Stoic logic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stoic logic is the system of

Aristotle's

Aristotle's

:It is day;

:Therefore it is light. It has a non-simple assertible for the first premiss ("If it is day, it is light") and a simple assertible for second premiss ("It is day"). The second premiss doesn't ''always'' have to be simple but it will have fewer components than the first. In more formal terms this type of syllogism is: :If p, then q;

:p;

:Therefore q. As with Aristotle's term logic, Stoic logic also uses variables, but the values of the variables are propositions not terms. Chrysippus listed five basic argument forms, which he regarded as true beyond dispute. These five indemonstrable arguments are made up of conditional, disjunction, and negation conjunction connectives, and all other arguments are reducible to these five indemonstrable arguments. There can be many variations of these five indemonstrable arguments. For example the assertibles in the premises can be more complex, and the following syllogism is a valid example of the second indemonstrable (''modus tollens''): :if both p and q, then r;

:not r;

:therefore not: both p and q Similarly one can incorporate negation into these arguments. A valid example of the fourth indemonstrable (''modus tollendo ponens'' or disjunctive syllogism) is: :either ot por q;

:not ot p

:therefore q which, incorporating the principle of

:p;

:therefore q

:not r;

:but also p;

:Therefore not q This can be reduced to two separate indemonstrable arguments of the second and third type: :if both p and q, then r;

:not r;

:therefore not: both p and q :not: both p and q

:p;

:therefore not q The Stoics stated that complex syllogisms could be reduced to the indemonstrables through the use of four ground rules or ''themata''. Of these four ''themata'', only two have survived. One, the so-called first ''thema'', was a rule of antilogism: The other, the third ''thema'', was a

b. "Stoic modal logic is not a logic of modal propositions (e.g., propositions of the type 'It is possible that it is day' ...) ... instead, their modal theory was about non-modalized propositions like 'It is day', insofar as they are possible, necessary, and so forth."

c. Most of these argument forms had already been discussed by Theophrastus, but: "It is plain that even if Theophrastus discussed (1)–(5), he did not anticipate Chrysippus' achievement. ... his Aristotelian approach to the study and organization of argument-forms would have given his discussion of mixed hypothetical syllogisms an utterly unStoical aspect."

d. These

e. For a brief summary of these ''themata'' see Susanne Bobzien's

Ancient Logic

' article for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. For a detailed (and technical) analysis of the ''themata'', including a tentative reconstruction of the two lost ones, see

''Stoic Logic''

(1953) by Benson Mates (1919–2009) {{Stoicism Classical logic History of logic Philosophical logic Propositional calculus

propositional logic

Propositional calculus is a branch of logic. It is also called propositional logic, statement logic, sentential calculus, sentential logic, or sometimes zeroth-order logic. It deals with propositions (which can be true or false) and relations b ...

developed by the Stoic philosophers in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cu ...

.

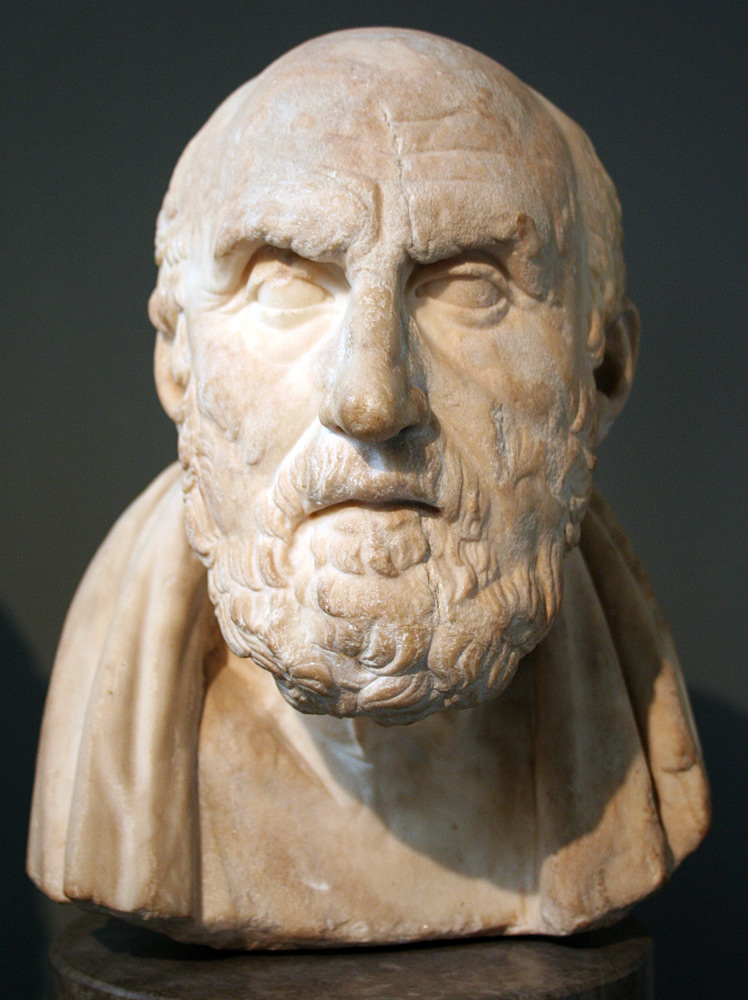

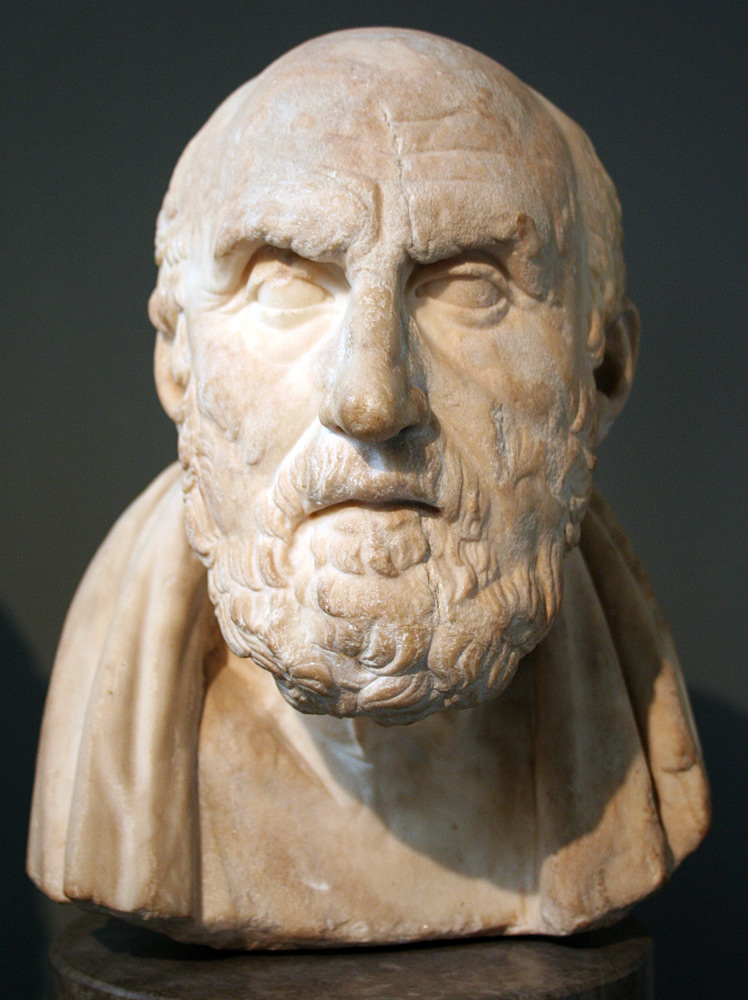

It was one of the two great systems of logic in the classical world. It was largely built and shaped by Chrysippus

Chrysippus of Soli (; grc-gre, Χρύσιππος ὁ Σολεύς, ; ) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When C ...

, the third head of the Stoic school in the 3rd-century BCE. Chrysippus's logic differed from Aristotle's term logic

In philosophy, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, ...

because it was based on the analysis of proposition

In logic and linguistics, a proposition is the meaning of a declarative sentence. In philosophy, " meaning" is understood to be a non-linguistic entity which is shared by all sentences with the same meaning. Equivalently, a proposition is the no ...

s rather than terms. The smallest unit in Stoic logic is an ''assertible'' (the Stoic equivalent of a proposition) which is the content of a statement such as "it is day". Assertibles have a truth-value such that they are only true or false depending on when it was expressed (e.g. the assertible "it is night" will only be true if it is true that it is night). In contrast, Aristotelian propositions strongly affirm or deny a predicate of a subject and seek to have its truth validated or falsified independent of context. Compound assertibles can be built up from simple ones through the use of logical connectives

In logic, a logical connective (also called a logical operator, sentential connective, or sentential operator) is a logical constant. They can be used to connect logical formulas. For instance in the syntax of propositional logic, the binar ...

. The resulting syllogistic was grounded on five basic indemonstrable arguments to which all other syllogisms were claimed to be reducible.

Towards the end of antiquity Stoic logic was neglected in favour of Aristotle's logic, and as a result the Stoic writings on logic did not survive, and the only accounts of it were incomplete reports by other writers. Knowledge about Stoic logic as a system was lost until the 20th century, when logicians familiar with the modern propositional calculus

Propositional calculus is a branch of logic. It is also called propositional logic, statement logic, sentential calculus, sentential logic, or sometimes zeroth-order logic. It deals with propositions (which can be true or false) and relations b ...

reappraised the ancient accounts of it.

Background

Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting tha ...

is a school of philosophy which developed in the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

around a generation after the time of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Logic (''logike'') was the part of philosophy which examined reason (''logos''). To achieve a happy life—a life worth living—requires logical thought. The Stoics held that an understanding of ethics was impossible without logic. In the words of Inwood, the Stoics believed that:

Aristotle's

Aristotle's term logic

In philosophy, term logic, also known as traditional logic, syllogistic logic or Aristotelian logic, is a loose name for an approach to formal logic that began with Aristotle and was developed further in ancient history mostly by his followers, ...

can be viewed as a logic of classification. It makes use of four logical terms "all", "some", "is/are", and "is/are not" and to that extent is fairly static. The Stoics needed a logic that examines choice and consequence. The Stoics therefore developed a logic of proposition

In logic and linguistics, a proposition is the meaning of a declarative sentence. In philosophy, " meaning" is understood to be a non-linguistic entity which is shared by all sentences with the same meaning. Equivalently, a proposition is the no ...

s which uses connectives such as "if ... then", "either ... or", and "not both". Such connectives are part of everyday reasoning. Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

in the Dialogues of Plato often asks a fellow citizen ''if'' they believe a certain thing; when they agree, Socrates then proceeds to show how the consequences are logically false or absurd, inferring that the original belief must be wrong. Similar attempts at forensic reasoning must have been used in the law-courts, and they are a fundamental part of Greek mathematics. Aristotle himself was familiar with propositions, and his pupils Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routle ...

and Eudemus had examined hypothetical syllogisms, but there was no attempt by the Peripatetic school

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BC), and ''peripatetic'' is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

The school dates from around 335 BC when Aristo ...

to develop these ideas into a system of logic.

The Stoic tradition of logic originated in the 4th-century BCE in a different school of philosophy known as the Megarian school. It was two dialecticians of this school, Diodorus Cronus

Diodorus Cronus ( el, Διόδωρος Κρόνος; died c. 284 BC) was a Greek philosopher and dialectician connected to the Megarian school. He was most notable for logic innovations, including his master argument formulated in response to A ...

and his pupil Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; grc, Φίλων, Phílōn; he, יְדִידְיָה, Yəḏīḏyāh (Jedediah); ), also called Philo Judaeus, was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

Philo's de ...

, who developed their own theories of modalities and of conditional propositions. The founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium (; grc-x-koine, Ζήνων ὁ Κιτιεύς, ; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium (, ), Cyprus. Zeno was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 B ...

, studied under the Megarians and he was said to have been a fellow pupil with Philo. However, the outstanding figure in the development of Stoic logic was Chrysippus of Soli (c. 279 – c. 206 BCE), the third head of the Stoic school. Chrysippus shaped much of Stoic logic as we know it creating a system of propositional logic. As a logician Chrysippus is sometimes said to rival Aristotle in stature. The logical writings by Chrysippus are, however, almost entirely lost, instead his system has to be reconstructed from the partial and incomplete accounts preserved in the works of later authors such as Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman Pyrrhonism, and ...

, Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sour ...

, and Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be o ...

.

Propositions

To the Stoics, logic was a wide field of knowledge which included the study oflanguage

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

, grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraints, a field that includes doma ...

, rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

and epistemology

Epistemology (; ), or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

Epi ...

. However, all of these fields were interrelated, and the Stoics developed their logic (or "dialectic") within the context of their theory of language and epistemology.

Assertibles

The Stoics held that any meaningful utterance will involve three items: the sounds uttered; the thing which is referred to or described by the utterance; and an incorporeal item—the '' lektón'' (sayable)—that which is conveyed in the language. The ''lekton'' is not a statement but the content of a statement, and it corresponds to a complete utterance. A can be something such as a question or a command, but Stoic logic operates on those which are called "assertibles" (), described as a proposition which is either true or false and which affirms or denies. Examples of assertibles include "it is night", "it is raining this afternoon", and "no one is walking." The assertibles are truth-bearers. They can never be true and false at the same time (law of noncontradiction

In logic, the law of non-contradiction (LNC) (also known as the law of contradiction, principle of non-contradiction (PNC), or the principle of contradiction) states that contradictory propositions cannot both be true in the same sense at the s ...

) and they must be ''at least'' true or false ( law of excluded middle). The Stoics catalogued these simple assertibles according to whether they are affirmative or negative, and whether they are definite or indefinite (or both). The assertibles are much like modern proposition

In logic and linguistics, a proposition is the meaning of a declarative sentence. In philosophy, " meaning" is understood to be a non-linguistic entity which is shared by all sentences with the same meaning. Equivalently, a proposition is the no ...

s, however their truth value can change depending on ''when'' they are asserted. Thus an assertible such as "it is night" will only be true when it is night and not when it is day.

Compound assertibles

Simple assertibles can be connected to each other to form compound or non-simple assertibles. This is achieved through the use oflogical connectives

In logic, a logical connective (also called a logical operator, sentential connective, or sentential operator) is a logical constant. They can be used to connect logical formulas. For instance in the syntax of propositional logic, the binar ...

. Chrysippus seems to have been responsible for introducing the three main types of connectives: the conditional

Conditional (if then) may refer to:

*Causal conditional, if X then Y, where X is a cause of Y

*Conditional probability, the probability of an event A given that another event B has occurred

*Conditional proof, in logic: a proof that asserts a co ...

(if), conjunctive

The subjunctive (also known as conjunctive in some languages) is a grammatical mood, a feature of the utterance that indicates the speaker's attitude towards it. Subjunctive forms of verbs are typically used to express various states of unreality ...

(and), and disjunctive (or). A typical conditional takes the form of "if p then q"; whereas a conjunction takes the form of "both p and q"; and a disjunction takes the form of "either p or q". The or they used is exclusive, unlike the inclusive or generally used in modern formal logic. These connectives are combined with the use of not for negation. Thus the conditional can take the following four forms:

:If p, then q , If not p, then q , If p, then not q , If not p, then not q

Later Stoics added more connectives: the pseudo-conditional took the form of "since p then q"; and the causal assertible took the form of "because p then q". There was also a comparative (or dissertive): "more/less (likely) p than q".

Modality

Assertibles can also be distinguished by their modal properties—whether they are possible, impossible, necessary, or non-necessary. In this the Stoics were building on an earlier Megarian debate initiated by Diodorus Cronus. Diodorus had defined ''possibility'' in a way which seemed to adopt a form offatalism

Fatalism is a family of related philosophical doctrines that stress the subjugation of all events or actions to fate or destiny, and is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are t ...

. Diodorus defined ''possible'' as "that which either is or will be true". Thus there are no possibilities that are forever unrealised, whatever is possible is or one day will be true. His pupil Philo, rejecting this, defined ''possible'' as "that which is capable of being true by the proposition's own nature", thus a statement like "this piece of wood can burn" is ''possible'', even if it spent its entire existence on the bottom of the ocean. Chrysippus, on the other hand, was a causal determinist: he thought that true causes inevitably give rise to their effects and that all things arise in this way. But he was not a logical determinist or fatalist: he wanted to distinguish between possible and necessary truths. Thus he took a middle position between Diodorus and Philo, combining elements of both their modal systems. Chrysippus's set of Stoic modal definitions was as follows:

Syllogistic

Arguments

In Stoic logic, anargument form

In logic, logical form of a Statement (logic), statement is a precisely-specified Semantics, semantic version of that statement in a formal system. Informally, the logical form attempts to formalize a possibly Syntactic ambiguity, ambiguous sta ...

contains two (or more) premisses related to one another as cause and effect. A typical Stoic syllogism

A syllogism ( grc-gre, συλλογισμός, ''syllogismos'', 'conclusion, inference') is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be tru ...

is:

:If it is day, it is light;:It is day;

:Therefore it is light. It has a non-simple assertible for the first premiss ("If it is day, it is light") and a simple assertible for second premiss ("It is day"). The second premiss doesn't ''always'' have to be simple but it will have fewer components than the first. In more formal terms this type of syllogism is: :If p, then q;

:p;

:Therefore q. As with Aristotle's term logic, Stoic logic also uses variables, but the values of the variables are propositions not terms. Chrysippus listed five basic argument forms, which he regarded as true beyond dispute. These five indemonstrable arguments are made up of conditional, disjunction, and negation conjunction connectives, and all other arguments are reducible to these five indemonstrable arguments. There can be many variations of these five indemonstrable arguments. For example the assertibles in the premises can be more complex, and the following syllogism is a valid example of the second indemonstrable (''modus tollens''): :if both p and q, then r;

:not r;

:therefore not: both p and q Similarly one can incorporate negation into these arguments. A valid example of the fourth indemonstrable (''modus tollendo ponens'' or disjunctive syllogism) is: :either ot por q;

:not ot p

:therefore q which, incorporating the principle of

double negation

In propositional logic, double negation is the theorem that states that "If a statement is true, then it is not the case that the statement is not true." This is expressed by saying that a proposition ''A'' is logically equivalent to ''not ( ...

, is equivalent to:

:either ot por q;:p;

:therefore q

Analysis

Many arguments are not in the form of the five indemonstrables, and the task is to show how they can be reduced to one of the five types. A simple example of Stoic reduction is reported bySextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and Roman Pyrrhonism, and ...

:

:if both p and q, then r;:not r;

:but also p;

:Therefore not q This can be reduced to two separate indemonstrable arguments of the second and third type: :if both p and q, then r;

:not r;

:therefore not: both p and q :not: both p and q

:p;

:therefore not q The Stoics stated that complex syllogisms could be reduced to the indemonstrables through the use of four ground rules or ''themata''. Of these four ''themata'', only two have survived. One, the so-called first ''thema'', was a rule of antilogism: The other, the third ''thema'', was a

cut rule

In mathematical logic, the cut rule is an inference rule of sequent calculus. It is a generalisation of the classical modus ponens inference rule. Its meaning is that, if a formula ''A'' appears as a conclusion in one proof and a hypothesis in ano ...

by which chain syllogisms could be reduced to simple syllogisms. The importance of these rules is not altogether clear. In the 2nd-century BCE Antipater of Tarsus is said to have introduced a simpler method involving the use of fewer ''themata'', although few details survive concerning this. In any case, the ''themata'' cannot have been a necessary part of every analysis.

Paradoxes

Next to describing inferences which are valid, another subject which engaged the Stoics was the enumeration and refutation of false arguments, and in particular ofparadox

A paradox is a logically self-contradictory statement or a statement that runs contrary to one's expectation. It is a statement that, despite apparently valid reasoning from true premises, leads to a seemingly self-contradictory or a logically u ...

es. Part of a Stoic's logical training was to prepare the philosopher for paradoxes and help find solutions. A false argument could be one with a false premiss or which is formally incorrect, however paradoxes represented a challenge to the basic logical notions of the Stoics such as truth or falsehood. One famous paradox, known as '' The Liar'', asked "A man says he is lying; is what he says true or false?"—if the man says something true then it seems he is lying, but if he is lying then he is not saying something true, and so on. Chrysippus is known to have written several books on this paradox, although it is not known what solution he offered for it. Another paradox known as the '' Sorites'' or "Heap" asked "How many grains of wheat do you need before you get a heap?" It was said to challenge the idea of true or false by offering up the possibility of vagueness. The response of Chrysippus however was: "That doesn't harm me, for like a skilled driver I shall restrain my horses before I reach the edge ... In like manner I restrain myself in advance and stop replying to sophistical questions."

Stoic practice

Training in logic included a mastery of logical puzzles, the study of paradoxes, and the dissection of arguments. However, it was not an end in itself, but rather its purpose was for the Stoics to cultivate their rational powers. Stoic logic was thus a method of self-discovery. Its aim was to enable ethical reflection, permit secure and confident arguing, and lead the pupil to truth. The end result would be thought that is consistent, clear and precise, and which exposes confusion, murkiness and inconsistency.Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal sour ...

gives a list of dialectical virtues, which were probably invented by Chrysippus: citing Diogenes Laërtius, vii. 46f.

Later reception

For around five hundred years Stoic logic was one of the two great systems of logic. The logic of Chrysippus was discussed alongside that of Aristotle, and it may well have been more prominent since Stoicism was the dominant philosophical school. From a modern perspective Aristotle's term logic and the Stoic logic of propositions appear complementary, but they were sometimes regarded as rival systems. In late antiquity the Stoic school fell into decline, and the last pagan philosophical school, theNeoplatonists

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

, adopted Aristotle's logic for their own. Only elements of Stoic logic made their way into the logical writings of later commentators such as Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the t ...

, transmitting confused parts of Stoic logic to the Middle Ages. Propositional logic was redeveloped by Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard (; french: link=no, Pierre Abélard; la, Petrus Abaelardus or ''Abailardus''; 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, leading logician, theologian, poet, composer and musician. This source has a detailed des ...

in the 12th-century, but by the mid-15th-century the only logic which was being studied was a simplified version of Aristotle's. In the 18th-century Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

could pronounce that "since Aristotle ... logic has not been able to advance a single step, and is thus to all appearance a closed and complete body of doctrine." To 19th-century historians, who believed that Hellenistic philosophy

Hellenistic philosophy is a time-frame for Western philosophy and Ancient Greek philosophy corresponding to the Hellenistic period. It is purely external and encompasses disparate intellectual content. There is no single philosophical school or c ...

represented a decline from that of Plato and Aristotle, Stoic logic could only be seen with contempt. Carl Prantl

Karl Anton Eugen Prantl (10 September 1849 – 24 February 1893), also known as Carl Anton Eugen Prantl, was a German botanist.

Prantl was born in Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria, and studied in Munich. In 1870 he graduated with the dissertation ...

thought that Stoic logic was "dullness, triviality, and scholastic quibbling" and he welcomed the fact that the works of Chrysippus were no longer extant. Eduard Zeller

Eduard Gottlob Zeller (; 22 January 1814, Kleinbottwar19 March 1908, Stuttgart) was a German philosopher and Protestant theologian of the Tübingen School of theology. He was well known for his writings on Ancient Greek philosophy, especially ...

remarked that "the whole contribution of the Stoics to the field of logic consists in their having clothed the logic of the Peripatetics with a new terminology."

Modern logic begins in the middle of the 19th-century with the work of George Boole

George Boole (; 2 November 1815 – 8 December 1864) was a largely self-taught English mathematician, philosopher, and logician, most of whose short career was spent as the first professor of mathematics at Queen's College, Cork in ...

and Augustus de Morgan, but Stoic logic was only rediscovered in the 20th-century. The first person to reappraise their ideas was the Polish logician Jan Łukasiewicz

Jan Łukasiewicz (; 21 December 1878 – 13 February 1956) was a Polish logician and philosopher who is best known for Polish notation and Łukasiewicz logic His work centred on philosophical logic, mathematical logic and history of logic. ...

from the 1920s onwards. He was followed by Benson Mates. Stoic concepts often differ from modern ones, but nevertheless there are many close parallels between Stoic and 20th-century theories.

Notes

a. The minimum requirement for a conditional is that the consequent follows from the antecedent. The pseudo-conditional adds that the antecedent must also be true. The causal assertible adds an asymmetry rule such that if p is the cause/reason for q, then q cannot be the cause/reason for p.b. "Stoic modal logic is not a logic of modal propositions (e.g., propositions of the type 'It is possible that it is day' ...) ... instead, their modal theory was about non-modalized propositions like 'It is day', insofar as they are possible, necessary, and so forth."

c. Most of these argument forms had already been discussed by Theophrastus, but: "It is plain that even if Theophrastus discussed (1)–(5), he did not anticipate Chrysippus' achievement. ... his Aristotelian approach to the study and organization of argument-forms would have given his discussion of mixed hypothetical syllogisms an utterly unStoical aspect."

d. These

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

names date from the Middle Ages. e. For a brief summary of these ''themata'' see Susanne Bobzien's

Ancient Logic

' article for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. For a detailed (and technical) analysis of the ''themata'', including a tentative reconstruction of the two lost ones, see

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

*''Stoic Logic''

(1953) by Benson Mates (1919–2009) {{Stoicism Classical logic History of logic Philosophical logic Propositional calculus

Logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from prem ...