Soviet Union in World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

/ref> Germany invaded

During the 1930s, Soviet foreign minister

During the 1930s, Soviet foreign minister

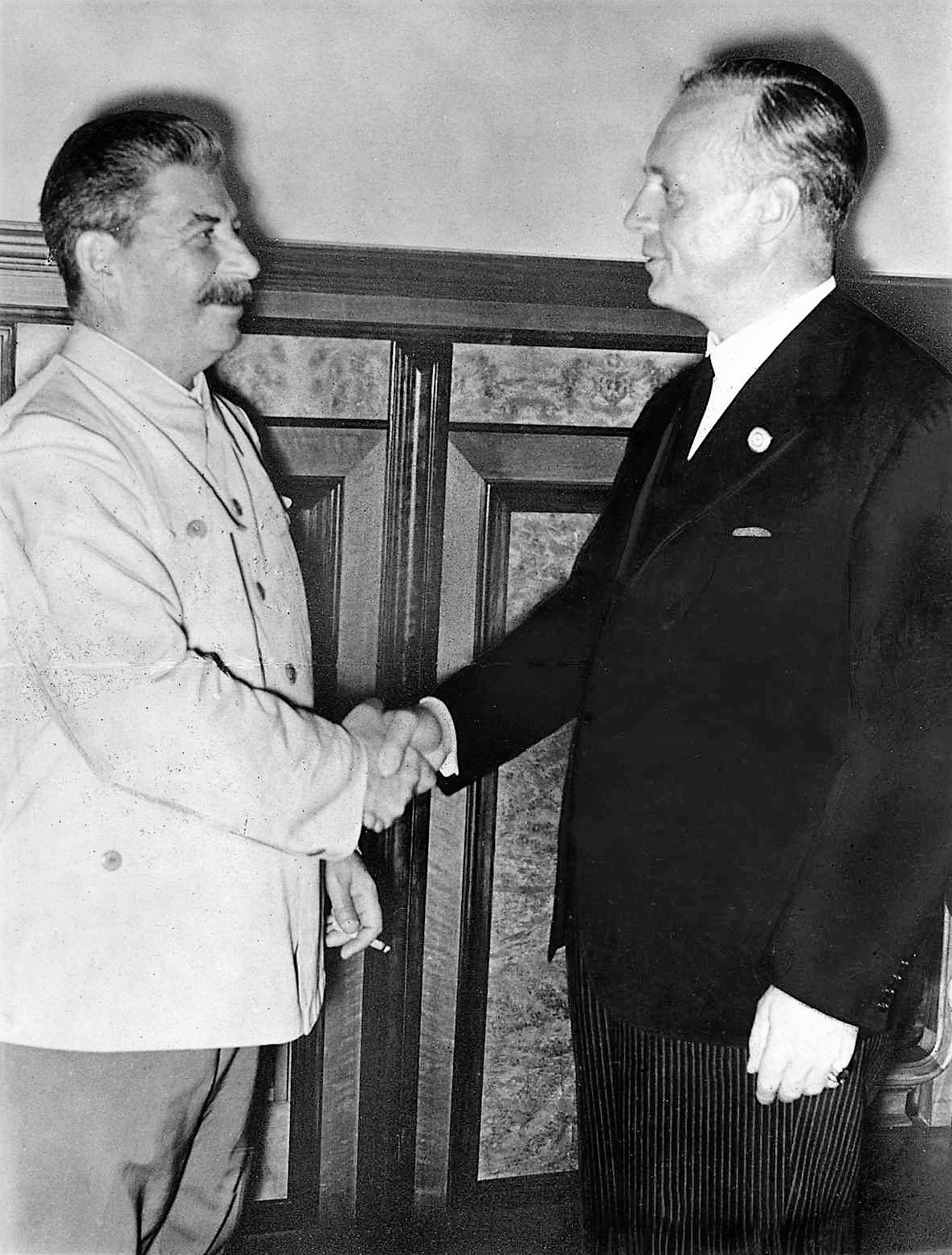

executed 23 August 1939 The USSR was promised the eastern part of After disagreement regarding Stalin's demand to move

After disagreement regarding Stalin's demand to move

On 1 September 1939, the German invasion of its agreed upon portion of Poland started the

On 1 September 1939, the German invasion of its agreed upon portion of Poland started the

After taking around 300,000 Polish prisoners in 1939 and early 1940,obozy jenieckie zolnierzy polskich

After taking around 300,000 Polish prisoners in 1939 and early 1940,obozy jenieckie zolnierzy polskich

(Prison camps for Polish soldiers) Encyklopedia PWN. Last accessed on 28 November 2006.Edukacja Humanistyczna w wojsku

. 1/2005. Dom wydawniczy Wojska Polskiego. . (Official publication of the Polish Army) Молотов на V сессии Верховного Совета 31 октября цифра «примерно 250 тыс.» (Please provide translation of the reference title and publication data and means) Отчёт Украинского и Белорусского фронтов Красной Армии Мельтюхов, с. 367

(Please provide translation of the reference title and publication data and means)

The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field

, ''

Google Books, p. 20-24.

/ref> After the

After the

Seven days before the invasion, a Soviet spy in Berlin, part of the ''Rote Kapelle'' (Red Orchestra) spy network, warned Stalin that the movement of German divisions to the borders was to wage war on the Soviet Union. Five days before the attack, Stalin received a report from a spy in the German Air Ministry that "all preparations by Germany for an armed attack on the Soviet Union have been completed, and the blow can be expected at any time." In the margin, Stalin wrote to the people's commissar for state security, "you can send your 'source' from the headquarters of German aviation to his mother. This is not a 'source' but a ''dezinformator.''" Although Stalin increased Soviet western border forces to 2.7 million men and ordered them to expect a possible German invasion, he did not order a full-scale mobilisation of forces to prepare for an attack. Stalin felt that a mobilization might provoke Hitler to prematurely begin to wage war against the Soviet Union, which Stalin wanted to delay until 1942 in order to strengthen Soviet forces.

In the initial hours after the German attack began, Stalin hesitated, wanting to ensure that the German attack was sanctioned by Hitler, rather than the unauthorized action of a rogue general.Simon Sebag Montefiore. ''Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar'', Knopf, 2004 () Accounts by

Seven days before the invasion, a Soviet spy in Berlin, part of the ''Rote Kapelle'' (Red Orchestra) spy network, warned Stalin that the movement of German divisions to the borders was to wage war on the Soviet Union. Five days before the attack, Stalin received a report from a spy in the German Air Ministry that "all preparations by Germany for an armed attack on the Soviet Union have been completed, and the blow can be expected at any time." In the margin, Stalin wrote to the people's commissar for state security, "you can send your 'source' from the headquarters of German aviation to his mother. This is not a 'source' but a ''dezinformator.''" Although Stalin increased Soviet western border forces to 2.7 million men and ordered them to expect a possible German invasion, he did not order a full-scale mobilisation of forces to prepare for an attack. Stalin felt that a mobilization might provoke Hitler to prematurely begin to wage war against the Soviet Union, which Stalin wanted to delay until 1942 in order to strengthen Soviet forces.

In the initial hours after the German attack began, Stalin hesitated, wanting to ensure that the German attack was sanctioned by Hitler, rather than the unauthorized action of a rogue general.Simon Sebag Montefiore. ''Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar'', Knopf, 2004 () Accounts by  In the first three weeks of the invasion, as the Soviet Union tried to defend itself against large German advances, it suffered 750,000 casualties, and lost 10,000 tanks and 4,000 aircraft. In July 1941, Stalin completely reorganized the Soviet military, placing himself directly in charge of several military organizations. This gave him complete control of his country's entire war effort; more control than any other leader in World War II.

A pattern soon emerged where Stalin embraced the

In the first three weeks of the invasion, as the Soviet Union tried to defend itself against large German advances, it suffered 750,000 casualties, and lost 10,000 tanks and 4,000 aircraft. In July 1941, Stalin completely reorganized the Soviet military, placing himself directly in charge of several military organizations. This gave him complete control of his country's entire war effort; more control than any other leader in World War II.

A pattern soon emerged where Stalin embraced the

In early 1942, the Soviets began a series of offensives labelled "Stalin's First Strategic Offensives". The counteroffensive bogged down, in part due to mud from rain in the spring of 1942. Stalin's attempt to retake Kharkov in the Ukraine ended in the disastrous encirclement of Soviet forces, with over 200,000 Soviet casualties suffered. Stalin attacked the competence of the generals involved. General

In early 1942, the Soviets began a series of offensives labelled "Stalin's First Strategic Offensives". The counteroffensive bogged down, in part due to mud from rain in the spring of 1942. Stalin's attempt to retake Kharkov in the Ukraine ended in the disastrous encirclement of Soviet forces, with over 200,000 Soviet casualties suffered. Stalin attacked the competence of the generals involved. General  At the same time, Hitler was worried about American popular support after the U.S. entry into the war following the

At the same time, Hitler was worried about American popular support after the U.S. entry into the war following the

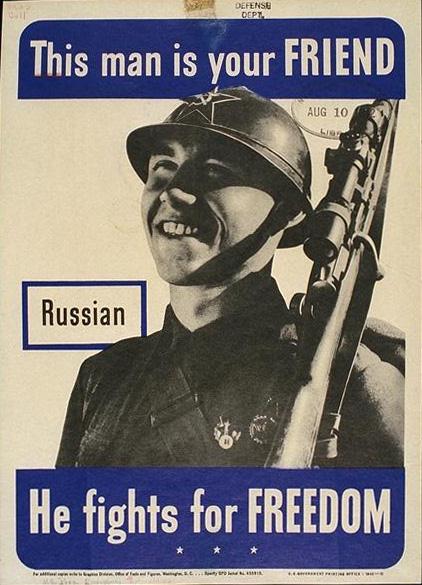

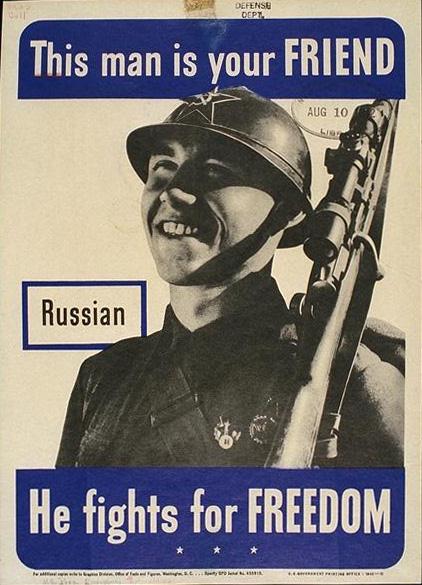

When the order ''Na shturm, marshch!'' (Assault, march!) was given, the Soviet infantry would charge the enemy while shouting the traditional Russian battle cry ''Urra!'' ( ru , ура !, pronounced oo-rah), the sound of which many German veterans found terrifying. During the charge, the riflemen would fire with rifles and submachine guns while throwing grenades before closing in for ''blizhnii boi'' ( ru , ближний бой—close combat—close-quarter fighting with guns, bayonets, rifle butts, knives, digging tools and fists), a type of fighting at which the Red Army excelled.Rottman, Gordon ''Soviet Rifleman 1941-45'', London: Osprey 2007 page 17. On the defensive, the ''frontoviki'' had a reputation for their skill at camouflaging their positions and for their discipline in withholding fire until Axis forces came within close range. Before 1941 Red Army doctrine had called for opening fire at maximum range, but experience quickly taught the advantages of ambushing the enemy with surprise fire at close ranges from multiple positions.

The typical ''frontovik'' during the war was an ethnic Russian aged 19–24 with an average height of .Rottman, Gordon ''Soviet Rifleman 1941-45'', London: Osprey 2007 page 18. Most of the men were shaven bald to prevent lice and the few who did grow their hair kept it very short. The American historian Gordon Rottman describes the uniforms as "simple and functional". In combat, the men wore olive-brown helmets or the '' pilotka'' (side cap). Officers wore a ''shlem'' (helmet) or a ( ru , фуражка—

When the order ''Na shturm, marshch!'' (Assault, march!) was given, the Soviet infantry would charge the enemy while shouting the traditional Russian battle cry ''Urra!'' ( ru , ура !, pronounced oo-rah), the sound of which many German veterans found terrifying. During the charge, the riflemen would fire with rifles and submachine guns while throwing grenades before closing in for ''blizhnii boi'' ( ru , ближний бой—close combat—close-quarter fighting with guns, bayonets, rifle butts, knives, digging tools and fists), a type of fighting at which the Red Army excelled.Rottman, Gordon ''Soviet Rifleman 1941-45'', London: Osprey 2007 page 17. On the defensive, the ''frontoviki'' had a reputation for their skill at camouflaging their positions and for their discipline in withholding fire until Axis forces came within close range. Before 1941 Red Army doctrine had called for opening fire at maximum range, but experience quickly taught the advantages of ambushing the enemy with surprise fire at close ranges from multiple positions.

The typical ''frontovik'' during the war was an ethnic Russian aged 19–24 with an average height of .Rottman, Gordon ''Soviet Rifleman 1941-45'', London: Osprey 2007 page 18. Most of the men were shaven bald to prevent lice and the few who did grow their hair kept it very short. The American historian Gordon Rottman describes the uniforms as "simple and functional". In combat, the men wore olive-brown helmets or the '' pilotka'' (side cap). Officers wore a ''shlem'' (helmet) or a ( ru , фуражка—

The Soviets repulsed the important German strategic southern campaign and, although 2.5 million Soviet casualties were suffered in that effort, it permitted the Soviets to take the offensive for most of the rest of the war on the Eastern Front.

The Soviets repulsed the important German strategic southern campaign and, although 2.5 million Soviet casualties were suffered in that effort, it permitted the Soviets to take the offensive for most of the rest of the war on the Eastern Front.

Stalin personally told a Polish general requesting information about missing Polish officers that all of the Poles were freed, and that not all could be accounted because the Soviets "lost track" of them in

Stalin personally told a Polish general requesting information about missing Polish officers that all of the Poles were freed, and that not all could be accounted because the Soviets "lost track" of them in

Biuletyn „Kombatant" nr specjalny (148) czerwiec 2003

Special Edition of Kombatant Bulletin No.148 6/2003 on the occasion of the Year of General Sikorski. Official publication of the Polish government Agency of Combatants and RepressedРомуальд Святек, "Катынский лес", Военно-исторический журнал, 1991, №9, After Polish railroad workers found the mass grave, the Nazis used the massacre to attempt to drive a wedge between Stalin and the other Allies, Engel, David.

Facing a Holocaust: The Polish Government-In-Exile and the Jews, 1943–1945

. 1993. . including bringing in a European commission of investigators from twelve countries to examine the graves.Bauer, Eddy. "The Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of World War II". Marshall Cavendish, 1985 In 1943, as the Soviets prepared to retake Poland, Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels correctly guessed that Stalin would attempt to falsely claim that the Germans massacred the victims. Goebbels, Joseph. The Goebbels Diaries (1942–1943). Translated by Louis P. Lochner. Doubleday & Company. 1948 As Goebbels predicted, the Soviets had a "commission" investigate the matter, falsely concluding that the Germans had killed the PoWs. The Soviets did not admit responsibility until 1990."CHRONOLOGY 1990; The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe." '' Foreign Affairs'', 1990, pp. 212. In 1943, Stalin ceded to his generals' call for the Soviet Union to take a defensive stance because of disappointing losses after Stalingrad, a lack of reserves for offensive measures and a prediction that the Germans would likely next attack a bulge in the Soviet front at In November 1943, Stalin met with Churchill and Roosevelt in

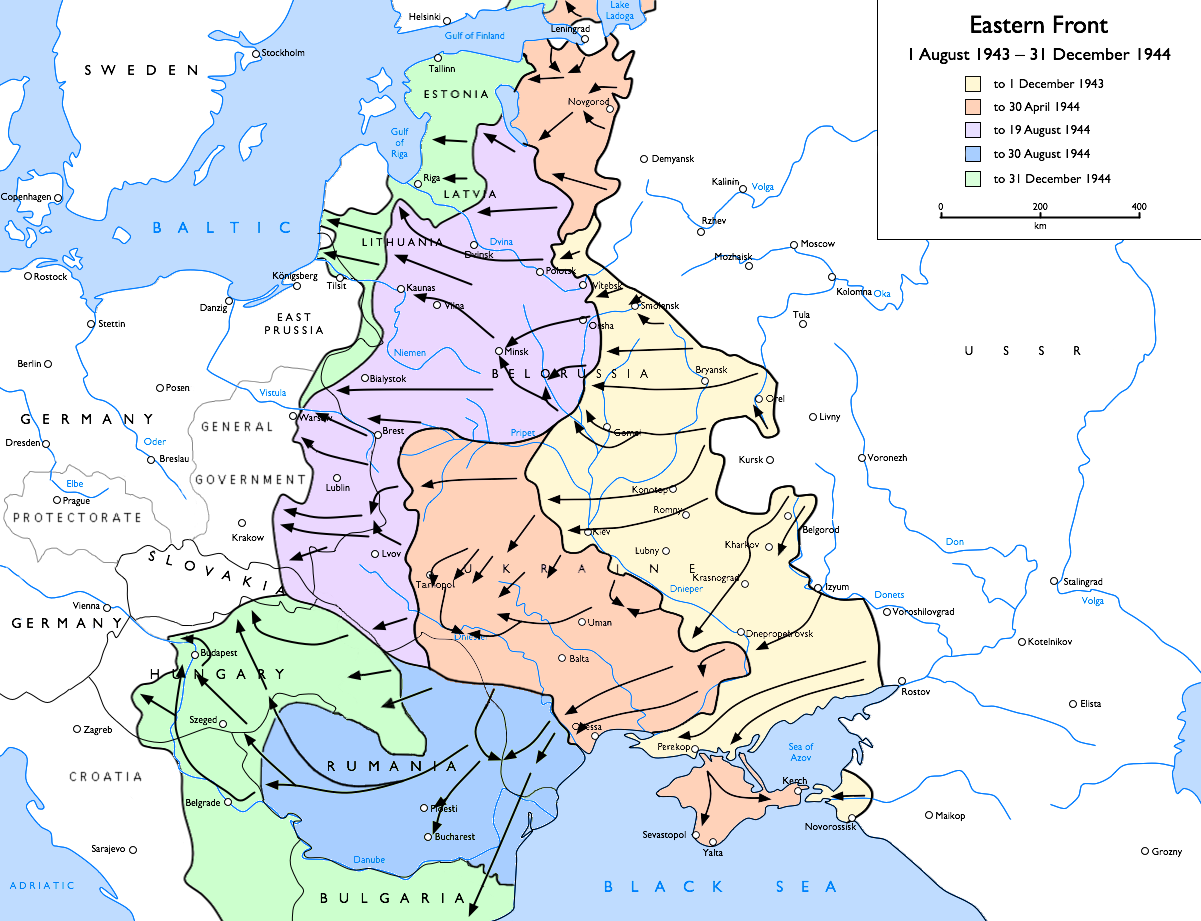

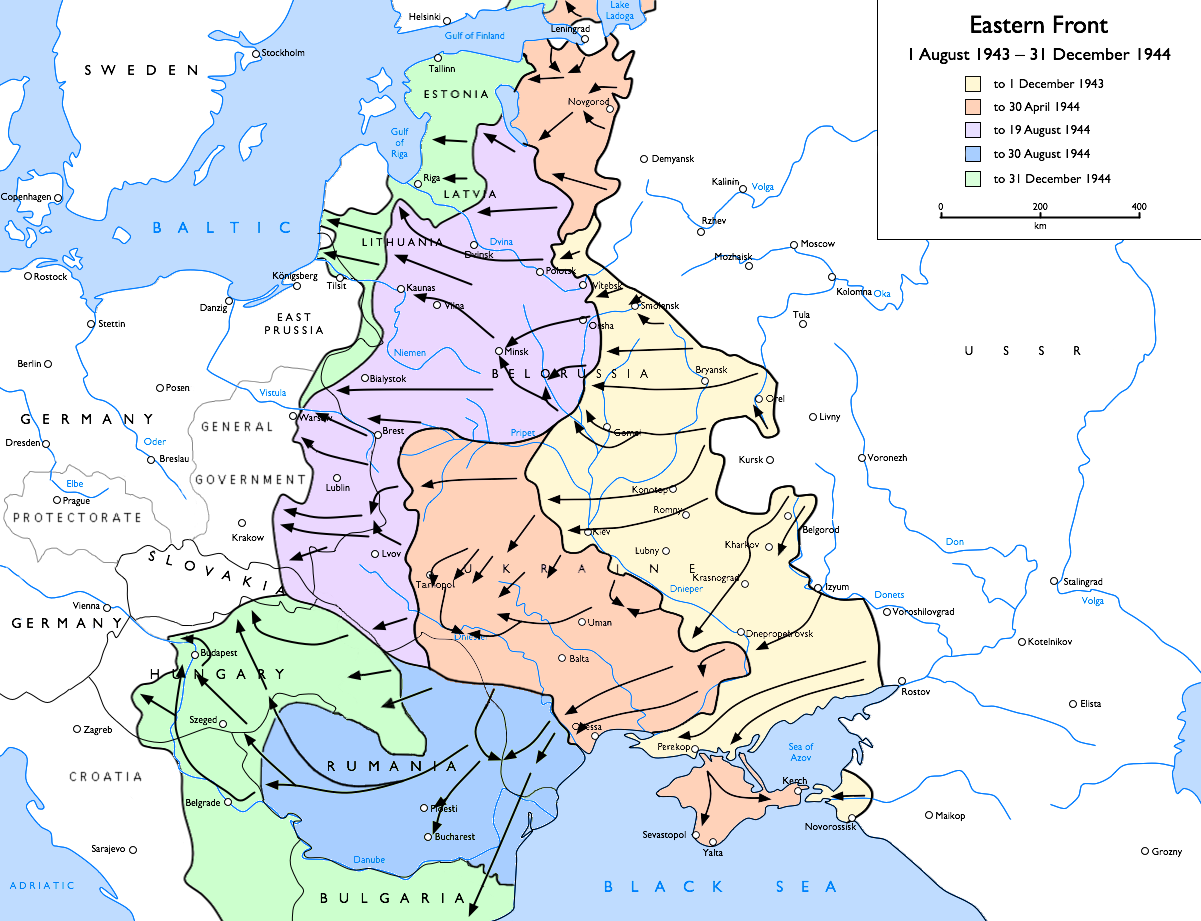

In November 1943, Stalin met with Churchill and Roosevelt in  Successes at Operation Bagration and in the year that followed were, in large part, due to an operational improved of battle-hardened Red Army, which has learned painful lessons from previous years battling the powerful Wehrmacht: better planning of offensives, efficient use of artillery, better handling of time and space during attacks in contradiction to Stalin's order "not a step back". To a lesser degree, the success of Bagration was due to a weakened

Successes at Operation Bagration and in the year that followed were, in large part, due to an operational improved of battle-hardened Red Army, which has learned painful lessons from previous years battling the powerful Wehrmacht: better planning of offensives, efficient use of artillery, better handling of time and space during attacks in contradiction to Stalin's order "not a step back". To a lesser degree, the success of Bagration was due to a weakened  Beginning in the summer of 1944, a reinforced German Army Centre Group did prevent the Soviets from advancing in around Warsaw for nearly half a year. Some historians claim that the Soviets' failure to advance was a purposeful Soviet stall to allow the Wehrmacht to slaughter members of a

Beginning in the summer of 1944, a reinforced German Army Centre Group did prevent the Soviets from advancing in around Warsaw for nearly half a year. Some historians claim that the Soviets' failure to advance was a purposeful Soviet stall to allow the Wehrmacht to slaughter members of a  Other important advances occurred in late 1944, such as the invasion of Romania in August and

Other important advances occurred in late 1944, such as the invasion of Romania in August and

By April 1945 Nazi Germany faced its last days, with 1.9 million German soldiers in the East fighting 6.4 million Red Army soldiers while 1 million German soldiers in the West battled 4 million Western Allied soldiers.Glantz, David, ''The Soviet-German War 1941–45: Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay'', October 11, 2001 While initial talk postulated a race to Berlin by the Allies, after Stalin successfully lobbied for Eastern Germany to fall within the Soviet "sphere of influence" at

By April 1945 Nazi Germany faced its last days, with 1.9 million German soldiers in the East fighting 6.4 million Red Army soldiers while 1 million German soldiers in the West battled 4 million Western Allied soldiers.Glantz, David, ''The Soviet-German War 1941–45: Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay'', October 11, 2001 While initial talk postulated a race to Berlin by the Allies, after Stalin successfully lobbied for Eastern Germany to fall within the Soviet "sphere of influence" at  Despite the Soviets' possession of Hitler's remains, Stalin did not believe that his old nemesis was actually dead, a belief that persisted for years after the war.Kershaw, Ian, ''Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis'', W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, , pages 1038–39 Stalin later directed aides to spend years researching and writing a secret book about Hitler's life for his own private reading.

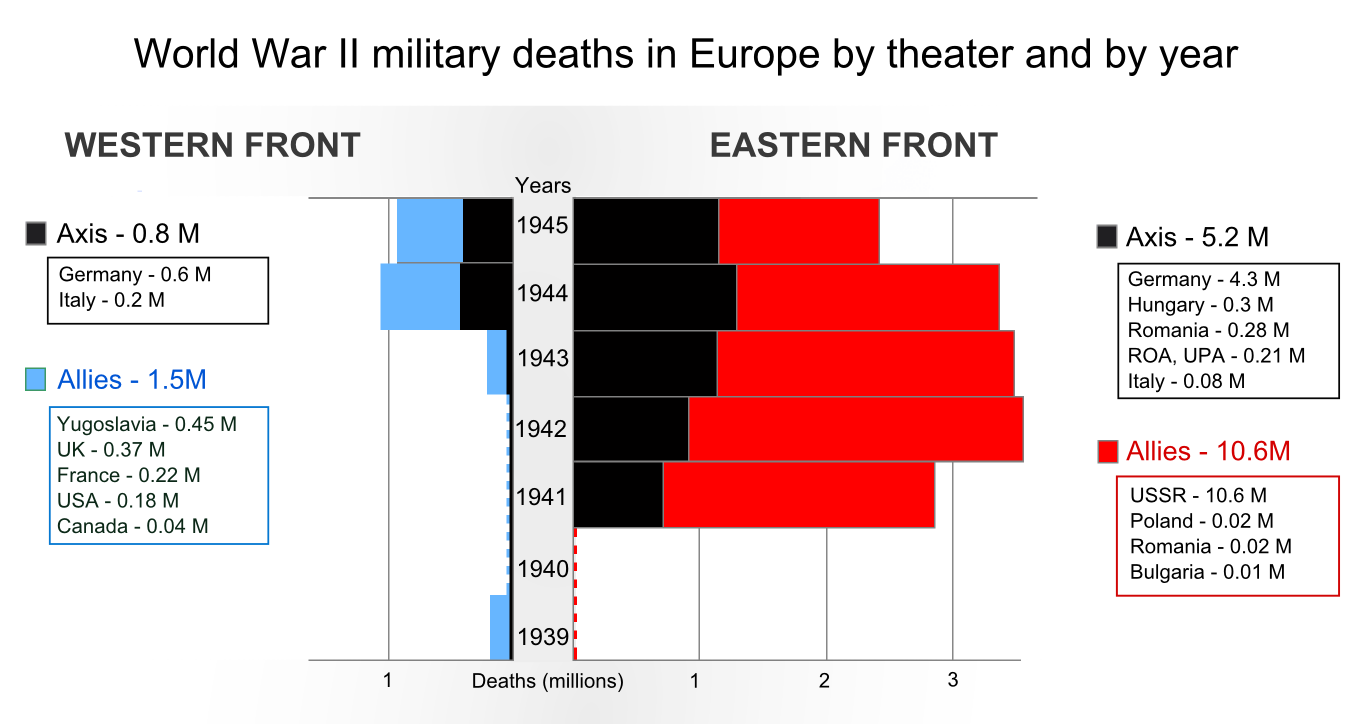

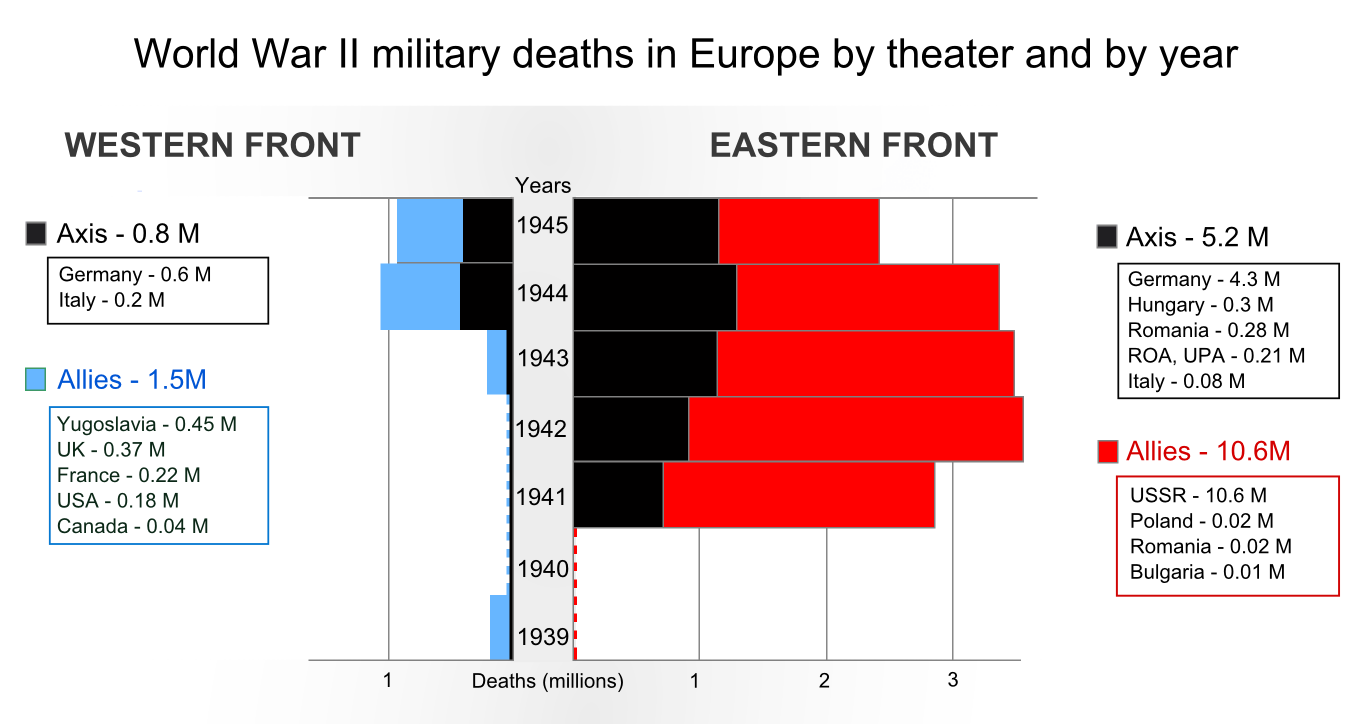

Fending off the German invasion and pressing to victory over Nazi Germany in the Second World War required a tremendous sacrifice by the Soviet Union (more than by any other country in human history). Soviet casualties totaled around 27 million.Glantz, David, ''The Soviet-German War 1941–45: Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay'', October 11, 2001, page 13 Although figures vary, the Soviet civilian death toll probably reached 18 million. Millions of Soviet soldiers and civilians disappeared into German detention camps and slave-labor factories, while millions more suffered permanent physical and mental damage. Soviet economic losses, including losses in resources and manufacturing capacity in western Russia and Ukraine, were also catastrophic. The war resulted in the destruction of approximately 70,000 Soviet cities, towns and villages - 6 million houses, 98,000 farms, 32,000 factories, 82,000 schools, 43,000 libraries, 6,000 hospitals and thousands of kilometers of roads and railway track.

On 9 August 1945 the Soviet Union invaded Japanese-controlled Manchukuo and declared war on Japan. Battle-hardened Soviet troops and their experienced commanders rapidly conquered Japanese-held territories in

Despite the Soviets' possession of Hitler's remains, Stalin did not believe that his old nemesis was actually dead, a belief that persisted for years after the war.Kershaw, Ian, ''Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis'', W. W. Norton & Company, 2001, , pages 1038–39 Stalin later directed aides to spend years researching and writing a secret book about Hitler's life for his own private reading.

Fending off the German invasion and pressing to victory over Nazi Germany in the Second World War required a tremendous sacrifice by the Soviet Union (more than by any other country in human history). Soviet casualties totaled around 27 million.Glantz, David, ''The Soviet-German War 1941–45: Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay'', October 11, 2001, page 13 Although figures vary, the Soviet civilian death toll probably reached 18 million. Millions of Soviet soldiers and civilians disappeared into German detention camps and slave-labor factories, while millions more suffered permanent physical and mental damage. Soviet economic losses, including losses in resources and manufacturing capacity in western Russia and Ukraine, were also catastrophic. The war resulted in the destruction of approximately 70,000 Soviet cities, towns and villages - 6 million houses, 98,000 farms, 32,000 factories, 82,000 schools, 43,000 libraries, 6,000 hospitals and thousands of kilometers of roads and railway track.

On 9 August 1945 the Soviet Union invaded Japanese-controlled Manchukuo and declared war on Japan. Battle-hardened Soviet troops and their experienced commanders rapidly conquered Japanese-held territories in

In July 1942, Stalin issued Order No. 227, directing that any commander or commissar of a regiment, battalion or army, who allowed retreat without permission from his superiors was subject to military tribunal. The order called for soldiers found guilty of disciplinary infractions to be forced into " penal battalions", which were sent to the most dangerous sections of the front lines. From 1942 to 1945, 427,910 soldiers were assigned to penal battalions.G. I. Krivosheev. Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses. Greenhill 1997 The order also directed "blocking detachments" to shoot fleeing panicked troops at the rear. In the first three months following the order 1,000 penal troops were shot by "blocking detachments, and sent 24,933 troops to penal battalions. Despite having some effect initially, this measure proved to have a deteriorating effect on the troops' morale, so by October 1942 the idea of regular blocking detachments was quietly dropped By 29 ''October'' 1944 the blocking detachments were officially disbanded.

Soviet POWs and forced labourers who survived German captivity were sent to special "transit" or "filtration" camps meant to determine which were potential traitors. Of the approximately 4 million to be repatriated, 2,660,013 were civilians and 1,539,475 were former POWs. Of the total, 2,427,906 were sent home, 801,152 were reconscripted into the armed forces, 608,095 were enrolled in the work battalions of the defence ministry, 226,127 were transferred to the authority of the NKVD for punishment, which meant a transfer to the Gulag system and 89,468 remained in the transit camps as reception personnel until the repatriation process was finally wound up in the early 1950s.

In July 1942, Stalin issued Order No. 227, directing that any commander or commissar of a regiment, battalion or army, who allowed retreat without permission from his superiors was subject to military tribunal. The order called for soldiers found guilty of disciplinary infractions to be forced into " penal battalions", which were sent to the most dangerous sections of the front lines. From 1942 to 1945, 427,910 soldiers were assigned to penal battalions.G. I. Krivosheev. Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses. Greenhill 1997 The order also directed "blocking detachments" to shoot fleeing panicked troops at the rear. In the first three months following the order 1,000 penal troops were shot by "blocking detachments, and sent 24,933 troops to penal battalions. Despite having some effect initially, this measure proved to have a deteriorating effect on the troops' morale, so by October 1942 the idea of regular blocking detachments was quietly dropped By 29 ''October'' 1944 the blocking detachments were officially disbanded.

Soviet POWs and forced labourers who survived German captivity were sent to special "transit" or "filtration" camps meant to determine which were potential traitors. Of the approximately 4 million to be repatriated, 2,660,013 were civilians and 1,539,475 were former POWs. Of the total, 2,427,906 were sent home, 801,152 were reconscripted into the armed forces, 608,095 were enrolled in the work battalions of the defence ministry, 226,127 were transferred to the authority of the NKVD for punishment, which meant a transfer to the Gulag system and 89,468 remained in the transit camps as reception personnel until the repatriation process was finally wound up in the early 1950s.

Soviet troops reportedly raped German women and girls, with total victim estimates ranging from tens of thousands to two million. During and after the

Soviet troops reportedly raped German women and girls, with total victim estimates ranging from tens of thousands to two million. During and after the

Nazi propaganda had told Wehrmacht's soldiers the invasion of the Soviet Union was a war of extermination.

British historian

Nazi propaganda had told Wehrmacht's soldiers the invasion of the Soviet Union was a war of extermination.

British historian

The city of Leningrad endured more suffering and hardships than any other city in the Soviet Union during the war, as it was under siege for 872 days, from September 8, 1941, to January 27, 1944. Hunger, malnutrition, disease, starvation, and even cannibalism became common during the siege of Leningrad; civilians lost weight, grew weaker, and became more vulnerable to diseases. Citizens of Leningrad managed to survive through a number of methods with varying degrees of success. Since only 400,000 people were evacuated before the siege began, this left 2.5 million in Leningrad, including 400,000 children. More managed to escape the city; this was most successful when Lake Ladoga froze over and people could walk over the ice road—or "

The city of Leningrad endured more suffering and hardships than any other city in the Soviet Union during the war, as it was under siege for 872 days, from September 8, 1941, to January 27, 1944. Hunger, malnutrition, disease, starvation, and even cannibalism became common during the siege of Leningrad; civilians lost weight, grew weaker, and became more vulnerable to diseases. Citizens of Leningrad managed to survive through a number of methods with varying degrees of success. Since only 400,000 people were evacuated before the siege began, this left 2.5 million in Leningrad, including 400,000 children. More managed to escape the city; this was most successful when Lake Ladoga froze over and people could walk over the ice road—or "

Even though it won the conflict, the war had a profound and devastating long-term effect in the Soviet Union. The financial burden was catastrophic: by one estimate, the Soviet Union spent $192 billion. The US sent around $11 billion in Lend-Lease supplies to the Soviet Union during the war.

American experts estimate that the Soviet Union lost almost all the wealth it gained from the industrialization efforts during the 1930s. Its economy also shrank by 20% between 1941 and 1945 and did not recover its pre-war levels all until the 1960s. British historian

Even though it won the conflict, the war had a profound and devastating long-term effect in the Soviet Union. The financial burden was catastrophic: by one estimate, the Soviet Union spent $192 billion. The US sent around $11 billion in Lend-Lease supplies to the Soviet Union during the war.

American experts estimate that the Soviet Union lost almost all the wealth it gained from the industrialization efforts during the 1930s. Its economy also shrank by 20% between 1941 and 1945 and did not recover its pre-war levels all until the 1960s. British historian

online review

* Goldman, Wendy Z., and Donald Filtzer. ''Hunger and War: Food Provisioning in the Soviet Union during World War II'' (Indiana UP, 2015) * Hill, Alexander. "British Lend-Lease Aid and the Soviet War Effort, June 1941 – June 1942," ''Journal of Military History'' (2007) 71#3 pp 773–808. * Overy, Richard. ''Russia's War: A History of the Soviet Effort: 1941–1945'' (1998) 432p

excerpt and txt search

* Reese, Roger R. "Motivations to Serve: The Soviet Soldier in the Second World War," ''Journal of Slavic Military Studies'' (2007) 10#2 pp 263–282. * * Vallin, Jacques; Meslé, France; Adamets, Serguei; and Pyrozhkov, Serhii. "A New Estimate of Ukrainian Population Losses During the Crises of the 1930s and 1940s." ''Population Studies'' (2002) 56(3): 249–264. Reports life expectancy at birth fell to a level as low as ten years for females and seven for males in 1933 and plateaued around 25 for females and 15 for males in the period 1941–44.

The

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

signed the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

on 30 September 1938, an agreement which provided "cession to Germany of the Sudeten German territory" of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. Almost a year later the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

signed a non-aggression pact

A non-aggression pact or neutrality pact is a treaty between two or more states/countries that includes a promise by the signatories not to engage in military action against each other. Such treaties may be described by other names, such as a tr ...

with Germany on 23 August 1939. In addition to stipulations of non-aggression, the treaty included a secret protocol that divided Eastern Europe into German and Soviet "spheres of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

", anticipating potential "territorial and political rearrangements" of these countries.chathamhouse.org, 2011/ref> Germany invaded

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

on 1 September 1939, starting World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. The Soviets invaded eastern Poland on 17 September. Following the Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

with Finland, the Soviets were ceded territories by Finland. This was followed by annexations of the Baltic states and parts of Romania.

On 22 June 1941, Hitler launched an invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

with the largest invasion force in history, leading to some of the largest battles and most horrific atrocities. Operation Barbarossa comprised three army groups, with Finland attacking from the north. The city of Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

was besieged

Besieged may refer to:

* the state of being under siege

* ''Besieged'' (film), a 1998 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

{{disambiguation ...

while other major cities fell to the Germans during the invasion. Despite initial successes, the German offensive halted to a stop in the Battle of Moscow, and the Soviets launched a counteroffensive, pushing the Germans back. The failure of Operation Barbarossa reversed the fortunes of Germany. Stalin was confident that the Allied war machine would eventually defeat Germany. The Soviet Union repulsed Axis attacks, such as in the Battle of Stalingrad and the Battle of Kursk

The Battle of Kursk was a major World War II Eastern Front engagement between the forces of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union near Kursk in the southwestern USSR during late summer 1943; it ultimately became the largest tank battle in history ...

, which marked a turning point in the war. The Western Allies provided support to the Soviets in the form of Lend-Lease as well as air and naval support. Stalin met with Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

and Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

at the Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embass ...

and discussed a two-front war against Germany and the future of Europe after the war. The Soviets launched successful offensives to regain territorial losses and began a push to Berlin. The Germans unconditionally surrendered in May 1945 after Berlin fell

A fell (from Old Norse ''fell'', ''fjall'', "mountain"Falk and Torp (2006:161).) is a high and barren landscape feature, such as a mountain or moor-covered hill. The term is most often employed in Fennoscandia, Iceland, the Isle of Man, pa ...

.

The bulk of Soviet fighting took place on the Eastern Front—including the Continuation War

The Continuation War, also known as the Second Soviet-Finnish War, was a conflict fought by Finland and Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union from 1941 to 1944, as part of World War II.; sv, fortsättningskriget; german: Fortsetzungskrieg. A ...

with Finland—but it also invaded Iran in August 1941 with the British, and the Soviets later entered the war against Japan in August 1945, which began with an invasion of Manchuria. The Soviets had border conflicts with Japan up to 1939 before signing a non-aggression pact

A non-aggression pact or neutrality pact is a treaty between two or more states/countries that includes a promise by the signatories not to engage in military action against each other. Such treaties may be described by other names, such as a tr ...

with Japan in 1941. Stalin had agreed with the Western Allies to enter the war against Japan at the Tehran Conference in 1943 and at the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

in February 1945 once Germany was defeated. The entry of the Soviet Union in the war against Japan along with the atomic bombings

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

by the United States led to Japan to surrender, marking the end of World War II.

The Soviet Union suffered the greatest number of casualties in the war, losing more than 20 million citizens, about a third of all World War II casualties

World War II was the deadliest military conflict in history. An estimated total of 70–85 million people perished, or about 3% of the 2.3 billion (est.) people on Earth in 1940. Deaths directly caused by the war (including military and civ ...

. The full demographic loss to the Soviet people was even greater. The German ''Generalplan Ost

The ''Generalplan Ost'' (; en, Master Plan for the East), abbreviated GPO, was the Nazi German government's plan for the genocide and ethnic cleansing on a vast scale, and colonization of Central and Eastern Europe by Germans. It was to be under ...

'' aimed to create more ''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imper ...

'' () for Germany through extermination. An estimated 3.5 million Soviet prisoners of war died in German captivity as a result of deliberate mistreatment and atrocities, and millions of civilians, including Soviet Jews

The history of the Jews in the Soviet Union is inextricably linked to much earlier expansionist policies of the Russian Empire conquering and ruling the eastern half of the European continent already before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. "For ...

, were killed in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

. However, at the expense of a large sacrifice, the Soviet Union emerged as a global superpower. The Soviets installed dependent communist governments in Eastern Europe, and tensions with the United States became known as the Cold War.

Non-aggression pact with Germany

During the 1930s, Soviet foreign minister

During the 1930s, Soviet foreign minister Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov w ...

emerged as a leading voice for the official Soviet policy of collective security with the Western powers against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. In 1935, Litvinov negotiated treaties of mutual assistance with France and with Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

with the aim of containing Hitler's expansion. After the Munich Agreement, which gave parts of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany, the Western democracies' policy of appeasement led the Soviet Union to reorient its foreign policy towards a rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word ''rapprocher'' ("to bring together"), is a re-establishment of cordial relations between two countries. This may be done due to a mutual enemy, as was the case with Germ ...

with Germany. On 3 May 1939, Stalin replaced Litvinov, who was closely identified with the anti-German position, with Vyacheslav Molotov.

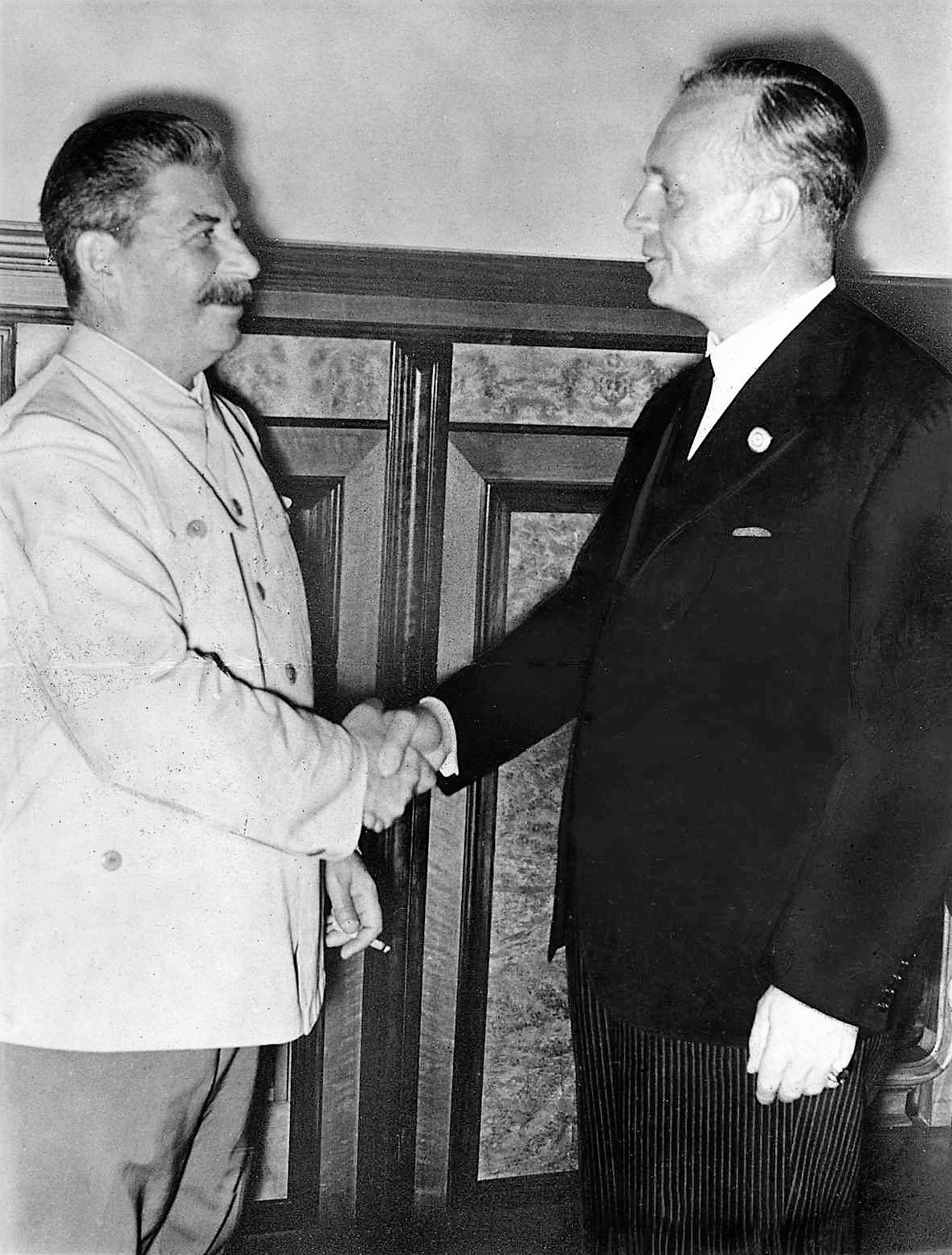

In August 1939, Stalin accepted Hitler's proposal into a non-aggression pact with Germany, negotiated by the foreign ministers Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

for the Soviets and Joachim von Ribbentrop for the Germans. Officially a non-aggression treaty only, an appended secret protocol, also reached on 23 August, divided the whole of eastern Europe into German and Soviet spheres of influence.Encyclopædia Britannica, ''German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact'', 2008''Text of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact''executed 23 August 1939 The USSR was promised the eastern part of

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, then primarily populated by Ukrainians and Belarusians, in case of its dissolution, and Germany recognised Latvia, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

and Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

as parts of the Soviet sphere of influence, with Lithuania added in a second secret protocol in September 1939.Christie, Kenneth, ''Historical Injustice and Democratic Transition in Eastern Asia and Northern Europe: Ghosts at the Table of Democracy'', RoutledgeCurzon, 2002, Another clause of the treaty was that Bessarabia, then part of Romania, was to be joined to the Moldovan SSR, and become the Moldovan SSR under control of Moscow.

The pact was reached two days after the breakdown of Soviet military talks with British and French representatives in August 1939 over a potential Franco-Anglo-Soviet alliance. Political discussions had been suspended on 2 August, when Molotov stated that they could not be resumed until progress was made in military talks late in August, after the talks had stalled over guarantees for the Baltic states, while the military talks upon which Molotov insisted started on 11 August. At the same time, Germany—with whom the Soviets had started secret negotiations on 29 JulyUlam, Adam Bruno,''Stalin: The Man and His Era'', Beacon Press, 1989, , page 509-10Shirer, William L., ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany'', Simon and Schuster, 1990 , page 503 – argued that it could offer the Soviets better terms than Britain and France, with Ribbentrop insisting, "there was no problem between the Baltic and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

that could not be solved between the two of us."Fest, Joachim C., ''Hitler'', Harcourt Brace Publishing, 2002 , page 589-90 German officials stated that, unlike Britain, Germany could permit the Soviets to continue their developments unmolested, and that "there is one common element in the ideology of Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union: opposition to the capitalist democracies of the West". By that time, Molotov had obtained information regarding Anglo-German negotiations and a pessimistic report from the Soviet ambassador in France.

After disagreement regarding Stalin's demand to move

After disagreement regarding Stalin's demand to move Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

troops through Poland and Romania (which Poland and Romania opposed), on 21 August, the Soviets proposed adjournment of military talks using the pretext that the absence of the senior Soviet personnel at the talks interfered with the autumn manoeuvres of the Soviet forces, though the primary reason was the progress being made in the Soviet-German negotiations. That same day, Stalin received assurance that Germany would approve secret protocols to the proposed non-aggression pact that would grant the Soviets land in Poland, the Baltic states, Finland and Romania, after which Stalin telegrammed Hitler that night that the Soviets were willing to sign the pact and that he would receive Ribbentrop on 23 August.Shirer, William L., ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany'', Simon and Schuster, 1990 , pages 528 Regarding the larger issue of collective security, some historians state that one reason that Stalin decided to abandon the doctrine was the shaping of his views of France and Britain by their entry into the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

and the subsequent failure to prevent the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. Stalin may also have viewed the pact as gaining time in an eventual war with Hitler in order to reinforce the Soviet military and shifting Soviet borders westwards, which would be militarily beneficial in such a war.

Stalin and Ribbentrop spent most of the night of the pact's signing trading friendly stories about world affairs and cracking jokes (a rarity for Ribbentrop) about Britain's weakness, and the pair even joked about how the Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

principally scared "British shopkeepers."Shirer, William L., ''The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany'', Simon and Schuster, 1990 , pages 541 They further traded toasts, with Stalin proposing a toast to Hitler's health and Ribbentrop proposing a toast to Stalin.

The division of Eastern Europe and other invasions

On 1 September 1939, the German invasion of its agreed upon portion of Poland started the

On 1 September 1939, the German invasion of its agreed upon portion of Poland started the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. On 17 September the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

invaded eastern Poland and occupied the Polish territory assigned to it by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland. Eleven days later, the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was modified, allotting Germany a larger part of Poland, while ceding most of Lithuania to the Soviet Union. The Soviet portions lay east of the so-called Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, to ...

, an ethnographic frontier between Russia and Poland drawn up by a commission of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.

After taking around 300,000 Polish prisoners in 1939 and early 1940,obozy jenieckie zolnierzy polskich

After taking around 300,000 Polish prisoners in 1939 and early 1940,obozy jenieckie zolnierzy polskich(Prison camps for Polish soldiers) Encyklopedia PWN. Last accessed on 28 November 2006.Edukacja Humanistyczna w wojsku

. 1/2005. Dom wydawniczy Wojska Polskiego. . (Official publication of the Polish Army) Молотов на V сессии Верховного Совета 31 октября цифра «примерно 250 тыс.» (Please provide translation of the reference title and publication data and means) Отчёт Украинского и Белорусского фронтов Красной Армии Мельтюхов, с. 367

(Please provide translation of the reference title and publication data and means)

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

officers conducted lengthy interrogations of the prisoners in camps that were, in effect, a selection process to determine who would be killed. Fischer, Benjamin B.,The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field

, ''

Studies in Intelligence

''Studies in Intelligence'' is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal on intelligence that is published by the Center for the Study of Intelligence, a group within the United States Central Intelligence Agency. It contains both classified and u ...

'', Winter 1999–2000. On March 5, 1940, pursuant to a note to Stalin from Lavrenty Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

, the members of the Soviet Politburo (including Stalin) signed and 22,000 military and intellectuals were executed - They were labelled "nationalists and counterrevolutionaries", kept at camps and prisons in occupied western Ukraine and Belarus. This became known as the Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, "Katyń crime"; russian: link=yes, Катынская резня ''Katynskaya reznya'', "Katyn massacre", or russian: link=no, Катынский расстрел, ''Katynsky rasstrel'', "Katyn execution" was a series of m ...

. SanfordGoogle Books, p. 20-24.

/ref>

Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Vasili M. Blokhin, chief executioner

An executioner, also known as a hangman or headsman, is an official who executes a sentence of capital punishment on a legally condemned person.

Scope and job

The executioner was usually presented with a warrant authorising or order ...

for the NKVD, personally shot 6,000 of the captured Polish officers in 28 consecutive nights, which remains one of the most organized and protracted mass murders by a single individual on record. During his 29-year career Blokhin shot an estimated 50,000 people, making him ostensibly the most prolific official executioner in recorded world history.

In August 1939, Stalin declared that he was going to "solve the Baltic problem, and thereafter, forced Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia to sign treaties for "mutual assistance."

In November 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Finland. The Finnish defensive effort defied Soviet expectations, and after stiff losses, as well as the unsuccessful attempt to install a puppet government

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

in Helsinki, Stalin settled for an interim peace

The Interim Peace ( fi, Välirauha, sv, Mellanfreden) was a short period in the history of Finland during the Second World War. The term is used for the time between the Winter War and the Continuation War, lasting a little over 15 months, from 1 ...

granting the Soviet Union parts of Karelia and Salla

Salla (''Kuolajärvi'' until 1936) ( smn, Kyelijävri) is a municipality of Finland, located in Lapland. The municipality has a population of

() and covers an area of of

which

is water. The population density is

.

The nearby settlement of ...

(9% of Finnish territory).Kennedy-Pipe, Caroline, ''Stalin's Cold War'', New York : Manchester University Press, 1995, Soviet official casualty counts in the war exceeded 200,000, while Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

later claimed the casualties may have been one million. After this campaign, Stalin took actions to modify training and improve propaganda efforts in the Soviet military.

In mid-June 1940, when international attention was focused on the German invasion of France

France has been invaded on numerous occasions, by foreign powers or rival French governments; there have also been unimplemented invasion plans.

* the 1746 War of the Austrian Succession, Austria-Italian forces supported by the British navy attemp ...

, Soviet NKVD troops raided border posts in the Baltic countries.Senn, Alfred Erich, ''Lithuania 1940 : revolution from above'', Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007 Stalin claimed that the mutual assistance treaties had been violated, and gave six-hour ultimatums for new governments to be formed in each country, including lists of persons for cabinet posts provided by the Kremlin. Thereafter, state administrations were liquidated and replaced by Soviet cadres, followed by mass repression in which 34,250 Latvians, 75,000 Lithuanians and almost 60,000 Estonians were deported or killed. Elections for parliament and other offices were held with single candidates listed, the official results of which showed pro-Soviet candidates approval by 92.8 percent of the voters of Estonia, 97.6 percent of the voters in Latvia and 99.2 percent of the voters in Lithuania. The resulting peoples' assemblies immediately requested admission into the USSR, which was granted. In late June 1940, Stalin directed the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, proclaiming this formerly Romanian territory part of the Moldavian SSR

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic ( ro, Republica Sovietică Socialistă Moldovenească, Moldovan Cyrillic: ) was one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union which existed from 1940 to 1991. The republic was formed on 2 August 194 ...

. But in annexing northern Bukovina, Stalin had gone beyond the agreed limits. The invasion of Bukovina violated the pact, as it went beyond the Soviet sphere of influence agreed with Germany.

After the

After the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

was signed by Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

Germany, Japan and Italy, in October 1940, Stalin personally wrote to Ribbentrop about entering an agreement regarding a "permanent basis" for their "mutual interests." Stalin sent Molotov to Berlin to negotiate the terms for the Soviet Union to join the Axis and potentially enjoy the spoils of the pact. At Stalin's direction, Molotov insisted on Soviet interest in Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Greece, though Stalin had earlier unsuccessfully personally lobbied Turkish leaders to not sign a mutual assistance pact with Britain and France. Ribbentrop asked Molotov to sign another secret protocol with the statement: "The focal point of the territorial aspirations of the Soviet Union would presumably be centered south of the territory of the Soviet Union in the direction of the Indian Ocean." Molotov took the position that he could not take a "definite stand" on this without Stalin's agreement. Stalin did not agree with the suggested protocol, and negotiations broke down. In response to a later German proposal, Stalin stated that the Soviets would join the Axis if Germany foreclosed acting in the Soviet's sphere of influence. Shortly thereafter, Hitler issued a secret internal directive related to his plan to invade the Soviet Union.

In an effort to demonstrate peaceful intentions toward Germany, on 13 April 1941, Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

oversaw the signing of a neutrality pact with Japan. Since the Treaty of Portsmouth, Russia had been competing with Japan for spheres of influence in the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

, where there was a power vacuum with the collapse of Imperial China. Although similar to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, that Soviet Union signed Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact with the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

, to maintain the national interest of Soviet's sphere of influence in the European continent as well as the Far East conquest, whilst among the few countries in the world diplomatically recognizing Manchukuo, and allowed the rise of German invasion in Europe and Japanese aggression in Asia, but the Japanese defeat of Battles of Khalkhin Gol

The Battles of Khalkhin Gol (russian: Бои на Халхин-Голе; mn, Халхын голын байлдаан) were the decisive engagements of the undeclared Soviet–Japanese border conflicts involving the Soviet Union, Mongolia, Ja ...

was the forceful factor to the temporary settlement before Soviet invasion of Manchuria

The Soviet invasion of Manchuria, formally known as the Manchurian strategic offensive operation (russian: Манчжурская стратегическая наступательная операция, Manchzhurskaya Strategicheskaya Nastu ...

in 1945 as the result of Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

. While Stalin had little faith in Japan's commitment to neutrality, he felt that the pact was important for its political symbolism, to reinforce a public affection for Germany, before military confrontation when Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

controlled Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

and for Soviet Union to take control Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

. Stalin felt that there was a growing split in German circles about whether Germany should initiate a war with the Soviet Union, though Stalin was not aware of Hitler's further military ambition.

Termination of the pact

During the early morning of 22 June 1941,Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

terminated the pact by launching Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

, the Axis invasion of Soviet-held territories and the Soviet Union that began the war on the Eastern Front. Before the invasion, Stalin thought that Germany would not attack the Soviet Union until Germany had defeated Britain. At the same time, Soviet generals warned Stalin that Germany had concentrated forces on its borders. Two highly placed Soviet spies in Germany, "Starshina" and "Korsikanets", had sent dozens of reports to Moscow containing evidence of preparation for a German attack. Further warnings came from Richard Sorge

Richard Sorge (russian: Рихард Густавович Зорге, Rikhard Gustavovich Zorge; 4 October 1895 – 7 November 1944) was a German-Azerbaijani journalist and Soviet military intelligence officer who was active before and during Wo ...

, a Soviet spy in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and List of cities in Japan, largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, ...

working undercover as a German journalist who had penetrated deep into the German Embassy in Tokyo by seducing the wife of General Eugen Ott, the German ambassador to Japan.

Seven days before the invasion, a Soviet spy in Berlin, part of the ''Rote Kapelle'' (Red Orchestra) spy network, warned Stalin that the movement of German divisions to the borders was to wage war on the Soviet Union. Five days before the attack, Stalin received a report from a spy in the German Air Ministry that "all preparations by Germany for an armed attack on the Soviet Union have been completed, and the blow can be expected at any time." In the margin, Stalin wrote to the people's commissar for state security, "you can send your 'source' from the headquarters of German aviation to his mother. This is not a 'source' but a ''dezinformator.''" Although Stalin increased Soviet western border forces to 2.7 million men and ordered them to expect a possible German invasion, he did not order a full-scale mobilisation of forces to prepare for an attack. Stalin felt that a mobilization might provoke Hitler to prematurely begin to wage war against the Soviet Union, which Stalin wanted to delay until 1942 in order to strengthen Soviet forces.

In the initial hours after the German attack began, Stalin hesitated, wanting to ensure that the German attack was sanctioned by Hitler, rather than the unauthorized action of a rogue general.Simon Sebag Montefiore. ''Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar'', Knopf, 2004 () Accounts by

Seven days before the invasion, a Soviet spy in Berlin, part of the ''Rote Kapelle'' (Red Orchestra) spy network, warned Stalin that the movement of German divisions to the borders was to wage war on the Soviet Union. Five days before the attack, Stalin received a report from a spy in the German Air Ministry that "all preparations by Germany for an armed attack on the Soviet Union have been completed, and the blow can be expected at any time." In the margin, Stalin wrote to the people's commissar for state security, "you can send your 'source' from the headquarters of German aviation to his mother. This is not a 'source' but a ''dezinformator.''" Although Stalin increased Soviet western border forces to 2.7 million men and ordered them to expect a possible German invasion, he did not order a full-scale mobilisation of forces to prepare for an attack. Stalin felt that a mobilization might provoke Hitler to prematurely begin to wage war against the Soviet Union, which Stalin wanted to delay until 1942 in order to strengthen Soviet forces.

In the initial hours after the German attack began, Stalin hesitated, wanting to ensure that the German attack was sanctioned by Hitler, rather than the unauthorized action of a rogue general.Simon Sebag Montefiore. ''Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar'', Knopf, 2004 () Accounts by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

and Anastas Mikoyan claim that, after the invasion, Stalin retreated to his dacha

A dacha ( rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ') or shack serving as a family's main or only home, or an outbu ...

in despair for several days and did not participate in leadership decisions. But, some documentary evidence of orders given by Stalin contradicts these accounts, leading historians such as Roberts to speculate that Khrushchev's account is inaccurate.

Stalin soon quickly made himself a Marshal of the Soviet Union

Marshal of the Soviet Union (russian: Маршал Советского Союза, Marshal sovetskogo soyuza, ) was the highest military rank of the Soviet Union.

The rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union was created in 1935 and abolished in 19 ...

, then country's highest military rank and Supreme Commander in Chief of the Soviet Armed Forces

The Soviet Armed Forces, the Armed Forces of the Soviet Union and as the Red Army (, Вооружённые Силы Советского Союза), were the armed forces of the Russian SFSR (1917–1922), the Soviet Union (1922–1991), and th ...

aside from being Premier and General-Secretary of the ruling Communist Party of the Soviet Union that made him the leader of the nation, as well as the People's Commissar for Defence, which is equivalent to the U.S. Secretary of War at that time and the U.K. Minister of Defence and formed the State Defense Committee to coordinate military operations with himself also as chairman. He chaired the Stavka, the highest defense organisation of the country. Meanwhile, Marshal Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

was named to be the Deputy Supreme Commander in Chief of the Soviet Armed Forces.

In the first three weeks of the invasion, as the Soviet Union tried to defend itself against large German advances, it suffered 750,000 casualties, and lost 10,000 tanks and 4,000 aircraft. In July 1941, Stalin completely reorganized the Soviet military, placing himself directly in charge of several military organizations. This gave him complete control of his country's entire war effort; more control than any other leader in World War II.

A pattern soon emerged where Stalin embraced the

In the first three weeks of the invasion, as the Soviet Union tried to defend itself against large German advances, it suffered 750,000 casualties, and lost 10,000 tanks and 4,000 aircraft. In July 1941, Stalin completely reorganized the Soviet military, placing himself directly in charge of several military organizations. This gave him complete control of his country's entire war effort; more control than any other leader in World War II.

A pattern soon emerged where Stalin embraced the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

's strategy of conducting multiple offensives, while the Germans overran each of the resulting small, newly gained grounds, dealing the Soviets severe casualties. The most notable example of this was the Battle of Kiev, where over 600,000 Soviet troops were quickly killed, captured or missing.

By the end of 1941, the Soviet military had suffered 4.3 million casualties and the Germans had captured 3.0 million Soviet prisoners, 2.0 million of whom died in German captivity by February 1942. German forces had advanced c. 1,700 kilometres, and maintained a linearly-measured front of 3,000 kilometres. The Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

put up fierce resistance during the war's early stages. Even so, according to Glantz, they were plagued by an ineffective defence doctrine against well-trained and experienced German forces, despite possessing some modern Soviet equipment, such as the KV-1 and T-34

The T-34 is a Soviet medium tank introduced in 1940. When introduced its 76.2 mm (3 in) tank gun was less powerful than its contemporaries while its 60-degree sloped armour provided good protection against anti-tank weapons. The C ...

tanks.

Soviets stop the Germans

While the Germans made huge advances in 1941, killing millions of Soviet soldiers, at Stalin's direction the Red Army directed sizable resources to prevent the Germans from achieving one of their key strategic goals, the attempted capture of Leningrad. They held the city at the cost of more than a million Soviet soldiers in the region and more than a million civilians, many of whom died from starvation. While the Germans pressed forward, Stalin was confident of an eventual Allied victory over Germany. In September 1941, Stalin told British diplomats that he wanted two agreements: (1) a mutual assistance/aid pact and (2) a recognition that, after the war, the Soviet Union would gain the territories in countries that it had taken pursuant to its division of Eastern Europe with Hitler in theMolotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

. The British agreed to assistance but refused to agree to the territorial gains, which Stalin accepted months later as the military situation had deteriorated somewhat by mid-1942. On 6 November 1941, Stalin rallied his generals in a speech given underground in Moscow, telling them that the German ''blitzkrieg'' would fail because of weaknesses in the German rear in Nazi-occupied Europe and the underestimation of the strength of the Red Army, and that the German war effort would crumble against the Anglo-American-Soviet "war engine".

Correctly calculating that Hitler would direct efforts to capture Moscow, Stalin concentrated his forces to defend the city, including numerous divisions transferred from Soviet eastern sectors after he determined that Japan would not attempt an attack in those areas. By December, Hitler's troops had advanced to within of the Kremlin in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

. On 5 December, the Soviets launched a counteroffensive, pushing German troops back c. from Moscow in what was the first major defeat of the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

in the war.

In early 1942, the Soviets began a series of offensives labelled "Stalin's First Strategic Offensives". The counteroffensive bogged down, in part due to mud from rain in the spring of 1942. Stalin's attempt to retake Kharkov in the Ukraine ended in the disastrous encirclement of Soviet forces, with over 200,000 Soviet casualties suffered. Stalin attacked the competence of the generals involved. General

In early 1942, the Soviets began a series of offensives labelled "Stalin's First Strategic Offensives". The counteroffensive bogged down, in part due to mud from rain in the spring of 1942. Stalin's attempt to retake Kharkov in the Ukraine ended in the disastrous encirclement of Soviet forces, with over 200,000 Soviet casualties suffered. Stalin attacked the competence of the generals involved. General Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

and others subsequently revealed that some of those generals had wished to remain in a defensive posture in the region, but Stalin and others had pushed for the offensive. Some historians have doubted Zhukov's account.

At the same time, Hitler was worried about American popular support after the U.S. entry into the war following the

At the same time, Hitler was worried about American popular support after the U.S. entry into the war following the Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

, and a potential Anglo-American invasion on the Western Front in 1942 (which did not occur until the summer of 1944). He changed his primary goal from an immediate victory in the East, to the more long-term goal of securing the southern Soviet Union to protect oil fields vital to the long-term German war effort. While Red Army generals correctly judged the evidence that Hitler would shift his efforts south, Stalin thought it a flanking move in the German attempt to take Moscow.

The German southern campaign began with a push to capture the Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, which ended in disaster for the Red Army. Stalin publicly criticised his generals' leadership. In their southern campaigns, the Germans took 625,000 Red Army prisoners in July and August 1942 alone. At the same time, in a meeting in Moscow, Churchill privately told Stalin that the British and Americans were not yet prepared to make an amphibious landing against a fortified Nazi-held French coast in 1942, and would direct their efforts to invading German-held North Africa. He pledged a campaign of massive strategic bombing, to include German civilian targets.

Estimating that the Russians were "finished," the Germans began another southern operation in the autumn of 1942, the Battle of Stalingrad. Hitler insisted upon splitting German southern forces in a simultaneous siege of Stalingrad and an offensive against Baku on the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central Asia ...

. Stalin directed his generals to spare no effort to defend Stalingrad. Although the Soviets suffered in excess of more than 2 million casualties at Stalingrad, their victory over German forces, including the encirclement of 290,000 Axis troops, marked a turning point in the war.

Within a year after Barbarossa, Stalin reopened the churches in the Soviet Union. He may have wanted to motivate the majority of the population who had Christian beliefs. By changing the official policy of the party and the state towards religion, he could engage the Church and its clergy in mobilising the war effort. On 4 September 1943, Stalin invited the metropolitans Sergius, Alexy Alexy is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* A.J. Alexy (born 1998), American baseball player

* Gillian Alexy (born 1986), Australian actress

* Janko Alexy (1894–1970), Slovakian painter, writer, and publicist

* Robert Alexy ...

and Nikolay to the Kremlin. He proposed to reestablish the Moscow Patriarchate, which had been suspended since 1925, and elect the Patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and in certai ...

. On 8 September 1943, Metropolitan Sergius was elected Patriarch. One account said that Stalin's reversal followed a sign that he supposedly received from heaven.(Radzinsky 1996, p.472-3)

The ''Frontoviki''

Over 75% of Red Army divisions were listed as "rifle divisions" (as infantry divisions were known in the Red Army).Rottman, Gordon ''Soviet Rifleman 1941-45'', London: Osprey 2007 page 5. In the Imperial Russian Army, the ''strelkovye'' (rifle) divisions were considered more prestigious than ''pekhotnye'' (infantry) divisions, and in the Red Army, all infantry divisions were labeled ''strelkovye'' divisions. The Soviet rifleman was known as a ''peshkom'' ("on foot") or more frequently as a ''frontovik'' ( ru , фронтовик—front fighter; plural ru , фронтовики—''frontoviki''). The term ''frontovik'' was not equivalent to the German term ''Landser'', the American ''G.I Joe'' nor the British ''Tommy Atkins

Tommy Atkins (often just Tommy) is slang for a common soldier in the British Army. It was certainly well established during the nineteenth century, but is particularly associated with the First World War. It can be used as a term of reference ...

'', all of which referred to soldiers in general, as the term ''frontovik'' applied only to those infantrymen who fought at the front. All able-bodied males in the Soviet Union became eligible for conscription at the age of 19—those attending a university or a technical school were able to escape conscription, and even then could defer military service for a period ranging from 3 months to a year. Deferments could be only offered three times. The Soviet Union comprised 20 military districts, which corresponded with the borders of the ''oblasts'', and were further divided into ''raions'' (counties). The ''raions'' had assigned quotas specifying the number of men they had to produce for the Red Army every year. The vast majority of the ''frontoviks'' had been born in the 1920s and had grown up knowing nothing other than the Soviet system.Rottman, Gordon ''Soviet Rifleman 1941-45'', London: Osprey 2007 page 8. Every year, men received draft notices in the mail informing to report at a collection point, usually a local school, and customarily reported to duty with a bag or suitcase carrying some spare clothes, underwear, and tobacco. The conscripts then boarded a train to a military reception center where they were issued uniforms, underwent a physical test, had their heads shaven and were given a steam bath to rid them of lice. A typical soldier was given ammo pouches, shelter-cape, ration bag, cooking pot, water bottle and an identity tube containing papers listing pertinent personal information.

During training, conscripts woke up between 5 and 6 a.m.; training lasted for 10 to 12 hours—six days of the week.Rottman, Gordon ''Soviet Rifleman 1941-45'', London: Osprey 2007 page 10. Much of the training was done by rote and consisted of instruction. Before 1941 training had lasted for six months, but after the war, training was shorted to a few weeks. After finishing training, all men had to take the Oath of the Red Army which read: