Spartan Army on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Spartan army stood at the center of the

The Spartan army stood at the center of the

Like much of Greece, Mycenaean Sparta was engulfed in the Dorian invasions, which ended the Mycenaean civilization and ushered in the so-called "Greek Dark Ages." During this time,

Like much of Greece, Mycenaean Sparta was engulfed in the Dorian invasions, which ended the Mycenaean civilization and ushered in the so-called "Greek Dark Ages." During this time,

By the late 6th century BC, Sparta was recognized as the preeminent Greek ''

By the late 6th century BC, Sparta was recognized as the preeminent Greek ''

The two

The two

Like the other Greek city-states' armies, the Spartan army was an infantry-based army that fought using the phalanx formation. The Spartans themselves did not introduce any significant changes or tactical innovations in ''

Like the other Greek city-states' armies, the Spartan army was an infantry-based army that fought using the phalanx formation. The Spartans themselves did not introduce any significant changes or tactical innovations in ''

The Spartan ''

The Spartan ''

Throughout their history, the Spartans were a land-based force ''par excellence''. During

Throughout their history, the Spartans were a land-based force ''par excellence''. During

The Spartan army stood at the center of the

The Spartan army stood at the center of the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

n state, citizens

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

trained in the disciplines and honor of a warrior society.Connolly (2006), p. 38 Subjected to military drills since early manhood, the Spartans became one of the most feared and formidable military forces in the Greek world, attaining legendary status in their wars against Persia. At the height of Sparta's power – between the 6th and 4th centuries BC – other Greeks commonly accepted that "one Spartan was worth several men of any other state."

Tradition states that the semi-mythical Spartan legislator Lycurgus

Lycurgus or Lykourgos () may refer to:

People

* Lycurgus (king of Sparta) (third century BC)

* Lycurgus (lawgiver) (eighth century BC), creator of constitution of Sparta

* Lycurgus of Athens (fourth century BC), one of the 'ten notable orators' ...

first founded the iconic army. Referring to Sparta as having a "wall of men, instead of bricks," he proposed reforming the Spartan society to develop a military-focused lifestyle following "proper virtue

Virtue ( la, virtus) is morality, moral excellence. A virtue is a trait or quality that is deemed to be morally good and thus is Value (ethics), valued as a foundation of principle and good moral being. In other words, it is a behavior that sh ...

s" such as equality for the male citizens, austerity, strength, and fitness. Spartan boys deemed strong enough entered the ''agoge

The ( grc-gre, ἀγωγή in Attic Greek, or , in Doric Greek) was the rigorous education and training program mandated for all male Spartan citizens, with the exception of the firstborn son in the ruling houses, Eurypontid and Agiad. The ...

'' regime at the age of seven, undergoing intense and rigorous military training. Their education focused primarily on fostering cunningness, practicing sports

Sport pertains to any form of competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to spectators. Sports can, ...

and war tactics, and also included learning about poetry, music, academics, and sometimes politics. Those who passed the ''agoge'' by the age of 30 achieved full Spartan citizenship.

The term "Spartan" became in modern times synonymous with simplicity by design. During classical times, "Lacedaemonian" or "Laconian" was used for attribution, referring to the region of the ''polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

'' instead of one of the decentralized settlements called Sparta. From this derives the already ancient term " laconic," and is related to expressions such as " laconic phrase" or " laconophilia."

History

Mycenaean age

The first reference to the Spartans at war is in the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

'', in which they featured among the other Greek contingents. Like the rest of the Mycenaean-era armies, it was depicted as composed mainly of infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

, equipped with short swords, spears, and Dipylon-type shields ("8"-shaped simple round bronze shields). This period was the Golden Age of Warfare.

In a battle, each opposing army would try to fight through the other line on the right (strong or deep) side and then turn left; wherefore they would be able to attack the vulnerable flank. When this happened, as a rule, it would cause the army to be routed. The fleeing enemy was put to the sword only as far as the field of the battle extended. The outcome of this one battle would determine the outcome of a particular issue. In the Golden Age of War, defeated armies were not massacred; they fled back to their city and conceded the victors' superiority. It wasn't until after the Peloponnesus

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge wh ...

War that battles countenanced indiscriminate slaughter, enslavement and depredations among the Greeks.

War chariots were used by the elite, but unlike their counterparts in the Middle East, they appear to have been used for transport, with the warrior dismounting to fight on foot and then remounting to withdraw from combat. However, some accounts show warriors throwing their spear from the chariot before dismounting.

Archaic Age and expansion

Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

(or Lacedaemon) was merely a Doric village on the banks of the River Eurotas

In Greek mythology, Eurotas (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρώτας) was a king of Laconia. Family

Eurotas was the son of King Myles of Laconia and grandson of Lelex, eponymous ancestor of the Leleges. The '' Bibliotheca'' gave a slight variant of ...

in Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia ( el, Λακωνία, , ) is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word '' laconic''—to speak in a blunt, c ...

. However, in the early 8th century BC, Spartan society transformed. Later traditions ascribed the reforms to the possibly mythical figure of Lycurgus

Lycurgus or Lykourgos () may refer to:

People

* Lycurgus (king of Sparta) (third century BC)

* Lycurgus (lawgiver) (eighth century BC), creator of constitution of Sparta

* Lycurgus of Athens (fourth century BC), one of the 'ten notable orators' ...

, who created new institutions and established the Spartan state's military nature.Sekunda (1998), p. 4. This Spartan Constitution

The Spartan Constitution (or Spartan politeia) are the government and laws of the classical Greek city-state of Sparta. All classical Greek city-states had a politeia; the politeia of Sparta however, was noted by many classical authors for its ...

remained virtually unchanged for five centuries. From c. 750 BC, Sparta embarked on a steady expansion, first by subduing Amyclae

Amyclae or Amyklai ( grc, Ἀμύκλαι) was a city of ancient Laconia, situated on the right or western bank of the Eurotas, 20 stadia south of Sparta, in a district remarkable for the abundance of its trees and its fertility. Amyclae was one ...

and the other Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia ( el, Λακωνία, , ) is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word '' laconic''—to speak in a blunt, c ...

n settlements. Later, during the First Messenian War, they conquered the fertile country of Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; el, Μεσσηνία ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a ...

. By the beginning of the 7th century BC, Sparta was, along with Argos, the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

's dominant power.

Establishment of Spartan hegemony over the Peloponnese

Inevitably, Sparta and Argos collided. Initial Argive successes, such as the victory at the Battle of Hysiae in 669 BC, led to the Messenians' uprising. This internal conflict tied down the Spartan army for almost 20 years. However, over the course of the 6th century, Sparta secured her control of thePeloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

peninsula. The Spartans forced Arcadia into recognizing their power; Argos lost Cynuria (the SE coast of the Peloponnese) in about 546 and suffered a further crippling blow from Cleomenes I at the Battle of Sepeia

At the Battle of Sepeia ( grc, Σήπεια) (c. 494 BC), the Spartan forces of Cleomenes I defeated the Argives, fully establishing Spartan dominance in the Peloponnese. The Battle of Sepeia is infamous for holding the highest number of casualt ...

in 494. Repeated expeditions against tyrannical

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to r ...

regimes during this period throughout Greece also considerably raised the Spartans' prestige.Sekunda (1998), p. 7. By the early 5th century, Sparta was the unchallenged master in southern Greece, as the leading power (''hegemon

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

'') of the newly established Peloponnesian League

The Peloponnesian League was an alliance of ancient Greek city-states, dominated by Sparta and centred on the Peloponnese, which lasted from c.550 to 366 BC. It is known mainly for being one of the two rivals in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 ...

(which was more characteristically known to its contemporaries as "the Lacedaemonians and their allies").Connolly (2006), p. 11.

Persian and Peloponnesian Wars

By the late 6th century BC, Sparta was recognized as the preeminent Greek ''

By the late 6th century BC, Sparta was recognized as the preeminent Greek ''polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

.'' King Croesus of Lydia established an alliance with the Spartans, and later, the Greek cities of Asia Minor appealed to them for help during the Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisf ...

. During the second Persian invasion Persian invasion may refer to:

* Persian invasion of Scythia, 513 BC

* Greco-Persian Wars

** First Persian invasion of Greece, 492–490 BC

** Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred duri ...

of Greece, under Xerxes, Sparta was assigned the overall leadership of Greek forces on both land and sea. The Spartans played a crucial role in the repulsion of the invasion, notably at the battles of Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

and Plataea

Plataea or Plataia (; grc, Πλάταια), also Plataeae or Plataiai (; grc, Πλαταιαί), was an ancient city, located in Greece in southeastern Boeotia, south of Thebes.Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Plataea.” '' Webst ...

. However, during the aftermath, because of the plotting of Pausanias with the Persians and their unwillingness to campaign too far from home, the Spartans withdrew into relative isolation. The power vacuum resulted in Athens' rise to power, who became the lead in the continued effort against the Persians. This isolationist tendency was further reinforced by some of her allies' revolts and a great earthquake in 464, which was followed by a large scale revolt of the Messenian helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ...

.

Athens's parallel rise as a significant power in Greece led to friction between herself with Sparta and two large-scale conflicts (the First and Second Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

s), which devastated Greece. Sparta suffered several defeats during these wars, including, for the first time, the surrender of an entire Spartan unit at Sphacteria in 425 BC. Still, it ultimately emerged victorious, primarily through the aid it received from the Persians. Under its admiral Lysander

Lysander (; grc-gre, Λύσανδρος ; died 395 BC) was a Spartan military and political leader. He destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, forcing Athens to capitulate and bringing the Peloponnesian War to an en ...

, the Persian-funded Peloponnesian fleet captured the Athenian alliance cities, and a decisive naval victory at Aegospotami

Aegospotami ( grc, Αἰγὸς Ποταμοί, ''Aigos Potamoi'') or AegospotamosMish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Aegospotami.” '' Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary''. 9th ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster Inc., 1985. , (ind ...

forced Athens to capitulate. The Athenian defeat established Sparta and its military forces in a dominant position in Greece.

End of Hegemony

Spartan ascendancy did not last long. By the end of the 5th century BC, Sparta had suffered severe casualties in the Peloponnesian Wars, and its conservative and narrow mentality alienated many of its former allies. At the same time, its military class – the Spartiatecaste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultur ...

– was in decline for several reasons:

*Firstly, the population declined due to Sparta's frequent wars in the late 5th century. Since ''Spartiates'' were required to marry late, birth rates also remained low, making it difficult to replace their losses from battles.

*Secondly, one could be demoted from the ''Spartiate'' status for several reasons, such as cowardice in battle or the inability to pay for membership in the ''syssitia

The syssitia ( grc, συσσίτια ''syssítia'', plural of ''syssítion'') were, in ancient Greece, common meals for men and youths in social or religious groups, especially in Crete and Sparta, but also in Megara in the time of Theognis of ...

''. Failure to pay became such an increasingly severe problem because commercial activities had started to develop in Sparta. However, commerce had become uncontrollable, leading to the complete ban of commerce in Sparta, resulting in fewer ways of earning income. Consequently, some ''Spartiates'' had to sell the land from which they made their livelihood. As the constitution made no provisions for promotion to the ''Spartiate'' caste, numbers gradually dwindled.

As Sparta's military power waned, Thebes also repeatedly challenged its authority. The ensuing Corinthian War

The Corinthian War (395–387 BC) was a conflict in ancient Greece which pitted Sparta against a coalition of city-states comprising Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos, backed by the Achaemenid Empire. The war was caused by dissatisfaction with ...

led to the humiliating Peace of Antalcidas that destroyed Sparta's reputation as the protector of Greek city-states' independence. At the same time, Spartan military prestige suffered a severe blow when a '' mora'' of 600 men was defeated by peltasts

A ''peltast'' ( grc-gre, πελταστής ) was a type of light infantryman, originating in Thrace and Paeonia, and named after the kind of shield he carried. Thucydides mentions the Thracian peltasts, while Xenophon in the Anabasis distin ...

(light infantry) under the command of the Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

general Iphicrates

Iphicrates ( grc-gre, Ιφικράτης; c. 418 BC – c. 353 BC) was an Athenian general, who flourished in the earlier half of the 4th century BC. He is credited with important infantry reforms that revolutionized ancient Greek warfare by ...

. Spartan authority finally collapsed after their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Leuctra by the Thebans under the leadership of Epaminondas

Epaminondas (; grc-gre, Ἐπαμεινώνδας; 419/411–362 BC) was a Greek general of Thebes and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a pre-eminent posit ...

in 371 BC. The battle killed a large number of ''Spartiates'', and resulted in the loss of the fertile Messenia region.

Army organization

Social structure

The Spartans (the " Lacedaemonians") divided themselves into three classes: *Full citizens, known as the '' Spartiates'' proper, or ''Hómoioi'' ("equals" or peers), who received a grant of land (''kláros'' or ''klēros'', "lot") for their military service. *'' Perioeci'' (the "dwellers nearby"), who were free non-citizens. They were generally merchants, craftsmen and sailors, and served as light infantry and auxiliary on campaigns. *The third and most numerous class was the ''Helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ...

'', state-owned serfs enslaved to farm the Spartiate ''klēros''. By the 5th century BC, the ''helots'', too, were used as light troops in skirmishes.

The ''Spartiates'' were the Spartan army's core: they participated in the Assembly (''Apella

The ecclesia or ekklesia (Greek: ἐκκλησία) was the citizens' assembly in the Ancient Greek city-state of Sparta. Unlike its more famous counterpart in Athens, the Spartan assembly had limited powers, as it did not debate; citizens coul ...

'') and provided the hoplites in the army. Indeed, they were supposed to be soldiers and nothing else, being forbidden to learn and exercise any other trade. To a large degree, in order to keep the vastly more numerous ''helots'' subdued, it would require the constant war footing of the Spartan society.Connolly (2006), p. 39 One of the major problems of the later Spartan society was the steady decline in its fully enfranchised citizens, which also meant a decline in available military manpower: the number of ''Spartiates'' decreased from 6,000 in 640 BC to 1,000 in 330 BC. The Spartans therefore had to use ''helots'' as hoplites, and occasionally they freed some of the Laconian helots, the '' neodamōdeis'' (the "newly enfranchised"), and gave them land to settle, in exchange for military service.

The ''Spartiate'' population was subdivided into age groups. They considered the youngest, those who were 20 years old, as weaker due to their lack of experience. They would only call the oldest, men who were up to 60 years old; or during a crisis, those who were 65 years old, to defend the baggage train in an emergency.

Tactical structure

The principal source on the Spartan Army's organization isXenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

, an admirer of the Spartans himself. His ''Constitution of Sparta'' offers a detailed overview of the Spartan state and society at the beginning of the 4th century BC. Other authors, notably Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

, also provide information, but they are not always as reliable as Xenophon's first-hand accounts.

Little is known of the earlier organization, and much is left open to speculation. The earliest form of social and military organization (during the 7th century BC) seems to have been set in accordance with the three tribes (''phylai'': the ''Pamphyloi'', ''Hylleis'' and ''Dymanes''), who appeared in the Second Messenian War (685–668 BC). A further subdivision was the "fraternity" (''phratra''), of which 27, or nine per tribe, are recorded.Sekunda (1998), p. 13. Eventually, this system was replaced by five territorial divisions, the ''obai'' ("villages"), which supplied a '' lochos'' of about 1,000 men each.Sekunda (1998), p. 14 This system was still used during the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

, as Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

had made references to the "''lochoi''" in his ''Histories

Histories or, in Latin, Historiae may refer to:

* the plural of history

* ''Histories'' (Herodotus), by Herodotus

* ''The Histories'', by Timaeus

* ''The Histories'' (Polybius), by Polybius

* ''Histories'' by Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), ...

''.Connolly (2006), p. 41.

The changes that occurred between the Persian and the Peloponnesian Wars were not documented. Still, according to Thucydides, at Mantinea

Mantineia (also Mantinea ; el, Μαντίνεια; also Koine Greek ''Antigoneia'') was a city in ancient Arcadia, Greece, which was the site of two significant battles in Classical Greek history.

In modern times it is a former municipality in ...

in 418 BC, there were seven ''lochoi'' present, each subdivided into four ''pentekostyes'' of 128 men, which were further subdivided into four ''enōmotiai'' of 32 men, giving a total of 3,584 men for the main Spartan army. By the end of the Peloponnesian War, the structure of the army had evolved further, to address the shortages in manpower and create a more flexible system which allowed the Spartans to send smaller detachments on campaigns or garrisons outside their homeland.Sekunda (1998), p. 15. According to Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

, the basic Spartan unit remained the ''enōmotia'', with 36 men in three files of twelve under an ''enōmotarches''. Two ''enōmotiai'' formed a ''pentēkostys'' of 72 men under a ''pentēkontēr'', and two ''pentēkostyai'' were grouped into a ''lochos'' of 144 men under a ''lochagos''. Four ''lochoi'' formed a '' mora'' of 576 men under a ''polemarch

A polemarch (, from , ''polemarchos'') was a senior military title in various ancient Greek city states (''poleis''). The title is derived from the words ''polemos'' (war) and ''archon'' (ruler, leader) and translates as "warleader" or "warlord" ...

os'', the Spartan army's largest single tactical unit.Connolly (2006), p. 40. Six ''morai'' composed the Spartan army on campaign, to which were added the '' Skiritai'' and the contingents of allied states.

The kings and the ''hippeis''

The two

The two kings

Kings or King's may refer to:

*Monarchs: The sovereign heads of states and/or nations, with the male being kings

*One of several works known as the "Book of Kings":

**The Books of Kings part of the Bible, divided into two parts

**The ''Shahnameh'' ...

would typically lead the full army in battles. Initially, both would go on campaign at the same time, but after the 6th century BC, only one would do so, with the other remaining in Sparta. Unlike other ''polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

'', their authority was severely circumscribed; actual power rested with the five elected ''ephoroi''. A select group of 300 men as royal guards, termed ''hippeis

''Hippeis'' ( grc, ἱππεῖς, singular ἱππεύς, ''hippeus'') is a Greek term for cavalry. In ancient Athenian society, after the political reforms of Solon, the ''hippeus'' was the second highest of the four social classes. It was c ...

'' ("cavalrymen"), accompanied the kings. Despite their title, they were infantry hoplites like all ''Spartiatai''. Indeed, the Spartans did not utilize a cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

of their own until late into the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

. By then, small units of 60 cavalrymen were attached to each ''mora''. The ''hippeis'' belonged to the first ''mora'' and were the Spartan army's elite, being deployed on the honorary right side of the battle line. They were selected every year by specially commissioned officials, the ''hippagretai'', drafted from experienced men who already had sons as heirs. This was to ensure that their line would be able to continue.

Training

At first, in the archaic period of 700–600 BC, education for both sexes was, as in most Greek states, centred on the arts, with the male citizen population later receiving military education. However, from the 6th century onwards, the military character of the state became more pronounced, and education was totally subordinated to the needs of the military.Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

15th Edition

A Spartan male's involvement with the army began in infancy when the '' Gerousia'' first inspected him. Any baby judged weak or deformed was left at Mount Taygetus to die since the Spartan society was no place for those who could not fend for themselves. (The practice of discarding children at birth took place in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

as well.) Both boys and girls were brought up by the city women until the age of seven, when boys (''paidia'') were taken from their mothers and grouped together in "packs" (''agelai'') and were sent to what is almost equivalent to present-day military boot camp. This military camp was known as the Agoge. They became inured to hardship, being provided with scant food and clothing; this also encouraged them to steal, and if they were caught, they were punished – not for stealing, but for being caught. There is a characteristic story, told by Plutarch: "The boys make such a serious matter of their stealing, that one of them, as the story goes, who was carrying concealed under his cloak a young fox which he had stolen, suffered the animal to tear out his bowels with its teeth and claws, and died rather than have his theft detected." The boys were encouraged to compete against one another in games and mock fights and to foster an ''esprit de corps

Morale, also known as esprit de corps (), is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value ...

''. In addition, they were taught to read and write and learned the songs of Tyrtaios

Tyrtaeus (; grc-gre, Τυρταῖος ''Tyrtaios''; fl. mid-7th century BC) was a Greek elegiac poet from Sparta. He wrote at a time of two crises affecting the city: a civic unrest threatening the authority of kings and elders, later recalled i ...

, that celebrated Spartan exploits in the Second Messenian War. They learned to read and write not for cultural reasons, but so they could be able to read military maps. At the age of twelve, a boy was classed as a "youth" (). His physical education was intensified, discipline became much harsher, and the boys were loaded with extra tasks. The youths had to go barefoot, and were dressed only in a tunic

A tunic is a garment for the body, usually simple in style, reaching from the shoulders to a length somewhere between the hips and the knees. The name derives from the Latin ''tunica'', the basic garment worn by both men and women in Ancient Ro ...

both in summer and in winter.

Adulthood was reached at the age of 18, and the young adult (''eiren'') initially served as a trainer for the boys. At the same time, the most promising youths were included in the ''Krypteia

The Crypteia, also referred to as Krypteia or Krupteia ( Greek: κρυπτεία ''krupteía'' from κρυπτός ''kruptós'', "hidden, secret"), was an ancient Spartan state institution involving young Spartan men. It was an exclusive element o ...

''. If they survived the two years in the countryside they would become full blown soldiers. At 20, Spartans became eligible for military service and joined one of the messes (''syssitia

The syssitia ( grc, συσσίτια ''syssítia'', plural of ''syssítion'') were, in ancient Greece, common meals for men and youths in social or religious groups, especially in Crete and Sparta, but also in Megara in the time of Theognis of ...

''), which included 15 men of various ages. Those who were rejected retained a lesser form of citizenship, as only the soldiers were ranked among the ''homoioi''. However, even after that, and even during marriage and until about the age of 30, they would spend most of their day in the barracks

Barracks are usually a group of long buildings built to house military personnel or laborers. The English word originates from the 17th century via French and Italian from an old Spanish word "barraca" ("soldier's tent"), but today barracks are u ...

with their unit. Military duty lasted until the 60th year, but there are recorded cases of older people participating in campaigns in times of crisis.

Throughout their adult lives, the ''Spartiates'' continued to be subject to a training regime so strict that, as Plutarch says, "... they were the only men in the world with whom war brought a respite in the training for war." Bravery was the ultimate virtue for the Spartans: Spartan mothers would give their sons the shield with the words " eturnWith it or arriedon it!" (), that is to say, either victorious or dead, since in battle, the heavy hoplite shield would be the first thing a fleeing soldier would be tempted to abandon –- ''rhipsaspia'', "dropping the shield", was a synonym for desertion in the field.

The army on campaign

Tactics

Like the other Greek city-states' armies, the Spartan army was an infantry-based army that fought using the phalanx formation. The Spartans themselves did not introduce any significant changes or tactical innovations in ''

Like the other Greek city-states' armies, the Spartan army was an infantry-based army that fought using the phalanx formation. The Spartans themselves did not introduce any significant changes or tactical innovations in ''hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The ...

'' warfare, but their constant drill and superb discipline made their phalanx much more cohesive and effective. The Spartans employed the phalanx in the classical style in a single line, uniformly deep in files of 8 to 12 men. When fighting alongside their allies, the Spartans would normally occupy the honorary right flank. If, as usually happened, the Spartans achieved victory on their side, they would then wheel left and roll up the enemy formation.

During the Peloponnesian War, battle engagements became more fluid, light troops became increasingly used, and tactics evolved to meet them. However, in direct confrontations between the two opposing phalanxes, stamina and "pushing ability" were what counted. It was only when the Thebans

Thebes (; ell, Θήβα, ''Thíva'' ; grc, Θῆβαι, ''Thêbai'' .) is a city in Boeotia, Central Greece. It played an important role in Greek myths, as the site of the stories of Cadmus, Oedipus, Dionysus, Heracles and others. Archaeol ...

, under Epaminondas

Epaminondas (; grc-gre, Ἐπαμεινώνδας; 419/411–362 BC) was a Greek general of Thebes and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a pre-eminent posit ...

, increased the depth of a part of their formation at the Battle of Leuctra that caused the Spartan phalanx formation to break.

On the march

According toXenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies o ...

, the ephor

The ephors were a board of five magistrates in ancient Sparta. They had an extensive range of judicial, religious, legislative, and military powers, and could shape Sparta's home and foreign affairs.

The word "''ephors''" (Ancient Greek ''ép ...

s would first mobilize the army. After a series of religious ceremonies and sacrifices, the army assembled and set out. The army proceeding was led by the king, with the ''skiritai'' and cavalry detachments acting as an advance guard and scouting parties. The necessary provisions (barley, cheese, onions and salted meat) were carried along with the army, and a helot manservant accompanied each Spartan. Each ''mora'' marched and camped separately, with its baggage train. The army gave sacrifice every morning as well as before battle by the king and the officers; if the omens were not favourable, a pious leader might refuse to march or engage with the enemy.

Clothing, arms, and armor

The Spartans used the same typical ''hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The ...

'' equipment as their other Greek neighbors; the only distinctive Spartan features were the crimson tunic (''chitōn'') and cloak (''himation''), as well as long hair, which the Spartans retained to a far later date than most Greeks. To the Spartans, long hair kept its older Archaic meaning as the symbol of a free man; to the other Greeks, by the 5th century, the hairstyle's peculiar association with the Spartans had come to signify pro-Spartan sympathies.

Classical period

The letterlambda

Lambda (}, ''lám(b)da'') is the 11th letter of the Greek alphabet, representing the voiced alveolar lateral approximant . In the system of Greek numerals, lambda has a value of 30. Lambda is derived from the Phoenician Lamed . Lambda gave ri ...

(Λ), standing for Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia ( el, Λακωνία, , ) is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word '' laconic''—to speak in a blunt, c ...

or Lacedaemon, which was painted on the Spartans' shields, was first adopted in 420s BC and quickly became a widely known Spartan symbol. Military families passed on their shields to each generation as family heirlooms. The Spartan shields' technical evolution and design evolved from bash

Bash or BASH may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Bash!'' (Rockapella album), 1992

* ''Bash!'' (Dave Bailey album), 1961

* '' Bash: Latter-Day Plays'', a dramatic triptych

* ''BASH!'' (role-playing game), a 2005 superhero game

* "Bash" ('' ...

ing and shield wall

A shield wall ( or in Old English, in Old Norse) is a military formation that was common in ancient and medieval warfare. There were many slight variations of this formation,

but the common factor was soldiers standing shoulder to should ...

tactics. They were of such great importance in the Spartan army that while losing a sword and a spear was an exception, to lose a shield was a sign of disgrace. Not only did a shield protect the user, but it also protected the whole phalanx formation. To come home without the shield was the mark of a deserter; ''rhipsaspia'', or "dropping the shield," was a synonym for desertion in the field. Mothers bidding farewell to their sons would encourage them to come back with their shields, often saying goodbyes such as ''"Son, either with this or on this"'' (Ἢ τὰν ἢ ἐπὶ τᾶς). This saying implied that they should return only in victory, a controlled retreat, or dead, with their body carried upon their shield.

Spartan hoplites were often depicted bearing a transverse horsehair crest on their helmet, which was possibly used to identify officers. During the Archaic period, Spartans were armored with flanged bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids suc ...

cuirass

A cuirass (; french: cuirasse, la, coriaceus) is a piece of armour that covers the torso, formed of one or more pieces of metal or other rigid material. The word probably originates from the original material, leather, from the French '' cuirac ...

es, leg greave

A greave (from the Old French ''greve'' "shin, shin armour") or jambeau is a piece of armour that protects the leg.

Description

The primary purpose of greaves is to protect the tibia from attack. The tibia, or shinbone, is very close to the sk ...

s, and a helmet, often of the Corinthian type. It is often disputed which torso armor the Spartans wore during the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

. However, it seems likely they either continued to wear bronze cuirasses of a more sculptured type or instead had adopted the '' linothōrax''. During the later 5th century BC, when warfare had become more flexible, and full-scale phalanx confrontations became rarer, the Greeks abandoned most forms of body armor. The Lacedaemonians also adopted a new tunic, the '' exōmis'', which could be arranged to leave the right arm and shoulder uncovered and free for action in combats.

The Spartan's main weapon was the ''dory

A dory is a small, shallow-draft boat, about long. It is usually a lightweight boat with high sides, a flat bottom and sharp bows. It is easy to build because of its simple lines. For centuries, the dory has been used as a traditional fishin ...

'' spear. For long-range attacks, they carried a javelin

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon, but today predominantly for sport. The javelin is almost always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the ...

. The ''Spartiates'' were also always armed with a ''xiphos

The ''xiphos'' ( grc, ξίφος ; plural ''xiphe'', grc, ξίφη ) is a double-edged, one-handed Iron Age straight shortsword used by the ancient Greeks. It was a secondary battlefield weapon for the Greek armies after the dory or javelin. ...

'' as a secondary weapon. Among most Greek warriors, this weapon had an iron blade of about 60 centimeters; however, the Spartan version was typically only 30–45 centimetres in length. The Spartans' shorter weapon proved deadly in the crush caused by colliding phalanxes formations – it was capable of being thrust through gaps in the enemy's shield wall and armor, where there was no room for the longer weapons. The groin and throat were among the favorite targets. According to Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

when a Spartan was asked why his sword was so short he replied, "So that we may get close to the enemy." In another, a Spartan complained to his mother that the sword was short, to which she simply told him to step closer to the enemy. As an alternative to the ''xiphos'', some Spartans selected the '' kopis'' as their secondary weapon. Unlike the ''xiphos'', which was a thrusting weapon, the ''kopis'' was a hacking weapon in the form of a thick, curved iron sword. The Spartans retained the traditional hoplite phalanx until the reforms of Cleomenes III

Cleomenes III ( grc, Κλεομένης) was one of the two kings of Sparta from 235 to 222 BC. He was a member of the Agiad dynasty and succeeded his father, Leonidas II. He is known for his attempts to reform the Spartan state.

From 229 to ...

when they were re-equipped with the Macedonian '' sarissa'' and trained in the phalanx style.

Spartans trained in ''pankration

Pankration (; el, παγκράτιον) was a sporting event introduced into the Greek Olympic Games in 648 BC, which was an empty-hand submission sport with few rules. The athletes used boxing and wrestling techniques but also others, suc ...

'', a famous martial art in Ancient Greece that consisted of boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermined ...

and grappling

Grappling, in hand-to-hand combat, describes sports that consist of gripping or seizing the opponent. Grappling is used at close range to gain a physical advantage over an opponent, either by imposing a position or causing injury. Grappling ...

. Spartans were so adept in ''pankration'' that they were mostly forbidden to compete when it was inducted in the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a multi ...

.

Hellenistic period

During theHellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

, Spartan equipment evolved drastically. Since the early 3rd century BC, the '' pilos'' helmet had become almost standard within the Spartan army, being in use by the Spartans until the end of the Classical era. Also, after the "Iphicratean reforms," peltasts

A ''peltast'' ( grc-gre, πελταστής ) was a type of light infantryman, originating in Thrace and Paeonia, and named after the kind of shield he carried. Thucydides mentions the Thracian peltasts, while Xenophon in the Anabasis distin ...

became a much more common sight on the Greek battlefield, and themselves became more heavily armed. In response to Iphicrates

Iphicrates ( grc-gre, Ιφικράτης; c. 418 BC – c. 353 BC) was an Athenian general, who flourished in the earlier half of the 4th century BC. He is credited with important infantry reforms that revolutionized ancient Greek warfare by ...

' victory over Sparta in 392 BC, Spartan hoplites started abandoning body armour. Eventually, they wore almost no armour apart from a shield, leg greaves, bracelets, helmet and a robe. Spartans did start to readopt armour in later periods, but on a much lesser scale than during the Archaic period. Finally, during 227 BC, Cleomenes' reforms introduced updated equipment to Sparta, including the Macedonian '' sarissa'' (pike). However, pike-men armed with the ''sarissa'' never outnumbered troops equipped in the ''hoplite'' style. It was also at that time Sparta adopted its own cavalry and archers.

Education and the Spartan code

Spartan education

The Spartan public education system, the ''agoge

The ( grc-gre, ἀγωγή in Attic Greek, or , in Doric Greek) was the rigorous education and training program mandated for all male Spartan citizens, with the exception of the firstborn son in the ruling houses, Eurypontid and Agiad. The ...

'', trained the mind as well as the body. Spartans were not only literate but admired for their intellectual culture and poetry. Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no t ...

said the "most ancient and fertile homes of philosophy among the Greeks are Crete and Sparta, where are found more sophists than anywhere on earth." The state provided public education

State schools (in England, Wales, Australia and New Zealand) or public schools (Scottish English and North American English) are generally primary or secondary educational institution, schools that educate all students without charge. They are ...

for girls and boys, and consequently, the literacy rate was higher in Sparta than in other Greek city-states.Soriano (2005), p. 85. In education, the Spartans gave sports the most emphasis.

Self-discipline, not ''kadavergehorsam'' (mindless obedience), was the goal of Spartan education. Sparta placed the values of liberty, equality, and fraternity at the center of their ethical system. These values applied to every full Spartan citizen, immigrant, merchant, and even to the ''helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ...

'', but not the dishonored. ''Helots'' are unique in the history of slavery in that, unlike traditional slaves, they were allowed to keep and gain wealth. For example, they could keep half of their agricultural produce and presumably could also accumulate wealth by selling them. There are known to have been occasions that a ''helot'' with enough money could purchase their freedom from the state.

Spartan code of honor

The Spartan ''

The Spartan ''hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The ...

'' followed a strict laconic code of honor. No soldier was considered superior to another. Suicidal recklessness, misbehavior, and rage were prohibited in the Spartan army, as those behaviours endangered the phalanx. Recklessness could also lead to dishonor, as in the case of Aristodemus.Schmitz vol 1. p304 Spartans regarded those who fight, while still wishing to live, as more valorous than those who don't care if they die. They believed that a warrior must not fight with raging anger but with calm determination. Spartans must walk without any noise and speak only with few words by the laconic way of life. Other ways for Spartans to be dishonored include dropping the shield (''rhipsaspia''), failing to complete the training, and deserting in battles. Dishonored Spartans were labelled as outcasts and would be forced to wear different clothing for public humiliation. In battles, the Spartans told stories of valor to inspire the troops and, before a major confrontation, they sang soft songs to calm the nerves.Soriano (2005), pp. 90–91.

Spartan navy

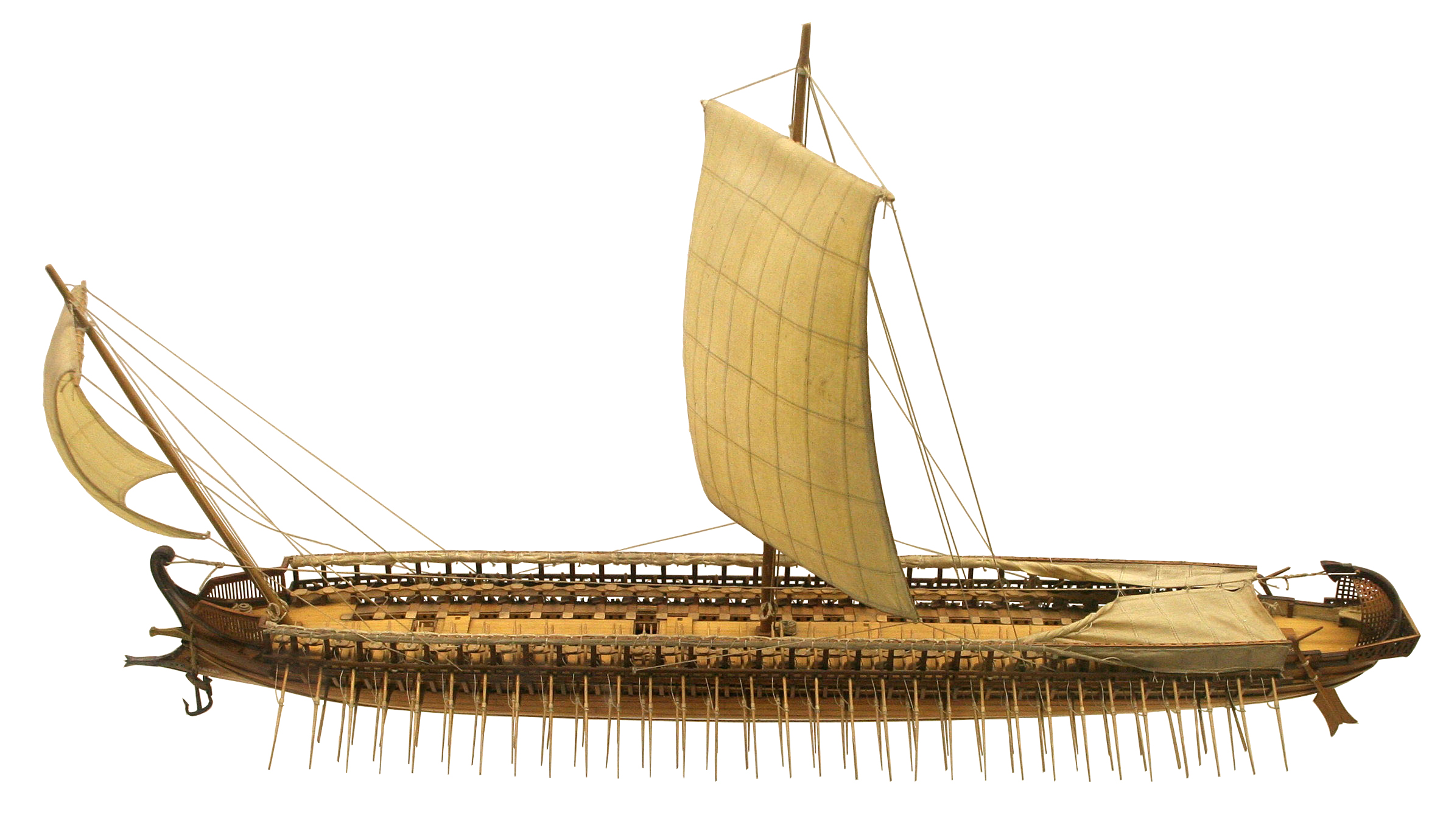

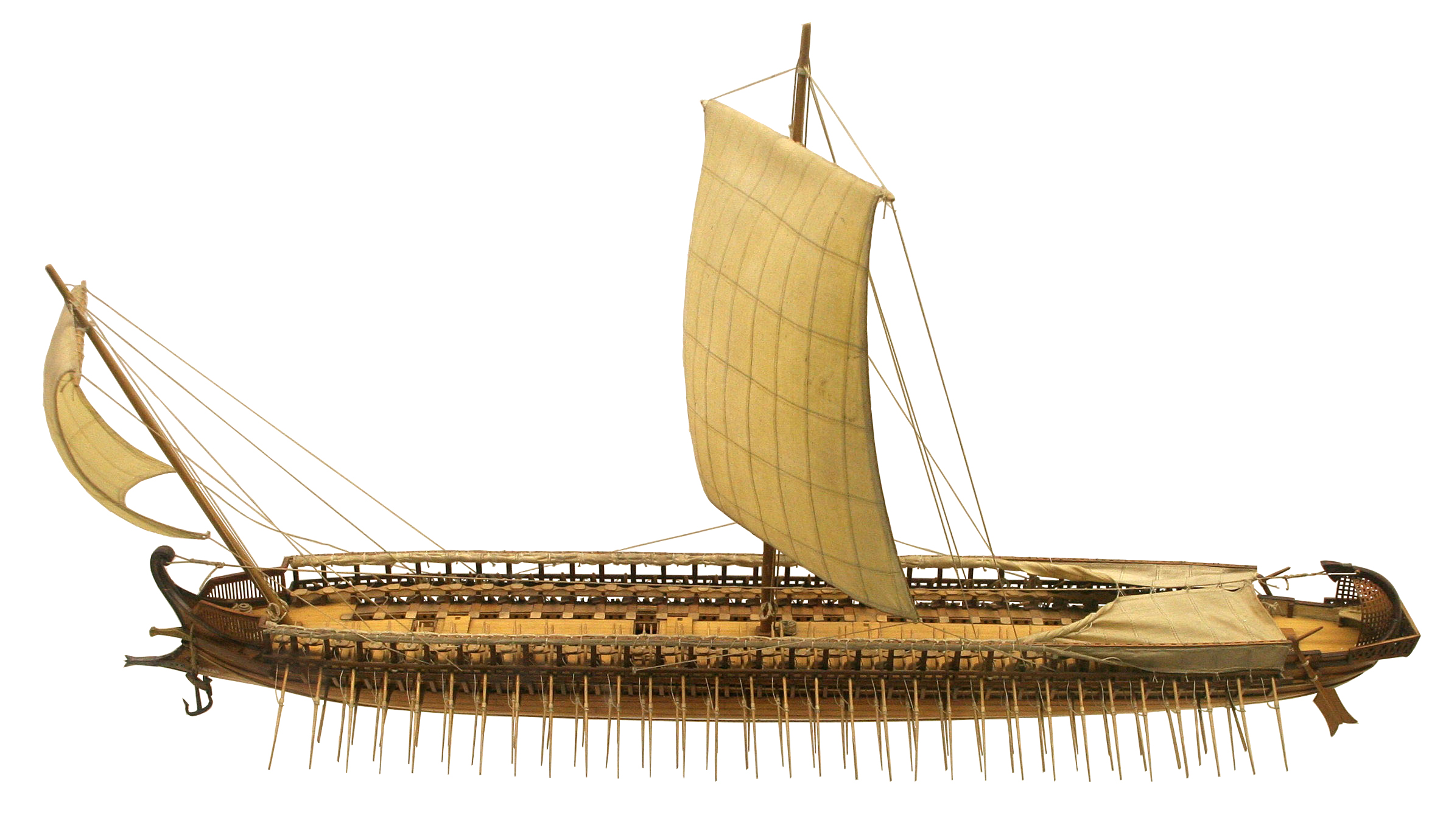

Throughout their history, the Spartans were a land-based force ''par excellence''. During

Throughout their history, the Spartans were a land-based force ''par excellence''. During the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

, they contributed a small navy of 20 ''triremes'' and provided the overall fleet commander. Nevertheless, they largely relied on their allies, primarily the Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

ians, for naval power. This fact meant that, when the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

broke out, the Spartans were supreme on land, but the Athenians excelled at sea. The Spartans repeatedly ravaged Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean ...

, but the Athenians who were kept supplied by sea, were able to stage raids of their own around the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridge which ...

with their navy. Eventually, it was the creation of a navy that enabled Sparta to overcome Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

. With Persian gold, Lysander

Lysander (; grc-gre, Λύσανδρος ; died 395 BC) was a Spartan military and political leader. He destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, forcing Athens to capitulate and bringing the Peloponnesian War to an en ...

, appointed navarch

Navarch ( el, ναύαρχος, ) is an Anglicisation of a Greek word meaning "leader of the ships", which in some states became the title of an office equivalent to that of a modern admiral.

Historical usage

Not all states gave their naval ...

in 407 BC, was able to master a strong navy and successfully challenged and destroyed Athenian predominance in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

. However, the Spartan engagement with the sea would be short-lived, and did not survive the turmoils of the Corinthian War

The Corinthian War (395–387 BC) was a conflict in ancient Greece which pitted Sparta against a coalition of city-states comprising Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos, backed by the Achaemenid Empire. The war was caused by dissatisfaction with ...

. In the Battle of Cnidus of 394 BC, the Spartan navy was decisively defeated by a joint Athenian-Persian fleet, marking the end of Sparta's brief naval supremacy. The final blow would be given 20 years later, at the Battle of Naxos in 376 BC. The Spartans periodically maintained a small fleet after that, but its effectiveness was limited. The last revival of the Spartan naval power was under Nabis, who created a fleet to control the Laconian coastline with aid from his Cretan

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

allies.

The fleet was commanded by , who were appointed for a strictly one-year term, and apparently could not be reappointed. The admirals were subordinated to the vice-admiral, called . This position was seemingly independent of the one-year term clause because it was used in 405 BC to give Lysander command of the fleet after he was already an admiral for a year.

Wars and battles

Messenian Wars

Wars with Argos

Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

*Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: (''Thermopylai'') , Demotic Greek (Greek): , (''Thermopyles'') ; "hot gates") is a place in Greece where a narrow coastal passage existed in antiquity. It derives its name from its hot sulphur ...

*Artemisium

Artemisium or Artemision (Greek: Ἀρτεμίσιον) is a cape in northern Euboea, Greece. The legendary hollow cast bronze statue of Zeus, or possibly Poseidon, known as the ''Artemision Bronze'', was found off this cape in a sunken ship,Wo ...

* Salamis

*Plataea

Plataea or Plataia (; grc, Πλάταια), also Plataeae or Plataiai (; grc, Πλαταιαί), was an ancient city, located in Greece in southeastern Boeotia, south of Thebes.Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Plataea.” '' Webst ...

* Mycale

*Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of , usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There are also wheelchair div ...

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

* Sybota

*Potidaea

__NOTOC__

Potidaea (; grc, Ποτίδαια, ''Potidaia'', also Ποτείδαια, ''Poteidaia'') was a colony founded by the Corinthians around 600 BC in the narrowest point of the peninsula of Pallene, the westernmost of three peninsulas a ...

*Chalcis

Chalcis ( ; Ancient Greek & Katharevousa: , ) or Chalkida, also spelled Halkida (Modern Greek: , ), is the chief town of the island of Euboea or Evia in Greece, situated on the Euripus Strait at its narrowest point. The name is preserved fro ...

*Rhium

Rio ( el, Ρίο, ''Río'', formerly , ''Rhíon''; Latin: ''Rhium'') is a town in the suburbs of Patras and a former municipality in Achaea, West Greece, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Patras, of ...

*Naupactus

Nafpaktos ( el, Ναύπακτος) is a town and a former municipality in Aetolia-Acarnania, West Greece, situated on a bay on the north coast of the Gulf of Corinth, west of the mouth of the river Mornos.

It is named for Naupaktos (, Lati ...

*Mytilene

Mytilene (; el, Μυτιλήνη, Mytilíni ; tr, Midilli) is the capital of the Greek island of Lesbos, and its port. It is also the capital and administrative center of the North Aegean Region, and hosts the headquarters of the University o ...

*Tanagra

Tanagra ( el, Τανάγρα) is a town and a municipality north of Athens in Boeotia, Greece. The seat of the municipality is the town Schimatari. It is not far from Thebes, and it was noted in antiquity for the figurines named after it. The T ...

* Olpae

*Pylos

Pylos (, ; el, Πύλος), historically also known as Navarino, is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of the municipality Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is ...

* Sphacteria

*Amphipolis

Amphipolis ( ell, Αμφίπολη, translit=Amfipoli; grc, Ἀμφίπολις, translit=Amphipolis) is a municipality in the Serres regional unit, Macedonia, Greece. The seat of the municipality is Rodolivos. It was an important ancient Gr ...

* First Mantinea

*Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415–413 BC during the Peloponnesian War between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a de ...

* Syme

* Cynossema

*Abydos Abydos may refer to:

*Abydos, a progressive metal side project of German singer Andy Kuntz

*Abydos (Hellespont), an ancient city in Mysia, Asia Minor

* Abydos (''Stargate''), name of a fictional planet in the ''Stargate'' science fiction universe ...

*Cyzicus

Cyzicus (; grc, Κύζικος ''Kúzikos''; ota, آیدینجق, ''Aydıncıḳ'') was an ancient Greek town in Mysia in Anatolia in the current Balıkesir Province of Turkey. It was located on the shoreward side of the present Kapıdağ Peni ...

*Notium

Notion or Notium ( Ancient Greek , 'southern') was a Greek city-state on the west coast of Anatolia; it is about south of Izmir in modern Turkey, on the Gulf of Kuşadası. Notion was located on a hill from which the sea was visible; it served ...

* Arginusae

*Aegospotami

Aegospotami ( grc, Αἰγὸς Ποταμοί, ''Aigos Potamoi'') or AegospotamosMish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Aegospotami.” '' Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary''. 9th ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster Inc., 1985. , (ind ...

The

Corinthian War

The Corinthian War (395–387 BC) was a conflict in ancient Greece which pitted Sparta against a coalition of city-states comprising Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos, backed by the Achaemenid Empire. The war was caused by dissatisfaction with ...

The

Boeotian War

The Boeotian War broke out in 378 BC as the result of a revolt in Thebes against Sparta. The war saw Thebes become dominant in the Greek World at the expense of Sparta. However, by the end of the war Thebes’ greatest leaders, Pelopidas and Ep ...

Chremonidean War

The Chremonidean War (267–261 BC) was fought by a coalition of some Greek city-states and Ptolemaic Egypt against Antigonid Macedonian domination. It ended in a Macedonian victory which confirmed Antigonid control over the city-states of Gr ...

The

Cleomenean War

The Cleomenean WarPolybius. ''The Rise of the Roman Empire'', 2.46. (229/228–222 BC) was fought between Sparta and the Achaean League for the control of the Peloponnese. Under the leadership of king Cleomenes III, Sparta initially had the upp ...

In popular culture

See also

* List of Spartan kings * Scytale * Cryptia *Clearchus of Sparta

Clearchus or Clearch ( grc, Κλέαρχος; 450 BC – 401 BC), the son of Rhamphias, was a Spartan general and mercenary, noted for his service under Cyrus the Younger.

Biography

Peloponnesian War

Born about the middle of the 5th century ...

* Xanthippus of Carthage

* Homosexuality in the militaries of ancient Greece

Notes and references

Sources

* * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Spartan Army Warrior code