The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among

Carlists

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link=no) or The Uprising ( es, La Sublevación, link=no) among Republicans. was a

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

in

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

fought from 1936 to 1939 between the

Republicans and the

Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the

left-leaning Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

government of the

Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 ...

, and consisted of various

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

,

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

,

separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

,

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

, and

republican parties, some of which had opposed the government in the pre-war period. The opposing Nationalists were an alliance of

Falangists,

monarchists

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

,

conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, and

traditionalists led by a

military junta

A military junta () is a government led by a committee of military leaders. The term ''junta'' means "meeting" or "committee" and originated in the national and local junta organized by the Spanish resistance to Napoleon's invasion of Spain in ...

among whom General

Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

quickly achieved a preponderant role. Due to the international

political climate at the time, the war had many facets and was variously viewed as

class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The form ...

, a

religious struggle, a struggle between

dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship a ...

and

republican democracy

A democratic republic is a form of government operating on principles adopted from a republic and a democracy. As a cross between two exceedingly similar systems, democratic republics may function on principles shared by both republics and democrac ...

, between

revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

and

counterrevolution

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

, and between

fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and t ...

and

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

. According to

Claude Bowers

Claude Gernade Bowers (November 20, 1878 – January 21, 1958) was a newspaper columnist and editor, author of best-selling books on American history, Democratic Party politician, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt's ambassador to Spain (1933� ...

, U.S. ambassador to Spain during the war, it was the "

dress rehearsal" for

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

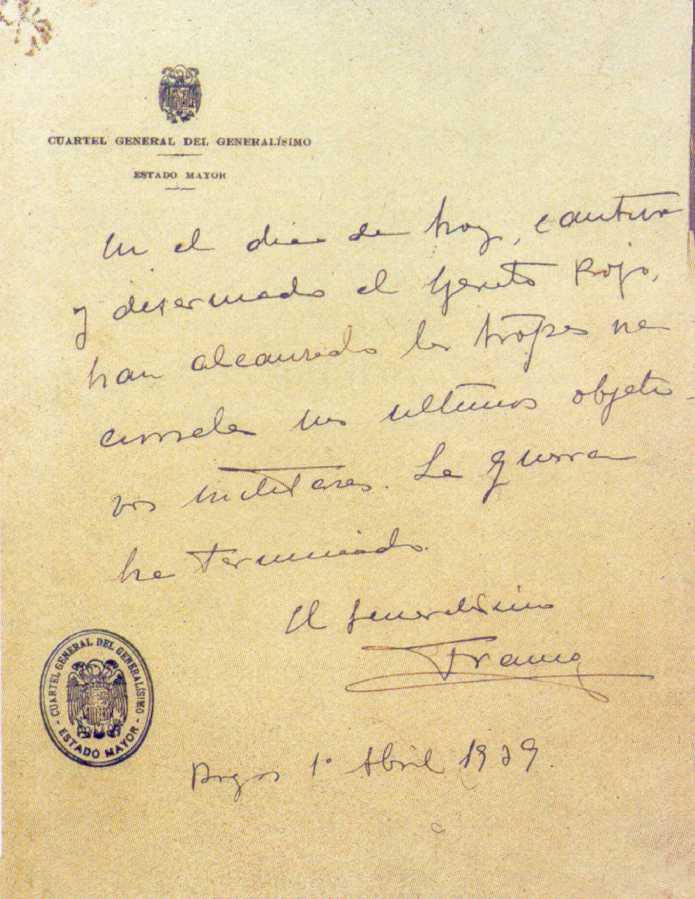

. The Nationalists won the war, which ended in early 1939, and ruled Spain until Franco's death in November 1975.

The war began after the partial failure of the

coup d'état of July 1936 against the Republican government by a group of generals of the

Spanish Republican Armed Forces

The Spanish Republican Armed Forces ( es, Fuerzas Armadas de la República Española) were initially formed by the following two branches of the military of the Second Spanish Republic:

*Spanish Republican Army (''Ejército de la República Espa ...

, with General

Emilio Mola as the primary planner and leader and having General

José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936), was a Spanish general, one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' which started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title of "Marquis o ...

as a figurehead. The government at the time was a coalition of Republicans, supported in the

Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of ...

by communist and socialist parties, under the leadership of

centre-left

Centre-left politics lean to the left on the left–right political spectrum but are closer to the centre than other left-wing politics. Those on the centre-left believe in working within the established systems to improve social justice. The ...

President

Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Re ...

. The Nationalist group was supported by a number of conservative groups, including

CEDA, monarchists, including both the opposing

Alfonsists and the religious conservative

Carlists

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty – one descended from Don Carlos, Count of Molina (1788–1855) – ...

, and the

Falange Española de las JONS

The Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FE de las JONS; ), was a fascist political party founded in Spain in 1934 as merger of the Falange Española and the Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista. FE de las JON ...

, a fascist political party. After the deaths of Sanjurjo,

Emilio Mola and

Manuel Goded Llopis

Manuel Goded Llopis (15 October 1882 – 12 August 1936) was a Spanish Army general who was one of the key figures in the July 1936 revolt against the democratically elected Second Spanish Republic. Having unsuccessfully led an attempted insur ...

, Franco emerged as the remaining leader of the Nationalist side.

The coup was supported by military units in

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

,

Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

,

Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is the capital and most populated municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence o ...

,

Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Province of Zaragoza, Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Ara ...

,

Valladolid

Valladolid () is a municipality in Spain and the primary seat of government and de facto capital of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. It has a population around 300,000 peop ...

,

Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

,

Córdoba, and

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

. However, rebelling units in almost all important cities—such as

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

,

Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

,

Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

,

Bilbao

)

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize = 275 px

, map_caption = Interactive map outlining Bilbao

, pushpin_map = Spain Basque Country#Spain#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption ...

, and

Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most po ...

—did not gain control, and those cities remained under the control of the government. This left Spain militarily and politically divided. The Nationalists and the Republican government fought for control of the country. The Nationalist forces received munitions, soldiers, and air support from

Fascist Italy,

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

, while the Republican side received support from the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

and

Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. Other countries, such as the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

,

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

, continued to recognise the Republican government but followed an official policy of

non-intervention

Non-interventionism or non-intervention is a political philosophy or national foreign policy doctrine that opposes interference in the domestic politics and affairs of other countries but, in contrast to isolationism, is not necessarily opposed t ...

. Despite this policy, tens of thousands of citizens from non-interventionist countries directly participated in the conflict. They fought mostly in the pro-Republican

International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed ...

, which also included several thousand exiles from pro-Nationalist regimes.

The Nationalists advanced from their strongholds in the south and west, capturing most of Spain's northern coastline in 1937. They also besieged Madrid and the area to its south and west for much of the war. After much of

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

was captured in 1938 and 1939, and Madrid cut off from Barcelona, the Republican military position became hopeless. Following the fall without resistance of Barcelona in January 1939, the Francoist regime was recognised by France and the United Kingdom in February 1939. On 5 March 1939, in response to an alleged increasing communist dominance of the republican government and the deteriorating military situation, Colonel

Segismundo Casado

Segismundo Casado López (10 October 1893 – 18 December 1968) was a Spanish Army officer; he served during the late Restoration, the Primo de Rivera dictatorship and the Second Spanish Republic. Following outbreak of the Spanish Civil W ...

led a

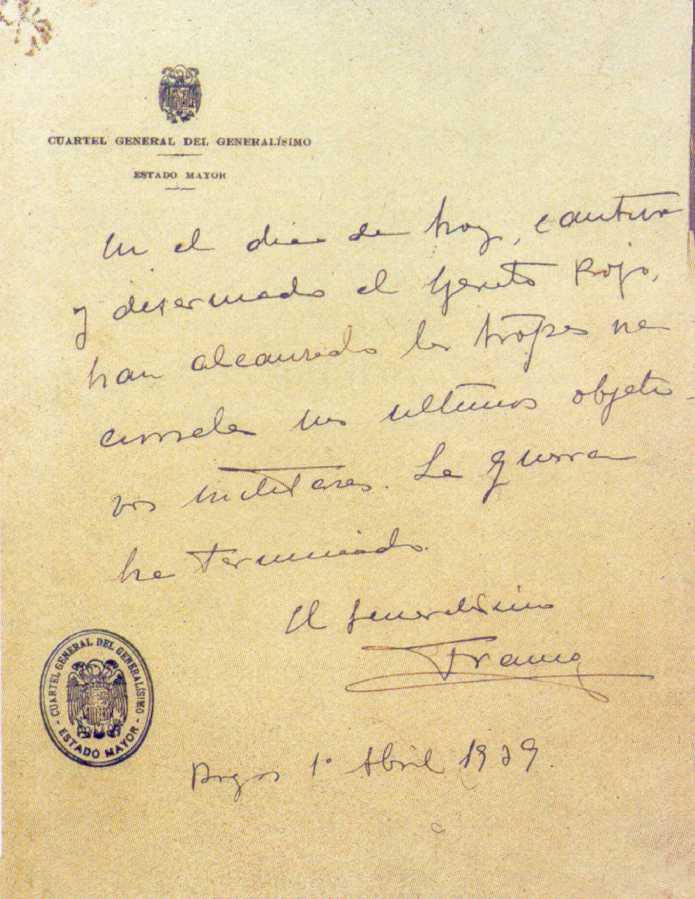

military coup against the Republican government, with the intention of seeking peace with the Nationalists. These peace overtures, however, were rejected by Franco. Following internal conflict between Republican factions in Madrid in the same month, Franco entered the capital and declared victory on 1 April 1939. Hundreds of thousands of Spaniards fled to refugee camps in

southern France

Southern France, also known as the South of France or colloquially in French as , is a defined geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', A ...

.

Those associated with the losing Republicans who stayed were persecuted by the victorious Nationalists. Franco established a dictatorship in which all right-wing parties were fused into the structure of the Franco regime.

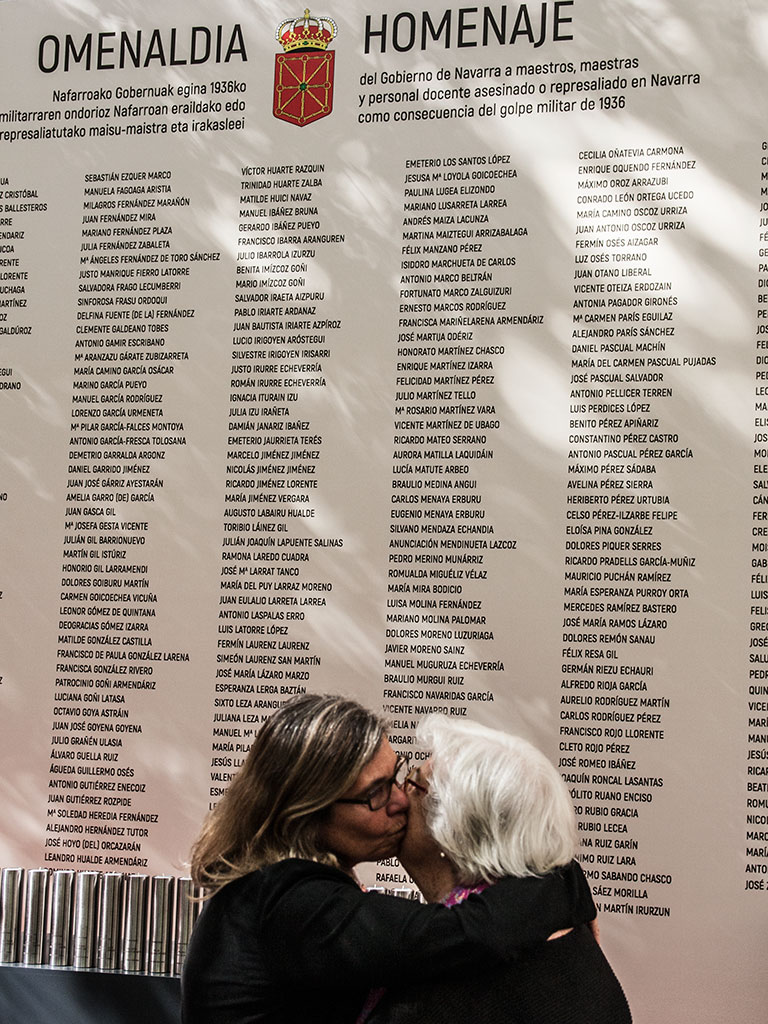

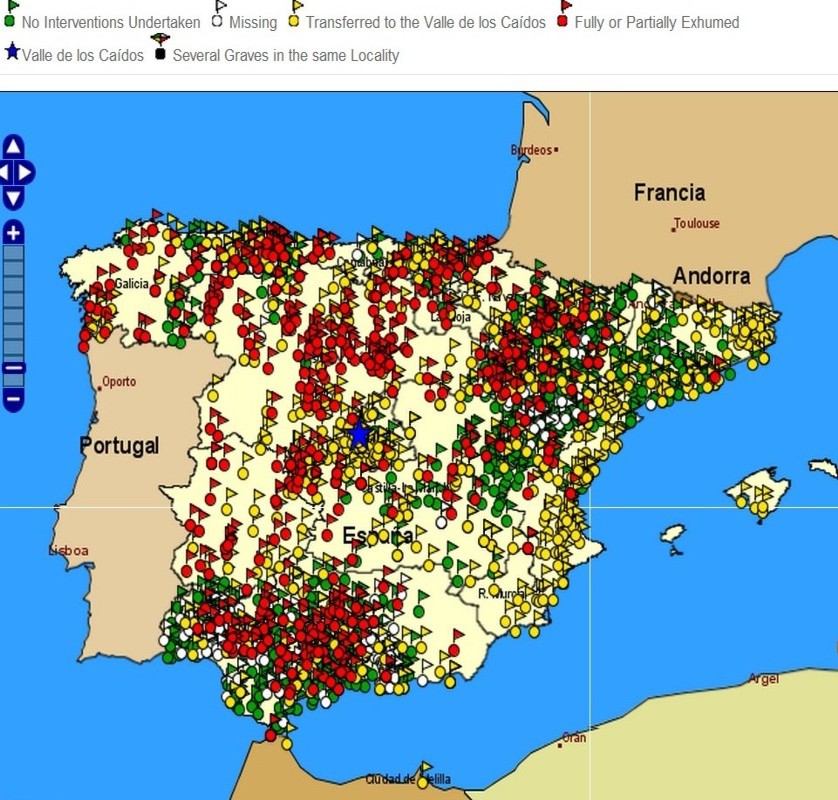

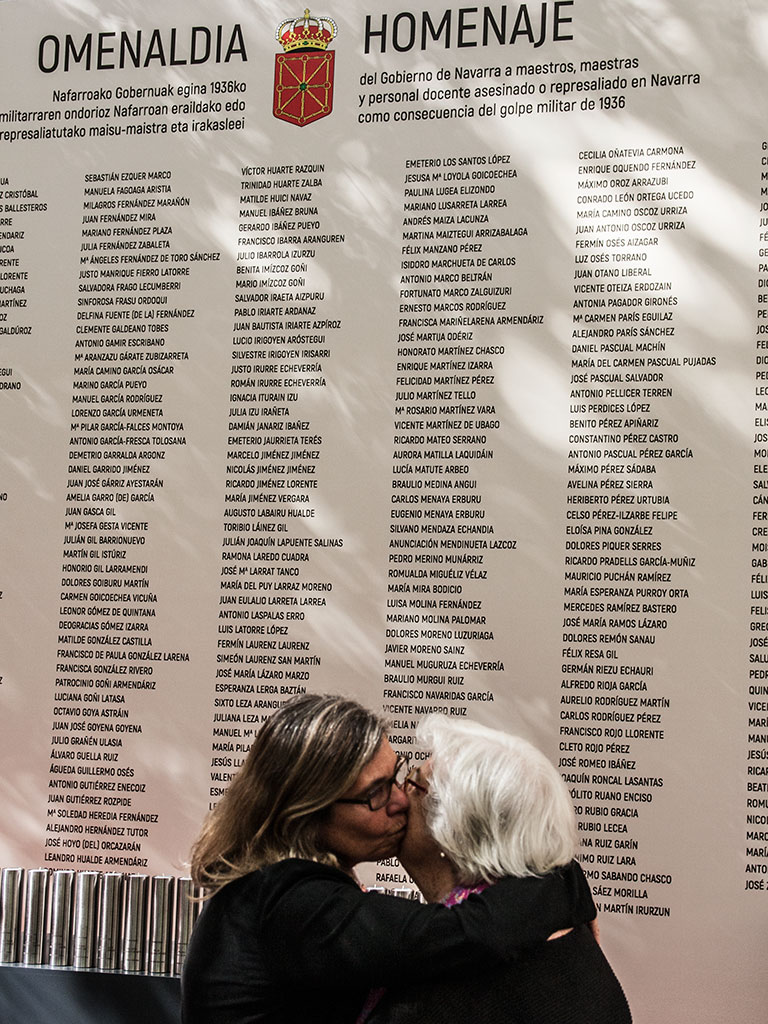

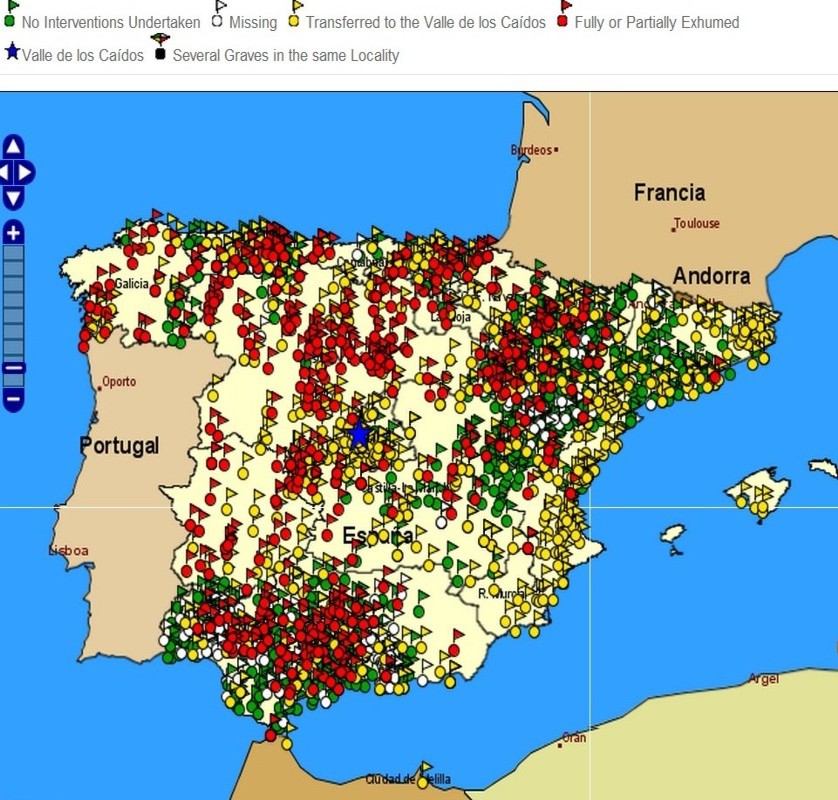

The war became notable for the passion and political division it inspired and for the many atrocities that occurred.

Organised purges occurred in territory captured by Franco's forces so they could consolidate their future regime.

Mass executions on a lesser scale also took place in areas controlled by the Republicans, with the participation of local authorities varying from location to location.

Background

The 19th century was a turbulent time for Spain. Those in favour of reforming the Spanish government vied for political power with

conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

who intended to prevent such reforms from being implemented. In a tradition that started with the

Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy ( es, link=no, Constitución Política de la Monarquía Española), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz ( es, link=no, Constitución de Cádiz) and as ''La Pepa'', was the first Constituti ...

, many liberals sought to curtail the authority of the

Spanish monarchy

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

as well as to establish a nation-state under

their ideology and philosophy. The reforms of 1812 were short-lived as they were almost immediately overturned by

King Ferdinand VII when he dissolved the aforementioned constitution. This ended the

Trienio Liberal government. Twelve successful coups were carried out between 1814 and 1874. There were several attempts to realign the political system to match social reality. Until the 1850s, the economy of Spain was primarily based on

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

. There was little development of a bourgeois industrial or commercial class. The land-based oligarchy remained powerful; a small number of people held large estates called ''

latifundia

A ''latifundium'' (Latin: ''latus'', "spacious" and ''fundus'', "farm, estate") is a very extensive parcel of privately owned land. The latifundia of Roman history were great landed estates specializing in agriculture destined for export: grain, o ...

'' as well as all of the important positions in government. In addition to these regime changes and hierarchies, there was a series of civil wars that transpired in Spain known as the

Carlist Wars

The Carlist Wars () were a series of civil wars that took place in Spain during the 19th century. The contenders fought over claims to the throne, although some political differences also existed. Several times during the period from 1833 to 18 ...

throughout the middle of the century. There were three such wars: the

First Carlist War

The First Carlist War was a civil war in Spain from 1833 to 1840, the first of three Carlist Wars. It was fought between two factions over the succession to the throne and the nature of the Spanish monarchy: the conservative and devolutionist ...

(1833–1840), the

Second Carlist War (1846–1849), and the

Third Carlist War (1872–1876). During these wars, a

right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

political movement known as

Carlism

Carlism ( eu, Karlismo; ca, Carlisme; ; ) is a Traditionalist and Legitimist political movement in Spain aimed at establishing an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French ...

fought to institute a monarchial dynasty under a different branch of the

House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spani ...

descended from

Don Infante Carlos María Isidro of Molina.

In 1868,

popular uprisings led to the overthrow of

Queen Isabella II of the

House of Bourbon

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spani ...

. Two distinct factors led to the uprisings: a series of urban riots and a liberal movement within the middle classes and the military (led by

General Joan Prim) concerned with the ultra-conservatism of the monarchy. In 1873, Isabella's replacement, King

Amadeo I of the

House of Savoy

The House of Savoy ( it, Casa Savoia) was a royal dynasty that was established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region. Through gradual expansion, the family grew in power from ruling a small Alpine county north-west of Italy to absolute rule of ...

, abdicated due to increasing political pressure, and the short-lived

First Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic ( es, República Española), historiographically referred to as the First Spanish Republic, was the political regime that existed in Spain from 11 February 1873 to 29 December 1874.

The Republic's founding ensued after th ...

was proclaimed. After the

restoration of the Bourbons in December 1874, Carlists and

anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

emerged in opposition to the monarchy.

Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

, Spanish politician and leader of the

Radical Republican Party, helped to bring

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

to the fore in

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the no ...

—a region of Spain with its own

cultural

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.T ...

and

societal identity in which

poverty

Poverty is the state of having few material possessions or little income. Poverty can have diverse was particularly acute at the time.

Conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to Ancient history, antiquity and it continues in some countries to th ...

was a controversial policy that was eventually implemented by the government of Spain. As evidenced by the

Tragic Week in 1909, resentment and resistance were factors that continued well into the 20th century.

Spain was neutral in World War I

Spain was neutral in World War I. Following the war, wide swathes of Spanish society, including the armed forces, united in hopes of removing the

corrupt

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

central government of the country in

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

, but these circles were ultimately unsuccessful. Popular perception of

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

as a major threat significantly increased during this period. In 1923, a military

coup brought

Miguel Primo de Rivera

Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquess of Estella (8 January 1870 – 16 March 1930), was a dictator, aristocrat, and military officer who served as Prime Minister of Spain from 1923 to 1930 during Spain's Restoration era. He deepl ...

to power. As a result, Spain transitioned to government by military dictatorship. Support for the Rivera regime gradually faded, and he resigned in January 1930. He was replaced by General

Dámaso Berenguer

Dámaso Berenguer y Fusté, 1st Count of Xauen (4 August 1873 – 19 May 1953) was a Spanish general and politician. He served as Prime Minister of Spain, Prime Minister during the last thirteen months of the reign of Alfonso XIII.

Biography

...

, who was in turn himself replaced by

Admiral Juan Bautista Aznar-Cabañas; both men continued a policy of

rule by decree

Rule by decree is a style of governance allowing quick, unchallenged promulgation of law by a single person or group. It allows the ruler to make or change laws without legislative approval. While intended to allow rapid responses to a crisis, rule ...

. There was little support for the monarchy in the major cities. Consequently, much like Amadeo I nearly sixty years earlier,

King Alfonso XIII

Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941), also known as El Africano or the African, was King of Spain from 17 May 1886 to 14 April 1931, when the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. He was a monarch from birth as his father, Alf ...

of Spain relented to popular pressure for the establishment of a

republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

in 1931 and called municipal elections for 12 April of that year.

Left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

entities such as the

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

and liberal republicans won almost all the provincial capitals and, following the resignation of Aznar's government, Alfonso XIII fled the country. At this time, the

Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 ...

was formed. This republic remained in power until the culmination of the civil war five years later.

The revolutionary committee headed by

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres (6 July 1877 – 18 February 1949) was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

Early life

...

became the provisional government, with Alcalá-Zamora himself as

president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

and

head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

. The republic had broad support from all segments of society. In May, an incident where a taxi driver was attacked outside a monarchist club sparked anti-clerical violence throughout

Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

and south-west portion of the country. The slow response on the part of the government disillusioned the right and reinforced their view that the

Republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

was determined to persecute the church. In June and July, the

Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo ( en, National Confederation of Labor; CNT) is a Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions, which was long affiliated with the International Workers' Association (AIT). When working ...

(CNT) called several

strikes, which led to a violent incident between CNT members and the

Civil Guard

Civil Guard refers to various policing organisations:

Current

* Civil Guard (Spain), Spanish gendarmerie

* Civil Guard (Israel), Israeli volunteer police reserve

* Civil Guard (Brazil), Municipal law enforcement corporations in Brazil

Historic ...

and a brutal crackdown by the Civil Guard and the

army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

against the CNT in

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

. This led many workers to believe the Spanish Second Republic was just as oppressive as the monarchy, and the CNT announced its intention of overthrowing it via

revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

. Elections in June 1931 returned a large majority of Republicans and Socialists. With the onset of the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, the government tried to assist rural Spain by instituting an

eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

and redistributing

land tenure

In common law systems, land tenure, from the French verb "tenir" means "to hold", is the legal regime in which land owned by an individual is possessed by someone else who is said to "hold" the land, based on an agreement between both individual ...

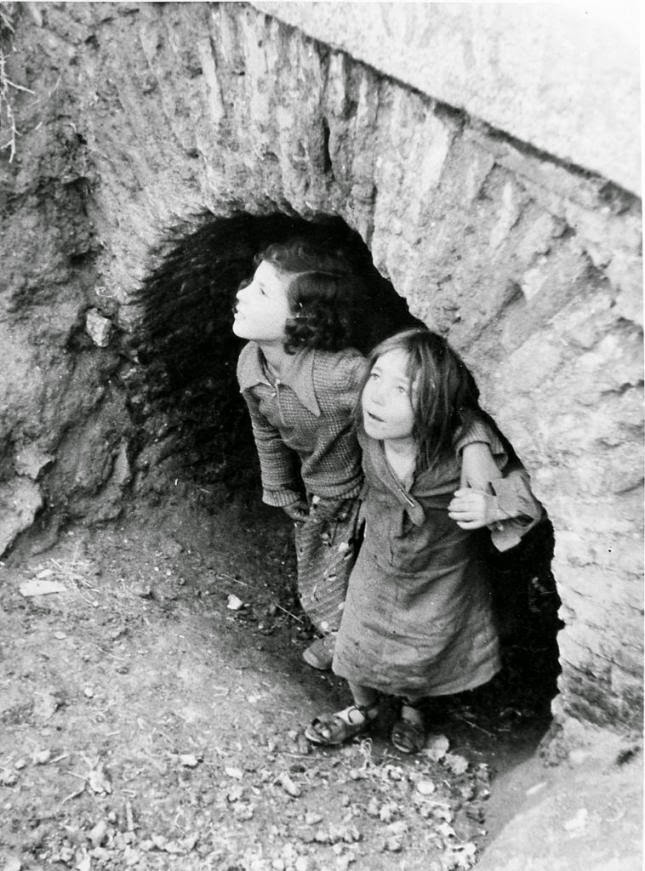

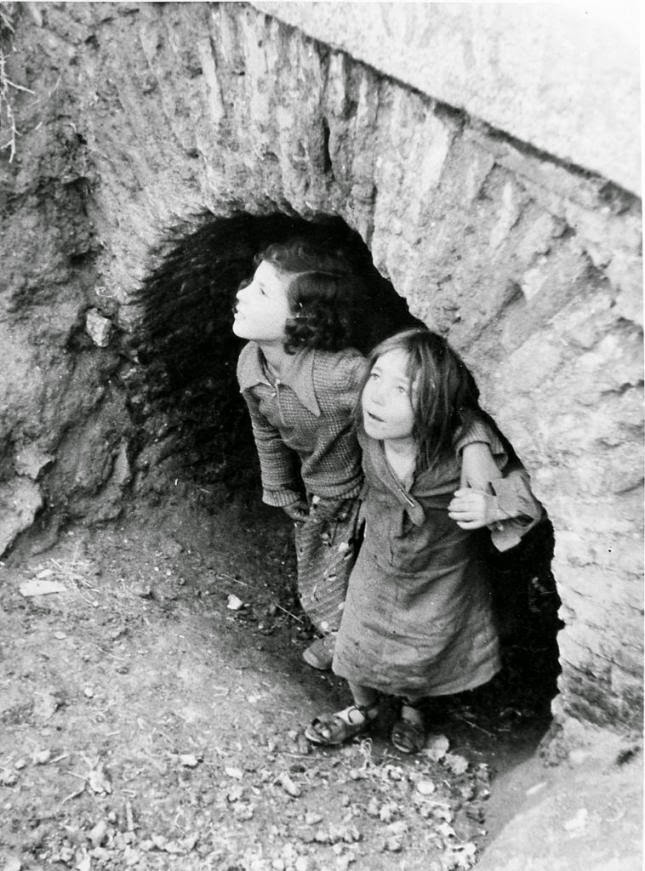

to farm workers. The rural workers lived in some of the worst poverty in Europe at the time and the government tried to increase their wages and improve working conditions. This estranged small and medium landholders who used hired labour. The Law of Municipal Boundaries forbade the hiring of workers from outside the locality of the owner's holdings. Since not all localities had enough labour for the tasks required, the law had unintended negative consequences, such as sometimes shutting out peasants and renters from the labour market when they needed extra income as pickers. Labour arbitration boards were set up to regulate salaries, contracts and working hours; they were more favourable to workers than employers and thus the latter became hostile to them. A decree in July 1931 increased overtime pay and several laws in late 1931 restricted whom landowners could hire. Other efforts included decrees limiting the use of machinery, efforts to create a monopoly on hiring, strikes and efforts by unions to limit women's employment to preserve a labour monopoly for their members. Class struggle intensified as landowners turned to counterrevolutionary organisations and local oligarchs. Strikes, workplace theft, arson, robbery and assaults on shops, strikebreakers, employers and machines became increasingly common. Ultimately, the reforms of the Republican-Socialist government alienated as many people as they pleased.

Republican

Manuel Azaña Diaz became prime minister of a minority government in October 1931.

Fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and t ...

remained a reactive threat and it was facilitated by controversial reforms to the military. In December, a new reformist, liberal, and democratic

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

was declared. It included strong provisions enforcing a broad

secularisation

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses the ...

of the Catholic country, which included the abolishing of Catholic schools and charities, which many moderate committed Catholics opposed. At this point once the constituent assembly had fulfilled its mandate of approving a new constitution, it should have arranged for regular parliamentary elections and adjourned. However fearing the increasing popular opposition, the Radical and Socialist majority postponed the regular elections, prolonging their time in power for two more years. Diaz's republican government initiated numerous reforms to, in their view, modernize the country. In 1932, the Jesuits who were in charge of the best schools throughout the country were banned and had all their property confiscated. The army was reduced. Landowners were expropriated. Home rule was granted to Catalonia, with a local parliament and a president of its own. In June 1933, Pope Pius XI issued the encyclical

Dilectissima Nobis, "On Oppression of the Church of Spain", raising his voice against the persecution of the Catholic Church in Spain.

In November 1933, the right-wing parties won the

general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

.

[Casanova (2010), p. 90.] The causal factors were increased resentment of the incumbent government caused by a controversial decree implementing land reform and by the

Casas Viejas incident The Casas Viejas incident, also known as the Casas Viejas massacre, took place in 1933 in the village of Casas Viejas, in Cádiz Province, Andalusia.

Background

The anarchist movement spread across Spain in the late 19th and early 20th centur ...

, and the formation of a right-wing alliance,

Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing Groups

The Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas (, CEDA), was a Spanish political party in the Second Spanish Republic. A Catholic conservative force, it was the political heir to Ángel Herrera Oria's Acción Popular and defined itself in ...

(CEDA). Another factor was the recent enfranchisement of women, most of whom voted for centre-right parties. The left Republicans attempted to have

Niceto Alcalá Zamora cancel the electoral results but did not succeed. Despite CEDA's electoral victory, president

Alcalá-Zamora declined to invite its leader, Gil Robles, to form a government fearing CEDA's monarchist sympathies and proposed changes to the constitution. Instead, he invited the

Radical Republican Party's

Alejandro Lerroux

Alejandro Lerroux García (4 March 1864, in La Rambla, Córdoba – 25 June 1949, in Madrid) was a Spanish politician who was the leader of the Radical Republican Party. He served as Prime Minister three times from 1933 to 1935 and held severa ...

to do so. Despite receiving the most votes, CEDA was denied cabinet positions for nearly a year.

Events in the period after November 1933, called the "

black biennium", seemed to make a civil war more likely. Alejandro Lerroux of the Radical Republican Party (RRP) formed a government, reversing changes made by the previous administration and granting amnesty to the collaborators of the unsuccessful uprising by General

José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936), was a Spanish general, one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' which started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title of "Marquis o ...

in August 1932. Some monarchists joined with the then fascist-nationalist

Falange Española y de las JONS ("Falange") to help achieve their aims. Open violence occurred in the streets of Spanish cities, and militancy continued to increase, reflecting a movement towards radical upheaval, rather than peaceful democratic means as solutions. A small insurrection by anarchists occurred in December 1933 in response to CEDA's victory, in which around 100 people died. After a year of intense pressure, CEDA, the party with the most seats in parliament, finally succeeded in forcing the acceptance of three ministries. The Socialists (PSOE) and Communists reacted with an insurrection for which they had been preparing for nine months. The rebellion developed into a bloody

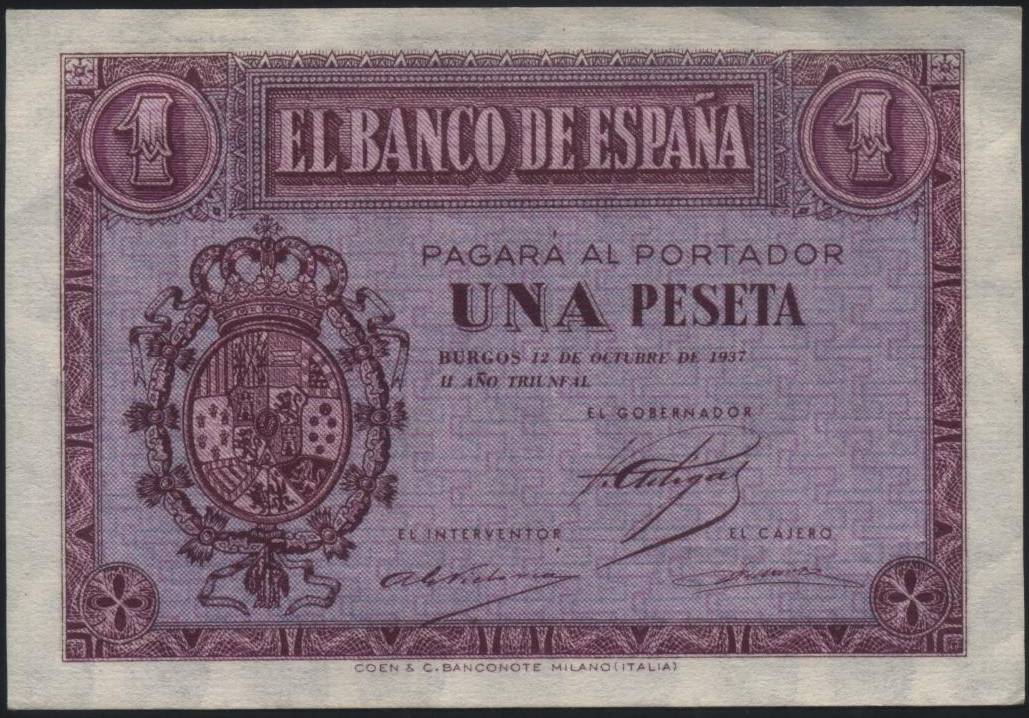

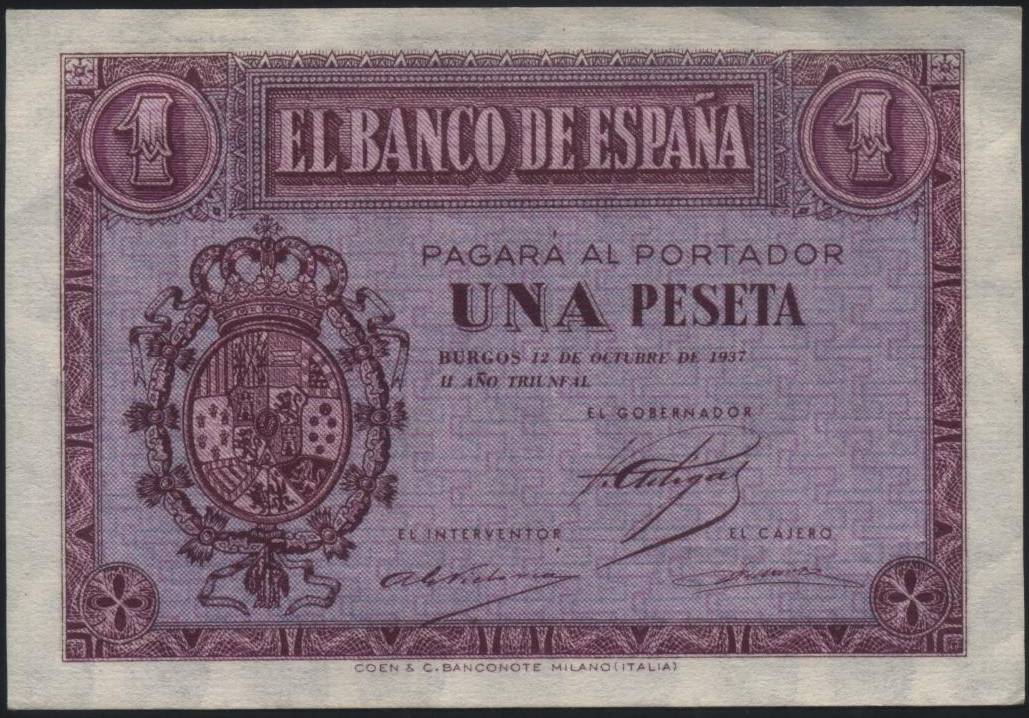

revolutionary uprising, against the existing order. Fairly well armed revolutionaries managed to take the whole province of Asturias, murdered numerous policemen, clergymen, and civilians, and destroyed religious buildings including churches, convents, and part of the university at Oviedo. Rebels in the occupied areas proclaimed revolution for the workers and abolished existing currency. The rebellion was crushed in two weeks by the

Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

and the

Spanish Republican Army

The Spanish Republican Army ( es, Ejército de la República Española) was the main branch of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic between 1931 and 1939.

It became known as People's Army of the Republic (''Ejército Popular de la Rep� ...

, the latter using mainly

Moorish

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or s ...

colonial troops

Colonial troops or colonial army refers to various military units recruited from, or used as garrison troops in, colonial territories.

Colonial background

Such colonies may lie overseas or in areas dominated by neighbouring land powers such ...

from

Spanish Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

. Azaña was in Barcelona that day, and the Lerroux-CEDA government tried to implicate him. He was arrested and charged with complicity. In fact, Azaña had no connection with the rebellion and was released from prison in January 1935.

In sparking an uprising, the non-anarchist socialists, like the anarchists, manifested their conviction that the existing political order was illegitimate. The Spanish historian

Salvador de Madariaga

Salvador de Madariaga y Rojo (23 July 1886 – 14 December 1978) was a Spanish diplomat, writer, historian, and pacifist. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and the Nobel Peace Prize. He was awarded the Charlemagne Prize in ...

, an Azaña supporter and an exiled vocal opponent of Francisco Franco, wrote a sharp criticism of the left's participation in the revolt: "The uprising of 1934 is unforgivable. The argument that Mr Gil Robles tried to destroy the Constitution to establish fascism was, at once, hypocritical and false. With the rebellion of 1934, the Spanish left lost even the shadow of moral authority to condemn the rebellion of 1936."

Reversals of land reform resulted in expulsions, firings, and arbitrary changes to working conditions in the central and southern countryside in 1935, with landowners' behaviour at times reaching "genuine cruelty", with violence against farmworkers and socialists, which caused several deaths. One historian argued that the behaviour of the right in the southern countryside was one of the main causes of hatred during the Civil War and possibly even the Civil War itself. Landowners taunted workers by saying that if they went hungry, they should "Go eat the Republic!" Bosses fired leftist workers and imprisoned trade union and socialist militants, and wages were reduced to "salaries of hunger".

In 1935, the government led by the

Radical Republican Party went through a series of crises. President

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora

Niceto Alcalá-Zamora y Torres (6 July 1877 – 18 February 1949) was a Spanish lawyer and politician who served, briefly, as the first prime minister of the Second Spanish Republic, and then—from 1931 to 1936—as its president.

Early life

...

, who was hostile to this government, called another election. The

Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

narrowly won the

1936 general election. The revolutionary left-wing masses took to the streets and freed prisoners. In the thirty-six hours following the election, sixteen people were killed (mostly by police officers attempting to maintain order or to intervene in violent clashes) and thirty-nine were seriously injured. Also, fifty churches and seventy conservative political centres were attacked or set ablaze.

Manuel Azaña Díaz was called to form a government before the electoral process had ended. He shortly replaced Zamora as president, taking advantage of a constitutional loophole. Convinced that the left was no longer willing to follow the rule of law and that its vision of Spain was under threat, the right abandoned the parliamentary option and began planning to overthrow the republic, rather than to control it.

PSOE's left wing socialists started to take action.

Julio Álvarez del Vayo

Julio Álvarez del Vayo (1890 in Villaviciosa de Odón, Community of Madrid – 3 May 1975 in Geneva, Switzerland) was a Spanish Socialist politician, journalist and writer.

Biography

Álvarez studied Law at the Universities of Madrid and Vall ...

talked about "Spain' being converted into a socialist Republic in association with the Soviet Union".

Francisco Largo Caballero declared that "the organized proletariat will carry everything before it and destroy everything until we reach our goal". The country rapidly descended into anarchy. Even the staunch socialist

Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

, at a party rally in Cuenca in May 1936, complained: "we have never seen so tragic a panorama or so great a collapse as in Spain at this moment. Abroad, Spain is classified as insolvent. This is not the road to socialism or communism but to desperate anarchism without even the advantage of liberty". The disenchantment with Azaña's ruling was also voiced by

Miguel de Unamuno

Miguel de Unamuno y Jugo (29 September 1864 – 31 December 1936) was a Spanish essayist, novelist, poet, playwright, philosopher, professor of Greek and Classics, and later rector at the University of Salamanca.

His major philosophical essa ...

, a republican and one of Spain's most respected intellectuals who, in June 1936, told a reporter who published his statement in El Adelanto that President

Manuel Azaña

Manuel Azaña Díaz (; 10 January 1880 – 3 November 1940) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister of the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1933 and 1936), organizer of the Popular Front in 1935 and the last President of the Re ...

should commit suicide "as a patriotic act".

According to Stanley Payne, by July 1936, the situation in Spain had deteriorated massively. Spanish commentators spoke of chaos and preparation for revolution, foreign diplomats prepared for the possibility of revolution, and an interest in fascism developed among the threatened. Payne states that, by July 1936:

Laia Balcells observes that polarisation in Spain just before the coup was so intense that physical confrontations between leftists and rightists were a routine occurrence in most localities; six days before the coup occurred, there was a riot between the two in the province of Teruel. Balcells notes that Spanish society was so divided along Left-Right lines that the monk Hilari Raguer stated that in his parish, instead of playing "cops and robbers", children would sometimes play "leftists and rightists". Within the first month of the Popular Front's government, nearly a quarter of the provincial governors had been removed due to their failure to prevent or control strikes, illegal land occupation, political violence and arson. The Popular Front government was more likely to persecute rightists for violence than leftists who committed similar acts. Azaña was hesitant to use the army to shoot or stop rioters or protestors as many of them supported his coalition. On the other hand, he was reluctant to disarm the military as he believed he needed them to stop insurrections from the extreme left. Illegal land occupation became widespread—poor tenant farmers knew the government was disinclined to stop them. By April 1936, nearly 100,000 peasants had appropriated 400,000 hectares of land and perhaps as many as 1 million hectares by the start of the civil war; for comparison, the 1931–33 land reform had granted only 6,000 peasants 45,000 hectares. As many strikes occurred between April and July as had occurred in the entirety of 1931. Workers increasingly demanded less work and more pay. "Social crimes"—refusing to pay for goods and rent—became increasingly common by workers, particularly in Madrid. In some cases this was done in the company of armed militants. Conservatives, the middle classes, businessmen and landowners became convinced that revolution had already begun.

Prime Minister

Santiago Casares Quiroga ignored warnings of a military conspiracy involving several generals, who decided that the government had to be replaced to prevent the dissolution of Spain. Both sides had become convinced that, if the other side gained power, it would discriminate against their members and attempt to suppress their political organisations.

Military coup

Backgrounds

Shortly after the Popular Front's victory in the 1936 election, various groups of officers, both active and retired, got together to begin discussing the prospect of a coup. It would only be by the end of April that General Emilio Mola would emerge as the leader of a national conspiracy network. The Republican government acted to remove suspect generals from influential posts. Franco was sacked as chief of staff and transferred to command of the

Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

.

Manuel Goded Llopis

Manuel Goded Llopis (15 October 1882 – 12 August 1936) was a Spanish Army general who was one of the key figures in the July 1936 revolt against the democratically elected Second Spanish Republic. Having unsuccessfully led an attempted insur ...

was removed as

inspector general

An inspector general is an investigative official in a civil or military organization. The plural of the term is "inspectors general".

Australia

The Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (Australia) (IGIS) is an independent statutory of ...

and was made general of the

Balearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

.

Emilio Mola was moved from head of the

Army of Africa to military commander of

Pamplona

Pamplona (; eu, Iruña or ), historically also known as Pampeluna in English, is the capital city of the Chartered Community of Navarre, in Spain. It is also the third-largest city in the greater Basque cultural region.

Lying at near above ...

in

Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

. This, however, allowed Mola to direct the mainland uprising. General

José Sanjurjo

José Sanjurjo y Sacanell (; 28 March 1872 – 20 July 1936), was a Spanish general, one of the military leaders who plotted the July 1936 ''coup d'état'' which started the Spanish Civil War.

He was endowed the nobiliary title of "Marquis o ...

became the figurehead of the operation and helped reach an agreement with the Carlists. Mola was chief planner and second in command.

José Antonio Primo de Rivera

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Sáenz de Heredia, 1st Duke of Primo de Rivera, 3rd Marquess of Estella (24 April 1903 – 20 November 1936), often referred to simply as José Antonio, was a Spanish politician who founded the falangist Falang ...

was put in prison in mid-March in order to restrict the Falange. However, government actions were not as thorough as they might have been, and warnings by the Director of Security and other figures were not acted upon.

The revolt was devoid of any particular ideology. The major goal was to put an end to anarchical disorder. Mola's plan for the new regime was envisioned as a "republican dictatorship", modelled after

Salazar's Portugal and as a semi-pluralist authoritarian regime rather than a totalitarian fascist dictatorship. The initial government would be an all-military "Directory", which would create a "strong and disciplined state". General Sanjurjo would be the head of this new regime, due to being widely liked and respected within the military, though his position would be largely symbolic due to his lack of political talent. The 1931 Constitution would be suspended, replaced by a new "constituent parliament" which would be chosen by a new politically purged electorate, who would vote on the issue of republic versus monarchy. Certain liberal elements would remain, such as separation of church and state as well as freedom of religion. Agrarian issues would be solved by regional commissioners on the basis of smallholdings but collective cultivation would be permitted in some circumstances. Legislation prior to February 1936 would be respected. Violence would be required to destroy opposition to the coup, though it seems Mola did not envision the mass atrocities and repression that would ultimately manifest during the civil war. Of particular importance to Mola was ensuring the revolt was at its core an Army affair, one that would not be subject to special interests and that the coup would make the armed forces the basis for the new state. However, the separation of church and state was forgotten once the conflict assumed the dimension of a war of religion, and military authorities increasingly deferred to the Church and to the expression of Catholic sentiment. However, Mola's program was vague and only a rough sketch, and there were disagreements among coupists about their vision for Spain.

On 12 June,

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Casares Quiroga met General

Juan Yagüe

Juan Yagüe y Blanco, 1st Marquis of San Leonardo de Yagüe (19 November 1891 – 21 October 1952) was a Spanish military officer during the Spanish Civil War, one of the most important in the Nationalist side. He became known as the "Butcher of ...

, who falsely convinced Casares of his loyalty to the republic. Mola began serious planning in the spring. Franco was a key player because of his prestige as a former director of the military academy and as the man who suppressed the

Asturian miners' strike of 1934

The Asturian miners' strike of 1934 was a major strike action undertaken by regional miners against the 1933 Spanish general election, which redistributed political power from the leftists to conservatives in the Second Spanish Republic. The s ...

. He was respected in the Army of Africa, the Army's toughest troops. He wrote a cryptic letter to Casares on 23 June, suggesting that the military was disloyal, but could be restrained if he were put in charge. Casares did nothing, failing to arrest or buy off Franco. With the help of the

British intelligence

The Government of the United Kingdom maintains intelligence agencies within three government departments, the Foreign Office, the Home Office and the Ministry of Defence. These agencies are responsible for collecting and analysing foreign and d ...

agents

Cecil Bebb

Captain Cecil William Henry Bebb (27 September 1905 – 29 March 2002) was a British commercial pilot and later airline executive, notable for flying General Francisco Franco from the Canary Islands to Spanish Morocco in 1936, a journey which w ...

and

Hugh Pollard, the rebels chartered a

Dragon Rapide aircraft (paid for with help from

Juan March, the wealthiest man in Spain at the time) to transport Franco from the Canary Islands to

Spanish Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

. The plane flew to the Canaries on 11 July, and Franco arrived in Morocco on 19 July. According to Stanley Payne, Franco was offered this position as Mola's planning for the coup had become increasingly complex and it did not look like it would be as swift as he hoped, instead likely turning into a miniature civil war that would last several weeks. Mola thus had concluded that the troops in Spain were insufficient for the task and that it would be necessary to use elite units from North Africa, something which Franco had always believed would be necessary.

On 12 July 1936, Falangists in Madrid killed police officer

Lieutenant José Castillo of the

Guardia de Asalto (Assault Guard). Castillo was a Socialist party member who, among other activities, was giving military training to the UGT youth. Castillo had led the Assault Guards that violently suppressed the riots after the funeral of ''Guardia Civil'' lieutenant Anastasio de los Reyes. (Los Reyes had been shot by anarchists during 14 April military parade commemorating the five years of the Republic.)

Assault Guard Captain Fernando Condés was a close personal friend of Castillo. The next day, after getting the approval of the minister of interior to illegally arrest specified members of parliament, he led his squad to arrest

José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones

José María Gil-Robles y Quiñones de León (Salamanca, 27 November 1898 – Madrid, 13 September 1980) was a Spanish politician, leader of the CEDA and a prominent figure in the period leading up to the Spanish Civil War. He served as Mi ...

, founder of CEDA, as a reprisal for Castillo's murder. But he was not at home, so they went to the house of

José Calvo Sotelo, a leading Spanish

monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalis ...

and a prominent parliamentary conservative. Luis Cuenca, a member of the arresting group and a Socialist who was known as the bodyguard of

PSOE

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party ( es, Partido Socialista Obrero Español ; PSOE ) is a social-democraticThe PSOE is described as a social-democratic party by numerous sources:

*

*

*

* political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in gov ...

leader

Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

,

summarily executed

A summary execution is an execution in which a person is accused of a crime and immediately killed without the benefit of a full and fair trial. Executions as the result of summary justice (such as a drumhead court-martial) are sometimes include ...

Calvo Sotelo by shooting him in the back of the neck.

Hugh Thomas concludes that Condés intended to arrest Sotelo, and that Cuenca acted on his own initiative, although he acknowledges other sources dispute this finding.

Massive reprisals followed.

The killing of Calvo Sotelo with police involvement aroused suspicions and strong reactions among the government's opponents on the right. Although the nationalist generals were already planning an uprising, the event was a catalyst and a public justification for a coup.

Stanley Payne claims that before these events, the idea of rebellion by army officers against the government had weakened; Mola had estimated that only 12% of officers reliably supported the coup and at one point considered fleeing the country for fear he was already compromised, and had to be convinced to remain by his co-conspirators. However, the kidnapping and murder of Sotelo transformed the "limping conspiracy" into a revolt that could trigger a civil war.

[Esdaile, Charles J. The Spanish Civil War: A Military History. Routledge, 2018.] The arbitrary use of lethal force by the state and a lack of action against the attackers led to public disapproval of the government. No effective punitive, judicial or even investigative action was taken; Payne points to a possible veto by socialists within the government who shielded the killers who had been drawn from their ranks. The murder of a parliamentary leader by state police was unprecedented, and the belief that the state had ceased to be neutral and effective in its duties encouraged important sectors of the right to join the rebellion. Within hours of learning of the murder and the reaction,

Franco changed his mind on rebellion and dispatched a message to

Mola to display his firm commitment.

The Socialists and Communists, led by

Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

, demanded that arms be distributed to the people before the military took over. The prime minister was hesitant.

Beginning of the coup

The uprising's timing was fixed at 17 July, at 17:01, agreed to by the leader of the Carlists,

Manuel Fal Conde

Manuel Fal Conde, 1st Duke of Quintillo (1894–1975) was a Spanish Catholic activist and a Carlist politician. He is recognized as a leading figure in the history of Carlism, serving as its political leader for over 20 years (1934–1955) and h ...

. However, the timing was changed—the men in the

Morocco protectorate were to rise up at 05:00 on 18 July and those in Spain proper a day later so that control of Spanish Morocco could be achieved and forces sent back to the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

to coincide with the risings there. The rising was intended to be a swift coup d'état, but the government retained control of most of the country.

Control over Spanish Morocco was all but certain. The plan was discovered in Morocco on 17 July, which prompted the conspirators to enact it immediately. Little resistance was encountered. The rebels shot 189 people. Goded and Franco immediately took control of the islands to which they were assigned. On 18 July, Casares Quiroga refused an offer of help from the CNT and

Unión General de Trabajadores

The Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT, General Union of Workers) is a major Spanish trade union, historically affiliated with the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE).

History

The UGT was founded 12 August 1888 by Pablo Iglesias Posse ...

(UGT), leading the groups to proclaim a general strike—in effect, mobilising. They opened weapons caches, some buried since the 1934 risings, and formed militias. The paramilitary security forces often waited for the outcome of militia action before either joining or suppressing the rebellion. Quick action by either the rebels or

anarchist militias was often enough to decide the fate of a town. General

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano

Gonzalo Queipo de Llano y Sierra (5 February 1875 – 9 March 1951) was a Spanish military leader who rose to prominence during the July 1936 coup and then the Spanish Civil War and the White Terror.

Biography

A career army man, Queipo de Lla ...

secured Seville for the rebels, arresting a number of other officers.

Outcome

The rebels failed to take any major cities with the critical exception of

Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Penins ...

, which provided a landing point for Franco's African troops, and the primarily conservative and Catholic areas of

Old Castile

Old Castile ( es, Castilla la Vieja ) is a historic region of Spain, which had different definitions along the centuries. Its extension was formally defined in the 1833 territorial division of Spain as the sum of the following provinces: Sant ...

and

León, which fell quickly. They took

Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

with help from the first troops from Africa.

The government retained control of

Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most po ...

,

Jaén, and

Almería

Almería (, , ) is a city and municipality of Spain, located in Andalusia. It is the capital of the province of the same name. It lies on southeastern Iberia on the Mediterranean Sea. Caliph Abd al-Rahman III founded the city in 955. The city g ...

. In Madrid, the rebels were hemmed into the

Cuartel de la Montaña siege, which fell with considerable bloodshed. Republican leader Casares Quiroga was replaced by

José Giral

José Giral y Pereira (22 October 1879 – 23 December 1962) was a Spanish people, Spanish politician, who served as the 75th Prime Minister of Spain during the Second Spanish Republic.

Life

Giral was born in Santiago de Cuba. He had degree ...

, who ordered the distribution of weapons among the civilian population. This facilitated the defeat of the army insurrection in the main industrial centres, including Madrid,

Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

, and

Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

, but it allowed anarchists to take control of Barcelona along with large swathes of

Aragón

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises th ...

and Catalonia. General Goded surrendered in Barcelona and was later condemned to death. The Republican government ended up controlling almost all the east coast and central area around Madrid, as well as most of

Asturias

Asturias (, ; ast, Asturies ), officially the Principality of Asturias ( es, Principado de Asturias; ast, Principáu d'Asturies; Galician-Asturian: ''Principao d'Asturias''), is an autonomous community in northwest Spain.

It is coextensiv ...

,

Cantabria

Cantabria (, also , , Cantabrian: ) is an autonomous community in northern Spain with Santander as its capital city. It is called a ''comunidad histórica'', a historic community, in its current Statute of Autonomy. It is bordered on the east ...

and part of the

Basque Country in the north.

Hugh Thomas suggested that the civil war could have ended in the favour of either side almost immediately if certain decisions had been taken during the initial coup. Thomas argues that if the government had taken steps to arm the workers, they could probably have crushed the coup very quickly. Conversely, if the coup had risen everywhere in Spain on the 18th rather than be delayed, it could have triumphed by the 22nd. While the militias that rose to meet the rebels were often untrained and poorly armed (possessing only a small number of pistols, shotguns and dynamite), this was offset by the fact that the rebellion was not universal. In addition, the Falangists and Carlists were themselves often not particularly powerful fighters either. However, enough officers and soldiers had joined the coup to prevent it from being crushed swiftly.

The rebels termed themselves ''Nacionales'', normally translated "Nationalists", although the former implies "true Spaniards" rather than a

nationalistic cause. The result of the coup was a nationalist area of control containing 11 million of Spain's population of 25 million. The Nationalists had secured the support of around half of Spain's territorial army, some 60,000 men, joined by the Army of Africa, made up of 35,000 men, and just under half of Spain's militaristic police forces, the Assault Guards, the

Civil Guards, and the

Carabineers. Republicans controlled under half of the rifles and about a third of both machine guns and artillery pieces.

The Spanish Republican Army had just 18 tanks of a sufficiently modern design, and the Nationalists took control of 10. Naval capacity was uneven, with the Republicans retaining a numerical advantage, but with the Navy's top commanders and two of the most modern ships, heavy cruisers ''

Canarias Canarias may refer to:

* The Spanish Canary Islands (Spanish: ''Islas Canarias'')

** Roman Catholic Diocese of Canarias

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Canarias or Diocese Canariense-Rubicense ( la, Canarien(sis)) is a diocese located in the Cana ...

''—captured at the

Ferrol shipyard—and ''

Baleares'', in Nationalist control. The

Spanish Republican Navy

The Spanish Republican Navy was the naval arm of the Armed Forces of the Second Spanish Republic, the legally established government of Spain between 1931 and 1939.

History

In the same manner as the other two branches of the Spanish Republ ...

suffered from the same problems as the army—many officers had defected or been killed after trying to do so. Two-thirds of air capability was retained by the government—however, the whole of the

Republican Air Force was very outdated.

Combatants

The war was cast by Republican sympathisers as a struggle between tyranny and freedom, and by Nationalist supporters as

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

and

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

red hordes versus Christian civilisation. Nationalists also claimed they were bringing security and direction to an ungoverned and lawless country. Spanish politics, especially on the left, was quite fragmented: on the one hand socialists and communists supported the republic but on the other, during the republic, anarchists had mixed opinions, though both major groups opposed the Nationalists during the Civil War; the latter, in contrast, were united by their fervent opposition to the Republican government and presented a more unified front.

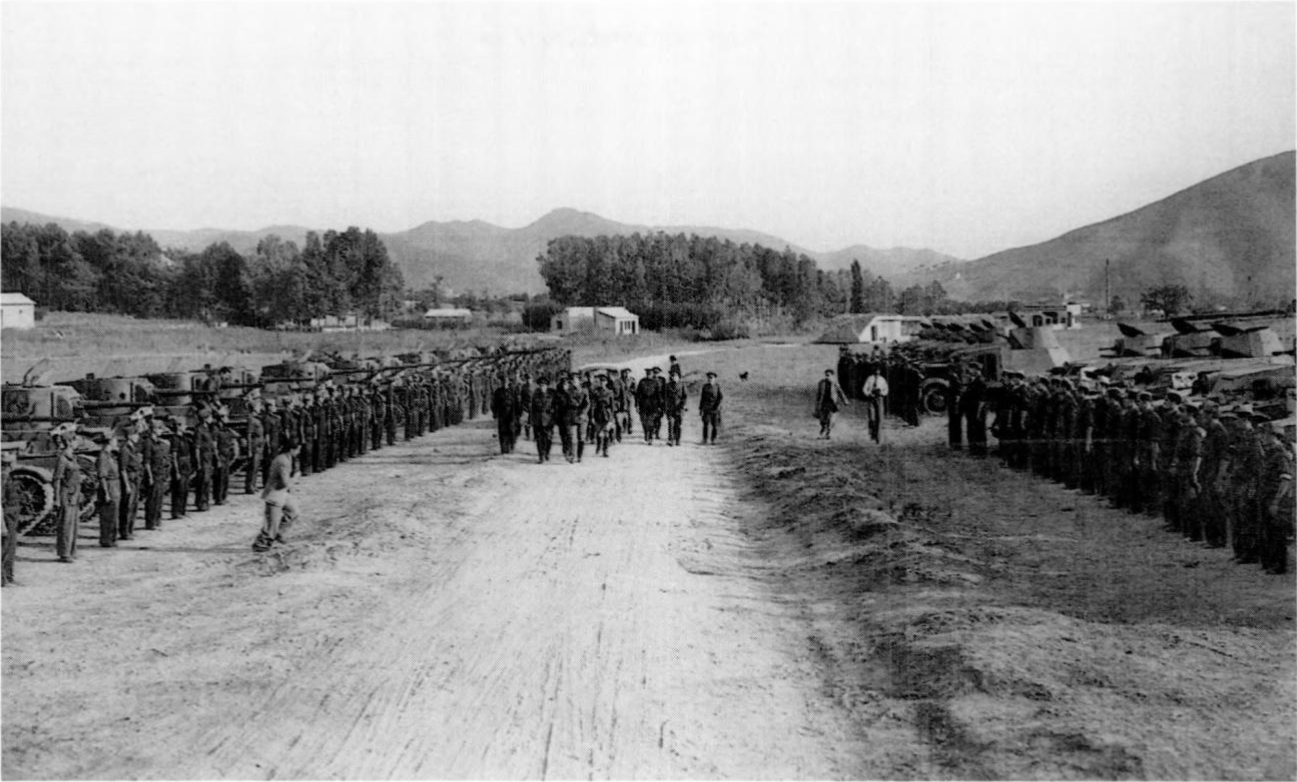

The coup divided the armed forces fairly evenly. One historical estimate suggests that there were some 87,000 troops loyal to the government and some 77,000 joining the insurgency,

[Payne, Stanley G. (1970), ''The Spanish Revolution'', , p. 315] though some historians suggest that the Nationalist figure should be revised upwards and that it probably amounted to some 95,000.

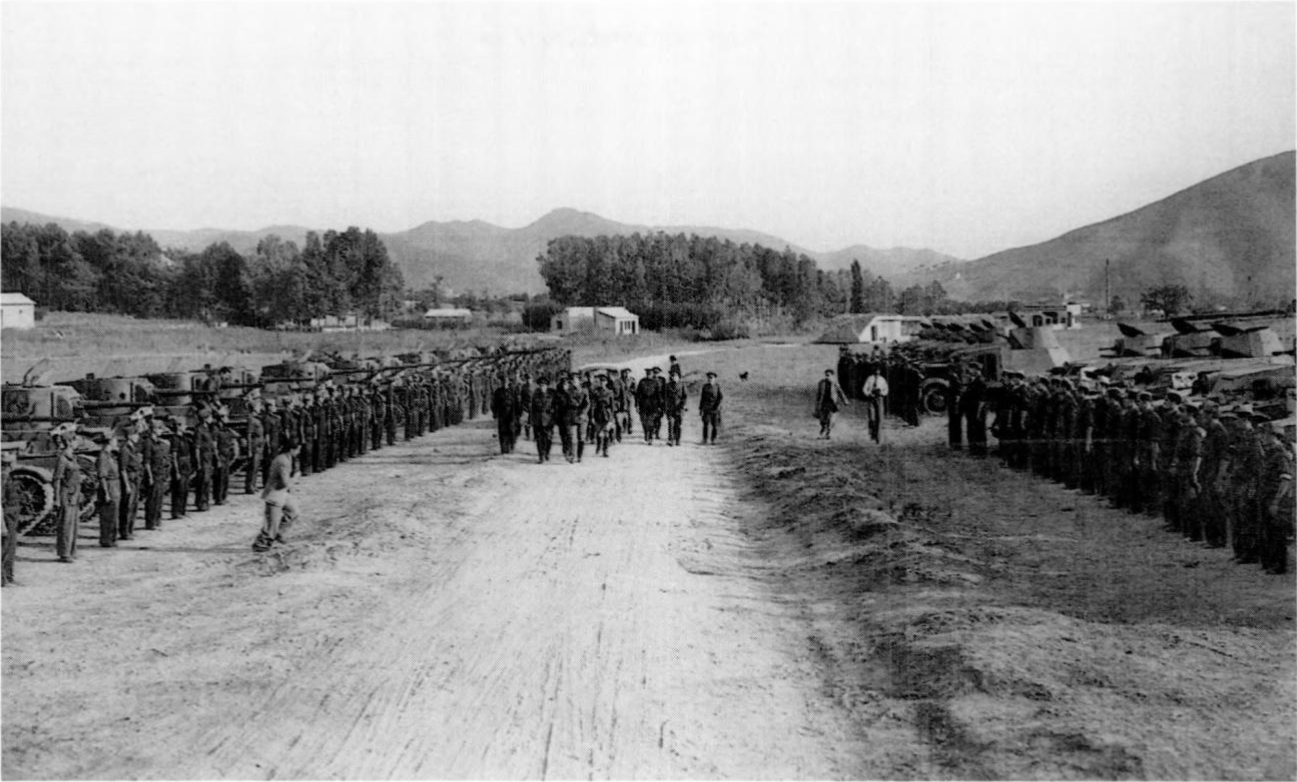

During the first few months, both armies were joined in high numbers by volunteers, Nationalists by some 100,000 men and Republicans by some 120,000. From August, both sides launched their own, similarly scaled conscription schemes, resulting in further massive growth of their armies. Finally, the final months of 1936 saw the arrival of foreign troops, International Brigades joining the Republicans and Italian CTV, German Legion Condor and Portuguese Viriatos joining the Nationalists. The result was that in April 1937 there were some 360,000 soldiers in the Republican ranks and some 290,000 in the Nationalist ones.

The armies kept growing. The principal source of manpower was conscription; both sides continued and expanded their schemes, the Nationalists drafting more aggressively, and there was little room left for volunteering. Foreigners contributed little to further growth; on the Nationalist side the Italians scaled down their engagement, while on the Republican side the influx of new ''interbrigadistas'' did not cover losses on the front. At the turn of 1937–1938, each army numbered about 700,000.

Throughout 1938, the principal if not exclusive source of new men was a draft; at this stage it was the Republicans who conscripted more aggressively, and only 47% of their combatants were in age corresponding to the Nationalist conscription age limits. Just prior to the Battle of Ebro, Republicans achieved their all-time high, slightly above 800,000; yet Nationalists numbered 880,000. The Battle of Ebro, fall of Catalonia and collapsing discipline caused a great shrinking of Republican troops. In late February 1939, their army was 400,000 compared to more than double that number of Nationalists. In the moment of their final victory, Nationalists commanded over 900,000 troops.

The total number of Spaniards serving in the Republican forces was officially stated as 917,000; later scholarly work estimated the number as "well over 1 million men",

[Payne (1970), p. 343] though earlier studies claimed a Republican total of 1.75 million (including non-Spaniards). The total number of Spaniards serving in the Nationalist units is estimated at "nearly 1 million men",

though earlier works claimed a total of 1.26 million Nationalists (including non-Spaniards).

Republicans

Only two countries openly and fully supported the Republic: the Mexican government and the USSR. From them, especially the USSR, the Republic received diplomatic support, volunteers, weapons and vehicles. Other countries remained neutral; this neutrality faced serious opposition from sympathizers in the United States and United Kingdom, and to a lesser extent in other European countries and from

Marxists