Socialism and LGBT rights on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The connection between

The first currents of modern socialist thought emerged in Europe in the early 19th century. They are now often described with the phrase

The first currents of modern socialist thought emerged in Europe in the early 19th century. They are now often described with the phrase

'' and this work producing such notions was in a piece named ''Oeuvres Completes'', its first volume published in 1841. This would also in turn promote some influence for future socialist thinkers who happen to be a part of pro-LGBT movements across the world.

Known to both Ulrichs and Marx was the case of Jean Baptista von Schweitzer, an important labor organizer who had been charged with attempting to solicit a teenage boy in a park in 1862. Social democratic leader Ferdinand Lassalle defended Schweitzer on the grounds that while he personally found homosexuality to be dirty, the labor movement needed the leadership of Schweitzer too much to abandon him, and that a person's sexual tastes had "absolutely nothing to do with a man's political character". Marx, on the other hand, suggested that Engels use this incident to smear Schweitzer: "You must arrange for a few jokes about him to reach Siebel, for him to hawk around to the various papers." However, Schweitzer would go on to become President of the German Labor Union, and the first Social Democrat elected to a parliament in Europe.

August Bebel's ''Woman under Socialism'' (1879), the "single work dealing with sexuality most widely read by rank-and-file members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD)", can be seen as another example of the ambiguous position towards homosexuality in the German labor movement. On the one hand, Bebel warned socialists of the dangers of same-sex love. Bebel attributed "this crime against nature" in both men and women to sexual indulgence and excess, describing it as an upper-class, metropolitan and foreign vice. On the other hand, he did publicly support the efforts to legalize homosexuality. For example, he signed the first petition of the "Wissenschaftlich-humanitärer Kreis", a study group led by Magnus Hirschfeld, trying to explain homosexuality from a scientific point of view and pushing for decriminalization. In an article for Gay News in 1978, John Lauritsen considers August Bebel as the first important politician "to speak out in public debate" in the favor of gay rights since he attacked the criminalization of homosexuality in a Reichstag debate in 1898.

The leading figure of the LGBT movement in

In Oscar Wilde's '' The Soul of Man Under Socialism'', he advocates for an

In Oscar Wilde's '' The Soul of Man Under Socialism'', he advocates for an

/ref> He later commented, "I think I am rather more than a Socialist. I am something of an Anarchist, I believe." "In August 1894, Wilde wrote to his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, to tell of "a dangerous adventure." He had gone out sailing with two lovely boys, Stephen and Alphonso, and they were caught in a storm. "We took five hours in an awful gale to come back! nd wedid not reach pier till eleven o'clock at night, pitch dark all the way, and a fearful sea. ... All the fishermen were waiting for us."...Tired, cold, and "wet to the skin," the three men immediately "flew to the hotel for hot brandy and water." But there was a problem. The law stood in the way: "As it was past ten o'clock on a Sunday night the proprietor could not sell us any brandy or spirits of any kind! So he had to give it to us. The result was not displeasing, but what laws!"...Wilde finishes the story: "Both Alphonso and Stephen are now anarchists, I need hardly say."" In the earlier days of England men were being arrested for passing as members of the opposite sex and were widely stigmatized for cross-dressing because they were thought to be prostitutes. A certain case pertaining to this would be one in the year 1870 when Frederick Park (Fanny) and Ernest Boulton (Stella) were arrested for being men in women's clothing and framed for committing crimes. One of the earliest places of LGBT persuasions or gatherings would be a place in north

online e-book

/ref> In April 1914, Carpenter and his friend Laurence Houseman founded the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology. Some of the topics addressed in lecture and publication by the society included: the promotion of the scientific study of sex; a more rational attitude towards sexual conduct and problems and questions connected with sexual psychology (from medical, juridical, and sociological aspects), birth control, abortion, sterilization, venereal diseases, and all aspects of prostitution.

Senna Hoy

: "an adherent of free love, oycelebrated homosexuality as a 'champion of culture' and engaged in the struggle against

Senna Hoy

: "an adherent of free love, oycelebrated homosexuality as a 'champion of culture' and engaged in the struggle against

In 1951, the

In 1951, the

During the emergence of the

During the emergence of the  In the United Kingdom, the 1980s saw increased

In the United Kingdom, the 1980s saw increased Lesbian and Gay Liberation: A Trotskyist Analysis

As the gay liberation movement began to gain ground, socialist organizations' policies evolved, and many groups actively campaigned for gay rights. Notable examples are the feminist

online text

* ''Marxist Theory of Homosexuality'' 1993

* ''Homosexual Existence and Existing Socialism New Light on the Repression of Male Homosexuality in Stalin's Russia'' By Dan Healey. 2002. GLQ 8:3, pp. 349 – 378. * ''Sex-Life: A Critical Commentary on the History of Sexuality'', 1993, Don Milligan

* Terence Kissack

''Free Comrades: Anarchism and Homosexuality in the United States''

''Gay Left''

entry in GLBTQ encyclopedia online. *

Gay Left

', a 1970s socialist journal. {{LGBT rights footer LGBT history LGBT rights LGBT and society

left-leaning

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

ideologies and LGBT rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender ( LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, ...

struggles has a long and mixed history. Prominent socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

who were involved in early struggles for LGBT rights include Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rightsWarren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Human ...

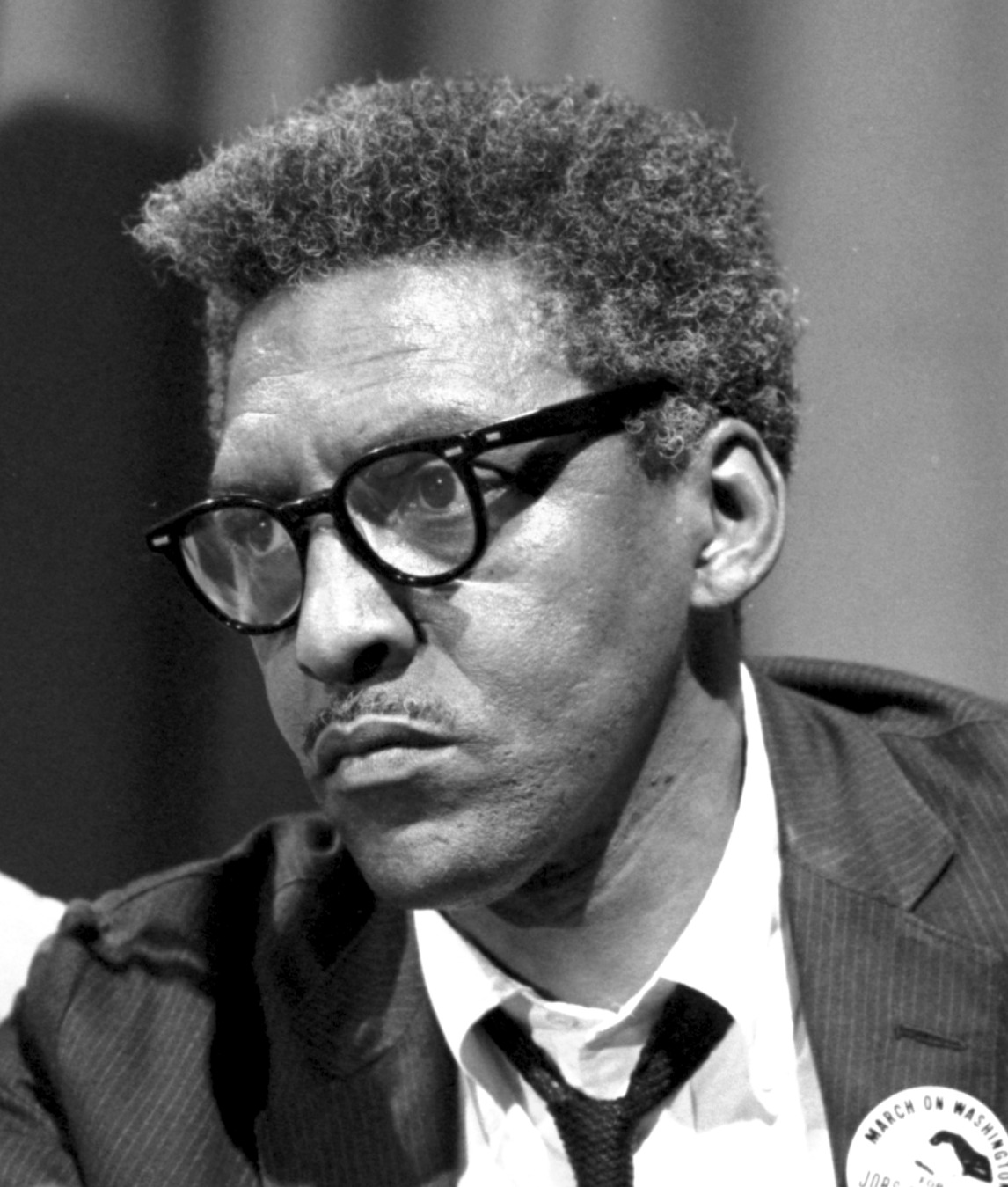

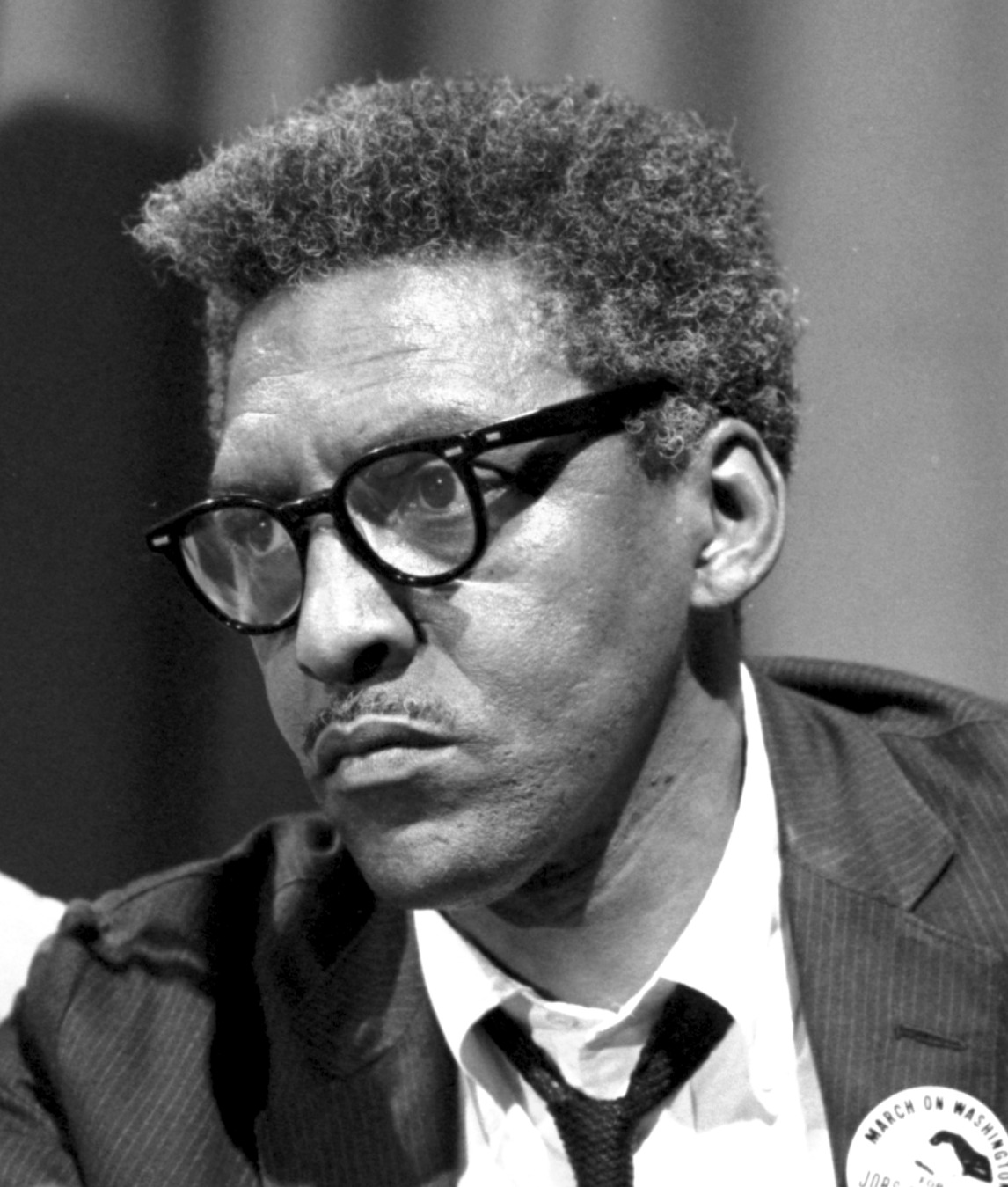

, Oscar Wilde, Harry Hay, Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (; March 17, 1912 – August 24, 1987) was an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

Rustin worked with A. Philip Randolph on the March on Washington Movement, ...

, Emma Goldman and Daniel Guérin

Daniel Guérin (; 19 May 1904, in Paris – 14 April 1988, in Suresnes) was a French libertarian-communist author, best known for his work '' Anarchism: From Theory to Practice'', as well as his collection ''No Gods No Masters: An Anthology of ...

, among others.

Scientific and utopian socialism

The first currents of modern socialist thought emerged in Europe in the early 19th century. They are now often described with the phrase

The first currents of modern socialist thought emerged in Europe in the early 19th century. They are now often described with the phrase utopian socialism

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

. Gender and sexuality were significant concerns for many of the leading thinkers such as Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

and Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

in France and Robert Owen in Britain as well as their followers, many of whom were women. For Fourier, for example, true freedom could only occur without masters, without the ethos of work, and without suppressing passions; the suppression of passions is not only destructive to the individual, but to society as a whole. Writing before the advent of the term 'homosexuality', Fourier recognized that both men and women have a wide range of sexual needs and preferences which may change throughout their lives, including same-sex sexuality and ''androgénité''. He argued that all sexual expressions should be enjoyed as long as people are not abused, and that "affirming one's difference" can actually enhance social integration.

Alongside other prominent thinkers at the time, Fourier believed scientific understanding to be a standard of any society to live up to. Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim ( or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science, al ...

is known for being one of the first people to provide the idea of having to understand utopian socialism with the rise of social sciences. However, through further evaluation of these thinkings Fourier and Saint-Simon were not seen as heads of the emerging scientific socialist movement. With integration of scientific thought into a social perspective, there would be further discourse within the topics of family, education and especially sexuality. Fourier in particular had a doctrine specifically detailing complexities surrounding the full expression of human passions. The doctrine that Fourier expresses some of these views is known in French as ''Nouveau monde amoureux'', which means New World in Love. The ideas expressed by early utopian socialists would help influence many woman to become a part of the movement and were quite instrumental towards the emergence of the feminist movement. The idea of social reshaping was matching the thinking of utopian socialism. In fact, the reemergence of Fouriers works in the 1960s would contribute further to the rising movements of feminism and LGBT because of interest in sexual liberties. Durkheim was known to show concern through a more scientific approach rather than a political one. He was also very adamant about the significance of the study of Sociology as it was believed to shape the humanist subjects of philosophy, history and psychology. Durkheim is also known for establishing '' L'Année Sociologique'', which is the first journal of social science in France in 1898.

Germany

From the earliest European homosexual rights movements, activists such asKarl Heinrich Ulrichs

Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (28 August 1825 – 14 July 1895) was a German lawyer, jurist, journalist, and writer who is regarded today as a pioneer of sexology and the modern gay rights movement. Ulrichs has been described as the "first gay man in ...

and Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a German physician and sexologist.

Hirschfeld was educated in philosophy, philology and medicine. An outspoken advocate for sexual minorities, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Com ...

approached the Left for support. During the 1860s, Ulrichs wrote to Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and sent him a number of books on Uranian (homosexual/transgender) emancipation, and in 1869 Marx passed one of Ulrichs' books on to Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Charles Fourier François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

that had immense influence among social thinkers in France. Fourier had also previously published writings specifying his stance on families and the favoring of replacing monogamous marriages in order to suit what Fourier called a "Greater latitude of sexual passions'' Charles Fourier François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

from the turn of the 20th century until the Nazi government

The government of Nazi Germany was totalitarian, run by the Nazi Party in Germany according to the Führerprinzip through the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler. Nazi Germany began with the fact that the Enabling Act was enacted to give Hitler's gover ...

came to power in 1933 was undoubtedly Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a German physician and sexologist.

Hirschfeld was educated in philosophy, philology and medicine. An outspoken advocate for sexual minorities, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Com ...

. Hirschfeld, who was also a socialist and supporter of the Women's Movement

The feminist movement (also known as the women's movement, or feminism) refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such is ...

, formed the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee

The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (, WhK) was founded by Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin in May 1897, to campaign for social recognition of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and against their legal persecution. It was the fir ...

to campaign against German Penal Code Section 175 which outlawed male-male sex. Hirschfeld's organization did a deal with the SPD (of which Lassalle and Schweitzer had been members) to get them to put forward a bill in the Reichstag in 1898, but it was opposed in the Reichstag and failed to pass. Most of Hirschfeld's circle of homosexual activists had socialist politics, including Kurt Hiller, Richard Linsert, Johanna Elberskirchen and Bruno Vogel. After the toppling of the German monarchy, the struggle against § 175 was continued by some social democrats. The German Minister of Justice Gustav Radbruch, member of the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

, tried to erase the paragraph from the German penal law. However, his efforts were to no avail. Also, some Queer cinema began to emerge to show what life for a gay individual was like in West Germany. These characters are also distrustful of Bourgeoisie but hold these feelings of sexual nature dearly. The use of this piece of cinema in the 70's proved to be effective through influential advertisement of ideas. It was actually after these films took place in 1971 that the first gay rights organization was formed in west Berlin. While there was still separation of eastern and western sides of Berlin, the east has proven to be much more lenient on the matter of gay rights. This comes with major reforms through legislation and repealing of Nazi-era anti-sodomy laws.

Britain

In Oscar Wilde's '' The Soul of Man Under Socialism'', he advocates for an

In Oscar Wilde's '' The Soul of Man Under Socialism'', he advocates for an egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

society where wealth is shared by all, while warning of the dangers of authoritarian socialism that would crush individuality.Kristian Williams. "The Soul of Man Under... Anarchism?"/ref> He later commented, "I think I am rather more than a Socialist. I am something of an Anarchist, I believe." "In August 1894, Wilde wrote to his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, to tell of "a dangerous adventure." He had gone out sailing with two lovely boys, Stephen and Alphonso, and they were caught in a storm. "We took five hours in an awful gale to come back! nd wedid not reach pier till eleven o'clock at night, pitch dark all the way, and a fearful sea. ... All the fishermen were waiting for us."...Tired, cold, and "wet to the skin," the three men immediately "flew to the hotel for hot brandy and water." But there was a problem. The law stood in the way: "As it was past ten o'clock on a Sunday night the proprietor could not sell us any brandy or spirits of any kind! So he had to give it to us. The result was not displeasing, but what laws!"...Wilde finishes the story: "Both Alphonso and Stephen are now anarchists, I need hardly say."" In the earlier days of England men were being arrested for passing as members of the opposite sex and were widely stigmatized for cross-dressing because they were thought to be prostitutes. A certain case pertaining to this would be one in the year 1870 when Frederick Park (Fanny) and Ernest Boulton (Stella) were arrested for being men in women's clothing and framed for committing crimes. One of the earliest places of LGBT persuasions or gatherings would be a place in north

Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

called Cataractonium

Cataractonium was a fort and settlement in Roman Britain. The settlement evolved into Catterick, located in North Yorkshire, England.

Name

Cataractonium likely took its name form the Latin word (ultimately derived from Greek , ), meaning eit ...

and has presented a grave sight discovered by Archeologists. It is said that this grave is dated back to 4 BC and was known as a male that had apparently self-castrated and committed to cross dressing to please a priestess/goddess by the name of Cybele

Cybele ( ; Phrygian language, Phrygian: ''Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya'' "Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother", perhaps "Mountain Mother"; Lydian language, Lydian ''Kuvava''; el, Κυβέλη ''Kybele'', ''Kybebe'', ''Kybelis'') is an Anatolian mother godde ...

. This was the ritual expected from a Roman Gallus at the time. Another instance had occurred in London around 1395 when a young man named John Rykener had been arrested for having sexual relations dressed as a woman. John would be accused of committing the unspeakable of that time. When speaking to the authorities John had specified how he would prostitute as a man in women's clothes. This would be a significant instance in which gender nonconformity was happening in medieval times of England.

Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rightsWarren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Human ...

was a leading figure in late 19th- and early 20th-century Britain being instrumental in the foundation of the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

and the Labour Party. The 1890s saw Carpenter in a concerted effort to campaign against discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation

Sexual orientation is an enduring pattern of romantic or sexual attraction (or a combination of these) to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. These attractions are generall ...

. He strongly believed that same-sex attraction was a natural orientation for people of a third sex

Third gender is a concept in which individuals are categorized, either by themselves or by society, as neither man nor woman. It is also a social category present in societies that recognize three or more genders. The term ''third'' is usually ...

. His 1908 book on the subject, ''The Intermediate Sex

''The Intermediate Sex'' (full title: ''The Intermediate Sex: A Study of Some Transitional Types of Men and Women'') was a 1908 work by Edward Carpenter expressing his views on homosexuality. Carpenter argues that "uranism", as he terms homosexua ...

'', would become a foundational text of the LGBT movements

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) movements are social movements that advocate for LGBT people in society. Some focus on equal rights, such as the ongoing movement for same-sex marriage, while others focus on liberation, as in the ...

of the 20th century. ''The Intermediate Sex: A Study of Some Transitional Types of Men and Women'' expressed his views on homosexuality. Carpenter argues that "uranism", as he terms homosexuality, was on the increase marking a new age of sexual liberation. He continued to work in the early part of the 20th century composing works on the "Homogenic question". The publication in 1902 of his groundbreaking anthology of poems, '' Ioläus: An Anthology of Friendship'', was a huge underground success, leading to a more advanced knowledge of homoerotic

Homoeroticism is sexual attraction between members of the same sex, either male–male or female–female. The concept differs from the concept of homosexuality: it refers specifically to the desire itself, which can be temporary, whereas "homose ...

culture.The 1917 New York edition is now available as a freonline e-book

/ref> In April 1914, Carpenter and his friend Laurence Houseman founded the British Society for the Study of Sex Psychology. Some of the topics addressed in lecture and publication by the society included: the promotion of the scientific study of sex; a more rational attitude towards sexual conduct and problems and questions connected with sexual psychology (from medical, juridical, and sociological aspects), birth control, abortion, sterilization, venereal diseases, and all aspects of prostitution.

Anarchism, libertarian socialism and LGBT rights

In Europe and North America, thefree love movement

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern of ...

combined ideas revived from utopian socialism with anarchism and feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

to attack the "hypocritical" sexual morality of the Victorian era, and the institutions of marriage and the family that were alleged to enslave women. Free lovers advocated voluntary sexual unions with no state interference and affirmed the right to sexual pleasure for both women and men, sometimes explicitly supporting the rights of homosexuals and prostitutes. For a few decades, adherence to "free love" became widespread among European and American anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, but these views were opposed at the time by Marxists and social democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

. Radical feminist and socialist Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Claflin Woodhull, later Victoria Woodhull Martin (September 23, 1838 – June 9, 1927), was an American leader of the women's suffrage movement who ran for President of the United States in the 1872 election. While many historians ...

was expelled from the International Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

in 1871 for her involvement in the free love and associated movements.Messer-Kruse, Timothy. 1998. ''The Yankee International: 1848-1876''. (University of North Carolina) Indeed, with Marx's support, the American branch of the organization was purged of its pacifist, anti-racist

Anti-racism encompasses a range of ideas and political actions which are meant to counter racial prejudice, systemic racism, and the oppression of specific racial groups. Anti-racism is usually structured around conscious efforts and deliberate ...

and feminist elements, which were accused of putting too much emphasis on issues unrelated to class struggle and were therefore seen to be incompatible with scientific socialism

Scientific socialism is a term coined in 1840 by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his book '' What is Property?'' to mean a society ruled by a scientific government, i.e., one whose sovereignty rests upon reason, rather than sheer will: Thus, in a given ...

.

The ''Verband Fortschrittlicher Frauenvereine'' (League of Progressive Women's Associations), a turn of the 20th century left-wing organization led by Lily Braun

Lily Braun (2 July 1865 – 8 August 1916), born Amalie von Kretschmann, was a German feminist writer and politician of the Social Democratic Party (SPD).

Life

She was born in Halberstadt, in the Prussian province of Saxony, the daught ...

campaigned for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Germany and aimed at organizing prostitutes

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

into labour unions. The broader labour movement either attacked the League, saying they were utopians, or ignored it, and Braun was driven out of the international Marxist movement. Helene Stöcker

Helene Stöcker (13 November 1869 – 24 February 1943) was a German feminist, pacifist and gender activist. She successfully campaigned keep same sex relationships between women legal, but she was unsuccessful in her campaign to legalise aborti ...

, another German activist from the left wing of the women's movement, became heavily involved in the sexual reform movement in 1919, after World War I, and served on the board of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

The was an early private sexology research institute in Germany from 1919 to 1933. The name is variously translated as ''Institute of Sex Research'', ''Institute of Sexology'', ''Institute for Sexology'' or ''Institute for the Science of Sexua ...

. She also campaigned to protect single mothers and their children from economic and moral persecution. Anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

writer Ulrich Linse wrote about "a sharply outlined figure of the Berlin individualist anarchist cultural scene around 1900", the "precocious Johannes Holzmann" (known aSenna Hoy

: "an adherent of free love, oycelebrated homosexuality as a 'champion of culture' and engaged in the struggle against

Paragraph 175

Paragraph 175 (known formally a§175 StGB also known as Section 175 in English) was a provision of the German Criminal Code from 15 May 1871 to 10 March 1994. It made homosexual acts between males a crime, and in early revisions the provisio ...

."Linse, Ulrich, ''Individualanarchisten, Syndikalisten, Bohémiens,'' in "Berlin um 1900", ed. Gelsine Asmus (Berlin: Berlinische Galerie, 1984) The young Hoy (born 1882) published these views in his weekly magazine (, in English "Struggle") from 1904, which reached a circulation of 10,000 the following year. German anarchist psychotherapist Otto Gross

Otto Hans Adolf Gross (17 March 1877 – 13 February 1920) was an Austrian psychoanalyst. A maverick early disciple of Sigmund Freud, he later became an anarchist and joined the utopian Ascona community.

His father Hans Gross was a judge turned ...

also wrote extensively about same-sex sexuality in both men and women and argued against its discrimination. Heterosexual

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" ...

anarchist Robert Reitzel (1849–1898) spoke positively of homosexuality from the beginning of the 1890s in his German-language journal " Der arme Teufel" (Detroit).

Across the Atlantic, in New York's Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

, Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

feminists and socialists advocated self-realization and pleasure for women (and also men) in the here and now, as well as campaigning against the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and for other anarchist and socialist causes. They encouraged playing with sexual roles and sexuality, and the openly bisexual radical Edna St. Vincent Millay

Edna St. Vincent Millay (February 22, 1892 – October 19, 1950) was an American lyrical poet and playwright. Millay was a renowned social figure and noted feminist in New York City during the Roaring Twenties and beyond. She wrote much of he ...

and the lesbian anarchist Margaret Anderson were prominent among them. The Villagers took their inspiration from the mostly anarchist immigrant female workers from the period 1905–1915 and the " New Life Socialism" of Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rightsWarren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Human ...

, Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality i ...

and Olive Schreiner

Olive Schreiner (24 March 1855 – 11 December 1920) was a South African author, anti-war campaigner and intellectual. She is best remembered today for her novel ''The Story of an African Farm'' (1883), which has been highly acclaimed. It deal ...

. Discussion groups organized by the Villagers were frequented by the Russian anarchist Emma Goldman, among others. Magnus Hirschfeld noted in 1923 that Goldman "has campaigned boldly and steadfastly for individual rights, and especially for those deprived of their rights. Thus it came about that she was the first and only woman, indeed the first and only American, to take up the defense of homosexual love before the general public." In fact, prior to Goldman, heterosexual anarchist Robert Reitzel (1849–98) spoke positively of homosexuality from the beginning of the 1890s in his German-language journal " Der arme Teufel" (Detroit). During her life, Goldman was lionized as a free-thinking "rebel woman" by admirers, and derided by critics as an advocate of politically motivated murder and violent revolution. Her writing and lectures spanned a wide variety of issues, including prisons, atheism, freedom of speech, militarism, capitalism, marriage, free love, and homosexuality. Although she distanced herself from first-wave feminism and its efforts toward women's suffrage, she developed new ways of incorporating gender politics into anarchism. After decades of obscurity, Goldman's iconic status was revived in the 1970s, when feminist and anarchist scholars rekindled popular interest in her life.

Mujeres Libres

Mujeres Libres ( en, Free Women, italic=yes) was an anarchist women's organisation that existed in Spain from 1936 to 1939. Founded by Lucía Sánchez Saornil, Mercedes Comaposada, and Amparo Poch y Gascón as a small women's group in Madrid, it ...

was an anarchist women's organization in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

that aimed to empower working-class women. It was founded in 1936 by Lucía Sánchez Saornil

Lucía Sánchez Saornil (1895–1970), was a lesbian Spanish poet, militant anarchist and feminist. She is best known as one of the founders (alongside Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch Y Gascón) of ''Mujeres Libres'' and served in the Conf ...

, Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch y Gascón

Amparo Poch y Gascón (15 October 1902 – 15 April 1968) was a Spanish anarchist,

pacifist, doctor, and activist in the years leading up to and during the Spanish Civil War.

Poch y Gascón was born in Zaragoza.Lola Campos, ''Mujeres aragones ...

and had approximately 30,000 members. The organization was based on the idea of a "double struggle" for women's liberation

The women's liberation movement (WLM) was a political alignment of women and feminist intellectualism that emerged in the late 1960s and continued into the 1980s primarily in the industrialized nations of the Western world, which effected great ...

and social revolution and argued that the two objectives were equally important and should be pursued in parallel. In order to gain mutual support, they created networks of women anarchists. Flying day-care centres were set up in efforts to involve more women in union activities. Lucía Sánchez Saornil

Lucía Sánchez Saornil (1895–1970), was a lesbian Spanish poet, militant anarchist and feminist. She is best known as one of the founders (alongside Mercedes Comaposada and Amparo Poch Y Gascón) of ''Mujeres Libres'' and served in the Conf ...

was a Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

poet, militant anarchist and feminist. She is best known as one of the founders of ''Mujeres Libres

Mujeres Libres ( en, Free Women, italic=yes) was an anarchist women's organisation that existed in Spain from 1936 to 1939. Founded by Lucía Sánchez Saornil, Mercedes Comaposada, and Amparo Poch y Gascón as a small women's group in Madrid, it ...

'' and served in the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo ( en, National Confederation of Labor; CNT) is a Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionar ...

(CNT) and Solidaridad Internacional Antifascista (SIA). By 1919, she had been published in a variety of journals, including ''Los Quijotes'', ''Tableros'', ''Plural'', ''Manantial'' and ''La Gaceta Literaria''. Working under a male pen name, she was able to explore lesbian themes at a time when homosexuality was criminalized and subject to censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

and punishment. Writing in anarchist publications such as ''Earth and Freedom'', the ''White Magazine'' and '' Workers' Solidarity'', Lucía outlined her perspective as a feminist. Although quiet on the subject of birth control, she attacked the essentialism of gender roles

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cent ...

in Spanish society. In this way, Lucía established herself as one of the most radical of voices among anarchist women, rejecting the ideal of female domesticity which remained largely unquestioned. In a series of articles for ''Workers' Solidarity'', she boldly refuted Gregorio Marañón

Gregorio Marañón y Posadillo, OWL (19 May 1887 in Madrid – 27 March 1960 in Madrid) was a Spanish physician, scientist, historian, writer and philosopher. He married Dolores Moya in 1911, and they had four children (Carmen, Belén, María ...

's identification of motherhood

]

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of gesta ...

as the nucleus of female identity.

European gay anarchists

Anarchism's foregrounding of individual freedoms made for a natural marriage with homosexuality in the eyes of many, both inside and outside of the Anarchist movement.Emil Szittya

Emil Szittya is the name under which the originally Austria-Hungarian multi-faceted libertarian writer Adolf/Avraham Schenk (18 August 1886 - 26 November 1964) published his first book, and it is the name by which he was and is most frequently kno ...

, in ' (1923), wrote about homosexuality that "very many anarchists have this tendency. Thus I found in Paris a Hungarian anarchist, Alexander Sommi, who founded a homosexual anarchist group on the basis of this idea." His view is confirmed by Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a German physician and sexologist.

Hirschfeld was educated in philosophy, philology and medicine. An outspoken advocate for sexual minorities, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Com ...

in his 1914 book : "In the ranks of a relatively small party, the anarchist, it seemed to me as if proportionately more homosexuals and effeminates are found than in others." Italian anarchist Luigi Bertoni

Luigi Bertoni (1872–1947) was an Italian-born anarchist writer and typographer.

Bertoni fought on the Huesca front with Italian comrades during the Spanish Revolution and was, with Emma Goldman, one of the outspoken critics of anarchist ...

(who Szittya also believed to be gay) said that "Anarchists demand freedom in everything, thus also in sexuality. Homosexuality leads to a healthy sense of egoism, for which every anarchist should strive."

Anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence i ...

writer Ulrich Linse wrote about "a sharply outlined figure of the Berlin individualist anarchist cultural scene around 1900", the "precocious Johannes Holzmann" (known aSenna Hoy

: "an adherent of free love, oycelebrated homosexuality as a 'champion of culture' and engaged in the struggle against

Paragraph 175

Paragraph 175 (known formally a§175 StGB also known as Section 175 in English) was a provision of the German Criminal Code from 15 May 1871 to 10 March 1994. It made homosexual acts between males a crime, and in early revisions the provisio ...

." The young Hoy (born 1882) published these views in his weekly magazine, ''Kampf'', from 1904 which reached a circulation of 10,000 the following year. German anarchist psychotherapist Otto Gross

Otto Hans Adolf Gross (17 March 1877 – 13 February 1920) was an Austrian psychoanalyst. A maverick early disciple of Sigmund Freud, he later became an anarchist and joined the utopian Ascona community.

His father Hans Gross was a judge turned ...

also wrote extensively about same-sex sexuality in both men and women and argued against its discrimination. In the 1920s and 1930s, French individualist anarchist publisher Émile Armand

Émile Armand (26 March 1872 – 19 February 1962), pseudonym of Ernest-Lucien Juin Armand, was an influential French individualist anarchist at the beginning of the 20th century and also a dedicated free love/polyamory, intentional community, a ...

campaigned for acceptance of free love, including homosexuality, in his journal ''L'en dehors''.

The individualist anarchist Adolf Brand was originally a member of Hirschfeld's Scientific-Humanitarian committee

The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (, WhK) was founded by Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin in May 1897, to campaign for social recognition of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and against their legal persecution. It was the fir ...

, but formed a break-away group. Brand and his colleagues, known as the Gemeinschaft der Eigenen

The german: label=none, Gemeinschaft der Eigenen ("Community of Free Spirits") was a German homosexual advocacy group led by anarchist Adolf Brand. The group opposed the country's preeminent advocacy group, Magnus Hirschfeld's Scientific-Humanita ...

, were heavily influenced by homosexual anarchist John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay, also known by the pseudonym Sagitta, (6 February 1864 – 16 May 1933) was an egoist anarchist, thinker and writer. Born in Scotland and raised in Germany, Mackay was the author of '' Die Anarchisten'' (The Anarchists, 1891) a ...

. The group despised effeminacy and saw homosexuality as an expression of manly virility available to all men, espousing a form of nationalistic masculine ''Lieblingminne'' (chivalric love) that would later be linked to the rise of Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) i ...

. They were opposed to Hirschfeld's medical characterisation of homosexuality as the domain of an "intermediate sex". Brand "toyed with anti-Semitism", and disdained Hirschfeld on the grounds that he was Jewish. Ewald Tschek, another gay anarchist writer of the era, regularly contributed to Adolf Brand's journal ''Der Eigene'', and wrote in 1925 that Hirschfeld's Scientific Humanitarian Committee was a danger to the German people, caricaturing Hirschfeld as "Dr. Feldhirsch".

Anarchist homophobia

Whilst these pro-homosexual stances had begun to surface, many members of the anarchist movement of the time still believed that nature/a divine Creator had provided a perfect answer to human relationships; an editorial in an influential Spanish anarchist journal from 1935 argued that an Anarchist must even avoid any relationship with homosexuals: "If you are an anarchist, that means that you are more morally upright and physically strong than the average man. And he who likes inverts is no real man, and is therefore no real anarchist." However, despite that view, many present-day anarchists accept homosexuality.Homophile movement and socialism in the United States

McCarthyism in the US believed a "homosexual underground" was abetting the "communist conspiracy", which was sometimes called the Homintern. A number of homosexual rights groups came into being during this period. These groups, now known as the "homophile" movement, often had left-wing or socialist politics, such as the communist Mattachine Society and the Dutch COC which originated on the left. In the context of the highly politicized Cold War environment, homosexuality became framed as a dangerous, contagious social disease that posed a potential threat to state security.Gary Kinsman and Patrizia Gentile, ''The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation'' (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010), p. 65. This era also witnessed the establishment of widely spread FBI surveillance intended to identify homosexual government employees. Harry Hay, who is seen by many as the father of the modern gay rights movement in theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, was originally a trade union

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

activist. In 1934, he organized an important 83-day-long workers' strike of the port of San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17th ...

with his lover, actor Will Geer

Will Geer (born William Aughe Ghere; March 9, 1902 – April 22, 1978) was an American actor, musician, and social activist, who was active in labor organizing and other movements in New York and Southern California in the 1930s and 1940s. In Ca ...

. He was an active member of the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

. Hay and the Mattachine Society were among the first to argue that gay people were not just individuals but in fact represented a "cultural minority". They even called for public marches of homosexuals, predicting later gay pride parades. Hay's concept of the "cultural minority" came directly from his Marxist studies, and the rhetoric that he and his colleague Charles Rowland employed often reflected the militant Communist tradition. The Communist Party did not officially allow gays to be members, claiming that homosexuality was a 'deviation'; perhaps more important was the fear that a member's (usually secret) homosexuality would leave them open to blackmail and made them a security risk in an era of red-baiting. Concerned to save the party difficulties, as he put more energy into the Mattachine Society, Hay himself approached the CP's leaders and recommended his own expulsion. However, after much soul-searching, the CP, clearly reeling at the loss of a respected member and theoretician of 18 years' standing, refused to expel Hay as a homosexual, instead expelling him under the more convenient ruse of 'security risk', while ostentatiously announcing him to be a 'Lifelong Friend of the People'. The Mattachine Society was the second gay rights organization that Hay established, the first being Bachelors for Wallace'' (1948) in support of Henry Wallace's progressive presidential candidacy. The ''Encyclopedia of Homosexuality'' reports that "As Marxists the founders of the group believed that the injustice and oppression which they suffered stemmed from relationships deeply embedded in the structure of American society".

In 1951, the

In 1951, the Socialist Party USA

The Socialist Party USA, officially the Socialist Party of the United States of America,"The article of this organization shall be the Socialist Party of the United States of America, hereinafter called 'the Party'". Art. I of th"Constitution o ...

was close to adopting a platform plank in favor of gay rights, with one article in the Youth Socialist Party press supporting such a move. African American socialist and civil rights activist Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (; March 17, 1912 – August 24, 1987) was an African American leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights.

Rustin worked with A. Philip Randolph on the March on Washington Movement, ...

was arrested in Pasadena, California, in 1953 for homosexual activity with two other men in a parked car. Originally charged with vagrancy and lewd conduct, he pleaded guilty to a single, lesser charge of "sex perversion" (as consensual sodomy was officially referred to in California then) and served 60 days in jail. This was the first time that his homosexuality had come to public attention. He had been and remained candid about his sexuality, although homosexuality was still criminalized throughout the United States. In 1957, Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

began organizing the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civ ...

(SCLC). Many African American leaders were concerned that Rustin's sexual orientation and past Communist membership would undermine support for the civil rights movement. U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., who was a member of the SCLC's board, forced Rustin's resignation from the SCLC in 1960 by threatening to discuss Rustin's morals charge in Congress. A few weeks before the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

in August 1963, Senator Strom Thurmond railed against Rustin as a "Communist, draft-dodger, and homosexual", and had the entire Pasadena arrest file entered in the record. Thurmond also produced a Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

photograph of Rustin talking to King while King was bathing, to imply that there was a same-sex relationship between the two. Both men denied the allegation of an affair. Rustin was instrumental in organizing the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

on August 7, 1963. He drilled off-duty police officers as marshals, bus captains to direct traffic, and scheduled the podium speakers. Eleanor Holmes Norton

Eleanor Holmes Norton (born June 13, 1937) is an American lawyer and politician serving as a delegate to the United States House of Representatives, representing the District of Columbia since 1991. She is a member of the Democratic Party.

Ea ...

and Rachelle Horowitz were aides. Despite King's support, NAACP chairman Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was a prominent activist in the Civil Rights Movement in the United States from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the ...

did not want Rustin to receive any public credit for his role in planning the march. Nevertheless, he did become well known. On September 6, 1963, Rustin and Randolph appeared on the cover of ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for Cell growth, growth, reaction to Stimu ...

'' magazine as "the leaders" of the March. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Rustin worked as a human rights and election monitor

Election monitoring involves the observation of an election by one or more independent parties, typically from another country or from a non-governmental organization (NGO). The monitoring parties aim primarily to assess the conduct of an electi ...

for Freedom House. He also testified on behalf of New York State's Gay Rights Bill. In 1986, he gave a speech "The New Niggers Are Gays", in which he asserted:

Communist and socialist states

The Soviet Government of the RSFSR decriminalized homosexuality in December 1917, following theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mome ...

and the discarding of the Legal Code of Tzarist Russia. Effectively the Soviet government decriminalized homosexuality in Russia and Ukraine after 1917. However, other states in the USSR continued to ascribe legal punishments on sodomy. This policy of decriminalizing homosexuality in the RSFSR and Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

endured for the bulk of the 1920s – until the Stalinist era. In 1933, the Soviet government, under Stalin, recriminalized homosexuality. On March 7, 1934, Article 121 was added to the criminal code, for the entire Soviet Union, that expressly prohibited only male homosexuality, with up to five years of hard labor in prison. There were no criminal statutes regarding lesbianism.

The lowest point in the history of the relationship between socialism and homosexuality begins with the rise

Rise or RISE may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* '' Rise: The Vieneo Province'', an internet-based virtual world

* Rise FM, a fictional radio station in the video game ''Grand Theft Auto 3''

* Rise Kujikawa, a vide ...

of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

in the USSR, after Lenin's death

On 21 January 1924, at 18:50 EET, Vladimir Lenin, leader of the October Revolution and the first leader and founder of the Soviet Union, died in Gorki aged 53 after falling into a coma. The official cause of death was recorded as an incurable d ...

, and continues through the era of state socialism in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

, China and North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

. In all cases the conditions of sexual minorities and transgender people worsened in communist states after the arrival of Stalin. Hundreds of thousands of homosexuals were interned in gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

s during the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

, where many were beaten to death. Some Western intellectuals withdrew their support of Communism after seeing the severity of repression in the USSR, including the gay writer André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anticolonialism ...

.

Historian Jennifer Evans reports that the East German government "alternated between the view f homosexual activityas a remnant of bourgeois decadence, a sign of moral weakness, and a threat to social and political health of the nation." Homosexuality was legalized in East Germany when Article 174 was repealed in 1968.

In Czechoslovakia, even after homosexuality was decriminalized in 1961 the secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of ...

(StB

State Security ( cs, Státní bezpečnost, sk, Štátna bezpečnosť) or StB / ŠtB, was the secret police force in communist Czechoslovakia from 1945 to its dissolution in 1990. Serving as an intelligence and counter-intelligence agency, it d ...

) used the threat of disclosure to force homosexuals to cooperate. Homesexuality was a taboo subject and first mentioned on Czech Radio

Český rozhlas (ČRo) is the public radio broadcaster of the Czech Republic operating since 1923. It is the oldest radio broadcaster in continental Europe and the second oldest in Europe after the BBC.

The service broadcasts throughout the C ...

in 1986, despite the AIDS epidemic. Those suspected of being homosexual suffered from employment discrimination.

There were a variety of attitudes to homosexuality in the socialist countries. Some states (such as the early Soviet Union prior to 1929–1933) practiced a degree of toleration. Others maintained negative policies towards homosexuals throughout their history, or gradually evolved to positions of relative toleration or official ignorance after the 1960s (East Germany, the USSR, etc.) In less tolerant periods effeminate men and homosexuals were sometimes forced to participate in programs of 'reeducation' involving forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

, conversion therapy

Conversion therapy is the pseudoscientific practice of attempting to change an individual's sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to align with heterosexual and cisgender norms. In contrast to evidence-based medicine and cl ...

, psychotropic drugs

A psychoactive drug, psychopharmaceutical, psychoactive agent or psychotropic drug is a chemical substance, that changes functions of the nervous system, and results in alterations in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition or behavior.

Th ...

or confinement in psychiatric hospital

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociat ...

s.

The revolutionary Cuban gay writer Reinaldo Arenas

Reinaldo Arenas (July 16, 1943 – December 7, 1990) was a Cuban poet, novelist, and playwright known as a vocal critic of Fidel Castro, the Cuban Revolution, and the Cuban government. His memoir of the Cuban dissident movement and of being a ...

noted that, shortly after the communist government of Fidel Castro came to power, "persecution began and concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

were opened ... the sexual act became taboo while the 'new man' was proclaimed and masculinity exalted." Homosexuality was legalized in Cuba in 1979. Fidel Castro apologized for Cuba's poor historical record on LGBT issues in 2010.

While there had been no law against sodomy at the time of the USSR's creation, such a law was introduced in 1933, added to the penal code as Article 121, which condemned homosexual relations with penalties of imprisonment up to five years. With the fall of the Soviet regime and the repeal of the law against sex between consenting adult men, prisoners convicted under that part of the law were released very slowly.

Homosexuality was legalized in several Eastern Bloc countries under Communism, such as Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

After 1968

During the emergence of the

During the emergence of the new social movements

The term new social movements (NSMs) is a theory of social movements that attempts to explain the plethora of new movements that have come up in various western societies roughly since the mid-1960s (i.e. in a post-industrial economy) which are cl ...

of the 1960s and 1970s, the socialist left began to review its relationship to gender, sexuality and identity politics

Identity politics is a political approach wherein people of a particular race, nationality, religion, gender, sexual orientation, social background, social class, or other identifying factors develop political agendas that are based upon these i ...

. The writings of the French bisexual anarchist Daniel Guérin

Daniel Guérin (; 19 May 1904, in Paris – 14 April 1988, in Suresnes) was a French libertarian-communist author, best known for his work '' Anarchism: From Theory to Practice'', as well as his collection ''No Gods No Masters: An Anthology of ...

offer an insight into the tension sexual minorities among the Left have often felt. He was a leading figure in the French Left from the 1930s until his death in 1988. After coming out in 1965, he spoke about the extreme hostility toward homosexuality that permeated the left throughout much of the 20th century. "Not so many years ago, to declare oneself a revolutionary and to confess to being homosexual were incompatible," Guérin wrote in 1975. In 1954, Guérin was widely attacked for his study of the Kinsey Reports in which he also detailed the oppression of homosexuals in France. "The harshest riticismscame from marxists, who tend seriously to underestimate the form of oppression which is antisexual terrorism. I expected it, of course, and I knew that in publishing my book I was running the risk of being attacked by those to whom I feel closest on a political level." After coming out publicly in 1965, Guérin was abandoned by the Left, and his papers on sexual liberation were censored or refused publication in left-wing journals. From the 1950s, Guérin moved away from Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism is a communist ideology which was the main communist movement throughout the 20th century. Developed by the Bolsheviks, it was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, its satellite states in the Eastern Bloc, and various c ...

and toward a synthesis of anarchism and marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

close to platformism

Platformism is a form of anarchist organization that seeks unity from its participants, having as a defining characteristic the idea that each platformist organization should include only people that are fully in agreement with core group ideas, r ...

which allowed for individualism while rejecting capitalism. Guérin was involved in the uprising of May 1968, and was a part of the French Gay Liberation movement that emerged after the events. Decades later, Frédéric Martel described Guérin as the "grandfather of the French homosexual movement". Meanwhile, in the United States late in his career the influential anarchist thinker Paul Goodman

Paul Goodman (1911–1972) was an American writer and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism. Goodman was prolific across numerous literary genres and non-fiction topics, including the arts, civil rights, decen ...

came out as bisexual. The freedom with which he revealed, in print and in public, his romantic and sexual relations with men (notably in a late essay, "Being Queer"), proved to be one of the many important cultural springboards for the emerging gay liberation

The gay liberation movement was a social and political movement of the late 1960s through the mid-1980s that urged lesbians and gay men to engage in radical direct action, and to counter societal shame with gay pride.Hoffman, 2007, pp.xi-xiii ...

movement of the early 1970s.

Emerging from a number of events, such as the May 1968 insurrection in France, the anti-Vietnam war movement

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War (before) or anti-Vietnam War movement (present) began with demonstrations in 1965 against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War and grew into a broad social mov ...

in the US and the Stonewall riots of 1969, militant Gay Liberation

The gay liberation movement was a social and political movement of the late 1960s through the mid-1980s that urged lesbians and gay men to engage in radical direct action, and to counter societal shame with gay pride.Hoffman, 2007, pp.xi-xiii ...

organizations began to spring up around the world. Many saw their roots in left radicalism more than in the established homophile groups of the time, such as British and American Gay Liberation Front

Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was the name of several gay liberation groups, the first of which was formed in New York City in 1969, immediately after the Stonewall riots. Similar organizations also formed in the UK and Canada. The GLF provided a ...

, the British Gay Left Collective, the Italian Fuori!, the French FHAR, the German Rotzschwule, and the Dutch Red Faggots.

The then styled Gay Lib leaders and writers also came from a left-wing background, such as Dennis Altman

Dennis Patkin Altman (born 16 August 1943) is an Australian academic and gay rights activist.

Early childhood

Altman was born in Sydney, New South Wales to Jewish immigrant parents, and spent most of his childhood in Hobart, Tasmania.

Educa ...

, Martin Duberman

Martin Bauml Duberman (born August 6, 1930) is an American historian, biographer, playwright, and gay rights activist. Duberman is Professor of History Emeritus at Herbert Lehman College in the Bronx, New York City.

Early life

Duberman was born ...

, Steven Ault, Brenda Howard, John D'Emilio, David Fernbach (writing in the English language), Pierre Hahn and Guy Hocquenghem (in French) and the Italian Mario Mieli. Some were inspired by Herbert Marcuse's ''Eros and Civilization

''Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud'' (1955; second edition, 1966) is a book by the German philosopher and social critic Herbert Marcuse, in which the author proposes a non-repressive society, attempts a synthesis of the t ...

'', which attempts to synthesise the ideas of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts ...

. 1960s and 1970s radical Angela Davis

Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American political activist, philosopher, academic, scholar, and author. She is a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz. A feminist and a Marxist, Davis was a longtime member of ...

(who officially came out as a lesbian in 1999) had studied under Marcuse and was greatly influenced by him. In France, gay activist and political theorist Guy Hocquenghem, like many others, developed a commitment to socialism through participating in the May 1968 insurrection. A former member of the French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Un ...

, he later joined the Front homosexuel d'action révolutionnaire

The front homosexuel d'action révolutionnaire ( en, Homosexual Front for Revolutionary Action) (FHAR) was a loose Parisian movement founded in 1971, resulting from a union between lesbian feminists and gay activists. If the movement could be con ...

(FHAR), formed by radical lesbians who split from the Mouvement Homophile de France in 1971, including the left ecofeminist

Ecofeminism is a branch of feminism and political ecology. Ecofeminist thinkers draw on the concept of gender to analyse the relationships between humans and the natural world. The term was coined by the French writer Françoise d'Eaubonne in h ...

Françoise d'Eaubonne

Françoise d'Eaubonne (12 March 1920 – 3 August 2005) was a French author, labour rights activist, environmentalist, and feminist. Her 1974 book, ''Le Féminisme ou la Mort'', introduced the term ecofeminism. She co-founded the Front homosexu ...

. That same year, the FHAR became the first homosexual group to demonstrate publicly in France when they joined Paris's annual May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Festivities may also be held the night before, known as May Eve. Tr ...

march held by trade unions and left-wing parties.

In the United Kingdom, the 1980s saw increased

In the United Kingdom, the 1980s saw increased LGBT rights opposition

LGBT rights opposition indicates the opposition to legal rights, proposed or enacted, for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people. Laws that LGBT rights opponents may be opposed to include civil unions or partnerships, LGBT par ...

from the right wing Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

government led by Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

, who introduced Section 28

Section 28 or Clause 28While going through Parliament, the amendment was constantly relabelled with a variety of clause numbers as other amendments were added to or deleted from the Bill, but by the final version of the Bill, which received R ...

in 1988 in order to prevent what they saw as the "promotion" of homosexuality as an acceptable lifestyle in schools. However, the Conservatives' main opposition, the Labour Party, did little to address the issue of LGBT rights, ignoring calls from left-wingers such as Ken Livingstone, to do so. Meanwhile, the popular right-wing press featured pejorative references to lesbians, supposedly especially associated with the all-female anti-nuclear protest camp at Greenham Common

Royal Air Force Greenham Common or RAF Greenham Common is a former Royal Air Force station in the civil parishes of Greenham and Thatcham in the English county of Berkshire. The airfield was southeast of Newbury, about west of London.

Opened ...

, and individuals such as Peter Tatchell

Peter Gary Tatchell (born 25 January 1952) is a British human rights campaigner, originally from Australia, best known for his work with LGBT social movements.

Tatchell was selected as the Labour Party's parliamentary candidate for Bermondsey ...

, the Labour candidate in the 1983 Bermondsey by-election

A by-election was held in the Bermondsey constituency in South London, on 24 February 1983, following the resignation of Labour MP Bob Mellish. Peter Tatchell stood as the candidate for the Labour Party, and Simon Hughes stood for the Libera ...

. However, the growing commercialisation of the western gay subculture in the late 20th and early 21st centuries (the "pink pound

Pink money describes the purchasing power of the LGBT community, often especially with respect to political donations. With the rise of the gay rights movement, pink money has gone from being a fringe or marginalized market to a thriving indust ...

") has come under heavy criticism from socialists. Hannah Dee remarked that it had reached "the point that London Pride – once a militant demonstration in commemoration of the Stonewall riots – has become a corporate-sponsored event far removed from any challenge to the ongoing injustices that we he LGBT communityface." At the same time, an anti-war coalition between Muslims (many organized through mosques) and the Socialist Workers Party led a leading member Lindsey German

Lindsey Ann German

''Evening Standard'' (This is London), 14 May 2004 (born 1951) is a ...

to reject the use of gay rights as a "shibboleth" that would automatically rule out such alliances.

The American Revolutionary Communist Party's policy that "struggle will be waged to eliminate omosexualityand reform homosexuals" was not abandoned until 2001. The RCP now strongly supports gay liberation. Meanwhile, the American Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in the US released a memo stating that gay oppression had less "social weight" than black and women's struggles, and prohibited members from being involved in gay political organizations. They also believed that too close an association with gay liberation would give the SWP an "exotic image" and alienate it from the masses.''Evening Standard'' (This is London), 14 May 2004 (born 1951) is a ...

Freedom Socialist Party

The Freedom Socialist Party is a left-wing socialist political party with a revolutionary feminist philosophy based in the United States. It views the struggles of women and minorities as part of the struggle of the working class. It emerged fro ...

, the Party for Socialism and Liberation

The Party for Socialism and Liberation (PSL) is a communist party in the United States, established in 2004. Its members are active in a wide range of movements including the labor, anti-war, immigrants' rights, women's rights, and anti-police ...

, the International Socialist Organization

The International Socialist Organization (ISO) was a Trotskyist group active primarily on college campuses in the United States that was founded in 1976 and dissolved in 2019. The organization held Leninist positions on imperialism and the role ...

, Socialist Alternative (United States)

Socialist Alternative (SA) is a Trotskyist socialist political party in the United States. It describes itself as a Marxist organization, and a revolutionary party fighting for a democratic, socialist economy. Unlike reformist progressive grou ...