Suprematist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Suprematism (russian: Супремати́зм) is an early twentieth-century art movement focused on the fundamentals of geometry (circles, squares, rectangles), painted in a limited range of colors. The term ''suprematism'' refers to an abstract art based upon "the supremacy of pure artistic feeling" rather than on visual depiction of objects.

Founded by Russian artist

A history of architectural theory

from Vitruvius to the present Edition 4 Publisher Princeton Architectural Press, 2003 , p. 416 The first Suprematist architectural project was created by Lazar Khidekel in 1926. In the mid-1920s to 1932 Lazar Khidekel also created a series of futuristic projects such as Aero-City, Garden-City, and City Over Water. In the 21st century, architect

This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, ideas were in ferment, and the old order was being swept away. As the new order became established, and

This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, ideas were in ferment, and the old order was being swept away. As the new order became established, and

Kazimir Malevich. Suprematism. Manifesto.

Online extracts from Malevich' suprematism art manifesto.

Suprematist Manifesto

{{Authority control Russian artist groups and collectives Russian avant-garde Ukrainian avant-garde Suprematism (art movement)

Kazimir Malevich

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich ; german: Kasimir Malewitsch; pl, Kazimierz Malewicz; russian: Казими́р Севери́нович Мале́вич ; uk, Казимир Северинович Малевич, translit=Kazymyr Severynovych ...

in 1913, Supremus ( Russian: Супремус) conceived of the artist as liberated from everything that pre-determined the ideal structure of life and art. Projecting that vision onto Cubism

Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, and inspired related movements in music, literature and architecture. In Cubist artwork, objects are analyzed, broken up and reassemble ...

, which Malevich admired for its ability to deconstruct art, and in the process change its reference points of art, he led a group of Ukrainian and Russian avant-garde artists — including Aleksandra Ekster

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "pr ...

, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Ivan Kliun, Ivan Puni, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Nina Genke-Meller

Nina Henrichovna Genke or Nina Henrichovna Genke-Meller, or Nina Henrichovna Henke-Meller (russian: Нина Генке-Меллер, Нина Генке; 19 April 1893 – 25 July 1954) was a Ukrainian-Russian avant-garde artist, ( Suprematist ...

, Ksenia Boguslavskaya and others — in what's been described as the first attempt to independently found a Ukrainian avant-garde movement, seceding from the trajectory of prior Russian art history.

To support the movement, Malevich established the journal ''Supremus'' (initially titled ''Nul'' or ''Nothing''), which received contributions from artists and philosophers. The publication, however, never took off and its first issue was never distributed due to the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

. The movement itself, however, was announced in Malevich's 1915 Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0,10, in St. Petersburg, where he, and several others in his group, exhibited 36 works in a similar style. Honour, H. and Fleming, J. (2009) ''A World History of Art''. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, pp. 793–795.

Birth of the movement

Kazimir Malevich developed the concept of Suprematism when he was already an established painter, having exhibited in the ''Donkey's Tail

Donkey's Tail (, Romanized: Osliniy khvost) was a Russian artistic group created from the most radical members of the Jack of Diamonds group. The group included such painters as: Mikhail Larionov (inventor of the name), Natalia Goncharova, Kazi ...

'' and the ''Der Blaue Reiter

''Der Blaue Reiter'' (The Blue Rider) is a designation by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc for their exhibition and publication activities, in which both artists acted as sole editors in the almanac of the same name, first published in mid-May ...

'' (The Blue Rider) exhibitions of 1912 with cubo-futurist

Cubo-Futurism (also called Russian Futurism or Kubo-Futurizm) was an art movement that arose in early 20th century Russian Empire, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism. Cubo- ...

works. The proliferation of new artistic forms in painting, poetry and theatre as well as a revival of interest in the traditional folk art

Folk art covers all forms of visual art made in the context of folk culture. Definitions vary, but generally the objects have practical utility of some kind, rather than being exclusively decorative. The makers of folk art are typically tr ...

of Russia provided a rich environment in which a Modernist

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

culture was born.

In "Suprematism" (Part II of his book ''The Non-Objective World'', which was published 1927 in Munich as Bauhaus

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the Bauhaus (), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 20 ...

Book No. 11), Malevich clearly stated the core concept of Suprematism:

He created a suprematist "grammar" based on fundamental geometric forms; in particular, the square and the circle. In the '' 0.10 Exhibition'' in 1915, Malevich exhibited his early experiments in suprematist painting. The centerpiece of his show was the '' Black Square'', placed in what is called the ''red/beautiful corner'' in Russian Orthodox tradition; the place of the main icon in a house. "Black Square" was painted in 1915 and was presented as a breakthrough in his career and in art in general. Malevich also painted '' White on White'' which was also heralded as a milestone. ''White on White'' marked a shift from polychrome

Polychrome is the "practice of decorating architectural elements, sculpture, etc., in a variety of colors." The term is used to refer to certain styles of architecture, pottery or sculpture in multiple colors.

Ancient Egypt

Colossal statu ...

to monochrome

A monochrome or monochromatic image, object or palette is composed of one color (or values of one color). Images using only shades of grey are called grayscale (typically digital) or black-and-white (typically analog). In physics, monochr ...

Suprematism.

Distinct from Constructivism

Malevich's Suprematism is fundamentally opposed to the postrevolutionary positions of Constructivism and materialism. Constructivism, with its cult of the object, is concerned with utilitarian strategies of adapting art to the principles of functional organization. Under Constructivism, the traditional easel painter is transformed into the artist-as-engineer in charge of organizing life in all of its aspects. Suprematism, in sharp contrast to Constructivism, embodies a profoundly anti-materialist, anti-utilitarian philosophy. In "Suprematism" (Part II of ''The Non-Objective World''), Malevich writes: Jean-Claude Marcadé has observed that "Despite superficial similarities between Constructivism and Suprematism, the two movements are nevertheless antagonists and it is very important to distinguish between them." According to Marcadé, confusion has arisen because several artists—either directly associated with Suprematism such asEl Lissitzky

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (russian: link=no, Ла́зарь Ма́ркович Лиси́цкий, ; – 30 December 1941), better known as El Lissitzky (russian: link=no, Эль Лиси́цкий; yi, על ליסיצקי), was a Russian artist ...

or working under the suprematist influence as did Rodchenko and Lyubov Popova—later abandoned Suprematism for the culture of materials.

Suprematism does not embrace a humanist philosophy which places man at the center of the universe. Rather, Suprematism envisions man—the artist—as both originator and transmitter of what for Malevich is the world's only true reality—that of absolute non-objectivity.

For Malevich, it is upon the foundations of absolute non-objectivity that the future of the universe will be built - a future in which appearances, objects, comfort, and convenience no longer dominate.

Influences on the movement

Malevich also credited the birth of Suprematism to '' Victory Over the Sun'',Kruchenykh

Aleksei Yeliseyevich Kruchyonykh (russian: Алексе́й Елисе́евич Кручёных; 9 February 1886 – 17 June 1968) was a Russian poet, artist, and theorist, perhaps one of the most radical poets of Russian Futurism, a mo ...

's Futurist

Futurists (also known as futurologists, prospectivists, foresight practitioners and horizon scanners) are people whose specialty or interest is futurology or the attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities abo ...

opera production for which he designed the sets and costumes in 1913. The aim of the artists involved was to break with the usual theater of the past and to use a "clear, pure, logical Russian language". Malevich put this to practice by creating costumes from simple materials and thereby took advantage of geometric shapes. Flashing headlights illuminated the figures in such a way that alternating hands, legs or heads disappeared into the darkness. The stage curtain was a black square. One of the drawings for the backcloth shows a black square divided diagonally into a black and a white triangle. Because of the simplicity of these basic forms they were able to signify a new beginning.

Another important influence on Malevich were the ideas of the Russian mystic, philosopher, and disciple of Georges Gurdjieff

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (; rus, Гео́ргий Ива́нович Гурджи́ев, r=Geórgy Ivánovich Gurdzhíev, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj ɪˈvanəvʲɪd͡ʑ ɡʊrd͡ʐˈʐɨ(j)ɪf; hy, Գեորգի Իվանովիչ Գյուրջիև; c. 1 ...

, P. D. Ouspensky

Pyotr Demianovich Ouspenskii (known in English as Peter D. Ouspensky; rus, Пётр Демья́нович Успе́нский, Pyotr Demyánovich Uspénskiy; 5 March 1878 – 2 October 1947) was a Russian esotericist known for his expositions ...

, who wrote of "a fourth dimension or a Fourth Way beyond the three to which our ordinary senses have access".

Some of the titles to paintings in 1915 express the concept of a non-Euclidean geometry

In mathematics, non-Euclidean geometry consists of two geometries based on axioms closely related to those that specify Euclidean geometry. As Euclidean geometry lies at the intersection of metric geometry and affine geometry, non-Euclidean g ...

which imagined forms in movement, or through time; titles such as: ''Two dimensional painted masses in the state of movement''. These give some indications towards an understanding of the ''Suprematic'' compositions produced between 1915 and 1918.

The ''Supremus'' journal

The Supremus group, which in addition to Malevich includedAleksandra Ekster

Alexandra () is the feminine form of the given name Alexander (, ). Etymologically, the name is a compound of the Greek verb (; meaning 'to defend') and (; GEN , ; meaning 'man'). Thus it may be roughly translated as "defender of man" or "pr ...

, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Lyubov Popova, Lazar Khidekel

Lazar Markovich Khidekel (Vitebsk 1904 – Leningrad 1986) was an artist, designer, architect and theoretician, who is noted for realizing the abstract, avant-garde Suprematist movement through architecture.

Early life

In 1918 at the age of 14 ...

, Nikolai Suetin

Nikolai Suetin (; 1897–1954) was a Russian Suprematist artist. He worked as a graphic artist, a designer, and a ceramics painter.

Suetin studied at the Vitebsk Higher Institute of Art, (1918–1922) under Kazimir Malevich, founder of Suprem ...

, Ilya Chashnik

Ilya Grigorevich Chashnik (1902, Lucyn, Russian Empire, currently Ludza, Latvia - 1929, Leningrad) was a suprematist artist, a pupil of Kazimir Malevich and a founding member of the UNOVIS school.

Biography

Chashnik was born to a Jewish family in ...

, Nina Genke-Meller

Nina Henrichovna Genke or Nina Henrichovna Genke-Meller, or Nina Henrichovna Henke-Meller (russian: Нина Генке-Меллер, Нина Генке; 19 April 1893 – 25 July 1954) was a Ukrainian-Russian avant-garde artist, ( Suprematist ...

, Ivan Puni and Ksenia Boguslavskaya, met from 1915 onwards to discuss the philosophy of Suprematism and its development into other areas of intellectual life. The products of these discussions were to be documented in a monthly publication called ''Supremus'', titled to reflect the art movement it championed, that would include painting, music, decorative art, and literature. Malevich conceived of the journal as the contextual foundation in which he could base his art, and originally planned to call the journal ''Nul''. In a letter to a colleague, he explained:

Malevich conceived of the journal as a space for experimentation that would test his theory of nonobjective art. The group of artists wrote several articles for the initial publication, including the essays "The Mouth of the Earth and the Artist" (Malevich), "On the Old and the New in Music" (Matiushin), "Cubism, Futurism, Suprematism" (Rozanova), "Architecture as a Slap in the Face to Ferroconcrete" (Malevich), and "The Declaration of the Word as Such" (Kruchenykh). However, despite a year spent planning and writing articles for the journal, the first issue of ''Supremus'' was never published.

El Lissitzky: Bridge to the West

The most important artist who took the art form and ideas developed by Malevich and popularized them abroad was the painterEl Lissitzky

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (russian: link=no, Ла́зарь Ма́ркович Лиси́цкий, ; – 30 December 1941), better known as El Lissitzky (russian: link=no, Эль Лиси́цкий; yi, על ליסיצקי), was a Russian artist ...

. Lissitzky worked intensively with Suprematism particularly in the years 1919 to 1923. He was deeply impressed by Malevich's Suprematist works as he saw it as the theoretical and visual equivalent of the social upheavals taking place in Russia at the time. Suprematism, with its radicalism, was to him the creative equivalent of an entirely new form of society. Lissitzky transferred Malevich's approach to his '' Proun'' constructions, which he himself described as "the station where one changes from painting to architecture". The Proun designs, however, were also an artistic break from Suprematism; the ''Black Square'' by Malevich was the end point of a rigorous thought process that required new structural design work to follow. Lissitzky saw this new beginning in his Proun constructions, where the term "Proun" (Pro Unovis) symbolized its Suprematist origins.

Lissitzky exhibited in Berlin in 1923 at the Hanover and Dresden showrooms of Non-Objective Art. During this trip to the West, El Lissitzky was in close contact with Theo van Doesburg, forming a bridge between Suprematism and De Stijl and the Bauhaus

The Staatliches Bauhaus (), commonly known as the Bauhaus (), was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts.Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 20 ...

.

Architecture

Lazar Khidekel

Lazar Markovich Khidekel (Vitebsk 1904 – Leningrad 1986) was an artist, designer, architect and theoretician, who is noted for realizing the abstract, avant-garde Suprematist movement through architecture.

Early life

In 1918 at the age of 14 ...

(1904–1986), Suprematist artist and visionary architect, was the only Suprematist architect who emerged from the Malevich circle. Khidekel started his study in architecture in Vitebsk art school under El Lissitzky in 1919–20. He was instrumental in the transition from planar Suprematism to volumetric Suprematism, creating axonometric projections (The Aero-club: Horizontal architecton, 1922–23), making three-dimensional models, such as the architectons, designing objects (model of an "Ashtray", 1922–23), and producing the first Suprematist architectural project (The Workers’ Club, 1926). In the mid-1920s, he began his journey into the realm of visionary architecture

Visionary architecture is a design that only exists on paper or displays idealistic or impractical qualities. The term originated from an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960.Walker, John.Visionary Architecture. ''Glossary of Art, Architect ...

. Directly inspired by Suprematism and its notion of an organic form-creation continuum, he explored new philosophical, scientific and technological futuristic approaches, and proposed innovative solutions for the creation of new urban environments, where people would live in harmony with nature and would be protected from man-made and natural disasters (his still topical proposal for flood protection – the City on the Water, 1925).

Nikolai Suetin

Nikolai Suetin (; 1897–1954) was a Russian Suprematist artist. He worked as a graphic artist, a designer, and a ceramics painter.

Suetin studied at the Vitebsk Higher Institute of Art, (1918–1922) under Kazimir Malevich, founder of Suprem ...

used Suprematist motifs on works at the Imperial Porcelain Factory, Saint Petersburg where Malevich and Chashnik were also employed, and Malevich designed a Suprematist teapot. The Suprematists also made architectural models in the 1920s, which offered a different conception of socialist buildings to those developed in Constructivist architecture

Constructivist architecture was a constructivist style of modern architecture that flourished in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and early 1930s. Abstract and austere, the movement aimed to reflect modern industrial society and urban space, while ...

.

Malevich's architectural projects were known after 1922 ''Arkhitektoniki''. Designs emphasized the right angle

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 degrees or radians corresponding to a quarter turn. If a ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the adjacent angles are equal, then they are right angles. Th ...

, with similarities to De Stijl and Le Corbusier

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (6 October 188727 August 1965), known as Le Corbusier ( , , ), was a Swiss-French architect, designer, painter, urban planner, writer, and one of the pioneers of what is now regarded as modern architecture. He was ...

, and were justified with an ideological connection to communist governance and equality for all. Another part of the formalism

Formalism may refer to:

* Form (disambiguation)

* Formal (disambiguation)

* Legal formalism, legal positivist view that the substantive justice of a law is a question for the legislature rather than the judiciary

* Formalism (linguistics)

* Scien ...

was low regard for triangles which were "dismissed as ancient

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

, pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

, or Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

".Hanno-Walter Kruft, Elsie Callander, Ronald Taylor, and Antony WooA history of architectural theory

from Vitruvius to the present Edition 4 Publisher Princeton Architectural Press, 2003 , p. 416 The first Suprematist architectural project was created by Lazar Khidekel in 1926. In the mid-1920s to 1932 Lazar Khidekel also created a series of futuristic projects such as Aero-City, Garden-City, and City Over Water. In the 21st century, architect

Zaha Hadid

Dame Zaha Mohammad Hadid ( ar, زها حديد ''Zahā Ḥadīd''; 31 October 1950 – 31 March 2016) was an Iraqi-British architect, artist and designer, recognised as a major figure in architecture of the late 20th and early 21st centu ...

had 'a particular interest nthe Russian avant-garde, and the movement known as Constructivism,' and 'as part of their work on the Russian avant-garde, Hadid's unit studied Suprematism, the abstract movement founded by the painter Kazimir Malevich.'.

Social context

This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, ideas were in ferment, and the old order was being swept away. As the new order became established, and

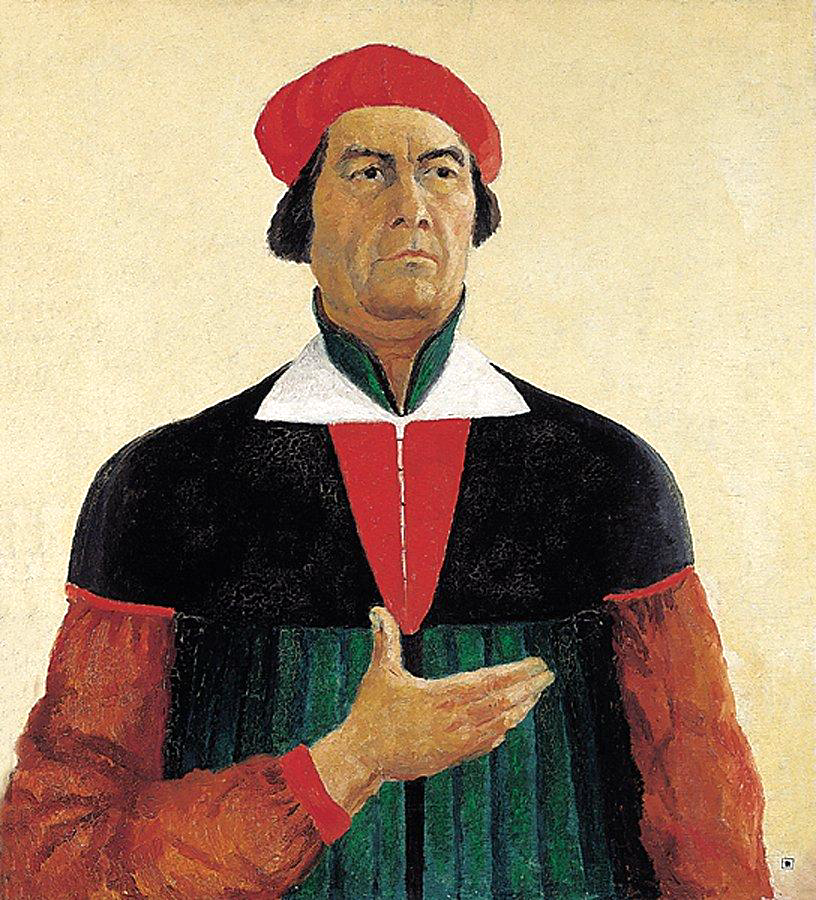

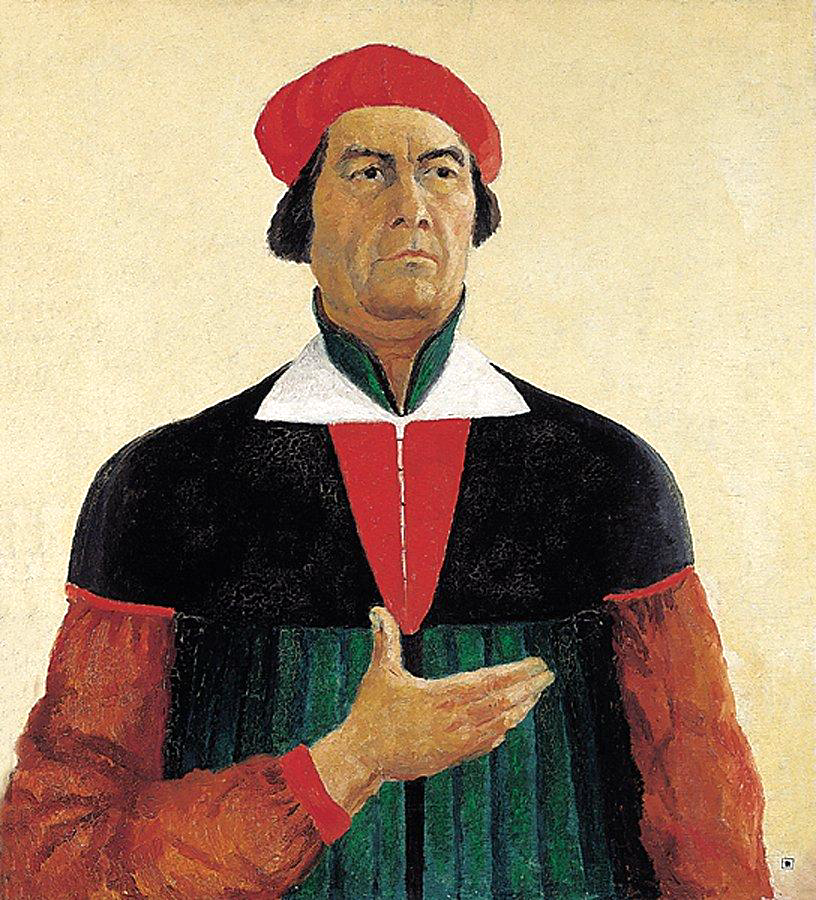

This development in artistic expression came about when Russia was in a revolutionary state, ideas were in ferment, and the old order was being swept away. As the new order became established, and Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the the ...

took hold from 1924 on, the state began limiting the freedom of artists. From the late 1920s the Russian avant-garde

The Russian avant-garde was a large, influential wave of avant-garde modern art that flourished in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, approximately from 1890 to 1930—although some have placed its beginning as early as 1850 and its e ...

experienced direct and harsh criticism from the authorities and in 1934 the doctrine of Socialist Realism

Socialist realism is a style of idealized realistic art that was developed in the Soviet Union and was the official style in that country between 1932 and 1988, as well as in other socialist countries after World War II. Socialist realism is ch ...

became official policy, and prohibited abstraction and divergence of artistic expression. Malevich nevertheless retained his main conception. In his self-portrait

A self-portrait is a representation of an artist that is drawn, painted, photographed, or sculpted by that artist. Although self-portraits have been made since the earliest times, it is not until the Early Renaissance in the mid-15th century tha ...

of 1933 he represented himself in a traditional way—the only way permitted by Stalinist cultural policy—but signed the picture with a tiny black-over-white square.

Notable exhibitions

Historic exhibitions

*''Exhibition of Modern Decorative Art'' at Lemercier Gallery, Moscow, 1915 *'' The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10'' at Galerie Dobychina, Petrograd, 1915 *''First Russian Art Exhibition'' atGalerie Van Diemen Galerie van Diemen was a commercial art gallery founded in 1918 in Berlin (Germany), and which had branches in The Hague, Amsterdam and New York. Under the Nazis, the German branch was Aryanized and its Jewish owners forced into exile and murdered.

...

, Berlin, 1922

*''First State Exhibition of Local and Moscow Artists'', Vitebsk, 1919

*''Exhibition of Paintings by Petrograd Artists of All Trends'', 1918–1923, Petrograd, 1923

Retrospective exhibitions

*''The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932'' at theSolomon R. Guggenheim Museum

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is an art museum at 1071 Fifth Avenue on the corner of East 89th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It is the permanent home of a continuously exp ...

, New York, 1992

*''Malevich’s Circle. Confederates. Students. Followers in Russia 1920s-1950s'' at The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg, 2000

*''Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism'' at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, often referred to as The Guggenheim, is an art museum at 1071 Fifth Avenue on the corner of East 89th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It is the permanent home of a continuously exp ...

, New York, 2003

*''Zaha Hadid and Suprematism'' at Galerie Gmurzynska, Zürich, 2010

*''Lazar Khidekel: Surviving Suprematism'' at Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley CA, 2004-2005

*''Lazar Markovich Khidekel – the Rediscovered Suprematist'' at House Konstruktiv, Zurich, 2010-2011

*''Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde'' at the Stedelijk Museum

The Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (; Municipal Museum Amsterdam), colloquially known as the Stedelijk, is a museum for modern art, contemporary art, and design located in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

, Amsterdam, 2013

*''Malevich: Revolutionary of Russian Art'' at the Tate Modern

Tate Modern is an art gallery located in London. It houses the United Kingdom's national collection of international modern and contemporary art, and forms part of the Tate group together with Tate Britain, Tate Liverpool and Tate St Ives. It ...

, London, 2014

*''Floating Worlds and Future Cities. Genius of Lazar Khidekel, Suprematism and Russian Avant-garde.'' NYC, 2013

Artists associated with Suprematism

*Kazimir Malevich

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich ; german: Kasimir Malewitsch; pl, Kazimierz Malewicz; russian: Казими́р Севери́нович Мале́вич ; uk, Казимир Северинович Малевич, translit=Kazymyr Severynovych ...

*El Lissitzky

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (russian: link=no, Ла́зарь Ма́ркович Лиси́цкий, ; – 30 December 1941), better known as El Lissitzky (russian: link=no, Эль Лиси́цкий; yi, על ליסיצקי), was a Russian artist ...

*Ilya Chashnik

Ilya Grigorevich Chashnik (1902, Lucyn, Russian Empire, currently Ludza, Latvia - 1929, Leningrad) was a suprematist artist, a pupil of Kazimir Malevich and a founding member of the UNOVIS school.

Biography

Chashnik was born to a Jewish family in ...

*Lazar Khidekel

Lazar Markovich Khidekel (Vitebsk 1904 – Leningrad 1986) was an artist, designer, architect and theoretician, who is noted for realizing the abstract, avant-garde Suprematist movement through architecture.

Early life

In 1918 at the age of 14 ...

* Alexandra Exter

* Lyubov Popova

*Sergei Senkin

Sergei Yakovlevich Senkin (1894–1963) was a twentieth-century Russian artist, photographer, and illustrator.

Senkin studied with Kasimir Malevitch during the 1920s in Vkhutemas. He sometimes visited Malevitch in Vitebsk with his friend Gustav ...

References and sources

;References ;Sources * ''Kasimir Malevich, The Non-Objective World''. English translation by Howard Dearstyne from the German translation of 1927 by A. von Riesen from Malevich's original Russian manuscript, Paul Theobald and Company, Chicago, 1959. * Camilla Gray, ''The Russian Experiment in Art'', Thames and Hudson, 1976. * Mel Gooding, ''Abstract Art'', Tate Publishing, 2001. * Jean-Claude Marcadé, "What is Suprematism?", from the exhibition catalogue, ''Kasimir Malewitsch zum 100. Geburtstag'', Galerie Gmurzynska, Cologne, 1978.Further reading

* Jean-Claude Marcadé, "Malevich, Painting and Writing: On the Development of a Suprematist Philosophy", ''Kazimir Malevich: Suprematism'', Guggenheim Museum, April 17, 2012 indle Edition* Jean-Claude Marcadé, "Some Remarks on Suprematism"; and Emmanuel Martineau, "A Philosophy of the 'Suprema' ", from the exhibition catalogue ''Suprematisme'', Galerie Jean Chauvelin, Paris, 1977 * Miroslav Lamac and Juri Padrta, "The Idea of Suprematism", from the exhibition catalogue, ''Kasimir Malewitsch zum 100. Geburtstag'', Galerie Gmurzynska, Cologne, 1978 * Lazar Khidekel and Suprematism. Regina Khidekel, Charlotte Douglas, Magdolena Dabrowsky, Alla Rosenfeld, Tatiand Goriatcheva, Constantin Boym. Prestel Publishing, 2014. * S. O. Khan-Magomedov. Lazar Khidekel (Creators of Russian Classical Avant-garde series), M., 2008 *Alla Efimova

Alla Efimova is an art historian, curator, and consultant based in Berkeley, CA. She grew up in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Efimova was the Director of the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life at the University of California Berkeley (2009–1 ...

. Surviving Suprematism: Lazar Khidekel. Judah L. Magnes Museum, Berkeley CA, 2004.

* S.O. Khan-Magomedov. Pioneers of the Soviet Design. Galart, Moscow, 1995.

* Selim Khan-Magomedov, Regina Khidekel. Lazar Markovich Khidekel. Suprematism and Architecture. Leonard Hutton Galleries, New York, 1995.

* Alexandra Schatskikh. Unovis: Epicenter of a New World. The Great Utopia. The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde 1915–1932.- Solomon Guggenheim Museum, 1992, State Tretiakov Gallery, State Russian Museum, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt.

* Mark Khidekel. Suprematism and Architectural Projects of Lazar Khidekel. ''Architectural Design'' 59, # 7–8, 1989

* Mark Khidekel. ''Suprematism in Architecture''. L’Arca, Italy, # 27, 1989

* Selim O. Chan-Magomedow. Pioniere der sowjetischen Architectur, VEB Verlag der Kunst, Dresden, 1983.

* Larissa A. Zhadova. ''Malevich: Suprematism and Revolution in Russian Art 1910–1930'', Thames and Hudson, London, 1982.

* Larissa A. Zhadowa. Suche und Experiment. Russische und sowjetische Kunst 1910 bis 1930, VEB Verlag der Kunst, Dresden, 1978

External links

* *Kazimir Malevich. Suprematism. Manifesto.

Online extracts from Malevich' suprematism art manifesto.

Suprematist Manifesto

{{Authority control Russian artist groups and collectives Russian avant-garde Ukrainian avant-garde Suprematism (art movement)