In the

history of medicine

The history of medicine is both a study of medicine throughout history as well as a multidisciplinary field of study that seeks to explore and understand medical practices, both past and present, throughout human societies.

More than just histo ...

, "Islamic medicine" is the

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

of medicine developed in the

Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, ÄÏìÄÇÄÝì ÄÏìÄÈìÄ°Äñ, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, and usually written in

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

, the ''

lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

'' of Islamic civilization.

Islamic medicine adopted, systematized and developed the medical knowledge of

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, including the major traditions of

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ã¥¿üüö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü ç öâñö¢ü, HippokrûÀtás ho KûÇios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

,

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

and

Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, ö öçöÇö˜ö§ö¿ö¢ü öö¿ö¢üö¤ö¢ü

üö₤öÇöñü, ; 40ã90 AD), ãthe father of pharmacognosyã, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) ãa 5-vo ...

.

During the

post-classical era, Middle Eastern medicine was the most advanced in the world, integrating concepts of

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

,

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

,

Mesopotamian

Mesopotamia ''MesopotamûÙá''; ar, Ä´ìììÄÏÄ₤ ìÝìÄÝììÄÏììÄ₤ìììì or ; syc, ÉɈÉÀ ÉÂÉɈäÉÉÂ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the TigrisãEuphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

and

Persian medicine as well as the ancient Indian tradition of

Ayurveda

Ayurveda () is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. The theory and practice of Ayurveda is pseudoscientific. Ayurveda is heavily practiced in India and Nepal, where around 80% of the population rep ...

, while making numerous advances and innovations. Islamic medicine, along with knowledge of

classical medicine, was later adopted in the

medieval medicine of Western Europe, after European physicians became familiar with Islamic medical authors during the

Renaissance of the 12th century

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass idea ...

.

Medieval Islamic physicians largely retained their authority until the rise of

medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

as a part of the

natural sciences

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeat ...

, beginning with the

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: AufklûÊrung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oéwiecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustraciû°n, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

, nearly six hundred years after their textbooks were opened by many people. Aspects of their writings remain of interest to physicians even today.

Overview

Medicine was a central part of medieval Islamic culture. This period was called the Golden Age of Islam and lasted from the eighth century to the fourteenth century.

The economic and social standing of the patient determined to a large extent the type of care sought and the expectations of the patients varied along with the approaches of the practitioners.

Responding to circumstances of time and place/location, Islamic physicians and scholars developed a large and complex medical literature exploring, analyzing, and synthesizing the theory and practice of medicine Islamic medicine was initially built on tradition, chiefly the theoretical and practical knowledge developed in

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, ÄÇìÄ´ììì ÄÏììĘìÄýììÄÝìÄˋì ÄÏììÄ¿ìÄÝìÄ´ììììÄˋ, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Pl ...

and was known at

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, ì

ìÄÙìì

ììÄ₤; 570 ã 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

's time, ancient

Hellenistic medicine

Ancient Greek medicine was a compilation of theories and practices that were constantly expanding through new ideologies and trials. Many components were considered in ancient Greek medicine, intertwining the spiritual with the physical. Specif ...

such as

Unani

Unani or Yunani medicine ( Urdu: ''tibb yé¨náná¨'') is Perso-Arabic traditional medicine as practiced in Muslim culture in South Asia and modern day Central Asia. Unani medicine is pseudoscientific. The Indian Medical Association describes ...

,

ancient Indian

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ancient India:

Ancient India is the Indian subcontinent from prehistoric times to the start of Medieval India, which is typically dated (when the term is still used) to t ...

medicine such as

Ayurveda

Ayurveda () is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. The theory and practice of Ayurveda is pseudoscientific. Ayurveda is heavily practiced in India and Nepal, where around 80% of the population rep ...

, and the

ancient Iranian Medicine

The practice and study of medicine in Persia has a long and prolific history. The Iranian academic centers like Gundeshapur University (3rd century AD) were a breeding ground for the union among great scientists from different civilizations. Thes ...

of the

Academy of Gundishapur

The Academy of Gondishapur ( fa, ìÄÝììÖ₤İĈÄÏì Ö₤ìÄ₤ÜãÄÇÄÏìƒìÄÝ, FarhangestûÂn-e GondiéÀûÂpur), also known as the Gondishapur University (Ä₤ÄÏìÄÇÖ₤ÄÏì Ö₤ìÄ₤ÜãÄÇÄÏìƒìÄÝ DûÂneéÀgûÂh-e GondiéÀapur), was one of the three Sasanian ...

. The works of

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

and

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

physicians

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ã¥¿üüö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü ç öâñö¢ü, HippokrûÀtás ho KûÇios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

,

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

and

Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, ö öçöÇö˜ö§ö¿ö¢ü öö¿ö¢üö¤ö¢ü

üö₤öÇöñü, ; 40ã90 AD), ãthe father of pharmacognosyã, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) ãa 5-vo ...

also had a lasting impact on Middle Eastern medicine. Intellectual thirst, open-mindness, and vigor were at an all time high in this era. During the Golden Age of Islam, classical learning was sought out, systematised and improved upon by scientists and scholars with such diligence that Arab science became the most advanced of its day.

Ophthalmology

Ophthalmology ( ) is a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with the diagnosis and treatment of eye disorders.

An ophthalmologist is a physician who undergoes subspecialty training in medical and surgical eye care. Following a me ...

has been described as the most successful branch of medicine researched at the time, with the works of

Ibn al-Haytham

áÊasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

remaining an authority in the field until early modern times.

History, origins and sources

ÿ˜ibb an-Nabawᨠã Prophetic Medicine

The adoption by the newly forming Islamic society of the medical knowledge of the surrounding, or newly conquered, "heathen" civilizations had to be justified as being in accordance with the beliefs of Islam. Early on, the study and practice of medicine was understood as an act of piety, founded on the principles of ''Imaan'' (faith) and ''Tawakkul'' (trust).

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, ì

ìÄÙìì

ììÄ₤; 570 ã 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mon ...

's opinions on health issues and habits in regard to the leading of a healthy life were collected early on and edited as a separate corpus of writings under the title ''ÿ˜ibb an-Nabá¨'' ("The Medicine of the Prophet"). In the 14th century,

Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ÄýìÄ₤ Ä¿Ä´Ä₤ ÄÏìÄÝÄÙì

ì Ä´ì ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ÄÛìÄ₤ìì ÄÏìÄÙÄÑÄÝì

ì, ; 27 May 1332 ã 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

, in his work ''

Muqaddimah

The ''Muqaddimah'', also known as the ''Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun'' ( ar, ì

ìÄ₤ìì

Äˋ ÄÏÄ´ì ÄÛìÄ₤ìì) or ''Ibn Khaldun's Prolegomena'' ( grc, ö üö¢ö£öçö°üö¥öçö§öÝ), is a book written by the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun in 1377 which records ...

'' provides a brief overview over what he called "the art and craft of medicine", separating the science of medicine from religion:

The

Sahih al-Bukhari

Sahih al-Bukhari ( ar, ÄçÄÙìÄÙ ÄÏìÄ´ÄÛÄÏÄÝì, translit=ÿÂaáËá¨Ã¡Ë al-Bukhárá¨), group=note is a ''hadith'' collection and a book of '' sunnah'' compiled by the Persian scholar MuáËammad ibn Ismáãá¨l al-Bukhárᨠ(810ã870) around 846. A ...

, a collection of prophetic traditions, or ''

hadith

áÊadá¨th ( or ; ar, ÄÙÄ₤ìĨ, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, ÄÈĨÄÝ, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

'' by

Muhammad al-Bukhari

Muhammad ( ar, ì

ìÄÙìì

ììÄ₤; 570 ã 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monoth ...

refers to a collection of Muhammad's opinions on medicine, by his younger contemporary Anas bin-Malik. Anas writes about two physicians who had treated him by

cauterization

Cauterization (or cauterisation, or cautery) is a medical practice or technique of burning a part of a body to remove or close off a part of it. It destroys some tissue in an attempt to mitigate bleeding and damage, remove an undesired growth, or ...

and mentions that the prophet wanted to avoid this treatment and had asked for alternative treatments. Later on, there are reports of the

caliph

A caliphate or khiláfah ( ar, ÄÛìììÄÏììÄˋ, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, ÄÛììììììÄˋ , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

ò¢Uthmán ibn ò¢Affán fixing his teeth with a wire made of gold. He also mentions that the habit of cleaning one's teeth with a small wooden toothpick dates back to pre-Islamic times.

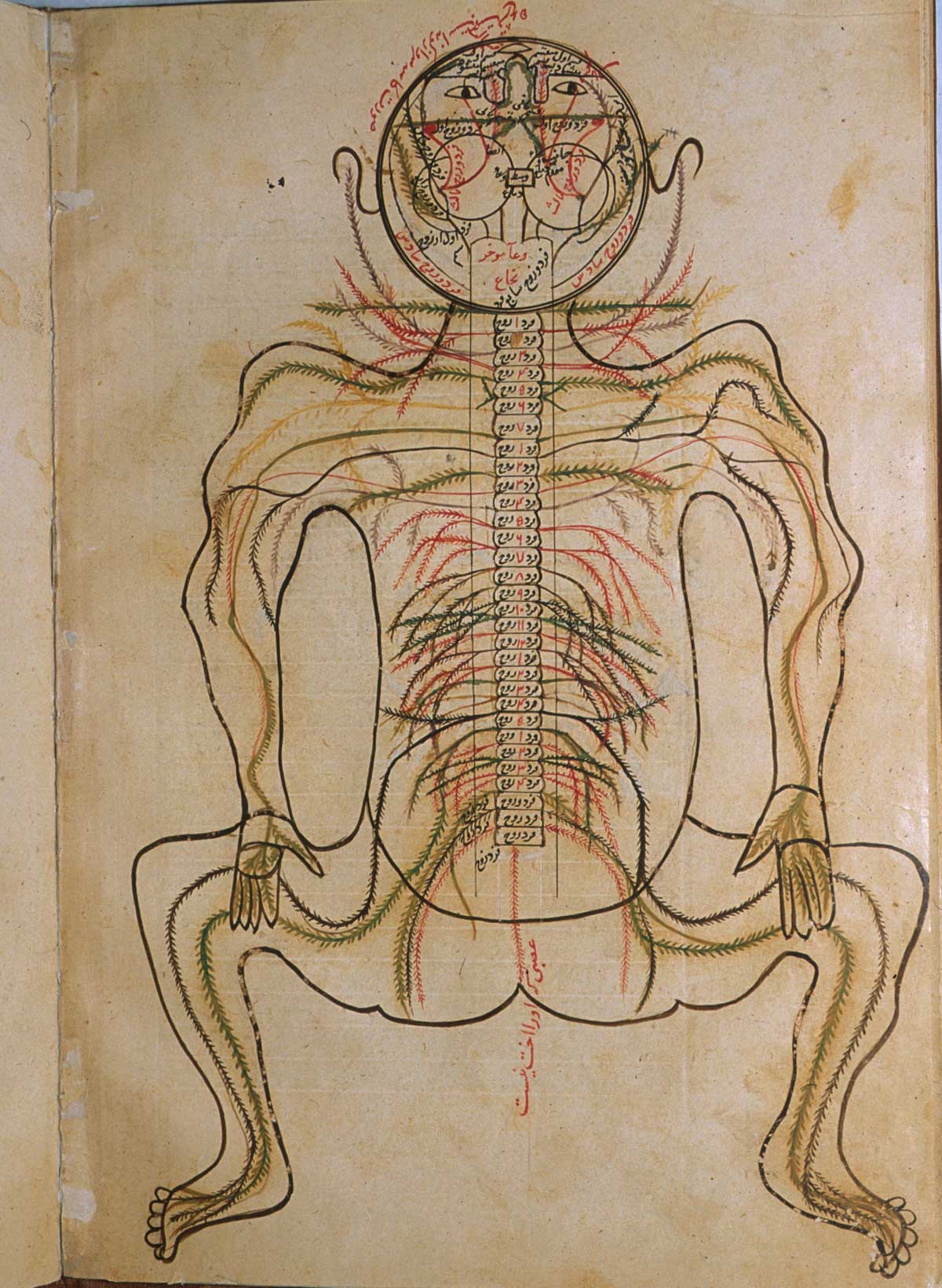

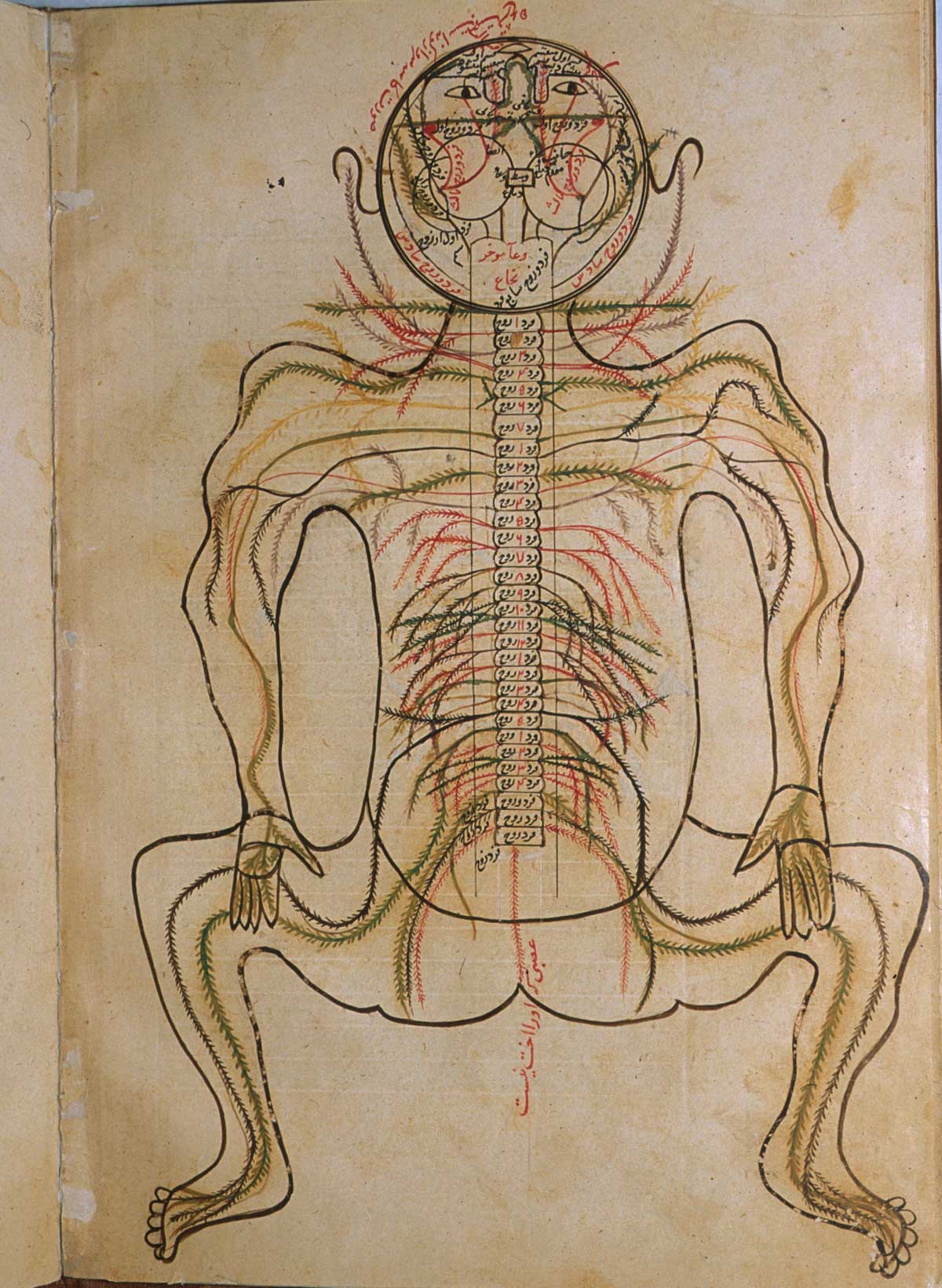

Despite Muhammad's advocacy of medicine, Islam hindered development in human anatomy, regarding the human body as sacred.

Only later, when Persian traditions have been integrated to Islamic thought, Muslims developed treatises about human anatomy.

The "

Prophetic medicine

In Islam, prophetic medicine ( ar, ÄÏìÄñÄ´ ÄÏììÄ´ìì, ') is the advice given by the prophet Muhammad with regards to sickness, treatment and hygiene as found in the hadith. It is usually practiced primarily by non-physician scholars who collec ...

" was rarely mentioned by the classical authors of Islamic medicine, but lived on in the

materia medica for some centuries. In his ''Kitab as-ÿÂaidana'' (Book of Remedies) from the 10./11. century,

Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 ã after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

refers to collected poems and other works dealing with, and commenting on, the materia medica of the old Arabs.

The most famous physician was Al-áÊariÿ₤ ben-Kalada aÿ₤-ÿÛaqafá¨, who lived at the same time as the prophet. He is supposed to have been in touch with the

Academy of Gondishapur

The Academy of Gondishapur ( fa, ìÄÝììÖ₤İĈÄÏì Ö₤ìÄ₤ÜãÄÇÄÏìƒìÄÝ, FarhangestûÂn-e GondiéÀûÂpur), also known as the Gondishapur University (Ä₤ÄÏìÄÇÖ₤ÄÏì Ö₤ìÄ₤ÜãÄÇÄÏìƒìÄÝ DûÂneéÀgûÂh-e GondiéÀapur), was one of the three Sasanian ...

, perhaps he was even trained there. He reportedly had a conversation once with

Khosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, ÞÙÏÞÙËÞÙÛÞÙ¨ÞÙËÞÙÈÞÙˋ; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

Anushirvan about medical topics.

Physicians during the early years of Islam

Most likely, the Arabian physicians became familiar with the Graeco-Roman and late

Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

medicine through direct contact with physicians who were practicing in the newly conquered regions rather than by reading the original or translated works. The translation of the capital of the emerging Islamic world to

Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

may have facilitated this contact, as Syrian medicine was part of that ancient tradition. The names of two Christian physicians are known: Ibn Aÿ₤ál worked at the court of

Muawiyah I

Mu'awiya I ( ar, ì

Ä¿ÄÏììÄˋ Ä´ì ÄÈÄ´ì Ä°ììÄÏì, Muò¢áwiya ibn AbᨠSufyán; ãApril 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

, the founder of the

Umayyad dynasty

Umayyad dynasty ( ar, Ä´ìììì ÄÈìì

ììììÄˋì, Bané¨ Umayya, Sons of Umayya) or Umayyads ( ar, ÄÏìÄÈì

ìììì, al-Umawiyyé¨n) were the ruling family of the Caliphate between 661 and 750 and later of Al-Andalus between 756 and 1031. In the ...

. The caliph abused his knowledge in order to get rid of some of his enemies by way of poisoning. Likewise, Abu l-áÊakam, who was responsible for the preparation of drugs, was employed by Muawiah. His son, grandson, and great-grandson were also serving the Umayyad and

Abbasid caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, ÄÏììÄÛìììÄÏììÄˋì ÄÏììÄ¿ìÄ´ììÄÏÄ°ììììÄˋ, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttal ...

.

These sources testify to the fact that the physicians of the emerging Islamic society were familiar with the classical medical traditions already at the times of the Umayyads. The medical knowledge likely arrived from

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ìÝììÄËìÄ°ìììììÄ₤ìÄÝììììÄˋì ; grc-gre, öö£öçöƒö˜ö§öÇüöçö¿öÝ, AlexûÀndria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, and was probably transferred by Syrian scholars, or translators, finding its way into the Islamic world.

7thã9th century: The adoption of earlier traditions

Very few sources provide information about how the expanding Islamic society received any medical knowledge. A physician called Abdalmalik ben Abgar al-Kinánᨠfrom

Kufa

Kufa ( ar, ÄÏìììììììÄˋ ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000. Currently, Kufa and Najaf a ...

in

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, Ä¿ÜÄÝÄÏì, translit=ûraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, ÖˋÜì

ÄÏÄÝÜ Ä¿ÜÄÝÄÏì, translit=KomarûÛ ûraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to IraqãTurkey border, the north, Iran to IranãIraq ...

is supposed to have worked at the

medical school of Alexandria before he joined

ò¢Umar ibn ò¢Abd al-ò¢Azá¨z's court. ò¢Umar transferred the medical school from Alexandria to

Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ã¥ö§üö¿üüöçö¿öÝ Ã¥À Ã¥üÃ§Ñ Ã§üüö§üö¢ü

, ''Antiû°kheia há epû˜ Orû°ntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ã¥ö§üö¿üüöçö¿öÝ Ã¥À Ã¥üÃ§Ñ Ã§üüö§üö¢ü

; or Ã¥ö§üö¿üüöçö¿öÝ Ã¥À Ã¥üà ...

. It is also known that members of the

Academy of Gondishapur

The Academy of Gondishapur ( fa, ìÄÝììÖ₤İĈÄÏì Ö₤ìÄ₤ÜãÄÇÄÏìƒìÄÝ, FarhangestûÂn-e GondiéÀûÂpur), also known as the Gondishapur University (Ä₤ÄÏìÄÇÖ₤ÄÏì Ö₤ìÄ₤ÜãÄÇÄÏìƒìÄÝ DûÂneéÀgûÂh-e GondiéÀapur), was one of the three Sasanian ...

travelled to Damascus. The Academy of Gondishapur remained active throughout the time of the Abbasid caliphate, though.

An important source from the second half of the 8th century is

Jabir ibn Hayyan

Abé¨ Mé¨sá Jábir ibn áÊayyán (Arabic: , variously called al-ÿÂé¨fá¨, al-Azdá¨, al-Ké¨fá¨, or al-ÿ˜é¨sá¨), died 806ã816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

s "Book of Poisons". He only cites earlier works in Arabic translations, as were available to him, including

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ã¥¿üüö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü ç öâñö¢ü, HippokrûÀtás ho KûÇios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

,

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, ö ö£ö˜üüö§ ; 428/427 or 424/423 ã 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

,

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

,

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, ö ü

ö¡öÝö°üüöÝü ç öÈö˜ö¥ö¿ö¢ü, Pythagû°ras ho SûÀmios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His poli ...

, and

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ã¥üö¿üüö¢üöÙö£öñü ''Aristotûˋlás'', ; 384ã322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, and also mentions the Persian names of some drugs and medical plants.

In 825, the Abbasid caliph

Al-Ma'mun

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ÄÏìÄ¿Ä´ÄÏÄ° Ä¿Ä´Ä₤ ÄÏììì Ä´ì ìÄÏÄÝìì ÄÏìÄÝÄÇìÄ₤, Abé¨ al-ò¢Abbás ò¢Abd Alláh ibn Háré¨n ar-Rashá¨d; 14 September 786 ã 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name Al-Ma'm ...

founded the

House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, Ä´ìĈ ÄÏìÄÙìì

Äˋ, Bayt al-áÊikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

( ar, Ä´ìĈ ÄÏìÄÙìì

Äˋ; ''Bayt al-Hikma'') in

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, Ä´ìĤìÄ₤ìÄÏÄ₤ , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

, modelled after the Academy of Gondishapur. Led by the Christian physician

Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (also Hunain or Hunein) ( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ÄýìÄ₤ ÄÙììì Ä´ì ÄËÄ°ÄÙÄÏì ÄÏìÄ¿Ä´ÄÏÄ₤ì; (809ã873) was an influential Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic ...

, and with support by

Byzance, all available works from the antique world were translated, including

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

,

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ã¥¿üüö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü ç öâñö¢ü, HippokrûÀtás ho KûÇios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

,

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, ö ö£ö˜üüö§ ; 428/427 or 424/423 ã 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

,

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ã¥üö¿üüö¢üöÙö£öñü ''Aristotûˋlás'', ; 384ã322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

,

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, ö üö¢ö£öçö¥öÝâö¢ü, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

and

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientis ...

.

It is currently understood that the early Islamic medicine was mainly informed directly from Greek sources from the

Academy of Alexandria, translated into the Arabic language; the influence of the Persian medical tradition seems to be limited to the materia medica, although the Persian physicians were familiar with the Greek sources as well.

Ancient Greek, Roman, and late hellenistic medical literature

Ancient Greek and Roman texts

Various translations of some works and compilations of ancient medical texts are known from the 7th century.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (also Hunain or Hunein) ( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ÄýìÄ₤ ÄÙììì Ä´ì ÄËÄ°ÄÙÄÏì ÄÏìÄ¿Ä´ÄÏÄ₤ì; (809ã873) was an influential Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic ...

, the leader of a team of translators at the

House of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom ( ar, Ä´ìĈ ÄÏìÄÙìì

Äˋ, Bayt al-áÊikmah), also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, refers to either a major Abbasid public academy and intellectual center in Baghdad or to a large private library belonging to the Abba ...

in Baghdad played a key role with regard to the translation of the entire known corpus of classical medical literature. Caliph

Al-Ma'mun

Abu al-Abbas Abdallah ibn Harun al-Rashid ( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ÄÏìÄ¿Ä´ÄÏÄ° Ä¿Ä´Ä₤ ÄÏììì Ä´ì ìÄÏÄÝìì ÄÏìÄÝÄÇìÄ₤, Abé¨ al-ò¢Abbás ò¢Abd Alláh ibn Háré¨n ar-Rashá¨d; 14 September 786 ã 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name Al-Ma'm ...

had sent envoys to the Byzantine emperor

Theophilos, asking him to provide whatever classical texts he had available. Thus, the great medical texts of

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ã¥¿üüö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü ç öâñö¢ü, HippokrûÀtás ho KûÇios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

and

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

were translated into Arabian, as well as works of

Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, ö ü

ö¡öÝö°üüöÝü ç öÈö˜ö¥ö¿ö¢ü, Pythagû°ras ho SûÀmios, Pythagoras the Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His poli ...

, Akron of Agrigent,

Democritus

Democritus (; el, ööñö¥üö¤üö¿üö¢ü, ''Dámû°kritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; ã ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

, Polybos,

Diogenes of Apollonia

Diogenes of Apollonia ( ; grc, öö¿ö¢ö°öÙö§öñü ç Ã¥üö¢ö£ö£üö§ö¿ö˜üöñü, Diogûˋnás ho ApolléniûÀtás; 5th century BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher, and was a native of the Milesian colony Apollonia in Thrace. He lived for some t ...

, medical works attributed to

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, ö ö£ö˜üüö§ ; 428/427 or 424/423 ã 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

,

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ã¥üö¿üüö¢üöÙö£öñü ''Aristotûˋlás'', ; 384ã322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

,

Mnesitheus of Athens,

Xenocrates

Xenocrates (; el, ööçö§ö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü; c. 396/5314/3 BC) of Chalcedon was a Greek philosopher, mathematician, and leader ( scholarch) of the Platonic Academy from 339/8 to 314/3 BC. His teachings followed those of Plato, which he attempted t ...

,

Pedanius Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, ö öçöÇö˜ö§ö¿ö¢ü öö¿ö¢üö¤ö¢ü

üö₤öÇöñü, ; 40ã90 AD), ãthe father of pharmacognosyã, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) ãa 5-vo ...

, Kriton,

Soranus of Ephesus

Soranus of Ephesus ( grc-gre, öÈüüöÝö§üü ç Ã¥üöÙüö¿ö¢ü; 1st/2nd century AD) was a Greek physician. He was born in Ephesus but practiced in Alexandria and subsequently in Rome, and was one of the chief representatives of the Methodic ...

,

Archigenes,

Antyllus,

Rufus of Ephesus were translated from the original texts, other works including those of

Erasistratos

Erasistratus (; grc-gre, Ã¥üöÝüö₤üüüöÝüö¢ü; c. 304 ã c. 250 BC) was a Greek anatomist and royal physician under Seleucus I Nicator of Syria. Along with fellow physician Herophilus, he founded a school of anatomy in Alexandria, where the ...

were known by their citations in Galen's works.

Late hellenistic texts

The works of

Oribasius, physician to the Roman emperor

Julian, from the 4th century AD, were well known, and were frequently cited in detail by

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abé¨ Bakr al-Rázᨠ(full name: ar, ÄÈÄ´ì Ä´ÖˋÄÝ ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ÄýÖˋÄÝÜÄÏÄÀ ÄÏìÄÝÄÏÄýì, translit=Abé¨ Bakr MuáËammad ibn Zakariyyáòƒ al-Rázá¨, label=none), () rather than ar, ÄýÖˋÄÝÜÄÏÄÀ, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

(Rhazes). The works of

Philagrius of Epirus Philagrius of Epirus ( el, öÎö¿ö£ö˜ö°üö¿ö¢ü ç öüöçö¿üüüöñü; 3rd century CE) was a Greek medical writer from Epirus, who lived after Galen and before Oribasius, and therefore probably in the 3rd century CE. According to the Suda he was a p ...

, who also lived in the 4th century AD, are only known today from quotations by Arabic authors. The philosopher and physician

John the Grammarian, who lived in the 6th century AD was attributed the role of a commentator on the ''Summaria Alexandrinorum''. This is a compilation of 16 books by Galen, but corrupted by superstitious ideas. The physicians

Gessius of Petra and Palladios were equally known to the Arabic physicians as authors of the ''Summaria''. Rhazes cites the Roman physician

Alexander of Tralles (6th century) in order to support his criticism of Galen. The works of

Aû¨tius of Amida

Aû¨tius of Amida (; grc-gre, Ã¥öÙüö¿ö¢ü Ã¥ö¥ö¿öÇöñö§üü; Latin: ''Aû¨tius Amidenus''; fl. mid-5th century to mid-6th century) was a Byzantine Greek physician and medical writer, particularly distinguished by the extent of his erudition. His ...

were only known in later times, as they were neither cited by Rhazes nor by

Ibn al-Nadim

Abé¨ al-Faraj MuáËammad ibn IsáËáq al-Nadá¨m ( ar, ÄÏÄ´ì ÄÏììÄÝĘ ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ÄËÄ°ÄÙÄÏì ÄÏììÄ₤ìì

), also ibn AbᨠYa'qé¨b IsáËáq ibn MuáËammad ibn IsáËáq al-Warráq, and commonly known by the ''nasab'' (patronymic) Ibn al-Nadá¨m ...

, but cited first by

Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 ã after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

in his "Kitab as-Saidana", and translated by Ibn al-Hammar in the 10th century.

One of the first books which were translated from Greek into Syrian, and then into Arabic during the time of the fourth Umayyad caliph

Marwan I

Marwan ibn al-Hakam ibn Abi al-As ibn Umayya ( ar, links=no, ì

ÄÝìÄÏì Ä´ì ÄÏìÄÙìì

Ä´ì ÄÈÄ´ì ÄÏìÄ¿ÄÏÄç Ä´ì ÄÈì

ìÄˋ, Marwán ibn al-áÊakam ibn Abᨠal-ò¢áÃ¿È ibn Umayya), commonly known as MarwanI (623 or 626April/May 685), was the fo ...

by the Jewish scholar Másaráawai al-Basráˋ was the medical compilation ''KunnáéÀ'', by Ahron, who lived during the 6th century. Later on,

Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (also Hunain or Hunein) ( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ÄýìÄ₤ ÄÙììì Ä´ì ÄËÄ°ÄÙÄÏì ÄÏìÄ¿Ä´ÄÏÄ₤ì; (809ã873) was an influential Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic ...

provided a better translation.

The physician

Paul of Aegina

Paul of Aegina or Paulus Aegineta ( el, ö öÝâÎö£ö¢ü öÃ¥¯ö°ö¿ö§öÛüöñü; Aegina, ) was a 7th-century Byzantine Greek physician best known for writing the medical encyclopedia ''Medical Compendium in Seven Books.'' He is considered the ãFather ...

lived in Alexandria during the time of the

Arab expansion

The spread of Islam spans about 1,400 years. Muslim conquests following Muhammad's death led to the creation of the caliphates, occupying a vast geographical area; conversion to Islam was boosted by Arab Muslim forces conquering vast territories ...

. His works seem to have been used as an important reference by the early Islamic physicians, and were frequently cited from Rhazes up to

Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ÄÏÄ´ì Ä°ÜìÄÏ; 980 ã June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

. Paul of Aegina provides a direct connection between the late Hellenistic and the early Islamic medical science.

Arabic translations of Hippocrates

The early Islamic physicians were familiar with the life of

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ã¥¿üüö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü ç öâñö¢ü, HippokrûÀtás ho KûÇios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

and were aware of the fact that his biography was in part a legend. Also they knew that several persons lived who were called Hippocrates, and their works were compiled under one single name:

Ibn an-Nadá¨m has conveyed a short treatise by Tabit ben-Qurra on ''al-Buqratun'' ("the (various persons called) Hippokrates"). Translations of some of Hippocrates's works must have existed before

Hunayn ibn Ishaq

Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-Ibadi (also Hunain or Hunein) ( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ÄýìÄ₤ ÄÙììì Ä´ì ÄËÄ°ÄÙÄÏì ÄÏìÄ¿Ä´ÄÏÄ₤ì; (809ã873) was an influential Nestorian Christian translator, scholar, physician, and scientist. During the apex of the Islamic ...

started his translations, because the historian Al-Yaòƒqé¨bᨠcompiled a list of the works known to him in 872. Fortunately, his list also supplies a summary of the content, quotations, or even the entire text of the single works. The philosopher

Al-Kindi

Abé¨ Yé¨suf Yaò£qé¨b ibn ò¥IsáËáq aÿÈ-ÿÂabbáÃ¡Ë al-Kindᨠ(; ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ììÄ°ì ìÄ¿ììÄ´ Ä´ì ÄËÄ°ÄÙÄÏì ÄÏìÄçÄ´ìÄÏÄÙ ÄÏìììÄ₤ì; la, Alkindus; c. 801ã873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

wrote a book with the title ''at-Tibb al-Buqrati'' (The Medicine of Hippocrates), and his contemporary Hunayn ibn Isháq then translated Galens commentary on

Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ã¥¿üüö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü ç öâñö¢ü, HippokrûÀtás ho KûÇios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

. Rhazes is the first Arabic-writing physician who makes thorough use of Hippocrates's writings in order to set up his own medical system.

Al-Tabari

( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ĘĿìÄÝ ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ĘÄÝìÄÝ Ä´ì ìÄýìÄ₤ ÄÏìÄñÄ´ÄÝì), more commonly known as al-ÿ˜abarᨠ(), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

maintained that his compilation of hippocratic teachings (''al-MuòƒálaáÀát al-buqráÿÙá¨ya'') was a more appropriate summary. The work of Hippocrates was cited and commented on during the entire period of medieval Islamic medicine.

Arabic translations of Galen

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

is one of the most famous scholars and physicians of

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

. Today, the original texts of some of his works, and details of his biography, are lost, and are only known to us because they were translated into Arabic.

Jabir ibn Hayyan

Abé¨ Mé¨sá Jábir ibn áÊayyán (Arabic: , variously called al-ÿÂé¨fá¨, al-Azdá¨, al-Ké¨fá¨, or al-ÿ˜é¨sá¨), died 806ã816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

frequently cites Galen's books, which were available in early Arabic translations. In 872 AD,

Ya'qubi

òƒAbé¨ l-ò¢Abbás òƒAáËmad bin òƒAbᨠYaò¢qé¨b bin úÎaò¢far bin Wahb bin Waáá¨Ã¡Ë al-Yaò¢qé¨bᨠ(died 897/8), commonly referred to simply by his nisba al-Yaò¢qé¨bá¨, was an Arab Muslim geographer and perhaps the first historian of world cul ...

refers to some of Galen's works. The titles of the books he mentions differ from those chosen by Hunayn ibn Isháq for his own translations, thus suggesting earlier translations must have existed. Hunayn frequently mentions in his comments on works which he had translated that he considered earlier translations as insufficient, and had provided completely new translations. Early translations might have been available before the 8th century; most likely they were translated from Syrian or Persian.

Within medieval Islamic medicine, Hunayn ibn Isháq and his younger contemporary Tabit ben-Qurra play an important role as translators and commentators of Galen's work. They also tried to compile and summarize a consistent medical system from these works, and add this to the medical science of their period. However, starting already with Jabir ibn Hayyan in the 8th century, and even more pronounced in Rhazes's treatise on vision, criticism of Galen's ideas took on. in the 10th century, the physician

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi wrote:

Syrian and Persian medical literature

Syrian texts

During the 10th century,

Ibn Wahshiyya

( ar, ÄÏÄ´ì ìÄÙÄÇìÄˋ), died , was a Nabataean (Aramaic-speaking, rural Iraqi) agriculturalist, toxicologist, and alchemist born in Qussá¨n, near Kufa in Iraq. He is the author of the '' Nabataean Agriculture'' (), an influential Arabic work ...

compiled writings by the

Nabataeans

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (; Nabataean Aramaic: , , vocalized as ; Arabic language, Arabic: , , singular , ; compare grc, ööÝöýöÝüöÝâö¢ü, translit=NabataûÛos; la, Nabataeus) were an ancient Arab people who inhabited northern Arabian Pe ...

, including also medical information. The Syrian scholar

Sergius of Reshaina Sergius of Reshaina (died 536) was a physician and priest during the 6th century. He is best known for translating medical works from Greek to Syriac, which were eventually, during the Abbasid Caliphate of the late 8th- & 9th century, translated in ...

translated various works by Hippocrates and Galen, of whom parts 6ã8 of a pharmacological book, and fragments of two other books have been preserved. Hunayn ibn Isháq has translated these works into Arabic. Another work, still existing today, by an unknown Syrian author, likely has influenced the Arabic-writing physicians

Al-Tabari

( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ĘĿìÄÝ ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ĘÄÝìÄÝ Ä´ì ìÄýìÄ₤ ÄÏìÄñÄ´ÄÝì), more commonly known as al-ÿ˜abarᨠ(), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

and

Yé¨hanná ibn Másawaiyh.

The earliest known translation from the Syrian language is the ''KunnáéÀ'' of the scholar Ahron (who himself had translated it from the Greek), which was translated into the Arabian by Másaráawai al-Basráˋ in the 7th century.

yriac-language, not Syrian, who were Nestoriansphysicians also played an important role at the

Academy of Gondishapur

The Academy of Gondishapur ( fa, ìÄÝììÖ₤İĈÄÏì Ö₤ìÄ₤ÜãÄÇÄÏìƒìÄÝ, FarhangestûÂn-e GondiéÀûÂpur), also known as the Gondishapur University (Ä₤ÄÏìÄÇÖ₤ÄÏì Ö₤ìÄ₤ÜãÄÇÄÏìƒìÄÝ DûÂneéÀgûÂh-e GondiéÀapur), was one of the three Sasanian ...

; their names were preserved because they worked at the court of the

Abbasid caliphs.

Persian texts

Again

the Academy of Gondishapur played an important role, guiding the transmission of Persian medical knowledge to the Arabic physicians. Founded, according to

Gregorius Bar-Hebraeus, by the

Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

ruler

Shapur I

Shapur I (also spelled Shabuhr I; pal, ÞÙÝÞÙÏÞÙ₤ÞÙËÞÙÏÞÙËÞÙˋ, é ábuhr ) was the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran. The dating of his reign is disputed, but it is generally agreed that he ruled from 240 to 270, with his father Ardas ...

during the 3rd century AD, the academy connected the ancient Greek and

Indian medical traditions. Arabian physicians trained in Gondishapur may have established contacts with early Islamic medicine. The treatise ''Abdál al-adwiya'' by the Christian physician Másaráawai (not to be confused with the translator M. al-Basráˋ) is of some importance, as the opening sentence of his work is:

In his work ''Firdaus al-Hikma'' (The Paradise of Wisdom),

Al-Tabari

( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ĘĿìÄÝ ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ĘÄÝìÄÝ Ä´ì ìÄýìÄ₤ ÄÏìÄñÄ´ÄÝì), more commonly known as al-ÿ˜abarᨠ(), was a Muslim historian and scholar from Amol, Tabaristan. Among the most prominent figures of the Islamic Golden Age, al-Tabari ...

uses only a few Persian medical terms, especially when mentioning specific diseases, but a large number of drugs and medicinal herbs are mentioned using their Persian names, which have also entered the medical language of Islamic medicine. As well as al-Tabari, Rhazes rarely uses Persian terms, and only refers to two Persian works: ''KunnáéÀ fárisi'' und ''al-Filáha al-fárisiya''.

Indian medical literature

Indian scientific works, e.g. on

Astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution. Objects of interest include planets, moons, stars, nebulae, g ...

were already translated by

Yaò¢qé¨b ibn ÿ˜áriq

Yaò¢qé¨b ibn ÿ˜áriq (; died AD) was an 8th-century Persian astronomer and mathematician who lived in Baghdad.

Works

Works ascribed to Yaò¢qé¨b ibn ÿ˜áriq include:Plofker

* (, "Astronomical tables in the ''Sindhind'' resolved for each degr ...

and

MuáËammad ibn Ibráhá¨m al-Fazárᨠduring the times of the

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, ÄÏììÄÛìììÄÏììÄˋì ÄÏììÄ¿ìÄ´ììÄÏÄ°ììììÄˋ, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

caliph

Al-Mansur

Abé¨ Jaò¢far ò¢Abd Alláh ibn MuáËammad al-ManÿÈé¨r (; ar, ÄÈÄ´ì ĘĿìÄÝ Ä¿Ä´Ä₤ ÄÏììì Ä´ì ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ ÄÏìì

ìÄçìÄÝ; 95 AH ã 158 AH/714 CE ã 6 October 775 CE) usually known simply as by his laqab Al-ManÿÈé¨r (ÄÏìì

ìÄçìÄÝ) ...

. Under

Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, ÄÈÄ´ì ĘĿìÄÝ ìÄÏÄÝìì ÄÏÄ´ì ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ ÄÏìì

ìÄ₤ì) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 ã 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, ììÄÏÄÝììì ÄÏìÄÝìÄÇììÄ₤, translit=Háré¨n ...

, at latest, the first translations were performed of Indian works about medicine and pharmacology. In one chapter on

Indian medicine,

Ibn al-Nadim

Abé¨ al-Faraj MuáËammad ibn IsáËáq al-Nadá¨m ( ar, ÄÏÄ´ì ÄÏììÄÝĘ ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ÄËÄ°ÄÙÄÏì ÄÏììÄ₤ìì

), also ibn AbᨠYa'qé¨b IsáËáq ibn MuáËammad ibn IsáËáq al-Warráq, and commonly known by the ''nasab'' (patronymic) Ibn al-Nadá¨m ...

mentions the names of three of the translators: Mankah, Ibn Dahn, and òƒAbdallah ibn òƒAlá¨.

Yé¨hanná ibn Másawaiyh cites an Indian textbook in his treatise on ophthalmology.

al-Tabarᨠdevotes the last 36 chapters of his ''Firdaus al-Hikmah'' to describe the Indian medicine, citing

Sushruta

Sushruta, or ''Suéruta'' (Sanskrit: ÁÊ¡ÁËÁÊÑÁËÁʯÁËÁÊÊ, IAST: , ) was an ancient Indian physician. The '' Sushruta Samhita'' (''Sushruta's Compendium''), a treatise ascribed to him, is one of the most important surviving ancient treatises o ...

,

Charaka

Charaka was one of the principal contributors to Ayurveda, a system of medicine and lifestyle developed in Ancient India. He is known as an editor of the medical treatise entitled ''Charaka Samhita'', one of the foundational texts of classical ...

, and the ''Ashtanga Hridaya'' (

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

: ÁÊ

ÁÊñÁËÁÊÁʃÁÊÁÊ ÁÊ¿ÁËÁÊÎÁÊ₤, ; "The eightfold Heart"), one of the most important books on Ayurveda, translated between 773 and 808 by Ibn-Dhan. Rhazes cites in ''al-Hawi'' and in ''Kitab al-Mansuri'' both Sushruta and Charaka besides other authors unknown to him by name, whose works he cites as ''"min kitab al-Hind"'', ãan Indian book".

Meyerhof suggested that the Indian medicine, like the Persian medicine, has mainly influenced the Arabic ''

materia medica'', because there is frequent reference to Indian names of herbal medicines and drugs which were unknown to the Greek medical tradition. Whilst Syrian physicians transmitted the medical knowledge of the ancient Greeks, most likely Persian physicians, probably from the Academy of Gondishapur, were the first intermediates between the Indian and the Arabic medicine

Recent studies have shown that a number Ayurvedic texts were translated into Persian in South Asia from the 14th century until the Colonial period. From the 17th century onward, many Hindu physicians learnt Persian language and wrote Persian medical texts dealing with both Indian and Muslim medical materials (Speziale 2014, 2018, 2020).

Approach to medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

in the medieval Islamic world was often directly related to

horticulture

Horticulture is the branch of agriculture that deals with the art, science, technology, and business of plant cultivation. It includes the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, herbs, sprouts, mushrooms, algae, flowers, seaweeds and no ...

.

Fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in partic ...

s and

vegetable

Vegetables are parts of plants that are consumed by humans or other animals as food. The original meaning is still commonly used and is applied to plants collectively to refer to all edible plant matter, including the edible flower, flowers, ...

s were related to health and well being, although they were seen as having different properties than what modern medicine says now.

The use of the humoral theory is also a large part of medicine in this period, shaping the diagnosis and treatments for patients. This kind of medicine was largely

holistic

Holism () is the idea that various systems (e.g. physical, biological, social) should be viewed as wholes, not merely as a collection of parts. The term "holism" was coined by Jan Smuts in his 1926 book '' Holism and Evolution''."holism, n." OED On ...

, focused on on

schedule

A schedule or a timetable, as a basic time-management tool, consists of a list of times at which possible tasks, events, or actions are intended to take place, or of a sequence of events in the chronological order in which such things are ...

, environment, and diet. As a result, medicine was very individualistic as every person who sought medical help would receive different advice dependent not only on their ailment, but also according to their lifestyle. There was still some connection between treatments however, as medicine was largely based on humoral theory which meant that each person needed to be treated according to whether or not their humors were hot, cold, melancholic, or choleric.

Horticulture

The use of plants in medicine was quite common in this era with most plants being used in medicine being associated with both some benefits and consequences for use as well as certain situations in which they should be used.

This was due to the association between certain plants with hot or cold properties, i.e "cool as a cucumber" or a hot pepper.

Thus, hot ailments such as a fever should be addressed by consuming a cucumber and a cool ailment such as a significant amount of phlegm should be treated with the pepper.

Physicians and scientists

The authority of the great physicians and scientists of the Islamic Golden age has influenced the art and science of medicine for many centuries. Their concepts and ideas about medical ethics are still discussed today, especially in the Islamic parts of our world. Their ideas about the conduct of physicians, and the

doctorãpatient relationship are discussed as potential role models for physicians of today.

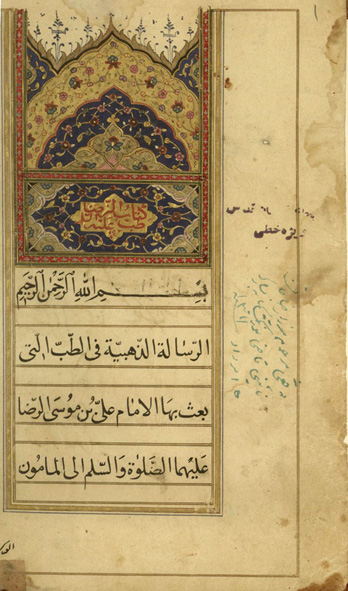

Imam Ali ibn Musa al-Rida

Ali ibn Musa al-Rida

Ali ibn Musa al-Rida ( ar, Ä¿ììììì ìÝÄ´ìì ì

ììÄ°ììì¯ ìÝìÄÝììÄÑìÄÏ, Alᨠibn Mé¨sá al-Riáá, 1 January 766 ã 6 June 818), also known as Abé¨ al-áÊasan al-Tháná¨, was a descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and the ...

(765ã818) is the 8th Imam of the Shia. His treatise "

Al-Risalah al-Dhahabiah

''Al-Risalah al-Dhahabiah'' ( ar, ìÝìÄÝììÄ°ìÄÏììÄˋ ìÝìįììììÄ´ììììÄˋ, ; "The Golden Treatise") is a medical dissertation on health and remedies attributed to Ali ibn Musa al-Ridha (765–818), the eighth Imam of Shia. He w ...

" ("The Golden Treatise") deals with medical cures and the maintenance of good health, and is dedicated to the caliph

Ma'mun.

It was regarded at his time as an important work of literature in the science of medicine, and the most precious medical treatise from the point of view of Muslimic religious tradition. It is honoured by the title "the golden treatise" as Ma'mun had ordered it to be written in gold ink.

In his work, Al-Ridha is influenced by the concept of

humoral medicine

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari

The first encyclopedia of medicine in Arabic language was by Persian scientist

Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari's ''Firdous al-Hikmah'' (''"Paradise of Wisdom"''), written in seven parts, c. 860 dedicated to Caliph al-Mutawakkil. His encyclopedia was influenced by Greek sources, Hippocrates, Galen, Aristotle, and Dioscurides. Al-Tabari, a pioneer in the field of

child development

Child development involves the Human development (biology), biological, developmental psychology, psychological and emotional changes that occur in human beings between birth and the conclusion of adolescence. Childhood is divided into 3 stages o ...

, emphasized strong ties between

psychology

Psychology is the science, scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immens ...

and medicine, and the need for

psychotherapy

Psychotherapy (also psychological therapy, talk therapy, or talking therapy) is the use of psychological methods, particularly when based on regular personal interaction, to help a person change behavior, increase happiness, and overcome pro ...

and

counseling

Counseling is the professional guidance of the individual by utilizing psychological methods especially in collecting case history data, using various techniques of the personal interview, and testing interests and aptitudes.

This is a list of co ...

in the therapeutic treatment of patients. His encyclopedia also discussed the influence of

Sushruta

Sushruta, or ''Suéruta'' (Sanskrit: ÁÊ¡ÁËÁÊÑÁËÁʯÁËÁÊÊ, IAST: , ) was an ancient Indian physician. The '' Sushruta Samhita'' (''Sushruta's Compendium''), a treatise ascribed to him, is one of the most important surviving ancient treatises o ...

and

Charaka

Charaka was one of the principal contributors to Ayurveda, a system of medicine and lifestyle developed in Ancient India. He is known as an editor of the medical treatise entitled ''Charaka Samhita'', one of the foundational texts of classical ...

on medicine, including psychotherapy.

Muhammad bin Sa'id al-Tamimi

Al-Tamimi, the physician

Muhammad ibn Sa'id al-Tamimi ( ar, ÄÈÄ´ì Ä¿Ä´Ä₤ ÄÏììì ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì Ä°Ä¿ìÄ₤ ÄÏìĈì

ìì

ì), (died 990), known by his kunya, "Abu Abdullah," but more commonly as Al-Tamimi, the physician, was a tenth-century physician, who came to renown o ...

(d. 990) became renown for his skills in compounding medicines, especially

theriac, an antidote for poisons. His works, many of which no longer survive, are cited by later physicians. Taking what was known at the time by the classical Greek writers, Al-Tamimi expanded on their knowledge of the properties of plants and minerals, becoming ''

avant garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or 'vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical D ...

'' in his field.

Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi (died 994 AD), also known as Haly Abbas, was famous for the Kitab al-Maliki translated as the ''

Complete Book of the Medical Art

''The Complete Book of the Medical Art'' ( ar, ìÄÏì

ì ÄÏìÄçìÄÏÄ¿Äˋ ÄÏìÄñÄ´ìÄˋ, ''Kámil al-ÿÈináò£a al-ÿÙibbá¨ya'') also known as ''The Royal Book'' ( ar, ÄÏììĈÄÏÄ´ ÄÏìì

ììì, ''Al-Kitáb al-Malaká¨'') was written by Iranian physici ...

'' and later, more famously known as ''The Royal Book''. Considered one of the great classical works of Islamic medicine, it was free of magical and astrological ideas and thought to represent Galenism of Arabic medicine in the purest form. This book was translated by Constantine and was used as a textbook of surgery in schools across Europe. ''The Royal Book'' has maintained the same level of fame as Avicenna's ''Canon'' throughout the Middle Ages and into modern time. One of the greatest contributions Haly Abbas made to medical science was his description of the capillary circulation found within the Royal Book.

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abé¨ Bakr al-Rázᨠ(full name: ar, ÄÈÄ´ì Ä´ÖˋÄÝ ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ÄýÖˋÄÝÜÄÏÄÀ ÄÏìÄÝÄÏÄýì, translit=Abé¨ Bakr MuáËammad ibn Zakariyyáòƒ al-Rázá¨, label=none), () rather than ar, ÄýÖˋÄÝÜÄÏÄÀ, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

(Latinized: Rhazes) (born 865) was one of the most versatile scientists of the Islamic Golden Age. A Persian-born physician, alchemist and philosopher, he is most famous for his medical works, but he also wrote botanical and zoological works, as well as books on physics and mathematics. His work was highly respected by the 10th/11th century physicians and scientists

al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 ã after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

and

al-Nadim

Abé¨ al-Faraj MuáËammad ibn IsáËáq al-Nadá¨m ( ar, ÄÏÄ´ì ÄÏììÄÝĘ ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä´ì ÄËÄ°ÄÙÄÏì ÄÏììÄ₤ìì

), also ibn AbᨠYa'qé¨b IsáËáq ibn MuáËammad ibn IsáËáq al-Warráq, and commonly known by the ''nasab'' (patronymic) Ibn al-Nadá¨m ...

, who recorded biographical information about al-Razi, and compiled lists of, and provided commentaries on, his writings. Many of his books were translated into Latin, and he remained one of the undisputed authorities in European medicine well into the 17th century.

In medical theory, al-Razi relied mainly on

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

, but his particular attention to the individual case, stressing that each patient must be treated individually, and his emphasis on hygiene and diet reflect the ideas and concepts of the empirical

hippocratic

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ã¥¿üüö¢ö¤üö˜üöñü ç öâñö¢ü, HippokrûÀtás ho KûÇios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of ...

school. Rhazes considered the influence of the climate and the season on health and well-being, he took care that there was always clean air and an appropriate temperature in the patients' rooms, and recognized the value of prevention as well as the need for a careful diagnosis and prognosis.

Kitab-al Hawi fi al-tibb (Liber continens)

The ''kitab-al Hawi fi al-tibb'' (''al-Hawi'' ''ÄÏìÄÙÄÏìì'', Latinized: ''The Comprehensive book of medicine'', ''Continens Liber'', ''The Virtuous Life'') was one of al-Razi's largest works, a collection of medical notes that he made throughout his life in the form of extracts from his reading and observations from his own medical experience.

In its published form, it consists of 23 volumes. Al-Razi cites Greek, Syrian, Indian and earlier Arabic works, and also includes medical cases from his own experience. Each volume deals with specific parts or diseases of the body.

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi reviewed the ''al-Hawi'' in his own book ''Kamil as-sina'a'':

''Al-Hawi'' remained an authoritative textbook on medicine in most

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an universities, regarded until the seventeenth century as the most comprehensive work ever written by a medical scientist.

It was first translated into Latin in 1279 by

Faraj ben Salim, a physician of Sicilian-Jewish origin employed by

Charles of Anjou

Charles I (early 1226/12277 January 1285), commonly called Charles of Anjou, was a member of the royal Capetian dynasty and the founder of the second House of Anjou. He was Count of Provence (1246ã85) and Forcalquier (1246ã48, 1256ã85) ...

.

Kitab al-Mansuri (Liber ad Almansorem)

The ''al-Kitab al-Mansuri'' (ÄÏììĈÄÏÄ´ ÄÏìì

ìÄçìÄÝì ìì ÄÏìÄñÄ´, Latinized: ''Liber almansoris'', ''Liber medicinalis ad Almansorem'') was dedicated to "the

Samanid

The Samanid Empire ( fa, Ä°ÄÏì

ÄÏìÜÄÏì, Sámániyán) also known as the Samanian Empire, Samanid dynasty, Samanid amirate, or simply as the Samanids) was a Persianate Sunni Muslim empire, of Iranian dehqan origin. The empire was centred in ...

prince Abu Salih al-Mansur ibn Ishaq, governor of

Rayy."

The book contains a comprehensive encyclopedia of medicine in ten sections. The first six sections are dedicated to medical theory, and deal with anatomy, physiology and pathology, materia medica, health issues, dietetics, and cosmetics. The remaining four parts describe surgery, toxicology, and fever. The ninth section, a detailed discussion of medical pathologies arranged by body parts, circulated in autonomous Latin translations as the ''Liber Nonus''.

comments on the ''al-Mansuri'' in his book ''Kamil as-sina'a'':

The book was first translated into Latin in 1175 by

Gerard of Cremona

Gerard of Cremona (Latin: ''Gerardus Cremonensis''; c. 1114 ã 1187) was an Italian translator of scientific books from Arabic into Latin. He worked in Toledo, Kingdom of Castile and obtained the Arabic books in the libraries at Toledo. Some of ...

. Under various titles ("Liber (medicinalis) ad Almansorem"; "Almansorius"; "Liber ad Almansorem"; "Liber nonus") it was printed in

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

in 1490, 1493, and 1497. Amongst the many European commentators on the Liber nonus,

Andreas Vesalius

Andreas Vesalius (Latinized from Andries van Wezel) () was a 16th-century anatomist, physician, and author of one of the most influential books on human anatomy, ''De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric of the human body'' ' ...

paraphrased al-Razi's work in his ''"Paraphrases in nonum librum Rhazae"'', which was first published in Louvain, 1537.

Kitab Tibb al-Muluki (Liber Regius)

Another work of al-Razi is called the ''Kitab Tibb al-Muluki'' (''Regius''). This book covers the treatments and cures of diseases and ailments, through dieting. It is thought to have been written for the noble class who were known for their gluttonous behavior and who frequently became ill with stomach diseases.

Kitab al-Jadari wa-l-hasba (De variolis et morbillis)

Until the discovery of Tabit ibn Qurras earlier work, al-Razi's treatise on

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

and

measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10ã12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7ã10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

was considered the earliest monograph on these infectious diseases. His careful description of the initial symptoms and clinical course of the two diseases, as well as the treatments he suggests based on the observation of the symptoms, is considered a masterpiece of Islamic medicine.

Other works

Other works include ''A Dissertation on the causes of the Coryza which occurs in the spring when roses give forth their scent'', a tract in which al-Razi discussed why it is that one contracts coryza or common cold by smelling roses during the spring season,

and ''Burãal Saãa'' (''Instant cure'') in which he named medicines which instantly cured certain diseases.

Abu-Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdullah ibn-Sina (Avicenna)

''

Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ÄÏÄ´ì Ä°ÜìÄÏ; 980 ã June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islami ...

'', more commonly known in west as

Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ÄÏÄ´ì Ä°ÜìÄÏ; 980 ã June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

was a Persian polymath and physician of the tenth and eleventh centuries. He was known for his scientific works, but especially his writing on medicine.

He has been described as the "Father of Early Modern Medicine". Ibn Sina is credited with many varied medical observations and discoveries such as recognizing the potential of airborne transmission of disease, providing insight into many psychiatric conditions, recommending use of

forceps

Forceps (plural forceps or considered a plural noun without a singular, often a pair of forceps; the Latin plural ''forcipes'' is no longer recorded in most dictionaries) are a handheld, hinged instrument used for grasping and holding objects. Fo ...

in deliveries complicated by fetal distress, distinguishing central from peripheral

facial paralysis and describing

guinea worm

''Dracunculus medinensis'', or Guinea worm, is a nematode that causes dracunculiasis, also known as guinea worm disease. The disease is caused by the female which, at up to in length, is among the longest nematodes infecting humans. In contr ...

infection and

trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN or TGN), also called Fothergill disease, tic douloureux, or trifacial neuralgia is a long-term pain disorder that affects the trigeminal nerve, the nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as ...

.

He is credited for writing two books in particular: his most famous, ''al-Canon fi al Tibb'' (''

The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' ( ar, ÄÏììÄÏììì ìì ÄÏìÄñÄ´, italic=yes ''al-Qáné¨n fᨠal-ÿ˜ibb''; fa, ìÄÏììì Ä₤ÄÝ ÄñÄ´, italic=yes, ''Qanun-e dûÂr TûÂb'') is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Persian physician-phi ...

''), and also ''

The Book of Healing''. His other works cover subjects including

angelology, heart medicines and treatment of kidney diseases.

Avicenna's medicine became the representative of Islamic medicine mainly through the influence of his famous work ''al-Canon fi al Tibb'' (''The Canon of Medicine'').

The book was originally used as a textbook for instructors and students of medical sciences in the medical school of Avicenna.

The book is divided into 5 volumes:

The first volume is a compendium of medical principles, the second is a reference for individual drugs, the third contains organ-specific diseases, the fourth discusses systemic illnesses as well as a section of preventive health measures, and the fifth contains descriptions of compound medicines.

The ''Canon'' was highly influential in medical schools and on later medical writers.

Ibn BuÿÙlán - Yawáná¨s al-Mukhtár ibn al-áÊasan ibn ò¢Abdé¨n al-Baghdádᨠ(Ibn Butlan)

''

Ibn BuÿÙlán'', otherwise known as Yawáná¨s al-Mukhtár ibn al-áÊasan ibn ò¢Abdé¨n al-Baghdádá¨, was an

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, Ä¿ìÄÝìÄ´ìììì, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, Ä¿ìÄÝìÄ´, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

physician who was active in

Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, Ä´ìĤìÄ₤ìÄÏÄ₤ , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

during the

Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

.

[Ibn Butlan's Tacuinum sanitatis in medicina. Strassburg, 1531.]

/ref> He is known as an author of the '' Taqwim al-Sihhah'' (''The Maintenance of Health'' Ĉìììì

ÄÏìÄçÄÙÄˋ), in the West, best known under its Latinized translation, ''Tacuinum Sanitatis'' (sometimes ''Taccuinum Sanitatis'').

The work treated matters of hygiene

Hygiene is a series of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

, dietetics

A dietitian, medical dietitian, or dietician is an expert in identifying and treating disease-related malnutrition and in conducting medical nutrition therapy, for example designing an enteral tube feeding regimen or mitigating the effects of ...

, and exercise

Exercise is a body activity that enhances or maintains physical fitness and overall health and wellness.

It is performed for various reasons, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardiovascular system, hone athletic ...

. It emphasized the benefits of regular attention to the personal physical and mental well-being. The continued popularity and publication of his book into the sixteenth century is thought to be demonstration of the influence that Arabic culture

Arab culture is the culture of the Arabs, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Sea in the east, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the north to the Horn of Africa and the Indian Ocean in the southeast. The various religions the Arab ...

had on early modern Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

.

Medical contributions

Human anatomy and physiology

It is claimed that an important advance in the knowledge of human anatomy and physiology was made by Ibn al-Nafis, but whether this was discovered via human dissection is doubtful because "al-Nafis tells us that he avoided the practice of dissection because of the shari'a and his own 'compassion' for the human body".

It is claimed that an important advance in the knowledge of human anatomy and physiology was made by Ibn al-Nafis, but whether this was discovered via human dissection is doubtful because "al-Nafis tells us that he avoided the practice of dissection because of the shari'a and his own 'compassion' for the human body".Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

in the 2nd century, blood reached the left ventricle through invisible passages in the septum.pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulation is a division of the circulatory system in all vertebrates. The circuit begins with deoxygenated blood returned from the body to the right atrium of the heart where it is pumped out from the right ventricle to the lungs ...

,William Harvey

William Harvey (1 April 1578 ã 3 June 1657) was an English physician who made influential contributions in anatomy and physiology. He was the first known physician to describe completely, and in detail, the systemic circulation and propert ...

's later independent discovery which brought it to general attention.Ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ã¥ö£ö£ö˜ü, HellûÀs) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12thã9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, vision was thought to a visual spirit emanating from the eyes that allowed an object to be perceived.Ibn al-Haytham

áÊasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

, also known as Al-hazen in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, developed a radically new concept of human vision.Book of Optics

The ''Book of Optics'' ( ar, ìĈÄÏÄ´ ÄÏìì

ìÄÏÄ¡ÄÝ, Kitáb al-Manáäir; la, De Aspectibus or ''Perspectiva''; it, Deli Aspecti) is a seven-volume treatise on optics and other fields of study composed by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn al- ...

'' was translated into Latin and continued to be studied both in the Islamic world and in Europe until the 17th century.Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, öö£öÝüöÇö¿ö¢ü ööÝö£öñö§üü; September 129 ã c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

, in his work entitled ''De ossibus ad tirones'', the lower jaw consists of two parts, proven by the fact that it disintegrates in the middle when cooked. Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi

ò¢Abd al-LaÿÙá¨f al-Baghdádᨠ( ar, Ä¿Ä´Ä₤ÄÏììÄñìì ÄÏìĴĤÄ₤ÄÏÄ₤ì, 1162 Baghdadã1231 Baghdad), short for Muwaffaq al-Dá¨n MuáËammad ò¢Abd al-LaÿÙá¨f ibn Yé¨suf al-Baghdádᨠ( ar, ì

ììì ÄÏìÄ₤ìì ì

ÄÙì

Ä₤ Ä¿Ä´Ä₤ ÄÏììÄñìì Ä´ì ...

, while on a visit to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, ì

ÄçÄÝ , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, encountered many skeletal remains of those who had died from starvation near Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, ÄÏììÄÏìÄÝÄˋ, al-Qáhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

. He examined the skeletons and established that the mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

consists of one piece, not two as Galen had taught.

Drugs

Medical contributions made by medieval Islam included the use of plants as a type of remedy or medicine. Medieval Islamic physicians used natural substances as a source of medicinal drugsãincluding ''Papaver somniferum'' Linnaeus, poppy

A poppy is a flowering plant in the subfamily Papaveroideae of the family Papaveraceae. Poppies are herbaceous plants, often grown for their colourful flowers. One species of poppy, '' Papaver somniferum'', is the source of the narcotic drug o ...

, and ''Cannabis sativa'' Linnaeus, hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of '' Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants ...

.hemp

Hemp, or industrial hemp, is a botanical class of '' Cannabis sativa'' cultivars grown specifically for industrial or medicinal use. It can be used to make a wide range of products. Along with bamboo, hemp is among the fastest growing plants ...

was known.India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

through Persia and Greek culture and medical literature.Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, ö öçöÇö˜ö§ö¿ö¢ü öö¿ö¢üö¤ö¢ü

üö₤öÇöñü, ; 40ã90 AD), ãthe father of pharmacognosyã, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) ãa 5-vo ...

, who according to the Arabs is the greatest botanist of antiquity, recommended hemp seeds to "quench geniture" and its juice for earaches.fevers

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a temperature above the normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature set point. There is not a single agreed-upon upper limit for normal temperature with sources using val ...

, indigestion

Indigestion, also known as dyspepsia or upset stomach, is a condition of impaired digestion. Symptoms may include upper abdominal fullness, heartburn, nausea, belching, or upper abdominal pain. People may also experience feeling full earlier t ...

, eye, head and tooth aches, pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity ( pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sy ...

, and to induce sleep.opium