Teredinidae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater

Removed from its burrow, the fully grown teredo ranges from several centimetres to about a metre in length, depending on the species. The body is cylindrical, slender, naked and superficially

Removed from its burrow, the fully grown teredo ranges from several centimetres to about a metre in length, depending on the species. The body is cylindrical, slender, naked and superficially

Diversity, environmental requirements, and biogeography of bivalve wood-borers (Teredinidae) in European coastal waters.

''Frontiers in Zoology'' 11:13. * Powell A. W. B., ''New Zealand Mollusca'', William Collins Publishers Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand 1979

clam

Clam is a common name for several kinds of bivalve molluscs. The word is often applied only to those that are edible and live as infauna, spending most of their lives halfway buried in the sand of the seafloor or riverbeds. Clams have two shel ...

s with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and commonly eventually destroying) wood that is immersed in sea water, including such structures as wooden piers, docks and ships; they drill passages by means of a pair of very small shells (“valves

A valve is a device or natural object that regulates, directs or controls the flow of a fluid (gases, liquids, fluidized solids, or slurries) by opening, closing, or partially obstructing various passageways. Valves are technically fitting ...

”) borne at one end, with which they rasp their way through. Sometimes called "termites of the sea", they also are known as " Teredo worms" or simply Teredo (from grc, τερηδών, , translit=terēdṓn, lit=wood-worm via ). Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

assigned the common name '' Teredo'' to the best-known genus of shipworms in the 10th edition of his taxonomic ''magnum opus

A masterpiece, ''magnum opus'' (), or ''chef-d’œuvre'' (; ; ) in modern use is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, ...

'', '' Systema Naturæ'' (1758).

Description

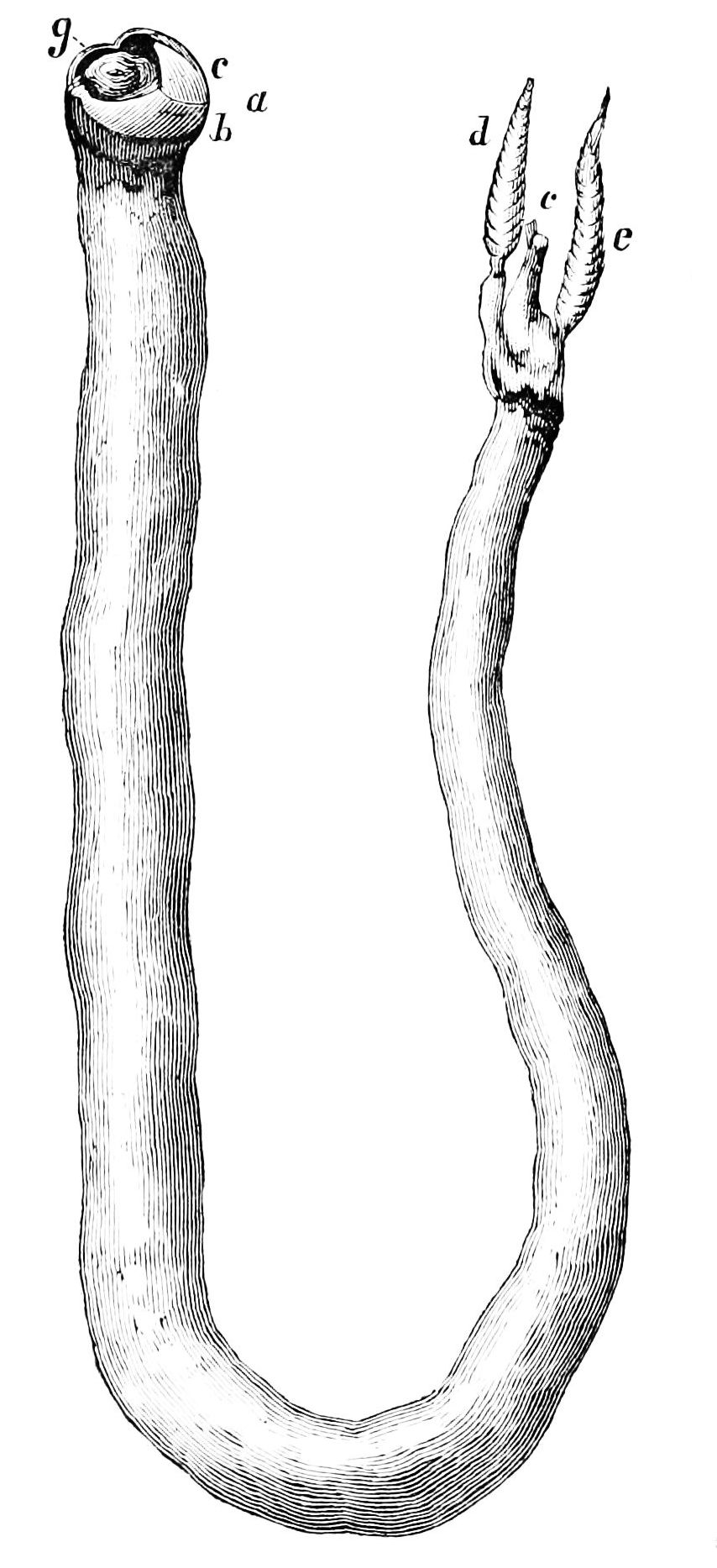

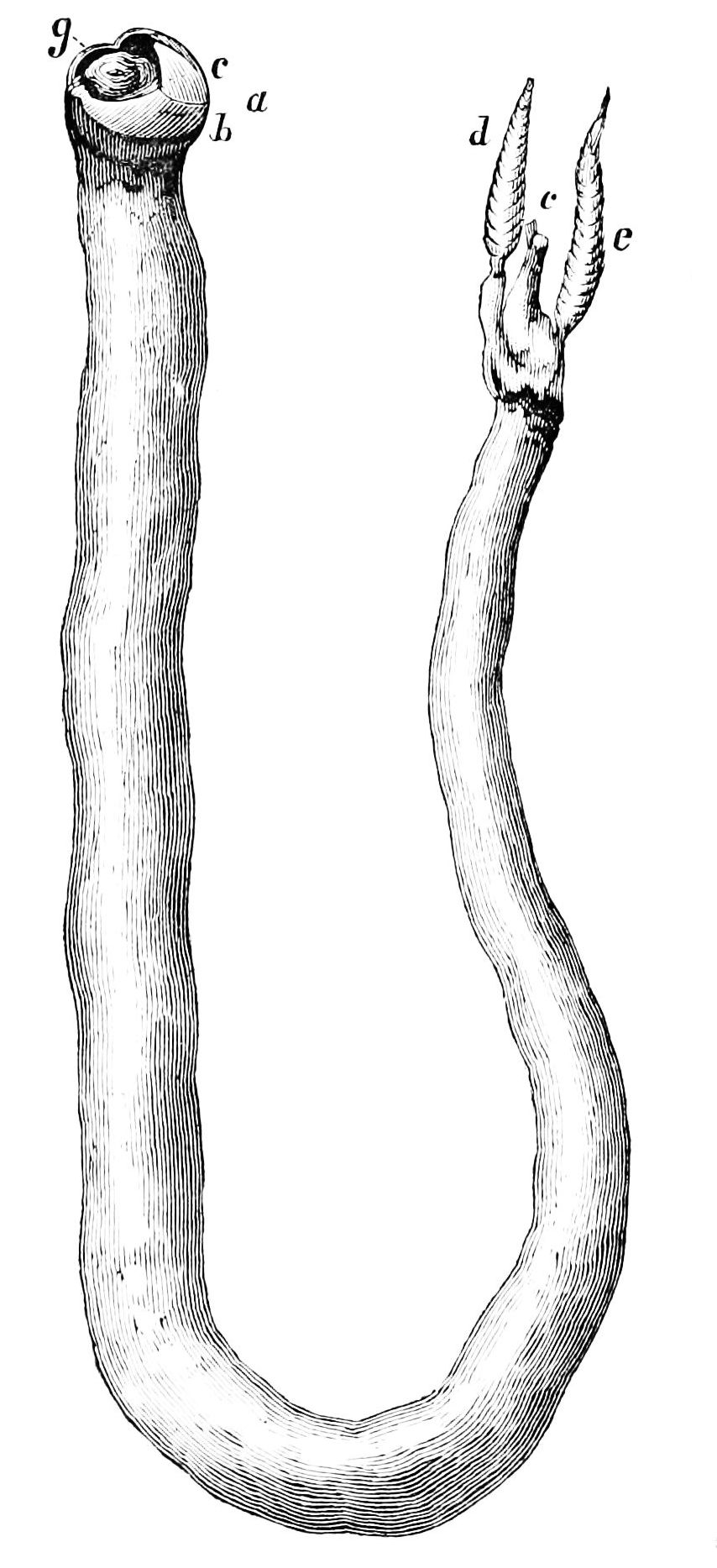

Removed from its burrow, the fully grown teredo ranges from several centimetres to about a metre in length, depending on the species. The body is cylindrical, slender, naked and superficially

Removed from its burrow, the fully grown teredo ranges from several centimetres to about a metre in length, depending on the species. The body is cylindrical, slender, naked and superficially vermiform

Vermiform (ˈvərməˌfôrm) describes something shaped like a worm. The expression is often employed in biology and anatomy to describe usually soft body parts or animals that are more or less tubular or cylindrical. The word root is Latin, ''ve ...

, meaning "worm-shaped". In spite of their slender, worm-like forms, shipworms possess the characteristic morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

of bivalves. The ctinidia lie mainly within the branchial siphon, through which the animal pumps the water that passes over the gills

A gill () is a respiratory organ that many aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow respiration on land provided they are ...

.

The two siphons are very long and protrude from the posterior end of the animal. Where they leave the end of the main part of the body, the siphons pass between a pair of calcareous plates called pallets. If the animal is alarmed, it withdraws the siphons and the pallets protectively block the opening of the tunnel.

The pallets are not to be confused with the two valves of the main shell, which are at the anterior end of the animal. Because they are the organs that the animal applies to boring its tunnel, they generally are located at the tunnel's end. They are borne on the slightly thickened, muscular anterior end of the cylindrical body and they are roughly triangular in shape and markedly concave on their interior surfaces. The outer surfaces are convex and in most species are deeply sculpted into sharp grinding surfaces with which the animals bore their way through the wood or similar medium in which they live and feed. The valves of shipworms are separated and the aperture of the mantle lies between them. The small "foot" (corresponding to the foot of a clam) can protrude through the aperture.

The shipworm lives in waters with oceanic salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal to ...

. Accordingly, it is rare in the brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estu ...

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

, where wooden shipwrecks are preserved for much longer than in the oceans.

The range of various species has changed over time based on human activity. Many waters in developed countries that had been plagued by shipworms were cleared of them by pollution from the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

and the modern era; as environmental regulation led to cleaner waters, shipworms have returned. Climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

has also changed the range of species; some once found only in warmer and more salty waters like the Caribbean have established habitats in the Mediterranean.

''Kuphus polythalamia''

The longest marine bivalve, ''Kuphus polythalamia

''Kuphus polythalamius'' is a species of shipworm, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family Teredinidae.

Description

The tube of ''Kuphus polythalamius'' is known as a crypt and is a calcareous secretion designed to enable the animal to live in it ...

'', was found from a lagoon near Mindanao

Mindanao ( ) ( Jawi: مينداناو) is the second-largest island in the Philippines, after Luzon, and seventh-most populous island in the world. Located in the southern region of the archipelago, the island is part of an island group of ...

island in the southeastern part of the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, which belongs to the same group of mussels and clams. The existence of huge mollusks was established for centuries and studied by the scientists, based on the shells they left behind that were the size of baseball bats

A baseball bat is a smooth wooden or metal club used in the sport of baseball to hit the ball after it is thrown by the pitcher. By regulation it may be no more than in diameter at the thickest part and no more than in length. Although histor ...

(length 1.5 meters (5 ft.), diameter 6 cm (2.3 in.) ). The bivalve is a rare creature that spends its life inside an elephant tusk-like hard shell made of calcium carbonate. It has a protective cap over its head which it reabsorbs to burrow into the mud for food. The case of the shipworm is not just the home of the black slimy worm. Instead, it acts as the primary source of nourishment in a non-traditional way.

''K. polythalamia'' sifts mud and sediment with its gills. Most shipworms are relatively smaller and feed on rotten wood. This shipworm instead relies on a beneficial symbiotic bacteria living in its gills. The bacteria use the hydrogen sulfide for energy to produce organic compounds

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The s ...

that in turn feed the shipworms, similar to the process of photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

used by green plants

Viridiplantae (literally "green plants") are a clade of eukaryotic organisms that comprise approximately 450,000–500,000 species and play important roles in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. They are made up of the green algae, which ...

to convert the carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is trans ...

in the air into simple carbon compounds

Carbon compounds are defined as chemical substances containing carbon. More compounds of carbon exist than any other chemical element except for hydrogen. Organic carbon compounds are far more numerous than inorganic carbon compounds. In general ...

.

Scientists found that ''K. polythalamia'' cooperates with different bacteria than other shipworms, which could be the reason why it evolved from consuming rotten wood to living on hydrogen sulfide in the mud. The internal organs of the shipworm have shrunk from lack of use over the course of its evolution The scientists are planning to study the microbes found in the single gill of ''K. polythalamia'' to find a new possible antimicrobial substance

Biology

When shipworms bore into submerged wood, bacteria ('' Teredinibacter turnerae''), in a special organ called the gland of Deshayes, digest thecellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell w ...

exposed in the fine particles created by the excavation.

The excavated burrow is usually lined with a calcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcareous'' is used as an ad ...

tube. The valves of the shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard o ...

of shipworms are small separate parts located at the anterior end of the worm, used for excavating the burrow.

Taxonomy

Shipworms are marine animals in the phylum Mollusca, orderBivalvia

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, biva ...

, family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Teredinidae. They were included in the now obsolete order ''Eulamellibranchiata'', in which many documents still place them.

Ruth Turner

Ruth Dixon Turner (1914 – April 30, 2000) was a pioneering U.S. marine biologist and malacologist. She was the world's expert on Teredinidae or shipworms, a taxonomic family of wood-boring bivalve mollusks which severely damage wooden ma ...

of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of high ...

was the leading 20th century expert on the Teredinidae; she published a detailed monograph on the family, the 1966 volume "A Survey and Illustrated Catalogue of the Teredinidae" published by the Museum of Comparative Zoology

A museum ( ; plural museums or, rarely, musea) is a building or institution that cares for and displays a collection of artifacts and other objects of artistic, cultural, historical, or scientific importance. Many public museums make thes ...

. More recently, the endosymbionts

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

that are found in the gills have been subject to study the bioconversion of cellulose for fuel energy research.

Genera

Shipworm species comprise several genera, of which '' Teredo'' is the most commonly mentioned. The best known species is ''Teredo navalis

''Teredo navalis'', commonly called the naval shipworm or turu, is a species of saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family ''Teredinidae''. This species is the type species of the genus '' Teredo''. Like other species in this family, ...

''. Historically, ''Teredo'' concentrations in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

have been substantially higher than in most other salt water bodies.

Genera within the family Teridinidae include:

* '' Bactronophorus'' Tapparone-Canefri, 1877

* ''Bankia

Bankia () was a Spanish financial services company that was formed in December 2010, consolidating the operations of seven regional savings banks, and was partially nationalized by the government of Spain in May 2012 due to the near collapse of ...

'' Gray, 1842

* '' Dicyathifer'' Iredale, 1932

* ''Kuphus

''Kuphus'' is a genus of shipworms, marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae. While there are four extinct species in the genus,Maempel, George Zammit. "Kuphus melitensis, a new teredinid bivalve from the late Oligocene Lower Coralline L ...

'' Guettard, 1770

* '' Lithoredo'' Shipway, Distel & Rosenberg, 2019

* '' Lyrodus'' Binney, 1870

* '' Nausitoria'' Wright, 1884

* ''Neoteredo

''Neoteredo'' is a genus of bivalves belonging to the family Teredinidae

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious for boring into (and com ...

'' Bartsch, 1920

* '' Nototeredo'' Bartsch, 1923

* ''Psiloteredo

''Psiloteredo'' is a genus of ship-worms, marine bivalve molluscs of the family Teredinidae

The shipworms are marine bivalve molluscs in the family Teredinidae: a group of saltwater clams with long, soft, naked bodies. They are notorious f ...

'' Bartsch, 1922

* '' Spathoteredo'' Moll, 1928

* '' Teredo'' Linnaeus, 1758

* '' Teredora'' Bartsch, 1921

* '' Teredothyra'' Bartsch, 1921

* '' Uperotus'' Guettard, 1770

* '' Zachsia'' Bulatoff & Rjabtschikoff, 1933

Engineering concerns

Shipworms greatly damage wooden hulls and marinepiling

A deep foundation is a type of foundation that transfers building loads to the earth farther down from the surface than a shallow foundation does to a subsurface layer or a range of depths. A pile or piling is a vertical structural elemen ...

, and have been the subject of much study to find methods to avoid their attacks. Copper sheathing

Copper sheathing is the practice of protecting the under-water hull of a ship or boat from the corrosive effects of salt water and biofouling through the use of copper plates affixed to the outside of the hull. It was pioneered and developed by ...

was used on wooden ships in the latter 18th century and afterwards, as a method of preventing damage by "teredo worms". The first historically documented use of copper sheathing was experiments held by the British Royal Navy with HMS ''Alarm'', which was coppered in 1761 and thoroughly inspected after a two-year cruise. In a letter from the Navy Board to the Admiralty dated 31 August 1763 it was written "that so long as copper plates can be kept upon the bottom, the planks will be thereby entirely secured from the effects of the worm."

In the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

the shipworm caused a crisis in the 18th century by attacking the timber that faced the sea dikes. After that the dikes had to be faced with stones. In 2009, ''Teredo'' have caused several minor collapses along the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between N ...

waterfront in Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,690 i ...

, due to damage to underwater pilings.

Engineering

In the early 19th century,engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limit ...

Marc Brunel

Sir Marc Isambard Brunel (, ; 25 April 1769 – 12 December 1849) was a French-British engineer who is most famous for the work he did in Britain. He constructed the Thames Tunnel and was the father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

Born in Franc ...

observed that the shipworm's valves simultaneously enabled it to tunnel through wood and protected it from being crushed by the swelling timber. With that idea, he designed the first tunnelling shield

A tunnelling shield is a protective structure used during the excavation of large, man-made tunnels. When excavating through ground that is soft, liquid, or otherwise unstable, there is a potential health and safety hazard to workers and the pro ...

, a modular iron tunnelling framework which enabled workers to tunnel through the unstable riverbed beneath the Thames. The Thames Tunnel

The Thames Tunnel is a tunnel beneath the River Thames in London, connecting Rotherhithe and Wapping. It measures 35 feet (11 m) wide by 20 feet (6 m) high and is 1,300 feet (396 m) long, running at a depth of ...

was the first successful large tunnel built under a navigable river.

Literature

Henry David Thoreau's poem "Though All the Fates" pays homage to "New England's worm" which, in the poem, infests the hull of " e vessel, though her masts be firm". In time, no matter what the ship carries or where she sails, the shipworm "her hulk shall bore,/ d sink her in the Indian seas". The hull of the ship wrecked by a whale, inspiring ''Moby Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship ''Pequod'', for revenge against Moby Dick, the giant whi ...

,'' had been weakened by shipworms.

In the Norse Saga of Erik the Red

The ''Saga of Erik the Red'', in non, Eiríks saga rauða (), is an Icelandic saga on the Norse exploration of North America. The original saga is thought to have been written in the 13th century. It is preserved in somewhat different version ...

, Bjarni Herjólfsson, said to be the first European to discover the Americas, had his ship drift into the Irish Sea where it was eaten up by shipworms. He allowed half the crew to escape in a smaller boat covered in seal tar, while he stayed behind to drown with his men.

Cuisine

left, Shipworm as ''tamilok'' InPalawan

Palawan (), officially the Province of Palawan ( cyo, Probinsya i'ang Palawan; tl, Lalawigan ng Palawan), is an archipelagic province of the Philippines that is located in the region of Mimaropa. It is the largest province in the country in t ...

and Aklan

Aklan, officially the Province of Aklan ( Akeanon: ''Probinsya it Akean'' k'ɣan hil, Kapuoran sang Aklan; tl, Lalawigan ng Aklan), is a province in the Western Visayas region of the Philippines. Its capital is Kalibo. The province is situa ...

in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, the shipworm is called and is eaten as a delicacy. It is prepared as kinilaw

''Kinilaw'' ( or , literally "eaten raw") is a raw seafood dish and preparation method native to the Philippines. It is also referred to as Philippine ceviche due to its similarity to the Latin American dish ceviche. It is more accurately a co ...

—that is, raw (cleaned) but marinated

Marinating is the process of soaking foods in a seasoned, often acidic, liquid before cooking. The origin of the word alludes to the use of brine (''aqua marina'' or sea water) in the pickling process, which led to the technique of adding flavor b ...

with vinegar or lime juice

A lime (from French ''lime'', from Arabic ''līma'', from Persian ''līmū'', "lemon") is a citrus fruit, which is typically round, green in color, in diameter, and contains acidic juice vesicles.

There are several species of citrus trees ...

, chopped chili pepper

Chili peppers (also chile, chile pepper, chilli pepper, or chilli), from Nahuatl '' chīlli'' (), are varieties of the berry-fruit of plants from the genus ''Capsicum'', which are members of the nightshade family Solanaceae, cultivated for ...

s and onions, a process very similar to ceviche

Ceviche () is a Peruvian dish typically made from fresh raw fish cured in fresh citrus juices, most commonly lime or lemon. It is also spiced with '' ají'', chili peppers or other seasonings, and julienned red onions, salt, and cilantro are ...

. The taste of the flesh has been compared to a wide variety of foods, from milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfed human infants) before they are able to digest solid food. Immune factors and immune-modula ...

to oysters. Similarly, the delicacy is harvested, sold, and eaten from those taken by local natives in the mangrove forests of West Papua, Indonesia and the central coastal peninsular regions of Thailand near Ko Phra Thong.

See also

*Gribble

A gribble /ˈgɹɪbəl/ (or gribble worm) is any of about 56 species of marine isopod from the family Limnoriidae. They are mostly pale white and small ( long) crustaceans, although '' Limnoria stephenseni'' from subantarctic waters can reach . ...

* Bug shoe

References

Further reading

*Borges, L. M. S., et al. (2014)Diversity, environmental requirements, and biogeography of bivalve wood-borers (Teredinidae) in European coastal waters.

''Frontiers in Zoology'' 11:13. * Powell A. W. B., ''New Zealand Mollusca'', William Collins Publishers Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand 1979

External links

* {{Taxonbar, from=Q14524890 Herbivorous animals Nautical terminology Taxa named by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque