The Southern Ocean, also known as the Antarctic Ocean, comprises the southernmost waters of the

World Ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the worl ...

, generally taken to be south of

60° S latitude and encircling

Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

.

With a size of , it is regarded as the second-smallest of the five principal oceanic divisions: smaller than the

Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

,

Atlantic, and

Indian oceans but larger than the

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

.

Over the past 30 years, the Southern Ocean has been subject to rapid climate change, which has led to changes in the marine ecosystem.

By way of his voyages in the 1770s,

James Cook proved that waters encompassed the southern latitudes of the globe. Since then, geographers have disagreed on the Southern Ocean's northern boundary or even existence, considering the waters as various parts of the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian oceans, instead. However, according to Commodore John Leech of the

International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), recent oceanographic research has discovered the importance of

Southern Circulation, and the term ''Southern Ocean'' has been used to define the body of water which lies south of the northern limit of that circulation. This remains the current official policy of the IHO, since a 2000 revision of its definitions including the Southern Ocean as the waters south of the 60th parallel has not yet been adopted. Others regard the seasonally-fluctuating

Antarctic Convergence

The Antarctic Convergence or Antarctic Polar Front is a marine belt encircling Antarctica, varying in latitude seasonally, where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the sub-Antarctic. Antarctic waters pr ...

as the natural boundary. This

oceanic zone

The oceanic zone is typically defined as the area of the ocean lying beyond the continental shelf (such as the Neritic zone), but operationally is often referred to as beginning where the water depths drop to below 200 meters (660 feet), seaward ...

is where cold, northward flowing waters from the Antarctic mix with warmer

Subantarctic

The sub-Antarctic zone is a region in the Southern Hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This translates roughly to a latitude of between 46° and 60° south of the Equator. The subantarctic region includes many islands ...

waters.

The maximum depth of the Southern Ocean, using the definition that it lies south of 60th parallel, was surveyed by the

Five Deeps Expedition in early February 2019. The expedition's multibeam sonar team identified the deepest point at 60° 28' 46"S, 025° 32' 32"W, with a depth of . The expedition leader and chief submersible pilot

Victor Vescovo

Victor Lance Vescovo (born 1966) is an American private equity investor, retired naval officer, space tourist and undersea explorer.

He is a co-founder and managing partner of private equity company Insight Equity Holdings. Vescovo achieved the ...

, has proposed naming this deepest point in the Southern Ocean the "Factorian Deep", based on the name of the crewed submersible

''DSV Limiting Factor'', in which he successfully visited the bottom for the first time on February 3, 2019.

Definitions and use

Borders and names for oceans and seas were internationally agreed when the

International Hydrographic Bureau

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) is an intergovernmental organisation representing hydrography. , the IHO comprised 98 Member States.

A principal aim of the IHO is to ensure that the world's seas, oceans and navigable waters a ...

, the precursor to the IHO, convened the First International Conference on 24 July 1919. The IHO then published these in its ''Limits of Oceans and Seas'', the first edition being 1928. Since the first edition, the limits of the Southern Ocean have moved progressively southwards; since 1953, it has been omitted from the official publication and left to local hydrographic offices to determine their own limits.

The IHO included the ocean and its definition as the waters south of the

60th parallel south in its 2000 revisions, but this has not been formally adopted, due to continuing impasses about some of the content, such as the

naming dispute over the

Sea of Japan. The 2000 IHO definition, however, was circulated in a draft edition in 2002, and is used by some within the IHO and by some other organizations such as the ''

CIA World Factbook'' and

Merriam-Webster.

The Australian Government regards the Southern Ocean as lying immediately south of Australia (see ).

The

National Geographic Society recognized the ocean officially in June 2021.

Prior to this, it depicted it in a typeface different from the other world oceans; instead, it shows the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans extending to Antarctica on both its print and online maps.

Map publishers using the term Southern Ocean on their maps include Hema Maps

and GeoNova.

Pre-20th century

"Southern Ocean" is an obsolete name for the Pacific Ocean or South Pacific, coined by

Vasco Núñez de Balboa

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (; c. 1475around January 12–21, 1519) was a Spanish explorer, governor, and conquistador. He is best known for having crossed the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean in 1513, becoming the first European to lead an ...

, the first European to discover it, who approached it from the north. The "South Seas" is a less archaic synonym. A 1745 British

Act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the Legislature, legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of ...

established a prize for discovering a

Northwest Passage to "the Western and Southern Ocean of ''America''".

Authors using "Southern Ocean" to name the waters encircling the unknown southern polar regions used varying limits.

James Cook's account of

his second voyage implies

New Caledonia borders it.

Peacock's 1795 ''Geographical Dictionary'' said it lay "to the southward of America and Africa"; John Payne in 1796 used 40 degrees as the northern limit;

the 1827 ''Edinburgh Gazetteer'' used 50 degrees. The ''Family Magazine'' in 1835 divided the "Great Southern Ocean" into the "Southern Ocean" and the "Antarctick

'sic''Ocean" along the Antarctic Circle, with the northern limit of the Southern Ocean being lines joining Cape Horn, the Cape of Good Hope, Van Diemen's Land and the south of New Zealand.

The United Kingdom's ''

South Australia Act 1834'' described the waters forming the southern limit of the new province of

South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

as "the Southern Ocean". The

Colony of Victoria

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

's ''Legislative Council Act 1881'' delimited part of the division of

Bairnsdale

Bairnsdale () ( Ganai: ''Wy-yung'') is a city in East Gippsland, Victoria, Australia in a region traditionally owned by the Tatungalung clan of the Gunaikurnai people.

The estimated population of Bairnsdale urban area was 15,411 at Ju ...

as "along the

New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

boundary to the Southern ocean".

1928 delineation

In the 1928 first edition of ''Limits of Oceans and Seas'', the Southern Ocean was delineated by land-based limits: Antarctica to the south, and South America, Africa, Australia, and

Broughton Island, New Zealand

Broughton Island is the second largest island of The Snares, at . It sits just off the South Promontory of the main island North East Island, which itself lies approximately south of New Zealand's South Island.

The island is some in size, wi ...

to the north.

The detailed land-limits used were from

Cape Horn in Chile eastwards to

Cape Agulhas

Cape Agulhas (; pt, Cabo das Agulhas , "Cape of the Needles") is a rocky headland in Western Cape, South Africa.

It is the geographic southern tip of the African continent and the beginning of the dividing line between the Atlantic and Indian ...

in Africa, then further eastwards to the southern coast of mainland Australia to

Cape Leeuwin,

Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

. From Cape Leeuwin, the limit then followed eastwards along the coast of mainland Australia to

Cape Otway

Cape Otway is a cape and a bounded locality of the Colac Otway Shire in southern Victoria, Australia on the Great Ocean Road; much of the area is enclosed in the Great Otway National Park.

History

Cape Otway was originally inhabited by the Gadu ...

,

Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, then southwards across

Bass Strait to

Cape Wickham,

King Island, along the west coast of King Island, then the remainder of the way south across Bass Strait to

Cape Grim

Cape Grim, officially Kennaook / Cape Grim, is the northwestern point of Tasmania, Australia. The Peerapper name for the cape is recorded as ''Kennaook''.

It is the location of the Cape Grim Baseline Air Pollution Station and of the Cape Gri ...

,

Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

.

The limit then followed the west coast of Tasmania southwards to the

South East Cape

The South East Cape is a cape located at the southernmost point of the main island of Tasmania, the southernmost state of Australia. The cape is situated in the southern and south-eastern corner of the Southwest National Park, part of the Tasma ...

and then went eastwards to Broughton Island, New Zealand, before returning to Cape Horn.

1937 delineation

The northern limits of the Southern Ocean were moved southwards in the IHO's 1937 second edition of the ''Limits of Oceans and Seas''. From this edition, much of the ocean's northern limit ceased to abut land masses.

In the second edition, the Southern Ocean then extended from Antarctica northwards to latitude 40°S between

Cape Agulhas

Cape Agulhas (; pt, Cabo das Agulhas , "Cape of the Needles") is a rocky headland in Western Cape, South Africa.

It is the geographic southern tip of the African continent and the beginning of the dividing line between the Atlantic and Indian ...

in Africa (long. 20°E) and

Cape Leeuwin in Western Australia (long. 115°E), and extended to latitude 55°S between

Auckland Island

Auckland Island ( mi, Mauka Huka) is the main island of the eponymous uninhabited archipelago in the Pacific Ocean. It is part of the New Zealand subantarctic area. It is inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage list together with the other New ...

of New Zealand (165 or 166°E east) and

Cape Horn in South America (67°W).

As is discussed in more detail below, prior to the 2002 edition the limits of oceans explicitly excluded the seas lying within each of them. The

Great Australian Bight

The Great Australian Bight is a large oceanic bight, or open bay, off the central and western portions of the southern coastline of mainland Australia.

Extent

Two definitions of the extent are in use – one used by the International Hydrog ...

was unnamed in the 1928 edition, and delineated as shown in the figure above in the 1937 edition. It therefore encompassed former Southern Ocean waters—as designated in 1928—but was technically not inside any of the three adjacent oceans by 1937.

In the 2002 draft edition, the IHO have designated 'seas' as being subdivisions within 'oceans', so the Bight would have still been within the Southern Ocean in 1937 if the 2002 convention were in place then. To perform direct comparisons of current and former limits of oceans it is necessary to consider, or at least be aware of, how the 2002 change in IHO terminology for 'seas' can affect the comparison.

1953 delineation

The Southern Ocean did not appear in the 1953 third edition of ''Limits of Oceans and Seas'', a note in the publication read:

Instead, in the IHO 1953 publication, the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans were extended southward, the Indian and Pacific Oceans (which had not previously touched pre 1953, as per the first and second editions) now abutted at the meridian of

South East Cape

The South East Cape is a cape located at the southernmost point of the main island of Tasmania, the southernmost state of Australia. The cape is situated in the southern and south-eastern corner of the Southwest National Park, part of the Tasma ...

, and the southern limits of the

Great Australian Bight

The Great Australian Bight is a large oceanic bight, or open bay, off the central and western portions of the southern coastline of mainland Australia.

Extent

Two definitions of the extent are in use – one used by the International Hydrog ...

and the

Tasman Sea were moved northwards.

Alternate location

AWI

(DOI 10013/epic.37175.d00

scanarchived

.

2002 draft delineation

The IHO readdressed the question of the Southern Ocean in a survey in 2000. Of its 68 member nations, 28 responded, and all responding members except Argentina agreed to redefine the ocean, reflecting the importance placed by oceanographers on ocean currents. The proposal for the name ''Southern Ocean'' won 18 votes, beating the alternative ''Antarctic Ocean''. Half of the votes supported a definition of the ocean's northern limit at the

60th parallel south—with no land interruptions at this latitude—with the other 14 votes cast for other definitions, mostly the

50th parallel south, but a few for as far north as the

35th parallel south. Notably the

Southern Ocean Observing System collates data from latitudes higher than 40 degrees south.

A draft fourth edition of ''Limits of Oceans and Seas'' was circulated to IHO member states in August 2002 (sometimes referred to as the "2000 edition" as it summarized the progress to 2000).

It has yet to be published due to 'areas of concern' by several countries relating to various naming issues around the world – primarily the

Sea of Japan naming dispute – and there have been various changes, 60 seas were given new names, and even the name of the publication was changed. A reservation had also been lodged by Australia regarding the Southern Ocean limits. Effectively, the third edition—which did not delineate the Southern Ocean leaving delineation to local hydrographic offices—has yet to be superseded.

Despite this, the fourth edition definition has partial ''de facto'' usage by many nations, scientists, and organisations such as the U.S. (the ''

CIA World Factbook'' uses "Southern Ocean", but none of the other new sea names within the "Southern Ocean", such as the "

Cosmonauts Sea") and

Merriam-Webster,

[ scientists and nations – and even by some within the IHO. Some nations' hydrographic offices have defined their own boundaries; the United Kingdom used the ]55th parallel south

The 55th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 55 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Pacific Ocean and South America.

At this latitude the sun is visible for 17 hours, ...

for example.Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' describes the Southern Ocean as extending as far north as South America, and confers great significance on the Antarctic Convergence

The Antarctic Convergence or Antarctic Polar Front is a marine belt encircling Antarctica, varying in latitude seasonally, where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the sub-Antarctic. Antarctic waters pr ...

, yet its description of the Indian Ocean contradicts this, describing the Indian Ocean as extending south to Antarctica.Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

, and Indian oceans as extending to Antarctica on its maps, although articles on the National Geographic web site have begun to reference the Southern Ocean.[

A radical shift from past IHO practices (1928–1953) was also seen in the 2002 draft edition when the IHO delineated 'seas' as being subdivisions that lay within the boundaries of 'oceans'. While the IHO are often considered the authority for such conventions, the shift brought them into line with the practices of other publications (e.g. the CIA ''World Fact Book'') which already adopted the principle that seas are contained within oceans. This difference in practice is markedly seen for the Pacific Ocean in the adjacent figure. Thus, for example, previously the Tasman Sea between Australia and New Zealand was not regarded by the IHO as being part of the Pacific, but as of the 2002 draft edition it is.

The new delineation of seas being subdivisions of oceans has avoided the need to interrupt the northern boundary of the Southern Ocean where intersected by ]Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

which includes all of the waters from South America to the Antarctic coast, nor interrupt it for the Scotia Sea

The Scotia Sea is a sea located at the northern edge of the Southern Ocean at its boundary with the South Atlantic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Drake Passage and on the north, east, and south by the Scotia Arc, an undersea ridge and ...

, which also extends below the 60th parallel south. The new delineation of seas has also meant that the long-time named seas around Antarctica, excluded from the 1953 edition (the 1953 map did not even extend that far south), are 'automatically' part of the Southern Ocean.

Australian standpoint

In Australia, cartographical

Cartography (; from grc, χάρτης , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an im ...

authorities define the Southern Ocean as including the entire body of water between Antarctica and the south coasts of Australia and New Zealand, and up to 60°S elsewhere.Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

and South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

label the sea areas as ''Southern Ocean'' and Cape Leeuwin in Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

is described as the point where the Indian and Southern Oceans meet.

History of exploration

Unknown southern land

Exploration of the Southern Ocean was inspired by a belief in the existence of a ''Terra Australis'' – a vast continent in the far south of the globe to "balance" the northern lands of Eurasia and North Africa – which had existed since the times of Ptolemy. The rounding of the Cape of Good Hope in 1487 by Bartolomeu Dias first brought explorers within touch of the Antarctic cold, and proved that there was an ocean separating Africa from any Antarctic land that might exist.

Exploration of the Southern Ocean was inspired by a belief in the existence of a ''Terra Australis'' – a vast continent in the far south of the globe to "balance" the northern lands of Eurasia and North Africa – which had existed since the times of Ptolemy. The rounding of the Cape of Good Hope in 1487 by Bartolomeu Dias first brought explorers within touch of the Antarctic cold, and proved that there was an ocean separating Africa from any Antarctic land that might exist.Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the Eas ...

, who passed through the Strait of Magellan in 1520, assumed that the islands of Tierra del Fuego to the south were an extension of this unknown southern land. In 1564, Abraham Ortelius published his first map, ''Typus Orbis Terrarum'', an eight-leaved wall map of the world, on which he identified the '' Regio Patalis'' with ''Locach Lochac, Locach or Locat is a country far south of China mentioned by Marco Polo. The name is widely believed to be a variant of ''Lo-huk'' 罗斛: the Cantonese name for the southern Thai kingdom of Lopburi (also known as Lavapura and Louvo), whic ...

'' as a northward extension of the ''Terra Australis

(Latin: '"Southern Land'") was a hypothetical continent first posited in antiquity and which appeared on maps between the 15th and 18th centuries. Its existence was not based on any survey or direct observation, but rather on the idea that ...

'', reaching as far as New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

.[Joost Depuydt, ‘]Ortelius, Abraham

Abraham Ortelius (; also Ortels, Orthellius, Wortels; 4 or 14 April 152728 June 1598) was a Brabantian cartographer, geographer, and cosmographer, conventionally recognized as the creator of the first modern atlas, the ''Theatrum Orbis Terrarum ...

(1527–1598)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

European geographers continued to connect the coast of Tierra del Fuego with the coast of New Guinea on their globes, and allowing their imaginations to run riot in the vast unknown spaces of the south Atlantic, south Indian and Pacific oceans they sketched the outlines of the ''Terra Australis Incognita'' ("Unknown Southern Land"), a vast continent stretching in parts into the tropics. The search for this great south land was a leading motive of explorers in the 16th and the early part of the 17th centuries.Spaniard

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both i ...

Gabriel de Castilla

Gabriel de Castilla (1577 – c. 1620) was a Spanish explorer and navigator. A native of Palencia, it has been argued that he was an early explorer of Antarctica.Vázquez de Acuña, Isidoro. ''Don Gabriel de Castilla primer avistador de la An ...

, who claimed having sighted "snow-covered mountains" beyond the 64° S in 1603, is recognized as the first explorer that discovered the continent of Antarctica, although he was ignored in his time.

In 1606, Pedro Fernández de Quirós

Pedro is a masculine given name. Pedro is the Spanish, Portuguese, and Galician name for '' Peter''. Its French equivalent is Pierre while its English and Germanic form is Peter.

The counterpart patronymic surname of the name Pedro, meaning ...

took possession for the king of Spain all of the lands he had discovered in Australia del Espiritu Santo (the New Hebrides) and those he would discover "even to the Pole".Jacob Le Maire

Jacob Le Maire (c. 1585 – 22 December 1616) was a Dutch mariner who circumnavigated the earth in 1615 and 1616. The strait between Tierra del Fuego and Isla de los Estados was named the Le Maire Strait in his honour, though not without controver ...

discovered the southern extremity of Tierra del Fuego and named it Cape Horn in 1615, they proved that the Tierra del Fuego archipelago was of small extent and not connected to the southern land, as previously thought. Subsequently, in 1642, Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New ...

showed that even New Holland (Australia)

''New Holland'' ( nl, Nieuw-Holland) is a historical European name for mainland Australia.

The name was first applied to Australia in 1644 by the Dutch seafarer Abel Tasman. The name came for a time to be applied in most European maps to the ...

was separated by sea from any continuous southern continent.

South of the Antarctic Convergence

The visit to South Georgia by Anthony de la Roché

Anthony de la Roché (spelled also ''Antoine de la Roché'', ''Antonio de la Roché'' or ''Antonio de la Roca'' in some sources) was a 17th-century English merchant born in London to a French Huguenot father and an English mother. During a c ...

in 1675 was the first-ever discovery of land south of the Antarctic Convergence

The Antarctic Convergence or Antarctic Polar Front is a marine belt encircling Antarctica, varying in latitude seasonally, where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the sub-Antarctic. Antarctic waters pr ...

, i.e. in the Southern Ocean/Antarctic. Soon after the voyage cartographers started to depict " Roché Island", honouring the discoverer. James Cook was aware of la Roché's discovery when surveying and mapping the island in 1775.

Edmond Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, H ...

's voyage in for magnetic investigations in the South Atlantic met the pack ice in 52° S in January 1700, but that latitude (he reached off the north coast of South Georgia) was his farthest south. A determined effort on the part of the French naval officer Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier

Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier (14 January 1705 – 1786) was a French sailor, explorer, and governor of the Mascarene Islands.

He was orphaned at the age of seven and after being educated in Paris, he was sent to Saint Malo to study n ...

to discover the "South Land" – described by a half legendary " sieur de Gonneyville" – resulted in the discovery of Bouvet Island

Bouvet Island ( ; or ''Bouvetøyen'') is an island claimed by Norway, and declared an uninhabited protected nature reserve. It is a subantarctic volcanic island, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic R ...

in 54°10′ S, and in the navigation of 48° of longitude of ice-cumbered sea nearly in 55° S in 1730.France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

with instructions to proceed south from Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label= Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It ...

in search of "a very large continent". He lighted upon a land in 50° S which he called South France, and believed to be the central mass of the southern continent. He was sent out again to complete the exploration of the new land, and found it to be only an inhospitable island which he renamed the Isle of Desolation, but which was ultimately named after him.

South of the Antarctic Circle

The obsession of the undiscovered continent culminated in the brain of

The obsession of the undiscovered continent culminated in the brain of Alexander Dalrymple

Alexander Dalrymple FRS (24 July 1737 – 19 June 1808) was a Scottish geographer and the first Hydrographer of the British Admiralty. He was the main proponent of the theory that there existed a vast undiscovered continent in the South P ...

, the brilliant and erratic hydrographer who was nominated by the Royal Society to command the Transit of Venus expedition to Tahiti in 1769. The command of the expedition was given by the admiralty to Captain James Cook. Sailing in 1772 with ''Resolution'', a vessel of 462 tons under his own command and ''Adventure'' of 336 tons under Captain Tobias Furneaux

Captain Tobias Furneaux (21 August 173518 September 1781) was an English navigator and Royal Navy officer, who accompanied James Cook on his second voyage of exploration. He was one of the first men to circumnavigate the world in both directions ...

, Cook first searched in vain for Bouvet Island

Bouvet Island ( ; or ''Bouvetøyen'') is an island claimed by Norway, and declared an uninhabited protected nature reserve. It is a subantarctic volcanic island, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic R ...

, then sailed for 20 degrees of longitude to the westward in latitude 58° S, and then 30° eastward for the most part south of 60° S, a lower southern latitude than had ever been voluntarily entered before by any vessel. On 17 January 1773 the Antarctic Circle was crossed for the first time in history and the two ships reached by , where their course was stopped by ice. Cook then turned northward to look for French Southern and Antarctic Lands, of the discovery of which he had received news at

Cook then turned northward to look for French Southern and Antarctic Lands, of the discovery of which he had received news at Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, but from the rough determination of his longitude by Kerguelen, Cook reached the assigned latitude 10° too far east and did not see it. He turned south again and was stopped by ice in by 95° E and continued eastward nearly on the parallel of 60° S to 147° E. On 16 March, the approaching winter drove him northward for rest to New Zealand and the tropical islands of the Pacific. In November 1773, Cook left New Zealand, having parted company with the ''Adventure'', and reached 60° S by 177° W, whence he sailed eastward keeping as far south as the floating ice allowed. The Antarctic Circle was crossed on 20 December and Cook remained south of it for three days, being compelled after reaching to stand north again in 135° W.South Sandwich Islands

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type =

, song =

, image_map = South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in United Kingdom.svg

, map_caption = Location of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic Oce ...

(named ''Sandwich Land'' by him), the only ice-clad land he had seen, before crossing the South Atlantic to the Cape of Good Hope between 55° and 60°. He thereby laid open the way for future Antarctic exploration by exploding the myth of a habitable southern continent. Cook's most southerly discovery of land lay on the temperate side of the 60th parallel, and he convinced himself that if land lay farther south it was practically inaccessible and without economic value.longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek lette ...

34°16'45″ W the southernmost position any ship had ever reached up to that time. A few icebergs were sighted but there was still no sight of land, leading Weddell to theorize that the sea continued as far as the South Pole. Another two days' sailing would have brought him to Coat's Land (to the east of the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

) but Weddell decided to turn back.

First sighting of land

The first land south of the parallel 60° south latitude was discovered by the

The first land south of the parallel 60° south latitude was discovered by the Englishman

The English people are an ethnic group and nation native to England, who speak the English language, a West Germanic language, and share a common history and culture. The English identity is of Anglo-Saxon origin, when they were known in ...

William Smith, who sighted Livingston Island

Livingston Island (Russian name ''Smolensk'', ) is an Antarctic island in the Southern Ocean, part of the South Shetlands Archipelago, a group of Antarctic islands north of the Antarctic Peninsula. It was the first land discovered south of 60 ...

on 19 February 1819. A few months later Smith returned to explore the other islands of the South Shetlands archipelago, landed on King George Island, and claimed the new territories for Britain.

In the meantime, the Spanish Navy ship ''San Telmo

San Telmo ("Saint Pedro González Telmo") is the oldest ''barrio'' (neighborhood) of Buenos Aires, Argentina. It is a well-preserved area of the Argentine metropolis and is characterized by its colonial buildings. Cafes, tango parlors and antiqu ...

'' sank in September 1819 when trying to cross Cape Horn. Parts of her wreckage were found months later by sealers on the north coast of Livingston Island

Livingston Island (Russian name ''Smolensk'', ) is an Antarctic island in the Southern Ocean, part of the South Shetlands Archipelago, a group of Antarctic islands north of the Antarctic Peninsula. It was the first land discovered south of 60 ...

( South Shetlands). It is unknown if some survivor managed to be the first to set foot on these Antarctic islands.

The first confirmed sighting of mainland Antarctica cannot be accurately attributed to one single person. It can, however, be narrowed down to three individuals. According to various sources, three men all sighted the ice shelf or the continent within days or months of each other: Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen

Fabian Gottlieb Thaddeus von Bellingshausen (russian: Фадде́й Фадде́евич Беллинсга́узен, translit=Faddéy Faddéevich Bellinsgáuzen; – ) was a Russian naval officer, cartographer and explorer, who ultimatel ...

, a captain in the Russian Imperial Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

; Edward Bransfield

Edward Bransfield (c. 1785 – 31 October 1852) was an Irish sailor who became an officer in the British Royal Navy, serving as a master on several ships, after being impressed into service in Ireland at the age of 18. He is noted for his par ...

, a captain in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

; and Nathaniel Palmer

Nathaniel Brown Palmer (August 8, 1799June 21, 1877) was an American seal hunter, explorer, sailing captain, and ship designer. He gave his name to Palmer Land, Antarctica, which he explored in 1820 on his sloop ''Hero''. He was born in Stonin ...

, an American sailor out of Stonington, Connecticut. It is certain that the expedition, led by von Bellingshausen and Lazarev on the ships ''Vostok'' and ''Mirny'', reached a point within from Princess Martha Coast

Princess Martha Coast ( no, Kronprinsesse Märtha Kyst) is that portion of the coast of Queen Maud Land lying between 05° E and the terminus of Stancomb-Wills Glacier, at 20° W. The entire coastline is bounded by ice shelves with ice cliffs ...

and recorded the sight of an ice shelf at

Antarctic expeditions

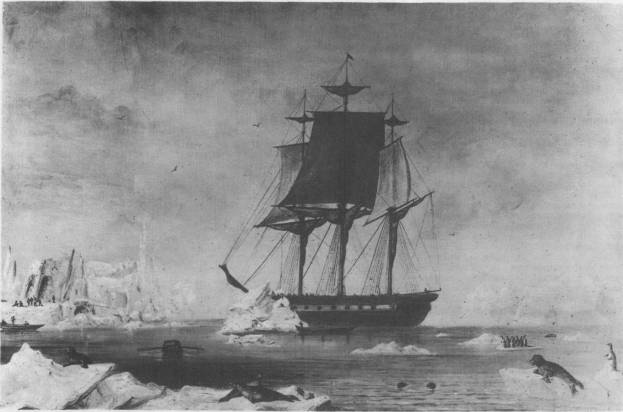

In December 1839, as part of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–42 conducted by the

In December 1839, as part of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–42 conducted by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

(sometimes called "the Wilkes Expedition"), an expedition sailed from Sydney, Australia, on the sloops-of-war and , the brig , the full-rigged ship , and two schooners and . They sailed into the Antarctic Ocean, as it was then known, and reported the discovery "of an Antarctic continent west of the Balleny Islands" on 25 January 1840. That part of Antarctica was later named " Wilkes Land", a name it maintains to this day.

Explorer James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

passed through what is now known as the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

and discovered Ross Island (both of which were named for him) in 1841. He sailed along a huge wall of ice that was later named the Ross Ice Shelf. Mount Erebus and Mount Terror are named after two ships from his expedition: and .

The

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917 is considered to be the last major expedition of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration. Conceived by Sir Ernest Shackleton, the expedition was an attempt to make the first land crossing ...

of 1914, led by Ernest Shackleton, set out to cross the continent via the pole, but their ship, , was trapped and crushed by pack ice before they even landed. The expedition members survived after an epic journey on sledges over pack ice to Elephant Island

Elephant Island is an ice-covered, mountainous island off the coast of Antarctica in the outer reaches of the South Shetland Islands, in the Southern Ocean. The island is situated north-northeast of the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, west-so ...

. Then Shackleton and five others crossed the Southern Ocean, in an open boat called ''James Caird'', and then trekked over South Georgia to raise the alarm at the whaling station Grytviken.

In 1946, US Navy Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd

Richard Evelyn Byrd Jr. (October 25, 1888 – March 11, 1957) was an American naval officer and explorer. He was a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest honor for valor given by the United States, and was a pioneering American aviator, p ...

and more than 4,700 military personnel visited the Antarctic in an expedition called Operation Highjump. Reported to the public as a scientific mission, the details were kept secret and it may have actually been a training or testing mission for the military. The expedition was, in both military or scientific planning terms, put together very quickly. The group contained an unusually high amount of military equipment, including an aircraft carrier, submarines, military support ships, assault troops and military vehicles. The expedition was planned to last for eight months but was unexpectedly terminated after only two months. With the exception of some eccentric entries in Admiral Byrd's diaries, no real explanation for the early termination has ever been officially given.

Captain Finn Ronne, Byrd's executive officer, returned to Antarctica with his own expedition in 1947–1948, with Navy support, three planes, and dogs. Ronne disproved the notion that the continent was divided in two and established that East and West Antarctica was one single continent, i.e. that the Weddell Sea and the Ross Sea are not connected. The expedition explored and mapped large parts of Palmer Land and the Weddell Sea coastline, and identified the Ronne Ice Shelf, named by Ronne after his wife Edith "Jackie" Ronne. Ronne covered by ski and dog sled – more than any other explorer in history. The Ronne Antarctic Research Expedition discovered and mapped the last unknown coastline in the world and was the first Antarctic expedition to ever include women.

Recent history

The

The Antarctic Treaty

russian: link=no, Договор об Антарктике es, link=no, Tratado Antártico

, name = Antarctic Treaty System

, image = Flag of the Antarctic Treaty.svgborder

, image_width = 180px

, caption ...

was signed on 1 December 1959 and came into force on 23 June 1961. Among other provisions, this treaty limits military activity in the Antarctic to the support of scientific research.

The first person to sail single-handed to Antarctica was the New Zealander David Henry Lewis, in 1972, in a steel sloop ''Ice Bird''.

A baby, named Emilio Marcos de Palma, was born near Hope Bay

Hope Bay (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Bahía Esperanza'') on Trinity Peninsula, is long and wide, indenting the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula and opening on Antarctic Sound. It is the site of the Argentinian Antarctic settlement Esperanza Ba ...

on 7 January 1978, becoming the first baby born on the continent. He also was born further south than anyone in history.

The was a cruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports-of-call, where passengers may go on tours known as ...

operated by the Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

explorer Lars-Eric Lindblad. Observers point to ''Explorers 1969 expeditionary cruise to Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

as the frontrunner for today's sea-based tourism in that region. ''Explorer'' was the first cruise ship used specifically to sail the icy waters of the Antarctic Ocean and the first to sink there when she struck an unidentified submerged object on 23 November 2007, reported to be ice, which caused a gash in the hull.South Shetland Islands

The South Shetland Islands are a group of Antarctic islands with a total area of . They lie about north of the Antarctic Peninsula, and between southwest of the nearest point of the South Orkney Islands. By the Antarctic Treaty of 1 ...

in the Southern Ocean, an area which is usually stormy but was calm at the time. ''Explorer'' was confirmed by the Chilean Navy

The Chilean Navy ( es, Armada de Chile) is the naval warfare service branch of the Chilean Armed Forces. It is under the Ministry of National Defense. Its headquarters are at Edificio Armada de Chile, Valparaiso.

History

Origins and the War ...

to have sunk at approximately position: 62° 24′ South, 57° 16′ West, in roughly 600 m of water.

British engineer Richard Jenkins designed an unmanned "saildrone" that completed the first autonomous circumnavigation of the Southern Ocean on 3 August 2019 after 196 days at sea.

The first completely human-powered expedition on the Southern Ocean was accomplished on 25 December 2019 by a team of rowers comprising captain Fiann Paul (Iceland), first mate Colin O'Brady (US), Andrew Towne (US), Cameron Bellamy (South Africa), Jamie Douglas-Hamilton (UK) and John Petersen (US).

Geography

The Southern Ocean, geologically the youngest of the oceans, was formed when Antarctica and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

moved apart, opening the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

, roughly 30 million years ago. The separation of the continents allowed the formation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

With a northern limit at 60°S, the Southern Ocean differs from the other oceans in that its largest boundary, the northern boundary, does not abut a landmass (as it did with the first edition of ''Limits of Oceans and Seas''). Instead, the northern limit is with the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans.

One reason for considering it as a separate ocean stems from the fact that much of the water of the Southern Ocean differs from the water in the other oceans. Water gets transported around the Southern Ocean fairly rapidly because of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current which circulates around Antarctica. Water in the Southern Ocean south of, for example, New Zealand, resembles the water in the Southern Ocean south of South America more closely than it resembles the water in the Pacific Ocean.

The Southern Ocean has typical depths of between over most of its extent with only limited areas of shallow water. The Southern Ocean's greatest depth of occurs at the southern end of the South Sandwich Trench

The South Sandwich Trench is a deep arcuate trench in the South Atlantic Ocean lying to the east of the South Sandwich Islands. It is the deepest trench of the Southern Atlantic Ocean, and the second deepest of the Atlantic Ocean after the Puert ...

, at 60°00'S, 024°W. The Antarctic continental shelf appears generally narrow and unusually deep, its edge lying at depths up to , compared to a global mean of .

Equinox

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun crosses the Earth's equator, which is to say, appears directly above the equator, rather than north or south of the equator. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise "due east" and se ...

to equinox in line with the sun's seasonal influence, the Antarctic ice pack fluctuates from an average minimum of in March to about in September, more than a sevenfold increase in area.

Sub-divisions of the Southern Ocean

Sub-divisions of oceans are geographical features such as "seas", "straits", "bays", "channels", and "gulfs". There are many sub-divisions of the Southern Ocean defined in the never-approved 2002 draft fourth edition of the IHO publication ''Limits of Oceans and Seas''. In clockwise order these include (with sector):

*

Sub-divisions of oceans are geographical features such as "seas", "straits", "bays", "channels", and "gulfs". There are many sub-divisions of the Southern Ocean defined in the never-approved 2002 draft fourth edition of the IHO publication ''Limits of Oceans and Seas''. In clockwise order these include (with sector):

* Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

(57°18'W – 12°16'E)

* King Haakon VII Sea (20°W – 45°E)

* Lazarev Sea (0° – 14°E)

* Riiser-Larsen Sea (14° – 30°E)

* Cosmonauts Sea (30° – 50°E)

* Cooperation Sea (59°34' – 85°E)

* Davis Sea (82° – 96°E)

* Mawson Sea (95°45' – 113°E)

* Dumont D'Urville Sea (140°E)

* Somov Sea (150° – 170°E)

* Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

(166°E – 155°W)

* Amundsen Sea (102°20′ – 126°W)

* Bellingshausen Sea (57°18' – 102°20'W)

* Part of the Drake Passage

The Drake Passage (referred to as Mar de Hoces Hoces Sea"in Spanish-speaking countries) is the body of water between South America's Cape Horn, Chile and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It connects the southwestern part of the Atla ...

(54° – 68°W)

* Bransfield Strait

Bransfield Strait or Fleet Sea ( es, Estrecho de Bransfield, Mar de la Flota) is a body of water about wide extending for in a general northeast – southwest direction between the South Shetland Islands and the Antarctic Peninsula.

History ...

(54° – 62°W)

* Part of the Scotia Sea

The Scotia Sea is a sea located at the northern edge of the Southern Ocean at its boundary with the South Atlantic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Drake Passage and on the north, east, and south by the Scotia Arc, an undersea ridge and ...

(26°30' – 65°W)

A number of these such as the 2002 Russian-proposed "Cosmonauts Sea", "Cooperation Sea", and "Somov (mid-1950s Russian polar explorer) Sea" are not included in the 1953 IHO document which remains currently in force,Times Atlas of the World

''The Times Atlas of the World'', rebranded ''The Times Atlas of the World: Comprehensive Edition'' in its 11th edition and ''The Times Comprehensive Atlas of the World'' from its 12th edition, is a world atlas currently published by HarperCo ...

, but Soviet and Russian-issued maps do.

Biggest seas in Southern Ocean

Top large seas:

# Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

–

# Somov Sea –

# Riiser-Larsen Sea –

# Lazarev Sea –

# Scotia Sea

The Scotia Sea is a sea located at the northern edge of the Southern Ocean at its boundary with the South Atlantic Ocean. It is bounded on the west by the Drake Passage and on the north, east, and south by the Scotia Arc, an undersea ridge and ...

–

# Cosmonauts Sea –

# Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

–

# Bellingshausen Sea –

# Mawson Sea –

# Cooperation Sea –

# Amundsen Sea –

# Davis Sea –

# D'Urville Sea

# King Haakon VII Sea

Natural resources

The Southern Ocean probably contains large, and possibly giant,

The Southern Ocean probably contains large, and possibly giant, oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

and gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

fields on the continental margin

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges. The continental margi ...

. Placer deposit

In geology, a placer deposit or placer is an accumulation of valuable minerals formed by gravity separation from a specific source rock during sedimentary processes. The name is from the Spanish word ''placer'', meaning "alluvial sand". Placer mi ...

s, accumulation of valuable minerals such as gold, formed by gravity separation during sedimentary processes are also expected to exist in the Southern Ocean.Manganese nodules

Polymetallic nodules, also called manganese nodules, are mineral concretions on the sea bottom formed of concentric layers of iron and manganese hydroxides around a core. As nodules can be found in vast quantities, and contain valuable metals, de ...

are expected to exist in the Southern Ocean. Manganese nodules are rock concretion

A concretion is a hard, compact mass of matter formed by the precipitation of mineral cement within the spaces between particles, and is found in sedimentary rock or soil. Concretions are often ovoid or spherical in shape, although irregular ...

s on the sea bottom formed of concentric layers of iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

and manganese

Manganese is a chemical element with the symbol Mn and atomic number 25. It is a hard, brittle, silvery metal, often found in minerals in combination with iron. Manganese is a transition metal with a multifaceted array of industrial alloy use ...

hydroxides around a core. The core may be microscopically small and is sometimes completely transformed into manganese minerals by crystallization. Interest in the potential exploitation of polymetallic nodules generated a great deal of activity among prospective mining consortia in the 1960s and 1970s.

Natural hazards

Icebergs can occur at any time of year throughout the ocean. Some may have drafts up to several hundred meters; smaller icebergs, iceberg fragments and sea-ice (generally 0.5 to 1 m thick) also pose problems for ships. The deep continental shelf has a floor of glacial deposits varying widely over short distances.

Sailors know latitudes from 40 to 70 degrees south as the "Roaring Forties

The Roaring Forties are strong westerly winds found in the Southern Hemisphere, generally between the latitudes of 40°S and 50°S. The strong west-to-east air currents are caused by the combination of air being displaced from the Equator ...

", "Furious Fifties" and "Shrieking Sixties" due to high winds and large waves that form as winds blow around the entire globe unimpeded by any land-mass. Icebergs, especially in May to October, make the area even more dangerous. The remoteness of the region makes sources of search and rescue scarce.

Physical oceanography

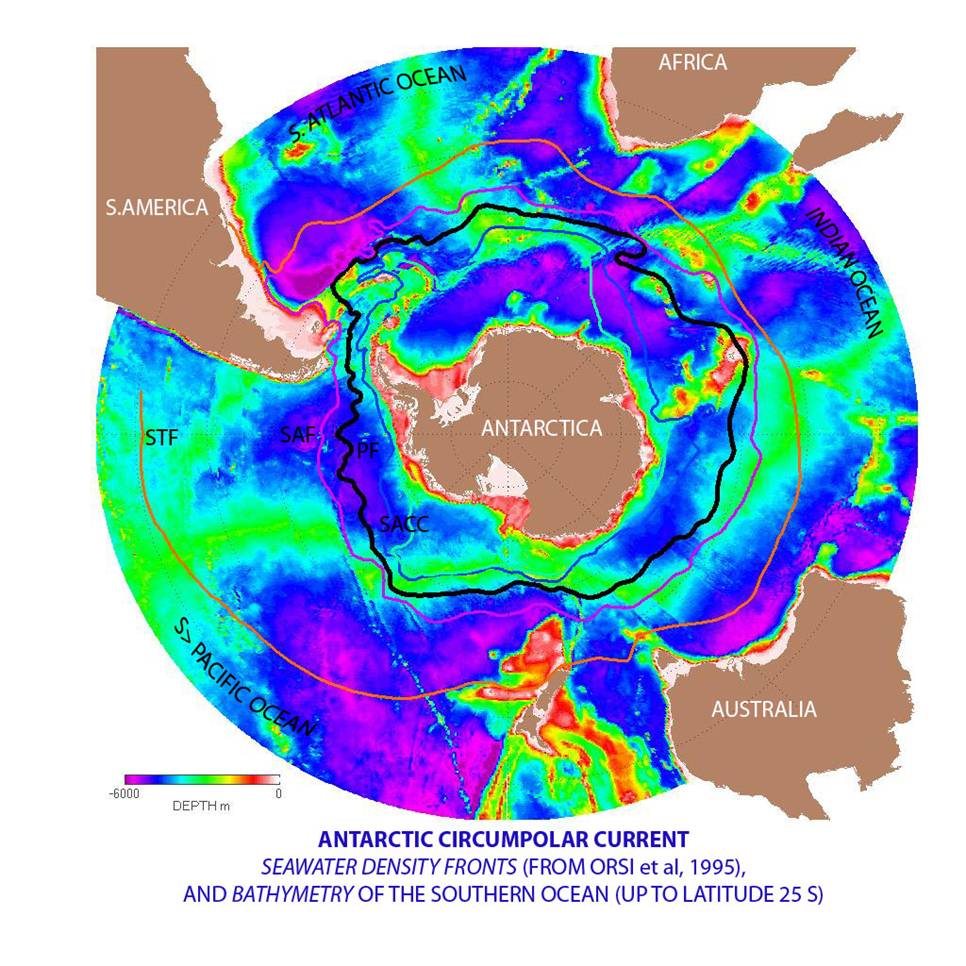

Antarctic Circumpolar Current and Antarctic Convergence

While the Southern is the second smallest ocean it contains the unique and highly energetic Antarctic Circumpolar Current which moves perpetually eastward – chasing and joining itself, and at in length – it comprises the world's longest ocean current, transporting of water – 100 times the flow of all the world's rivers.

Several processes operate along the coast of Antarctica to produce, in the Southern Ocean, types of water mass

An oceanographic water mass is an identifiable body of water with a common formation history which has physical properties distinct from surrounding water. Properties include temperature, salinity, chemical - isotopic ratios, and other physical ...

es not produced elsewhere in the oceans of the Southern Hemisphere. One of these is the Antarctic Bottom Water, a very cold, highly saline, dense water that forms under sea ice. Another is Circumpolar Deep Water

Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW) is a designation given to the water mass in the Pacific and Indian oceans that is a mixing of other water masses in the region. It is characteristically warmer and saltier than the surrounding water masses, causing CD ...

, a mixture of Antarctic Bottom Water and North Atlantic Deep Water

North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) is a deep water mass formed in the North Atlantic Ocean. Thermohaline circulation (properly described as meridional overturning circulation) of the world's oceans involves the flow of warm surface waters from the ...

.

Associated with the Circumpolar Current is the Antarctic Convergence

The Antarctic Convergence or Antarctic Polar Front is a marine belt encircling Antarctica, varying in latitude seasonally, where cold, northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the sub-Antarctic. Antarctic waters pr ...

encircling Antarctica, where cold northward-flowing Antarctic waters meet the relatively warmer waters of the subantarctic

The sub-Antarctic zone is a region in the Southern Hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This translates roughly to a latitude of between 46° and 60° south of the Equator. The subantarctic region includes many islands ...

, Antarctic waters predominantly sink beneath subantarctic waters, while associated zones of mixing and upwelling

Upwelling is an oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted surface water. The nut ...

create a zone very high in nutrients. These nurture high levels of phytoplankton with associated copepods and Antarctic krill, and resultant foodchains supporting fish, whales, seals, penguins, albatrosses and a wealth of other species.

The Antarctic Convergence is considered to be the best natural definition of the northern extent of the Southern Ocean.

Upwelling

Large-scale upwelling

Upwelling is an oceanographic phenomenon that involves wind-driven motion of dense, cooler, and usually nutrient-rich water from deep water towards the ocean surface. It replaces the warmer and usually nutrient-depleted surface water. The nut ...

is found in the Southern Ocean. Strong westerly (eastward) winds blow around Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest cont ...

, driving a significant flow of water northwards. This is actually a type of coastal upwelling. Since there are no continents in a band of open latitudes between South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

and the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, some of this water is drawn up from great depths. In many numerical models and observational syntheses, the Southern Ocean upwelling represents the primary means by which deep dense water is brought to the surface. Shallower, wind-driven upwelling is also found off the west coasts of North and South America, northwest and southwest Africa, and southwest and southeast Australia, all associated with oceanic subtropical high pressure circulations.

Some models of the ocean circulation suggest that broad-scale upwelling occurs in the tropics, as pressure driven flows converge water toward the low latitudes where it is diffusively warmed from above. The required diffusion coefficients, however, appear to be larger than are observed in the real ocean. Nonetheless, some diffusive upwelling does probably occur.

Ross and Weddell Gyres

The Ross Gyre

The Ross Gyre is one of the two gyres that exist within the Southern Ocean. The gyre is located in the Ross Sea, and rotates clockwise. The gyre is formed by interactions between the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and the Antarctic Continental She ...

and Weddell Gyre are two gyres that exist within the Southern Ocean. The gyres are located in the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

and Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

respectively, and both rotate clockwise. The gyres are formed by interactions between the Antarctic Circumpolar Current and the Antarctic Continental Shelf.

Sea ice has been noted to persist in the central area of the Ross Gyre. There is some evidence that global warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

has resulted in some decrease of the salinity of the waters of the Ross Gyre since the 1950s.

Due to the Coriolis effect

In physics, the Coriolis force is an inertial or fictitious force that acts on objects in motion within a frame of reference that rotates with respect to an inertial frame. In a reference frame with clockwise rotation, the force acts to the ...

acting to the left in the Southern Hemisphere and the resulting Ekman transport away from the centres of the Weddell Gyre, these regions are very productive due to upwelling of cold, nutrient rich water.

Observations

Observation of the Southern Ocean is coordinated through the Southern Ocean Observing System (SOOS)

SOOS is an international initiative of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) and the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR). It was officially launched in 2011. Its International Project Office is hosted by the Institut ...

. This provides access to meta data for a significant proportion of the data collected in the regions over the past decades including hydrographic measurements and ocean currents. The data provision is set up to emphasize records that are related to Essential Ocean Variables (EOVs) for the ocean region south of 40°S.

Climate

Sea temperatures vary from about −2 to 10 °C (28 to 50 °F). Cyclonic storms travel eastward around the continent and frequently become intense because of the temperature contrast between ice and open ocean

The pelagic zone consists of the water column of the open ocean, and can be further divided into regions by depth (as illustrated on the right). The word ''pelagic'' is derived . The pelagic zone can be thought of as an imaginary cylinder or wa ...

. The ocean-area from about latitude 40 south to the Antarctic Circle has the strongest average winds found anywhere on Earth. In winter the ocean freezes outward to 65 degrees south latitude in the Pacific sector and 55 degrees south latitude in the Atlantic sector, lowering surface temperatures well below 0 degrees Celsius. At some coastal points, however, persistent intense drainage winds from the interior keep the shoreline ice-free throughout the winter.

Climate change

The Southern Ocean is one of the regions in which rapid climate change is the most visibly taking place.El Niño–Southern Oscillation

El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is an irregular periodic variation in winds and sea surface temperatures over the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean, affecting the climate of much of the tropics and subtropics. The warming phase of the sea te ...

(ENSO).

Biodiversity

Animals

A variety of marine animals exist and rely, directly or indirectly, on the phytoplankton in the Southern Ocean. Antarctic sea life includes penguins, blue whales, orcas, colossal squids and fur seal

Fur seals are any of nine species of pinnipeds belonging to the subfamily Arctocephalinae in the family '' Otariidae''. They are much more closely related to sea lions than true seals, and share with them external ears (pinnae), relatively l ...

s. The emperor penguin is the only penguin that breeds during the winter in Antarctica, while the Adélie penguin breeds farther south than any other penguin. The rockhopper penguin has distinctive feathers around the eyes, giving the appearance of elaborate eyelashes. King penguins, chinstrap penguins, and gentoo penguins also breed in the Antarctic.

The Antarctic fur seal

The Antarctic fur seal (''Arctocephalus gazella''), is one of eight seals in the genus ''Arctocephalus'', and one of nine fur seals in the subfamily Arctocephalinae. Despite what its name suggests, the Antarctic fur seal is mostly distributed i ...

was very heavily hunted in the 18th and 19th centuries for its pelt by sealers from the United States and the United Kingdom. The Weddell seal

The Weddell seal (''Leptonychotes weddellii'') is a relatively large and abundant true seal with a circumpolar distribution surrounding Antarctica. The Weddell seal was discovered and named in the 1820s during expeditions led by British seali ...

, a " true seal", is named after Sir James Weddell, commander of British sealing expeditions in the Weddell Sea

The Weddell Sea is part of the Southern Ocean and contains the Weddell Gyre. Its land boundaries are defined by the bay formed from the coasts of Coats Land and the Antarctic Peninsula. The easternmost point is Cape Norvegia at Princess Martha ...

. Antarctic krill, which congregates in large schools

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsor ...

, is the keystone species of the ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

of the Southern Ocean, and is an important food organism for whales, seals, leopard seal

The leopard seal (''Hydrurga leptonyx''), also referred to as the sea leopard, is the second largest species of seal in the Antarctic (after the southern elephant seal). Its only natural predator is the orca. It feeds on a wide range of prey incl ...

s, fur seals, squid, icefish, penguins, albatrosses and many other birds.

The benthic communities of the seafloor are diverse and dense, with up to 155,000 animals found in . As the seafloor environment is very similar all around the Antarctic, hundreds of species can be found all the way around the mainland, which is a uniquely wide distribution for such a large community. Deep-sea gigantism is common among these animals.Census of Marine Life

The Census of Marine Life was a 10-year, US $650 million scientific initiative, involving a global network of researchers in more than 80 nations, engaged to assess and explain the diversity, distribution, and abundance of life in the oceans. Th ...

(CoML) and has disclosed some remarkable findings. More than 235 marine organisms live in both polar regions, having bridged the gap of . Large animals such as some cetaceans and birds make the round trip annually. More surprising are small forms of life such as mudworms, sea cucumbers and free-swimming snails found in both polar oceans. Various factors may aid in their distribution – fairly uniform temperatures of the deep ocean at the poles and the equator which differ by no more than , and the major current systems or marine conveyor belt which transport egg and larva stages. However, among smaller marine animals generally assumed to be the same in the Antarctica and the Arctic, more detailed studies of each population have often—but not always—revealed differences, showing that they are closely related cryptic species rather than a single bipolar species.

Birds

The rocky shores of mainland Antarctica and its offshore islands provide nesting space for over 100 million birds every spring. These nesters include species of albatrosses, petrel

Petrels are tube-nosed seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes.

Description

The common name does not indicate relationship beyond that point, as "petrels" occur in three of the four families within that group (all except the albatross f ...

s, skuas, gulls and tern

Terns are seabirds in the family Laridae that have a worldwide distribution and are normally found near the sea, rivers, or wetlands. Terns are treated as a subgroup of the family Laridae which includes gulls and skimmers and consists of e ...

s.endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found else ...

to South Georgia and some smaller surrounding islands. Freshwater ducks inhabit South Georgia and the Kerguelen Islands.Emperor penguins

The emperor penguin (''Aptenodytes forsteri'') is the tallest and heaviest of all living penguin species and is endemic to Antarctica. The male and female are similar in plumage and size, reaching in length and weighing from . Feathers of th ...

have four overlapping layers of feathers, keeping them warm. They are the only Antarctic animal to breed during the winter.

Fish

There are relatively few fish species in few families in the Southern Ocean. The most species-rich family are the snailfish (Liparidae), followed by the cod icefish (Nototheniidae)undescribed species

In taxonomy, an undescribed taxon is a taxon (for example, a species) that has been discovered, but not yet formally described and named. The various Nomenclature Codes specify the requirements for a new taxon to be validly described and named. U ...

also occur in the region, especially among the snailfish).

Icefish

Cod icefish (Nototheniidae), as well as several other families, are part of the

Cod icefish (Nototheniidae), as well as several other families, are part of the Notothenioidei

Notothenioidei is one of 19 suborders of the order Perciformes. The group is found mainly in Antarctic and Subantarctic waters, with some species ranging north to southern Australia and southern South America. Notothenioids constitute approx ...

suborder, collectively sometimes referred to as icefish. The suborder contains many species with antifreeze protein

Antifreeze proteins (AFPs) or ice structuring proteins refer to a class of polypeptides produced by certain animals, plants, fungi and bacteria that permit their survival in temperatures below the freezing point of water. AFPs bind to small ...

s in their blood and tissue, allowing them to live in water that is around or slightly below .crocodile icefish

The crocodile icefish or white-blooded fish comprise a family (Channichthyidae) of notothenioid fish found in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. They are the only known vertebrates to lack hemoglobin in their blood as adults. Icefish populatio ...

(family Channichthyidae), also known as white-blooded fish, are only found in the Southern Ocean. They lack hemoglobin in their blood, resulting in their blood being colourless. One Channichthyidae species, the mackerel icefish (''Champsocephalus gunnari''), was once the most common fish in coastal waters less than deep, but was overfished in the 1970s and 1980s. Schools of icefish spend the day at the seafloor and the night higher in the water column eating plankton and smaller fish.Dissostichus

''Dissostichus'', the toothfish, is a genus of marine ray-finned fish belonging to the family Nototheniidae, the notothens or cod icefish. These fish are found in the Southern Hemisphere. Toothfish are marketed in the United States as Chilean ...

'', the Antarctic toothfish (''Dissostichus mawsoni'') and the Patagonian toothfish

The Patagonian toothfish (''Dissostichus eleginoides'') is a species of notothen found in cold waters () between depths of in the southern Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans and Southern Ocean on seamounts and continental shelves around most ...

(''Dissostichus eleginoides''). These two species live on the seafloor deep, and can grow to around long weighing up to , living up to 45 years. The Antarctic toothfish lives close to the Antarctic mainland, whereas the Patagonian toothfish lives in the relatively warmer subantarctic waters. Toothfish are commercially fished, and overfishing has reduced toothfish populations.Notothenia

''Notothenia'' is a genus of marine ray-finned fishes belonging to the family Nototheniidae, the notothens or cod icefishes with the species in this genus often having the common name of rockcod. They are native to the Southern Ocean and other wa ...

'', which like the Antarctic toothfish have antifreeze in their bodies.

Mammals

Seven pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely range (biology), distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammal, marine mammals. They comprise the extant taxon, extant family (biology ...

species inhabit Antarctica. The largest, the elephant seal

Elephant seals are very large, oceangoing earless seals in the genus ''Mirounga''. Both species, the northern elephant seal (''M. angustirostris'') and the southern elephant seal (''M. leonina''), were hunted to the brink of extinction for oi ...

(''Mirounga leonina''), can reach up to , while females of the smallest, the Antarctic fur seal

The Antarctic fur seal (''Arctocephalus gazella''), is one of eight seals in the genus ''Arctocephalus'', and one of nine fur seals in the subfamily Arctocephalinae. Despite what its name suggests, the Antarctic fur seal is mostly distributed i ...

(''Arctophoca gazella''), reach only . These two species live north of the sea ice, and breed in harems on beaches. The other four species can live on the sea ice. Crabeater seal

The crabeater seal (''Lobodon carcinophaga''), also known as the krill-eater seal, is a true seal with a circumpolar distribution around the coast of Antarctica. They are medium- to large-sized (over 2 m in length), relatively slender and pale-c ...

s (''Lobodon carcinophagus'') and Weddell seal

The Weddell seal (''Leptonychotes weddellii'') is a relatively large and abundant true seal with a circumpolar distribution surrounding Antarctica. The Weddell seal was discovered and named in the 1820s during expeditions led by British seali ...

s (''Leptonychotes weddellii'') form breeding colonies, whereas leopard seal

The leopard seal (''Hydrurga leptonyx''), also referred to as the sea leopard, is the second largest species of seal in the Antarctic (after the southern elephant seal). Its only natural predator is the orca. It feeds on a wide range of prey incl ...

s (''Hydrurga leptonyx'') and Ross seal