Territorial claims in the Arctic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

''

''

UN mirror

/ref>Ramskov, Jens.

Derfor gør Danmark nu krav på NordpolenIn English

''

On August 2, 2007, a Russian expedition called Arktika 2007, composed of six explorers led by

On August 2, 2007, a Russian expedition called Arktika 2007, composed of six explorers led by

Hans Island is situated in the

Hans Island is situated in the

There is an ongoing dispute involving a wedge-shaped slice on the

There is an ongoing dispute involving a wedge-shaped slice on the

No settlement has been reached to date because the U.S. has signed but has not ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). If the treaty is ratified, the issue would likely be settled at a bilateral negotiation. On August 20, 2009

The legal status of the Northwest Passage is disputed: Canada considers it to be part of its internal waters according to the UNCLOS. The United States and most maritime nations consider them to be an international strait, which means that foreign vessels have right of "transit passage". In such a regime, Canada would have the right to enact fishing and environmental regulation, and fiscal and smuggling laws, as well as laws intended for the safety of shipping, but not the right to close the passage. In addition, the environmental regulations allowed under the UNCLOS are not as robust as those allowed if the Northwest Passage is part of Canada's internal waters.

The legal status of the Northwest Passage is disputed: Canada considers it to be part of its internal waters according to the UNCLOS. The United States and most maritime nations consider them to be an international strait, which means that foreign vessels have right of "transit passage". In such a regime, Canada would have the right to enact fishing and environmental regulation, and fiscal and smuggling laws, as well as laws intended for the safety of shipping, but not the right to close the passage. In addition, the environmental regulations allowed under the UNCLOS are not as robust as those allowed if the Northwest Passage is part of Canada's internal waters.

online

* Byers, Michael. ''Who owns the Arctic?: Understanding sovereignty disputes in the North'' (Douglas & McIntyre, 2010). * Coates, Ken S., et al. ''Arctic front: defending Canada in the far north'' (Dundurn, 2010). * Dodds, Klaus, and Mark Nuttall. ''The Arctic: What Everyone Needs to Know'' (Oxford University Press, 2019). * Dodds, Klaus. ''The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction'' (Oxford University Press, 2012). * Griffiths, Franklyn, Rob Huebert, and P. Whitney Lackenbauer. ''Canada and the changing Arctic: Sovereignty, security, and stewardship'' (Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, 2011). * Jensen, Leif Christian, and Geir Hønneland, eds. ''Handbook of the Politics of the Arctic'' (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015). * Keil, Kathrin. "The Arctic: A new region of conflict? The case of oil and gas." ''Cooperation and conflict'' 49.2 (2014): 162–190. * Knecht, Sebastian, and Kathrin Keil. "Arctic geopolitics revisited: spatialising governance in the circumpolar North." ''The Polar Journal'' 3.1 (2013): 178–203. * Ladies, Przemysław. "The United States and Canada towards Russian Arctic Policy: State of Play and Development Prospects." ''Society and Politics'' 2 (63) (2020): 73–103

online

* McCormack, Michael. "More than Words: Securitization and Policymaking in the Canadian Arctic under Stephen Harper," ''American Review of Canadian Studies'' (2020) 50#4 pp 436–460. * Roberts, Kari. "Understanding Russia's security priorities in the Arctic: why Canada-Russia cooperation is still possible." ''Canadian Foreign Policy Journal'' (2020): 1–17. * Tamnes, Rolf, and Kristine Offerdal, eds. ''Geopolitics and Security in the Arctic: Regional dynamics in a global world'' (Routledge, 2014). * Wallace, Ron R. "Canada and Russia in an Evolving Circumpolar Arctic." in ''The Palgrave Handbook of Arctic Policy and Politics'' (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020) pp. 351–372

online

b

Donald M. McRae

entitled ''Selected Issues Relating to the Arctic'' in th

* van Efferink, Leonhardt

[https://web.archive.org/web/20141218020702/http://www.exploringgeopolitics.org/Publication_Efferink_van_Leonhardt_Arctic_Geopolitics_Russian_Territorial_Claims_UNCLOS_Lomonosov_Ridge_Exclusive_Economic_Zones_Baselines_Flag_Planting_North_Pole_Navy.html Arctic Geopolitics 2 – Russia's territorial claims, UNCLOS, the Lomonosov Ridge]

Frozen Assetsarchive

''The historical and legal background of Canada's Arctic claims'' (1952) Manuscript

at Dartmouth College Library

''Territorial sovereignty in the Arctic'' (1947) Manuscript

at Dartmouth College Library {{Energy in Russia * Territorial disputes of Canada Territorial disputes of Denmark Territorial disputes of Norway Territorial disputes of Russia International territorial disputes of the United States Multilateral relations of Russia Canada–Russia relations Canada–United States relations Canada–United States border disputes Russia–United States relations

The

The Arctic

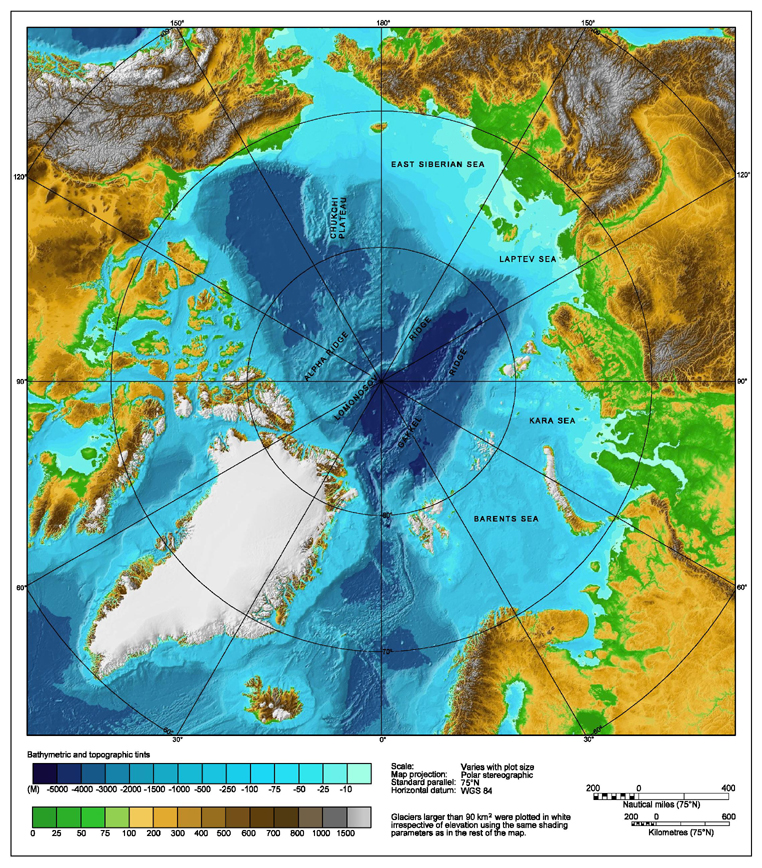

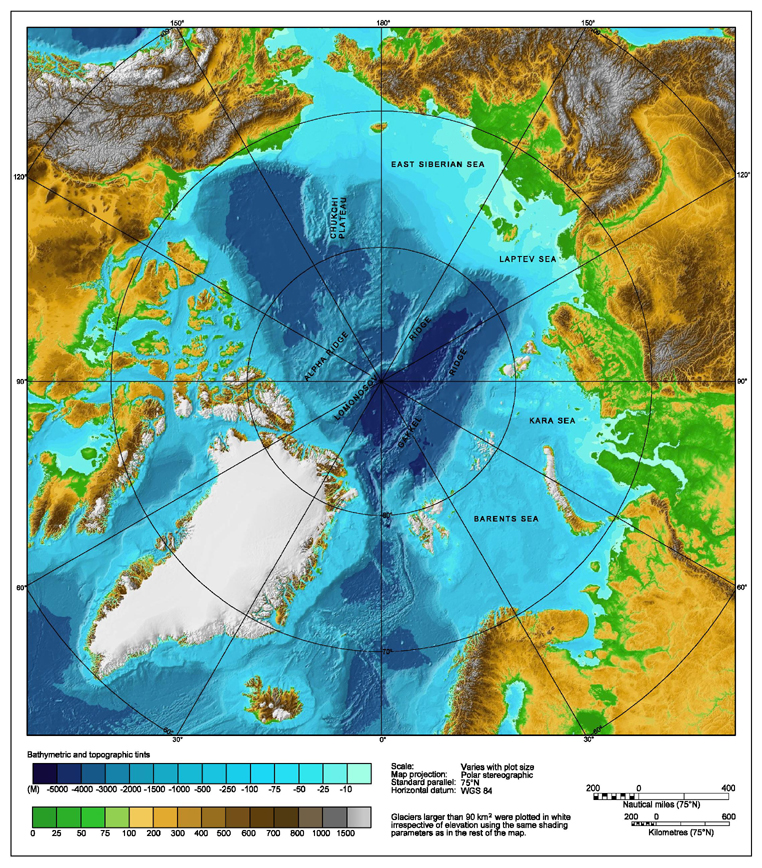

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

consists of land, internal waters

According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a nation's internal waters include waters on the side of the baseline of a nation's territorial waters that is facing toward the land, except in archipelagic states. It includes wat ...

, territorial seas, exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and international waters

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed region ...

above the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at ...

(66 degrees 33 minutes North latitude). All land, internal waters, territorial seas and EEZs in the Arctic are under the jurisdiction of one of the eight Arctic coastal states: Canada, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

(via Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States. International law regulates this area as with other portions of Earth.

Under international law, the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

and the region of the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

surrounding it are not owned by any country. The five surrounding Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

countries are limited to a territorial sea of and an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of adjacent to their coasts measured from declared baselines filed with the UN. The waters beyond the territorial seas of the coastal states are considered the "high seas" (i.e. international waters). The waters and sea bottom that is not confirmed to be extended continental shelf beyond the exclusive economic zones are considered to be the "heritage of all mankind." Fisheries in these waters can only be limited by international treaty and exploration and exploitation of mineral resources on and below the seabed in these areas is administered by the UN International Seabed Authority

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) (french: Autorité internationale des fonds marins) is a Kingston, Jamaica-based intergovernmental body of 167 member states and the European Union established under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of ...

.

Upon ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international agreement that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , 167 ...

(UNCLOS), a country has a ten-year period to make claims to an extended continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

which, if validated, gives it exclusive rights to resources on or below the seabed of that extended shelf area. Norway, Russia, Canada, and Denmark launched projects to provide a basis for seabed claims on extended continental shelves beyond their exclusive economic zones. The United States has signed, but not yet ratified the UNCLOS.

The status of certain portions of the Arctic sea region is in dispute for various reasons. Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States all regard parts of the Arctic seas as national waters (territorial waters

The term territorial waters is sometimes used informally to refer to any area of water over which a sovereign state has jurisdiction, including internal waters, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone, and potent ...

out to ) or internal waters

According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a nation's internal waters include waters on the side of the baseline of a nation's territorial waters that is facing toward the land, except in archipelagic states. It includes wat ...

. There also are disputes regarding what passages constitute international seaways and rights to passage along them. There was one single disputed piece of land in the Arctic—Hans Island

Hans Island ( Inuktitut and kl, Tartupaluk, ; Inuktitut syllabics: ; da, Hans Ø; french: Île Hans) is an island in the very centre of the Kennedy Channel of Nares Strait in the high Arctic region, split between the Canadian territory of ...

—which was disputed until 2022 between Canada and Denmark because of its location in the middle of a strait.

North Pole and the Arctic Ocean

National sectors: 1925–2005

In 1925, based upon the Sector Principle, Canada became the first country to extend itsmaritime boundaries

A maritime boundary is a conceptual division of the Earth's water surface areas using physiographic or geopolitical criteria. As such, it usually bounds areas of exclusive national rights over mineral and biological resources,VLIZ Maritime Bound ...

northward to the North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

, at least on paper, between 60°W and 141°W longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek let ...

, a claim that is not universally recognized (there are of ocean between the Pole and Canada's northernmost land point).T. E. M. McKitterick, "The Validity of Territorial and Other Claims in Polar Regions," ''Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law,'' 3rd Ser., Vol. 21, No. 1. (1939), pp. 89–97. On April 15 the following year, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (russian: Президиум Верховного Совета, Prezidium Verkhovnogo Soveta) was a body of state power in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nati ...

declared the territory between two lines (32°04′35″E to 168°49′30″W) drawn from west of Murmansk to the North Pole and from the eastern Chukchi Peninsula

The Chukchi Peninsula (also Chukotka Peninsula or Chukotski Peninsula; russian: Чуко́тский полуо́стров, ''Chukotskiy poluostrov'', short form russian: Чуко́тка, ''Chukotka''), at about 66° N 172° W, is the eastern ...

to the North Pole to be Soviet territory. Norway (5°E to 35°E) made similar sector claims, as did the United States (170°W to 141°W), but that sector contained only a few islands, so the claim was not pressed. Denmark's sovereignty over all of Greenland was recognized by the United States in 1916 and by an international court in 1933. Denmark could also conceivably claim an Arctic sector (60°W to 10°W).

In the context of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, Canada sent Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

families to the far north in the High Arctic relocation, partly to establish territoriality. The Canadian monarch, Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states durin ...

, accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms. He was the longest-serving heir apparent and Prince of Wales and, at age 73, became the oldest person to a ...

, and Princess Anne

Anne, Princess Royal (Anne Elizabeth Alice Louise; born 15 August 1950), is a member of the British royal family. She is the second child and only daughter of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the only sister of ...

, undertook in 1970 a tour of Northern Canada

Northern Canada, colloquially the North or the Territories, is the vast northernmost region of Canada variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories an ...

, in part to demonstrate to an unconvinced American government and the Soviet Union that Canada had certain claim to its Arctic territories, which were strategic during the Cold War. In addition, Canada claims the water within the Canadian Arctic Archipelago as its own internal waters. The United States is one of the countries which does not recognize Canada's, or any other countries', Arctic archipelagic water claims and has allegedly sent nuclear submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s under the ice near Canadian islands without requesting permission.

Until 1999, the geographic North Pole (a non-dimensional dot) and the major part of the Arctic Ocean had been generally considered to comprise international space, including both the waters and the sea bottom. However, the adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) has prescribed a process which prompted several countries to submit claims or to reinforce pre-existing claims to portions of the seabed of the polar region.

Extended Continental Shelf Claims: 2006–present

Overview

As defined by the UNCLOS, states have ten years from the date of ratification to make claims to an extended continental shelf. They must present to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, a UN body, geological evidence that their shelf effectively extends beyond the 200 nautical miles limit. The Commission does not define borders but merely judges the scientific validity of assertions and it is up to countries with rightful but overlapping claims to come to a settlement. On this basis, four of the five states fronting the Arctic Ocean – Canada, Denmark, Norway, and the Russian Federation – must have made any desired claims by 2013, 2014, 2006, and 2007 respectively. Since the U.S. has yet to ratify the UNCLOS, the date for its submission is undetermined at this time. Claims to extended continental shelves, if deemed valid, give the claimant state exclusive rights to the sea bottom and resources below the bottom. Valid extended continental shelf claims do not and cannot extend a state's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) since the EEZ is determined solely by drawing a line using territorial sea baselines as their starting point. Press reports often confuse the facts and assert that extended continental shelf claims expand a state's EEZ thereby giving a state exclusive rights to resources not only on the sea bottom or below it, but also to those in the water column above it. The Arctic chart prepared by Durham University explicitly illustrates the extent of the uncontested Exclusive Economic Zones of the five states bordering the Arctic Ocean, and also the relatively small expanse of remaining "high seas" or totally international waters at the very North of the planet.Specific nations

=Canada

= Canada ratified UNCLOS on 7 November 2003 and had through 2013 to file its claim to an extended continental shelf. , Canada had announced that it would file a claim which includes theNorth Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

. Canada planned to submit their claim to a portion of the Arctic continental shelf in 2018.

In response to the Russian Arktika 2007 expedition, Canada's Foreign Affairs Minister, Peter MacKay

Peter Gordon MacKay (born September 27, 1965) is a Canadian lawyer and politician. He was a Member of Parliament from 1997 to 2015 and has served as Minister of Justice and Attorney General (2013–2015), Minister of National Defence (2007� ...

, said " is is posturing. This is the true North, strong and free, and they're fooling themselves if they think dropping a flag on the ocean floor is going to change anything... This isn't the 14th or 15th century." In response, Sergey Lavrov

Sergey Viktorovich Lavrov (russian: Сергей Викторович Лавров, ; born 21 March 1950) is a Russian diplomat and politician who has served as the Foreign Minister of Russia since 2004.

Lavrov served as the Permanent Represe ...

, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

, stated " en pioneers reach a point hitherto unexplored by anybody, it is customary to leave flags there. Such was the case on the Moon, by the way... from the outset said that this expedition was part of the big work being carried out under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, within the international authority where Russia's claim to submerged ridges which we believe to be an extension of our shelf is being considered. We know that this has to be proved. The ground samples that were taken will serve the work to prepare that evidence."

On 25 September 2007, Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Stephen Harper

Stephen Joseph Harper (born April 30, 1959) is a Canadian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Canada from 2006 to 2015. Harper is the first and only prime minister to come from the modern-day Conservative Party of Canada, ...

said he was assured by Russian President Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

that neither offence nor "violation of international understanding or any Canadian sovereignty" was intended. Harper promised to defend Canada's claimed sovereignty by building and operating up to eight Arctic patrol ships, a new army training centre in Resolute Bay

Resolute Bay is an Arctic waterway in the Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located in Parry Channel on the southern side of Cornwallis Island. The hamlet of Resolute is located on the northern shore of the bay with Resolute Bay Airpo ...

, and the refurbishing of an existing deepwater port at a former mining site in Nanisivik

Nanisivik ( iu, ᓇᓂᓯᕕᒃ, lit=the place where people find things; ) is a now-abandoned company town which was built in 1975 to support the lead-zinc mining and mineral processing operations for the Nanisivik Mine, in production between 19 ...

.

=Denmark

= Denmark ratified UNCLOS on 16 November 2004 and had through 2014 to file a claim to an extended continental shelf. The Kingdom of Denmark simultaneously declared that ratifying UNCLOS did not change Denmark's position that theDanish straits

The Danish straits are the straits connecting the Baltic Sea to the North Sea through the Kattegat and Skagerrak. Historically, the Danish straits were internal waterways of Denmark; however, following territorial losses, Øresund and Fehmarn B ...

including the Great Belt

The Great Belt ( da, Storebælt, ) is a strait between the major islands of Zealand (''Sjælland'') and Funen (''Fyn'') in Denmark. It is one of the three Danish Straits.

Effectively dividing Denmark in two, the Belt was served by the Great B ...

, the Little Belt

The Little Belt (, ) is a strait between the island of Funen and the Jutland Peninsula in Denmark. It is one of the three Danish Straits that drain and connect the Baltic Sea to the Kattegat strait, which drains west to the North Sea and Atla ...

, and the Danish part of Øresund

Øresund or Öresund (, ; da, Øresund ; sv, Öresund ), commonly known in English as the Sound, is a strait which forms the Danish–Swedish border, separating Zealand (Denmark) from Scania (Sweden). The strait has a length of ; its width ...

, formed on the foundation of the Copenhagen Treaty of 1857 are legally Danish territory, and – as set out in the treaty section of the United Nations Office of Legal Affairs

The United Nations Office of Legal Affairs is a United Nations office currently administered by Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs and Legal Counsel of the United Nations Miguel de Serpa Soares.

History

Established in 1946, the United ...

– this should remain so. Consequently, Denmark considers the Copenhagen Convention to apply solely to the waterways through Denmark proper and not the North Atlantic.

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

, an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, has the nearest coastline to the North Pole, and Denmark argues that the Lomonosov Ridge

The Lomonosov Ridge (russian: Хребет Ломоносова, da, Lomonosovryggen) is an unusual underwater ridge of continental crust in the Arctic Ocean. It spans between the New Siberian Islands over the central part of the ocean to Ell ...

is in fact an extension of Greenland. Danish project included LORITA-1 expedition in April–May 2006 and included tectonic research during LOMROG expedition, which were part of the 2007–2008 International Polar Year program. It comprised the Swedish icebreaker

An icebreaker is a special-purpose ship or boat designed to move and navigate through ice-covered waters, and provide safe waterways for other boats and ships. Although the term usually refers to ice-breaking ships, it may also refer to smaller ...

''Oden

is a type of nabemono (Japanese one-pot dishes), consisting of several ingredients such as boiled eggs, daikon, konjac, and processed fishcakes stewed in a light, soy-flavored dashi broth.

Oden was originally what is now commonly ca ...

'' and Russian nuclear icebreaker NS ''50 Let Pobedy''. The latter led the expedition through the ice fields to the research location. Further efforts at geological study in the region were carried out by the LOMROG II expedition, which took place in 2009, and the LOMROG III expedition, launched in 2012.

On 14 December 2014 Denmark claimed an area of extending from Greenland past the North Pole to the limits of the Russian Exclusive Economic Zone. Unlike the Russian claim which is generally limited to the Russia sector of the Arctic, the Danish Claim extends across the North Pole and into Russia's sector.Submission by the Kingdom of Denmark''

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an international agreement that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , 167 ...

'', 15 December 2014. Accessed: 15 December 2014.The Northern Continental Shelf of Greenland (Executive Summary)''

Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland

The Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland ( da, Danmarks og Grønlands Geologiske Undersøgelse, GEUS) is the independent sector research institute under the Danish Ministry of Climate and Energy. GEUS is an advisory, research and survey i ...

/ Ministry of Climate, Energy and Building (Denmark)'', November 2014. Accessed: 15 December 2014. Size: 52 pages in 6MBUN mirror

/ref>Ramskov, Jens.

Derfor gør Danmark nu krav på Nordpolen

''

Ingeniøren

''Ingeniøren'' (full name: ''Nyhedsmagasinet Ingeniøren'', literally ''The News Magazine "The Engineer"'') is a Danish weekly newspaper specialising in engineering topics.

History and profile

The paper has covered science and technology issues ...

'', 15 December 2014. Accessed: 15 December 2014.=Norway

= Norway ratified the UNCLOS on 24 June 1996 and had through 2006 to file a claim to an extended continental shelf. On November 27, 2006, Norway made an official submission into the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (article 76, paragraph 8). There are provided arguments to extend the Norwegian seabed claim beyond the EEZ in three areas of the northeasternAtlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and the Arctic: the "Loop Hole" in the Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; no, Barentshavet, ; russian: Баренцево море, Barentsevo More) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian terr ...

, the Western Nansen Basin in the Arctic Ocean, and the "Banana Hole" in the Norwegian Sea. The submission also states that an additional submission for continental shelf limits in other areas may be posted later.

Norway and Russia have ratified an agreement on the Barents Sea, ending a 40-year demarcation dispute.

=Russia

= Russia ratified the UNCLOS in 1997 and had through 2007 to file a claim to an extended continental shelf. TheRussian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

is claiming a large extended continental shelf as far as the North Pole based on the Lomonosov Ridge

The Lomonosov Ridge (russian: Хребет Ломоносова, da, Lomonosovryggen) is an unusual underwater ridge of continental crust in the Arctic Ocean. It spans between the New Siberian Islands over the central part of the ocean to Ell ...

and Mendeleyev Ridges within their Arctic sector. Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

believes the eastern Lomonosov Ridge and the Mendeleyev Ridge are an extension of the Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

n continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

. Until Denmark filed its claim, the Russian claim did not cross the Russia-US Arctic sector demarcation line, nor did it extend into the Arctic sector of any other Arctic coastal state.

On December 20, 2001, Russia made an official submission into the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (article 76, paragraph 8). In the document it is proposed to establish the outer limits of the continental shelf of Russia

The continental shelf of Russia (also called the Russian continental shelf or the Arctic shelf in the Arctic region) is a continental shelf adjacent to the Russian Federation. Geologically, the extent of the shelf is defined as the entirety of the ...

beyond the Exclusive Economic Zone, but within the Russian Arctic sector. The territory claimed by Russia in the submission is a large portion of the Arctic within its sector, extending to but not beyond the geographic North Pole. One of the arguments was a statement that Lomonosov Ridge, an underwater mountain ridge passing near the Pole, and Mendeleev Ridge on the Russian side of the Pole are extensions of the Eurasian continent. In 2002 the UN Commission neither rejected nor accepted the Russian proposal, recommending additional research.

On August 2, 2007, a Russian expedition called Arktika 2007, composed of six explorers led by

On August 2, 2007, a Russian expedition called Arktika 2007, composed of six explorers led by Artur Chilingarov

Artur Nikolayevich Chilingarov (russian: Артур Николаевич Чилингаров; born 25 September 1939) is an Armenian-Russian polar explorer. He is a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, he was awarded the t ...

, employing MIR submersibles, for the first time in history descended to the seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most o ...

at the North Pole. There they planted a Russian flag and took water and soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former ...

samples for analysis, continuing a mission to provide additional evidence related to the Russian extended continental shelf claim including the mineral riches of the Arctic. This was part of the ongoing 2007 Russian North Pole expedition within the program of the 2007–2008 International Polar Year

The International Polar Years (IPY) are collaborative, international efforts with intensive research focus on the polar regions. Karl Weyprecht, an Austro-Hungarian naval officer, motivated the endeavor in 1875, but died before it first occurred i ...

.

The expedition aimed to establish that the eastern section of seabed passing close to the Pole, known as the Lomonosov and Mendeleyev Ridges, is in fact an extension of Russia's landmass. The expedition came as several countries are trying to extend their rights over sections of the Arctic Ocean floor. Both Norway and Denmark are carrying out surveys to this end. Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

made a speech on a nuclear icebreaker on 3 May 2007, urging greater efforts to secure Russia's "strategic, economic, scientific and defense interests" in the Arctic.

In mid-September 2007, Russia's Natural Resources Ministry issued a statement:

Viktor Posyolov, an official with Russia's Agency for Management of Mineral Resources:

On August 4, 2015, Russia submitted additional data in support of its bid, containing new arguments based on "ample scientific data collected in years of Arctic research", for territories in the Arctic to the United Nations. Through this bid, Russia is claiming 1.2 million square kilometers (over 463,000 square miles) of Arctic sea shelf extending more than 350 nautical miles (about 650 kilometers) from the shore.

In February 2016 additional data was submitted by Russian Minister of Natural Resources and Environment Sergey Donskoy. After the expedition " Arktika 2007" Russian researchers collected new data reinforcing Russia's claim to part of the sea bottom beyond its uncontested 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) within its Arctic sector, the North Pole area included. On August 9, 2016, the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf began its review of the submission.

=United States

= , the United States has not ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea ( UNCLOS) and, therefore, is not yet eligible to file an official claim to an extended continental shelf with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. In August 2007, an AmericanCoast Guard

A coast guard or coastguard is a maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with customs and security duties to ...

icebreaker, the USCGC ''Healy'', headed to the Arctic Ocean to map the sea floor off Alaska. Larry Mayer, director of the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping at the University of New Hampshire

The University of New Hampshire (UNH) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Durham, New Hampshire. It was founded and incorporated in 1866 as a land grant college in Hanover in connection with Dartmouth College ...

, stated the trip had been planned for months, having nothing to do with the Russians planting their flag. The purpose of the mapping work aboard the ''Healy'' is to determine the extent of the US continental shelf north of Alaska.

Future

It was stated by theIntergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an intergovernmental body of the United Nations. Its job is to advance scientific knowledge about climate change caused by human activities. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) ...

on March 25, 2007, that riches are awaiting the shipping industry due to Arctic climate change. This economic sector could be transformed similar to the way the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

was by the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popula ...

in the 19th century. There will be a race among nations for oil, fish, diamonds and shipping routes, accelerated by the impact of global warming.

The potential value of the North Pole and the surrounding area resides not so much in shipping itself but in the possibility that lucrative petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crud ...

and natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbon d ...

reserves exist below the sea floor. Such reserves are known to exist under the Barents, Kara, and Beaufort Seas. However, the vast majority of the Arctic known to contain gas and oil resources is already within uncontested EEZs. When these current uncontested Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) of the Arctic littoral states are taken into account there is only a small unclaimed area at the very top subject to the International Seabed Treaty potentially available for open gas/oil exploration.

On September 14, 2007, the European Space Agency

, owners =

, headquarters = Paris, Île-de-France, France

, coordinates =

, spaceport = Guiana Space Centre

, seal = File:ESA emblem seal.png

, seal_size = 130px

, image = Views in the Main Control Room (120 ...

reported ice loss had opened up the Northwest Passage "for the first time since records began in 1978", and the extreme loss in 2007 rendered the passage "fully navigable". Further exploration for petroleum reserves elsewhere in the Arctic may now become more feasible, and the passage may become a regular channel of international shipping and commerce if Canada is not able to enforce its claim to it.

Foreign Ministers and other officials representing Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States met in Ilulissat, Greenland in May 2008, at the Arctic Ocean Conference

The inaugural Arctic Ocean Conference was held in Ilulissat (Greenland) on 27-29 May 2008. Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia and the United States discussed key issues relating to the Arctic Ocean.Office The meeting was significant because of its pla ...

and announced the Ilulissat Declaration

The Ilulissat Declaration was brought into force on May 28, 2008 by the five coastal states of the Arctic Ocean (the United States, the Russian Federation, Canada, Norway and Denmark - also known as the Arctic five, aka the A5), following the Arct ...

. Among other things the declaration stated that any demarcation issues in the Arctic should be resolved on a bilateral basis between contesting parties.

Hans Island

Hans Island is situated in the

Hans Island is situated in the Nares Strait

, other_name =

, image = Map indicating Nares Strait.png

, alt =

, caption = Nares Strait (boxed) is between Ellesmere Island and Greenland.

, image_bathymetry =

, alt_bathymetry ...

, a waterway

A waterway is any navigable body of water. Broad distinctions are useful to avoid ambiguity, and disambiguation will be of varying importance depending on the nuance of the equivalent word in other languages. A first distinction is necessary ...

that runs between Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island ( iu, script=Latn, Umingmak Nuna, lit=land of muskoxen; french: île d'Ellesmere) is Canada's northernmost and third largest island, and the tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Br ...

(the northernmost part of Nunavut

Nunavut ( , ; iu, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ , ; ) is the largest and northernmost territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the '' Nunavut Act'' and the '' Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act'' ...

, Canada) and Greenland. The small uninhabited island, sized , was named for Greenlandic Arctic traveller Hans Hendrik.

In 1973, Canada and Denmark negotiated the geographic coordinates of the continental shelf, and settled on a delimitation treaty that was ratified by the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoni ...

on December 17, 1973, and has been in force since March 13, 1974. The treaty lists 127 points (by latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north ...

and longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek let ...

) from Davis Strait

Davis Strait is a northern arm of the Atlantic Ocean that lies north of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. To the north is Baffin Bay. The strait was named for the English explorer John ...

to the end of Robeson Channel

Robeson Channel () is a body of water lying between Greenland and Canada's northernmost island, Ellesmere Island. It is the most northerly part of Nares Strait, linking Hall Basin to the south with the Arctic Ocean to the north. The Newman Fjord ...

, where Nares Strait runs into Lincoln Sea; the border is defined by geodesic

In geometry, a geodesic () is a curve representing in some sense the shortest path ( arc) between two points in a surface, or more generally in a Riemannian manifold. The term also has meaning in any differentiable manifold with a connecti ...

lines between these points. The treaty does not, however, draw a line from point 122 () to point 123 ()—a distance of . Hans Island is situated in the centre of this area.

Danish flags were planted on Hans Island in 1984, 1988, 1995 and 2003. The Canadian government formally protested these actions. In July 2005, former Canadian defence minister Bill Graham made an unannounced stop on Hans Island during a trip to the Arctic; this launched yet another diplomatic quarrel between the governments, and a truce was called that September.

Canada had claimed Hans Island was clearly in its territory, as topographic maps originally used in 1967 to determine the island's coordinates clearly showed the entire island on Canada's side of the delimitation line. However, federal officials reviewed the latest satellite imagery in July 2007, and conceded that the line went roughly through the middle of the island. This presently leaves ownership of the island disputed, with claims over fishing grounds and future access to the Northwest Passage possibly at stake as well.

As of April 2012, the governments of both countries are in negotiations which may ultimately result in the island being split almost precisely in half. The negotiations ended in November 2012 and gave a more exact border description, but did not solve the dispute over Hans Island. One possible resolution would be to treat the island as a condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

.

In 2022, Canada and Denmark resolved the dispute, establishing a land border through Hans Island.

Beaufort Sea

There is an ongoing dispute involving a wedge-shaped slice on the

There is an ongoing dispute involving a wedge-shaped slice on the International Boundary

Borders are usually defined as geographical boundaries, imposed either by features such as oceans and terrain, or by political entities such as governments, sovereign states, federated states, and other subnational entities. Political borders ca ...

in the Beaufort Sea

The Beaufort Sea (; french: Mer de Beaufort, Iñupiaq: ''Taġiuq'') is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located north of the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, and Alaska, and west of Canada's Arctic islands. The sea is named after Sir ...

, between the Canadian territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

of Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

and the American state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

of Alaska.

The Canadian position is that the maritime boundary should extend the land boundary in a straight line. The American position is that the maritime boundary should extend along a path equidistant from the coasts of the two nations. The disputed area may hold significant hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ...

reserves. The U.S. has already leased eight plots of the terrain below the water to search for and possibly bring to market oil reserves

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturate ...

that may exist there. Canada has protested diplomatically in response.Sea ChangesNo settlement has been reached to date because the U.S. has signed but has not ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). If the treaty is ratified, the issue would likely be settled at a bilateral negotiation. On August 20, 2009

United States Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

Gary Locke

Gary Faye Locke (born January 21, 1950) is an American politician and diplomat serving as the interim president of Bellevue College, the largest of the institutions that make up the Washington Community and Technical Colleges system. Locke se ...

announced a moratorium on fishing the Beaufort Sea north of Alaska, including the disputed waters.

Randy Boswell, of ''Canada.com'' wrote that the disputed area covered a section of the Beaufort Sea (smaller than Israel, larger than El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south ...

).

He wrote that Canada had filed a " diplomatic note" with the United States in April when the US first announced plans for the moratorium.

Northwest Passage

The legal status of the Northwest Passage is disputed: Canada considers it to be part of its internal waters according to the UNCLOS. The United States and most maritime nations consider them to be an international strait, which means that foreign vessels have right of "transit passage". In such a regime, Canada would have the right to enact fishing and environmental regulation, and fiscal and smuggling laws, as well as laws intended for the safety of shipping, but not the right to close the passage. In addition, the environmental regulations allowed under the UNCLOS are not as robust as those allowed if the Northwest Passage is part of Canada's internal waters.

The legal status of the Northwest Passage is disputed: Canada considers it to be part of its internal waters according to the UNCLOS. The United States and most maritime nations consider them to be an international strait, which means that foreign vessels have right of "transit passage". In such a regime, Canada would have the right to enact fishing and environmental regulation, and fiscal and smuggling laws, as well as laws intended for the safety of shipping, but not the right to close the passage. In addition, the environmental regulations allowed under the UNCLOS are not as robust as those allowed if the Northwest Passage is part of Canada's internal waters.

Northeast Passage

Russia considers portions of theNorthern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (russian: Се́верный морско́й путь, ''Severnyy morskoy put'', shortened to Севморпуть, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route officially defined by Russian legislation as lying east of N ...

, which encompasses only navigational routes through waters within Russia's Arctic EEZ east from Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, ...

to the Bering Strait, to pass through Russian territorial and internal waters in the Kara, Vilkitskiy, and Sannikov Straits.

Arctic territories

Canada

*Arctic Archipelago

The Arctic Archipelago, also known as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, is an archipelago lying to the north of the Canadian continental mainland, excluding Greenland (an autonomous territory of Denmark).

Situated in the northern extremity of No ...

*Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

*Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories (abbreviated ''NT'' or ''NWT''; french: Territoires du Nord-Ouest, formerly ''North-Western Territory'' and ''North-West Territories'' and namely shortened as ''Northwest Territory'') is a federal territory of Canada. ...

*Nunavik

Nunavik (; ; iu, ᓄᓇᕕᒃ) comprises the northern third of the province of Quebec, part of the Nord-du-Québec region and nearly coterminous with Kativik. Covering a land area of north of the 55th parallel, it is the homeland of the ...

*Nunavut

Nunavut ( , ; iu, ᓄᓇᕗᑦ , ; ) is the largest and northernmost territory of Canada. It was separated officially from the Northwest Territories on April 1, 1999, via the '' Nunavut Act'' and the '' Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act'' ...

*Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

Denmark

*Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

Iceland

*Grímsey

Grímsey () is a small Icelandic island, off the north coast of the main island of Iceland, straddling the Arctic Circle. In January 2018 Grímsey had 61 inhabitants.

Before 2009, Grimsey constituted the ''hreppur'' (municipality) of Grí ...

Norway

* Bear Island *Finnmark

Finnmark (; se, Finnmárku ; fkv, Finmarku; fi, Ruija ; russian: Финнмарк) was a county in the northern part of Norway, and it is scheduled to become a county again in 2024.

On 1 January 2020, Finnmark was merged with the neighbour ...

*Jan Mayen

Jan Mayen () is a Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is long (southwest-northeast) and in area, partly covered by glaciers (an area of around the Beerenberg volcano). It has two parts: larger ...

*Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group rang ...

Russia

*Arkhangelsk Oblast

Arkhangelsk Oblast (russian: Арха́нгельская о́бласть, ''Arkhangelskaya oblast'') is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast). It includes the Arctic archipelagos of Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya, as well as the Solo ...

* Big Diomede (due to US Government definition of "Arctic", even though below Arctic Circle)

*Chukotka Autonomous Okrug

Chukotka (russian: Чуко́тка), officially the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug,, ''Čukotkakèn avtonomnykèn okrug'', is the easternmost federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia. It is an autonomous okrug situated in the Russian ...

*Franz Josef Land

, native_name =

, image_name = Map of Franz Josef Land-en.svg

, image_caption = Map of Franz Josef Land

, image_size =

, map_image = Franz Josef Land location-en.svg

, map_caption = Location of Franz Josef ...

*Krasnoyarsk Krai

Krasnoyarsk Krai ( rus, Красноя́рский край, r=Krasnoyarskiy kray, p=krəsnɐˈjarskʲɪj ˈkraj) is a federal subject of Russia (a krai), with its administrative center in the city of Krasnoyarsk, the third-largest city in Si ...

(majority of territory south of the Arctic Circle)

*Murmansk Oblast

Murmansk Oblast (russian: Му́рманская о́бласть, p=ˈmurmənskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ, r=Murmanskaya oblast, ''Murmanskaya oblast''; Kildin Sami: Мурман е̄ммьне, ''Murman jemm'ne'') is a federal subject (an oblast) o ...

*Nenets Autonomous Okrug

The Nenets Autonomous Okrug (russian: Не́нецкий автоно́мный о́круг; Nenets: Ненёцие автономной ӈокрук, ''Nenjocije awtonomnoj ŋokruk'') is a federal subject of Russia and an autonomous okrug of ...

*New Siberian Islands

The New Siberian Islands ( rus, Новосиби́рские Oстрова, r=Novosibirskiye Ostrova; sah, Саҥа Сибиир Aрыылара, translit=Saña Sibiir Arıılara) are an archipelago in the Extreme North of Russia, to the north ...

*Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, ...

*Russian Arctic islands

The Russian Arctic islands are a number of islands groups and sole islands scattered around the Arctic Ocean.

Geography

The islands are all situated within the Arctic Circle and are scattered through the marginal seas of the Arctic Ocean, name ...

*Sakha Republic

Sakha, officially the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia),, is the largest republic of Russia, located in the Russian Far East, along the Arctic Ocean, with a population of roughly 1 million. Sakha comprises half of the area of its governing Far E ...

(most of the Republic south of the Arctic Circle)

*Severnaya Zemlya

Severnaya Zemlya (russian: link=no, Сéверная Земля́ (Northern Land), ) is a archipelago in the Russian high Arctic. It lies off Siberia's Taymyr Peninsula, separated from the mainland by the Vilkitsky Strait. This archipelago ...

(Russia)

*Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

(Russia)

*Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug

The Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (YaNAO; russian: Яма́ло-Не́нецкий автоно́мный о́круг (ЯНАО), ; yrk, Ямалы-Ненёцие автономной ӈокрук, ) or Yamalia (russian: Ямалия) is a fe ...

*Wrangel Island

Wrangel Island ( rus, О́стров Вра́нгеля, r=Ostrov Vrangelya, p=ˈostrəf ˈvrangʲɪlʲə; ckt, Умӄиԓир, translit=Umqiḷir) is an island of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is the 91st largest island in the w ...

United States

*Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

*Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a chain of 14 large v ...

(due to the U.S. Government definition of "Arctic", even though below the Arctic Circle)

* Little Diomede Island (due to the U.S. Government definition of "Arctic", even though below the Arctic Circle)

Others

*Sápmi

(, smj, Sábme / Sámeednam, sma, Saepmie, sju, Sábmie, , , sjd, Са̄мь е̄ммьне, Saam' jiemm'n'e) is the cultural region traditionally inhabited by the Sámi people. Sápmi is in Northern and Eastern Europe and includes the ...

(Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia)

See also

* Arctic policy of Canada * United States Outer Continental Shelf * Outer Continental Shelf (in geography) * List of Russian explorers *Arctic policy of Russia

The Arctic policy of Russia is the domestic and foreign policy of the Russian Federation with respect to the Russian region of the Arctic. The Russian region of the Arctic is defined in the "Russian Arctic Policy" as all Russian possessions loc ...

*Arctic Cooperation and Politics

Arctic cooperation and politics are partially coordinated via the Arctic Council, composed of the eight Arctic nations: the United States, Canada, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, and Denmark with Greenland and the Faroe Islands. The domi ...

* Norwegian continental shelf

*Arctic Council

The Arctic Council is a high-level intergovernmental forum that addresses issues faced by the Arctic governments and the indigenous people of the Arctic. At present, eight countries exercise sovereignty over the lands within the Arctic Circle, ...

* Canada–United States relations#Arctic disputes

*Continental shelf of Russia

The continental shelf of Russia (also called the Russian continental shelf or the Arctic shelf in the Arctic region) is a continental shelf adjacent to the Russian Federation. Geologically, the extent of the shelf is defined as the entirety of the ...

*Territorial claims in Antarctica

Seven sovereign states – Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom – have made eight territorial claims in Antarctica. These countries have tended to place their Antarctic scientific observation and st ...

*Natural resources of the Arctic The natural resources of the Arctic are the mineral and animal natural resources which provide or have potential to provide utility or economic benefit to humans. The Arctic contains significant amounts of minerals, boreal forests, marine life, and ...

*Arctic resources race

The Arctic resources race is the competition between global entities for newly available natural resources of the Arctic. Under the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea, five nations have the legal right to exploit the Arctic's natura ...

References

Further reading

* Albert, Mathias, and Andreas Vasilache. "Governmentality of the Arctic as an international region." ''Cooperation and Conflict'' 53.1 (2018): 3-22online

* Byers, Michael. ''Who owns the Arctic?: Understanding sovereignty disputes in the North'' (Douglas & McIntyre, 2010). * Coates, Ken S., et al. ''Arctic front: defending Canada in the far north'' (Dundurn, 2010). * Dodds, Klaus, and Mark Nuttall. ''The Arctic: What Everyone Needs to Know'' (Oxford University Press, 2019). * Dodds, Klaus. ''The Antarctic: A Very Short Introduction'' (Oxford University Press, 2012). * Griffiths, Franklyn, Rob Huebert, and P. Whitney Lackenbauer. ''Canada and the changing Arctic: Sovereignty, security, and stewardship'' (Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, 2011). * Jensen, Leif Christian, and Geir Hønneland, eds. ''Handbook of the Politics of the Arctic'' (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015). * Keil, Kathrin. "The Arctic: A new region of conflict? The case of oil and gas." ''Cooperation and conflict'' 49.2 (2014): 162–190. * Knecht, Sebastian, and Kathrin Keil. "Arctic geopolitics revisited: spatialising governance in the circumpolar North." ''The Polar Journal'' 3.1 (2013): 178–203. * Ladies, Przemysław. "The United States and Canada towards Russian Arctic Policy: State of Play and Development Prospects." ''Society and Politics'' 2 (63) (2020): 73–103

online

* McCormack, Michael. "More than Words: Securitization and Policymaking in the Canadian Arctic under Stephen Harper," ''American Review of Canadian Studies'' (2020) 50#4 pp 436–460. * Roberts, Kari. "Understanding Russia's security priorities in the Arctic: why Canada-Russia cooperation is still possible." ''Canadian Foreign Policy Journal'' (2020): 1–17. * Tamnes, Rolf, and Kristine Offerdal, eds. ''Geopolitics and Security in the Arctic: Regional dynamics in a global world'' (Routledge, 2014). * Wallace, Ron R. "Canada and Russia in an Evolving Circumpolar Arctic." in ''The Palgrave Handbook of Arctic Policy and Politics'' (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2020) pp. 351–372

online

External links

* * *b

Donald M. McRae

entitled ''Selected Issues Relating to the Arctic'' in th

* van Efferink, Leonhardt

[https://web.archive.org/web/20141218020702/http://www.exploringgeopolitics.org/Publication_Efferink_van_Leonhardt_Arctic_Geopolitics_Russian_Territorial_Claims_UNCLOS_Lomonosov_Ridge_Exclusive_Economic_Zones_Baselines_Flag_Planting_North_Pole_Navy.html Arctic Geopolitics 2 – Russia's territorial claims, UNCLOS, the Lomonosov Ridge]

Frozen Assets

''The historical and legal background of Canada's Arctic claims'' (1952) Manuscript

at Dartmouth College Library

''Territorial sovereignty in the Arctic'' (1947) Manuscript

at Dartmouth College Library {{Energy in Russia * Territorial disputes of Canada Territorial disputes of Denmark Territorial disputes of Norway Territorial disputes of Russia International territorial disputes of the United States Multilateral relations of Russia Canada–Russia relations Canada–United States relations Canada–United States border disputes Russia–United States relations