St. Lawrence Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

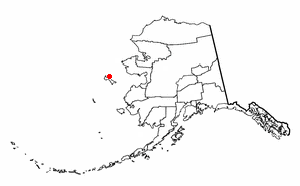

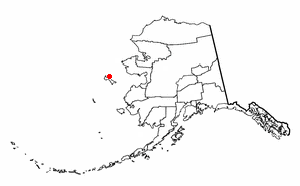

St. Lawrence Island ( ess, Sivuqaq, russian: Остров Святого Лаврентия, Ostrov Svyatogo Lavrentiya) is located west of mainland

The

The

The island is called ''Sivuqaq'' by the Yupik who live there. It was visited by

The island is called ''Sivuqaq'' by the Yupik who live there. It was visited by

On June 22, 1955, during the Cold War, a

On June 22, 1955, during the Cold War, a

Gambell and St. Lawrence Island

Photos from Gambell and St. Lawrence Island, August 2001

{{Authority control Inuit territories Siberian Yupik Seabird colonies

Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

in the Bering Sea, just south of the Bering Strait. The village of Gambell, located on the northwest cape of the island, is from the Chukchi Peninsula

The Chukchi Peninsula (also Chukotka Peninsula or Chukotski Peninsula; russian: Чуко́тский полуо́стров, ''Chukotskiy poluostrov'', short form russian: Чуко́тка, ''Chukotka''), at about 66° N 172° W, is the eastern ...

in the Russian Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: Дальний Восток России, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admin ...

. The island is part of Alaska, but closer to Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

than to the Alaskan mainland. St. Lawrence Island is thought to be one of the last exposed portions of the land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

that once joined Asia with North America during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

period. It is the sixth largest island in the United States and the 113th largest island in the world. It is considered part of the Bering Sea Volcanic Province. The Saint Lawrence Island shrew (''Sorex jacksoni'') is a species of shrew endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

to St. Lawrence Island.

Geography

The

The United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of t ...

defines St. Lawrence Island as Block Group 6, Census Tract 1 of Nome Census Area, Alaska

Nome Census Area is a census area located in the U.S. state of Alaska, mostly overlapping with the Seward Peninsula. As of the 2020 census, the population was 10,046, up from 9,492 in 2010. It is part of the unorganized borough and therefore ...

. As of the 2000 census there were 1,292 people living on a land area of . The island is about long and wide. The island has no trees, and the only woody plants are Arctic willow

''Salix arctica'', the Arctic willow, is a tiny creeping willow (family Salicaceae). It is adapted to survive in Arctic conditions, specifically tundras.

Description

''S. arctica'' is typically a low shrub growing to only in height, rarely to ...

, standing no more than a foot (30 cm) high.

The island's abundance of seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s and marine mammals is due largely to the influence of the Anadyr Current, an ocean current which brings cold, nutrient-rich water from the deep waters of the Bering Sea shelf edge.

To the south of the island there was a persistent polynya

A polynya () is an area of open water surrounded by sea ice. It is now used as a geographical term for an area of unfrozen seawater within otherwise contiguous pack ice or fast ice. It is a loanword from the Russian полынья (), which r ...

in 1999, formed when the prevailing winds from the north and east blow the migrating ice away from the coast.

The climate of Gambell is:

Villages

The island contains two villages: Savoonga and Gambell. The two villages were given title to most of the land on St. Lawrence Island by theAlaska Native Claims Settlement Act

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 18, 1971, constituting at the time the largest land claims settlement in United States history. ANCSA was intended to resolve long-standing ...

in 1971. As a result of having title to the land, the Yupik are legally able to sell the fossilized ivory and other artifacts found on St. Lawrence Island.

The island is now inhabited mostly by Siberian Yupik engaged in hunting, fishing, and reindeer herding. The St. Lawrence Island Yupik people are also known for their skill in carving, mostly with materials from marine mammals (walrus ivory and whale bone). The Arctic yo-yo

An Eskimo yo-yo or Alaska yo-yo ( esu, yuuyuuk; ik, igruuraak) is a traditional two-balled skill toy played and performed by the Eskimo-speaking Alaska Natives, such as Inupiat, Siberian Yupik, and Yup'ik. It resembles fur-covered bolas and yo- ...

may have evolved on the island. Anthropologist Lars Krutak

Lars Krutak (April 14, 1971) is an American anthropologist, photographer, and writer known for his research about tattoo and its cultural background. He produced and hosted the 10-part documentary series ''Tattoo Hunter'' on the Discovery Chan ...

has examined the tattoo traditions of the St. Lawrence Yupik.

History

Prehistory

St. Lawrence Island was first occupied around 2,000 to 2,500 years ago by coastal people characterized by artifacts decorated in the Okvik (oogfik) style. Archaeological sites on the Punuk Islands, off the eastern end of St. Lawrence Island, at Kukulik, near Savoonga and on the hill slopes above Gambell have evidence of the Okvik occupation. The Okvik decorative style is zoomorphic and elaborate, executed in a sometimes crude engraving technique, with greater variation than the Old Bering Sea and Punuk styles. The Okvik occupation is influenced by and may have been coincident with the Old Bering Sea occupation of 2000 years ago to around 700 years ago, characterized by the simpler and more homogeneous Punuk style. Stone artifacts changed from chipped stone to ground slate; carvedivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals i ...

harpoon

A harpoon is a long spear-like instrument and tool used in fishing, whaling, sealing, and other marine hunting to catch and injure large fish or marine mammals such as seals and whales. It accomplishes this task by impaling the target animal ...

heads are smaller and simpler in design.

Prehistoric and early historic occupations of St. Lawrence Island were never permanent, with periods of abandonment and reoccupation depending on resource availability and changes in weather patterns. Famine was common, as evidenced by Harris lines

Growth arrest lines, also known as Harris lines, are lines of increased bone density that represent the position of the growth plate at the time of insult to the organism and formed on long bones due to growth arrest. They are only visible by radi ...

and enamel hypoplasia

Enamel hypoplasia is a defect of the teeth in which the enamel is deficient in quantity, caused by defective enamel matrix formation during enamel development, as a result of inherited and acquired systemic condition(s). It can be identified as m ...

in human skeletons. Travel to and from the mainland was common during calm weather, so the island was used as a hunting base, and occupation sites were re-used periodically rather than permanently occupied.

Major archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsca ...

sites at Gambell and Savoonga (Kukulik) were excavated by Otto Geist and Ivar Skarland of the University of Alaska Fairbanks

The University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF or Alaska) is a public land-grant research university in College, Alaska, a suburb of Fairbanks. It is the flagship campus of the University of Alaska system. UAF was established in 1917 and opened for c ...

. Collections from these excavations are curated at the University of Alaska Museum on the UAF campus.

Arrival of Europeans

The island is called ''Sivuqaq'' by the Yupik who live there. It was visited by

The island is called ''Sivuqaq'' by the Yupik who live there. It was visited by Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

n/Danish explorer Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

on St. Lawrence's Day, August 10, 1728, and named after the day of his visit. The island was the first place in Alaska known to have been visited by European explorers.

There were about 4,000 Central Alaskan Yupik Yupik may refer to:

* Yupik peoples, a group of indigenous peoples of Alaska and the Russian Far East

* Yupik languages, a group of Eskimo-Aleut languages

Yupꞌik (with the apostrophe) may refer to:

* Yup'ik people

The Yup'ik or Yupiaq (sg ...

and Siberian Yupik living in several villages on the island in the mid-19th century. They subsisted by hunting walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the fami ...

and whale

Whales are a widely distributed and diverse group of fully aquatic placental marine mammals. As an informal and colloquial grouping, they correspond to large members of the infraorder Cetacea, i.e. all cetaceans apart from dolphins and ...

and by fishing. The famine in 1878–1880 caused many to starve and many others to leave, decimating the island's population. A revenue cutter

A cutter is a type of watercraft. The term has several meanings. It can apply to the rig (or sailplan) of a sailing vessel (but with regional differences in definition), to a governmental enforcement agency vessel (such as a coast guard or bor ...

visited the island in 1880 and estimated that out of 700 inhabitants, 500 were found dead of starvation. Reports of the day put the blame on traders' supplying the people with liquor causing the people to ″neglect laying up their usual supply of provisions″. Nearly all the residents remaining were Siberian Yupik.

Reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 sub ...

were introduced on the island in 1900 in an attempt to bolster the economy. The reindeer herd grew to about 10,000 animals by 1917, but has since declined. Reindeer are herded as a source of subsistence meat to this day. In 1903 President Theodore Roosevelt established a reindeer reservation on the island. This caused legal issues in the indigenous land claim process to acquire surface and subsurface rights to their land, under the section 19 of Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) as they had to prove that the reindeer reserve was set up to support the indigenous people rather than to protect the reindeer themselves.

World War II

DuringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, islanders served in the Alaska Territorial Guard (ATG). Following disbandment of the ATG in 1947, and with the construction of Northeast Cape Air Force Station in 1952, many islanders joined the Alaska National Guard

The Alaska Department of Military and Veterans Affairs manages military and veterans affairs for the U.S. state of Alaska. It comprises a number of subdepartments, including the Alaska National Guard, Veterans Affairs, the Division of Homeland Sec ...

to provide for the defense of the island and station.

Cold War

On June 22, 1955, during the Cold War, a

On June 22, 1955, during the Cold War, a US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

P2V Neptune

The Lockheed P-2 Neptune (designated P2V by the United States Navy prior to September 1962) is a maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft. It was developed for the US Navy by Lockheed to replace the Lockheed PV-1 Ventura and P ...

with a crew of 11 was attacked by two Soviet Air Forces

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

fighter aircraft along the International Date Line in international waters

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed region ...

over the Bering Straits, between Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

's Kamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: полуостров Камчатка, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and w ...

and Alaska. The P2V crashed on the island's northwest cape, near the village of Gambell. Villagers rescued the crew, 3 of whom were wounded by Soviet fire and 4 of whom were injured in the crash. The Soviet government

The Government of the Soviet Union ( rus, Прави́тельство СССР, p=prɐˈvʲitʲɪlʲstvə ɛs ɛs ɛs ˈɛr, r=Pravítelstvo SSSR, lang=no), formally the All-Union Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, commonly ab ...

, in response to a US diplomatic protest, was unusually conciliatory, stating that:

The Soviet military

The Soviet Armed Forces, the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union and as the Red Army (, Вооружённые Силы Советского Союза), were the armed forces of the Russian SFSR (1917–1922), the Soviet Union (1922–1991), and th ...

was under strict orders to "avoid any action beyond the limits of the Soviet state frontiers."

The Soviet government "expressed regret in regard to the incident," and, "taking into account... conditions which do not exclude the possibility of a mistake from one side or the other," was willing to compensate the US for 50% of damages sustained—the first such offer ever made by the Soviets for any Cold War shoot-down incident.

The US government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a feder ...

stated that it was satisfied with the Soviet expression of regret and the offer of partial compensation, although it said that the Soviet statement also fell short of what the available information indicated.

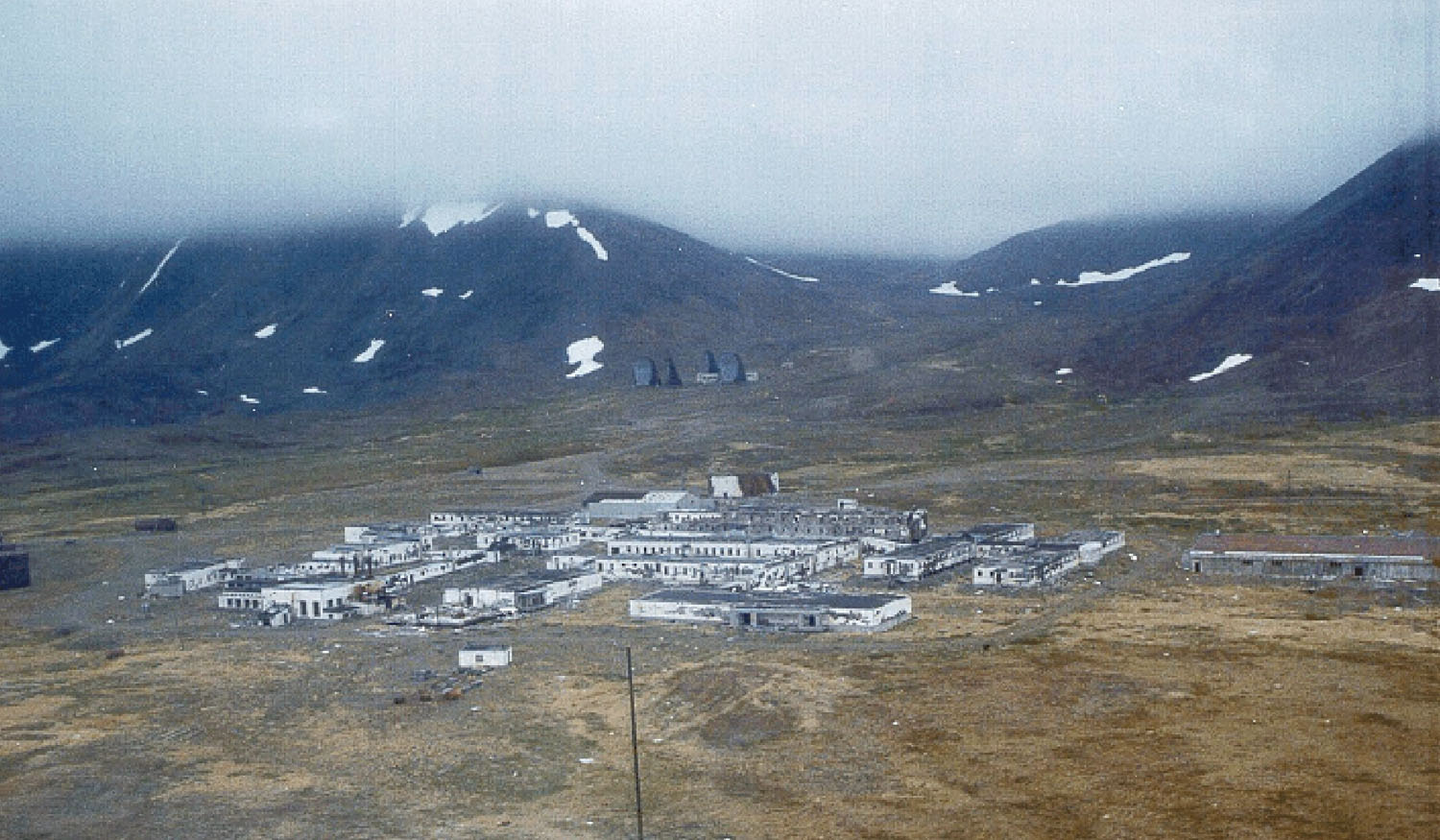

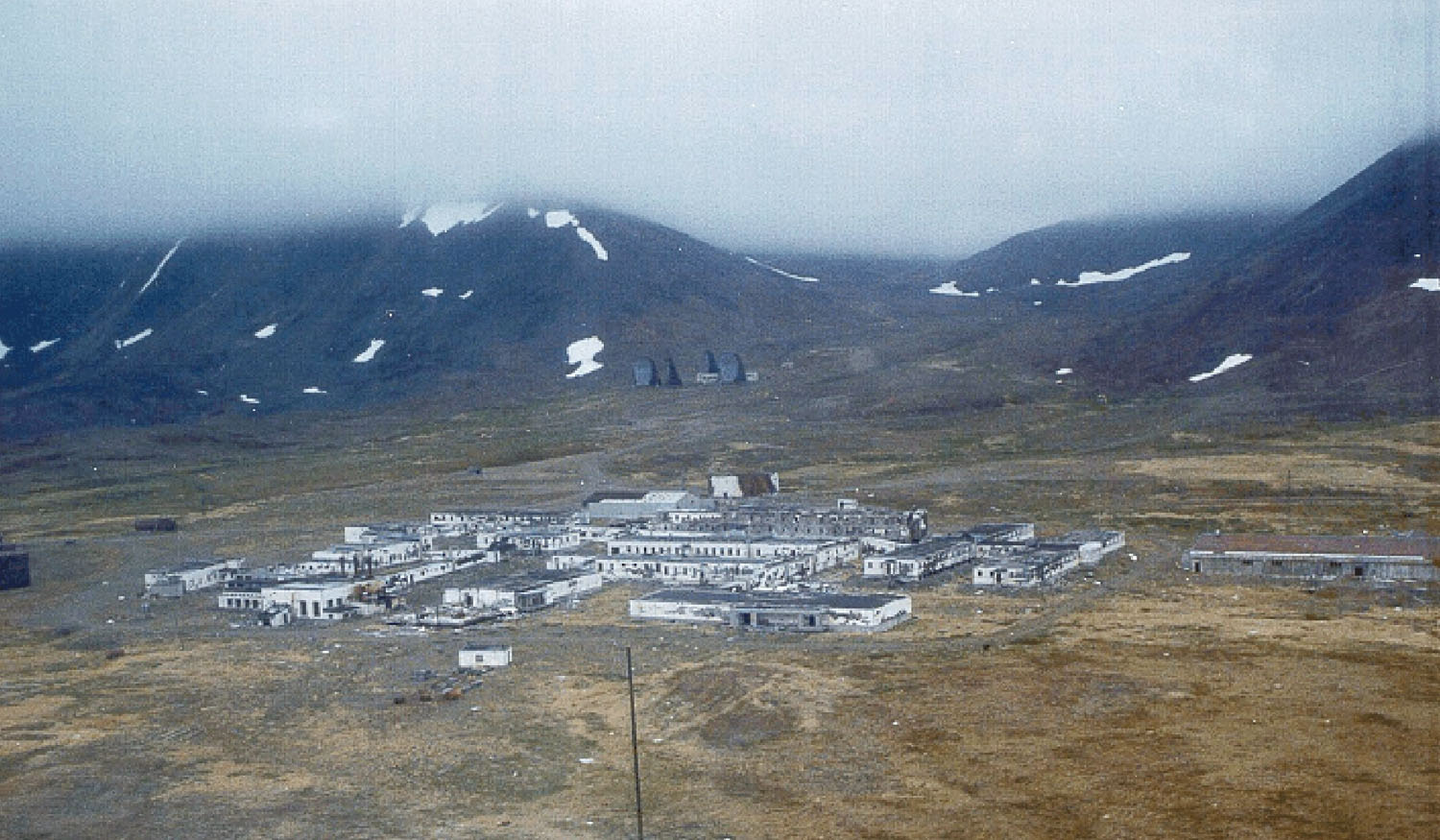

Northeast Cape Air Force Station, at the island's other end, was a United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

facility consisting of an Aircraft Control and Warning (AC&W) radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

site, a United States Air Force Security Service

Initially established as the Air Force (USAF) Security Group in June, 1948, the USAF Security Service (USAFSS) was activated as a major command on Oct 20, 1948 (For redesignations, see Successor units.)

The USAFSS was a secretive branch of the ...

listening post; and a White Alice Communications System

The White Alice Communications System (WACS, "White Alice" colloquially) was a United States Air Force telecommunication network with 80 radio stations constructed in Alaska during the Cold War. It used tropospheric scatter for over-the-horizon li ...

(WACS) site that operated from about 1952 to about 1972. The area surrounding the Northeast Cape base site had been a traditional camp site for several Yupik families for centuries. After the base closed down in the 1970s, many of these people started to experience health problems. Even today, people who grew up at Northeast Cape have high rates of cancer and other diseases, possibly due to PCB

PCB may refer to:

Science and technology

* Polychlorinated biphenyl, an organic chlorine compound, now recognized as an environmental toxin and classified as a persistent organic pollutant

* Printed circuit board, a board used in electronics

* ...

exposure around the site. According to the State of Alaska, those elevated cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

rates have been shown to be comparable to the rates of other Alaskan and non-Alaskan arctic natives who were not exposed to a similar Air Force facility. The majority of the facility was removed in a $10.5 million cleanup program in 2003. Monitoring of the site will continue into the future.

Transportation

The airports areGambell Airport

Gambell Airport is a public airport located in Gambell, a city in the Nome Census Area of the U.S. state of Alaska. The airport is owned by the state.

Facilities

Gambell Airport covers an area of which contains one asphalt and concrete paved r ...

and Savoonga Airport

Savoonga Airport is a state-owned public-use airport located two nautical miles (4 km) south of the central business district of Savoonga, a city in the Nome Census Area of the U.S. state of Alaska. Savoonga is located on St. Lawrence I ...

.

Bibliography

Notes References * - Total pages: 520 *External links

Gambell and St. Lawrence Island

Photos from Gambell and St. Lawrence Island, August 2001

{{Authority control Inuit territories Siberian Yupik Seabird colonies