Strabo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in

Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in

Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in  Strabo's life was characterized by extensive travels. He journeyed to

Strabo's life was characterized by extensive travels. He journeyed to  It is not known precisely when Strabo's ''Geography'' was written, though comments within the work itself place the finished version within the reign of Emperor

It is not known precisely when Strabo's ''Geography'' was written, though comments within the work itself place the finished version within the reign of Emperor

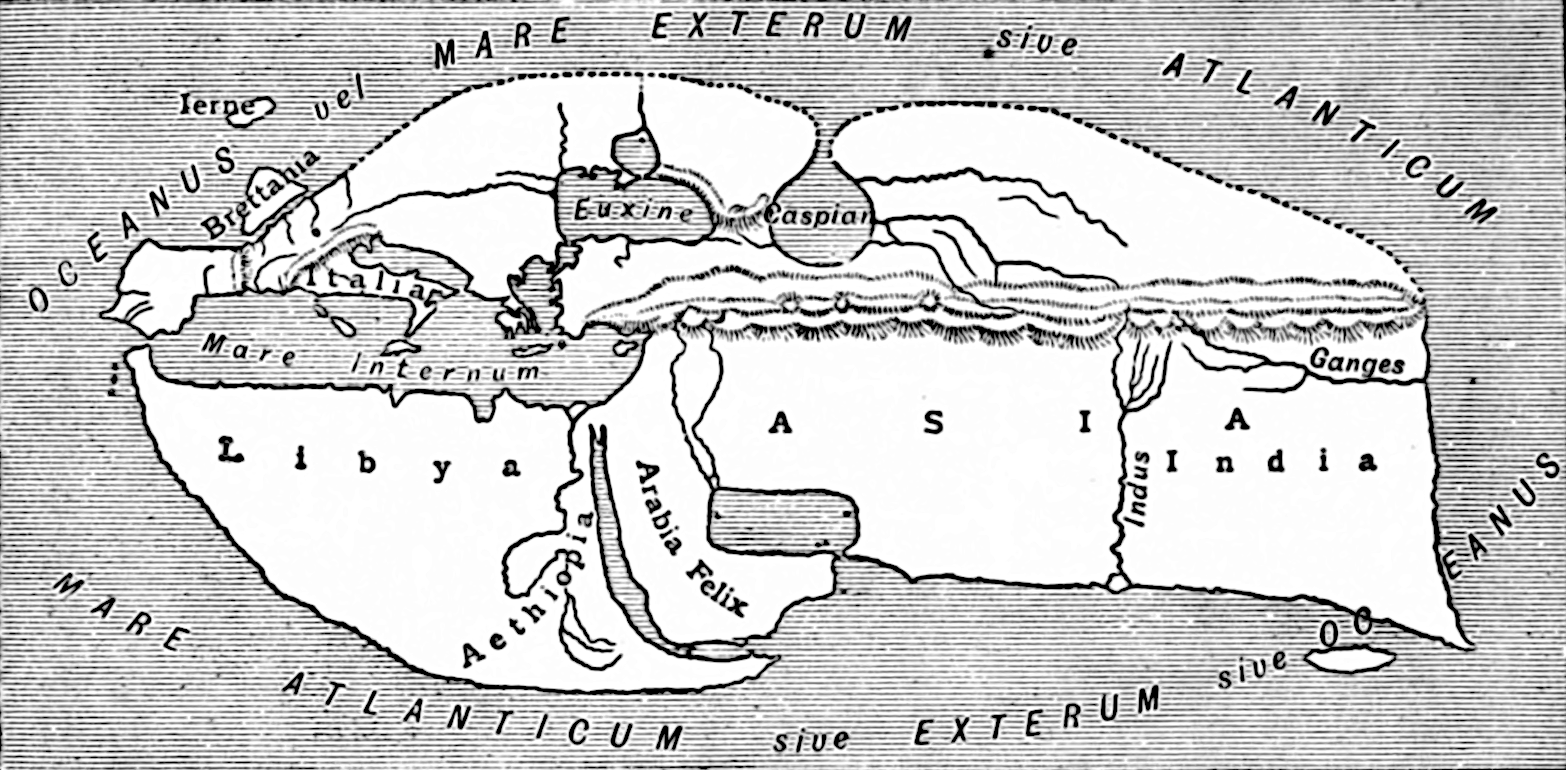

Strabo is best known for his work '' Geographica'' ("Geography"), which presented a descriptive history of people and places from different regions of the world known during his lifetime.

Strabo is best known for his work '' Geographica'' ("Geography"), which presented a descriptive history of people and places from different regions of the world known during his lifetime.

Although the ''Geographica'' was rarely utilized by contemporary writers, a multitude of copies survived throughout the

Although the ''Geographica'' was rarely utilized by contemporary writers, a multitude of copies survived throughout the

''Geography''

Works by Strabo at Perseus Digital Library

Biography of Strabo

* *

Map of the Toponyms in the Geography of Strabo

* {{Authority control 60s BC births 24 deaths 1st-century BC historians Ancient Greek geographers Roman-era geographers Roman-era Greek historians Ancient Pontic Greeks People from Amasya Roman Pontus Historians from Roman Anatolia 1st-century geographers 1st-century BC geographers

strabismus

Strabismus is a vision disorder in which the eyes do not properly align with each other when looking at an object. The eye that is focused on an object can alternate. The condition may be present occasionally or constantly. If present during a ...

) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

was called "Pompeius Strabo

Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo (c. 135 – 87 BC) was a Roman general and politician, who served as consul in 89 BC. He is often referred to in English as Pompey Strabo, to distinguish him from his son, the famous Pompey the Great, or from Strabo the g ...

". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see things at great distance as if they were nearby was also called "Strabo". (; el, Στράβων ''Strábōn''; 64 or 63 BC 24 AD) was a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

, philosopher, and historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

who lived in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

during the transitional period of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

into the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

.

Life

Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in

Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

(in present-day Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

) in around 64BC. His family had been involved in politics since at least the reign of Mithridates V. Strabo was related to Dorylaeus Dorylaeus or Dorylaüs (early 1st century BC), was a commander in the Kingdom of Pontus who served under Mithridates the Great. Dorylaeus reinforced Archelaus with eighty thousand fresh troops after the latter's loss at Battle of Chaeronea. Doryl ...

on his mother's side. Several other family members, including his paternal grandfather had served Mithridates VI during the Mithridatic Wars

The Mithridatic Wars were three conflicts fought by Rome against the Kingdom of Pontus and its allies between 88 BC and 63 BC. They are named after Mithridates VI, the King of Pontus who initiated the hostilities after annexing the Roman provi ...

. As the war drew to a close, Strabo's grandfather had turned several Pontic

Pontic, from the Greek ''pontos'' (, ), or "sea", may refer to:

The Black Sea Places

* The Pontic colonies, on its northern shores

* Pontus (region), a region on its southern shores

* The Pontic–Caspian steppe, steppelands stretching from no ...

fortresses over to the Romans. Strabo wrote that "great promises were made in exchange for these services", and as Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

culture endured in Amaseia even after Mithridates and Tigranes

Tigranes (, grc, Τιγράνης) is the Greek transliteration of the Old Iranian name ''*Tigrāna''. This was the name of a number of historical figures, primarily kings of Armenia.

The name of Tigranes, which was theophoric in nature, was u ...

were defeated, scholars have speculated about how the family's support for Rome might have affected their position in the local community, and whether they might have been granted Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: ''civitas'') was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, t ...

as a reward.

Strabo's life was characterized by extensive travels. He journeyed to

Strabo's life was characterized by extensive travels. He journeyed to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medit ...

and Kush

Kush or Cush may refer to:

Bible

* Cush (Bible), two people and one or more places in the Hebrew Bible

Places

* Kush (mountain), a mountain near Kalat, Pakistan Balochistan

* Kush (satrapy), a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire

* Hindu Kush, a ...

, as far west as coastal Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

and as far south as Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

in addition to his travels in Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

and the time he spent in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Travel throughout the Mediterranean and Near East, especially for scholarly purposes, was popular during this era and was facilitated by the relative peace enjoyed throughout the reign of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

(27 BC – AD 14). He moved to Rome in 44 BC, and stayed there, studying and writing, until at least 31 BC. In 29 BC, on his way to Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government refor ...

(where Augustus was at the time), he visited the island of Gyaros

Gyaros ( el, Γυάρος ), also locally known as Gioura ( el, Γιούρα), is an arid, unpopulated, and uninhabited Greek island in the northern Cyclades near the islands of Andros and Tinos, with an area of . It is a part of the municipality ...

in the Aegean Sea. Around 25 BC, he sailed up the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ...

until he reached Philae

; ar, فيلة; cop, ⲡⲓⲗⲁⲕ

, alternate_name =

, image = File:File, Asuán, Egipto, 2022-04-01, DD 93.jpg

, alt =

, caption = The temple of Isis from Philae at its current location on Agilkia Island in Lake Nasse ...

,Accompanied by prefect of Egypt Aelius Gallus, who had been sent on a military mission to Arabia. after which point there is little record of his travels until AD 17.

It is not known precisely when Strabo's ''Geography'' was written, though comments within the work itself place the finished version within the reign of Emperor

It is not known precisely when Strabo's ''Geography'' was written, though comments within the work itself place the finished version within the reign of Emperor Tiberius

Tiberius Julius Caesar Augustus (; 16 November 42 BC – 16 March AD 37) was the second Roman emperor. He reigned from AD 14 until 37, succeeding his stepfather, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Tiberius was born in Rome in 42 BC. His father ...

. Some place its first drafts around 7 BC, others around AD 17 or AD 18. The latest passage to which a date can be assigned is his reference to the death in AD 23 of Juba II, king of Maurousia ( Mauretania), who is said to have died "just recently". He probably worked on the ''Geography'' for many years and revised it steadily, but not always consistently. It is an encyclopaedic chronicle and consists of political, economic, social, cultural, geographic description covering almost all of Europe and the Mediterranean: British Isles, Iberian Peninsula, Gaul, Germania, the Alps, Italy, Greece, Northern Black Sea region, Anatolia, Middle East, Central Asia and North Africa. The ''Geography'' is the only extant work providing information about both Greek and Roman peoples and countries during the reign of Augustus.

On the presumption that "recently" means within a year, Strabo stopped writing that year or the next (AD 24), at which time he is thought to have died. He was influenced by Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, Hecataeus and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

. The first of Strabo's major works, ''Historical Sketches'' (''Historica hypomnemata''), written while he was in Rome (c. 20 BC), is nearly completely lost. Meant to cover the history of the known world from the conquest of Greece by the Romans, Strabo quotes it himself and other classical authors mention that it existed, although the only surviving document is a fragment of papyrus now in the possession of the University of Milan

The University of Milan ( it, Università degli Studi di Milano; la, Universitas Studiorum Mediolanensis), known colloquially as UniMi or Statale, is a public research university in Milan, Italy. It is one of the largest universities in Europe ...

(renumbered apyrusnbsp;46).

Education

Strabo studied under several prominent teachers of various specialities throughout his early lifeHe mentions all or most of his teachers as prominent citizens of their own respective cities. at different stops during his Mediterranean travels. The first chapter of his education took place in Nysa (modern Sultanhisar, Turkey) under the master of rhetoric Aristodemus, who had formerly taught the sons of the Roman general who had taken over Pontus.This also highlights the international trend of the era that Greek intellectuals would often instruct the Roman elite. Aristodemus was the head of two schools of rhetoric and grammar, one in Nysa and one inRhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

. The school in Nysa possessed a distinct intellectual curiosity in Homeric literature and the interpretation of the ancient Greek epics. Strabo was an admirer of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's poetry, perhaps as a consequence of his time spent in Nysa with Aristodemus.Aristodemus was also the grandson of the famous Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, Ποσειδώνιος , "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (ὁ Ἀπαμεύς) or "of Rhodes" (ὁ Ῥόδιος) (), was a Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher nativ ...

, whose influence is manifest in Strabo's ''Geography''.

At around the age of 21, Strabo moved to Rome, where he studied philosophy with the Peripatetic Xenarchus, a highly respected tutor in Augustus's court. Despite Xenarchus's Aristotelian leanings, Strabo later gives evidence to have formed his own Stoic

Stoic may refer to:

* An adherent of Stoicism; one whose moral quality is associated with that school of philosophy

* STOIC, a programming language

* ''Stoic'' (film), a 2009 film by Uwe Boll

* ''Stoic'' (mixtape), a 2012 mixtape by rapper T-Pain

* ...

inclinations.Largely due to his future teacher Athenodorus, tutor of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

. In Rome, he also learned grammar under the rich and famous scholar Tyrannion of Amisus Tyrannion ( grc-gre, Τυραννίων, ''Tyranníōn''; la, Tyrannio; 1st century BC) was a Greek grammarian brought to Rome as a war captive and slave.

He is also known as Tyrannion the Elder, in order to distinguish him from his pupil who ...

.Thus completing his traditional Greek aristocratic education in rhetoric, grammar, and philosophy. Tyrannion was known to have befriended Cicero and taught his nephew, Quintus. Although Tyrannion was also a Peripatetic, he was more relevantly a respected authority on geography, a fact of some significance considering Strabo's future contributions to the field.

The final noteworthy mentor to Strabo was Athenodorus Cananites

Athenodorus Cananites (Ancient Greek, Greek: , ''Athenodoros Kananites''; c. 74 BC7 AD) was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher.

Life

Athenodorus was born in Canana, near Tarsus (city), Tarsus (in modern-day Turkey); his father was Sandon (philosophe ...

, a philosopher who had spent his life since 44 BC in Rome forging relationships with the Roman elite. Athenodorus passed onto Strabo his philosophy, his knowledge and his contacts. Unlike the Aristotelian Xenarchus and Tyrannion who preceded him in teaching Strabo, Athenodorus was a Stoic and almost certainly the source of Strabo's diversion from the philosophy of his former mentors. Moreover, from his own first-hand experience, Athenodorus provided Strabo with information about regions of the empire which Strabo would not otherwise have known about.

''Geographica''

Although the ''Geographica'' was rarely utilized by contemporary writers, a multitude of copies survived throughout the

Although the ''Geographica'' was rarely utilized by contemporary writers, a multitude of copies survived throughout the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. It first appeared in Western Europe in Rome as a Latin translation issued around 1469. The first Greek edition was published in 1516 in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

. Isaac Casaubon

Isaac Casaubon (; ; 18 February 1559 – 1 July 1614) was a classical scholar and philologist, first in France and then later in England.

His son Méric Casaubon was also a classical scholar.

Life Early life

He was born in Geneva to two Fr ...

, classical scholar and editor of Greek texts, provided the first critical edition in 1587.

Although Strabo cited the classical Greek astronomers Eratosthenes and Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

, acknowledging their astronomical and mathematical efforts covering geography, he claimed that a descriptive approach was more practical, such that his works were designed for statesmen who were more anthropologically than numerically concerned with the character of countries and regions.

As such, ''Geographica'' provides a valuable source of information on the ancient world of his day, especially when this information is corroborated by other sources. He travelled extensively, as he says: "Westward I have journeyed to the parts of Etruria opposite Sardinia; towards the south from the Euxine to the borders of Ethiopia; and perhaps not one of those who have written geographies has visited more places than I have between those limits."

It is not known when he wrote ''Geographica'', but he spent much time in the famous library in Alexandria taking notes from "the works of his predecessors". A first edition was published in 7 BC and a final edition no later than 23 AD, in what may have been the last year of Strabo's life. It took some time for ''Geographica'' to be recognized by scholars and to become a standard.

Alexandria itself features extensively in the last book of ''Geographica'', which describes it as a thriving port city with a highly developed local economy. Strabo notes the city's many beautiful public parks, and its network of streets wide enough for chariots and horsemen. "Two of these are exceeding broad, over a plethron in breadth, and cut one another at right angles ... All the buildings are connected one with another, and these also with what are beyond it."

Lawrence Kim observes that Strabo is "... pro-Roman throughout the Geography. But while he acknowledges and even praises Roman ascendancy in the political and military sphere, he also makes a significant effort to establish Greek primacy over Rome in other contexts."

In Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

, Strabo was the first to connect the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

– Danouios and the Istros – with the change of names occurring at "the cataracts," the modern Iron Gates on the Romanian/Serbian border.

In India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, a country he never visited, Strabo described small flying reptiles that were long with a snake-like body and bat-like wings (this description matches the Indian flying lizard ''Draco dussumieri''), winged scorpions, and other mythical creatures along with those that were actually factual. Other historians, such as Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ph ...

, and Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly ...

, mentioned similar creatures.

Geology

Charles Lyell, in his ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830–1833. Ly ...

'', wrote of Strabo:

Fossil formation

Strabo commented on fossil formation mentioningNummulite

A nummulite is a large lenticular fossil, characterized by its numerous coils, subdivided by septa into chambers. They are the shells of the fossil and present-day marine protozoan ''Nummulites'', a type of foraminiferan. Nummulites commonly vary ...

(quoted from Celâl Şengör):One extraordinary thing which I saw at the pyramids must not be omitted. Heaps of stones from the quarries lie in front of the pyramids. Among these are found pieces which in shape and size resemble lentils. Some contain substances like grains half peeled. These, it is said, are the remnants of the workmen's food converted into stone; which is not probable. For at home in our country (Amaseia), there is a long hill in a plain, which abounds with pebbles of a porous stone, resembling lentils. The pebbles of the sea-shore and of rivers suggest somewhat of the same difficulty especting their origin some explanation may indeed be found in the motion o which these are subjectin flowing waters, but the investigation of the above fact presents more difficulty. I have said elsewhere, that in sight of the pyramids, on the other side in Arabia, and near the stone quarries from which they are built, is a very rocky mountain, called the Trojan mountain; beneath it there are caves, and near the caves and the river a village called Troy, an ancient settlement of the captive Trojans who had accompanied Menelaus and settled there.

Volcanism

Strabo commented onvolcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

( effusive eruption) which he observed at Katakekaumene (modern Kula, Western Turkey). Strabo's observations predated Pliny the Younger who witnessed the eruption of Mount Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of ...

on 24 August AD 79 in Pompeii:…There are no trees here, but only the vineyards where they produce the Katakekaumene wines which are by no means inferior from any of the wines famous for their quality. The soil is covered with ashes, and black in colour as if the mountainous and rocky country was made up of fires. Some assume that these ashes were the result of thunderbolts and subterranean explosions, and do not doubt that the legendary story ofTyphon Typhon (; grc, Τυφῶν, Typhôn, ), also Typhoeus (; grc, Τυφωεύς, Typhōeús, label=none), Typhaon ( grc, Τυφάων, Typháōn, label=none) or Typhos ( grc, Τυφώς, Typhṓs, label=none), was a monstrous serpentine giant an ...takes place in this region. Ksanthos adds that the king of this region was a man called Arimus. However, it is not reasonable to accept that the whole country was burned down at a time as a result of such an event rather than as a result of a fire bursting from underground whose source has now died out. Three pits are called "Physas" and separated by forty stadia from each other. Above these pits, there are hills formed by the hot masses burst out from the ground as estimated by a logical reasoning. Such type of soil is very convenient forviniculture Viticulture (from the Latin word for ''vine'') or winegrowing (wine growing) is the cultivation and harvesting of grapes. It is a branch of the science of horticulture. While the native territory of ''Vitis vinifera'', the common grape vine, ra ..., just like the Katanasoil which is covered with ashes and where the best wines are still produced abundantly. Some writers concluded by looking at these places that there is a good reason for calling Dionysus by the name ("Phrygenes").

Editions

* * * *Jones, H. L., transl. (1917). ''The Geography of Strabo''. London: Heinemann.Jones, H. L., transl. (1917). ''The Geography of Strabo''. London: Heinemann. In eight volumes: Vol 1; Vol 2; Vol 3; Vol 4; Vol 5; Vol 6; Vol 7; Vol 8. *''Strabo's Geography'' in three volumes as translated by H.C. Hamilton and W. Falconer, ed. by H.G. Bohn, 1854–1857References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * *Further reading

* Bowersock, Glen W. 2005. "La patria di Strabone." In ''Strabone e l’Asia Minore.'' Edited by Anna Maria Biraschi and Giovanni Salmieri, 15–23. Studi di Storia e di Storiografia. Göttingen, Germany: Edizione Scientifiche Italiane. * Braund, David. 2006. "Greek Geography and Roman Empire: The Transformation of Tradition in Strabo’s Euxine." In ''Strabo’s Cultural Geography: The Making of a Kolossourgia.'' Edited by Daniela Dueck, Hugh Lindsay, and Sarah Pothecary, 216–234. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. * Clarke, Katherine. 1997. "In Search of the Author of Strabo’s Geography." ''Journal of Roman Studies'' 87:92–110. * Diller, Aubrey. 1975. ''The Textual Tradition of Strabo’s Geography.'' Amsterdam: Hakkert. * Irby, Georgia L. 2012. "Mapping the World: Greek Initiatives from Homer to Eratosthenes." In ''Ancient Perspectives: Maps and their Place in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome.'' Edited by Richard J. A. Talbert, 81–107. Kenneth Nebenzahl Jr. Lectures in the History of Cartography. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. * Kim, Lawrence. 2007. "The Portrait of Homer in Strabo’s Geography." ''Classical Philology'' 102.4: 363–388. * Kuin, Inger N.I. 2017. "Rewriting Family History: Strabo and the Mithridatic Wars." ''Phoenix'' 71.1-2: 102–118. * Pfuntner, Laura. 2017. "Death and Birth in the Urban Landscape: Strabo on Troy and Rome." ''Classical Antiquity'' 36.1: 33–51. * Pothecary, Sarah. 1999. "Strabo the Geographer: His Name and its Meaning." ''Mnemosyne'', 4th ser. 52.6: 691–704 * Richards, G. C. 1941. "Strabo: The Anatolian who Failed of Roman Recognition." ''Greece and Rome'' 10.29: 79–90.External links

* * *''Geography''

Works by Strabo at Perseus Digital Library

Biography of Strabo

* *

Map of the Toponyms in the Geography of Strabo

* {{Authority control 60s BC births 24 deaths 1st-century BC historians Ancient Greek geographers Roman-era geographers Roman-era Greek historians Ancient Pontic Greeks People from Amasya Roman Pontus Historians from Roman Anatolia 1st-century geographers 1st-century BC geographers