The Liberal Party was one of the two

major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

in the United Kingdom, along with the

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Beginning as an alliance of

Whigs,

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

–supporting

Peelite

The Peelites were a breakaway dissident political faction of the British Conservative Party from 1846 to 1859. Initially led by Robert Peel, the former Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader in 1846, the Peelites supported free trade whilst ...

s and reformist

Radicals

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

in the 1850s, by the end of the 19th century it had formed four governments under

William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

. Despite being divided over the issue of

Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the ...

, the party returned to government in 1905 and won a landslide victory in the

1906 general election

The following elections occurred in the year 1906.

Asia

* 1906 Persian legislative election

Europe

* 1906 Belgian general election

* 1906 Croatian parliamentary election

* Denmark

** 1906 Danish Folketing election

** 1906 Danish Landsting electi ...

.

Under

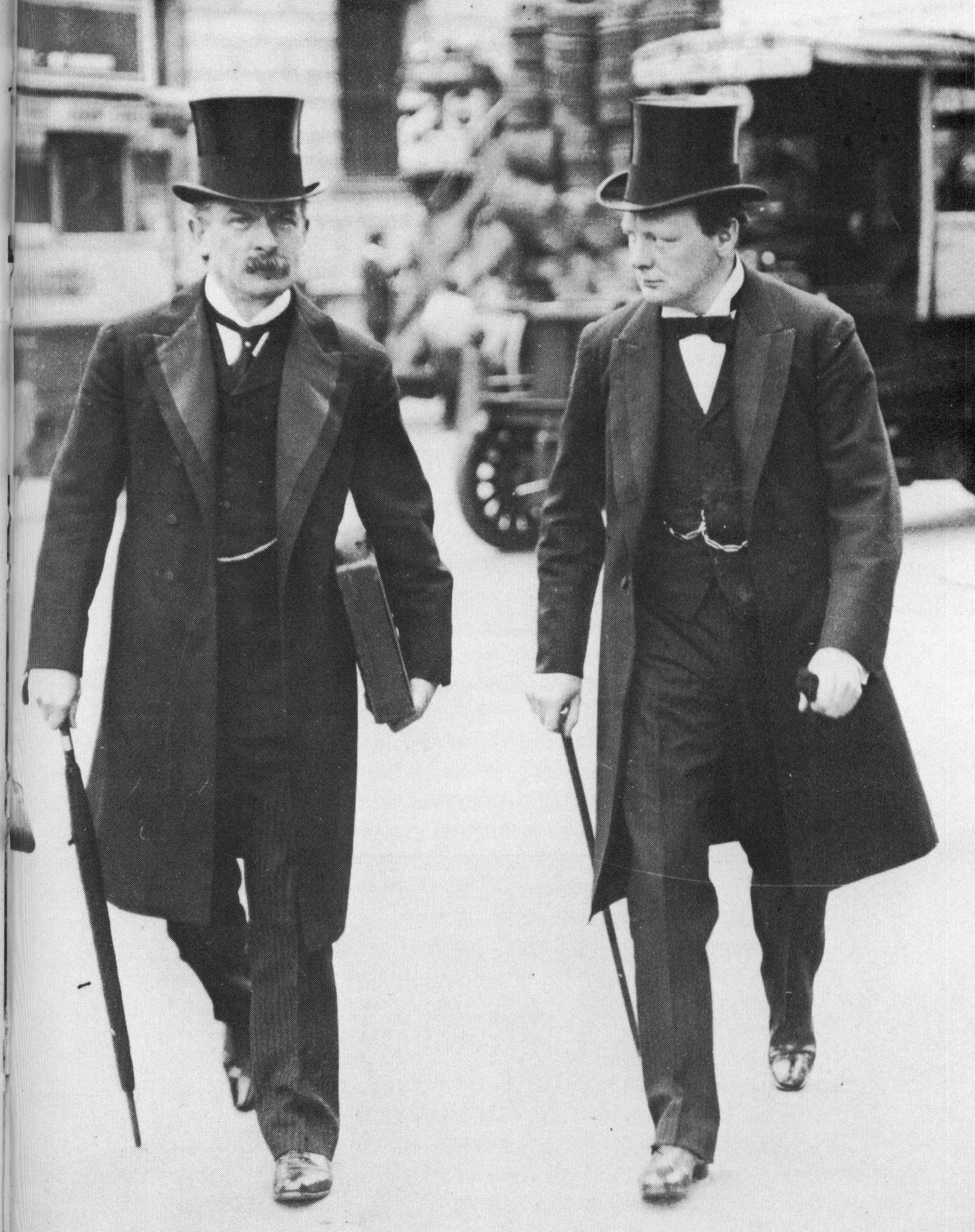

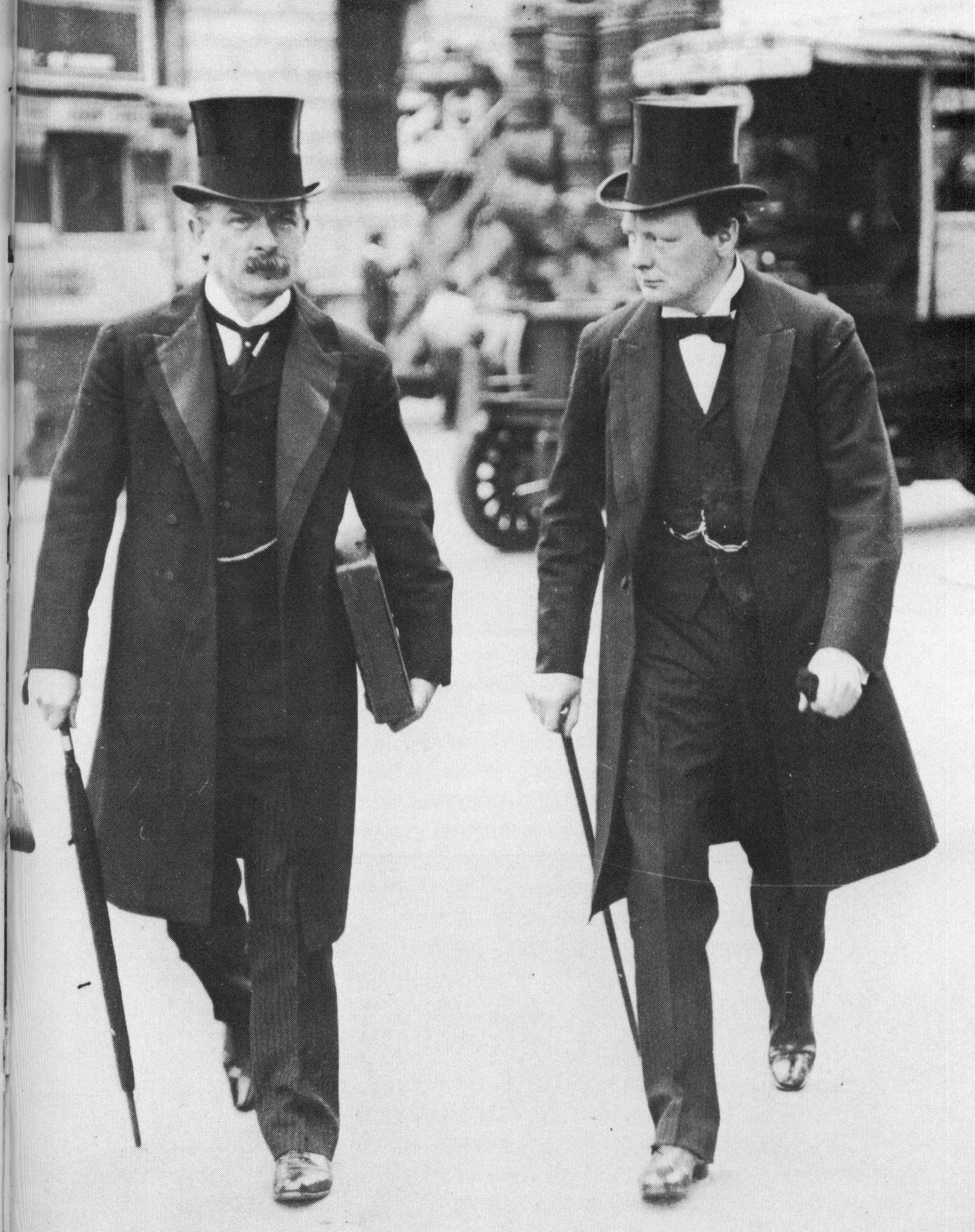

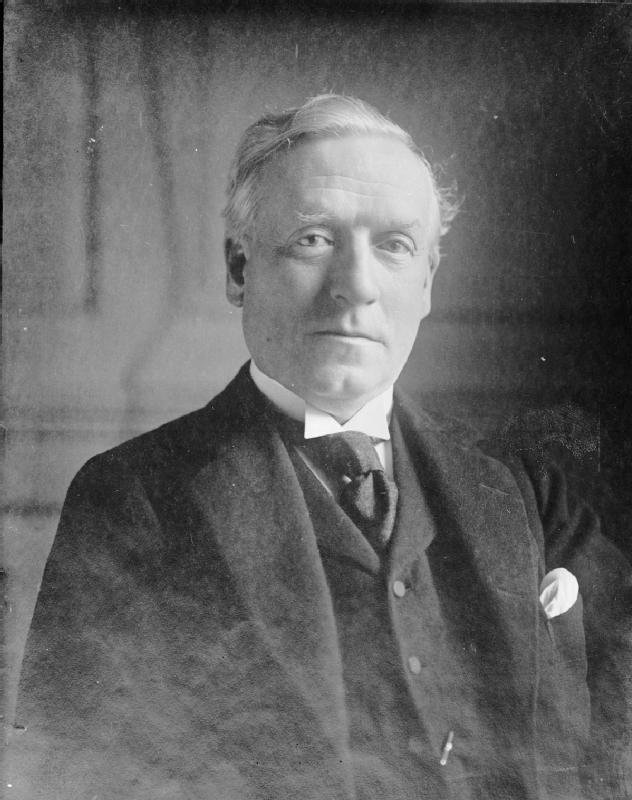

prime ministers Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. He served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 1 ...

(1905–1908) and

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

(1908–1916), the Liberal Party passed

reforms that created a basic

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

. Although Asquith was the

party leader

In a governmental system, a party leader acts as the official representative of their political party, either to a legislature or to the electorate. Depending on the country, the individual colloquially referred to as the "leader" of a political ...

, its dominant figure was

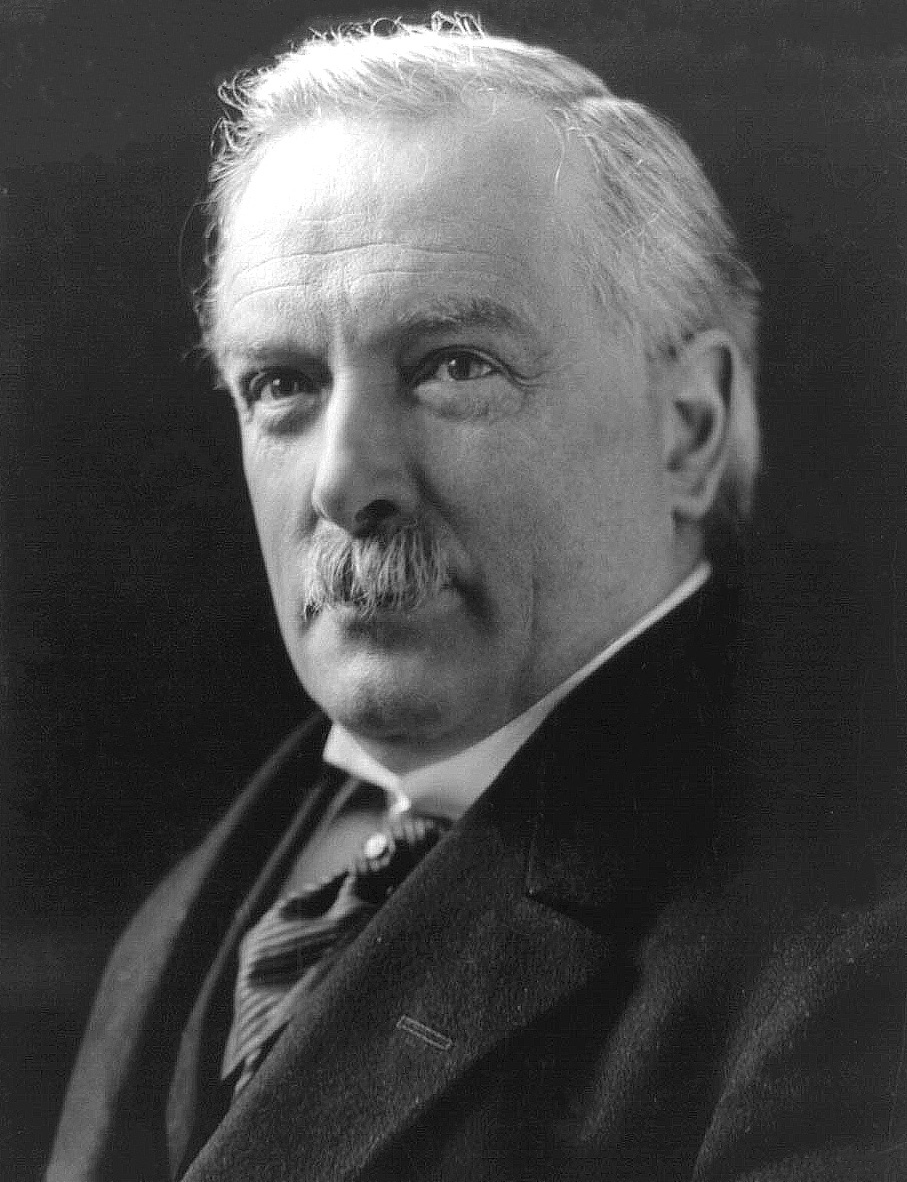

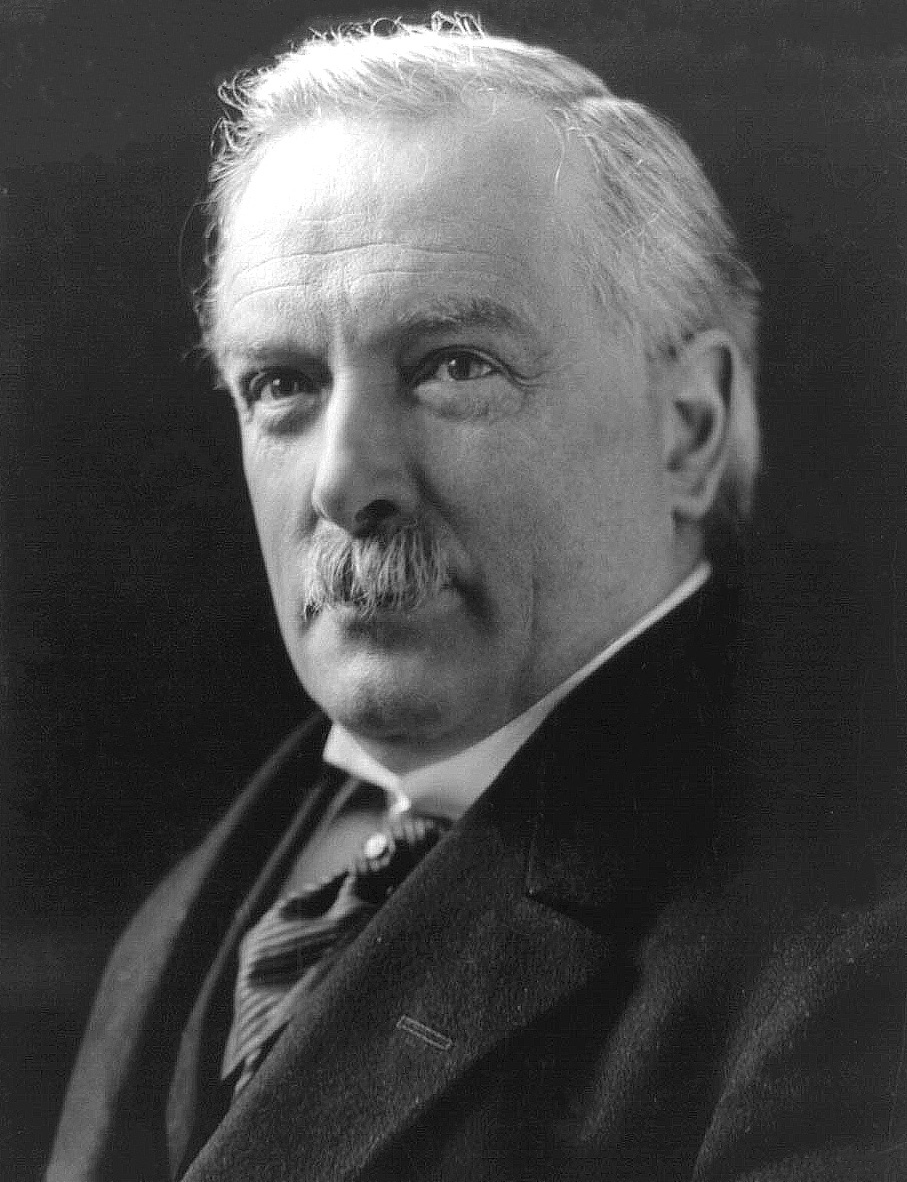

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

. Asquith was overwhelmed by the

wartime role of

coalition

A coalition is a group formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political or economical spaces.

Formation

According to ''A Gui ...

prime minister and Lloyd George replaced him in late 1916, but Asquith remained as Liberal Party leader. The split between

Lloyd George's breakaway faction and Asquith's official Liberal Party badly weakened the party.

The

coalition government of Lloyd George was increasingly dominated by the Conservative Party, which finally deposed him in 1922. By the end of the 1920s, the

Labour Party had replaced the Liberals as the Conservatives' main rival. The Liberal Party went into decline after 1918 and by the 1950s won as few as six seats at general elections. Apart from notable

by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election ( Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to ...

victories, its fortunes did not improve significantly until it formed the

SDP–Liberal Alliance

The SDP–Liberal Alliance was a centrist and social liberal political and electoral alliance in the United Kingdom.

Formed by the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the Liberal Party, the SDP–Liberal Alliance was established in 1981, contestin ...

with the newly formed

Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

(SDP) in 1981. At the

1983 general election, the Alliance won over a quarter of the vote, but only 23 of the 650 seats it contested. At the

1987 general election, its share of the vote fell below 23% and the Liberals and the SDP merged in 1988 to form the Social and Liberal Democrats (SLD), who the following year were renamed the

Liberal Democrats. A splinter group reconstituted the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

in 1989.

Prominent intellectuals associated with the Liberal Party include the philosopher

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

, the economist

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

and social planner

William Beveridge

William Henry Beveridge, 1st Baron Beveridge, (5 March 1879 – 16 March 1963) was a British economist and Liberal politician who was a progressive and social reformer who played a central role in designing the British welfare state. His 1942 ...

.

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

authored ''Liberalism and the Social Problem'' (1909), praised by

Henry William Massingham as "an impressive and convincing argument" and widely considered as the movement’s bible.

History

Origins

The Liberal Party grew out of the

Whigs, who had their origins in an

aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

faction in the reign of

Charles II and the early 19th century

Radicals

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

. The Whigs were in favour of reducing the power of the Crown and increasing the power of

Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

. Although their motives in this were originally to gain more power for themselves, the more idealistic Whigs gradually came to support an expansion of

democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

for its own sake. The great figures of reformist

Whiggery were

Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled '' The Honourable'' from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. He was the arch-ri ...

(died 1806) and his disciple and successor

Earl Grey. After decades in opposition, the Whigs returned to power under Grey in 1830 and carried the

First Reform Act in 1832.

The Reform Act was the climax of Whiggism, but it also brought about the Whigs' demise. The admission of the

middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

es to the franchise and to the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

led eventually to the development of a systematic middle class liberalism and the end of Whiggery, although for many years reforming aristocrats held senior positions in the party. In the years after Grey's retirement, the party was led first by

Lord Melbourne

William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne, (15 March 177924 November 1848), in some sources called Henry William Lamb, was a British Whig politician who served as Home Secretary (1830–1834) and Prime Minister (1834 and 1835–1841). His first pr ...

, a fairly traditional Whig, and then by

Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known by his courtesy title Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and a ...

, the son of a Duke but a crusading radical, and by

Lord Palmerston, a renegade Irish

Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

and essentially a

conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, although capable of radical gestures.

As early as 1839, Russell had adopted the name of "Liberals", but in reality his party was a loose coalition of Whigs in the

House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

and Radicals in the Commons. The leading Radicals were

John Bright

John Bright (16 November 1811 – 27 March 1889) was a British Radical and Liberal statesman, one of the greatest orators of his generation and a promoter of free trade policies.

A Quaker, Bright is most famous for battling the Corn La ...

and

Richard Cobden, who represented the manufacturing towns which had gained representation under the Reform Act. They favoured social reform, personal liberty, reducing the powers of the Crown and the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

(many Liberals were

Nonconformists), avoidance of war and foreign alliances (which were bad for business) and above all

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

. For a century, free trade remained the one cause which could unite all Liberals.

In 1841, the Liberals lost office to the

Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

under

Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

, but their period in

opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* '' The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Com ...

was short because the Conservatives split over the repeal of the

Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They wer ...

, a free trade issue; and a faction known as the

Peelite

The Peelites were a breakaway dissident political faction of the British Conservative Party from 1846 to 1859. Initially led by Robert Peel, the former Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader in 1846, the Peelites supported free trade whilst ...

s (but not Peel himself, who died soon after) defected to the Liberal side. This allowed ministries led by Russell, Palmerston and the Peelite

Lord Aberdeen

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen, (28 January 178414 December 1860), styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British statesman, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite politician and specialist in ...

to hold office for most of the 1850s and 1860s. A leading Peelite was William Gladstone, who was a reforming

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

in most of these governments. The formal foundation of the Liberal Party is traditionally traced to 1859 and the formation of Palmerston's second government.

However, the Whig-Radical amalgam could not become a true modern political party while it was dominated by aristocrats and it was not until the departure of the "Two Terrible Old Men", Russell and Palmerston, that Gladstone could become the first leader of the modern Liberal Party. This was brought about by Palmerston's death in 1865 and Russell's retirement in 1868. After a brief Conservative government (during which the

Second Reform Act

The Representation of the People Act 1867, 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102 (known as the Reform Act 1867 or the Second Reform Act) was a piece of British legislation that enfranchised part of the urban male working class in England and Wales for the first ...

was passed by agreement between the parties), Gladstone won a huge victory at the 1868 election and formed the first Liberal government. The establishment of the party as a national membership organisation came with the foundation of the

National Liberal Federation in 1877. The philosopher

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

was also a Liberal MP from 1865 to 1868.

Gladstone era

For the next thirty years Gladstone and Liberalism were synonymous. William Gladstone served as prime minister four times (1868–74, 1880–85, 1886, and 1892–94). His financial policies, based on the notion of

balanced budget

A balanced budget (particularly that of a government) is a budget in which revenues are equal to expenditures. Thus, neither a budget deficit nor a budget surplus exists (the accounts "balance"). More generally, it is a budget that has no budget ...

s, low taxes and ''

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'', were suited to a developing capitalist society, but they could not respond effectively as economic and social conditions changed. Called the "Grand Old Man" later in life, Gladstone was always a dynamic popular orator who appealed strongly to the

working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

and to the lower middle class. Deeply religious, Gladstone brought a new moral tone to politics, with his evangelical sensibility and his opposition to aristocracy. His moralism often angered his upper-class opponents (including

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

), and his heavy-handed control split the Liberal Party.

In foreign policy, Gladstone was in general against foreign entanglements, but he did not resist the realities of imperialism. For example, he ordered the

occupation of Egypt by British forces in the 1882

Anglo-Egyptian War

The British conquest of Egypt (1882), also known as Anglo-Egyptian War (), occurred in 1882 between Egyptian and Sudanese forces under Ahmed ‘Urabi and the United Kingdom. It ended a nationalist uprising against the Khedive Tewfik Pasha. It ...

. His goal was to create a European order based on co-operation rather than conflict and on mutual trust instead of rivalry and suspicion; the

rule of law

The rule of law is the political philosophy that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. The rule of law is defined in the ''Encyclopedia Britannic ...

was to supplant the reign of force and self-interest. This Gladstonian concept of a harmonious

Concert of Europe was opposed to and ultimately defeated by a

Bismarckian system of manipulated alliances and antagonisms.

As prime minister from 1868 to 1874, Gladstone headed a Liberal Party which was a coalition of Peelites like himself, Whigs and Radicals. He was now a spokesman for "peace, economy and reform". One major achievement was the

Elementary Education Act of 1870, which provided England with an adequate system of elementary schools for the first time. He also secured the abolition of the

purchase of commissions in the British Army

The purchase of officer commissions in the British Army was the practice of paying money to the Army to be made an officer of a cavalry or infantry regiment of the English and later British Army. By payment, a commission as an officer could be sec ...

and of religious tests for admission to

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

; the introduction of the

secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vo ...

in elections; the legalization of

trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

; and the reorganization of the

judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

in the

Judicature Act

Judicature Act is a term which was used in the United Kingdom for legislation which related to the Supreme Court of Judicature.

List United Kingdom

:The Supreme Court of Judicature Act 1873 (36 & 37 Vict. c.66)

:The Supreme Court of Judicature ...

.

Regarding Ireland, the major Liberal achievements were land reform, where he

ended centuries of landlord oppression, and the

disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular s ...

of the (Anglican)

Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the sec ...

through the

Irish Church Act 1869.

In the

1874 general election Gladstone was defeated by the Conservatives under

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation ...

during a sharp economic recession. He formally resigned as Liberal leader and was succeeded by the

Marquess of Hartington

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman ...

, but he soon changed his mind and returned to active politics. He strongly disagreed with Disraeli's pro-

Ottoman foreign policy and in 1880 he conducted the first outdoor mass-election campaign in Britain, known as the

Midlothian campaign. The Liberals won a large majority in the

1880 election. Hartington ceded his place and Gladstone resumed office.

Ireland and Home Rule

Among the consequences of the

Third Reform Act (1884) was the giving of the vote to many

Irish Catholics

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

. In the

1885 general election the

Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nation ...

held the balance of power in the House of Commons, and demanded

Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the ...

as the price of support for a continued Gladstone ministry. Gladstone personally supported Home Rule, but a strong

Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a politic ...

faction led by

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the C ...

, along with the last of the Whigs, Hartington, opposed it. The Irish Home Rule bill proposed to offer all owners of Irish land a chance to sell to the state at a price equal to 20 years' purchase of the rents and allowing tenants to purchase the land.

Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of c ...

reaction was mixed, Unionist opinion was hostile, and the election addresses during the

1886 election revealed English radicals to be against the bill also. Among the Liberal rank and file, several Gladstonian candidates disowned the bill, reflecting fears at the constituency level that the interests of the working people were being sacrificed to finance a costly rescue operation for the landed élite. Further, Home Rule had not been promised in the Liberals' election manifesto, and so the impression was given that Gladstone was buying Irish support in a rather desperate manner to hold on to power.

The result was a catastrophic split in the Liberal Party, and heavy defeat in the

1886 election at the hands of

Lord Salisbury, who was supported by the breakaway

Liberal Unionist Party

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

. There was a final weak Gladstone ministry in 1892, but it also was dependent on Irish support and failed to get Irish Home Rule through the House of Lords.

Newcastle Programme

Historically, the aristocracy was divided between Conservatives and Liberals. However, when Gladstone committed to home rule for Ireland, Britain's upper classes largely abandoned the Liberal party, giving the Conservatives a large permanent majority in the House of Lords. Following the Queen, High Society in London largely ostracized home rulers and Liberal clubs were badly split.

Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the C ...

took a major element of upper-class supporters out of the Party and into a third party called

Liberal Unionism on the Irish issue. It collaborated with and eventually merged into the Conservative party. The Gladstonian liberals in 1891 adopted

The Newcastle Programme that included home rule for Ireland,

disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular s ...

of the

Church of England in Wales,

tighter controls on the sale of liquor, major extension of factory regulation and various democratic political reforms. The Programme had a strong appeal to the nonconformist middle-class Liberal element, which felt liberated by the departure of the aristocracy.

Relations with trade unions

A major long-term consequence of the Third Reform Act was the rise of

Lib-Lab

The Liberal–Labour movement refers to the practice of local Liberal associations accepting and supporting candidates who were financially maintained by trade unions. These candidates stood for the British Parliament with the aim of representing ...

candidates. The Act split all

county constituencies

In the United Kingdom (UK), each of the electoral areas or divisions called constituencies elects one member to the House of Commons.

Within the United Kingdom there are five bodies with members elected by electoral districts called " constitue ...

(which were represented by multiple MPs) into

single-member constituencies

A single-member district is an electoral district represented by a single officeholder. It contrasts with a multi-member district, which is represented by multiple officeholders. Single-member districts are also sometimes called single-winner vot ...

, roughly corresponding to population patterns. With the foundation of the

Labour Party not to come till 1906, many trade unions allied themselves with the Liberals. In areas with working class majorities, in particular

coal-mining

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

areas, Lib-Lab candidates were popular, and they received sponsorship and endorsement from

trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

s. In the first election after the Act was passed (1885), thirteen were elected, up from two in 1874. The Third Reform Act also facilitated the demise of the Whig old guard; in two-member constituencies, it was common to pair a Whig and a radical under the Liberal banner. After the Third Reform Act, fewer former Whigs were selected as candidates.

Reform policies

A broad range of interventionist reforms were introduced by the 1892–1895 Liberal government. Amongst other measures, standards of accommodation and of teaching in schools were improved, factory inspection was made more stringent, and ministers used their powers to increase the wages and reduce the working hours of large numbers of male workers employed by the state.

Historian Walter L. Arnstein concludes:

:Notable as the Gladstonian reforms had been, they had almost all remained within the nineteenth-century Liberal tradition of gradually removing the religious, economic, and political barriers that prevented men of varied creeds and classes from exercising their individual talents in order to improve themselves and their society. As the third quarter of the century drew to a close, the essential bastions of

Victorianism still held firm: respectability; a government of aristocrats and gentlemen now influenced not only by middle-class merchants and manufacturers but also by industrious working people; a prosperity that seemed to rest largely on the tenets of

laissez-faire economics; and a Britannia that ruled the waves and many a dominion beyond.

After Gladstone

Gladstone finally retired in 1894. Gladstone's support for Home Rule deeply divided the party, and it lost its upper and upper-middle-class base, while keeping support among Protestant nonconformists and the Celtic fringe. Historian

R. C. K. Ensor

Sir Robert Charles Kirkwood Ensor (16 October 1877 – 4 December 1958) was a British writer, poet, journalist, liberal intellectual and historian. He is best known for ''England: 1870-1914'' (1936), a volume in the ''Oxford History of England'' ...

reports that after 1886, the main Liberal Party was deserted by practically the entire whig peerage and the great majority of the upper-class and upper-middle-class members. High prestige London clubs that had a Liberal base were deeply split. Ensor notes that, "London society, following the known views of the Queen, practically ostracized home rulers."

The new Liberal leader was the ineffectual

Lord Rosebery. He led the party to a heavy defeat in the

1895 general election.

Liberal factions

The Liberal Party lacked a unified ideological base in 1906. It contained numerous contradictory and hostile factions, such as imperialists and supporters of the Boers; near-socialists and laissez-faire

classical liberals

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, eco ...

;

suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to member ...

s and opponents of

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

;

antiwar elements and supporters of the

military alliance with France.

Nonconformists –

Protestants

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

outside the

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

fold – were a powerful element, dedicated to opposing the

established church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

in terms of education and taxation. However, the non-conformists were losing support amid society at large and played a lesser role in party affairs after 1900. The party, furthermore, also included Irish Catholics, and secularists from the labour movement. Many Conservatives (including

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

) had recently protested against high tariff moves by the Conservatives by switching to the anti-tariff Liberal camp, but it was unclear how many old Conservative traits they brought along, especially on military and naval issues.

The middle-class business, professional and intellectual communities were generally strongholds, although some old aristocratic families played important roles as well. The working-class element was moving rapidly toward the newly emerging Labour Party. One uniting element was widespread agreement on the use of politics and Parliament as a device to upgrade and improve society and to reform politics. All Liberals were outraged when Conservatives used their majority in the House of Lords to block reform legislation. In the House of Lords, the Liberals had lost most of their members, who in the 1890s "became Conservative in all but name." The government could force the unwilling king to create new Liberal peers, and that threat did prove decisive in the battle for dominance of Commons over Lords in 1911.

Rise of New Liberalism

The late nineteenth century saw the emergence of New Liberalism within the Liberal Party, which advocated state intervention as a means of guaranteeing freedom and removing obstacles to it such as poverty and unemployment. The policies of the New Liberalism are now known as

social liberalism

Social liberalism (german: Sozialliberalismus, es, socioliberalismo, nl, Sociaalliberalisme), also known as new liberalism in the United Kingdom, modern liberalism, or simply liberalism in the contemporary United States, left-liberalism ...

.

The New Liberals included intellectuals like

L. T. Hobhouse

Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse, FBA (8 September 1864 – 21 June 1929) was an English liberal political theorist and sociologist, who has been considered one of the leading and earliest proponents of social liberalism. His works, culminating in ...

, and

John A. Hobson

John Atkinson Hobson (6 July 1858 – 1 April 1940) was an English economist and social scientist. Hobson is best known for his writing on imperialism, which influenced Vladimir Lenin, and his theory of underconsumption.

His principal and ea ...

. They saw individual liberty as something achievable only under favourable social and economic circumstances.

In their view, the poverty, squalor, and ignorance in which many people lived made it impossible for freedom and individuality to flourish. New Liberals believed that these conditions could be ameliorated only through collective action coordinated by a strong, welfare-oriented, and interventionist state.

After the historic 1906 victory, the Liberal Party introduced multiple reforms on range of issues, including

health insurance

Health insurance or medical insurance (also known as medical aid in South Africa) is a type of insurance that covers the whole or a part of the risk of a person incurring medical expenses. As with other types of insurance, risk is shared among m ...

,

unemployment insurance

Unemployment benefits, also called unemployment insurance, unemployment payment, unemployment compensation, or simply unemployment, are payments made by authorized bodies to unemployed people. In the United States, benefits are funded by a comp ...

, and

pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

s for elderly workers, thereby laying the groundwork for the future British

welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

. Some proposals failed, such as licensing fewer pubs, or rolling back Conservative educational policies. The

People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was blo ...

of 1909, championed by

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

and fellow Liberal

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, introduced unprecedented taxes on the wealthy in Britain and radical social welfare programmes to the country's policies. In the Liberal camp, as noted by one study, “the Budget was on the whole enthusiastically received.” It was the first budget with the expressed intent of redistributing wealth among the public. It imposed increased taxes on luxuries, liquor, tobacco, high incomes, and land –

taxation that fell heavily on the rich. The new money was to be made available for new welfare programmes as well as new battleships. In 1911 Lloyd George succeeded in putting through Parliament his

National Insurance Act

The National Insurance Act 1911 created National Insurance, originally a system of health insurance for industrial workers in Great Britain based on contributions from employers, the government, and the workers themselves. It was one of the foun ...

, making provision for sickness and invalidism, and this was followed by his

Unemployment Insurance Act.

Historian Peter Weiler argues:

Contrasting Old Liberalism with New Liberalism,

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

noted in a 1908 speech the following:

Liberal zenith

The Liberals languished in opposition for a decade while the coalition of Salisbury and Chamberlain held power. The 1890s were marred by infighting between the three principal successors to Gladstone, party leader

William Harcourt, former prime minister

Lord Rosebery, and Gladstone's personal secretary,

John Morley

John Morley, 1st Viscount Morley of Blackburn, (24 December 1838 – 23 September 1923) was a British Liberal statesman, writer and newspaper editor.

Initially, a journalist in the North of England and then editor of the newly Liberal-leani ...

. This intrigue finally led Harcourt and Morley to resign their positions in 1898 as they continued to be at loggerheads with Rosebery over Irish home rule and issues relating to imperialism. Replacing Harcourt as party leader was Sir

Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. He served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 1 ...

. Harcourt's resignation briefly muted the turmoil in the party, but the beginning of the

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the So ...

soon nearly broke the party apart, with Rosebery and a circle of supporters including important future Liberal figures

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

,

Edward Grey and

Richard Burdon Haldane

Richard Burdon Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, (; 30 July 1856 – 19 August 1928) was a British lawyer and philosopher and an influential Liberal and later Labour politician. He was Secretary of State for War between 1905 and 1912 during ...

forming a clique dubbed the Liberal Imperialists that supported the government in the prosecution of the war. On the other side, more radical members of the party formed a Pro-Boer faction that denounced the conflict and called for an immediate end to hostilities. Quickly rising to prominence among the Pro-Boers was David Lloyd George, a relatively new MP and a master of rhetoric, who took advantage of having a national stage to speak out on a controversial issue to make his name in the party. Harcourt and Morley also sided with this group, though with slightly different aims. Campbell-Bannerman tried to keep these forces together at the head of a moderate Liberal rump, but in 1901 he delivered a speech on the government's "methods of barbarism" in South Africa that pulled him further to the left and nearly tore the party in two. The party was saved after Salisbury's retirement in 1902 when his successor,

Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the ...

, pushed a series of unpopular initiatives such as the

Education Act 1902

The Education Act 1902 ( 2 Edw. 7 c. 42), also known as the Balfour Act, was a highly controversial Act of Parliament that set the pattern of elementary education in England and Wales for four decades. It was brought to Parliament by a Conserva ...

and Joseph Chamberlain called for a new system of protectionist tariffs.

Campbell-Bannerman was able to rally the party around the traditional liberal platform of free trade and land reform and led them to

the greatest election victory in their history. This would prove the last time the Liberals won a majority in their own right.

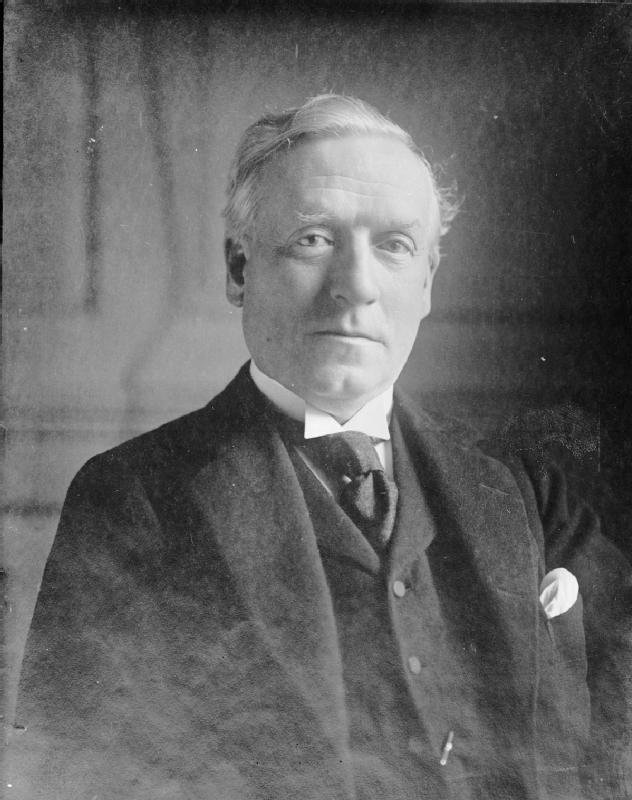

Although he presided over a large majority,

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (né Campbell; 7 September 183622 April 1908) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. He served as the prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1905 to 1908 and leader of the Liberal Party from 1899 to 19 ...

was overshadowed by his ministers, most notably

H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

at the Exchequer,

Edward Grey at the Foreign Office,

Richard Burdon Haldane

Richard Burdon Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, (; 30 July 1856 – 19 August 1928) was a British lawyer and philosopher and an influential Liberal and later Labour politician. He was Secretary of State for War between 1905 and 1912 during ...

at the War Office and

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

at the Board of Trade. Campbell-Bannerman retired in 1908 and died soon after. He was succeeded by Asquith, who stepped up the government's radicalism. Lloyd George succeeded Asquith at the Exchequer, and was in turn succeeded at the Board of Trade by

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, a recent defector from the Conservatives.

The 1906 general election also represented a shift to the left by the Liberal Party. According to Rosemary Rees, almost half of the Liberal MPs elected in 1906 were supportive of the 'New Liberalism' (which advocated government action to improve people's lives),) while claims were made that “five-sixths of the Liberal party are left wing.” Other historians, however, have questioned the extent to which the Liberal Party experienced a leftward shift; according to Robert C. Self however, only between 50 and 60 Liberal MPs out of the 400 in the parliamentary party after 1906 were Social Radicals, with a core of 20 to 30. Nevertheless, important junior offices were held in the cabinet by what Duncan Tanner has termed "genuine New Liberals, Centrist reformers, and

Fabian collectivists," and much legislation was pushed through by the Liberals in government. This included the regulation of working hours,

National Insurance

National Insurance (NI) is a fundamental component of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It acts as a form of social security, since payment of NI contributions establishes entitlement to certain state benefits for workers and their fami ...

and welfare.

A political battle erupted over the

People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was blo ...

, which was rejected by the

House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

and for which the government obtained an electoral mandate at the

January 1910 election. The election resulted in a

hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition (also known as an alliance or bloc) has an absolute majority of legisla ...

, with the government left dependent on the

Irish Nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

. Although the Lords now passed the budget, the government wished to curtail their power to block legislation. Asquith was required by King George V to fight a second general election in

December 1910 (whose result was little changed from that in January) before he agreed, if necessary, to create hundreds of Liberals peers. Faced with that threat, the Lords voted to give up their veto power and allowed the passage of the

Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Pa ...

.

As the price of Irish support, Asquith was now forced to introduce a

third Home Rule bill

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-gover ...

in 1912. Since the House of Lords no longer had the power to block the bill, but only to delay it for two years, it was due to become law in 1914. The Unionist

Ulster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

, led by Sir

Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, PC, Privy Council of Ireland, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Unionism in Ireland, Irish u ...

, launched a campaign of opposition that included the threat of a provisional government and armed resistance in

Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

. The

Ulster Protestants

Ulster Protestants ( ga, Protastúnaigh Ultach) are an ethnoreligious group in the Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about 43.5% of the population. Most Ulster Protestants are descendants of settlers who arrived from Britain in the ...

had the full support of the Conservatives, whose leader,

Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now ...

, was of

Ulster-Scots descent. Government plans to deploy troops into Ulster had to be cancelled after the threat of mass resignation of their commissions by army officers in March 1914 (''see

Curragh Incident

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the U ...

''). Ireland seemed to be on the brink of civil war when the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

broke out in August 1914. Asquith had offered the Six Counties (later to become

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

) an opt out from Home Rule for six years (i.e. until after two more general elections were likely to have taken place) but the Nationalists refused to agree to permanent

Partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. ...

. Historian

George Dangerfield

George Bubb Dangerfield (28 October 1904 in Newbury, Berkshire – 27 December 1986 in Santa Barbara, California) was a British-born American journalist, historian, and the literary editor of '' Vanity Fair'' from 1933 to 1935. He is known prima ...

has argued that the multiplicity of crises in 1910 to 1914, political and industrial, so weakened the Liberal coalition before the war broke out that it marked the ''

Strange Death of Liberal England

''The Strange Death of Liberal England'' is a book written by George Dangerfield and published in 1935. Its thesis is that the Liberal Party in the United Kingdom ruined itself in dealing with the House of Lords, women's suffrage, the Irish que ...

''. However, most historians date the collapse to the crisis of the First World War.

Decline

The Liberal Party might have survived a short war, but the totality of the Great War called for measures that the Party had long rejected. The result was the permanent destruction of the ability of the Liberal Party to lead a government. Historian

Robert Blake explains the dilemma:

Blake further notes that it was the Liberals, not the Conservatives who needed the moral outrage of Belgium to justify going to war, while the Conservatives called for intervention from the start of the crisis on the grounds of ''realpolitik'' and the balance of power. However, Lloyd George and Churchill were zealous supporters of the war, and gradually forced the old peace-orientated Liberals out.

Asquith was blamed for the poor British performance in the first year. Since the Liberals ran the war without consulting the Conservatives, there were heavy partisan attacks. However, even Liberal commentators were dismayed by the lack of energy at the top. At the time, public opinion was intensely hostile, both in the media and in the street, against any young man in civilian garb and labeled as a slacker. The leading Liberal newspaper, the ''

Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the G ...

'' complained:

Asquith's Liberal government was brought down in , due in particular to a

crisis in inadequate artillery shell production and the protest resignation of

Admiral Fisher over the disastrous

Gallipoli Campaign against Turkey. Reluctant to face doom in an election, Asquith formed a new coalition government on 25 May, with the majority of the new cabinet coming from his own Liberal party and the

Unionist (Conservative) party, along with a token Labour representation. The new government lasted a year and a half, and was the last time Liberals controlled the government. The analysis of historian

A. J. P. Taylor is that the British people were so deeply divided over numerous issues, But on all sides there was growing distrust of the Asquith government. There was no agreement whatsoever on wartime issues. The leaders of the two parties realized that embittered debates in Parliament would further undermine popular morale and so the House of Commons did not once discuss the war before May 1915. Taylor argues:

The 1915 coalition fell apart at the end of 1916, when the Conservatives withdrew their support from Asquith and gave it instead to Lloyd George, who became prime minister at the head of a new coalition largely made up of Conservatives. Asquith and his followers moved to the opposition benches in Parliament and the Liberal Party was deeply split once again.

Lloyd George as a Liberal heading a Conservative coalition

Lloyd George remained a Liberal all his life, but he abandoned many standard Liberal principles in his crusade to win the war at all costs. He insisted on strong government controls over business as opposed to the ''

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups ...

'' attitudes of traditional Liberals. in 1915-16 he had insisted on conscription of young men into the Army, a position that deeply troubled his old colleagues. That brought him and a few like-minded Liberals into the new coalition on the ground long occupied by Conservatives. There was no more planning for world peace or liberal treatment of Germany, nor discomfit with aggressive and authoritarian measures of state power. More deadly to the future of the party, says historian Trevor Wilson, was its repudiation by ideological Liberals, who decided sadly that it no longer represented their principles. Finally the presence of the vigorous new Labour Party on the left gave a new home to voters disenchanted with the Liberal performance.

The last majority Liberal Government in Britain was elected in 1906. The years preceding the First World War were marked by worker strikes and civil unrest and saw many violent confrontations between civilians and the police and armed forces. Other issues of the period included

women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

and the

Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the ...

movement. After the carnage of 1914–1918, the democratic reforms of the

Representation of the People Act 1918

The Representation of the People Act 1918 was an Act of Parliament passed to reform the electoral system in Great Britain and Ireland. It is sometimes known as the Fourth Reform Act. The Act extended the franchise in parliamentary elections, al ...

instantly tripled the number of people entitled to vote in Britain from seven to twenty-one million. The Labour Party benefited most from this huge change in the electorate, forming its

first minority government in 1924.

In the

1918 general election, Lloyd George, hailed as "the Man Who Won the War", led his coalition into a

khaki election

In Westminster systems of government, a khaki election is any national election which is heavily influenced by wartime or postwar sentiment. In the British general election of 1900, the Conservative Party government of Lord Salisbury was retu ...

. Lloyd George and the Conservative leader

Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now ...

wrote a joint letter of support to candidates to indicate they were considered the official Coalition candidates—this "

coupon", as it became known, was issued against many sitting Liberal MPs, often to devastating effect, though not against Asquith himself. The coalition won a massive victory: Labour increased their position slightly but the Asquithian Liberals were decimated. Those remaining Liberal MPs who were opposed to the Coalition Government went into opposition under the parliamentary leadership of

Sir Donald MacLean who also became

Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

. Asquith, who had appointed MacLean, remained as overall Leader of the Liberal Party even though he lost his seat in 1918. Asquith

returned to Parliament in 1920 and resumed leadership. Between 1919 and 1923, the anti-Lloyd George Liberals were called Asquithian Liberals,

Wee Free Liberals or

Independent Liberals.

Lloyd George was increasingly under the influence of the rejuvenated Conservative party who numerically dominated the coalition. In 1922, the Conservative backbenchers

rebelled against the continuation of the coalition, citing, in particular, Lloyd George's plan for war with Turkey in the

Chanak Crisis, and his corrupt sale of honours. He resigned as prime minister and was succeeded by

Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now ...

.

At the

1922

Events

January

* January 7 – Dáil Éireann (Irish Republic), Dáil Éireann, the parliament of the Irish Republic, ratifies the Anglo-Irish Treaty by 64–57 votes.

* January 10 – Arthur Griffith is elected President of Dáil Éirean ...

and

1923 elections the Liberals won barely a third of the vote and only a quarter of the seats in the House of Commons as many radical voters abandoned the divided Liberals and went over to Labour. In 1922, Labour became the official opposition. A reunion of the two warring factions took place in 1923 when the new Conservative prime minister

Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

committed his party to protective tariffs, causing the Liberals to reunite in support of free trade. The party gained ground in the

1923 general election but made most of its gains from Conservatives whilst losing ground to Labour—a sign of the party's direction for many years to come. The party remained the third largest in the House of Commons, but the Conservatives had lost their majority. There was much speculation and fear about the prospect of a Labour government and comparatively little about a Liberal government, even though it could have plausibly presented an experienced team of ministers compared to Labour's almost complete lack of experience as well as offering a middle ground that could obtain support from both Conservatives and Labour in crucial Commons divisions. However, instead of trying to force the opportunity to form a Liberal government, Asquith decided instead to allow Labour the chance of office in the belief that they would prove incompetent and this would set the stage for a revival of Liberal fortunes at Labour's expense, but it was a fatal error.

Labour was determined to destroy the Liberals and become the sole party of the left.

Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

was forced into a

snap election in 1924 and although his government was defeated he achieved his objective of virtually wiping the Liberals out as many more radical voters now moved to Labour whilst moderate middle-class Liberal voters concerned about socialism moved to the Conservatives. The Liberals were reduced to a mere forty seats in Parliament, only seven of which had been won against candidates from both parties and none of these formed a coherent area of Liberal survival. The party seemed finished, and during this period some Liberals, such as Churchill, went over to the Conservatives while others went over to Labour. Several Labour ministers of later generations, such as

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

and

Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British politician, writer and diarist who served as a Cabinet minister in the 1960s and 1970s. A member of the Labour Party, ...

, were the sons of Liberal MPs.

Asquith finally resigned as Liberal leader in 1926 (he died in 1928). Lloyd George, now party leader, began a drive to produce coherent policies on many key issues of the day. In the

1929 general election, he made a final bid to return the Liberals to the political mainstream, with an ambitious programme of state stimulation of the economy called ''We Can Conquer Unemployment!'', largely written for him by the Liberal economist

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

. The Liberal Party stood in Northern Ireland for the first and only time in the

1929 general election, gaining 17% of the vote, but won no seats. The Liberals gained ground, but once again it was at the Conservatives' expense whilst also losing seats to Labour. Indeed, the urban areas of the country suffering heavily from

unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refe ...

, which might have been expected to respond the most to the radical economic policies of the Liberals, instead gave the party its worst results. By contrast, most of the party's seats were won either due to the absence of a candidate from one of the other parties or in rural areas on the

Celtic fringe

The Celtic nations are a cultural area and collection of geographical regions in Northwestern Europe where the Celtic languages and cultural traits have survived. The term ''nation'' is used in its original sense to mean a people who sha ...

, where local evidence suggests that economic ideas were at best peripheral to the electorate's concerns. The Liberals now found themselves with 59 members, holding the balance of power in a Parliament where Labour was the largest party but lacked an overall majority. Lloyd George offered a degree of support to the Labour government in the hope of winning concessions, including a degree of electoral reform to introduce the

alternative vote, but this support was to prove bitterly divisive as the Liberals increasingly divided between those seeking to gain what Liberal goals they could achieve, those who preferred a Conservative government to a Labour one and vice versa.

Splits over the National Government

A group of Liberal MPs led by

Sir John Simon

John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon, (28 February 1873 – 11 January 1954), was a British politician who held senior Cabinet posts from the beginning of the First World War to the end of the Second World War. He is one of only three pe ...

opposed the Liberal Party's support for the minority Labour government. They preferred to reach an accommodation with the Conservatives. In 1931 MacDonald's Labour government fell apart in response to the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Macdonald agreed to lead a

National Government of all parties, which passed a budget to deal with the financial crisis. When few Labour MPs backed the National government, it became clear that the Conservatives had the clear majority of government supporters. They then forced MacDonald to call a

general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

. Lloyd George called for the party to leave the National Government but

only a few MPs and candidates followed. The majority, led by

Sir Herbert Samuel

Herbert Louis Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel, (6 November 1870 – 5 February 1963) was a British Liberal politician who was the party leader from 1931 to 1935.

He was the first nominally-practising Jew to serve as a Cabinet minister and to beco ...

, decided to contest the elections as part of the government. The bulk of Liberal MPs supported the government, – the

Liberal Nationals (officially the "National Liberals" after 1947) led by Simon, also known as "Simonites", and the "Samuelites" or "official Liberals", led by Samuel who remained as the official party. Both groups secured about 34 MPs but proceeded to diverge even further after the election, with the Liberal Nationals remaining supporters of the government throughout its life. There were to be a succession of discussions about them rejoining the Liberals, but these usually foundered on the issues of free trade and continued support for the National Government. The one significant reunification came in 1946 when the Liberal and Liberal National party organisations in London merged. The National Liberals, as they were called by then, were gradually absorbed into the Conservative Party, finally merging in 1968.

The official Liberals found themselves a tiny minority within a government committed to

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulation ...

. Slowly they found this issue to be one they could not support. In early 1932 it was agreed to suspend the principle of

collective responsibility

Collective responsibility, also known as collective guilt, refers to responsibilities of organizations, groups and societies. Collective responsibility in the form of collective punishment is often used as a disciplinary measure in closed insti ...

to allow the Liberals to oppose the introduction of tariffs. Later in 1932 the Liberals resigned their ministerial posts over the introduction of the

Ottawa Agreement on

Imperial Preference

Imperial Preference was a system of mutual tariff reduction enacted throughout the British Empire following the Ottawa Conference of 1932. As Commonwealth Preference, the proposal was later revived in regard to the members of the Commonwealth of ...

. However, they remained sitting on the government benches supporting it in Parliament, though in the country local Liberal activists bitterly opposed the government. Finally in late 1933 the Liberals crossed the floor of the House of Commons and went into complete opposition. By this point their number of MPs was severely depleted. In the

1935 general election, just 17 Liberal MPs were elected, along with Lloyd George and three followers as

independent Liberals. Immediately after the election the two groups reunited, though Lloyd George declined to play much of a formal role in his old party. Over the next ten years there would be further defections as MPs deserted to either the Liberal Nationals or Labour. Yet there were a few recruits, such as

Clement Davies

Edward Clement Davies (19 February 1884 – 23 March 1962) was a Welsh politician and leader of the Liberal Party from 1945 to 1956.

Early life and education

Edward Clement Davies was born on 19 February 1884 in Llanfyllin, Montgomeryshire ...

, who had deserted to the National Liberals in 1931 but now returned to the party during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and who would lead it after the war.

Near extinction

Samuel had lost his seat in the

1935 election and the leadership of the party fell to

Sir Archibald Sinclair

Archibald Henry Macdonald Sinclair, 1st Viscount Thurso, (22 October 1890 – 15 June 1970), known as Sir Archibald Sinclair between 1912 and 1952, and often as Archie Sinclair, was a British politician and leader of the Liberal Party.

Backgr ...

. With many traditional domestic Liberal policies now regarded as irrelevant, he focused the party on opposition to both the rise of

Fascism in Europe

Fascism in Europe was the set of various fascist ideologies which were practised by governments and political organisations in Europe during the 20th century. Fascism was born in Italy following World War I, and other fascist movements, inf ...

and the

appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governme ...

foreign policy of the

National Government, arguing that intervention was needed, in contrast to the Labour calls for pacifism. Despite the party's weaknesses, Sinclair gained a high profile as he sought to recall the

Midlothian Campaign and once more revitalise the Liberals as the party of a strong foreign policy.

In 1940, they joined Churchill's wartime coalition government, with Sinclair serving as

Secretary of State for Air