Spencer Williams (actor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spencer Williams (July 14, 1893 – December 13, 1969) was an American actor and filmmaker. He portrayed Andy on TV's '' The Amos 'n' Andy Show'' and directed films including the 1941

Williams's resulting film, ''

Williams's resulting film, ''

''Spencer Williams: Remembrances of an Early Black Film Pioneer''

1996 video

''Amos 'n' Andy: Anatomy of a Controversy'' Video by Hulu''Go Down, Death!'' Spencer Williams 1944 Film Free Download at Internet Archive''The Blood of Jesus'' Spencer Williams 1941 Film Free Download at Internet Archive

{{DEFAULTSORT:Williams, Spencer 1893 births 1969 deaths Male actors from Louisiana African-American male actors American male television actors People from Vidalia, Louisiana American male film actors United States Army personnel of World War I 20th-century American male actors Film directors from Louisiana African Americans in World War I African-American United States Army personnel

race film

The race film or race movie was a genre of film produced in the United

States between about 1915 and the early 1950s, consisting of films produced for black audiences, and featuring black casts. Approximately five hundred race films were produce ...

''The Blood of Jesus

''The Blood of Jesus'' (also known as ''The Glory Road'') is a 1941 American fantasy drama race film written, directed by and starring Spencer Williams. The plot concerns a Baptist woman who, after being accidentally shot by her atheist husband, ...

''. Williams was a pioneering African-American film producer and director.

Early career

Williams (who was sometimes billed as Spencer Williams Jr.) was born in Vidalia, Louisiana, where the family lived on Magnolia Street. As a youngster, he attended Wards Academy inNatchez, Mississippi

Natchez ( ) is the county seat of and only city in Adams County, Mississippi, United States. Natchez has a total population of 14,520 (as of the 2020 census). Located on the Mississippi River across from Vidalia in Concordia Parish, Louisiana, ...

.

He moved to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

when he was a teenager and secured work as call boy for the theatrical impresario Oscar Hammerstein. During this period, he received mentoring as a comedian from the African American vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

star Bert Williams.

Williams studied at the University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, formally the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, (UMN Twin Cities, the U of M, or Minnesota) is a public land-grant research university in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, United States. ...

and served in the U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

during and after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, rising to the rank of sergeant major

Sergeant major is a senior non-commissioned rank or appointment in many militaries around the world.

History

In 16th century Spain, the ("sergeant major") was a general officer. He commanded an army's infantry, and ranked about third in th ...

. During his military service, Williams traveled the world, serving as General Pershing's bugler while in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

before he was promoted to camp sergeant major. In 1917, Williams was sent to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

to do intelligence work there. After World War I, Williams continued his military career; he was part of a unit whose job was to create war plans for the Southwestern United States, in case they might ever be needed.

He arrived in Hollywood in 1923 and his involvement with films began by assisting with works by Octavus Roy Cohen

Octavus Roy Cohen (1891–1959) was an early 20th century American writer specializing in ethnic comedies. His dialect comedy stories about African Americans gained popularity after being published in the ''Saturday Evening Post'' and were ada ...

. Williams snagged bit roles in motion pictures, including a part in the 1928 Buster Keaton

Joseph Frank "Buster" Keaton (October 4, 1895 – February 1, 1966) was an American actor, comedian, and filmmaker. He is best known for his silent film work, in which his trademark was physical comedy accompanied by a stoic, deadpan expression ...

film ''Steamboat Bill, Jr.

''Steamboat Bill, Jr.'' is a 1928 silent comedy film starring Buster Keaton. Released by United Artists, the film is the final product of Keaton's independent production team and set of gag writers. It was not a box-office success and became th ...

'' He found steady work after arriving in California apart from a short period in 1926 where there were no roles for him; he then went to work as an immigration officer. In 1927, Williams was working for the First National Studio, going on location to Topaz, Arizona to shoot footage for a film called ''The River''.

In 1929, Williams was hired by producer Al Christie

Charles Herbert Christie (April 13, 1882 – October 1, 1955) and Alfred Ernest Christie (November 23, 1886 – April 14, 1951) were Canadian motion picture entrepreneurs.

Early life

Charles Herbert Christie was born between April 13, 1 ...

to create the dialogue for a series of two-reel

A short film is any motion picture that is short enough in running time not to be considered a feature film. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences defines a short film as "an original motion picture that has a running time of 40 minutes ...

comedy films with all-black casts. Williams gained the trust of Christie and was eventually appointed the responsibility to create '' The Melancholy Dame''. This film is considered the first black talkie. The films, which played on racial stereotypes and used grammatically tortured dialogue, included ''The Framing of the Shrew

''The Framing of the Shrew'' is a 1929 American comedy film. It features an African American cast. It was produced by Al Christie and the story was by Octavus Roy Cohen. It was directed by Arvid E. Gillstrom. The plot depicts a husband who gets t ...

'', ''The Lady Fare

''The Lady Fare'' or ''Lady Fare'' is a 1929 American short comedy film directed by William Watson, from a story by Octavus Roy Cohen, and screenplay by Spencer Williams. It was produced by Al Christie and filmed by the Christie Film Company.

...

'', ''Melancholy Dame'', (first Paramount all African-American cast "talkie"), '' Music Hath Charms'', and ''Oft in the Silly Night

''Oft in the Silly Night'' is an American short comedy film released in 1929. It was produced by Al Christie from a story by Octavus Roy Cohen, part of a series published in the ''Saturday Evening Post'' and adapted to film in Christie productions. ...

''. Williams wore many hats at Christie's; he was a sound technician, wrote many of the scripts and was assistant director for many of the films. He was also hired to cast African-Americans for Gloria Swanson

Gloria May Josephine Swanson (March 27, 1899April 4, 1983) was an American actress and producer. She first achieved fame acting in dozens of silent films in the 1920s and was nominated three times for the Academy Award for Best Actress, most f ...

's ''Queen Kelly

''Queen Kelly'' is an American silent film produced in 1928–29 and released by United Artists. The film was directed by Erich von Stroheim, starred Gloria Swanson, in the title role, Walter Byron as her lover, and Seena Owen. The film was p ...

'' (1928) and produced the talkie short film ''Hot Biskits

''Hot Biskits'' was an independent comedy short film released in 1931. It was written and directed by Spencer Williams and was his first film. Glen Gano was the cinematographer. The 10-minute race film was a made by Dixie Comedies Corp. of Hollywoo ...

'', which he wrote and directed, in the same year. Williams also did some work for Columbia

Columbia may refer to:

* Columbia (personification), the historical female national personification of the United States, and a poetic name for America

Places North America Natural features

* Columbia Plateau, a geologic and geographic region i ...

as the supervisor of their '' Africa Speaks'' recordings. Williams was also active in theater productions, taking a role in the all African-American version of ''Lulu Belle'' in 1929.

Due to the pressures of the depression coupled with the lowering demand for black short films, Williams and Christie separated ways. Williams struggled for employment during the years of the Depression and would only occasionally be cast in small roles. Movies included a brief appearance in Warner Bros.’ gangster film '' The Public Enemy'' (1931) in which he was uncredited.Cripps, Thomas. "The Films of Spencer Williams." Black American Literature Forum 12.4 (1978): 128–34. St. Louis University. Web. 5 Nov. 2014. .

By 1931, Williams and a partner had founded their own movie and newsreel company called the Lincoln Talking Pictures Company. The company was self-financed. Williams, who had experience in sound technology, built the equipment, including a sound truck, for his new venture.

Film directing

During the 1930s, Williams secured small roles in race films, a genre of low-budget, independently-produced films with all-black casts that were created solely for exhibition in racially segregated theaters. Williams also created two screenplays for race film production: theWestern film

The Western is a genre set in the American frontier and commonly associated with folk tales of the Western United States, particularly the Southwestern United States, as well as Northern Mexico and Western Canada. It is commonly referred ...

'' Harlem Rides the Range'' and the horror-comedy

Comedy is a genre of fiction that consists of discourses or works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium. The term o ...

''Son of Ingagi

''Son of Ingagi'' is a 1940 American monster movie directed by Richard C. Kahn. It was the first science fiction horror film to feature an all-black cast.Moon 1997, p. 370 It was written by Spencer Williams based on his own short story, ''House ...

'', both released in 1939.

After a three-year hiatus from show business during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, Williams began finding work again. He was cast in Jed Buell’s Black westerns between the years of 1938 and 1940. He played character roles in such black westerns as ''Harlem on the Prairie

''Harlem on the Prairie'' (1937) is a race movie, billed as the first " all-colored" Western musical. The movie reminded audiences that there were black cowboys and corrected a popular Hollywood image of an all-white Old West.

It was produce ...

'' (1937), '' Two-Gun Man from Harlem'' (1938), '' The Bronze Buckaroo'' (1939), and '' Harlem Rides the Range'' (1939). Buell’s idea to hire Williams revolved around his ability to captivate the audience with his showmanship. Williams’ involvement in these films gave him a valuable learning experience in the black film genre. Although these films were considered to be crude films in their creation, Williams got the opportunity to start directing here and there even though his control was scarce.

Alfred N. Sack, whose San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

, later Dallas

Dallas () is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County ...

, Texas based company Sack Amusement Enterprises produced and distributed race films, was impressed with Williams’ screenplay for ''Son of Ingagi'' and offered him the opportunity to write and direct a feature film. At that time, the only African American filmmaker was the self-financing writer/director/producer Oscar Micheaux

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux (; January 2, 1884 – March 25, 1951) was an author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Although the short-lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company owned and controlle ...

. Besides being a film production company, Sack also had interests in movie theaters. He had more than one name for his ventures; they were also known as Sack Attractions and Harlemwood Studios. Sack produced films under all of his company's various names.

With his own film projector, Williams began traveling in the southern US, showing his films to audiences there. During this time, he met William H. Kier, who was also traveling the same circuit showing films. The two formed a partnership and produced some motion pictures, training films for the Army Air Forces, as well as a film for the Catholic diocese of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

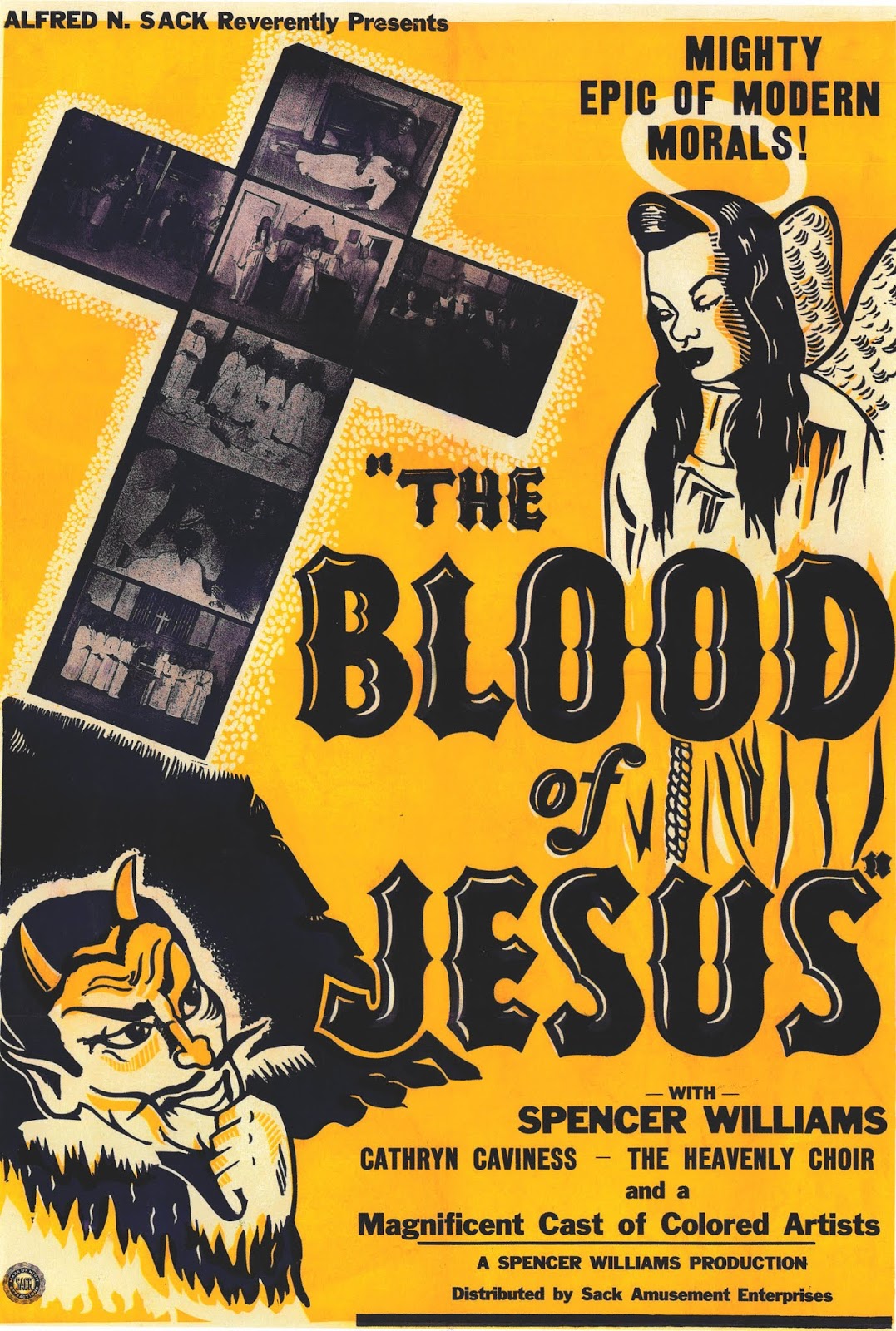

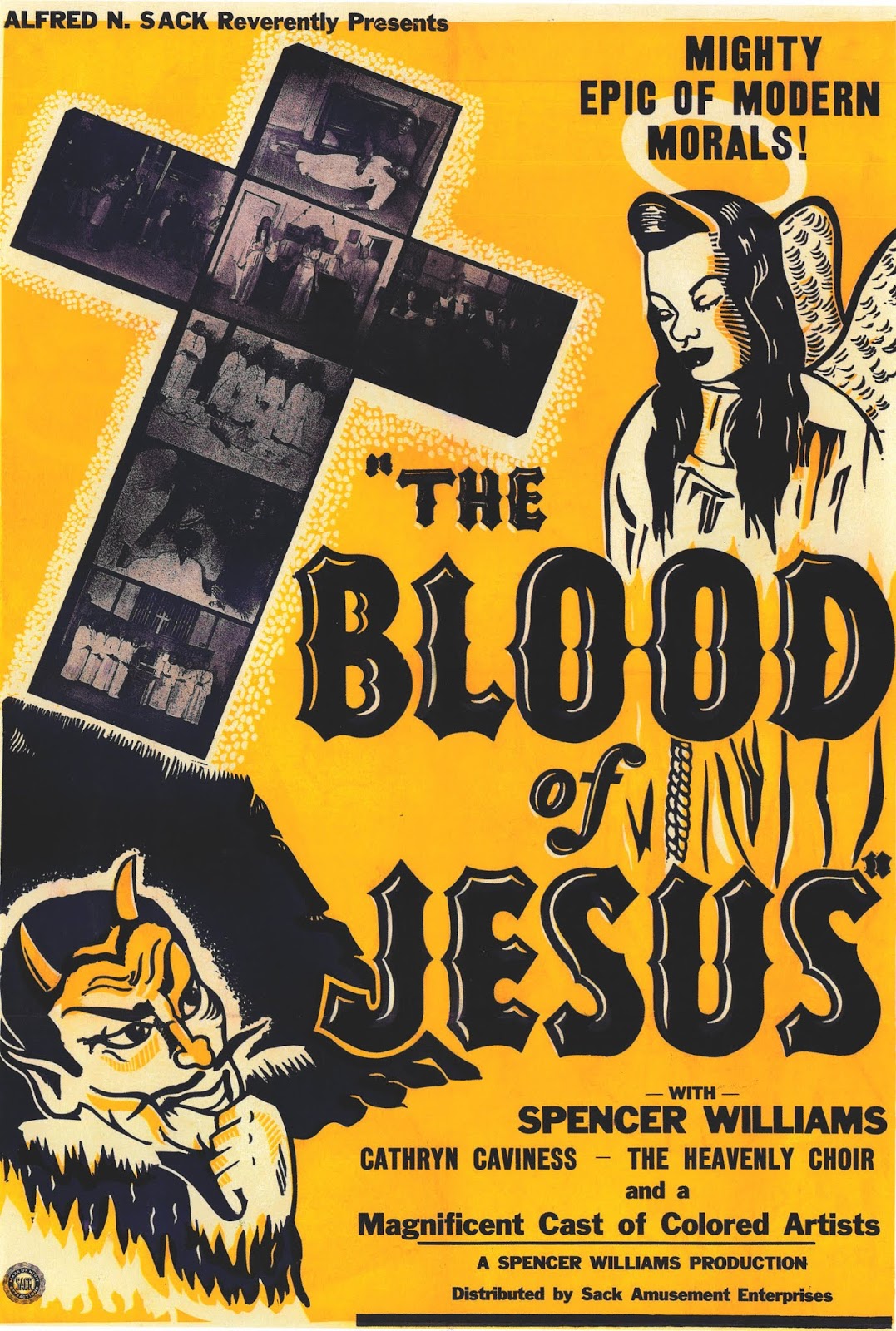

''The Blood of Jesus''

Williams's resulting film, ''

Williams's resulting film, ''The Blood of Jesus

''The Blood of Jesus'' (also known as ''The Glory Road'') is a 1941 American fantasy drama race film written, directed by and starring Spencer Williams. The plot concerns a Baptist woman who, after being accidentally shot by her atheist husband, ...

'' (1941), was produced by his own company, Amegro, on a $5,000 budget using non-professional actors for his cast. It was the first film he directed and Williams also wrote the screenplay. A religious fantasy about the struggle for a dying’ Christian woman’s soul, the film was a major commercial success. Sack declared ''The Blood of Jesus'' was "possibly the most successful" race film ever made, and Williams was invited to direct additional films for Sack Amusement Enterprises.

There were problems that the producers faced with the technical aspects of the film. Despite these issues, Williams used his expertise to help with the camera, special effects and symbolism. The themes that he used in the film helped the film receive praise. Religious themes, including Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and Southern Baptist

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) is a Christian denomination based in the United States. It is the world's largest Baptists, Baptist denomination, and the Protestantism in the United States, largest Protestantism, Protestant and Christia ...

, helped underpin the narrative.

Despite the success that ''The Blood of Jesus

''The Blood of Jesus'' (also known as ''The Glory Road'') is a 1941 American fantasy drama race film written, directed by and starring Spencer Williams. The plot concerns a Baptist woman who, after being accidentally shot by her atheist husband, ...

'' enjoyed, Williams's next film was considered an epic failure and seen by few. The attempt to create a wartime drama resulted in the film '' Marching On!'' (1943). Set with World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

as the backdrop, the film was badly made and was left in the shadow of the Army financed film ''The Negro Soldier

''The Negro Soldier'' is a 1944 documentary film created by the United States Army during World War II. It was produced by Frank Capra as a follow up to his successful film series ''Why We Fight''. The army used the film as propaganda to convi ...

'' (1944). Most of the narrative seen in ''Marching On'' was influenced by William’s own time in the army during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. Due to an uneven and uninteresting plot the film was seen as a dud and was unable to garner the social acknowledgment that Williams had hoped it would receive.

Williams's next film, '' Go Down Death'' (1944), is considered to be on par with ''The Blood of Jesus

''The Blood of Jesus'' (also known as ''The Glory Road'') is a 1941 American fantasy drama race film written, directed by and starring Spencer Williams. The plot concerns a Baptist woman who, after being accidentally shot by her atheist husband, ...

'' as the best overall primitive film that Williams made. Just like that movie, Williams directed, wrote the screenplay, and acted in the film. He gained inspiration for the story of the screenplay from the fable of the same name, written by the poet James Weldon Johnson

James Weldon Johnson (June 17, 1871June 26, 1938) was an American writer and civil rights activist. He was married to civil rights activist Grace Nail Johnson. Johnson was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peop ...

.

The years after his most successful films and the years preceding his mainstream success with ''Amos 'n' Andy

''Amos 'n' Andy'' is an American radio sitcom about black characters, initially set in Chicago and later in the Harlem section of New York City. While the show had a brief life on 1950s television with black actors, the 1928 to 1960 radio sho ...

'' found Williams in another career rut. Rather than continuing to make film in his primitive format, he began to try to follow mainstream Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywoo ...

conventions. Williams's attempts to conform in the film industry actually began to bog down his stories and his otherwise original films.

In the next six years, Williams directed '' Brother Martin: Servant of Jesus'' (1942), '' Marching On!'' (1943), '' Go Down Death'' (1944), '' Of One Blood'' (1944), '' Dirty Gertie from Harlem U.S.A.'' (1946), '' The Girl in Room 20'' (1946), '' Beale Street Mama'' (1947) and ''Juke Joint

Juke joint (also jukejoint, jook house, jook, or juke) is the vernacular term for an informal establishment featuring music, dancing, gambling, and drinking, primarily operated by African Americans in the southeastern United States. A juke joint ...

'' (1947). After working ten years in Dallas, Williams returned to Hollywood in 1950.

Following the production of ''Juke Joint'', Williams relocated to Tulsa, Oklahoma

Tulsa () is the second-largest city in the state of Oklahoma and 47th-most populous city in the United States. The population was 413,066 as of the 2020 census. It is the principal municipality of the Tulsa Metropolitan Area, a region wit ...

, where he joined Amos T. Hall in founding the American Business and Industrial College.

''Amos 'n' Andy''

Prior to his involvement with ''Amos 'n' Andy

''Amos 'n' Andy'' is an American radio sitcom about black characters, initially set in Chicago and later in the Harlem section of New York City. While the show had a brief life on 1950s television with black actors, the 1928 to 1960 radio sho ...

'', Williams was immensely popular among the African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

audiences. U.S. radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a tr ...

comedians Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, who cast Williams as Andy, were able to claim that they were the ones who found Williams and gave him the chance to be seen in the limelight because he was virtually unknown amongst the white audience.

In 1948, Gosden and Correll were planning to take their long-running comedy program ''Amos 'n Andy

''Amos 'n' Andy'' is an American radio sitcom about black characters, initially set in Chicago and later in the Harlem section of New York City. While the show had a brief life on 1950s television with black actors, the 1928 to 1960 radio sho ...

'' to television. The program focused on the misadventures of a group of African Americans in the Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater Ha ...

section of New York City. Gosden and Correll were white, but played the black lead characters using racially stereotypical speech patterns. They had previously played the roles in blackface

Blackface is a form of theatrical makeup used predominantly by non-Black people to portray a caricature of a Black person.

In the United States, the practice became common during the 19th century and contributed to the spread of racial stereo ...

make-up for the 1930 film '' Check and Double Check'', but the television version used an African American cast.Andrews, Bart and Ahrgus Juilliard. "Holy Mackerel!: The Amos ‘n' Andy Show." New York: E.P Dutton, 1986.

Gosden and Correll conducted an extensive national talent search to cast the television version of ''Amos 'n Andy''. News of the search reached Tulsa, where Williams was sought out by a local radio station that was aware of his previous work in race films. A Catholic priest, who was a radio listener and a friend, was the key to the whereabouts of Williams. He was working in Tulsa as the head of a vocational school for veterans when the casting call went out. Williams successfully auditioned for Gosden and Correll, and he was cast as Andrew H. Brown. Williams was joined in the cast by New York theater actor Alvin Childress

Alvin Childress (September 15, 1907 – April 19, 1986) was an American actor, who is best known for playing the cabdriver Amos Jones in the 1950s television comedy series ''Amos 'n' Andy''.

Biography

Alvin Childress was born in Meridian, Missis ...

, who was cast as Amos, and vaudeville comedian Tim Moore, who was cast as their friend George "Kingfish" Stevens. When Williams accepted the role of Andy, he returned to a familiar location; the CBS studios were built on the former site of the Christie Studios

Christie Film Company was an American pioneer motion picture company founded in Hollywood, California by Al Christie and Charles Christie, two brothers from London, Ontario, Canada. It made comedies.

While Charles served almost exclusively in a ...

. Until ''Amos 'n' Andy'', Williams had never worked in television.

''Amos 'n Andy'' was the first U.S. television program with an all-black cast, running for 78 episodes on CBS from 1951 to 1953. However, the program created considerable controversy, with the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&n ...

going to federal court to achieve an injunction to halt its premiere. In August 1953, after the program had recently left the air, there were plans to turn it into a vaudeville act with Williams, Moore and Childress reprising their television roles. It is not known if there were any performances. After the show completed its network run, CBS syndicated ''Amos 'n Andy'' to local U.S. television stations and sold the program to television networks in other countries. The program was eventually pulled from release in 1966, under pressure from civil rights groups that stated it offered a negatively distorted view of African American life. The show would not be seen on nationwide television again until 2012.

While the show was still in production, Williams and Freeman Gosden clashed over the portrayal of Andy, with Gosden telling Williams he knew how ''Amos 'n' Andy'' were meant to talk. Gosden never visited the set again.

Williams, along with television show cast members Tim Moore, Alvin Childress, and Lillian Randolph

Lillian Randolph (December 14, 1898 – September 12, 1980) was an American actress and singer, a veteran of radio, film, and television. She worked in entertainment from the 1930s until shortly before her death. She appeared in hundreds of rad ...

and her choir, began a US tour as "The TV Stars of ''Amos 'n' Andy''" in 1956. CBS considered this a violation of their exclusivity rights for the show and its characters; the tour came to a premature end. Williams, Moore, Childress and Johnny Lee, performed a one-night show in Windsor, Ontario

Windsor is a city in southwestern Ontario, Canada, on the south bank of the Detroit River directly across from Detroit, Michigan, United States. Geographically located within but administratively independent of Essex County, it is the southe ...

in 1957, apparently without any legal action being taken.

Williams returned to work in stage productions. In 1958, he had a role in the Los Angeles production of ''Simply Heavenly''; the play had a successful New York run. His last credited role was as a hospital orderly in the 1962 Italian horror production ''L'Orribile Segreto del Dottor Hitchcock

''The Horrible Dr. Hichcock'' (Italian title: ''L'Orribile Segreto del Dr. Hichcock'', literally ''The Horrible Secret of Dr. Hichcock'') is a 1962 Italian horror film, directed by Riccardo Freda and written by Ernesto Gastaldi. The film stars B ...

''.

After his failed attempts to find success in the film industry once again, Williams decided to fully retire and began to live off of his pension that he was receiving from his time with the US Military

The United States Armed Forces are the Military, military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six Military branch, service branches: the United States Army, Army, United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps, United States N ...

.

Death and legacy

Williams died of a kidney ailment on December 13, 1969, at the Sawtelle Veterans Administration Hospital inLos Angeles, California

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, largest city in the U.S. state, state of California and the List of United States cities by population, sec ...

. He was survived by his wife, Eula. At the time of his death, news coverage focused solely on his work as a television actor, since few white filmgoers knew of his race films. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' obituary for Williams cited ''Amos 'n Andy'' but made no mention of his work as a film director. A World War I veteran, he is buried at Los Angeles National Cemetery

The Los Angeles National Cemetery is a United States National Cemetery in the Sawtelle unincorporated community of the West Los Angeles neighborhood in Los Angeles County, California.

Geography

The entrance to the cemetery is located at 950 Sou ...

.

When friends and family from Vidalia, Louisiana were interviewed for a local newspaper article in 2001, he was remembered as a happy person, who was always singing or whistling and telling jokes. His younger cousins also recalled his generosity with them for "candy money"; just as he was seen on television as Andy, he always had his cigar. On March 31, 2010, the state of Louisiana voted to honor Williams and musician Will Haney, also from Vidalia, in a celebration on May 22 of that year.

Career re-evaluation

Despite his contribution as a pioneer in black American film of the 1930s and the 1940s, Williams was almost completely forgotten after his death. While even to this day his legacy doesn’t enjoy the same recognition and praise that other black film pioneers such asOscar Micheaux

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux (; January 2, 1884 – March 25, 1951) was an author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Although the short-lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company owned and controlle ...

, in his time, Williams was considered one of the few successful black Americans involved in the film industry during this period.

Recognition for Williams’ work as a film director came years after his death, when film historians began to rediscover the race films. Some of Williams’ films were considered lost until they were located in a Tyler, Texas

Tyler is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the largest city and county seat of Smith County. It is also the largest city in Northeast Texas. With a 2020 census population of 105,995, Tyler was the 33rd most populous city in Texas and 2 ...

, warehouse in 1983. One film directed by Williams, his 1942 feature ''Brother Martin: Servant of Jesus'', is still considered lost. There were seven films in total; they were originally shown at small gatherings throughout the South.

Most film historians consider ''The Blood of Jesus'' to be Williams’ crowning achievement as a filmmaker. Dave Kehr

David Kehr (born 1953) is an American museum curator and film critic. For many years a critic at the '' Chicago Reader'' and the ''Chicago Tribune,'' he later wrote a weekly column for ''The New York Times'' on DVD releases. He later became a ...

of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' called the film "magnificent" and ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'' magazine counted it among its "25 Most Important Films on Race." In 1991, ''The Blood of Jesus'' became the first race film to be added to the U.S. National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception ...

.

Film critic Armond White

Armond White (born ) is an American film and music critic who writes for ''National Review'' and '' Out''. He was previously the editor of '' CityArts'' (2011–2014), the lead film critic for the alternative weekly ''New York Press'' (1997–20 ...

named both ''The Blood of Jesus'' and ''Go Down Death'' as being "among the most spiritually adventurous movies ever made. They conveyed the moral crisis of the urban/country, blues/spiritual musical dichotomies through their documentary style and fable-like narratives."

However, Williams’ films have also been the subject of criticism. Richard Corliss, writing in ''Time'' magazine, stated: "Aesthetically, much of Williams' work vacillates between inert and abysmal. The rural comedy of ''Juke Joint'' is logy, as if the heat had gotten to the movie; even the musical scenes, featuring North Texas jazzman Red Calhoun, move at the turtle tempo of Hollywood's favorite black of the period, Stepin Fetchit

Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry (May 30, 1902 – November 19, 1985), better known by the stage name Stepin Fetchit, was an American vaudevillian, comedian, and film actor of Jamaican and Bahamian descent, considered to be the first black a ...

. And there were technical gaffes galore: in a late-night scene in ''Dirty Gertie,'' actress Francine Everett

Francine Everett (born Franciene Williamson; April 13, 1915 – May 27, 1999) was an American actress and singer.

Everett is best known for her performances in race films, independently produced motion pictures with all-black casts that we ...

clicks on a bedside lamp and the screen actually darkens for a moment before full lights finally come up. Yet at least one Williams film, his debut ''Blood of Jesus'' (1941), has a naive grandeur to match its subject." It should also be realized that Williams often worked on a very meager budget. ''The Blood of Jesus'' was filmed for a cost of $5,000; most black films of that era had budgets of double and triple that amount.

Williams began writing a book about his 55 years in show business in 1959.

Filmography

Williams is credited as both an actor and a director.Actor

Director

References

External links

* * * *''Spencer Williams: Remembrances of an Early Black Film Pioneer''

1996 video

Watch

''Amos 'n' Andy: Anatomy of a Controversy'' Video by Hulu

{{DEFAULTSORT:Williams, Spencer 1893 births 1969 deaths Male actors from Louisiana African-American male actors American male television actors People from Vidalia, Louisiana American male film actors United States Army personnel of World War I 20th-century American male actors Film directors from Louisiana African Americans in World War I African-American United States Army personnel