History

Sociological reasoning predates the foundation of the discipline itself. Social analysis has origins in the common stock of universal, global knowledge and philosophy, having been carried out from as far back as the time of Old comic poetry which features social and political criticism, and

Sociological reasoning predates the foundation of the discipline itself. Social analysis has origins in the common stock of universal, global knowledge and philosophy, having been carried out from as far back as the time of Old comic poetry which features social and political criticism, and Etymology

The word ''wikt:sociology, sociology'' (or ) derives part of its name from the Latin word wiktionary:socius, ''socius'' ('companion' or 'fellowship'). The suffix ''wikt:-logy, -logy'' ('the study of') comes from that of the Greek language, Greek wikt:-λογία, -λογία, derived from Logos, λόγος (, 'word' or 'knowledge').Sieyès

The term ''sociology'' was first coined in 1780 by the French essayist Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès in an unpublished manuscript.Comte

''Sociology'' was later defined independently by French philosopher of science Auguste Comte in 1838 as a new way of looking at society. Comte had earlier used the term ''social physics'', but it had been subsequently appropriated by others, most notably the Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet. Comte endeavoured to unify history, psychology, and economics through the scientific understanding of social life. Writing shortly after the malaise of the French Revolution, he proposed that social ills could be remedied through sociological positivism, an Epistemology, epistemological approach outlined in the ''Course of Positive Philosophy, Course in Positive Philosophy'' (1830–1842), later included in ''A General View of Positivism'' (1848). Comte believed a Law of three stages, positivist stage would mark the final era, after conjectural theological and metaphysics, metaphysical phases, in the progression of human understanding. In observing the circular dependence of theory and observation in science, and having classified the sciences, Comte may be regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term.

Marx

Both Comte and Karl Marx set out to develop scientifically justified systems in the wake of European industrialization andTo have given clear and unified answers in familiar empirical terms to those theoretical questions which most occupied men's minds at the time, and to have deduced from them clear practical directives without creating obviously artificial links between the two, was the principal achievement of Marx's theory. The sociological treatment of historical and moral problems, which Comte and after him, Herbert Spencer, Spencer and Hippolyte Taine, Taine, had discussed and mapped, became a precise and concrete study only when the attack of militant Marxism made its conclusions a burning issue, and so made the search for evidence more zealous and the attention to method more intense.

Spencer

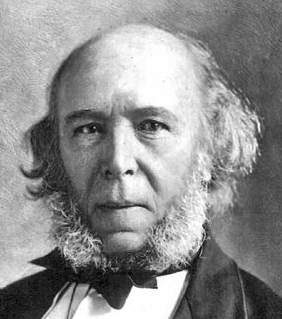

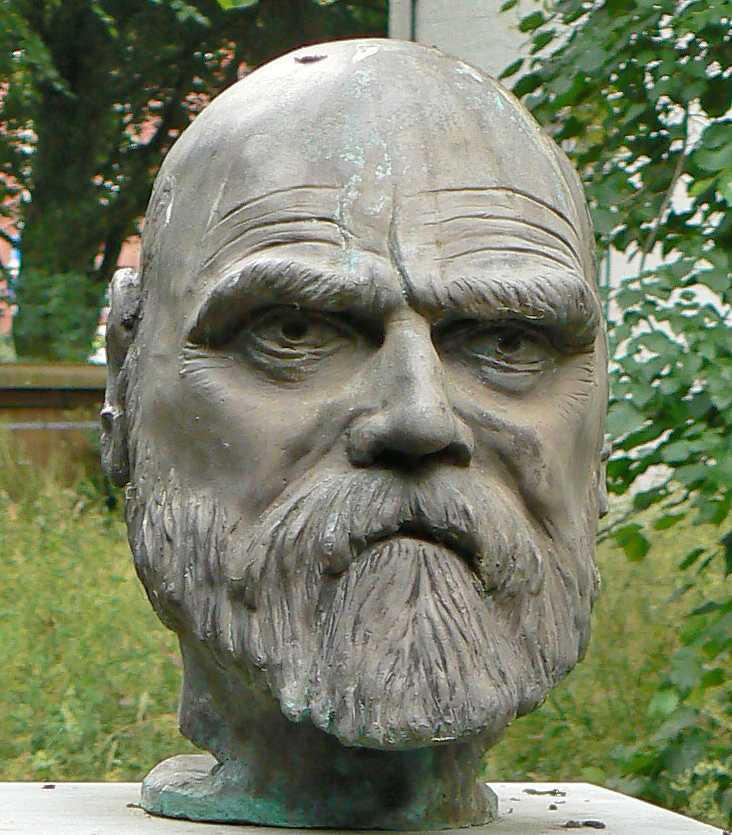

Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) was one of the most popular and influential 19th-century sociologists. It is estimated that he sold one million books in his lifetime, far more than any other sociologist at the time.

So strong was his influence that many other 19th-century thinkers, including Émile Durkheim, defined their ideas in relation to his. Durkheim's ''Division of Labour in Society'' is to a large extent an extended debate with Spencer from whose sociology, many commentators now agree, Durkheim borrowed extensively. Also a notable biologist, Spencer coined the term ''survival of the fittest''. While Marxian ideas defined one strand of sociology, Spencer was a critic of socialism as well as a strong advocate for a laissez-faire style of government. His ideas were closely observed by conservative political circles, especially in the United States and England.

Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) was one of the most popular and influential 19th-century sociologists. It is estimated that he sold one million books in his lifetime, far more than any other sociologist at the time.

So strong was his influence that many other 19th-century thinkers, including Émile Durkheim, defined their ideas in relation to his. Durkheim's ''Division of Labour in Society'' is to a large extent an extended debate with Spencer from whose sociology, many commentators now agree, Durkheim borrowed extensively. Also a notable biologist, Spencer coined the term ''survival of the fittest''. While Marxian ideas defined one strand of sociology, Spencer was a critic of socialism as well as a strong advocate for a laissez-faire style of government. His ideas were closely observed by conservative political circles, especially in the United States and England.

Positivism and antipositivism

Positivism

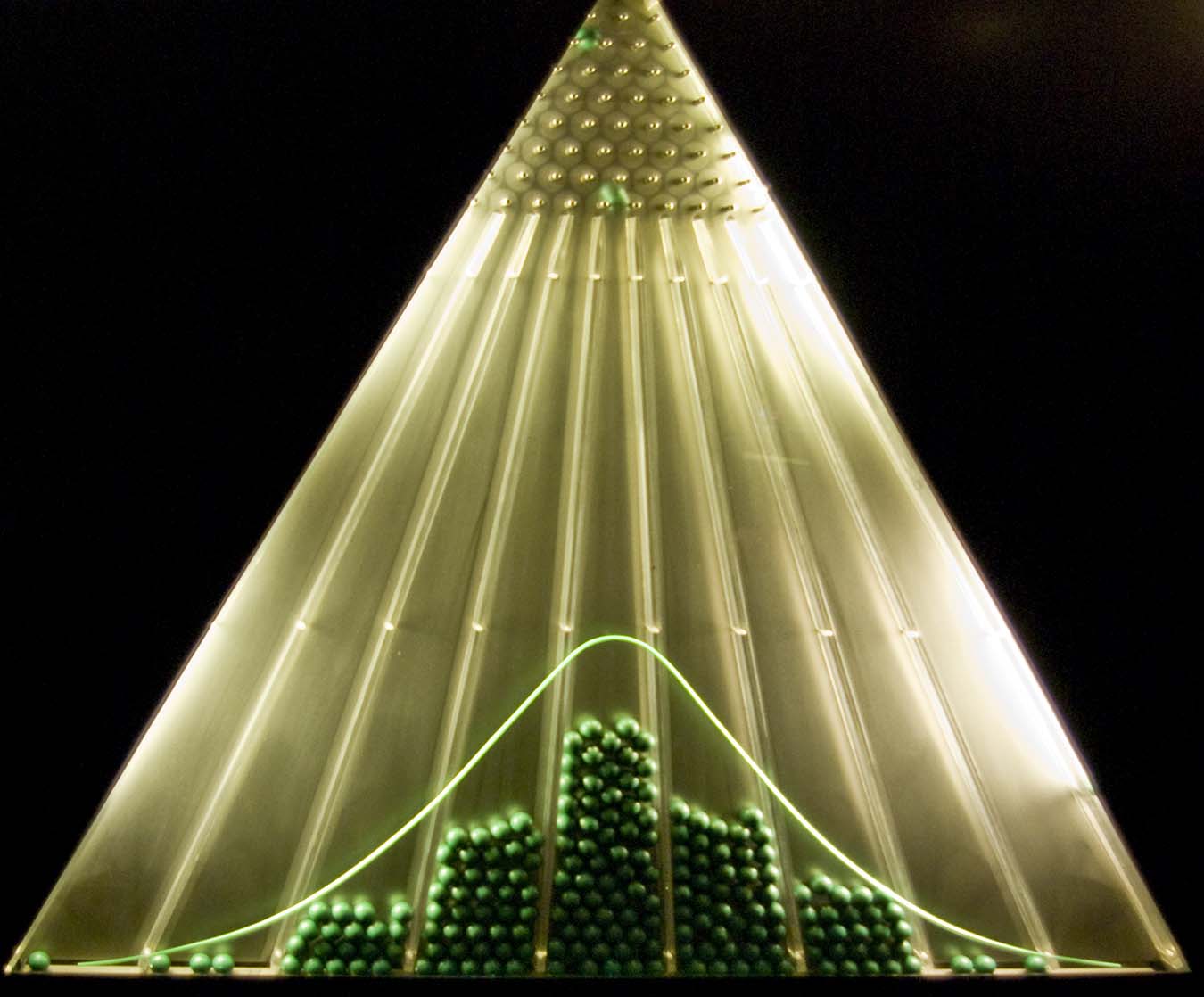

The overarching methodology, methodological principle of positivism is to conduct sociology in broadly the same manner as natural science. An emphasis on empiricism and the scientific method is sought to provide a tested foundation for sociological research based on the assumption that the only authentic knowledge is scientific knowledge, and that such knowledge can only arrive by positive affirmation through scientific methodology. The term has long since ceased to carry this meaning; there are no fewer than twelve distinct epistemologies that are referred to as positivism. Many of these approaches do not self-identify as "positivist", some because they themselves arose in opposition to older forms of positivism, and some because the label has over time become a pejorative term by being mistakenly linked with a theoretical empiricism. The extent of antipositivism, antipositivist criticism has also diverged, with many rejecting the scientific method and others only seeking to amend it to reflect 20th-century developments in the philosophy of science. However, positivism (broadly understood as a scientific approach to the study of society) remains dominant in contemporary sociology, especially in the United States. Loïc Wacquant distinguishes three major strains of positivism: Durkheimian, Logical, and Instrumental. None of these are the same as that set forth by Comte, who was unique in advocating such a rigid (and perhaps optimistic) version. While Émile Durkheim rejected much of the detail of Comte's philosophy, he retained and refined its method. Durkheim maintained that the social sciences are a logical continuation of the natural ones into the realm of human activity, and insisted that they should retain the same objectivity, rationalism, and approach to causality. He developed the notion of objective ''sui generis'' "social facts" to serve as unique empirical objects for the science of sociology to study. The variety of positivism that remains dominant today is termed ''instrumental positivism''. This approach eschews epistemological and metaphysical concerns (such as the nature of social facts) in favour of methodological clarity, replicability, reliabilism, reliability and Validity (logic), validity. This positivism is more or less synonymous with quantitative research, and so only resembles older positivism in practice. Since it carries no explicit philosophical commitment, its practitioners may not belong to any particular school of thought. Modern sociology of this type is often credited to Paul Lazarsfeld, who pioneered large-scale survey studies and developed statistical techniques for analysing them. This approach lends itself to what Robert K. Merton called Middle range theory (sociology), middle-range theory: abstract statements that generalize from segregated hypotheses and empirical regularities rather than starting with an abstract idea of a social whole.Anti-positivism

The German philosopher Hegel criticised traditional empiricist epistemology, which he rejected as uncritical, and determinism, which he viewed as overly mechanistic. Karl Marx's methodology borrowed from Hegelian dialecticism but also a rejection of positivism in favour of critical analysis, seeking to supplement the empirical acquisition of "facts" with the elimination of illusions. He maintained that appearances need to be critiqued rather than simply documented. Early Hermeneutics, hermeneuticians such as Wilhelm Dilthey pioneered the distinction between natural and social science ('Geisteswissenschaft'). Various neo-Kantian philosophers, Phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenologists and Human science, human scientists further theorized how the analysis of the social reality, social world differs to that of the natural environment, natural world due to the irreducibly complex aspects of human society, culture, and being. In the Italian context of development of social sciences and of sociology in particular, there are oppositions to the first foundation of the discipline, sustained by speculative philosophy in accordance with the antiscientific tendencies matured by critique of positivism and evolutionism, so a tradition Progressist struggles to establish itself. At the turn of the 20th century the first generation of German sociologists formally introduced methodological anti-positivism, proposing that research should concentrate on human cultural norm (sociology), norms, value (personal and cultural), values, symbols, and social processes viewed from a resolutely subject (philosophy), subjective perspective. Max Weber argued that sociology may be loosely described as a science as it is able to identify causality, causal relationships of human "social action"—especially among "ideal types", or hypothetical simplifications of complex social phenomena. As a non-positivist, however, Weber sought relationships that are not as "historical, invariant, or generalisable" as those pursued by natural scientists. Fellow German sociologist, Ferdinand Tönnies, theorised on two crucial abstract concepts with his work on "Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft, ''gemeinschaft'' and ''gesellschaft''" (). Tönnies marked a sharp line between the realm of concepts and the reality of social action: the first must be treated axiomatically and in a deductive way ("pure sociology"), whereas the second empirically and inductively ("applied sociology"). Both Weber and Georg Simmel pioneered the "''Verstehen''" (or 'interpretative') method in social science; a systematic process by which an outside observer attempts to relate to a particular cultural group, or indigenous people, on their own terms and from their own point of view. Through the work of Simmel, in particular, sociology acquired a possible character beyond positivist data-collection or grand, deterministic systems of structural law. Relatively isolated from the sociological academy throughout his lifetime, Simmel presented idiosyncratic analyses of modernity more reminiscent of the phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenological and existentialism, existential writers than of Comte or Durkheim, paying particular concern to the forms of, and possibilities for, social individuality. His sociology engaged in a neo-Kantian inquiry into the limits of perception, asking 'What is society?' in a direct allusion to Kant's question 'What is nature?'

Both Weber and Georg Simmel pioneered the "''Verstehen''" (or 'interpretative') method in social science; a systematic process by which an outside observer attempts to relate to a particular cultural group, or indigenous people, on their own terms and from their own point of view. Through the work of Simmel, in particular, sociology acquired a possible character beyond positivist data-collection or grand, deterministic systems of structural law. Relatively isolated from the sociological academy throughout his lifetime, Simmel presented idiosyncratic analyses of modernity more reminiscent of the phenomenology (philosophy), phenomenological and existentialism, existential writers than of Comte or Durkheim, paying particular concern to the forms of, and possibilities for, social individuality. His sociology engaged in a neo-Kantian inquiry into the limits of perception, asking 'What is society?' in a direct allusion to Kant's question 'What is nature?'

Foundations of the academic discipline

The first formal Department of Sociology in the world was established in 1892 by Albion Woodbury Small, Albion Small—from the invitation of William Rainey Harper—at the University of Chicago. The American Journal of Sociology was founded shortly thereafter in 1895 by Small as well.

The institutionalization of sociology as an academic discipline, however, was chiefly led by Émile Durkheim, who developed positivism as a foundation for practical

The first formal Department of Sociology in the world was established in 1892 by Albion Woodbury Small, Albion Small—from the invitation of William Rainey Harper—at the University of Chicago. The American Journal of Sociology was founded shortly thereafter in 1895 by Small as well.

The institutionalization of sociology as an academic discipline, however, was chiefly led by Émile Durkheim, who developed positivism as a foundation for practical Further developments

The first college course entitled "Sociology" was taught in the United States at Yale in 1875 by William Graham Sumner. In 1883 Lester F. Ward, who later became the first president of the American Sociological Association (ASA), published ''Dynamic Sociology—Or Applied social science as based upon statical sociology and the less complex sciences'', attacking the laissez-faire sociology of Herbert Spencer and Sumner. Ward's 1200-page book was used as core material in many early American sociology courses. In 1890, the oldest continuing American course in the modern tradition began at the University of Kansas, lectured by Frank W. Blackmar. The Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago was established in 1892 by Albion Woodbury Small, Albion Small, who also published the first sociology textbook: An introduction to the study of society 1894. George Herbert Mead and Charles Cooley, who had met at the University of Michigan in 1891 (along with John Dewey), moved to Chicago in 1894. Their influence gave rise to social psychology and the symbolic interactionism of the modern Chicago school (sociology), Chicago School. The ''American Journal of Sociology'' was founded in 1895, followed by the ASA in 1905.

The sociological "canon of classics" with Durkheim and Max Weber at the top owes in part to Talcott Parsons, who is largely credited with introducing both to American audiences. Parsons consolidated the sociological tradition and set the agenda for American sociology at the point of its fastest disciplinary growth. Sociology in the United States was less historically influenced by Marxism than its European counterpart, and to this day broadly remains more statistical in its approach.

The first sociology department to be established in the United Kingdom was at the London School of Economics and Political Science (home of the ''British Journal of Sociology'') in 1904. Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse and Edvard Westermarck became the lecturers in the discipline at the University of London in 1907. Harriet Martineau, an English translator of Comte, has been cited as the first female sociologist. In 1909 the ''Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie'' (German Sociological Association) was founded by Ferdinand Tönnies and Max Weber, among others. Weber established the first department in Germany at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1919, having presented an influential new antipositivist sociology. In 1920, Florian Znaniecki set up the first department Sociology in Poland, in Poland. The ''Institute for Social Research'' at the Goethe University Frankfurt, University of Frankfurt (later to become the Frankfurt School of critical theory) was founded in 1923. International co-operation in sociology began in 1893, when René Worms founded the '':fr:René Worms, Institut International de Sociologie'', an institution later eclipsed by the much larger International Sociological Association (ISA), founded in 1949.

The first college course entitled "Sociology" was taught in the United States at Yale in 1875 by William Graham Sumner. In 1883 Lester F. Ward, who later became the first president of the American Sociological Association (ASA), published ''Dynamic Sociology—Or Applied social science as based upon statical sociology and the less complex sciences'', attacking the laissez-faire sociology of Herbert Spencer and Sumner. Ward's 1200-page book was used as core material in many early American sociology courses. In 1890, the oldest continuing American course in the modern tradition began at the University of Kansas, lectured by Frank W. Blackmar. The Department of Sociology at the University of Chicago was established in 1892 by Albion Woodbury Small, Albion Small, who also published the first sociology textbook: An introduction to the study of society 1894. George Herbert Mead and Charles Cooley, who had met at the University of Michigan in 1891 (along with John Dewey), moved to Chicago in 1894. Their influence gave rise to social psychology and the symbolic interactionism of the modern Chicago school (sociology), Chicago School. The ''American Journal of Sociology'' was founded in 1895, followed by the ASA in 1905.

The sociological "canon of classics" with Durkheim and Max Weber at the top owes in part to Talcott Parsons, who is largely credited with introducing both to American audiences. Parsons consolidated the sociological tradition and set the agenda for American sociology at the point of its fastest disciplinary growth. Sociology in the United States was less historically influenced by Marxism than its European counterpart, and to this day broadly remains more statistical in its approach.

The first sociology department to be established in the United Kingdom was at the London School of Economics and Political Science (home of the ''British Journal of Sociology'') in 1904. Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse and Edvard Westermarck became the lecturers in the discipline at the University of London in 1907. Harriet Martineau, an English translator of Comte, has been cited as the first female sociologist. In 1909 the ''Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie'' (German Sociological Association) was founded by Ferdinand Tönnies and Max Weber, among others. Weber established the first department in Germany at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in 1919, having presented an influential new antipositivist sociology. In 1920, Florian Znaniecki set up the first department Sociology in Poland, in Poland. The ''Institute for Social Research'' at the Goethe University Frankfurt, University of Frankfurt (later to become the Frankfurt School of critical theory) was founded in 1923. International co-operation in sociology began in 1893, when René Worms founded the '':fr:René Worms, Institut International de Sociologie'', an institution later eclipsed by the much larger International Sociological Association (ISA), founded in 1949.

Theoretical traditions

Classical theory

The contemporary discipline of sociology is theoretically multi-paradigmatic in line with the contentions of classical social theory. Randall Collins' well-cited survey of sociological theory retroactively labels various theorists as belonging to four theoretical traditions: Functionalism, Conflict, Symbolic Interactionism, and Utilitarianism. Accordingly, modern sociological theory predominantly descends from functionalist (Durkheim) and conflict (Marx and Weber) approaches to social structure, as well as from symbolic-interactionist approaches to social interaction, such as micro-level structural (Georg Simmel, Simmel) and pragmatism, pragmatist (George Herbert Mead, Mead, Charles Cooley, Cooley) perspectives. Utilitarianism (aka rational choice or social exchange), although often associated with economics, is an established tradition within sociological theory. Lastly, as argued by Raewyn Connell, a tradition that is often forgotten is that of Social Darwinism, which applies the logic of Darwinian biological evolution to people and societies. This tradition often aligns with classical functionalism, and was once the dominant theoretical stance in American sociology, from , associated with several founders of sociology, primarily Herbert Spencer, Lester F. Ward, and William Graham Sumner. Contemporary sociological theory retains traces of each of these traditions and they are by no means mutually exclusive.Functionalism

A broad historical paradigm in both sociology and anthropology, functionalism addresses theFunctionalist thought, from Comte onwards, has looked particularly towards biology as the science providing the closest and most compatible model for social science. Biology has been taken to provide a guide to conceptualizing the structure and the function of social systems and to analyzing processes of evolution via mechanisms of adaptation. Functionalism strongly emphasizes the pre-eminence of the social world over its individual parts (i.e. its constituent actors, human subjects).

Conflict theory

Functionalist theories emphasize "cohesive systems" and are often contrasted with "conflict theories", which critique the overarching socio-political system or emphasize the inequality between particular groups. The following quotes from Durkheim and Marx epitomize the political, as well as theoretical, disparities, between functionalist and conflict thought respectively:Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interaction—often associated with interactionism, Phenomenology (sociology), phenomenology, Dramaturgy (sociology), dramaturgy, Antipositivism, interpretivism—is a sociological approach that places emphasis on subjective meanings and the empirical unfolding of social processes, generally accessed through micro-analysis. This tradition emerged in the Chicago school (sociology), Chicago School of the 1920s and 1930s, which, prior to World War II, "had been ''the'' center of sociological research and graduate study." The approach focuses on creating a framework for building a theory that sees society as the product of the everyday interactions of individuals. Society is nothing more than the shared reality that people construct as they interact with one another. This approach sees people interacting in countless settings using symbolic communications to accomplish the tasks at hand. Therefore, society is a complex, ever-changing mosaic of subjective meanings. Some critics of this approach argue that it only looks at what is happening in a particular social situation, and disregards the effects that culture, race or gender (i.e. social-historical structures) may have in that situation. Some important sociologists associated with this approach include Max Weber, George Herbert Mead, Erving Goffman, George Homans, and Peter Blau. It is also in this tradition that the radical-empirical approach of ethnomethodology emerges from the work of Harold Garfinkel.Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is often referred to as exchange theory or rational choice theory in the context of sociology. This tradition tends to privilege the agency of individual rational actors and assumes that within interactions individuals always seek to maximize their own self-interest. As argued by Josh Whitford, rational actors are assumed to have four basic elements: # "a knowledge of alternatives;" # "a knowledge of, or beliefs about the consequences of the various alternatives;" # "an ordering of preferences over outcomes;" and # "a decision rule, to select among the possible alternatives" Exchange theory is specifically attributed to the work of George C. Homans, Peter Blau and Richard Emerson. Organizational sociologists James G. March and Herbert A. Simon noted that an individual's bounded rationality, rationality is bounded by the context or organizational setting. The utilitarian perspective in sociology was, most notably, revitalized in the late 20th century by the work of former American Sociological Association, ASA president James Samuel Coleman, James Coleman.20th-century social theory

Following the decline of theories of sociocultural evolution in the United States, the interactionist thought of the Chicago school (sociology), Chicago School dominated American sociology. As Anselm Strauss describes, "we didn't think symbolic interaction was a perspective in sociology; we thought it was sociology." Moreover, philosophical and psychological pragmatism grounded this tradition. After World War II, mainstream sociology shifted to the survey-research of Paul Lazarsfeld at Columbia University and the general theorizing of Pitirim Sorokin, followed by Talcott Parsons at Harvard University. Ultimately, "the failure of the Chicago, Columbia, and Wisconsin [sociology] departments to produce a significant number of graduate students interested in and committed to general theory in the years 1936–45 was to the advantage of the Harvard department." As Parsons began to dominate general theory, his work primarily referenced European sociology—almost entirely omitting citations of both the American tradition of sociocultural-evolution as well as pragmatism. In addition to Parsons' revision of the sociological canon (which included Marshall, Pareto, Weber and Durkheim), the lack of theoretical challenges from other departments nurtured the rise of the Parsonian structural-functionalist movement, which reached its crescendo in the 1950s, but by the 1960s was in rapid decline. By the 1980s, most functionalist perspectives in Europe had broadly been replaced by conflict theory, conflict-oriented approaches, and to many in the discipline, functionalism was considered "as dead as a dodo:" According to Anthony Giddens, Giddens:The orthodox consensus terminated in the late 1960s and 1970s as the middle ground shared by otherwise competing perspectives gave way and was replaced by a baffling variety of competing perspectives. This third 'generation' of social theory includes phenomenologically inspired approaches, critical theory, ethnomethodology, symbolic interactionism, structuralism, post-structuralism, and theories written in the tradition of hermeneutics and ordinary Philosophy of language, language philosophy.

Pax Wisconsana

While some conflict approaches also gained popularity in the United States, the mainstream of the discipline instead shifted to a variety of empirically oriented Middle range theory (sociology), middle-range theories with no single overarching, or "grand", theoretical orientation. John Levi Martin refers to this "golden age of methodological unity and theoretical calm" as the ''Pax Wisconsana'', as it reflected the composition of the sociology department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison: numerous scholars working on separate projects with little contention. Omar Lizardo describes the ''pax wisconsana'' as "a Midwestern flavored, Robert K. Merton, Mertonian resolution of the theory/method wars in which [sociologists] all agreed on at least two working hypotheses: (1) grand theory is a waste of time; [and] (2) good theory has to be good to think with or goes in the trash bin." Despite the aversion to grand theory in the latter half of the 20th century, several new traditions have emerged that propose various syntheses: structuralism, post-structuralism, cultural sociology and systems theory.Structuralism

The structural linguistics, structuralist movement originated primarily from the work of Durkheim as interpreted by two European scholars: Anthony Giddens, a sociologist, whose theory of structuration draws on the linguistics, linguistic theory of Ferdinand de Saussure; and Claude Lévi-Strauss, an anthropologist. In this context, 'structure' does not refer to 'social structure', but to the semiotic understanding of human culture as a sign (semiotics), system of signs. One may delineate four central tenets of structuralism: # Structure is what determines the structure of a whole. # Structuralists believe that every system has a structure. # Structuralists are interested in 'structural' laws that deal with coexistence rather than changes. # Structures are the 'real things' beneath the surface or the appearance of meaning. The second tradition of structuralist thought, contemporaneous with Giddens, emerges from the American School of social network analysis in the 1970s and 1980s, spearheaded by the Harvard Department of Social Relations led by Harrison White and his students. This tradition of structuralist thought argues that, rather than semiotics, social structure is networks of patterned social relations. And, rather than Levi-Strauss, this school of thought draws on the notions of structure as theorized by Levi-Strauss' contemporary anthropologist, Radcliffe-Brown. Some refer to this as "network structuralism", and equate it to "British structuralism" as opposed to the "French structuralism" of Levi-Strauss.Post-structuralism

Post-structuralist thought has tended to antihumanism, reject 'humanist' assumptions in the construction of social theory. Michel Foucault provides an important critique in his ''the Order of Things, Archaeology of the Human Sciences'', though Jürgen Habermas, Habermas (1986) and Richard Rorty, Rorty (1986) have both argued that Foucault merely replaces one such system of thought with another. The dialogue between these intellectuals highlights a trend in recent years for certain schools of sociology and philosophy to intersect. The anti-humanist position has been associated with "postmodernism", a term used in specific contexts to describe an ''era'' or ''phenomena'', but occasionally construed as a ''method''.Central theoretical problems

Overall, there is a strong consensus regarding the central problems of sociological theory, which are largely inherited from the classical theoretical traditions. This consensus is: how to link, transcend or cope with the following "big three" dichotomies: # subjectivity and objectivity, which deal with ''knowledge''; # structure and agency, which deal with ''action''; # and synchrony and diachrony, which deal with ''time''. Lastly, sociological theory often grapples with the problem of integrating or transcending the divide between micro, meso, and macro-scale social phenomena, which is a subset of all three central problems.Subjectivity and objectivity

The problem of subjectivity and objectivity can be divided into two parts: a concern over the general possibilities of social actions, and the specific problem of social scientific knowledge. In the former, the subjective is often equated (though not necessarily) with the individual, and the individual's intentions and interpretations of the objective. The objective is often considered any public or external action or outcome, on up to society writ large. A primary question for social theorists, then, is how knowledge reproduces along the chain of subjective-objective-subjective, that is to say: how is ''intersubjectivity'' achieved? While, historically, qualitative methods have attempted to tease out subjective interpretations, quantitative survey methods also attempt to capture individual subjectivities. Also, some qualitative methods take a radical approach to objective description in situ. The latter concern with scientific knowledge results from the fact that a sociologist is part of the very object they seek to explain, as Bourdieu explains:Structure and agency

Structure and agency, sometimes referred to as determinism versus voluntarism, form an enduring ontological debate in social theory: "Do social structures determine an individual's behaviour or does human agency?" In this context, agency (sociology), ''agency'' refers to the capacity of individuals to act independently and make free choices, whereas social structure, ''structure'' relates to factors that limit or affect the choices and actions of individuals (e.g. social class, religion, gender, ethnicity, etc.). Discussions over the primacy of either structure or agency relate to the core of sociological epistemology (i.e. "what is the social world made of?", "what is a cause in the social world, and what is an effect?"). A perennial question within this debate is that of "social reproduction": how are structures (specifically, structures producing inequality) reproduced through the choices of individuals?Synchrony and diachrony

Synchrony and diachrony (or statics and dynamics) within social theory are terms that refer to a distinction that emerged through the work of Levi-Strauss who inherited it from the linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure. Synchrony slices moments of time for analysis, thus it is an analysis of static social reality. Diachrony, on the other hand, attempts to analyse dynamic sequences. Following Saussure, synchrony would refer to social phenomena as a static concept like a ''language'', while diachrony would refer to unfolding processes like actual ''speech''. In Anthony Giddens' introduction to ''Central Problems in Social Theory'', he states that, "in order to show the interdependence of action and structure…we must grasp the time space relations inherent in the constitution of all social interaction." And like structure and agency, time is integral to discussion of social reproduction. In terms of sociology, historical sociology is often better positioned to analyse social life as diachronic, while survey research takes a snapshot of social life and is thus better equipped to understand social life as synchronized. Some argue that the synchrony of social structure is a methodological perspective rather than an ontological claim. Nonetheless, the problem for theory is how to integrate the two manners of recording and thinking about social data.Research methodology

Sociological research methods may be divided into two broad, though often supplementary, categories: * Qualitative research, Qualitative designs emphasize understanding of social phenomena through direct observation, communication with participants, or analysis of texts, and may stress contextual and subjective accuracy over generality. * Quantitative method, Quantitative designs approach social phenomena through quantifiable evidence, and often rely on statistical analysis of many cases (or across intentionally designed treatments in an experiment) to establish valid and reliable general claims. Sociologists are often divided into camps of support for particular research techniques. These disputes relate to the epistemological debates at the historical core of social theory. While very different in many aspects, both qualitative and quantitative approaches involve a systematic interaction between social theory, theory and data. Quantitative methodologies hold the dominant position in sociology, especially in the United States. In the discipline's two most cited journals, quantitative articles have historically outnumbered qualitative ones by a factor of two. (Most articles published in the largest British journal, on the other hand, are Qualitative research, qualitative.) Most textbooks on the methodology of social research are written from the quantitative perspective, and the very term "methodology" is often used synonymously with "statistics". Practically all sociology PhD programmes in the United States require training in statistical methods. The work produced by quantitative researchers is also deemed more 'trustworthy' and 'unbiased' by the general public, though this judgment continues to be challenged by antipositivists. The choice of method often depends largely on what the researcher intends to investigate. For example, a researcher concerned with drawing a statistical generalization across an entire population may administer a Survey research, survey questionnaire to a representative sample population. By contrast, a researcher who seeks full contextual understanding of an individual's social actions may choose ethnographic participant observation or open-ended interviews. Studies will commonly combine, or triangulation (social science), 'triangulate', quantitative ''and'' qualitative methods as part of a 'multi-strategy' design. For instance, a quantitative study may be performed to obtain statistical patterns on a target sample, and then combined with a qualitative interview to determine the play of Agency (sociology), agency.Sampling

Quantitative methods are often used to ask questions about a population that is very large, making a census or a complete enumeration of all the members in that population infeasible. A 'sample' then forms a manageable subset of a Statistical population, population. In quantitative research, statistics are used to draw inferences from this sample regarding the population as a whole. The process of selecting a sample is referred to as sampling (statistics), 'sampling'. While it is usually best to random sampling, sample randomly, concern with differences between specific subpopulations sometimes calls for stratified sampling. Conversely, the impossibility of random sampling sometimes necessitates nonprobability sampling, such as convenience sampling or snowball sampling.

Quantitative methods are often used to ask questions about a population that is very large, making a census or a complete enumeration of all the members in that population infeasible. A 'sample' then forms a manageable subset of a Statistical population, population. In quantitative research, statistics are used to draw inferences from this sample regarding the population as a whole. The process of selecting a sample is referred to as sampling (statistics), 'sampling'. While it is usually best to random sampling, sample randomly, concern with differences between specific subpopulations sometimes calls for stratified sampling. Conversely, the impossibility of random sampling sometimes necessitates nonprobability sampling, such as convenience sampling or snowball sampling.

Methods

''The following list of research methods is neither exclusive nor exhaustive:'' * Archival research (or the Historical method): Draws upon the secondary data located in historical archives and records, such as biographies, memoirs, journals, and so on. * Content analysis: The content of interviews and other texts is systematically analysed. Often data is 'coded' as a part of the 'grounded theory' approach using qualitative data analysis (QDA) software, such as Atlas.ti, MAXQDA, NVivo, or QDA Miner. * Experimental research: The researcher isolates a single social process and reproduces it in a laboratory (for example, by creating a situation where unconscious sexist judgements are possible), seeking to determine whether or not certain social Dependent and independent variables, variables can cause, or depend upon, other variables (for instance, seeing if people's feelings about traditional gender roles can be manipulated by the activation of contrasting gender stereotypes). Participants are Random assignment, randomly assigned to different groups that either serve as Scientific control, controls—acting as reference points because they are tested with regard to the dependent variable, albeit without having been exposed to any independent variables of interest—or receive one or more treatments. Randomization allows the researcher to be sure that any resulting differences between groups are the result of the treatment. * Longitudinal study: An extensive examination of a specific person or group over a long period of time. * Observation: Using data from the senses, the researcher records information about social phenomenon or behaviour. Observation techniques may or may not feature participation. In participant observation, the researcher goes into the field (e.g. a community or a place of work), and participates in the activities of the field for a prolonged period of time in order to acquire a deep understanding of it. Data acquired through these techniques may be analysed either quantitatively or qualitatively. In the observation research, a sociologist might study global warming in some part of the world that is less populated. * Program Evaluation is a systematic method for collecting, analyzing, and using information to answer questions about projects, policies and programs, particularly about their effectiveness and efficiency. In both the public and private sectors, stakeholders often want to know whether the programs they are funding, implementing, voting for, or objecting to are producing the intended effect. While program evaluation first focuses on this definition, important considerations often include how much the program costs per participant, how the program could be improved, whether the program is worthwhile, whether there are better alternatives, if there are unintended outcomes, and whether the program goals are appropriate and useful. * Survey research: The researcher gathers data using interviews, questionnaires, or similar feedback from a set of people sampled from a particular population of interest. Survey items from an interview or questionnaire may be open-ended or closed-ended. Data from surveys is usually analysed statistically on a computer.Computational sociology

Sociologists increasingly draw upon computationally intensive methods to analyse and model social phenomena.William Sims Bainbridge, Bainbridge, William Sims 2007.

Sociologists increasingly draw upon computationally intensive methods to analyse and model social phenomena.William Sims Bainbridge, Bainbridge, William Sims 2007.Computational Sociology

" In ''Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology'', edited by George Ritzer, G. Ritzer. Blackwell Reference Online. . . Using computer simulations, artificial intelligence, text mining, complex statistical methods, and new analytic approaches like

Subfields

Culture

Sociologists' approach to culture can be divided into "''sociology of culture''" and "''cultural sociology''"—terms which are similar, though not entirely interchangeable. Sociology of culture is an older term, and considers some topics and objects as more or less "cultural" than others. Conversely, cultural sociology sees all social phenomena as inherently cultural. Sociology of culture often attempts to explain certain cultural phenomena as a product of social processes, while cultural sociology sees culture as a potential explanation of social phenomena.

For Georg Simmel, Simmel, culture referred to "the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history." While early theorists such as Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, Mauss were influential in cultural anthropology, sociologists of culture are generally distinguished by their concern for Modernity, modern (rather than Primitive culture, primitive or ancient) society. Cultural sociology often involves the hermeneutic analysis of words, artefacts and symbols, or ethnographic interviews. However, some sociologists employ historical-comparative or quantitative techniques in the analysis of culture, Weber and Bourdieu for instance. The subfield is sometimes allied with critical theory in the vein of Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and other members of the Frankfurt School. Loosely distinct from the sociology of culture is the field of cultural studies. Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, Birmingham School theorists such as Richard Hoggart and Stuart Hall (cultural theorist), Stuart Hall questioned the division between "producers" and "consumers" evident in earlier theory, emphasizing the reciprocity in the production of texts. Cultural Studies aims to examine its subject matter in terms of cultural practices and their relation to power. For example, a study of a subculture (e.g. white working class youth in London) would consider the social practices of the group as they relate to the dominant class. The "

Sociologists' approach to culture can be divided into "''sociology of culture''" and "''cultural sociology''"—terms which are similar, though not entirely interchangeable. Sociology of culture is an older term, and considers some topics and objects as more or less "cultural" than others. Conversely, cultural sociology sees all social phenomena as inherently cultural. Sociology of culture often attempts to explain certain cultural phenomena as a product of social processes, while cultural sociology sees culture as a potential explanation of social phenomena.

For Georg Simmel, Simmel, culture referred to "the cultivation of individuals through the agency of external forms which have been objectified in the course of history." While early theorists such as Durkheim and Marcel Mauss, Mauss were influential in cultural anthropology, sociologists of culture are generally distinguished by their concern for Modernity, modern (rather than Primitive culture, primitive or ancient) society. Cultural sociology often involves the hermeneutic analysis of words, artefacts and symbols, or ethnographic interviews. However, some sociologists employ historical-comparative or quantitative techniques in the analysis of culture, Weber and Bourdieu for instance. The subfield is sometimes allied with critical theory in the vein of Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and other members of the Frankfurt School. Loosely distinct from the sociology of culture is the field of cultural studies. Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, Birmingham School theorists such as Richard Hoggart and Stuart Hall (cultural theorist), Stuart Hall questioned the division between "producers" and "consumers" evident in earlier theory, emphasizing the reciprocity in the production of texts. Cultural Studies aims to examine its subject matter in terms of cultural practices and their relation to power. For example, a study of a subculture (e.g. white working class youth in London) would consider the social practices of the group as they relate to the dominant class. The "Art, music and literature

Sociology of literature, film, and art is a subset of the sociology of culture. This field studies the social production of artistic objects and its social implications. A notable example is Pierre Bourdieu's ''Les Règles de L'Art: Genèse et Structure du Champ Littéraire'' (1992). None of the founding fathers of sociology produced a detailed study of art, but they did develop ideas that were subsequently applied to literature by others. Marx's theory of ideology was directed at literature by Pierre Macherey, Terry Eagleton and Fredric Jameson. Weber's theory of modernity as cultural rationalization, which he applied to music, was later applied to all the arts, literature included, by Frankfurt School writers such as Theodor W. Adorno, Theodor Adorno and Jürgen Habermas. Durkheim's view of sociology as the study of externally defined social facts was redirected towards literature by Robert Escarpit. Bourdieu's own work is clearly indebted to Marx, Weber and Durkheim.Criminality, deviance, law and punishment

Criminologists analyse the nature, causes, and control of criminal activity, drawing upon methods across sociology, psychology, and the behavioural sciences. The sociology of deviance focuses on actions or behaviours that violate norm (sociology), norms, including both infringements of formally enacted rules (e.g., crime) and informal violations of cultural norms. It is the remit of sociologists to study why these norms exist; how they change over time; and how they are enforced. The concept of social disorganization is when the broader social systems leads to violations of norms. For instance, Robert K. Merton produced a Robert K. Merton#Merton's theory of deviance, typology of deviance, which includes both individual and system level causal explanations of deviance.Sociology of law

The study of law played a significant role in the formation of classical sociology. Durkheim famously described law as the "visible symbol" of social solidarity. The sociology of law refers to both a sub-discipline of sociology and an approach within the field of legal studies. Sociology of law is a diverse field of study that examines the interaction of law with other aspects of society, such as the development of legal institutions and the effect of laws on social change and vice versa. For example, an influential recent work in the field relies on statistical analyses to argue that the increase in incarceration in the US over the last 30 years is due to changes in law and policing and not to an increase in crime; and that this increase has significantly contributed to the persistence of racial Social stratification, stratification.Communications and information technologies

The sociology of communications and information technologies includes "the social aspects of computing, the Internet, new media, computer networks, and other communication and information technologies."Internet and digital media

The Internet is of interest to sociologists in various ways, most practically as a tool for social research, research and as a discussion platform. The sociology of the Internet in the broad sense concerns the analysis of online communities (e.g. newsgroups, social networking sites) and virtual worlds, meaning that there is often overlap with community sociology. Online communities may be studied statistically through social network, network analysis or interpreted qualitatively through virtual ethnography. Moreover, organizational change is catalysed through new media, thereby influencing social change at-large, perhaps forming the framework for a transformation from an industrial society, industrial to an informational society. One notable text is Manuel Castells' ''The Internet Galaxy''—the title of which forms an inter-textual reference to Marshall McLuhan's ''The Gutenberg Galaxy''. Closely related to the sociology of the Internet is digital sociology, which expands the scope of study to address not only the internet but also the impact of the other digital media and devices that have emerged since the first decade of the twenty-first century.Media

As with cultural studies, media study is a distinct discipline that owes to the convergence of sociology and other social sciences and humanities, in particular, literary criticism and critical theory. Though neither the production process nor the critique of aesthetic forms is in the remit of sociologists, analyses of socialization, socializing factors, such as ideology, ideological effects and audience reception, stem from sociological theory and method. Thus the 'sociology of the media' is not a subdiscipline ''per se'', but the media is a common and often indispensable topic.Economic sociology

The term "economic sociology" was first used by William Stanley Jevons in 1879, later to be coined in the works of Durkheim, Weber, and Simmel between 1890 and 1920. Economic sociology arose as a new approach to the analysis of economic phenomena, emphasizing class relations and modernity as a philosophical concept. The relationship between capitalism and modernity is a salient issue, perhaps best demonstrated in Weber's ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'' (1905) and Simmel's ''The Philosophy of Money'' (1900). The contemporary period of economic sociology, also known as ''new economic sociology'', was consolidated by the 1985 work of Mark Granovetter titled "Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness". This work elaborated the concept of embeddedness, which states that economic relations between individuals or firms take place within existing social relations (and are thus structured by these relations as well as the greater social structures of which those relations are a part). Social network analysis has been the primary methodology for studying this phenomenon. Granovetter's theory of the Mark Granovetter#The strength of weak ties, strength of weak ties and Ronald Burt's concept of structural holes are two of the best known theoretical contributions of this field.Work, employment, and industry

The sociology of work, or industrial sociology, examines "the direction and implications of trends in technological change, globalization, labour markets, work organization, managerial practices and division of labour, employment relations to the extent to which these trends are intimately related to changing patterns of inequality in modern societies and to the changing experiences of individuals and families the ways in which workers challenge, resist and make their own contributions to the patterning of work and shaping of work institutions."Education

The sociology of education is the study of how educational institutions determine social structures, experiences, and other outcomes. It is particularly concerned with the schooling systems of modern industrial societies. A classic 1966 study in this field by James Samuel Coleman, James Coleman, known as the "Coleman Report", analysed the performance of over 150,000 students and found that student background and socioeconomic status are much more important in determining educational outcomes than are measured differences in school resources (i.e. per pupil spending). The controversy over "school effects" ignited by that study has continued to this day. The study also found that socially disadvantaged black students profited from schooling in racially mixed classrooms, and thus served as a catalyst for desegregation busing in American public schools.Environment

Environmental sociology is the study of human interactions with the natural environment, typically emphasizing human dimensions of environmental problems, social impacts of those problems, and efforts to resolve them. As with other sub-fields of sociology, scholarship in environmental sociology may be at one or multiple levels of analysis, from global (e.g. world-systems) to local, societal to individual. Attention is paid also to the processes by which environmental problems become ''defined'' and ''known'' to humans. As argued by notable environmental sociologist John Bellamy Foster, the predecessor to modern environmental sociology is Marx's analysis of the metabolic rift, which influenced contemporary thought on sustainability. Environmental sociology is often interdisciplinary and overlaps with the sociology of risk, rural sociology and the sociology of disaster.Human ecology

Human ecology deals with interdisciplinary study of the relationship between humans and their natural, social, and built environments. In addition to Environmental sociology, this field overlaps with architectural sociology, urban sociology, and to some extent visual sociology. In turn, visual sociology—which is concerned with all visual dimensions of social life—overlaps with media studies in that it uses photography, film and other technologies of media.Social pre-wiring

Social pre-wiring deals with the study of fetal social behavior and social interactions in a multi-fetal environment. Specifically, social pre-wiring refers to the ontogeny of social relation, social interaction. Also informally referred to as, "wired to be social". The theory questions whether there is a propensity to social actions, socially oriented action already present ''before'' birth. Research in the theory concludes that newborns are born into the world with a unique genetics, genetic wiring to be social. Circumstantial evidence supporting the social pre-wiring hypothesis can be revealed when examining newborns' behavior. Newborns, not even hours after birth, have been found to display a preparedness for social relation, social interaction. This preparedness is expressed in ways such as their imitation of facial gestures. This observed behavior cannot be attributed to any current form of socialization or social construction. Rather, newborns most likely heredity, inherit to some extentThe central advance of this study is the demonstration that 'social actions' are already performed in the second trimester of Gestational age (obstetrics), gestation. Starting from the 14th week of Gestational age (obstetrics), gestation twin foetuses plan and execute movements specifically aimed at the co-twin. These findings force us to predate the emergence ofsocial behavior Social behavior is behavior among two or more organisms within the same species, and encompasses any behavior in which one member affects the other. This is due to an interaction among those members. Social behavior can be seen as similar to an ...: when the context enables it, as in the case of twin foetuses, other-directed actions are not only possible but predominant over self-directed actions.

Family, gender, and sexuality

Family, gender and sexuality form a broad area of inquiry studied in many sub-fields of sociology. A family is a group of people who are related by kinship ties :- Relations of blood / marriage / civil partnership or adoption. The family unit is one of the most important social institutions found in some form in nearly all known societies. It is the basic unit of social organization and plays a key role in socializing children into the culture of their society. The sociology of the family examines the family, as an institution and unit of socialization, with special concern for the comparatively modern historical emergence of the nuclear family and its distinct gender roles. The notion of "childhood" is also significant. As one of the more basic institutions to which one may apply sociological perspectives, the sociology of the family is a common component on introductory academic curricula. Feminist sociology, on the other hand, is a normative sub-field that observes and critiques the cultural categories of gender and sexuality, particularly with respect to power and inequality. The primary concern of feminist theory is the patriarchy and the systematic oppression of women apparent in many societies, both at the level of small-scale interaction and in terms of the broader social structure. Feminist sociology also analyses how gender interlocks with race and class to produce and perpetuate social inequalities. "How to account for the differences in definitions of femininity and masculinity and in sex role across different societies and historical periods" is also a concern.

Family, gender and sexuality form a broad area of inquiry studied in many sub-fields of sociology. A family is a group of people who are related by kinship ties :- Relations of blood / marriage / civil partnership or adoption. The family unit is one of the most important social institutions found in some form in nearly all known societies. It is the basic unit of social organization and plays a key role in socializing children into the culture of their society. The sociology of the family examines the family, as an institution and unit of socialization, with special concern for the comparatively modern historical emergence of the nuclear family and its distinct gender roles. The notion of "childhood" is also significant. As one of the more basic institutions to which one may apply sociological perspectives, the sociology of the family is a common component on introductory academic curricula. Feminist sociology, on the other hand, is a normative sub-field that observes and critiques the cultural categories of gender and sexuality, particularly with respect to power and inequality. The primary concern of feminist theory is the patriarchy and the systematic oppression of women apparent in many societies, both at the level of small-scale interaction and in terms of the broader social structure. Feminist sociology also analyses how gender interlocks with race and class to produce and perpetuate social inequalities. "How to account for the differences in definitions of femininity and masculinity and in sex role across different societies and historical periods" is also a concern.

Health, illness, and the body

The sociology of health and illness focuses on the social effects of, and public attitudes toward, illnesses, diseases, mental health and disabilities. This sub-field also overlaps with gerontology and the study of the ageing process. Medical sociology, by contrast, focuses on the inner-workings of the medical profession, its organizations, its institutions and how these can shape knowledge and interactions. In Britain, sociology was introduced into the medical curriculum following the ''Goodenough Report'' (1944). The Sociology of the body and embodiment takes a broad perspective on the idea of "the body" and includes "a wide range of embodied dynamics including human and non-human bodies, morphology, human reproduction, anatomy, body fluids, biotechnology, genetics. This often intersects with health and illness, but also theories of bodies as political, social, cultural, economic and ideological productions. The International Sociological Association, ISA maintains a Research Committee devoted to "the Body in the Social Sciences".Death, dying, bereavement

A subfield of the sociology of health and illness that overlaps with cultural sociology is the study of death, dying and bereavement, sometimes referred to broadly as the Thanatology, sociology of death. This topic is exemplified by the work of Douglas Davies and Michael C. Kearl.Knowledge and science

The sociology of knowledge is the study of the relationship between human thought and the social context within which it arises, and of the effects prevailing ideas have on societies. The term first came into widespread use in the 1920s, when a number of German-speaking theorists, most notably Max Scheler, and Karl Mannheim, wrote extensively on it. With the dominance of Structural functionalism, functionalism through the middle years of the 20th century, the sociology of knowledge tended to remain on the periphery of mainstream sociological thought. It was largely reinvented and applied much more closely to everyday life in the 1960s, particularly by Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann in ''The Social Construction of Reality'' (1966) and is still central for methods dealing with qualitative understanding of human society (compare ''socially constructed reality''). The "archaeological" and "genealogical" studies of Michel Foucault are of considerable contemporary influence. The sociology of science involves the study of science as a social activity, especially dealing "with the social conditions and effects of science, and with the social structures and processes of scientific activity." Important theorists in the sociology of science include Robert K. Merton and Bruno Latour. These branches of sociology have contributed to the formation of science and technology studies. Both the American Sociological Association, ASA and the British Sociological Association, BSA have sections devoted to the subfield of Science, Knowledge and Technology. The International Sociological Association, ISA maintains a Research Committee on Science and Technology.Leisure

Sociology of leisure is the study of how humans organize their free time. Leisure includes a broad array of activities, such as Sociology of sport, sport, tourism, and the playing of games. The sociology of leisure is closely tied to the sociology of work, as each explores a different side of the work–leisure relationship. More recent studies in the field move away from the work–leisure relationship and focus on the relation between leisure and culture. This area of sociology began with Thorstein Veblen's ''Theory of the Leisure Class''.Peace, war, and conflict

This subfield of sociology studies, broadly, the dynamics of war, conflict resolution, peace movements, war refugees, conflict resolution and military institutions. As a subset of this subfield, military sociology aims towards the systematic study of the military as a social group rather than as an Military organization, organization. It is a highly specialized sub-field which examines issues related to service personnel as a distinct social group, group with coerced collective action based on shared Advocacy group, interests linked to survival in vocation and combat, with purposes and value (personal and cultural), values that are more defined and narrow than within civil society. Military sociology also concerns civilian-military relations and interactions between other groups or governmental agencies. Topics include the dominant assumptions held by those in the military, changes in military members' willingness to fight, military unionization, military professionalism, the increased utilization of women, the military industrial-academic complex, the military's dependence on research, and the institutional and organizational structure of military.Political sociology

Historically, political sociology concerned the relations between political organization and society. A typical research question in this area might be: "Why do so few American citizens choose to vote?" In this respect questions of political opinion formation brought about some of the pioneering uses of statistical survey research by Paul Lazarsfeld. A major subfield of political sociology developed in relation to such questions, which draws on comparative history to analyse socio-political trends. The field developed from the work of Max Weber and Moisey Ostrogorsky.

Contemporary political sociology includes these areas of research, but it has been opened up to wider questions of power and politics. Today political sociologists are as likely to be concerned with how identities are formed that contribute to structural domination by one group over another; the politics of who knows how and with what authority; and questions of how power is contested in social interactions in such a way as to bring about widespread cultural and social change. Such questions are more likely to be studied qualitatively. The study of social movements and their effects has been especially important in relation to these wider definitions of politics and power.

Political sociology has also moved beyond methodological nationalism and analysed the role of non-governmental organizations, the diffusion of the nation-state throughout the Earth as a social construct, and the role of Statelessness, stateless entities in the modern world society. Contemporary political sociologists also study inter-state interactions and human rights.

Historically, political sociology concerned the relations between political organization and society. A typical research question in this area might be: "Why do so few American citizens choose to vote?" In this respect questions of political opinion formation brought about some of the pioneering uses of statistical survey research by Paul Lazarsfeld. A major subfield of political sociology developed in relation to such questions, which draws on comparative history to analyse socio-political trends. The field developed from the work of Max Weber and Moisey Ostrogorsky.

Contemporary political sociology includes these areas of research, but it has been opened up to wider questions of power and politics. Today political sociologists are as likely to be concerned with how identities are formed that contribute to structural domination by one group over another; the politics of who knows how and with what authority; and questions of how power is contested in social interactions in such a way as to bring about widespread cultural and social change. Such questions are more likely to be studied qualitatively. The study of social movements and their effects has been especially important in relation to these wider definitions of politics and power.

Political sociology has also moved beyond methodological nationalism and analysed the role of non-governmental organizations, the diffusion of the nation-state throughout the Earth as a social construct, and the role of Statelessness, stateless entities in the modern world society. Contemporary political sociologists also study inter-state interactions and human rights.

Population and demography

Demographers or sociologists of population study the size, composition and change over time of a given population. Demographers study how these characteristics impact, or are impacted by, various social, economic or political systems. The study of population is also closely related to human ecology and environmental sociology, which studies a population's relationship with the surrounding environment and often overlaps with urban or rural sociology. Researchers in this field may study the movement of populations: transportation, migrations, diaspora, etc., which falls into the subfield known as Mobilities studies and is closely related to human geography. Demographers may also study spread of disease within a given population or epidemiology.Public sociology

Public sociology refers to an approach to the discipline which seeks to transcend the academy in order to engage with wider audiences. It is perhaps best understood as a style of sociology rather than a particular method, theory, or set of political values. This approach is primarily associated with Michael Burawoy who contrasted it with professional sociology, a form of academic sociology that is concerned primarily with addressing other professional sociologists. Public sociology is also part of the broader field of science communication or science journalism.Race and ethnic relations

The sociology of race and of ethnic relations is the area of the discipline that studies the Social relation, social, political, and economic relations between Race (classification of human beings), races and ethnicities at all levels of society. This area encompasses the study of racism, residential segregation, and other complex social processes between different racial and ethnic groups. This research frequently interacts with other areas of sociology such as Social stratification, stratification and Social psychology (sociology), social psychology, as well as with postcolonial theory. At the level of political policy, ethnic relations are discussed in terms of either assimilationism or multiculturalism. Anti-racism forms another style of policy, particularly popular in the 1960s and 1970s.Religion

The sociology of religion concerns the practices, historical backgrounds, developments, universal themes and roles of religion in society. There is particular emphasis on the recurring role of religion in all societies and throughout recorded history. The sociology of religion is distinguished from the philosophy of religion in that sociologists do not set out to assess the validity of religious truth-claims, instead assuming what Peter L. Berger has described as a position of "methodological atheism". It may be said that the modern formal discipline of sociology ''began'' with the analysis of religion in Durkheim's 1897 suicide (Durkheim book), study of suicide rates among Roman Catholic and Protestant populations. Max Weber published four major texts on religion in a context of economic sociology and social stratification: ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'' (1905), ''The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism'' (1915), ''The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism'' (1915), and ''Ancient Judaism (book), Ancient Judaism'' (1920). Contemporary debates often centre on topics such asSocial change and development

The sociology of change and development attempts to understand how societies develop and how they can be changed. This includes studying many different aspects of society, for example demographic trends, political or technological trends, or changes in culture. Within this field, sociologists often use macrosociology, macrosociological methods or Comparative historical research, historical-comparative methods. In contemporary studies of social change, there are overlaps with international development or community development. However, most of the founders of sociology had theories of social change based on their study of history. For instance, Marx contended that the material circumstances of society ultimately caused the ideal or cultural aspects of society, while Max Weber, Weber argued that it was in fact the cultural mores of Protestantism that ushered in a transformation of material circumstances. In contrast to both, Durkheim argued that societies moved from simple to complex through a process of sociocultural evolution. Sociologists in this field also study processes of globalization and imperialism. Most notably, Immanuel Wallerstein extends Marx's theoretical frame to include large spans of time and the entire globe in what is known as world systems theory. Development sociology is also heavily influenced by post-colonialism. In recent years, Raewyn Connell issued a critique of the bias in sociological research towards countries in the Global North. She argues that this bias blinds sociologists to the lived experiences of the Global South, specifically, so-called, "Northern Theory" lacks an adequate theory of imperialism and colonialism. There are many organizations studying social change, including the Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems, and Civilizations, and the Global Social Change Research Project.Social networks

A social network is a

A social network is a Social psychology

Sociological social psychology focuses on micro-scale social actions. This area may be described as adhering to "sociological miniaturism", examining whole societies through the study of individual thoughts and emotions as well as behaviour of small groups. One special concern to psychological sociologists is how to explain a variety of demographic, social, and cultural facts in terms of human social interaction. Some of the major topics in this field are social inequality, group dynamics, prejudice, aggression, social perception, group behaviour, social change, non-verbal behaviour, socialization, conformity, leadership, and social identity. Social psychology may be taught with Social psychology (psychology), psychological emphasis. In sociology, researchers in this field are the most prominent users of the experimental method (however, unlike their psychological counterparts, they also frequently employ other methodologies). Social psychology looks at social influences, as well as social perception and social interaction.Stratification, poverty and inequality

Social stratification is the hierarchical arrangement of individuals into social classes, castes, and divisions within a society. Modern Western culture, Western societies stratification traditionally relates to cultural and economic classes arranged in three main layers: upper class, middle class, and Working class, lower class, but each class may be further subdivided into smaller classes (e.g. occupational prestige, occupational). Social stratification is interpreted in radically different ways within sociology. Proponents of structural functionalism suggest that, since the stratification of classes and castes is evident in all societies, hierarchy must be beneficial in stabilizing their existence. Conflict theory, Conflict theorists, by contrast, critique the inaccessibility of resources and lack of social mobility in stratified societies. Karl Marx distinguished social classes by their connection to the means of production in the capitalist system: the bourgeoisie own the means, but this effectively includes the proletariat itself as the workers can only sell their own labour power (forming the base and superstructure, material base of the cultural superstructure). Max Weber critiqued Marxist economic determinism, arguing that social stratification is not based purely on economic inequalities, but on other status and power differentials (e.g. patriarchy). According to Weber, stratification may occur among at least three complex variables: # Property (class): A person's economic position in a society, based on birth and individual achievement. Weber differs from Marx in that he does not see this as the supreme factor in stratification. Weber noted how managers of corporations or industries control firms they do not own; Marx would have placed such a person in the proletariat. # Prestige (status): A person's prestige, or popularity in a society. This could be determined by the kind of job this person does or wealth. # Power (political party): A person's ability to get their way despite the resistance of others. For example, individuals in state jobs, such as an employee of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or a member of the United States Congress, may hold little property or status but they still hold immense power. Pierre Bourdieu provides a modern example in the concepts of cultural capital, cultural and symbolic capital. Theorists such as Ralf Dahrendorf have noted the tendency towards an enlarged middle-class in modern Western societies, particularly in relation to the necessity of an educated work force in technological or service-based economies. Perspectives concerning globalization, such as dependency theory, suggest this effect owes to the shift of workers to the Developing country, developing countries.Urban and rural sociology

Urban sociology involves the analysis of social life and human interaction in metropolitan areas. It is a discipline seeking to provide advice for planning and policy making. After the industrial revolution, works such as Georg Simmel's ''The Metropolis and Mental Life'' (1903) focused on urbanization and the effect it had on alienation and anonymity. In the 1920s and 1930s The Chicago school (sociology), Chicago School produced a major body of theory on the nature of the city, important to both urban sociology and criminology, utilizing symbolic interactionism as a method of field research. Contemporary research is commonly placed in a context of globalization, for instance, in Saskia Sassen's study of the "Global city". Rural sociology, by contrast, is the analysis of non-metropolitan areas. As agriculture and wilderness tend to be a more prominent social fact in rural regions, rural sociologists often overlap with environmental sociologists.Community sociology

Often grouped with urban and rural sociology is that of community sociology or the sociology of community. Taking various communities—including online communities—as the unit of analysis, community sociologists study the origin and effects of different associations of people. For instance, German sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies distinguished between two types of human association: ''gemeinschaft'' (usually translated as "community") and ''gesellschaft'' ("society" or "association"). In his 1887 work, ''Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft'', Tönnies argued that ''Gemeinschaft'' is perceived to be a tighter and more cohesive social entity, due to the presence of a "unity of will". The 'development' or 'health' of a community is also a central concern of community sociologists also engage in development sociology, exemplified by the literature surrounding the concept of social capital.Other academic disciplines

Sociology overlaps with a variety of disciplines that study society, in particular social anthropology, political science, economics, social work and social philosophy. Many comparatively new fields such as communication studies, cultural studies, demography and literary theory, draw upon methods that originated in sociology. The terms "Journals