Stanley Holloway on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Stanley Augustus Holloway (1 October 1890 – 30 January 1982) was an English actor, comedian, singer and monologist. He was famous for his comic and character roles on stage and screen, especially that of Alfred P. Doolittle in ''

Stanley Augustus Holloway (1 October 1890 – 30 January 1982) was an English actor, comedian, singer and monologist. He was famous for his comic and character roles on stage and screen, especially that of Alfred P. Doolittle in ''

"Holloway, Stanley Augustus (1890–1982)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, online edition, January 2011, accessed 21 April 2011 He was named after

1841 census, accessed 23 April 2011 Augustus became a wealthy shopkeeper, with a brush-making business. He married Amelia Catherine Knight in September 1856, and they had three children, Maria, Charles and George. In the early 1880s the family moved to

''Oxford Encyclopedia of Popular Music'', Oxford University Press, 2006, online edition, accessed 5 December 2011 From June 1921, Holloway had considerable success in '' The Co-Optimists'', a concert party formed with performers whom he had met during the war in France, which ''

"Stanley Holloway: Old Sam and Young Albert Original 1930–1940 Recordings"

"About this Album", ClassicsOnline, accessed 5 December 2011 In the monologue, Mr. and Mrs. Ramsbottom react in a measured way when their son Albert is swallowed. Neither Edgar nor Holloway was convinced that the piece would succeed, but needing material for an appearance at a Northern Rugby League dinner Holloway decided to perform it.Holloway and Richards, p. 91 It was well received, and Holloway introduced it into his stage act. Subsequently, Edgar wrote 16 monologues for him. In its obituary of Holloway, ''The Times'' wrote that Sam and Albert "became part of English folklore during the 1930s, and they remained so during the Second World War." These monologues employed the Holloway style that has been called "the understated look-on-the-bright-side world of the cockney working class. ... Holloway's characters are ischievous, like Albert, orobstinate, and hilariously clueless. He often told his stories in costume; sporting outrageous attire and bushy moustaches." In 1932 Harry S. Pepper, with Holloway and others, revived the White Coons Concert Party show for

, Imperial War Museum, accessed 22 April 2011; an

, Play.com, accessed 22 April 2011 and ''Worker and Warfront No.8'' (1943), with a script written by

''Who Was Who'', A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edition, Oxford University Press, December 2007, accessed 21 April 2011 After the war, he played Albert Godby in ''

In 1954 Holloway joined

In 1954 Holloway joined  Looking back in 2004, Holloway's biographer Eric Midwinter wrote, "With his cockney authenticity, his splendid baritone voice, and his wealth of comedy experience, he made a great success of this role, and, as he said, it put him 'bang on top of the heap, in demand' again at a time when, in his mid-sixties, his career was beginning to wane". His performances earned him a

Looking back in 2004, Holloway's biographer Eric Midwinter wrote, "With his cockney authenticity, his splendid baritone voice, and his wealth of comedy experience, he made a great success of this role, and, as he said, it put him 'bang on top of the heap, in demand' again at a time when, in his mid-sixties, his career was beginning to wane". His performances earned him a

Holloway appeared for the first time in a major British television series in the BBC's 1967 adaptation of P. G. Wodehouse's '' Blandings Castle'' stories, playing Beach, the butler, to

Holloway appeared for the first time in a major British television series in the BBC's 1967 adaptation of P. G. Wodehouse's '' Blandings Castle'' stories, playing Beach, the butler, to

British Film Institute, accessed 24 November 2011 In 1970, Holloway began an association with the Shaw Festival in Canada, playing Burgess in '' Candida''. He made what he considered his West End debut as a straight actor in ''Siege'' by

"Stanley Holloway. Concert Party"

''The Gramophone'', October 1961, p. 72

Stanley Holloway pictures on Getty images

Stanley Holloway monologue lyrics

Stanley Holloway on British Pathe News

{{DEFAULTSORT:Holloway, Stanley 1890 births 1982 deaths British Army personnel of World War I British expatriate male actors in the United States British male comedy actors British propagandists Connaught Rangers officers English male comedians English male film actors English male musical theatre actors English male stage actors English male television actors Male actors from London Officers of the Order of the British Empire People from East Ham People from East Preston, West Sussex People from Manor Park, London People of the Easter Rising 20th-century English comedians 20th-century English male actors 20th-century English male singers 20th-century English singers London Rifle Brigade soldiers Military personnel from Essex

Stanley Augustus Holloway (1 October 1890 – 30 January 1982) was an English actor, comedian, singer and monologist. He was famous for his comic and character roles on stage and screen, especially that of Alfred P. Doolittle in ''

Stanley Augustus Holloway (1 October 1890 – 30 January 1982) was an English actor, comedian, singer and monologist. He was famous for his comic and character roles on stage and screen, especially that of Alfred P. Doolittle in ''My Fair Lady

''My Fair Lady'' is a musical based on George Bernard Shaw's 1913 play '' Pygmalion'', with a book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe. The story concerns Eliza Doolittle, a Cockney flower girl who takes speech lessons ...

''. He was also renowned for his comic monologues and songs, which he performed and recorded throughout most of his 70-year career.

Born in London, Holloway pursued a career as a clerk in his teen years. He made early stage appearances before infantry service in the First World War, after which he had his first major theatre success starring in ''Kissing Time

''Kissing Time'', and an earlier version titled ''The Girl Behind the Gun'', are musical comedies with music by Ivan Caryll, book and lyrics by Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse, and additional lyrics by Clifford Grey. The story is based on the 1910 ...

'' when the musical transferred to the West End from Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

. In 1921, he joined a concert party, '' The Co-Optimists'', and his career began to flourish. At first, he was employed chiefly as a singer, but his skills as an actor and reciter of comic monologues were soon recognised. Characters from his monologues such as Sam Small, invented by Holloway, and Albert Ramsbottom, created for him by Marriott Edgar

Marriott Edgar (5 October 1880 – 5 May 1951), born George Marriott Edgar in Kirkcudbright, Scotland, was a British poet, scriptwriter and comedian, best known for writing many of the monologues performed by Stanley Holloway, particularly the ...

, were absorbed into popular British culture, and Holloway developed a following for the recordings of his many monologues. By the 1930s, he was in demand to star in variety

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

, pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speakin ...

and musical comedy, including several revue

A revue is a type of multi-act popular theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance, and sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural presence of its own dur ...

s.

Following the outbreak of the Second World War, Holloway made short propaganda films on behalf of the British Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery to encourage film production, ...

and Pathé News

Pathé News was a producer of newsreels and documentaries from 1910 to 1970 in the United Kingdom. Its founder, Charles Pathé, was a pioneer of moving pictures in the silent era. The Pathé News archive is known today as British Pathé. Its col ...

and took character parts in a series of war films including ''Major Barbara

''Major Barbara'' is a three-act English play by George Bernard Shaw, written and premiered in 1905 and first published in 1907. The story concerns an idealistic young woman, Barbara Undershaft, who is engaged in helping the poor as a Major in ...

'', '' The Way Ahead'', '' This Happy Breed'' and '' The Way to the Stars''. After the war, he appeared in the film ''Brief Encounter

''Brief Encounter'' is a 1945 British romantic drama film directed by David Lean from a screenplay by Noël Coward, based on his 1936 one-act play ''Still Life''.

Starring Celia Johnson, Trevor Howard, Stanley Holloway, and Joyce Carey, ...

'' and made a series of films for Ealing Studios, including '' Passport to Pimlico'', ''The Lavender Hill Mob

''The Lavender Hill Mob'' is a 1951 comedy film from Ealing Studios, written by T. E. B. Clarke, directed by Charles Crichton, starring Alec Guinness and Stanley Holloway and featuring Sid James and Alfie Bass. The title refers to Lavend ...

'' and '' The Titfield Thunderbolt''.

In 1956 he was cast as the irresponsible and irrepressible Alfred P. Doolittle in ''My Fair Lady'', a role that he played on Broadway, the West End and in the film version in 1964. The role brought him international fame, and his performances earned him nominations for a Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Musical and an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor

The Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given in honor of an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a supporting role while worki ...

. In his later years, Holloway appeared in television series in the UK and the US, toured in revues, appeared in stage plays in Britain, Canada, Australia and the US, and continued to make films into his eighties. Holloway was married twice and had five children, including the actor Julian Holloway.

Biography

Family background and early life

Holloway was born in Manor Park,Essex

Essex () is a Ceremonial counties of England, county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the Riv ...

(now in the London Borough of Newham

The London Borough of Newham is a London borough created in 1965 by the London Government Act 1963. It covers an area previously administered by the Essex county boroughs of West Ham and East Ham, authorities that were both abolished by the s ...

), the younger child and only son of George Augustus Holloway (1860–1919), a lawyer's clerk, and Florence May ''née'' Bell (1862–1913), a housekeeper and dressmaker.Midwinter, Eric"Holloway, Stanley Augustus (1890–1982)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, online edition, January 2011, accessed 21 April 2011 He was named after

Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author and politician who was famous for his exploration of Central Africa and his sear ...

, the journalist and explorer famous for his exploration of Africa and for his search for David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

. There were theatrical connections in the Holloway family going back to Charles Bernard (1830–1894), an actor and theatre manager, who was the brother of Holloway's maternal grandmother.Holloway and Richards, pp. 74–75

Holloway's paternal grandfather was Augustus Holloway (1829–1884),Principal Probate Registry, ''Calendar of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration made in the Probate Registries of the High Court of Justice of England'', p. 418 brought up in Poole

Poole () is a large coastal town and seaport in Dorset, on the south coast of England. The town is east of Dorchester and adjoins Bournemouth to the east. Since 1 April 2019, the local authority is Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Counc ...

, Dorset."Poole St James"1841 census, accessed 23 April 2011 Augustus became a wealthy shopkeeper, with a brush-making business. He married Amelia Catherine Knight in September 1856, and they had three children, Maria, Charles and George. In the early 1880s the family moved to

Poplar, London

Poplar is a district in East London, England, the administrative centre of the borough of Tower Hamlets. Five miles (8 km) east of Charing Cross, it is part of the East End.

It is identified as a major district centre in the London Plan ...

. When Augustus died, George Holloway (Stanley's father) moved to nearby Manor Park and became a clerk for a city lawyer, Robert Bell.Holloway and Richards, p. 42 George married Bell's daughter Florence in 1884, and they had two children, Millie (1887–1949) and Stanley. George left Florence in 1905 and was never seen or heard from again by his family.Holloway and Richards, p. 68

During his early teenage years, Holloway attended the Worshipful School of Carpenters in nearby StratfordHolloway and Richards, pp. 42–43 and joined a local choir, which he later called his "big moment". He left school at the age of 14 and worked as a junior clerk in a boot polish factory, where he earned ten shillings a week.Holloway and Richards, p. 46 He began performing part-time as ''Master Stanley Holloway – The Wonderful Boy Soprano'' from 1904, singing sentimental songs such as " The Lost Chord". A year later, he became a clerk at Billingsgate Fish Market

Billingsgate Fish Market is located in Canary Wharf in London. It is the United Kingdom's largest inland fish market. It takes its name from Billingsgate, a ward in the south-east corner of the City of London, where the riverside market was or ...

, where he remained for two years before commencing training as an infantry soldier in the London Rifle Brigade in 1907.Holloway and Richards, p. 58

Career

Early career and First World War

Holloway's stage career began in 1910, when he travelled to Walton-on-the-Naze to audition for ''The White Coons Show'', a concert partyvariety show

Variety show, also known as variety arts or variety entertainment, is entertainment made up of a variety of acts including musical performances, sketch comedy, magic, acrobatics, juggling, and ventriloquism. It is normally introduced by a co ...

arranged and produced by Will C. Pepper, father of Harry S. Pepper, with whom Holloway later starred in '' The Co-Optimists''.Holloway and Richards, p. 49 This seaside show lasted six weeks.Holloway and Richards, p. 50 From 1912 to 1914, Holloway appeared in the summer seasons at the West Cliff Gardens Theatre, Clacton-on-Sea

Clacton-on-Sea is a seaside town in the Tendring District in the county of Essex, England. It is located on the Tendring Peninsula and is the largest settlement in the Tendring District with a population of 56,874 (2016). The town is situated ...

, where he was billed as a romantic baritone.

In 1913 Holloway was recruited by the comedian Leslie Henson

Leslie Lincoln Henson (3 August 1891 – 2 December 1957) was an English comedian, actor, producer for films and theatre, and film director. He initially worked in silent films and Edwardian musical comedy and became a popular music hall comed ...

to feature as a support in Henson's more prestigious concert party called ''Nicely, Thanks''. In later life, Holloway often spoke of his admiration for Henson, citing him as a great influence on his career. The two became firm friends and often consulted each other before taking jobs. In his 1967 autobiography, Holloway dedicated a whole chapter to Henson, whom he described as "the greatest friend, inspiration and mentor a performer could have had". Later in 1913, Holloway decided to train as an operatic baritone

A baritone is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the bass and the tenor voice-types. The term originates from the Greek (), meaning "heavy sounding". Composers typically write music for this voice in the ...

, and so he went to Italy to take singing lessons from Ferdinando Guarino in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

. However, a yearning to start a career in light entertainment and a contract to re-appear in Bert Graham and Will Bentley's concert party at the West Cliff Theatre caused him to return home after six months.

In the early months of 1914, Holloway made his first visit to the United States and then went to Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

and Valparaíso

Valparaíso (; ) is a major city, seaport, naval base, and educational centre in the commune of Valparaíso, Chile. "Greater Valparaíso" is the second largest metropolitan area in the country. Valparaíso is located about northwest of Santiago ...

with the concert party ''The Grotesques''. At the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, he decided to return to England, but his departure was delayed for six weeks due to his contract with the troupe. At the age of 25, Holloway enlisted in the Connaught Rangers

The Connaught Rangers ("The Devil's Own") was an Irish line infantry regiment of the British Army formed by the amalgamation of the 88th Regiment of Foot (Connaught Rangers) (which formed the ''1st Battalion'') and the 94th Regiment of Foot (wh ...

in which he was commissioned as a subaltern in December 1915 because of his previous training in the London Rifle Brigade. In 1916 he was stationed in Cork and fought against the rebels in the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with t ...

. Later that year, he was sent to France, where he fought in the trenches alongside Michael O'Leary, who was awarded the Victoria Cross

The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest and most prestigious award of the British honours system. It is awarded for valour "in the presence of the enemy" to members of the British Armed Forces and may be awarded posthumously. It was previousl ...

for gallantryHolloway and Richards, p. 60 in February 1915. Holloway and O'Leary stayed in touch after the war and remained close friends.

Holloway spent much of his time in the later part of the war organising shows to boost army morale in France. One such revue

A revue is a type of multi-act popular theatrical entertainment that combines music, dance, and sketches. The revue has its roots in 19th century popular entertainment and melodrama but grew into a substantial cultural presence of its own dur ...

, ''Wear That Ribbon'', was performed in honour of O'Leary winning the VC. He, Henson and his newly established ''Star Attractions'' concert party, entertained the British troops in Wimereux. The party included such performers as Jack Buchanan, Eric Blore

Eric Blore Sr. (23 December 1887 – 2 March 1959) was an English actor and writer. His early stage career, mostly in the West End of London, centred on revue and musical comedy, but also included straight plays. He wrote sketches for and appe ...

, Binnie Hale

Beatrice "Binnie" Mary Hale-Monro (22 May 1899 – 10 January 1984) was an English actress, singer and dancer. She was one of the most successful musical theatre stars in London in the 1920s and 1930s, able to sing leading roles in operetta a ...

, and Phyllis Dare

Phyllis is a feminine given name which may refer to:

People

* Phyllis Bartholomew (1914–2002), English long jumper

* Phyllis Drummond Bethune (née Sharpe, 1899–1982), New Zealand artist

* Phyllis Calvert (1915–2002), British actress

* P ...

, as well as the performers who would later form ''The Co-Optimists''.Holloway and Richards, p. 20 Upon his return from France, Holloway was stationed in Hartlepool

Hartlepool () is a seaside and port town in County Durham, England. It is the largest settlement and administrative centre of the Borough of Hartlepool. With an estimated population of 90,123, it is the second-largest settlement in County D ...

,Holloway and Richards, p. 76 and immediately after the war ended he starred in ''The Disorderly Room'' with Leslie Henson, which Eric Blore had written while serving in the South Wales Borderers. The production toured theatres on England's coast, including Walton-on-the-Naze and Clacton-on-Sea

Clacton-on-Sea is a seaside town in the Tendring District in the county of Essex, England. It is located on the Tendring Peninsula and is the largest settlement in the Tendring District with a population of 56,874 (2016). The town is situated ...

.

Inter-war years

After relinquishing his army commission in May 1919, Holloway returned to London and resumed his singing and acting career, finding success in two West End musicals at theWinter Garden Theatre

The Winter Garden Theatre is a Broadway theatre at 1634 Broadway in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It opened in 1911 under designs by architect William Albert Swasey. The Winter Garden's current design dates to 1922, when ...

. Later that month, he created the role of Captain Wentworth in Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse's ''Kissing Time

''Kissing Time'', and an earlier version titled ''The Girl Behind the Gun'', are musical comedies with music by Ivan Caryll, book and lyrics by Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse, and additional lyrics by Clifford Grey. The story is based on the 1910 ...

'', followed in 1920 by the role of René in '' A Night Out''. Following its provincial success, ''The Disorderly Room'' was given a West End production at the Victoria Palace Theatre

The Victoria Palace Theatre is a West End theatre in Victoria Street, in the City of Westminster, opposite Victoria Station. The structure is categorised as a Grade II* listed building.

History Origins

The theatre began life as a small conc ...

in late 1919, in which Holloway starred alongside Henson and Tom Walls

Thomas Kirby Walls (18 February 1883 – 27 November 1949) was an English stage and film actor, producer and director, best known for presenting and co-starring in the Aldwych farces in the 1920s and for starring in and directing the film adapt ...

. Holloway made his film debut in a 1921 silent comedy called ''The Rotters''."Holloway, Stanley Augustus (1890–1982)"''Oxford Encyclopedia of Popular Music'', Oxford University Press, 2006, online edition, accessed 5 December 2011 From June 1921, Holloway had considerable success in '' The Co-Optimists'', a concert party formed with performers whom he had met during the war in France, which ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' called "an all-star 'pierrot

Pierrot ( , , ) is a stock character of pantomime and '' commedia dell'arte'', whose origins are in the late seventeenth-century Italian troupe of players performing in Paris and known as the Comédie-Italienne. The name is a diminutive of ''Pi ...

' entertainment in the West-end." It opened at the small Royalty Theatre and soon transferred to the much larger Palace Theatre Palace Theatre, or Palace Theater, is the name of many theatres in different countries, including:

Australia

* Palace Theatre, Melbourne, Victoria

*Palace Theatre, Sydney, New South Wales

Canada

*Palace Theatre, housed in the Robillard Block, M ...

, where the initial version of the show ran for over a year, giving more than 500 performances.Holloway and Richards, p. 29 The entertainment was completely rewritten at regular intervals to keep it fresh, and the final edition, beginning in November 1926, was the 13th version. ''The Co-Optimists'' closed in 1927 at His Majesty's Theatre after 1,568 performances over eight years. In 1929, a feature film version was made, with Holloway rejoining his former co-stars.

In 1923 Holloway established himself as a BBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

performer. The early BBC broadcasts brought variety and classical artists together, and Holloway could be heard in the same programme as the cellist John Barbirolli or the Band of the Scots Guards. He developed his solo act throughout the 1920s while continuing his involvement with the musical theatre and ''The Co-Optimists''. In 1924 he made his first gramophone discs, recording for HMV two songs from ''The Co-Optimists'': "London Town" and "Memory Street". After ''The Co-Optimists'' disbanded in 1927, Holloway played at the London Hippodrome

The Hippodrome is a building on the corner of Cranbourn Street and Charing Cross Road in the City of Westminster, London. The name was used for many different theatres and music halls, of which the London Hippodrome is one of only a few s ...

in Vincent Youmans

Vincent Millie Youmans (September 27, 1898 – April 5, 1946) was an American Broadway composer and producer.

A leading Broadway composer of his day, Youmans collaborated with virtually all the greatest lyricists on Broadway: Ira Gershwin, ...

's musical comedy '' Hit the Deck'' as Bill Smith, a performance judged by ''The Times'' to be "invested with many shrewd touches of humanity". In ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the G ...

'', Ivor Brown

Ivor John Carnegie Brown CBE (25 April 1891 – 22 April 1974) was a British journalist and man of letters.

Biography

Born in Penang, Malaya, Brown was the younger of two sons of Dr. William Carnegie Brown, a specialist in tropical diseases, ...

praised him for a singing style "which coaxes the ear rather than clubbing the head."

Holloway began regularly performing monologues, both on stage and on record, in 1928, with his own creation, Sam Small, in ''Sam, Sam, Pick oop thy Musket''. Over the following years, he recorded more than 20 monologues based around the character, most of which he wrote himself. He created Sam Small after Henson had returned from a tour of northern England and told him a story about an insubordinate old soldier from the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armies of the Sevent ...

.Holloway and Richards, p. 83 Holloway developed the character, naming him after a Cockney friend of Henson called Annie Small;Holloway and Richards, p. 85 the name Sam was chosen at random. Holloway adopted a northern accent for the character. ''The Times'' commented, "For absolute delight ... there is nothing to compare with Mr. Stanley Holloway's monologue, concerning a military contretemps on the eve of Waterloo ... perfect, even to the curled moustache and the Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

accent of the stubborn Guardsman hero."

In 1929 Holloway played another leading role in musical comedy, Lieutenant Richard Manners in ''Song of the Sea'', and later that year he performed in the revue ''Coo-ee'', with Billy Bennett, Dorothy Dickson

Dorothy Dickson (July 25, 1893 – September 25, 1995) was an American-born, London-based theater actress and singer, and a centenarian.

Biography and Career

Dickson is known mostly for her rendition of the Jerome Kern song "Look for the S ...

and Claude Hulbert. When ''The Co-Optimists'' re-formed in 1930, he rejoined that company, now at the Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre was designed by C. J. Phipps for Richard D'Oyly Carte and opened on 10 October 1881 on a site previously occupied by the Savoy P ...

, and at the same venue appeared in ''Savoy Follies'' in 1931,Gaye, p. 746 where he introduced to London audiences the monologue ''The Lion and Albert''. The monologue was written by Marriott Edgar

Marriott Edgar (5 October 1880 – 5 May 1951), born George Marriott Edgar in Kirkcudbright, Scotland, was a British poet, scriptwriter and comedian, best known for writing many of the monologues performed by Stanley Holloway, particularly the ...

, who based the story on a news item about a boy who was eaten by a lion in the zoo.Ginell, Cary"Stanley Holloway: Old Sam and Young Albert Original 1930–1940 Recordings"

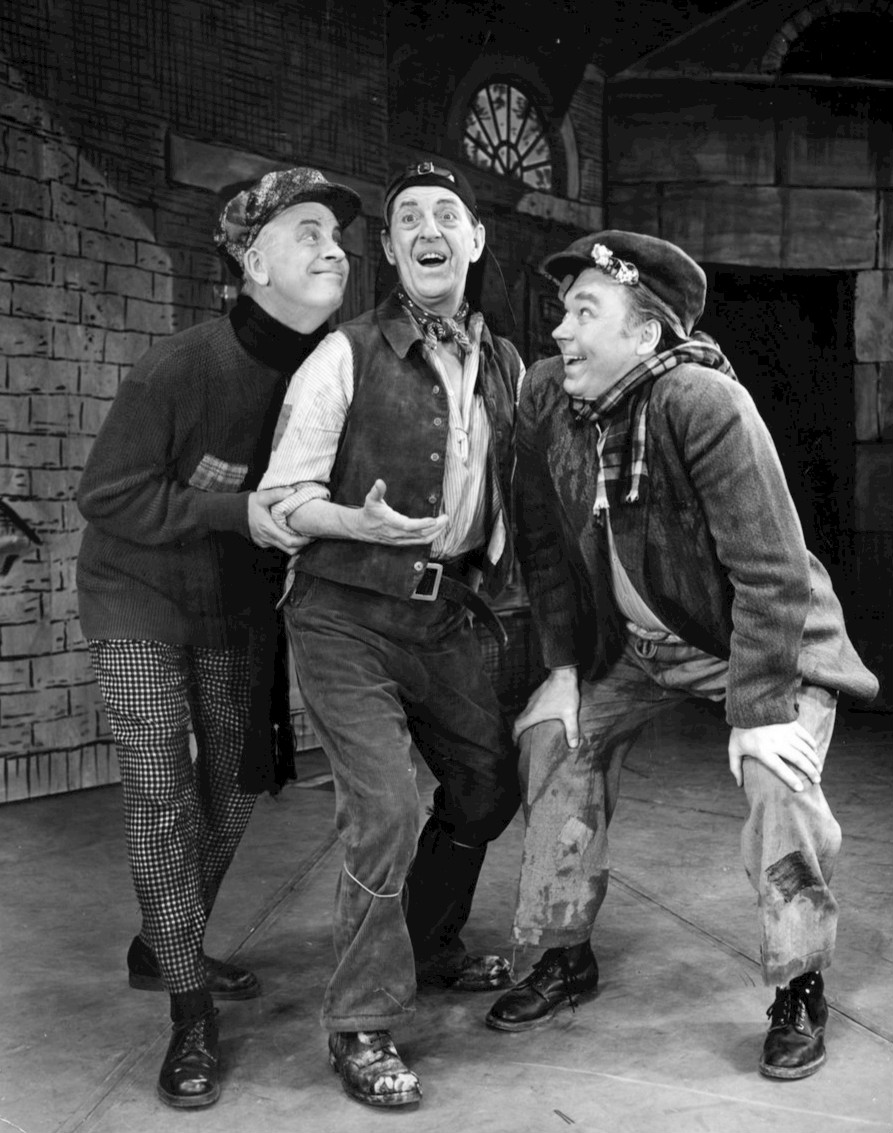

"About this Album", ClassicsOnline, accessed 5 December 2011 In the monologue, Mr. and Mrs. Ramsbottom react in a measured way when their son Albert is swallowed. Neither Edgar nor Holloway was convinced that the piece would succeed, but needing material for an appearance at a Northern Rugby League dinner Holloway decided to perform it.Holloway and Richards, p. 91 It was well received, and Holloway introduced it into his stage act. Subsequently, Edgar wrote 16 monologues for him. In its obituary of Holloway, ''The Times'' wrote that Sam and Albert "became part of English folklore during the 1930s, and they remained so during the Second World War." These monologues employed the Holloway style that has been called "the understated look-on-the-bright-side world of the cockney working class. ... Holloway's characters are ischievous, like Albert, orobstinate, and hilariously clueless. He often told his stories in costume; sporting outrageous attire and bushy moustaches." In 1932 Harry S. Pepper, with Holloway and others, revived the White Coons Concert Party show for

BBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

.

Beginning in 1934, Holloway appeared in a series of British films, three of which featured his creation Sam Small. He started his association with the filmmakers Ealing Studios

Ealing Studios is a television and film production company and facilities provider at Ealing Green in West London. Will Barker bought the White Lodge on Ealing Green in 1902 as a base for film making, and films have been made on the site ever ...

in 1934, appearing in the fifth Gracie Fields

Dame Gracie Fields (born Grace Stansfield; 9 January 189827 September 1979) was an English actress, singer, comedian and star of cinema and music hall who was one of the top ten film stars in Britain during the 1930s and was considered the h ...

picture ''Sing As We Go

''Sing As We Go'' is a 1934 British musical film starring Gracie Fields, John Loder and Stanley Holloway. The script was written by Gordon Wellesley and J. B. Priestley.

Considered by many to be British music hall star Gracie Fields' finest ...

''. His other films from the 1930s included ''Squibs'' (1935) and ''The Vicar of Bray

The Vicar of Bray is a satirical description of an individual fundamentally changing his principles to remain in ecclesiastical office as external requirements change around him. The religious upheavals in England from 1533 to 1559 (and then from ...

'' (1937). In December 1934, Holloway made his first appearance in pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment. It was developed in England and is performed throughout the United Kingdom, Ireland and (to a lesser extent) in other English-speakin ...

, playing Abanazar in ''Aladdin

Aladdin ( ; ar, علاء الدين, ', , ATU 561, ‘Aladdin') is a Middle-Eastern folk tale. It is one of the best-known tales associated with ''The Book of One Thousand and One Nights'' (''The Arabian Nights''), despite not being part o ...

''. In his first season in the part, he was overshadowed by his co-star, Sir Henry Lytton, as the Emperor, but he quickly became established as a favourite in his role, playing it in successive years in Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popul ...

, London, Edinburgh and Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The ...

.

Second World War and post-war

On the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 Holloway, who was 49, was too old for active service. Instead, he appeared in short propaganda pieces for theBritish Film Institute

The British Film Institute (BFI) is a film and television charitable organisation which promotes and preserves film-making and television in the United Kingdom. The BFI uses funds provided by the National Lottery to encourage film production, ...

and Pathé News

Pathé News was a producer of newsreels and documentaries from 1910 to 1970 in the United Kingdom. Its founder, Charles Pathé, was a pioneer of moving pictures in the silent era. The Pathé News archive is known today as British Pathé. Its col ...

. He narrated documentaries aimed at lifting morale in war-torn Britain, including ''Albert's Savings'' (1940), written by Marriott Edgar and featuring the character Albert Ramsbottom,"Britain's Home Front at War: Words for Battle", Imperial War Museum, accessed 22 April 2011; an

, Play.com, accessed 22 April 2011 and ''Worker and Warfront No.8'' (1943), with a script written by

E. C. Bentley

Edmund Clerihew Bentley (10 July 1875 – 30 March 1956), who generally published under the names E. C. Bentley or E. Clerihew Bentley, was a popular English novelist and humorist, and inventor of the clerihew, an irregular form of humorous verse ...

about a worker who neglects to have an injury examined and contracts blood poisoning. Both films were included on a 2007 Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museums (IWM) is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, the museum was intended to record the civil and military ...

DVD ''Britain's Home Front at War: Words for Battle.''

On stage during the war years, Holloway appeared in revues, first ''Up and Doing'', with Henson, Binnie Hale

Beatrice "Binnie" Mary Hale-Monro (22 May 1899 – 10 January 1984) was an English actress, singer and dancer. She was one of the most successful musical theatre stars in London in the 1920s and 1930s, able to sing leading roles in operetta a ...

and Cyril Ritchard

Cyril Joseph Trimnell-Ritchard (1 December 1898 – 18 December 1977), known professionally as Cyril Ritchard, was an Australian stage, screen and television actor, and director. He is best remembered today for his performance as Captain Hook in ...

in 1940 and 1941, and then ''Fine and Dandy'', with Henson, Dorothy Dickson

Dorothy Dickson (July 25, 1893 – September 25, 1995) was an American-born, London-based theater actress and singer, and a centenarian.

Biography and Career

Dickson is known mostly for her rendition of the Jerome Kern song "Look for the S ...

, Douglas Byng and Graham Payn. In both shows, Holloway presented new monologues, and ''The Times'' thought a highlight of ''Fine and Dandy'' was a parody of the BBC radio programme ''The Brains Trust

''The Brains Trust'' was an informational BBC radio and later television programme popular in the United Kingdom during the 1940s and 1950s, on which a panel of experts tried to answer questions sent in by the audience.

History

The series was ...

'', with Holloway "ponderously anecdotal" and Henson "gigglingly omniscient".

In 1941 Holloway took a character part in Gabriel Pascal's film of Bernard Shaw's ''Major Barbara

''Major Barbara'' is a three-act English play by George Bernard Shaw, written and premiered in 1905 and first published in 1907. The story concerns an idealistic young woman, Barbara Undershaft, who is engaged in helping the poor as a Major in ...

'', in which he played a policeman. He had leading parts in later films, including '' The Way Ahead'' (1944), '' This Happy Breed'' (1944) and '' The Way to the Stars'' (1945)."Holloway, Stanley"''Who Was Who'', A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edition, Oxford University Press, December 2007, accessed 21 April 2011 After the war, he played Albert Godby in ''

Brief Encounter

''Brief Encounter'' is a 1945 British romantic drama film directed by David Lean from a screenplay by Noël Coward, based on his 1936 one-act play ''Still Life''.

Starring Celia Johnson, Trevor Howard, Stanley Holloway, and Joyce Carey, ...

'' and had a cameo role as the First Gravedigger in Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage ...

's 1948 film of ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

''. In 1951 Holloway played the same role on the stage to the Hamlet of Alec Guinness

Sir Alec Guinness (born Alec Guinness de Cuffe; 2 April 1914 – 5 August 2000) was an English actor. After an early career on the stage, Guinness was featured in several of the Ealing comedies, including '' Kind Hearts and Coronets'' (1 ...

. For Pathé News, he delivered the commentary for documentaries in a series called ''Time To Remember'', where he narrated over old newsreels from significant dates in history from 1915 to 1942. Holloway also starred in a series of films for Ealing Studios, beginning with '' Champagne Charlie'' in 1944 alongside Tommy Trinder

Thomas Edward Trinder CBE (24 March 1909 – 10 July 1989) was an English stage, screen and radio comedian whose catchphrase was "You lucky people!". Described by cultural historian Matthew Sweet as "a cocky, front-of-cloth variety turn", he ...

. After that he made ''Nicholas Nickleby

''Nicholas Nickleby'' or ''The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby'' (or also ''The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, Containing a Faithful Account of the Fortunes, Misfortunes, Uprisings, Downfallings, and Complete Career of the ...

'' (1947) and ''Another Shore

''Another Shore'' is a 1948 Ealing Studios comedy film directed by Charles Crichton. It stars Robert Beatty as Gulliver Shields, an Irish customs official who dreams of living on a South Sea island; particularly Rarotonga. It is based on the 1 ...

'' (1948). He next appeared in three of the most famous Ealing Comedies, '' Passport to Pimlico'' (1949), ''The Lavender Hill Mob

''The Lavender Hill Mob'' is a 1951 comedy film from Ealing Studios, written by T. E. B. Clarke, directed by Charles Crichton, starring Alec Guinness and Stanley Holloway and featuring Sid James and Alfie Bass. The title refers to Lavend ...

'' (1951) and '' The Titfield Thunderbolt'' (1953). His final film with the studio was '' Meet Mr. Lucifer'' (1953).

In 1948 Holloway conducted a six-month tour of Australia and New Zealand and supported by the band leader Billy Mayerl

William Joseph Mayerl (31 May 1902 – 25 March 1959) was an English pianist and composer who built a career in music hall and musical theatre and became an acknowledged master of light music. Best known for his syncopated novelty piano solo ...

. He made his Australian début at The Tivoli Theatre, Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

, and recorded television appearances to publicise the forthcoming release of ''Passport to Pimlico''. Holloway wrote the monologue ''Albert Down Under'' especially for the tour.

1950s and 1960s stage and screen

the Old Vic

The Old Vic is a 1,000-seat, not-for-profit producing theatre in Waterloo, London, England. Established in 1818 as the Royal Coburg Theatre, and renamed in 1833 the Royal Victoria Theatre. In 1871 it was rebuilt and reopened as the Royal ...

theatre company to play Bottom in ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict a ...

'', with Robert Helpmann as Oberon and Moira Shearer

Moira Shearer King, Lady Kennedy (17 January 1926 – 31 January 2006), was an internationally renowned Scottish ballet dancer and actress. She was famous for her performances in Powell and Pressburger's '' The Red Shoes'' (1948) and '' The Ta ...

as Titania. After playing at the Edinburgh Festival

__NOTOC__

This is a list of arts and cultural festivals regularly taking place in Edinburgh, Scotland.

The city has become known for its festivals since the establishment in 1947 of the Edinburgh International Festival and the Edinburgh F ...

, the Royal Shakespeare Company

The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) is a major British theatre company, based in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The company employs over 1,000 staff and produces around 20 productions a year. The RSC plays regularly in London, St ...

took the production to New York, where it played at the Metropolitan Opera House and then on tour of the US and Canada. The production was harshly reviewed by critics on both sides of the Atlantic, but Holloway made a strong impression. Holloway said of the experience: "Out of the blue I was asked by the Royal Shakespeare Company to tour America with them, playing Bottom. ... From that American tour came the part of Alfred Doolittle in ''My Fair Lady

''My Fair Lady'' is a musical based on George Bernard Shaw's 1913 play '' Pygmalion'', with a book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe. The story concerns Eliza Doolittle, a Cockney flower girl who takes speech lessons ...

'' and from then on, well, just let's say I was able to pick and choose my parts and that was very pleasant at my age." Holloway's film career continued simultaneously with his stage work; one example was the 1956 comedy '' Jumping for Joy''. American audiences became familiar with his earlier film roles when the films began to be broadcast on television in the 1950s.

In 1956 Holloway created the role of Alfred P. Doolittle in the original Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

production of ''My Fair Lady

''My Fair Lady'' is a musical based on George Bernard Shaw's 1913 play '' Pygmalion'', with a book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe. The story concerns Eliza Doolittle, a Cockney flower girl who takes speech lessons ...

''. The librettist, Alan Jay Lerner

Alan Jay Lerner (August 31, 1918 – June 14, 1986) was an American lyricist and librettist. In collaboration with Frederick Loewe, and later Burton Lane, he created some of the world's most popular and enduring works of musical theatre b ...

, remembered in his memoirs that Holloway was his first choice for the role, even before it was written. Lerner's only concern was whether, after so long away from the musical stage, Holloway still had his resonant singing voice. Holloway reassured him over a lunch at Claridge's

Claridge's is a 5-star hotel at the corner of Brook Street and Davies Street in Mayfair, London. It has long-standing connections with royalty that have led to it sometimes being referred to as an "annexe to Buckingham Palace". Claridge's Hot ...

: Lerner recalled, "He put down his knife and fork, threw back his head and unleashed a strong baritone note that resounded through the dining room, drowned out the string quartet and sent a few dozen people off to the osteopath to have their necks untwisted." Holloway had a long association with the show, appearing in the original 1956 Broadway production at the Mark Hellinger Theatre

The Mark Hellinger Theatre (formerly the 51st Street Theatre and the Hollywood Theatre) is a church building at 237 West 51st Street in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, which formerly served as a cinema and a Broadway theat ...

, the 1958 London version at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

, and the film version in 1964, which he undertook instead of the role of Admiral Boom in ''Mary Poppins It may refer to:

* ''Mary Poppins'' (book series), the original 1934–1988 children's fantasy novels that introduced the character.

* Mary Poppins (character), the nanny with magical powers.

* ''Mary Poppins'' (film), a 1964 Disney film star ...

'' that he had been offered the same year. In ''The Manchester Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the G ...

'', Alistair Cooke

Alistair Cooke (born Alfred Cooke; 20 November 1908 – 30 March 2004) was a British-American writer whose work as a journalist, television personality and radio broadcaster was done primarily in the United States.Hallmark Hall of Fame

''Hallmark Hall of Fame'', originally called ''Hallmark Television Playhouse'', is an anthology program on American television, sponsored by Hallmark Cards, a Kansas City-based greeting card company. The longest-running prime-time series in ...

television production of '' The Fantasticks''.

Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual c ...

nomination for Best Featured Actor in a Musical and an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role. Following his success on Broadway, Holloway played Pooh-Bah in a 1960 US television Bell Telephone Hour production of ''The Mikado

''The Mikado; or, The Town of Titipu'' is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, their ninth of fourteen operatic collaborations. It opened on 14 March 1885, in London, where it ran at the ...

'', produced by the veteran Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

performer Martyn Green

William Martin Green (22 April 1899 – 8 February 1975), known by his stage name, Martyn Green, was an English actor and singer. He is remembered for his performances and recordings as principal comedian of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, in t ...

. Holloway appeared with Groucho Marx

Julius Henry "Groucho" Marx (; October 2, 1890 – August 19, 1977) was an American comedian, actor, writer, stage, film, radio, singer, television star and vaudeville performer. He is generally considered to have been a master of quick wit an ...

and Helen Traubel of the Metropolitan Opera. His notable films around this time included '' ''Alive and Kicking'''' in 1959, co-starring Sybil Thorndike

Dame Agnes Sybil Thorndike, Lady Casson (24 October 18829 June 1976) was an English actress whose stage career lasted from 1904 to 1969.

Trained in her youth as a concert pianist, Thorndike turned to the stage when a medical problem with her ...

and Kathleen Harrison

Kathleen Harrison (23 February 1892 – 7 December 1995) was a prolific English character actress best remembered for her role as Mrs. Huggett (opposite Jack Warner and Petula Clark) in a trio of British post-war comedies about a worki ...

, and ''No Love for Johnnie

''No Love for Johnnie'' is a 1961 British drama film in CinemaScope directed by Ralph Thomas. It was based on the 1959 book of the same title by the Labour Member of Parliament Wilfred Fienburgh, and stars Peter Finch.

It depicts the disillu ...

'' in 1961 opposite Peter Finch

Frederick George Peter Ingle Finch (28 September 191614 January 1977) was an English-Australian actor of theatre, film and radio.

Born in London, he emigrated to Australia as a teenager and was raised in Sydney, where he worked in vaudeville ...

. In 1962, Holloway took part in a studio recording of ''Oliver!

''Oliver!'' is a Coming-of-age story, coming-of-age Musical theatre, stage musical, with book, music and lyrics by Lionel Bart. The musical is based upon the 1838 novel ''Oliver Twist'' by Charles Dickens.

It premiered at the Wimbledon Theatre ...

'' with Alma Cogan and Violet Carson, in which he played Fagin.

In 1962 Holloway played the role of an English butler called Higgins in a US television sitcom called '' Our Man Higgins''. It ran for only a season. His son Julian also appeared in the series.Obituary, ''The Times'', 1 February 1982, p. 10 In 1964 he again appeared on stage in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

in ''Cool Off!'', a short-lived Faust

Faust is the protagonist of a classic German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust ( 1480–1540).

The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil at a crossroa ...

ian spoof. He returned to the US a few more times after that to take part in ''The Dean Martin Show

''The Dean Martin Show'', not to be confused with the ''Dean Martin Variety Show'' (1959–1960), is a TV variety-comedy series that ran from 1965 to 1974 for 264 episodes. It was broadcast by NBC and hosted by Dean Martin. The theme song to the ...

'' three times and ''The Red Skelton Show

''The Red Skelton Show'' is an American television comedy/variety show that aired from 1951 to 1971. In the decade prior to hosting the show, Richard "Red" Skelton had a successful career as a radio and motion pictures star. Although his televi ...

'' twice. He also appeared in the 1965 war film ''In Harm's Way

''In Harm's Way'' is a 1965 American epic war film produced and directed by Otto Preminger and starring John Wayne, Kirk Douglas and Patricia Neal, with a supporting cast featuring Henry Fonda in a lengthy cameo, Tom Tryon, Paula Prentiss, Stanle ...

'', together with John Wayne

Marion Robert Morrison (May 26, 1907 – June 11, 1979), known professionally as John Wayne and nicknamed The Duke or Duke Wayne, was an American actor who became a popular icon through his starring roles in films made during Hollywood's Go ...

and Kirk Douglas

Kirk Douglas (born Issur Danielovitch; December 9, 1916 – February 5, 2020) was an American actor and filmmaker. After an impoverished childhood, he made his film debut in '' The Strange Love of Martha Ivers'' (1946) with Barbara Stanwyck. D ...

.

Last years

Holloway appeared for the first time in a major British television series in the BBC's 1967 adaptation of P. G. Wodehouse's '' Blandings Castle'' stories, playing Beach, the butler, to

Holloway appeared for the first time in a major British television series in the BBC's 1967 adaptation of P. G. Wodehouse's '' Blandings Castle'' stories, playing Beach, the butler, to Ralph Richardson

Sir Ralph David Richardson (19 December 1902 – 10 October 1983) was an English actor who, with John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier, was one of the trinity of male actors who dominated the British stage for much of the 20th century. He w ...

's Lord Emsworth. His portrayal of Beach was received with critical reservation, but the series was a popular success. After ''My Fair Lady'', Holloway was able to get film roles in ''Mrs. Brown You've Got A Lovely Daughter

"Mrs. Brown, You've Got a Lovely Daughter" is a popular song written by British actor, screenwriter and songwriter Trevor Peacock. It was originally sung by actor Tom Courtenay in ''The Lads'', a British TV play of 1963, and released as a singl ...

'' (1968), which featured the 1960s British pop group Herman's Hermits

Herman's Hermits are an English beat, rock and pop group formed in 1964 in Manchester, originally called Herman and His Hermits and featuring lead singer Peter Noone. Produced by Mickie Most, the Hermits charted with number ones in the UK ...

, '' The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes'', '' Flight of the Doves'' and ''Up the Front

''Up the Front'' is a 1972 British comedy film directed by Bob Kellett and starring Frankie Howerd, Bill Fraser, and Hermione Baddeley. It is the third film spin-off from the television series ''Up Pompeii!'' (the previous films being ''Up th ...

'', all in the early 1970s. His final film was '' Journey into Fear'' (1974)."Holloway, Stanley"British Film Institute, accessed 24 November 2011 In 1970, Holloway began an association with the Shaw Festival in Canada, playing Burgess in '' Candida''. He made what he considered his West End debut as a straight actor in ''Siege'' by

David Ambrose

David Edwin Ambrose (born 21 February 1943) is a British novelist, playwright and screenwriter. His credits include at least twenty films, four stage plays, and many hours of television, including the controversial '' Alternative 3'' (1977). He ...

at the Cambridge Theatre

The Cambridge Theatre is a West End theatre, on a corner site in Earlham Street facing Seven Dials, in the London Borough of Camden, built in 1929–30 for Bertie Meyer on an "irregular triangular site".

Design and construction

It was de ...

in 1972, co-starring with Alastair Sim and Michael Bryant. He returned to Shaw

Shaw may refer to:

Places Australia

*Shaw, Queensland

Canada

* Shaw Street, a street in Toronto

England

*Shaw, Berkshire, a village

* Shaw, Greater Manchester, a location in the parish of Shaw and Crompton

* Shaw, Swindon, a suburb of Swindon

...

and Canada, playing the central character Walter/William in '' You Never Can Tell'' in 1973.

Holloway continued to perform until well into his eighties, touring Asia and Australia in 1977 together with Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and David Langton in '' The Pleasure of His Company'', by Samuel A. Taylor and Cornelia Otis Skinner

Cornelia Otis Skinner (May 30, 1899 – July 9, 1979) was an American writer and actress.

Biography

Skinner was the only child of actor Otis Skinner and actress Maud Durbin. After attending the all-girls' Baldwin School and Bryn Mawr College ( ...

. He made his last appearance performing at the Royal Variety Performance

The ''Royal Variety Performance'' is a televised variety show held annually in the United Kingdom to raise money for the Royal Variety Charity (of which King Charles III is life-patron). It is attended by senior members of the British royal ...

at the London Palladium

The London Palladium () is a Grade II* West End theatre located on Argyll Street, London, in the famous area of Soho. The theatre holds 2,286 seats. Of the roster of stars who have played there, many have televised performances. Between 1955 a ...

in 1980, aged 89.

Holloway died of a stroke

A stroke is a disease, medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemorr ...

at the Nightingale Nursing Home in Littlehampton

Littlehampton is a town, seaside resort, and pleasure harbour, and the most populous civil parish in the Arun District of West Sussex, England. It lies on the English Channel on the eastern bank of the mouth of the River Arun. It is south sout ...

, West Sussex

West Sussex is a county in South East England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the shire districts of Adur, Arun, Chichester, Horsham, and Mid Sussex, and the boroughs of Crawley and Worthing. Covering an ...

, on 30 January 1982, aged 91. He is buried, along with his wife Violet, at St Mary the Virgin Church in East Preston.

Personal life

Holloway was married twice, first to Alice "Queenie" Foran. They met in June 1913 in Clacton, while he was performing in a concert party and she was selling charity flags on behalf of theRoyal National Lifeboat Institution

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) is the largest charity that saves lives at sea around the coasts of the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man, as well as on some inland waterways. It i ...

. Queenie was orphaned at the age of 16, something that Holloway felt they had in common, as his mother had died that year and his father had earlier abandoned the family. He married Queenie in November 1913.

Holloway and Queenie had four children: Joan, born on Holloway's 24th birthday in 1914, Patricia (b. 1920), John (1925–2013) and Mary (b. 1928). Upon the death of her mother, Queenie inherited some property in Southampton Row and relied on the rents from the property for her income.Holloway and Richards, p. 71 During the First World War, while Holloway was away fighting in France, Queenie began to have financial trouble, as the tenants failed to pay their rent. Out of desperation, she approached several loan sharks, incurring a large debt about which Holloway knew nothing. She also started to drink heavily as the pressures from the war and of supporting her daughter took their toll. On Holloway's return from the war, the debt was paid off and they moved to Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the London Borough o ...

, West London. By the late 1920s, Holloway found himself in financial difficulties with the British tax authorities and was briefly declared bankrupt. In the 1930s, Holloway and Queenie moved to Bayswater

Bayswater is an area within the City of Westminster in West London. It is a built-up district with a population density of 17,500 per square kilometre, and is located between Kensington Gardens to the south, Paddington to the north-east, an ...

and remained there until Queenie's death in 1937 at the age of 45, from cirrhosis of the liver. Of the children from this first marriage, John worked as an engineer in an electrics company, and Mary worked for British Petroleum for many years.

On 2 January 1939, Holloway married the 25-year-old actress and former chorus dancer Violet Marion Lane (1913–1997),Holloway and Richards, pp. 170–71 and they moved to Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An ancient parish and latterly a metropolitan borough, it ...

. Violet was born into a working-class family from Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by popul ...

. Although he was a client of the Aza Agency in London, Violet effectively managed Holloway's career, and no project was taken on without her approval. In his autobiography, Holloway said of her, "I suppose I am committing lawful bigamy. Not only is she my wife, lover, mother, cook, chauffeuse, private secretary, house keeper, hostess, electrician, business manager, critic, handy woman, she is also my best friend." Together, they had one son, Julian, whose brief relationship with Patricia Neal's daughter Tessa Dahl

Chantal Sophia "Tessa" Dahl (born 11 April 1957) is an English author and former actress. She is the daughter of British author Roald Dahl and American actress Patricia Neal.

Early life

Dahl was born in Oxford, the second daughter of British au ...

produced a daughter, the model and author Sophie Dahl.

Holloway, Violet and Julian lived mainly in the tiny village of Penn, Buckinghamshire

Penn is a village and civil parish in Buckinghamshire, England, about north-west of Beaconsfield and east of High Wycombe. The parish's cover Penn village and the hamlets of Penn Street, Knotty Green, Forty Green and Winchmore Hill. The p ...

. Holloway also owned other properties including a flat in St John's Wood

St John's Wood is a district in the City of Westminster, London, lying 2.5 miles (4 km) northwest of Charing Cross. Traditionally the northern part of the ancient parish and Metropolitan Borough of Marylebone, it extends east to west from ...

in North West London, which he used when working in the capital, and a flat in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

during the ''My Fair Lady'' Broadway years. The final years of his life were spent in Angmering

Angmering is a village and civil parish between Littlehampton and Worthing in West Sussex on the southern edge of the South Downs National Park, England; about two-thirds of the parish (mostly north of the A27 road) fall within the Park. It is ...

, West Sussex, with Violet. Holloway forged close friendships with fellow performers including Leslie Henson, Gracie Fields, Maurice Chevalier

Maurice Auguste Chevalier (; 12 September 1888 – 1 January 1972) was a French singer, actor and entertainer. He is perhaps best known for his signature songs, including " Livin' In The Sunlight", " Valentine", " Louise", " Mimi", and " Thank H ...

, Laurence Olivier and Arthur Askey, who said of him, "He was the nicest man I ever knew. He never had a wrong word to say about anyone. He was a great actor, a super mimic and a one-man walking comic show." While working in the US, Holloway numbered among his friends Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the " Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular entertainers of the 1940s, 1950s, and ...

, Dean Martin

Dean Martin (born Dino Paul Crocetti; June 7, 1917 – December 25, 1995) was an American singer, actor and comedian. One of the most popular and enduring American entertainers of the mid-20th century, Martin was nicknamed "The King of Cool". M ...

, Burgess Meredith and Groucho Marx.

Honours, memorials and books

Holloway was appointed an Officer of theOrder of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

(OBE) in the 1960 New Year Honours for his services to entertainment. In 1978 he was honoured with a special award by the Variety Club of Great Britain.

There is a memorial plaque dedicated to Holloway in St Paul's, Covent Garden

St Paul's Church is a Church of England parish church located in Bedford Street, Covent Garden, central London. It was designed by Inigo Jones as part of a commission for the 4th Earl of Bedford in 1631 to create "houses and buildings fit fo ...

, London, which is known as "the actors' church". The plaque is next to a memorial to Gracie Fields. In 2009 English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

unveiled a blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term ...

at 25 Albany Road, Manor Park, Essex, the house in which he was born in 1890. There is a building named after him at 2 Coolfin Road, Newham, London, called Stanley Holloway Court.

Holloway entitled his autobiography ''Wiv a Little Bit o' Luck'' after the song he performed in ''My Fair Lady''. The book was ghostwritten by the writer and director Dick Richards and published in 1967. Holloway oversaw the publication of three volumes of the monologues by or associated with him: ''Monologues'' (1979); ''The Stanley Holloway Monologues'' (1980); and ''More Monologues'' (1981).

Recordings

Holloway had a 54-year recording career, beginning in the age ofacoustic recording

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English), or simply a record, is an analog sound storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The groove usually starts near ...

, and ending in the era of the stereophonic LP. He mainly recorded songs from musicals and revues, and he recited many monologues on various subjects. Most prominent among his recordings (aside from his participation in recordings of ''My Fair Lady'') are those of three series of monologues that he made at intervals throughout his career. They featured Sam Small, Albert Ramsbottom, and historical events such as the Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings nrf, Batâle dé Hastings was fought on 14 October 1066 between the Norman-French army of William, the Duke of Normandy, and an English army under the Anglo-Saxon King Harold Godwinson, beginning the Norman Conque ...

, Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

and the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (1 ...

. In all, his discography runs to 130 recordings, spanning the period 1924 to 1978. A review in '' The Gramophone'' of one of his 1957 albums containing recordings of his old "concert party" songs commented, "what a fine voice he has and how well he can use it – diction, phrasing, range and the interpretative insight of the artist".''The Gramophone'', October 1961, p. 72

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * *External links

* * * * *Stanley Holloway pictures on Getty images

Stanley Holloway monologue lyrics

Stanley Holloway on British Pathe News

{{DEFAULTSORT:Holloway, Stanley 1890 births 1982 deaths British Army personnel of World War I British expatriate male actors in the United States British male comedy actors British propagandists Connaught Rangers officers English male comedians English male film actors English male musical theatre actors English male stage actors English male television actors Male actors from London Officers of the Order of the British Empire People from East Ham People from East Preston, West Sussex People from Manor Park, London People of the Easter Rising 20th-century English comedians 20th-century English male actors 20th-century English male singers 20th-century English singers London Rifle Brigade soldiers Military personnel from Essex