Souliotes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Souliotes were an Orthodox Christian Albanian tribal community in the area of Souli in

Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society

'. Hurst, Oxford 2002, S. 178. ootnote“The Souliotes were a warlike Albanian Christian community, which resisted Ali Pasha in Epirus in the years immediately preceding the outbreak the Greek War of Independence in 1821.” * Miranda Vickers: ''The Albanians: A Modern History''. I.B. Tauris, 1999, , S. 20. “The Suliots, then numbering around 12,000, were Christian Albanians inhabiting a small independent community somewhat akin to that of the Catholic Mirdite tribe to the north”. * Nicholas Pappas: ''Greeks in Russian Military Service in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries''. Institute for Balkan Studies. Monograph Series, No. 219, Thessaloniki 1991, . * Fleming K. (2014), p.59 * André Gerolymatos: ''The Balkan Wars: Conquest, Revolution, and Retribution from the Ottoman Era to the Twentieth Century and Beyond''. Basic Books, 2002, , S. 141. “The Suliot dance of death is an integral image of the Greek revolution and it has been seared into the consciousness of Greek schoolchildren for generations. Many youngsters pay homage to the memory of these Orthodox Albanians each year by recreating the event in their elementary school pageants.” * Henry Clifford Darby: ''Greece''. Great Britain Naval Intelligence Division. University Press, 1944. “… who belong to the Cham branch of south Albanian Tosks (see volume I, pp. 363–5). In the mid-eighteenth century these people (the Souliotes) were a semi-autonomous community …” * Arthur Foss (1978). ''Epirus''. Faber. pp. 160–161. “The Souliots were a tribe or clan of Christian Albanians who settled among these spectacular but inhospitable mountains during the fourteenth or fifteenth century…. The Souliots, like other Albanians, were great dandies. They wore red skull caps, fleecy capotes thrown carelessly over their shoulders, embroidered jackets, scarlet buskins, slippers with pointed toes and white kilts.” * Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer (1983), "Of Suliots, Arnauts, Albanians and Eugène Delacroix". ''The Burlington Magazine''. p. 487. “The Albanians were a mountain population from the region of Epirus, in the north-west part of the Ottoman Empire. They were predominantly Muslim. The Suliots were a Christian Albanian tribe, which in the eighteenth century settled in a mountainous area close to the town of Jannina. They struggled to remain independent and fiercely resisted Ali Pasha, the tyrannic ruler of Epirus. They were defeated in 1822 and, banished from their homeland, took refuge in the Ionian Islands. It was there that Lord Byron recruited a number of them to form his private guard, prior to his arrival in Missolonghi in 1824. Arnauts was the name given by the Turks to the Albanians”. The first historical account of rebellious activity in Souli dates from 1685. During the 18th century, the Souliotes expanded their territory of influence. As soon as Ali Pasha became the local Ottoman ruler in 1789 he immediately launched successive expeditions against Souli. However, the numerical superiority of his troops was not enough. The siege against Souli was intensified from 1800 and in December 1803 the Souliotes concluded an armistice and agreed to abandon their homeland. Most of them were exiled in the Ionian Islands and with the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence they were among the first communities to take arms against the Ottomans. Following the successful struggle for independence, they settled in parts of the newly established Greek state and assimilated into the Greek nation, with many attaining high posts in the Greek government, including that of

The Souliotes ( gr, Σουλιώτες; sq, Suljotë) were named after the village of Souli ( sq, Suli), a hilltop settlement in modern

The Souliotes ( gr, Σουλιώτες; sq, Suljotë) were named after the village of Souli ( sq, Suli), a hilltop settlement in modern

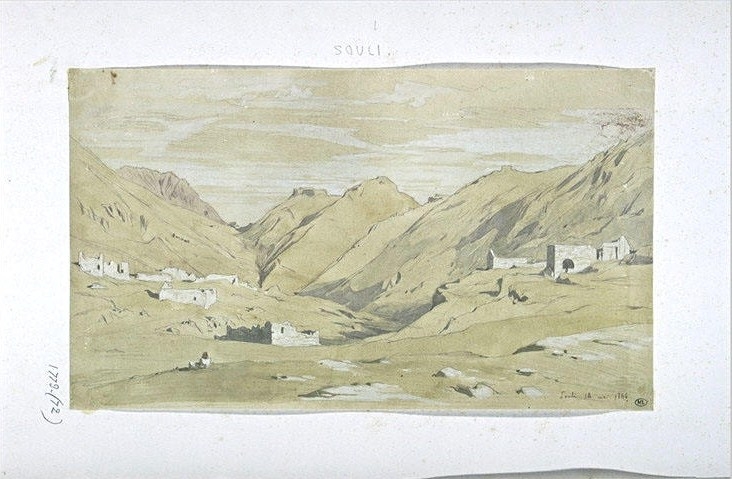

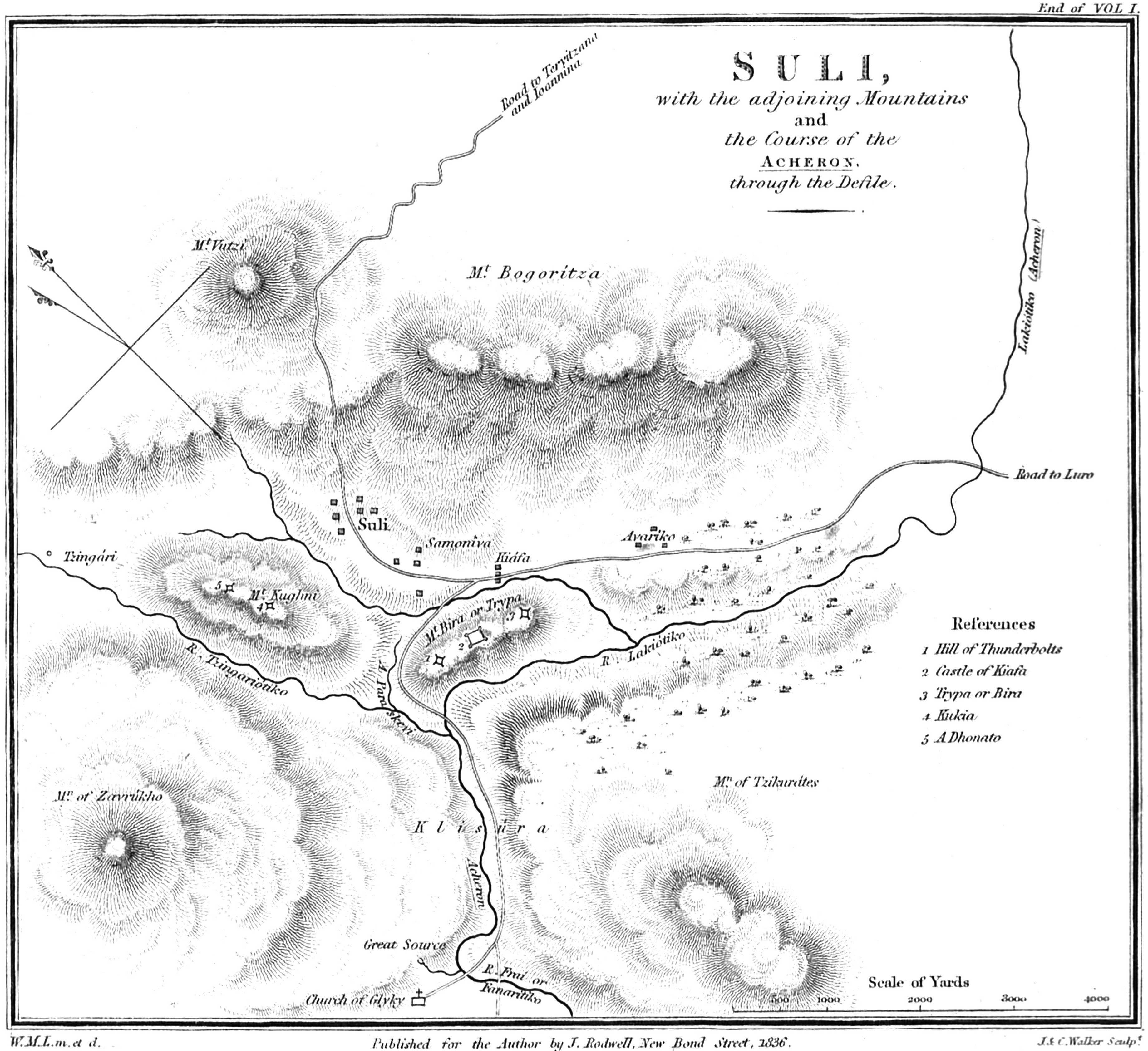

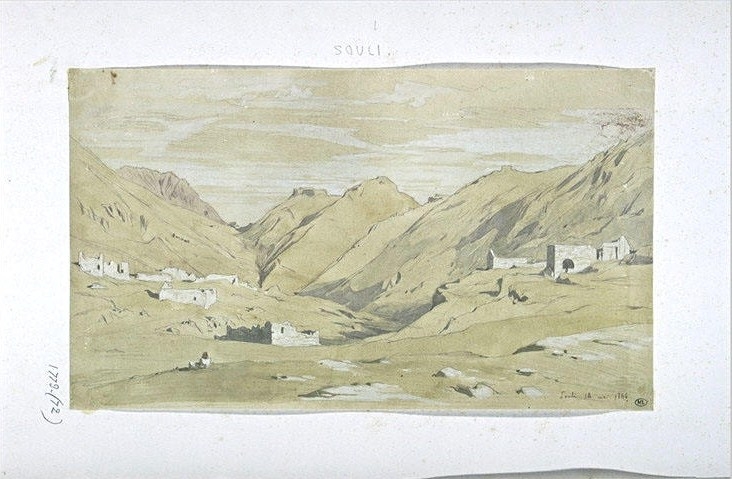

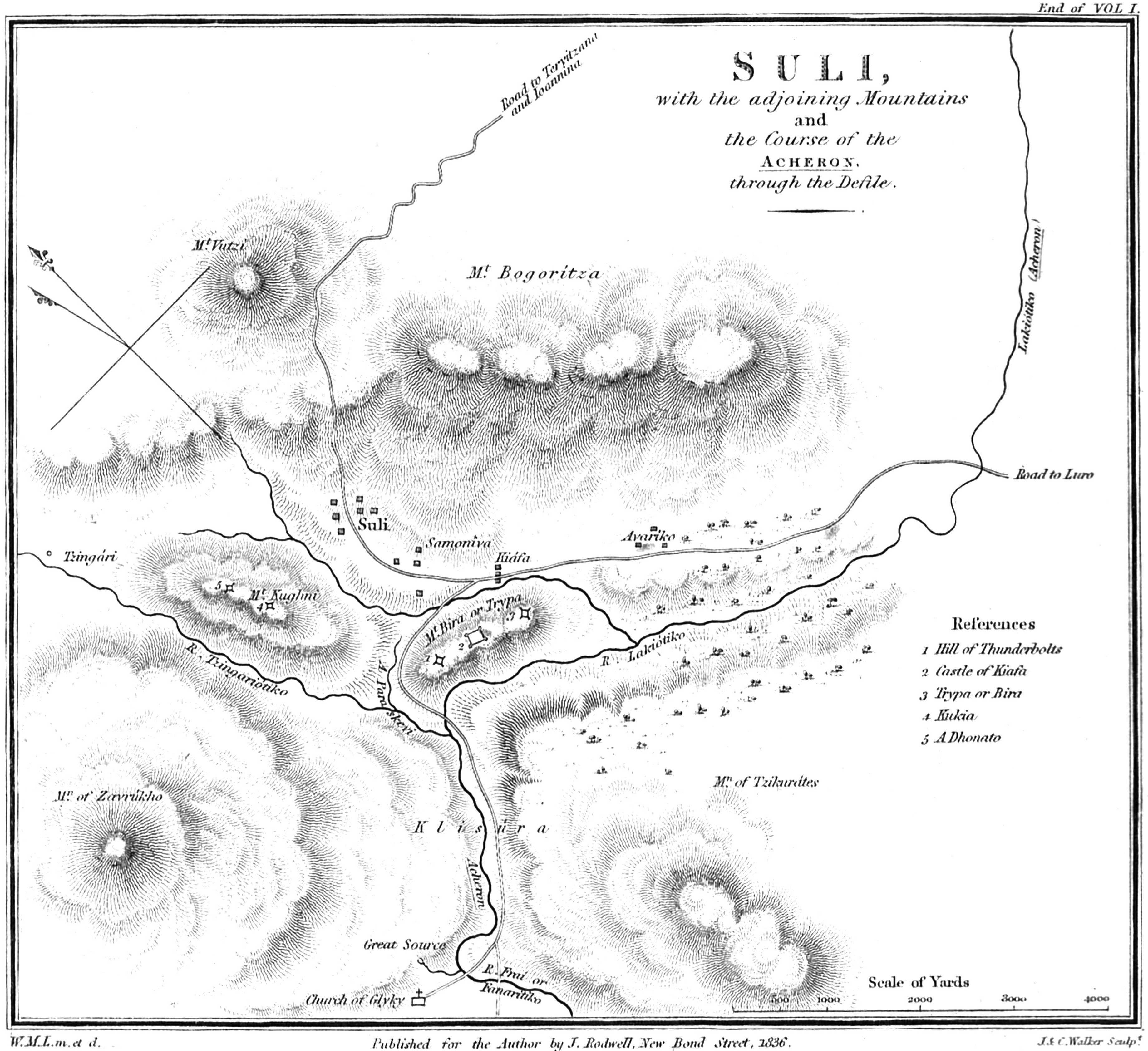

The core of Souli consisted of four villages ( el, Τετραχώρι), namely: Souli (also known as Kakosouli), Avariko (also known as Navariko), Kiafa and Samoniva.Biris, K. ''Αρβανίτες, οι Δωριείς του νεότερου Ελληνισμού: H ιστορία των Ελλήνων Αρβανιτών''. Arvanites, the Dorians of modern Greece: History of the Greek Arvanites" Athens, 1960 (3rd ed. 1998: ). In time the confederation expanded and included additional seven villages ( el, Επταχώρι). The latter became the outer defensive ring in case of an attack. Both groups of villages were also collectively called Souli. At the peak of their power, in 1800, Souliot leaders estimated that their community numbered c. 20,000 inhabitants. Vasso Psimouli estimates a total population of c. 4,500 for the Souliot villages. Of these, she estimates that up to 1,250 were living in the "eptachori", among whom 500 were armed, according to Perraivos, organized in 18 clans, while the other 3,250, in 31 clans, were living in the "tetrachori" and provided c. 1200 armed men.

Several surrounding villages, c. 50–66, which became part of the Souliote confederation were known as Parasouli. Parasouliotes could join the Souliotes to armed operations but they had no representation in the Souliote government. In case they displayed distinction in warfare they received permission to settle in Souliote villages and enjoyed the same rights and duties as the Souliotes.

The core of Souli consisted of four villages ( el, Τετραχώρι), namely: Souli (also known as Kakosouli), Avariko (also known as Navariko), Kiafa and Samoniva.Biris, K. ''Αρβανίτες, οι Δωριείς του νεότερου Ελληνισμού: H ιστορία των Ελλήνων Αρβανιτών''. Arvanites, the Dorians of modern Greece: History of the Greek Arvanites" Athens, 1960 (3rd ed. 1998: ). In time the confederation expanded and included additional seven villages ( el, Επταχώρι). The latter became the outer defensive ring in case of an attack. Both groups of villages were also collectively called Souli. At the peak of their power, in 1800, Souliot leaders estimated that their community numbered c. 20,000 inhabitants. Vasso Psimouli estimates a total population of c. 4,500 for the Souliot villages. Of these, she estimates that up to 1,250 were living in the "eptachori", among whom 500 were armed, according to Perraivos, organized in 18 clans, while the other 3,250, in 31 clans, were living in the "tetrachori" and provided c. 1200 armed men.

Several surrounding villages, c. 50–66, which became part of the Souliote confederation were known as Parasouli. Parasouliotes could join the Souliotes to armed operations but they had no representation in the Souliote government. In case they displayed distinction in warfare they received permission to settle in Souliote villages and enjoyed the same rights and duties as the Souliotes.

The Souliotes were organized in patrilineal clans which they called in Albanian '' farë'' (def. ''fara'', pl. ''farat'' "tribe"). Membership in the fara was exclusively decided via patrilineality. Indicative of this condition is the translation of M. Botsaris of the Greek term ''genos'' which is the exact equivalent to ''fara'' as ''gjish'' which in Albanian means grandfather. Each fara was formed by the descendants of a common patrilineal progenitor whose personal name became the clan name of the entire fara. It was led by a single clan leader who was its representative, although this practice was under constant negotiation as a leader may not have been acceptable by all members of the fara. Each clan was further divided in brotherhoods. As such, in time, it had the tendency to branch out in new clans which were formed as the original one grew in size and could no longer hold its cohesion as one unit under one leader. Members of the fara enjoyed privileges of settlement in specific villages and had the right to use in common specific natural resources (water springs, grazing grounds) which had been assigned to it.

All heads of clans gathered in the general assembly which

The Souliotes were organized in patrilineal clans which they called in Albanian '' farë'' (def. ''fara'', pl. ''farat'' "tribe"). Membership in the fara was exclusively decided via patrilineality. Indicative of this condition is the translation of M. Botsaris of the Greek term ''genos'' which is the exact equivalent to ''fara'' as ''gjish'' which in Albanian means grandfather. Each fara was formed by the descendants of a common patrilineal progenitor whose personal name became the clan name of the entire fara. It was led by a single clan leader who was its representative, although this practice was under constant negotiation as a leader may not have been acceptable by all members of the fara. Each clan was further divided in brotherhoods. As such, in time, it had the tendency to branch out in new clans which were formed as the original one grew in size and could no longer hold its cohesion as one unit under one leader. Members of the fara enjoyed privileges of settlement in specific villages and had the right to use in common specific natural resources (water springs, grazing grounds) which had been assigned to it.

All heads of clans gathered in the general assembly which

The Souliots were subject to a ''

The Souliots were subject to a ''

The Souliots spoke Albanian, being the descendants of an Albanian pastoral group that had settled in the area, while, due to their communication and exchanges with the mostly Greek-speaking population of surrounding areas and the importance of their economic and military presence during the eighteenth century, learnt to use also Greek. For the social use of each language,

The Souliots spoke Albanian, being the descendants of an Albanian pastoral group that had settled in the area, while, due to their communication and exchanges with the mostly Greek-speaking population of surrounding areas and the importance of their economic and military presence during the eighteenth century, learnt to use also Greek. For the social use of each language,

The first historical account of anti-Ottoman activity in Souli dates from the Ottoman-Venetian War of 1684–89. In particular in 1685, the Souliotes together with the inhabitants of Himara revolted and overthrew the local Ottoman authorities. This uprising was short-lived due to the reaction of the local Ottoman beys, agas and pashas.

Perraivos (1815) based on oral stories he collected proposed that the first attack against Souli by the Ottoman authorities occurred in 1721. Archival sources show that the campaign occurred more likely in 1731-33 and didn't have Souliotes as its specific target. In the early 18th century, the Muslim Cham beys of

The first historical account of anti-Ottoman activity in Souli dates from the Ottoman-Venetian War of 1684–89. In particular in 1685, the Souliotes together with the inhabitants of Himara revolted and overthrew the local Ottoman authorities. This uprising was short-lived due to the reaction of the local Ottoman beys, agas and pashas.

Perraivos (1815) based on oral stories he collected proposed that the first attack against Souli by the Ottoman authorities occurred in 1721. Archival sources show that the campaign occurred more likely in 1731-33 and didn't have Souliotes as its specific target. In the early 18th century, the Muslim Cham beys of

As soon as Ali Pasha became the local Ottoman ruler, he immediately launched an expedition against Souli. However, the numerical superiority of his troops was not enough and he met a humiliating defeat. Ali was forced to sign a treaty, and under its terms he had to pay wages to the Souliote leaders. On the other hand, as part of the same agreement he held five children of prominent Souliote families as hostages.Vranousis, Sfyroeras, 1997, p. 249 Ali Pasha launched successive spring-summer campaigns in 1789 and 1790. Although some Parasouliote settlements were captured, the defenders of Souli managed to repulse the attacks. Despite the end of the Russo-Turkish War, Ali Pasha was obsessed to capture this centre of resistance. Thus, he looked forward to implement indirect and long-term strategies since the numerical superiority of his troops proved inadequate.

In July 1792 Ali dispatched an army of c. 8,000–10,000 troops against the Souliotes. It initially managed to push the 1,300 Souliote defenders to the inner defiles of Souli and temporarily occupied the main settlement of the region. However, after a successful counterattack, the Ottoman Albanian units were routed with 2,500 of them killed. On the other hand, the Souliotes suffered minimal losses, but Lambros Tzavelas, one of their main leaders, was mortally wounded. The 1792 attack ended in Souliote victory and in the negotiations, the Botsaris clan managed to be recognized by Ali Pasha as the lawful representative of Souli and George Botsaris as the one who would enforce the terms of peace among the Souliotes.

During the following seven years Ali Pasha undertook preparations to take revenge for the defeat. Meanwhile, he besieged the French-controlled towns of the Ionian coast. Especially two of them, Preveza and

As soon as Ali Pasha became the local Ottoman ruler, he immediately launched an expedition against Souli. However, the numerical superiority of his troops was not enough and he met a humiliating defeat. Ali was forced to sign a treaty, and under its terms he had to pay wages to the Souliote leaders. On the other hand, as part of the same agreement he held five children of prominent Souliote families as hostages.Vranousis, Sfyroeras, 1997, p. 249 Ali Pasha launched successive spring-summer campaigns in 1789 and 1790. Although some Parasouliote settlements were captured, the defenders of Souli managed to repulse the attacks. Despite the end of the Russo-Turkish War, Ali Pasha was obsessed to capture this centre of resistance. Thus, he looked forward to implement indirect and long-term strategies since the numerical superiority of his troops proved inadequate.

In July 1792 Ali dispatched an army of c. 8,000–10,000 troops against the Souliotes. It initially managed to push the 1,300 Souliote defenders to the inner defiles of Souli and temporarily occupied the main settlement of the region. However, after a successful counterattack, the Ottoman Albanian units were routed with 2,500 of them killed. On the other hand, the Souliotes suffered minimal losses, but Lambros Tzavelas, one of their main leaders, was mortally wounded. The 1792 attack ended in Souliote victory and in the negotiations, the Botsaris clan managed to be recognized by Ali Pasha as the lawful representative of Souli and George Botsaris as the one who would enforce the terms of peace among the Souliotes.

During the following seven years Ali Pasha undertook preparations to take revenge for the defeat. Meanwhile, he besieged the French-controlled towns of the Ionian coast. Especially two of them, Preveza and

In 1803 the position of the Souliotes became desperate with the artillery and famine depleting their ranks. On the other hand, the defenders in Souli sent delegations to the Russian Empire, the Septinsular Republic and France for urgent action but without success. As the situation became more desperate in the summer of the same year, Ali's troops began assaults against the seven core villages of Souli. Meanwhile, the British turned to the Ottoman Empire in order to strengthen their forces against

In 1803 the position of the Souliotes became desperate with the artillery and famine depleting their ranks. On the other hand, the defenders in Souli sent delegations to the Russian Empire, the Septinsular Republic and France for urgent action but without success. As the situation became more desperate in the summer of the same year, Ali's troops began assaults against the seven core villages of Souli. Meanwhile, the British turned to the Ottoman Empire in order to strengthen their forces against

Many Souliotes entered service with the Russians on

Many Souliotes entered service with the Russians on

Colonel Minot, the commander of the regiment, appointed as battalion captains mostly the leaders of Souliote clans who enjoyed the respect among the soldiers. Among them were: Tussa Zervas, George Dracos, Giotis Danglis, Panos Succos, Nastullis Panomaras, Kitsos Palaskas, Kitsos Paschos. Fotos Tzavellas, Veicos Zervas. During the Anglo-French struggle over the Ionian Islands between 1810 and 1814, the Souliotes in French service faced off against other refugees organized by the British into the Greek Light Infantry Regiment. Since the Souliotes were mostly garrisoned on Corfu, which remained under French control until 1814, very few entered British service. The British disbanded the remnants of the Souliot Regiment in 1815 and subsequently decommissioned their own two Greek Light Regiments. This left many of the Souliotes and other military refugees without livelihoods. In 1817, a group of veterans of Russian service on the Ionian Islands traveled to Russia to see if they could get patents of commission and employment in the Russian army. While unsuccessful in this endeavor, they joined the '' Filiki Etaireia'' ("Company of Friends"), the secret society founded in Odessa in 1814 for the purpose of liberating Greek lands from Ottoman rule. They returned to the Ionian Islands and elsewhere and began to recruit fellow veterans into the ''Philike Etaireia'', including a number of Souliot leaders.

In July 1820 the Sultan issued a hatt-ı Şerif against Ali Pasha of Yannina proclaiming him an outlaw and subsequently called Christians and Muslims persecuted by Ali to aid the Sultan's troops promising the return of their properties and villages. As in summer 1820 both the Sultan and Ali sought the military assistance of the Souliots, Ioannis Kapodistrias, the Greek serving as foreign minister of Russia, who had visited his native Corfu in 1819 and was concerned about the predicament of the Souliots, communicated to the Souliot leaders via his two brothers in Corfu his encouragement to take advantage of this opportunity in order to return to their homeland. The Souliots of Corfu promtply submitted a request to Ismail Pasha, the leader of the Sultan's army, and joined his force along with Markos Botsaris and other Souliots dispersed through Epirus. As Ismail Pasha, also known as Pashobey, temporized, fearful of the Souliots's return to their stronghold, they decided, four months later, in November 1820, to change camps and began secret negotiations with their old enemy, Ali.. In part thanks to Ali's appeal to their shared Albanian origin, but mainly after he offered to allow them to return to their land, the Souliots agreed in December to support him to lift the Sultan's siege of Yannina in return for their resettlement in Souli., . Οn December 12, the Souliotes liberated the region of Souli, both from Muslim Lab Albanians, who were previously installed by Ali Pasha as settlers, and Muslim Cham Albanians, allies of Pashobey. They also captured the Kiafa fort.

The uprising of the Souliotes, among the first to revolt against the Sultan, like the rest of the other Greek exiles in the Ionian islands, inspired the revolutionary spirit among the other Greek communities. Soon they were joined by additional Greek communities (armatoles and klephts). Later, in January 1821, even the Muslim Albanians faithful to Ali Pasha signed an alliance with them and 3,000 Christian soldiers were fighting against the Sultan in Epirus. The Souliot struggle had initially a local character, but an understanding of the Souliotes and Muslim Albanians with Ali Pasha was in accordance with the plans of

In July 1820 the Sultan issued a hatt-ı Şerif against Ali Pasha of Yannina proclaiming him an outlaw and subsequently called Christians and Muslims persecuted by Ali to aid the Sultan's troops promising the return of their properties and villages. As in summer 1820 both the Sultan and Ali sought the military assistance of the Souliots, Ioannis Kapodistrias, the Greek serving as foreign minister of Russia, who had visited his native Corfu in 1819 and was concerned about the predicament of the Souliots, communicated to the Souliot leaders via his two brothers in Corfu his encouragement to take advantage of this opportunity in order to return to their homeland. The Souliots of Corfu promtply submitted a request to Ismail Pasha, the leader of the Sultan's army, and joined his force along with Markos Botsaris and other Souliots dispersed through Epirus. As Ismail Pasha, also known as Pashobey, temporized, fearful of the Souliots's return to their stronghold, they decided, four months later, in November 1820, to change camps and began secret negotiations with their old enemy, Ali.. In part thanks to Ali's appeal to their shared Albanian origin, but mainly after he offered to allow them to return to their land, the Souliots agreed in December to support him to lift the Sultan's siege of Yannina in return for their resettlement in Souli., . Οn December 12, the Souliotes liberated the region of Souli, both from Muslim Lab Albanians, who were previously installed by Ali Pasha as settlers, and Muslim Cham Albanians, allies of Pashobey. They also captured the Kiafa fort.

The uprising of the Souliotes, among the first to revolt against the Sultan, like the rest of the other Greek exiles in the Ionian islands, inspired the revolutionary spirit among the other Greek communities. Soon they were joined by additional Greek communities (armatoles and klephts). Later, in January 1821, even the Muslim Albanians faithful to Ali Pasha signed an alliance with them and 3,000 Christian soldiers were fighting against the Sultan in Epirus. The Souliot struggle had initially a local character, but an understanding of the Souliotes and Muslim Albanians with Ali Pasha was in accordance with the plans of

In early 1823 western Central Greece was beset by infighting among

In early 1823 western Central Greece was beset by infighting among

Souliote groups had already moved during the war to areas which would form part of the Greek Kingdom. After the Greek War of Independence, the Souliotes could not return to their homeland as it remained outside the borders of the newly formed Greek state. Different groups of refugees who settled in Greece after the war despite their common status as refugees had their own peculiarities, interests and customs. The Souliotes, alongside people from the area of Arta and the rest of Epirus, in many cases insisted on being represented as a separate group in their affairs with the Greek state and maintain their own representatives. In other cases are grouped together with the other Epirote refugees as "Epirosouliotes" or just "Epirotes". The Souliots were considered to have "a sense of superiority" and were seen by some as being arrogant because they considered themselves to be superior in military affairs in their participation in the war. This feeling of superiority of Souliotes was not only directed towards other groups of refugees but also towards the central authorities. In such conditions, it was difficult for the Souliotes to follow the central government and they were constantly a source of "reaction and mutinies". A local relation from Agrinio (1836) to the central government reports that as the Souliotes were jobless and without land they had resorted to looting and robbing the local population.

Since at least 1823 when many of them moved from the Ionian islands to western Greece, the Souliotes had been aiming to settle in

Souliote groups had already moved during the war to areas which would form part of the Greek Kingdom. After the Greek War of Independence, the Souliotes could not return to their homeland as it remained outside the borders of the newly formed Greek state. Different groups of refugees who settled in Greece after the war despite their common status as refugees had their own peculiarities, interests and customs. The Souliotes, alongside people from the area of Arta and the rest of Epirus, in many cases insisted on being represented as a separate group in their affairs with the Greek state and maintain their own representatives. In other cases are grouped together with the other Epirote refugees as "Epirosouliotes" or just "Epirotes". The Souliots were considered to have "a sense of superiority" and were seen by some as being arrogant because they considered themselves to be superior in military affairs in their participation in the war. This feeling of superiority of Souliotes was not only directed towards other groups of refugees but also towards the central authorities. In such conditions, it was difficult for the Souliotes to follow the central government and they were constantly a source of "reaction and mutinies". A local relation from Agrinio (1836) to the central government reports that as the Souliotes were jobless and without land they had resorted to looting and robbing the local population.

Since at least 1823 when many of them moved from the Ionian islands to western Greece, the Souliotes had been aiming to settle in

''Encyclopædia britannica: a new survey of universal knowledge''

Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 1946, p. 957 and the

Η ελληνική κοινότητα της Αλβανίας υπό το πρίσμα της ιστορικής γεωγραφίας και δημογραφίας [The Greek Community of Albania in terms of historical geography and demography

" In Nikolakopoulos, Ilias, Kouloubis Theodoros A. & Thanos M. Veremis (eds). ''Ο Ελληνισμός της Αλβανίας [The Greeks of Albania]''. University of Athens. p. 36, 47: "Οι κατοικούντες εις Παραμυθίαν και Δέλβινον λέγονται Τζαμηδες και ο τόπος Τζαμουριά», δίδασκε ο Αθανάσιος Ψαλίδας στις αρχές του 19ου αιώνα και συνέχιζε: «Κατοικείται από Γραικούς και Αλβανούς· οι πρώτοι είναι περισσότεροι», ενώ διέκρινε τους δεύτερους σε Αλβανούς Χριστιανούς και Αλβανούς Μουσουλμάνους." Στην Τσαμουριά υπάγει επίσης την περιφέρεια της Πάργας, χωρίς να διευκρινίζει τον εθνοπολιτισμικό της χαρακτήρα, καθώς και τα χωριά του Σουλίου, κατοικούμενα από «Γραικούς πολεμιστές».

In 1813 Hobhouse stated the Souliotes "are all Greek Christians and speak Greek" and resembled more "the Albanian warrior than the Greek merchant". French historian

In 1813 Hobhouse stated the Souliotes "are all Greek Christians and speak Greek" and resembled more "the Albanian warrior than the Greek merchant". French historian

Kitsos_Tzavellas_before_and_during_the_Greek_War_of_Independence_bore_the_inscription_"descendants_of_Pyrrhus_of_Epirus.html" ;"title="Alvanites", or in other words Albanians is how Eleni Karakitsou, the wife of Markos Botsaris identifies them. It relates to an accusation against his family to answer questions in a divorce case trial filed by Markos Botsaris in 1810 in the Septinsular islands of the Ionian Sea. Among other things, Karakitsou accuses her in-laws of indifference with the words: He had everything in his hands, because my father in law and mother in law decided not catch and to kill him, like Kosta and Stathi, yet they did not do this for me and I believe they have betrayed me and such an action is owed and law for Albanians, so as to brush away those sins." According to Greek Corfiot historian Spyros Katsaros, he states that the Corfiot Orthodox Greek speaking population during the period of 1804–14 viewed the Souliotes as "Albanian refugees ... needing to be taught Greek". While K.D. Karamoutsos, a Corfiot historian of Souliote origin disputes this stating that the Souliotes were a mixed Graeco-Albanian population or ''ellinoarvanites''. The Hellenic Navy Academy says that the Souliotic war banner used by Tousias Botsaris and Kitsos Tzavellas before and during the Greek War of Independence bore the inscription "descendants of Pyrrhus of Epirus">Pyrrhus", the ancient Greek ruler of Epirus. Greek historian Vasso Psimouli states that the Souliotes were of Albanian origin, having first settled in Epirus in the 14th century and speaking Albanian at home despite not being isolated from their Greek neighbours.

Scottish historian George Finlay called them a branch of Chams, which American ethnologist Laurie Kain Hart interpreted as them having initially spoken Albanian. British academic Miranda Vickers calls them "Christian Albanians". The Canadian professor of Greek studies Andre Gerolymatos has described them as "branch of the southern Albanian Tosks" and "Christian Albanians of Suli".

Classicist David Brewer has described them as a tribe of Albanian origin that like other Albanian tribes lived by plunder and extortion on their neighbours. American professor Nicholas Pappas stated that in modern times the Souliotes have been looked upon as Orthodox Christian Albanians who identified themselves with the Greeks. According to Pappas the overwhelming majority of the Souliotic cycle of folksongs is in Greek, which is interpreted by him as a testimony to the Greek orientation of the Souliotes. Arthur Foss says that the Souliotes were an Albanian tribe, that like other Albanian tribes, were great dandies. British historian Christopher Woodhouse describes them as an independent Greek community in the late 18th century during the resistance against Ali Pasha. Richard Clogg describes them as a warlike Albanian Christian community. Koliopoulos and Veremis have described the Souliotes as being "partly hellenized Albanian". According to Koliopoulos and Veremis, when the Albanian-speaking Souliots and other non-Greek speakers had fought in the Greek revolution, no-one thought that they were less Greek than the Greek-speakers. Trencsényi and Kopecek have inferred that they were Orthodox by faith and Albanian by origin. Fleming considers the Souliotes an Orthodox Albanian people, but also Greek-speaking. She also states that the Souliote people, who practiced a form of Orthodox Christianity and spoke Greek, were seen not as Greeks but as Albanians. Peter Bartl says that the Souliotes were an Albanian tribal community of Greek Orthodox religion. Yanni Kotsonis states that the Souliots appear a puzzling case only when contemporary notions of national belonging are projected to them and that their identity was complex, as they were "Albanians, ''Romioi'' and Christians and later Greeks as well", adopting Greekness since the Greek Revolution prevailed and endured.

Thus, for Greek authors the issue of ethnicity and origins regarding the Souliotes is contested and various views exist regarding whether they were Albanian, Albanian-speaking Greeks, or a combination of Hellenised Christian Albanians and Greeks who had settled in northern Greece. The issue of the origin and ethnicity of the Souliots is very much a live and controversial issue in Greece today. Foreign writers have been equally divided. "While the Corfiot historian, K. D. Karamoutsos, in his study of Souliot genealogies (or lineages) does not disagree on the question of the vendetta, he has little time for what he considers extensive “misinformation” on the part of Katsaros. Karamoutsos has a more sympathetic view of the Souliots, insisting that no respectable historian could categorize them as members of the Albanian nation simply on the grounds that they had their roots in the centre of present-day Albania and could speak Albanian. On the contrary, he argues, they were 100% Orthodox and bilingual, speaking Greek as well as Albanian; he says that their names, customs, costumes and consciousness were Greek, and that they maintained Greek styles of housing and family structures. He accepts that some historians might place their forebears in the category of akrites, or border guards, of the Byzantine Empire. When they came to Corfu, the Souliots were usually registered in official documents, he says, as Albanesi or Suliotti. They were, he concludes, a special group, a Greek-Albanian people (ellinoarvanites). Vasso Psimouli, on the other hand, takes for granted that the Souliots were of Albanian origin. According to her, they first settled in Epirus at the end of the fourteenth century, but they were not cut off from the Greek-speaking population around them. They spoke Albanian at home but they soon began to use Greek. As these varying opinions suggest, Greek academics have not been able to agree whether the Souliots were Albanian, Albanian-speaking Greeks, or a mixture of Greeks and Hellenized Christian Albanians who had settled in northern Greece. The issue of the origin and ethnicity of the Souliots is very much a live and controversial issue in Greece today. Foreign writers have been equally divided."

The Souliotes were called Arvanites by Greek monolinguals,

Die Zagóri-Dörfer in Nordgriechenland: Wirtschaftliche Einheit–ethnische Vielfalt

he Zagori villages in Northern Greece: Economic unit – Ethnic diversity. ''Ethnologia Balkanica''. 3: 113–114. "Im Laufe der Jahrhunderte hat es mehrfach Ansiedlungen christlich-orthodoxer ''Albaner'' (sog. ''Arvaniten'') in verschiedenen Dörfern von Zagóri gegeben. Nachfolger Albanischer Einwanderer, die im 15. Jh. In den zentral- und südgriechischen Raum einwanderten, dürfte es in Zagóri sehr wenige geben (Papageorgíu 1995: 14). Von ihrer Existenz im 15. Jh. wissen wir durch albanische Toponyme (s. Ikonómu1991: 10–11). Von größerer Bedeutung ist die jüngere Gruppe der sogenannten Sulioten – meist albanisch-sprachige Bevölkerung aus dem Raum Súli in Zentral-Epirus – die mit dem Beginn der Abwanderung der Zagorisier für die Wirtschaft von Zagóri an Bedeutung gewannen. Viele von ihnen waren bereits bei ihrer Ankunft in Zagóri zweisprachig, da in Súli Einwohner griechischsprachiger Dörfer zugewandert waren und die albanischsprachige Bevölkerung des Súli-Tales (''Lakka-Sulioten'') engen Kontakt mit der griechischsprachigen Bevölkerung der weiteren Umgebung (''Para-Sulioten'') gehabt hatte (Vakalópulos 1992: 91). Viele Arvaniten heirateten in die zagorische Gesellschaft ein, andere wurden von Zagorisiern adoptiert (Nitsiákos 1998: 328) und gingen so schnell in ihrer Gesellschaft auf. Der arvanitische Bevölkerungsanteil war nicht unerheblich. Durch ihren großen Anteil an den Aufstandsbewegungen der Kleften waren die Arvaniten meist gut ausgebildete Kämpfer mit entsprechend großer Erfahrung im Umgang mit Dörfer der Zagorisier zu schützen. Viele Arvaniten nahmen auch verschiedene Hilfsarbeiten an, die wegen der Abwanderung von Zagorisiern sonst niemand hätte ausführen können, wie die Bewachung von Feldern, Häusern und Viehherden." which amongst the Greek-speaking population until the interwar period, the term ''Arvanitis'' (plural: ''Arvanites'') was used to describe an Albanian speaker regardless of their religious affiliations. "Until the Interwar period ''Arvanitis'' (plural ''Arvanitēs'') was the term used by Greek speakers to describe an Albanian speaker regardless of his/hers religious background. In official language of that time the term ''Alvanos'' was used instead. The term ''Arvanitis'' coined for an Albanian speaker independently of religion and citizenship survives until today in Epirus (see Lambros Baltsiotis and Léonidas Embirikos, “De la formation d’un ethnonyme. Le terme Arvanitis et son evolution dans l’État hellénique”, in G. Grivaud-S. Petmezas (eds.), ''Byzantina et Moderna'', Alexandreia, Athens, 2006, pp. 417–448." According to Nikolopoulou, due to their identification with Greece, they were seen as Greeks by their Muslim Albanian adversaries as well.Nikolopoulou, 2013, p. 299, "Still, regardless of ethnic roots, the Souliot identification with Greece earned them the title of "Greeks" by their Ottoman and Muslim Albanian enemies alike... identifies them as Greeks fighting the Albanians" Ali Pasha, on the other hand, established an alliance with the Souliotes in 1820 by appealing to the shared ethnic Albanian origin of the Souliotes and his Muslim Albanian forces. Religiously, the Souliotes were always members of the Christian flock of the bishopric of Paramythia and belonged to the

Souli, in Wikiquote

Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinri ...

from the 16th century to the beginning of the 19th century, who via their participation in the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

came to identify with the Greek nation.

They originated from Albanian clans that settled in the highlands of Thesprotia

Thesprotia (; el, Θεσπρωτία, ) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the Epirus region. Its capital and largest town is Igoumenitsa. Thesprotia is named after the Thesprotians, an ancient Greek tribe that inhabited the ...

in the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

and established an autonomous confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical iss ...

dominating a large number of neighboring villages in the mountainous areas of Epirus, where they successfully resisted Ottoman rule for many years. At the height of its power, in the second half of the 18th century, the Souliote confederacy is estimated to have consisted of up to 4,500 inhabitants. After the revolution, they migrated to and settled in newly independent Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

, and assimilated into the Greek people

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, othe ...

. The Souliotes were followers of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople ( el, Οἰκουμενικὸν Πατριαρχεῖον Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, translit=Oikoumenikón Patriarkhíon Konstantinoupóleos, ; la, Patriarchatus Oecumenicus Constanti ...

. They spoke the Souliotic dialect of Albanian and learnt Greek through their interaction with Greek-speakers. They are known for their military prowess, their resistance to the local ruler Ali Pasha, and later for their contribution to the Greek cause in the revolutionary war against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

under leaders such as Markos Botsaris and Kitsos Tzavelas

Kyriakos “Kitsos” Tzavelas ( el, Κυριάκος “Κίτσος” Τζαβέλας, 1800–1855) was a Souliot fighter in the Greek War of Independence and later a Hellenic Army General and Prime Minister of Greece.

Early years and Greek ...

.

* Balázs Trencsényi, Michal Kopecek: ''Discourses of Collective Identity in Central and Southeast Europe (1770–1945): The Formation of National Movements''. Central European University Press, 2006, , S. 173. “The Souliotes were Albanian by origin and Orthodox by faith”.

* Eric Hobsbawm

Eric John Ernest Hobsbawm (; 9 June 1917 – 1 October 2012) was a British historian of the rise of industrial capitalism, socialism and nationalism. A life-long Marxist, his socio-political convictions influenced the character of his work. ...

: ''Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality''. 2. Edition. Cambridge University Press, 1992, , S. 65 “Swiss nationalism is, as we know, pluri-ethnic. For that matter, if we were to suppose that the Greek mountaineers who rose against the Turks in Byron's day were nationalists, which is admittedly improbable, we cannot fail to note that some of their most formidable fighters were not Hellenes but Albanians (the Souliotes).”

* Richard Clogg: Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society

'. Hurst, Oxford 2002, S. 178. ootnote“The Souliotes were a warlike Albanian Christian community, which resisted Ali Pasha in Epirus in the years immediately preceding the outbreak the Greek War of Independence in 1821.” * Miranda Vickers: ''The Albanians: A Modern History''. I.B. Tauris, 1999, , S. 20. “The Suliots, then numbering around 12,000, were Christian Albanians inhabiting a small independent community somewhat akin to that of the Catholic Mirdite tribe to the north”. * Nicholas Pappas: ''Greeks in Russian Military Service in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries''. Institute for Balkan Studies. Monograph Series, No. 219, Thessaloniki 1991, . * Fleming K. (2014), p.59 * André Gerolymatos: ''The Balkan Wars: Conquest, Revolution, and Retribution from the Ottoman Era to the Twentieth Century and Beyond''. Basic Books, 2002, , S. 141. “The Suliot dance of death is an integral image of the Greek revolution and it has been seared into the consciousness of Greek schoolchildren for generations. Many youngsters pay homage to the memory of these Orthodox Albanians each year by recreating the event in their elementary school pageants.” * Henry Clifford Darby: ''Greece''. Great Britain Naval Intelligence Division. University Press, 1944. “… who belong to the Cham branch of south Albanian Tosks (see volume I, pp. 363–5). In the mid-eighteenth century these people (the Souliotes) were a semi-autonomous community …” * Arthur Foss (1978). ''Epirus''. Faber. pp. 160–161. “The Souliots were a tribe or clan of Christian Albanians who settled among these spectacular but inhospitable mountains during the fourteenth or fifteenth century…. The Souliots, like other Albanians, were great dandies. They wore red skull caps, fleecy capotes thrown carelessly over their shoulders, embroidered jackets, scarlet buskins, slippers with pointed toes and white kilts.” * Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer (1983), "Of Suliots, Arnauts, Albanians and Eugène Delacroix". ''The Burlington Magazine''. p. 487. “The Albanians were a mountain population from the region of Epirus, in the north-west part of the Ottoman Empire. They were predominantly Muslim. The Suliots were a Christian Albanian tribe, which in the eighteenth century settled in a mountainous area close to the town of Jannina. They struggled to remain independent and fiercely resisted Ali Pasha, the tyrannic ruler of Epirus. They were defeated in 1822 and, banished from their homeland, took refuge in the Ionian Islands. It was there that Lord Byron recruited a number of them to form his private guard, prior to his arrival in Missolonghi in 1824. Arnauts was the name given by the Turks to the Albanians”. The first historical account of rebellious activity in Souli dates from 1685. During the 18th century, the Souliotes expanded their territory of influence. As soon as Ali Pasha became the local Ottoman ruler in 1789 he immediately launched successive expeditions against Souli. However, the numerical superiority of his troops was not enough. The siege against Souli was intensified from 1800 and in December 1803 the Souliotes concluded an armistice and agreed to abandon their homeland. Most of them were exiled in the Ionian Islands and with the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence they were among the first communities to take arms against the Ottomans. Following the successful struggle for independence, they settled in parts of the newly established Greek state and assimilated into the Greek nation, with many attaining high posts in the Greek government, including that of

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

. Members of the Souliote diaspora participated in the national struggles for the incorporation of Souli to Greece, such as in the revolt of 1854 and the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and def ...

(1912–1913) with Ottoman rule ending in 1913.

Geography

Name

The Souliotes ( gr, Σουλιώτες; sq, Suljotë) were named after the village of Souli ( sq, Suli), a hilltop settlement in modern

The Souliotes ( gr, Σουλιώτες; sq, Suljotë) were named after the village of Souli ( sq, Suli), a hilltop settlement in modern Thesprotia

Thesprotia (; el, Θεσπρωτία, ) is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the Epirus region. Its capital and largest town is Igoumenitsa. Thesprotia is named after the Thesprotians, an ancient Greek tribe that inhabited the ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wi ...

. Souli gradually became the name of the entire region where the four main Souliot settlements are located (Souli, Avariko, Kiafa, Samoniva). Souli as a region is not attested in any sources before the 18th century. François Pouqueville

François Charles Hugues Laurent Pouqueville (; 4 November 1770 – 20 December 1838) was a French diplomat, writer, explorer, physician and historian, member of the Institut de France.

First as the Turkish Sultan's hostage, then as Napoleon Bo ...

, the French traveler, historian and consul in Ioannina, and others in his era theorized that the area was the ancient Greek Selaida and its modern inhabitants descendants of the Selloi, an ancient Greek tribe that inhabited the region in antiquity. This hypothesis was fueled and proposed in the context of the rise of romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

in Europe and the ideological return to the ancient past. Such views had little acceptance in historiography and were already rejected as early as the publication of the ''History of Souli'' (1815) by Christoforos Perraivos.

The origin of the toponym ''Souli'' is uncertain. Perraivos attributed the name to an Ottoman official in the region who was killed in a battle against the Souliotes, who gave his name to their village. In contemporary historiography, this theory is considered to be a constitutive myth designed to link the name of Souli with the narrative of struggles of its inhabitants against Ottoman officials. Historically, this view has been rejected as it would imply that the Souliotes had no name for their main village and region before the killing of a single Ottoman official. Fourikis (1934) goes as far as proposing that Perraivos invented this explanation himself. At the end of the 19th century Labridis proposed that ''Souli'' may derive from one of the earliest Cham Albanian

Cham Albanians or Chams ( sq, Çamë; el, Τσάμηδες, ''Tsámidhes''), are a sub-group of Albanians who originally resided in the western part of the region of Epirus in northwestern Greece, an area known among Albanians as Chameria. Th ...

clan leaders who settled in the area and gave his name to it as was the habit in tribal settlements. Fourikis (1934) rejected an origin of the toponym from a personal name and proposed that it simply derived from the Albanian word ''sul'' (mountain peak) which is found as a geographical toponym in other areas where medieval Albanian clans settled. It may also be interpreted as 'watchpost', 'lookout', or 'mountain summit'. The view of Fourikis is the most commonly accepted theory in contemporary historiography. Psimouli (2006) considers the etymological aspects in the theory of Fourikis acceptable, but rejects the view the toponym Souli emerged from the region's geomorphology, because of the fact that none of the four settlements of the ''tetrachori'' is placed on a mountaintop or an outlook but at an altitude of no more than 600 m. The author notes that while the mountain peaks which surround Souli have Albanian toponyms, none of them was actually named ''sul'' by the clans which settled there. Hence, Psimouli (2006) proposes that "Souli" or "Siouli" refers to a personal name -the first name or cognomen of the progenitor of the Albanian immigrant group that settled there - as happened in other settlements like Spata or the neighbouring Mazaraki or Mazarakia. The name itself metaphorically may have referred to his height as a tall person.

Settlements

The core of Souli consisted of four villages ( el, Τετραχώρι), namely: Souli (also known as Kakosouli), Avariko (also known as Navariko), Kiafa and Samoniva.Biris, K. ''Αρβανίτες, οι Δωριείς του νεότερου Ελληνισμού: H ιστορία των Ελλήνων Αρβανιτών''. Arvanites, the Dorians of modern Greece: History of the Greek Arvanites" Athens, 1960 (3rd ed. 1998: ). In time the confederation expanded and included additional seven villages ( el, Επταχώρι). The latter became the outer defensive ring in case of an attack. Both groups of villages were also collectively called Souli. At the peak of their power, in 1800, Souliot leaders estimated that their community numbered c. 20,000 inhabitants. Vasso Psimouli estimates a total population of c. 4,500 for the Souliot villages. Of these, she estimates that up to 1,250 were living in the "eptachori", among whom 500 were armed, according to Perraivos, organized in 18 clans, while the other 3,250, in 31 clans, were living in the "tetrachori" and provided c. 1200 armed men.

Several surrounding villages, c. 50–66, which became part of the Souliote confederation were known as Parasouli. Parasouliotes could join the Souliotes to armed operations but they had no representation in the Souliote government. In case they displayed distinction in warfare they received permission to settle in Souliote villages and enjoyed the same rights and duties as the Souliotes.

The core of Souli consisted of four villages ( el, Τετραχώρι), namely: Souli (also known as Kakosouli), Avariko (also known as Navariko), Kiafa and Samoniva.Biris, K. ''Αρβανίτες, οι Δωριείς του νεότερου Ελληνισμού: H ιστορία των Ελλήνων Αρβανιτών''. Arvanites, the Dorians of modern Greece: History of the Greek Arvanites" Athens, 1960 (3rd ed. 1998: ). In time the confederation expanded and included additional seven villages ( el, Επταχώρι). The latter became the outer defensive ring in case of an attack. Both groups of villages were also collectively called Souli. At the peak of their power, in 1800, Souliot leaders estimated that their community numbered c. 20,000 inhabitants. Vasso Psimouli estimates a total population of c. 4,500 for the Souliot villages. Of these, she estimates that up to 1,250 were living in the "eptachori", among whom 500 were armed, according to Perraivos, organized in 18 clans, while the other 3,250, in 31 clans, were living in the "tetrachori" and provided c. 1200 armed men.

Several surrounding villages, c. 50–66, which became part of the Souliote confederation were known as Parasouli. Parasouliotes could join the Souliotes to armed operations but they had no representation in the Souliote government. In case they displayed distinction in warfare they received permission to settle in Souliote villages and enjoyed the same rights and duties as the Souliotes.

Early history

Most scholars agree that the first inhabitants of Souli settled there in the middle of the 16th century as groups of shepherds. The earliest inhabitants came from southern Albania and the plains of Thesprotia. Vasso Psimouli holds that Souli was chosen as a place of permanent settlement by a subgroup of one of the two Albanian immigrant pastoralist populations that arrived in the area organized in large kinship groups ( Albanian: ''fis'') in the mid-14th century, a time of power vacuum after the death of Stefan Dušan and demographic decline of the Greek agrarian population due to theplague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

. One Albanian immigrant group, that of the Mazarakaioi, could reach the area from the north through Vagenetia, while the other from the south via Rogoi. Authors who traveled in the region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries argue that the initial core of clans which formed the Souliotes gradually grew and expanded in other settlements. George Finlay recorded that "the Chams reserve the name Suliote for 100 families who, by virtue of birth, belonged to the military caste of Suli". According to Finlay, this population increased from other immigrant clans which joined them. Modern sources argue that the gradual settlement of families and tribes of different origins in Souli unlikely, because of the lack of sources testifying the abandonment of villages in the 17th century and also due to the limited abiity of the pastures of Souli to maintain superfluous population and to the closed character of tribal organization, which is not open to accepting outsiders in mass.

The Souliote population was located in inland Thesprotia and for much of the 16th century remained away from the plagues and military events which affected coastal Epirus. This was an era of demographic increase for the area. The Souliote clans were pastoralist communities. Demographic pressure, environmental conditions and lack of grazing grounds gradually created social conditions, which led many Souliote clans to engage in pillaging and raiding other Souliote clans and primarily the neighbouring, lowland peasant communities as a means to combat lack of means of subsistence. In the 18th century, the occasional use of raiding as a means of subsistence became an institutionalized activity of Souliote clans which systematically raided the lowland peasants. The price of weapons in the 17th century had decreased which made their acquirement much easier and the naturally defensive position of Souliote clans in their hilltop settlements made immediate intervention by the Ottoman authorities difficult.

Society

Patrilineal clans

The Souliotes were organized in patrilineal clans which they called in Albanian '' farë'' (def. ''fara'', pl. ''farat'' "tribe"). Membership in the fara was exclusively decided via patrilineality. Indicative of this condition is the translation of M. Botsaris of the Greek term ''genos'' which is the exact equivalent to ''fara'' as ''gjish'' which in Albanian means grandfather. Each fara was formed by the descendants of a common patrilineal progenitor whose personal name became the clan name of the entire fara. It was led by a single clan leader who was its representative, although this practice was under constant negotiation as a leader may not have been acceptable by all members of the fara. Each clan was further divided in brotherhoods. As such, in time, it had the tendency to branch out in new clans which were formed as the original one grew in size and could no longer hold its cohesion as one unit under one leader. Members of the fara enjoyed privileges of settlement in specific villages and had the right to use in common specific natural resources (water springs, grazing grounds) which had been assigned to it.

All heads of clans gathered in the general assembly which

The Souliotes were organized in patrilineal clans which they called in Albanian '' farë'' (def. ''fara'', pl. ''farat'' "tribe"). Membership in the fara was exclusively decided via patrilineality. Indicative of this condition is the translation of M. Botsaris of the Greek term ''genos'' which is the exact equivalent to ''fara'' as ''gjish'' which in Albanian means grandfather. Each fara was formed by the descendants of a common patrilineal progenitor whose personal name became the clan name of the entire fara. It was led by a single clan leader who was its representative, although this practice was under constant negotiation as a leader may not have been acceptable by all members of the fara. Each clan was further divided in brotherhoods. As such, in time, it had the tendency to branch out in new clans which were formed as the original one grew in size and could no longer hold its cohesion as one unit under one leader. Members of the fara enjoyed privileges of settlement in specific villages and had the right to use in common specific natural resources (water springs, grazing grounds) which had been assigned to it.

All heads of clans gathered in the general assembly which Lambros Koutsonikas

Lambros Koutsonikas ( el, Λάμπρος Κουτσονίκας, 1799 – 2 June 1879) was a Greek general and fighter of the Greek Revolution of 1821, army officer and amateur historian of the Revolution.

Biography

He was the son of Yiannos, fr ...

(himself a Souliot) recorded in Greek as ''Πλεκεσία'', a term that can be linked to the Albanian '' pleqësia'' (council of elders). This acted as the highest political structure of Souliot society which was responsible for solving disputes, formulating tribal laws, arbitrage between clans in dispute and the enforcement of decisions of the council against members of the community. It was a space where the different ''fara'' of Souliot society negotiated with each other their position in Souliotic society. The assembly was held in the open courtyard next to the church of St. George in Souli. The decisions of the ''pleqësia'' were not written down but agreed upon via the oral pledge of '' besë'' (def. ''besa'') to which all heads of clans were bound. The concept of ''besa'' was the foundation for agreements not only within Souliot society but functioned as the basis for any agreements which Souliotes made with outsiders, including hostile forces in times of war. The significance of this concept is highlighted by the fact that M. Botsaris translates ''besë'' in Greek as ''threskeia'' (religion) and ''i pabesë'' ("without ''besë'') as ''apistos'' (unbeliever). As each clan acted autonomously of the general assembly of their leaders, they could sign agreements with outsiders which contradicted the agreements which the Souliot community signed as a whole and this was a common cause of friction among the Souliot clans.

A detailed recording of the Souliot clans appears for the first time by Perraivos. According to his notes, at the end of the 18th century, 450 families which belonged to 26 clans lived in the village of Souli. In Kiafa, there were 90 families which belonged to four clans. In Avariko, five families which belonged to three clans and in Samoniva 50 families which belonged to three clans. As the Souliot population, new clans were established from existing ones and formed the population of the seven villages around core Souli. There was an informal hierarchy among Souliot clans in the second half of the 18th century which was determined by the fighting power (men) of each ''fara'' and its size. The Botsaris clan was one of the oldest and most powerful in all four villages of core Souli. Georgios Botsaris in 1789 claimed that his clan could field 1,000 men against Ali Pasha followed by the Tzavellas and Zervas clans each of which could field 300 men and other smaller clans with 100 men each. George Botsaris presented himself as "the most respected individual among the Souliots" and his son Dimitris presented his father as the ''captain of the Souliots'' and himself as the ''commissioner of the Albanians''(in Greek, ''ton Arvaniton epitropikos''). It is evident that in this period of Souliot history, social stratification among the clans had created an environment which led weaker clans to coalesce around stronger ones and be represented by them. The role, however, of the ''pleqësia'' was to stop such differentiation and maintain relations of equality in the community. Until the fall of Souli in 1803, the Souliot community never accepted to have a single leader from one clan and even in times of war each clan chose its leader from its own ranks. Thus, the Souliot tribal organization remained one which preserved the collective autonomy of each clan until its end. Social stratification was expressed since the second half of the 18th century in social practices of the Souliots, but was never institutionalized.

The Souliotes wore red skull caps, fleecy capotes over their shoulders, embroidered jackets, scarlet buskins, slippers with pointed toes and white kilts.Arthur Foss (1978). ''Epirus''. Faber. pp. 160–161. “The Souliots were a tribe or clan of Christian Albanians who settled among these spectacular but inhospitable mountains during the fourteenth or fifteenth century…. The Souliots, like other Albanians, were great dandies. They wore red skull caps, fleecy capotes thrown carelessly over their shoulders, embroidered jackets, scarlet buskins, slippers with pointed toes and white kilts.”

Economy

In the mid-sixteenth century Souli is listed in a Ottoman tax register as a village inhabited by 244 taxpayers, located in the Christian ''nahiye

A nāḥiyah ( ar, , plural ''nawāḥī'' ), also nahiya or nahia, is a regional or local type of administrative division that usually consists of a number of villages or sometimes smaller towns. In Tajikistan, it is a second-level division w ...

'' of Ai-Donat, part of the homonymous ''kaza

A kaza (, , , plural: , , ; ota, قضا, script=Arab, (; meaning 'borough')

* bg, околия (; meaning 'district'); also Кааза

* el, υποδιοίκησις () or (, which means 'borough' or 'municipality'); also ()

* lad, kaza

, ...

'' of the sanjak of Delvina. In a 1613 tax list, however, Souli is one of the settlements in which some taxpayers paid ''resm-i çift

The Resm-i Çift (''Çift Akçesi'' or ''Çift resmi'') was a tax in the Ottoman Empire. It was a tax on farmland, assessed at a fixed annual rate per çift, and paid by land-owning Muslims. Some Imams and some civil servants were exempted from the ...

'' and '' resm-i bennak'', taxes paid by Muslim subjects, newcomers or converts to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

.

The Souliots were subject to a ''

The Souliots were subject to a ''sipahi

''Sipahi'' ( ota, سپاهی, translit=sipâhi, label=Persian, ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuks, and later the Ottoman Empire, including the land grant-holding (''timar'') provincial '' timarli sipahi'', which constituted ...

'', who had a degree of jurisdiction in Souli, represented them, as testified in a 1794 document, and collected a small amount of tax. The incorporation of the Souliots in the timariot system through the payment of taxes certified their legal standing, guaranteed them representation through the ''sipahi'' and allowed the continuation of their control and enrichment through activities such as brigandage and the provision of protection to subjugated populations. Perraivos records that the "sipahi

''Sipahi'' ( ota, سپاهی, translit=sipâhi, label=Persian, ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuks, and later the Ottoman Empire, including the land grant-holding (''timar'') provincial '' timarli sipahi'', which constituted ...

of Soli", Beqir Bey, was settled in Yannina and went to Souli once every year to collect taxes.

Taxation archives show that the economy of the Souliotes was based on small-scale subsistence pastoralism which due to few available grazing grounds never increased enough to become a source of commercial activity. The spahis of Souli generated little profit from their position. It seems that no Ottoman official or timariot holder of Souli lived there. This likely happened not because of Souliot hostility but because of the extended practice of Ottoman officials since the 17th century to not live on the territories they were assigned to, but in the closest large urban settlement. All archival sources show that throughout its existence the Souliotic community paid its taxes regularly and complied with Ottoman economic laws in their transactions and as such was represented in the Ottoman system, but it was not integrally included in it as its remote position and lack of natural resources didn't lead to any Ottoman presence within Souli. As a result, Psimouli (2016) describes the status of Souli as a "community without Turkish presence, but not necessarily autonomous".

Blood vengeance

Blood vengeance was one of the core social practices in Souliot society. It regulated relations between clans, the social hierarchy of Souli and the attribution of customary justice in cases of violations of clan property. Blood vengeance was ideologically linked with the concepts of honour-dishonour which was a collective trait of the entire clan. The pervasiveness of blood vengeance in Souliot society is highlighted in Souli's architecture: all houses were essentially fortified towers which were placed in strategic positions which could be defended from attacks which started from other fortified towers of Souli and even the churches hadembrasure

An embrasure (or crenel or crenelle; sometimes called gunhole in the domain of gunpowder-era architecture) is the opening in a battlement between two raised solid portions (merlons). Alternatively, an embrasure can be a space hollowed out ...

s. M. Botsaris uses the terms ''hasm'' (enemy) and ''hak'' which literally means vengeance in Albanian as the equivalent of Greek ''dikaiosyne'' (justice). The term linked to the actual practice of blood vengeance which he uses is ''gjak'' ( Gjakmarrja).

Language

The Souliots spoke Albanian, being the descendants of an Albanian pastoral group that had settled in the area, while, due to their communication and exchanges with the mostly Greek-speaking population of surrounding areas and the importance of their economic and military presence during the eighteenth century, learnt to use also Greek. For the social use of each language,

The Souliots spoke Albanian, being the descendants of an Albanian pastoral group that had settled in the area, while, due to their communication and exchanges with the mostly Greek-speaking population of surrounding areas and the importance of their economic and military presence during the eighteenth century, learnt to use also Greek. For the social use of each language, William Martin Leake

William Martin Leake (14 January 17776 January 1860) was an English military man, topographer, diplomat, antiquarian, writer, and Fellow of the Royal Society. He served in the British military, spending much of his career in the

Mediterrane ...

writes that "Souliot men spoke Albanian at home and all men could speak Greek as they were their neighbours, while many women could speak Greek too". For the movements of Souliots to the villages of Lakka Souliou

Lakka Souliou ( el, Λάκκα Σουλίου is a former municipality in the Ioannina regional unit, Epirus, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Dodoni, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal uni ...

in the 18th century, the Greek Orthodox Bishop Serafeim Byzantios notes that "as the Souliotes speak Albanian, most villages of Lakka speak Albanian, but Greek is not unknown to them". The closest existing variant of Souliotic Albanian is that of the village Anthousa (Rapëza) and also Kanallaki

Kanallaki (, ) is a settlement in the regional unit of Preveza, Epirus. It belongs to the municipality of Parga and is simultaneous the seat of it. The number of inhabitants of the town amounts to 2,491.

History

Kanallaki was one of the Christia ...

. This dialect is spoken only by few people in modern times.

Further evidence on the language of the Souliotes is drawn from the Rhomaic (Greek)-Albanian dictionary composed in 1809 mainly by Markos Botsaris and his family members. The Albanian variant in the text shows lexical influence from Greek, Turkish and other languages. Of 1494 Albanian words of the vocabulary, 361 are loanwords from Greek, 187 from Turkish, 21 from Italian and two from other languages. The Albanian entries correspond to 1701 Greek entries. Many entries are related to religion and church organization. For Jochalas who edited and published the dictionary, despite the influence of Greek on Souliotic Albanian in the entries, it is evident that Botsaris and his family members who helped him lacked structural knowledge of Greek and were very inexperienced in writing. He also observes that the Albanian phrases are syntaxed as if were Greek (Yochalas, p.53). Similar lack of knowledge of Greek grammar, syntax and spelling is observed for all of the very few written documents by Souliotes. Robert Elsie

Robert Elsie (June 29, 1950 – October 2, 2017) was a Canadian-born German scholar who specialized in Albanian literature and folklore.

Elsie was a writer, translator, interpreter, and specialist in Albanian studies, being the author of numerou ...

noted that the 1,484 Albanian lexemes "are important for our knowledge of the now extinct Suliot dialect of Albanian". In the early twentieth century among the descendants of Souliotes in the Kingdom of Greece, there was an example of Souliote still being fluent in Albanian, namely lieutenant Dimitrios (Takis) Botsaris, a direct descendant of the Botsaris' family.

The correspondence of the Souliotes to both Christian and Muslim leaders was either written in Greek or translated from Greek. Greek was commonly used in Ottoman Epirus for writing not just between Christians (including Souliotes) but even between Muslim Albanian-speakers who employed Greek secretaries as is, e.g., the case with the correspondence between the Cham beys and Ali pasha. A written account on the language Souliotes used is the diary of Fotos Tzavellas, composed during his captivity by Ali Pasha (1792–1793). This diary is written by F. Tzavellas himself in simple Greek with several spelling and punctuation mistakes. Emmanouel Protopsaltes, former professor of Modern Greek History at the University of Athens, who published and studied the dialect of this diary, concluded that Souliotes were Greek speakers originating from the area of Argyrkokastro or Chimara. Εmmanuel Protopsaltis asserted based on his reading of the texts that the national sentiment and the basic ethnic and linguistic component of Souli was Greek rather than Albanian. Psimouli criticizes the publication by Protopsaltis for its lack of critical analysis.

Toponyms

In a study by scholar Petros Fourikis examining the onomastics of Souli, most of the toponyms and micro-toponyms such as: ''Kiafa'', ''Koungi'', ''Bira'', ''Goura'', ''Mourga'', ''Feriza'', ''Stret(h)eza'', ''Dembes'', ''Vreku i Vetetimese'', ''Sen i Prempte'' and so on were found to be derived from Albanian. A study by scholar Alexandros Mammopoulos (1982 concludes that not all the toponyms of Souli were Albanian and that many derive from various other Balkan languages, including quite a few in Greek. In a 2002 study, Shkëlzen Raça states that Souliote toponyms listed by Fourikis can only be explained through Albanian. "Për më tepër, shumë nga suljotët sot vazhdojnë të përkujtojnë rrënjët e forta në viset shkëmbore të Sulit dhe nëpërmjet toponimisë nuk e kontestojnë origjinën shqiptare të tyre. Në këtë kontekst, siç bën të ditur albanologu grek me prejardhje shqiptare, Petro Furiqi (Πέτρο Φουρίκης), toponimet si: Qafa, Vira ose Bira, Breku i vetetimesë (Bregu i vetëtimës), Gura, Dhembes (Dhëmbës), Kungje, Murga e Fereza, nuk kanë si të shpjegohen ndryshe, përveçse nëpërmjet gjuhës shqipe." [Moreover, for many Souliotes today continue to commemorate the strong roots in the mountainous areas of Souli and through toponymy it does not dispute their Albanian origins. In this context, as knew the Greek albanologist of Albanian descent, Petro Furiqi (Πέτρο Φουρίκης), those toponyms are: Qafa, Vira or Bira, Breku i vetetimesë (Bregu i vetëtimës), Gura, Dhembes (Dhëmbës), Kungje, Murga and Fereza, have no other way of being explained, except through Albanian.] Vasso Psimouli states that many of the placenames of the wider area of Souli are Slavic or Aromanians, Aromanian (Zavruho, Murga, Sqapeta, Koristiani, Glavitsa, Samoniva, Avarico), while those of the core of the four Souliotic settlements are mostly Albanian.Clashes with Ottoman officials

1685–1772

The first historical account of anti-Ottoman activity in Souli dates from the Ottoman-Venetian War of 1684–89. In particular in 1685, the Souliotes together with the inhabitants of Himara revolted and overthrew the local Ottoman authorities. This uprising was short-lived due to the reaction of the local Ottoman beys, agas and pashas.

Perraivos (1815) based on oral stories he collected proposed that the first attack against Souli by the Ottoman authorities occurred in 1721. Archival sources show that the campaign occurred more likely in 1731-33 and didn't have Souliotes as its specific target. In the early 18th century, the Muslim Cham beys of

The first historical account of anti-Ottoman activity in Souli dates from the Ottoman-Venetian War of 1684–89. In particular in 1685, the Souliotes together with the inhabitants of Himara revolted and overthrew the local Ottoman authorities. This uprising was short-lived due to the reaction of the local Ottoman beys, agas and pashas.

Perraivos (1815) based on oral stories he collected proposed that the first attack against Souli by the Ottoman authorities occurred in 1721. Archival sources show that the campaign occurred more likely in 1731-33 and didn't have Souliotes as its specific target. In the early 18th century, the Muslim Cham beys of Margariti

Margariti ( el, Μαργαρίτι; sq, Margëlliç) is a village and a former municipality in Thesprotia, Epirus, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Igoumenitsa, of which it is a municipal unit. The ...

and the Souliotes promoted Venetian interests in certain areas of Epirus. In this context, an armatolos

The armatoles ( el, αρματολοί, armatoloi; sq, armatolë; rup, armatoli; bs, armatoli), or armatole in singular ( el, αρματολός, armatolos; sq, armatol; rup, armatol; bs, armatola), were Christian irregular soldiers, or mi ...

of Preveza known by the name Triboukis who supported French commercial interests was murdered. At the same time, the beys of Margariti launched a raid campaign as far as south as Acarnania

Acarnania ( el, Ἀκαρνανία) is a region of west-central Greece that lies along the Ionian Sea, west of Aetolia, with the Achelous River for a boundary, and north of the gulf of Calydon, which is the entrance to the Gulf of Corinth. Today i ...

. The Souliotes who also promoted Venetian goals, either jointly or independently of the Cham beys, launched their own pillaging raids. The local Ottoman authorities gathered 10,000 troops under Aslanzade Hadji Mehmet Pasha who attacked the Cham beys and the armatoloi who engaged in pillaging and destroyed Margariti. Souli itself wasn't attacked in this campaign.

The second recorded attack against Souli in oral history occurred in 1754 by Mustafa Pasha of Yanina. This oral story is confirmed in archival sources and has been recorded in a text in the Church of St. Nicholas of Ioannina.

During the transfer of some brigands from Margariti to Yanina the Souliotes attacked the guards and freed them. The text preserved in the Church of St. Nicholas notes that the person who had captured them was a Muslim from Margariti who was collaborating with them as he was the buyer of the stolen goods. This network of brigandage which the Muslim agas and beys of Margariti and the Souliotes had created in the region was the cause of the attack by Mustafa Pasha.

Other attacks in the same era include that Dost Bey, commander of Delvinë (1759) and Mahmoud Aga, governor of Arta (1762). During 1721–1772 the Souliotes managed to repulse a total of six military expeditions. As a result, they expanded their territory at the expense of the various Ottoman lords.

In 1772, Suleyman Tsapari attacked the Souliotes with his army of 9000 men and was defeated. In 1775, Kurt Pasha sent a military expedition to Souli that ultimately failed. During the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74), the inhabitants of Souli, as well as of other communities in Epirus were mobilized for another Greek uprising which became known as Orlov Revolt. In 1785 it was the time of Bekir pasha to lead another unsuccessful attack against them. In March 1789, during the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1787–1792 involved an unsuccessful attempt by the Ottoman Empire to regain lands lost to the Russian Empire in the course of the previous Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774). It took place concomitantly with the Austro ...

the chieftains of Souli: Georgios and Dimitrios Botsaris, Lambros Tzavellas, Nikolaos and Christos Zervas, Lambros Koutsonikas

Lambros Koutsonikas ( el, Λάμπρος Κουτσονίκας, 1799 – 2 June 1879) was a Greek general and fighter of the Greek Revolution of 1821, army officer and amateur historian of the Revolution.

Biography

He was the son of Yiannos, fr ...

, Christos Photomaras and Demos Drakos, agreed with Louitzis Sotiris, a Greek representative of the Russian side, that they were ready to fight

Combat (French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

with 2,200 men against the Muslims of Rumelia

Rumelia ( ota, روم ايلى, Rum İli; tr, Rumeli; el, Ρωμυλία), etymologically "Land of the Romans", at the time meaning Eastern Orthodox Christians and more specifically Christians from the Byzantine rite, was the name of a hi ...

. This was the time when Ali Pasha became the local Ottoman lord of Ioannina.