Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

is a country in

Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

[CIA Factbook](_blank)

/ref> bordered by Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

to the west; the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

and Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

to the south; Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

and Kaliningrad Oblast

Kaliningrad Oblast (russian: Калинингра́дская о́бласть, translit=Kaliningradskaya oblast') is the westernmost federal subject of Russia. It is a semi-exclave situated on the Baltic Sea. The largest city and admin ...

, a Russian exclave, to the north. The total area of Poland is ,Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

rivers on the North-Central European Plain, Poland has at its largest extent expanded as far as the Baltic, the Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

and the Carpathians

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretches ...

, while in periods of weakness it has shrunk drastically or even ceased to exist.

Territorial history

In 1492, the territory of Poland-Lithuania – not counting the fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

s of Mazovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

, Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

, and East Prussia – covered , making it the largest territory in Europe; by 1793, it had fallen to , the same size as Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

, and in 1795, it disappeared completely.West Slavs

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic lan ...

and occupy what some believe to be the original homeland of the Slavic peoples. While other groups migrated, the Polanie remained ''in situ'' along the Vistula

The Vistula (; pl, Wisła, ) is the longest river in Poland and the ninth-longest river in Europe, at in length. The drainage basin, reaching into three other nations, covers , of which is in Poland.

The Vistula rises at Barania Góra in ...

, from the river's sources to its estuary at the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

. There is no other European nation centred to such an extent on one river.Baptism of Poland

The Christianization of Poland ( pl, chrystianizacja Polski) refers to the introduction and subsequent spread of Christianity in Poland. The impetus to the process was the Baptism of Poland ( pl, chrzest Polski), the personal baptism of Mieszk ...

), when the state covered territory similar to that of present-day Poland. In 1025 CE, Poland became a kingdom

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

. In 1569, Poland cemented a long association

Association may refer to:

*Club (organization), an association of two or more people united by a common interest or goal

*Trade association, an organization founded and funded by businesses that operate in a specific industry

*Voluntary associatio ...

with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Lit ...

by signing the Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the per ...

, forming the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was one of the largest and most populous countries in 16th- and 17th-century Europe.[pg 554 – ]

''Poland-Lithuania was another country that experienced its 'Golden Age' during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The realm of the last Jagiellons was absolutely the largest state in Europe''.[pg 51 – ]

''"the deluge," denoting the downfall of Poland, at that time the largest state in Europe, stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea and from the Oder to the Dnieper River.''

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth had many characteristics that made it unique among states of that era. The Commonwealth's political system, often called the Noble's Democracy or Golden Freedom, was characterized by the sovereign's power being reduced by laws and the legislature (

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth had many characteristics that made it unique among states of that era. The Commonwealth's political system, often called the Noble's Democracy or Golden Freedom, was characterized by the sovereign's power being reduced by laws and the legislature (Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

), which was controlled by the nobility ( szlachta). This system was a precursor to the modern concepts of broader democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

[pg 3 – ] and constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

.[pg 84 – ]

''enabled them to push a new constitution through the Diet, transforming Poland from an anarchic republic ... into a reasonably modern constitutional monarchy''[pg 34 – ''It was Poland more than any other Western European country that became the early symbol of a liberal and constitutional monarchy.''] The two comprising states of the Commonwealth were formally equal, although in reality Poland was a dominant partner in the union.religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

unusual for its age,[pg 373 – ''Quoting from ]Sarmatian Review

The ''Sarmatian Review'' () is an English-language peer-reviewed academic tri-quarterly journal devoted to Slavistics (the study of the histories, cultures, and societies of the Slavic nations of Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe).

The '' ...

academic journal mission statement: ''Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was ��characterized by religious tolerance unusual in pre-modern Europe although the degree of tolerance varied over time.[pg 122 – '' olandsecured for a time a rule of religious tolerance, particularly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries ... The situation changed, however, toward the end of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.'']

In the late 18th century, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth began to collapse. Its neighbouring states were able to slowly dismember the Commonwealth. In 1795, Poland's territory was completely partitioned among the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. Poland regained its independence as the Second Polish Republic in 1918 after World War I, but lost it in World War II through occupation by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Poland lost over six million citizens in World War II, emerging several years later as the socialist People's Republic of Poland within the Eastern Bloc, under strong Soviet influence.

During the Revolutions of 1989

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, was a revolutionary wave that resulted in the end of most communist states in the world. Sometimes this revolutionary wave is also called the Fall of Nations or the Autumn of Nat ...

, communist rule was overthrown and Poland became what is constitutionally known as the "Third Polish Republic." Poland is a unitary state

A unitary state is a sovereign state governed as a single entity in which the central government is the supreme authority. The central government may create (or abolish) administrative divisions (sub-national units). Such units exercise only ...

made up of sixteen voivodeships ( pl, województwo). Poland is a member of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been de ...

, NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Poland currently has a population of over 38 million people,

Territorial timeline

In the period following the emergence of Poland in the 10th century, the Polish nation was led by a series of rulers of the Piast dynasty, who converted the Poles to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, created a sizeable Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

an state, and integrated Poland into European culture

The culture of Europe is rooted in its art, architecture, film, different types of music, economics, literature, and philosophy. European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage".

Definition ...

. Formidable foreign enemies and internal fragmentation

In computer storage, fragmentation is a phenomenon in which storage space, main storage or secondary storage, is used inefficiently, reducing capacity or performance and often both. The exact consequences of fragmentation depend on the specific ...

eroded this initial structure in the 13th century, but consolidation in the 14th century laid the base for the Polish Kingdom.

Beginning with the Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila, the Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty (, pl, dynastia jagiellońska), otherwise the Jagiellon dynasty ( pl, dynastia Jagiellonów), the House of Jagiellon ( pl, Dom Jagiellonów), or simply the Jagiellons ( pl, Jagiellonowie), was the name assumed by a cad ...

(1385–1569) ruled the Polish–Lithuanian union. The Lublin Union of 1569 established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

as an influential player in European politics and a vital cultural entity.

Duchy of Prussia

In 1525, during the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and ...

, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

, Albert of Hohenzollern, secularized the order's Prussian territory, becoming Albert, Duke of Prussia. The Duchy of Prussia

The Duchy of Prussia (german: Herzogtum Preußen, pl, Księstwo Pruskie, lt, Prūsijos kunigaikštystė) or Ducal Prussia (german: Herzogliches Preußen, link=no; pl, Prusy Książęce, link=no) was a duchy in the region of Prussia establish ...

, which had its capital in Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was name ...

, was established as a fief of the Crown of Poland

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Korona Królestwa Polskiego; Latin: ''Corona Regni Poloniae''), known also as the Polish Crown, is the common name for the historic Late Middle Ages territorial possessions of the King of Poland, includi ...

.

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia was a vassal state of the Crown of the Polish Kingdom from 1569 to 1726, and incorporated into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1726. In 1561, during the Livonian Wars

The Livonian War (1558–1583) was the Russian invasion of Old Livonia, and the prolonged series of military conflicts that followed, in which Tsar Ivan the Terrible of Russia (Muscovy) unsuccessfully fought for control of the region (pre ...

, the Livonian Confederation was dismantled and the Livonian Order, an order of German knights, was disbanded. On the basis of the Treaty of Vilnius, the southern part of Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

and the northern part of Latvia were ceded to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state that existed from the 13th century to 1795, when the territory was partitioned among the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Habsburg Empire of Austria. The state was founded by Lit ...

and formed into the Ducatus Ultradunensis (Pārdaugavas hercogiste).

Kingdom of Poland until 1385

Territorial changes before and during the Kingdom of Poland (1025–1385), ending with the Union of Krewo

In a strict sense, the Union of Krewo or Act of Krėva (also spelled Union of Krevo, Act of Kreva; be, Крэўская унія, translit=Kreŭskaja unija; pl, unia w Krewie; lt, Krėvos sutartis) comprised a set of prenuptial promises made ...

.

992

Mieszko I of Poland

Mieszko I (; – 25 May 992) was the first ruler of Poland and the founder of the first independent Polish state, the Duchy of Poland. His reign stretched from 960 to his death and he was a member of the Piast dynasty, a son of Siemomysł and a ...

was the first historical ruler of the first independent Polish state ever recorded- Duchy of Poland. He was responsible for the introduction and subsequent spread of Christianity in Poland.Polish tribes

"Polish tribes" is a term used sometimes to describe the tribes of West Slavic Lechites that lived from around the mid-6th century in the territories that became Polish with the creation of the Polish state by the Piast dynasty. The territory ...

and other West Slavs

The West Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak the West Slavic languages. They separated from the common Slavic group around the 7th century, and established independent polities in Central Europe by the 8th to 9th centuries. The West Slavic lan ...

were temporarily added to his territory into a single Polish state, soon to be independent again. The last of his conquests were Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

and Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

that were incorporated some time before 990.

1025

During the reign of

During the reign of Bolesław the Brave Boleslav or Bolesław may refer to:

In people:

* Boleslaw (given name)

In geography:

*Bolesław, Dąbrowa County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

*Bolesław, Olkusz County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

*Bolesław, Silesian Voivodeship, Pol ...

, relations between Poland and the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

deteriorated, resulting in a series of wars (1002–1005, 1007–1013, 1015–1018). From 1003–1004 Bolesław intervened militarily in Czech dynastic conflicts. After his forces were removed from Bohemia in 1018, Bolesław retained Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

.Richeza of Lotharingia

Richeza of Lotharingia (also called ''Richenza'', ''Rixa'', ''Ryksa''; born about 995/1000 – 21 March 1063) was a member of the Ezzonen dynasty who became queen of Poland as the wife of Mieszko II Lambert. Her Polish marriage was arranged to s ...

, the niece of Emperor Otto III and future mother of Casimir I the Restorer

Casimir I the Restorer (; 25 July 1016 – 28 November 1058), a member of the Piast dynasty, was the duke of Poland from 1040 until his death. Casimir was the son of Mieszko II Lambert and Richeza of Lotharingia. He is known as the Restorer beca ...

, took place. The conflicts with Germany ended in 1018 with the Peace of Bautzen accord, on favorable terms for Bolesław. In the context of the 1018 Kiev expedition, Bolesław took over the western part of Red Ruthenia

Red Ruthenia or Red Rus' ( la, Ruthenia Rubra; '; uk, Червона Русь, Chervona Rus'; pl, Ruś Czerwona, Ruś Halicka; russian: Червонная Русь, Chervonnaya Rus'; ro, Rutenia Roșie), is a term used since the Middle Ages fo ...

. In 1025, shortly before his death, Bolesław I the Brave finally succeeded in obtaining the papal permission to crown himself, and became the first king of Poland.[Various authors, ed. Marek Derwich and Adam Żurek, ''U źródeł Polski (do roku 1038)'' (Foundations of Poland (until year 1038)), p. 168–183, Andrzej Pleszczyński]

1050

The first Piast monarchy collapsed after the death of Bolesław's son – king

The first Piast monarchy collapsed after the death of Bolesław's son – king Mieszko II

Mieszko II Lambert (; c. 990 – 10/11 May 1034) was King of Poland from 1025 to 1031, and Duke from 1032 until his death.

He was the second son of Bolesław I the Brave, but the eldest born from his third wife Emnilda of Lusatia. He was proba ...

in 1034. Deprived of a government, Poland was ravaged by an anti-feudal and pagan rebellion, and in 1039 by the forces of King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

Bretislav of Bohemia. The country suffered territorial losses, and the functioning of the Gniezno archdiocese was disrupted.[Various authors, ed. Marek Derwich and Adam Żurek, ''U źródeł Polski (do roku 1038)'' (Foundations of Poland (until year 1038)), pp. 182–187, Andrzej Pleszczyński]

After returning from exile in 1039, Duke Casimir I (1016–1058), properly known as the Restorer, rebuilt the Polish monarchy and the country's territorial integrity through several military campaigns: in 1047, Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

was taken back from Miecław, and in 1050 Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

from the Czechs. Casimir was aided by the recent adversaries of Poland, the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

and Kievan Rus

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern Europe, Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Hist ...

, both of whom disliked the chaos in Poland. Casimir's son Bolesław II the Generous

Bolesław II the Bold, also known as the Generous ( pl, Bolesław II Szczodry ; ''Śmiały''; c. 1042 – 2 or 3 April 1081 or 1082), was Duke of Poland from 1058 to 1076 and third King of Poland from 1076 to 1079. He was the eldest son of Duk ...

managed to restore most of the country's strength and influence and was able to crown himself king in 1076. In 1079 there was an anti-Bolesław conspiracy or conflict that involved the Bishop of Cracow. Bolesław had Bishop Stanislaus of Szczepanów

Stanislaus of Szczepanów ( pl, Stanisław ze Szczepanowa; 26 July 1030 – 11 April 1079) was Bishop of Kraków known chiefly for having been martyred by the Polish king Bolesław II the Generous. Stanislaus is venerated in the Roman Ca ...

executed; subsequently Bolesław was forced to abdicate the Polish throne because of the pressure from the Catholic Church and the pro-imperial faction of the nobility. The rule over Poland passed into the hands of his younger brother Władysław Herman.

1125

After a power struggle, Bolesław III the Wry-mouthed (son of Władysław Herman, ruled 1102–1138) became the Duke of Poland by defeating his half-brother in 1106–1107. Bolesław's major achievement was the reconquest of all of Mieszko I's

After a power struggle, Bolesław III the Wry-mouthed (son of Władysław Herman, ruled 1102–1138) became the Duke of Poland by defeating his half-brother in 1106–1107. Bolesław's major achievement was the reconquest of all of Mieszko I's Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

, a task begun by his father and completed by Bolesław around 1123. Szczecin was subdued in a bloody takeover and Western Pomerania up to Rügen

Rügen (; la, Rugia, ) is Germany's largest island. It is located off the Pomeranian coast in the Baltic Sea and belongs to the state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

The "gateway" to Rügen island is the Hanseatic city of Stralsund, where ...

, except for the directly incorporated southern part, became Bolesław's fief

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

, to be ruled locally by Wartislaw I, the first duke of the Griffin dynasty.Christianization

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

of the region was initiated in earnest, an effort crowned by the establishment of the Pomeranian Wolin Diocese after Bolesław's death in 1140.

1145

The Testament of Bolesław III Krzywousty was a political act by the

The Testament of Bolesław III Krzywousty was a political act by the Piast

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branche ...

duke Bolesław III Wrymouth

Bolesław III Wrymouth ( pl, Bolesław III Krzywousty; 20 August 1086 – 28 October 1138), also known as Boleslaus the Wry-mouthed, was the duke of Lesser Poland, Silesia and Sandomierz between 1102 and 1107 and over the whole of Poland between ...

of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, in which he established rules for governance of the Polish kingdom by his four surviving sons after his death. By issuing it, Bolesław planned to guarantee that his heirs would not fight among themselves, and would preserve the unity of his lands under the House of Piast

The House of Piast was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. The first documented Polish monarch was Duke Mieszko I (c. 930–992). The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir III the Great.

Branc ...

. However, he failed; soon after his death his sons fought each other, and Poland entered a period of fragmentation lasting about 200 years.

1238

In the first half of the 13th century Silesian duke

In the first half of the 13th century Silesian duke Henry I the Bearded

Henry the Bearded ( pl, Henryk (Jędrzych) Brodaty, german: Heinrich der Bärtige; c. 1165/70 – 19 March 1238) was a Polish duke from the Piast dynasty.

He was Duke of Silesia at Wrocław from 1201, Duke of Kraków and High Duke of all Pol ...

, reunited much of the divided Kingdom of Poland (''Regnum Poloniae''). His expeditions led him as far north as the Duchy of Pomerania

The Duchy of Pomerania (german: Herzogtum Pommern; pl, Księstwo Pomorskie; Latin: ''Ducatus Pomeraniae'') was a duchy in Pomerania on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, ruled by dukes of the House of Pomerania (''Griffins''). The country ha ...

, where for a short time he held some of its southern areas. He became the duke of Cracow (Polonia Minor

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

) in 1232, which gave him the title of senior duke of Poland (see Testament of Bolesław III Krzywousty

A testament is a document that the author has sworn to be true. In law it usually means last will and testament.

Testament or The Testament can also refer to:

Books

* ''Testament'' (comic book), a 2005 comic book

* ''Testament'', a thriller nov ...

), and came into possession of most of Greater Poland in 1234. Henry failed in his attempt to achieve the Polish crown. His activity in this field was continued by his son and successor Henry II the Pious

Henry II the Pious ( pl, Henryk II Pobożny; 1196 – 9 April 1241) was Duke of Silesia and High Duke of Poland as well as Duke of South-Greater Poland from 1238 until his death. Between 1238 and 1239 he also served as regent of Sandomierz and ...

, until his sudden death in 1241 ( Battle of Legnica). His successors were not able to maintain their holdings outside of Silesia, which were lost to other Piast dukes. Polish historians refer to territories acquired by Silesian dukes in this period as ''Monarchia Henryków śląskich'' ("The monarchy of the Silesian Henries"). In those days Wrocław

Wrocław (; german: Breslau, or . ; Silesian German: ''Brassel'') is a city in southwestern Poland and the largest city in the historical region of Silesia. It lies on the banks of the River Oder in the Silesian Lowlands of Central Europe, rou ...

was the political center of the divided Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exi ...

.

1248

Few years after the death of Henry II the Pious

Henry II the Pious ( pl, Henryk II Pobożny; 1196 – 9 April 1241) was Duke of Silesia and High Duke of Poland as well as Duke of South-Greater Poland from 1238 until his death. Between 1238 and 1239 he also served as regent of Sandomierz and ...

his son – Bolesław II the Bald Boleslav or Bolesław may refer to:

In people:

* Boleslaw (given name)

In geography:

* Bolesław, Dąbrowa County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

* Bolesław, Olkusz County, Lesser Poland Voivodeship, Poland

* Bolesław, Silesian Voivodeship, ...

– sold the northwest part of his duchy – the Lubusz Land

Lubusz Land ( pl, Ziemia lubuska; german: Land Lebus) is a historical region and cultural landscape in Poland and Germany on both sides of the Oder river.

Originally the settlement area of the Lechites, the swampy area was located east of Branden ...

– to Magdeburg's Archbishop Wilbrand von Käfernburg and the Ascanian margraves of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 sq ...

. This had far reaching negative consequences for the integrity of the western border, leading to an expansion of Brandenburg possessions into the east of Odra river. As a result, a wide piece of land was annexed from Poland and Pomerania that together with Lubusz Land formed the newly established Brandenburgian province of Neumark.

1295

In 1295,

In 1295, Przemysł II

Przemysł II ( also given in English and Latin language, Latin as ''Premyslas'' or ''Premislaus'' or in Polish as '; 14 October 1257 – 8 February 1296) was the Duke of Poznań from 1257–1279, of Greater Poland from 1279 to 1296, of Kraków f ...

of Greater Poland became the first, since Bolesław II, Piast duke crowned as King of Poland, but he ruled over only a part of the territory of Poland (including from 1294 Gdańsk Pomerania

Gdańsk Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze Gdańskie), csb, Gduńsczim Pòmòrzã, german: Danziger Pommern) is a geographical region within Pomerelia in northern and northwestern Poland, covering the bulk of Pomeranian Voivodeship.

It forms a part and ...

) and was assassinated soon after his coronation.

1300

A more extensive unification of Polish lands was accomplished by a foreign ruler,

A more extensive unification of Polish lands was accomplished by a foreign ruler, Wenceslaus II of Bohemia

Wenceslaus II Přemyslid ( cs, Václav II.; pl, Wacław II Czeski; 27 SeptemberK. Charvátová, ''Václav II. Král český a polský'', Prague 2007, p. 18. 1271 – 21 June 1305) was King of Bohemia (1278–1305), Duke of Cracow (1291–1 ...

of the Přemyslid dynasty

The Přemyslid dynasty or House of Přemyslid ( cs, Přemyslovci, german: Premysliden, pl, Przemyślidzi) was a Bohemian royal dynasty that reigned in the Duchy of Bohemia and later Kingdom of Bohemia and Margraviate of Moravia (9th century–130 ...

, who married Przemysł's daughter and became King of Poland in 1300. Václav's heavy-handed policies soon caused him to lose whatever support he had earlier in his reign; he died in 1305.

1333–70

After the death of

After the death of Wenceslaus III of Bohemia

Wenceslaus III ( cz, Václav III., hu, Vencel, pl, Wacław, hr, Vjenceslav, sk, Václav; 6 October 12894 August 1306) was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1301 and 1305, and King of Bohemia and Poland from 1305. He was the son of Wencesla ...

– son of Wenceslaus II – in 1306, most of the Polish Lands came under the rule of duke Władysław I the Elbow-high Władysław is a Polish given male name, cognate with Vladislav. The feminine form is Władysława, archaic forms are Włodzisław (male) and Włodzisława (female), and Wladislaw is a variation. These names may refer to:

Famous people Mononym

* ...

. However at this points, various foreign states were staking their claims on some parts of Poland. Margraviate of Brandenburg

The Margraviate of Brandenburg (german: link=no, Markgrafschaft Brandenburg) was a major principality of the Holy Roman Empire from 1157 to 1806 that played a pivotal role in the history of Germany and Central Europe.

Brandenburg developed out ...

invaded Pomerelia in 1308, leading Władysław I the Elbow-high to request assistance from the Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

, who evicted the Brandenburgers but took the area for themselves, annexed and incorporated it into the Teutonic Order state

The State of the Teutonic Order (german: Staat des Deutschen Ordens, ; la, Civitas Ordinis Theutonici; lt, Vokiečių ordino valstybė; pl, Państwo zakonu krzyżackiego), also called () or (), was a medieval Crusader state, located in Centr ...

in 1309 (Teutonic takeover of Danzig (Gdańsk)

The city of Danzig (Gdańsk) was captured by the State of the Teutonic Order on 13 November 1308, resulting in a massacre of its inhabitants and marking the beginning of tensions between Poland and the Teutonic Order. Originally the knights moved ...

and Treaty of Soldin/ Myślibórz). This event caused a long-lasting dispute between Poland and the Teutonic Order over the control of Gdańsk Pomerania

Gdańsk Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze Gdańskie), csb, Gduńsczim Pòmòrzã, german: Danziger Pommern) is a geographical region within Pomerelia in northern and northwestern Poland, covering the bulk of Pomeranian Voivodeship.

It forms a part and ...

. It resulted in a series of Polish–Teutonic War

Polish–Teutonic War may refer to:

* Teutonic takeover of Danzig (Gdańsk) (1308–1309)

*Polish–Teutonic War (1326–1332) over Pomerelia, concluded by the Treaty of Kalisz (1343)

*the Polish–Lithuanian–Teutonic War or ''Great War'' (140 ...

s throughout 14th and 15th centuries.

During this time, all Silesian duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

s accepted Władysław's claims for sovereignty over other Piasts. After acquiring papal consent for his coronation, all nine dukes of Silesia The Duke of Silesia was the sons and descendants of the Polish Duke Bolesław III Wrymouth. In accordance with the last will and testament of Bolesław, upon his death his lands were divided into four or five hereditary provinces distributed amo ...

declared twice (in 1319 before and in 1320 after the coronation) that their realms lay inside the borders of the Polish Kingdom. However, despite formal papal consent for the coronation, Władysław's right to the crown was disputed by successors of Wenceslaus III (a king of both Bohemia and Poland) on the Bohemian throne. In 1327 John of Bohemia invaded. After the intervention of King Charles I of Hungary

Charles I, also known as Charles Robert ( hu, Károly Róbert; hr, Karlo Robert; sk, Karol Róbert; 128816 July 1342) was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1308 to his death. He was a member of the Capetian House of Anjou and the only son of ...

he left Polonia Minor

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name Małopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Kraków. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a ...

, but on his way back he enforced his supremacy over the Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

n Piasts.

In 1329 Władysław I the Elbow-high fought with the Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

. The Order was supported by John of Bohemia who dominated the dukes of Masovia

Mazovia or Masovia ( pl, Mazowsze) is a historical region in mid-north-eastern Poland. It spans the North European Plain, roughly between Łódź and Białystok, with Warsaw being the unofficial capital and largest city. Throughout the centurie ...

and Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( pl, Dolny Śląsk; cz, Dolní Slezsko; german: Niederschlesien; szl, Dolny Ślōnsk; hsb, Delnja Šleska; dsb, Dolna Šlazyńska; Silesian German: ''Niederschläsing''; la, Silesia Inferior) is the northwestern part of the ...

.

In 1335 John of Bohemia renounced his claim in favour of Casimir the Great, who in return renounced his claims to the Silesia province. This was formalized in the Treaty of Trentschin

The Treaty of Trentschin was concluded on 24 August 1335 between King Casimir III of Poland and King John of Bohemia as well as his son Margrave Charles IV. The agreement was reached by the agency of Casimir's brother-in-law King Charles I of H ...

and Congress of Visegrád (1335)

The first Congress of Visegrád was a 1335 summit in Visegrád in which Kings John I of Bohemia, Charles I of Hungary and Casimir III of Poland formed an anti-Habsburg alliance. The three leaders agreed to create new commercial routes to bypass ...

, ratified in 1339Halych

Halych ( uk, Га́лич ; ro, Halici; pl, Halicz; russian: Га́лич, Galich; german: Halytsch, ''Halitsch'' or ''Galitsch''; yi, העליטש) is a historic city on the Dniester River in western Ukraine. The city gave its name to the P ...

–Volodymyr Volodymyr ( uk, Володи́мир, Volodýmyr, , orv, Володимѣръ) is a Ukrainian given name of Old East Slavic origin. The related Ancient Slavic, such as Czech, Russian, Serbian, Croatian, etc. form of the name is Володимѣръ ...

area of Rus'. The city of Lwów quickly developed to become a main town of this new region.

Allied with Denmark and Western Pomerania, Casimir was able to impose some corrections on the western border as well. In 1365 Drezdenko and Santok became Poland's fiefs

A fief (; la, feudum) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form ...

, while Wałcz

Wałcz (pronounced ; german: Deutsch Krone) is a county town in Wałcz County of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in northwestern Poland. During the years 1975 to 1998, the city was administratively part of the Piła Voivodeship.

Granted city r ...

district was in 1368 taken outright, severing the land connection between Brandenburg and the Teutonic state and connecting Poland with Farther Pomerania.

Kingdom of Poland 1385 to 1569

Territorial changes during the Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569)

The Crown of the Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Korona Królestwa Polskiego; Latin: ''Corona Regni Poloniae''), known also as the Polish Crown, is the common name for the historic Late Middle Ages territorial possessions of the King of Poland, includi ...

, starting with the Union of Krewo

In a strict sense, the Union of Krewo or Act of Krėva (also spelled Union of Krevo, Act of Kreva; be, Крэўская унія, translit=Kreŭskaja unija; pl, unia w Krewie; lt, Krėvos sutartis) comprised a set of prenuptial promises made ...

and ending with the Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the per ...

.

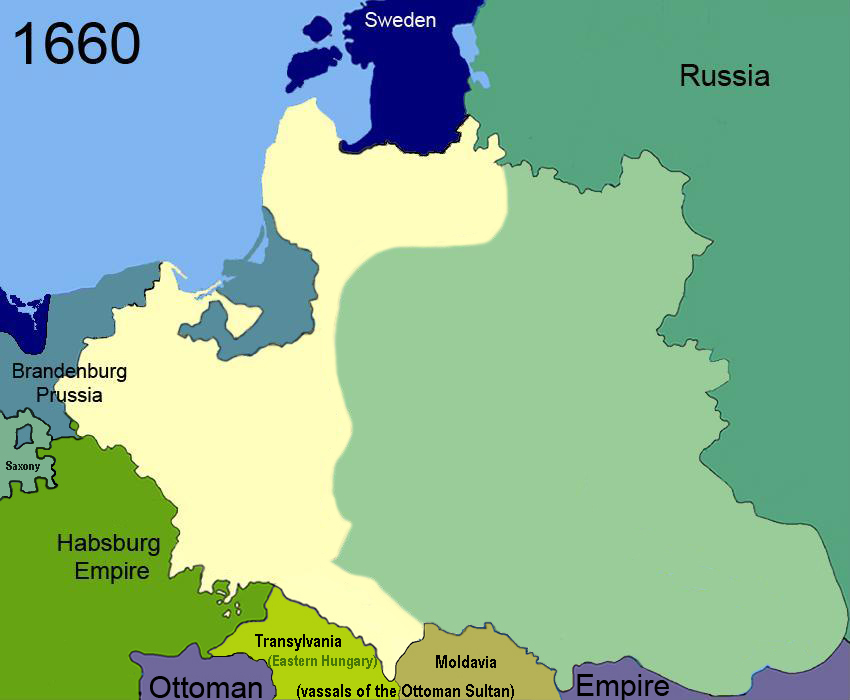

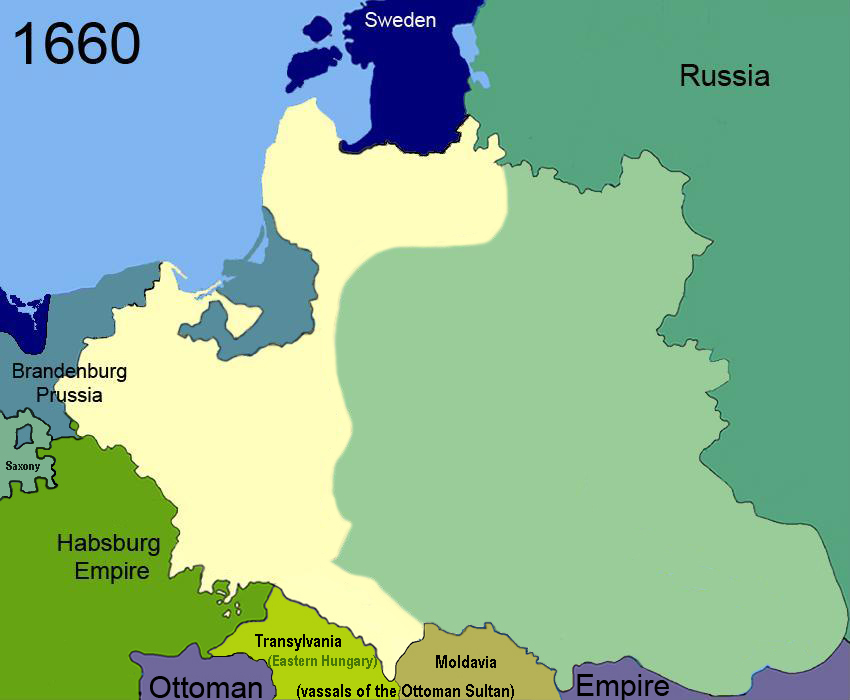

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1569 to 1795

Territorial changes during the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

, starting with the Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the per ...

and ending with the Third Partition of Poland

The Third Partition of Poland (1795) was the last in a series of the Partitions of Poland–Lithuania and the land of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth among Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Russian Empire which effectively ended Polis ...

.

1610 to 1612

During the Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618) Polish–Muscovite War can refer to:

* Muscovite–Lithuanian Wars

* Polish–Muscovite War (1605–18)

* Smolensk War (1631–34)

* Russo-Polish War (1654–67)

{{Disambiguation ...

, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth controlled Moscow for two years, from 29 September 1610 to 6 November 1612.

1635

Sweden, weakened by involvement in the

Sweden, weakened by involvement in the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

, agreed to sign the Armistice of Stuhmsdorf (also known as Treaty of Sztumska Wieś or Treaty of Stuhmsdorf) in 1635, favourable to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in terms of territorial concessions.

1655

In the history of Poland and Lithuania,

In the history of Poland and Lithuania, the Deluge

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is the Hebrew version of the universal flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microc ...

refers to a series of wars in the mid-to-late 17th century that left the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in ruins. The Deluge refers to the Swedish invasion and occupation of the western half of Poland-Lithuania from 1655 to 1660 and the Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1648, which led to Russia's invasion during the

The Deluge refers to the Swedish invasion and occupation of the western half of Poland-Lithuania from 1655 to 1660 and the Khmelnytsky Uprising in 1648, which led to Russia's invasion during the Russo-Polish War

Armed conflicts between Poland (including the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) and Russia (including the Soviet Union) include:

Originally a Polish civil war that Russia, among others, became involved in.

Originally a Hungarian revolution ...

.

1657

The

The Treaty of Wehlau

The Treaty of Bromberg (, Latin: Pacta Bydgostensia) or Treaty of Bydgoszcz was a treaty between John II Casimir of Poland and Elector Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia that was ratified at Bromberg (Bydgoszcz) on 6 November 1657. The tr ...

was a treaty signed on September 19, 1657, in the eastern Prussian town of Wehlau (Welawa, now Znamensk

Znamensk (russian: Знаменск) is the name of several inhabited localities in Russia.

;Urban localities

* Znamensk, Astrakhan Oblast, a closed town in Astrakhan Oblast

;Rural localities

*Znamensk, Kaliningrad Oblast, a settlement in Znamen ...

) between Poland and Brandenburg-Prussia during the Swedish Deluge. The treaty granted independence to Prussia in recognition of its help against the Swedish forces during the Deluge.

1660

In the

In the Treaty of Oliva

The Treaty or Peace of Oliva of 23 April (OS)/3 May (NS) 1660Evans (2008), p.55 ( pl, Pokój Oliwski, sv, Freden i Oliva, german: Vertrag von Oliva) was one of the peace treaties ending the Second Northern War (1655-1660).Frost (2000), p.183 ...

, the Polish King, John II Casimir

John II Casimir ( pl, Jan II Kazimierz Waza; lt, Jonas Kazimieras Vaza; 22 March 1609 – 16 December 1672) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1648 until his abdication in 1668 as well as titular King of Sweden from 1648 ...

, renounced his claims to the Swedish crown, which his father Sigismund III Vasa

Sigismund III Vasa ( pl, Zygmunt III Waza, lt, Žygimantas Vaza; 20 June 1566 – 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden and Grand Duke of Finland from 1592 to ...

had lost in 1599. Poland formally ceded Swedish Livonia and the city of Riga, which had been under de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

Swedish control since the 1620s.

1667

The War for Ukraine ended with the

The War for Ukraine ended with the Treaty of Andrusovo

The Truce of Andrusovo ( pl, Rozejm w Andruszowie, russian: Андрусовское перемирие, ''Andrusovskoye Pieriemiriye'', also sometimes known as Treaty of Andrusovo) established a thirteen-and-a-half year truce, signed in 1667 bet ...

of January 13, 1667.Left-bank Ukraine

Left-bank Ukraine ( uk, Лівобережна Україна, translit=Livoberezhna Ukrayina; russian: Левобережная Украина, translit=Levoberezhnaya Ukraina; pl, Lewobrzeżna Ukraina) is a historic name of the part of Ukrain ...

with the Polish Commonwealth retaining Right-bank Ukraine.

1672

As a result of the Polish–Ottoman War the Polish commonwealth ceded

As a result of the Polish–Ottoman War the Polish commonwealth ceded Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

in the 1672 Treaty of Buczacz.

1686

The

The Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686

A Treaty of Perpetual Peace (also "Treaty of Eternal Peace" or simply Perpetual Peace, russian: Вечный мир, , pl, Pokój wieczysty, in Polish tradition Grzymułtowski Peace, pl, Pokój Grzymułtowskiego) between the Tsardom of Russia ...

was a treaty between the Tsardom of Russia

The Tsardom of Russia or Tsardom of Rus' also externally referenced as the Tsardom of Muscovy, was the centralized Russian state from the assumption of the title of Tsar by Ivan IV in 1547 until the foundation of the Russian Empire by Peter I ...

and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth signed on May 6, 1686, in Moscow. It confirmed the earlier Truce of Andrusovo of 1667. The treaty secured Russia's possession of the Left-bank Ukraine, Zaporozh'ye, Seversk lands, the cities of Chernihiv

Chernihiv ( uk, Черні́гів, , russian: Черни́гов, ; pl, Czernihów, ; la, Czernihovia), is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within ...

, Starodub

Starodub ( rus, links=no, Староду́б, p=stərɐˈdup, ''old oak'') is a town in Bryansk Oblast, Russia, on the Babinets River (the Dnieper basin), southwest of Bryansk. Population: 16,000 (1975).

History

Starodub has been known ...

, and Smolensk

Smolensk ( rus, Смоленск, p=smɐˈlʲensk, a=smolensk_ru.ogg) is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow. First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest ...

and its outskirts, while Poland retained Right-bank Ukraine.

1699

The

The Treaty of Karlowitz

The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in Karlowitz, Military Frontier of Archduchy of Austria (present-day Sremski Karlovci, Serbia), on 26 January 1699, concluding the Great Turkish War of 1683–1697 in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated by th ...

, or Treaty of Karlovci, was signed on January 26, 1699, in Sremski Karlovci, a town in modern-day Serbia. The Treaty of Karlowitz was signed following a two-month congress between the Ottoman Empire and the Holy League of 1684, a coalition of various European powers including the Habsburg Monarchy, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Republic of Venice, and the Russia of Peter I Alekseyevich.[pg 86 – ] The treaty concluded the Austro-Ottoman War of 1683–1697, in which the Ottoman side had finally been defeated at the Battle of Senta. The Ottomans ceded most of Hungary, Transylvania, and Slavonia to Austria while Podolia returned to Poland. Most of Dalmatia passed to Venice, along with the Morea (the Peloponnesus

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge whi ...

peninsula) and Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

.

1772

In February 1772, an agreement for the partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was signed in

In February 1772, an agreement for the partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was signed in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

.[Poland, Partitions of. (2008). '']Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

''. Retrieved April 28, 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9060581[pg 97 – ]

1793

By the 1790s the First Polish Republic had deteriorated into such a helpless condition that it was successfully forced into an alliance with its enemy, Prussia. The alliance was cemented with the Polish–Prussian Pact of 1790.

By the 1790s the First Polish Republic had deteriorated into such a helpless condition that it was successfully forced into an alliance with its enemy, Prussia. The alliance was cemented with the Polish–Prussian Pact of 1790.[pg 128 – pg 128 – ''The result was the March 1790 Polish–Prussian alliance ... Warsaw's viewpoint the alliance made sense, but the sejm's refusal to pay Prussia's price for it ... made it of problematic value.''] The conditions of the Pact were such that the succeeding and final two partitions of Poland were inevitable. The May Constitution of 1791 enfranchised the bourgeoisie, established the separation of the three branches of government, and eliminated the abuses of Repnin Sejm.

Those reforms prompted aggressive actions on the part of Poland's neighbours, wary of a potential renaissance of the Commonwealth. In the second partition, Russia and Prussia took so much territory that only one-third of the 1772 population remained in Poland.[pg 101–103 – - ''the Prussians and the Russians signed a second treaty of Partition in St Petersburg on 23 January 1793. Catherine would take a slab of land ... William would acquire a triangle of territory between Silesia and East Prussia.'']

1795

Kosciuszko's insurgent armies, who fought to regain Polish territory, won some initial successes but they eventually fell before the forces of the Russian Empire.

Kosciuszko's insurgent armies, who fought to regain Polish territory, won some initial successes but they eventually fell before the forces of the Russian Empire.

Partitioned Poland 1795 to 1918

Territorial changes during the time after the Partitions, starting with the Third Partition of Poland

The Third Partition of Poland (1795) was the last in a series of the Partitions of Poland–Lithuania and the land of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth among Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Russian Empire which effectively ended Polis ...

and ending with the creation of the Second Polish Republic.

1807

Duchy of Warsaw

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's attempts to build and expand his empire kept Europe at war for almost a decade and brought him into conflict with the same European powers that had beleaguered Poland in the last decades of the previous century. An alliance of convenience was the result of this situation. Volunteer Polish legions attached themselves to Bonaparte's armies, hoping that in return the emperor would allow an independent Poland to reappear out of his conquests.Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

was a Polish state established by Napoleon in 1807 from the Polish lands ceded by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. ...

under the terms of the Treaties of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when ...

. The duchy was held in personal union by one of Napoleon's allies, King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

.

Free City of Danzig (Napoleonic)

Prussia had acquired the City of Danzig in the course of the Second Partition of Poland

The 1793 Second Partition of Poland was the second of three partitions (or partial annexations) that ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. The second partition occurred in the aftermath of the Polish–Russian W ...

in 1793. After the defeat of King Frederick William III of Prussia at the 1806 Battle of Jena–Auerstedt, according to the Franco-Prussian Treaty of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when ...

of 9 July 1807, the territory of the free state was carved out from lands that made up part of the West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

province.

1809

In 1809, a short war with

In 1809, a short war with Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

started. Although the Duchy of Warsaw won the Battle of Raszyn

The first Battle of Raszyn was fought on 19 April 1809 between armies of the Austrian Empire under Archduke Ferdinand Karl Joseph of Austria-Este and the Duchy of Warsaw under Józef Antoni Poniatowski, as part of the War of the Fifth Coalitio ...

, Austrian troops entered Warsaw, but Duchy and French forces then outflanked their enemy and captured Cracow, Lwów and much of the areas annexed by Austria in the Partitions of Poland. After the Battle of Wagram, the ensuing Treaty of Schönbrunn

The Treaty of Schönbrunn (french: Traité de Schönbrunn; german: Friede von Schönbrunn), sometimes known as the Peace of Schönbrunn or Treaty of Vienna, was signed between France and Austria at Schönbrunn Palace near Vienna on 14 October ...

allowed for a significant expansion of the Duchy's territory southwards with the regaining of once-Polish and Lithuanian lands.

1815

Following Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia, the duchy was occupied by Prussian and Russian troops until 1815, when it was formally partitioned between the two countries at the

Following Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia, the duchy was occupied by Prussian and Russian troops until 1815, when it was formally partitioned between the two countries at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

.

Congress Poland

Congress Poland was created out of the Duchy of Warsaw at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, when European states reorganized Europe following the Napoleonic wars.

Grand Duchy of Posen

The Grand Duchy of Posen was a region in the Kingdom of Prussia in the Polish lands commonly known as "Greater Poland" between the years 1815–1848. According to the Congress of Vienna, it was to have autonomy. In practice, it was subordinated to Prussia and the proclaimed rights for Poles were not respected. The name was unofficially used afterwards for denoting the territory, especially by Poles, and today is used by modern historians to describe different political entities until 1918. Its capital was Posen (Polish: Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

).

Free City of Cracow

The Free, Independent, and Strictly Neutral City of Cracow with its Territory, more commonly known as either the Free City of Cracow or Republic of Cracow, was a city-state created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[pg 55 – ]

1831

After the November Uprising, Congress Poland lost its status as a sovereign state in 1831 and the administrative division of Congress Poland was reorganized. Russia issued an "organic decree" preserving the rights of individuals in Congress Poland but abolished the

After the November Uprising, Congress Poland lost its status as a sovereign state in 1831 and the administrative division of Congress Poland was reorganized. Russia issued an "organic decree" preserving the rights of individuals in Congress Poland but abolished the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland ( Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of ...

. This meant Poland was subject to rule by Russian military decree.[pg 65 – ]

1846

In the aftermath of the unsuccessful Cracow Uprising, the Free City of Cracow was annexed by the Austrian Empire.

In the aftermath of the unsuccessful Cracow Uprising, the Free City of Cracow was annexed by the Austrian Empire.

1848

After the defeat of Congress Poland, many Prussian liberals sympathised with the demand for the restoration of the Polish state. In the spring of 1848 the new liberal Prussian government allowed some autonomy to the Grand Duchy of Posen in the hope of contributing to the cause of a new Polish homeland.

After the defeat of Congress Poland, many Prussian liberals sympathised with the demand for the restoration of the Polish state. In the spring of 1848 the new liberal Prussian government allowed some autonomy to the Grand Duchy of Posen in the hope of contributing to the cause of a new Polish homeland.[pg 107 – ]

''Many Prussian liberals sympathised with the demand for the restoration of the Polish state. Since the defeat of the uprising of the 1830–31 in Congress Poland ... In the spring of 1848 the new liberal Prussian government allowed some autonomy to Posen in the hope of contributing to the cause of restoration.'' Due to a number of factors, including the outrage of the German-speaking minority in Posen, the Prussian government reversed course. By April 1848, the Prussian army had already suppressed the Polish militias and National Committees that emerged in March. By the end of the year the Duchy had lost the last vestiges of its formal autonomy, and was downgraded to a Province of the Prussian kingdom.[pg 178 -]

''April 1848 ... the Prussian army had already suppressed the rand Duchy of PosenPolish militias and National Committee which had emerged in March. After 1848 rand Duchy of Posenlost the last vestiges of its formal autonomy, and was downgraded to a mere Provinz of the Prussian kingdom...''

Second Polish Republic and occupation 1918 to 1945

Territorial changes during the Second Polish Republic and the joint German-Soviet occupation of Poland, starting with the formation of the Republic and ending with the end of the occupation.

1918

The

The West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (WUPR) or West Ukrainian National Republic (WUNR), known for part of its existence as the Western Oblast of the Ukrainian People's Republic, was a short-lived polity that controlled most of Eastern Gali ...

was proclaimed on November 1, 1918, with Lviv

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukrain ...

(Lwów) as its capital. The Ukrainian Republic claimed sovereignty over Eastern Galicia, including the Carpathians

The Carpathian Mountains or Carpathians () are a range of mountains forming an arc across Central Europe. Roughly long, it is the third-longest European mountain range after the Urals at and the Scandinavian Mountains at . The range stretches ...

up to the city of Nowy Sącz in the west (despite of Polish majority), as well as Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

and Bukovina. Although the majority of the population of the Western-Ukrainian People's Republic were Ukrainians, Poles and Jews, large parts of the claimed territory were considered Polish by the Poles. In Lwów (Lviv) the Ukrainian minority supported the proclamation, the city's significant Jewish minority accepted, remained neutral or had a negative attitude towards the Ukrainian proclamation, and the Polish majority was shocked to find themselves in a proclaimed Ukrainian state.[pg 367–368 – ] Due to the fact that Poles constituted over 60% of Lviv's inhabitants, almost 30% Jews, and Ukrainians below 10%, the vast majority of the city's inhabitants were against the fact that Lviv belonged to Ukraine and they wanted it to belong to Poland again.

1919

Recreation of Poland

In the aftermath of World War I, the Polish people rose up in the Greater Poland Uprising on December 27, 1918, in

In the aftermath of World War I, the Polish people rose up in the Greater Poland Uprising on December 27, 1918, in Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint Joh ...

after a patriotic speech by Ignacy Paderewski

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (; – 29 June 1941) was a Polish pianist and composer who became a spokesman for Polish independence. In 1919, he was the new nation's Prime Minister and foreign minister during which he signed the Treaty of Versaill ...

, a famous Polish pianist. The fighting continued until June 28, 1919, when the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

was signed, which recreated the nation of Poland. From the defeated German Empire, Poland received the following:

* Most of the Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

province of Posen was granted to Poland. This territory had already been taken over by local Polish insurgents during the Great Poland Uprising of 1918–1919.[pg 178 – ]

* 70% of West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

was given to Poland to provide free access to the sea, along with a 10% German minority, creating the Polish corridor

The Polish Corridor (german: Polnischer Korridor; pl, Pomorze, Polski Korytarz), also known as the Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia (Pomeranian Voivodeship, easter ...

.[pg 44 – ]

* The east part of Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

was awarded to Poland after a plebiscite. Sixty percent of residents voted for German citizenship, and 40 percent for Poland; as a result the area was divided.Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, the area of Działdowo

Działdowo (german: Soldau) (Old Prussian: Saldawa) is a town in northern Poland with 20,935 inhabitants as of December 2021, the capital of Działdowo County. As part of Masuria, it is situated in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (since 1999), D ...

(Soldau) in East Prussia was granted to the new Polish state.Warmia

Warmia ( pl, Warmia; Latin: ''Varmia'', ''Warmia''; ; Warmian: ''Warńija''; lt, Varmė; Old Prussian: ''Wārmi'') is both a historical and an ethnographic region in northern Poland, forming part of historical Prussia. Its historic capital ...

and Masuria

Masuria (, german: Masuren, Masurian: ''Mazurÿ'') is a ethnographic and geographic region in northern and northeastern Poland, known for its 2,000 lakes. Masuria occupies much of the Masurian Lake District. Administratively, it is part of the ...

, a small area was granted to Poland.

Dec3-5, 1918 Provincial Seym in Poznań of 1403 deputies from Gdańsk-Pomerania, Warmia, Mazuria, Silesia, Poznania, and German areas populated by Poles; appointing a Supreme People's Council; demands that the Western Allies incorporate into Poland all of the lands annexed by Prussia in the partitions.

Feb. 3, 1919 Signing in Paris of Polish–Czech border agreement on the basis o Nov. 5, 1918, ethnic division agreement.

June 25, 1919, Supreme Allies Council transferring East Galicia to Poland...

July 11, 1920, British anti-Polish decisions in the plebiscite in East Prussia (Powisle, Warmia, and Mazuria) during Soviet offensive towards Warsaw...

July 28, 1920, Allied ambassadors decision partitioning Cieszyn, Silesia, and leaving in Czechoslovakia a quarter of a million Poles in the strategic Moravian Gate...(leading to Poland from south-west)

Poland seizes West Ukrainian People's Republic

On July 17, 1919, a ceasefire was signed in the

On July 17, 1919, a ceasefire was signed in the Polish–Ukrainian War

The Polish–Ukrainian War, from November 1918 to July 1919, was a conflict between the Second Polish Republic and Ukrainian forces (both the West Ukrainian People's Republic and Ukrainian People's Republic). The conflict had its roots in ethn ...

with the West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (WUPR) or West Ukrainian National Republic (WUNR), known for part of its existence as the Western Oblast of the Ukrainian People's Republic, was a short-lived polity that controlled most of Eastern Gali ...

(ZUNR). As part of the agreement Poland kept ZUNR territory. The West Ukrainian People's Republic then merged with the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

(UNR).

Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (Polish–Bolshevik War, Polish–Soviet War, Polish–Russian War 1919–1921)

* russian: Советско-польская война (''Sovetsko-polskaya voyna'', Soviet-Polish War), Польский фронт (' ...

(February 1919 – March 1921) was an armed conflict between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine on the one hand and the Second Polish Republic and the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

on the other. The war was the result of conflicting expansionist ambitions. Poland, whose statehood had just been re-established by the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

following the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century, sought to secure territories it had lost at the time of the partitions. The aim of the Soviet states was to control those same territories, which the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

had gained in the partitions of Poland.[Chapter "The Russo-Polish War" – ]

File:PBW March 1919.svg, March 1919

File:PBW December 1919.png, December 1919

File:PBW June 1920.png, June 1920

File:PBW August 1920.png, August 1920

File:Rzeczpospolita 1937.svg, Treaty of Riga

1920

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk) was created on 15 November 1920 in accordance with the terms of Article 100 (Section XI of Part III) of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles