The suppression of the Jesuits was the removal of all members of the

Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

from most of the countries of

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

and their colonies beginning in 1759, and the abolishment of the order by the

Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

in 1773. The Jesuits were serially expelled from the

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the ...

(1759),

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

(1764), the

Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and all ...

,

Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

,

Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, music, art, prosciutto (ham), cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 inhabitants, Parma is the second mos ...

, the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

(1767) and

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, and

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

(1782).

This timeline was influenced by political manoeuvrings both in Rome and within each country involved. The papacy reluctantly acceded to the anti-Jesuit demands of various Catholic kingdoms while providing minimal theological justification for the suppressions.

Historians identify multiple factors causing the suppression. The Jesuits, who were not above getting involved in politics, were distrusted for their closeness to the pope and his power in the religious and political affairs of independent nations. In France, it was a combination of many influences, from

Jansenism

Jansenism was an early modern theological movement within Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. It was declared a heresy by th ...

to

free-thought

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and that beliefs should instead be reached by other methods ...

, to the then prevailing impatience with the

Ancien Régime

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for "ancient, old"

** Société des anciens textes français

* the French for "former, senior"

** Virelai ancien

** Ancien Régime

** Ancien Régime in France

''Ancien'' may refer to

* the French word for ...

.

Monarchies

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy), ...

attempting to

centralise and

secularise political power viewed the Jesuits as

supranational, too strongly allied to the papacy, and too autonomous from the monarchs in whose territory they operated.

With his

Papal brief

A papal brief or breve is a formal document emanating from the Pope, in a somewhat simpler and more modern form than a papal bull.

History

The introduction of briefs, which occurred at the beginning of the pontificate of Pope Eugene IV (3 Marc ...

, ''

Dominus ac Redemptor

''Dominus ac Redemptor'' (''Lord and Redeemer'') is the papal brief promulgated on 21 July 1773 by which Pope Clement XIV suppressed the Society of Jesus. The Society was restored in 1814 by Pius VII.

Background

The Jesuits had been expelled ...

'' (21 July 1773),

Pope Clement XIV

Pope Clement XIV ( la, Clemens XIV; it, Clemente XIV; 31 October 1705 – 22 September 1774), born Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 May 1769 to his death in Sep ...

suppressed the Society as a ''

fait accompli''. However, the order did not disappear. It continued underground operations in

China,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

,

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

. In Russia,

Catherine the Great allowed the founding of a new

novitiate. In 1814, a subsequent Pope,

Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

, acted to restore the Society of Jesus to its previous provinces, and the Jesuits began to resume their work in those countries.

Background to suppression

Prior to the eighteenth-century suppression of the Jesuits in many countries, there had been earlier bans, such as in territories of the

Venetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

between 1606 and 1656–1657, begun and ended as part of disputes between the Republic and the papacy, beginning with the

Venetian Interdict The Venetian Interdict of 1606 and 1607 was the expression in terms of canon law, by means of a papal interdict, of a diplomatic quarrel and confrontation between the Papal Curia and the Republic of Venice, taking place in the period from 1605 to 1 ...

.

By the mid-18th century, the Society had acquired a reputation in Europe for political maneuvering and economic success. Monarchs in many European states grew increasingly wary of what they saw as undue interference from a foreign entity. The expulsion of Jesuits from their states had the added benefit of allowing governments to impound the Society's accumulated wealth and possessions. However, historian

Gibson (1966) cautions, "

w far this served as a motive for the expulsion we do not know."

Various states took advantage of different events in order to take action. The series of political struggles between various monarchs, particularly France and Portugal, began with disputes over territory in 1750 and culminated in the suspension of diplomatic relations and the dissolution of the Society by the Pope over most of Europe, and even some executions. The

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire ( pt, Império Português), also known as the Portuguese Overseas (''Ultramar Português'') or the Portuguese Colonial Empire (''Império Colonial Português''), was composed of the overseas colonies, factories, and the ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, the

Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and all ...

,

Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, music, art, prosciutto (ham), cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 inhabitants, Parma is the second mos ...

, and the

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

were involved to a different extent.

The conflicts began with trade disputes, in 1750 in Portugal, in 1755 in France, and in the late 1750s in the Two Sicilies. In 1758 the government of

Joseph I of Portugal

Dom Joseph I ( pt, José Francisco António Inácio Norberto Agostinho, ; 6 June 1714 – 24 February 1777), known as the Reformer (Portuguese: ''o Reformador''), was King of Portugal from 31 July 1750 until his death in 1777. Among other act ...

took advantage of the waning powers of

Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV ( la, Benedictus XIV; it, Benedetto XIV; 31 March 1675 – 3 May 1758), born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 17 August 1740 to his death in May 1758. Pope Be ...

and deported Jesuits from South America after relocating them with their native workers, and then fighting a brief conflict, formally suppressing the order in 1759. In 1762 the Parlement Français (a court, not a legislature) ruled against the Society in a huge bankruptcy case under pressure from a host of groups – from within the Church but also secular notables such as

Madame de Pompadour, the king's mistress. Austria and the Two Sicilies suppressed the order by decree in 1767.

Lead-up to suppression

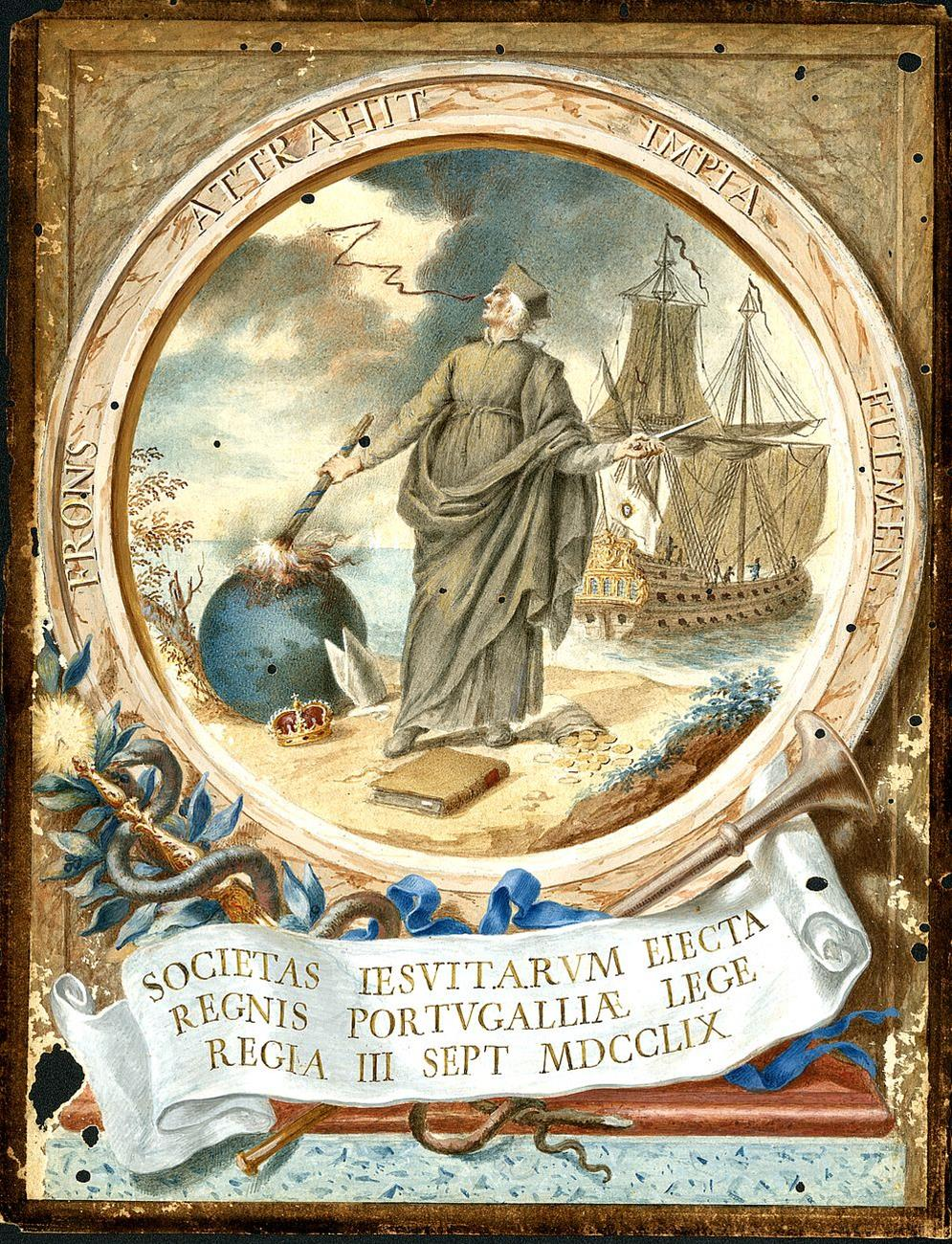

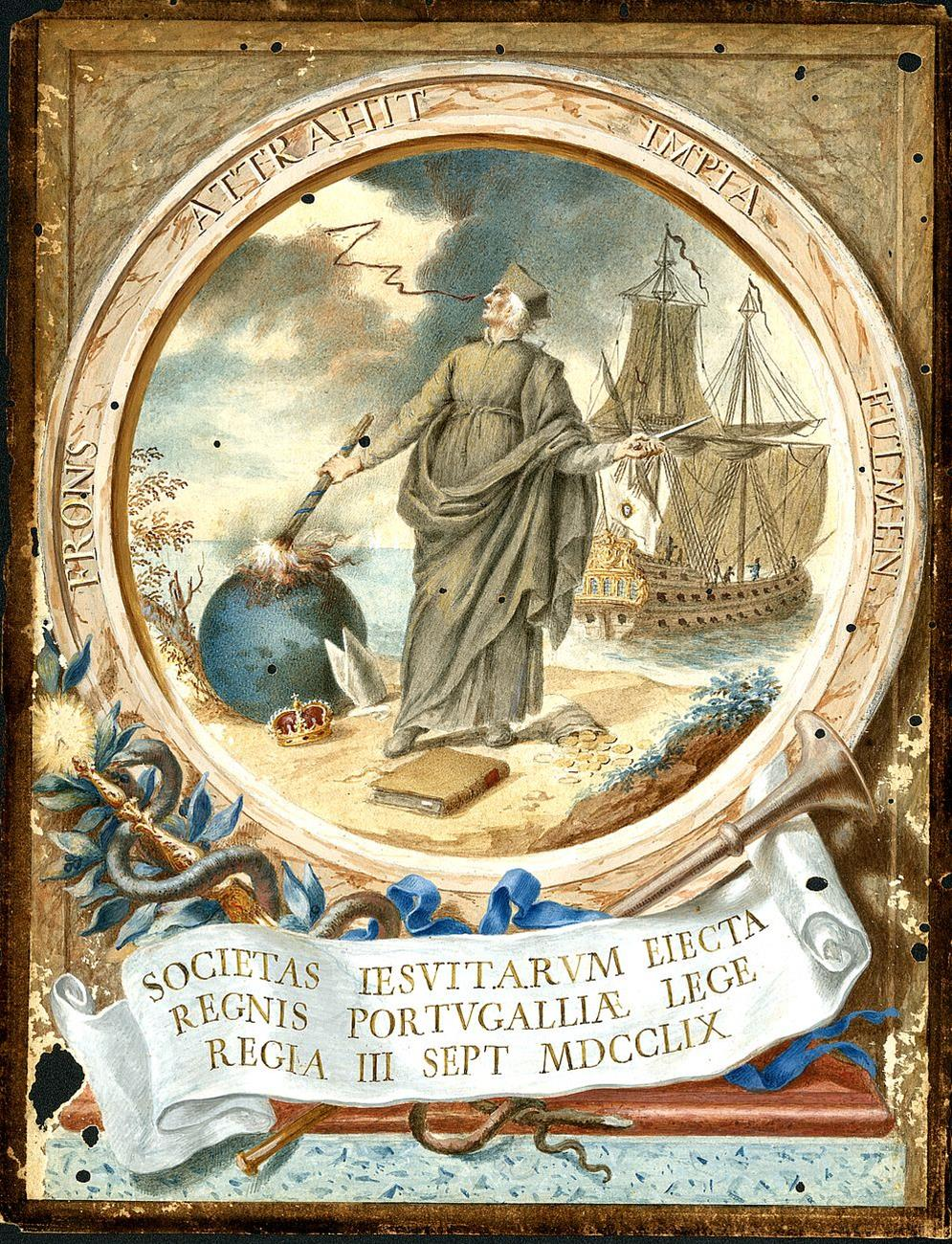

First national suppression: Portugal and its empire in 1759

There were long-standing tensions between the Portuguese crown and the Jesuits, which increased when the

Count of Oeiras (later the Marquis of Pombal) became the monarch's minister of state, culminating in the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1759. The

Távora affair

The Távoras affair was a political scandal of the 18th century Portuguese court. The events triggered by the attempted assassination of King Joseph I of Portugal in 1758 ended with the public execution of the entire Távora family and their cl ...

in 1758 could be considered a pretext for the expulsion and crown confiscation of Jesuit assets. According to historians

James Lockhart and

Stuart B. Schwartz, the Jesuits' "independence, power, wealth, control of education, and ties to Rome made the Jesuits obvious targets for Pombal's brand of extreme regalism."

Portugal's quarrel with the Jesuits began over an exchange of South American colonial territory with Spain. By a secret treaty of 1750, Portugal relinquished to Spain the contested

Colonia del Sacramento

, settlement_type = Capital city

, image_skyline = Basilica del Sanctísimo Sacramento.jpg

, imagesize =

, image_caption = Basílica del Santísimo Sacramento

, pushpin_map = Uruguay

, subdivisio ...

at the mouth of the

Rio de la Plata

Rio or Río is the Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, and Maltese word for "river". When spoken on its own, the word often means Rio de Janeiro, a major city in Brazil.

Rio or Río may also refer to:

Geography Brazil

* Rio de Janeiro

* Rio do Sul, a ...

in exchange for the Seven Reductions of Paraguay, the autonomous Jesuit missions that had been nominal Spanish colonial territory. The native

Guaraní Guarani, Guaraní or Guarany may refer to

Ethnography

* Guaraní people, an indigenous people from South America's interior (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Bolivia)

* Guaraní language, or Paraguayan Guarani, an official language of Paraguay

* ...

, who lived in the mission territories, were ordered to quit their country and settle across the Uruguay. Owing to the harsh conditions, the Guaraní rose in arms against the transfer, and the so-called

Guaraní War

The Guarani War ( es, link=no, Guerra Guaranítica, pt, Guerra Guaranítica) of 1756, also called the War of the Seven Reductions, took place between the Guaraní tribes of seven Jesuit Reductions and joint Spanish- Portuguese forces. It was a ...

ensued. It was a disaster for the Guaraní. In Portugal, a battle escalated, with inflammatory pamphlets denouncing or defending the Jesuits, who, for over a century, had protected the Guarani from enslavement through a network of

Reductions, as depicted in

''The Mission''. The Portuguese colonizers secured the expulsion of the Jesuits.

[Pollen, John Hungerford. "The Suppression of the Jesuits (1750-1773)"]

''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 26 March 2014

On 1 April 1758, Pombal persuaded the aged

Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV ( la, Benedictus XIV; it, Benedetto XIV; 31 March 1675 – 3 May 1758), born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 17 August 1740 to his death in May 1758. Pope Be ...

to appoint the Portuguese

Cardinal Saldanha to investigate allegations against the Jesuits.

[Prestage, Edgar. "Marquis de Pombal"]

''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 26 March 2014 Benedict was skeptical as to the gravity of the alleged abuses. He ordered a "minute inquiry", but, so as to safeguard the reputation of the Society, all serious matters were to be referred back to him. Benedict died the following month on May 3. On May 15, Saldanha, having received the papal brief only a fortnight before, declared that the Jesuits were guilty of having exercised "illicit, public, and scandalous commerce," both in Portugal and in its colonies. He had not visited Jesuit houses as ordered and pronounced on the issues which the pope had reserved to himself.

[

Pombal implicated the Jesuits in the ]Távora affair

The Távoras affair was a political scandal of the 18th century Portuguese court. The events triggered by the attempted assassination of King Joseph I of Portugal in 1758 ended with the public execution of the entire Távora family and their cl ...

, an attempted assassination of the king on 3 September 1758, on the grounds of their friendship with some of the supposed conspirators. On 19 January 1759, he issued a decree sequestering the property of the Society in the Portuguese dominions and the following September deported the Portuguese fathers, about one thousand in number, to the Pontifical States, keeping the foreigners in prison. Among those arrested and executed was the then denounced Gabriel Malagrida, the Jesuit confessor of Leonor of Távora, for "crimes against the faith". After Malagrida's execution in 1759, the Society was suppressed by the Portuguese crown. The Portuguese ambassador was recalled from Rome and the papal nuncio

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international org ...

expelled. Diplomatic relations between Portugal and Rome were broken off until 1770.[

]

Suppression in France in 1764

The suppression of the Jesuits in France began in the French island colony of Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in ...

, where the Society of Jesus had a commercial stake in sugar plantations worked by black slave and free labor. Their large mission plantations included large local populations that worked under the usual conditions of tropical colonial agriculture of the 18th century. The ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' in 1908 said that the practice of the missionaries occupying themselves personally in selling off the goods produced (an anomaly for a religious order) "was allowed partly to provide for the current expenses of the mission, partly in order to protect the simple, childlike natives from the common plague of dishonest intermediaries."

Father Antoine La Vallette, Superior of the Martinique missions, borrowed money to expand the large undeveloped resources of the colony. But on the outbreak of war with England, ships carrying goods of an estimated value of 2,000,000 ''livres'' were captured, and La Vallette suddenly went bankrupt for a very large sum. His creditors turned to the Jesuit procurator in Paris to demand payment, but he refused responsibility for the debts of an independent mission – though he offered to negotiate for a settlement. The creditors went to the courts and received a favorable decision in 1760, obliging the Society to pay and giving leave to distrain in the case of non-payment. The Jesuits, on the advice of their lawyers, appealed to the Parlement of Paris. This turned out to be an imprudent step for their interests. Not only did the Parlement support the lower court on 8 May 1761, but having once gotten the case into its hands, the Jesuits' opponents in that assembly determined to strike a blow at the Order.

The Jesuits had many who opposed them. The Jansenist

Jansenism was an early modern theological movement within Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. It was declared a heresy by th ...

s were numerous among the enemies of the orthodox party. The Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

, an educational rival, joined the Gallicans, the ''Philosophes

The ''philosophes'' () were the intellectuals of the 18th-century Enlightenment.Kishlansky, Mark, ''et al.'' ''A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, volume II: Since 1555.'' (5th ed. 2007). Few were primarily philosophe ...

'', and the Encyclopédistes

The Encyclopédistes () (also known in British English as Encyclopaedists, or in U.S. English as Encyclopedists) were members of the , a French writers' society, who contributed to the development of the ''Encyclopédie'' from June 1751 to Decembe ...

. Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached ...

was weak; his wife and children were in favor of the Jesuits; his able first minister, the Duc de Choiseul, played into the hands of the Parlement and the royal mistress, Madame de Pompadour, to whom the Jesuits had refused absolution for she was living in sin with the King of France, was a determined opponent. The determination of the Parlement of Paris in time bore down all opposition.

The attack on the Jesuits was opened on 17 April 1762 by the Jansenist sympathizer the Abbé Chauvelin, who denounced the Constitution of the Society of Jesus, which was publicly examined and discussed in a hostile press. The Parlement issued its ''Extraits des assertions'' assembled from passages from Jesuit theologians and canonists, in which they were alleged to teach every sort of immorality and error. On 6 August 1762, the final ''arrêt'' was proposed to the Parlement by the Advocate General Joly de Fleury, condemning the Society to extinction, but the king's intervention brought eight months' delay, and in the meantime a compromise was suggested by the Court. If the French Jesuits would separate from the Society headed by the Jesuit General directly under the pope's authority and come under a French vicar, with French customs, as with the Gallican Church, the Crown would still protect them. The French Jesuits, rejecting Gallicanism

Gallicanism is the belief that popular civil authority—often represented by the monarch's or the state's authority—over the Catholic Church is comparable to that of the Pope. Gallicanism is a rejection of ultramontanism; it has so ...

, refused to consent. On 1 April 1763, the colleges were closed, and by a further ''arrêt'' of March 9, 1764, the Jesuits were required to renounce their vows under pain of banishment. At the end of November 1764, the king signed an edict dissolving the Society throughout his dominions, for they were still protected by some provincial parlements, as in Franche-Comté, Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

, and Artois

Artois ( ; ; nl, Artesië; English adjective: ''Artesian'') is a region of northern France. Its territory covers an area of about 4,000 km2 and it has a population of about one million. Its principal cities are Arras (Dutch: ''Atrecht'') ...

. In the draft of the edict, he canceled numerous clauses that implied that the Society was guilty, and writing to Choiseul he concluded: "If I adopt the advice of others for the peace of my realm, you must make the changes I propose, or I will do nothing. I say no more, lest I should say too much."

Decline of the Jesuits in New France

Following the British 1759 victory against the French in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, France lost its North American territory of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

, where Jesuit missionaries in the seventeenth century had been active among indigenous peoples. British rule had implications for Jesuits in New France, but their numbers and sites were already in decline. As early as 1700, the Jesuits had adopted a policy of merely maintaining their existing posts, instead of trying to establish new ones beyond Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple ...

, and Ottawa. Once New France was under British control, the British barred the immigration of any further Jesuits. By 1763, there were only twenty-one Jesuits still stationed in what was now the British colony of Quebec. By 1773, only eleven Jesuits remained. In the same year, the British crown laid claim to Jesuit property in Canada and declared that the Society of Jesus in New France was dissolved.

Spanish Empire suppression of 1767

Events leading to the Spanish suppression

The Suppression in Spain and in the Spanish colonies, and in its dependency the Kingdom of Naples, was the last of the expulsions, with Portugal (1759) and France (1764) having already set the pattern. The Spanish crown had already begun a series of administrative and other changes in their overseas empire, such as reorganizing the viceroyalties, rethinking economic policies, and establishing a military, so that the expulsion of the Jesuits is seen as part of this general trend known generally as the

The Suppression in Spain and in the Spanish colonies, and in its dependency the Kingdom of Naples, was the last of the expulsions, with Portugal (1759) and France (1764) having already set the pattern. The Spanish crown had already begun a series of administrative and other changes in their overseas empire, such as reorganizing the viceroyalties, rethinking economic policies, and establishing a military, so that the expulsion of the Jesuits is seen as part of this general trend known generally as the Bourbon Reforms

The Bourbon Reforms ( es, Reformas Borbónicas) consisted of political and economic changes promulgated by the Spanish Monarchy, Spanish Crown under various kings of the House of Bourbon, since 1700, mainly in the 18th century. The beginning of ...

. The aim of the reforms was to curb the increasing autonomy and self-confidence of American-born Spaniards, reassert crown control, and increase revenues. Some historians doubt that the Jesuits were guilty of intrigues against the Spanish crown that were used as the immediate cause for the expulsion.

Contemporaries in Spain attributed the suppression of the Jesuits to the Esquilache Riots, named after the Italian advisor to Bourbon king Carlos III, that erupted after a sumptuary law was enacted. The law, placing restrictions on men's wearing of voluminous capes and limiting the breadth of sombreros the men could wear, was seen as an "insult to Castilian pride."

When an angry crowd of those resisters converged on the royal palace, king Carlos fled to the countryside. The crowd had shouted "Long Live Spain! Death to Esquilache!" His Flemish palace guard fired warning shots over the people's heads. An account says that a group of Jesuit priests appeared on the scene, soothed the protesters with speeches, and sent them home. Carlos decided to rescind the tax hike and hat-trimming edict and to fire his finance minister.

The monarch and his advisers were alarmed by the uprising, which challenged royal authority, and the Jesuits were accused of inciting the mob and publicly accusing the monarch of religious crimes.

When an angry crowd of those resisters converged on the royal palace, king Carlos fled to the countryside. The crowd had shouted "Long Live Spain! Death to Esquilache!" His Flemish palace guard fired warning shots over the people's heads. An account says that a group of Jesuit priests appeared on the scene, soothed the protesters with speeches, and sent them home. Carlos decided to rescind the tax hike and hat-trimming edict and to fire his finance minister.

The monarch and his advisers were alarmed by the uprising, which challenged royal authority, and the Jesuits were accused of inciting the mob and publicly accusing the monarch of religious crimes. Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for ''Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

, attorney for the Council of Castile, the body overseeing central Spain, articulated this view in a report the king read.[ D.A. Brading, ''The First America'', p. 499.] Charles III ordered the convening of a special royal commission to draw up a master plan to expel the Jesuits. The commission first met in January 1767. It modeled its plan on the tactics deployed by France's Philip IV against the Knights Templar in 1307 – emphasizing the element of surprise. Charles's adviser Campomanes had written a treatise on the Templars in 1747, which may have informed the implementation of the Jesuit suppression. One historian states that "Charles III never would have dared to expel the Jesuits had he not been assured of the support of an influential party within the Spanish Church."Jansenist

Jansenism was an early modern theological movement within Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. It was declared a heresy by th ...

s and mendicant orders had long opposed the Jesuits and sought to curtail their power.

Secret plan of expulsion

King Charles's ministers kept their deliberations to themselves, as did the king, who acted upon "urgent, just, and necessary reasons, which I reserve in my royal mind." The correspondence of

King Charles's ministers kept their deliberations to themselves, as did the king, who acted upon "urgent, just, and necessary reasons, which I reserve in my royal mind." The correspondence of Bernardo Tanucci

Bernardo Tanucci (20 February 1698 – 29 April 1783) was an Italian statesman, who brought an enlightened absolutism style of government to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies for Charles III and his son Ferdinand IV.

Biography

Born of a poor fami ...

, Charles's anti-clerical minister in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, contains the ideas which, from time to time, guided Spanish policy. Charles conducted his government through the Count of Aranda, a reader of Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity—es ...

, and other liberals.Pope Clement XIII

Pope Clement XIII ( la, Clemens XIII; it, Clemente XIII; 7 March 1693 – 2 February 1769), born Carlo della Torre di Rezzonico, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 July 1758 to his death in February 1769. ...

, presented with a similar ultimatum by the Spanish ambassador to the Vatican a few days before the decree would take effect, asked King Charles "by what authority?" and threatened him with eternal damnation. Pope Clement had no means to enforce his protest and the expulsion took place as planned.

Jesuits expelled from Mexico (New Spain)

In New Spain, the Jesuits had actively evangelized the Indians on the northern frontier. But their main activity involved educating elite ''criollo'' (American-born Spanish) men, many of whom themselves became Jesuits. Of the 678 Jesuits expelled from Mexico, 75% were Mexican-born. In late June 1767, Spanish soldiers removed the Jesuits from their 16 missions and 32 stations in Mexico. No Jesuit, no matter how old or ill, could be excepted from the king's decree. Many died on the trek along the cactus-studded trail to the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, where ships awaited them to transport them to Italian exile.

There were protests in Mexico at the exile of so many Jesuit members of elite families. But the Jesuits themselves obeyed the order. Since the Jesuits had owned extensive landed estates in Mexico – which supported both their evangelization of indigenous peoples and their education mission to criollo elites – the properties became a source of wealth for the crown. The crown auctioned them off, benefiting the treasury, and their criollo purchasers gained productive well-run properties.Francisco Javier Clavijero

Francisco Javier Clavijero Echegaray (sometimes ''Francesco Saverio Clavigero'') (September 9, 1731 – April 2, 1787), was a Mexican Jesuit teacher, scholar and historian. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spanish provinces (1767), he ...

, during his Italian exile wrote an important history of Mexico, with emphasis on the indigenous peoples. Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

, the famous German scientist who spent a year in Mexico in 1803–04, praised Clavijero's work on the history of Mexico's indigenous peoples.

Due to the isolation of the Spanish missions on the Baja California peninsula, the expulsion decree did not arrive in Baja California in June 1767, as in the rest of New Spain. It got delayed until the new governor,

Due to the isolation of the Spanish missions on the Baja California peninsula, the expulsion decree did not arrive in Baja California in June 1767, as in the rest of New Spain. It got delayed until the new governor, Gaspar de Portolá

Gaspar de Portolá y Rovira (January 1, 1716 – October 10, 1786) was a Spanish military officer, best known for leading the Portolá expedition into California and for serving as the first Governor of the Californias. His expedition laid the ...

, arrived with the news and decree on November 30. By 3 February 1768, Portolá's soldiers had removed the peninsula's 16 Jesuit missionaries from their posts and gathered them in Loreto, whence they sailed to the Mexican mainland and thence to Europe. Showing sympathy for the Jesuits, Portolá treated them kindly, even as he put an end to their 70 years of mission-building in Baja California. The Jesuit missions in Baja California were turned over to the Franciscans and subsequently to the Dominicans, and the future missions in Alta California were founded by Franciscans.

The change in the Spanish colonies in the New World was particularly great, as the far-flung settlements were often dominated by missions. Almost overnight, in the mission towns of Sonora and Arizona, the "black robes" (Jesuits) disappeared and the "gray robes" (Franciscan

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

s) replaced them.

Expulsion from the Philippines

The royal decree expelling the Society of Jesus from Spain and its dominions reached Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

on 17 May 1768. Between 1769 and 1771, the Jesuits were transported from the Spanish East Indies

The Spanish East Indies ( es , Indias orientales españolas ; fil, Silangang Indiyas ng Espanya) were the overseas territories of the Spanish Empire in Asia and Oceania from 1565 to 1898, governed for the Spanish Crown from Mexico City and Madri ...

to Spain and from there deported to Italy.

Exile of Spanish Jesuits to Italy

Spanish soldiers rounded up the Jesuits in Mexico, marched them to the coasts, and placed them below the decks of Spanish warships headed for the Italian port of Civitavecchia

Civitavecchia (; meaning "ancient town") is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Rome in the central Italian region of Lazio. A sea port on the Tyrrhenian Sea, it is located west-north-west of Rome. The harbour is formed by two pier ...

in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

. When they arrived, Pope Clement XIII

Pope Clement XIII ( la, Clemens XIII; it, Clemente XIII; 7 March 1693 – 2 February 1769), born Carlo della Torre di Rezzonico, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 July 1758 to his death in February 1769. ...

refused to allow the ships to unload their prisoners onto papal territory. Fired upon by batteries of artillery from the shore of Civitavecchia, the Spanish warships had to look for an anchorage off the island of Corsica, then a dependency of Genoa. But since a rebellion had erupted on Corsica, it took five months before some of the Jesuits could set foot on land.Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, king Carlos' minister Bernardo Tanucci

Bernardo Tanucci (20 February 1698 – 29 April 1783) was an Italian statesman, who brought an enlightened absolutism style of government to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies for Charles III and his son Ferdinand IV.

Biography

Born of a poor fami ...

pursued a similar policy: On November 3, the Jesuits, with no accusation or trial, were marched across the border into the Papal States and threatened with death if they returned.[

Historian ]Charles Gibson

Charles deWolf Gibson (born March 9, 1943) is an American broadcast television anchor, journalist and podcaster. Gibson was a host of ''Good Morning America'' from 1987 to 1998 and again from 1999 to 2006, and the anchor of ''World News with Char ...

calls the Spanish crown's expulsion of the Jesuits a "sudden and devastating move" to assert royal control.[Charles Gibson, ''Spain in America'', New York: Harper and Row, p.83-84.] However, the Jesuits became a vulnerable target for the crown's moves to assert more control over the church; also some religious and diocesan clergy and civil authorities were hostile to them, and they did not protest their expulsion.

In addition to 1767, the Jesuits were suppressed and banned twice more in Spain, in 1834 and in 1932. Spanish ruler Francisco Franco rescinded the last suppression in 1938.

Economic impact in the Spanish Empire

The suppression of the order had longstanding economic effects in the Americas, particularly those areas where they had their missions or reductions – outlying areas dominated by indigenous peoples such as Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

and Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

. In Misiones

Misiones (, ''Missions'') is one of the 23 provinces of Argentina, located in the northeastern corner of the country in the Mesopotamia region. It is surrounded by Paraguay to the northwest, Brazil to the north, east and south, and Corrientes P ...

, in modern-day Argentina, their suppression led to the scattering and enslavement of indigenous Guaranís living in the reductions and a long-term decline in the yerba mate industry, from which it only recovered in the 20th century.Valparaíso Region

The Valparaíso Region ( es, Región de Valparaíso, links=no, ) is one of Chile's 16 first order administrative divisions.Valparaíso Region, 2006 With the country's second-highest population of 1,790,219 , and fourth-smallest area of , ...

, Chile, folklore says Jesuits left behind a large entierro following their suppression.pisco

Pisco is a colorless or yellowish-to-amber colored brandy produced in winemaking regions of Peru and Chile. Made by distilling fermented grape juice into a high-proof spirit, it was developed by 16th-century Spanish settlers as an alternative ...

.

Suppression in Malta

Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

was at the time a vassal of the Kingdom of Sicily, and Grandmaster Manuel Pinto da Fonseca

Manuel Pinto da Fonseca (also ''Emmanuel Pinto de Fonseca''; 24 May 1681 – 23 January 1773) was a Portuguese nobleman, the 68th Grand Master of the Order of Saint John, from 1741 until his death.

He undertook many building projects, introduc ...

, himself a Portuguese, followed suit, expelling the Jesuits from the island and seizing their assets. These assets were used in establishing the University of Malta

The University of Malta (, UM, formerly UOM) is a higher education institution in Malta. It offers undergraduate bachelor's degrees, postgraduate master's degrees and postgraduate doctorates. It is a member of the European University Association ...

by a decree signed by Pinto on 22 November 1769, with lasting effect on the social and cultural life of Malta. The Church of the Jesuits (in Maltese ), one of the oldest churches in Valletta

Valletta (, mt, il-Belt Valletta, ) is an administrative unit and capital of Malta. Located on the main island, between Marsamxett Harbour to the west and the Grand Harbour to the east, its population within administrative limits in 2014 wa ...

, retains this name up to the present.

Expulsion from the Duchy of Parma

The independent Duchy of Parma was the smallest Bourbon court. So aggressive in its anti-clericalism was the Parmesan reaction to the news of the expulsion of the Jesuits from Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, that Pope Clement XIII

Pope Clement XIII ( la, Clemens XIII; it, Clemente XIII; 7 March 1693 – 2 February 1769), born Carlo della Torre di Rezzonico, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 July 1758 to his death in February 1769. ...

addressed a public warning against it on 30 January 1768, threatening the Duchy with ecclesiastical censures. At this, all the Bourbon courts turned against the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

, demanding the entire dissolution of the Jesuits. Parma expelled the Jesuits from its territories, confiscating their possessions.[Vogel, Christine]

''The Suppression of the Society of Jesus, 1758–1773''

European History Online

European History Online (''Europäische Geschichte Online, EGO'') is an academic website that publishes articles on the history of Europe between the period of 1450 and 1950 according to the principle of open access.

Organisation

EGO is issued ...

, Mainz: Institute of European History The Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG) in Mainz, Germany, is an independent, public research institute that carries out and promotes historical research on the foundations of Europe in the early and late Modern period. Though autonomous i ...

, 2011, retrieved: November 11, 2011.

Dissolution in Poland and Lithuania

The Jesuit order was disbanded in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi- confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Poland and Lithuania ru ...

in 1773. However, in the territories occupied by the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

in the First Partition of Poland the Society was not disbanded, as Russian Empress Catherine dismissed the Papal order.Commission of National Education

The Commission of National Education ( pl, Komisja Edukacji Narodowej, KEN; lt, Edukacinė komisija) was the central educational authority in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, created by the Sejm and King Stanisław II August on October 1 ...

, the world's first Ministry of Education. Lithuania complied with the suppression.

Papal suppression of 1773

After the suppression of the Jesuits in many European countries and their overseas empires, Pope Clement XIV

Pope Clement XIV ( la, Clemens XIV; it, Clemente XIV; 31 October 1705 – 22 September 1774), born Giovanni Vincenzo Antonio Ganganelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 May 1769 to his death in Sep ...

issued a papal brief on 21 July 1773, in Rome titled: ''Dominus ac Redemptor Noster''. That decree included the following statement.

Resistance in Belgium

After papal suppression in 1773, the scholarly Jesuit Society of Bollandists moved from Antwerp to Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, where they continued their work in the monastery of the Coudenberg

The Palace of Coudenberg (french: Palais du Coudenberg, nl, Coudenbergpaleis) was a royal residence situated on the Coudenberg or Koudenberg (; Dutch for "Cold Hill"), a small hill in what is today the Royal Quarter of Brussels, Belgium.

F ...

; in 1788, the Bollandist Society was suppressed by the Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n government of the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

.

Continued Jesuit work in Prussia

Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the S ...

of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

refused to allow the papal document of suppression to be distributed in his country. The order continued in Prussia for several years after the suppression, although it had dissolved before the 1814 restoration.

Continued work in North America

Many individual Jesuits continued their work as Jesuits in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, although the last one died in 1800. The 21 Jesuits living in North America signed a document offering their submission to Rome in 1774. In the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, schools and colleges continued to be run and founded by Jesuits.

Russian resistance to suppression

In Imperial Russia, Catherine the Great refused to allow the papal document of suppression to be distributed and even openly defended the Jesuits from dissolution, and the Jesuit chapter in Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

received her patronage. It ordained priests, operated schools, and opened housing for novitiates and tertianship Tertianship is the final period of formation for members of the Society of Jesus. Upon invitation of the Provincial, it usually begins three to five years after completion of graduate studies. It is a time when the candidate for final vows steps ba ...

s. Catherine's successor, Paul I Paul I may refer to:

*Paul of Samosata (200–275), Bishop of Antioch

* Paul I of Constantinople (died c. 350), Archbishop of Constantinople

*Pope Paul I (700–767)

*Paul I Šubić of Bribir (c. 1245–1312), Ban of Croatia and Lord of Bosnia

*Pau ...

, successfully asked Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

in 1801 for formal approval of the Jesuit operation in Russia. The Jesuits, led first by Gabriel Gruber

Gabriel Gruber, S.J. (May 6, 1740 – April 7, 1805) was the second Superior General of the Society of Jesus in Russia.

Early years and education

Gabriel Gruber, born in Vienna, became a Jesuit at the young age of 15, in 1755 and did most of h ...

and after his death by Tadeusz Brzozowski, continued to expand in Russia under Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

, adding missions and schools in Astrakhan

Astrakhan ( rus, Астрахань, p=ˈastrəxənʲ) is the largest city and administrative centre of Astrakhan Oblast in Southern Russia. The city lies on two banks of the Volga, in the upper part of the Volga Delta, on eleven islands of the ...

, Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

, Riga, Saratov, and St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

and throughout the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

and Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

. Many former Jesuits throughout Europe traveled to Russia to join the sanctioned order there.

Alexander I withdrew his patronage of the Jesuits in 1812, but with the restoration of the Society in 1814, that had only a temporary effect on the order. Alexander eventually expelled all Jesuits from Imperial Russia in March 1820.[

]

Russian patronage of restoration in Europe and North America

Under the patronage of the "Russian Society", Jesuit provinces were effectively reconstituted in the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a Sovereign state, sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of ...

in 1803, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1803, and the United States in 1805. "Russian" chapters were also formed in Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

Acquiescence in Austria and Hungary

The Secularization Decree of Joseph II

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 un ...

(Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 and ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1780 to 1790) issued on 12 January 1782 for Austria and Hungary banned several monastic orders not involved in teaching or healing and liquidated 140 monasteries (home to 1484 monks and 190 nuns). The banned monastic orders included Jesuits, Camaldolese, Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, Carmelites

, image =

, caption = Coat of arms of the Carmelites

, abbreviation = OCarm

, formation = Late 12th century

, founder = Early hermits of Mount Carmel

, founding_location = Mount Ca ...

, Carthusians

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has i ...

, Poor Clares

The Poor Clares, officially the Order of Saint Clare ( la, Ordo sanctae Clarae) – originally referred to as the Order of Poor Ladies, and later the Clarisses, the Minoresses, the Franciscan Clarist Order, and the Second Order of Saint Francis ...

, Order of Saint Benedict

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

, Cistercians, Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers ( la, Ordo Praedicatorum) abbreviated OP, also known as the Dominicans, is a Catholic mendicant order of Pontifical Right for men founded in Toulouse, France, by the Spanish priest, saint and mystic Dominic of ...

(Order of Preachers), Franciscans

, image = FrancescoCoA PioM.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = A cross, Christ's arm and Saint Francis's arm, a universal symbol of the Franciscans

, abbreviation = OFM

, predecessor =

, ...

, Pauline Fathers

The Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit ( lat, Ordo Fratrum Sancti Pauli Primi Eremitæ; abbreviated OSPPE), commonly called the Pauline Fathers, is a monastic order of the Roman Catholic Church founded in Hungary during the 13th century.

Thi ...

and Premonstratensians

The Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré (), also known as the Premonstratensians, the Norbertines and, in Britain and Ireland, as the White Canons (from the colour of their habit), is a religious order of canons regular of the Catholic Church ...

, and their wealth was taken over by the Religious Fund.

His anticlerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

and liberal innovations induced Pope Pius VI to pay Joseph II a visit in March 1782. He received the Pope politely and presented himself as a good Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, but refused to be influenced.

Restoration of the Jesuits

As the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

were approaching their end in 1814, the old political order of Europe was to a considerable extent restored at the Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

after years of fighting and revolution, during which the Church had been persecuted as an agent of the old order and abused under the rule of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. With the political climate of Europe changed, and with the powerful monarchs who had called for the suppression of the Society no longer in power, Pope Pius VII issued an order restoring the Society of Jesus in the Catholic countries of Europe. For its part, the Society of Jesus made the decision at the first General Congregation held after the restoration to keep the organization of the Society the way that it had been before the suppression was ordered in 1773.

After 1815, with the Restoration, the Catholic Church began to play a more welcome role in European political life once again. Nation by nation, the Jesuits became re-established.

The modern view is that the suppression of the order was the result of a series of political and economic conflicts rather than a theological controversy, and the assertion of nation-state independence against the Catholic Church. The expulsion of the Society of Jesus

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

from the Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

nations of Europe and their colonial empires is also seen as one of the early manifestations of the new secularist ''zeitgeist

In 18th- and 19th-century German philosophy, a ''Zeitgeist'' () ("spirit of the age") is an invisible agent, force or Daemon dominating the characteristics of a given epoch in world history.

Now, the term is usually associated with Georg W. ...

'' of the Enlightenment.French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

. The suppression was also seen as being an attempt by monarchs to gain control of revenues and trade that were previously dominated by the Society of Jesus. Catholic historians often point to a personal conflict between Pope Clement XIII

Pope Clement XIII ( la, Clemens XIII; it, Clemente XIII; 7 March 1693 – 2 February 1769), born Carlo della Torre di Rezzonico, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 July 1758 to his death in February 1769. ...

(1758–1769) and his supporters within the church and the crown cardinal

A crown-cardinal ( it, cardinale della corona) was a cardinal protector of a Roman Catholic nation, nominated or funded by a Catholic monarch to serve as their representative within the College of Cardinals and, on occasion, to exercise the rig ...

s backed by France.[

]

See also

* Society of the Faith of Jesus

* Jesuit clause – clause banning Jesuits from Norway from 1814 to 1956

References

Bibliography

*

*

*

Further reading

* als

online

* Cummins, J. S. "The Suppression of the Jesuits, 1773" ''History Today'' (Dec 1973), Vol. 23 Issue 12, pp 839–848, online; popular account.

* Schroth, Raymond A. "Death and Resurrection: The Suppression of the Jesuits in North America." ''American Catholic Studies'' 128.1 (2017): 51–66.

* Van Kley, Dale. ''The Jansenists and the Expulsion of the Jesuits from France'' (Yale UP, 1975).

* Van Kley, Dale K. ''Reform Catholicism and the international suppression of the Jesuits in Enlightenment Europe'' (Yale UP, 2018)

online review

* Wright, Jonathan, and Jeffrey D Burson.'' The Jesuit Suppression in Global Context: Causes, Events, and Consequences.'' Cambridge University Press, 2015.

External links

*

Charles III of Spain's royal decree expelling the Jesuits

* Vogel, Christine

''The Suppression of the Society of Jesus, 1758–1773''

European History Online

European History Online (''Europäische Geschichte Online, EGO'') is an academic website that publishes articles on the history of Europe between the period of 1450 and 1950 according to the principle of open access.

Organisation

EGO is issued ...

, Mainz: Institute of European History The Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG) in Mainz, Germany, is an independent, public research institute that carries out and promotes historical research on the foundations of Europe in the early and late Modern period. Though autonomous i ...

, 2011, retrieved: November 11, 2011.

The Death of a Weak and Regretful Pope: September 22, 1774

at Catholic Text Book Project

{{DEFAULTSORT:Suppression Of The Society Of Jesus

18th-century Catholicism

Catholicism-related controversies

Catholic studies

Jesuit history in Europe

Jesuit history in South America

Jesuit history in North America

18th century in Portugal

18th century in Spain

18th century in France

18th century in Italy

History of Catholicism in France

History of Catholicism in Spain

History of Catholicism in Portugal

History of Catholicism in Italy

History of Catholicism in Brazil

Persecution of Catholics

Spanish colonization of the Americas

Spanish missions in the Americas

1763 disestablishments in Spain

1763 disestablishments in the Spanish Empire

Political repression

Anti-clericalism

The suppression of the Jesuits was the removal of all members of the

The suppression of the Jesuits was the removal of all members of the  The Suppression in Spain and in the Spanish colonies, and in its dependency the Kingdom of Naples, was the last of the expulsions, with Portugal (1759) and France (1764) having already set the pattern. The Spanish crown had already begun a series of administrative and other changes in their overseas empire, such as reorganizing the viceroyalties, rethinking economic policies, and establishing a military, so that the expulsion of the Jesuits is seen as part of this general trend known generally as the

The Suppression in Spain and in the Spanish colonies, and in its dependency the Kingdom of Naples, was the last of the expulsions, with Portugal (1759) and France (1764) having already set the pattern. The Spanish crown had already begun a series of administrative and other changes in their overseas empire, such as reorganizing the viceroyalties, rethinking economic policies, and establishing a military, so that the expulsion of the Jesuits is seen as part of this general trend known generally as the  When an angry crowd of those resisters converged on the royal palace, king Carlos fled to the countryside. The crowd had shouted "Long Live Spain! Death to Esquilache!" His Flemish palace guard fired warning shots over the people's heads. An account says that a group of Jesuit priests appeared on the scene, soothed the protesters with speeches, and sent them home. Carlos decided to rescind the tax hike and hat-trimming edict and to fire his finance minister.

The monarch and his advisers were alarmed by the uprising, which challenged royal authority, and the Jesuits were accused of inciting the mob and publicly accusing the monarch of religious crimes.

When an angry crowd of those resisters converged on the royal palace, king Carlos fled to the countryside. The crowd had shouted "Long Live Spain! Death to Esquilache!" His Flemish palace guard fired warning shots over the people's heads. An account says that a group of Jesuit priests appeared on the scene, soothed the protesters with speeches, and sent them home. Carlos decided to rescind the tax hike and hat-trimming edict and to fire his finance minister.

The monarch and his advisers were alarmed by the uprising, which challenged royal authority, and the Jesuits were accused of inciting the mob and publicly accusing the monarch of religious crimes.  King Charles's ministers kept their deliberations to themselves, as did the king, who acted upon "urgent, just, and necessary reasons, which I reserve in my royal mind." The correspondence of

King Charles's ministers kept their deliberations to themselves, as did the king, who acted upon "urgent, just, and necessary reasons, which I reserve in my royal mind." The correspondence of  Due to the isolation of the Spanish missions on the Baja California peninsula, the expulsion decree did not arrive in Baja California in June 1767, as in the rest of New Spain. It got delayed until the new governor,

Due to the isolation of the Spanish missions on the Baja California peninsula, the expulsion decree did not arrive in Baja California in June 1767, as in the rest of New Spain. It got delayed until the new governor,