Steinbeck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

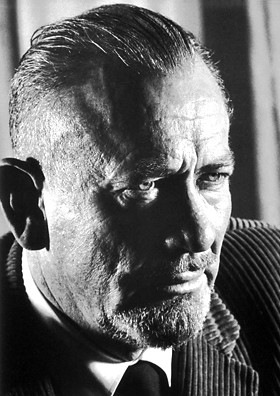

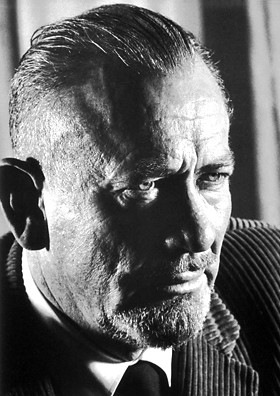

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the

Steinbeck graduated from Salinas High School in 1919 and went on to study English literature at

Steinbeck graduated from Salinas High School in 1919 and went on to study English literature at

(Winners 1917–1947). The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved January 28, 2012. and was adapted as a film directed by

''Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell''

, Four Walls Eight Windows, 2004. Steinbeck's close relations with Ricketts ended in 1941 when Steinbeck moved away from Pacific Grove and divorced his wife Carol. Ricketts' biographer Eric Enno Tamm opined that, except for '' East of Eden'' (1952), Steinbeck's writing declined after Ricketts' untimely death in 1948.

After the war, he wrote '' The Pearl'' (1947), knowing it would be filmed eventually. The story first appeared in the December 1945 issue of ''

After the war, he wrote '' The Pearl'' (1947), knowing it would be filmed eventually. The story first appeared in the December 1945 issue of '' '' Travels with Charley: In Search of America'' is a travelogue of his 1960

'' Travels with Charley: In Search of America'' is a travelogue of his 1960

In 1962, Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for literature for his "realistic and imaginative writing, combining as it does sympathetic humor and keen social perception." The selection was heavily criticized, and described as "one of the Academy's biggest mistakes" in one Swedish newspaper. The reaction of American literary critics was also harsh. ''The New York Times'' asked why the Nobel committee gave the award to an author whose "limited talent is, in his best books, watered down by tenth-rate philosophising", noting that " e international character of the award and the weight attached to it raise questions about the mechanics of selection and how close the Nobel committee is to the main currents of American writing. ... think it interesting that the laurel was not awarded to a writer ... whose significance, influence and sheer body of work had already made a more profound impression on the literature of our age". Steinbeck, when asked on the day of the announcement if he deserved the Nobel, replied: "Frankly, no." Biographer Jackson Benson notes, " is honor was one of the few in the world that one could not buy nor gain by political maneuver. It was precisely because the committee made its judgment ... on its own criteria, rather than plugging into 'the main currents of American writing' as defined by the critical establishment, that the award had value." In his acceptance speech later in the year in Stockholm, he said:

Fifty years later, in 2012, the Nobel Prize opened its archives and it was revealed that Steinbeck was a "compromise choice" among a shortlist consisting of Steinbeck, British authors

In 1962, Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for literature for his "realistic and imaginative writing, combining as it does sympathetic humor and keen social perception." The selection was heavily criticized, and described as "one of the Academy's biggest mistakes" in one Swedish newspaper. The reaction of American literary critics was also harsh. ''The New York Times'' asked why the Nobel committee gave the award to an author whose "limited talent is, in his best books, watered down by tenth-rate philosophising", noting that " e international character of the award and the weight attached to it raise questions about the mechanics of selection and how close the Nobel committee is to the main currents of American writing. ... think it interesting that the laurel was not awarded to a writer ... whose significance, influence and sheer body of work had already made a more profound impression on the literature of our age". Steinbeck, when asked on the day of the announcement if he deserved the Nobel, replied: "Frankly, no." Biographer Jackson Benson notes, " is honor was one of the few in the world that one could not buy nor gain by political maneuver. It was precisely because the committee made its judgment ... on its own criteria, rather than plugging into 'the main currents of American writing' as defined by the critical establishment, that the award had value." In his acceptance speech later in the year in Stockholm, he said:

Fifty years later, in 2012, the Nobel Prize opened its archives and it was revealed that Steinbeck was a "compromise choice" among a shortlist consisting of Steinbeck, British authors

Steinbeck and his first wife, Carol Henning, married in January 1930 in Los Angeles. By 1940, their marriage was beginning to suffer, and ended a year later, in 1941. In 1942, after his divorce from Carol, Steinbeck married Gwyndolyn "Gwyn" Conger. With his second wife Steinbeck had two sons, Thomas ("Thom") Myles Steinbeck (1944–2016) and

Steinbeck and his first wife, Carol Henning, married in January 1930 in Los Angeles. By 1940, their marriage was beginning to suffer, and ended a year later, in 1941. In 1942, after his divorce from Carol, Steinbeck married Gwyndolyn "Gwyn" Conger. With his second wife Steinbeck had two sons, Thomas ("Thom") Myles Steinbeck (1944–2016) and

John Steinbeck died in New York City on December 20, 1968, during the 1968 flu pandemic of

John Steinbeck died in New York City on December 20, 1968, during the 1968 flu pandemic of

Steinbeck's boyhood home, a turreted Victorian building in downtown Salinas, has been preserved and restored by the Valley Guild, a nonprofit organization. Fixed menu lunches are served Monday through Saturday, and the house is open for

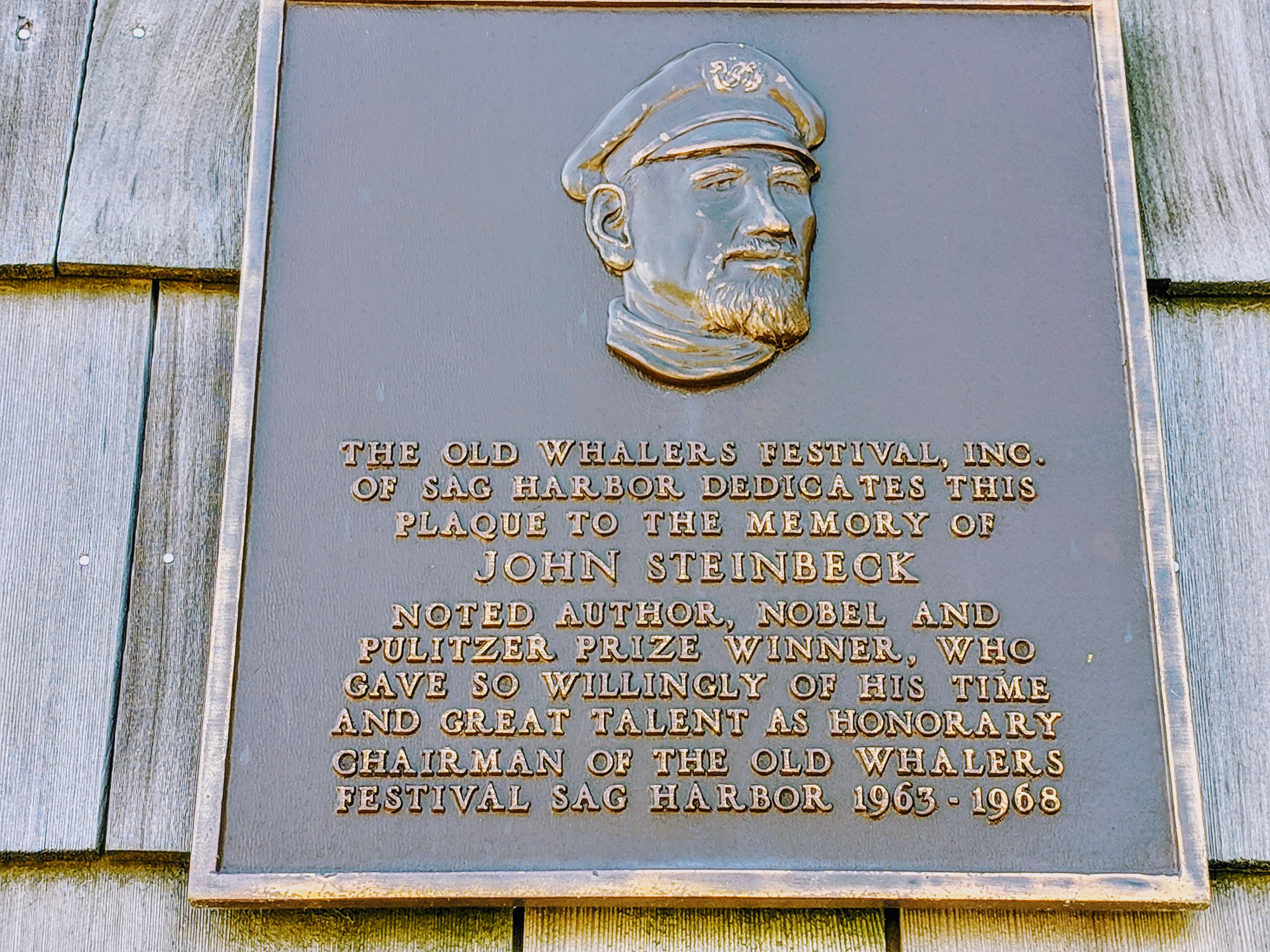

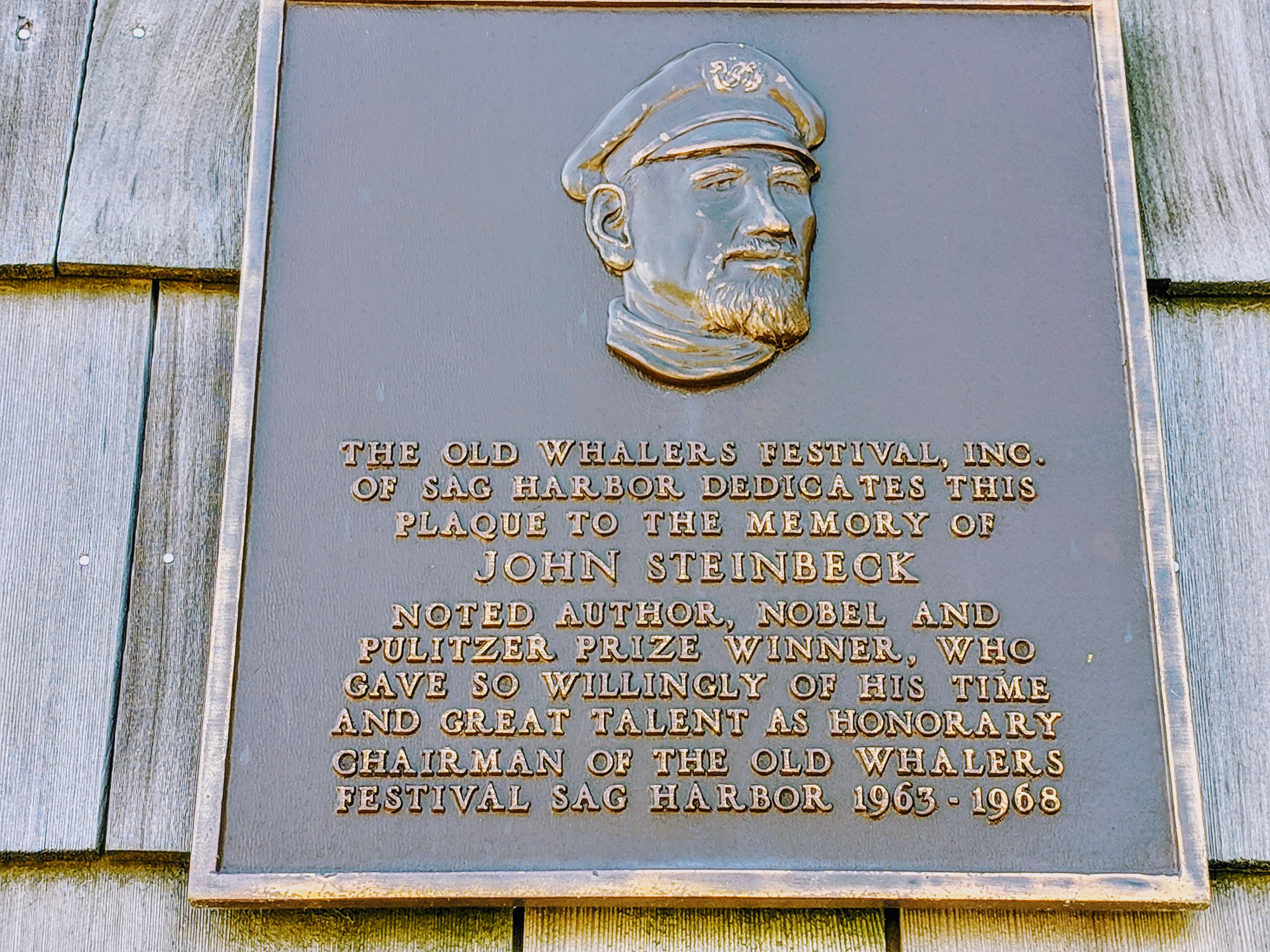

Steinbeck's boyhood home, a turreted Victorian building in downtown Salinas, has been preserved and restored by the Valley Guild, a nonprofit organization. Fixed menu lunches are served Monday through Saturday, and the house is open for  In 2019 the Sag Harbor town board approved the creation of the John Steinbeck Waterfront Park across from the iconic town windmill. The structures on the parcel were demolished and park benches installed near the beach. The Beebe windmill replica already had a plaque memorializing the author who wrote from a small hut overlooking the cove during his sojourn in the literary haven.

In 2019 the Sag Harbor town board approved the creation of the John Steinbeck Waterfront Park across from the iconic town windmill. The structures on the parcel were demolished and park benches installed near the beach. The Beebe windmill replica already had a plaque memorializing the author who wrote from a small hut overlooking the cove during his sojourn in the literary haven.

Steinbeck's contacts with

Steinbeck's contacts with

''The Short Novels of John Steinbeck: Critical Essays with a Checklist to Steinbeck Criticism''

Durham: Duke UP, 1990 . * Benson, Jackson J

''Looking for Steinbeck's Ghost''

Reno: U of Nevada P, 2002 . * Davis, Robert C. ''The Grapes of Wrath: A Collection of Critical Essays.'' Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1982. PS3537 .T3234 G734 * DeMott, Robert and Steinbeck, Elaine A., eds. ''John Steinbeck, Novels and Stories 1932–1937'' (

''John Steinbeck and the Critics''

Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2000 . * French, Warren. ''John Steinbeck's Fiction Revisited''. NY: Twayne, 1994 . * Heavilin, Barbara A. ''John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath: A Reference Guide''. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2002 . * Hughes, R. S. ''John Steinbeck: A Study of the Short Fiction''. R.S. Hughes. Boston : Twayne, 1989. . * Li, Luchen. ed. ''John Steinbeck: A Documentary Volume''. Detroit: Gale, 2005 . * Meyer, Michael J. ''The Hayashi Steinbeck Bibliography'', 1982–1996. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 1998 . * Steigerwald, Bill. ''Dogging Steinbeck: Discovering America and Exposing the Truth about 'Travels with Charley.' Kindle Edition. 2013. * Steinbeck, John Steinbeck IV and Nancy (2001). ''The Other Side of Eden: Life with John Steinbeck''. Prometheus Books. * Tamm, Eric Enno (2005)

''Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell''

Thunder's Mouth Press. .

National Steinbeck Center in Salinas, California

FBI file on John Steinbeck

The ''Steinbeck Quarterly'' journal

John Steinbeck Biography Early Years: Salinas to Stanford: 1902–1925

from

''Western American Literature Journal'': John Steinbeck

Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1945 - Mrs. Stanford Steinbeck, Gwyndolyn, Thom and John Steinbeck

*

John Steinbeck Collection, 1902–1979

Wells Fargo John Steinbeck Collection, 1870–1981

John Steinbeck and George Bernard Shaw legal files collection, 1926–1970s

held by the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature,

Nobel Laureate page

"Writings of John Steinbeck"

from

1962 Nobel Prize in Literature

The 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the American author John Steinbeck (1902–1968) "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social perception."

Laureate

Social conditions of mig ...

winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social perception." He has been called "a giant of American letters."

During his writing career, he authored 33 books, with one book coauthored alongside Edward Ricketts

Edward Flanders Robb Ricketts (May 14, 1897 – May 11, 1948) was an American marine biologist, ecologist, and philosopher. He is best known for '' Between Pacific Tides'' (1939), a pioneering study of intertidal ecology. He is also known as a m ...

, including 16 novels, six non-fiction

Nonfiction, or non-fiction, is any document or media content that attempts, in good faith, to provide information (and sometimes opinions) grounded only in facts and real life, rather than in imagination. Nonfiction is often associated with b ...

books, and two collections of short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest t ...

. He is widely known for the comic novels ''Tortilla Flat

''Tortilla Flat'' (1935) is an early John Steinbeck novel set in Monterey, California. The novel was the author's first clear critical and commercial success.

The book portrays a group of 'paisanos'—literally, countrymen—a small band of er ...

'' (1935) and ''Cannery Row

Cannery Row is the waterfront street bordering the city of Pacific Grove, but officially in the New Monterey section of Monterey, California. It was the site of a number of now-defunct sardine canning factories. The last cannery closed in 1973 ...

'' (1945), the multi-generation epic '' East of Eden'' (1952), and the novellas ''The Red Pony

''The Red Pony'' is an episodic novella written by American writer John Steinbeck in 1933. The first three chapters were published in magazines from 1933 to 1936. The full book was published in 1937 by Covici Friede. The stories in the book ...

'' (1933) and ''Of Mice and Men

''Of Mice and Men'' is a novella written by John Steinbeck. Published in 1937, it narrates the experiences of George Milton and Lennie Small, two displaced migrant ranch workers, who move from place to place in California in search of new job o ...

'' (1937). The Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

–winning ''The Grapes of Wrath

''The Grapes of Wrath'' is an American realist novel written by John Steinbeck and published in 1939. The book won the National Book Award

and Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and it was cited prominently when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Priz ...

'' (1939) is considered Steinbeck's masterpiece and part of the American literary canon. In the first 75 years after it was published, it sold 14 million copies.

Most of Steinbeck's work is set in central California

Central California is generally thought of as the middle third of the state, north of Southern California, which includes Los Angeles, and south of Northern California, which includes San Francisco. It includes the northern portion of the S ...

, particularly in the Salinas Valley

The Salinas Valley is one of the major valleys and most productive agricultural regions in California. It is located west of the San Joaquin Valley and south of San Francisco Bay and the Santa Clara Valley.

The Salinas River, which geologically ...

and the California Coast Ranges

The Coast Ranges of California span from Del Norte or Humboldt County, California, south to Santa Barbara County. The other three coastal California mountain ranges are the Transverse Ranges, Peninsular Ranges and the Klamath Mountains. ...

region. His works frequently explored the themes of fate and injustice, especially as applied to downtrodden or everyman

The everyman is a stock character of fiction. An ordinary and humble character, the everyman is generally a protagonist whose benign conduct fosters the audience's identification with them.

Origin

The term ''everyman'' was used as early as ...

protagonists

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

.

Early life

Steinbeck was born on February 27, 1902, inSalinas, California

Salinas (; Spanish for "Salt Marsh or Salt Flats") is a city in California and the county seat of Monterey County. With a population of 163,542 in the 2020 Census, Salinas is the most populous city in Monterey County. Salinas is an urban area l ...

. He was of German, English, and Irish descent. Johann Adolf Großsteinbeck (1828–1913), Steinbeck's paternal grandfather, was a founder of Mount Hope, a short-lived messianic farming colony in Palestine that disbanded after Arab attackers killed his brother and raped his brother's wife and mother-in-law. He arrived in the United States in 1858, shortening the family name to Steinbeck. The family farm in Heiligenhaus

Heiligenhaus () is a town in the district of Mettmann, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, in the suburban Rhine-Ruhr area. It lies between Düsseldorf and Essen.

Bochum University of Applied Sciences (Hochschule Bochum, formerly Fachhochs ...

, Mettmann

Mettmann () is a town in the northern part of the Bergisches Land, in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is the administrative centre of the district of Mettmann, Germany's most densely populated rural district. The town lies east of Düsseldorf ...

, Germany, is still named "Großsteinbeck".

His father, John Ernst Steinbeck (1862–1935), served as Monterey County

Monterey County ( ), officially the County of Monterey, is a county located on the Pacific coast in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, its population was 439,035. The county's largest city and county seat is Salinas.

Montere ...

treasurer. John's mother, Olive Hamilton (1867–1934), a former school teacher, shared Steinbeck's passion for reading and writing.. National Steinbeck Centre The Steinbecks were members of the Episcopal Church, although Steinbeck later became agnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficien ...

. Steinbeck lived in a small rural valley (no more than a frontier settlement) set in some of the world's most fertile soil, about 25 miles from the Pacific Coast

Pacific coast may be used to reference any coastline that borders the Pacific Ocean.

Geography Americas

Countries on the western side of the Americas have a Pacific coast as their western or southwestern border, except for Panama, where the Pac ...

. Both valley and coast would serve as settings for some of his best fiction. He spent his summers working on nearby ranches including the Post Ranch in Big Sur

Big Sur () is a rugged and mountainous section of the Central Coast of California between Carmel and San Simeon, where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. It is frequently praised for its dramatic scenery. Big Sur ...

. He later labored with migrant workers on Spreckels sugar beet farms. There he learned of the harsher aspects of the migrant life and the darker side of human nature, which supplied him with material expressed in ''Of Mice and Men

''Of Mice and Men'' is a novella written by John Steinbeck. Published in 1937, it narrates the experiences of George Milton and Lennie Small, two displaced migrant ranch workers, who move from place to place in California in search of new job o ...

''. He explored his surroundings, walking across local forests, fields, and farms.Introduction to John Steinbeck, ''The Long Valley'', pp. 9–10, John Timmerman, Penguin Publishing, 1995 While working at Spreckels Sugar Company, he sometimes worked in their laboratory, which gave him time to write. He had considerable mechanical aptitude and fondness for repairing things he owned.Jackson J. Benson, ''The True Adventures of John Steinbeck, Writer'' New York: The Viking Press, 1984. , pp. 147, 915a, 915b, 133

Steinbeck graduated from Salinas High School in 1919 and went on to study English literature at

Steinbeck graduated from Salinas High School in 1919 and went on to study English literature at Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is conside ...

near Palo Alto

Palo Alto (; Spanish for "tall stick") is a charter city in the northwestern corner of Santa Clara County, California, United States, in the San Francisco Bay Area, named after a coastal redwood tree known as El Palo Alto.

The city was es ...

, leaving without a degree in 1925. He traveled to New York City where he took odd jobs while trying to write. When he failed to publish his work, he returned to California and worked in 1928 as a tour guide and caretaker at Lake Tahoe

Lake Tahoe (; was, Dáʔaw, meaning "the lake") is a freshwater lake in the Sierra Nevada of the United States. Lying at , it straddles the state line between California and Nevada, west of Carson City. Lake Tahoe is the largest alpine lake i ...

, where he met Carol Henning, his first wife. They married in January 1930 in Los Angeles, where, with friends, he attempted to make money by manufacturing plaster mannequins

A mannequin (also called a dummy, lay figure, or dress form) is a doll, often articulated, used by artists, tailors, dressmakers, window dressers and others, especially to display or fit clothing and show off different fabrics and textiles. P ...

.

When their money ran out six months later due to a slow market, Steinbeck and Carol moved back to Pacific Grove, California

Pacific Grove is a coastal city in Monterey County, California, in the United States. The population at the 2020 census was 15,090. Pacific Grove is located between Point Pinos and Monterey.

Pacific Grove has numerous Victorian-era houses, ...

, to a cottage owned by his father, on the Monterey Peninsula

The Monterey Peninsula anchors the northern portion on the Central Coast of California and comprises the cities of Monterey, Carmel, and Pacific Grove, and the resort and community of Pebble Beach.

History Monterey

Monterey was founded i ...

a few blocks outside the Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

city limits. The elder Steinbecks gave John free housing, paper for his manuscripts, and from 1928, loans that allowed him to write without looking for work. During the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, Steinbeck bought a small boat, and later claimed that he was able to live on the fish and crabs that he gathered from the sea, and fresh vegetables from his garden and local farms. When those sources failed, Steinbeck and his wife accepted welfare, and on rare occasions, stole bacon from the local produce market. Whatever food they had, they shared with their friends. Carol became the model for Mary Talbot in Steinbeck's novel ''Cannery Row''.

In 1930, Steinbeck met the marine biologist Ed Ricketts

Edward Flanders Robb Ricketts (May 14, 1897 – May 11, 1948) was an American marine biologist, ecologist, and philosopher. He is best known for '' Between Pacific Tides'' (1939), a pioneering study of intertidal ecology. He is also known as a m ...

, who became a close friend and mentor to Steinbeck during the following decade, teaching him a great deal about philosophy and biology. Ricketts, usually very quiet, yet likable, with an inner self-sufficiency and an encyclopedic knowledge of diverse subjects, became a focus of Steinbeck's attention. Ricketts had taken a college class from Warder Clyde Allee

Warder Clyde Allee (June 5, 1885 – March 18, 1955) was an American ecologist. He is recognized to be one of the great pioneers of American ecology. Schmidt, Karl Patterson. "Warder Allee: A Biographical Memoir", National Academy of Sciences. Was ...

, a biologist and ecological theorist, who would go on to write a classic early textbook on ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

. Ricketts became a proponent of ecological thinking, in which man was only one part of a great chain of being

The great chain of being is a hierarchical structure of all matter and life, thought by medieval Christianity to have been decreed by God. The chain begins with God and descends through angels, humans, animals and plants to minerals.

The great ...

, caught in a web of life too large for him to control or understand. Meanwhile, Ricketts operated a biological lab on the coast of Monterey, selling biological samples of small animals, fish, rays, starfish, turtles, and other marine forms to schools and colleges.

Between 1930 and 1936, Steinbeck and Ricketts became close friends. Steinbeck's wife began working at the lab as secretary-bookkeeper. Steinbeck helped on an informal basis. They formed a common bond based on their love of music and art, and John learned biology and Ricketts' ecological philosophy. When Steinbeck became emotionally upset, Ricketts sometimes played music for him.

Career

Writing

Steinbeck's first novel, ''Cup of Gold

''Cup of Gold: A Life of Sir Henry Morgan, Buccaneer, with Occasional Reference to History'' (1929) was John Steinbeck's first novel, a work of historical fiction based loosely on the life and death of 17th-century privateer Henry Morgan

...

'', published in 1929, is loosely based on the life and death of privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

Henry Morgan

Sir Henry Morgan ( cy, Harri Morgan; – 25 August 1688) was a privateer, plantation owner, and, later, Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica. From his base in Port Royal, Jamaica, he raided settlements and shipping on the Spanish Main, becoming we ...

. It centers on Morgan's assault and sacking of Panamá Viejo

Panamá Viejo (English: "Old Panama"), also known as Panamá la Vieja, is the remaining part of the original Panama City, the former capital of Panama, which was destroyed in 1671 by the Welsh privateer Henry Morgan. It is located in the suburbs ...

, sometimes referred to as the "Cup of Gold", and on the women, brighter than the sun, who were said to be found there. In 1930, Steinbeck wrote a werewolf murder mystery, ''Murder at Full Moon'', that has never been published because Steinbeck considered it unworthy of publication.

Between 1930 and 1933, Steinbeck produced three shorter works. ''The Pastures of Heaven

''The Pastures of Heaven'' is a short story cycle by John Steinbeck, first published in 1932, consisting of twelve interconnected stories about a valley, the Corral de Tierra, in Monterey, California, which was discovered by a Spanish corporal w ...

'', published in 1932, consists of twelve interconnected stories about a valley near Monterey, which was discovered by a Spanish corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non- ...

while chasing runaway Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

slaves. In 1933 Steinbeck published ''The Red Pony

''The Red Pony'' is an episodic novella written by American writer John Steinbeck in 1933. The first three chapters were published in magazines from 1933 to 1936. The full book was published in 1937 by Covici Friede. The stories in the book ...

'', a 100-page, four-chapter story weaving in memories of Steinbeck's childhood. ''To a God Unknown

''To a God Unknown'' is a novel by John Steinbeck, first published in 1933. The book was Steinbeck's third novel (after '' Cup of Gold'' and '' The Pastures of Heaven''). Steinbeck found ''To a God Unknown'' extremely difficult to write; taking ...

'', named after a Vedic

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute th ...

hymn, follows the life of a homesteader and his family in California, depicting a character with a primal and pagan worship of the land he works. Although he had not achieved the status of a well-known writer, he never doubted that he would achieve greatness.

Steinbeck achieved his first critical success with ''Tortilla Flat

''Tortilla Flat'' (1935) is an early John Steinbeck novel set in Monterey, California. The novel was the author's first clear critical and commercial success.

The book portrays a group of 'paisanos'—literally, countrymen—a small band of er ...

'' (1935), a novel set in post-war Monterey, California, that won the California Commonwealth Club's Gold Medal. It portrays the adventures of a group of classless and usually homeless young men in Monterey after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, just before U.S. prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholi ...

. They are portrayed in ironic comparison to mythic knights on a quest and reject nearly all the standard mores of American society in enjoyment of a dissolute life devoted to wine, lust, camaraderie and petty theft. In presenting the 1962 Nobel Prize to Steinbeck, the Swedish Academy cited "spicy and comic tales about a gang of ''paisanos'', asocial individuals who, in their wild revels, are almost caricatures of King Arthur's Knights of the Round Table. It has been said that in the United States this book came as a welcome antidote to the gloom of the then prevailing depression." ''Tortilla Flat'' was adapted as a 1942 film of the same name, starring Spencer Tracy

Spencer Bonaventure Tracy (April 5, 1900 – June 10, 1967) was an American actor. He was known for his natural performing style and versatility. One of the major stars of Hollywood's Golden Age, Tracy was the first actor to win two cons ...

, Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr (; born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler; November 9, 1914 January 19, 2000) was an Austrian-born American film actress and inventor. A film star during Hollywood's golden age, Lamarr has been described as one of the greatest movie actress ...

and John Garfield

John Garfield (born Jacob Julius Garfinkle, March 4, 1913 – May 21, 1952) was an American actor who played brooding, rebellious, working-class characters. He grew up in poverty in New York City. In the early 1930s, he became a member of ...

, a friend of Steinbeck. With some of the proceeds, he built a summer ranch-home in Los Gatos

Los Gatos (, ; ) is an incorporated town in Santa Clara County, California, United States. The population is 33,529 according to the 2020 census. It is located in the San Francisco Bay Area just southwest of San Jose in the foothills of th ...

.

Steinbeck began to write a series of "California novels" and Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl was a period of severe dust storms that greatly damaged the ecology and agriculture of the American and Canadian prairies during the 1930s. The phenomenon was caused by a combination of both natural factors (severe drought) a ...

fiction, set among common people during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. These included '' In Dubious Battle'', ''Of Mice and Men

''Of Mice and Men'' is a novella written by John Steinbeck. Published in 1937, it narrates the experiences of George Milton and Lennie Small, two displaced migrant ranch workers, who move from place to place in California in search of new job o ...

'' and ''The Grapes of Wrath

''The Grapes of Wrath'' is an American realist novel written by John Steinbeck and published in 1939. The book won the National Book Award

and Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and it was cited prominently when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Priz ...

''. He also wrote an article series called '' The Harvest Gypsies'' for the ''San Francisco News'' about the plight of the migrant worker.

''Of Mice and Men'' was a drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has b ...

about the dreams of two migrant agricultural laborers in California. It was critically acclaimed and Steinbeck's 1962 Nobel Prize citation called it a "little masterpiece".

Its stage production was a hit, starring Wallace Ford

Wallace Ford (born Samuel Grundy Jones; 12 February 1898 – 11 June 1966) was an English-born naturalized American vaudevillian, stage performer and screen actor. Usually playing wise-cracking characters, he combined a tough but friendly-fac ...

as George and Broderick Crawford

William Broderick Crawford (December 9, 1911 – April 26, 1986) was an American stage, film, radio, and television actor, often cast in tough-guy roles and best known for his Oscar- and Golden Globe-winning portrayal of Willie Stark in ''All th ...

as George's companion, the mentally childlike, but physically powerful itinerant farmhand Lennie. Steinbeck refused to travel from his home in California to attend any performance of the play during its New York run, telling director George S. Kaufman

George Simon Kaufman (November 16, 1889June 2, 1961) was an American playwright, theater director and producer, humorist, and drama critic. In addition to comedies and political satire, he wrote several musicals for the Marx Brothers and other ...

that the play as it existed in his own mind was "perfect" and that anything presented on stage would only be a disappointment. Steinbeck wrote two more stage plays (''The Moon Is Down

''The Moon Is Down'' is a novel by American writer John Steinbeck. Fashioned for adaptation for the theatre and for which Steinbeck received the Norwegian King Haakon VII Freedom Cross, it was published by Viking Press in March 1942. The story ...

'' and ''Burning Bright

''Burning Bright'' is a 1950 novella by John Steinbeck written as an experiment with producing a play in novel format. Rather than providing only the dialogue and brief stage directions as would be expected in a play, Steinbeck fleshes out the s ...

'').

''Of Mice and Men'' was also adapted as a 1939 Hollywood film, with Lon Chaney, Jr.

Creighton Tull Chaney (February10, 1906 – July12, 1973), known by his stage name Lon Chaney Jr., was an American actor known for playing Larry Talbot in the film '' The Wolf Man'' (1941) and its various crossovers, Count Alucard (Dra ...

as Lennie (he had filled the role in the Los Angeles stage production) and Burgess Meredith

Oliver Burgess Meredith (November 16, 1907 – September 9, 1997) was an American actor and filmmaker whose career encompassed theater, film, and television.

Active for more than six decades, Meredith has been called "a virtuosic actor" and "on ...

as George. Meredith and Steinbeck became close friends for the next two decades. Another film based on the novella was made in 1992 starring Gary Sinise

Gary Alan Sinise (; born March 17, 1955) is an American actor, humanitarian, and musician. Among other awards, he has won a Primetime Emmy Award, a Golden Globe Award, a Tony Award, and four Screen Actors Guild Awards. He has also received a sta ...

as George and John Malkovich

John Malkovich (born December 9, 1953) is an American actor. He is the recipient of several accolades, including a Primetime Emmy Award, in addition to nominations for two Academy Awards, a British Academy Film Award, two Screen Actors Guild Aw ...

as Lennie.

Steinbeck followed this wave of success with ''The Grapes of Wrath

''The Grapes of Wrath'' is an American realist novel written by John Steinbeck and published in 1939. The book won the National Book Award

and Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and it was cited prominently when Steinbeck was awarded the Nobel Priz ...

'' (1939), based on newspaper articles about migrant agricultural workers that he had written in San Francisco. It is commonly considered his greatest work. According to ''The New York Times'', it was the best-selling book of 1939 and 430,000 copies had been printed by February 1940. In that month, it won the National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The Nat ...

, favorite fiction book of 1939, voted by members of the American Booksellers Association

The American Booksellers Association (ABA) is a non-profit trade association founded in 1900 that promotes independent bookstores in the United States. ABA's core members are key participants in their communities' local economy and culture, and t ...

."1939 Book Awards Given by Critics: Elgin Groseclose's 'Ararat' is Picked as Work Which Failed to Get Due Recognition", ''The New York Times'', February 14, 1940, p. 25. ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times (1851–2007). Later that year, it won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published durin ...

"Novel"(Winners 1917–1947). The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved January 28, 2012. and was adapted as a film directed by

John Ford

John Martin Feeney (February 1, 1894 – August 31, 1973), known professionally as John Ford, was an American film director and naval officer. He is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential filmmakers of his generation. He ...

, starring Henry Fonda

Henry Jaynes Fonda (May 16, 1905 – August 12, 1982) was an American actor. He had a career that spanned five decades on Broadway and in Hollywood. He cultivated an everyman screen image in several films considered to be classics.

Born and ra ...

as Tom Joad; Fonda was nominated for the best actor Academy Award. ''Grapes'' was controversial. Steinbeck's New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

political views, negative portrayal of aspects of capitalism, and sympathy for the plight of workers, led to a backlash against the author, especially close to home. Claiming the book both was obscene and misrepresented conditions in the county, the Kern County

Kern County is a county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 909,235. Its county seat is Bakersfield.

Kern County comprises the Bakersfield, California, Metropolitan statistical area. The county sp ...

Board of Supervisors

A board of supervisors is a governmental body that oversees the operation of county government in the U.S. states of Arizona, California, Iowa, Mississippi, Virginia, and Wisconsin, as well as 16 counties in New York. There are equivalent agen ...

banned the book from the county's publicly funded schools and libraries in August 1939. This ban lasted until January 1941.. pacific.net.au

Of the controversy, Steinbeck wrote, "The vilification of me out here from the large landowners and bankers is pretty bad. The latest is a rumor started by them that the Okie

An Okie is a person identified with the state of Oklahoma. This connection may be residential, ethnic, historical or cultural. For most Okies, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being Oklahoman. ...

s hate me and have threatened to kill me for lying about them. I'm frightened at the rolling might of this damned thing. It is completely out of hand; I mean a kind of hysteria about the book is growing that is not healthy."

The film versions of ''The Grapes of Wrath'' and ''Of Mice and Men'' (by two different movie studios) were in production simultaneously, allowing Steinbeck to spend a full day on the set of ''The Grapes of Wrath'' and the next day on the set of ''Of Mice and Men.''

Ed Ricketts

In the 1930s and 1940s,Ed Ricketts

Edward Flanders Robb Ricketts (May 14, 1897 – May 11, 1948) was an American marine biologist, ecologist, and philosopher. He is best known for '' Between Pacific Tides'' (1939), a pioneering study of intertidal ecology. He is also known as a m ...

strongly influenced Steinbeck's writing. Steinbeck frequently took small trips with Ricketts along the California coast to give himself time off from his writing and to collect biological specimens, which Ricketts sold for a living. Their coauthored book, ''Sea of Cortez'' (December 1941), about a collecting expedition to the Gulf of California

The Gulf of California ( es, Golfo de California), also known as the Sea of Cortés (''Mar de Cortés'') or Sea of Cortez, or less commonly as the Vermilion Sea (''Mar Bermejo''), is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Baja C ...

in 1940, which was part travelogue and part natural history, published just as the U.S. entered World War II, never found an audience and did not sell well. However, in 1951, Steinbeck republished the narrative portion of the book as ''The Log from the Sea of Cortez

''The Log from the Sea of Cortez'' is an English-language book written by American author John Steinbeck and published in 1951. It details a six-week (March 11 – April 20) marine specimen-collecting boat expedition he made in 1940 at variou ...

'', under his name only (though Ricketts had written some of it). This work remains in print today.

Although Carol accompanied Steinbeck on the trip, their marriage was beginning to suffer, and ended a year later, in 1941, even as Steinbeck worked on the manuscript for the book. In 1942, after his divorce from Carol he married Gwyndolyn "Gwyn" Conger.

Ricketts was Steinbeck's model for the character of "Doc" in ''Cannery Row

Cannery Row is the waterfront street bordering the city of Pacific Grove, but officially in the New Monterey section of Monterey, California. It was the site of a number of now-defunct sardine canning factories. The last cannery closed in 1973 ...

'' (1945) and ''Sweet Thursday

''Sweet Thursday'' is a 1954 novel by John Steinbeck. It is a sequel to ''Cannery Row'' and set in the years after the end of World War II. According to Steinbeck, "Sweet Thursday" is the day between Lousy Wednesday and Waiting Friday.

Plot su ...

'' (1954), "Friend Ed" in ''Burning Bright

''Burning Bright'' is a 1950 novella by John Steinbeck written as an experiment with producing a play in novel format. Rather than providing only the dialogue and brief stage directions as would be expected in a play, Steinbeck fleshes out the s ...

'', and characters in '' In Dubious Battle'' (1936) and ''The Grapes of Wrath'' (1939). Ecological themes recur in Steinbeck's novels of the period.Bruce Robison, "Mavericks on Cannery Row," ''American Scientist

__NOTOC__

''American Scientist'' (informally abbreviated ''AmSci'') is an American bimonthly science and technology magazine published since 1913 by Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society. In the beginning of 2000s the headquarters was in ...

'', vol. 92, no. 6 (November–December 2004), p. 1: a review of Eric Enno Tamm''Beyond the Outer Shores: The Untold Odyssey of Ed Ricketts, the Pioneering Ecologist who Inspired John Steinbeck and Joseph Campbell''

, Four Walls Eight Windows, 2004. Steinbeck's close relations with Ricketts ended in 1941 when Steinbeck moved away from Pacific Grove and divorced his wife Carol. Ricketts' biographer Eric Enno Tamm opined that, except for '' East of Eden'' (1952), Steinbeck's writing declined after Ricketts' untimely death in 1948.

1940s–1960s work

Steinbeck's novel ''The Moon Is Down

''The Moon Is Down'' is a novel by American writer John Steinbeck. Fashioned for adaptation for the theatre and for which Steinbeck received the Norwegian King Haakon VII Freedom Cross, it was published by Viking Press in March 1942. The story ...

'' (1942), about the Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

-inspired spirit of resistance in an occupied village in Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe Northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54°N, or may be based on other geographical factors ...

, was made into a film almost immediately. It was presumed that the unnamed country of the novel was Norway and the occupiers the Germans. In 1945, Steinbeck received the King Haakon VII Freedom Cross

King Haakon VII's Freedom Cross ( no, Haakon VIIs Frihetskors) was established in Norway on 18 May 1945. The medal is awarded to Norwegian or foreign military or civilian personnel for outstanding achievement in wartime. It is ranked fifth in the ...

for his literary contributions to the Norwegian resistance movement

The Norwegian resistance ( Norwegian: ''Motstandsbevegelsen'') to the occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany began after Operation Weserübung in 1940 and ended in 1945. It took several forms:

*Asserting the legitimacy of the exiled governme ...

.

In 1943, Steinbeck served as a World War II war correspondent for the ''New York Herald Tribune

The ''New York Herald Tribune'' was a newspaper published between 1924 and 1966. It was created in 1924 when Ogden Mills Reid of the ''New-York Tribune'' acquired the '' New York Herald''. It was regarded as a "writer's newspaper" and competed ...

'' and worked with the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

(predecessor of the CIA). It was at that time he became friends with Will Lang, Jr.

William John Lang Jr. (October 7, 1914 – January 21, 1968) was an American journalist and a bureau head for '' Life'' magazine.

Early career

Lang was born on the south side of Chicago. While attending the University of Chicago in 1936, he ...

of ''Time''/''Life'' magazine. During the war, Steinbeck accompanied the commando raids of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

Douglas Elton Fairbanks Jr., (December 9, 1909 – May 7, 2000) was an American actor, producer and decorated naval officer of World War II. He is best known for starring in such films as ''The Prisoner of Zenda'' (1937), ''Gunga Din'' (1939) ...

's Beach Jumpers

Beach Jumpers were U.S. Navy special warfare units organized during World War II by Lieutenant Douglas Fairbanks Jr. They specialized in deception and psychological warfare. The units were active from 1943 to 1946 and 1951 to 1972.

Inspired by ...

program, which launched small-unit diversion operations against German-held islands in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. At one point, he accompanied Fairbanks on an invasion of an island off the coast of Italy and used a Thompson submachine gun

The Thompson submachine gun (also known as the "Tommy Gun", "Chicago Typewriter", "Chicago Piano", “Trench Sweeper” or "Trench Broom") is a blowback-operated, air-cooled, Magazine-fed rifle, magazine-fed Selective fire, selective-fire subm ...

to help capture Italian and German prisoners. Some of his writings from this period were incorporated in the documentary '' Once There Was a War'' (1958).

Steinbeck returned from the war with a number of wounds from shrapnel and some psychological trauma. He treated himself, as ever, by writing. He wrote Alfred Hitchcock

Sir Alfred Joseph Hitchcock (13 August 1899 – 29 April 1980) was an English filmmaker. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of cinema. In a career spanning six decades, he directed over 50 featur ...

's movie, '' Lifeboat'' (1944), and with screenwriter Jack Wagner, ''A Medal for Benny

''A Medal for Benny'' is a 1945 American film directed by Irving Pichel. The story was conceived by writer Jack Wagner, who enlisted his long-time friend John Steinbeck to help him put it into script form. The film was released by Paramount Pictu ...

'' (1945), about paisanos from ''Tortilla Flat

''Tortilla Flat'' (1935) is an early John Steinbeck novel set in Monterey, California. The novel was the author's first clear critical and commercial success.

The book portrays a group of 'paisanos'—literally, countrymen—a small band of er ...

'' going to war. He later requested that his name be removed from the credits of ''Lifeboat,'' because he believed the final version of the film had racist undertones. In 1944, suffering from homesickness for his Pacific Grove/Monterey life of the 1930s, he wrote ''Cannery Row

Cannery Row is the waterfront street bordering the city of Pacific Grove, but officially in the New Monterey section of Monterey, California. It was the site of a number of now-defunct sardine canning factories. The last cannery closed in 1973 ...

'' (1945), which became so famous that in 1958 Ocean View Avenue in Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

, the setting of the book, was renamed Cannery Row.

After the war, he wrote '' The Pearl'' (1947), knowing it would be filmed eventually. The story first appeared in the December 1945 issue of ''

After the war, he wrote '' The Pearl'' (1947), knowing it would be filmed eventually. The story first appeared in the December 1945 issue of ''Woman's Home Companion

''Woman's Home Companion'' was an American monthly magazine, published from 1873 to 1957. It was highly successful, climbing to a circulation peak of more than four million during the 1930s and 1940s. The magazine, headquartered in Springfield, O ...

'' magazine as "The Pearl of the World". It was illustrated by John Alan Maxwell. The novel is an imaginative telling of a story which Steinbeck had heard in La Paz in 1940, as related in ''The Log From the Sea of Cortez'', which he described in Chapter 11 as being "so much like a parable that it almost can't be". Steinbeck traveled to Cuernavaca

Cuernavaca (; nci-IPA, Cuauhnāhuac, kʷawˈnaːwak "near the woods", ) is the capital and largest city of the state of Morelos in Mexico. The city is located around a 90-minute drive south of Mexico City using the Federal Highway 95D.

The na ...

, Mexico for the filming with Wagner who helped with the script; on this trip he would be inspired by the story of Emiliano Zapata

Emiliano Zapata Salazar (; August 8, 1879 – April 10, 1919) was a Mexican revolutionary. He was a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, the main leader of the people's revolution in the Mexican state of Morelos, and the ins ...

, and subsequently wrote a film script (''Viva Zapata!

''Viva Zapata!'' is a 1952 American Western film directed by Elia Kazan and starring Marlon Brando. The screenplay was written by John Steinbeck, using Edgcomb Pinchon's 1941 book ''Zapata the Unconquerable'' as a guide. The cast includes Jean ...

'') directed by Elia Kazan

Elia Kazan (; born Elias Kazantzoglou ( el, Ηλίας Καζαντζόγλου); September 7, 1909 – September 28, 2003) was an American film and theatre director, producer, screenwriter and actor, described by ''The New York Times'' as "one o ...

and starring Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor. Considered one of the most influential actors of the 20th century, he received numerous accolades throughout his career, which spanned six decades, including two Academ ...

and Anthony Quinn

Manuel Antonio Rodolfo Quinn Oaxaca (April 21, 1915 – June 3, 2001), known professionally as Anthony Quinn, was a Mexican-American actor. He was known for his portrayal of earthy, passionate characters "marked by a brutal and elemental v ...

.

In 1947, Steinbeck made his first trip to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

with photographer Robert Capa

Robert Capa (born Endre Ernő Friedmann; October 22, 1913 – May 25, 1954) was a Hungarian-American war photographer and photojournalist as well as the companion and professional partner of photographer Gerda Taro. He is considered by some to b ...

. They visited Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, Kyiv

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

, Tbilisi

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million pe ...

, Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), second largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's ...

and Stalingrad

Volgograd ( rus, Волгогра́д, a=ru-Volgograd.ogg, p=vəɫɡɐˈɡrat), formerly Tsaritsyn (russian: Цари́цын, Tsarítsyn, label=none; ) (1589–1925), and Stalingrad (russian: Сталингра́д, Stalingrád, label=none; ) ...

, some of the first Americans to visit many parts of the USSR since the communist revolution

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution often, but not necessarily, inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aims to replace capitalism with communism. Depending on the type of government, socialism can be used as an intermediate stag ...

. Steinbeck's 1948 book about their experiences, '' A Russian Journal'', was illustrated with Capa's photos. In 1948, the year the book was published, Steinbeck was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, music, and art. Its fixed number membership is elected for lifetime appointments. Its headqu ...

.

In 1952 Steinbeck's longest novel, '' East of Eden'', was published. According to his third wife, Elaine, he considered it his ''magnum opus'', his greatest novel.

In 1952, John Steinbeck appeared as the on-screen narrator of 20th Century Fox

20th Century Studios, Inc. (previously known as 20th Century Fox) is an American film production company headquartered at the Fox Studio Lot in the Century City area of Los Angeles. As of 2019, it serves as a film production arm of Walt Disn ...

's film, '' O. Henry's Full House''. Although Steinbeck later admitted he was uncomfortable before the camera, he provided interesting introductions to several filmed adaptations of short stories by the legendary writer O. Henry

William Sydney Porter (September 11, 1862 – June 5, 1910), better known by his pen name O. Henry, was an American writer known primarily for his short stories, though he also wrote poetry and non-fiction. His works include "The Gift of the ...

. About the same time, Steinbeck recorded readings of several of his short stories for Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese conglomerate Sony. It was founded on January 15, 1889, evolving from the A ...

; the recordings provide a record of Steinbeck's deep, resonant voice.

Following the success of ''Viva Zapata!'', Steinbeck collaborated with Kazan on the 1955 film '' East of Eden'', James Dean

James Byron Dean (February 8, 1931September 30, 1955) was an American actor. He is remembered as a cultural icon of teenage disillusionment and social estrangement, as expressed in the title of his most celebrated film, '' Rebel Without a Caus ...

's movie debut.

From March to October 1959, Steinbeck and his third wife Elaine rented a cottage in the hamlet of Discove, Redlynch, near Bruton

Bruton ( ) is a market town, electoral ward, and civil parish in Somerset, England, on the River Brue and the A359 between Frome and Yeovil. It is 7 miles (11 km) south-east of Shepton Mallet, just south of Snakelake Hill and Coombe Hill, 10 ...

in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

, England, while Steinbeck researched his retelling of the Arthurian legend

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

and the Knights of the Round Table

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in lit ...

. Glastonbury Tor

Glastonbury Tor is a hill near Glastonbury in the English county of Somerset, topped by the roofless St Michael's Tower, a Grade I listed building. The entire site is managed by the National Trust and has been designated a scheduled monument. T ...

was visible from the cottage, and Steinbeck also visited the nearby hillfort

A hillfort is a type of earthwork used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Some were used in the post-Roma ...

of Cadbury Castle, the supposed site of King Arthur's court of Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as th ...

. The unfinished manuscript was published after his death in 1976, as ''The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights

''The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights'' (1976) is John Steinbeck's retelling of the Arthurian legend, based on the Winchester Manuscript text of Sir Thomas Malory's '' Le Morte d'Arthur''. He began his adaptation in November 1956. Stei ...

''. The Steinbecks recounted the time spent in Somerset as the happiest of their life together.

'' Travels with Charley: In Search of America'' is a travelogue of his 1960

'' Travels with Charley: In Search of America'' is a travelogue of his 1960 road trip

A road trip, sometimes spelled roadtrip, is a long-distance journey on the road. Typically, road trips are long distances travelled by automobile.

History

First road trips by automobile

The world's first recorded long-distance road trip by ...

with his poodle

The Poodle, called the Pudel in German and the Caniche in French, is a breed of water dog. The breed is divided into four varieties based on size, the Standard Poodle, Medium Poodle, Miniature Poodle and Toy Poodle, although the Medium Poodle var ...

Charley. Steinbeck bemoans his lost youth and roots, while dispensing both criticism and praise for the United States. According to Steinbeck's son Thom, Steinbeck made the journey because he knew he was dying and wanted to see the country one last time.

Steinbeck's last novel, '' The Winter of Our Discontent'' (1961), examines moral decline in the United States. The protagonist Ethan grows discontented with his own moral decline and that of those around him. The book has a very different tone from Steinbeck's amoral and ecological stance in earlier works such as ''Tortilla Flat'' and ''Cannery Row''. It was not a critical success. Many reviewers recognized the importance of the novel, but were disappointed that it was not another ''Grapes of Wrath''.Cynthia Burkhead, ''The students companion to John Steinbeck'', Greenwood Press, 2002, p. 24

In the Nobel Prize presentation speech the next year, however, the Swedish Academy cited it most favorably: "Here he attained the same standard which he set in The Grapes of Wrath. Again he holds his position as an independent expounder of the truth with an unbiased instinct for what is genuinely American, be it good or bad."

Apparently taken aback by the critical reception of this novel, and the critical outcry when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962, Steinbeck published no more fiction in the remaining six years before his death.

Nobel Prize

In 1962, Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for literature for his "realistic and imaginative writing, combining as it does sympathetic humor and keen social perception." The selection was heavily criticized, and described as "one of the Academy's biggest mistakes" in one Swedish newspaper. The reaction of American literary critics was also harsh. ''The New York Times'' asked why the Nobel committee gave the award to an author whose "limited talent is, in his best books, watered down by tenth-rate philosophising", noting that " e international character of the award and the weight attached to it raise questions about the mechanics of selection and how close the Nobel committee is to the main currents of American writing. ... think it interesting that the laurel was not awarded to a writer ... whose significance, influence and sheer body of work had already made a more profound impression on the literature of our age". Steinbeck, when asked on the day of the announcement if he deserved the Nobel, replied: "Frankly, no." Biographer Jackson Benson notes, " is honor was one of the few in the world that one could not buy nor gain by political maneuver. It was precisely because the committee made its judgment ... on its own criteria, rather than plugging into 'the main currents of American writing' as defined by the critical establishment, that the award had value." In his acceptance speech later in the year in Stockholm, he said:

Fifty years later, in 2012, the Nobel Prize opened its archives and it was revealed that Steinbeck was a "compromise choice" among a shortlist consisting of Steinbeck, British authors

In 1962, Steinbeck won the Nobel Prize for literature for his "realistic and imaginative writing, combining as it does sympathetic humor and keen social perception." The selection was heavily criticized, and described as "one of the Academy's biggest mistakes" in one Swedish newspaper. The reaction of American literary critics was also harsh. ''The New York Times'' asked why the Nobel committee gave the award to an author whose "limited talent is, in his best books, watered down by tenth-rate philosophising", noting that " e international character of the award and the weight attached to it raise questions about the mechanics of selection and how close the Nobel committee is to the main currents of American writing. ... think it interesting that the laurel was not awarded to a writer ... whose significance, influence and sheer body of work had already made a more profound impression on the literature of our age". Steinbeck, when asked on the day of the announcement if he deserved the Nobel, replied: "Frankly, no." Biographer Jackson Benson notes, " is honor was one of the few in the world that one could not buy nor gain by political maneuver. It was precisely because the committee made its judgment ... on its own criteria, rather than plugging into 'the main currents of American writing' as defined by the critical establishment, that the award had value." In his acceptance speech later in the year in Stockholm, he said:

Fifty years later, in 2012, the Nobel Prize opened its archives and it was revealed that Steinbeck was a "compromise choice" among a shortlist consisting of Steinbeck, British authors Robert Graves

Captain Robert von Ranke Graves (24 July 1895 – 7 December 1985) was a British poet, historical novelist and critic. His father was Alfred Perceval Graves, a celebrated Irish poet and figure in the Gaelic revival; they were both Celt ...

and Lawrence Durrell

Lawrence George Durrell (; 27 February 1912 – 7 November 1990) was an expatriate British novelist, poet, dramatist, and travel writer. He was the eldest brother of naturalist and writer Gerald Durrell.

Born in India to British colonial p ...

, French dramatist Jean Anouilh

Jean Marie Lucien Pierre Anouilh (; 23 June 1910 – 3 October 1987) was a French dramatist whose career spanned five decades. Though his work ranged from high drama to absurdist farce, Anouilh is best known for his 1944 play ''Antigone'', an a ...

and Danish author Karen Blixen

Baroness Karen Christenze von Blixen-Finecke (born Dinesen; 17 April 1885 – 7 September 1962) was a Danish author who wrote works in Danish and English. She is also known under her pen names Isak Dinesen, used in English-speaking countrie ...

. The declassified documents showed that he was chosen as the best of a bad lot. "There aren't any obvious candidates for the Nobel prize and the prize committee is in an unenviable situation," wrote committee member Henry Olsson. Although the committee believed Steinbeck's best work was behind him by 1962, committee member Anders Österling

Anders Österling (13 April 1884 – 13 December 1981) was a Swedish poet, critic and translator. In 1919 he was elected as a member of the Swedish Academy when he was 35 years old and served the Academy for 62 years, longer than any other me ...

believed the release of his novel '' The Winter of Our Discontent'' showed that "after some signs of slowing down in recent years, teinbeck hasregained his position as a social truth-teller nd is anauthentic realist fully equal to his predecessors Sinclair Lewis and Ernest Hemingway."

Although modest about his own talent as a writer, Steinbeck talked openly of his own admiration of certain writers. In 1953, he wrote that he considered cartoonist Al Capp

Alfred Gerald Caplin (September 28, 1909 – November 5, 1979), better known as Al Capp, was an American cartoonist and humorist best known for the satirical comic strip ''Li'l Abner'', which he created in 1934 and continued writing and (wi ...

, creator of the satirical ''Li'l Abner

''Li'l Abner'' is a satirical American comic strip that appeared in many newspapers in the United States, Canada and Europe. It featured a fictional clan of hillbillies in the impoverished mountain village of Dogpatch, USA. Written and drawn b ...

'', "possibly the best writer in the world today." At his own first Nobel Prize press conference he was asked his favorite authors and works and replied: "Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fi ...

's short stories and nearly everything Faulkner

William Cuthbert Faulkner (; September 25, 1897 – July 6, 1962) was an American writer known for his novels and short stories set in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, based on Lafayette County, Mississippi, where Faulkner spent most of ...

wrote."

In September 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

awarded Steinbeck the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

.

In 1967, at the behest of ''Newsday

''Newsday'' is an American daily newspaper that primarily serves Nassau and Suffolk counties on Long Island, although it is also sold throughout the New York metropolitan area. The slogan of the newspaper is "Newsday, Your Eye on LI", and fo ...

'' magazine, Steinbeck went to Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

to report on the war. He thought of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

as a heroic venture and was considered a hawk

Hawks are birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are widely distributed and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

* The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks and others. This subfa ...

for his position on the war. His sons served in Vietnam before his death, and Steinbeck visited one son in the battlefield. At one point he was allowed to man a machine-gun watch position at night at a firebase while his son and other members of his platoon slept.

Personal life

Steinbeck and his first wife, Carol Henning, married in January 1930 in Los Angeles. By 1940, their marriage was beginning to suffer, and ended a year later, in 1941. In 1942, after his divorce from Carol, Steinbeck married Gwyndolyn "Gwyn" Conger. With his second wife Steinbeck had two sons, Thomas ("Thom") Myles Steinbeck (1944–2016) and

Steinbeck and his first wife, Carol Henning, married in January 1930 in Los Angeles. By 1940, their marriage was beginning to suffer, and ended a year later, in 1941. In 1942, after his divorce from Carol, Steinbeck married Gwyndolyn "Gwyn" Conger. With his second wife Steinbeck had two sons, Thomas ("Thom") Myles Steinbeck (1944–2016) and John Steinbeck IV

John Ernst Steinbeck IV (June 12, 1946 – February 7, 1991) was an American journalist and author. He was the second child of the Nobel Prize-winning author John Ernst Steinbeck. In 1965, he was drafted into the United States Army and served i ...

(1946–1991).

In May 1948, Steinbeck returned to California on an emergency trip to be with his friend Ed Ricketts, who had been seriously injured when a train struck his car. Ricketts died hours before Steinbeck arrived. Upon returning home, Steinbeck was confronted by Gwyn, who asked for a divorce, which became final in October. Steinbeck spent the year after Ricketts' death in deep depression.

In June 1949, Steinbeck met stage-manager Elaine Scott at a restaurant in Carmel, California

Carmel-by-the-Sea (), often simply called Carmel, is a city in Monterey County, California, United States, founded in 1902 and municipal corporation, incorporated on October 31, 1916. Situated on the Monterey Peninsula, Carmel is known for its n ...

. Steinbeck and Scott eventually began a relationship and in December 1950 they married, within a week of the finalizing of Scott's own divorce from actor Zachary Scott

Zachary Scott (February 21, 1914 – October 3, 1965)Obituary '' Variety'', October 6, 1965. was an American actor who was known for his roles as villains and "mystery men".

Early life

Scott was born in Austin, Texas, the son of Sallie L ...

. This third marriage for Steinbeck lasted until his death in 1968. Steinbeck was also an acquaintance with the modernist poet Robinson Jeffers

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet, known for his work about the central California coast. Much of Jeffers's poetry was written in narrative and epic form. However, he is also known for his short ...

, a Californian neighbor. In a Letter to Elizabeth Otis, Steinbeck wrote, "Robinson Jeffers and his wife came in to call the other day. He looks a little older but that is all. And she is just the same.’”

In 1962, Steinbeck began acting as friend and mentor to the young writer and naturalist Jack Rudloe

Jack Rudloe is a writer, naturalist, and environmental activist from Panacea, Florida, United States, who co-founded Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory.

Biography

Jack Rudloe was born in Brooklyn, New York on February 17, 1943. At age 14, he mo ...

, who was trying to establish his own biological supply company, now Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory

Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory (GSML) is an independent not-for-profit marine research and education organization and public aquarium in Panacea, Florida, United States.

History

The laboratory has its origins in Gulf Specimen Marine Company, ...

in Florida. Their correspondence continued until Steinbeck's death.

In 1966, Steinbeck traveled to Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

to visit the site of Mount Hope, a farm community established in Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

by his grandfather, whose brother, Friedrich Großsteinbeck, was murdered by Arab marauders in 1858 in what became known as the Outrages at Jaffa

On January 11, 1858, the Jaffa Colonists – part of the American Agricultural Mission to assist local residents in agricultural endeavors in Ottoman Palestine – were brutally attacked, creating an international incident at the beginnings of U. ...

.

Death and legacy

John Steinbeck died in New York City on December 20, 1968, during the 1968 flu pandemic of

John Steinbeck died in New York City on December 20, 1968, during the 1968 flu pandemic of heart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, h ...

and congestive heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, ...

. He was 66, and had been a lifelong smoker. An autopsy showed nearly complete occlusion of the main coronary arteries.

In accordance with his wishes, his body was cremated, and interred on March 4, 1969 at the Hamilton family gravesite in Salinas, with those of his parents and maternal grandparents. His third wife, Elaine, was buried in the plot in 2004. He had written to his doctor that he felt deeply "in his flesh" that he would not survive his physical death, and that the biological end of his life was the final end to it.

Steinbeck's incomplete novel based on the King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

legends of Malory and others, ''The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights

''The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights'' (1976) is John Steinbeck's retelling of the Arthurian legend, based on the Winchester Manuscript text of Sir Thomas Malory's '' Le Morte d'Arthur''. He began his adaptation in November 1956. Stei ...

'', was published in 1976.

Many of Steinbeck's works are required reading in American high schools. In the United Kingdom, ''Of Mice and Men'' is one of the key texts used by the examining body AQA

AQA, formerly the Assessment and Qualifications Alliance, is an awarding body in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It compiles specifications and holds examinations in various subjects at GCSE, AS and A Level and offers vocational q ...

for its English Literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

GCSE

The General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) is an academic qualification in a particular subject, taken in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. State schools in Scotland use the Scottish Qualifications Certificate instead. Private sc ...

. A study by the Center for the Learning and Teaching of Literature in the United States found that ''Of Mice and Men'' was one of the ten most frequently read books in public high schools. Contrariwise, Steinbeck's works have been frequently banned in the United States. ''The Grapes of Wrath'' was banned