Socialism in Hong Kong on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Socialism in Hong Kong is a political trend taking root from

The

The

Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

and Leninism

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vanguardis ...

which was imported to Hong Kong in the early 1920s. Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

trends have taken various forms, including Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. Developed by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and various co ...

, Maoism

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Chi ...

, Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

, democratic socialism

Democratic socialism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self- ...

and liberal socialism

Liberal socialism is a political philosophy that incorporates liberal principles to socialism. This synthesis sees liberalism as the political theory that takes the inner freedom of the human spirit as a given and adopts liberty as the goal, ...

, with the Marxism–Leninists being the most dominant faction due to the influence of the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victoriou ...

(CCP) regime in the mainland. The "traditional leftists" became the largest force representing the pro-Beijing camp

The pro-Beijing camp, pro-establishment camp, pro-government camp or pro-China camp refers to a political alignment in Hong Kong which generally supports the policies of the Beijing central government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) t ...

in the post-war decades, which had an uneasy relationship with the colonial authorities. As the Chinese Communist Party adopted capitalist economic reforms from 1978 onwards and the pro-Beijing faction became increasingly conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

, the socialist agenda has been slowly taken up by the liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

-dominated pro-democratic camp.

1920s labour movements in Hong Kong

Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

was imported to China in the early 1900s and its literature was translated from German, Russian and Japanese into Cantonese and Mandarin. Following the Russian October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

led by the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

in 1917, a number of Chinese intellectuals emerged from the May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chinese ...

, which saw communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

as the solution to rescue China from its present plight. The first social organisation in Hong Kong was the Marxist Research Group in 1920, formed by Lin Junwei, a school inspector of the Education Department, Zhang Rendao, a graduate from the Queen's College, and Li Yibao, a primary school teacher.

In July 1921, the Chinese Communist Party

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), officially the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). Under the leadership of Mao Zedong, the CCP emerged victoriou ...

(CCP) was formally established in Shanghai. The Communist Party was modelled on Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

's theory of a vanguard party

Vanguardism in the context of Leninist revolutionary struggle, relates to a strategy whereby the most class-conscious and politically "advanced" sections of the proletariat or working class, described as the revolutionary vanguard, form organi ...

, and was under the guidance of the Soviet-led Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet Union, Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to ...

. The Marxist Research Group formed a connection with the CCP in Guangdong and later formed the New Chinese Students Club - Hong Kong Branch and subsequently the Chinese Socialist Youth League - Hong Kong Special Branch, under the Guangdong Socialist Youth League. In mid-1924, the CCP set up a branch in Hong Kong.

1922 Seamen's strike

The

The 1922 seamen's strike

The Seamen's Strike of 1922 began on 12 January 1922, when Chinese seamen from Hong Kong and Canton (now Guangzhou) went on strike for higher wages. Led by the Seamen's Union after shipping companies refused to increase salaries by 40%, the strike ...

became the most important episode of the labour movement in China and Hong Kong. On 13 January 1922, against the backdrop of skyrocketing prices, seamen in Hong Kong launched a well-organised strike which lasted 56 days and involved 120,000 seamen at its peak. Having received organisational and financial support from Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

's left-leaning Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

government in Guangzhou

Guangzhou (, ; ; or ; ), also known as Canton () and alternatively romanized as Kwongchow or Kwangchow, is the capital and largest city of Guangdong province in southern China. Located on the Pearl River about north-northwest of Hong Kon ...

, the Chinese Seamen's Union led the Hong Kong strikers to victory.

Although the Communists played no leadership role in the strike, some Communists in Hong Kong participated and others in the neighbouring Guangzhou made supportive speeches and published the strikers' manifesto. Su Zhaozheng

Su Zhaozheng () (1885, Qi'ao Island – 1929, Shanghai), early phase leader of the Communist Party of China, labour movement activist. A native of the Qi'ao Island of Xiangshan County, Guangdong Province, he became a sailor, active in Sun Yats ...

and Lin Weimin, the two leaders of the seamen's strike, would later join the Communist Party. Henk Sneevliet

Hendricus Josephus Franciscus Marie (Henk) Sneevliet, known as Henk Sneevliet or by the ''pseudonym'' "Maring" (1883 - 1942), was a Dutch Communism, Communist, who was active in both the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies. As a functionary of t ...

, representative of the Comintern in China who was greatly impressed by the strike's success, concluded that the strike was "undoubtedly the most important event in the young history of the Chinese labour movement." He also held talks with Sun Yat-sen from 23 to 25 December 1921 in Guilin

Guilin ( Standard Zhuang: ''Gveilinz''; alternatively romanized as Kweilin) is a prefecture-level city in the northeast of China's Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. It is situated on the west bank of the Li River and borders Hunan to the nort ...

about possible cooperation between the Kuomintang and the Communists. Sneevliet became more actively involved in organising the First United Front

The First United Front (; alternatively ), also known as the KMT–CCP Alliance, of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), was formed in 1924 as an alliance to end warlordism in China. Together they formed the National Revo ...

between the two parties after he saw the support given by the Kuomintang in the Hong Kong seamen's strike.

1925–26 Guangzhou–Hong Kong strike

The Guangzhou–Hong Kong strike between 1925 and 1926 was another key historical event of the labour movement in Hong Kong. It was triggered by the killing of a worker named Gu Zhenghong, who was a Communist Party member in a Japanese-owned mill in February 1925. The Communists launched ananti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

demonstration in the Shanghai International Settlement

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdiction ...

on 30 May, which is now referred to as the May 30th Movement

The May Thirtieth Movement () was a major labor and anti-imperialist movement during the middle-period of the Republic of China era. It began when the Shanghai Municipal Police opened fire on Chinese protesters in Shanghai's International Settl ...

. A Sikh

Sikhs ( or ; pa, ਸਿੱਖ, ' ) are people who adhere to Sikhism, Sikhism (Sikhi), a Monotheism, monotheistic religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Gu ...

policeman under British command opened fire on a crowd of Chinese demonstrators, killing nine and injuring much of the crowd. The incident fuelled even more anti-British sentiment across China. The Kuomintang gave funds to the Communists, who then in turn organised the strike on 18 June, which began with the walkout of over 80 percent of the senior students from the Queen's College. Many seamen, tramway drivers, printers and students led the walkout and left for Guangzhou. On 23 June, the British and French troops opened fire on the strikers, killing 52 people and injuring over 170 demonstrators in the foreign concession of Shamian Island

Shamian (also romanized as Shameen or Shamin, both from its Cantonese pronunciation) is a sandbank island in the Liwan District of Guangzhou, Guangdong, China. The island's name literally means "sandy surface" in Chinese.

The territory ...

, which provoked more workers in Hong Kong who were working for foreign corporations to join the strike.

Various unions representing Hong Kong and mainland workers convened a conference in Guangzhou and formed the Guangzhou–Hong Kong Strike Committee chaired by Su Zhaozheng

Su Zhaozheng () (1885, Qi'ao Island – 1929, Shanghai), early phase leader of the Communist Party of China, labour movement activist. A native of the Qi'ao Island of Xiangshan County, Guangdong Province, he became a sailor, active in Sun Yats ...

, under the direction of the CCP. The Strike Committee called for a boycott of all British goods and a ban on foreign ships utilising Hong Kong's ports. The strike paralysed the Hong Kong economy, as food prices began to soar, tax revenue began to drop sharply and the banking system started collapsing.

The strike began to fall apart after Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

died in March 1925 and Liao Zhongkai

Liao Zhongkai (April 23, 1877 – August 20, 1925) was a Chinese-American Kuomintang leader and financier. He was the principal architect of the first Kuomintang–Chinese Communist Party (KMT–CCP) United Front in the 1920s. He was assassina ...

, a left-wing leader within the Kuomintang, was assassinated in August. After commander-in-chief of the National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

seized power, he confiscated the arms of the Strike Committee. The strike received less support as Chiang began his Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The ...

in the middle of 1926. On 10 October 1926, the boycott was formally lifted after a compromise settlement was reached with the British, which signified the end of the 16-month strike. Several leftist labour unions including the Chinese Seamen's Union were prosecuted and their leaders arrested. New legislation to ban unions from being affiliated with organisations outside the colony and to outlaw strikes with political causes were also enacted.

1930s to 40s: From the anti-communist purge to the anti-Japanese resistance

Colonial suppression

The Shanghai massacre of April 1927 which was caused byChiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

's Kuomintang government led to the escape and relocation of the CCP's Guangzhou branch into Hong Kong until the Second United Front

The Second United Front ( zh, t=第二次國共合作 , s=第二次国共合作 , first=t ) was the alliance between the ruling Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to resist the Japanese invasion of China during the Seco ...

between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party was formed in 1936. The Communists in Hong Kong at that time were actively involved in military actions to overthrow the Kuomintang government in Guangdong

Guangdong (, ), alternatively romanized as Canton or Kwangtung, is a coastal province in South China on the north shore of the South China Sea. The capital of the province is Guangzhou. With a population of 126.01 million (as of 2020) ...

.

The Communists experienced a period of White Terror

White Terror is the name of several episodes of mass violence in history, carried out against anarchists, communists, socialists, liberals, revolutionaries, or other opponents by conservative or nationalist groups. It is sometimes contrasted wit ...

during the late 1920s to 1930s in Hong Kong as Hong Kong Governor

The governor of Hong Kong was the representative of the British Crown in Hong Kong from 1843 to 1997. In this capacity, the governor was president of the Executive Council and commander-in-chief of the British Forces Overseas Hong Kong. ...

Cecil Clementi

Sir Cecil Clementi (; 1 September 1875 – 5 April 1947) was a British colonial administrator who served as Governor of Hong Kong from 1925 to 1930, and Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the Straits Settlements from 1930 to 1934.

Early lif ...

developed a close relationship with Kuomintang with the intention of suppressing suspected Communist and socialist activities. Despite facing pressure from the colonial government, Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as ('Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as Prime ...

managed to found the Indochinese Communist Party

The Indochinese Communist Party (ICP), km, បក្សកុម្មុយនីស្តឥណ្ឌូចិន, lo, ອິນດູຈີນພັກກອມມູນິດ, zh, t=印度支那共產黨 was a political party which was t ...

in Hong Kong in February 1930 before he was arrested by the British authorities in June.

Anti-Japanese guerilla warfare

During theSecond Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

, the Communist Party set up the Office of the Eighth Route Army

The Eighth Route Army (), officially known as the 18th Group Army of the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China, was a group army under the command of the Chinese Communist Party, nominally within the structure of the Chinese ...

which engaged works for United Front in Hong Kong and raising funds disguised as the Yue Hwa Company. The Chinese Seamen's Union also organised a resistance movement by recruiting volunteers to cross over to Guangdong and wage a guerrilla war behind Japanese lines led by Zeng Sheng

Zeng Sheng ( zh, 曾生, 19 December 1910 – 20 November 1995), born Zeng Zhensheng (), was a Chinese military officer and politician. His name is also spelt as Tsang Sang, Tsang Shang, Jung Sung and Chung Sung in various sources. Tsang is best ...

. There were also the Huizhou-Bao'an People's Anti-Japanese Guerrilla Force and the Dongguan-Bao'an-Huizhou People's Anti-Japanese Guerrilla Force militias which were formed in 1938. Commanded by Cai Guoliang, the guerrillas began operations in 1941 before the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong. On 2 December 1943, the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party

The Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, officially the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, is a political body that comprises the top leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It is currently composed of 205 fu ...

regrouped the five guerrilla fighting units within the Pearl River Delta

The Pearl River Delta Metropolitan Region (PRD; ; pt, Delta do Rio das Pérolas (DRP)) is the low-lying area surrounding the Pearl River estuary, where the Pearl River flows into the South China Sea. Referred to as the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Mac ...

into the East River Column directly under Communist command. By 1943, the East River guerrillas had the total strength of about 5,000 full-time soldiers, who were divided into six detachments.

By the time of the Japanese surrender, the Communist Hong Kong-Kowloon Independence Brigade was the only military force left within the territory. The guerrillas took control of Tai Po

Tai Po is an area in the New Territories of Hong Kong. It refers to the vicinity of the traditional market towns in the area presently known as Tai Po Old Market or Tai Po Kau Hui () (the original "Tai Po Market") on the north of Lam Tsue ...

and Yuen Long

Yuen Long is a town in the western New Territories, Hong Kong. To its west lie Hung Shui Kiu (), Tin Shui Wai, Lau Fau Shan and Ha Tsuen, to the south Shap Pat Heung and Tai Tong, to the east Au Tau and Kam Tin (), and to the north Nam Sang W ...

and all other market towns in the New Territories

The New Territories is one of the three main regions of Hong Kong, alongside Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula. It makes up 86.2% of Hong Kong's territory, and contains around half of the population of Hong Kong. Historically, it ...

as well as outlying islands, until the British forces arrived on 30 August 1945 and accepted the formal surrender of the Japanese Empire. The agreement between the Hong Kong-Kowloon Independence Brigade and the British was reached, as the Communists would be allowed to set up a liaison office, and its members would be guaranteed freedom of travel and publication as long as they refrained from carrying out "unlawful" activities. The liaison office later became the New China News Agency

Xinhua News Agency (English pronunciation: )J. C. Wells: Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, 3rd ed., for both British and American English, or New China News Agency, is the official state news agency of the People's Republic of China. Xinhua ...

, headed by Qiao Guanhua

Qiao Guanhua (; March 28, 1913 – September 22, 1983

." '' The Hong Kong-Kowloon Independence Brigade fought with the Kuomintang as the

The

The

The

The

In October 2006, Andrew To, legislator

In October 2006, Andrew To, legislator

." '' The Hong Kong-Kowloon Independence Brigade fought with the Kuomintang as the

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on m ...

resumed right after the end of the Sino-Japanese War.

Chinese Civil War

A Hong Kong Central Branch Bureau headed by Fang Fang was set up in June 1947 to spearhead propaganda campaigns against Chiang Kai-shek and his ally, the United States of America, as well as help facilitate guerrilla warfare in mainland China. A Hong Kong Works Committee was also set up to organiseunited front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political a ...

works programmes in education, publication, literature and art sectors, with the goal of bringing people to the side of the communist cause. Furthermore, the Kuomintang Revolutionary Committee, a party that broke away from Chiang Kai-shek, and the Chinese Democratic League, a small party consisting of intellectuals, were brought to the side of the Communists.

Communism in Hong Kong after 1949

In 1950, the United Kingdom became the first western nation to officially recognise the communist government of thePeople's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. As the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

approached and the outbreak of the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

started in 1950, the British colonial government tightened their control over local Communist activities, while communist parties remained mostly underground.

1 March Incident of 1952

The 1 March Incident of 1952 was the first major clash between the colonial authorities and the local communists. A huge crowd organised by the local communist party gathered around Jordan Road inTsim Sha Tsui

Tsim Sha Tsui, often abbreviated as TST, is an list of areas of Hong Kong, urban area in southern Kowloon, Hong Kong. The area is administratively part of the Yau Tsim Mong District. Tsim Sha Tsui East is a piece of land reclaimed from the Hu ...

, with the goal of meeting with a delegation from Guangzhou to talk with the victims of the fire disaster at the Shek Kip Mei

Shek Kip Mei, is an area in New Kowloon, to the northeast of the Kowloon Peninsula of Hong Kong. It borders Sham Shui Po and Kowloon Tong.

History

At the time of the 1911 census, the population of Shek Kip Mei was 72.

A major fire on 25 ...

squatter area. The crowd confronted the police after news emerged of delegates being stopped at Fanling

Fanling ( zh, t=粉嶺; also spelled Fan Ling or Fan Leng) is a town in the New Territories East of Hong Kong. Administratively, it is part of the North District. Fanling Town is the main settlement of the Fanling area. The name Fanling i ...

and then being sent back to China. More than a hundred people were arrested, while a textile worker was shot to death. The pro-Communist ''Ta Kung Pao

''Ta Kung Pao'' (; formerly ''L'Impartial'') is the oldest active Chinese language newspaper in China. Founded in Tianjin in 1902, the paper is state-owned, controlled by the Liaison Office of the Central Government after the Chinese Civil War ...

'' was banned from publication for six months after it picked up the story and reprinted an editorial from the ''People's Daily

The ''People's Daily'' () is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The newspaper provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of the CCP. In addition to its main Chinese-language ...

'', which denounced the colonial government and its repressive actions.

Mok Ying-kwai, the leader of the sympathetic delegate, was deported to the mainland and left the Hong Kong Chinese Reform Association

The Hong Kong Chinese Reform Association () is a pro-Beijing political organisation established in 1949 in Hong Kong. It was one of the three pillars of the pro-Communist leftist camp throughout most of the time in Hong Kong under colonial rul ...

(HKCRA), a leaderless organisation first set up in 1949 to demand constitutional reform. Percy Chen

Percy Chen (; 1901–20 February 1989) was a Chinese Trinidadian lawyer of Hakka descent, as well as a journalist, businessman and political activist.

Family and early life

Chen was born in Belmont, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, British West Indies, ...

, the son of Eugene Chen

Eugene Chen or Chen Youren (; July 2, 1878, San Fernando, Trinidad and Tobago – 20 May 1944, Shanghai), known in his youth as Eugene Bernard Achan, was a Chinese Trinidadian lawyer who in the 1920s became Chinese foreign minister. He was known ...

and another leader of the delegation would later take charge of the association. The association became one of the three pillars of the pro-Communist faction, next to the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions

The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU) is a pro-Beijing labour and political group established in 1948 in Hong Kong. It is the oldest and largest labour group in Hong Kong with over 420,000 members in 253 affiliates and associated ...

(HKFTU) and the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce

The Chinese General Chamber of Commerce (CGCCHK; ) is a non-profit organization of local Chinese firms and businessmen based in Hong Kong. It was founded in 1900 by Ho Fook and Lau Chu-pak, two prominent leaders of the Chinese community during th ...

(CGCC).

1967 Leftist riots in Hong Kong

TheHong Kong Federation of Trade Unions

The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU) is a pro-Beijing labour and political group established in 1948 in Hong Kong. It is the oldest and largest labour group in Hong Kong with over 420,000 members in 253 affiliates and associated ...

(HKFTU), which was established in 1948, has functioned as "friendly societies" based in industry and craft-based fraternities, and provided benefits and other supplementary aids to the veteran members who was under threat of unemployment and low wages during the 1950s and 1960s. It had a fierce contest with the pro-Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

Hong Kong and Kowloon Trades Union Council

The Hong Kong and Kowloon Trades Union Council is the third largest trade union federation in Hong Kong, after the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions, Federation of Trade Unions (FTU) and pro-Beijing Federation of Hong Kong and Kowloon Labou ...

(TUC) in industries, trades, and workplaces as part of the "left-right" ideological divide in that period.

The

The Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a sociopolitical movement in the People's Republic of China (PRC) launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976. Its stated goal ...

launched by Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

in mainland China inspired a tendency of radicalism within Maoist

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

organisations in 1966. In December 1966, a leftist-led demonstration in Macao successfully made the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

Governor of Macao sign an apology for anti-worker measures that was covertly demanded by Beijing. Inspired by the protests in Macao, in May 1967, the Hong Kong communists escalated labour disputes in an artificial flower factory into an anti-government demonstration after many workers and labour representatives were arrested in the aftermath of violent clashes between workers and riot police on 6 May. On 16 May, the leftists formed the Committee of Hong Kong and Kowloon Compatriots from All Circles for Struggle Against British Persecution in Hong Kong and appointed Yeung Kwong

Yeung Kwong ( zh, t=楊光; 1926 – 16 May 2015) was a Hong Kong trade unionist and labour rights activist. He served as chairman of the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU) from 1962 to 1980 and as its president from 1980 to 1988. H ...

of the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions as the Chairman of the committee.

The committee organised and coordinated a series of large-scale demonstrations. Hundreds of supporters from various leftist organisations demonstrated outside the Government House

Government House is the name of many of the official residences of governors-general, governors and lieutenant-governors in the Commonwealth and the remaining colonies of the British Empire. The name is also used in some other countries.

Gover ...

, chanting communist and socialist slogans and wielding placards with quotes from the ''Quotations From Chairman Mao Zedong

''Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung'' () is a book of statements from speeches and writings by Mao Zedong (formerly romanized as Mao Tse-tung), the former Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, published from 1964 to about 1976 and widel ...

'' in their left hands. At the same time, many workers started general strikes, with Hong Kong's transport services in particular being badly disrupted. Further violence erupted on 22 May, with another 167 people being arrested. The rioters began to adopt more sophisticated tactics, such as throwing stones at police or vehicles passing by, before retreating into leftist "strongholds" such as newspaper offices, banks or department stores once the police arrived.

Five policemen were killed when pro-Chinese militias exchanged fire with the Hong Kong Police

The Hong Kong Police Force (HKPF) is the primary law enforcement, investigative agency, and largest disciplined service under the Security Bureau of Hong Kong. The Royal Hong Kong Police Force (RHKPF) reverted to its former name after the t ...

at the Hong Kong border with mainland China in Sha Tau Kok

Sha Tau Kok is a closed city, closed town in Hong Kong. The last remaining major settlement in the Frontier Closed Area, it is Hong Kong's northernmost town.

Geography

The small rural village of Sha Tau Kok is located on the northern sh ...

on 8 July, which fueled speculation that the Communist government's takeover of Hong Kong was imminent. The committee's call for a general strike was unsuccessful, and the colonial government declared a state of emergency. Leftist newspapers were banned from publishing, schools populated by leftists were shut down, and many leftist leaders were arrested and detained, and some of them were later deported to mainland China. The leftists retaliated by planting bombs throughout the city which began to randomly detonate and seriously disrupted the daily life of ordinary people, erroneously killing several pedestrians, which sharply turned public opinion against the rioters. The riots did not end until October 1967. Many labour activists and HKFTU cadres were imprisoned and deported to China, and due to its violent campaign of terrorism and bomb attacks, the HKFTU suffered serious setbacks in both public esteem and official tolerance by the Hong Kong government.

1960s movement for autonomy and sovereignty

Asides from the left-right polarisation between the Kuomintang and the Communists, there were also calls for liberalisation andself-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

during the 1950s and 1960s. The self-proclaimed anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

and anti-colonial

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on independence m ...

Democratic Self-Government Party of Hong Kong

The Democratic Self-Government Party of Hong Kong was the first political party calling for self-government in Hong Kong established in 1964. it was founded by Ma Man-fai, chairman of the United Nations Association of Hong Kong, lawyer Chang L ...

was founded in 1963, which called for a fully autonomous and sovereign government, in which the Chief Minister would be elected by all Hong Kong residents through universal suffrage, while the British government would only preserve its authority over Hong Kong's diplomacy and military.

In addition, the Hong Kong Socialist Democratic Party was founded by Sun Pao-kang, who was a member of the Chinese Democratic Socialist Party, along with the Labour Party of Hong Kong, which was founded by Tang Hon-tsai and K. Hopkin-Jenkins, who directly professed socialist ideology by promoting a welfare state and common ownership

Common ownership refers to holding the assets of an organization, enterprise or community indivisibly rather than in the names of the individual members or groups of members as common property.

Forms of common ownership exist in every economi ...

of the means of production, distribution, and exchange. However, after failing to obtain any meaningful concessions from the colonial government of Hong Kong, all of the parties advocating sovereignty and autonomy ceased to exist by the mid-1970s.

1970s youth movements

The 1970s saw a wave of youth movements, which emerged from events like theBaodiao movement

Baodiao movement (, literally ''Defend the Diaoyu Islands movement'') is a social movement originating among Republic of China students in the United States in the 1970s, and more recently expressed in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan that ass ...

when the question of the sovereignty of the Diaoyu Islands

The are a group of uninhabited islands in the East China Sea, administered by Japan. They are located northeast of Taiwan, east of China, west of Okinawa Island, and north of the southwestern end of the Ryukyu Islands. They are known in main ...

appeared in the early 1970s. Led by mostly the young generation of the baby boomers

Baby boomers, often shortened to boomers, are the Western demographic cohort following the Silent Generation and preceding Generation X. The generation is often defined as people born from 1946 to 1964, during the mid-20th century baby boom. Th ...

, about 30 demonstrations were organised between February 1971 and May 1972. A violent clash broke out on 7 July 1971, in a demonstration launched by the Hong Kong Federation of Students

The Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS, or 學聯) is a student organisation founded in May 1958 by the student unions of four higher education institutions in Hong Kong. The inaugural committee had seven members representing the four sc ...

(HKFS) at Victoria Park Victoria Park may refer to:

Places Australia

* Victoria Park Nature Reserve, a protected area in Northern Rivers region, New South Wales

* Victoria Park, Adelaide, a park and racecourse

* Victoria Park, Brisbane, a public park and former golf ...

in which police commissioner Henry N. Whitlely violently assaulted protesters with his baton. 21 protesters were arrested and dozens more were injured. The event became one of the catalysts of the 1970s youth movements in Hong Kong.

Social action faction

In the universities, theMaoist

Maoism, officially called Mao Zedong Thought by the Chinese Communist Party, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed to realise a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of Ch ...

-dominated student unions faced challenges from the non-Maoist leftists, who were more critical of the Chinese Communist Party and criticised the blind-eyed ultranationalist sentiments of the Maoists. Instead, they focused more on the injustices in Hong Kong's colonial capitalist system and to help emancipate the indigent and underprivileged members of the community. The social action faction was influenced by the doctrines and ideals of the New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement mainly in the 1960s and 1970s consisting of activists in the Western world who campaigned for a broad range of social issues such as civil and political rights, environmentalism, feminism, gay rights, g ...

, which was emerging in the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

during the 1960s and 1970s, and was introduced to Hong Kong by Tsang Shu-ki, editor of the ''Socialist Review'' and ''Sensibility'', two left-wing Hong Kong periodicals published in that time. The social action faction actively participated in the 1970s non-aligned social movements, such as the Chinese Language Movement, the anti-corruption movement, the "Defend the Diaoyu Islands" movement et al., in which many of the student leaders became the main figureheads and leaders of the contemporary pro-democracy camp

The pro-democracy camp, also known as the pan-democracy camp, is a political alignment in Hong Kong that supports increased democracy, namely the universal suffrage of the Chief Executive and the Legislative Council as given by the Basic L ...

.

The Yaumatei

Yau Ma Tei is an area in the Yau Tsim Mong District in the south of the Kowloon Peninsula in Hong Kong.

Name

''Yau Ma Tei'' is a phonetic transliteration of the name (originally written as ) in Cantonese. It can also be spelt as Yaumatei, ...

resettlement movement was one of the movements that attempted to pressure the colonial government into resettling the boat people

Vietnamese boat people ( vi, Thuyền nhân Việt Nam), also known simply as boat people, refers to the refugees who fled Vietnam by boat and ship following the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. This migration and humanitarian crisis was at its h ...

located in the Yaumatei typhoon shelter into affordable public housing in 1971–72 and again in 1978–79. The social activists founded their own organisation with several Maryknoll

Maryknoll is a name shared by a number of related Catholic organizations, including the Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers (also known as the Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America or the Maryknoll Society), the Maryknoll Sisters, and the Mary ...

s and the staffs of the Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee

The Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee ( Chinese: 香港基督教工業委員會, also called as HKCIC) is a non-governmental pressure group that focuses on labor welfare policy and industrial safety. The group was founded in 1966, original ...

(HKCIC), which was called the Society for Community Organisation

The Society for Community Organization (SoCO) () is a non-governmental and human rights advocacy group in Hong Kong. The group was founded in 1971 by church members. It is also financially supported by donations from various churches, overseas f ...

(SoCO) in 1971. Moreover, the social workers who felt constrained by the pro-government Hong Kong Social Workers' Association founded the Hong Kong Social Workers' General Union

Hong Kong Social Workers' General Union (HKSWGU) is a trade union for the social workers in Hong Kong. It was established in 1980. The current president, Cheung Kwok-che is the member in the Legislative Council of Hong Kong. It is one of the trad ...

(HKSWGU) in 1980.

Maoist faction

The Maoists, also called the "pro-China faction", initially retained their dominance in the universities and youth movements. In December 1971, theHong Kong University Students' Union

The Hong Kong University Students' Union (HKUSU; ) was a students' union in Hong Kong registered under the Societies Ordinance founded in 1912. It was the officially recognized undergraduate students' association of the University of Hong Kong ...

(HKUSU) organised its first visit into mainland China. In the next few years, the student activists undertook further tours into mainland China, ran Chinese study groups, and organised the so-called "Chinese Weeks", to carry out their mission of educating Hong Kong students about the achievements of China's socialist government.

In April 1976, the death of Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai (; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman and military officer who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, premier of the People's Republic of China from 1 October 1949 until his death on 8 J ...

triggered a large-scale demonstration at the Tiananmen Square

Tiananmen Square or Tian'anmen Square (; 天安门广场; Pinyin: ''Tiān'ānmén Guǎngchǎng''; Wade–Giles: ''Tʻien1-an1-mên2 Kuang3-chʻang3'') is a city square in the city center of Beijing, China, named after the eponymous Tiananmen (" ...

in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

which was suppressed by the orthodox Gang of Four

The Gang of Four () was a Maoist political faction composed of four Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials. They came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and were later charged with a series of treasonous crimes. The gang ...

. The Maoist-dominated Hong Kong Federation of Students

The Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS, or 學聯) is a student organisation founded in May 1958 by the student unions of four higher education institutions in Hong Kong. The inaugural committee had seven members representing the four sc ...

(HKFS) passed a resolution titled "Counterattack the Right-Deviationist Reversal-of-Verdicts Trend

Counterattack the Right-Deviationist Reversal-of-Verdicts Trend (), later known as Criticize Deng, Counterattack the Right-Deviationist Reversal-of-Verdicts Trend (), was a Chinese political campaign launched by Mao Zedong in November 1975 against ...

" on 3 May 1976, condemning the Tiananmen protesters as "anti-socialists" and "subversives".

However, the resolution faced stiff opposition from the Trotskyists

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

, who issued a statement in a left-wing periodical titled ''October Review'', condemning the Chinese Communist Party and calling for an uprising of the Chinese workers and peasants to topple the CCP's regime. By the end of 1976, the death of Mao Zedong which was followed by the arrest and downfall of the Gang of Four

The Gang of Four () was a Maoist political faction composed of four Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials. They came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and were later charged with a series of treasonous crimes. The gang ...

severely demoralised the Maoists in Hong Kong and damaged their formerly unshakeably idealistic belief in Marxist–Leninist socialism. The official verdict of the Tiananmen Incident was also reversed after Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. After CC ...

came to power in 1978, as it would later be officially hailed as a display of patriotism, which further diminished the prestige of the Maoists, eventually wiping out their influence from Hong Kong's left-wing movements.

Trotskyists and anarchists

TheRevolutionary Communist Party of China

The Revolutionary Communist Party of China is a Trotskyist political party based in Hong Kong. The party's members fled from Mainland China after the anti-Trotskyist Communist Party of China seized power in 1949, and its activities have since ...

, which was founded in September 1948 by Chinese Trotskyists

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

and led by Peng Shuzhi

Peng Shuzhi (also spelled Peng Shu-tse; ;alias Ivan Petrov, Xi Zhao, Nan Guan, Tao Bo, Ou Bo. 1896–1983) was an early leader of the Chinese Communist Party who was expelled from the party for being a Trotskyist. After the Communist victory in Chi ...

on the basis of the Communist League of China fled to Hong Kong after the Chinese Communist Party's takeover of China in 1949. The party has legally been active and has been publishing the ''October Review'' periodical in Hong Kong since 1974.

New Trotskyist and anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

trends emerged from a student movement that broke out at the Chu Hai College

Chu Hai College of Higher Education is a private degree-granting institute in Tuen Mun, Hong Kong. At present, Chu Hai College is recognised as an Approved Post Secondary College under the Post Secondary Colleges Ordinance (Cap 320).Chu Hai Coll ...

in 1969. The students were disillusioned with the Communist Party in the aftermath of events such as the Cultural Revolution and the Lin Bao Incident, which heavily discredited the CCP.

In 1972, several members of Hong Kong's youth made an expensive trip to Paris to meet with exiled Chinese Trotskyists including Peng Shuzhi. Several of the returnees such as John Shum

John Sham Kin-Fun (born 1952) is a Hong Kong actor and film producer. His English name is sometimes written as John Shum.

Whilst known primarily for his comedic acting roles in Hong Kong cinema, he also spent time as a political activist.

Biogra ...

and Ng Chung-yin Ng Chung-yin (; 1946 – 21 April 1994) was a Hong Kong Trotskyist activist. He made his fame in the student strike at the Chu Hai College in 1969 and became an influential figure in the 1960s and 70s student movements. He was the founder of the R ...

left the ''70's Biweekly'', which was at the time dominated by anarchists, and established a Trotskyist youth group called the Revolutionary International League, after meeting with Peng Shuzhi in Paris. It later took the name "Socialist League", and soon after changed its name into the Revolutionary Marxist League, which became the Chinese section of the Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) is a revolutionary socialist international organization consisting of followers of Leon Trotsky, also known as Trotskyists, whose declared goal is the overthrowing of global capitalism and the establishment of wor ...

in 1975. Famous members of the group include Leung Kwok-hung

Leung Kwok-hung ( zh, t=梁國雄; born 27 March 1956), also known by his nickname "Long Hair" (), is a Hong Kong politician and social activist. He was a member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, Legislative Council, representing the N ...

, who formed the April Fifth Action

April Fifth Action () is a Hong Kong left-wing group named after the first Tiananmen incident of 5 April 1976. While the organization's Chinese name translates as "April Fifth Action", English-language media in Hong Kong usually refer to it as th ...

after the league was disbanded in 1990, and Leung Yiu-chung

Leung Yiu-chung (, born 19 May 1953) is a Hong Kong politician. He is a member of the pro-labour Neighbourhood and Worker's Service Centre, part of the pan-democracy camp, and a former long-time member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong ...

of the Neighbourhood and Worker's Service Centre

The Neighbourhood and Worker's Service Centre (NWSC) is a pro-democracy political group in Hong Kong, holding one seat in the Legislative Council from 1995 to 1997, and since 1998. It was founded in 1985, with its roots in the New Youth Study S ...

, who both became members of the Legislative Council in the 1990s and 2000s.

1980s to 90s: The sweep of neoliberalism

AfterDeng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping (22 August 1904 – 19 February 1997) was a Chinese revolutionary leader, military commander and statesman who served as the paramount leader of the People's Republic of China (PRC) from December 1978 to November 1989. After CC ...

came to power in 1978, China underwent a period of radical economic liberalisation

Economic liberalization (or economic liberalisation) is the lessening of government regulations and restrictions in an economy in exchange for greater participation by private entities. In politics, the doctrine is associated with classical liber ...

, which the Communist Party later labelled as "socialism with Chinese characteristics

Socialism with Chinese characteristics ( zh, s=中国特色社会主义, hp=Zhōngguó tèsè shèhuìzhǔyì) is a set of political theories and policies of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that are seen by their proponents as representing M ...

", although the Chinese economy was largely exhibiting state capitalism

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes business and commercial (i.e. for-profit) economic activity and where the means of production are nationalized as state-owned enterprises (including the processes of capital a ...

. At the same time, Beijing also signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration

The Sino-British Joint Declaration is a treaty between the governments of the United Kingdom and China signed in 1984 setting the conditions in which Hong Kong was transferred to Chinese control and for the governance of the territory after ...

with the British government, which determined that Hong Kong shall be transferred to mainland China in 1997. The trend of neoliberalism also dominated in Hong Kong, as the city was undergoing a transformation from an industrial-based economy to one based on finance and real estate.

Pro-democrats

Some leftists, such as Tsang Shu-ki, saw a chance for Hong Kong to transform into a reformed capitalist mixed economy, a welfare state, and a democratic society, which would integrate into a democratic socialist China. In 1983, Tsang co-founded theMeeting Point

Meeting Point (Chinese: 匯點) was a liberal political organisation and party in Hong Kong formed by a group of former student activists in the 1970s and intellectuals for the discussion for the Sino-British negotiation on the question of Hong ...

, which became one of the first groups to welcome the transfer of Hong Kong to mainland China. However, Trotskyists such as Leung Kwok-hung

Leung Kwok-hung ( zh, t=梁國雄; born 27 March 1956), also known by his nickname "Long Hair" (), is a Hong Kong politician and social activist. He was a member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, Legislative Council, representing the N ...

harshly criticised Tsang's reformist ideas, instead calling for an uprising against the capitalist-colonial regime in Hong Kong and the bureaucratic regime in mainland China under the banner of social democracy

Social democracy is a Political philosophy, political, Social philosophy, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocati ...

.

Meeting Point

Meeting Point (Chinese: 匯點) was a liberal political organisation and party in Hong Kong formed by a group of former student activists in the 1970s and intellectuals for the discussion for the Sino-British negotiation on the question of Hong ...

and the grassroots Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People's Livelihood

The Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People's Livelihood (ADPL) is a Hong Kong pro-democracy social-liberal political party catering to grassroots interest with a strong basis in Sham Shui Po. Established on 26 October 1986, it was one o ...

(HKADPL) began to participate in the local elections with the Hong Kong Affairs Society

The Hong Kong Affairs Society () was a middle class and professionals oriented political organisation formed in 1984 for the discussion for the Hong Kong prospect and political constitution after the handover to China with about 20 members led ...

(HKAS), and soon the three groups became the major forces of the pro-democratic camp in the late 1980s. The pro-democrats formed the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China

The Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China ( zh, link=no, t=香港市民支援愛國民主運動聯合會; abbr. ; ) was a pro-democracy organisation that was established on 21 May 1989 in the then British col ...

(HKASPDMC), led by president of the Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union

The Hong Kong Professional Teachers' Union (HKPTU) was a pro-democracy trade union, professional association and social concern group in Hong Kong. Until its disbandment in 2021, it was the largest teachers' organisation in Hong Kong with s ...

(HKPTU) and former Communist Szeto Wah

Szeto Wah (; 28 February 1931 – 2 January 2011) was a prominent Hong Kong democracy activist and politician. He was the founding chairman of the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China, the Hong Kong Profes ...

, who were in support of the student and labour movement in May 1989. They harshly condemned the bloody crackdown by the CCP regime on the morning of 4 June, which led to a longterm rupture of relations between Beijing and the majority of the pro-democratic camp.

The Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions

The Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU) was a pro-democracy labour and political group in the Hong Kong. It was established on 29 July 1990. It had 160,000 members in 61 affiliates (mainly trade unions in various sectors) and rep ...

(HKCTU), which emerged from the Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee

The Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee ( Chinese: 香港基督教工業委員會, also called as HKCIC) is a non-governmental pressure group that focuses on labor welfare policy and industrial safety. The group was founded in 1966, original ...

(HKCIC), became the major pro-democratic labour union in 1990. At the same year, the United Democrats of Hong Kong

The United Democrats of Hong Kong (; UDHK) was a short-lived political party in Hong Kong founded in 1990 as the united front of the liberal democracy forces in preparation of the 1991 first ever direct election for the Legislative Council of ...

(UDHK), which was later transformed into the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, was established as a grand alliance of pro-democratic politicians, professionals, activists and trade unionists. The pro-democratic camp won a landslide victory in the 1991 Hong Kong legislative election

The 1991 Hong Kong Legislative Council election was held for members of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong (LegCo). The election of the members of Functional constituency (Hong Kong), functional constituencies was held on 12 September 1991 and th ...

, and received an even larger majority in the 1995 Legislative Council election in the aftermath of the liberal 1994 Hong Kong electoral reform

File:1994 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The 1994 Winter Olympics are held in Lillehammer, Norway; The Kaiser Permanente building after the 1994 Northridge earthquake; A model of the MS Estonia, which sank in the Baltic Sea; Nelson Ma ...

.

Pro-Beijing leftists

To counter the growing influence of liberalism, theHong Kong Federation of Trade Unions

The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (HKFTU) is a pro-Beijing labour and political group established in 1948 in Hong Kong. It is the oldest and largest labour group in Hong Kong with over 420,000 members in 253 affiliates and associated ...

(HKFTU), which was the largest grassroots organisation in the traditional pro-Communist bloc, assumed a vanguard role to resist the pre-1997 democratisation. It joined hands with the conservative pro-business elites to oppose the direct Legislative Council election of 1988, using the slogan: "Hong Kong workers want meal tickets, not electoral ballots." However, during the Hong Kong Basic Law

The Basic Law of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China is a national law of China that serves as the organic law for the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Comprising nine chapters, 160 ...

drafting process from 1985 to 1990, the HKFTU had to repudiate its demands on the rights and recognition of trade unions and collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The i ...

in the Consultative and Drafting Committees, which were dominated by business tycoons. The HKFTU's devotion to Beijing and its collaboration with the conservative business interests of Hong Kong was criticised and challenged by several leftist union members.

In 1992, a pro-Beijing party named the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment of Hong Kong

The Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong (DAB) is a pro-Beijing conservative political party in Hong Kong. Chaired by Starry Lee and holding 13 Legislative Council seats, it is currently the largest party in the l ...

(DAB) was co-founded by HKFTU members. The HKFTU also began to mobilise supporters to vote for the DAB candidates in the subsequent Legislative Council elections. In 1997, the HKFTU representatives joined the Beijing-controlled Provisional Legislative Council

The Provisional Legislative Council (PLC) was the interim legislature of Hong Kong that operated from 1997 to 1998. The legislature was founded in Guangzhou and sat in Shenzhen from 1996 (with offices in Hong Kong) until the handover in 1997 an ...

, and rolled back several pre-handover legislation supporting labour rights passed in the spring of 1997 by the colonial legislature controlled by the pro-democracy camp, which included the right to collective bargaining under the Employee's Rights to Representation, Consultation and Collective Bargaining Ordinance, introduced by the HKCTU's Lee Cheuk-yan

Lee Cheuk-yan (; born 12 February 1957 in Shanghai) is a Hong Kong politician and social activist. He was a member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong from 1995 to 2016, when he lost his seat. He represented the Kowloon West and the Manufac ...

. The Provisional Legislative Council also enacted new electoral rules to disenfranchise 800,000 blue-collar, grey-collar, and white-collar workers in the nine functional constituencies created from Chris Patten

Christopher Francis Patten, Baron Patten of Barnes, (; born 12 May 1944) is a British politician who was the 28th and last Governor of Hong Kong from 1992 to 1997 and Chairman of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1992. He was made a life pe ...

's electoral reforms. The number of eligible voters in the Labour functional constituency was reduced from 2,001 qualified union officials in 1995 to only 361 unionists on a one-vote-per-union basis for the first post-handover elections in 1998.

Since 1997

The Young Turks

In the first years of the post-handover period, theDemocratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, which was the largest pro-democratic party, suffered severe intra-party struggles, as the left-wing Young Turks faction led by Andrew To

Andrew To Kwan-hang (; born 7 February 1966) is a Hong Kong politician and activist. He is the former chairman of the League of Social Democrats and former member of the Wong Tai Sin District Council.

Early life, education and student activis ...

challenged the conservative centrist leadership. During the Democratic Party's leadership election, the Young Turks nominated Lau Chin-shek

Lau Chin-shek (born 12 September 1944 in Guangzhou, Guangdong with family root in Shunde, Guangdong) is the President of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions and a vice Chairman of the Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee. He was born ...

, the General Secretary of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions

The Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU) was a pro-democracy labour and political group in the Hong Kong. It was established on 29 July 1990. It had 160,000 members in 61 affiliates (mainly trade unions in various sectors) and rep ...

(HKCTU), to run for the position of Vice-Chairman against Anthony Cheung

Anthony or Antony is a masculine given name, derived from the ''Antonii'', a ''gens'' ( Roman family name) to which Mark Antony (''Marcus Antonius'') belonged. According to Plutarch, the Antonii gens were Heracleidae, being descendants of Anton, ...

. In a general meeting held in September 1999, the Young Turks also proposed to put minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. Bec ...

legislation on the 2000 LegCo election platform of the party, which led to the backlash from the party's leadership. After failing to exert sufficient influence upon the party, the Young Turks formed another political group called the Social Democratic Forum

The Social Democratic Forum (, SDF) was a short-lived political group in Hong Kong formed by the radical faction of the Democratic Party. It consisted mostly the "Young Turks" faction of the Democratic Party which took a more pro-grassroots and str ...

, and later defected to the more radical Frontier

A frontier is the political and geographical area near or beyond a boundary. A frontier can also be referred to as a "front". The term came from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"—the region of a country that fronts o ...

.

League of Social Democrats

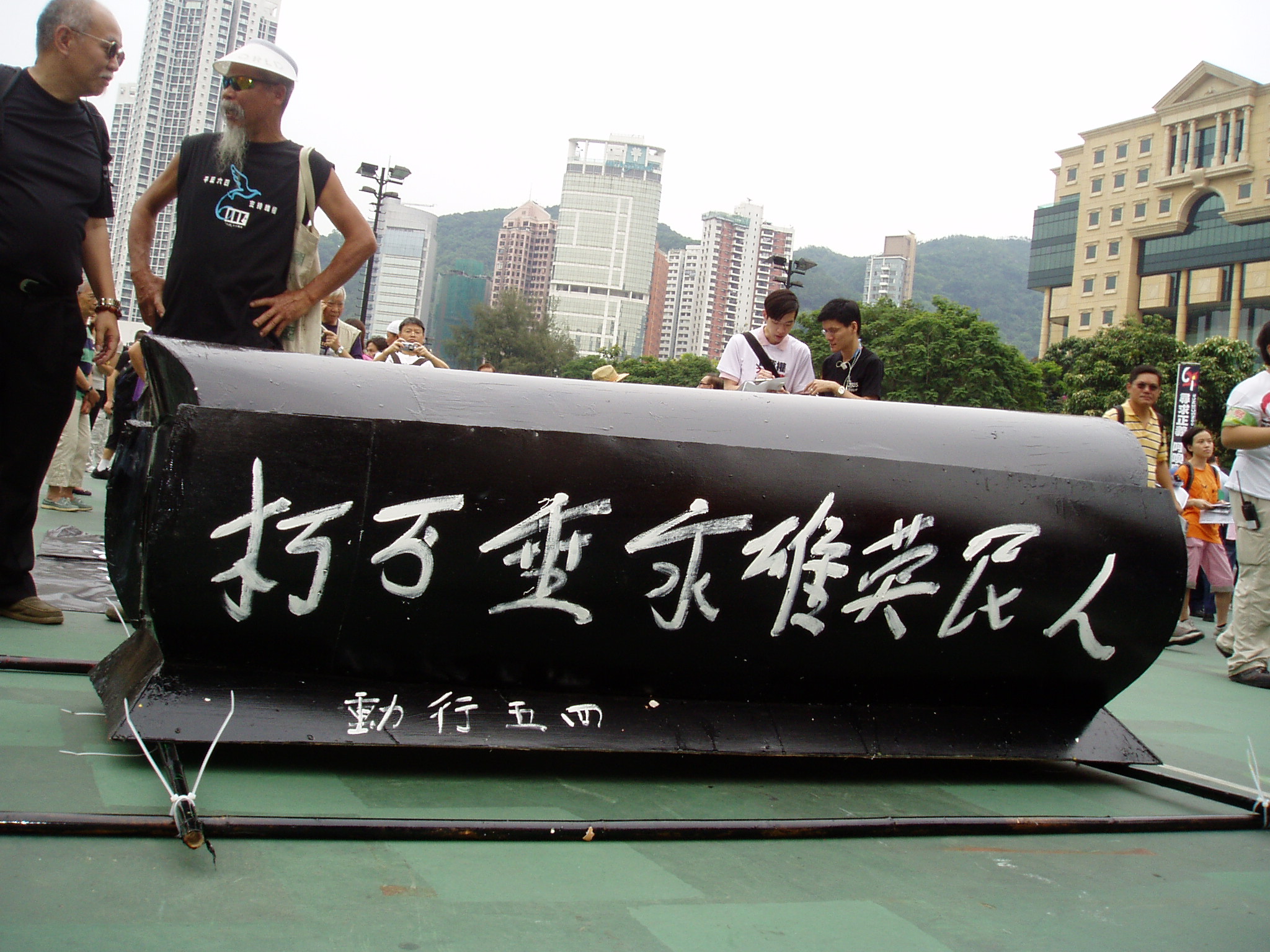

In October 2006, Andrew To, legislator

In October 2006, Andrew To, legislator Leung Kwok-hung

Leung Kwok-hung ( zh, t=梁國雄; born 27 March 1956), also known by his nickname "Long Hair" (), is a Hong Kong politician and social activist. He was a member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, Legislative Council, representing the N ...

of the April Fifth Action

April Fifth Action () is a Hong Kong left-wing group named after the first Tiananmen incident of 5 April 1976. While the organization's Chinese name translates as "April Fifth Action", English-language media in Hong Kong usually refer to it as th ...

, legislator and former Democratic Party member Albert Chan

Albert Chan Wai-yip (born 3 March 1955, Hong Kong) is a former member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong representing the New Territories West constituency. He has served as a legislator from 1991 to 2016 except for the periods 1997–2 ...

and the radical radio host named Wong Yuk-man

Raymond Wong Yuk-man (; born 1 October 1951) is a Hong Kong communist, pro-china, author, current affairs commentator and radio host. He is a former member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong (LegCo), representing the geographical constitue ...

founded the League of Social Democrats

The League of Social Democrats (LSD) is a social democratic party in Hong Kong. Chaired by Chan Po-ying, wife of Leung Kwok-hung, it positions itself as the radical wing of the pro-democracy camp (Hong Kong), pro-democracy camp and stresses on ...

(LSD), the first self-proclaimed leftist and social democratic party in Hong Kong. The League managed to win three seats in the 2008 Legislative Council election, receiving 10 percent of the popular vote.

In 2010, the League launched the "Five Constituencies Referendum

The 2010 Hong Kong Legislative Council by-election was an election held on 16 May 2010 in Hong Kong for all five geographical constituencies of the Legislative Council (LegCo), triggered by the resignation of five pan-democrat Legislative Counc ...

" movement, triggering a territory-wide by-election by having five legislators resign from the Legislative Council in each constituency in order to pressure the government to implement universal suffrage

Universal suffrage (also called universal franchise, general suffrage, and common suffrage of the common man) gives the right to vote to all adult citizens, regardless of wealth, income, gender, social status, race, ethnicity, or political stanc ...

. The purpose of the by-election as a referendum expectedly was heavily criticised by Beijing and Hong Kong's pro-Beijing camp as unconstitutional. The Democratic Party refused to join the movement and sought for a less confrontational way to negotiate with Beijing. The movement was considered as a failure, with only 17.7 percent of the registered voters casting their votes even though all three League legislators have successfully returned to the LegCo.

In 2011, the party was heavily devastated from intra-party struggles as former chairman Wong Yuk-man disagreed with the policies of the incumbent chairman Andrew To, including his diplomacy with the Democratic Party, which reached an agreement with the Chinese Communist authorities over the electoral reform proposals. On 24 January 2011, two of the three legislators of the party, Wong Yuk-man and Albert Chan, quit the LSD along with many of the League's leading figures, citing disagreement with leader Andrew To and his faction as their reasons for their departure. About 200 of their supporters joined them, leaving the LSD in complete disarray. Wong and Chan formed the People Power

"People Power" is a political term denoting the populist driving force of any social movement which invokes the authority of grassroots opinion and willpower, usually in opposition to that of conventionally organised corporate or political for ...

with other defected members and radical groups which left the League only one seat in the legislature, occupied by Leung Kwok-hung.

In the 2011 District Council election, the party lost all its seats in the District Councils to pro-Beijing candidates. During the following elections in 2015, the party along with a small Trotskyist group Socialist Action failed to win any seat.

In the 2016 Legislative Council election the League formed an electoral alliance with the People Power movement to boost the chance of their candidates, after witnessing the rise of localism in Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, localism is a political movement centered on the preservation of the city's autonomy and local culture. The Hong Kong localist movement encompasses a variety of groups with different goals, but all of them oppose the perceived grow ...

. The alliance won two seats in the New Territories East constituency, which was taken by two incumbents, Leung Kwok-hung and Chan Chi-chuen

Raymond Chan Chi-chuen (born 16 April 1972 in Hong Kong, ), also called Slow Beat () in his radio career, is a former member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong (representing the New Territories East constituency), presenter and former c ...

. Leung was later unseated in 2017 by the courts in a wave of disqualifications of the legislators over their oath-taking manners, which saw the League being ousted from all elected offices.

Left 21

A small socialist group by the name of Left 21 emerged after the failure of the massive anti-Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong Express Rail Link

Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong Express Rail Link (XRL), also known as “Guangshengang XRL” (officially Beijing–Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong high-speed railway, Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong section), is a high-speed railway line tha ...

(XRL) protest movement, as the leftist faction criticised the lack of class discourse in the movement's leadership. It started a year-long Occupy Central protest as part of the international Occupy movement

The Occupy movement was an international populist socio-political movement that expressed opposition to social and economic inequality and to the perceived lack of "real democracy" around the world. It aimed primarily to advance social and econo ...

, commencing the protest at a plaza beneath the HSBC headquarters from 2011 to 2012. It also joined the 40-day 2013 Hong Kong dock strike

The 2013 Hong Kong dock strike was a 40-day labour strike at the Kwai Tsing Container Terminal. It was called by the Union of Hong Kong Dockers (UHKD), an affiliate of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU) on 28 March 2013, again ...

at the Kwai Tsing Container Terminal

Kwai Tsing Container Terminals is the main port facilities in the reclamation along Rambler Channel between Kwai Chung and Tsing Yi Island, Hong Kong. It evolved from four berths of Kwai Chung Container Port () completed in the 1970s. It later ...

called by the Union of Hong Kong Dockers (UHKD), an affiliate of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions

The Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU) was a pro-democracy labour and political group in the Hong Kong. It was established on 29 July 1990. It had 160,000 members in 61 affiliates (mainly trade unions in various sectors) and rep ...

(HKCTU). It became the longest running industrial strike in Hong Kong in years.

Labour Party

In 2011, four incumbent legislators,Lee Cheuk-yan

Lee Cheuk-yan (; born 12 February 1957 in Shanghai) is a Hong Kong politician and social activist. He was a member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong from 1995 to 2016, when he lost his seat. He represented the Kowloon West and the Manufac ...

of the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions

The Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU) was a pro-democracy labour and political group in the Hong Kong. It was established on 29 July 1990. It had 160,000 members in 61 affiliates (mainly trade unions in various sectors) and rep ...

(HKCTU), Cyd Ho

Cyd Ho Sau-lan () is a former member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong (Legco) for the Hong Kong Island constituency.

She is a founding member of the Labour Party, since December 2011, and currently holds the position of vice-chairwoman ...

of the Civic Act-up

Civic Act-up () is a small pro-democracy political group in Hong Kong. It was founded on 24 September 2003 by a group of relatively young activists with the encouragement of Legislative Councillor Cyd Ho, to challenge the existing pro-government ...

and Cheung Kwok-che

Peter Cheung Kwok-che (born 8 November 1951, ) is a former member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong (Functional constituency, Social Welfare), with the Labour Party.Hong Kong Social Workers General Union

Hong Kong Social Workers' General Union (HKSWGU) is a trade union for the social workers in Hong Kong. It was established in 1980. The current president, Cheung Kwok-che is the member in the Legislative Council of Hong Kong. It is one of the trad ...

(HKSWGU), co-founded the Labour Party, whose core issues were labour rights, new immigrants, ethnic minorities and environmentalism, and the party has run in the 2012 Legislative Council election

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1 ...

. The Labour won four seats in the election, receiving four percent of the popular vote, becoming the third largest pro-democratic party after the liberal Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

and Civic Party

The Civic Party (CP) is a pro-democracy liberal political party in Hong Kong. It is currently chaired by barrister Alan Leong.