute. Notable figures in the labour movement, including a key proponent of

In 1913, the Black Country was the location of arguably one of the most important strikes in British trade union history when the workers employed in the area's steel tube trade came out for two months in a successful demand for a 23 shilling minimum weekly wage for unskilled workers, giving them pay parity with their counterparts in nearby Birmingham. This action commenced on 9 May in Wednesbury, at the Old Patent tube works of John Russell & Co. Ltd., and within weeks upwards of 40,000 workers across the Black Country had joined the dispute. Notable figures in the labour movement, including a key proponent of  The 20th century saw a decline in coal mining in the Black Country, with the last colliery in the region –

The 20th century saw a decline in coal mining in the Black Country, with the last colliery in the region –

The history of industry in the Black Country is connected directly to its underlying geology. Much of the region lies upon an exposed coalfield forming the southern part of the South Staffordshire Coalfield where mining has taken place since the Middle Ages. There are, in fact several coal seams, some of which were given names by the miners. The top, thin coal seam is known as ''Broach Coal''. Beneath this lies successively the ''Thick Coal'', ''Heathen Coal'', ''Stinking Coal'', ''Bottom Coal'' and ''Singing Coal'' seams. Other seams also exist. The Thick Coal seam was also known as the "Thirty Foot" or "Ten Yard" seam and is made up of a number of beds that have come together to form one thick seam. Interspersed with the coal seams are deposits of iron ore and

The history of industry in the Black Country is connected directly to its underlying geology. Much of the region lies upon an exposed coalfield forming the southern part of the South Staffordshire Coalfield where mining has taken place since the Middle Ages. There are, in fact several coal seams, some of which were given names by the miners. The top, thin coal seam is known as ''Broach Coal''. Beneath this lies successively the ''Thick Coal'', ''Heathen Coal'', ''Stinking Coal'', ''Bottom Coal'' and ''Singing Coal'' seams. Other seams also exist. The Thick Coal seam was also known as the "Thirty Foot" or "Ten Yard" seam and is made up of a number of beds that have come together to form one thick seam. Interspersed with the coal seams are deposits of iron ore and

In recent years the Black Country has seen the adoption of symbols and emblems with which to represent itself. The first of these to be registered was the Black Country

In recent years the Black Country has seen the adoption of symbols and emblems with which to represent itself. The first of these to be registered was the Black Country

Black Country Slang

The best collection of Black Country dialect and slang words — if yow cor spake owr bostin language now yow con!

Series of four films about the history and life of the Black Country *

BBC Black Country

BBC website for Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton

Black Country History

Catalogue of Museums and Archives in the Black Country

Black Country Living Museum Website

Black Country Society

The Black Country Alphabet

{{Authority control Areas of the West Midlands (county) Coal mining regions in England History of the West Midlands (county)

West Midlands

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

county, England covering most of the Metropolitan Boroughs of Dudley

Dudley is a large market town and administrative centre in the county of West Midlands, England, southeast of Wolverhampton and northwest of Birmingham. Historically an exclave of Worcestershire, the town is the administrative centre of the ...

, Sandwell and Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands County, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east of Wolverhampton and from Lichfield.

Walsall is th ...

. Dudley

Dudley is a large market town and administrative centre in the county of West Midlands, England, southeast of Wolverhampton and northwest of Birmingham. Historically an exclave of Worcestershire, the town is the administrative centre of the ...

and Tipton

Tipton is an industrial town in the West Midlands in England with a population of around 38,777 at the 2011 UK Census. It is located northwest of Birmingham.

Tipton was once one of the most heavily industrialised towns in the Black Country, w ...

are generally considered to be the centre. It became industrialised during its role as one of the birth places of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

across the English Midlands with coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

mines, coking, iron foundries

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

, glass factories, brickworks

A brickworks, also known as a brick factory, is a factory for the manufacturing of bricks, from clay or shale. Usually a brickworks is located on a clay bedrock (the most common material from which bricks are made), often with a quarry for ...

and steel mills, producing a high level of air pollution.

The name dates from the 1840s, and is believed to come from the soot that the heavy industries covered the area in, although the 30-foot-thick coal seam close to the surface is another possible origin.

The road between Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunians ...

and Birmingham was described as "one continuous town" in 1785.

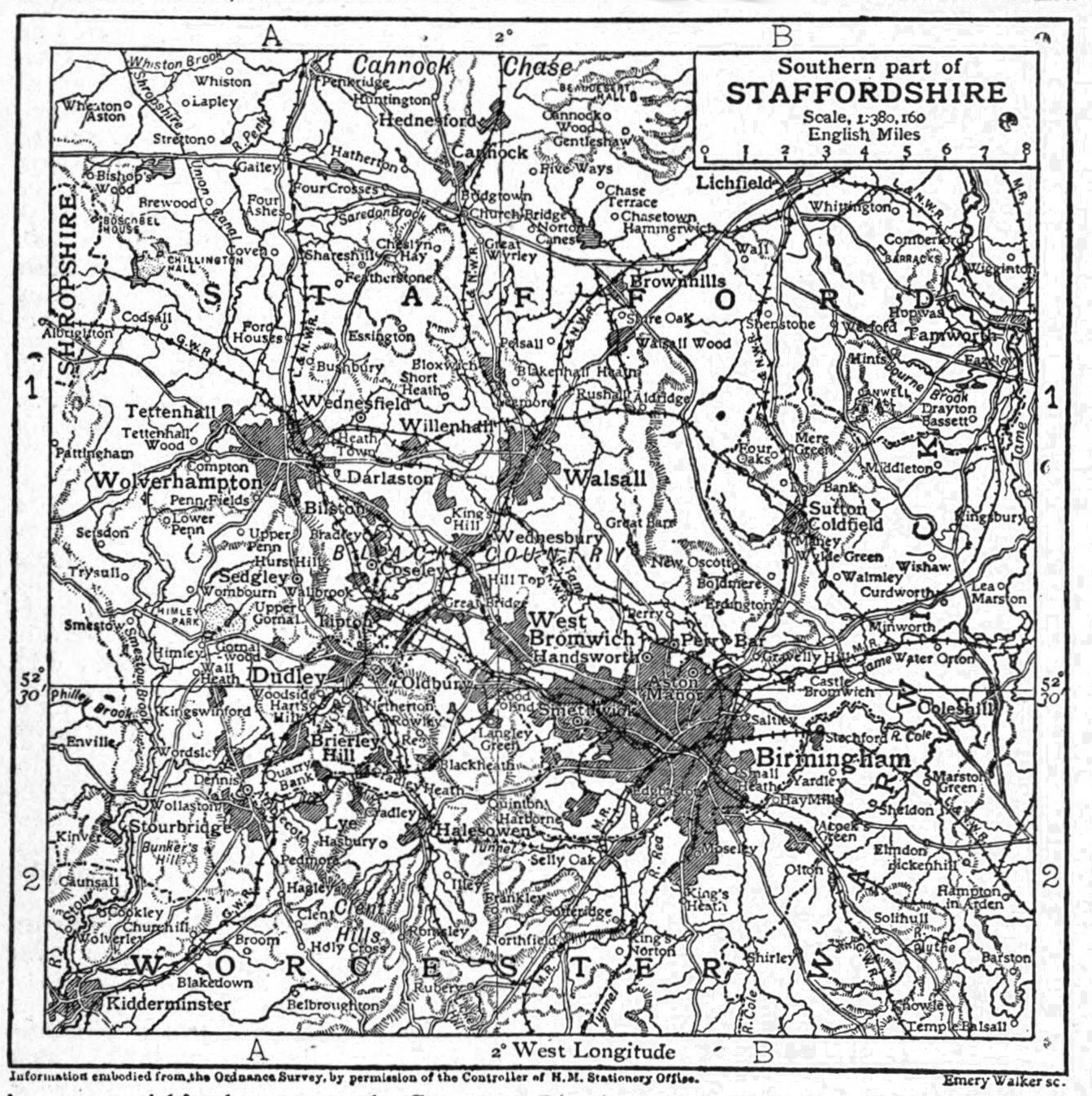

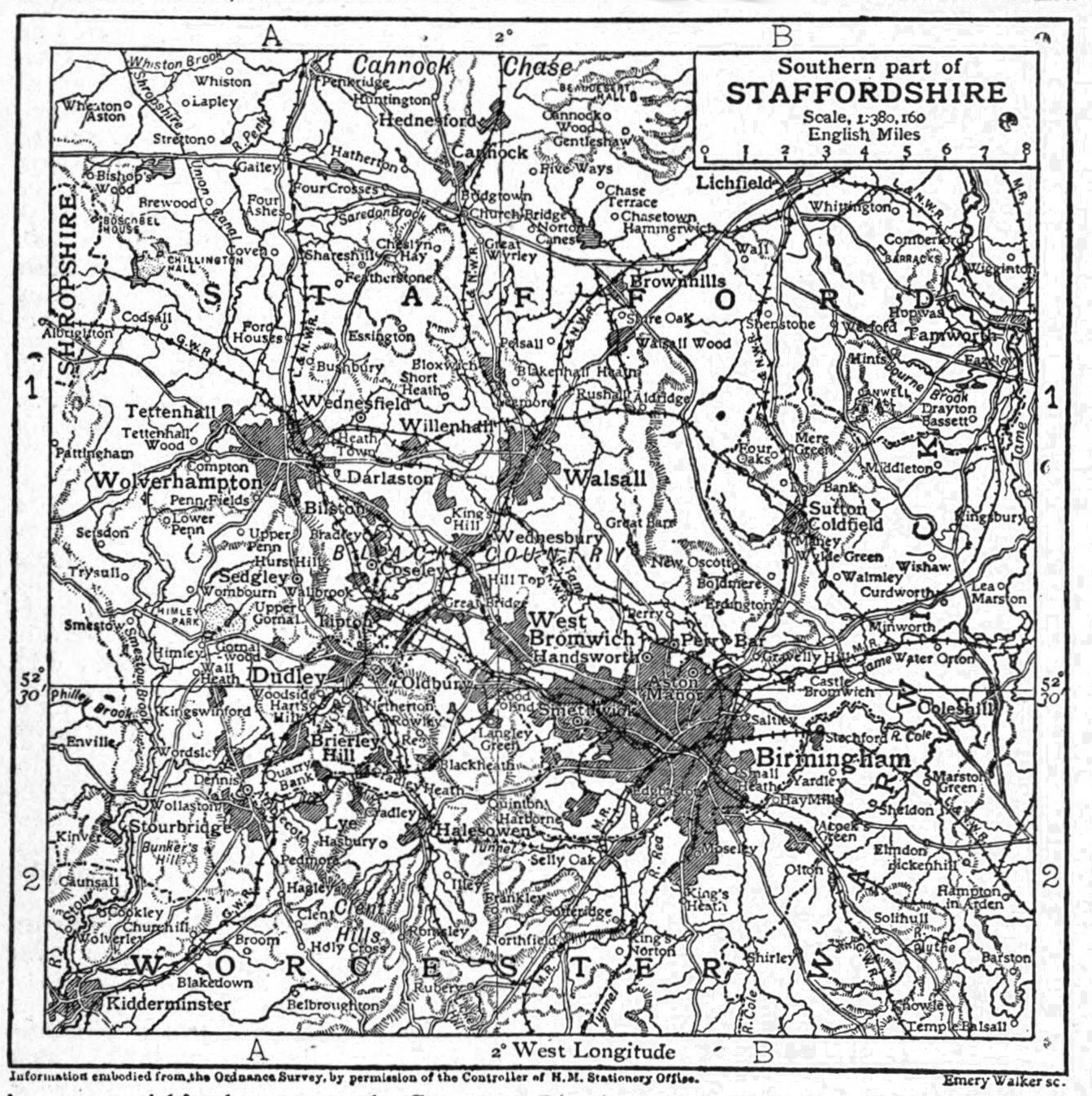

Extent

The Black Country has no single set of defined boundaries. Some traditionalists define it as "the area where the coal seam comes to the surface – so

The Black Country has no single set of defined boundaries. Some traditionalists define it as "the area where the coal seam comes to the surface – so West Bromwich

West Bromwich ( ) is a market town in the borough of Sandwell, West Midlands, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, it is north-west of Birmingham. West Bromwich is part of the area known as the Black Country, in terms of geography, c ...

, Coseley

Coseley ( ) is a village in the north of the Dudley Metropolitan Borough, in the English West Midlands. Part of the Black Country, it is situated approximately north of Dudley itself, on the border with Wolverhampton. Though it is a part o ...

, Oldbury, Blackheath, Cradley Heath

Cradley Heath is a town in the Rowley Regis area of the Metropolitan Borough of Sandwell, West Midlands, England approximately north-west of Halesowen, south of Dudley and west of central Birmingham. Cradley Heath is often confused with t ...

, Old Hill

Old Hill is a small village in the metropolitan borough of Sandwell in the West Midlands, England, situated around north of Halesowen and south of Dudley. Initially a separate village it is now part of the much larger West Midlands conurba ...

, Bilston

Bilston is a market town, ward, and civil parish located in Wolverhampton, West Midlands, England. It is close to the borders of Sandwell and Walsall. The nearest towns are Darlaston, Wednesbury, and Willenhall. Historically in Staffordshi ...

, Dudley

Dudley is a large market town and administrative centre in the county of West Midlands, England, southeast of Wolverhampton and northwest of Birmingham. Historically an exclave of Worcestershire, the town is the administrative centre of the ...

, Tipton

Tipton is an industrial town in the West Midlands in England with a population of around 38,777 at the 2011 UK Census. It is located northwest of Birmingham.

Tipton was once one of the most heavily industrialised towns in the Black Country, w ...

, Wednesbury

Wednesbury () is a market town in Sandwell in the county of West Midlands, England. It is located near the source of the River Tame. Historically part of Staffordshire in the Hundred of Offlow, at the 2011 Census the town had a population of 3 ...

, and parts of Halesowen

Halesowen ( ) is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley, in the county of West Midlands, England.

Historically an exclave of Shropshire and, from 1844, in Worcestershire, the town is around from Birmingham city centre, and fro ...

, Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands County, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east of Wolverhampton and from Lichfield.

Walsall is th ...

, Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunians ...

, Stourbridge

Stourbridge is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley in the West Midlands, England, situated on the River Stour. Historically in Worcestershire, it was the centre of British glass making during the Industrial Revolution. The ...

, and Smethwick or what used to be known as Warley". There are records from the 18th century of shallow coal mines in Wolverhampton, however. Others have included areas slightly outside the coal field which were associated with heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

.

Bilston-born Samuel Griffiths, in his 1876 ''Griffiths Guide to the Iron Trade of Great Britain'', stated "The Black Country commences at Wolverhampton, extends a distance of sixteen miles to Stourbridge, eight miles to West Bromwich, penetrating the northern districts through Willenhall to Bentley, The Birchills, Walsall and Darlaston, Wednesbury, Smethwick and Dudley Port, West Bromwich and Hill Top, Brockmoor, Wordsley and Stourbridge. As the atmosphere becomes purer, we get to the higher ground of Brierley Hill, nevertheless here also, as far as the eye can reach, on all sides, tall chimneys vomit forth great clouds of smoke".

Today the term commonly refers to the majority of the four metropolitan boroughs

A metropolitan borough (or metropolitan district) is a type of local government district in England. Created in 1974 by the Local Government Act 1972, metropolitan boroughs are defined in English law as metropolitan districts within metropolit ...

of Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton () is a city, metropolitan borough and administrative centre in the West Midlands, England. The population size has increased by 5.7%, from around 249,500 in 2011 to 263,700 in 2021. People from the city are called "Wulfrunians ...

although it is said that "no two Black Country men or women will agree on where it starts or ends".

Local government

Official use of the name came in 1987 with the

Official use of the name came in 1987 with the Black Country Development Corporation

The Black Country Development Corporation was an urban development corporation established in May 1987 to develop land in the Metropolitan Boroughs of Sandwell and Walsall in England.

Its flagship developments included the Black Country Spine R ...

, an urban development corporation

Empire State Development (ESD) is the umbrella organization for New York's two principal economic development public-benefit corporations, the New York State Urban Development Corporation (UDC) and the New York Job Development Authority (JDA). T ...

covering the metropolitan boroughs

A metropolitan borough (or metropolitan district) is a type of local government district in England. Created in 1974 by the Local Government Act 1972, metropolitan boroughs are defined in English law as metropolitan districts within metropolit ...

of Sandwell and Walsall, which was disbanded in 1998. The Black Country Consortium (founded in 1999) and the Black Country Local Enterprise Partnership

In England, local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) are voluntary partnerships between Local government in England, local authorities and businesses, set up in 2011 by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills to help determine local econom ...

(founded in 2011) both define the Black Country as the four metropolitan boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton, an approximate area of .

Cultural and industrial definition

The borders of the Black Country can be defined by using the special cultural and industrial characteristics of the area. Areas around the canals (the cut) which had mines extracting mineral resources and heavy industry refining these are included in this definition. Cultural parameters include unique or characteristic foods such asgroaty pudding

Groaty pudding (also known as groaty dick) is a traditional dish from the Black Country in England. It is made from soaked groats, beef, leeks, onion and beef stock which are baked together at a moderate temperature of approximately for up to ...

, grey peas and bacon, faggots, gammon or pork hocks and pork scratchings; Black Country humour; and the Black Country dialect.

Geological definitions

The Black Country Society defines the Black Country's borders as the area on the thirty foot coal seam, regardless the depth of the seam. This definition includes West Bromwich and Oldbury, which had many deep pits, and Smethwick. The thick coal that underlies Smethwick was not mined until the 1870s and Smethwick has retained more Victorian character than most West Midland areas. Sandwell Park Colliery's pit was located in Smethwick and had 'thick coal' as shown in written accounts from 1878 and coal was also heavily mined in Hamstead, further east, whose workings extended well under what is now northBirmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

. Smethwick and Dudley Port were described as "a thousand swarming hives of metallurgical industries" by Samuel Griffiths in 1872.

Another geological definition, the seam outcrop definition, only includes areas where the coal seam is shallow, making the soil black at the surface. Some coal mining areas to the east and west of the geologically defined Black Country are therefore excluded by this definition because the coal here is too deep down and does not outcrop. The seam outcrop definition excludes areas in North Worcestershire and South Staffordshire.

Toponymy

The first recorded use of the term "the Black Country" may be from a toast given by a Mr Simpson, town clerk toLichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west o ...

, addressing a Reformer's meeting on 24 November 1841, published in the ''Staffordshire Advertiser''. He describes going into the "black country" of Staffordshire – Wolverhampton, Bilston and Tipton.

In published literature, the first reference dates from 1846 and occurs in the novel ''Colton Green: A Tale of the Black Country'' by the Reverend William Gresley, who was then a prebendary

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of th ...

of Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England, one of only three cathedrals in the United Kingdom with three spires (together with Truro Cathedral and St Mary's Cathedral in Edinburgh), and the only medie ...

. Gresley's opening paragraph starts "On the border of the agricultural part of Staffordshire, just before you enter the dismal region of mines and forges, commonly called the 'Black Country', stands the pretty village of Oakthorpe", "commonly" implying that the term was already in use. He also writes that "the whole country is blackened with smoke by day, and glowing with fires by night", and that "the 'Black Country' ... is about twenty miles in length and five in bredth reaching from north to south".

The phrase was used again, though as a description rather than a proper noun

A proper noun is a noun that identifies a single entity and is used to refer to that entity (''Africa'', ''Jupiter'', '' Sarah'', ''Microsoft)'' as distinguished from a common noun, which is a noun that refers to a class of entities (''continent, ...

, by the ''Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication i ...

'' in an 1849 article on the opening of the South Staffordshire Railway

The South Staffordshire Railway (SSR) was authorised in 1847 to build a line from Dudley in the West Midlands of England through Walsall and Lichfield to a junction with the Midland Railway on the way to Burton upon Trent, with authorised share ...

. An 1851 guidebook to the London and North Western Railway included an entire chapter entitled "The Black Country", including an early description:

This work was also the first to explicitly distinguish the area from nearby Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

, noting that "On certain rare holidays these people wash their faces, clothe themselves in decent garments, and, since the opening of the South Staffordshire Railway, take advantage of cheap excursion trains, go down to Birmingham to amuse themselves and make purchases."

The geologist Joseph Jukes

Joseph Beete Jukes (10 October 1811 – 29 July 1869), born to John and Sophia Jukes at Summer Hill, Birmingham, England, was a renowned geologist, author of several geological manuals and served as a naturalist on the expeditions of (under th ...

made it clear in 1858 that he felt the meaning of the term was self-explanatory to contemporary visitors, remarking that "It is commonly known in the neighbourhood as the 'Black Country', an epithet the appropriateness of which must be acknowledged by anyone who even passes through it on a railway". Jukes based his Black Country on the seat of the great iron manufacture, which for him was geographically determined by the ironstone tract of the coalfield rather than the thick seam, running from Wolverhampton to Bloxwich, to West Bromwich, to Stourbridge and back to Wolverhampton again. A travelogue published in 1860 made the connection more explicit, calling the name "eminently descriptive, for blackness everywhere prevails; the ground is black, the atmosphere is black, and the underground is honeycombed by mining galleries stretching in utter blackness for many a league". An alternative theory for the meaning of the name is proposed as having been caused by the darkening of the local soil due to the outcropping coal and the seam near the surface.

It was however the American diplomat and travel writer Elihu Burritt

Elihu Burritt (December 8, 1810March 6, 1879) was an American diplomat, philanthropist and social activist.Arthur Weinberg and Lila Shaffer Weinberg. ''Instead of Violence: Writings by the Great Advocates of Peace and Nonviolence Throughout Histo ...

who brought the term "the Black Country" into widespread common usage with the third, longest and most important of the travel books he wrote about Britain for American readers, his 1868 work ''Walks in The Black Country and its Green Borderland''. Burritt had been appointed United States consul in Birmingham by Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

in 1864, a role that required him to report regularly on "facts bearing upon the productive capacities, industrial character and natural resources of communities embraced in their Consulate Districts" and as a result travelled widely from his home in Harborne

Harborne is an area of south-west Birmingham, England. It is one of the most affluent areas of the Midlands, southwest from Birmingham city centre. It is a Birmingham City Council ward in the formal district and in the parliamentary constitu ...

, largely on foot, to explore the local area. Burritt's association with Birmingham dated back 20 years and he was highly sympathetic to the industrial and political culture of the town as well as being a friend many of its leading citizens, so his portrait of the surrounding area was largely positive. He was the author of the famous early description of the Black Country as "black by day and red by night", adding appreciatively that it "cannot be matched, for vast and varied production, by any other space of equal radius on the surface of the globe". Burritt used the term to refer to a wider area than its common modern usage, however, devoting the first third of the book to Birmingham, which he described as "the capital, manufacturing centre, and growth of the Black Country", and writing "plant, in imagination, one foot of your compass at the Town Hall in Birmingham, and with the other sweep a circle of twenty miles 0 kmradius, and you will have, 'the Black Country" (this area includes Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, Kidderminster

Kidderminster is a large market and historic minster town and civil parish in Worcestershire, England, south-west of Birmingham and north of Worcester. Located north of the River Stour and east of the River Severn, in the 2011 census, it ha ...

and Lichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west o ...

).

History

Domesday Book

Domesday Book () – the Middle English spelling of "Doomsday Book" – is a manuscript record of the "Great Survey" of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086 by order of King William I, known as William the Conqueror. The manus ...

of 1086. At this early date, the area was mostly rural. A monastery was founded in Wolverhampton in the Anglo-Saxon period and a castle and priory was built at Dudley during the period of Norman rule. Another religious house, Premonstratensian Abbey of Halesowen, was founded in the early 13th century. A number of Black Country villages developed into market towns and boroughs in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, notably Dudley, Walsall and Wolverhampton. Coal mining was carried out for several centuries in the Black Country, starting from medieval times, and metalworking was important in the Black Country area as early as the 16th century spurred on by the presence of iron ore and coal in a seam thick, the thickest seam in Great Britain, which outcropped in various places. The first blast furnace recorded in the Black Country was built at West Bromwich in the early 1560s. Many people had an agricultural smallholding

A smallholding or smallholder is a small farm operating under a small-scale agriculture model. Definitions vary widely for what constitutes a smallholder or small-scale farm, including factors such as size, food production technique or technology ...

and supplemented their income by working as nailers or smiths, an example of a phenomenon known to economic historians as proto-industrialisation

Proto-industrialization is the regional development, alongside commercial agriculture, of rural handicraft production for external markets.

The term was introduced in the early 1970s by economic historians who argued that such developments in pa ...

. In 1583, the accounts of the building of Henry VIII's Nonsuch Palace

Nonsuch Palace was a Tudor royal palace, built by Henry VIII in Surrey, England; it stood from 1538 to 1682–83. Its site lies in what is now Nonsuch Park on the boundaries of the borough of Epsom and Ewell in Surrey and the London Boro ...

record that nails were supplied by Reynolde Warde of Dudley at a cost of 11s 4d per thousand. By the 1620s "Within ten miles 6 kmof Dudley Castle there were 20,000 smiths of all sorts".

In the early 17th century, Dud Dudley

Dudd (Dud) Dudley (1600–1684) was an English metallurgist, who fought on the Royalist side in the English Civil War as a soldier, military engineer, and supplier of munitions. He was one of the first Englishmen to smelt iron ore using coke.

B ...

, a natural son of the Baron of Dudley, experimented with making iron using coal rather than charcoal. Two patents were granted for the process: one in 1621 to Lord Dudley and one in 1638 to Dud Dudley and three others. In his work ''Metallum Martis

''Metallum Martis'', a 1665 book by Dud Dudley, is the earliest known reference to the use of coal in metallurgical smelting. The book is also referred to as ''Iron made with Pit-Coale, Sea-Coale, &c. And with the same Fuell to Melt and Fine Imper ...

'', published in 1665, he claimed to have "made Iron to profit with Pit-cole". However, considerable doubt has been cast on this claim by later writers.

An important development in the early 17th century was the introduction of the slitting mill

The slitting mill was a watermill for slitting bars of iron into rods. The rods then were passed to nailers who made the rods into nails, by giving them a point and head.

The slitting mill was probably invented near Liège in what is now Bel ...

to the Midlands area. In the Black Country, the establishment of this device was associated with Richard Foley, son of a Dudley nailer, who built a slitting mill near Kinver

Kinver is a large village in the District of South Staffordshire in Staffordshire, England. It is in the far south-west of the county, at the end of the narrow finger of land surrounded by the counties of Shropshire, Worcestershire and the ...

in 1628. The slitting mill made it much simpler to produce nail rods from iron bar.

Another development of the early 17th century was the introduction of glass making to the Stourbridge area. One attraction of the region for glass makers was the local deposits of fireclay, a material suitable for making the pots in which glass was melted.

In 1642 at the start of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

failed to capture the two arsenals of Portsmouth and Hull, which although in cities loyal to Parliament were located in counties loyal to him. As he had failed to capture the arsenals, Charles did not possess any supply of swords, pikes, guns, or shot; all these the Black Country could and did provide. From Stourbridge

Stourbridge is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley in the West Midlands, England, situated on the River Stour. Historically in Worcestershire, it was the centre of British glass making during the Industrial Revolution. The ...

came shot, from Dudley

Dudley is a large market town and administrative centre in the county of West Midlands, England, southeast of Wolverhampton and northwest of Birmingham. Historically an exclave of Worcestershire, the town is the administrative centre of the ...

cannon. Numerous small forges which then existed on every brook in the north of Worcestershire turned out successive supplies of sword blades and pike heads. It was said that among the many causes of anger Charles had against Birmingham was that one of the best sword makers of the day, Robert Porter, who manufactured swords in Digbeth, Birmingham, refused at any price to supply swords for " that man of blood" (A Puritan nickname for King Charles), or any of his adherents. As an offset to this sword-cutler and men like him in Birmingham, the Royalists had among their adherents Dud Dudley, now a Colonel in the Royalist army, who had experience in iron making, and who claimed he could turn out "all sorts of bar iron fit for making of muskets, carbines, and iron for great bolts", both more cheaply, more speedily and more excellent than could be done in any other way.

In 1712, a Newcomen Engine

The atmospheric engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and is often referred to as the Newcomen fire engine (see below) or simply as a Newcomen engine. The engine was operated by condensing steam drawn into the cylinder, thereby creati ...

was constructed near Dudley and used to pump water from coal mines belonging to Lord Dudley. This is the earliest documented working steam engine.

An important milestone in the establishment of Black Country industry came when John Wilkinson set up an iron works at Bradley

Bradley is an English surname derived from a place name meaning "broad wood" or "broad meadow" in Old English.

Like many English surnames Bradley can also be used as a given name and as such has become popular.

It is also an Anglicisation of t ...

near Bilston. In 1757 he started making iron there by coke-smelting rather than using charcoal. His example was followed by others and iron making spread rapidly across the Black Country. Another important development of the 18th century was the construction of canals to link the Black Country mines industries to the rest of the country. Between 1768 and 1772 a canal was constructed by James Brindley

James Brindley (1716 – 27 September 1772) was an English engineer. He was born in Tunstead, Derbyshire, and lived much of his life in Leek, Staffordshire, becoming one of the most notable engineers of the 18th century.

Early life

Born i ...

starting in Birmingham through the heart of the Black Country and eventually leading to the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal.

In the middle of the 18th century, Bilston became well known for the craft of

In the middle of the 18th century, Bilston became well known for the craft of enamelling

Vitreous enamel, also called porcelain enamel, is a material made by melting, fusing powdered glass to a substrate by firing, usually between . The powder melts, flows, and then hardens to a smooth, durable vitrification, vitreous coating. The wo ...

. Items produced included decorative containers such as patch-boxes, snuff boxes and bonbonnieres.

The iron industry grew during the 19th century, peaking around 1850–1860. In 1863, there were 200 blast furnaces in the Black Country, of which 110 were in blast. Two years later it was recorded that there were 2,116 puddling furnaces, which converted pig-iron into wrought iron, in the Black Country. In 1864 the first Black Country plant capable of producing mild steel by the Bessemer process was constructed at the Old Park Works in Wednesbury. In 1882, another Bessemer-style steel works was constructed at Spring Vale in Bilston by the Staffordshire Steel and Ingot Iron Company, a development followed by the construction of an open-hearth steelworks at the Round Oak works of the Earl of Dudley in Brierley Hill, which produced its first steel in 1894.

By the 19th century or early 20th century, many villages had their characteristic manufacture, but earlier occupations were less concentrated. Some of these concentrations are less ancient than sometimes supposed. For example, chain making in Cradley Heath seems only to have begun in about the 1820s, and the Lye

A lye is a metal hydroxide traditionally obtained by leaching wood ashes, or a strong alkali which is highly soluble in water producing caustic basic solutions. "Lye" most commonly refers to sodium hydroxide (NaOH), but historically has been u ...

holloware

Holloware (hollowware, or hollow-ware ) is metal tableware such as sugar bowls, creamers, coffee pots, teapots, soup tureens, hot food covers, water jugs, platters, butter pat plates, and other items that accompany dishware on a table. It d ...

industry is even more recent.

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, coal and limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

were worked only on a modest scale for local consumption, but during the Industrial Revolution by the opening of canals, such as the Birmingham Canal Navigations

Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) is a network of canals connecting Birmingham, Wolverhampton, and the eastern part of the Black Country. The BCN is connected to the rest of the English canal system at several junctions. It was owned and opera ...

, Stourbridge Canal and the Dudley Canal

The Dudley Canal is a canal passing through Dudley in the West Midlands of England. The canal is part of the English and Welsh connected network of navigable inland waterways, and in particular forms part of the popular Stourport Ring narrowboat ...

(the Dudley Canal Line No 1 and the Dudley Tunnel

Dudley Tunnel is a canal tunnel on the Dudley Canal Line No 1, England. At about long, it is now the second longest canal tunnel on the UK canal network today. ( Standedge Tunnel is the longest, at , and the Higham and Strood tunnel is now ...

) opened up the mineral wealth of the area to exploitation. Advances in the use of coke for the production of iron enabled iron production (hitherto limited by the supply of charcoal) to expand rapidly.

By Victorian times, the Black Country was one of the most heavily industrialised areas in Britain, and it became known for its pollution, particularly from iron and coal industries and their many associated smaller businesses. This led to the expansion of local railways and coal mine lines. The line running from Stourbridge to Walsall via Dudley Port

Dudley is a large market town and administrative centre in the county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England, southeast of Wolverhampton and northwest of Birmingham. Historically an Enclave and exclave, exclave of Worcestershire, t ...

and Wednesbury

Wednesbury () is a market town in Sandwell in the county of West Midlands, England. It is located near the source of the River Tame. Historically part of Staffordshire in the Hundred of Offlow, at the 2011 Census the town had a population of 3 ...

closed in the 1960s, but the Birmingham to Wolverhampton line via Tipton is still a major transport route.

The anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal , used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ''ancora'', which itself comes from the Greek ἄ� ...

s and chains for the ill-fated liner RMS ''Titanic'' were manufactured in the Black Country in the area of Netherton. Three anchors and accompanying chains were manufactured; and the set weighed in at 100 ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s. The centre anchor alone weighed 12 tons and was pulled through Netherton on its journey to the ship by 20 Shire horse

The Shire is a British breed of draught horse. It is usually black, bay, or grey. It is a tall breed, and Shires have at various times held world records both for the largest horse and for the tallest horse. The Shire has a great capacity for ...

s.

In 1913, the Black Country was the location of arguably one of the most important strikes in British trade union history when the workers employed in the area's steel tube trade came out for two months in a successful demand for a 23 shilling minimum weekly wage for unskilled workers, giving them pay parity with their counterparts in nearby Birmingham. This action commenced on 9 May in Wednesbury, at the Old Patent tube works of John Russell & Co. Ltd., and within weeks upwards of 40,000 workers across the Black Country had joined the dispute. Notable figures in the labour movement, including a key proponent of

In 1913, the Black Country was the location of arguably one of the most important strikes in British trade union history when the workers employed in the area's steel tube trade came out for two months in a successful demand for a 23 shilling minimum weekly wage for unskilled workers, giving them pay parity with their counterparts in nearby Birmingham. This action commenced on 9 May in Wednesbury, at the Old Patent tube works of John Russell & Co. Ltd., and within weeks upwards of 40,000 workers across the Black Country had joined the dispute. Notable figures in the labour movement, including a key proponent of Syndicalism

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of prod ...

, Tom Mann

Thomas Mann (15 April 1856 – 13 March 1941), was an English trade unionist and is widely recognised as a leading, pioneering figure for the early labour movement in Britain. Largely self-educated, Mann became a successful organiser and a ...

, visited the area to support the workers and Jack Beard and Julia Varley

Julia Varley, OBE (16 March 1871, Bradford, Yorkshire – 24 November 1952, Yorkshire) was an English trade unionist and suffragette.

Early life

Born at 4, Monk Street in Horton in Bradford, she was one of seven surviving children out of nine ...

of the Workers' Union were active in organising the strike. During this confrontation with employers represented by the Midlands Employers' Federation, a body founded by Dudley Docker

Frank Dudley Docker (26 August 1862 – 8 July 1944) was an English businessman and financier. He also played first-class cricket for Derbyshire in 1881 and 1882.

Biography

Family background, early life and education

Docker was born at Paxt ...

, the Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of ...

Government's armaments programme was jeopardised, especially its procurement of naval equipment and other industrial essentials such as steel tubing, nuts and bolts, destroyer parts, etc. This was of national significance at a time when Britain and Germany were engaged in the Anglo-German naval arms race

The arms race between Great Britain and Germany that occurred from the last decade of the nineteenth century until the advent of World War I in 1914 was one of the intertwined causes of that conflict. While based in a bilateral relationship tha ...

that preceded the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Following a ballot of the union membership, a settlement of the dispute was reached on 11 July after arbitration by government officials from the Board of Trade led by the Chief Industrial Commissioner Sir George Askwith, 1st Baron Askwith. One of the important consequences of the strike was the growth of organised labour across the Black Country, which was notable because until this point the area's workforce had effectively eschewed trade unionism.

The 20th century saw a decline in coal mining in the Black Country, with the last colliery in the region –

The 20th century saw a decline in coal mining in the Black Country, with the last colliery in the region – Baggeridge Colliery

Baggeridge Colliery was a colliery located in Sedgley, West Midlands England.

Colliery History

The Baggeridge Colliery was an enterprise of the Earls of Dudley, whose ancestors had profited from mineral extraction in the Black Country area of ...

near Sedgley

Sedgley is a town in the north of the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley, in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England.

Historic counties of England, Historically part of Staffordshire, Sedgley is on the A459 road between Wolverhampt ...

– closing on 2 March 1968, marking the end of an era after some 300 years of mass coal mining in the region, though a small number of open cast mines remained in use for a few years afterwards.

As the heavy industry that had named the region faded away, in the 1970s a museum, called the Black Country Living Museum

The Black Country Living Museum (formerly the Black Country Museum) is an open-air museum of rebuilt historic buildings in Dudley, West Midlands, England.

started to take shape on derelict land near to Dudley. Today this museum demonstrates Black Country crafts and industry from days gone by and includes many original buildings which have been transported and reconstructed at the site.

Geology and landscape

The history of industry in the Black Country is connected directly to its underlying geology. Much of the region lies upon an exposed coalfield forming the southern part of the South Staffordshire Coalfield where mining has taken place since the Middle Ages. There are, in fact several coal seams, some of which were given names by the miners. The top, thin coal seam is known as ''Broach Coal''. Beneath this lies successively the ''Thick Coal'', ''Heathen Coal'', ''Stinking Coal'', ''Bottom Coal'' and ''Singing Coal'' seams. Other seams also exist. The Thick Coal seam was also known as the "Thirty Foot" or "Ten Yard" seam and is made up of a number of beds that have come together to form one thick seam. Interspersed with the coal seams are deposits of iron ore and

The history of industry in the Black Country is connected directly to its underlying geology. Much of the region lies upon an exposed coalfield forming the southern part of the South Staffordshire Coalfield where mining has taken place since the Middle Ages. There are, in fact several coal seams, some of which were given names by the miners. The top, thin coal seam is known as ''Broach Coal''. Beneath this lies successively the ''Thick Coal'', ''Heathen Coal'', ''Stinking Coal'', ''Bottom Coal'' and ''Singing Coal'' seams. Other seams also exist. The Thick Coal seam was also known as the "Thirty Foot" or "Ten Yard" seam and is made up of a number of beds that have come together to form one thick seam. Interspersed with the coal seams are deposits of iron ore and fireclay

Fire clay is a range of refractory clays used in the manufacture of ceramics, especially fire brick. The United States Environmental Protection Agency defines fire clay very generally as a "mineral aggregate composed of hydrous silicates of alumin ...

. The Black Country coal field is bounded on the north by the Bentley Fault, to the north of which lies the Cannock Chase Coalfield. Around the exposed coalfield, separated by geological faults, lies a concealed coalfield where the coal lies at much greater depth. A mine was sunk between 1870 and 1874 over the eastern boundary of the then known coal field in Smethwick and coal was discovered at a depth of over 400 yards. In the last decade of the 19th century, coal was discovered beyond the western boundary fault at Baggeridge at a depth of around 600 yards.

A broken ridge runs across the Black Country in a north-westerly direction through Dudley, Wrens Nest and Sedgley, separating the Black Country into two regions. This ridge forms part of a major watershed of England with streams to the north taking water to the Tame

Tame may refer to:

*Taming, the act of training wild animals

*River Tame, Greater Manchester

*River Tame, West Midlands and the Tame Valley

* Tame, Arauca, a Colombian town and municipality

* "Tame" (song), a song by the Pixies from their 1989 al ...

and then via the Trent

Trent may refer to:

Places Italy

* Trento in northern Italy, site of the Council of Trent United Kingdom

* Trent, Dorset, England, United Kingdom Germany

* Trent, Germany, a municipality on the island of Rügen United States

* Trent, California, ...

into the North Sea whilst to the south of the ridge, water flows into the Stour and thence to the Severn and the Bristol Channel.

At Dudley and Wrens Nest, limestone was mined. This rock formation was formed in the Silurian period and contains many fossils. One particular fossilized creature, the trilobite ''Calymene blumenbachii

''Calymene blumenbachii'' Brongniart ''in'' Desmarest (1817),Desmarest, A. G. 1817. Calymène. in: ''Nouveau Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle, Nouvelle Edition'', Tome 8, pp. 517 - 518. sometimes erroneously spelled ''blumenbachi'', is a spe ...

'', was so common that it became known as the "Dudley Bug" or "Dudley Locust" and was incorporated into the coat-of-arms of the County Borough of Dudley.

At a number of places, notably the Rowley Hills and at Barrow Hill, a hard igneous rock is found. The rock, known as dolerite, used to be quarried and used for road construction.

Symbols

tartan

Tartan ( gd, breacan ) is a patterned cloth consisting of criss-crossed, horizontal and vertical bands in multiple colours. Tartans originated in woven wool, but now they are made in other materials. Tartan is particularly associated with Sc ...

in 2009, designed by Philip Tibbetts from Halesowen.

In 2008 the idea of a flag for the region was first raised. After four years of campaigning a competition was successfully organised with the Black Country Living Museum

The Black Country Living Museum (formerly the Black Country Museum) is an open-air museum of rebuilt historic buildings in Dudley, West Midlands, England.

. This resulted in the adoption of the Flag of the Black Country as designed by Gracie Sheppard of Redhill School in Stourbridge and was registered with the Flag Institute

The Flag Institute is a UK membership organisation headquartered in Kingston upon Hull, England, concerned with researching and promoting the use and design of flags. It documents flags in the UK and internationally, maintains a UK Flag Regi ...

in July 2012.

The flag was unveiled at the museum on 14 July 2012 as part of celebration in honour of the 300th anniversary of the erection of the first Newcomen atmospheric engine

The atmospheric engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and is often referred to as the Newcomen fire engine (see below) or simply as a Newcomen engine. The engine was operated by condensing steam drawn into the cylinder, thereby creati ...

. Following this it was agreed by the museum and Black Country society for 14 July to be recognised as Black Country Day to celebrate the area's role in the Industrial Revolution. The day was marked by Department for Communities and Local Government

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC), formerly the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for housing, communities, local governme ...

in 2013 and following calls to do more in 2014 more events were planned around the region.

Black Country Day takes place on 14 July each year. Originally in March, the day was later moved to 14 July—the anniversary of the invention of the Newcomen steam engine—and now coincides with a wider series of events throughout the month aimed at promoting Black Country Culture called the Black Country Festival.

The Black Country Anthem was written by James Stevens and is performed by Black Country band The Empty Can. The idea for the anthem was raised in 2013 by James Stevens and Steven Edwards who wanted the region to have an official anthem to accompany the Black Country flag & Black Country Day.

Economy

The heavy industry which once dominated the Black Country has now largely gone. The 20th century saw a decline in coal mining and the industry finally came to an end in 1968 with the closure of Baggeridge Colliery nearSedgley

Sedgley is a town in the north of the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley, in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England.

Historic counties of England, Historically part of Staffordshire, Sedgley is on the A459 road between Wolverhampt ...

. Clean air legislation has meant that the Black Country is no longer black. The area still maintains some manufacturing, but on a much smaller scale than historically. Chainmaking is still a viable industry in the Cradley Heath area where the majority of the chain for the Ministry of Defence and the Admiralty fleet is made in modern factories.

Much but not all of the area now suffers from high unemployment and parts of it are amongst the most economically deprived communities in the UK. This is particularly true in parts of the metropolitan boroughs of Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton. According to the Government's 2007 Index of Deprivation (ID 2007), Sandwell is the third most deprived authority in the West Midlands region, after Birmingham and Stoke-on-Trent, and the 14th most deprived of the UK's 354 districts. Wolverhampton is the fourth most deprived district in the West Midlands, and the 28th most deprived nationally. Walsall is the fifth most deprived district in the West Midlands region, and the 45th most deprived in the country.

Dudley fares better, but still has pockets of deprivation. Overall Dudley is the 100th most deprived district of the UK, but the second most affluent of the seven metropolitan districts of the West Midlands, with Solihull coming top. It also benefits from tourism due to the popularity of the Black Country Living Museum

The Black Country Living Museum (formerly the Black Country Museum) is an open-air museum of rebuilt historic buildings in Dudley, West Midlands, England.

, Dudley Zoo

Dudley Zoological Gardens is a zoo located within the grounds of Dudley Castle in the town of Dudley, in the Black Country region of the West Midlands, England. The Zoo opened to the public on 18 May 1937. It contains 12 modernist animal encl ...

and Dudley Castle

Dudley Castle is a ruined fortification in the town of Dudley, West Midlands, England. Originally a wooden motte and bailey castle built soon after the Norman Conquest, it was rebuilt as a stone fortification during the twelfth century but su ...

.

As with many urban areas in the UK, there is also a significant ethnic minority population in parts: in Sandwell, 22.6 per cent of the population are from ethnic minorities, and in Wolverhampton the figure is 23.5 per cent. However, in Walsall 84.6 per cent of the population is described as white, while in Dudley 92 per cent of the population is white. Resistance to mass immigration in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s led to the slogan "''Keep the Black Country white!''".

The Black Country suffered its biggest economic blows in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when unemployment soared largely because of the closure of historic large factories including the Round Oak Steel Works

The Round Oak Steelworks was a steel production plant in Brierley Hill, West Midlands (formerly Staffordshire), England. It was founded in 1857 by Lord Ward, who later became, in 1860, The 1st Earl of Dudley, as an outlet for pig iron made in t ...

at Brierley Hill

Brierley Hill is a town and electoral ward in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley, West Midlands, England, 2.5 miles south of Dudley and 2 miles north of Stourbridge. Part of the Black Country and in a heavily industrialised area, it has a pop ...

and the Patent Shaft steel plant at Wednesbury. Unemployment rose drastically across the country during this period as a result of Conservative Prime Minister Thatcher's economic policies; later, in an implicit acknowledgement of the social problems this had caused, these areas were designated as Enterprise Zones, and some redevelopment occurred. Round Oak and the surrounding farmland was developed as the Merry Hill Shopping Centre and Waterfront commercial and leisure complex, while the Patent Shaft site was developed as an industrial estate.

Unemployment in Brierley Hill peaked at more than 25% – around double the national average at the time – during the first half of the 1980s following the closure of Round Oak Steel Works, giving it one of the worst unemployment rates of any town in Britain. The Merry Hill development between 1985 and 1990 managed to reduce the local area's unemployment dramatically, however.

The Black Country Living Museum

The Black Country Living Museum (formerly the Black Country Museum) is an open-air museum of rebuilt historic buildings in Dudley, West Midlands, England.

in Dudley recreates life in the Black Country in the early 20th century, and is a popular tourist attraction

A tourist attraction is a place of interest that tourists visit, typically for its inherent or an exhibited natural or cultural value, historical significance, natural or built beauty, offering leisure and amusement.

Types

Places of natural ...

. On 17 February 2012 the museum's collection in its entirety was awarded Designation by Arts Council England (ACE). Designation is a mark of distinction that celebrates unique collections of national and international importance.

The four metropolitan boroughs of the Black Country form part of the Birmingham metropolitan economy, the second largest in the UK.

In 2011, the government announced the creation of the Black Country Enterprise Zone. The zone includes 5 sites in Wolverhampton and 14 in Darlaston

Darlaston is an industrial town in the Metropolitan Borough of Walsall in the West Midlands of England. It is located near Wednesbury and Willenhall.

Topography

Darlaston is situated between Wednesbury and Walsall in the valley of the Riv ...

. The i54 business park in Wolverhampton is the largest of the 19 sites; its tenants include Jaguar Land Rover

Jaguar Land Rover Automotive PLC is the holding company of Jaguar Land Rover Limited (also known as JLR), and is a British multinational automobile manufacturer which produces luxury vehicles and sport utility vehicles. Jaguar Land Rover is a ...

. The largest site in Darlaston is that of the former IMI James Bridge Copper Works.

The four boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, Wolverhampton and Walsall submitted a joint bid in late 2015 to become a UNESCO Global Geopark

UNESCO Global Geoparks (UGGp) are geoparks certified by the UNESCO Global Geoparks Council as meeting all the requirements for belonging to the Global Geoparks Network (GGN). The GGN is both a network of geoparks and the agency of the United Nati ...

. The Geopark would increase the area's prospects as a tourism destination thereby supporting the local economy. To this end numerous 'geosites' were subsequently identified, leaflets published and public events organised. As of 2017, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

had given the aspirant geopark its initial backing pending further assessment. Confirmation of the Black Country as a UNESCO Global Geopark was announced on 10 July 2020.

Dialect and accent

The traditional Black Country dialect, known as "Black Country Spake" (as in "Where's our Spake Gone", a 2014–2016 lottery-funded project to preserve and document the dialect) preserves many archaic traits ofEarly Modern English

Early Modern English or Early New English (sometimes abbreviated EModE, EMnE, or ENE) is the stage of the English language from the beginning of the Tudor period to the English Interregnum and Restoration, or from the transition from Middle E ...

and even Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English ...

and can be very confusing for outsiders. ''Thee'', ''thy'' and ''thou'' are still in use, as is the case in parts of Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

, Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

and Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancash ...

. The Black Country dialect is well known by many as the oldest form of the English language despite being disputed unsuccessfully on a number of occasions.

"'Ow b'ist," or "Ow b'ist gooin" (How are you/ How are you going), to which typical responses would be "bostin', ah kid" (bostin' means "busting", as in breaking, and is similar in usage to "smashing"; and "ah kid" (our kid) is a term of endearment) or "'bay too bad," or even "bay three bad" ("I be not too bad"/ I'm not too bad).

Ain't

The word "ain't" is a contraction for ''am not'', ''is not'', ''are not'', ''has not'', ''have not'' in the common English language vernacular. In some dialects ''ain't'' is also used as a contraction of ''do not'', ''does not'' and ''did not''. ...

is in common use as when "I haven't seen her" becomes "I ain't sid 'er" .

Black Country dialect often uses "ar" where other parts of England use "yes" (this is common as far away as Yorkshire). Similarly, the local version of "you" is pronounced , rhyming with "now" .

The local pronunciation includes "goo" (elsewhere "go") or "gewin'" is similar to that elsewhere in the Midlands. It is quite common for broad Black Country speakers to say "'agooin'" where others say "going." A woman is a "wench", a man is a "mon", a nurse is a "nuss" and home is "wom". An apple is an "opple" .

Other examples are "code" for the word cold, and "goost" for the word ghost. A sofa becomes a "sofie", and a fag (cigarette), a "fake". Seen becomes "sid".

Put together, "Ah just sid a goost, so Ah'm a gooin to sit on mah sofie and 'ave a fake" (I have just seen a ghost, so I am going to sit upon my sofa and have a cigarette)

Food may be called "fittle" (after victuals or "vittles"), so "bostin fittle" is "good food".

One participant in the "Where's our Spake Gone" project related the following: "Day say yom call oos rabbits up ere. I say we day, dey say yow say "Tah rah rabbits". We'm say tah-ra a bit, 'n to dem, it sound like we'm calling dem rabbits." ("They say you call us rabbits there, I said we don't, (but) they say you say "tah rah rabbits". We say "tah rah a bit" (tah rah for a little while) and to them, it sounds like we are calling them rabbits.")

The dialect has local differences, and sounds and phrases differ across the towns; often people can mishear a word or phrase and write it down wrong as in "shut charow up," which actually is "shut ya row up," so one has to be careful when hearing words and phrases.

Depiction in art or literature

From the 19th century onwards, the area gained widespread notoriety for its hellish appearance, a depiction that made its way into the published works of the time.Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

's novel ''The Old Curiosity Shop

''The Old Curiosity Shop'' is one of two novels (the other being ''Barnaby Rudge'') which Charles Dickens published along with short stories in his weekly serial ''Master Humphrey's Clock'', from 1840 to 1841. It was so popular that New York r ...

'', written in 1841, described how the area's local factory chimneys ''"Poured out their plague of smoke, obscured the light, and made foul the melancholy air".'' In 1862, Elihu Burritt

Elihu Burritt (December 8, 1810March 6, 1879) was an American diplomat, philanthropist and social activist.Arthur Weinberg and Lila Shaffer Weinberg. ''Instead of Violence: Writings by the Great Advocates of Peace and Nonviolence Throughout Histo ...

, the American Consul in Birmingham, described the region as ''"black by day and red by night"'', because of the smoke and grime generated by the intense manufacturing activity and the glow from furnaces at night. Early 20th century representations of the region can be found in the Mercian novels of Francis Brett Young, most notably ''My Brother Jonathan

''My Brother Jonathan'' is a 1948 British drama film directed by Harold French and starring Michael Denison, Dulcie Gray, Ronald Howard and Beatrice Campbell. It is adapted from the 1930 novel '' My Brother Jonathan'' by Francis Brett Young, ...

'' (1928).

Carol Thompson the curator "The Making of Mordor" at Wolverhampton Art Gallery

Wolverhampton Art Gallery is located in the City of Wolverhampton, in the West Midlands, United Kingdom. The building was funded and constructed by local contractor Philip Horsman (1825–1890), and built on land provided by the municipal aut ...

in the last quarter of 2014 stated that J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlins ...

's description of the grim region of Mordor

In J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional world of Middle-earth, Mordor (pronounced ; from Sindarin ''Black Land'' and Quenya ''Land of Shadow'') is the realm and base of the evil Sauron. It lay to the east of Gondor and the great river Anduin, an ...

"resonates strongly with contemporary accounts of the Black Country", in his famed novel ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's b ...

''. Indeed, in the Elvish Sindarin language, ''Mor-Dor'' means ''Dark'' (or ''Black'') ''Land''. It is also claimed by one Black Country scholar (Peter Higginson) that the character of Bilbo Baggins

Bilbo Baggins is the title character and protagonist of J. R. R. Tolkien's 1937 novel ''The Hobbit'', a supporting character in ''The Lord of the Rings'', and the fictional narrator (along with Frodo Baggins) of many of Tolkien's Middle-ear ...

may have been based on Tolkien's observation of Mayor Ben Bilboe of Bilston

Bilston is a market town, ward, and civil parish located in Wolverhampton, West Midlands, England. It is close to the borders of Sandwell and Walsall. The nearest towns are Darlaston, Wednesbury, and Willenhall. Historically in Staffordshi ...

in The Black Country, who was a Communist and Labour Party member from the Lunt

The Lunt is a residential area of Bilston within the city of Wolverhampton and is part of the West Midlands conurbation in England.

It was mostly laid out by the local council during the 1920s and 1930s, with houses being built to rehouse peopl ...

in Bilston. But the scholarly evidence for this is still questionable.

Brewing

The Black Country is notable for its small breweries and brewpubs which continued brewing their ownbeer

Beer is one of the oldest and the most widely consumed type of alcoholic drink in the world, and the third most popular drink overall after water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of starches, mainly derived from ce ...

alongside the larger breweries which opened in the Industrial Revolution. Small breweries and brewpubs in the Black Country include Bathams in Brierley Hill

Brierley Hill is a town and electoral ward in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley, West Midlands, England, 2.5 miles south of Dudley and 2 miles north of Stourbridge. Part of the Black Country and in a heavily industrialised area, it has a pop ...

, Holdens in Woodsetton, Sarah Hughes

Sarah Elizabeth Hughes (born May 2, 1985) is a former American competitive figure skater. She is the 2002 Olympic Champion and the 2001 World bronze medalist in ladies' singles.

Personal life

Hughes was born in Great Neck, New York, a subur ...

in Sedgley, Black Country Ales in Lower Gornal and the Old Swan Inn (Ma Pardoe's) in Netherton. They produce light and dark mild ale

Mild ale is a type of ale. Modern milds are mostly dark-coloured, with an alcohol by volume (ABV) of 3% to 3.6%, although there are lighter-hued as well as stronger milds, reaching 6% abv and higher. Mild originated in Britain in the 17th centur ...

s, as well as malt-accented bitter

Bitter may refer to:

Common uses

* Resentment, negative emotion or attitude, similar to being jaded, cynical or otherwise negatively affected by experience

* Bitter (taste), one of the five basic tastes

Books

* '' Bitter (novel)'', a 2022 nove ...

s and seasonal strong ale

Strong ale is a type of ale, usually above 5% abv and often higher, between 7% to 11% abv, which spans a number of beer styles, including old ale, barley wine and Burton ale. Strong ales are brewed throughout Europe and beyond, including in Engl ...

s.

Media

The Black Country is home to one television station,Made in Birmingham

Local TV Birmingham (typeset as LOCAL TV Birmingham) is a British local television station, serving Birmingham, the Black Country, Wolverhampton and Solihull in the West Midlands of England.

The station is owned and operated by Local Televisio ...

, and three region wide radio stations – BBC WM, Free Radio and Free Radio 80s. Both Free Radio (formerly BRMB (Birmingham and Beacon Radio Wolverhampton) and Free Radio 80s (formerly Beacon 303, Radio WABC & Gold) have broadcast since 1976 from transmitters at Turner's Hill

Turners Hill or Turner's Hill is the highest hill in the county of West Midlands, United Kingdom at above sea level. The hill is in the Rowley Hills range, situated in Rowley Regis, near the boundary with Dudley.

The hill can be seen from many ...

and Sedgley, with the studios which were previously located in Wolverhampton being moved to Oldbury and Birmingham respectively.

The area also has three other radio stations which only officially cover part of the region. Black Country Radio (born from a merger of 102.5 The Bridge and BCCR) who are based in Brierley Hill

Brierley Hill is a town and electoral ward in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley, West Midlands, England, 2.5 miles south of Dudley and 2 miles north of Stourbridge. Part of the Black Country and in a heavily industrialised area, it has a pop ...

, and Ambur Radio who broadcast from Walsall.

The ''Express and Star

The ''Express & Star'' is a regional evening newspaper in Britain. Founded in 1889, it is based in Wolverhampton, England, and covers the West Midlands county and Staffordshire.

Currently edited by Martin Wright, the ''Express & Star'' publish ...

'' is one of the region's two daily newspapers, publishing eleven local editions from its Wolverhampton headquarters and its five district offices (for example the Dudley edition is considerably different in content from the Wolverhampton or Stafford editions). It is the biggest selling regional paper in the UK. Incidentally, the ''Express and Star'', traditionally a Black Country paper, has expanded to the point where they sell copies from vendors in Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1. ...

city centre.

''The Black Country Mail'' – a local edition of the ''Birmingham Mail

The ''Birmingham Mail'' (branded the ''Black Country Mail'' in the Black Country) is a tabloid newspaper based in Birmingham, England but distributed around Birmingham, the Black Country, and Solihull and parts of Warwickshire, Worcestershire a ...

'' – is the region's other daily newspaper. Its regional base is in Walsall

Walsall (, or ; locally ) is a market town and administrative centre in the West Midlands County, England. Historically part of Staffordshire, it is located north-west of Birmingham, east of Wolverhampton and from Lichfield.

Walsall is th ...

town centre.

Established in 1973, from a site in High Street, Cradley Heath

Cradley Heath is a town in the Rowley Regis area of the Metropolitan Borough of Sandwell, West Midlands, England approximately north-west of Halesowen, south of Dudley and west of central Birmingham. Cradley Heath is often confused with t ...

, the ''Black Country Bugle

The ''Black Country Bugle'' is a paid-for weekly publication, which highlights the industrial heritage, history, legends, local humour and readers' stories pertaining to the Black Country region, which forms the western half of the West Midlands ...

'' has also contributed to the region's history. It started as a fortnightly publication, but due to its widespread appeal, now appears on a weekly basis. It is now located above the Dudley Archives and Local History Centre on Tipton Road, Dudley.

South Staffordshire Railway

See also

*Pays Noir

The ''Pays Noir'' (French, 'black country') refers to a region of Belgium, centered on Charleroi in the province of Hainaut in Wallonia so named for the geological presence of coal. In the 19th century the region rapidly industrialised first with ...

(in French meaning "Black country"), referring to Sillon industriel, a similar early industrial region in Belgium.

Notes

References

* *Further reading

* Raybould, T. J. (1973). ''The Economic Emergence of the Black Country: A Study of the Dudley Estate''. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. . * Rowlands, M. B. (1975). ''Masters and Men in the West Midlands metalware trades before the industrial revolution''. Manchester: Manchester University Press. * Gale, W. K. V. (1966). ''The Black Country Iron Industry: A Technical History''. London: The Iron and Steel Institute. * Higgs, L. (2004) ''A Description of Grammatical Features and Their Variation in the Black Country Dialect'' Schwabe Verlag Basel. * Led Zeppelin (1975). " Black Country Woman", '' Physical Graffiti''. * Webster, L. (2012) ''Lone Wolf: memoirs in the form of short stories''. Dudley: Kates Hill Press. .External links

Black Country Slang

The best collection of Black Country dialect and slang words — if yow cor spake owr bostin language now yow con!

Series of four films about the history and life of the Black Country *

BBC Black Country

BBC website for Dudley, Sandwell, Walsall and Wolverhampton

Black Country History

Catalogue of Museums and Archives in the Black Country

Black Country Living Museum Website

Black Country Society

The Black Country Alphabet

{{Authority control Areas of the West Midlands (county) Coal mining regions in England History of the West Midlands (county)