Suleiman I of Persia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Suleiman I (; born Sam Mirza, February or March 1648 – 29 July 1694) was the eighth and the penultimate

In the hours after the death of Abbas II, the ''yuzbashi'' Sulaman Aqa called for a meeting between the notables presented in the shah's camp. Behind the close doors, he told them that the shah was dead and that they should choose his heir before leaving for the capital,

In the hours after the death of Abbas II, the ''yuzbashi'' Sulaman Aqa called for a meeting between the notables presented in the shah's camp. Behind the close doors, he told them that the shah was dead and that they should choose his heir before leaving for the capital,

Soon after his coronation, Safi faced problems. Two barren harvests left the central parts of the realm under famine and an earthquake in November 1667 in

Soon after his coronation, Safi faced problems. Two barren harvests left the central parts of the realm under famine and an earthquake in November 1667 in

After Shaykh Ali's reappointment, the shah's court grew intimated and afraid of him. Suleiman showed extreme cruelty towards his courtiers: in 1679, he forced Shaykh Ali to shave his beard (so that he would look like

After Shaykh Ali's reappointment, the shah's court grew intimated and afraid of him. Suleiman showed extreme cruelty towards his courtiers: in 1679, he forced Shaykh Ali to shave his beard (so that he would look like

Unlike his father, Suleiman was more religiously minded: he did not share his father's interest in Christianity, issued several decrees to ban the drinking of alcohol. His erratic behaviour makes it difficult to speculate how zealous he was towards the Shi'ia tradition: he only once gave up drinking, in 1667: not for any religious reasons, but for his health and in particular an

Unlike his father, Suleiman was more religiously minded: he did not share his father's interest in Christianity, issued several decrees to ban the drinking of alcohol. His erratic behaviour makes it difficult to speculate how zealous he was towards the Shi'ia tradition: he only once gave up drinking, in 1667: not for any religious reasons, but for his health and in particular an

Suleiman lacked the best qualities his father was known for: energy, courage, decisiveness, discipline, initiative and an eye for the national interest, and after his second enthronement, it became clear that he neither desired nor was able to acquire them. Most of the contemporary observers speak of Suleiman's character as idle, gluttonous and lascivious, and also mention his tendency to extort his subjects for money. Throughout his life, Suleiman increasingly cherished wine and women, to such a degree that foreign observers asserted that no Persian ruler had ever indulged so greatly in both. He spent many an evening drinking with high court officials and under him the royal

Suleiman lacked the best qualities his father was known for: energy, courage, decisiveness, discipline, initiative and an eye for the national interest, and after his second enthronement, it became clear that he neither desired nor was able to acquire them. Most of the contemporary observers speak of Suleiman's character as idle, gluttonous and lascivious, and also mention his tendency to extort his subjects for money. Throughout his life, Suleiman increasingly cherished wine and women, to such a degree that foreign observers asserted that no Persian ruler had ever indulged so greatly in both. He spent many an evening drinking with high court officials and under him the royal

Suleiman's reign saw the final stages of Iran's monetary unification system. The '' larin'' currency was discontinued during his reign, and only the ''mohammadis'' currency from

Suleiman's reign saw the final stages of Iran's monetary unification system. The '' larin'' currency was discontinued during his reign, and only the ''mohammadis'' currency from

Shah

Shah (; fa, شاه, , ) is a royal title that was historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies.Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) It was also used by a variety of ...

of Safavid Iran

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often conside ...

from 1666 to 1694. He was the eldest son of Abbas II and his concubine, Nakihat Khanum. Born as Sam Mirza, Suleiman spent his childhood in the harem among women and eunuchs and his existence was hidden from the public. When Abbas II died in 1666, his grand vizier, Mirza Mohammad Karaki, did not know that the shah had a son. The nineteen-years-old Sam Mirza was crowned king under the regnal name

A regnal name, or regnant name or reign name, is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and, subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they ...

, Safi II, after his grandfather, Safi I. His reign as Safi II undergone troublesome events which led to a second coronation being held for him in 20 March 1668, simultaneously with Nowruz

Nowruz ( fa, نوروز, ; ), zh, 诺鲁孜节, ug, نەۋروز, ka, ნოვრუზ, ku, Newroz, he, נורוז, kk, Наурыз, ky, Нооруз, mn, Наурыз, ur, نوروز, tg, Наврӯз, tr, Nevruz, tk, Nowruz, ...

, in which he was crowned king as Suleiman I.

After his second coronation, Suleiman retreated into his harem

Harem ( Persian: حرمسرا ''haramsarā'', ar, حَرِيمٌ ''ḥarīm'', "a sacred inviolable place; harem; female members of the family") refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A har ...

to enjoy sexual activities and excessive drinking. He was indifferent to the state affairs, and often would not appear in the public for months. As a result for his idleness, Suleiman's reign was devoid of spectacular events in the form of major wars and rebellions. For this reason, Western contemporary historians regard Suleiman's reign as "remarkable for nothing" while the Safavid court chronicles refrained from recording his tenure. Suleiman's reign saw the decline of the Safavid army, to the point when the soldiers became undisciplined and made no effort to serve as it was required of them. At the same time, the eastern borders of the realm was under the constant raids from the Uzbeks

The Uzbeks ( uz, , , , ) are a Turkic ethnic group native to the wider Central Asian region, being among the largest Turkic ethnic group in the area. They comprise the majority population of Uzbekistan, next to Kazakh and Karakalpak mino ...

, and the Kalmyks

The Kalmyks ( Kalmyk: Хальмгуд, ''Xaľmgud'', Mongolian: Халимагууд, ''Halimaguud''; russian: Калмыки, translit=Kalmyki, archaically anglicised as ''Calmucks'') are a Mongolic ethnic group living mainly in Russia, w ...

.

On 29 July 1694, Suleiman died from a combination of gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

and his chronic alcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

. Often seen as a failure in kingship, Suleiman's reign was the starting point of the Safavid ultimate decline: weakened military power, falling agricultural output and the corrupt bureaucracy, all were a forewarning of the troubling rule of his successor, Soltan Hoseyn, whose reign saw the end of the Safavid dynasty

The Safavid dynasty (; fa, دودمان صفوی, Dudmâne Safavi, ) was one of Iran's most significant ruling dynasties reigning from 1501 to 1736. Their rule is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of th ...

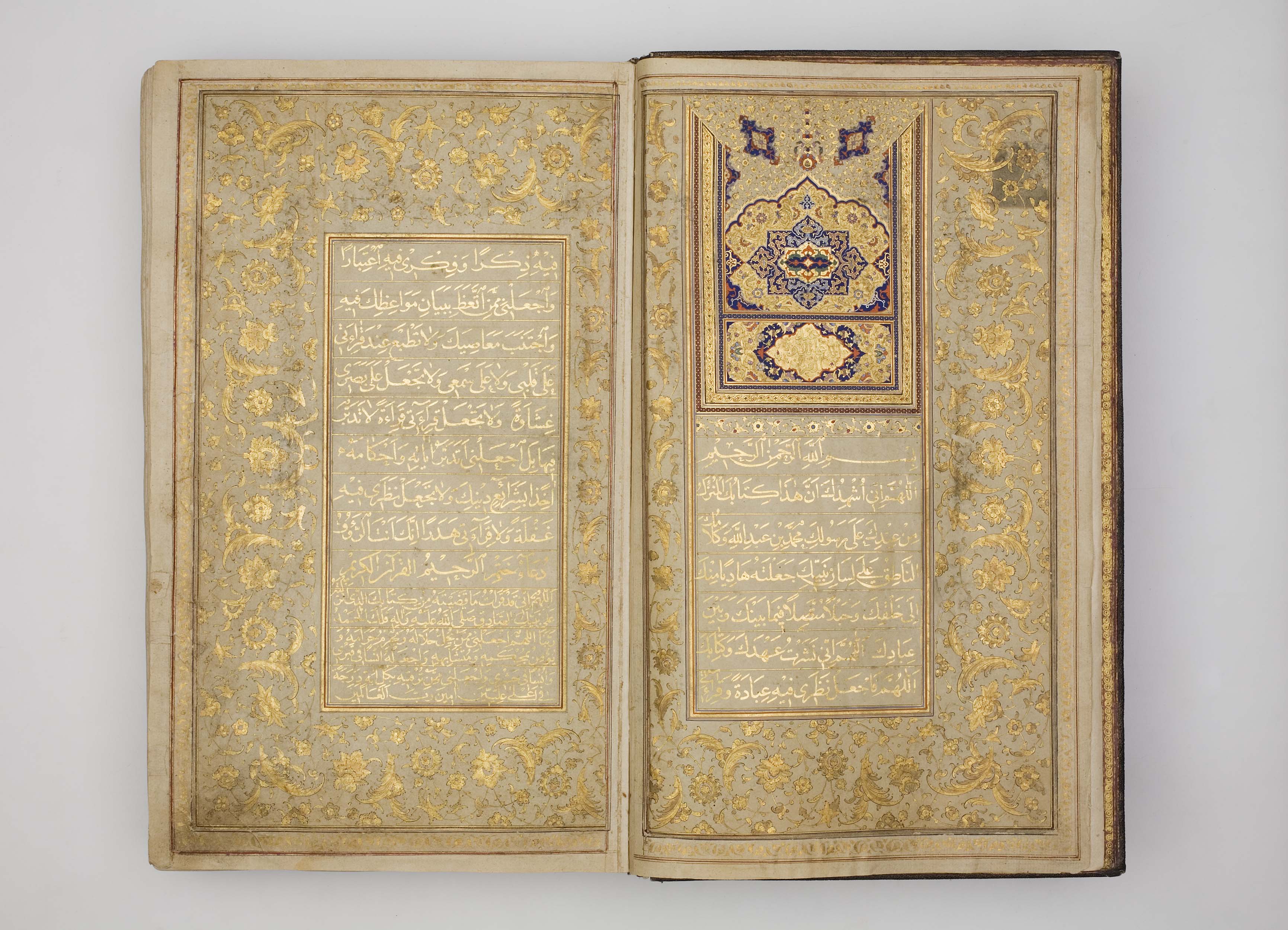

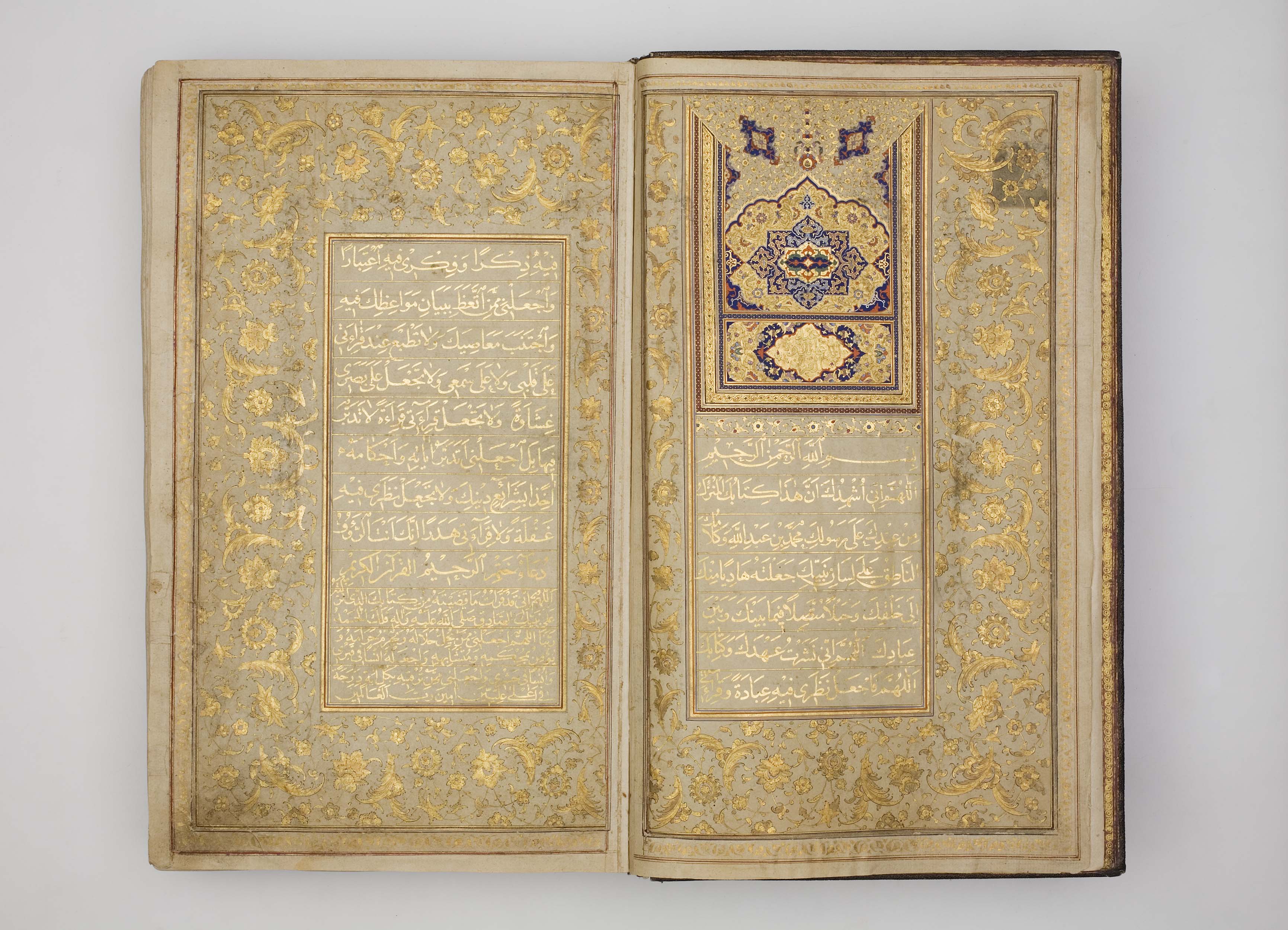

. Suleiman was the first Safavid Shah that did not patrol his kingdom and never led an army, thus giving away the government affairs to the influential court eunuchs, harem women and the Shi‘i high clergy. Perhaps the only admiring aspect of his reign was the appreciation of art, for the ''Farangi-Sazi

Farangi-Sazi () was a style of Persian painting that originated in Safavid Iran

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of ...

'', or the Western painting style, saw its zenith under Suleiman's sponsorship.

Background

Suleiman's father, Abbas II, was the seventh Shah of Safavid Iran. Like Suleiman, Abbas had spent his childhood years in the harem, until in 1642, when he ascended the throne at the age of nine. Thereafter, he found a chance to undertake the kingly education and learned how to read and write by the age of ten. Abbas had an energetic personality and his desire to rule alone led him to purge the ranks of bureaucracy in 1645 and end his regency. In 1649, Abbas led an army to retakeKandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population of about 614,118. It is the c ...

, a bone of contention between the Safavid and the Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

originating back to Tahmasp I

Tahmasp I ( fa, طهماسب, translit=Ṭahmāsb or ; 22 February 1514 – 14 May 1576) was the second shah of Safavid Iran from 1524 to 1576. He was the eldest son of Ismail I and his principal consort, Tajlu Khanum. Ascending the throne after ...

's reign. The war, though successful, was one of the reasons for a financial decline later in his reign which plagued the Safavid Empire until its dissolution. After the war for Kandahar, the Safavid army during Abbas' reign undertook two further military campaigns in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historica ...

: one

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1. I ...

in 1651 to destroy the Russian fortress on the Iranian side of the Terek river

The Terek (; , Tiyrk; , Tərč; , ; , ; , ''Terk''; , ; , ) is a major river in the Northern Caucasus. It originates in the Mtskheta-Mtianeti region of Georgia and flows through North Caucasus region of Russia into the Caspian Sea. It rise ...

(which the Safavids considered as part of their realm), and one in 1659 to suppress the Georgian rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

. Abbas' reign was scarce of rebellion and relatively peaceful. A consequence of this peace was the decline of the army, which started during his reign and saw its peak in the reign of his successors.

Abbas' relations with the Uzbeks

The Uzbeks ( uz, , , , ) are a Turkic ethnic group native to the wider Central Asian region, being among the largest Turkic ethnic group in the area. They comprise the majority population of Uzbekistan, next to Kazakh and Karakalpak mino ...

were peaceful. He made arrangements with Uzbeks of Bukhara under which they agreed to stop raiding into Iranian territory. The arrival of Nader Mohammad Khan in Isfahan in 1646, after he was overthrown from his rule by his son, Abd al-Aziz Khan, disturbed relations between the Uzbeks and Safavids. Abbas managed to establish a truce between the father and his son, with Nader Mohammad Khan receiving an escort from the shah and Abd al-Aziz allowing his father to settle in Herat

Herāt (; Persian: ) is an oasis city and the third-largest city of Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains (''Selseleh-ye Safē ...

. However, conflict between the two soon arose in early 1650s which led to Nader Mohammad again taking shelter in Isfahan and dying in 1653 en route to there. Relations with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

were likewise peaceful, despite tensions during Abbas' reign in Transcaucasia

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Arme ...

, where the risk of war was so acute that the governor of the Turkish border provinces had evacuated the civilian population in expectation of an Iranian attack, and in Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

, where the shah's aid had been sought to settle a struggle for the succession.

Abbas II's concern for state affairs has been judged as greater than that of any of the other successors of Abbas the Great

Abbas I ( fa, ; 27 January 157119 January 1629), commonly known as Abbas the Great (), was the 5th Safavid Shah (king) of Iran, and is generally considered one of the greatest rulers of Iranian history and the Safavid dynasty. He was the third son ...

. Praised for his sense of justice, he sat aside three days of the week whereon he would listen to people's petitions. He was always quick to deal with any injustice in cases of despotism, irregularities or malpractices, whether a normal case of administration of justice or a major political and social scandal. Indeed, his efforts to develop the well-being of his subjects improved the lives of the Iranian rural population versus that of peasants in the West, according to Western observers, who were astonished by Iran's safe roads and the scarcity of rebellions.

Early life

Sam Mirza was born in February or March 1648 as the eldest son of Abbas II and his concubine, Nakihat Khanum. He grew up in the royal Safavid harem under the guardianship of a black eunuch named Agha Nazer. According toJean Chardin

Jean Chardin (16 November 1643 – 5 January 1713), born Jean-Baptiste Chardin, and also known as Sir John Chardin, was a French jeweller and traveller whose ten-volume book ''The Travels of Sir John Chardin'' is regarded as one of the finest ...

, the French traveler, Sam Mirza was known for his arrogance. His first language was Azeri Turkish, and it is unclear to what degree he was able to understand Persian. Reportedly, Abbas II was not on good terms with Sam Mirza — it was rumoured that the shah had blinded the young prince — and favoured Sam Mirza's younger brother, Hamza Mirza, the son of a Circassian concubine.

At the end of 1662. Abbas II showed the first symptoms of syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium '' Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, a ...

. On 26 October 1666, while in his winter residence at Behshahr

Behshahr ( fa, بهشهر; formerly Ashraf and Ashraf ol Belād) is a city in Mazandaran, Iran & the capital of Behshahr County. Located on the coast of the Caspian Sea, at the foot of the Alborz, it is approximately from Sari. At the 2006 cen ...

, he died of a combination of syphilis and throat cancer as a result of his excessive drinking at the age of thirty-four. It was said that on his deathbed, Abbas II foretold the fate of his successor to be one of perpetual turmoil and disaster.

Reign as Safi II

First Coronation

In the hours after the death of Abbas II, the ''yuzbashi'' Sulaman Aqa called for a meeting between the notables presented in the shah's camp. Behind the close doors, he told them that the shah was dead and that they should choose his heir before leaving for the capital,

In the hours after the death of Abbas II, the ''yuzbashi'' Sulaman Aqa called for a meeting between the notables presented in the shah's camp. Behind the close doors, he told them that the shah was dead and that they should choose his heir before leaving for the capital, Isfahan

Isfahan ( fa, اصفهان, Esfahân ), from its ancient designation ''Aspadana'' and, later, ''Spahan'' in middle Persian, rendered in English as ''Ispahan'', is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Region, Isfahan Province, Iran. It is lo ...

. The shah's grand vizier, Mirza Mohammad Karaki, responded with "What do I know?" and "I have no knowledge of what goes on in the interior of the palace." when asked about the shah's offspring. It was the eunuchs of the inner palace that informed the notables of the existence of two sons, the nineteen-year-old Sam Mirza, and Hamza Mirza, who was only seven-years-old.

The eunuchs, who were eager to have a pliable child on the throne and believed the rumour about Sam Mirza's blindness, announced their support for Hamza Mirza. The grand vizier also declared his support for Hamza Mirza's claim. At this point, Agha Mubarak, Hamza's '' lala'' (guardian), made an argument in favour of Sam Mirza, against his own interests and those of his eunuch colleagues. He accused the eunuchs of opting for Hamza Mirza for selfish reasons. He pointed out that Sam Mirza was not blinded by the orders of his father and argued that he was more worthier than a mere child. And at last, Agha Mubarak's argument prevailed.

The ''Tofangchi-aghasi

The Tofangchi-aghasi, also spelled Tufangchi-aqasi, and otherwise known as the Tofangchi-bashi, was the commander of the Safavid Empire's musketeer corps. The ''tofangchi-aghasi'' was assisted by numerous officers, i.e. ''minbashis'', ''yuzbashi ...

'', Khosrow Soltan Armani, by reputation the least trustworthy among the eunuchs, was chosen to go to Isfahan to announce the new heir before word of the death of Abbas II could spread. Sam Mirza, who had been surrounded by women and eunuchs all his life and had not seen the world outside of the harem, was then brought out of the inner palace, dazzled and unsure what to do with the responsibility thrust upon him. He was seized with panic when asked to appear before the throne room for the coronation, and reluctantly accepted the invitation because he assumed that he was being lured there simply to be murdered or blinded.

On 1 November 1666, six days after Abbas II's death, Sam Mirza was crowned king under the name Safi II, after his grandfather, Safi I, at one o’clock in the afternoon in a ceremony persisted by Mohammad Bagher Sabzevari

Mohammad Bagher Sabzevari ( fa, محمدباقر سبزواری) known as Mohaghegh Sabzevari ( fa, محقق سبزواری) (born in 1608, died on 19 April 1679) was an Iranian Faqih and Shiite scholar from the 11th century AH, Shaykh al-Is ...

, the ''shaykh al-Islam

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

'' of Isfahan. The new king received the heads of killed Uzbeks and rewarded the slayers with money. He also allotted money to 300 Turkish refugees from the Ottoman Empire, who had sought shelter in Isfahan. As a sign of smooth transition of power, Isfahan remained peaceful: the shops remained open and started doing their business with the new coins of Safi II, and everyday life remained unchanged. Foreign residents, who had locked their houses in fear of uprisings and looting, again emerged into the city.

Turmoil and disasters

Soon after his coronation, Safi faced problems. Two barren harvests left the central parts of the realm under famine and an earthquake in November 1667 in

Soon after his coronation, Safi faced problems. Two barren harvests left the central parts of the realm under famine and an earthquake in November 1667 in Shirvan

Shirvan (from fa, شروان, translit=Shirvān; az, Şirvan; Tat: ''Şirvan''), also spelled as Sharvān, Shirwan, Shervan, Sherwan and Šervān, is a historical Iranian region in the eastern Caucasus, known by this name in both pre-Islam ...

led to the death of more than 30,000 in the villages and around 20,000 in its capital city, Shamakhi

Shamakhi ( az, Şamaxı, ) is a city in Azerbaijan and the administrative centre of the Shamakhi District. The city's estimated population was 31,704. It is famous for its traditional dancers, the Shamakhi Dancers, and also for perhaps giving it ...

. In the following year, the Northern provinces of the realm endured raids by Stenka Razin

Stepan Timofeyevich Razin (russian: Степа́н Тимофе́евич Ра́зин, ; 1630 – ), known as Stenka Razin ( ), was a Cossack leader who led a major uprising against the nobility and tsarist bureaucracy in southern Russia in 16 ...

's Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

, whom the Safavid army was unable to subdue. The Cossacks had raided these provinces before, in 1664, when they were defeated by local forces. Now, under the leadership of Razin, they ransacked Mazandaran and attacked Daghestan. Razin went to Isfahan to ask Safi for land in his realm in exchange for loyalty to the shah, but departed on the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central A ...

for more pillaging before they could reach an agreement. The tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, Alexis, made a delegation to Isfahan in order to apologise for the damages done and later in 1671, hanged Razin as a rebel.

Meanwhile, there were internal problems. Safi caught an unspecified illness that in August 1667, which deteriorated his health to such a degree that many were worried that he might die, causing the grandees of the court to arrange a public prayer for his well-being while giving out 1,000 tomans to the poor. The shah squandered his government’s resources as part of endowments to the poor. As a result of his naive belief that the royal coffers could never end, the treasury became empty and the money, already scarce in Isfahan, became even scarcer.

Second Coronation

During Safi's time of illness, a physician, who was trying in vain to cure the shah, suggested that his misfortune must have come from a miscalculation in determining the date of the coronation. Soon, a court astrologer confirmed this assumption, and the court, the queen mother, Nakihat Khanum, and the leading eunuchs, with the shah in their support, concluded that the coronation should be repeated and Safi should be crowned king under a new name. Thus, in March 1668, at nine o cloak in morning, simultaneously withNowruz

Nowruz ( fa, نوروز, ; ), zh, 诺鲁孜节, ug, نەۋروز, ka, ნოვრუზ, ku, Newroz, he, נורוז, kk, Наурыз, ky, Нооруз, mn, Наурыз, ur, نوروز, tg, Наврӯз, tr, Nevruz, tk, Nowruz, ...

, a second coronation for the shah was held in the Chehel Sotoun Palace. The ceremony was preceded by an unorthodox ritual. As told by Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who witnessed it, a Zoroastrian, "descended from the old kings", was put on the Shah's throne with his back tied to a wooden statue. The attendants paid their respects to him until an hour before sunset, the time for the real coronation. At that point an official came up from behind and cut off the head of the statue, whereupon the Zoroastrian fled and Safi II appeared. The Safavid bonnet was next put on his head, and he was girded with a sword, and Safi II took on the name Abu'l-Muzzafar Abu'l-Mansur Shah Suleiman Safavi Mousavi Bahador Khan, with the name Suleiman referring to King Solomon

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ti ...

.

After the coronation, new royal seals and coins were made under the name Suleiman I and within twenty-four hours a large quantity of new money was struck. At the same time, a comet appeared in the sky, which was taken as a sign of the event's auspiciousness.

Reign as Suleiman I

Royal isolation

It was soon proven that a repeated coronation and a new name was not a step closer to the improvement of the state. Suleiman, after his coronation, retreated into the depths of the harem and began a policy of royal isolation. He would not appear in public and often preferred to stay in Isfahan rather than travel throughout the country. He only went out of the palace in form of a ''quruq'', meaning he would order the people of a neighbourhood to vacate their district and move away to a different one so that Suleiman and the women of the harem as his entourage, could ride freely in that district. No male older than six was allowed to be in that district when the shah and his companions came riding, if a man was caught, he would be executed. Suleiman, unlike his father, no longer allowed his subjects to enter his palace and petition him. In fact, he would not emerge from the inner palace for periods of up to twelve days, during which he would not accept anyone outside the harem to disturb him. For the first fifteen years of his reign, women were still allowed to accost him during his ''quruqs:'' in 1683, this access was formally abolished altogether. Contemporary observers often considered Suleiman's reign after his second coronation to be devoid of any notable events, and who refrained from recording the period in chronicle form. Mohammad Shafi Tehrani, the Qajar historian, claims that the Uzbek and Kalmyk raids of Astarabad were the only significant events of his reign. Modern historians, however, argue otherwise. It has been suggested that Suleiman may have had greater control over the state than its generally assumed: out of eleven '' firmans'' collected in acompendium

A compendium (plural: compendia or compendiums) is a comprehensive collection of information and analysis pertaining to a body of knowledge. A compendium may concisely summarize a larger work. In most cases, the body of knowledge will concern a s ...

by Heribert Busse, seven were directly issued by Suleiman, and three of them are of his own wording while four were clearly worded by his grand vizier. Suleiman was self-aware enough to choose a competent grand vizier who would rule in his stead while Suleiman enjoyed his lavish lifestyle. His choice was Shaykh Ali Khan Zanganeh, a statesman who served as his grand vizier for twenty years.

Grand Vizierate of Shaykh Ali Khan

Given Suleiman's reclusive nature, and thus the scarcity of sources regarding his deeds, modern historians incorporate the tenure of Shaykh Ali Khan Zanganeh as the grand vizier into his rule. Shaykh Ali Khan was the Amir of the Zanganeh tribe and succeeded Mirza Mohammad Karaki (who had maintained his position after Suleiman's ascension) as the grand vizier in 1669. Faced with an empty treasury after a series of misfortunes, Shaykh Ali immediately commenced a financial policy that combined cutting expenses with increasing revenue. He sought a stricter observation on the annual silk supply to the VOC, who, using the chaos in the capital, took a greater supply of silk than had initially been agreed upon. Moreover, he attempted to take control over the monopoly of sugar and instituted a five-percent tax on the merchants who shipped sugar toIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

. Shaykh Ali imposed new taxes on the New Julfa

New Julfa ( fa, نو جلفا – ''Now Jolfā'', – ''Jolfâ-ye Now''; hy, Նոր Ջուղա – ''Nor Jugha'') is the Armenian quarter of Isfahan, Iran, located along the south bank of the Zayande River.

Established and named after the ol ...

churches and the Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, ''hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

who lived in the villages around Isfahan. Through all of his projects, Shaykh Ali showed diligence, and, in contrast to many of his colleagues, refused to accept bribery, and soon became known for his incorruptibility. It is true that few of his projects were completely successful, nevertheless, Shaykh Ali was highly effective in collecting revenue for the royal treasury.

Shaykh Ali Khan's policies made him enemies amongst the courtiers, who disliked his attempts to curb the lavish lifestyle of the court. He also urged Suleiman to follow a path of frugality, which further infuriated his adversaries who were dependent on the shah's generosity. Shaykh Ali's fall from the shah's grace took place in early 1672, when the shah ordered his grand vizier to drink wine: when he refused, Suleiman forced him to drink and spent hours humiliating him. Shaykh Ali Khan was soon arrested, and the realm fell into turmoil. In the same year, one of his sons took refuge with the Ottomans, raising fears of a potential war. Fourteen months after his removal, Suleiman reappointed Shaykh Ali as his grand vizier to quiet the rumours of the war. Having resumed his position, Shaykh Ali started to curb the military outlay and sent tax-collectors to the provinces, demanding taxes and imposing fines for unpaid obligations. Shaykh Ali decided to no longer inform the shah of the reality of the state affairs, and he started shunning responsibilities, handing requests to Suleiman and urging him to ratify them without first reading and inspecting them. Shaykh Ali still provoked Suleiman's wrath from time to time by refusing drinks from him: the shah's outbursts would always result in humiliation of the grand vizier, but normally, Suleiman would feel remorse for his mockery and would send the grand vizier a robe of honour

A robe of honour ( ar, خلعة, khilʿa, plural , or ar, تشريف, tashrīf, pl. or ) was a term designating rich garments given by medieval and early modern Islamic rulers to subjects as tokens of honour, often as part of a ceremony of appoi ...

as a token of appreciation for his efforts.

As the years went by, Suleiman showed less and less desire to partake in the frequent meetings with his grand vizier regarding the state affairs. Hence, the grand vizier was left on his own when important decisions were to be made, while Suleiman would discuss the state affairs with his wives and the eunuchs, who were his confidants. His wives and eunuchs thus exercised a dominant influence upon the shah, and guarded their influence and were keen to prevent the shah from communicating with anyone but themselves. Suleiman even set up a privy council in the harem, to which the most important eunuchs belonged. Even when the shah would discuss the state affairs with his grand vizier, it was impossible to discuss them in detail because Suleiman was impatient and bitter towards the problems that had risen throughout the realm.

The vacant court positions

After Shaykh Ali's reappointment, the shah's court grew intimated and afraid of him. Suleiman showed extreme cruelty towards his courtiers: in 1679, he forced Shaykh Ali to shave his beard (so that he would look like

After Shaykh Ali's reappointment, the shah's court grew intimated and afraid of him. Suleiman showed extreme cruelty towards his courtiers: in 1679, he forced Shaykh Ali to shave his beard (so that he would look like Georgians

The Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ქართველები, tr, ), are a nation and indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. Georgian diaspora communities are also present throughout Russia, Turkey, ...

, whom he despised for their Christianity), and because the beard was not cleanly shaven, he had the barber executed as well; in 1680, he blinded the '' divan-begi'', Zaynal Khan; and, he had Shaykh Ali and one of his royal secretariats bastinadoed; in 1681, he killed one of his sons, who was fourteen years old at the time. The boy had spent his whole life in the harem wearing women’s clothes at the prompting of astrologers, who had seen a prophesy that he would depose Suleiman. Many of the courtiers were so afraid of the shah that they would leave the court with the excuse of undertaking hajj

The Hajj (; ar, حَجّ '; sometimes also spelled Hadj, Hadji or Haj in English) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried o ...

. In early 1681, Shaykh Ali made a request to undertake hajj, however, for unknown reason was rejected. The shah’s erratic and unpredictable behavior led the courtiers to became sycophants towards him, flattering the shah and hiding unpleasant news from him, while also forsaking their duties and embracing corruption. The army, in general, became undisciplined and its military standards fell, as soldiers came to regard their pay as little more than a gratuity. Some military formations existed only on paper.

Despite his continued insecurity and his limited contact with the shah, Shaykh Ali Khan maintained his position even during 1680s, when most of the court positions were vacant and unfilled. In 1680, the shah took the position of ''sadr-i mamalik'' (minister of religion) for himself; the royal secretariat were all dismissed in 1682. In the same year, the position of ''sepahsalar

''Ispahsālār'' ( fa, اسپهسالار) or ''sipahsālār'' (; "army commander"), in Arabic rendered as ''isfahsalār'' () or ''iṣbahsalār'' (), was a title used in much of the Islamic world during the 10th–15th centuries, to denote the sen ...

'' became vacant after the death of its holder, and remained as much until the end of Suleiman's reign. In addition, the positions of ''divan-begi'', ''qurchi-bashi

The Qurchi-bashi ( fa, قورچیباشی), also spelled Qorchi-bashi (), was the head of the '' qurchis'', the royal bodyguard of the Safavid shah. There were also ''qurch-bashis'' who were stationed in some of the provinces and cities. T ...

'', ''shaykh al-Islam

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

'', and ''mirshekar-bashi'' (master of the hunt), all became vacant in the same year. Shaykh Ali Khan died in 1689 while still occupying the grand vizier position. Saddened by his death, Suleiman, who had mistreated his grand vizier for twenty years, did not leave the inner palace for a full year and did not choose a successor for two years. In 1691, Mohammad Taher Vahid Qazvini

Mirza Mohammad Taher Vahid Qazvini ( fa, محمد طاهر وحید قزوینی; died 1700), was a Persian bureaucrat, poet, and historian, who served as the grand vizier of two Safavid monarchs, Shah Suleiman () and the latter's son Soltan Hosey ...

, a poet and court historian, was chosen as the grand vizier.

Later years and death

The new grand vizier was given full and unprecedented executive powers to overcome the realm's most urgent needs and problems. However, Vahid Qazvini proved to be a venal and ineffective grand vizier: He was extremely old, being seventy years old at the time, and lacked the energy to administrate. Moreover, he freely took bribes. Vahid also made many enemies in the court: his main rival was Saru Khan Sahandlu, the new ''qurchi-bashi''. Saru Khan was from the Zanganeh tribe and was Suleiman's absolute favourite. In 1691, he killed forty members of his tribe, but the shah's favor meant that his crime was overlooked. However, he incurred Suleiman's wrath when it was discovered that he had started an affair with Maryam Begum, the shah's aunt. Suleiman ordered his death during an assembly in late 1691, during which he had offered wine to all the members presented except Saru Khan, and had him executed shortly after. During his later years, Suleiman became more and more reclusive and his drinking finally made him infirm. In 1691, per the suggestions of the astrologers, he did not leave the palace for nine months. Simultaneously, the realm saw much unrest: in 1689, the Uzbeks raided along the Khorasan borderline and rebellions broke out inBalochistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. ...

. In 1692, Suleiman Baba took up arms against the Safavids in Kurdistan

Kurdistan ( ku, کوردستان ,Kurdistan ; lit. "land of the Kurds") or Greater Kurdistan is a roughly defined geo-cultural territory in Western Asia wherein the Kurds form a prominent majority population and the Kurdish culture, languag ...

and rebellions are recorded in Kerman

Kerman ( fa, كرمان, Kermân ; also romanized as Kermun and Karmana), known in ancient times as the satrapy of Carmania, is the capital city of Kerman Province, Iran. At the 2011 census, its population was 821,394, in 221,389 households, ma ...

, Kandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population of about 614,118. It is the c ...

, Lar, and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Meanwhile, Suleiman was suffering from foot pain and in August 1692 it was rumoured that he had not left the palace for more than eighteen months. He did not appear in the hall of the Ali Qapu palace for the Nowruz festivities in 20 March 1694, and even declined to accept the customary gifts from governors and other grandees. The last time he was seen was on 24 March, when he presided over a very brief meeting, after which he returned to his harem. He did not leave the inner palace again until his death on 29 July 1694. Many reasons are suggested for his death, among them being having a stroke during a carousing session, dying from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

or from the decades of debauchery. According to the French cleric, Martin Gaudereau, his last words were: "Bring me wine." He was buried in Qom

Qom (also spelled as "Ghom", "Ghum", or "Qum") ( fa, قم ) is the seventh largest metropolis and also the seventh largest city in Iran. Qom is the capital of Qom Province. It is located to the south of Tehran. At the 2016 census, its pop ...

, like many of his ancestors, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Soltan Hoseyn, the last Safavid Monarch.

Policies

Religion

Unlike his father, Suleiman was more religiously minded: he did not share his father's interest in Christianity, issued several decrees to ban the drinking of alcohol. His erratic behaviour makes it difficult to speculate how zealous he was towards the Shi'ia tradition: he only once gave up drinking, in 1667: not for any religious reasons, but for his health and in particular an

Unlike his father, Suleiman was more religiously minded: he did not share his father's interest in Christianity, issued several decrees to ban the drinking of alcohol. His erratic behaviour makes it difficult to speculate how zealous he was towards the Shi'ia tradition: he only once gave up drinking, in 1667: not for any religious reasons, but for his health and in particular an inflammation

Inflammation (from la, inflammatio) is part of the complex biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants, and is a protective response involving immune cells, blood vessels, and molec ...

of the throat. During Suleiman's reign, Shia Islam was institutionalised as a functional arm of the state, however, dissent towards the shah was still heard. On numerous times, Shia scholars tried to dissuade Suleiman from drinking. One of these scholars, Mohammad Tahir Qomi, the ''shaykh al-Islam'' of Qom, was almost executed for criticising Suleiman. Suleiman also continued to practice and expand upon local and popular religious beliefs. He ensured that the Muharram

Muḥarram ( ar, ٱلْمُحَرَّم) (fully known as Muharram ul Haram) is the first month of the Islamic calendar. It is one of the four sacred months of the year when warfare is forbidden. It is held to be the second holiest month after ...

ceremonies were more of a festival than purely ‘devotional’. Cursing Yazd

Yazd ( fa, یزد ), formerly also known as Yezd, is the capital of Yazd Province, Iran. The city is located southeast of Isfahan. At the 2016 census, the population was 1,138,533. Since 2017, the historical city of Yazd is recognized as a Wor ...

(the Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheisti ...

main centre) and the Ottomans on these ceremonies was encouraged. The shah took upon himself to embellish several imamzadehs and other ‘popular’ religious sites. Furthermore, he continued to insist on the leadership of the Safavid ancestral Sufi order, the '' Safaviyya''.

In the struggle between the three main spiritual communities in this era (advocates of popular Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality ...

, philosophically-minded scholars, and sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

-minded ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

) the last group gained the upper hand in Suleiman's court. The ulama became ever more assertive and took advantage of Suleiman's indifference towards matters of state. Their new-found power manifested itself in the continued pressure on non-Shia Iranians; anti-Sufism essays increased greatly during this era. In 1678, the ulama of the capital accused Armenians and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

of responsibility for the drought that afflicted much of the country in that year. Several rabbis were murdered and the Jews of Isfahan only escaped death by paying 600 tumans.

Diplomacy

Connections with foreign nations reduced greatly during Suleiman's reign. Like his father, he avoided doing anything that might lead him into diplomatic difficulties. Even when it was possible to wage war against the Ottomans (who were themselves fighting against nations during this era), he steadfastly refused to violate the peace treaty which his grandfather, Shah Safi, had made with theSublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

in 1639, although repeated offers from Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

(in 1684 and 1685) and from Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

(in 1690) invited him to re-establish Iranian suzerainty there. On the same premise of keeping the peace with the Ottomans, Suleiman avoided relations with Europe except for a letter in 1668 or 1669 sent via the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

to Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651, and King of England, Scotland and Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest surviving child o ...

, asking him for skilled craftsmen. Suleiman even dismissed the Russian emissaries who arrived in Isfahan in 1670s to seek anti-Ottoman cooperation. The various European envoys who visited in 1684–1685 received the same response. No reciprocal missions to Europe have been recorded in this period.

During Suleiman's reign envoys from Mughal, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

and the Uzbek states arrived in Isfahan. However, only the Ottomans received a response. In 1669 and 1680, King Narai

King Narai the Great ( th, สมเด็จพระนารายณ์มหาราช, , ) or Ramathibodi III ( th, รามาธิบดีที่ ๓ ) was the 27th monarch of Ayutthaya Kingdom, the 4th and last monarch of the P ...

of the Siamese Kingdom of Ayutthaya

The Ayutthaya Kingdom (; th, อยุธยา, , IAST: or , ) was a Siamese kingdom that existed in Southeast Asia from 1351 to 1767, centered around the city of Ayutthaya, in Siam, or present-day Thailand. The Ayutthaya Kingdom is consid ...

sent envoys to the court of Suleiman. Their intentions were to request Safavid naval assistance against the Kingdom of Pegu

Bago (formerly spelt Pegu; , ), formerly known as Hanthawaddy, is a city and the capital of the Bago Region in Myanmar. It is located north-east of Yangon.

Etymology

The Burmese name Bago (ပဲခူး) is likely derived from the Mon langua ...

. An Iranian delegation under the command of Mohammad Rabi' ibn Mohammad Ebrahim was sent to the court of Narai in 1685. The details of this mission were recorded by Ibn Mohammad Ebrahim in his account, ''Safine-ye Solaymani

The ''Safine-ye Solaymani'' ("Ship of Solayman") is a Persian travel account of an embassy sent to the Siamese Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1685 by Suleiman I (1666–1694), King ('' Shah'') of Safavid Iran. The text was written by Mohammad Rabi ibn Moh ...

.'' The book consists of four parts and narrates the Iranians' journey to Siam and the Iranian community which existed in that country from the times of Abbas II. During Suleiman's reign, Iran continued to be a shelter for exiled notables of its eastern neighbours: for instance, in 1686, Suleiman offered shelter to Muhammad Akbar, the rebellious son of Aurangzeb

Muhi al-Din Muhammad (; – 3 March 1707), commonly known as ( fa, , lit=Ornament of the Throne) and by his regnal title Alamgir ( fa, , translit=ʿĀlamgīr, lit=Conqueror of the World), was the sixth emperor of the Mughal Empire, ruling ...

.

Arts

Paradoxically, given his intermittent relations with the west, the ''Farangi-Sazi

Farangi-Sazi () was a style of Persian painting that originated in Safavid Iran

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of ...

'' or the Western painting style saw its zenith during Suleiman's reign. He was an outstanding connoisseur

A connoisseur (French traditional, pre-1835, spelling of , from Middle-French , then meaning 'to be acquainted with' or 'to know somebody/something') is a person who has a great deal of knowledge about the fine arts; who is a keen appreciator o ...

and, as the patron of arts, influenced directly or indirectly some of the most impressive works of the three greatest painters of the late 17th century Iran: Aliquli Jabbadar

Aliquli Jabbadar (‘Alī-qolī Jabbadār) () was an Iranian artist, one of the first to have incorporated European influences in the traditional Safavid-era miniature painting. He is known for his scenes of the Safavid courtly life, especially h ...

, Mohammad Zaman and Mo'en Mosavver

Mo'en Mosavver or Mu‘in Musavvir ( fa, معین مصوّر, lit. Mo'en the painter) was a Persian miniaturist, one of the significant in 17th-century Safavid Iran. Not much is known about the personal life of Mo'en, except that he was born in c ...

. Suleiman inherited these painters from the patronage of his father, and promoted their works further by patronising both traditional Persian miniature

A Persian miniature ( Persian: نگارگری ایرانی ''negârgari Irâni'') is a small Persian painting on paper, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a '' muraqqa''. T ...

, at which Mosavver was a master, and the new tendencies inspired by Western painting which characterise the work of Aliquli and Mohammad Zaman. Suleiman's sense of aesthetics, if it had blossomed during more favourable circumstances, could have led to the development of a new artistic era in Iranian history.

Suleiman's patronage also extended to architecture. He built the Hasht Behesht

Hasht Behesht (, ), literally meaning "the Eight Heavens" in Persian, is a 17th-century pavilion in Isfahan, Iran. It was built by order of Suleiman I, the eighth shah of Iran's Safavid Empire, and functioned mainly as a private pavilion. It i ...

palace in Isfahan and ordered the repair of a number of buildings in Mashhad

Mashhad ( fa, مشهد, Mašhad ), also spelled Mashad, is the second-most-populous city in Iran, located in the relatively remote north-east of the country about from Tehran. It serves as the capital of Razavi Khorasan Province and has a po ...

, including the Shrine of Imam Riza, damaged during an earlier earthquake, and several schools. Moreover, many of courtiers during his reign began patronising buildings: Shaykh Ali Khan personally funded a caravanserai

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was a roadside inn where travelers ( caravaners) could rest and recover from the day's journey. Caravanserais supported the flow of commerce, information and people across the network of trade routes covering ...

in the northwest of Isfahan (built in 1678) and in 1679 patronised a mosque in Khaju quarter of the city. He also built a school in Hamadan

Hamadan () or Hamedan ( fa, همدان, ''Hamedān'') (Old Persian: Haŋgmetana, Ecbatana) is the capital city of Hamadan Province of Iran. At the 2019 census, its population was 783,300 in 230,775 families. The majority of people living in Ham ...

which he dedicated as a '' vaqf'' from his new-founded revenue.

Personality and appearances

Suleiman lacked the best qualities his father was known for: energy, courage, decisiveness, discipline, initiative and an eye for the national interest, and after his second enthronement, it became clear that he neither desired nor was able to acquire them. Most of the contemporary observers speak of Suleiman's character as idle, gluttonous and lascivious, and also mention his tendency to extort his subjects for money. Throughout his life, Suleiman increasingly cherished wine and women, to such a degree that foreign observers asserted that no Persian ruler had ever indulged so greatly in both. He spent many an evening drinking with high court officials and under him the royal

Suleiman lacked the best qualities his father was known for: energy, courage, decisiveness, discipline, initiative and an eye for the national interest, and after his second enthronement, it became clear that he neither desired nor was able to acquire them. Most of the contemporary observers speak of Suleiman's character as idle, gluttonous and lascivious, and also mention his tendency to extort his subjects for money. Throughout his life, Suleiman increasingly cherished wine and women, to such a degree that foreign observers asserted that no Persian ruler had ever indulged so greatly in both. He spent many an evening drinking with high court officials and under him the royal Nowruz

Nowruz ( fa, نوروز, ; ), zh, 诺鲁孜节, ug, نەۋروز, ka, ნოვრუზ, ku, Newroz, he, נורוז, kk, Наурыз, ky, Нооруз, mn, Наурыз, ur, نوروز, tg, Наврӯз, tr, Nevruz, tk, Nowruz, ...

festivities seem to have been drenched in alcohol. Suleiman's drunken states often led into unpleasant consequences, such when he ordered the blinding of one of his brothers. As for lasciviousness, Suleiman's harem included at least 500 women.

Suleiman was generally described as mild-manner, yet, there were times when he showed great rage, and even cruelty, especially when drunk. He enjoyed humiliating his courtiers by forcing them to drink alcohol. For the enforced drinking, a huge gold goblet was used, the capacity of which is variously given as about a pint and almost a gallon.

Regarding appearances, Jean Chardin described him as “tall and graceful, with blue eyes and blond hair dyed black and white skin.” This description seems to concur with that of Nicolas Sanson, who called Suleiman “tall, strong and active; a fine prince, a little too effeminate for a monarch who should be a warrior, with an aquiline nose, large blue eyes, a beard dyed black”.

Coinage

Suleiman's reign saw the final stages of Iran's monetary unification system. The '' larin'' currency was discontinued during his reign, and only the ''mohammadis'' currency from

Suleiman's reign saw the final stages of Iran's monetary unification system. The '' larin'' currency was discontinued during his reign, and only the ''mohammadis'' currency from Hoveyzeh

Hoveyzeh ( fa, هویزه; ar, الهويزة also romanized as Huwaiza, Havizeh, Hawiza, Hawīzeh, Hovayze, and Hovayzeh; also known as Hūzgān or Khūzgān) is a city and capital of Hoveyzeh County, Khuzestan Province, Iran. At the 2006 censu ...

, which gained special fame in Iran and abroad, was officially minted until the end of the shah’s rule.

There are no surviving Safi II coins left. Apparently, they were replaced by heavy silver coins

Silver coins are considered the oldest mass-produced form of coinage. Silver has been used as a coinage metal since the times of the Greeks; their silver drachmas were popular trade coins. The ancient Persians used silver coins between 612– ...

issued for the first time in Safavid history. After his second coronation, Suleiman issued coins with the distichs, "''Soleymān banda-ye shāh-e velāyat''" (Suleiman, the servant of the realm's majesty). Gold coins (weighing about 57 grams) were rarely minted whereas silver coins were struck throughout his reign, usually in Isfahan and, less often, in Qazvin

Qazvin (; fa, قزوین, , also Romanized as ''Qazvīn'', ''Qazwin'', ''Kazvin'', ''Kasvin'', ''Caspin'', ''Casbin'', ''Casbeen'', or ''Ghazvin'') is the largest city and capital of the Province of Qazvin in Iran. Qazvin was a capital of the ...

.

Legacy

The reign of Suleiman I is often seen as the start of the final decline of the Safavid realm. According to the modern historian Rudi Matthee, Suleiman was what the British historian Hugh Kennedy calls an "internal absentee" (in reference to the tenth-centuryAbbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

Al-Muqtadir

Abu’l-Faḍl Jaʿfar ibn Ahmad al-Muʿtaḍid ( ar, أبو الفضل جعفر بن أحمد المعتضد) (895 – 31 October 932 AD), better known by his regnal name Al-Muqtadir bi-llāh ( ar, المقتدر بالله, "Mighty in God"), w ...

), a ruler who "had no real appreciation of the constraints and limitations of the financial resources". He was a king who never reached “political adulthood” and come to be known as a weak and erratically cruel ruler whose drug-addled insouciance and predilection for the pleasures of the harem caused a great deal of harm to the country. Jonas Hanway

Jonas Hanway (12 August 1712 – 5 September 1786), was a British philanthropist and traveller. He was the first male Londoner to carry an umbrella and was a noted opponent of tea drinking.

Life

Hanway was born in Portsmouth, on the south co ...

, who visited Iran decades after the Siege of Isfahan, calls Suleiman's reign "remarkable for nothing but a slavish indolence, a savage and inhuman cruelty." Modern historians who unanimously see him as a failed king. According to Hans Robert Roemer, the only redeeming aspect of Suleiman's personality and regnant was his patronage of arts.

Suleiman gave up on the concept of ''siyast'' or the ruler’s punitive capacity, an indispensable ingredient of statecraft, and instead led his grand vizier rule for him.; As long as he had a competent grand vizier by his side, and as long as he himself intervened decisively at crucial moments, an idle shah was not necessarily fatal to good governance. With Shaykh Ali Khan, Suleiman chose a competent grand vizier. Yet, instead of supporting him wholeheartedly, he abused Sheykh Ali and forced him into inactivity. Suleiman was the first Safavid king who did not patrol his kingdom and never led an army; in these circumstances, power became concentrated in the hands of court eunuchs, harem women and the Shia high clergy, precluding a forward-looking policy based on a realistic assessment of challenges and opportunities.

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Suleiman 01 of Persia Safavid monarchs Iranian people of Circassian descent 17th-century monarchs of Persia 1648 births 1694 deaths Year of birth unknown Burials at Fatima Masumeh Shrine 17th-century Iranian people