South African republic referendum, 1960 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A referendum on becoming a republic was held in

A referendum on becoming a republic was held in

''

That year, a Commission appointed by the Broederbond, met to draft a constitution for a republic; this included future National Party ministers, such as Hendrik Verwoerd,

That year, a Commission appointed by the Broederbond, met to draft a constitution for a republic; this included future National Party ministers, such as Hendrik Verwoerd,

''

In Natal, the only province with an

In Natal, the only province with an

The pro-republic campaign focused on the need for white unity in the face of British decolonisation in Africa, and the eruption of the former

The pro-republic campaign focused on the need for white unity in the face of British decolonisation in Africa, and the eruption of the former

Roger B. Beck, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, page 147 It also argued that South Africa's links with the British monarchy led to confusion about the country's status, with one advertisement proclaiming: "Let us become a real republic now rather than remain betwixt and between". One campaign poster used the slogan "To re-unite and keep South Africa white, a republic now" on posters in

The opposition United Party actively campaigned for a 'No' vote, arguing that South Africa's membership of the

The opposition United Party actively campaigned for a 'No' vote, arguing that South Africa's membership of the

''

T. Davenport, C. Saunders, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, page 416 An advertisement appealing to voters who might support a republic declared: "The issue is not monarchy or republic but democracy or dictatorship".

''

''

The

The

Anthony Hocking, Macdonald South Africa, 1977, page 8 Swart had been elected as State President by Parliament by 139 votes to 71, defeating H A Fagan, the former Chief Justice, favoured by the Opposition.

Volume 125, Justice of the Peace Limited, 1961, page 1875 * Oaths of allegiance were no longer to the Queen, but to the Republic of South Africa. *

''Debates of the House of Assembly''

Volume 77, ''

South Africa Votes Republican (1960)

South Africa Goes (1961)

South Africa Inaugurates First President AKA Republic Day South Africa (1961)

Dr. Verwoerd Makes A Statement As South Africa Becomes A Republic (1961)

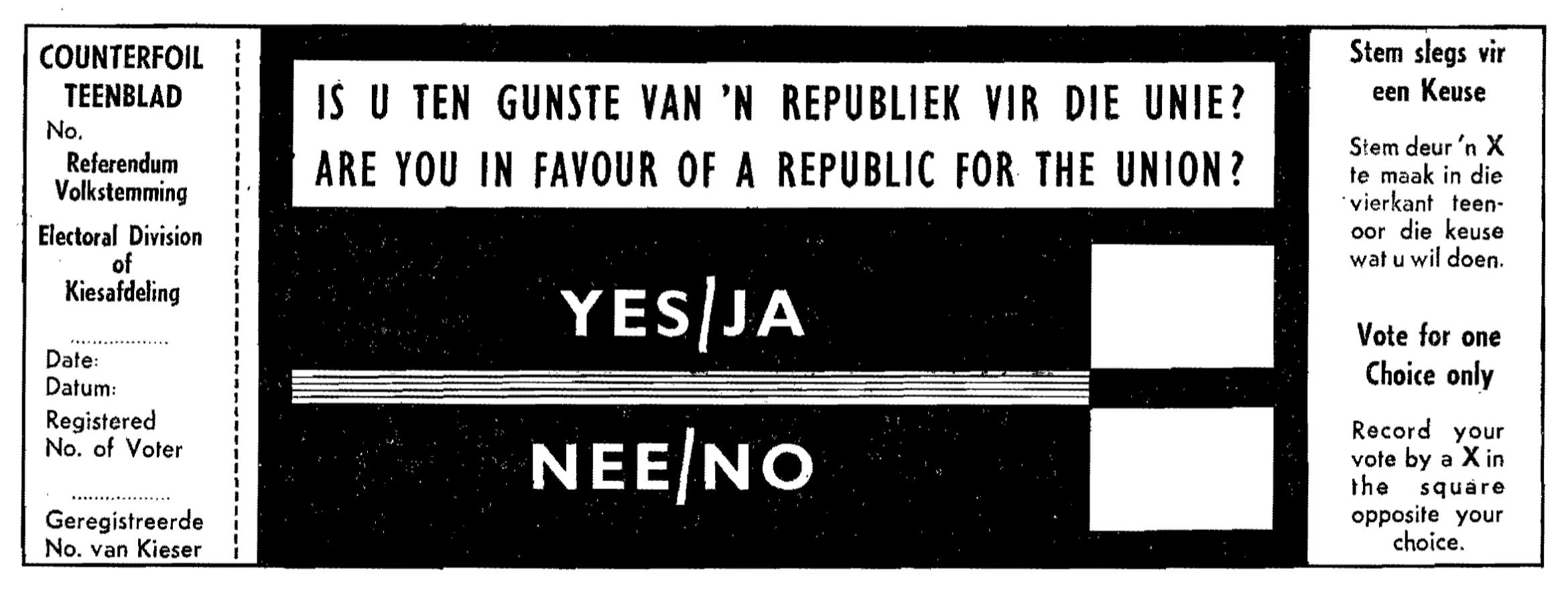

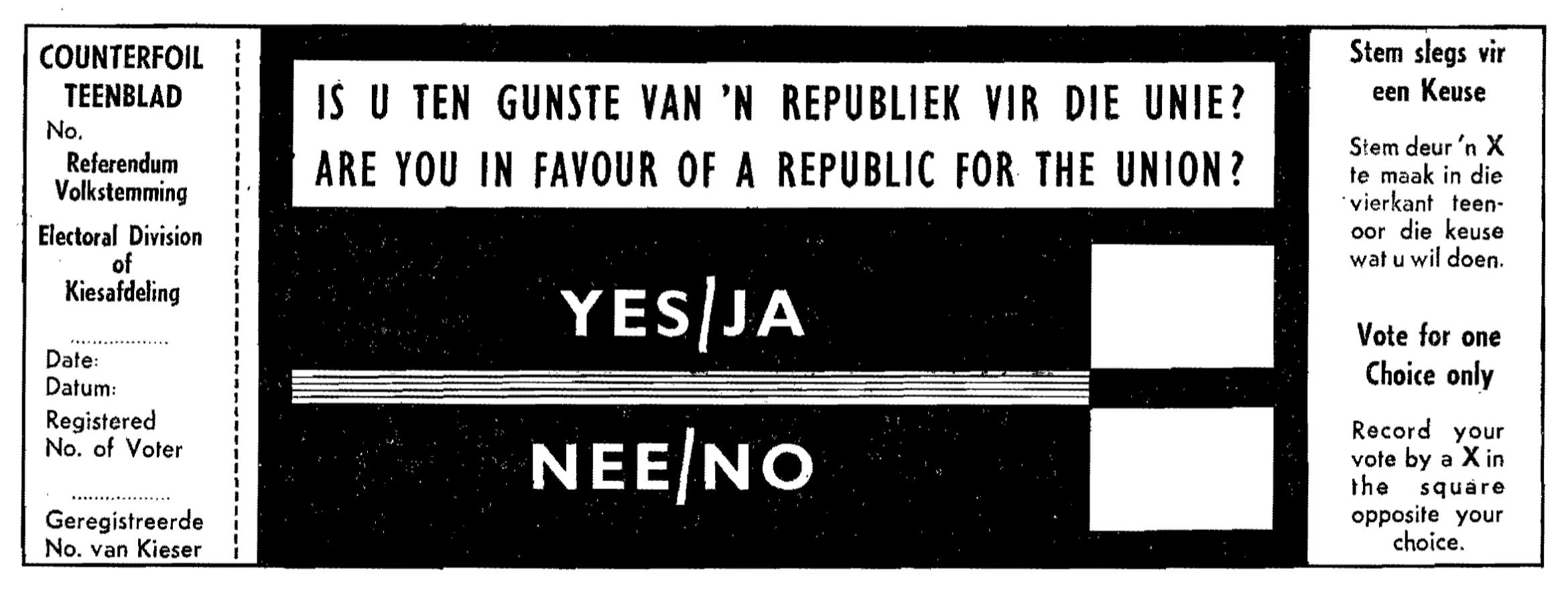

Various Referendum campaign posters for and against becoming a republic. Dated 1960.

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

on 5 October 1960. The Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Cast ...

-dominated right-wing National Party, which had come to power in 1948, was avowedly republican, and regarded the position of Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states durin ...

as head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

as a relic of British imperialism.South Africa: A War Won''

TIME

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'', 9 June 1961 The National Party government subsequently organised the referendum on whether the then Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tr ...

should become a republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

. The vote, which was restricted to whites

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

– the first such national election in the union – was narrowly approved by 52.29% of the voters. The Republic of South Africa was constituted on 31 May 1961.

Background

Afrikaner republicanism

Despite the defeat of the two Boer Republics, theSouth African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

(also known as the Transvaal) and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

, republican sentiment remained strong in the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tr ...

among Afrikaners. D F Malan broke with the National Party of Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

J. B. M. Hertzog when it merged with the South African Party of Jan Smuts to form a Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party (or "Purified National Party") which advocated a South African republic under Afrikaner control. This had the support of the secretive Afrikaner Broederbond

The Afrikaner Broederbond (AB) or simply the Broederbond was an exclusively Afrikaner Calvinist and male secret society in South Africa dedicated to the advancement of the Afrikaner people. It was founded by H. J. Klopper, H. W. van der Merwe, ...

organisation, whose chairman, L J du Plessis declared:

National culture and national welfare cannot unfold fully if the people of South Africa do not also constitutionally sever all foreign ties. After the cultural and economic needs, the Afrikaner will have to devote his attention to the constitutional needs of our people. Added to that objective must be an entirely independent genuine, Afrikaans form of government for South Africa... a form of government which through its embodiment in our own personal head of state, bone of our bone, flesh of our flesh, will inspire us to irresistible unity and strength.In 1940, Malan, along with Hertzog, founded the Herenigde Nasionale Party (or "Reunited National Party") which pledged to fight for "a free independent republic, separated from the British Crown and Empire", and "to remove, step by step, all anomalies which hamper the fullest expression of our national freedom".

That year, a Commission appointed by the Broederbond, met to draft a constitution for a republic; this included future National Party ministers, such as Hendrik Verwoerd,

That year, a Commission appointed by the Broederbond, met to draft a constitution for a republic; this included future National Party ministers, such as Hendrik Verwoerd, Albert Hertzog

Johannes Albertus Munnik Hertzog (; 4 July 1899, Bloemfontein – 5 November 1982, Pretoria) was an Afrikaner politician, cabinet minister, and founding leader of the Herstigte Nasionale Party. He was the son of J. B. M. (Barry) Hertzog, a form ...

and Eben Dönges

Theophilus Ebenhaezer Dönges (8 March 1898 – 10 January 1968) was a South African politician who was elected the state president of South Africa, but died before he could take office, aged 69.

Early life

Eben Donges was born on 8 March 189 ...

.

In 1942, details of a draft republican constitution were published in Afrikaans-language newspapers ''Die Burger

''Die Burger'' (English: The Citizen) is a daily Afrikaans-language newspaper, published by Naspers. By 2008, it had a circulation of 91,665 in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces of South Africa. Along with ''Beeld'' and ''Volksblad'', it ...

'' and '' Die Transvaler'', which provided for a State President, elected by white citizens known as ''Burgers'' only, who would be "only responsible to God... for his deeds in the fulfilment of his duties", aided by a Community Council with exclusively advisory powers, while Afrikaans would be the first official language, with English as a supplemental language.

On the matter of continued Commonwealth membership, the Broederbond's view was that "departure from the Commonwealth as soon as possible remains a cardinal aspect of our republican aim".

During the visit to South Africa by King George VI and his family in 1947, the Afrikaans-language newspaper ''Die Transvaler'', of which Verwoerd was editor, ignored the royal tour, making reference only to "busy streets" in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a Megacity#List of megacities, megacity, and is List of urban areas by p ...

. By contrast, the newspaper of the far-right Ossewa Brandwag openly denounced the tour, proclaiming that "in the name of this monarchy, 27 000 Boer women and children were murdered for the sake of gold and their fatherland".

National Party in government

In 1948, the National Party, now led byD. F. Malan

Daniël François Malan (; 22 May 1874 – 7 February 1959) was a South African politician who served as the fourth prime minister of South Africa from 1948 to 1954. The National Party implemented the system of apartheid, which enforce ...

, came to power, although it did not campaign for a republic during the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operat ...

, instead favouring remaining in the Commonwealth, thereby appealing to Afrikaners who otherwise might have voted for the United Party of Jan Smuts. This decision to downplay the republic question and focus on race issues was influenced by N C Havenga, the leader of the Afrikaner Party, which was in alliance with the National Party in the election.

Malan's successor as Prime Minister, J G Strijdom, also downplayed the republic issue, stating that no steps would be taken towards that end before 1958. However, he later reaffirmed his party's commitment to a republic, as well as a single national flag. Strijdom stated that the matter of whether South Africa would be a republic inside or outside the Commonwealth would be decided "with a view to circumstances then prevailing". Like his precessor, Strijdom declared the party's belief that a republic could only be proclaimed on the basis "of the broad will of the people".South African Republicanism''

Toledo Blade

''The Blade'', also known as the ''Toledo Blade'', is a newspaper in Toledo, Ohio published daily online and printed Thursday and Sunday by Block Communications. The newspaper was first published on December 19, 1835.

Overview

The first issue ...

'', 30 January 1958

On becoming Prime Minister in 1958, Verwoerd gave a speech to Parliament in which he declared that:

This has indeed been the basis of our struggle all these years: nationalism against imperialism. This has been the struggle since 1910: a republic as opposed to the monarchical connection... We stand unequivocally and clearly for the establishment of the republic in the correct manner and at the appropriate time.In 1960, Verwoerd announced plans to hold a whites-only referendum on the establishment of a republic, with a bill to that effect being introduced in Parliament on 23 April of that year. The Referendum Act received assent on 3 June 1960. He stated that a simple majority in favour of the change would be decisive, although minimal changes would be made to the existing constitutional structures. Before he was succeeded by Verwoerd as Prime Minister in 1958, Strijdom had lowered the voting age for whites from 21 to 18.

Afrikaners

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Cas ...

, who were more likely to favour the National Party than English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

-speaking whites

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

, were also on average younger than them, with a higher birth rate. Also included on the electoral roll were white voters in South West Africa, now Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

. As in South Africa, the Afrikaners and ethnic Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

in the territory outnumbered English-speaking whites, and were strong supporters of the National Party. In addition, Coloured

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. South ...

s were no longer enfranchised as voters and were not eligible to vote in the referendum.

In hopes of winning the support of those opposed to a republic, not only English-speaking whites but Afrikaners still supporting the United Party, Verwoerd proposed that constitutional changes would be minimal, with the Queen simply being replaced as head of state by a State President

The State President of the Republic of South Africa ( af, Staatspresident) was the head of state of South Africa from 1961 to 1994. The office was established when the country became a republic on 31 May 1961, albeit, outside the Commonweal ...

, the office of which would be a ceremonial post rather than an executive one.

Wind of Change speech

Earlier, in February of that year, BritishPrime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as " Supermac", ...

had given a speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are th ...

to the Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, in which he spoke of the inevitability of decolonisation in Africa, and appeared critical of South Africa's apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

policies. This prompted Verwoerd to declare in the House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony adm ...

:

It was not the Republic of South Africa that was told, 'We are not going to support you in this respect.' Those words were addressed to the monarchy of South Africa, and yet we have the same monarch as this person from Britain who addressed these words to us. It was a warning given to all of us, English-speaking and Afrikaans-speaking, republican and anti-republican. It was clear to all of us that as far as these matters are concerned, we shall have to stand on our own feet.Many English-speaking whites, who had regarded Britain as their spiritual home, felt disillusionment and a sense of loss, including Douglas Mitchell, the United Party's leader in Natal. Despite his opposition to Verwoerd's plans for a republic, Mitchell spoke in vehement opposition to many points of Macmillan's speech.

Opposition to republic in Natal

In Natal, the only province with an

In Natal, the only province with an English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

-speaking majority of whites, there was strong anti-republican sentiment; in 1955, the small Federal Party issued a pamphlet ''The Case Against the Republic'', while the Anti-Republican League organised public demonstrations. The League, founded by Arthur Selby, the Federal Party's chairman, launched the Natal Covenant

Ulster's Solemn League and Covenant, commonly known as the Ulster Covenant, was signed by nearly 500,000 people on and before 28 September 1912, in protest against the Third Home Rule Bill introduced by the British Government in the same year.

...

in opposition to the plans for a republic, signed by 33,000 Natalians. Drawing cheering crowds of 2,000 people in Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

and 1,500 in Pietermaritzburg

Pietermaritzburg (; Zulu: umGungundlovu) is the capital and second-largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It was founded in 1838 and is currently governed by the Msunduzi Local Municipality. Its Zulu name umGungundlovu ...

, the League became the largest political organisation in Natal, with 28 branches across the province, with Selby calling for 80,000 signatories to the Covenant. Inspired by the Ulster Covenant of 1912, the Natal Covenant read:

Being convinced in our consciences that a republic would be disastrous to the material well-being of Natal as well as of the whole of South Africa, subversive of our freedom and destructive of our citizenship, we, whose names are underwritten, men and women of Natal, loyal subjects of Her Gracious Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, do hereby pledge ourselves in solemn covenant, throughout this our time of threatened calamity, to stand by one another in defending the Crown, and in using all means which may be found possible and necessary to defeat the present intention to set up a republic in South Africa. And in the event of a republic being forced upon us, we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority. In sure confidence that God will defend the right, we hereto subscribe our names. GOD SAVE THE QUEEN.On the day of the referendum, the '' Natal Witness'', the province's daily English-language newspaper warned its readers that:

Not to vote against the Republic is to help those who would cut us loose from our moorings, and set us adrift in a treacherous and uncharted sea, at the very time that the winds of change are blowing up to hurricane force.Between May 1956 and June 1958, the anti-republican Freedom Radio, set up by John Lang, broadcast from the Natal Midlands, later resuming broadcasts shortly before the referendum in October 1960 until the proclamation of the republic in May 1961.

Black South African opinion

Black South Africans, who were denied a vote in the referendum, were not against the establishment of a republic ''per se'', but saw the new constitution as a direct rejection of the principle of one person, one vote, as expressed in theFreedom Charter

The Freedom Charter was the statement of core principles of the South African Congress Alliance, which consisted of the African National Congress (ANC) and its allies: the South African Indian Congress, the South African Congress of Democrats ...

, drafted by the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

and its allies in the Congress Alliance

The Congress Alliance was an anti-apartheid political coalition formed in South Africa in the 1950s. Led by the African National Congress, the CA was multi-racial in makeup and committed to the principle of majority rule.

Congress of the Peopl ...

. Despite its opposition to the monarchy and the Commonwealth, the ANC sought to mobilise white and black opposition to the republic, seeing it as an attempt by Verwoerd to consolidate the white grip on power.

Campaign

"Yes" campaign

The pro-republic campaign focused on the need for white unity in the face of British decolonisation in Africa, and the eruption of the former

The pro-republic campaign focused on the need for white unity in the face of British decolonisation in Africa, and the eruption of the former Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

into bloody civil war following independence, which Verwoerd warned might give rise to similar chaos in South Africa.''The History of South Africa''Roger B. Beck, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, page 147 It also argued that South Africa's links with the British monarchy led to confusion about the country's status, with one advertisement proclaiming: "Let us become a real republic now rather than remain betwixt and between". One campaign poster used the slogan "To re-unite and keep South Africa white, a republic now" on posters in

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

, while in Afrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

, the slogan was ''Ons republiek nou, om Suid-Afrika blank te hou'' ("Our republic now, to keep South Africa white"). Another poster featured two clasped hands, with the slogan "Your people, my people, our republic", which would sometimes be vandalised by painting one of the hands black, producing the emblem of the non-racial Liberal Party.

"No" campaign

The opposition United Party actively campaigned for a 'No' vote, arguing that South Africa's membership of the

The opposition United Party actively campaigned for a 'No' vote, arguing that South Africa's membership of the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

, with which it had privileged trade links, would be threatened and lead to greater isolation. One advertisement pointed out that access to Commonwealth markets was worth £200 000 000 a year. Another proclaimed "You need friends. Don't let Verwoerd lose them all". Sir De Villiers Graaff, the party's leader, called on voters to reject a republic "so we can remain in the British 'sic''Commonwealth and have its protection against Communism and hot-eyed African nationalism".Fresh Attack In Britain On Verwoerd''

Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily compact newspaper published in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, and owned by Nine. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuously published newspaper ...

'', 3 October 1960

The smaller Progressive Party appealed to supporters of the proposed change to 'reject ''this'' republic', arguing that such a weighted electorate could not provide a valid test of opinion.''South Africa: A Modern History''T. Davenport, C. Saunders, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, page 416 An advertisement appealing to voters who might support a republic declared: "The issue is not monarchy or republic but democracy or dictatorship".

Results

By province

By electoral division

Of the 156House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony adm ...

parliamentary constituencies, a majority voted for a republic in 104 (all 103 won by the National Party in the 1958 general election, plus the United Party-held seat of Sunnyside in Pretoria), while a majority voted against in the other 52 (all held by the United Party).

Aftermath

White reaction

Whites in the former Boer republics of the Transvaal andOrange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

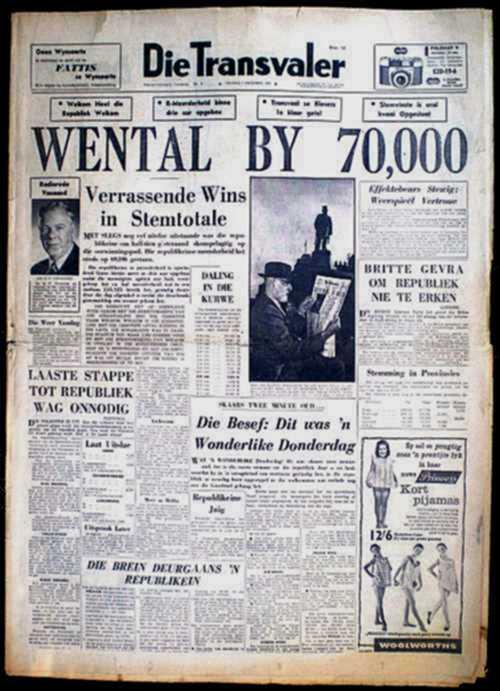

voted decisively in favour, as did those in South West Africa. On the eve of the establishment of the republic, ''Die Transvaler'' proclaimed:

Our republic is the inevitable fulfilment of God's plan for our people... a plan formed in 1652 whenIn the Cape Province there was a smaller majority, despite the removal of theJan van Riebeeck Johan Anthoniszoon "Jan" van Riebeeck (21 April 1619 – 18 January 1677) was a Dutch navigator and colonial administrator of the Dutch East India Company. Life Early life Jan van Riebeeck was born in Culemborg, as the son of a surgeon. ...arrived at the Cape... for which the defeat of our republics in 1902 was a necessary step.

Cape Coloured

Cape Coloureds () are a South African ethnic group consisted primarily of persons of mixed race and Khoisan descent. Although Coloureds form a minority group within South Africa, they are the predominant population group in the Western C ...

franchise, while Natal voted overwhelmingly against; in the constituencies of Durban North, Pinetown and Durban Musgrave, the vote against a republic was 89.7, 83.7 and 92.7 per cent respectively. Following the referendum result, Douglas Mitchell, the leader of the United Party in Natal, declared:

We in Natal will have no part or parcel of this Republic. We must resist, resist, and resist it - and the Nationalist Government. I have contracted Natal out of a republic on the strongest possible ''moral'' grounds that I can enunciate.Mitchell led a delegation from Natal seeking greater autonomy for the province, but without success. Other whites in Natal went as far as to call for

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

from the Union, along with some parts of the eastern Cape Province. However, Mitchell rejected the idea of independence as "suicide", although he did not rule out asking for it in the future.

In a conciliatory gesture to English-speaking whites, and a recognition that some had supported him in the referendum, Verwoerd appointed two English-speaking members to his cabinet.

Black reaction

On 25 March 1961, in response to the referendum, the ANC held an All-In African Congress inPietermaritzburg

Pietermaritzburg (; Zulu: umGungundlovu) is the capital and second-largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It was founded in 1838 and is currently governed by the Msunduzi Local Municipality. Its Zulu name umGungundlovu ...

attended by 1398 delegates from all over the country. It passed a resolution declaring that "no Constitution or form of Government decided without the participation of the African people who form an absolute majority of the population can enjoy moral validity or merit support either within South Africa or beyond its borders".

It called for a National Convention, and the organising of mass demonstrations on the eve of what Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (; ; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African anti-apartheid activist who served as the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was the country's first black head of state and the ...

described as "the unwanted republic", if the government failed to call one. He wrote:

The adoption of this part of the resolution did not mean that conference preferred a monarchy to a republican form of government. Such considerations were unimportant and irrelevant. The point at issue, and which was emphasised over and over again by delegates, was that a minority Government had decided to proclaim a White Republic under which the living conditions of the African people would continue to deteriorate.A three-day general strike was called in protest at the declaration of a republic, but Verwoerd responded by cancelling all police leaves, calling up 5,000 armed reservists of the Citizen Force, and ordering the arrest of thousands in black townships, although Mandela, by now head of the underground movement, managed to escape arrest.

Commonwealth reaction

Originally every independent country in theCommonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

was a Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

with the British monarch as head of state. The 1949 London Declaration prior to India becoming a republic allowed countries with a different head of state to join or remain in the Commonwealth, but only by unanimous consent of the other members. The governments of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

( in 1956) and, later, Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

( in 1960) availed themselves of this principle, and the National Party had not ruled out South Africa's continued membership of the Commonwealth were there a vote in favour of a republic.

However, the Commonwealth by 1960 included new Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

n and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n members, whose rulers saw the apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

state's membership as an affront to the organisation's new democratic principles. Julius Nyerere, then Chief Minister of Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

, indicated that his country, which was due to gain independence in 1961, would not join the Commonwealth were apartheid South Africa to remain a member. A Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference

Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences were biennial meetings of Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom and the Dominion members of the British Commonwealth of Nations. Seventeen Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences were held betwee ...

was convened in March 1961, a year ahead of schedule, to address the issue. In response, Verwoerd stirred up a confrontation, causing many members to threaten to withdraw if South Africa's renewal of membership application was accepted. As a result, South Africa's membership application was withdrawn, meaning that upon its becoming a republic on 31 May 1961, the country's Commonwealth membership simply lapsed.

Many Afrikaners welcomed this as a clean break with the colonial past, along with the recreation of the Boer republics on a larger scale. By contrast, Sir De Villiers Graaff remarked "how utterly alone and isolated our country has become", and called for another referendum on the republic issue, arguing that the end to Commonwealth membership had dramatically changed the situation.Decision to quit was "inevitable"''

The Sun-Herald

''The Sun-Herald'' is an Australian newspaper published in tabloid or compact format on Sundays in Sydney by Nine Publishing. It is the Sunday counterpart of ''The Sydney Morning Herald''. In the 6 months to September 2005, ''The Sun-Herald'' ...

'', 19 March 1961 Commenting on the enthusiastic welcome Verwoerd received from his supporters on his return, Douglas Mitchell remarked "They are cheering because we have withdrawn from the world. Will they cheer when the world withdraws from us?"

In a speech made following the announcement, Verwoerd said:

I appeal to the English-speaking people of South Africa not to allow themselves to be hurt, though I can feel their sadness. A framework has fallen away, but what is of greater importance is friendship and getting together as one nation – as white people who have to defend their future together. Now there is a chance of standing together – one free country standing together on a basis which is the desire of friendship with Great Britain.Following the end of apartheid, South Africa rejoined the Commonwealth, thirty-three years to the day that the republic was established.South Africa returns to the Commonwealth fold

''

The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publish ...

'', 31 May 1994

Establishment of Republic

Inauguration of State President

The

The Republic of South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countr ...

was declared on 31 May 1961, Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

ceased to be head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and ...

, and the last Governor General of the Union, Charles R. Swart, took office as the first State President

The State President of the Republic of South Africa ( af, Staatspresident) was the head of state of South Africa from 1961 to 1994. The office was established when the country became a republic on 31 May 1961, albeit, outside the Commonweal ...

.''South African Government''Anthony Hocking, Macdonald South Africa, 1977, page 8 Swart had been elected as State President by Parliament by 139 votes to 71, defeating H A Fagan, the former Chief Justice, favoured by the Opposition.

Legal and heraldic changes

Other symbolic changes also occurred: * Legal references to "the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

" were replaced by those to "the State".''Justice of the Peace and Local Government Review''Volume 125, Justice of the Peace Limited, 1961, page 1875 * Oaths of allegiance were no longer to the Queen, but to the Republic of South Africa. *

Queen's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel (post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister o ...

s became known as Senior Counsels.

* The "Royal" title was dropped from the names of some South African Army

The South African Army is the principal land warfare force of South Africa, a part of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), along with the South African Air Force, South African Navy and South African Military Health Servic ...

regiments, such as the Natal Carbineers

The Ingobamakhosi Carbineers (formerly Natal Carbineers) is an infantry unit of the South African Army.

History Origins

The regiment traces its roots to 1854 but it was formally raised on 15 January 1855 and gazetted on 13 March of that year, ...

. However, some institutions retained the "Royal" title, such as the Royal Natal National Park

Royal Natal National Park is a park in KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa and forms part of the uKhahlamba Drakensberg Park World Heritage Site. Notwithstanding the name, it is actually not a South African National Park managed by the SANPa ...

and the Royal Society of South Africa

*The mace in the House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony adm ...

, featuring the Crown at its head, was replaced by a new mace with the coats of arms of the four provinces, as well as sailing ships and ox wagons.

Despite the change to republican status, the coat of arms of Natal

The coat of arms of Natal was the official heraldic symbol of Natal as a British colony from 1907 to 1910, and as a province of South Africa from 1910 to 1994. It is now obsolete.

History

As a British colony, Natal's first official symbol was a ...

continued to display a crown, which had only been added to the arms in 1954, although this was neither the St Edward's Crown, with which the Queen had been crowned, nor the Tudor Crown, used by previous British monarchs, but a distinctive design.

Other references to the monarchy had been removed before the establishment of a republic:

*In 1952, the title

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

of South African Navy

The South African Navy (SA Navy) is the naval warfare branch of the South African National Defence Force.

The Navy is primarily engaged in maintaining a conventional military deterrent, participating in counter-piracy operations, fishery pro ...

vessels HMSAS (His Majesty's South African Ship) had been changed to SAS (South African Ship)

*In 1957, the Crown had been removed from the badges of the defence force and police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

,South African RepublicanismReuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters Corporation. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency was est ...

, ''Toledo Blade

''The Blade'', also known as the ''Toledo Blade'', is a newspaper in Toledo, Ohio published daily online and printed Thursday and Sunday by Block Communications. The newspaper was first published on December 19, 1835.

Overview

The first issue ...

'', 30 January 1958 or replaced with the Union Lion from the crest of the country's coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldic visual design on an escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the latter two being outer garments). The coat of arms on an escutcheon forms the central element of the full heraldic achievement, which in its ...

*In 1958, the inscription '" O.H.M.S." (On Her Majesty's Service), used on official mail, was replaced with "On Government Service".

The new decimalised currency, the Rand, which did not feature the Queen's portrait on either notes or coinage, had been introduced on 14 February 1961, three months before the establishment of the Republic. Prior to its introduction, the government considered removing the Queen's head from the coinage of the South African pound

The pound (Afrikaans: ''pond''; symbol £, £SA for distinction) was the currency of the Union of South Africa from the formation of the country as a British Dominion in 1910. It was replaced by the rand in 1961 when South Africa decimalised.

In ...

.

Constitutional changes

The most notable difference between the Constitution of the Republic and that of the Union was that the State President was the ceremonial head of state, in place of the Queen and Governor-General. The title of "State President" (''Staatspresident'' inAfrikaans

Afrikaans (, ) is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular of Holland proper (i.e., the Hollandic dialect) used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and their enslaved people. Afrikaans gr ...

) was previously used for the heads of state of both the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when i ...

and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

.

The National Party decided against having an executive presidency, instead adopting a minimalist approach, as a conciliatory gesture to whites who were opposed to a republic; the office did not become an executive post until 1984. Similarly, the Union Jack

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

remained a feature of the country's flag until 1994, despite its unpopularity among many Afrikaners, and a proposal to adopt a new design on the tenth anniversary of the republic in 1971.

Under the new Constitution, Afrikaans and English remained official languages, but the status of Afrikaans in relation to Dutch was altered; whereas the South Africa Act had made Dutch an official language alongside English, with Dutch defined to include Afrikaans under the Official Languages of the Union Act in 1925, the 1961 Constitution reversed this by making Afrikaans an official language alongside English, defining Afrikaans to include Dutch.

Public holidays

The change in South Africa's constitutional status also resulted in changes to the country'spublic holidays

A public holiday, national holiday, or legal holiday is a holiday generally established by law and is usually a non-working day during the year.

Sovereign nations and territories observe holidays based on events of significance to their history ...

, with the Queen's Birthday, commemorated on the second Monday in July, being replaced by Family Day, while Union Day, commemorating the establishment of the Union on 31 May, became Republic Day. Empire Day, which was commemorated on 24 May, but had come to be seen as an anachronism, had been abolished in 1952.Volume 77, ''

Cape Times

The ''Cape Times'' is an English-language morning newspaper owned by Independent News & Media SA and published in Cape Town, South Africa.

the newspaper had a daily readership of 261 000 and a circulation of 34 523. By the fourth quarter of ...

'', 1952, page 1495

Notes

References

External links

South Africa Votes Republican (1960)

British Pathé

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

South Africa Goes (1961)

British Pathé

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

South Africa Inaugurates First President AKA Republic Day South Africa (1961)

British Pathé

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Dr. Verwoerd Makes A Statement As South Africa Becomes A Republic (1961)

British Pathé

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Various Referendum campaign posters for and against becoming a republic. Dated 1960.

University of South Africa

The University of South Africa (UNISA), known colloquially as Unisa, is the largest university system in South Africa by enrollment. It attracts a third of all higher education students in South Africa. Through various colleges and affiliates, U ...

{{Political history of South Africa

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...

Referendums in South Africa

Republic referendum

Events associated with apartheid

Republicanism in South Africa

South Africa and the Commonwealth of Nations

Constitutional referendums

Monarchy referendums

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring coun ...