Strato of Lampsacus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

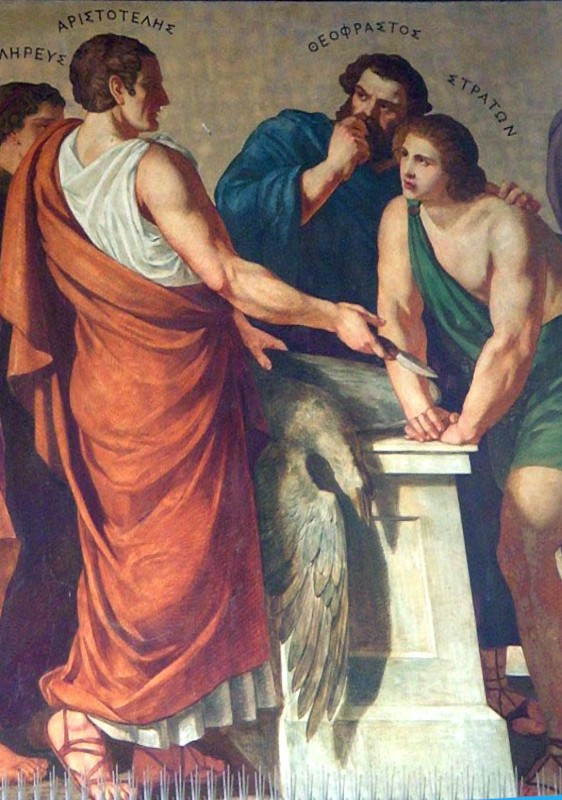

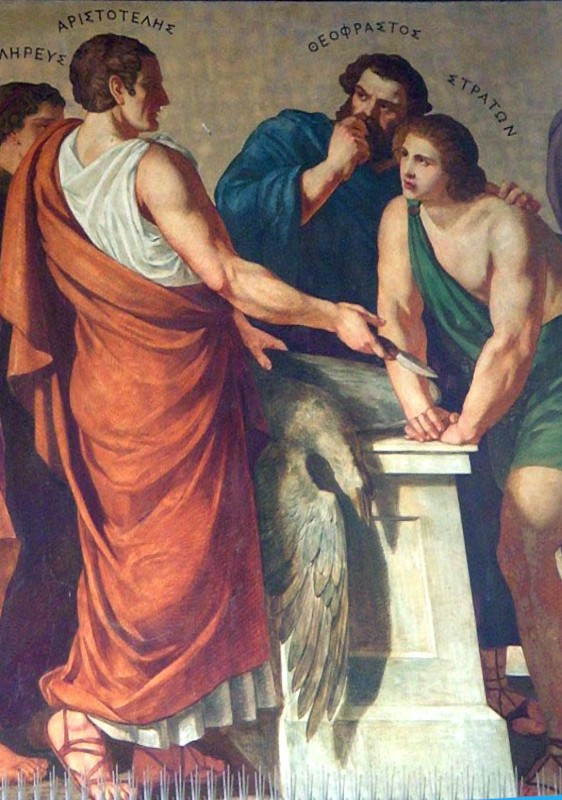

Strato of Lampsacus (; grc-gre, Στράτων ὁ Λαμψακηνός, Strátōn ho Lampsakēnós, – ) was a

Strato emphasized the need for exact

Strato emphasized the need for exact

Peripatetic

Peripatetic may refer to:

*Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BC), and ''peripatetic'' is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

...

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, and the third director (scholarch

A scholarch ( grc, σχολάρχης, ''scholarchēs'') was the head of a school in ancient Greece. The term is especially remembered for its use to mean the heads of schools of philosophy, such as the Platonic Academy in ancient Athens. Its fir ...

) of the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the t ...

after the death of Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

. He devoted himself especially to the study of natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

, and increased the naturalistic elements in Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

's thought to such an extent, that he denied the need for an active god to construct the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the univers ...

, preferring to place the government of the universe in the unconscious force of nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

alone.

Life

Strato, son of Arcesilaus or Arcesius, was born atLampsacus

Lampsacus (; grc, Λάμψακος, translit=Lampsakos) was an ancient Greek city strategically located on the eastern side of the Hellespont in the northern Troad. An inhabitant of Lampsacus was called a Lampsacene. The name has been transmitte ...

between 340 and 330 BCE. He might have known Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influence ...

during his period of teaching in Lampsacus between 310 and 306 BCE. He attended Aristotle's school in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

, after which he went to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

as tutor to Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

, where he also taught Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer and mathematician who presented the first known heliocentric model that placed the Sun at the center of the ...

. He returned to Athens after the death of Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

(c. 287 BCE), succeeding him as head of the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the t ...

. He died sometime between 270 and 268 BCE.

Strato devoted himself especially to the study of natural science, whence he obtained the name of ''Physicus'' ( el, Φυσικός). Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, while speaking highly of his talents, blames him for neglecting the most important part of philosophy, that which concerns virtue and morals, and giving himself up to the investigation of nature. In the long list of his works, given by Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sour ...

, several of the titles are upon subjects of moral philosophy

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ...

, but the great majority belong to the department of physical science. None of his writings survive, his views are known only from the fragmentary reports preserved by later writers.

Philosophy

Strato emphasized the need for exact

Strato emphasized the need for exact research

Research is "creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge". It involves the collection, organization and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular attentiveness ...

, and, as an example of this, he made use of the observation of how water pouring from a spout breaks into separate droplets as evidence that falling bodies accelerate

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Accelerations are vector quantities (in that they have magnitude and direction). The orientation of an object's acceleration is given by t ...

.

Whereas Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

defined time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

as the numbered aspect of motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and m ...

, Strato argued that because motion and time are continuous whereas number is discrete, time has an existence independent of motion, or simply that time was the quantitative aspect of motion, rather than its numerical aspect. Simplicius preserves the following quotation in his commentary on Aristotle's ''Physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

'':

For we say we that we go abroad or sail or go on a military campaign or wage war for much time or for little time, and similarly, that we sit and sleep and do nothing for much time and for little time: for much time in the cases where the quantity is much, for little where it is little. For time is the quantitative in each of these. And this is why some people say that one and the same hingcame slowly, others quickly, according to how the quantitative in this seems to each group. For we saw that that is quick in which the quantity from when it began to when it stopped is small, but much happened in this nterval Slow is the opposite, when the quantity in it is much, but what has been done is little. And for this reason, there is no quick and slow in rest, for all is equal to its own quantity, and neither much in a small quantity, or short in a large one. And this is why we speak of more and less time, but not of quicker or slower time. For an action and a motion can be quicker or slower, but the quantity in which the action is, is not quicker and slower, but more and less, like the time. Day and night, and month and year are not time or parts of time, but the former are light and dark, the latter the circuit of the moon and sun, while time is the quantity in which these are.He was critical of Aristotle's concept of

place

Place may refer to:

Geography

* Place (United States Census Bureau), defined as any concentration of population

** Census-designated place, a populated area lacking its own municipal government

* "Place", a type of street or road name

** O ...

as a surrounding surface, preferring to see it as the space which a thing occupies. He also rejected the existence of Aristotle's fifth element.

He emphasized the role of pneuma

''Pneuma'' () is an ancient Greek word for "breath", and in a religious context for " spirit" or "soul". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in regard to physiology, and is ...

('breath' or 'spirit') in the functioning of the soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest att ...

; soul-activities were explained by pneuma extending throughout the body from the 'ruling part' located in the head. All sensation is felt in the ruling-part of the soul, rather than in the extremities of the body; all sensation involves thought

In their most common sense, the terms thought and thinking refer to conscious cognitive processes that can happen independently of sensory stimulation. Their most paradigmatic forms are judging, reasoning, concept formation, problem solving, an ...

, and there is no thought not derived from sensation. He denied that the soul was immortal, and attacked the 'proofs' put forward by Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

in his ''Phaedo

''Phædo'' or ''Phaedo'' (; el, Φαίδων, ''Phaidōn'' ), also known to ancient readers as ''On The Soul'', is one of the best-known dialogues of Plato's middle period, along with the '' Republic'' and the ''Symposium.'' The philosophica ...

''.

Strato believed all matter consisted of tiny particles, but he rejected Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

' theory of empty space. In Strato's view, void does exist, but only in the empty spaces between imperfectly fitting particles; Space is always filled with some kind of matter. Such a theory permitted phenomena such as compression, and allowed the penetration of light

Light or visible light is electromagnetic radiation that can be perceived by the human eye. Visible light is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400–700 nanometres (nm), corresponding to frequencies of 750–420 t ...

and heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

through apparently solid bodies.

He seems to have denied the existence of any god outside of the material universe, and to have held that every particle of matter has a plastic and seminal power, but without sensation or intelligence; and that life, sensation, and intellect, are but forms, accidents, and affections of matter. Cicero took exception to this:

Nor does his pupil Strato, who is called theLike thenatural philosopher Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science. From the ancient wo ..., deserve to be listened to; he holds that all divine force is resident in nature, which contains, he says, the principles of birth, increase, and decay, but which lacks, as we could remind him, all sensation and form.

atomists

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms a ...

(Leucippus

Leucippus (; el, Λεύκιππος, ''Leúkippos''; fl. 5th century BCE) is a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who has been credited as the first philosopher to develop a theory of atomism.

Leucippus' reputation, even in antiquity, was obscured ...

and Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

) before him, Strato of Lampsacus was a materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

and believed that everything in the universe was composed of matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic part ...

and energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of ...

. Strato was one of the first philosophers to formulate a secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

worldview, in which God is merely the unconscious force of nature.

You deny that without God there can be anything: but here you yourself seem to go contrary to Strato of Lampsacus, who concedes to God a pardon from a great task. If the priests of God were on vacation, it is much more just that the Gods would also be on vacation; in fact he denies the need to appreciate the work of the Gods in order to construct the world. All the things that exist he teaches have been produced by nature; not hence, as he says, according to that philosophy which claims these things are made of rough and smooth corpuscles, indented and hooked, the void interfering; these, he upholds, are dreams of Democritus which are not to be taught but dreamt. Strato, in fact, investigating the individual parts of the world, teaches that all that which is or is produced, is or has been produced, by weight and motion. Thus he liberates God from a big job and me from fear.Strato endeavoured to replace the Aristotelian

teleology

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

by a purely physical explanation of phenomena, the underlying elements of which he found in heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is ...

and cold

Cold is the presence of low temperature, especially in the atmosphere. In common usage, cold is often a subjective perception. A lower bound to temperature is absolute zero, defined as 0.00K on the Kelvin scale, an absolute thermodynamic ...

, with especially heat as the active principle. Although Strato's view of the universe can be seen as secular, he may have accepted the existence of gods within the universe, in the context of ancient Greek religion

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has bee ...

; it is unlikely that he would have regarded himself as an atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

.

Geology

As quoted from Charles Lyell's ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830–1833. Ly ...

'':

Also following the reference ofStrabo Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called " Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could s ...passes on to the hypothesis of Strato, the natural philosopher, who had observed that the quantity of mud brought down by rivers into the Euxine was so great, that its bed must be gradually raised, while the rivers still continued to pour in an undiminished quantity of water. He therefore conceived that, originally, when the Euxine was an inland sea, its level had by this means become so much elevated that it burst its barrier near Byzantium, and formed a communication with the Propontis, and this partial drainage had already, he supposed, converted the left side into marshy ground, and that, at last, the whole would be choked up with soil. So, it was argued, the Mediterranean had once opened a passage for itself by the Columns of Hercules into the Atlantic, and perhaps the abundance of sea-shells in Africa, near the Temple ofJupiter Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but slightly less than one-thousand ...Ammon Ammon (Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in ..., might also be the deposit of some former inland sea, which had at length forced a passage and escaped.

Georgius Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Pawer or Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman Empire ...

Strato of Lampsacus, the successor of Theophrastus, wrote a book on the subject of metallic arts called ''De Machinis Metallicis''.

Modern influence

Strato's name meant little in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. However, in the 17th century, his name suddenly became famous due to the supposed similarities between his system and thepantheistic

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ...

views of Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, ...

. In his 1678 attack on atheism, Ralph Cudworth

Ralph Cudworth ( ; 1617 – 26 June 1688) was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian Hebraist, classicist, theologian and philosopher, and a leading figure among the Cambridge Platonists who became 11th Regius Professor of Hebrew ...

designated Strato's system as one of four types of atheism and in doing so, coined the term hylozoism to describe any system where primitive matter is endowed with a life force

Life force or lifeforce may refer to:

* Spirit (vital essence), in folk belief, the vital principle or animating force within all living things

* Vitality, ability to live or exist

* Vitalism, the belief in the existence of vital energy

** Energ ...

. These ideas reached Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 – 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. A Huguenot, Bayle fled to the Dutch Republic in 1681 because of religious persecution in France. He is best known for his '' Histori ...

, who adopted Strato and 'Stratonism' as key components of his own philosophy. In his ''Continuation des Pensées diverses'', published in 1705, Stratonism became the most important ancient equivalent of Spinozism

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

. For Bayle, Strato had made everything to follow a fixed order of necessity, with no innate good or bad in the universe; the universe was not regarded as a living thing with intelligence or intent, and there is no other divine power but nature. As the third head of the Peripatetic School in Greece, Strato also taught Aristarchus of Samos, whom went on to present the first known heliocentric model as an alternative hypothesis to the then-acknowledged model of geocentrism. The heliocentric model situated the Sun at the center of the universe, unlike geocentrism which placed the Earth at the center of the universe. This Aristarchus had a significant impact on philosophers and scientists during the Hellenistic era of philosophy and science, and also later scholars, namely Copernicus and Kepler.

List of works

The list of his works is given byDiogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sour ...

.Diogenes Laërtius, ''Lives of the Eminent Philosophers

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sourc ...

'', v. 59, 60.

* ''Of Kingship'', three books.

* ''Of Justice'', three books.

* ''Of the Good'', three books.

* ''Of the Gods'', three books.

* ''On First Principles'', three books.

* ''On Various Modes of Life''.

* ''Of Happiness''.

* ''On the Philosopher-King''.

* ''Of Courage''.

* ''On the Void''.

* ''On the Heaven''.

* ''On the Wind''.

* ''Of Human Nature''.

* ''On the Breeding of Animals''.

* ''Of Mixture''.

* ''Of Sleep''.

* ''Of Dreams''.

* ''Of Vision.''

* ''Of Sensation.''

* ''Of Pleasure.''

* ''On Colours.''

* ''Of Diseases.''

* ''Of the Crises in Diseases.''

* ''On Faculties.''

* ''On Mining Machinery.''

* ''Of Starvation and Dizziness.''

* ''On the Attributes Light and Heavy.''

* ''Of Enthusiasm or Ecstasy.''

* ''On Time.''

* ''On Growth and Nutrition.''

* ''On Animals the existence of which is questioned.''

* ''On Animals in Folk-lore or Fable.''

* ''Of Causes.''

* ''Solutions of Difficulties.''

* ''Introduction to Topics.''

* ''Of Accident.''

* ''Of Definition.''

* ''On difference of Degree.''

* ''Of Injustice.''

* ''Of the logically Prior and Posterior''.

* ''Of the Genus of the Prior''.

* ''Of the Property or Essential Attribute''.

* ''Of the Future''.

* ''Examinations of Discoveries'', in two books.

* ''Lecture-notes'', Diogenes adds that its authorship is disputed.

* Letters beginning "Strato to Arsinoë greeting."

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Strato Of Lampsacus 330s BC births 260s BC deaths 4th-century BC Greek people 4th-century BC philosophers 4th-century BC scholars 4th-century BC writers 3rd-century BC Greek people 3rd-century BC philosophers 3rd-century BC scholars 3rd-century BC writers Ancient Greek epistemologists Ancient Greek ethicists Ancient Greek metaphilosophers Ancient Greek metaphysicians Ancient Greek philosophers of mind Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greek political philosophers Atheist philosophers Hellenistic-era philosophers in Athens History of philosophy History of science Intellectual history Materialists Metaphysics writers Moral philosophers Natural philosophers Ontologists Peripatetic philosophers People from Lampsacus Philosophers of ethics and morality Philosophers of religion Philosophers of science Philosophers of time Philosophy of physics Philosophy writers Pre–17th-century atheists Secularists Writers about religion and science