Southern Cross Expedition on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Southern Cross'' Expedition, otherwise known as the British Antarctic Expedition, 1898–1900, was the first British venture of the

The ''Southern Cross'' Expedition, otherwise known as the British Antarctic Expedition, 1898–1900, was the first British venture of the

Born in Oslo in 1864 to a Norwegian father and an English mother, Carsten Borchgrevink emigrated to Australia in 1888, where he worked as a land surveyor in the interior before accepting a provincial schoolteaching appointment in

Born in Oslo in 1864 to a Norwegian father and an English mother, Carsten Borchgrevink emigrated to Australia in 1888, where he worked as a land surveyor in the interior before accepting a provincial schoolteaching appointment in

For his expedition's ship, Borchgrevink purchased in 1897 a steam whaler, ''Pollux'', that had been built in 1886 in

For his expedition's ship, Borchgrevink purchased in 1897 a steam whaler, ''Pollux'', that had been built in 1886 in

The ten-man shore party who were to winter at Cape Adare consisted of Borchgrevink, five scientists, a medical officer, a cook who also served as a general assistant, and two dog drivers. Five—including Borchgrevink—were Norwegian, two were English, one Australian and the two dog experts from northern Norway, sometimes described in expedition accounts as Lapps or "Finns".

Among the scientists was the Tasmanian

The ten-man shore party who were to winter at Cape Adare consisted of Borchgrevink, five scientists, a medical officer, a cook who also served as a general assistant, and two dog drivers. Five—including Borchgrevink—were Norwegian, two were English, one Australian and the two dog experts from northern Norway, sometimes described in expedition accounts as Lapps or "Finns".

Among the scientists was the Tasmanian  His later chronicle of the expedition was critical of aspects of Borchgrevink's leadership, but defended the expedition's scientific achievements. In 1901, Bernacchi would return to Antarctica as a physicist on Scott's ''Discovery'' expedition. Another of Borchgrevink's men who later served Scott's expedition, as commander of the relief ship , was William Colbeck, who held a lieutenant's commission in the

His later chronicle of the expedition was critical of aspects of Borchgrevink's leadership, but defended the expedition's scientific achievements. In 1901, Bernacchi would return to Antarctica as a physicist on Scott's ''Discovery'' expedition. Another of Borchgrevink's men who later served Scott's expedition, as commander of the relief ship , was William Colbeck, who held a lieutenant's commission in the

''Southern Cross'' left London on 23 August 1898, after inspection by

''Southern Cross'' left London on 23 August 1898, after inspection by  Unloading began on 17 February. First ashore were the dogs, with their two Sami handlers, Savio and Must, who remained with them and thus became the first men to spend a night on the Antarctic continent. (Arrival at Cape Adare) During the next twelve days the rest of the equipment and supplies were landed, and two prefabricated huts were erected, one as living quarters and the other for storage. (First Buildings) These were the first buildings erected on the continent. A third structure was contrived from spare materials, to serve as a magnetic observation hut. As accommodation for ten men the "living hut" was small and cramped, and seemingly precarious—Bernacchi later described it as "fifteen feet square, lashed down by cables to the rocky shore".Crane, p. 153 The dogs were housed in kennels fashioned from packing cases. By 2 March the base, christened "Camp Ridley" after Borchgrevink's English mother's maiden name, was fully established, and the Duke of York's flag raised. That day, ''Southern Cross'' departed to winter in Australia.

The living hut contained a small ante-room used as a photographic

Unloading began on 17 February. First ashore were the dogs, with their two Sami handlers, Savio and Must, who remained with them and thus became the first men to spend a night on the Antarctic continent. (Arrival at Cape Adare) During the next twelve days the rest of the equipment and supplies were landed, and two prefabricated huts were erected, one as living quarters and the other for storage. (First Buildings) These were the first buildings erected on the continent. A third structure was contrived from spare materials, to serve as a magnetic observation hut. As accommodation for ten men the "living hut" was small and cramped, and seemingly precarious—Bernacchi later described it as "fifteen feet square, lashed down by cables to the rocky shore".Crane, p. 153 The dogs were housed in kennels fashioned from packing cases. By 2 March the base, christened "Camp Ridley" after Borchgrevink's English mother's maiden name, was fully established, and the Duke of York's flag raised. That day, ''Southern Cross'' departed to winter in Australia.

The living hut contained a small ante-room used as a photographic

Winter proved to be a difficult time; Bernacchi wrote of rising boredom and irritation: "Officers and men, ten of us in all, found tempers wearing thin". During this period of confinement, Borchgrevink's weaknesses as a commander were exposed; he was, according to Bernacchi, "in many respects ... not a good leader". The polar historian

Winter proved to be a difficult time; Bernacchi wrote of rising boredom and irritation: "Officers and men, ten of us in all, found tempers wearing thin". During this period of confinement, Borchgrevink's weaknesses as a commander were exposed; he was, according to Bernacchi, "in many respects ... not a good leader". The polar historian

On 28 January 1900 ''Southern Cross'' returned. Borchgrevink and his party quickly vacated the camp, and on 2 February he took the ship south into the Ross Sea. Evidence of a hasty and disorderly departure from Cape Adare was noted two years later by members of the Discovery Expedition, when

On 28 January 1900 ''Southern Cross'' returned. Borchgrevink and his party quickly vacated the camp, and on 2 February he took the ship south into the Ross Sea. Evidence of a hasty and disorderly departure from Cape Adare was noted two years later by members of the Discovery Expedition, when

Borchgrevink's account of the expedition, ''First on the Antarctic Continent'', was published the following year; the English edition, much of which may have been embroidered by Newnes's staff, was criticised for its "journalistic" style and for its bragging tone. The author, whom commentators recognised was "not known for either his modesty or his tact", embarked on a lecture tour of England and Scotland, but the reception was generally poor.

Despite the unexplained disappearance of many of Hanson's notes, Hugh Robert Mill described the expedition as "interesting as a dashing piece of scientific work". The meteorological and magnetic conditions of Victoria Land had been recorded for a full year; the location of the South Magnetic Pole had been calculated (though not visited); samples of the continent's natural fauna and flora, and of its geology, had been collected. Borchgrevink also claimed the discovery of new insect and shallow-water fauna species, proving "bi-polarity" (existence of species in proximity to the North and South poles).

The geographical establishments in Britain and abroad were slow to give formal recognition to the expedition. The Royal Geographical Society gave Borchgrevink a fellowship, and other medals and honours eventually followed from Norway, Denmark and the United States, but the expedition's achievements were not widely recognised. Markham persisted in describing Borchgrevink as cunning and unprincipled;Riffenburgh, p. 56 Amundsen's warm tribute was a lone approving voice. According to Scott's biographer David Crane, if Borchgrevink had been a British naval officer his expedition would have been treated differently, but "a Norwegian seaman/schoolmaster was never going to be taken seriously". A belated recognition came in 1930, long after Markham's death, when the Royal Geographical Society presented Borchgrevink with its Patron's Medal. It admitted that "justice had not been done at the time to the pioneer work of the ''Southern Cross'' expedition", and that the magnitude of the difficulties it had overcome had previously been underestimated. After the expedition, Borchgrevink lived quietly, largely out of the public eye. He died in Oslo on 21 April 1934.

Borchgrevink's account of the expedition, ''First on the Antarctic Continent'', was published the following year; the English edition, much of which may have been embroidered by Newnes's staff, was criticised for its "journalistic" style and for its bragging tone. The author, whom commentators recognised was "not known for either his modesty or his tact", embarked on a lecture tour of England and Scotland, but the reception was generally poor.

Despite the unexplained disappearance of many of Hanson's notes, Hugh Robert Mill described the expedition as "interesting as a dashing piece of scientific work". The meteorological and magnetic conditions of Victoria Land had been recorded for a full year; the location of the South Magnetic Pole had been calculated (though not visited); samples of the continent's natural fauna and flora, and of its geology, had been collected. Borchgrevink also claimed the discovery of new insect and shallow-water fauna species, proving "bi-polarity" (existence of species in proximity to the North and South poles).

The geographical establishments in Britain and abroad were slow to give formal recognition to the expedition. The Royal Geographical Society gave Borchgrevink a fellowship, and other medals and honours eventually followed from Norway, Denmark and the United States, but the expedition's achievements were not widely recognised. Markham persisted in describing Borchgrevink as cunning and unprincipled;Riffenburgh, p. 56 Amundsen's warm tribute was a lone approving voice. According to Scott's biographer David Crane, if Borchgrevink had been a British naval officer his expedition would have been treated differently, but "a Norwegian seaman/schoolmaster was never going to be taken seriously". A belated recognition came in 1930, long after Markham's death, when the Royal Geographical Society presented Borchgrevink with its Patron's Medal. It admitted that "justice had not been done at the time to the pioneer work of the ''Southern Cross'' expedition", and that the magnitude of the difficulties it had overcome had previously been underestimated. After the expedition, Borchgrevink lived quietly, largely out of the public eye. He died in Oslo on 21 April 1934.

The ''Southern Cross'' Expedition, otherwise known as the British Antarctic Expedition, 1898–1900, was the first British venture of the

The ''Southern Cross'' Expedition, otherwise known as the British Antarctic Expedition, 1898–1900, was the first British venture of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration was an era in the exploration of the continent of Antarctica which began at the end of the 19th century, and ended after the First World War; the Shackleton–Rowett Expedition of 1921–1922 is often ci ...

, and the forerunner of the more celebrated journeys of Robert Falcon Scott

Captain Robert Falcon Scott, , (6 June 1868 – c. 29 March 1912) was a British Royal Navy officer and explorer who led two expeditions to the Antarctic regions: the ''Discovery'' expedition of 1901–1904 and the ill-fated ''Terra Nov ...

and Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton (15 February 1874 – 5 January 1922) was an Anglo-Irish Antarctic explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. He was one of the principal figures of the period known as the Heroic Age o ...

. The brainchild of the Anglo-Norwegian explorer Carsten Borchgrevink

Carsten Egeberg Borchgrevink (1 December 186421 April 1934) was an Anglo-Norwegian polar explorer and a pioneer of Antarctic travel. He inspired Sir Robert Falcon Scott, Sir Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen, and others associated with the Hero ...

, it was the first expedition to over-winter on the Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and othe ...

mainland, the first to visit the Great Ice Barrier

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between hi ...

—later known as the Ross Ice Shelf—since Sir James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

's groundbreaking expedition of 1839 to 1843, and the first to effect a landing on the Barrier's surface. It also pioneered the use of dogs and sledges in Antarctic travel.

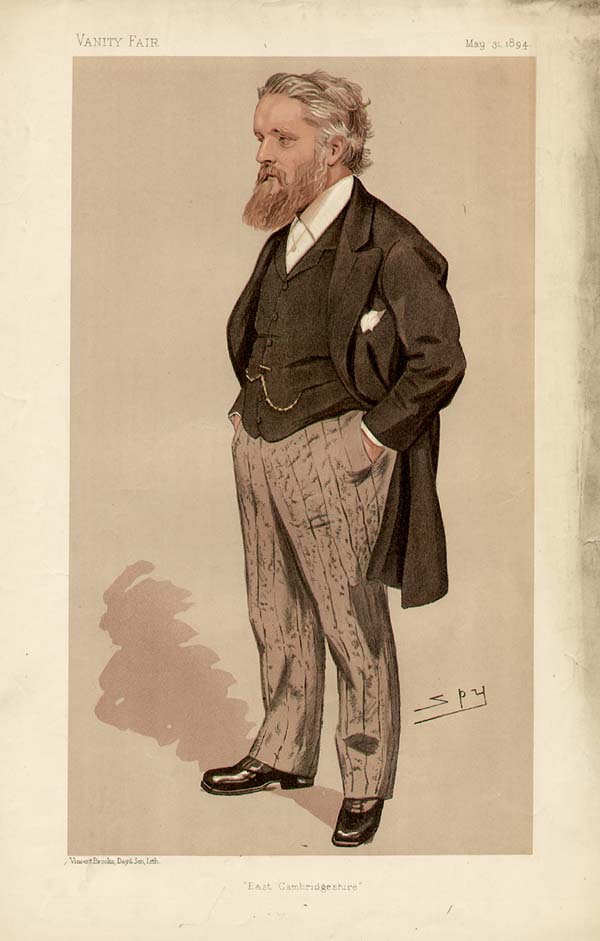

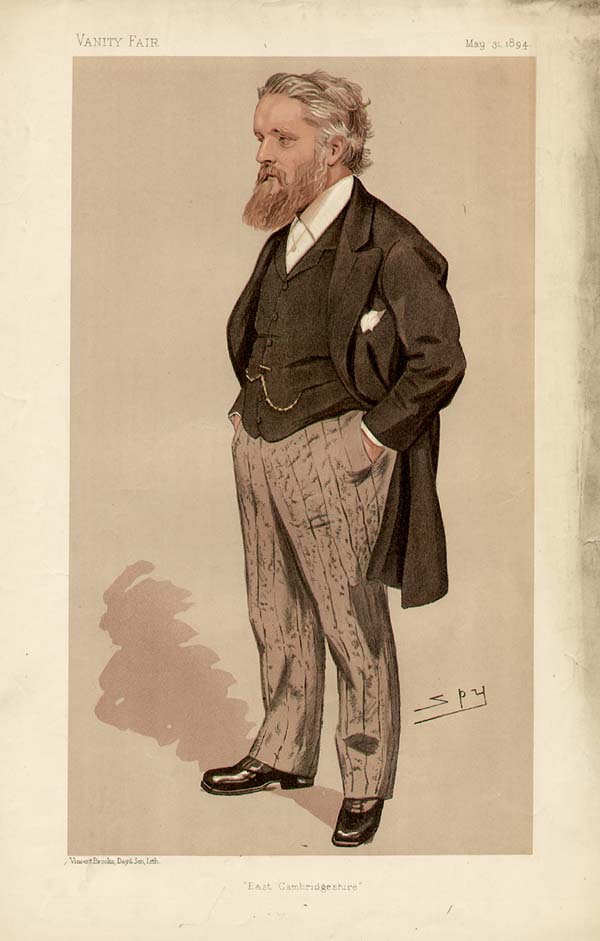

The expedition was privately financed by the British magazine publisher Sir George Newnes

Sir George Newnes, 1st Baronet (13 March 1851 – 9 June 1910) was a British publisher and editor and a founding figure in popular journalism. Newnes also served as a Liberal Party Member of Parliament for two decades. His company, George Newne ...

. Borchgrevink's party sailed in the , and spent the southern winter of 1899 at Cape Adare

Cape Adare is a prominent cape of black basalt forming the northern tip of the Adare Peninsula and the north-easternmost extremity of Victoria Land, East Antarctica.

Description

Marking the north end of Borchgrevink Coast and the west ...

, the northwest extremity of the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

coastline. Here they carried out an extensive programme of scientific observations, although opportunities for inland exploration were restricted by the mountainous and glaciated terrain surrounding the base. In January 1900, the party left Cape Adare in ''Southern Cross'' to explore the Ross Sea, following the route taken by Ross 60 years earlier. They reached the Great Ice Barrier, where a team of three made the first sledge journey on the Barrier surface, during which a new Farthest South

Farthest South refers to the most southerly latitude reached by explorers before the first successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911. Significant steps on the road to the pole were the discovery of lands south of Cape Horn in 1619, Captai ...

record latitude was established at 78° 50′S.

On its return to Britain the expedition was coolly received by London's geographical establishment exemplified by the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

, which resented the pre-emption of the pioneering Antarctic role they envisaged for the ''Discovery'' Expedition. There were also questions about Borchgrevink's leadership qualities, and criticism of the limited extent of scientific results. Thus, despite the number of significant "firsts", Borchgrevink was never accorded the heroic status of Scott or Shackleton, and his expedition was soon forgotten in the dramas which surrounded these and other Heroic Age explorers. However, Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen (, ; ; 16 July 1872 – ) was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He was a key figure of the period known as the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen beg ...

, conqueror of the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

in 1911, acknowledged that Borchgrevink's expedition had removed the greatest obstacles to Antarctic travel, and had opened the way for all the expeditions that followed.

Background

Born in Oslo in 1864 to a Norwegian father and an English mother, Carsten Borchgrevink emigrated to Australia in 1888, where he worked as a land surveyor in the interior before accepting a provincial schoolteaching appointment in

Born in Oslo in 1864 to a Norwegian father and an English mother, Carsten Borchgrevink emigrated to Australia in 1888, where he worked as a land surveyor in the interior before accepting a provincial schoolteaching appointment in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. Having a taste for adventure, in 1894 he joined a commercial whaling expedition, led by Henryk Bull

Henrik Johan Bull (13 October 18441 June 1930) was a Norwegian businessman and whaler. Henry Bull was one of the pioneers in the exploration of Antarctica.

Biography

Henrik Johan Bull was born at Stokke in Vestfold County, Norway. He attended sc ...

, which penetrated Antarctic waters and reached Cape Adare

Cape Adare is a prominent cape of black basalt forming the northern tip of the Adare Peninsula and the north-easternmost extremity of Victoria Land, East Antarctica.

Description

Marking the north end of Borchgrevink Coast and the west ...

, the western portal to the Ross Sea

The Ross Sea is a deep bay of the Southern Ocean in Antarctica, between Victoria Land and Marie Byrd Land and within the Ross Embayment, and is the southernmost sea on Earth. It derives its name from the British explorer James Clark Ross who ...

. A party including Bull and Borchgrevink briefly landed there, and claimed to be the first men to set foot on the Antarctic continent—although the American sealer John Davis believed he had landed on the Antarctic Peninsula

The Antarctic Peninsula, known as O'Higgins Land in Chile and Tierra de San Martín in Argentina, and originally as Graham Land in the United Kingdom and the Palmer Peninsula in the United States, is the northernmost part of mainland Antarctic ...

in 1821. Bull's party also visited Possession Island in the Ross Sea, leaving a message in a tin box as proof of their journey. p. 3 Borchgrevink was convinced that the Cape Adare location, with its huge penguin rookery providing a ready supply of fresh food and blubber

Blubber is a thick layer of vascularized adipose tissue under the skin of all cetaceans, pinnipeds, penguins, and sirenians.

Description

Lipid-rich, collagen fiber-laced blubber comprises the hypodermis and covers the whole body, except fo ...

, could serve as a base at which a future expedition could overwinter

Overwintering is the process by which some organisms pass through or wait out the winter season, or pass through that period of the year when "winter" conditions (cold or sub-zero temperatures, ice, snow, limited food supplies) make normal activi ...

and subsequently explore the Antarctic interior. (Introduction)Preston, pp. 14–16

After his return from Cape Adare, Borchgrevink spent much of the following years in Britain and Australia, seeking financial backing for an Antarctic expedition. Despite a well-received address to the 1895 Sixth International Geographical Congress in London, in which he professed his willingness to lead such a venture, he was initially unsuccessful. p. 1 The Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

(RGS) was preparing its own plans for a large-scale National Antarctic Expedition (which eventually became the ''Discovery'' Expedition 1901–04) and was in search of funds; Borchgrevink was regarded by RGS president Sir Clements Markham as a foreign interloper and a rival for funding. Borchgrevink persuaded the publisher Sir George Newnes

Sir George Newnes, 1st Baronet (13 March 1851 – 9 June 1910) was a British publisher and editor and a founding figure in popular journalism. Newnes also served as a Liberal Party Member of Parliament for two decades. His company, George Newne ...

(whose business rival Alfred Harmsworth

Alfred Charles William Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Northcliffe (15 July 1865 – 14 August 1922), was a British newspaper and publishing magnate. As owner of the ''Daily Mail'' and the ''Daily Mirror'', he was an early developer of popular journal ...

was backing the RGS venture) to meet the full cost of his expedition, some £40,000. This gift infuriated Markham and the RGS, since Newnes's donation, had it come their way would, he said have been enough "to get the National Expedition on its legs". p. 2

Newnes stipulated that Borchgrevink's expedition should sail under the British flag

The national flag of the United Kingdom is the Union Jack, also known as the Union Flag.

The design of the Union Jack dates back to the Act of Union 1801 which united the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Ireland (previously in per ...

, and be styled the "British Antarctic Expedition". Borchgrevink readily agreed to these conditions, even though only two of the entire expedition party were British.Jones, pp. 59–60. Another member of the shore party, Louis Bernacchi

Louis Charles Bernacchi (8 November 1876 – 24 April 1942) was an Australian physicist and astronomer best known for his role in several Antarctic expeditions.

Early life

Bernacchi was born in Belgium on 8 November 1876 to Italian pare ...

, was Australian; the remainder were all Scandinavian. This annoyed Markham all the more,Crane, p. 74 and he subsequently rebuked the RGS librarian Hugh Robert Mill

Hugh Robert Mill (28 May 1861 – 5 April 1950) was a British geographer and meteorologist who was influential in the reform of geography teaching, and in the development of meteorology as a science. He was President of the Royal Meteorologic ...

for attending the Southern Cross Expedition launch. Mill had toasted the success of the expedition, calling it "a reproach to human enterprise" that there were parts of the earth that man had never attempted to reach. He hoped that this reproach would be lifted through "the munificence of Sir George Newnes and the courage of Mr Borchgrevink".

Organisation

Expedition objectives

Borchgrevink's original expedition objectives included the development of commercial opportunities, as well as scientific and geographical discovery. However, his plans to exploit the extensiveguano

Guano (Spanish from qu, wanu) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. As a manure, guano is a highly effective fertilizer due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. G ...

deposits that he had observed during his 1894–95 voyage were not pursued. Research would be carried out across a range of disciplines,Equipment and Personnel and Borchgrevink hoped that the scientific results would be complemented by spectacular geographical discoveries and journeys, even perhaps an attempt on the geographical South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

itself; he was unaware at this stage that the site of the base at Cape Adare would not allow access to the hinterland of Antarctica.

Ship

For his expedition's ship, Borchgrevink purchased in 1897 a steam whaler, ''Pollux'', that had been built in 1886 in

For his expedition's ship, Borchgrevink purchased in 1897 a steam whaler, ''Pollux'', that had been built in 1886 in Arendal

Arendal () is a municipality in Agder county in southeastern Norway. Arendal belongs to the region of Sørlandet. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Arendal (which is also the seat of Agder county). Some of the notab ...

on the south east coast of Norway, to the design of renowned shipbuilder Colin Archer Colin Archer (22 July 1832 – 8 February 1921) was a Norwegian naval architect and shipbuilder known for his seaworthy pilot and rescue boats and the larger sailing and polar ships. His most famous ship is the '' Fram'', used on both in Fridt ...

.Borchgrevink, pp. 10–11. Archer had designed and built Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (; 10 October 186113 May 1930) was a Norwegian polymath and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. He gained prominence at various points in his life as an explorer, scientist, diplomat, and humanitarian. He led the team t ...

's ship, , which in 1896 had returned unscathed from its long drift in the northern polar ocean during Nansen's ''Fram'' expedition. ''Pollux'', which Borchgrevink renamed , was barque-rigged, 520 gross register tons, and overall length.

The ship was taken to Archer's yard in Larvik

Larvik () is a town and municipality in Vestfold in Vestfold og Telemark county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Larvik. The municipality of Larvik has about 46,364 inhabitants. The municipality has a 110 ...

to be fitted out with engines designed to Borchgrevink's specification. Although Markham continued to question the ship's seaworthiness,Preston, p. 16. she was able to fulfil all that was required of her in Antarctic waters. Like several of the historic polar ships her post-expedition life was relatively short. She was sold to the Newfoundland Sealing Company, and in April 1914, was lost with her entire complement of 173, in the 1914 ''Newfoundland'' sealing disaster.

Personnel

The ten-man shore party who were to winter at Cape Adare consisted of Borchgrevink, five scientists, a medical officer, a cook who also served as a general assistant, and two dog drivers. Five—including Borchgrevink—were Norwegian, two were English, one Australian and the two dog experts from northern Norway, sometimes described in expedition accounts as Lapps or "Finns".

Among the scientists was the Tasmanian

The ten-man shore party who were to winter at Cape Adare consisted of Borchgrevink, five scientists, a medical officer, a cook who also served as a general assistant, and two dog drivers. Five—including Borchgrevink—were Norwegian, two were English, one Australian and the two dog experts from northern Norway, sometimes described in expedition accounts as Lapps or "Finns".

Among the scientists was the Tasmanian Louis Bernacchi

Louis Charles Bernacchi (8 November 1876 – 24 April 1942) was an Australian physicist and astronomer best known for his role in several Antarctic expeditions.

Early life

Bernacchi was born in Belgium on 8 November 1876 to Italian pare ...

, who had studied magnetism and meteorology at the Melbourne Observatory. He had been appointed to the Belgian Antarctic Expedition

The Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899 was the first expedition to winter in the Antarctic region. Led by Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery aboard the RV ''Belgica'', it was the first Belgian Antarctic expedition and is considered the firs ...

of 1897–1899, but had been unable to take up his post when the expedition's ship, the , had failed to call at Melbourne on its way south. Bernacchi then travelled to London and secured a place on Borchgrevink's scientific staff.

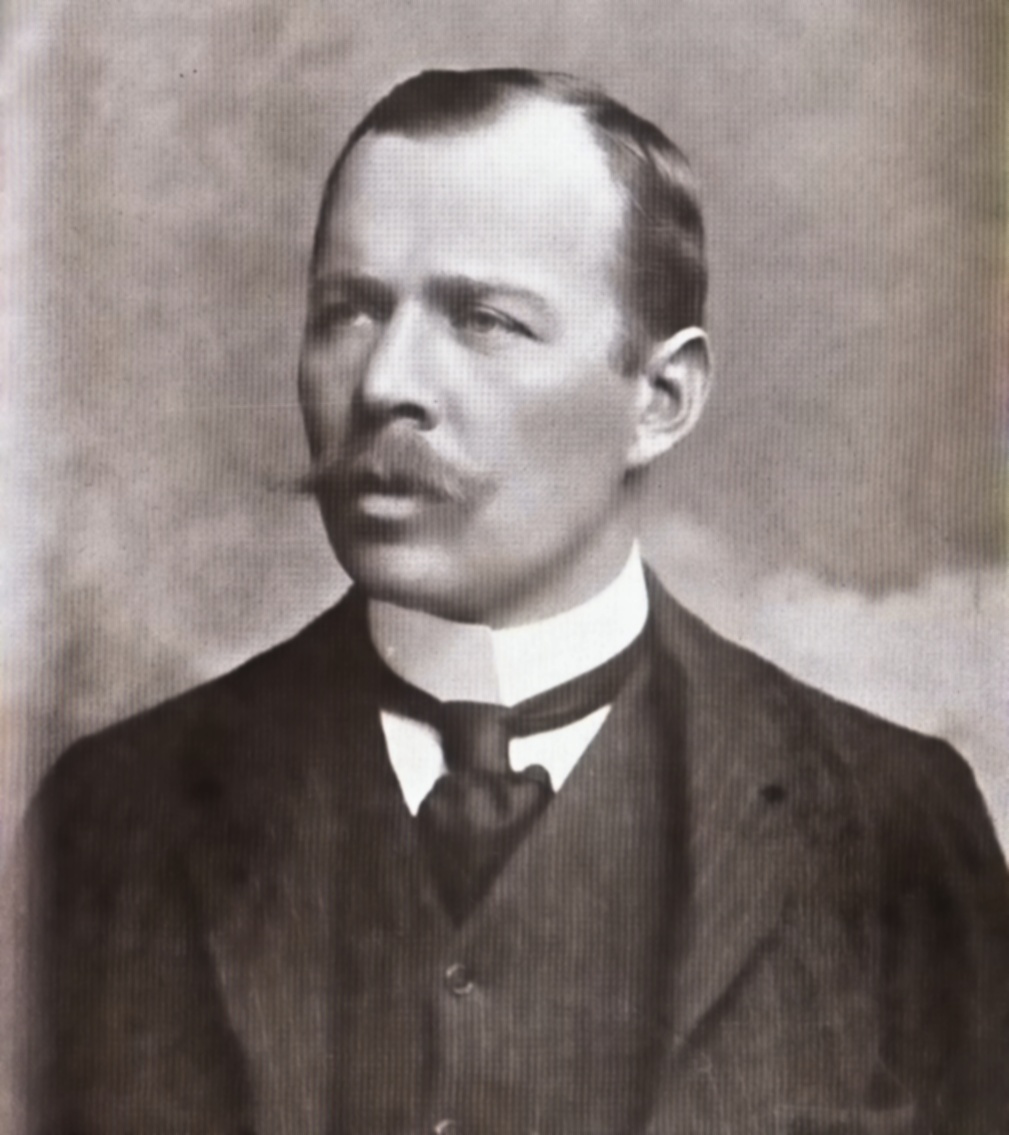

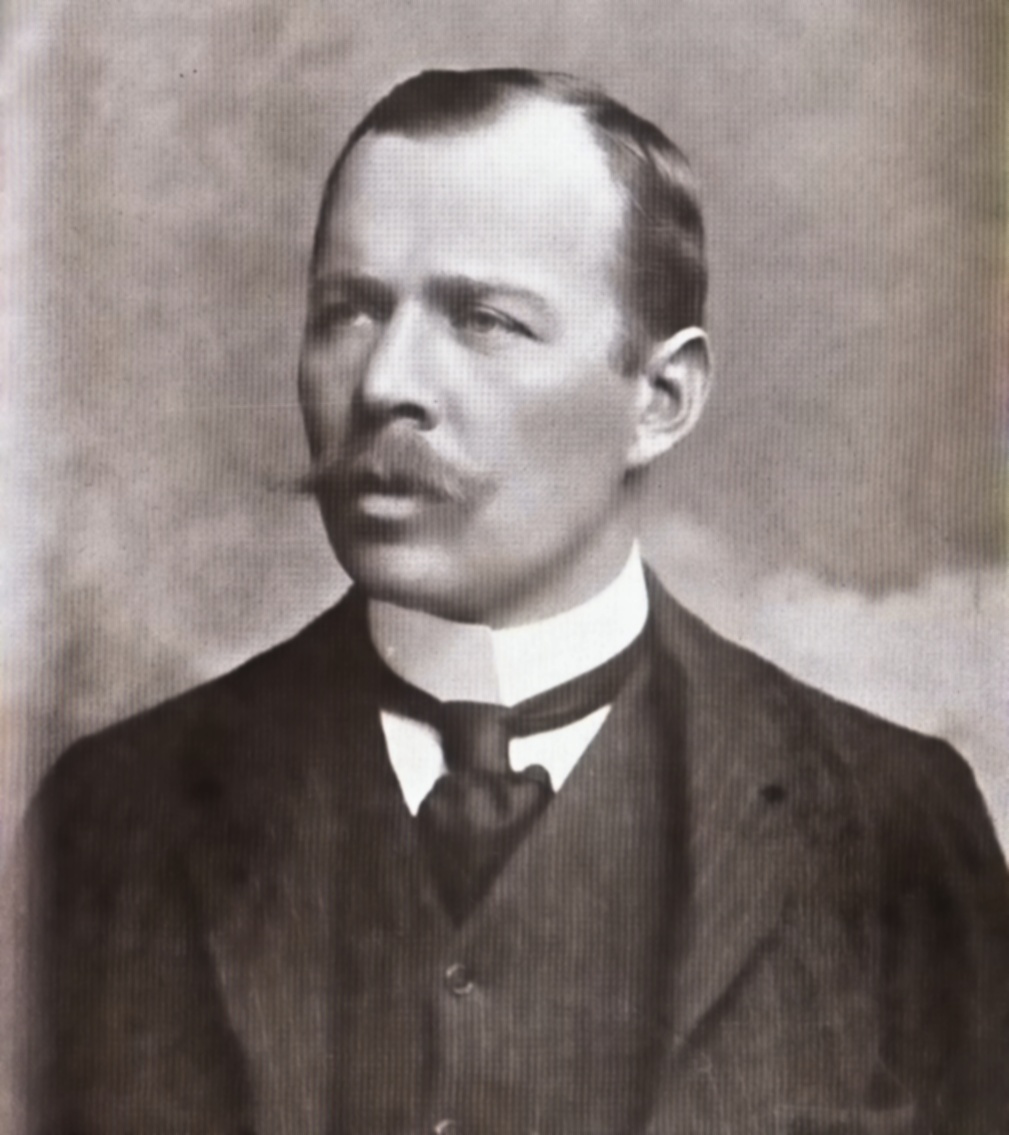

His later chronicle of the expedition was critical of aspects of Borchgrevink's leadership, but defended the expedition's scientific achievements. In 1901, Bernacchi would return to Antarctica as a physicist on Scott's ''Discovery'' expedition. Another of Borchgrevink's men who later served Scott's expedition, as commander of the relief ship , was William Colbeck, who held a lieutenant's commission in the

His later chronicle of the expedition was critical of aspects of Borchgrevink's leadership, but defended the expedition's scientific achievements. In 1901, Bernacchi would return to Antarctica as a physicist on Scott's ''Discovery'' expedition. Another of Borchgrevink's men who later served Scott's expedition, as commander of the relief ship , was William Colbeck, who held a lieutenant's commission in the Royal Naval Reserve

The Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) is one of the two volunteer reserve forces of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. Together with the Royal Marines Reserve, they form the Maritime Reserve. The present RNR was formed by merging the original R ...

. In preparation for the Southern Cross Expedition, Colbeck had taken a course in magnetism at Kew Observatory

The King's Observatory (called for many years the Kew Observatory) is a Grade I listed building in Richmond, London. Now a private dwelling, it formerly housed an astronomical and terrestrial magnetic observatory founded by King George III. T ...

.

Borchgrevink's assistant zoologist was Hugh Blackwell Evans, a vicar's son from Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

, who had spent three years on a cattle ranch in Canada and had also been on a sealing voyage to the Kerguelen Islands

The Kerguelen Islands ( or ; in French commonly ' but officially ', ), also known as the Desolation Islands (' in French), are a group of islands in the sub-Antarctic constituting one of the two exposed parts of the Kerguelen Plateau, a lar ...

. The chief zoologist was Nicolai Hanson, a graduate from the Royal Frederick University

The University of Oslo ( no, Universitetet i Oslo; la, Universitas Osloensis) is a public research university located in Oslo, Norway. It is the highest ranked and oldest university in Norway. It is consistently ranked among the top universit ...

. Also in the shore party was Herluf Kløvstad, the expedition's medical officer, whose previous appointment had been to a lunatic asylum in Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Vestland county on the Western Norway, west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the list of towns and cities in Norway, secon ...

. The others were Anton Fougner, scientific assistant and general handyman; Kolbein Ellifsen, cook and general assistant; and the two Sami dog-handlers, Per Savio and Ole Must, who, at 21 and 20 years of age respectively, were the youngest of the party.

The ship's company, under Captain Bernard Jensen, consisted of 19 Norwegian officers and seamen and one Swedish steward. Jensen was an experienced ice navigator in Arctic and Antarctic waters, and had been with Borchgrevink on Bull's ''Antarctic'' voyage in 1894–1895.Borchgrevink, pp. 13–19.

Voyage

Cape Adare

''Southern Cross'' left London on 23 August 1898, after inspection by

''Southern Cross'' left London on 23 August 1898, after inspection by the Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was Du ...

(the future King George V), who presented a Union Flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

. The ship was carrying 31 men and 90 Siberian sledge dogs, the first to be taken on an Antarctic expedition. (Equipment and Personnel) After final provisioning in Hobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/ Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

, Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, ''Southern Cross'' sailed for the Antarctic on 19 December. She crossed the Antarctic Circle

The Antarctic Circle is the most southerly of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of Earth. The region south of this circle is known as the Antarctic, and the zone immediately to the north is called the Southern Temperate Zone. So ...

on 23 January 1899, and after a three-week delay in pack ice

Drift ice, also called brash ice, is sea ice that is not attached to the shoreline or any other fixed object (shoals, grounded icebergs, etc.).Leppäranta, M. 2011. The Drift of Sea Ice. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Unlike fast ice, which is "faste ...

sighted Cape Adare on 16 February, before anchoring close to the shore on the following day.

Cape Adare, discovered by Antarctic explorer James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

during his 1839–43 expedition, lies at the end of a long promontory

A promontory is a raised mass of land that projects into a lowland or a body of water (in which case it is a peninsula). Most promontories either are formed from a hard ridge of rock that has resisted the erosive forces that have removed the ...

, below which is the large triangular shingle foreshore

The intertidal zone, also known as the foreshore, is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide (in other words, the area within the tidal range). This area can include several types of habitats with various specie ...

where Bull and Borchgrevink had made their brief landing in 1895. This foreshore held one of the largest Adelie penguin Adelie or Adélie may refer to:

* Adélie Land, a claimed territory on the continent of Antarctica

* Adelie Land meteorite, a meteorite discovered on December 5, 1912, in Antarctica by Francis Howard Bickerton

* Adélie penguin

The Adélie pen ...

rookeries on the entire continent and had ample room, as Borchgrevink had remarked in 1895, "for houses, tents and provisions". The abundance of penguins would provide both a winter larder and a fuel source.Preston, p. 14

Unloading began on 17 February. First ashore were the dogs, with their two Sami handlers, Savio and Must, who remained with them and thus became the first men to spend a night on the Antarctic continent. (Arrival at Cape Adare) During the next twelve days the rest of the equipment and supplies were landed, and two prefabricated huts were erected, one as living quarters and the other for storage. (First Buildings) These were the first buildings erected on the continent. A third structure was contrived from spare materials, to serve as a magnetic observation hut. As accommodation for ten men the "living hut" was small and cramped, and seemingly precarious—Bernacchi later described it as "fifteen feet square, lashed down by cables to the rocky shore".Crane, p. 153 The dogs were housed in kennels fashioned from packing cases. By 2 March the base, christened "Camp Ridley" after Borchgrevink's English mother's maiden name, was fully established, and the Duke of York's flag raised. That day, ''Southern Cross'' departed to winter in Australia.

The living hut contained a small ante-room used as a photographic

Unloading began on 17 February. First ashore were the dogs, with their two Sami handlers, Savio and Must, who remained with them and thus became the first men to spend a night on the Antarctic continent. (Arrival at Cape Adare) During the next twelve days the rest of the equipment and supplies were landed, and two prefabricated huts were erected, one as living quarters and the other for storage. (First Buildings) These were the first buildings erected on the continent. A third structure was contrived from spare materials, to serve as a magnetic observation hut. As accommodation for ten men the "living hut" was small and cramped, and seemingly precarious—Bernacchi later described it as "fifteen feet square, lashed down by cables to the rocky shore".Crane, p. 153 The dogs were housed in kennels fashioned from packing cases. By 2 March the base, christened "Camp Ridley" after Borchgrevink's English mother's maiden name, was fully established, and the Duke of York's flag raised. That day, ''Southern Cross'' departed to winter in Australia.

The living hut contained a small ante-room used as a photographic darkroom

A darkroom is used to process photographic film, to make prints and to carry out other associated tasks. It is a room that can be made completely dark to allow the processing of the light-sensitive photographic materials, including film and ph ...

, and another for taxidermy

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body via mounting (over an armature) or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word ''taxidermy'' describes the proc ...

. Daylight was admitted to the hut via a double-glazed, shuttered window, and through a small square pane high on the northern wall. Bunks were fitted around the outer walls, and a table and stove dominated the centre. During the few remaining weeks of Antarctic summer, members of the party practised travel with dogs and sledges on the sea ice in nearby Robertson Bay

Robertson Bay is a large, roughly triangular bay that indents the north coast of Victoria Land between Cape Barrow and Cape Adare. Discovered in 1841 by Captain James Clark Ross, Royal Navy, who named it for Dr. John Robertson, Surgeon on HMS ' ...

, surveyed the coastline, collected specimens of birds and fish, and slaughtered seals and penguins for food and fuel. Outside activities were largely curtailed in mid-May, with the onset of winter.

Antarctic winter

Winter proved to be a difficult time; Bernacchi wrote of rising boredom and irritation: "Officers and men, ten of us in all, found tempers wearing thin". During this period of confinement, Borchgrevink's weaknesses as a commander were exposed; he was, according to Bernacchi, "in many respects ... not a good leader". The polar historian

Winter proved to be a difficult time; Bernacchi wrote of rising boredom and irritation: "Officers and men, ten of us in all, found tempers wearing thin". During this period of confinement, Borchgrevink's weaknesses as a commander were exposed; he was, according to Bernacchi, "in many respects ... not a good leader". The polar historian Ranulph Fiennes

Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, 3rd Baronet (born 7 March 1944), commonly known as Sir Ranulph Fiennes () and sometimes as Ran Fiennes, is a British explorer, writer and poet, who holds several endurance records.

Fiennes served in the ...

later described the conditions as "democratic anarchy", with dirt, disorder and inactivity the order of the day.

Borchgrevink's lack of scientific training, and his inability to make simple observations, were additional matters of concern. (Departure of the Expedition) Nevertheless, the programme of scientific observations was maintained throughout the winter. Exercise was taken outside the hut when the weather permitted, and as a further diversion Savio improvised a sauna

A sauna (, ), or sudatory, is a small room or building designed as a place to experience dry or wet heat sessions, or an establishment with one or more of these facilities. The steam and high heat make the bathers perspire. A thermometer in a ...

in the snowdrifts. Concerts were held, including lantern slides, songs and readings. (Life at Camp Ridley) During this time there were two near-fatal incidents; in the first, a candle left burning beside a bunk set fire to the hut and caused extensive damage. In the second, three of the party were nearly asphyxiated by coal fire fumes as they slept.

The party was well-supplied with a variety of basic foodstuffs—butter, tea and coffee, herrings, sardines, cheeses, soup, tinned tripe, plum pudding, dry potatoes and vegetables. There were nevertheless complaints about the lack of luxuries, Colbeck noting that "all the tinned fruits supplied for the land party were either eaten on the passage or left on board for the hip'screw". There was also a shortage of tobacco; in spite of an intended provision of half a ton (500 kg), only a quantity of chewing tobacco was landed.

The zoologist, Nicolai Hanson, had fallen ill during the winter. On 14 October 1899 he died, apparently of an intestinal disorder, and became the first person to be buried on the Antarctic continent. The grave was dynamited from the frozen ground at the summit of the Cape. (First Burial) Bernacchi wrote: "There amidst profound silence and peace, there is nothing to disturb that eternal sleep except the flight of seabirds". Hanson left a wife, and a baby daughter born after he left for the Antarctic.

As winter gave way to spring, the party prepared for more ambitious inland journeys using the dogs and sledges. Their base camp was cut off from the continent's interior by high mountain ranges, and journeys along the coastline were frustrated by unsafe sea ice. These factors severely restricted their exploration, which was largely confined to the vicinity of Robertson Bay. Here, a small island was discovered, which was named Duke of York Island, after the expedition's patron.Borchgrevink, p. 22 A few years later this find was dismissed by members of Scott's Discovery Expedition, who claimed that the island "did not exist", but its position has since been confirmed at 71°38′S, 170°04′E.

Ross Sea exploration

On 28 January 1900 ''Southern Cross'' returned. Borchgrevink and his party quickly vacated the camp, and on 2 February he took the ship south into the Ross Sea. Evidence of a hasty and disorderly departure from Cape Adare was noted two years later by members of the Discovery Expedition, when

On 28 January 1900 ''Southern Cross'' returned. Borchgrevink and his party quickly vacated the camp, and on 2 February he took the ship south into the Ross Sea. Evidence of a hasty and disorderly departure from Cape Adare was noted two years later by members of the Discovery Expedition, when Edward Wilson Edward Wilson may refer to:

*Ed Wilson (artist) (1925–1996), African American sculptor

* Ed Wilson (baseball) (1875–?), American baseball player

* Ed Wilson (singer) (1945–2010), Brazilian singer-songwriter

* Ed Wilson, American television ex ...

wrote; "... heaps of refuse all around, and a mountain of provision boxes, dead birds, seals, dogs, sledging gear ... and heaven knows what else".

''Southern Cross'' first called at Possession Island, where the tin box left by Borchgrevink and Bull in 1895 was recovered. They then proceeded southwards, following the Victoria Land

Victoria Land is a region in eastern Antarctica which fronts the western side of the Ross Sea and the Ross Ice Shelf, extending southward from about 70°30'S to 78°00'S, and westward from the Ross Sea to the edge of the Antarctic Plateau. I ...

coast and discovering further islands, one of which Borchgrevink named after Sir Clements Markham, whose hostility towards the expedition was evidently unchanged by this honour.Huxley, p. 25 ''Southern Cross'' then sailed on to Ross Island

Ross Island is an island formed by four volcanoes in the Ross Sea near the continent of Antarctica, off the coast of Victoria Land in McMurdo Sound. Ross Island lies within the boundaries of Ross Dependency, an area of Antarctica claimed by N ...

, observed the volcano Mount Erebus

Mount Erebus () is the second-highest volcano in Antarctica (after Mount Sidley), the highest active volcano in Antarctica, and the southernmost active volcano on Earth. It is the sixth-highest ultra mountain on the continent.

With a sum ...

, and attempted a landing at Cape Crozier

Cape Crozier is the most easterly point of Ross Island in Antarctica. It was discovered in 1841 during James Clark Ross's expedition of 1839 to 1843 with HMS ''Erebus'' and HMS ''Terror'', and was named after Francis Crozier, captain of HMS ' ...

, at the foot of Mount Terror. Here, Borchgrevink and Captain Jensen were almost drowned by a large wave caused by a calving or breakaway of ice from the adjacent Great Ice Barrier

The Ross Ice Shelf is the largest ice shelf of Antarctica (, an area of roughly and about across: about the size of France). It is several hundred metres thick. The nearly vertical ice front to the open sea is more than long, and between hi ...

. Following the path of James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross (15 April 1800 – 3 April 1862) was a British Royal Navy officer and polar explorer known for his explorations of the Arctic, participating in two expeditions led by his uncle John Ross, and four led by William Edwa ...

sixty years previously, they proceeded eastwards along the Barrier edge, to find the inlet where, in 1843, Ross had reached his farthest south

Farthest South refers to the most southerly latitude reached by explorers before the first successful expedition to the South Pole in 1911. Significant steps on the road to the pole were the discovery of lands south of Cape Horn in 1619, Captai ...

. Observations indicated that the Barrier edge had moved some 30 statute miles (50 km) south since Ross's time, which meant that the ship were already south of Ross's record. Borchgrevink was determined to make a landing on the Barrier itself, and in the vicinity of Ross's inlet he found a spot where the ice sloped sufficiently to suggest that a landing was possible. On 16 February he, Colbeck and Savio landed with dogs and a sledge, ascended to the Barrier surface, and then journeyed a few miles south to a point which they calculated as 78°50′S, a new Farthest South record. They were the first persons to travel on the Barrier surface, earning Amundsen's approbation: "We must acknowledge that, by ascending the Barrier, Borchgrevink opened the way to the south, and threw aside the greatest obstacle to the expeditions that followed".Amundsen, Vol I, pp. 25–26

Close to the same spot ten years later, Amundsen would establish his base camp "Framheim", prior to his successful South Pole journey.

On its passage northward, ''Southern Cross'' halted at Franklin Island, off the Victoria Land coast, and made a series of magnetic calculations. These indicated that the location of the South Magnetic Pole was, as expected, within Victoria Land, but further north and further west than had previously been assumed. The party then sailed for home, crossing the Antarctic Circle on 28 February. On 1 April, news of their safe return was sent by telegram from Bluff, New Zealand

Bluff ( mi, Motupōhue), previously known as Campbelltown and often referred to as "The Bluff", is a town and seaport in the Southland region, on the southern coast of the South Island of New Zealand. It is the southernmost town in mainland ...

.

Aftermath

''Southern Cross'' returned to England in June 1900, to a cool welcome; public attention was distracted by the preparations for the upcoming Discovery Expedition, due to sail the following year. Borchgrevink meanwhile pronounced his voyage a great success, stating: "The Antarctic regions might be another Klondyke"—in terms of the prospects for fishing, sealing, and mineral extraction. (Results) He had proved that it was possible for a resident expedition to survive an Antarctic winter, and had made a series of geographical discoveries. These included new islands in Robertson's Bay and the Ross Sea, and the first landings on Franklin Island, Coulman Island, Ross Island and the Great Ice Barrier. The survey of the Victoria Land coast had revealed the "important geographical discovery ... of the Southern Cross Fjord, as well as the excellent camping place at the foot of Mount Melbourne". The most significant exploration achievement, Borchgrevink thought, was the scaling of the Great Ice Barrier and the journey to "the furthest south ever reached by man". Borchgrevink's account of the expedition, ''First on the Antarctic Continent'', was published the following year; the English edition, much of which may have been embroidered by Newnes's staff, was criticised for its "journalistic" style and for its bragging tone. The author, whom commentators recognised was "not known for either his modesty or his tact", embarked on a lecture tour of England and Scotland, but the reception was generally poor.

Despite the unexplained disappearance of many of Hanson's notes, Hugh Robert Mill described the expedition as "interesting as a dashing piece of scientific work". The meteorological and magnetic conditions of Victoria Land had been recorded for a full year; the location of the South Magnetic Pole had been calculated (though not visited); samples of the continent's natural fauna and flora, and of its geology, had been collected. Borchgrevink also claimed the discovery of new insect and shallow-water fauna species, proving "bi-polarity" (existence of species in proximity to the North and South poles).

The geographical establishments in Britain and abroad were slow to give formal recognition to the expedition. The Royal Geographical Society gave Borchgrevink a fellowship, and other medals and honours eventually followed from Norway, Denmark and the United States, but the expedition's achievements were not widely recognised. Markham persisted in describing Borchgrevink as cunning and unprincipled;Riffenburgh, p. 56 Amundsen's warm tribute was a lone approving voice. According to Scott's biographer David Crane, if Borchgrevink had been a British naval officer his expedition would have been treated differently, but "a Norwegian seaman/schoolmaster was never going to be taken seriously". A belated recognition came in 1930, long after Markham's death, when the Royal Geographical Society presented Borchgrevink with its Patron's Medal. It admitted that "justice had not been done at the time to the pioneer work of the ''Southern Cross'' expedition", and that the magnitude of the difficulties it had overcome had previously been underestimated. After the expedition, Borchgrevink lived quietly, largely out of the public eye. He died in Oslo on 21 April 1934.

Borchgrevink's account of the expedition, ''First on the Antarctic Continent'', was published the following year; the English edition, much of which may have been embroidered by Newnes's staff, was criticised for its "journalistic" style and for its bragging tone. The author, whom commentators recognised was "not known for either his modesty or his tact", embarked on a lecture tour of England and Scotland, but the reception was generally poor.

Despite the unexplained disappearance of many of Hanson's notes, Hugh Robert Mill described the expedition as "interesting as a dashing piece of scientific work". The meteorological and magnetic conditions of Victoria Land had been recorded for a full year; the location of the South Magnetic Pole had been calculated (though not visited); samples of the continent's natural fauna and flora, and of its geology, had been collected. Borchgrevink also claimed the discovery of new insect and shallow-water fauna species, proving "bi-polarity" (existence of species in proximity to the North and South poles).

The geographical establishments in Britain and abroad were slow to give formal recognition to the expedition. The Royal Geographical Society gave Borchgrevink a fellowship, and other medals and honours eventually followed from Norway, Denmark and the United States, but the expedition's achievements were not widely recognised. Markham persisted in describing Borchgrevink as cunning and unprincipled;Riffenburgh, p. 56 Amundsen's warm tribute was a lone approving voice. According to Scott's biographer David Crane, if Borchgrevink had been a British naval officer his expedition would have been treated differently, but "a Norwegian seaman/schoolmaster was never going to be taken seriously". A belated recognition came in 1930, long after Markham's death, when the Royal Geographical Society presented Borchgrevink with its Patron's Medal. It admitted that "justice had not been done at the time to the pioneer work of the ''Southern Cross'' expedition", and that the magnitude of the difficulties it had overcome had previously been underestimated. After the expedition, Borchgrevink lived quietly, largely out of the public eye. He died in Oslo on 21 April 1934.

References

Citations

Book sources

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{Featured article 1898 in Antarctica 1898 in science 1899 in Antarctica 1899 in science 1900 in Antarctica 1900 in science Antarctic expeditions Expeditions from the United Kingdom Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration United Kingdom and the Antarctic History of the Ross Dependency