Socialism in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the socialist movement in the United States spans a variety of tendencies, including

"Seattle's election of Kshama Sawant shows socialism can play in America"

''

Fourierists also attempted to establish a community in

Fourierists also attempted to establish a community in

What do anarchists want from us?

''

American anarchist

The

The

anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, democratic socialists

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management within ...

, Marxists, Marxist–Leninists, Trotskyists

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a re ...

and utopian socialists

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

. It began with utopian communities in the early 19th century such as the Shakers, the activist visionary Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

and intentional communities

An intentional community is a voluntary residential community which is designed to have a high degree of social cohesion and teamwork from the start. The members of an intentional community typically hold a common social, political, religious, ...

inspired by Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

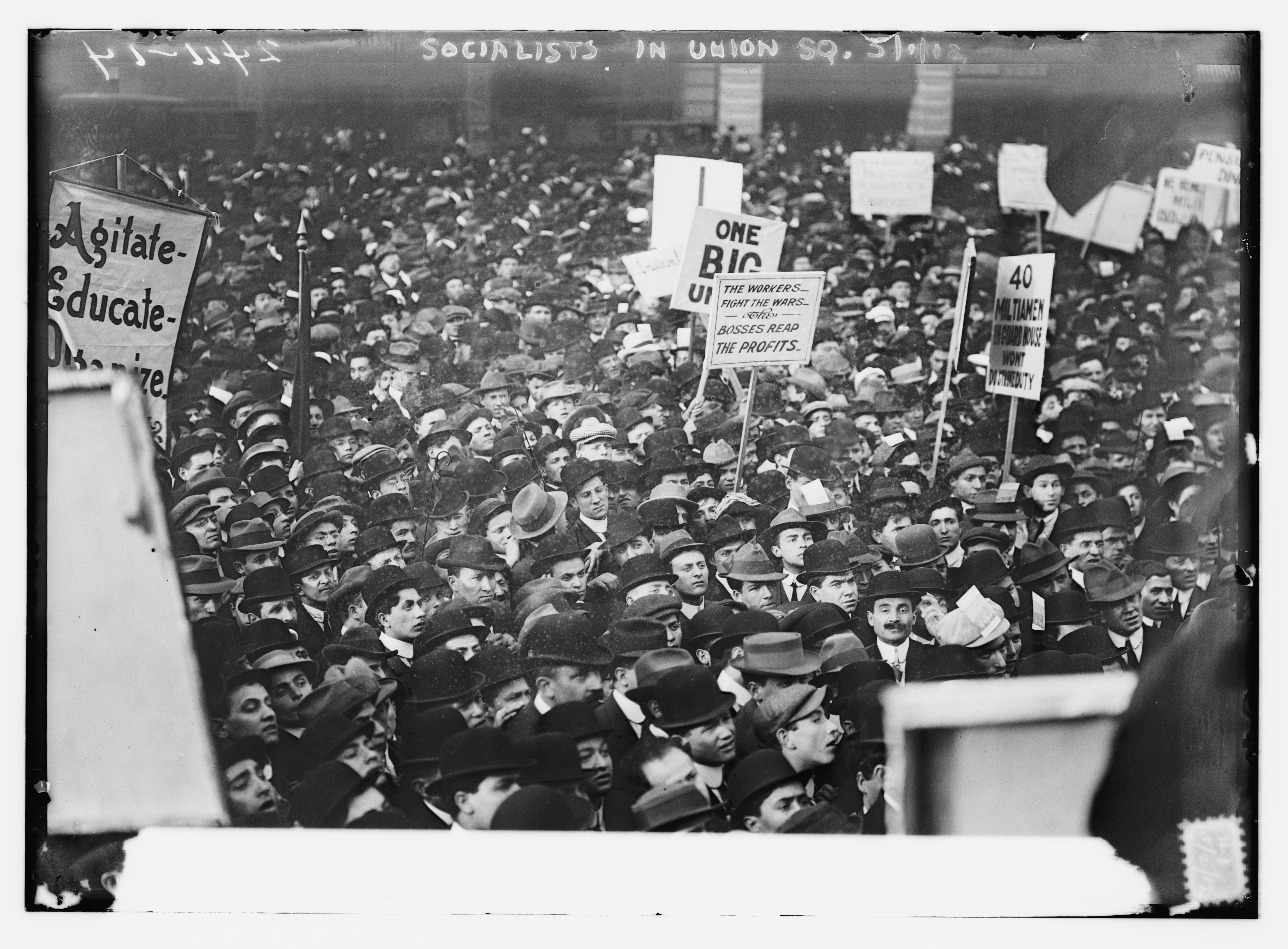

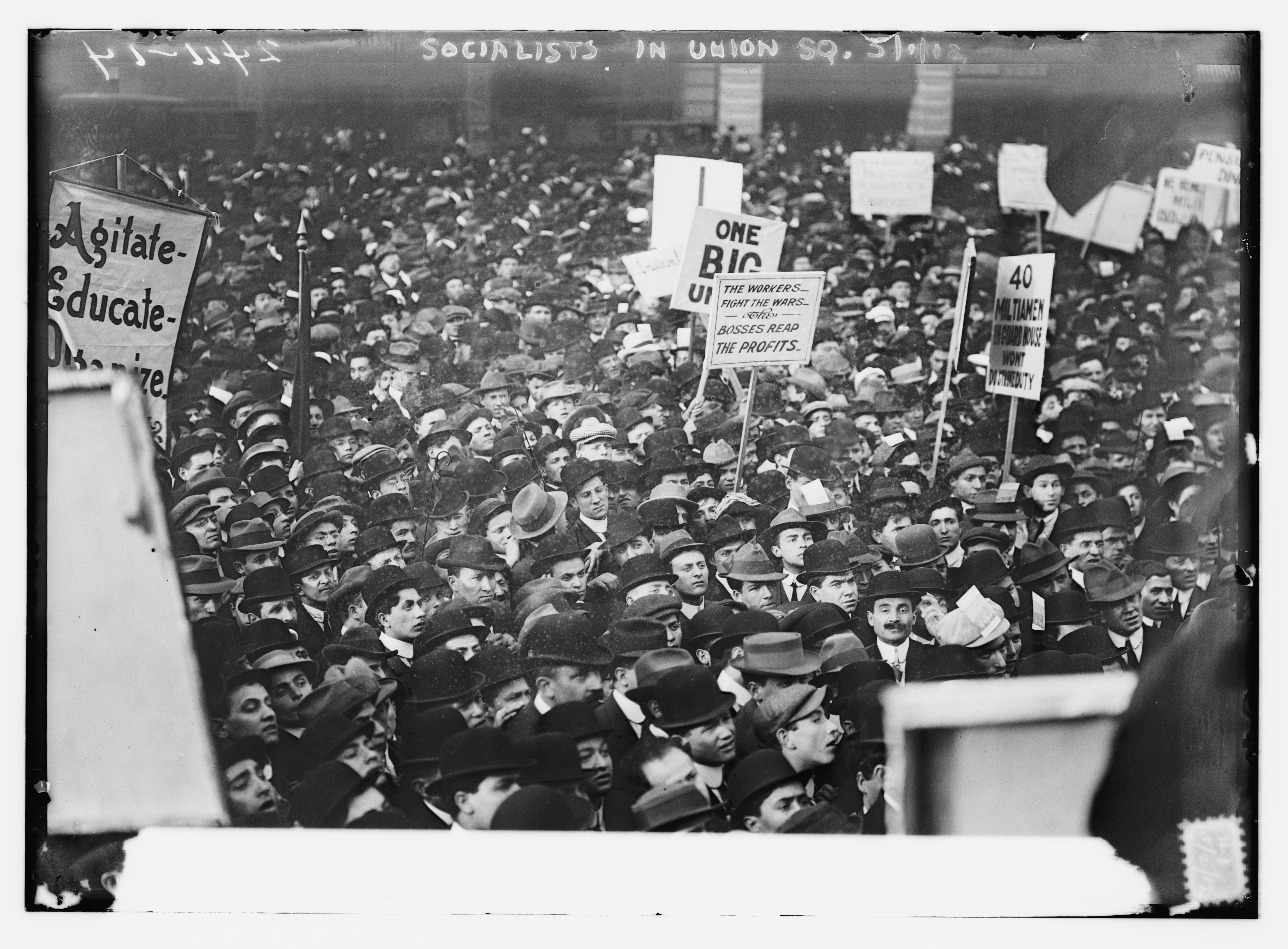

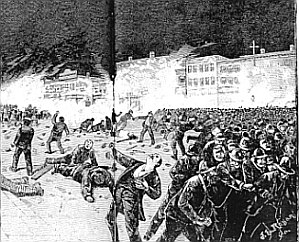

. Labor activists, usually British, German, or Jewish immigrants, founded the Socialist Labor Party of America in 1877. The Socialist Party of America was established in 1901. By that time, anarchism also rose to prominence around the country. Socialists of different tendencies were involved in early American labor organizations and struggles. These reached a high point in the Haymarket massacre

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square in ...

in Chicago, which founded the International Workers' Day as the main labour holiday around the world, Labor Day and making the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

a worldwide objective by workers organizations and socialist parties worldwide.

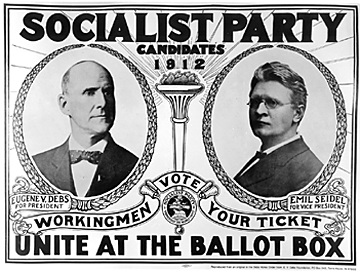

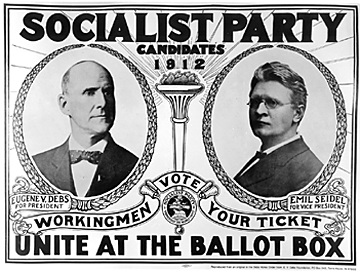

Under Socialist Party of America presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate of the Soc ...

, socialist opposition to World War I was widespread, leading to the governmental repression collectively known as the First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the R ...

. The Socialist Party declined in the 1920s, but the party nonetheless often ran Norman Thomas

Norman Mattoon Thomas (November 20, 1884 – December 19, 1968) was an American Presbyterian minister who achieved fame as a socialist, pacifist, and six-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America.

Early years

Thomas was the ...

for president. In the 1930s, the Communist Party USA took importance in labor and racial struggles while it suffered a split which converged in the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party. In the 1950s, socialism was affected by McCarthyism and in the 1960s it was revived by the general radicalization brought by the New Left and other social struggles and revolts. In the 1960s, Michael Harrington

Edward Michael Harrington Jr. (February 24, 1928 – July 31, 1989) was an American democratic socialist. As a writer, he was perhaps best known as the author of '' The Other America''. Harrington was also a political activist, theorist, profess ...

and other socialists were called to assist the Kennedy administration

John F. Kennedy's tenure as the 35th president of the United States, began with his inauguration on January 20, 1961, and ended with his assassination on November 22, 1963. A Democrat from Massachusetts, he took office following the 1960 ...

and then the Johnson administration's War on Poverty

The war on poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a national ...

and Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

while socialists also played important roles in the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

.Anderson, Jervis (1973) 986

Year 986 ( CMLXXXVI) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* August 17 – Battle of the Gates of Trajan: Emperor Basil II leads a Byz ...

''A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait''. University of California Press. .

* Anderson, Jervis (1997). ''Bayard Rustin: Troubles I've Seen''. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

* Branch, Taylor (1989). ''Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63''. New York: Touchstone.

* D'Emilio, John (2003). ''Lost Prophet: Bayard Rustin and the Quest for Peace and Justice in America''. New York: The Free Press.

* D'Emilio, John (2004). ''Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Unlike in Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, a major socialist party has never materialized in the United States and the socialist movement in the United States was relatively weak in comparison. In the United States, socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

can be stigmatized

Social stigma is the disapproval of, or discrimination against, an individual or group based on perceived characteristics that serve to distinguish them from other members of a society. Social stigmas are commonly related to culture, gender, rac ...

because it is commonly associated with authoritarian socialism, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and other authoritarian Marxist-Leninist regime

In politics, a regime (also "régime") is the form of government or the set of rules, cultural or social norms, etc. that regulate the operation of a government or institution and its interactions with society. According to Yale professor Juan Jo ...

s. Writing for ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Eco ...

'', Samuel Jackson argued that ''socialism'' has been used as a pejorative term, without any clear definition, by conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

and right-libertarians

Right-libertarianism,Rothbard, Murray (1 March 1971)"The Left and Right Within Libertarianism" ''WIN: Peace and Freedom Through Nonviolent Action''. 7 (4): 6–10. Retrieved 14 January 2020.Goodway, David (2006). '' Anarchist Seeds Beneath the ...

to taint liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and progressive policies, proposals and public figures. The term ''socialization

In sociology, socialization or socialisation (see spelling differences) is the process of internalizing the norms and ideologies of society. Socialization encompasses both learning and teaching and is thus "the means by which social and cul ...

'' has been mistakenly used to refer to any state or government-operated industry or service (the proper term for such being either ''municipalization

Municipalization is the transfer of private entities, assets, service providers, or corporations to public ownership by a municipality, including (but not limited to) a city, county, or public utility district ownership. The transfer may be from pr ...

'' or '' nationalization''). The term has also been used to mean any tax-funded programs, whether privately run or government run. The term ''socialism'' has been used to argue against economic interventionism, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is one of two agencies that supply deposit insurance to depositors in American depository institutions, the other being the National Credit Union Administration, which regulates and insures cr ...

, Medicare, the New Deal, Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

and universal single-payer health care, among others.

Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee ...

has had several socialist mayors such as Emil Seidel

Emil Seidel (December 13, 1864 – June 24, 1947) was a prominent German-American politician. Seidel was the mayor of Milwaukee from 1910 to 1912. The first Socialist mayor of a major city in the United States, Seidel became the Vice Presidential ...

, Daniel Hoan

Daniel Webster Hoan (March 12, 1881 – June 11, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 32nd Mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin from 1916 to 1940. A lawyer who had served as Milwaukee City Attorney from 1910 to 1916, Hoan was a promin ...

and Frank Zeidler

Frank Paul Zeidler (September 20, 1912 – July 7, 2006) was an American socialist politician and mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, serving three terms from April 20, 1948, to April 18, 1960. Zeidler, a member of the Socialist Party of America, i ...

whilst Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs won nearly one million votes in the 1920 presidential election.Paul, Ari (November 19, 2013)"Seattle's election of Kshama Sawant shows socialism can play in America"

''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

''. Retrieved February 9, 2014. Self-declared democratic socialist Bernie Sanders won 13 million votes in the 2016 Democratic Party presidential primary

Presidential primaries and caucuses were organized by the Democratic Party to select the 4,051 delegates to the 2016 Democratic National Convention held July 25–28 and determine the nominee for president in the 2016 United States presidential e ...

, gaining considerable popular support, particularly among the younger generation and the working class. One 2021 poll reported 41% of American adults had a positive view of socialism and 57% had a positive view of capitalism.

19th century

Utopian socialism and communities

Utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

was the first American socialist movement. Utopians attempted to develop model socialist societies to demonstrate the virtues of their brand of beliefs. Most utopian socialist ideas originated in Europe, but the United States was most often the site for the experiments themselves. Many utopian experiments occurred in the 19th century as part of this movement, including Brook Farm

Brook Farm, also called the Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and EducationFelton, 124 or the Brook Farm Association for Industry and Education,Rose, 140 was a utopian experiment in communal living in the United States in the 1840s. It was fo ...

, the New Harmony, the Shakers, the Amana Colonies

The Amana Colonies are seven villages on located in Iowa County in east-central Iowa, United States: Amana (or Main Amana, German: ''Haupt-Amana''), East Amana, High Amana, Middle Amana, South Amana, West Amana, and Homestead. The villages ...

, the Oneida Community

The Oneida Community was a perfectionist religious communal society founded by John Humphrey Noyes and his followers in 1848 near Oneida, New York. The community believed that Jesus had already returned in AD 70, making it possible for the ...

, The Icarians, Bishop Hill Commune, Aurora, Oregon

Aurora is a city in Marion County, Oregon, United States. Before being incorporated as a city, it was the location of the Aurora Colony, a religious commune founded in 1856 by William Keil and John E. Schmit. William named the settlement after h ...

and Bethel, Missouri

Bethel is a village in Shelby County, Missouri, Shelby County, Missouri, United States. The population was 135 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

History

Bethel was founded as a Bible utopian colony in 1844 by Dr William Keil (1811– ...

.

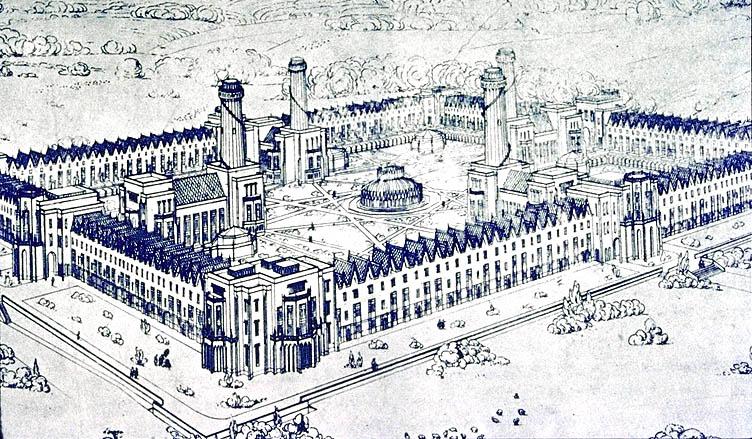

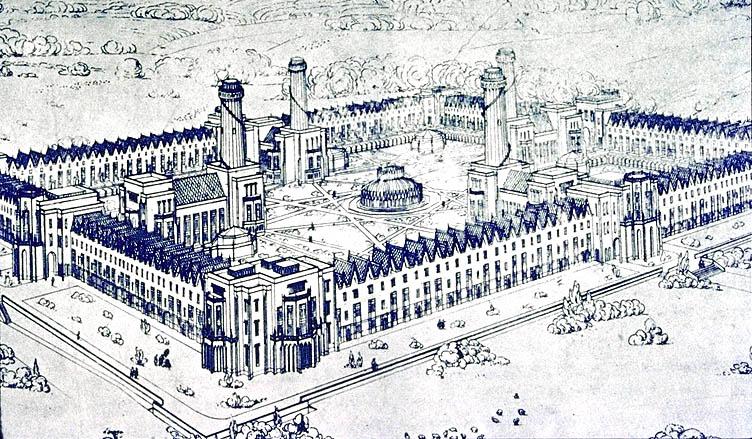

Robert Owen, a wealthy Welsh industrialist, turned to social reform and socialism and in 1825 founded a communitarian colony called New Harmony in southwestern

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

Indiana. The group fell apart in 1829, mostly due to conflict between utopian ideologues and non-ideological pioneers. In 1841, transcendentalist utopians founded Brook Farm

Brook Farm, also called the Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and EducationFelton, 124 or the Brook Farm Association for Industry and Education,Rose, 140 was a utopian experiment in communal living in the United States in the 1840s. It was fo ...

, a community based on Frenchman Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

's brand of socialism. Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

was a member of this short-lived community, and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

had declined invitations to join. The group had trouble reaching financial stability and many members left as their leader George Ripley George Ripley may refer to:

* George Ripley (alchemist) (died 1490), English author and alchemist

*George Ripley (transcendentalist)

George Ripley (October 3, 1802 – July 4, 1880) was an American social reformer, Unitarian minister, and journ ...

turned more and more to Fourier's doctrine. All hope for its survival was lost when the expensive, Fourier-inspired main building burnt down while under construction. The community dissolved in 1847.

Fourierists also attempted to establish a community in

Fourierists also attempted to establish a community in Monmouth County, New Jersey

Monmouth County () is a county located on the coast of central New Jersey. The county is part of the New York metropolitan area and is situated along the northern half of the Jersey Shore. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the county's population wa ...

. The North American Phalanx

The North American Phalanx was a secular utopian socialist commune located in Colts Neck Township, Monmouth County, New Jersey. The community was the longest-lived of about 30 Fourierist Associations in the United States which emerged during a b ...

community built a Phalanstère—Fourier's concept of a communal-living structure—out of two farmhouses and an addition that linked the two. The community lasted from 1844 to 1856, when a fire destroyed the community's flour and saw-mills and several workshops. The community had already begun to decline after an ideological schism in 1853. French socialist Étienne Cabet

Étienne Cabet (; January 1, 1788 – November 9, 1856) was a French philosopher and utopian socialist who founded the Icarian movement. Cabet became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to artisans who were bei ...

, frustrated in Europe, sought to use his Icarian movement to replace capitalist production with workers cooperatives. He became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to English artisans were being undercut by factories. In the 1840s, Cabet led groups of emigrants to found utopian communities in Texas and Illinois. However, his work was undercut by his many feuds with his own followers.

Utopian socialism reached the national level fictionally in Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

's 1888 novel ''Looking Backward

''Looking Backward: 2000–1887'' is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

The book was translated into several languages, and in short o ...

'', a utopian depiction of a socialist United States in the year 2000. The book sold millions of copies and became one of the best-selling American books of the nineteenth century. By one estimation, only ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U ...

'' surpassed it in sales. The book sparked a following of Bellamy Clubs and influenced socialist and labor leaders, including Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor "Gene" Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American socialist, political activist, trade unionist, one of the founding members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and five times the candidate of the Soc ...

. Likewise, Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in sever ...

's masterpiece ''The Jungle

''The Jungle'' is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair. Sinclair's primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States. However, most readers we ...

'' was first published in the socialist newspaper '' Appeal to Reason'', criticizing capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

as being oppressive and exploitative to meatpacking workers in the industrial food system. The book is still widely referred to today as one of the most influential works of literature in modern history.

Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

is widely regarded as the first American anarchistPalmer, Brian (2010-12-29What do anarchists want from us?

''

Slate.com

''Slate'' is an online magazine that covers current affairs, politics, and culture in the United States. It was created in 1996 by former '' New Republic'' editor Michael Kinsley, initially under the ownership of Microsoft as part of MSN. In 2 ...

'' and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, ''The Peaceful Revolutionist'', was the first anarchist periodical published.William Bailie, ''Josiah Warren: The First American Anarchist — A Sociological Study'', Boston: Small, Maynard & Co., 1906, p. 20. Warren, a follower of Robert Owen, joined Owen's community at New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana. It lies north of Mount Vernon, the county seat, and is part of the Evansville metropolitan area. The town's population was 789 at the 2010 census. ...

. He coined the phrase "Cost the limit of price

"Cost the limit of price" was a maxim coined by Josiah Warren, indicating a (prescriptive) version of the labor theory of value. Warren maintained that the just compensation for labor (or for its product) could only be an equivalent amount of l ...

," with "cost" here referring not to monetary price paid but the labor one exerted to produce an item. Therefore, " proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce." He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental "labor for labor store" called the Cincinnati Time Store

The Cincinnati Time Store (1827-1830) was the first in a series of retail stores created by American individualist anarchist Josiah Warren to test his economic labor theory of value. The experimental store operated from May 18, 1827 until May 18 ...

where trade was facilitated by notes backed by a promise to perform labor. The store proved successful and operated for three years, after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism. These included "Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island societ ...

" and " Modern Times." Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews' ''The Science of Society'', published in 1852, was the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories. For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster: "It is apparent ... that Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Soci ...

ian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

and Stephen Pearl Andrews ... William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form."Eunice Minette Schuster, ''Native American Anarchism: A Study of Left-Wing American Individualism''.American anarchist

Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

wrote in ''Individual Liberty'':

Early Marxism

German Marxist immigrants who arrived in the United States after the1848 revolutions

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europe ...

in Europe brought socialist ideas with them.Draper, Theodore. The roots of American Communism. New York: Viking Press, 1957. pp. 11–12. Joseph Weydemeyer

Joseph Arnold Weydemeyer (February 2, 1818, Münster – August 26, 1866, St. Louis, Missouri) was a military officer in the Kingdom of Prussia and the United States as well as a journalist, politician and Marxist revolutionary.

At first a supp ...

, a German colleague of Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

who sought refuge in New York in 1851 following the 1848 revolutions, established the first Marxist journal in the United States, ''Die Revolution'', but It folded after two issues. In 1852, he established the ''Proletarierbund'', which would become the American Workers' League, the first Marxist organization in the United States, but it too proved short-lived, having failed to attract a native English-speaking membership. In 1866, William H. Sylvis

William H. Sylvis (1828–1869) was a pioneer American trade union leader. Sylvis is best remembered as a founder of the Iron Molders' International Union. He also was a founder of the National Labor Union. It was one of the first American union ...

formed the National Labor Union

The National Labor Union (NLU) is the first national labor federation in the United States. Founded in 1866 and dissolved in 1873, it paved the way for other organizations, such as the Knights of Labor and the AFL ( American Federation of Labor ...

(NLU). Frederich Albert Sorge, a German who had found refuge in New York following the 1848 revolutions, took Local No. 5 of the NLU into the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

as Section One in the United States. By 1872, there were 22 sections, which held a convention in New York. The General Council of the International moved to New York with Sorge as General Secretary, but following internal conflict it dissolved in 1876.Coleman, pp. 15–17.

A larger wave of German immigrants followed in the 1870s and 1880s, including social democratic followers of Ferdinand Lasalle. Lasalle regarded state aid through political action as the road to revolution and opposed trade unionism, which he saw as futile, believing that according to the iron law of wages

The iron law of wages is a proposed law of economics that asserts that real wages always tend, in the long run, toward the minimum wage necessary to sustain the life of the worker. The theory was first named by Ferdinand Lassalle in the mid-nine ...

employers would only pay subsistence wages. The Lasalleans formed the Social Democratic Party of North America in 1874 and both Marxists and Lasalleans formed the Workingmen's Party of the United States

The Workingmen's Party of the United States (WPUS), established in 1876, was one of the first Marxist-influenced political parties in the United States. It is remembered as the forerunner of the Socialist Labor Party of America.

Organizational h ...

in 1876. When the Lasalleans gained control in 1877, they changed the name to the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP). However, many socialists abandoned political action altogether and moved to trade unionism. Two former socialists, Adolph Strasser and Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

, formed the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1886.

The

The Socialist Labor Party

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP)"The name of this organization shall be Socialist Labor Party". Art. I, Sec. 1 of thadopted at the Eleventh National Convention (New York, July 1904; amended at the National Conventions 1908, 1912, 1916, 1920, 1924 ...

(SLP) was officially founded in 1876 at a convention in Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Jersey and the seat of Essex County and the second largest city within the New York metropolitan area.Marxist ideals with them to North America. So strong was the heritage that the official party language was German for the first three years. In its nascent years, the party encompassed a broad range of various socialist philosophies, with differing concepts of how to achieve their goals. Nevertheless, there was a

The Socialist Party formed strong alliances with a number of labor organizations because of their similar goals. In an attempt to rebel against the abuses of corporations, workers had found a solution—or so they thought—in a technique of collective bargaining. By banding together into "unions" and by refusing to work, or "striking," workers would halt production at a plant or in a mine, forcing

The Socialist Party formed strong alliances with a number of labor organizations because of their similar goals. In an attempt to rebel against the abuses of corporations, workers had found a solution—or so they thought—in a technique of collective bargaining. By banding together into "unions" and by refusing to work, or "striking," workers would halt production at a plant or in a mine, forcing  In May 1886, the Knights of Labor were demonstrating in the

In May 1886, the Knights of Labor were demonstrating in the

The American anarchist

The American anarchist

at the

Victor L. Berger ran for Congress and lost in

Victor L. Berger ran for Congress and lost in  On January 7, 1920, at the first session of the New York State Assembly, Assembly Speaker Thaddeus C. Sweet attacked the Assembly's five Socialist members, declaring they had been "elected on a platform that is absolutely inimical to the best interests of the state of New York and the United States." The Socialist Party, Sweet said, was "not truly a political party," but was rather "a membership organization admitting within its ranks aliens, enemy aliens, and minors." It had supported the revolutionaries in

On January 7, 1920, at the first session of the New York State Assembly, Assembly Speaker Thaddeus C. Sweet attacked the Assembly's five Socialist members, declaring they had been "elected on a platform that is absolutely inimical to the best interests of the state of New York and the United States." The Socialist Party, Sweet said, was "not truly a political party," but was rather "a membership organization admitting within its ranks aliens, enemy aliens, and minors." It had supported the revolutionaries in

The Seventh Congress of the Comintern made a change in line official in 1935, when it declared the need for a

The Seventh Congress of the Comintern made a change in line official in 1935, when it declared the need for a

'' Monthly Review'', established in 1949, is an independent

'' Monthly Review'', established in 1949, is an independent

''

/ref>

John Cage at Seventy: An Interview

by Stephen Montague. ''American Music'', Summer 1985. Ubu.com. Accessed May 24, 2007. Goodman was an American sociologist, poet, writer, anarchist and

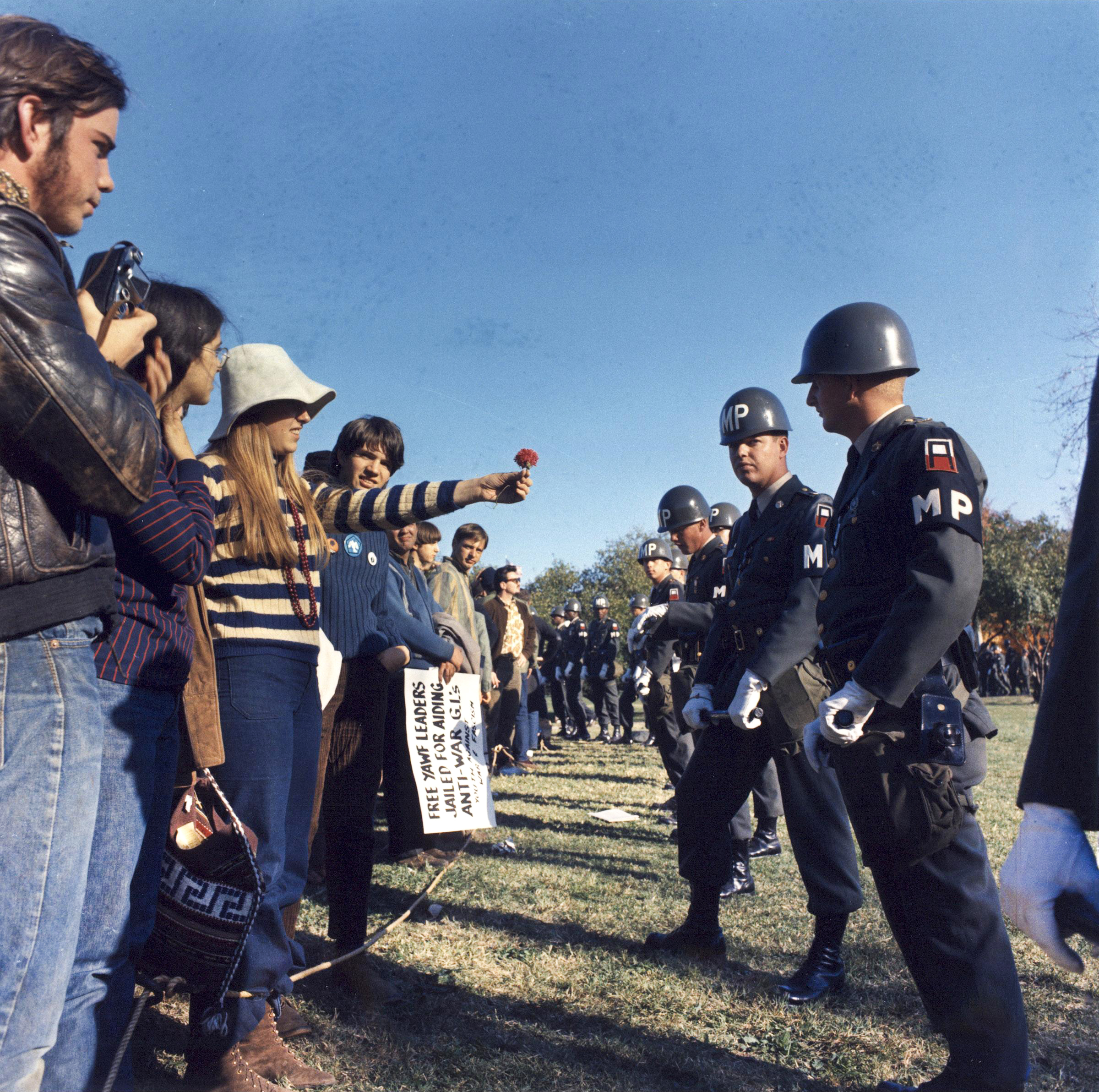

The term New Left was popularised in the United States in an open letter written in 1960 by sociologist

The term New Left was popularised in the United States in an open letter written in 1960 by sociologist

''The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage''

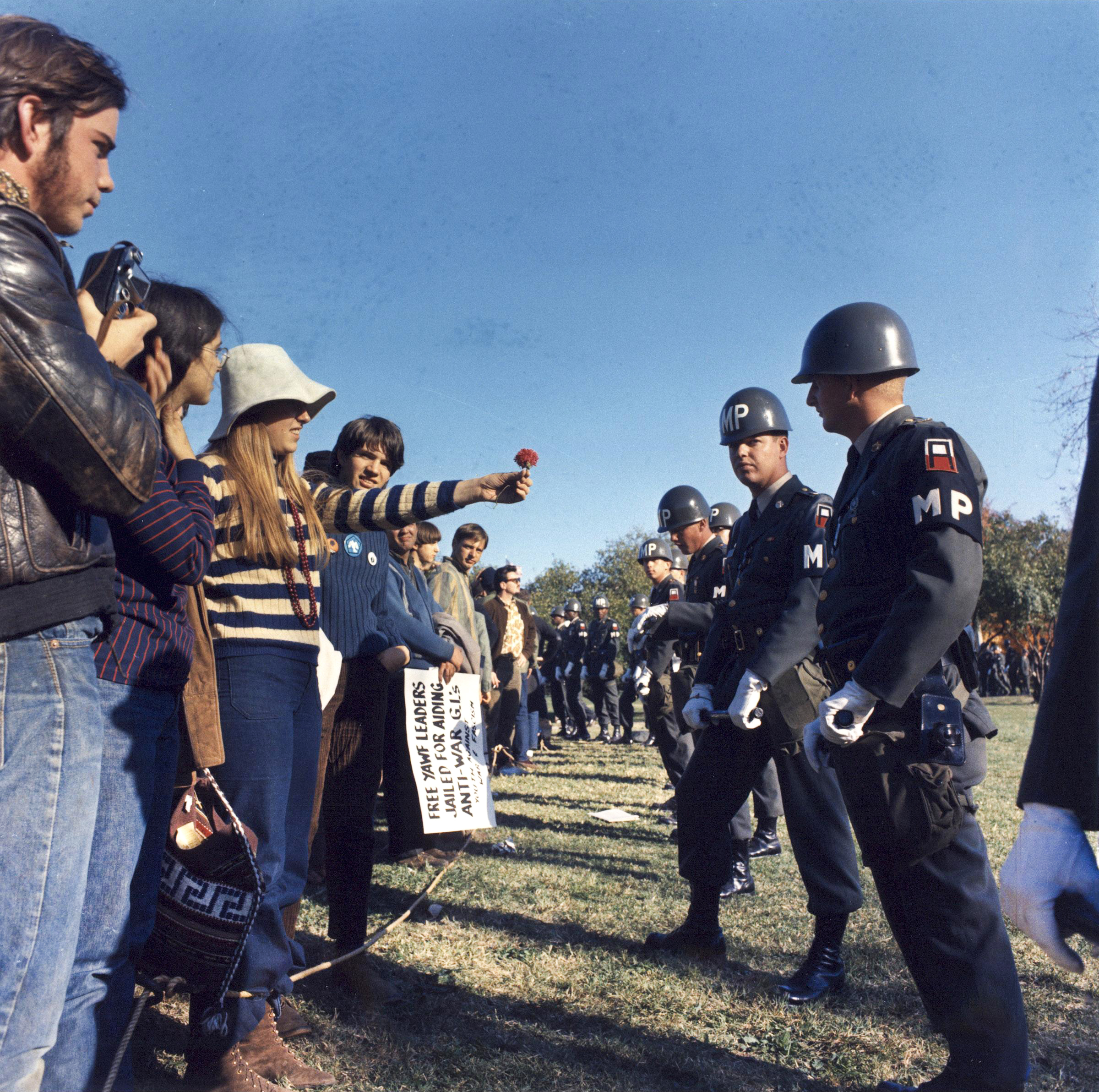

(1987), p. 191. ISBN. Afterwards, In the 1960s, the hippie movement influenced a renewed interest in anarchism, and some anarchist and other left-wing groups developed out of the New Left and anarchists actively participated in the late sixties students and workers revolts. Anarchists began using direct action, organizing through

In the 1960s, the hippie movement influenced a renewed interest in anarchism, and some anarchist and other left-wing groups developed out of the New Left and anarchists actively participated in the late sixties students and workers revolts. Anarchists began using direct action, organizing through

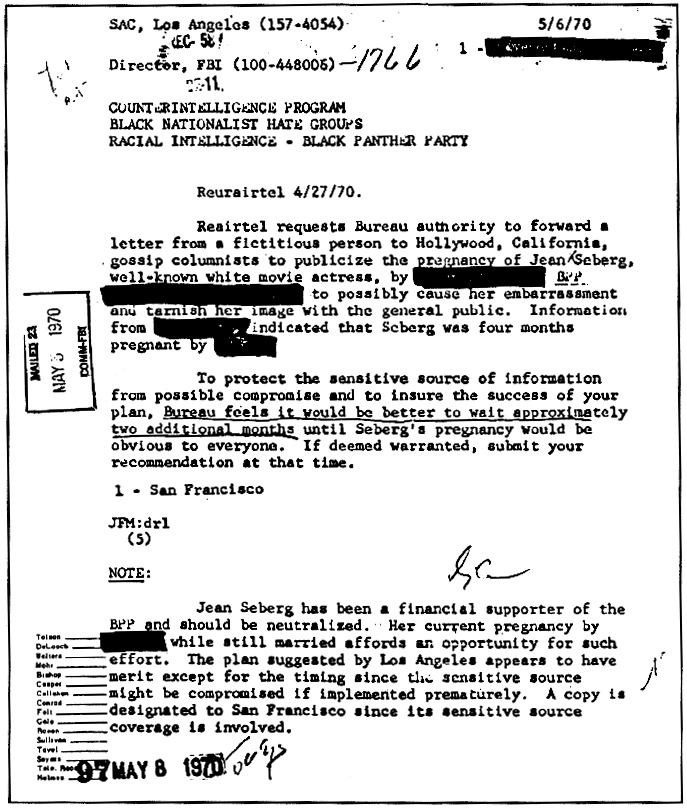

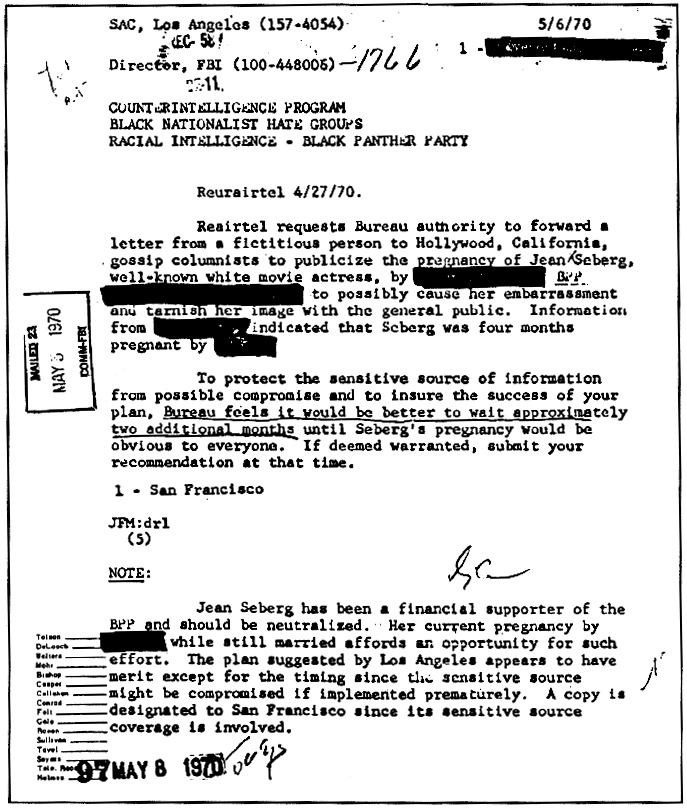

''Los Angeles Times'', March 8, 2006. FBI records show that 85% of COINTELPRO resources targeted groups and individuals that the FBI deemed "subversive," including communist and In 1972, the Socialist Party voted to rename itself as Social Democrats, USA (SDUSA) by a vote of 73 to 34 at its December Convention. Its National Chairmen were Bayard Rustin, a peace and civil rights leader; and Charles S. Zimmerman, an officer of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). In 1973, Michael Harrington resigned from SDUSA and founded the

In 1972, the Socialist Party voted to rename itself as Social Democrats, USA (SDUSA) by a vote of 73 to 34 at its December Convention. Its National Chairmen were Bayard Rustin, a peace and civil rights leader; and Charles S. Zimmerman, an officer of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). In 1973, Michael Harrington resigned from SDUSA and founded the

"Quieter Lives for 60's Militants, but Intensity of Beliefs Hasn't Faded"

article ''

The only American member organization of the worldwide Socialist International was the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) until mid-2017, when the latter voted to disaffiliate from that organization for its perceived acceptance of Neoliberalism, neoliberal economic policies. In 2008, the DSA supported Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama in his race against

The only American member organization of the worldwide Socialist International was the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) until mid-2017, when the latter voted to disaffiliate from that organization for its perceived acceptance of Neoliberalism, neoliberal economic policies. In 2008, the DSA supported Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama in his race against  The Occupy movement in the United States, Occupy movement ultimately convinced United States Senator Bernie Sanders to run for president in 2016 as a Democratic socialism, democratic socialist. In his bid, "Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders attracted some of the largest crowds of the 2016 presidential campaign... 11,000 in Phoenix, 25,000 in Los Angeles, and 28,000 in Portland, Oregon. Sanders, a democratic socialist who for three decades has won office as an Independent, ran in the Democratic Party primaries. While he does not advocate the original goal of socialism—that 'a nation’s resources and major industries should be owned and operated by the government on behalf of all the people, not by individuals and private companies for their own profit,'... Sanders has put “socialism” back in American political discourse." Sanders is the leading figure in the Bernie Sanders Guide to Political Revolution, "political revolution," by which he means an insurgent movement of voters and activists, not a violent storming of the barricades—can make the U.S. work for the majority of its citizens. In addition, his 2020 run for President of the United States saw even larger crowds, topping 26,000 attendees. Senator Sanders also received the most votes in the 2020 Iowa Democratic presidential caucuses, 2020 Democratic Iowa and 2020 Nevada Democratic presidential caucuses, Nevada Caucuses, 2020 New Hampshire Democratic presidential primary, New Hampshire Primary, and the 2020 California Democratic presidential primary, California primary, the most populous state in the Union.

The 21st century has seen an increase in the participation of socialist and left-wing organizing, precipitated by the Occupy movement and Bernie Sanders' 2016 and 2020 presidential runs. This has resulted in an explosive growth of the Democratic Socialists of America, Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) where by "December 2018, DSA had some 55,000 members in 166 chapters and 57 high school and college groups, making it the largest socialist organization in the United States since the heyday of the Communist Party in the 1930s and 1940s." In an interview by The New Labor Forum, a DSA member testifies "I have basically been a lifelong liberal who has very slowly radicalized and was kind of catapulted into radicalization by the Bernie primary campaign. I really didn't know about the term democratic socialism until Bernie started using it." These organizations like the DSA are leading a movement that is giving voice to left-wing positions, emphasizing issues such as affordable housing, universal health care, opposing public subsidies for corporations, seeking the creation of government-owned banks, environmental justice, and free college for all. There have been an increase of democratic socialists elected to Congress, most notably a group of four congresswomen known as "The Squad." In a 2011 survey, more people under the age of 30 had a favorable view of socialism than of capitalism.

Sanders served as the at-large representative for the state of Vermont before being elected to the Senate in 2006. In a 2013 interview with ''Politico'', radio host Thom Hartmann, whose nationally syndicated radio show draws 2.75 million listeners a week, affirmed his position as a democratic socialist. Sanders has been credited with reviving the American socialist movement by bringing it into the mainstream public view for the 2016 United States presidential election, 2016 presidential election. With the election of Donald Trump, the DSA soared to 25,000 dues-paying members and SA at least 30 percent. Some DSA members had emerged in local races in states like Illinois and Georgia. Subscribers to the socialist quarterly magazine ''Jacobin (magazine), Jacobin'' doubled in four months following the election to 30,000.

According to a November 2017 YouGov poll, a majority of Americans aged 21 to 29 prefer socialism to capitalism and believe that the American economic system is working against them. In the same month, 15 members of the DSA were elected to various local and state governmental positions around the country in the 2017 United States elections, 2017 elections. Tracing its lineage from the New Left to

The Occupy movement in the United States, Occupy movement ultimately convinced United States Senator Bernie Sanders to run for president in 2016 as a Democratic socialism, democratic socialist. In his bid, "Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders attracted some of the largest crowds of the 2016 presidential campaign... 11,000 in Phoenix, 25,000 in Los Angeles, and 28,000 in Portland, Oregon. Sanders, a democratic socialist who for three decades has won office as an Independent, ran in the Democratic Party primaries. While he does not advocate the original goal of socialism—that 'a nation’s resources and major industries should be owned and operated by the government on behalf of all the people, not by individuals and private companies for their own profit,'... Sanders has put “socialism” back in American political discourse." Sanders is the leading figure in the Bernie Sanders Guide to Political Revolution, "political revolution," by which he means an insurgent movement of voters and activists, not a violent storming of the barricades—can make the U.S. work for the majority of its citizens. In addition, his 2020 run for President of the United States saw even larger crowds, topping 26,000 attendees. Senator Sanders also received the most votes in the 2020 Iowa Democratic presidential caucuses, 2020 Democratic Iowa and 2020 Nevada Democratic presidential caucuses, Nevada Caucuses, 2020 New Hampshire Democratic presidential primary, New Hampshire Primary, and the 2020 California Democratic presidential primary, California primary, the most populous state in the Union.

The 21st century has seen an increase in the participation of socialist and left-wing organizing, precipitated by the Occupy movement and Bernie Sanders' 2016 and 2020 presidential runs. This has resulted in an explosive growth of the Democratic Socialists of America, Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) where by "December 2018, DSA had some 55,000 members in 166 chapters and 57 high school and college groups, making it the largest socialist organization in the United States since the heyday of the Communist Party in the 1930s and 1940s." In an interview by The New Labor Forum, a DSA member testifies "I have basically been a lifelong liberal who has very slowly radicalized and was kind of catapulted into radicalization by the Bernie primary campaign. I really didn't know about the term democratic socialism until Bernie started using it." These organizations like the DSA are leading a movement that is giving voice to left-wing positions, emphasizing issues such as affordable housing, universal health care, opposing public subsidies for corporations, seeking the creation of government-owned banks, environmental justice, and free college for all. There have been an increase of democratic socialists elected to Congress, most notably a group of four congresswomen known as "The Squad." In a 2011 survey, more people under the age of 30 had a favorable view of socialism than of capitalism.

Sanders served as the at-large representative for the state of Vermont before being elected to the Senate in 2006. In a 2013 interview with ''Politico'', radio host Thom Hartmann, whose nationally syndicated radio show draws 2.75 million listeners a week, affirmed his position as a democratic socialist. Sanders has been credited with reviving the American socialist movement by bringing it into the mainstream public view for the 2016 United States presidential election, 2016 presidential election. With the election of Donald Trump, the DSA soared to 25,000 dues-paying members and SA at least 30 percent. Some DSA members had emerged in local races in states like Illinois and Georgia. Subscribers to the socialist quarterly magazine ''Jacobin (magazine), Jacobin'' doubled in four months following the election to 30,000.

According to a November 2017 YouGov poll, a majority of Americans aged 21 to 29 prefer socialism to capitalism and believe that the American economic system is working against them. In the same month, 15 members of the DSA were elected to various local and state governmental positions around the country in the 2017 United States elections, 2017 elections. Tracing its lineage from the New Left to

The SLP of America: a premature obituary?"

''Socialist Standard''. Retrieved May 11, 2010. * Alexander, Robert J. ''International Trotskyism, 1929–1985: a documented analysis of the movement''. United States of America: Duke University Press, 1991. . * Amster, Randall. ''Contemporary Anarchist Studies: an introductory anthology of anarchy in the academy''. Oxford, UK: Taylor & Francis, 2009. . * Bérubé, Michael. ''The Left at War''. New York: New York University Press, 2009. . * Mari Jo Buhle, Buhle, Mari Jo; Paul Buhle, Buhle, Paul and Dan Georgakas, Georgakas, Dan. ''Encyclopedia of the American Left'' (second edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. . * Buhle, Paul. ''Marxism in the United States: Remapping the History of the American Left.'' Verso; revised edition (April 17, 1991). * Busky, Donald F. ''Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey''. Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2000. . * Coleman, Stephen. ''Daniel De Leon''. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1990. . * Draper, Theodore. ''The Roots of American Communism''. New York: Viking Press, 1957. . * Dubofsky, Melvyn. (1994). ''The State and Labor in Modern America.'' University of North Carolina Press. * George, John and Wilcox, Laird. ''American Extremists: Militias, Supremacists, Klansmen, Communists & Others''. Amherst: Prometheus Books, 1996. . * Graeber, David. "The rebirth of anarchism in North America, 1957–2007" in ''Contemporary history online'', No. 21, (Winter, 2010). * Isserman, Maurice. ''The Other American: the life of Michael Harrington''. New York: Public Affairs, 2000. . * Klehr, Harvey. ''Far Left of Center: The American Radical Left Today''. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1988. . * Lingeman, Richard. ''The Nation Guide to the Nation''. New York: Vintage Books, 2009. . * Lipset, Seymour Martin and Marks, Gary. ''It Didn't Happen Here: Why Socialism Failed in the United States''. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 2001. . * Nichols, John. ''The S Word: A Short History of an American Tradition ... Socialism''. Verso (March 21, 2011). * Nordhoff, Charles. (1875). ''THE COMMUNISTIC SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES: From Personal Visit and Observation.'' Harper & Brothers (reprinted 1966), Dover Publications, Inc. . LICN 66–11429. * Reuters

"U.S. protests shrink while antiwar sentiment grows"

October 3, 2007, 12:30:17 GMT. Retrieved September 20, 2010. * * Sherman, Amy

"Demonstrators to gather in Fort Lauderdale to rail against oil giant BP"

''Miami Herald''. May 12, 2010. Retrieved from SunSentinel.com September 22, 2010. * Stedman, Susan W. and Stedman Jr. Murray Salisbury. ''Discontent at the polls: a study of farmer and labor parties, 1827–1948''. New York: Columbia University Press. 1950. * Tindall, George Brown and Shi, David E. (1984). ''America: a Narrative History'' (sixth edition, in two volumes). W. W. Norton and Company. * Woodcock, George, ''Anarchism: a history of libertarian ideas and movements''. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004. . * Zinn, Howard (1980). ''A People's History of the United States.'' Harper & Row. .

Harper Perennial, 2014. . * Michael Harrington, Harrington, Michael

''Socialism: Past and Future''

Arcade Publishing, 2011. . * Hillquit, Morris

''History of Socialism in the United States''

(1906). * Lane Kenworthy, Kenworthy, Lane.

Social Democratic America

'. Oxford University Press. 2014. . * John Nichols (journalist), Nichols, John

''The S Word: A Short History of an American Tradition... Socialism''

Verso, 2011. . * Noyes, John Humphrey

''History of American Socialisms''

(1870). * Zinn, Howard. ''A People's History of the United States''. Harper Perennial (1980; updated version, 2010).

Early Marxists in North America (Marxist Internet Archive)

Eugene V. Debs: Trade Unionist, Socialist, Revolutionary 1855-1926

by Bernard Sanders (1979).

"Is Obama a socialist? What does the evidence say?"

''The Christian Science Monitor'', July 1, 2010.

The "O" in Socialism

by Betsy Reed, ''The Nation'', June 12, 2009.

"Why I Am a Socialist"

by Chris Hedges, ''Truthdig,'' December 29, 2008.

Ari Paul, "Seattle's election of Kshama Sawant shows socialism can play in America"

''The Guardian'', November 19, 2013.

Andrew Wilkes, ''The Huffington Post,'' September 29, 2014.

Want to Rebuild the Left? Take Socialism Seriously

Kshama Sawant for ''The Nation.'' March 23, 2015.

Bernie Sanders's Presidential Bid Represents a Long Tradition of American Socialism

Peter Dreier for ''The American Prospect.'' May 2015.

The Re-Emergence of Socialism in America

''Connecticut Public Radio, WNPR.'' November 18, 2015.

Socialism's Return

''The Nation.'' February 21, 2017.

CNBC. July 31, 2019.

Some young Americans warm to socialism, even Miami Cubans

Associated Press. August 25, 2019. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Socialist Movement In The United States Socialism in the United States, History of socialism Left-wing politics in the United States Political movements in the United States Socialist movements by country, United States

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

—the Lehr und Wehr Verein

The ''Lehr und Wehr Verein'' ("Educational and Defense Society") was a socialist military organization founded in 1875, in Chicago, Illinois. The group had been formed to counter the armed private armies of companies in Chicago.

The ''Lehr und W ...

—affiliated to the party. When the SLP reorganised as a Marxist party in 1890, its philosophy solidified and its influence quickly grew and by around the start of the 20th century the SLP was the foremost American socialist party.

Bringing to light the resemblance of the American party's politics to those of Lassalle, Daniel De Leon

Daniel De Leon (; December 14, 1852 – May 11, 1914), alternatively spelt Daniel de León, was a Curaçaoan-American socialist newspaper editor, politician, Marxist theoretician, and trade union organizer. He is regarded as the forefather o ...

emerged as an early leader of the Socialist Labor Party. He also adamantly supported unions, but criticized the collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The ...

movement within the United States at the time, favoring a slightly different approach. The resulting disagreement between De Leon's supporters and detractors within the party led to an early schism. De Leon's opponents, led by Morris Hillquit

Morris Hillquit (August 1, 1869 – October 8, 1933) was a founder and leader of the Socialist Party of America and prominent labor lawyer in New York City's Lower East Side. Together with Eugene V. Debs and Congressman Victor L. Berger, Hil ...

, left the Socialist Labor Party in 1901 as they fused with Eugene V. Debs's Social Democratic Party and formed the Socialist Party of America.

As a leader within the socialist movement, Debs' movement quickly gained national recognition as a charismatic orator. He was often inflammatory and controversial, but also strikingly modest and inspiring. He once said: "I am not a Labor Leader; I do not want you to follow me or anyone else. ..You must use your heads as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition." Debs lent a great and powerful air to the revolution with his speaking: "There was almost a religious fervor to the movement, as in the eloquence of Debs."

The Socialist movement became coherent and energized under Debs. It included "scores of former Populists, militant miners, and blacklisted railroad workers, who were ... inspired by occasional visits from national figures like Eugene V. Debs."

The first socialist to hold public office in the United States was Fred C. Haack, the owner of a shoe store in Sheboygan, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. Haack was elected to the city council in 1897 as a member of the Populist Party, but soon became a socialist following the organization of Social Democrats in Sheboygan. He was re-elected alderman in 1898 on the Socialist ticket, along with August L. Mohr, a local baseball manager. Haack served on the city council for sixteen years, advocating for the building of schools and public ownership of utilities. He was recognized as the first socialist officeholder in the United States at the 1932 national Socialist Party convention held in Milwaukee.

One of the first general strikes in the United States, the 1877 St. Louis general strike

The 1877 St. Louis general strike was one of the first general strikes in the United States. It grew out of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The strike was largely organized by the Knights of Labor and the Marxist-leaning Workingmen's Party, ...

grew out of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

. The general strike was largely organized by the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

and the Marxist-leaning Workingmen's Party

The Workingmen's Party of the United States (WPUS), established in 1876, was one of the first Marxist-influenced political parties in the United States. It is remembered as the forerunner of the Socialist Labor Party of America.

Organizational ...

, the main radical political party of the era. When the railroad strike reached East St. Louis, Illinois

East St. Louis is a city in St. Clair County, Illinois. It is directly across the Mississippi River from Downtown St. Louis, Missouri and the Gateway Arch National Park. East St. Louis is in the Metro-East region of Southern Illinois. Once a b ...

in July 1877, the St. Louis Workingman's Party led a group of approximately 500 people across the river in an act of solidarity with the nearly 1,000 workers on strike.

Ties to labor

The Socialist Party formed strong alliances with a number of labor organizations because of their similar goals. In an attempt to rebel against the abuses of corporations, workers had found a solution—or so they thought—in a technique of collective bargaining. By banding together into "unions" and by refusing to work, or "striking," workers would halt production at a plant or in a mine, forcing

The Socialist Party formed strong alliances with a number of labor organizations because of their similar goals. In an attempt to rebel against the abuses of corporations, workers had found a solution—or so they thought—in a technique of collective bargaining. By banding together into "unions" and by refusing to work, or "striking," workers would halt production at a plant or in a mine, forcing management

Management (or managing) is the administration of an organization, whether it is a business, a nonprofit organization, or a Government agency, government body. It is the art and science of managing resources of the business.

Management includ ...

to meet their demands. From Daniel De Leon's early proposal to organize unions with a socialist purpose, the two movements became closely tied. They shared as one major ideal the spirit of collectivism—both in the socialist platform and in the idea of collective bargaining.

The most prominent American unions of the time included the American Federation of Labor, the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

and the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed "Wobblies", is an international labor union that was founded in Chicago in 1905. The origin of the nickname "Wobblies" is uncertain. IWW ideology combines general ...

(IWW). In 1869, Uriah S. Stephens founded the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, employing secrecy and fostering a semireligious aura to "create a sense of solidarity." The Knights comprised in essence "one big union of all workers." In 1886, a convention of delegates from twenty separate unions formed the American Federation of Labor, with Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

as its head. It peaked at 4 million members. In 1905, the IWW (or "Wobblies") formed along the same lines as the Knights to become one big union. The IWW found early supporters in De Leon and in Debs.

The socialist movement was able to gain strength from its ties to labor. "The conomic panic of 1907, as well as the growing strength of the Socialists, Wobblies, and trade unions, sped up the process of reform." However, corporations sought to protect their profits and took steps against unions and strikers. They hired strikebreakers and pressured government to call in the state militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s when workers refused to do their jobs. A number of strikes collapsed into violent confrontations.

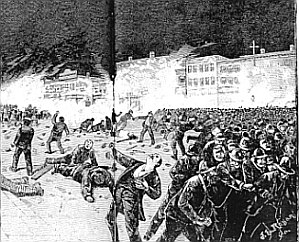

In May 1886, the Knights of Labor were demonstrating in the

In May 1886, the Knights of Labor were demonstrating in the Haymarket Square Haymarket Square may refer to:

* Haymarket Square (Boston), in Boston

* Haymarket Square (Chicago), in Chicago

* Haymarket affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or ...

in Chicago, demanding an eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the ...

in all trades. When police arrived, an unknown person threw a bomb into the crowd, killing one person and injuring several others. "In a trial marked by prejudice and hysteria," a court sentenced seven anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, six of them German-speaking, to death—with no evidence linking them to the bomb.

Strikes also took place that same month (May 1886) in other cities, including in Milwaukee, where seven people died when Wisconsin Governor Jeremiah M. Rusk ordered state militia troops to fire upon thousands of striking workers who had marched to the Milwaukee Iron Works Rolling Mill in Bay View on Milwaukee's south side.

In early 1894, a dispute broke out between George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 – October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman sleeping car and founded a company town, Pullman, for the workers who manufactured it. This ulti ...

and his employees. Debs, then leader of the American Railway Union, organized a strike. United States Attorney General Olney and President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

took the matter to court and were granted several injunctions preventing railroad workers from "interfering with interstate commerce and the mails."Dubofsky, 1994, p. 29. The judiciary of the time denied the legitimacy of strikers. Said one judge, "either ''Either/Or'' is an influential book by philosopher Søren Kierkegaard.

Either/Or and related terms may also refer to:

* ''Either/Or'' (book), a novel by Elif Batuman

* ''Either/Or'' (album), music by Elliott Smith

* ''Either/Or'' (TV series), a ...

the weapon of the insurrectionist, nor the inflamed tongue of him who incites fire and sword is the instrument to bring about reforms." This was the first sign of a clash between the government and socialist ideals.

In 1914, one of the most bitter labor conflicts in American history took place at a mining colony in Colorado called Ludlow

Ludlow () is a market town in Shropshire, England. The town is significant in the history of the Welsh Marches and in relation to Wales. It is located south of Shrewsbury and north of Hereford, on the A49 road which bypasses the town. The ...

. After workers went on strike in September 1913 with grievances ranging from requests for an eight-hour day to allegations of subjugation, Colorado governor Elias Ammons called in the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

in October 1913. That winter, Guardsmen made 172 arrests.Kick et al., 2002, p. 263.

The strikers began to fight back, killing four mine guards and firing into a separate camp where strikebreakers lived. When the body of a strikebreaker was found nearby, the National Guard's General Chase

Chase or CHASE may refer to:

Businesses

* Chase Bank, a national bank based in New York City, New York

* Chase Aircraft (1943–1954), a defunct American aircraft manufacturing company

* Chase Coaches, a defunct bus operator in England

* Chase Co ...

ordered the tent colony destroyed in retaliation.

"On Monday morning, April 20, two dynamite bombs were exploded, in the hills above Ludlow ... a signal for operations to begin. At 9 am a machine gun began firing into the tents here strikers were living and then others joined," one eyewitness reported as " e soldiers and mine guards tried to kill everybody; anything they saw move." That night, the National Guard rode down from the hills surrounding Ludlow and set fire to the tents. Twenty-six people, including two women and eleven children, were killed.

Union members now feared to strike. The military, which saw strikers as dangerous insurgents, intimidated and threatened them. These attitudes compounded with a public backlash against anarchists and radicals. As public opinion of strikes and of unions soured, the socialists often appeared guilty by association. They were lumped together with strikers and anarchists under a blanket of public distrust.

Early anarchism

The American anarchist

The American anarchist Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

(1854–1939) focused on economics, advocating "Anarchistic-Socialism" and adhering to the mutualist economics of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

and Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like James ...

while publishing his eclectic influential publication ''Liberty''. Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner (January 19, 1808May 14, 1887) was an American individualist anarchist, abolitionist, entrepreneur, essayist, legal theorist, pamphletist, political philosopher, Unitarian and writer.

Spooner was a strong advocate of the labor ...

(1808–1887), besides his individualist anarchist activism, was also an important anti-slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

activist and became a member of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

. Two individualist anarchists who wrote in Benjamin Tucker's ''Liberty'' were also important labor organizers of the time. Joseph Labadie

Charles Joseph Antoine Labadie (April 18, 1850 – October 7, 1933) was an American labor organizer, anarchist, Greenbacker, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet.

Biography

Early years

Jo Labadie was born on April 18, 1850, ...

was an American labor organizer, individualist anarchist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist and poet. Without the oppression of the state, Labadie believed, humans would choose to harmonize with "the great natural laws ... without robbing heirfellows through interest, profit, rent and taxes." However, he supported community cooperation as he supported community control of water utilities, streets and railroads.Martin, James J. (1970). ''Men Against the State: The Expositors of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827-1908.'' Colorado Springs: Ralph Myles Publisher. Although he did not support the militant anarchism of the Haymarket anarchists, he fought for clemency for the accused because he did not believe they were the perpetrators. In 1888, Labadie organized the Michigan Federation of Labor, became its first president and forged an alliance with Samuel Gompers

Samuel Gompers (; January 27, 1850December 13, 1924) was a British-born American cigar maker, labor union leader and a key figure in American labor history. Gompers founded the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and served as the organization's ...

. Dyer Lum

Dyer Daniel Lum (February 15, 1839 – April 6, 1893) was an American anarchist, labor activist and poet. A leading syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s, Lum is best remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarch ...

was a 19th-century American individualist anarchist labor activist and poet. A leading anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

and a prominent left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or a ...

of the 1880s, he is remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarcha-feminist

Anarcha-feminism, also referred to as anarchist feminism, is a system of analysis which combines the principles and power analysis of anarchist theory with feminism. Anarcha-feminism closely resembles intersectional feminism. Anarcha-feminism ...

Voltairine de Cleyre

Voltairine de Cleyre (November 17, 1866 – June 20, 1912) was an American anarchist known for being a prolific writer and speaker who opposed capitalism, marriage and the state as well as the domination of religion over sexuality and women's li ...

. Lum wrote prolifically, producing a number of key anarchist texts and contributed to publications including '' Mother Earth'', ''Twentieth Century'', ''Liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

'' (Tucker's individualist anarchist journal), ''The Alarm'' (the journal of the International Working People's Association

The International Working People's Association (IWPA), sometimes known as the "Black International," was an international anarchist political organization established in 1881 at a convention held in London, England. In America the group is best r ...

) and ''The Open Court'' among others. He developed a "mutualist" theory of unions and as such was active within the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

and later promoted anti-political

Anti-politics is a term used to describe opposition to, or distrust in, traditional politics. It is closely connected with anti-establishment sentiment and public disengagement from formal politics. In social science, anti-politics can indicat ...

strategies in the American Federation of Labor. Frustration with abolitionism, spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and Mind-body dualism, dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (w ...

and labor reform caused Lum to embrace anarchism and to radicalize workers, as he came to believe that revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

would inevitably involve a violent struggle between the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colo ...

and the employing class. Convinced of the necessity of violence to enact social change, he volunteered to fight in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

of 1861–1865, hoping thereby to bring about the end of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

.

By the 1880s, anarcho-communism

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains res ...

had reached the United States as can be seen in the publication of the journal ''Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly'' by Lucy Parsons

Lucy Eldine Gonzalez Parsons (born Lucia Carter; 1851 – March 7, 1942) was an American labor organizer, radical socialist and anarcho-communist. She is remembered as a powerful orator. Parsons entered the radical movement following her marriage ...

and Lizzy Holmes."Lucy Parsons: Woman Of Will"at the

Lucy Parsons Center

The Lucy Parsons Center, located in Jamaica Plain, Boston, Massachusetts, is an radical, nonprofit independent bookstore and community center. Formed out of the Red Word bookstore, it is collectively run by volunteers. The Center provides readin ...

Parsons debated in her time in the United States with fellow anarcha-communist Emma Goldman over issues of free love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

and feminism. Another anarcho-communist journal, '' The Firebrand'', later appeared in the United States. Most anarchist publications in the United States were in Yiddish, German, or Russian, but ''Free Society'' was published in English, permitting the dissemination of anarchist communist thought to English-speaking populations in the United States."''Free Society'' was the principal English-language forum for anarchist ideas in the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century." ''Emma Goldman: Making Speech Free, 1902–1909'', p.551. Around that time, these American anarcho-communist sectors entered into debate with the individualist anarchist faction led by Tucker. In February 1888, Berkman left his native Russia for the United States.Avrich, ''Anarchist Portraits'', p. 202. Soon after his arrival in New York City, Berkman became an anarchist through his involvement with groups that had formed to campaign to free the men convicted of the 1886 Haymarket bombing.Pateman, p. iii. Berkman and Goldman soon came under the influence of Johann Most

Johann Joseph "Hans" Most (February 5, 1846 – March 17, 1906) was a German-American Social Democratic and then anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "propaganda of the deed". His g ...

, the best-known anarchist in the United States and an advocate of propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pr ...

—''attentat'', or violence carried out to encourage the masses to revolt.Walter, p. vii. Berkman became a typesetter for Most's newspaper ''Freiheit

' is the German word for both liberty and political freedom.

Freiheit may also refer to:

Political parties

* Freie Demokratische Partei, a liberal party in Germany

* South Tyrolean Freedom (', STF), a nationalist political party active in South ...

''.

20th century

1900s–1920s: opposition to World War I and First Red Scare

Victor L. Berger ran for Congress and lost in

Victor L. Berger ran for Congress and lost in 1904

Events

January

* January 7 – The distress signal ''CQD'' is established, only to be replaced 2 years later by ''SOS''.

* January 8 – The Blackstone Library is dedicated, marking the beginning of the Chicago Public Library syst ...

before winning Wisconsin's 5th congressional district

Wisconsin's 5th congressional district is a congressional district of the United States House of Representatives in Wisconsin, covering most of Milwaukee's northern and western suburbs. It presently covers all of Washington and Jefferson count ...

seat in 1910