Spectral karyotype on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of

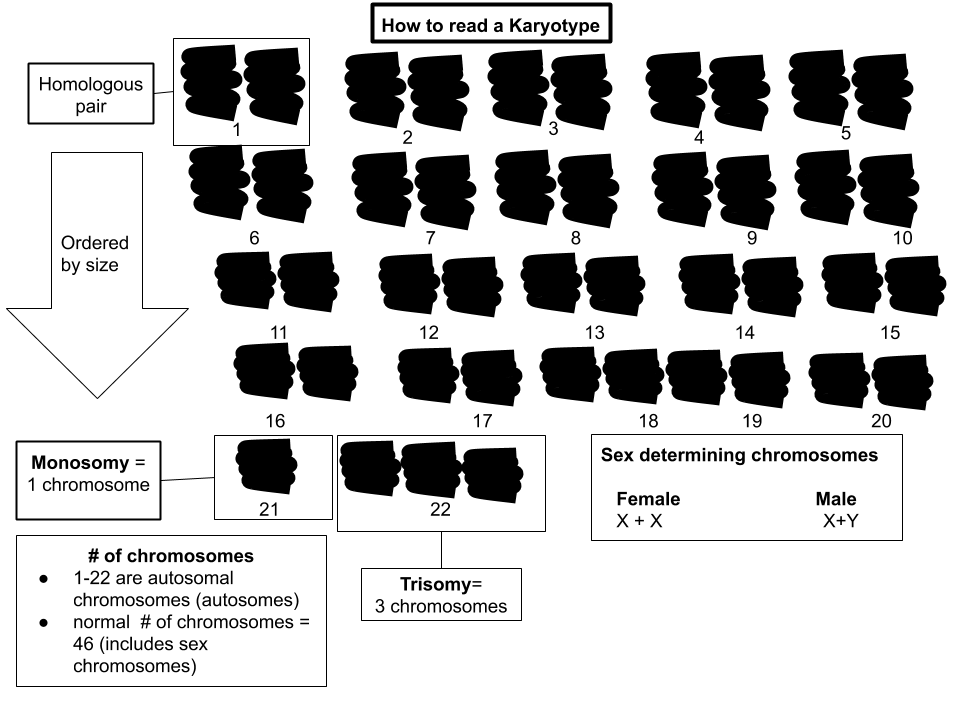

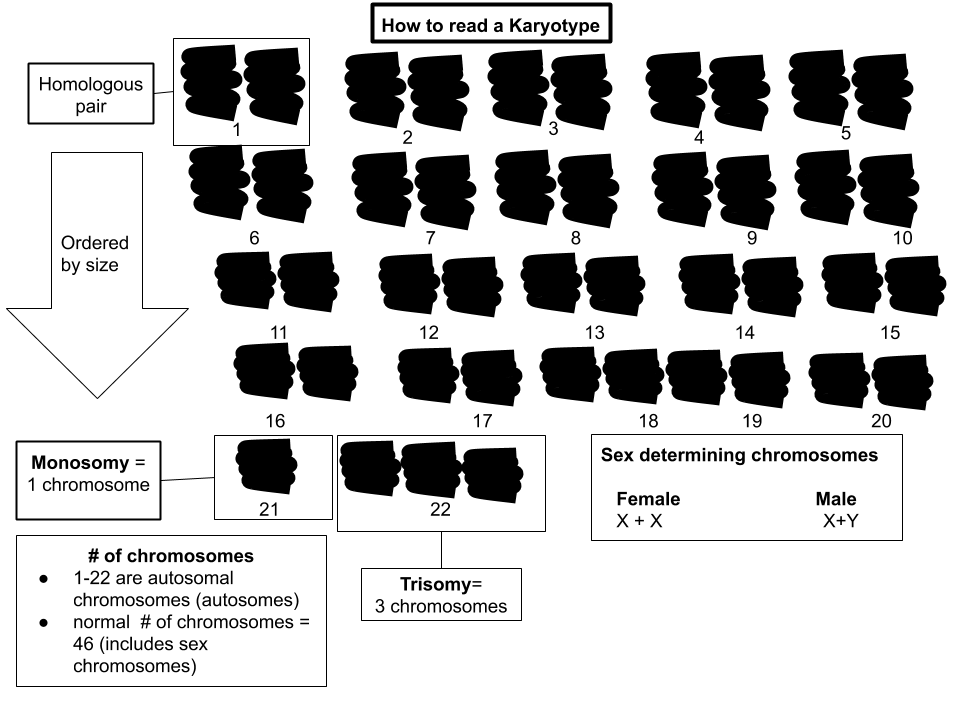

A karyogram or idiogram is a graphical depiction of a karyotype, wherein chromosomes are organized in pairs, ordered by size and position of centromere for chromosomes of the same size. Karyotyping generally combines light microscopy and

A karyogram or idiogram is a graphical depiction of a karyotype, wherein chromosomes are organized in pairs, ordered by size and position of centromere for chromosomes of the same size. Karyotyping generally combines light microscopy and

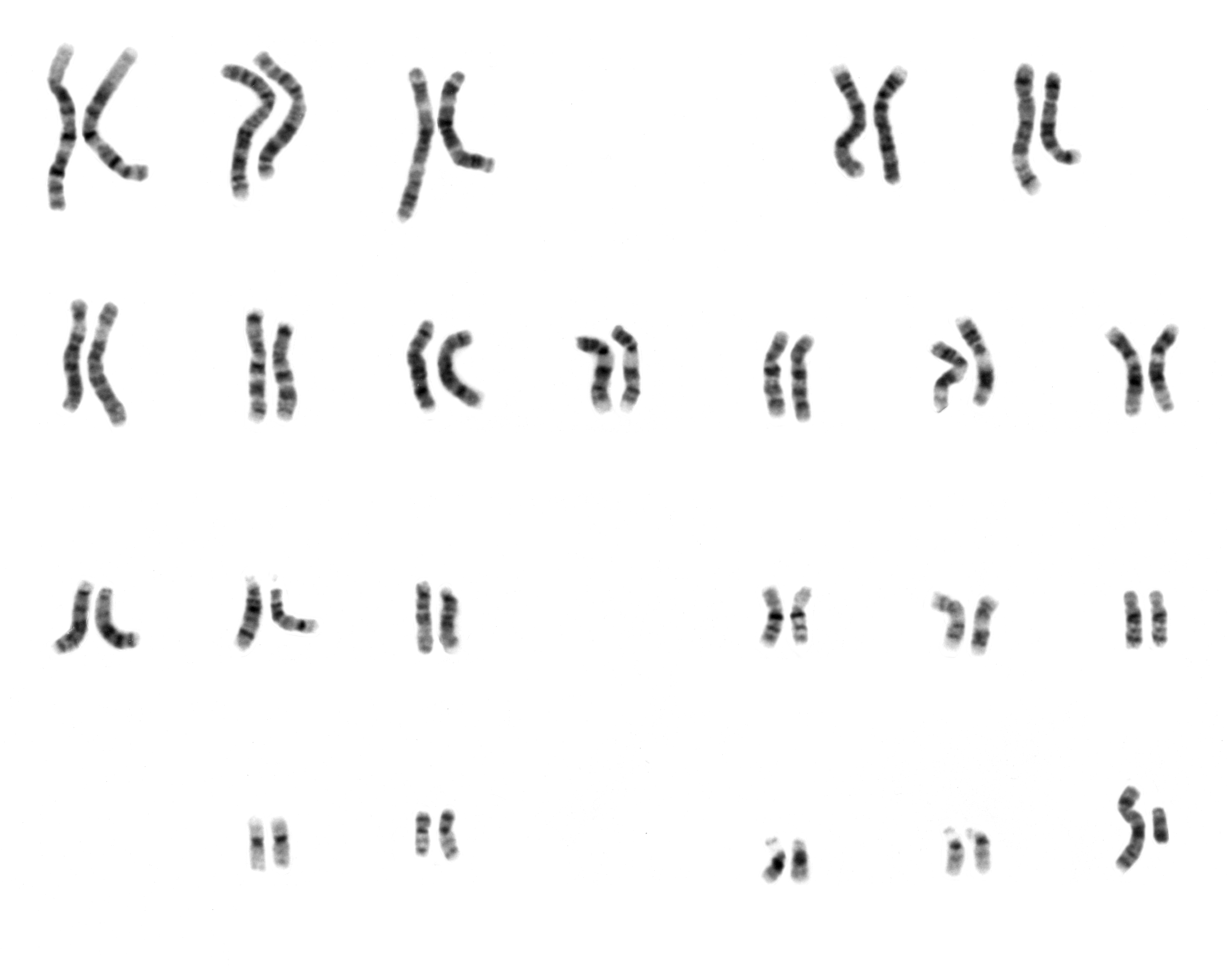

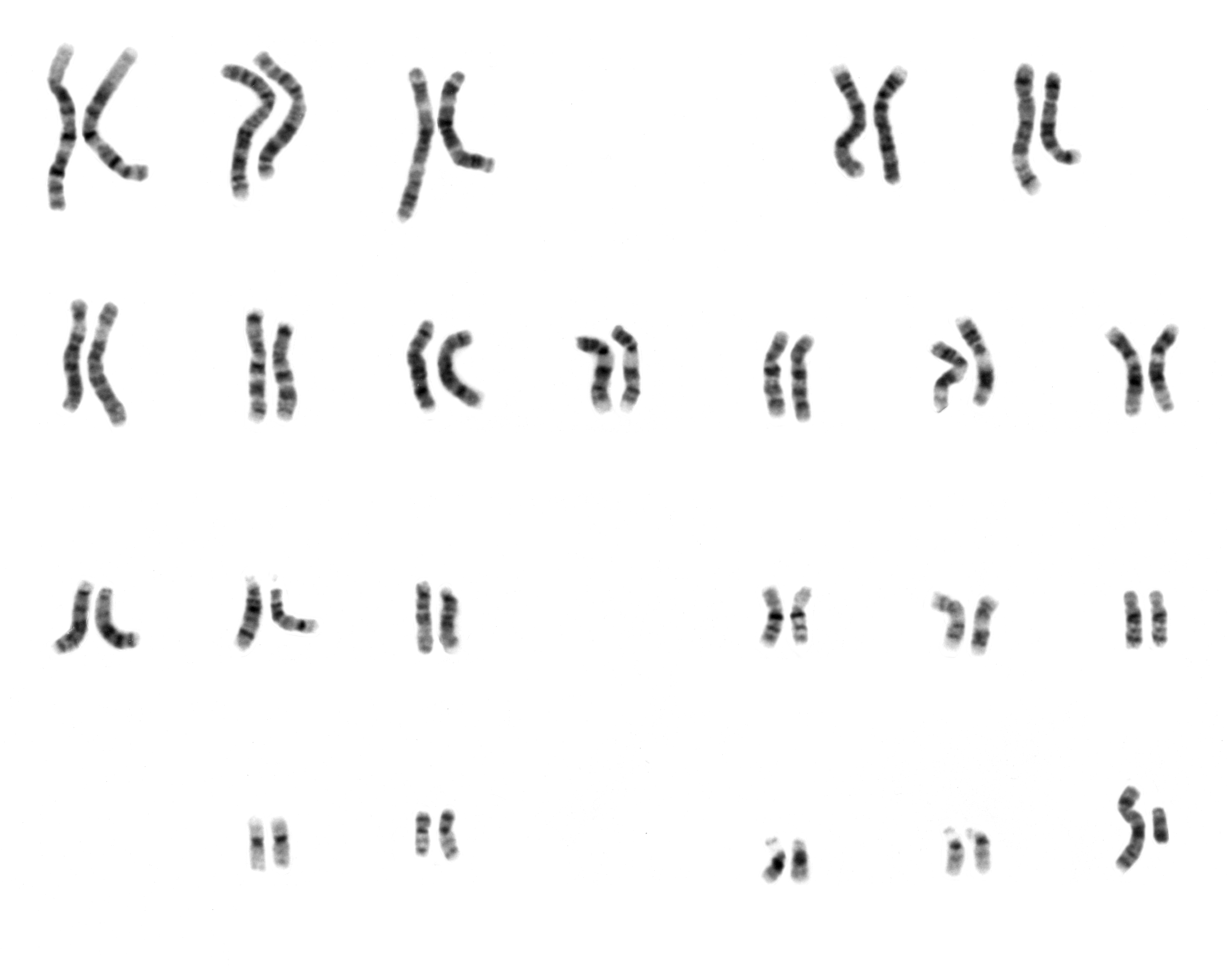

Both the micrographic and schematic karyograms shown in this section have a standard chromosome layout, and display dark and white regions as seen on

Both the micrographic and schematic karyograms shown in this section have a standard chromosome layout, and display dark and white regions as seen on

Schematic karyograms generally display a DNA copy number corresponding to the G0 phase of the cellular state (outside of the replicative

Schematic karyograms generally display a DNA copy number corresponding to the G0 phase of the cellular state (outside of the replicative

In many instances, endopolyploid nuclei contain tens of thousands of chromosomes (which cannot be exactly counted). The cells do not always contain exact multiples (powers of two), which is why the simple definition 'an increase in the number of chromosome sets caused by replication without cell division' is not quite accurate.

This process (especially studied in insects and some higher plants such as maize) may be a developmental strategy for increasing the productivity of tissues which are highly active in biosynthesis.

The phenomenon occurs sporadically throughout the eukaryote kingdom from protozoa to humans; it is diverse and complex, and serves differentiation and

In the "classic" (depicted) karyotype, a dye, often

In the "classic" (depicted) karyotype, a dye, often

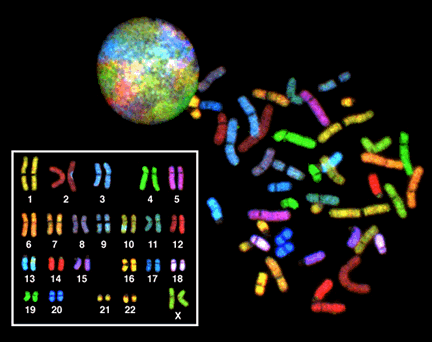

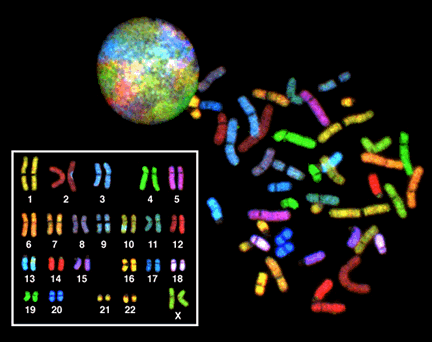

Multicolor

Multicolor

Alec MacAndrew; accessed 18 May 2006.Evidence of common ancestry: human chromosome 2

(video) 2007

Making a karyotype

an online activity from the University of Utah's Genetic Science Learning Center.

from the University of Arizona's Biology Project.

from Biology Corner, a resource site for biology and science teachers.

Bjorn Biosystems for Karyotyping and FISH

{{Use dmy dates, date=April 2017 Cell biology Chromosomes Cytogenetics Evolutionary biology Genetics techniques

metaphase

Metaphase ( and ) is a stage of mitosis in the eukaryotic cell cycle in which chromosomes are at their second-most condensed and coiled stage (they are at their most condensed in anaphase). These chromosomes, carrying genetic information, alig ...

chromosomes

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

in the cells of a species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is discerned by determining the chromosome complement of an individual, including the number of chromosomes and any abnormalities.

A karyogram or idiogram is a graphical depiction of a karyotype, wherein chromosomes are organized in pairs, ordered by size and position of centromere for chromosomes of the same size. Karyotyping generally combines light microscopy and

A karyogram or idiogram is a graphical depiction of a karyotype, wherein chromosomes are organized in pairs, ordered by size and position of centromere for chromosomes of the same size. Karyotyping generally combines light microscopy and photography

Photography is the art, application, and practice of creating durable images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is employe ...

, and results in a photomicrograph

A micrograph or photomicrograph is a photograph or digital image taken through a microscope or similar device to show a magnify, magnified image of an object. This is opposed to a macrograph or photomacrograph, an image which is also taken ...

ic (or simply micrographic) karyogram. In contrast, a schematic

A schematic, or schematic diagram, is a designed representation of the elements of a system using abstract, graphic symbols rather than realistic pictures. A schematic usually omits all details that are not relevant to the key information the ...

karyogram is a designed graphic representation of a karyotype. In schematic karyograms, just one of the sister chromatid

A chromatid (Greek ''khrōmat-'' 'color' + ''-id'') is one half of a duplicated chromosome. Before replication, one chromosome is composed of one DNA molecule. In replication, the DNA molecule is copied, and the two molecules are known as chro ...

s of each chromosome is generally shown for brevity, and in reality they are generally so close together that they look as one on photomicrographs as well unless the resolution is high enough to distinguish them. The study of whole sets of chromosomes is sometimes known as karyology.

Karyotypes describe the chromosome count of an organism and what these chromosomes look like under a light microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisi ...

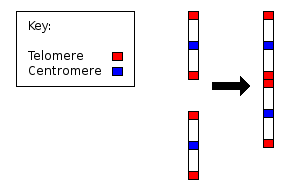

. Attention is paid to their length, the position of the centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers ...

s, banding pattern, any differences between the sex chromosome

A sex chromosome (also referred to as an allosome, heterotypical chromosome, gonosome, heterochromosome, or idiochromosome) is a chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in form, size, and behavior. The human sex chromosomes, a typical ...

s, and any other physical characteristics. The preparation and study of karyotypes is part of cytogenetics

Cytogenetics is essentially a branch of genetics, but is also a part of cell biology/cytology (a subdivision of human anatomy), that is concerned with how the chromosomes relate to cell behaviour, particularly to their behaviour during mitosis an ...

.

The basic number of chromosomes in the somatic cells of an individual or a species is called the ''somatic number'' and is designated ''2n''. In the germ-line

In biology and genetics, the germline is the population of a multicellular organism's cells that pass on their genetic material to the progeny (offspring). In other words, they are the cells that form the egg, sperm and the fertilised egg. Th ...

(the sex cells) the chromosome number is ''n'' (humans: n = 23).p28 Thus, in humans 2n = 46.

So, in normal diploid organisms, autosomal

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosom ...

chromosomes are present in two copies. There may, or may not, be sex chromosomes

A sex chromosome (also referred to as an allosome, heterotypical chromosome, gonosome, heterochromosome, or idiochromosome) is a chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in form, size, and behavior. The human sex chromosomes, a typical ...

. Polyploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei ( eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contain ...

cells have multiple copies of chromosomes and haploid cells have single copies.

Karyotypes can be used for many purposes; such as to study chromosomal aberration

A chromosomal abnormality, chromosomal anomaly, chromosomal aberration, chromosomal mutation, or chromosomal disorder, is a missing, extra, or irregular portion of chromosomal DNA. These can occur in the form of numerical abnormalities, where ther ...

s, cellular

Cellular may refer to:

*Cellular automaton, a model in discrete mathematics

* Cell biology, the evaluation of cells work and more

* ''Cellular'' (film), a 2004 movie

*Cellular frequencies, assigned to networks operating in cellular RF bands

*Cell ...

function, taxonomic relationships, medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

and to gather information about past evolutionary

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

events ('' karyosystematics'').

Observations on karyotypes

Staining

The study of karyotypes is made possible by staining. Usually, a suitable dye, such asGiemsa

Giemsa stain (), named after German chemist and bacteriologist Gustav Giemsa, is a nucleic acid stain used in cytogenetics and for the histopathological diagnosis of malaria and other parasites.

Uses

It is specific for the phosphate groups of ...

, is applied after cells have been arrested during cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there ar ...

by a solution of colchicine

Colchicine is a medication used to treat gout and Behçet's disease. In gout, it is less preferred to NSAIDs or steroids. Other uses for colchicine include the management of pericarditis and familial Mediterranean fever. Colchicine is taken b ...

usually in metaphase

Metaphase ( and ) is a stage of mitosis in the eukaryotic cell cycle in which chromosomes are at their second-most condensed and coiled stage (they are at their most condensed in anaphase). These chromosomes, carrying genetic information, alig ...

or prometaphase

Prometaphase is the phase of mitosis following prophase and preceding metaphase, in eukaryote, eukaryotic Somatic (biology), somatic Cell (biology), cells. In prometaphase, the nuclear membrane breaks apart into numerous "membrane vesicles", ...

when most condensed. In order for the Giemsa

Giemsa stain (), named after German chemist and bacteriologist Gustav Giemsa, is a nucleic acid stain used in cytogenetics and for the histopathological diagnosis of malaria and other parasites.

Uses

It is specific for the phosphate groups of ...

stain to adhere correctly, all chromosomal proteins must be digested and removed. For humans, white blood cells

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and derived from mult ...

are used most frequently because they are easily induced to divide and grow in tissue culture

Tissue culture is the growth of tissues or cells in an artificial medium separate from the parent organism. This technique is also called micropropagation. This is typically facilitated via use of a liquid, semi-solid, or solid growth medium, su ...

.Gustashaw K.M. 1991. Chromosome stains. In ''The ACT Cytogenetics Laboratory Manual'' 2nd ed, ed. M.J. Barch. The Association of Cytogenetic Technologists, Raven Press, New York. Sometimes observations may be made on non-dividing (interphase

Interphase is the portion of the cell cycle that is not accompanied by visible changes under the microscope, and includes the G1, S and G2 phases. During interphase, the cell grows (G1), replicates its DNA (S) and prepares for mitosis (G2). A c ...

) cells. The sex of an unborn fetus

A fetus or foetus (; plural fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo. Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal dev ...

can be predicted by observation of interphase cells (see amniotic centesis and Barr body

A Barr body (named after discoverer Murray Barr) or X-chromatin is an inactive X chromosome in a cell with more than one X chromosome, rendered inactive in a process called lyonization, in species with XY sex-determination (including huma ...

).

Observations

Six different characteristics of karyotypes are usually observed and compared: # Differences in absolute sizes of chromosomes. Chromosomes can vary in absolute size by as much as twenty-fold between genera of the same family. For example, the legumes '' Lotus tenuis'' and ''Vicia faba

''Vicia faba'', commonly known as the broad bean, fava bean, or faba bean, is a species of vetch, a flowering plant in the pea and bean family Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated as a crop for human consumption, and also as a cover crop. Varieti ...

'' each have six pairs of chromosomes, yet ''V. faba'' chromosomes are many times larger. These differences probably reflect different amounts of DNA duplication.

# Differences in the position of centromeres

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers a ...

. These differences probably came about through translocations

In genetics, chromosome translocation is a phenomenon that results in unusual rearrangement of chromosomes. This includes balanced and unbalanced translocation, with two main types: reciprocal-, and Robertsonian translocation. Reciprocal translo ...

.

# Differences in relative size of chromosomes. These differences probably arose from segmental interchange of unequal lengths.

# Differences in basic number of chromosomes. These differences could have resulted from successive unequal translocations which removed all the essential genetic material from a chromosome, permitting its loss without penalty to the organism (the dislocation hypothesis) or through fusion. Humans have one pair fewer chromosomes than the great apes. Human chromosome 2 appears to have resulted from the fusion of two ancestral chromosomes, and many of the genes of those two original chromosomes have been translocated to other chromosomes.

# Differences in number and position of satellites. Satellites are small bodies attached to a chromosome by a thin thread.

# Differences in degree and distribution of heterochromatic

Heterochromia is a variation in coloration. The term is most often used to describe color differences of the iris, but can also be applied to color variation of hair or skin. Heterochromia is determined by the production, delivery, and concentra ...

regions. Heterochromatin stains darker than euchromatin

Euchromatin (also called "open chromatin") is a lightly packed form of chromatin ( DNA, RNA, and protein) that is enriched in genes, and is often (but not always) under active transcription. Euchromatin stands in contrast to heterochromatin, whi ...

. Heterochromatin is packed tighter. Heterochromatin consists mainly of genetically inactive and repetitive DNA sequences as well as containing a larger amount of Adenine

Adenine () ( symbol A or Ade) is a nucleobase (a purine derivative). It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its deri ...

-Thymine

Thymine () ( symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidi ...

pairs. Euchromatin is usually under active transcription and stains much lighter as it has less affinity for the giemsa

Giemsa stain (), named after German chemist and bacteriologist Gustav Giemsa, is a nucleic acid stain used in cytogenetics and for the histopathological diagnosis of malaria and other parasites.

Uses

It is specific for the phosphate groups of ...

stain.Thompson & Thompson Genetics in Medicine 7th Ed Euchromatin regions contain larger amounts of Guanine

Guanine () ( symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is c ...

-Cytosine

Cytosine () ( symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached (an ...

pairs. The staining technique using giemsa

Giemsa stain (), named after German chemist and bacteriologist Gustav Giemsa, is a nucleic acid stain used in cytogenetics and for the histopathological diagnosis of malaria and other parasites.

Uses

It is specific for the phosphate groups of ...

staining is called G banding

G-banding, G banding or Giemsa banding is a technique used in cytogenetics to produce a visible karyotype by staining condensed chromosomes. It is the most common chromosome banding method. It is useful for identifying genetic diseases through t ...

and therefore produces the typical "G-Bands".

A full account of a karyotype may therefore include the number, type, shape and banding of the chromosomes, as well as other cytogenetic information.

Variation is often found:

# between the sexes,

# between the germ-line

In biology and genetics, the germline is the population of a multicellular organism's cells that pass on their genetic material to the progeny (offspring). In other words, they are the cells that form the egg, sperm and the fertilised egg. Th ...

and soma

Soma may refer to:

Businesses and brands

* SOMA (architects), a New York–based firm of architects

* Soma (company), a company that designs eco-friendly water filtration systems

* SOMA Fabrications, a builder of bicycle frames and other bicycle ...

(between gametes

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

and the rest of the body),

# between members of a population ( chromosome polymorphism),

# in geographic specialization, and

# in mosaics or otherwise abnormal individuals.

Human karyogram

Both the micrographic and schematic karyograms shown in this section have a standard chromosome layout, and display dark and white regions as seen on

Both the micrographic and schematic karyograms shown in this section have a standard chromosome layout, and display dark and white regions as seen on G banding

G-banding, G banding or Giemsa banding is a technique used in cytogenetics to produce a visible karyotype by staining condensed chromosomes. It is the most common chromosome banding method. It is useful for identifying genetic diseases through t ...

, which is the appearance of the chromosomes after treatment with trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the d ...

(to partially digest the chromosomes) and staining with Giemsa stain

Giemsa stain (), named after German chemist and bacteriologist Gustav Giemsa, is a nucleic acid stain used in cytogenetics and for the histopathological diagnosis of malaria and other parasites.

Uses

It is specific for the phosphate groups of ...

. They show the normal human diploid karyotype, which is the typical composition of the genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding g ...

within a normal cell of the human body, and which contains 22 pairs of autosomal

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosom ...

chromosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes

A sex chromosome (also referred to as an allosome, heterotypical chromosome, gonosome, heterochromosome, or idiochromosome) is a chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in form, size, and behavior. The human sex chromosomes, a typical ...

(allosomes). A major exception to diploidy in humans is gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

s (sperm and egg cells) which are monoploid with 23 unpaired chromosomes, and this ploidy is not shown in these karyograms.

The schematic karyogram in this section is a graphical representation of the idealized karyotype. For each chromosome pair, the scale to the left shows the length in terms of million base pairs, and the scale to the right shows the designations of the bands and sub-bands. Such bands and sub-bands are used by the International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature The International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature (previously International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature), ISCN in short, is an international standard for human chromosome nomenclature, which includes band names, symbols and a ...

to describe locations of chromosome abnormalities

A chromosomal abnormality, chromosomal anomaly, chromosomal aberration, chromosomal mutation, or chromosomal disorder, is a missing, extra, or irregular portion of chromosomal DNA. These can occur in the form of numerical abnormalities, where ther ...

. Each row of chromosomes is vertically aligned at centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers ...

level.

Human chromosome groups

Based on the karyogram characteristics of size, position of thecentromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers ...

and sometimes the presence of a chromosomal satellite (a segment distal to a secondary constriction), the human chromosomes are classified into the following groups:

Alternatively, the human genome can be classified as follows, based on pairing, sex differences, as well as location within the cell nucleus versus inside mitochondria:

*22 homologous autosomal

An autosome is any chromosome that is not a sex chromosome. The members of an autosome pair in a diploid cell have the same morphology, unlike those in allosomal (sex chromosome) pairs, which may have different structures. The DNA in autosom ...

chromosome pairs (chromosomes 1 to 22). Homologous means that they have the same genes in the same loci, and autosomal means that they are not sex chromomes.

*Two sex chromosome

A sex chromosome (also referred to as an allosome, heterotypical chromosome, gonosome, heterochromosome, or idiochromosome) is a chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in form, size, and behavior. The human sex chromosomes, a typical ...

(in green rectangle at bottom right in the schematic karyogram, with adjacent silhouettes of typical representative phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological pr ...

s): The most common karyotypes for females

Female (symbol: ♀) is the sex of an organism that produces the large non-motile ova (egg cells), the type of gamete (sex cell) that fuses with the male gamete during sexual reproduction.

A female has larger gametes than a male. Females ...

contain two X chromosome

The X chromosome is one of the two sex-determining chromosomes (allosomes) in many organisms, including mammals (the other is the Y chromosome), and is found in both males and females. It is a part of the XY sex-determination system and XO sex ...

s and are denoted 46,XX; males

Male (symbol: ♂) is the sex of an organism that produces the gamete (sex cell) known as sperm, which fuses with the larger female gamete, or ovum, in the process of fertilization.

A male organism cannot reproduce sexually without access to ...

usually have both an X and a Y chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes (allosomes) in therian mammals, including humans, and many other animals. The other is the X chromosome. Y is normally the sex-determining chromosome in many species, since it is the presence or abse ...

denoted 46,XY. However, approximately 0.018% percent of humans are intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical bin ...

, sometimes due to variations in sex chromosomes.

*The human mitochondrial genome (shown at bottom left in the schematic karyogram, to scale compared to the nuclear DNA), although this is not included in micrographic karyograms in clinical practice. Its genome is relatively tiny compared to the rest.

Copy number

cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and sub ...

) which is the most common state of cells. The schematic karyogram in this section also shows this state. In this state (as well as during the G1 phase of the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and sub ...

), each cell has 2 autosomal chromosomes of each kind (designated 2n), where each chromosome has one copy of each locus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Entertainment

* Locus (comics), a Marvel Comics mutant villainess, a member of the Mutant Liberation Front

* ''Locus'' (magazine), science fiction and fantasy magazine

** ''Locus Award' ...

, making a total copy number of 2 for each locus (2c). At top center in the schematic karyogram, it also shows the chromosome 3 pair after having undergone DNA synthesis

DNA synthesis is the natural or artificial creation of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules. DNA is a macromolecule made up of nucleotide units, which are linked by covalent bonds and hydrogen bonds, in a repeating structure. DNA synthesis occurs ...

, occurring in the S phase (annotated as S) of the cell cycle. This interval includes the G2 phase and metaphase

Metaphase ( and ) is a stage of mitosis in the eukaryotic cell cycle in which chromosomes are at their second-most condensed and coiled stage (they are at their most condensed in anaphase). These chromosomes, carrying genetic information, alig ...

(annotated as "Meta."). During this interval, there is still 2n, but each chromosome will have 2 copies of each locus, wherein each sister chromatid

A sister chromatid refers to the identical copies (chromatids) formed by the DNA replication of a chromosome, with both copies joined together by a common centromere. In other words, a sister chromatid may also be said to be 'one-half' of the dup ...

(chromosome arm) is connected at the centromere, for a total of 4c. The chromosomes on micrographic karyograms are in this state as well, because they are generally micrographed in metaphase, but during this phase the two copies of each chromosome are so close to each other that they appear as one unless the image resolution is high enough to distinguish them. In reality, during the G0 and G1 phases, nuclear DNA is dispersed as chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important roles in r ...

and does not show visually distinguishable chromosomes even on micrography.

The copy number of the human mitochondrial genome per human cell varies from 0 (erythrocytes) up to 1,500,000 (oocytes

An oocyte (, ), oöcyte, or ovocyte is a female gametocyte or germ cell involved in reproduction. In other words, it is an immature ovum, or egg cell. An oocyte is produced in a female fetus in the ovary during female gametogenesis. The female g ...

), mainly depending on the number of mitochondria per cell.

Diversity and evolution of karyotypes

Although the replication andtranscription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

of DNA is highly standardized in eukaryotes, the same cannot be said for their karyotypes, which are highly variable. There is variation between species in chromosome number, and in detailed organization, despite their construction from the same macromolecules

A macromolecule is a very large molecule important to biophysical processes, such as a protein or nucleic acid. It is composed of thousands of covalently bonded atoms. Many macromolecules are polymers of smaller molecules called monomers. The ...

. This variation provides the basis for a range of studies in evolutionary cytology

Cell biology (also cellular biology or cytology) is a branch of biology that studies the structure, function, and behavior of cells. All living organisms are made of cells. A cell is the basic unit of life that is responsible for the living an ...

.

In some cases there is even significant variation within species. In a review, Godfrey and Masters conclude:

Although much is known about karyotypes at the descriptive level, and it is clear that changes in karyotype organization has had effects on the evolutionary course of many species, it is quite unclear what the general significance might be.

Changes during development

Instead of the usual gene repression, some organisms go in for large-scale elimination of heterochromatin, or other kinds of visible adjustment to the karyotype. * Chromosome elimination. In some species, as in many sciarid flies, entire chromosomes are eliminated during development. * Chromatin diminution (founding father:Theodor Boveri

Theodor Heinrich Boveri (12 October 1862 – 15 October 1915) was a German zoologist, comparative anatomist and co-founder of modern cytology. He was notable for the first hypothesis regarding cellular processes that cause cancer, and for descr ...

). In this process, found in some copepods and roundworms

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a broa ...

such as ''Ascaris suum

''Ascaris suum'', also known as the large roundworm of pig, is a parasitic nematode that causes ascariasis in pigs. While roundworms in pigs and humans are today considered as two species (''A. suum'' and '' A. lumbricoides'') with different hos ...

'', portions of the chromosomes are cast away in particular cells. This process is a carefully organised genome rearrangement where new telomeres are constructed and certain heterochromatin regions are lost. In ''A. suum'', all the somatic cell precursors undergo chromatin diminution.

* X-inactivation

X-inactivation (also called Lyonization, after English geneticist Mary Lyon) is a process by which one of the copies of the X chromosome is inactivated in therian female mammals. The inactive X chromosome is silenced by being packaged into a ...

. The inactivation of one X chromosome takes place during the early development of mammals (see Barr body

A Barr body (named after discoverer Murray Barr) or X-chromatin is an inactive X chromosome in a cell with more than one X chromosome, rendered inactive in a process called lyonization, in species with XY sex-determination (including huma ...

and dosage compensation Dosage compensation is the process by which organisms equalize the expression of genes between members of different biological sexes. Across species, different sexes are often characterized by different types and numbers of sex chromosomes. In order ...

). In placental mammals

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

, the inactivation is random as between the two Xs; thus the mammalian female is a mosaic in respect of her X chromosomes. In marsupials it is always the paternal X which is inactivated. In human females some 15% of somatic cells escape inactivation, and the number of genes affected on the inactivated X chromosome varies between cells: in fibroblast cells up about 25% of genes on the Barr body escape inactivation.

Number of chromosomes in a set

A spectacular example of variability between closely related species is themuntjac

Muntjacs ( ), also known as the barking deer or rib-faced deer, (URL is Google Books) are small deer of the genus ''Muntiacus'' native to South Asia and Southeast Asia. Muntjacs are thought to have begun appearing 15–35 million years ago, ...

, which was investigated by Kurt Benirschke and Doris Wurster

Doris may refer to:

People Given name

*Doris (mythology) of Greek mythology, daughter of Oceanus and Tethys

* Doris, fictional character in the Canadian television series ''Caillou'' and the mother of the titular character

*Doris (singer) (born ...

. The diploid number of the Chinese muntjac, '' Muntiacus reevesi'', was found to be 46, all telocentric

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers ...

. When they looked at the karyotype of the closely related Indian muntjac, ''Muntiacus muntjak

The Indian muntjac or the common muntjac (''Muntiacus muntjak''), also called the southern red muntjac and barking deer, is a deer species native to South and Southeast Asia. It is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List. In popular local ...

'', they were astonished to find it had female = 6, male = 7 chromosomes.

The number of chromosomes in the karyotype between (relatively) unrelated species is hugely variable. The low record is held by the nematode '' Parascaris univalens'', where the haploid n = 1; and an ant: ''Myrmecia pilosula

Myrmecia can refer to:

* ''Myrmecia'' (alga), genus of algae associated with lichens

* ''Myrmecia'' (ant), genus of ants called bulldog ants

* Myrmecia (skin), a kind of deep wart on the human hands or feet

See also

* '' Copromorpha myrmecias'' ...

''. The high record would be somewhere amongst the fern

A fern (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta ) is a member of a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. The polypodiophytes include all living pteridophytes exce ...

s, with the adder's tongue fern ''Ophioglossum

''Ophioglossum'', the adder's-tongue ferns, is a genus of about 50 species of ferns in the family Ophioglossaceae. The name ''Ophioglossum'' comes from the Greek meaning "snake-tongue".

'' ahead with an average of 1262 chromosomes. Top score for animals might be the shortnose sturgeon

The shortnose sturgeon (''Acipenser brevirostrum'') is a small and endangered species of North American sturgeon. The earliest remains of the species are from the Late Cretaceous Period, over 70 million years ago.National Oceanic and Atmospheri ...

'' Acipenser brevirostrum'' at 372 chromosomes. The existence of supernumerary or B chromosomes means that chromosome number can vary even within one interbreeding population; and aneuploid

Aneuploidy is the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell, for example a human cell having 45 or 47 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. It does not include a difference of one or more complete sets of chromosomes. A cell with any ...

s are another example, though in this case they would not be regarded as normal members of the population.

Fundamental number

The fundamental number, ''FN'', of a karyotype is the number of visible major chromosomal arms per set of chromosomes. Thus, FN ≤ 2 x 2n, the difference depending on the number of chromosomes considered single-armed (acrocentric

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers ...

or telocentric

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers ...

) present. Humans have FN = 82, due to the presence of five acrocentric chromosome pairs: 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22 (the human Y chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes (allosomes) in therian mammals, including humans, and many other animals. The other is the X chromosome. Y is normally the sex-determining chromosome in many species, since it is the presence or abse ...

is also acrocentric). The fundamental autosomal number or autosomal fundamental number, ''FNa'' or ''AN'', of a karyotype is the number of visible major chromosomal arms per set of autosomes (non- sex-linked chromosomes).

Ploidy

Ploidy is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell. *Polyploidy

Polyploidy is a condition in which the biological cell, cells of an organism have more than one pair of (Homologous chromosome, homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have Cell nucleus, nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they ha ...

, where there are more than two sets of homologous chromosomes in the cells, occurs mainly in plants. It has been of major significance in plant evolution according to Stebbins. The proportion of flowering plants which are polyploid was estimated by Stebbins to be 30–35%, but in grasses the average is much higher, about 70%. Polyploidy in lower plants (fern

A fern (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta ) is a member of a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. The polypodiophytes include all living pteridophytes exce ...

s, horsetails

''Equisetum'' (; horsetail, snake grass, puzzlegrass) is the only living genus in Equisetaceae, a family of ferns, which reproduce by spores rather than seeds.

''Equisetum'' is a " living fossil", the only living genus of the entire subclass ...

and psilotales

Psilotaceae is a family of ferns (class Polypodiopsida) consisting of two genera, '' Psilotum'' and ''Tmesipteris'' with about a dozen species. It is the only family in the order Psilotales.

Description

Once thought to be descendants of early va ...

) is also common, and some species of ferns have reached levels of polyploidy far in excess of the highest levels known in flowering plants. Polyploidy in animals is much less common, but it has been significant in some groups.

Polyploid series in related species which consist entirely of multiples of a single basic number are known as euploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

.

* Haplo-diploidy, where one sex is diploid, and the other haploid. It is a common arrangement in the Hymenoptera, and in some other groups.

* Endopolyploidy

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contains ...

occurs when in adult differentiated tissues the cells have ceased to divide by mitosis, but the nuclei contain more than the original somatic number of chromosomes

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

. In the ''endocycle'' ( endomitosis or endoreduplication

Endoreduplication (also referred to as endoreplication or endocycling) is replication of the nuclear genome in the absence of mitosis, which leads to elevated nuclear gene content and polyploidy. Endoreplication can be understood simply as a vari ...

) chromosomes in a 'resting' nucleus undergo reduplication, the daughter chromosomes separating from each other inside an ''intact'' nuclear membrane

The nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane, is made up of two lipid bilayer membranes that in eukaryotic cells surround the nucleus, which encloses the genetic material.

The nuclear envelope consists of two lipid bilayer membra ...

. In many instances, endopolyploid nuclei contain tens of thousands of chromosomes (which cannot be exactly counted). The cells do not always contain exact multiples (powers of two), which is why the simple definition 'an increase in the number of chromosome sets caused by replication without cell division' is not quite accurate.

This process (especially studied in insects and some higher plants such as maize) may be a developmental strategy for increasing the productivity of tissues which are highly active in biosynthesis.

The phenomenon occurs sporadically throughout the eukaryote kingdom from protozoa to humans; it is diverse and complex, and serves differentiation and

morphogenesis

Morphogenesis (from the Greek ''morphê'' shape and ''genesis'' creation, literally "the generation of form") is the biological process that causes a cell, tissue or organism to develop its shape. It is one of three fundamental aspects of deve ...

in many ways.

* See palaeopolyploidy for the investigation of ancient karyotype duplications.

Aneuploidy

Aneuploidy

Aneuploidy is the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell, for example a human cell having 45 or 47 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. It does not include a difference of one or more complete sets of chromosomes. A cell with any ...

is the condition in which the chromosome number in the cells is not the typical number for the species. This would give rise to a chromosome abnormality

A chromosomal abnormality, chromosomal anomaly, chromosomal aberration, chromosomal mutation, or chromosomal disorder, is a missing, extra, or irregular portion of Chromosome, chromosomal DNA. These can occur in the form of numerical abnormalities ...

such as an extra chromosome or one or more chromosomes lost. Abnormalities in chromosome number usually cause a defect in development. Down syndrome

Down syndrome or Down's syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21. It is usually associated with physical growth delays, mild to moderate intellectual dis ...

and Turner syndrome

Turner syndrome (TS), also known as 45,X, or 45,X0, is a genetic condition in which a female is partially or completely missing an X chromosome. Signs and symptoms vary among those affected. Often, a short and webbed neck, low-set ears, low hair ...

are examples of this.

Aneuploidy may also occur within a group of closely related species. Classic examples in plants are the genus ''Crepis

''Crepis'', commonly known in some parts of the world as hawksbeard or hawk's-beard (but not to be confused with the related genus ''Hieracium'' with a similar common name), is a genus of annual and perennial flowering plants of the family Aster ...

'', where the gametic (= haploid) numbers form the series x = 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7; and ''Crocus

''Crocus'' (; plural: crocuses or croci) is a genus of seasonal flowering plants in the family Iridaceae (iris family) comprising about 100 species of perennials growing from corms. They are low growing plants, whose flower stems remain under ...

'', where every number from x = 3 to x = 15 is represented by at least one species. Evidence of various kinds shows that trends of evolution have gone in different directions in different groups. In primates, the great apes

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

have 24x2 chromosomes whereas humans have 23x2. Human chromosome 2 was formed by a merger of ancestral chromosomes, reducing the number.

Chromosomal polymorphism

Some species are polymorphic for different chromosome structural forms. The structural variation may be associated with different numbers of chromosomes in different individuals, which occurs in the ladybird beetle '' Chilocorus stigma'', somemantids

Mantidae is one of the largest families in the order of praying mantises, based on the type species '' Mantis religiosa''; however, most genera are tropical or subtropical. Historically, this was the only family in the order, and many referen ...

of the genus ''Ameles

''Ameles'' is a wide-ranging genus of praying mantises represented in Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Tree of Life Web Project. 2005

'', the European shrew ''Tree of Life Web Project. 2005

Sorex araneus

The common shrew (''Sorex araneus''), also known as the Eurasian shrew, is the most common shrew, and one of the most common mammals, throughout Northern Europe, including Great Britain, but excluding Ireland. It is long and weighs , and has ve ...

''. There is some evidence from the case of the mollusc '' Thais lapillus'' (the dog whelk

The dog whelk, dogwhelk, or Atlantic dogwinkle (''Nucella lapillus'') is a species of predatory sea snail, a carnivorous marine gastropod in the family Muricidae, the rock snails.

''Nucella lapillus'' was originally described by Carl Linnaeus i ...

) on the Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

coast, that the two chromosome morphs are adapted

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the po ...

to different habitats.

Species trees

The detailed study of chromosome banding in insects withpolytene chromosome

Polytene chromosomes are large chromosomes which have thousands of DNA strands. They provide a high level of function in certain tissues such as salivary glands of insects.

Polytene chromosomes were first reported by E.G.Balbiani in 1881. P ...

s can reveal relationships between closely related species: the classic example is the study of chromosome banding in Hawaiian drosophilids by Hampton L. Carson.

In about , the Hawaiian Islands have the most diverse collection of drosophilid flies in the world, living from rainforests

Rainforests are characterized by a closed and continuous tree canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforest can be classified as tropical rainforest or temperate rainforest ...

to subalpine meadows. These roughly 800 Hawaiian drosophilid species are usually assigned to two genera, ''Drosophila

''Drosophila'' () is a genus of flies, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or (less frequently) pomace flies, vinegar flies, or wine flies, a reference to the characteristic of many speci ...

'' and '' Scaptomyza'', in the family Drosophilidae

The Drosophilidae are a diverse, cosmopolitan family of flies, which includes species called fruit flies, although they are more accurately referred to as vinegar or pomace flies. Another distantly related family of flies, Tephritidae, are true ...

.

The polytene banding of the 'picture wing' group, the best-studied group of Hawaiian drosophilids, enabled Carson to work out the evolutionary tree long before genome analysis was practicable. In a sense, gene arrangements are visible in the banding patterns of each chromosome. Chromosome rearrangements, especially inversions, make it possible to see which species are closely related.

The results are clear. The inversions, when plotted in tree form (and independent of all other information), show a clear "flow" of species from older to newer islands. There are also cases of colonization back to older islands, and skipping of islands, but these are much less frequent. Using K-Ar dating, the present islands date from 0.4 million years ago (mya) ( Mauna Kea) to 10mya ( Necker). The oldest member of the Hawaiian archipelago still above the sea is Kure Atoll

Kure Atoll (; haw, Hōlanikū, translation=bringing forth heaven; haw, Mokupāpapa, translation=flat island, label=none) or Ocean Island is an atoll in the Pacific Ocean west-northwest of Midway Atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands ...

, which can be dated to 30 mya. The archipelago itself (produced by the Pacific plate moving over a hot spot) has existed for far longer, at least into the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

. Previous islands now beneath the sea (guyot

In marine geology, a guyot (pronounced ), also known as a tablemount, is an isolated underwater volcanic mountain (seamount) with a flat top more than below the surface of the sea. The diameters of these flat summits can exceed .Emperor Seamount Chain

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother (empr ...

.

All of the native ''Drosophila'' and ''Scaptomyza'' species in Hawaii have apparently descended from a single ancestral species that colonized the islands, probably 20 million years ago. The subsequent adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

was spurred by a lack of competition

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indiv ...

and a wide variety of niches. Although it would be possible for a single gravid

In biology and human medicine, gravidity and parity are the number of times a woman is or has been pregnant (gravidity) and carried the pregnancies to a viable gestational age (parity). These terms are usually coupled, sometimes with additional t ...

female to colonise an island, it is more likely to have been a group from the same species.

There are other animals and plants on the Hawaiian archipelago which have undergone similar, if less spectacular, adaptive radiations.

Chromosome banding

Chromosomes display a banded pattern when treated with some stains. Bands are alternating light and dark stripes that appear along the lengths of chromosomes. Unique banding patterns are used to identify chromosomes and to diagnose chromosomal aberrations, including chromosome breakage, loss, duplication, translocation or inverted segments. A range of different chromosome treatments produce a range of banding patterns: G-bands, R-bands, C-bands, Q-bands, T-bands and NOR-bands.Depiction of karyotypes

Types of banding

Cytogenetics

Cytogenetics is essentially a branch of genetics, but is also a part of cell biology/cytology (a subdivision of human anatomy), that is concerned with how the chromosomes relate to cell behaviour, particularly to their behaviour during mitosis an ...

employs several techniques to visualize different aspects of chromosomes:

* G-banding

G-banding, G banding or Giemsa banding is a technique used in cytogenetics to produce a visible karyotype by staining condensed chromosomes. It is the most common chromosome banding method. It is useful for identifying genetic diseases through the ...

is obtained with Giemsa stain

Giemsa stain (), named after German chemist and bacteriologist Gustav Giemsa, is a nucleic acid stain used in cytogenetics and for the histopathological diagnosis of malaria and other parasites.

Uses

It is specific for the phosphate groups of ...

following digestion of chromosomes with trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the d ...

. It yields a series of lightly and darkly stained bands — the dark regions tend to be heterochromatic, late-replicating and AT rich. The light regions tend to be euchromatic, early-replicating and GC rich. This method will normally produce 300–400 bands in a normal, human genome

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as DNA within the 23 chromosome pairs in cell nuclei and in a small DNA molecule found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the ...

. It is the most common chromosome banding method.

* R-banding is the reverse of G-banding (the R stands for "reverse"). The dark regions are euchromatic (guanine-cytosine rich regions) and the bright regions are heterochromatic (thymine-adenine rich regions).

* C-banding: Giemsa binds to constitutive heterochromatin

Constitutive heterochromatin domains are regions of DNA found throughout the chromosomes of eukaryotes. The majority of constitutive heterochromatin is found at the pericentromeric regions of chromosomes, but is also found at the telomeres and thro ...

, so it stains centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fibers ...

s. The name is derived from centromeric or constitutive heterochromatin. The preparations undergo alkaline denaturation prior to staining leading to an almost complete depurination of the DNA. After washing the probe the remaining DNA is renatured again and stained with Giemsa solution consisting of methylene azure, methylene violet, methylene blue, and eosin. Heterochromatin binds a lot of the dye, while the rest of the chromosomes absorb only little of it. The C-bonding proved to be especially well-suited for the characterization of plant chromosomes.

* Q-banding is a fluorescent

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, ...

pattern obtained using quinacrine

Mepacrine, also called quinacrine or by the trade name Atabrine, is a medication with several uses. It is related to chloroquine and mefloquine. Although formerly available from compounding pharmacies, as of August 2020 it is unavailable in th ...

for staining. The pattern of bands is very similar to that seen in G-banding. They can be recognized by a yellow fluorescence of differing intensity. Most part of the stained DNA is heterochromatin. Quinacrin (atebrin) binds both regions rich in AT and in GC, but only the AT-quinacrin-complex fluoresces. Since regions rich in AT are more common in heterochromatin than in euchromatin, these regions are labelled preferentially. The different intensities of the single bands mirror the different contents of AT. Other fluorochromes like DAPI or Hoechst 33258 lead also to characteristic, reproducible patterns. Each of them produces its specific pattern. In other words: the properties of the bonds and the specificity of the fluorochromes are not exclusively based on their affinity to regions rich in AT. Rather, the distribution of AT and the association of AT with other molecules like histones, for example, influences the binding properties of the fluorochromes.

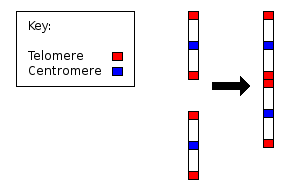

* T-banding: visualize telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes. Although there are different architectures, telomeres, in a broad sense, are a widespread genetic feature mos ...

s.

* Silver staining: Silver nitrate

Silver nitrate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula . It is a versatile precursor to many other silver compounds, such as those used in photography. It is far less sensitive to light than the halides. It was once called ''lunar causti ...

stains the nucleolar organization region-associated protein. This yields a dark region where the silver is deposited, denoting the activity of rRNA genes within the NOR.

Classic karyotype cytogenetics

In the "classic" (depicted) karyotype, a dye, often

In the "classic" (depicted) karyotype, a dye, often Giemsa

Giemsa stain (), named after German chemist and bacteriologist Gustav Giemsa, is a nucleic acid stain used in cytogenetics and for the histopathological diagnosis of malaria and other parasites.

Uses

It is specific for the phosphate groups of ...

''(G-banding)'', less frequently mepacrine (quinacrine), is used to stain bands on the chromosomes. Giemsa is specific for the phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phosph ...

groups of DNA. Quinacrine binds to the adenine

Adenine () ( symbol A or Ade) is a nucleobase (a purine derivative). It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its deri ...

-thymine

Thymine () ( symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidi ...

-rich regions. Each chromosome has a characteristic banding pattern that helps to identify them; both chromosomes in a pair will have the same banding pattern.

Karyotypes are arranged with the short arm of the chromosome on top, and the long arm on the bottom. Some karyotypes call the short and long arms ''p'' and ''q'', respectively. In addition, the differently stained regions and sub-regions are given numerical designations from proximal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

to distal on the chromosome arms. For example, Cri du chat

Cri du chat syndrome is a rare genetic disorder due to a partial chromosome deletion on chromosome 5. Its name is a French term ("cat-cry" or " call of the cat") referring to the characteristic cat-like cry of affected children. It was first de ...

syndrome involves a deletion on the short arm of chromosome 5. It is written as 46,XX,5p-. The critical region for this syndrome is deletion of p15.2 (the locus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Entertainment

* Locus (comics), a Marvel Comics mutant villainess, a member of the Mutant Liberation Front

* ''Locus'' (magazine), science fiction and fantasy magazine

** ''Locus Award' ...

on the chromosome), which is written as 46,XX,del(5)(p15.2).

Multicolor FISH (mFISH) and spectral karyotype (SKY technique)

Multicolor

Multicolor FISH

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% of ...

and the older spectral karyotyping are molecular cytogenetic

Cytogenetics is essentially a branch of genetics, but is also a part of cell biology/cytology (a subdivision of human anatomy), that is concerned with how the chromosomes relate to cell behaviour, particularly to their behaviour during mitosis an ...

techniques used to simultaneously visualize all the pairs of chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

s in an organism in different colors. Fluorescent

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, ...

ly labeled probes for each chromosome are made by labeling chromosome-specific DNA with different fluorophore

A fluorophore (or fluorochrome, similarly to a chromophore) is a fluorescent chemical compound that can re-emit light upon light excitation. Fluorophores typically contain several combined aromatic groups, or planar or cyclic molecules with se ...

s. Because there are a limited number of spectrally distinct fluorophores, a combinatorial labeling method is used to generate many different colors. Fluorophore combinations are captured and analyzed by a fluorescence microscope using up to 7 narrow-banded fluorescence filters or, in the case of spectral karyotyping, by using an interferometer attached to a fluorescence microscope. In the case of an mFISH image, every combination of fluorochromes from the resulting original images is replaced by a pseudo color in a dedicated image analysis software. Thus, chromosomes or chromosome sections can be visualized and identified, allowing for the analysis of chromosomal rearrangements.

In the case of spectral karyotyping, image processing software assigns a pseudo color to each spectrally different combination, allowing the visualization of the individually colored chromosomes.

Multicolor FISH is used to identify structural chromosome aberrations in cancer cells and other disease conditions when Giemsa banding or other techniques are not accurate enough.

Digital karyotyping

''Digital karyotyping'' is a technique used to quantify the DNA copy number on a genomic scale. Short sequences of DNA from specific loci all over the genome are isolated and enumerated. This method is also known as virtual karyotyping. Using this technique, it is possible to detect small alterations in the human genome, that cannot be detected through methods employing metaphase chromosomes. Some loci deletions are known to be related to the development of cancer. Such deletions are found through digital karyotyping using the loci associated with cancer development.Chromosome abnormalities

Chromosome abnormalities can be numerical, as in the presence of extra or missing chromosomes, or structural, as in derivative chromosome,translocations

In genetics, chromosome translocation is a phenomenon that results in unusual rearrangement of chromosomes. This includes balanced and unbalanced translocation, with two main types: reciprocal-, and Robertsonian translocation. Reciprocal translo ...

, inversions, large-scale deletions or duplications. Numerical abnormalities, also known as aneuploidy

Aneuploidy is the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell, for example a human cell having 45 or 47 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. It does not include a difference of one or more complete sets of chromosomes. A cell with any ...

, often occur as a result of nondisjunction

Nondisjunction is the failure of homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids to separate properly during cell division (mitosis/meiosis). There are three forms of nondisjunction: failure of a pair of homologous chromosomes to separate in meiosis ...

during meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately r ...

in the formation of a gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

; trisomies, in which three copies of a chromosome are present instead of the usual two, are common numerical abnormalities. Structural abnormalities often arise from errors in homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in cellular organisms but may ...

. Both types of abnormalities can occur in gametes and therefore will be present in all cells of an affected person's body, or they can occur during mitosis and give rise to a genetic mosaic individual who has some normal and some abnormal cells.

In humans

Chromosomal abnormalities that lead to disease in humans include *Turner syndrome

Turner syndrome (TS), also known as 45,X, or 45,X0, is a genetic condition in which a female is partially or completely missing an X chromosome. Signs and symptoms vary among those affected. Often, a short and webbed neck, low-set ears, low hair ...

results from a single X chromosome (45,X or 45,X0).

* Klinefelter syndrome

Klinefelter syndrome (KS), also known as 47,XXY, is an aneuploid genetic condition where a male has an additional copy of the X chromosome. The primary features are infertility and small, poorly functioning testicles. Usually, symptoms are sub ...

, the most common male chromosomal disease, otherwise known as 47,XXY, is caused by an extra X chromosome.

* Edwards syndrome

Edwards syndrome, also known as trisomy 18, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of a third copy of all or part of chromosome 18. Many parts of the body are affected. Babies are often born small and have heart defects. Other features inc ...

is caused by trisomy

A trisomy is a type of polysomy in which there are three instances of a particular chromosome, instead of the normal two. A trisomy is a type of aneuploidy (an abnormal number of chromosomes).

Description and causes

Most organisms that reprodu ...

(three copies) of chromosome 18.

* Down syndrome

Down syndrome or Down's syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21. It is usually associated with physical growth delays, mild to moderate intellectual dis ...

, a common chromosomal disease, is caused by trisomy of chromosome 21.

* Patau syndrome

Patau syndrome is a syndrome caused by a chromosomal abnormality, in which some or all of the cells of the body contain extra genetic material from chromosome 13. The extra genetic material disrupts normal development, causing multiple and comp ...

is caused by trisomy of chromosome 13.

* Trisomy 9

Full trisomy 9 is a lethal chromosomal disorder caused by having three copies (trisomy) of chromosome number 9. It can be a viable condition if trisomy affects only part of the cells of the body (mosaicism) or in cases of partial trisomy (triso ...

, believed to be the 4th most common trisomy, has many long lived affected individuals but only in a form other than a full trisomy, such as trisomy 9p syndrome or mosaic trisomy 9. They often function quite well, but tend to have trouble with speech.

* Also documented are trisomy 8 and trisomy 16, although they generally do not survive to birth.

Some disorders arise from loss of just a piece of one chromosome, including

* Cri du chat

Cri du chat syndrome is a rare genetic disorder due to a partial chromosome deletion on chromosome 5. Its name is a French term ("cat-cry" or " call of the cat") referring to the characteristic cat-like cry of affected children. It was first de ...

(cry of the cat), from a truncated short arm on chromosome 5. The name comes from the babies' distinctive cry, caused by abnormal formation of the larynx.

* 1p36 Deletion syndrome

1p36 deletion syndrome is a congenital genetic disorder characterized by moderate to severe intellectual disability, delayed growth, hypotonia, seizures, limited speech ability, malformations, hearing and vision impairment, and distinct facial ...

, from the loss of part of the short arm of chromosome 1.

* Angelman syndrome – 50% of cases have a segment of the long arm of chromosome 15 missing; a deletion of the maternal genes, example of imprinting disorder.

* Prader-Willi syndrome – 50% of cases have a segment of the long arm of chromosome 15 missing; a deletion of the paternal genes, example of imprinting disorder.

* Chromosomal abnormalities can also occur in cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

ous cells of an otherwise genetically normal individual; one well-documented example is the Philadelphia chromosome

The Philadelphia chromosome or Philadelphia translocation (Ph) is a specific genetic abnormality in chromosome 22 of leukemia cancer cells (particularly chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) cells). This chromosome is defective and unusually short becaus ...

, a translocation mutation commonly associated with chronic myelogenous leukemia and less often with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

History of karyotype studies

Chromosomes were first observed in plant cells byCarl Wilhelm von Nägeli Carl may refer to:

*Carl, Georgia, city in USA

*Carl, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

* Carl (name), includes info about the name, variations of the name, and a list of people with the name

*Carl², a TV series

* "Carl", an episode of te ...

in 1842. Their behavior in animal (salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

) cells was described by Walther Flemming

Walther Flemming (21 April 1843 – 4 August 1905) was a German biologist and a founder of cytogenetics.

He was born in Sachsenberg (now part of Schwerin) as the fifth child and only son of the psychiatrist Carl Friedrich Flemming (1799–18 ...

, the discoverer of mitosis, in 1882. The name was coined by another German anatomist, Heinrich von Waldeyer in 1888. It is New Latin

New Latin (also called Neo-Latin or Modern Latin) is the revival of Literary Latin used in original, scholarly, and scientific works since about 1500. Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy ...

from Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

κάρυον ''karyon'', "kernel", "seed", or "nucleus", and τύπος ''typos'', "general form")

The next stage took place after the development of genetics in the early 20th century, when it was appreciated that chromosomes (that can be observed by karyotype) were the carrier of genes. The term karyotype as defined by the phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

appearance of the somatic chromosomes, in contrast to their genic

''Genic'' (stylized as ''_genic'') is the twelfth and final studio album and final bilingual (English–Japanese) album by Japanese recording artist Namie Amuro. It was released on June 10, 2015 in three physical formats, and for digital consumpti ...

contents was introduced by Grigory Levitsky who worked with Lev Delaunay, Sergei Navashin

Sergei Gavrilovich Navashin (russian: Серге́й Гаврилович Навашин); (14 December 1857 – 10 December 1930) was a Russian and Soviet biologist. He discovered double fertilization in plants in 1898.

Biography

1874 — ...

, and Nikolai Vavilov

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov ( rus, Никола́й Ива́нович Вави́лов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ vɐˈvʲiləf, a=Ru-Nikolay_Ivanovich_Vavilov.ogg; – 26 January 1943) was a Russian and Soviet agronomist, botanist ...

. The subsequent history of the concept can be followed in the works of C. D. Darlington and Michael JD White.White M.J.D. 1973. ''Animal cytology and evolution''. 3rd ed, Cambridge University Press.

Investigation into the human karyotype took many years to settle the most basic question: how many chromosomes does a normal diploid human cell contain? In 1912, Hans von Winiwarter reported 47 chromosomes in spermatogonia

A spermatogonium (plural: ''spermatogonia'') is an undifferentiated male germ cell. Spermatogonia undergo spermatogenesis to form mature spermatozoa in the seminiferous tubules of the testis.

There are three subtypes of spermatogonia in humans:

...

and 48 in oogonia

An oogonium (plural oogonia) is a small diploid cell which, upon maturation, forms a primordial follicle in a female fetus or the female (haploid or diploid) gametangium of certain thallophytes.

In the mammalian fetus

Oogonia are formed in lar ...

, concluding an XX/XO sex determination mechanism. Painter in 1922 was not certain whether the diploid of humans was 46 or 48, at first favoring 46, but revised his opinion from 46 to 48, and he correctly insisted on humans having an XX/XY system. Considering the techniques of the time, these results were remarkable.

Joe Hin Tjio

Joe Hin Tjio (2 November 1919 – 27 November 2001), was an Indonesian-born American cytogeneticist. He was renowned as the first person to recognize the normal number of human chromosomes on December 22, 1955 at the Institute of Genetics of the ...

working in Albert Levan