Spencer Perceval on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spencer Perceval (1 November 1762 – 11 May 1812) was a British statesman and barrister who served as

Perceval was born in

Perceval was born in

As the second son of a second marriage, and with an allowance of only £200 a year (), Perceval faced the prospect of having to make his own way in life. (Under primogeniture, the first son inherited land and title.) He chose the law as a profession, studied at Lincoln's Inn, and was called to the bar in 1786. Perceval's mother had died in 1783. Perceval and his brother Charles, now Lord Arden, rented a house in Charlton, where they fell in love with two sisters who were living in the Percevals' old childhood home. The sisters' father, Sir Thomas Spencer Wilson, approved of the match between his eldest daughter Margaretta and Lord Arden, who was wealthy and already a Member of Parliament and a Lord of the Admiralty. Perceval, who was at that time an impecunious barrister on the Midland Circuit, was told to wait until the younger daughter, Jane, came of age in three years' time. When Jane reached 21, in 1790, Perceval's career was still not prospering, and Sir Thomas still opposed the marriage.

The couple eloped and married by special licence in East Grinstead. They set up home together in lodgings over a carpet shop in Bedford Row, later moving to

As the second son of a second marriage, and with an allowance of only £200 a year (), Perceval faced the prospect of having to make his own way in life. (Under primogeniture, the first son inherited land and title.) He chose the law as a profession, studied at Lincoln's Inn, and was called to the bar in 1786. Perceval's mother had died in 1783. Perceval and his brother Charles, now Lord Arden, rented a house in Charlton, where they fell in love with two sisters who were living in the Percevals' old childhood home. The sisters' father, Sir Thomas Spencer Wilson, approved of the match between his eldest daughter Margaretta and Lord Arden, who was wealthy and already a Member of Parliament and a Lord of the Admiralty. Perceval, who was at that time an impecunious barrister on the Midland Circuit, was told to wait until the younger daughter, Jane, came of age in three years' time. When Jane reached 21, in 1790, Perceval's career was still not prospering, and Sir Thomas still opposed the marriage.

The couple eloped and married by special licence in East Grinstead. They set up home together in lodgings over a carpet shop in Bedford Row, later moving to

On the resignation of Grenville, the Duke of Portland put together a ministry of Pittites and asked Perceval to become Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons. Perceval would have preferred to remain attorney general or become

On the resignation of Grenville, the Duke of Portland put together a ministry of Pittites and asked Perceval to become Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons. Perceval would have preferred to remain attorney general or become

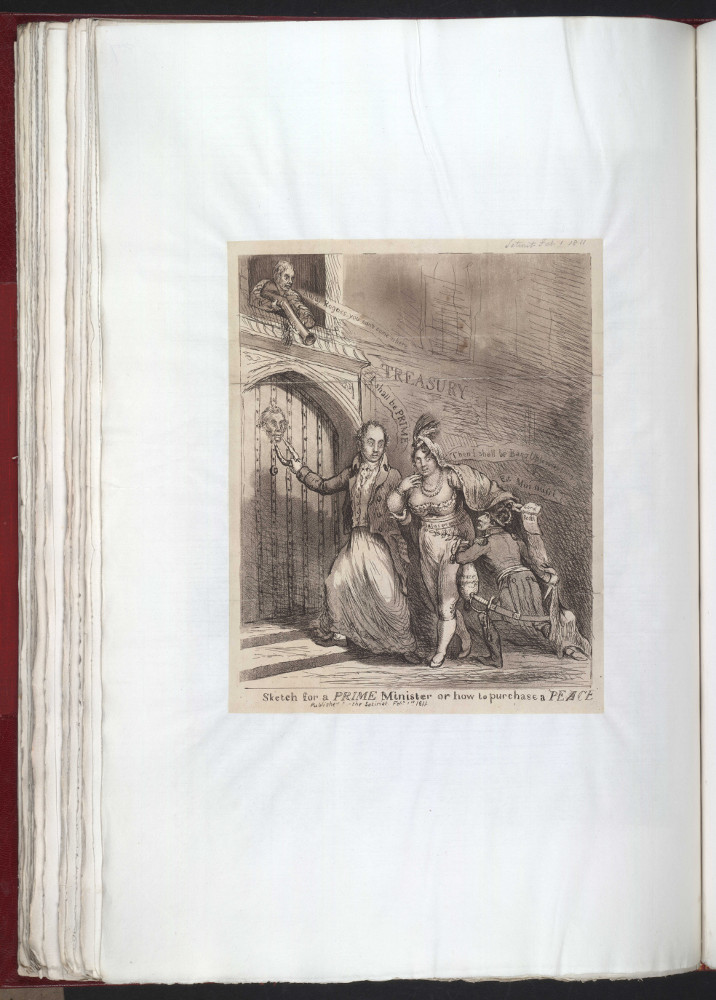

King George III had celebrated his Golden Jubilee in 1809; by the following autumn he was showing signs of a return of the illness that had led to the threat of a Regency in 1788. The prospect of a Regency was not attractive to Perceval, as the Prince of Wales was known to favour Whigs and disliked Perceval for the part he had played in the "delicate investigation". Twice Parliament was adjourned in November 1810, as doctors gave optimistic reports about the King's chances of a return to health. In December select committees of the Lords and Commons heard evidence from the doctors, and Perceval finally wrote to the Prince of Wales on 19 December saying that he planned the next day to introduce a regency bill. As with Pitt's bill in 1788, there would be restrictions: the regent's powers to create peers and award offices and pensions would be restricted for 12 months,

King George III had celebrated his Golden Jubilee in 1809; by the following autumn he was showing signs of a return of the illness that had led to the threat of a Regency in 1788. The prospect of a Regency was not attractive to Perceval, as the Prince of Wales was known to favour Whigs and disliked Perceval for the part he had played in the "delicate investigation". Twice Parliament was adjourned in November 1810, as doctors gave optimistic reports about the King's chances of a return to health. In December select committees of the Lords and Commons heard evidence from the doctors, and Perceval finally wrote to the Prince of Wales on 19 December saying that he planned the next day to introduce a regency bill. As with Pitt's bill in 1788, there would be restrictions: the regent's powers to create peers and award offices and pensions would be restricted for 12 months,

At 5:15 pm, on the evening of 11 May 1812, Perceval was on his way to attend the inquiry into the Orders in Council. As he entered the lobby of the House of Commons, a man stepped forward, drew a pistol and shot him in the chest. Perceval fell to the floor, after uttering something that was variously heard as "murder" and "oh my God". They were his last words. By the time he had been carried into an adjoining room and propped up on a table with his feet on two chairs, he was senseless, although there was still a faint pulse. When a surgeon arrived a few minutes later, the pulse had stopped, and Perceval was declared dead.

At first it was feared that the shot might signal the start of an uprising, but it soon became apparent that the assassin – who had made no attempt to escape – was a man with an obsessive grievance against the Government and had acted alone. The assassin,

At 5:15 pm, on the evening of 11 May 1812, Perceval was on his way to attend the inquiry into the Orders in Council. As he entered the lobby of the House of Commons, a man stepped forward, drew a pistol and shot him in the chest. Perceval fell to the floor, after uttering something that was variously heard as "murder" and "oh my God". They were his last words. By the time he had been carried into an adjoining room and propped up on a table with his feet on two chairs, he was senseless, although there was still a faint pulse. When a surgeon arrived a few minutes later, the pulse had stopped, and Perceval was declared dead.

At first it was feared that the shot might signal the start of an uprising, but it soon became apparent that the assassin – who had made no attempt to escape – was a man with an obsessive grievance against the Government and had acted alone. The assassin,

Perceval was mourned by many; Lord Chief Justice Sir James Mansfield wept during his summing up to the jury at Bellingham's trial. However, in some quarters he was unpopular and in

Perceval was mourned by many; Lord Chief Justice Sir James Mansfield wept during his summing up to the jury at Bellingham's trial. However, in some quarters he was unpopular and in  Perceval's assassination inspired poems such as ''Universal sympathy on the martyr'd statesman'' (1812):

One of Perceval's most noted critics, especially on the question of Catholic emancipation, was the cleric

Perceval's assassination inspired poems such as ''Universal sympathy on the martyr'd statesman'' (1812):

One of Perceval's most noted critics, especially on the question of Catholic emancipation, was the cleric

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern ...

from October 1809 until his assassination in May 1812. Perceval is the only British prime minister to have been assassinated, and the only solicitor-general or attorney-general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

to have become prime minister.

The younger son of an Anglo-Irish earl, Perceval was educated at Harrow School and Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any college at either Cambridge or Oxford. ...

. He studied law at Lincoln's Inn, practised as a barrister on the Midland circuit, and in 1796 became a King's Counsel. He entered politics at age 33 as a member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for Northampton. A follower of William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

, Perceval always described himself as a "friend of Mr. Pitt", rather than a Tory. Perceval was opposed to Catholic emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

and reform of Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

; he supported the war against Napoleon and the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. He was opposed to hunting, gambling and adultery; he did not drink as much as most MPs at the time, gave generously to charity, and enjoyed spending time with his thirteen children.

After a late entry into politics, his rise to power was rapid: he was appointed as Solicitor General and then Attorney General for England and Wales

His Majesty's Attorney General for England and Wales is one of the law officers of the Crown and the principal legal adviser to sovereign and Government in affairs pertaining to England and Wales. The attorney general maintains the Attorney G ...

in the Addington ministry

Henry Addington, a member of the Tories, was appointed by King George III to lead the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 1801 to 1804 and served as an interlude between Pitt. Ministries. Addington's ministry is m ...

, Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of t ...

in the second Portland ministry

This is a list of members of the Tory government of the United Kingdom in office under the leadership of the Duke of Portland

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, d ...

, and then became prime minister in 1809. At the head of a weak government, Perceval faced a number of crises during his term in office, including an inquiry into the Walcheren expedition

The Walcheren Campaign ( ) was an unsuccessful British expedition to the Netherlands in 1809 intended to open another front in the Austrian Empire's struggle with France during the War of the Fifth Coalition. Sir John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chath ...

, the madness of King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, economic depression, and Luddite

The Luddites were a secret oath-based organisation of English textile workers in the 19th century who formed a radical faction which destroyed textile machinery. The group is believed to have taken its name from Ned Ludd, a legendary weaver ...

riots. He overcame those crises, successfully pursued the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

in the face of opposition defeatism, and won the support of the Prince Regent

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

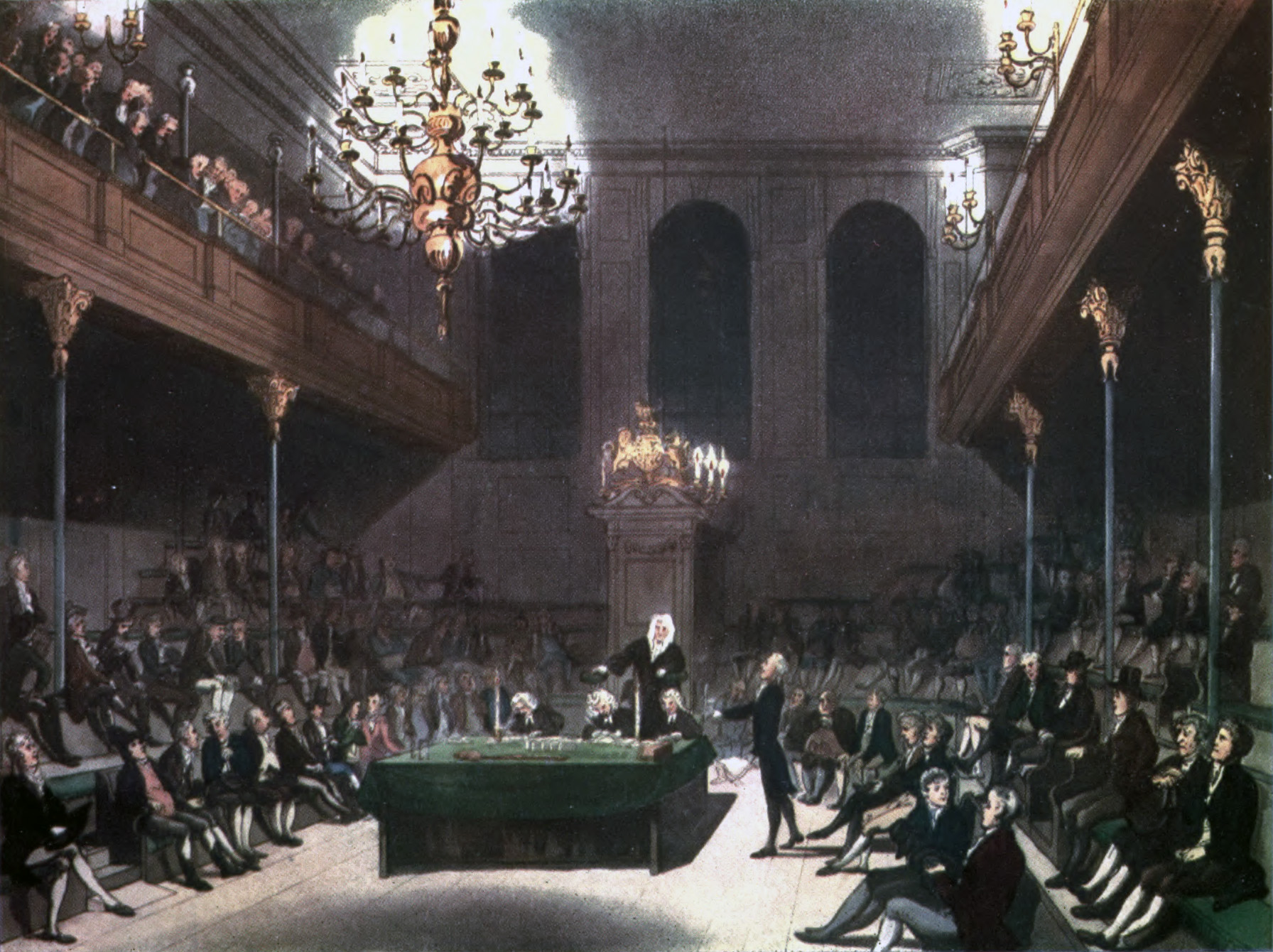

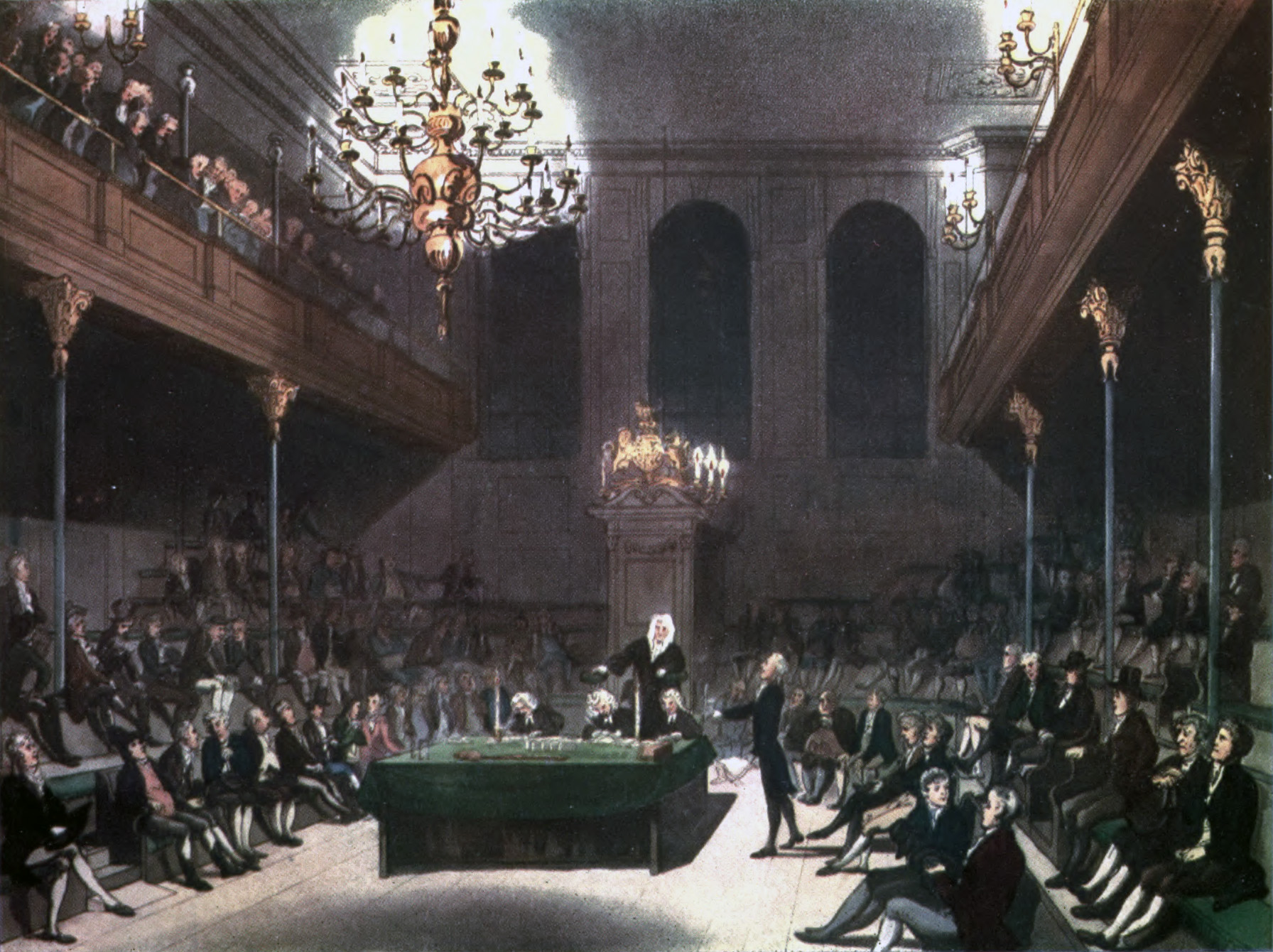

. His position was looking stronger by early 1812, when, in the lobby of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

, he was assassinated by a merchant with a grievance against his government.

Perceval had four older brothers who survived to adulthood. Through expiry of their male-line, male heirs, the earldom of Egmont passed to one of his great-grandsons in the early twentieth century and became extinct in 2011.

Childhood and education

Audley Square Audley may refer to:

People

*Audley (surname)

*Audley Harrison, British boxer

Places

*Audley End House, a country house just outside Saffron Walden, Essex, England

*Audley House, London, a block of flats in central London, England

*Audley, Ontario ...

, Mayfair, London the seventh son of John Perceval, 2nd Earl of Egmont

John Perceval, 2nd Earl of Egmont, PC, FRS (25 February 17114 December 1770) was a British politician, political pamphleteer, and genealogist who served as First Lord of the Admiralty.

Early life

He was the son and heir of John Perceval, 1st ...

; he was the second son of the Earl's second marriage. His mother, Catherine Compton, Baroness Arden, was a granddaughter of the 4th Earl of Northampton. Spencer was a Compton family name; Catherine Compton's great uncle Spencer Compton, 1st Earl of Wilmington

Spencer Compton, 1st Earl of Wilmington, (2 July 1743) was a British Whig statesman who served continuously in government from 1715 until his death. He sat in the English and British House of Commons between 1698 and 1728, and was then raised ...

, had been prime minister.

His father, a political advisor to Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales, (Frederick Louis, ; 31 January 170731 March 1751), was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George II of Great Britain. He grew estranged from his parents, King George and Queen Caroline. Frederick was the fa ...

and King George III, served briefly in the Cabinet as First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

. Perceval's early childhood was spent at Charlton House, which his father had taken to be near Woolwich Dockyard

Woolwich Dockyard (formally H.M. Dockyard, Woolwich, also known as The King's Yard, Woolwich) was an English naval dockyard along the river Thames at Woolwich in north-west Kent, where many ships were built from the early 16th century until th ...

.

Perceval's father died when he was eight. Perceval went to Harrow School, where he was a disciplined and hard-working pupil. It was at Harrow that he developed an interest in evangelical Anglicanism and formed what was to be a lifelong friendship with Dudley Ryder. After five years at Harrow, he followed his older brother Charles to Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a College town, university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cam ...

. There he won the declamation prize in English and graduated in 1782.

Legal career and marriage

As the second son of a second marriage, and with an allowance of only £200 a year (), Perceval faced the prospect of having to make his own way in life. (Under primogeniture, the first son inherited land and title.) He chose the law as a profession, studied at Lincoln's Inn, and was called to the bar in 1786. Perceval's mother had died in 1783. Perceval and his brother Charles, now Lord Arden, rented a house in Charlton, where they fell in love with two sisters who were living in the Percevals' old childhood home. The sisters' father, Sir Thomas Spencer Wilson, approved of the match between his eldest daughter Margaretta and Lord Arden, who was wealthy and already a Member of Parliament and a Lord of the Admiralty. Perceval, who was at that time an impecunious barrister on the Midland Circuit, was told to wait until the younger daughter, Jane, came of age in three years' time. When Jane reached 21, in 1790, Perceval's career was still not prospering, and Sir Thomas still opposed the marriage.

The couple eloped and married by special licence in East Grinstead. They set up home together in lodgings over a carpet shop in Bedford Row, later moving to

As the second son of a second marriage, and with an allowance of only £200 a year (), Perceval faced the prospect of having to make his own way in life. (Under primogeniture, the first son inherited land and title.) He chose the law as a profession, studied at Lincoln's Inn, and was called to the bar in 1786. Perceval's mother had died in 1783. Perceval and his brother Charles, now Lord Arden, rented a house in Charlton, where they fell in love with two sisters who were living in the Percevals' old childhood home. The sisters' father, Sir Thomas Spencer Wilson, approved of the match between his eldest daughter Margaretta and Lord Arden, who was wealthy and already a Member of Parliament and a Lord of the Admiralty. Perceval, who was at that time an impecunious barrister on the Midland Circuit, was told to wait until the younger daughter, Jane, came of age in three years' time. When Jane reached 21, in 1790, Perceval's career was still not prospering, and Sir Thomas still opposed the marriage.

The couple eloped and married by special licence in East Grinstead. They set up home together in lodgings over a carpet shop in Bedford Row, later moving to Lindsey House

Lindsey House is a Grade II* listed villa in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, London. It is owned by the National Trust but tenanted and only open by special arrangement.

This house should not be confused with the eponymous 1640 house in Lincoln's Inn Fiel ...

, Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in develo ...

. They had thirteen children together.

Perceval's family connections obtained a number of positions for him: Deputy Recorder of Northampton, and commissioner of bankrupts in 1790; surveyor of the Maltings and clerk of the irons in the mint– a sinecure worth £119 a year – in 1791; and counsel to the Board of Admiralty in 1794. He acted as junior counsel for the Crown in the prosecutions of Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

''in absentia

is Latin for absence. , a legal term, is Latin for "in the absence" or "while absent".

may also refer to:

* Award in absentia

* Declared death in absentia, or simply, death in absentia, legally declared death without a body

* Election in ab ...

'' for seditious libel

Sedition and seditious libel were criminal offences under English common law, and are still criminal offences in Canada. Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection ...

(1792), and John Horne Tooke

John Horne Tooke (25 June 1736 – 18 March 1812), known as John Horne until 1782 when he added the surname of his friend William Tooke to his own, was an English clergyman, politician, and philologist. Associated with radical proponents of parl ...

for high treason (1794). Perceval joined the London and Westminster Light Horse Volunteers in 1794 when the country was under threat of invasion by France and served with them until 1803.

Perceval wrote anonymous pamphlets in favour of the impeachment of Warren Hastings

The impeachment of Warren Hastings, the first governor-general of Bengal, was attempted between 1787 and 1795 in the Parliament of Great Britain. Hastings was accused of misconduct during his time in Calcutta, particularly relating to mismanageme ...

, and in defence of public order against sedition. These pamphlets brought him to the attention of William Pitt the Younger

William Pitt the Younger (28 May 175923 January 1806) was a British statesman, the youngest and last prime minister of Great Britain (before the Acts of Union 1800) and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom (of Great Britain and Ire ...

, and in 1795 he was offered the appointment of Chief Secretary for Ireland. He declined the offer. He could earn more as a barrister and needed the money to support his growing family. In 1796 he became a King's Counsel and had an income of about £1,000 a year (). Perceval was 33 when he became a KC, making him one of the youngest ever.

Early political career: 1796–1801

In 1796, Perceval's uncle, the 8th Earl of Northampton, died. Perceval's cousin Charles Compton, who was MP for Northampton, succeeded to the earldom and took his place in theHouse of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

. Perceval was invited to stand for election in his place. In the May by-election he was elected unopposed, but weeks later had to defend his seat in a fiercely contested general election. Northampton had an electorate of about one thousand – every male householder not in receipt of poor relief had a vote – and the town had a strong radical tradition. Perceval stood for the Castle Ashby

Castle Ashby is the name of a civil parish, an estate village and an English country house in rural Northamptonshire. Historically the village was set up to service the needs of Castle Ashby House, the seat of the Marquess of Northampton. The v ...

interest, Edward Bouverie for the Whigs, and William Walcot for the corporation. After a disputed count, Perceval and Bouverie were returned. Perceval represented Northampton until his death 16 years later, and is the only MP for Northampton to have held the office of prime minister. 1796 was his first and last contested election; in the general elections of 1802, 1806 and 1807, Perceval and Bouverie were returned unopposed.

When Perceval took his seat in the House of Commons in September 1796, his political views were already formed. "He was for the constitution and Pitt; he was against Fox

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelve sp ...

and France", wrote his biographer Denis Gray. During the 1796–1797 session, he made several speeches, always reading from notes. His public speaking skills had been sharpened at the Crown and Rolls debating society when he was a law student. After taking his seat in the House of Commons, Perceval continued with his legal practice, as MPs did not receive a salary, and the House only sat for a part of the year. During the Parliamentary recess of the summer of 1797, he was senior counsel for the Crown in the prosecution of John Binns for sedition. Binns, who was defended by Samuel Romilly, was found not guilty. The fees from his legal practice allowed Perceval to take out a lease on a country house, Belsize House in Hampstead.

It was during the next session of Parliament, in January 1798, that Perceval established his reputation as a debater – and his prospects as a future minister – with a speech in support of the Assessed Taxes Bill (a bill to increase the taxes on houses, windows, male servants, horses and carriages, in order to finance the war against France). He used the occasion to mount an attack on Charles Fox and his demands for reform. Pitt described the speech as one of the best he had ever heard, and later that year Perceval was appointed to the post of Solicitor to the Ordnance.

Solicitor and attorney general: 1801–1806

Pitt resigned in 1801 when the King and Cabinet opposed his bill for Catholic emancipation. As Perceval shared the King's views on Catholic emancipation, he did not feel obliged to follow Pitt into opposition. His career continued to prosper during Henry Addington's administration. He was appointed solicitor general in 1801 and attorney general the following year. Perceval did not agree with Addington's general policies (especially on foreign policy), and confined himself to speeches on legal issues. He was retained in the position of attorney general when Addington resigned, and Pitt formed his second ministry in 1804. As attorney general, Perceval was involved with the prosecution of radicalsEdward Despard

Edward Marcus Despard (175121 February 1803), an Irish officer in the service of the British Crown, gained notoriety as a colonial administrator for refusing to recognise racial distinctions in law and, following his recall to London, as a republi ...

and William Cobbett

William Cobbett (9 March 1763 – 18 June 1835) was an English pamphleteer, journalist, politician, and farmer born in Farnham, Surrey. He was one of an agrarian faction seeking to reform Parliament, abolish "rotten boroughs", restrain foreign ...

, but was also responsible for more liberal decisions on trade unions, and for improving the conditions of convicts transported

''Transported'' is an Australian convict melodrama film directed by W. J. Lincoln. It is considered a lost film.

Plot

In England, Jessie Grey is about to marry Leonard Lincoln but the evil Harold Hawk tries to force her to marry him and she w ...

to New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

.

When Pitt died, in January 1806, Perceval was an emblem bearer at his funeral. Although he had little money to spare (by now he had eleven children), he contributed £1,000 towards a fund to pay off Pitt's debts. He resigned as attorney general, refusing to serve in Lord Grenville

William Wyndham Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville, (25 October 175912 January 1834) was a British Pittite Tory politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1806 to 1807, but was a supporter of the Whigs for the duration of ...

's ministry of "all the talents", as it included Fox. Instead he became the leader of the Pittite opposition in the House of Commons.

During his period in opposition, Perceval used his legal skills to defend Princess Caroline, the estranged wife of the Prince of Wales, during the " delicate investigation". The Princess had been accused of giving birth to an illegitimate child, and the Prince of Wales ordered an inquiry, hoping to obtain evidence for a divorce. The government inquiry found that the main accusation was untrue (the child in question had been adopted by the Princess), but it was critical of the behaviour of the Princess. The opposition sprang to her defence and Perceval became her advisor, drafting a 156-page letter to King George III in her support. Known as , it was described by Perceval's biographer as "the last and greatest production of his legal career". When the King refused to let Caroline return to court, Perceval threatened publication of ''The Book'', but Grenville's ministry fell – again over a difference of opinion with the King on the Catholic question – before ''The Book'' could be distributed. As a member of the new government, Perceval drafted a cabinet minute acquitting Caroline on all charges and recommending her return to court. He had a bonfire of ''The Book'' at Lindsey House, and large sums of government money were spent on buying back stray copies. A few remained at large and ''The Book'' was published soon after his death.

Chancellor of the Exchequer: 1807–1809

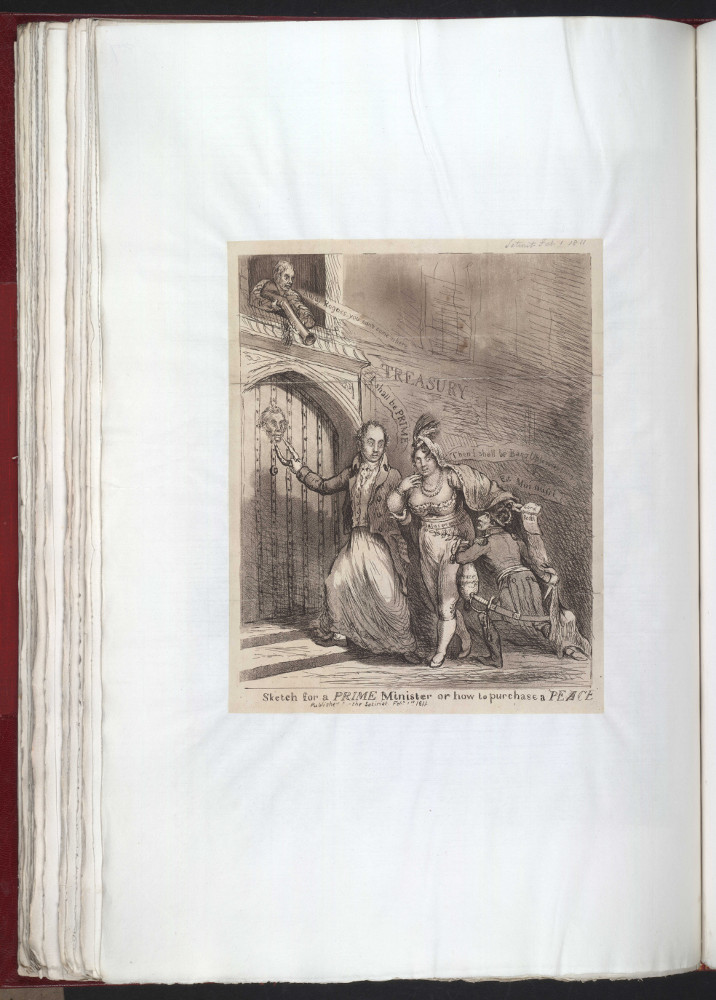

On the resignation of Grenville, the Duke of Portland put together a ministry of Pittites and asked Perceval to become Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons. Perceval would have preferred to remain attorney general or become

On the resignation of Grenville, the Duke of Portland put together a ministry of Pittites and asked Perceval to become Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons. Perceval would have preferred to remain attorney general or become Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national s ...

, and pleaded ignorance of financial affairs. He agreed to take the position when the salary (smaller than that of the Home Office) was augmented by the Duchy of Lancaster

The Duchy of Lancaster is the private estate of the British sovereign as Duke of Lancaster. The principal purpose of the estate is to provide a source of independent income to the sovereign. The estate consists of a portfolio of lands, properti ...

. Lord Hawkesbury

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. He held many important cabinet offices such as Foreign Secret ...

(later Liverpool) recommended Perceval to the King by explaining that he came from an old English family and shared the King's views on the Catholic question.

Perceval's youngest child, Ernest Augustus, was born soon after Perceval became chancellor (Princess Caroline was godmother). Jane Perceval became ill after the birth and the family moved out of the damp and draughty Belsize House, spending a few months in Lord Teignmouth's house in Clapham

Clapham () is a suburb in south west London, England, lying mostly within the London Borough of Lambeth, but with some areas (most notably Clapham Common) extending into the neighbouring London Borough of Wandsworth.

History

Early history ...

before finding a suitable country house in Ealing. Elm Grove was a 16th-century house that had been the home of the Bishop of Durham; Perceval paid £7,500 for it in 1808 (borrowing from his brother Lord Arden and the trustees of Jane's dowry), and the Perceval family's long association with Ealing began. Meanwhile, in town, Perceval had moved from Lindsey House into 10 Downing Street, when the Duke of Portland moved back to Burlington House shortly after becoming prime minister.

One of Perceval's first tasks in Cabinet was to expand the Orders in Council

An Order-in-Council is a type of legislation in many countries, especially the Commonwealth realms. In the United Kingdom this legislation is formally made in the name of the monarch by and with the advice and consent of the Privy Council (''King ...

that had been brought in by the previous administration and were designed to restrict the trade of neutral countries with France, in retaliation to Napoleon's embargo on British trade. He was also responsible for ensuring that Wilberforce's bill on the abolition of the slave trade, which had still not passed its final stages in the House of Lords when Grenville's ministry fell, would not "fall between the two ministries" and be rejected in a snap division. Perceval was one of the founding members of the African Institute, which was set up in April 1807 to safeguard the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act.

As Chancellor of the Exchequer, Perceval had to raise money to finance the war against Napoleon. This he managed to do in his budgets of 1808 and 1809 without increasing taxes, by raising loans at reasonable rates and making economies. As leader of the House of Commons, he had to deal with a strong opposition, which challenged the government over the conduct of the war, Catholic emancipation, corruption, and Parliamentary reform. Perceval successfully defended the commander-in-chief of the army, the Duke of York, against charges of corruption when the Duke's ex-mistress Mary Anne Clarke claimed to have sold army commissions with his knowledge. Although Parliament voted to acquit the Duke of the main charge, his conduct was criticised, and he accepted Perceval's advice to resign. (He was re-instated in 1811).

Portland's ministry contained three future prime-ministers – Perceval, Lord Hawkesbury

Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a British Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1812 to 1827. He held many important cabinet offices such as Foreign Secret ...

and George Canning – as well as another two of the 19th-century's great statesmen: Lord Eldon

Earl of Eldon, in the County Palatine of Durham, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1821 for the lawyer and politician John Scott, 1st Baron Eldon, Lord Chancellor from 1801 to 1806 and again from 1807 to 1827. ...

and Lord Castlereagh

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, (18 June 1769 – 12 August 1822), usually known as Lord Castlereagh, derived from the courtesy title Viscount Castlereagh ( ) by which he was styled from 1796 to 1821, was an Anglo-Irish politician ...

. But Portland was not a strong leader and his health was failing. The country was plunged into political crisis in the summer of 1809 as Canning schemed against Castlereagh, and the Duke of Portland resigned following a stroke. Negotiations began to find a new prime minister: Canning wanted to be either prime minister or nothing, Perceval was prepared to serve under a third person, but not Canning. The remnants of the cabinet decided to invite Lord Grey and Lord Grenville to form "an extended and combined administration" in which Perceval was hoping for the home secretaryship. But Grenville and Grey refused to enter into negotiations, and the King accepted the Cabinet's recommendation of Perceval for his new prime minister.

Perceval kissed the King's hands on 4 October and set about forming his Cabinet, a task made more difficult by the fact that Castlereagh and Canning had ruled themselves out of consideration by fighting a duel (which Perceval had tried to prevent). Having received five refusals for the office, he had to serve as his own Chancellor of the Exchequer – characteristically declining to accept the salary.

Prime Minister: 1809–1812

The new ministry was not expected to last. It was especially weak in the Commons, where Perceval had only one cabinet member– Home Secretary Richard Ryder – and had to rely on the support of backbenchers in debate. In the first week of the new Parliamentary session in January 1810 the government lost four divisions, one on a motion for an inquiry into theWalcheren Expedition

The Walcheren Campaign ( ) was an unsuccessful British expedition to the Netherlands in 1809 intended to open another front in the Austrian Empire's struggle with France during the War of the Fifth Coalition. Sir John Pitt, 2nd Earl of Chath ...

(in which, the previous summer, a military force intending to seize Antwerp had instead withdrawn after losing many men to an epidemic on the island of Walcheren off the Dutch coast) and three on the composition of the finance committee. The government survived the inquiry into the Walcheren Expedition at the cost of the resignation of the expedition's leader Lord Chatham. The radical MP Sir Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartists) of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vo ...

was committed to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

for having published a letter in William Cobbett's ''Political Register

The ''Cobbett's Weekly Political Register'', commonly known as the ''Political Register'', was a weekly London-based newspaper founded by William Cobbett in 1802. It ceased publication in 1836, the year after Cobbett's death.

History

Originally ...

'' denouncing the government's exclusion of the press from the inquiry. It took three days, owing to various blunders, to execute the warrant for Burdett's arrest. The mob took to the streets in support of Burdett, troops were called out, and there were fatal casualties. As Chancellor, Perceval continued to find the funds to finance Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by metr ...

's campaign in the Iberian Peninsula, whilst contracting a lower debt than his predecessors or successors.

King George III had celebrated his Golden Jubilee in 1809; by the following autumn he was showing signs of a return of the illness that had led to the threat of a Regency in 1788. The prospect of a Regency was not attractive to Perceval, as the Prince of Wales was known to favour Whigs and disliked Perceval for the part he had played in the "delicate investigation". Twice Parliament was adjourned in November 1810, as doctors gave optimistic reports about the King's chances of a return to health. In December select committees of the Lords and Commons heard evidence from the doctors, and Perceval finally wrote to the Prince of Wales on 19 December saying that he planned the next day to introduce a regency bill. As with Pitt's bill in 1788, there would be restrictions: the regent's powers to create peers and award offices and pensions would be restricted for 12 months,

King George III had celebrated his Golden Jubilee in 1809; by the following autumn he was showing signs of a return of the illness that had led to the threat of a Regency in 1788. The prospect of a Regency was not attractive to Perceval, as the Prince of Wales was known to favour Whigs and disliked Perceval for the part he had played in the "delicate investigation". Twice Parliament was adjourned in November 1810, as doctors gave optimistic reports about the King's chances of a return to health. In December select committees of the Lords and Commons heard evidence from the doctors, and Perceval finally wrote to the Prince of Wales on 19 December saying that he planned the next day to introduce a regency bill. As with Pitt's bill in 1788, there would be restrictions: the regent's powers to create peers and award offices and pensions would be restricted for 12 months, the Queen

In the English-speaking world, The Queen most commonly refers to:

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 1952 until her death

The Queen may also refer to:

* Camilla, Queen Consort (born 1947), ...

would be responsible for the care of the King, and the King's private property would be looked after by trustees.

The Prince of Wales, supported by the Opposition, objected to the restrictions, but Perceval steered the bill through Parliament. Everyone had expected the Regent to change his ministers but, surprisingly, he chose to retain his old enemy Perceval. The official reason given by the Regent was that he did not wish to do anything to aggravate his father's illness. The King assented to the Regency Bill on 5 February, the Regent took the royal oath the following day and Parliament formally opened for the 1811 session. The session was largely taken up with problems in Ireland, economic depression and the bullion controversy in England (a bill was passed to make bank notes legal tender), and military operations in the peninsula.

The restrictions on the Regency expired in February 1812, the King was still showing no signs of recovery, and the Prince Regent decided, after an unsuccessful attempt to persuade Grey and Grenville to join the government, to retain Perceval and his ministers. Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, after intrigues with the Prince Regent, resigned as foreign secretary and was replaced by Castlereagh. The opposition meanwhile was mounting an attack on the Orders in Council, which had caused a crisis in relations with America and were widely blamed for depression and unemployment in England. Rioting had broken out in the Midlands and North, and been harshly repressed. Henry Brougham's motion for a select committee was defeated in the Commons, but, under continuing pressure from manufacturers, the government agreed to set up a Committee of the Whole House to consider the Orders in Council and their impact on trade and manufacture. The committee began its examination of witnesses in early May 1812.

Assassination

At 5:15 pm, on the evening of 11 May 1812, Perceval was on his way to attend the inquiry into the Orders in Council. As he entered the lobby of the House of Commons, a man stepped forward, drew a pistol and shot him in the chest. Perceval fell to the floor, after uttering something that was variously heard as "murder" and "oh my God". They were his last words. By the time he had been carried into an adjoining room and propped up on a table with his feet on two chairs, he was senseless, although there was still a faint pulse. When a surgeon arrived a few minutes later, the pulse had stopped, and Perceval was declared dead.

At first it was feared that the shot might signal the start of an uprising, but it soon became apparent that the assassin – who had made no attempt to escape – was a man with an obsessive grievance against the Government and had acted alone. The assassin,

At 5:15 pm, on the evening of 11 May 1812, Perceval was on his way to attend the inquiry into the Orders in Council. As he entered the lobby of the House of Commons, a man stepped forward, drew a pistol and shot him in the chest. Perceval fell to the floor, after uttering something that was variously heard as "murder" and "oh my God". They were his last words. By the time he had been carried into an adjoining room and propped up on a table with his feet on two chairs, he was senseless, although there was still a faint pulse. When a surgeon arrived a few minutes later, the pulse had stopped, and Perceval was declared dead.

At first it was feared that the shot might signal the start of an uprising, but it soon became apparent that the assassin – who had made no attempt to escape – was a man with an obsessive grievance against the Government and had acted alone. The assassin, John Bellingham

John Bellingham (176918 May 1812) was an English merchant and perpetrator of the 1812 murder of Spencer Perceval, the only British prime minister to be assassinated.

Early life

Bellingham's early life is largely unknown, and most post-assass ...

, was a merchant who believed he had been unjustly imprisoned in Russia and was entitled to compensation from the government, but all his petitions had been rejected. Perceval's body was laid on a sofa in the speaker's drawing room and removed to Number 10 in the early hours of 12 May. That same morning an inquest was held at the Cat and Bagpipes public house on the corner of Downing Street and a verdict of wilful murder was returned.

Perceval left a widow and twelve children aged between three and twenty, and there were soon rumours that he had not left them well provided for. He had just £106 5s 1d in the bank when he died. A few days after his death, Parliament voted to settle £50,000 on Perceval's children, with additional annuities for his widow and eldest son. Jane Perceval married Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Henry Carr, brother of the Reverend Robert James Carr

Robert James Carr (1774–1841) was an English churchman, Bishop of Chichester in 1824 and Bishop of Worcester in 1831.

Early life

Born 9 May 1774 and christened 9 June at Feltham

Feltham () is a town in West London, England, from Char ...

, then Vicar of Brighton, in 1815 and was widowed again six years later. She died aged 74 in 1844.

Perceval was buried on 16 May 1812 in the Egmont vault at St Luke's Church, Charlton

St Luke's Church in Charlton, London, England, is an Anglican parish church in the Diocese of Southwark.

Records suggest that a church dedicated to St Luke existed on the site around 1077. It was rebuilt in 1630 with funds provided by Sir Ad ...

, London. At his widow's request, it was a private funeral. Lord Eldon, Lord Liverpool, Lord Harrowby and Richard Ryder were the pall-bearers. The previous day, Bellingham had been tried, and, refusing to enter a plea of insanity, was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was executed by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

on 18 May.

Legacy

Perceval was a small, slight, and very pale man, who usually dressed in black. Lord Eldon called him "Little P". He never sat for a full-sized portrait; likenesses are either miniatures or are based on a death mask byJoseph Nollekens

Joseph Nollekens R.A. (11 August 1737 – 23 April 1823) was a sculptor from London generally considered to be the finest British sculptor of the late 18th century.

Life

Nollekens was born on 11 August 1737 at 28 Dean Street, Soho, London, ...

. Perceval was the last British prime minister to wear a powdered wig tied in a queue, and knee-breeches

Breeches ( ) are an article of clothing covering the body from the waist down, with separate coverings for each leg, usually stopping just below the knee, though in some cases reaching to the ankles. Formerly a standard item of Western men's cl ...

according to the old-fashioned style of the 18th century. He is sometimes referred to as one of Britain's forgotten prime ministers, remembered only for the manner of his death. Although not considered an inspirational leader, he is generally seen as a devout, industrious, principled man who at the head of a weak government steered the country through difficult times. A contemporary MP Henry Grattan

Henry Grattan (3 July 1746 – 4 June 1820) was an Irish politician and lawyer who campaigned for legislative freedom for the Irish Parliament in the late 18th century from Britain. He was a Member of the Irish Parliament (MP) from 1775 to 18 ...

, used a naval analogy to describe Perceval: "He is not a ship-of-the-line, but he carries many guns, is tight-built and is out in all weathers". Perceval's modern biographer, Denis Gray, described him as "a herald of the Victorians".

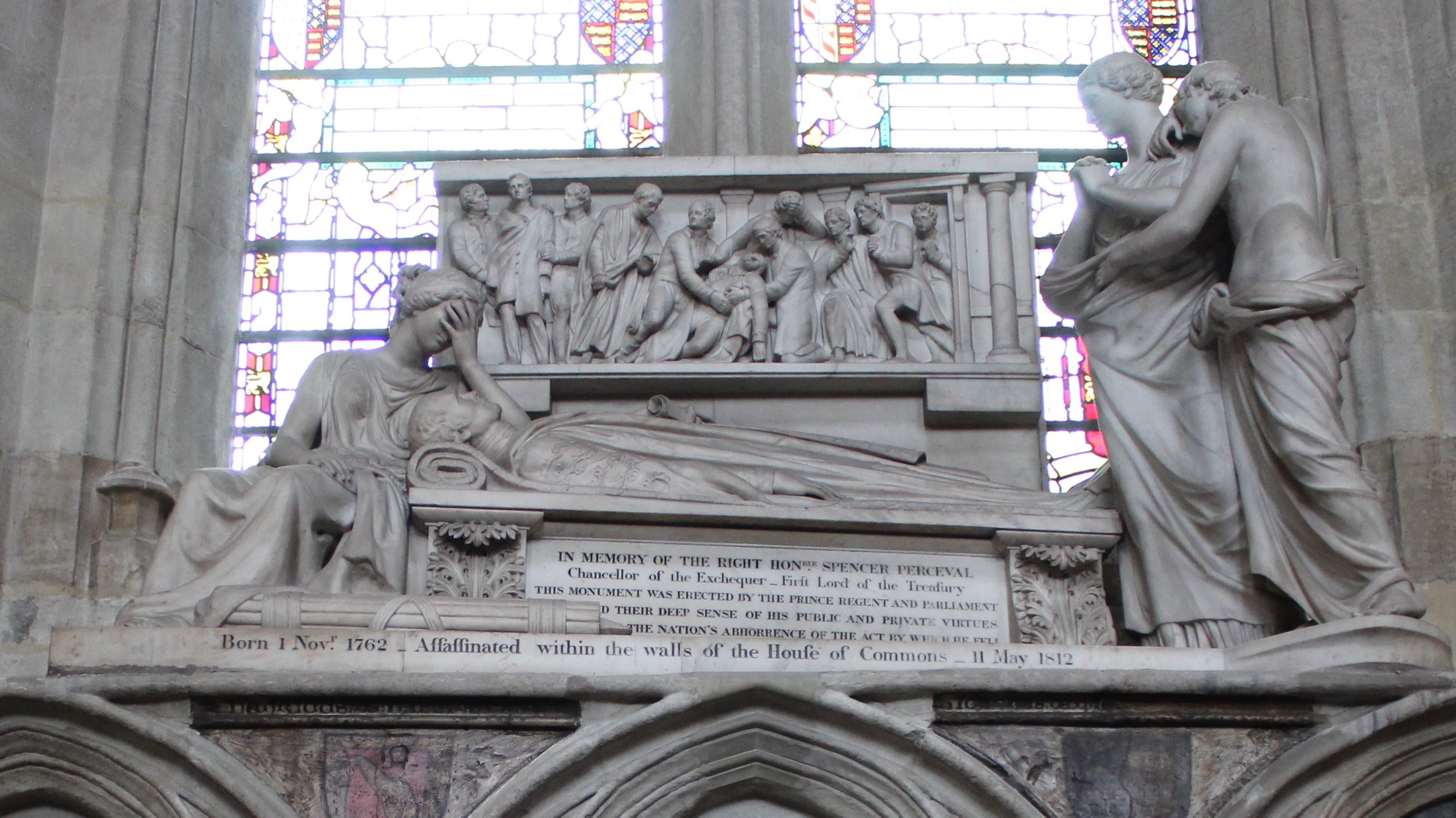

Perceval was mourned by many; Lord Chief Justice Sir James Mansfield wept during his summing up to the jury at Bellingham's trial. However, in some quarters he was unpopular and in

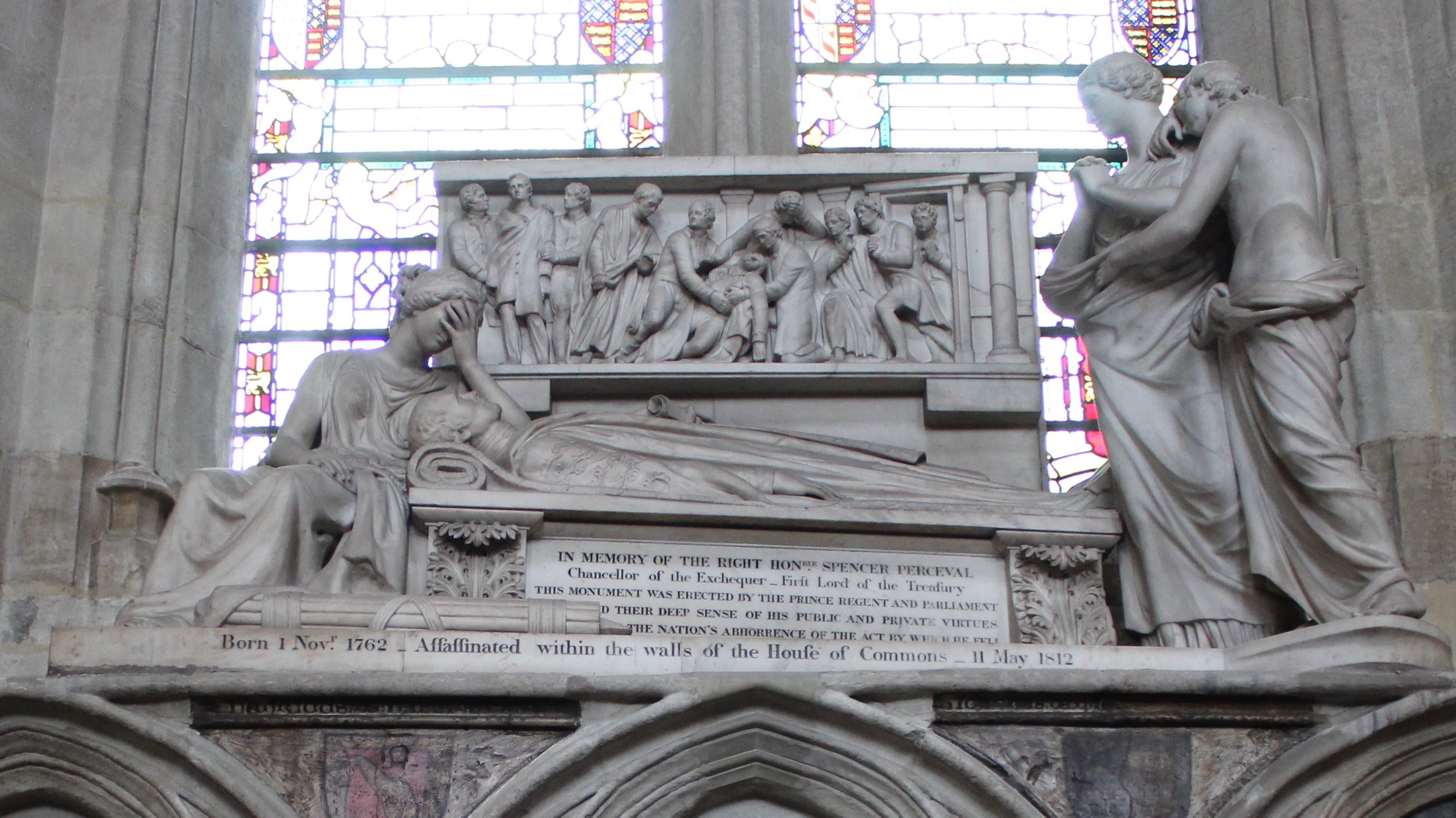

Perceval was mourned by many; Lord Chief Justice Sir James Mansfield wept during his summing up to the jury at Bellingham's trial. However, in some quarters he was unpopular and in Nottingham

Nottingham ( , locally ) is a city and unitary authority area in Nottinghamshire, East Midlands, England. It is located north-west of London, south-east of Sheffield and north-east of Birmingham. Nottingham has links to the legend of Robi ...

the crowds that gathered following his assassination were in a more cheerful mood. Public monuments to Perceval were erected in Northampton, Lincoln's Inn and in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the Unite ...

. The memorial in Westminster Abbey, by the sculptor Richard Westmacott

Sir Richard Westmacott (15 July 17751 September 1856) was a British sculptor.

Life and career

Westmacott studied with his father, also named Richard Westmacott, at his studio in Mount Street, off Grosvenor Square in London before going t ...

, has an effigy of the dead Perceval with mourning figures representing Truth, Temperance and Power in front of a relief depicting the aftermath of the assassination in the House of Commons. Four biographies have been published: a book on his life and administration by Charles Verulam Williams, which appeared soon after his death; his grandson Spencer Walpole's biography in 1894; Philip Treherne's short biography in 1909; Denis Gray's 500-page political biography in 1963. In addition, there are three books about his assassination, one by Mollie Gillen

Mollie Gillen (née Woolnough; 1908–2009) was an Australian historian, researcher, writer and novelist. Her work on the First Fleet, in ''The Search for John Small, First Fleeter'' and ''The Founders of Australia: a Biographical Dictionary ...

, one by David Hanrahan, and the latest by Andro Linklater entitled ''Why Spencer Perceval Had to Die''.

Perceval's assassination inspired poems such as ''Universal sympathy on the martyr'd statesman'' (1812):

One of Perceval's most noted critics, especially on the question of Catholic emancipation, was the cleric

Perceval's assassination inspired poems such as ''Universal sympathy on the martyr'd statesman'' (1812):

One of Perceval's most noted critics, especially on the question of Catholic emancipation, was the cleric Sydney Smith

Sydney Smith (3 June 1771 – 22 February 1845) was an English wit, writer, and Anglican cleric.

Early life and education

Born in Woodford, Essex, England, Smith was the son of merchant Robert Smith (1739–1827) and Maria Olier (1750–1801) ...

. In ''Peter Plymley's Letters'' Smith writes:

If I lived at Hampstead upon stewed meats and claret; if I walked to church every Sunday before eleven young gentlemen of my own begetting, with their faces washed, and their hair pleasingly combed; if the Almighty had blessed me with every earthly comfort–how awfully would I pause before I sent forth the flame and the sword over the cabins of the poor, brave, generous, open-hearted peasants of Ireland!American historian

Henry Adams

Henry Brooks Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, descended from two U.S. Presidents.

As a young Harvard graduate, he served as secretary to his father, Charles Fr ...

suggested that it was this picture of Perceval that stayed in the minds of Liberals for a whole generation.

In July 2014, a memorial plaque was unveiled in St Stephen's Hall of the Houses of Parliament, close to where he was killed. The plaque had been proposed by Michael Ellis, Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

MP for Northampton North (parts of which Perceval once represented).

In streets in Northampton and Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It is ...

his name is memorialised as it is by the main streets set back behind two sides of Northampton Square

Northampton Square, a green town square, is in a corner of Clerkenwell projecting into Finsbury, in Central London. It is between Goswell Road and St John Street (and Spencer and Percival Streets), has a very broad pedestrian walkway on the no ...

, London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

: Spencer and Percival Streets.

Family

Spencer and Jane Perceval had thirteen children, of whom twelve survived to adulthood. Four of the daughters never married, and lived together all their lives. During their mother's life, they lived with her in Elm Grove, Ealing; after her death, the sisters moved to nearby Pitzhanger Manor House, while their brother Spencer took over Elm Grove.Cousin marriage

A cousin marriage is a marriage where the spouses are cousins (i.e. people with common grandparents or people who share other fairly recent ancestors). The practice was common in earlier times, and continues to be common in some societies toda ...

was common: the remaining two daughters and two of the sons took this path.

# Jane (1791–1824) married her cousin Edward Perceval, son of Lord Arden, in 1821 and lived in Felpham

Felpham (, sometimes pronounced locally as ''Felf-fm'') is a village and civil parish in the Arun District of West Sussex, England. Although sometimes considered part of the urban area of greater Bognor Regis, it is a village and civil parish in ...

, Sussex. She died three years after marrying, apparently in childbirth.

# Frances (1792–1877) lived with three unmarried sisters.

# Maria (1794–1877) lived with her three unmarried sisters.

# Spencer (1795–1859) was, like his father, educated at Harrow and Trinity College, Cambridge. After Perceval's assassination, Spencer junior was voted an annuity of £1000 (), free legal training at Lincoln's Inn and a tellership of the Exchequer, all of which left him financially secure. He became a Member of Parliament at the age of 22 and in 1821 married Anna, a daughter of the chief of the clan Macleod

Clan MacLeod (; gd, Clann Mac Leòid ) is a Highland Scottish clan associated with the Isle of Skye. There are two main branches of the clan: the MacLeods of Harris and Dunvegan, whose chief is MacLeod of MacLeod, are known in Gaelic as ' ("se ...

, with whom he had eleven children. He joined the Catholic Apostolic Church

The Catholic Apostolic Church (CAC), also known as the Irvingian Church, is a Christian denomination and Protestant sect which originated in Scotland around 1831 and later spread to Germany and the United States.metropolitan lunacy commissioner.

# Charles (born and died 1796)

# Frederick James (1797–1861) was the only one of Perceval's sons not to go to Harrow. Due to his fragile health he was sent to school at

online

*

Spencer Perceval, the assassinated prime minister that history forgot

in ''

Spencer Perceval

on the Downing Street website

Articles about Spencer Perceval

on the website of All Saints Church, Ealing

at the National Archives

Spencer Perceval's assassination

in the

A short article about Spencer Perceval and Ealing

in the Ealing Civic Society newsletter * *

at Cracroft's Peerage

Spencer Perceval

in the Parliamentary Archives

Parliamentary Archives, Papers relating to Spencer Perceval (1762-1812)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Perceval, Spencer 1762 births 1812 deaths 19th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom People from Northamptonshire Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Assassinated English politicians Attorneys General for England and Wales Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster Chancellors of the Exchequer of Great Britain Deaths by firearm in London Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People educated at Harrow School People from Ealing Politicians from London Lawyers from London Male murder victims People murdered in Westminster Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom Solicitors General for England and Wales Tory MPs (pre-1834) Younger sons of earls Younger sons of barons Assassinated heads of government 19th-century heads of government Leaders of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies British MPs 1796–1800 Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies UK MPs 1801–1802 UK MPs 1802–1806 UK MPs 1806–1807 UK MPs 1807–1812 Tory prime ministers of the United Kingdom Assassinated British MPs

Rottingdean

Rottingdean is a village in the city of Brighton and Hove, on the south coast of England. It borders the villages of Saltdean, Ovingdean and Woodingdean, and has a historic centre, often the subject of picture postcards.

Name

The name Rotting ...

. He married for the first time in 1827, spent some time in Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded i ...

, Belgium, was a director of the Clerical, Medical and General Life Assurance Society and a justice of the peace for Middlesex and for Kent, but generally led a quiet and retired life. Widowed in 1843, he married for the second time the following year. A grandson, Frederick Joseph Trevelyan Perceval, who was a Canadian rancher, became the 10th ''de jure'' Earl of Egmont

Earl of Egmont was a title in the Peerage of Ireland, created in 1733 for John Perceval, 1st Viscount Perceval. It became extinct with the death of the twelfth earl in 2011.

History

The Percevals claimed to be an ancient Anglo-Norman family, ...

(he did not claim the title) and was the father of the 11th earl.

# Rev. Henry (1799–1885) was educated at Harrow, where he was the only Perceval to become head of school. He went to Brasenose College, Oxford. In 1826 he married his cousin Catherine Drummond. For 46 years Henry was the rector of Elmley Lovett

Elmley Lovett in Worcestershire, England is a civil parish whose residents' homes are quite loosely clustered east of its Hartlebury Trading Estate, as well as in minor neighbourhood Cutnall Green to the near south-east. The latter is a loosely ...

in Worcestershire.

# Dudley Montague (1800–1856) was educated at Harrow and Christ Church, Oxford. Like his brother Spencer, he was given free legal training at Lincoln's Inn but was not called to the bar. He spent two years as an administrator at the Cape of Good Hope, where he married a daughter of Gen. Sir Richard Bourke, future Governor of New South Wales, in 1827. Back in England he obtained a treasury post and defended his father's reputation after it was attacked in Napier's history of the Peninsular War. In 1853 he stood unsuccessfully against William Gladstone in the election for an MP to represent Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to th ...

.

# Isabella (1801–1886) married her cousin Spencer Horatio Walpole

Spencer Horatio Walpole (11 September 1806 – 22 May 1898) was a British Conservative Party politician who served three times as Home Secretary in the administrations of Lord Derby.

Background and education

Walpole was the second son of Tho ...

in 1835 and was the only one of Perceval's daughters to have children. Her husband was a lawyer who became an MP in 1846 and served as Home Secretary. They lived in the Hall on Ealing Green, next-door to Isabella's four unmarried sisters.

# John Thomas (1803–1876) was educated at Harrow. After a three-year career as an officer in the Grenadier Guards

"Shamed be whoever thinks ill of it."

, colors =

, colors_label =

, march = Slow: " Scipio"

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment ...

and a term at Oxford University, he spent three years in asylums and became a campaigner for reform of the Lunacy Laws. In 1832, just after his release from an asylum, he married a cheesemonger's daughter.

# Louisa (1804–1891) lived with her three unmarried sisters.

# Frederica (1805–1900) lived with her three unmarried sisters. In her will she left money to build All Saints Church, Ealing, in memory of her father (he was born on All Saints Day). It is also known as the Spencer Perceval Memorial Church.

# Ernest Augustus (1807–1896) was educated at Harrow. He spent nine years in the 15th Hussars, seven of them as a captain. In 1830, he married his cousin Beatrice Trevelyan, daughter of Sir John Trevelyan, 5th Baronet. The couple settled in Somerset and raised a large family, including antiquary Spencer George Perceval. Ernest served as private secretary to the Home Office on three occasions.

Arms

Cabinet of Spencer Perceval

See also

*Earl of Egmont

Earl of Egmont was a title in the Peerage of Ireland, created in 1733 for John Perceval, 1st Viscount Perceval. It became extinct with the death of the twelfth earl in 2011.

History

The Percevals claimed to be an ancient Anglo-Norman family, ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * Fulford, Roger. "Spencer Perceval" ''History Today'' (Feb 1952) 2#2 pp 95–100. * Gray, Denis. ''Spencer Perceval'' (Manchester University Press, 1963), full scholarly biography * * * * Pentland, Gordon. "'Now the great Man in the Parliament House is dead, we shall have a big Loaf!' Responses to the Assassination of Spencer Perceval." ''Journal of British Studies'' 51.2 (2012): 340-36online

*

External links

*Spencer Perceval, the assassinated prime minister that history forgot

in ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

''

Spencer Perceval

on the Downing Street website

Articles about Spencer Perceval

on the website of All Saints Church, Ealing

at the National Archives

Spencer Perceval's assassination

in the

Parliamentary Archives

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

A short article about Spencer Perceval and Ealing

in the Ealing Civic Society newsletter * *

at Cracroft's Peerage

Spencer Perceval

in the Parliamentary Archives

Parliamentary Archives, Papers relating to Spencer Perceval (1762-1812)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Perceval, Spencer 1762 births 1812 deaths 19th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom People from Northamptonshire Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Assassinated English politicians Attorneys General for England and Wales Chancellors of the Duchy of Lancaster Chancellors of the Exchequer of Great Britain Deaths by firearm in London Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom People educated at Harrow School People from Ealing Politicians from London Lawyers from London Male murder victims People murdered in Westminster Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom Solicitors General for England and Wales Tory MPs (pre-1834) Younger sons of earls Younger sons of barons Assassinated heads of government 19th-century heads of government Leaders of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies British MPs 1796–1800 Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies UK MPs 1801–1802 UK MPs 1802–1806 UK MPs 1806–1807 UK MPs 1807–1812 Tory prime ministers of the United Kingdom Assassinated British MPs