Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the first

president of the Russian Federation

The president of the Russian Federation ( rus, Президент Российской Федерации, Prezident Rossiyskoy Federatsii) is the head of state of the Russian Federation. The president leads the executive branch of the federal ...

from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the

Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1961 to 1990. He later stood as a

political independent

An independent or non-partisan politician is a politician not affiliated with any political party or bureaucratic association. There are numerous reasons why someone may stand for office as an independent.

Some politicians have political views th ...

, during which time he was viewed as being ideologically aligned with

liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and

Russian nationalism

Russian nationalism is a form of nationalism that promotes Russian cultural identity and unity. Russian nationalism first rose to prominence in the early 19th century, and from its origin in the Russian Empire, to its repression during early B ...

.

Yeltsin was born in

Butka,

Ural Oblast

The Ural Oblast (russian: Уральская область) was an oblast of the RSFSR within the USSR. It was created November 3, 1923 by the merger of Perm, Yekaterinburg, Chelyabinsk and Tyumen Governorates. The capital of the oblast was Sv ...

. He grew up in

Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering an ...

and

Berezniki

russian: Березники

, image_skyline=Berezniki City Administration.jpg

, image_caption=Berezniki City Administration building

, coordinates =

, map_label_position=top

, image_coa=Coat of Arms of Berezniki (Perm krai) (2018).gif

, coa_capti ...

. After studying at the

Ural State Technical University

Ural State Technical University (USTU) is a public technical university in Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russian Federation. It is the biggest technical institution of higher education in Russia, with close ties to local industry in the Urals. ...

, he worked in construction. After joining the Communist Party, he rose through its ranks, and in 1976 he became First Secretary of the party's

Sverdlovsk Oblast committee. Yeltsin was initially a supporter of the ''

perestroika'' reforms of Soviet leader

Mikhail Gorbachev. He later criticized the reforms as being too moderate, and called for a transition to a

multi-party

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system in which multiple political parties across the political spectrum run for national elections, and all have the capacity to gain control of government offices, separately or in coa ...

representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represe ...

. In 1987 he was the first person to resign from the

Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which established his popularity as an anti-establishment figure. In 1990, he was elected chair of the

Russian Supreme Soviet and in 1991 was

elected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

president of the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

(RSFSR). Yeltsin allied with various non-Russian

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

leaders, and was instrumental in the formal

dissolution of the Soviet Union in December of that year. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the RSFSR became the Russian Federation, an independent state. Through that transition, Yeltsin remained in office as president. He was later reelected in the

1996 election, which was claimed by critics to be pervasively corrupt.

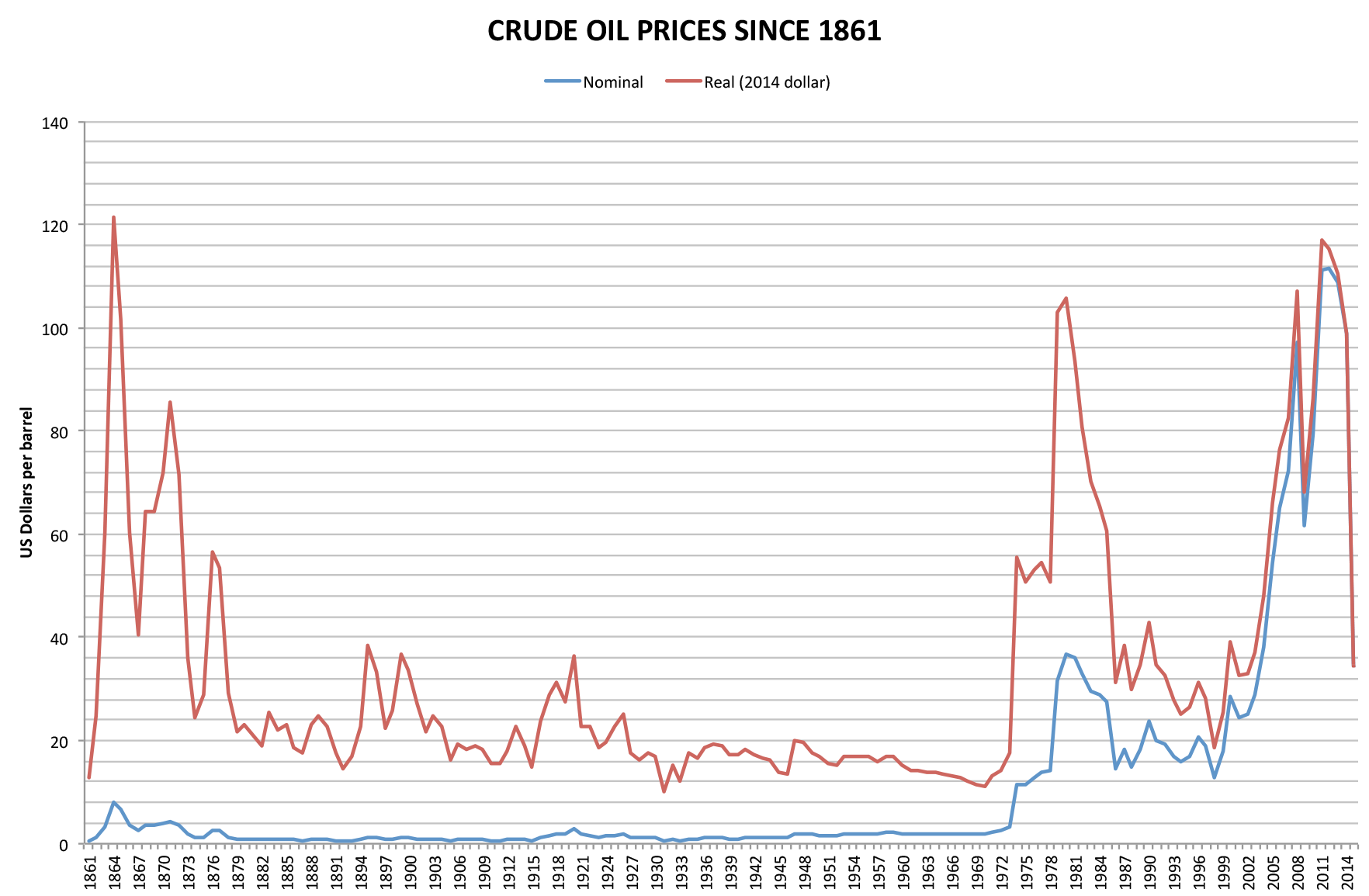

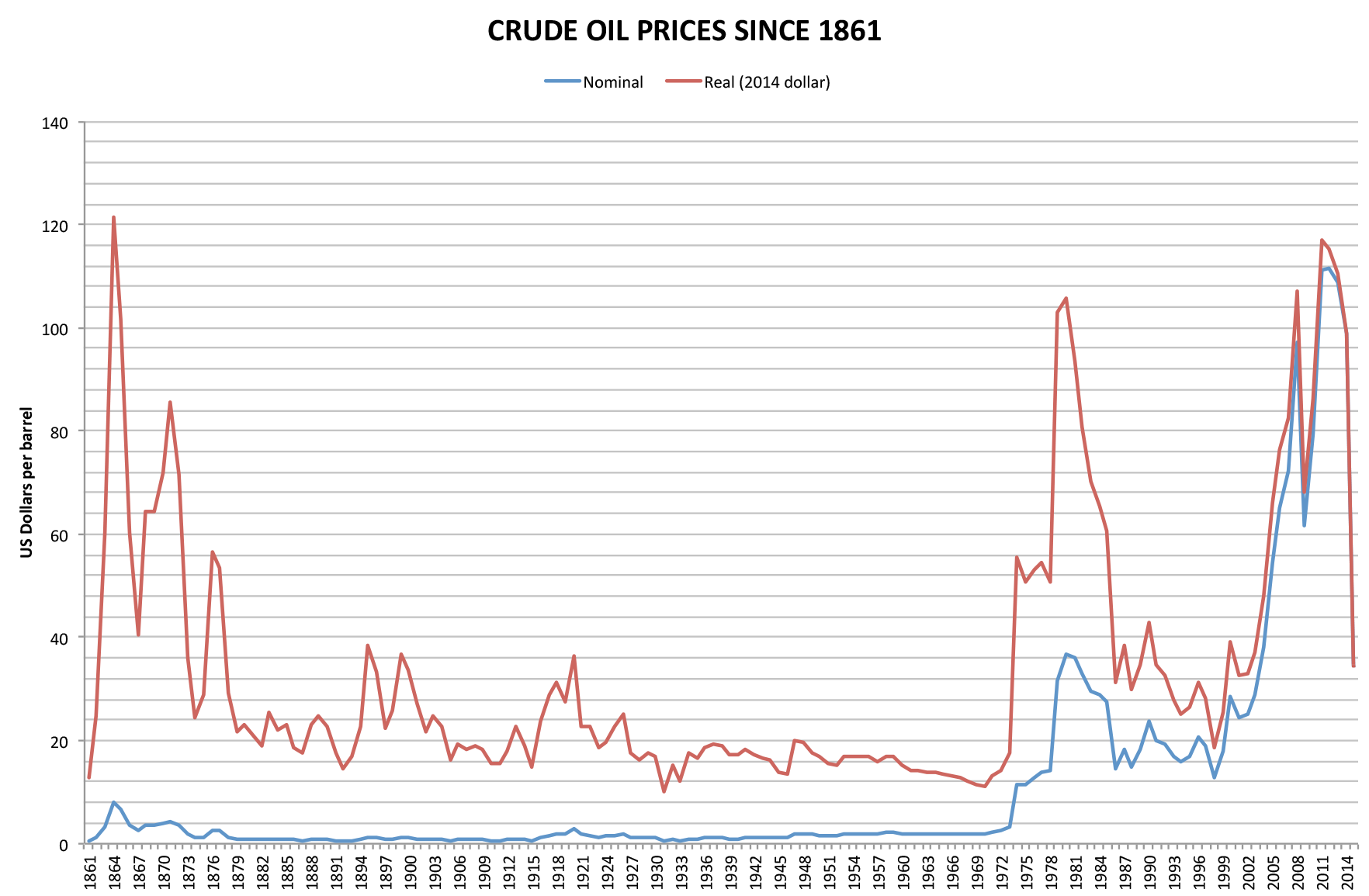

Yeltsin transformed Russia's

command economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, p ...

into a capitalist

market economy by implementing

economic shock therapy

In economics, shock therapy is a group of policies intended to be implemented simultaneously in order to liberalize the economy, including liberalization of all prices, privatization, trade liberalization, and stabilization via tight monetary pol ...

,

market exchange rate of the

ruble

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

,

nationwide privatization, and lifting of

price controls. Economic volatility and inflation ensued. Amid the economic shift, a small number of

oligarchs obtained a majority of the national property and wealth, while international monopolies came to dominate the market.

[Johanna Granville]

"''Dermokratizatsiya'' and ''Prikhvatizatsiya'': The Russian Kleptocracy and Rise of Organized Crime,"

'Demokratizatsiya'' (summer 2003), pp. 448–457. A

constitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variations to this ...

emerged in 1993 after Yeltsin ordered the unconstitutional dissolution of the

Russian parliament

The Federal Assembly ( rus, Федера́льное Собра́ние, r=Federalnoye Sobraniye, p=fʲɪdʲɪˈralʲnəjə sɐˈbranʲɪjə) is the national legislature of the Russian Federation, according to the Constitution of the Russian F ...

, leading parliament to impeach him. The crisis ended after troops loyal to Yeltsin stormed the

parliament building and stopped an armed uprising; he then introduced a

new constitution which significantly expanded the powers of the president. Secessionist sentiment in the

Russian Caucasus led to the

First Chechen War,

War of Dagestan

The Dagestan War (russian: Дагестанская война), also known as the Invasion of Militants in Dagestan (russian: Вторжение боевиков в Дагестан) began when the Chechnya-based Islamic International Peacekeep ...

, and

Second Chechen War

The Second Chechen War (russian: Втора́я чече́нская война́, ) took place in Chechnya and the border regions of the North Caucasus between the Russian Federation and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, from August 1999 ...

between 1994 and 1999. Internationally, Yeltsin promoted renewed collaboration with Europe and signed

arms control agreements with the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. Amid growing internal pressure, he resigned by the end of 1999 and was succeeded by his chosen successor,

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime min ...

, whom he had appointed

prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

a few months earlier. He kept a low profile after leaving office and was accorded a

state funeral upon his death in 2007.

Domestically, he was highly popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s, although his reputation was damaged by the economic and political crises of his presidency, and he left office widely unpopular with the Russian population. He received praise and criticism for his role in dismantling the Soviet Union, transforming Russia into a representative democracy, and introducing new political, economic, and cultural freedoms to the country. Conversely, he was accused of economic mismanagement, overseeing a massive growth in inequality and corruption, and sometimes of undermining Russia's standing as a major world power.

Early life, education and early career

1931–1948: Childhood

Boris Yeltsin was born on 1 February 1931 in the village of Butka,

Talitsky District,

Sverdlovsk Oblast, then in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, one of the republics of the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. His family, who were ethnic

Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

, had lived in this area of the

Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

since at least the eighteenth century. His father, Nikolai Yeltsin, had married his mother, Klavdiya Vasilyevna Starygina, in 1928. Yeltsin always remained closer to his mother than to his father; the latter beat his wife and children on various occasions.

The Soviet Union was then under the dictatorship of

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, who led the

one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system, or single-party system is a type of sovereign state in which only one political party has the right to form the government, usually based on the existing constitution. All other parties ...

governed by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Seeking to convert the country into a

socialist society according to

Marxist–Leninist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialect ...

doctrine, in the late 1920s Stalin's government had initiated a project of

mass rural collectivisation coupled with

dekulakization. As a prosperous farmer, Yeltsin's paternal grandfather, Ignatii, was accused of being a "

kulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

" in 1930. His farm, which was in Basmanovo (also known as Basmanovskoye), was confiscated; and he and his family were forced to reside in a cottage in nearby Butka. There, Nikolai and Ignatii's other children were allowed to join the local

kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz., a contraction of советское хозяйство, soviet ownership or ...

(

collective farm), but Ignatii himself was not; he and his wife, Anna, were exiled in 1934 to

Nadezhdinsk, where he died two years later.

As an infant, Yeltsin was christened in the

Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

; his mother was devout, and his father unobservant. In the years after his birth, the area was hit by the

famine of 1932–1933; throughout his childhood, Yeltsin was often hungry. In 1932, Yeltsin's parents moved to

Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering an ...

, where Yeltsin attended

kindergarten

Kindergarten is a preschool educational approach based on playing, singing, practical activities such as drawing, and social interaction as part of the transition from home to school. Such institutions were originally made in the late 18th ce ...

. There, in 1934, the

OGPU state security services arrested Nikolai, accused him of

anti-Soviet agitation, and sentenced him to three years in the

Dmitrov

Dmitrov ( rus, Дмитров, p=ˈdmʲitrəf) is a town and the administrative center of Dmitrovsky District in Moscow Oblast, Russia, located to the north of Moscow on the Yakhroma River and the Moscow Canal. Population:

History

Dmitrov ...

labor camp. Yeltsin and his mother then were ejected from their residence and were taken in by friends; Klavdiya worked at a garment factory in her husband's absence. In October 1936, Nikolai returned; in July 1937, the couple's second child, Mikhail, was born. That month, they moved to

Berezniki

russian: Березники

, image_skyline=Berezniki City Administration.jpg

, image_caption=Berezniki City Administration building

, coordinates =

, map_label_position=top

, image_coa=Coat of Arms of Berezniki (Perm krai) (2018).gif

, coa_capti ...

, in

Perm Krai

Perm Krai (russian: Пе́рмский край, r=Permsky kray, p=ˈpʲɛrmskʲɪj ˈkraj, ''Permsky krai'', , ''Perem lador'') is a federal subject of Russia (a krai) that came into existence on December 1, 2005 as a result of the 2004 re ...

, where Nikolai got work on a

potash

Potash () includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water-soluble form. combine project. There, in July 1944, they had a third child, the daughter, Valentina.

Between 1939 and 1945, Yeltsin received a primary education at Berezniki's Railway School Number 95. Academically, he did well at primary school and was repeatedly elected class monitor by fellow pupils. There, he also took part in activities organized by the

Komsomol and

Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization

The Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization ( rus, Всесоюзная пионерская организация имени В. И. Ленина, r=Vsesoyuznaya pionerskaya organizatsiya imeni V. I. Lenina, t=The All-Union Pioneer Organi ...

. This overlapped with

Soviet involvement in the Second World War, during which Yeltsin's paternal uncle, Andrian, served in the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

and was killed.

From 1945 to 1949, Yeltsin studied at the municipal secondary school number 1, also known as

Pushkin High School. Yeltsin did well at secondary school, and there took an increasing interest in sport, becoming captain of the school's volleyball squad. He enjoyed playing pranks and in one instance played with a grenade, which blew off the thumb and index finger of his left hand. With friends, he would go on summer walking expeditions in the adjacent

taiga

Taiga (; rus, тайга́, p=tɐjˈɡa; relates to Mongolic and Turkic languages), generally referred to in North America as a boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruc ...

, sometimes for many weeks.

1949–1960: University and career in construction

In September 1949, Yeltsin was admitted to the

Ural Polytechnic Institute

Ural State Technical University (USTU) is a public technical university in Yekaterinburg, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russian Federation. It is the biggest technical institution of higher education in Russia, with close ties to local industry in the Urals. ...

(UPI) in

Sverdlovsk. He took the stream in industrial and civil engineering, which included courses in maths, physics, materials and soil science, and draftsmanship. He was also required to study Marxist-Leninist doctrine and choose a language course, for which he selected

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, although never became adept at it. Tuition was free and he was provided a small stipend to live on, which he supplemented by unloading railway trucks for a small wage. Academically, he achieved high grades, although temporarily dropped out in 1952 when afflicted with

tonsillitis

Tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils in the upper part of the throat. It can be acute or chronic. Acute tonsillitis typically has a rapid onset. Symptoms may include sore throat, fever, enlargement of the tonsils, trouble swallowing, and en ...

and

rheumatic fever. He devoted much time to

athletics

Athletics may refer to:

Sports

* Sport of athletics, a collection of sporting events that involve competitive running, jumping, throwing, and walking

** Track and field, a sub-category of the above sport

* Athletics (physical culture), competi ...

, and joined the UPI volleyball team. He avoided any involvement in political organizations while there. During the summer 1953 break, he traveled across the Soviet Union, touring the

Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchm ...

, central Russia,

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

,

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, and

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

; much of the travel was achieved by hitchhiking on freight trains. It was at UPI that he began a relationship with

Naina Iosifovna Girina, a fellow student who would later become his wife. Yeltsin completed his studies in June 1955.

Leaving the Ural Polytechnic Institute, Yeltsin was assigned to work with the Lower Iset Construction Directorate in Sverdlovsk; at his request, he served the first year as a trainee in various building trades. He quickly rose through the organization's ranks. In June 1956 he was promoted to foreman (''master''), and in June 1957 was promoted again, to the position of work superintendent (''prorab''). In these positions, he confronted a widespread alcoholism and a lack of motivation among construction workers, an irregular supply of materials, and the regular theft or vandalism of materials that were available. He soon imposed fines for those who damaged or stole materials or engaged in absenteeism, and closely monitored productivity. His work on the construction of a textile factory, for which he oversaw 1000 workers, brought him wider recognition. In June 1958 he became a senior work superintendent (''starshii prorab'') and in January 1960 was made head engineer (''glavni inzhener'') of Construction Directorate Number 13.

At the same time, Yeltsin's family was growing; in September 1956, he married Girina. She soon got work at a scientific research institute, where she remained for 29 years. In August 1957, their daughter Yelena was born, followed by a second daughter, Tatyana, in January 1960. During this period, they moved through a succession of apartments. On family holidays, Yeltsin took his family to a lake in northern Russia and to the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

coast.

CPSU career

1960–1975: Early membership of the Communist Party

In March 1960, Yeltsin became a probationary member of the governing Communist Party and a full member in March 1961. In his later autobiography, he stated that his original reasons for joining were "sincere" and rooted in a genuine belief in the party's socialist ideals. In other interviews he instead stated that he joined because membership was a necessity for career advancement. His career continued to progress during the early 1960s; in February 1962 he was promoted chief (''nachal'nik'') of the construction directorate. In June 1963, Yeltsin was reassigned to the Sverdlovsk House-Building Combine as its head engineer, and in December 1965 became the combine's director. During this period he was largely involved in building residential housing, the expansion of which was a major priority for the government. He gained a reputation within the construction industry as a hard worker who was punctual and effective and who was used to meeting the targets set forth by the state apparatus. There had been plans to award him the

Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (russian: Орден Ленина, Orden Lenina, ), named after the leader of the Russian October Revolution, was established by the Central Executive Committee on April 6, 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration ...

for his work, although this was scrapped after a five-story building he was constructing collapsed in March 1966. An official investigation found that Yeltsin was not culpable for the accident.

Within the local Communist Party, Yeltsin gained a patron in , who became the first secretary of the party ''

gorkom'' in 1963. In April 1968, Ryabov decided to recruit Yeltsin into the regional party apparatus, proposing him for a vacancy in the ''

obkom

The organization of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was based on the principles of democratic centralism.

The governing body of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was the Party Congress, which initially met annually but whose ...

'' department for construction. Ryabov ensured that Yeltsin got the job despite objections that he was not a longstanding party member. That year, Yeltsin and his family moved into a four-room apartment on Mamin-Sibiryak Street, downtown Sverdlovsk. Yeltsin then received his second

Order of the Red Banner of Labor

The Order of the Red Banner of Labour (russian: Орден Трудового Красного Знамени, translit=Orden Trudovogo Krasnogo Znameni) was an order of the Soviet Union established to honour great deeds and services to the ...

for his work completing a cold-rolling mill at the Upper Iset Works, a project for which he had overseen the actions of 15,000 laborers. In the late 1960s, Yeltsin was permitted to visit the West for the first time as he was sent on a trip to

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. In 1975, Yeltsin was then made one of the five ''obkom'' secretaries in the Sverdlovsk Oblast, a position that gave him responsibility not only for construction in the region but also for the forest and the pulp-and-paper industries. Also in 1975, his family relocated to a flat in the House of Old Bolsheviks on March Street.

1976–1985: First Secretary of the Sverdlovsk Oblast

In October 1976, Ryabov was promoted to a new position in Moscow. He recommended that Yeltsin replace him as the First Secretary of the Party Committee in Sverdlovsk Oblast.

Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and ...

, who then led the Soviet Union as

General Secretary of the party's

Central Committee, interviewed Yeltsin personally to determine his suitability and agreed with Ryabov's assessment. At the Central Committee's recommendation, the Sverdlovsk obkom then unanimously voted to appoint Yeltsin as its first secretary. This made him one of the youngest provincial first secretaries in the RSFSR, and gave him significant power within the province.

Where possible, Yeltsin tried to improve consumer welfare in the province, arguing that it would make for more productive workers. Under his provincial leadership, work started on various construction and infrastructure projects in the city of Sverdlovsk, including

a subway system, the replacement of its barracks housing, new theaters and a circus, the refurbishment of its 1912 opera house, and youth housing projects to build new homes for young families. In September 1977, Yeltsin carried out orders to demolish the

Ipatiev House

Ipatiev House (russian: Дом Ипатьева) was a merchant's house in Yekaterinburg (later renamed Sverdlovsk in 1924, renamed back to Yekaterinburg in 1991) where the former Emperor Nicholas II of Russia (1868–1918, reigned 1894–1917), h ...

, the location where the

Romanov

The House of Romanov (also transcribed Romanoff; rus, Романовы, Románovy, rɐˈmanəvɨ) was the reigning imperial house of Russia from 1613 to 1917. They achieved prominence after the Tsarina, Anastasia Romanova, was married to ...

royal family

had been killed in 1918, over the government's fears that it was attracting growing foreign and domestic attention. He was also responsible for punishing those living in the province who wrote or published material that the Soviet government considered to be seditious or damaging to the established order.

Yeltsin sat on the civil-military collegium of the

Urals Military District

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

and attended its field exercises. In October 1978, the

Ministry of Defence gave him the rank of

colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

. Also in 1978, Yeltsin was elected without opposition to the

Supreme Soviet. In 1979 Yeltsin and his family moved into a five-room apartment at the Working Youth Embankment in Sverdlovsk. In February 1981, Yeltsin gave a speech to the

25th CPSU Congress and on the final day of the Congress was selected to join the Communist Party Central Committee.

Yeltsin's reports to party meetings reflected the ideological conformity that was expected within the authoritarian state. Yeltsin played along with the

personality cult

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

surrounding Brezhnev, but he was contemptuous of what he saw as the Soviet's leader's vanity and sloth. He later claimed to have quashed plans for a Brezhnev museum in Sverdlovsk. While First Secretary, his world-view began to shift, influenced by his reading; he kept up with a wide range of journals published in the country and also claimed to have read an illegally-printed ''

samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

'' copy of

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repres ...

's ''

The Gulag Archipelago

''The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation'' (russian: Архипелаг ГУЛАГ, ''Arkhipelag GULAG'') is a three-volume non-fiction text written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer and Soviet dissident Aleksandr So ...

''. Many of his concerns about the Soviet system were prosaic rather than ideological, as he believed that the system was losing effectiveness and beginning to decay. He was increasingly faced with the problem of Russia's place within the Soviet Union; unlike other republics in the country, the RSFSR lacked the same levels of autonomy from the central government in Moscow. In the early 1980s, he and Yurii Petrov privately devised a tripartite scheme for reforming the Soviet Union that would involve strengthening the Russian government, but it was never presented publicly.

By 1980, Yeltsin had developed the habit of appearing unannounced in factories, shops, and public transport to get a closer look at the realities of Soviet life. In May 1981, he held a question-and-answer session with college students at the Sverdlovsk Youth Palace, where he was unusually frank in his discussion of the country's problems. In December 1982 he then gave a television broadcast for the region in which he responded to various letters. This personalised approach to interacting with the public brought disapproval from some Communist Party figures, such as First Secretary of

Tyumen Oblast

Tyumen Oblast (russian: Тюме́нская о́бласть, ''Tyumenskaya oblast'') is a federal subject (an oblast) of Russia. It is geographically located in the Western Siberia region of Siberia, and is administratively part of the Urals ...

, Gennadii Bogomyakov, although the Central Committee showed no concern. In 1981, he was awarded the

Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (russian: Орден Ленина, Orden Lenina, ), named after the leader of the Russian October Revolution, was established by the Central Executive Committee on April 6, 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration ...

for his work. The following year, Brezhnev died and was succeeded by

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (– 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the p ...

, who in turn ruled for 15 months before his own death; Yeltsin spoke positively about Andropov. Andropov was succeeded by another short-lived leader,

Konstantin Chernenko

Konstantin Ustinovich Chernenko uk, Костянтин Устинович Черненко, translit=Kostiantyn Ustynovych Chernenko (24 September 1911 – 10 March 1985) was a Soviet politician and the seventh General Secretary of the Commu ...

. After his death, Yeltsin took part in the Central Committee plenum which appointed

Mikhail Gorbachev the new

General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and thus ''de facto''

Soviet leader, in March 1985.

1985: Relocation to Moscow to become Head of Gorkom

Gorbachev was interested in reforming the Soviet Union and, at the urging of

Yegor Ligachyov

Yegor Kuzmich Ligachyov (also transliterated as Ligachev; russian: Егор Кузьмич Лигачёв, link=no; 29 November 1920 – 7 May 2021) was a Soviet and Russian politician who was a high-ranking official in the Communist Party ...

, the organisational secretary of the Central Committee, soon summoned Yeltsin to meet with him as a potential ally in his efforts. Yeltsin had some reservations about Gorbachev as a leader, deeming him controlling and patronising, but committed himself to the latter's project of reform. In April 1985, Gorbachev appointed Yeltsin as the Head of the Construction Department of the Party's Central Committee. Although it entailed moving to the capital city, Yeltsin was unhappy with what he regarded as a demotion. There, he was issued a

nomenklatura flat at 54 Second Tverskaya-Yamskaya Street, where his daughter

Tatyana and her son and husband soon joined him and his wife. Gorbachev soon promoted Yeltsin to secretary of the Central Committee for construction and capital investment, a position within the powerful

CPSU Central Committee Secretariat, a move approved by the Central Committee plenum in July 1985.

[Leon Aron, ''Boris Yeltsin A Revolutionary Life''. Harper Collins, 2000. pg. 739; .]

With Gorbachev's support, in December 1985, Yeltsin was installed as the first secretary of the

Moscow gorkom of the CPSU. He was now responsible for managing the Soviet capital city, which had a population of 8.7 million. In February 1986, Yeltsin became a candidate (non-voting) member of the

Politburo. At that point he formally left the Secretariat to concentrate on his role in

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

. Over the coming year he removed many of the old secretaries of the gorkom, replacing them with younger individuals, particularly with backgrounds in factory management. In August 1986, Yeltsin gave a two-hour report to the party conference in which he talked about Moscow's problems, including issues that had previously not been spoken about publicly. Gorbachev described the speech as a "strong fresh wind" for the party. Yeltsin expressed a similar message at the 22nd Congress of the CPSU in February 1986 and then in a speech at the House of Political Enlightenment in April.

1987: Resignation

On 10 September 1987, after a lecture from hard-liner

Yegor Ligachyov

Yegor Kuzmich Ligachyov (also transliterated as Ligachev; russian: Егор Кузьмич Лигачёв, link=no; 29 November 1920 – 7 May 2021) was a Soviet and Russian politician who was a high-ranking official in the Communist Party ...

at the Politburo for allowing two small unsanctioned demonstrations on Moscow streets, Yeltsin wrote a letter of resignation to Gorbachev who was holidaying on the Black Sea.

[Conor O'Clery, ''Moscow 25 December 1991: The Last Day of the Soviet Union''. pgs 71, 74, 81. Transworld Ireland (2011); .] When Gorbachev received the letter he was stunned – nobody in Soviet history had voluntarily resigned from the ranks of the Politburo. Gorbachev phoned Yeltsin and asked him to reconsider.

On 27 October 1987 at the plenary meeting of the Central Committee of the

CPSU

"Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspaper ...

, Yeltsin, frustrated that Gorbachev had not addressed any of the issues outlined in his resignation letter, asked to speak. He expressed his discontent with the slow pace of reform in society, the servility shown to the general secretary, and opposition to him from Ligachyov making his position untenable, before requesting to resign from the Politburo, adding that the

City Committee would decide whether he should resign from the post of

First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party

The First Secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was the position of highest authority in the city of Moscow roughly equating to that of mayor. The position was created on November 10, 1917, following t ...

.

Aside from the fact that no one had ever quit the Politburo before, no one in the party had addressed a leader of the party in such a manner in front of the Central Committee since

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

in the 1920s.

In his reply, Gorbachev accused Yeltsin of "political immaturity" and "absolute irresponsibility". Nobody in the Central Committee backed Yeltsin.

Within days, news of Yeltsin's actions leaked and rumours of his "secret speech" at the Central Committee spread throughout Moscow. Soon fabricated ''

samizdat

Samizdat (russian: самиздат, lit=self-publishing, links=no) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the document ...

'' versions began to circulate – this was the beginning of Yeltsin's rise as a rebel and growth in popularity as an anti-establishment figure. Gorbachev called a meeting of the Moscow City Party Committee for 11 November 1987 to launch another crushing attack on Yeltsin and confirm his dismissal. On 9 November 1987, Yeltsin apparently tried to kill himself and was rushed to the hospital bleeding profusely from self-inflicted cuts to his chest. Gorbachev ordered the injured Yeltsin from his hospital bed to the Moscow party plenum two days later where he was ritually denounced by the party faithful in what was reminiscent of a

Stalinist show trial before he was fired from the post of

First Secretary of the Moscow Communist Party

The First Secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, was the position of highest authority in the city of Moscow roughly equating to that of mayor. The position was created on November 10, 1917, following t ...

. Yeltsin said he would never forgive Gorbachev for this "immoral and inhuman" treatment.

Yeltsin was demoted to the position of First Deputy Commissioner for the

State Committee for Construction. At the next meeting of the Central Committee on 24 February 1988, Yeltsin was removed from his position as a Candidate member of the Politburo. He was perturbed and humiliated but began plotting his revenge.

[''The Strange Death of the Soviet Empire'', p. 86; ] His opportunity came with Gorbachev's establishment of the

Congress of People's Deputies.

[''The Strange Death of the Soviet Empire'', p. 90; ] Yeltsin recovered, and started intensively criticizing Gorbachev, highlighting the slow pace of reform in the Soviet Union as his major argument.

Yeltsin's criticism of the Politburo and Gorbachev led to a smear campaign against him, in which examples of Yeltsin's awkward behavior were used against him. Speaking at the CPSU conference in 1988, Yegor Ligachyov stated, "

Boris, you are wrong". An article in ''

Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

'' described Yeltsin as drunk at a lecture during his visit to the United States in September 1989, an allegation which appeared to be confirmed by a TV account of his speech; however, popular dissatisfaction with the regime was very strong, and these attempts to smear Yeltsin only added to his popularity. In another incident, Yeltsin fell from a bridge. Commenting on this event, Yeltsin hinted that he was helped to fall by the enemies of

perestroika, but his opponents suggested that he was simply drunk.

On 26 March 1989, Yeltsin

was elected to the

Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union

The Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union (russian: Съезд народных депутатов СССР, ''Sʺezd narodnykh deputatov SSSR'') was the highest body of state authority of the Soviet Union from 1989 to 1991.

Backg ...

as the delegate from Moscow district with a decisive 92% of the vote,

and on 29 May 1989, he was elected by the

Congress of People's Deputies to a seat on the

Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. On 19 July 1989, Yeltsin announced the formation of the radical pro-reform faction in the Congress of People's Deputies, the

Inter-Regional Group of Deputies, and on 29 July 1989 was elected one of the five co-Chairmen of the Inter-Regional Group.

On 16 September 1989, Yeltsin toured a medium-sized grocery store (

Randalls

Randalls operates 32 supermarkets in Texas under the ''Randalls'' and ''Flagship Randalls'' banners. The chain consists of 13 stores located around the Houston area and 15 stores located around the Austin area as of May 2020. Randalls today form ...

) in

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. Leon Aron, quoting a Yeltsin associate, wrote in his 2000 biography, ''Yeltsin, A Revolutionary Life'' (St. Martin's Press): "For a long time, on the plane to Miami, he sat motionless, his head in his hands. 'What have they done to our poor people?' he said after a long silence." He added, "On his return to Moscow, Yeltsin would confess the pain he had felt after the Houston excursion: the 'pain for all of us, for our country so rich, so talented and so exhausted by incessant experiments'." He wrote that Mr. Yeltsin added, "I think we have committed a crime against our people by making their standard of living so incomparably lower than that of the Americans." An aide, Lev Sukhanov, was reported to have said that it was at that moment that "the last vestige of Bolshevism collapsed" inside his boss. In his autobiography, ''Against the Grain: An Autobiography'', written and published in 1990, Yeltsin hinted in a small passage that after his tour, he made plans to open his own line of grocery stores and planned to fill it with government subsidized goods in order to alleviate the country's problems.

President of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

On 4 March 1990, Yeltsin was elected to the

Congress of People's Deputies of Russia

The Congress of People's Deputies of the Russian SFSR (russian: Съезд народных депутатов РСФСР) and since 1991 Congress of People's Deputies of the Russian Federation (russian: Съезд народных депута� ...

representing Sverdlovsk with 72% of the vote. On 29 May 1990, he was elected chairman of the

Supreme Soviet of the

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

(RSFSR), in spite of the fact that Gorbachev personally pleaded with the Russian deputies not to select Yeltsin.

He was supported by both democratic and conservative members of the Supreme Soviet, which sought power in the developing political situation in the country.

A part of this power struggle was the opposition between power structures of the Soviet Union and the RSFSR. In an attempt to gain more power, on 12 June 1990, the Congress of People's Deputies of the RSFSR adopted a declaration of sovereignty. On 12 July 1990, Yeltsin resigned from the CPSU in a dramatic speech before party members at the

28th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The 28th Congress of the CPSU (July 2, 1990 – July 13, 1990) was held in Moscow. It was held a year ahead of the traditional schedule and turned out to be the last Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in the history of t ...

, some of whom responded by shouting "Shame!"

1991: Presidential election

During May 1991

Vaclav Havel invited Yeltsin to

Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and List of cities in the Czech Republic, largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 milli ...

where the latter unambiguously condemned the Soviet intervention in 1968.

On 12 June Yeltsin won 57% of the popular vote in the democratic

presidential elections for the Russian republic, defeating Gorbachev's preferred candidate,

Nikolai Ryzhkov

Nikolai Ivanovich Ryzhkov ( uk, Микола Іванович Рижков; russian: Николай Иванович Рыжков; born 28 September 1929) is a Soviet, and later Russian, politician. He served as the last Chairman of the Coun ...

, who got just 16% of the vote, and four other candidates. In his election campaign, Yeltsin criticized the "dictatorship of the center", but did not suggest the introduction of a market economy. Instead, he said that he would put his head on the railtrack in the event of increased prices. Yeltsin took office on 10 July, and reappointed

Ivan Silayev

Ivan Stepanovich Silayev (russian: Ива́н Степа́нович Сила́ев; born 21 October 1930) is a former Soviet and Russian politician. He served as Prime Minister of the Soviet Union through the offices of chairman of the Commi ...

as

Chairman of the

Council of Ministers

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

of the Russian SFSR. On 18 August 1991, a

coup against Gorbachev was launched by the government members opposed to perestroika. Gorbachev was held in

Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

while Yeltsin raced to the

White House of Russia

The White House ( rus, Белый дом, r=Bely dom, p=ˈbʲɛlɨj ˈdom; officially The House of the Government of the Russian Federation, rus, Дом Правительства Российской Федерации, r=Dom pravitelstva Ross ...

(residence of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR) in Moscow to defy the coup, making a memorable speech from atop the turret of a tank onto which he had climbed. The White House was surrounded by the military, but the troops defected in the face of mass popular demonstrations. By 21 August most of the coup leaders had fled Moscow and Gorbachev was "rescued" from Crimea and then returned to Moscow. Yeltsin was subsequently hailed by his supporters around the world for rallying mass opposition to the coup.

Although restored to his position, Gorbachev had been destroyed politically. Neither union nor Russian power structures heeded his commands as support had swung over to Yeltsin. By September, Gorbachev could no longer influence events outside of Moscow. Taking advantage of the situation, Yeltsin began taking over what remained of the Soviet government, ministry by ministry—including the Kremlin. On 6 November 1991, Yeltsin issued a decree banning all Communist Party activities on Russian soil. In early December 1991,

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

voted for independence from the Soviet Union. A week later, on 8 December, Yeltsin met Ukrainian president

Leonid Kravchuk

Leonid Makarovych Kravchuk ( uk, Леонід Макарович Кравчук; 10 January 1934 – 10 May 2022) was a Ukrainian politician and the first president of Ukraine, serving from 5 December 1991 until 19 July 1994. In 1992, he signed ...

and the leader of

Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

,

Stanislav Shushkevich

Stanislav Stanislavovich Shushkevich ( be, Станісла́ў Станісла́вавіч Шушке́віч, translit=Stanisłáŭ Stanisłávavič Šuškiévič,; russian: Станисла́в Станисла́вович Шушке́вич; ...

, in

Belovezhskaya Pushcha. In the

Belavezha Accords

The Belovezh Accords ( be, Белавежскае пагадненне, link=no, russian: Беловежские соглашения, link=no, uk, Біловезькі угоди, link=no) are accords forming the agreement declaring that the ...

, the three presidents declared that the Soviet Union no longer existed "as a subject of international law and geopolitical reality," and announced the formation of a voluntary

Commonwealth of Independent States

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) is a regional intergovernmental organization in Eurasia. It was formed following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. It covers an area of and has an estimated population of 239,796,010. ...

(CIS) in its place.

According to Gorbachev, Yeltsin kept the plans of the Belovezhskaya meeting in strict secrecy and the main goal of the dissolution of the Soviet Union was to get rid of Gorbachev, who by that time had started to recover his position after the events of August. Gorbachev has also accused Yeltsin of violating the people's will expressed in the referendum in which the majority voted to keep the Soviet Union united. On 12 December, the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR ratified the Belavezha Accords and denounced the 1922

Union Treaty. It also recalled the Russian deputies from the

Council of the Union

The Soviet of the Union (russian: Сове́т Сою́за - ''Sovet Soyuza'') was the lower chamber of the Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, elected on the basis of universal, equal and direct suffrage by secret ballot ...

, leaving that body without a quorum. While this is regarded as the moment that the largest republic of the Soviet Union had seceded, this is not technically the case. Russia appeared to take the line that it was not possible to secede from a country that no longer existed.

On 17 December, in a meeting with Yeltsin, Gorbachev accepted the ''

fait accompli'' and agreed to dissolve the Soviet Union. On 24 December, by mutual agreement of the other CIS states (which by this time included all of the remaining republics except Georgia), the Russian Federation took the Soviet Union's seat in the United Nations. The next day, Gorbachev resigned and handed the functions of his office to Yeltsin. On 26 December, the

Council of the Republics, the upper house of the Supreme Soviet, voted the Soviet Union out of existence, thereby ending the world's oldest, largest and most powerful Communist state.

Economic relations between the former Soviet republics were severely compromised. Millions of ethnic Russians found themselves in the newly formed foreign countries.

Initially, Yeltsin promoted the retention of national borders according to the pre-existing Soviet state borders, although this left ethnic

Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

as a majority in parts of northern

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, eastern Ukraine, and areas of

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

and

Latvia.

President of the Russian Federation

1991–1996: First term

Radical reforms

Just days after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yeltsin resolved to embark on a programme of radical economic reform. Improving on Gorbachev's reforms, which sought to expand democracy in the socialist system, the new regime aimed to completely dismantle socialism and fully implement capitalism, converting the world's largest command economy into a free-market one. During early discussions of this transition, Yeltsin's advisers debated issues of speed and sequencing, with an apparent division between those favoring a rapid approach and those favoring a gradual or slower approach. On January 1, 1992, Yeltsin signed accords with U.S. President

George H. W. Bush, declaring the

Cold War officially over after nearly 47 years. A visit to Moscow from Havel in April 1992 occasioned the written repudiation of the Soviet intervention and the withdrawal of armed forces from Czechoslovakia.

[ Yeltsin laid a wreath during a November 1992 ceremony in Budapest, apologized for the ]1956 Soviet intervention in Hungary

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

and handed over to president Árpád Göncz

Árpád Göncz (; 10 February 1922 – 6 October 2015) was a Hungarian writer, translator, agronomist, and liberal politician who served as President of Hungary from 2 May 1990 to 4 August 2000. Göncz played a role in the Hungarian Revolution ...

documents from the Communist Party and KGB archives related to the intervention.[ A treaty of friendship was signed in May 1992 with ]Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa (; ; born 29 September 1943) is a Polish statesman, dissident, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who served as the President of Poland between 1990 and 1995. After winning the 1990 election, Wałęsa became the first democrati ...

's Poland, and then another one in August 1992 with Zhelyu Zhelev

Zhelyu Mitev Zhelev ( bg, Желю Митев Желев; 3 March 1935 – 30 January 2015) was a Bulgarian politician and former dissident who served as the first non-Communist President of Bulgaria from 1990 to 1997. Zhelev was one of the mos ...

's Bulgaria.[

] On 2 January 1992, Yeltsin, acting as his own

On 2 January 1992, Yeltsin, acting as his own prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

, ordered the liberalisation of foreign trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (see: World economy)

In most countries, such trade represents a significant ...

, price

A price is the (usually not negative) quantity of payment or compensation given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, the price of production has a different name. If the product is a "good" in the ...

s, and currency. At the same time, Yeltsin followed a policy of "macroeconomic stabilisation", a harsh austerity regime designed to control inflation. Under Yeltsin's stabilisation programme, interest rate

An interest rate is the amount of interest due per period, as a proportion of the amount lent, deposited, or borrowed (called the principal sum). The total interest on an amount lent or borrowed depends on the principal sum, the interest rate, ...

s were raised to extremely high levels to tighten money

Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are as ...

and restrict credit

Credit (from Latin verb ''credit'', meaning "one believes") is the trust which allows one party to provide money or resources to another party wherein the second party does not reimburse the first party immediately (thereby generating a debt) ...

. To bring state spending and revenues into balance, Yeltsin raised new taxes heavily, cut back sharply on government subsidies to industry and construction, and made steep cuts to state welfare spending.

In early 1992, prices skyrocketed throughout Russia, and a deep credit crunch shut down many industries and brought about a protracted depression. The reforms devastated the living standards of much of the population, especially the groups dependent on Soviet-era state subsidies and welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

programs.Hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimize their holdings in that currency as t ...

, caused by the Central Bank of Russia

The Central Bank of the Russian Federation (CBR; ), doing business as the Bank of Russia (russian: Банк России}), is the central bank of the Russian Federation. The bank was established on July 13, 1990. The predecessor of the bank can ...

's loose monetary policy, wiped out many people's personal savings, and tens of millions of Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

were plunged into poverty.

Some economists argue that in the 1990s, Russia suffered an economic downturn more severe than the United States or

Some economists argue that in the 1990s, Russia suffered an economic downturn more severe than the United States or Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

had undergone six decades earlier in the Great Depression.vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

, Alexander Rutskoy

Alexander Vladimirovich Rutskoy (russian: Александр Владимирович Руцкой; born 16 September 1947) is a Russian politician and a former Soviet military officer, Major General of Aviation (1991). He served as the only vic ...

denounced the Yeltsin programme as "economic genocide." By 1993, conflict over the reform direction escalated between Yeltsin on the one side, and the opposition to radical economic reform in Russia's parliament on the other.

Confrontation with parliament

Throughout 1992 Yeltsin wrestled with the Supreme Soviet of Russia

The Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR (russian: Верховный Совет РСФСР, ''Verkhovny Sovet RSFSR''), later Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation (russian: Верховный Совет Российской Федерации, ...

and the Congress of People's Deputies for control over government, government policy, government banking and property. In the course of 1992, the speaker of the Russian Supreme Soviet, Ruslan Khasbulatov

Ruslan Imranovich Khasbulatov (russian: link=no, Русла́н Имранович Хасбула́тов, ce, Хасбола́ти Имра́ни кIант Руслан) (born November 22, 1942) is a Russian economist and politician and the ...

, came out in opposition to the reforms, despite claiming to support Yeltsin's overall goals. In December 1992, the 7th Congress of People's Deputies succeeded in turning down the Yeltsin-backed candidacy of Yegor Gaidar

Yegor Timurovich Gaidar (russian: link=no, Его́р Тиму́рович Гайда́р; ; 19 March 1956 – 16 December 2009) was a Soviet and Russian economist, politician, and author, and was the Acting Prime Minister of Russia from 15 Ju ...

for the position of Russian Prime Minister

The chairman of the government of the Russian Federation, also informally known as the prime minister, is the nominal head of government of Russia. Although the post dates back to 1905, its current form was established on 12 December 1993 f ...

. An agreement was brokered by Valery Zorkin

Valery Dmitrievich Zorkin (russian: Вале́рий Дми́триевич Зо́рькин) is the first and the current Chairman of the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation.

Zorkin was born on 18 February 1943 in Konstantinovka, ...

, chairman of the Constitutional Court, which included the following provisions: a national referendum on the new constitution; parliament and Yeltsin would choose a new head of government, to be confirmed by the Supreme Soviet; and the parliament was to cease making constitutional amendments that change the balance of power between the legislative and executive branches. Eventually, on 14 December, Viktor Chernomyrdin

Viktor Stepanovich Chernomyrdin (russian: Ви́ктор Степа́нович Черномы́рдин, ; 9 April 19383 November 2010) was a Soviet and Russian politician and businessman. He was the Minister of Gas Industry of the Soviet Unio ...

, widely seen as a compromise figure, was confirmed in the office.

The conflict escalated soon, however, with the parliament changing its prior decision to hold a referendum. Yeltsin, in turn, announced in a televised address to the nation on 20 March 1993, that he was going to assume certain "special powers" in order to implement his programme of reforms. In response, the hastily called 9th Congress of People's Deputies attempted to remove Yeltsin from presidency through impeachment on 26 March 1993. Yeltsin's opponents gathered more than 600 votes for impeachment, but fell 72 votes short of the required two-thirds majority.Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

. In August, a commentator reflected on the situation as follows: "The President issues decrees as if there were no Supreme Soviet, and the Supreme Soviet suspends decrees as if there were no President." (Izvestia

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in 1917, it was a newspaper of record in the Soviet Union until the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, and describes i ...

, 13 August 1993).

On 21 September 1993, in breach of the constitution, Yeltsin announced in a televised address his decision to disband the Supreme Soviet and Congress of People's Deputies by decree. In his address, Yeltsin declared his intent to rule by decree until the election of the new parliament and a referendum on a new constitution, triggering the constitutional crisis of October 1993. On the night after Yeltsin's televised address, the Supreme Soviet declared Yeltsin removed from the presidency for breaching the constitution, and Vice-President Alexander Rutskoy

Alexander Vladimirovich Rutskoy (russian: Александр Владимирович Руцкой; born 16 September 1947) is a Russian politician and a former Soviet military officer, Major General of Aviation (1991). He served as the only vic ...

was sworn in as acting president.Russian White House

The White House ( rus, Белый дом, r=Bely dom, p=ˈbʲɛlɨj ˈdom; officially The House of the Government of the Russian Federation, rus, Дом Правительства Российской Федерации, r=Dom pravitelstva Ross ...

(parliament building). The attack killed 187 people and wounded almost 500 others.Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

and ultra-nationalists. However, the referendum held at the same time approved the new constitution, which significantly expanded the powers of the president, giving Yeltsin the right to appoint the members of the government, to dismiss the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

and, in some cases, to dissolve the Duma.

The riddle of NATO

The US Department of State seemed to confuse Yeltsin over German re-unification

German reunification (german: link=no, Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a united and fully sovereign state, which took place between 2 May 1989 and 15 March 1991. The day of 3 October 1990 when the Ge ...

and dismemberment of the Helsinki Final Act and ensuing Partnership for Peace

The Partnership for Peace (PfP; french: Partenariat pour la paix) is a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) program aimed at creating trust between the member states of NATO and other states mostly in Europe, including post-Soviet state ...

(PfP) push for NATO expansion

NATO is a military alliance of Member states of NATO, twenty-eight European and two North American countries that constitutes a system of collective defense. The process of joining the alliance is governed by Article 10 of the North Atlantic ...

. There is some question as to the involvement of his Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Kozyrev

Andrei Vladimirovich Kozyrev (russian: Андре́й Влади́мирович Ко́зырев; born 27 March 1951) is a Russian politician who served as the former and the first Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation under Pres ...

, who in August 1993 was painted by Lech Wałęsa

Lech Wałęsa (; ; born 29 September 1943) is a Polish statesman, dissident, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who served as the President of Poland between 1990 and 1995. After winning the 1990 election, Wałęsa became the first democrati ...

(after his failed attempt to hoodwink Yeltsin by one-on-one subterfuge) as a saboteur of Polish aspirations for NATO membership but was regarded by domestic opponents as suborned by Uncle Sam.[ In Yeltsin’s letter to ]Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

dated 15 September 1993 he strongly favours "a pan-European security system" instead of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

and warns:[ By December 1994, the month in which was signed the ]Budapest Memorandum

The Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances comprises three substantially identical political agreements signed at the OSCE conference in Budapest, Hungary, on 5 December 1994, to provide security assurances by its signatories relating to the ...

, Clinton began to understand that Russia had concluded that he was "subordinating, if not abandoning, integration f Russiato NATO expansion." In July 1995 by which time the Russians had signed up to PfP, Yeltsin said to Clinton "we must stick to our position, which is that there should be no rapid expansion of NATO.. it’s important that the OSCE

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) is the world's largest regional security-oriented intergovernmental organization with observer status at the United Nations. Its mandate includes issues such as arms control, prom ...

be the principal mechanism for developing a new security order in Europe. NATO is a factor, too, of course, but NATO should evolve into a politicalonly

Only may refer to:

Music Albums

* ''Only'' (album), by Tommy Emmanuel, 2000

* ''The Only'', an EP by Dua Lipa, 2017

Songs

* "Only" (Anthrax song), 1993

* "Only" (Nine Inch Nails song), 2005

* "Only" (Nicki Minaj song), 2014

* "The Only", by ...

organization."[

]

Chechnya

In December 1994, Yeltsin ordered the military invasion of Chechnya in an attempt to restore Moscow's control over the republic. Nearly two years later, Yeltsin withdrew federal forces from the devastated Chechnya under a 1996 peace agreement brokered by Alexander Lebed, Yeltsin's then-security chief. The peace deal allowed Chechnya greater autonomy but not full independence. The decision to launch the war in Chechnya dismayed many in the West. ''Time'' magazine wrote:

Then, what was to be made of Boris Yeltsin? Clearly he could no longer be regarded as the democratic hero of Western myth. But had he become an old-style communist boss, turning his back on the democratic reformers he once championed and throwing in his lot with militarists and ultranationalists? Or was he a befuddled, out-of-touch chief being manipulated, knowingly or unwittingly, by—well, by whom exactly? If there was to be a dictatorial coup, would Yeltsin be its victim or its leader?

Norwegian rocket incident

In 1995, a Black Brant sounding rocket launched from the Andøya Space Center caused a high alert in Russia, known as the Norwegian rocket incident

The Norwegian rocket incident, also known as the Black Brant scare, occurred on January 25, 1995 when a team of Norwegian and American scientists launched a Black Brant XII four-stage sounding rocket from the Andøya Rocket Range off the northwe ...

. The Russians were alerted that it might be a nuclear missile

Nuclear weapons delivery is the technology and systems used to place a nuclear weapon at the position of detonation, on or near its target. Several methods have been developed to carry out this task.

''Strategic'' nuclear weapons are used primari ...

launched from an American submarine. The incident occurred in the post-Cold War era, where many Russians were still very suspicious of the United States and NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

. A full alert was passed up through the military chain of command all the way to Yeltsin, who was notified and the "nuclear briefcase

A nuclear briefcase is a specially outfitted briefcase used to authorize the use of nuclear weapons and is usually kept near the leader of a nuclear weapons state at all times.

France

In France, the nuclear briefcase does not officially exist. A ...

" (known in Russia as ''Cheget

''Cheget'' (russian: Чегет) is a "nuclear briefcase" (named after in Kabardino-Balkaria) and a part of the automatic system for the command and control of Russia's Strategic Nuclear Forces (SNF) named ''Kazbek'' (, named after Mount Kazbe ...

'') used to authorize nuclear launch was automatically activated. Russian satellites indicated that no massive attack was underway and he agreed with advisors that it was a false alarm.

Privatization and the rise of "the oligarchs"

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yeltsin promoted privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

as a way of spreading ownership of shares in former state enterprises as widely as possible to create political support for his economic reforms. In the West, privatization was viewed as the key to the transition from Communism in Eastern Europe, ensuring a quick dismantling of the Soviet-era command economy to make way for "free market reforms". In the early-1990s, Anatoly Chubais

Anatoly Borisovich Chubais (russian: Анатолий Борисович Чубайс; born 16 June 1955) is a Russian politician and economist who was responsible for privatization in Russia as an influential member of Boris Yeltsin's administ ...

, Yeltsin's deputy for economic policy, emerged as a leading advocate of privatization in Russia.

In late 1992, Yeltsin launched a programme of free vouchers as a way to give mass privatization a jump-start. Under the programme, all Russian citizens were issued vouchers, each with a nominal value of around 10,000 rubles, for the purchase of shares of select state enterprises. Although each citizen initially received a voucher of equal face value, within months the majority of them converged in the hands of intermediaries who were ready to buy them for cash right away.

In 1995, as Yeltsin struggled to finance Russia's growing foreign debt and gain support from the Russian business elite for his bid in the 1996 presidential elections, the Russian president prepared for a new wave of privatization offering stock shares in some of Russia's most valuable state enterprises in exchange for bank loans. The programme was promoted as a way of simultaneously speeding up privatization and ensuring the government a cash infusion to cover its operating needs.'oligarchs

Oligarch may refer to:

Authority

* Oligarch, a member of an oligarchy, a power structure where control resides in a small number of people

* Oligarch (Kingdom of Hungary), late 13th–14th centuries

* Business oligarch, wealthy and influential bu ...

" in the mid-1990s. This was due to the fact that ordinary people sold their vouchers for cash. The vouchers were bought by a small group of investors. By mid-1996, substantial ownership shares over major firms were acquired at very low prices by a handful of people. Boris Berezovsky, who controlled major stakes in several banks and the national media, emerged as one of Yeltsin's most prominent supporters. Along with Berezovsky, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Vladimir Potanin

Vladimir Olegovich Potanin (russian: Владимир Олегович Потанин; born 3 January 1961) is a Russian billionaire businessman. He acquired his wealth notably through the controversial loans-for-shares program in Russia in ...

, Vladimir Bogdanov

Vladimir Leonidovich Bogdanov (russian: Владимир Леонидович Богданов; born 28 May 1951) is a Russian businessman and oil tycoon.

Biography and career

In 1973 he graduated from Tyumen Industrial Institute with a degre ...

, Rem Viakhirev

Rem Ivanovich Viakhirev ( rus, Рем Ива́нович Вя́хирев, p=ˈrɛm ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ ˈvʲæxʲɪrʲɪf; 23 August 1934 – 11 February 2013) was a Russian businessman. From 1992 to 2001, he was chairman of Gazprom. In May 20 ...

, Vagit Alekperov

Vagit Yusufovich Alekperov ( az, Vahid Yusuf oğlu Ələkbərov, russian: Вагит Юсуфович Алекперов; born 1 September 1950) is a Russian– Azerbaijani businessman. He was the President of the oil company Lukoil from 1993 unt ...

, Alexander Smolensky

Alexander Pavlovich Smolensky (russian: Алекса́ндр Па́влович Смолéнский) (born July 6, 1954) is a Russian business oligarch.

Biography

Alexander Smolensky began his business activities on the black market of the s ...

, Viktor Vekselberg

Viktor Felixovich Vekselberg (russian: Виктор Феликсович Вексельберг, uk, Віктор Феліксович Вексельберг; born April 14, 1957) is a Ukrainian-born Russian–Israeli-Cyprus oligarch, billion ...

, Mikhail Fridman