Smenkhkare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Smenkhkare (alternatively romanized ''Smenkhare'', ''Smenkare,'' or ''Smenkhkara''; meaning "'Vigorous is the Soul of Re") was an ancient Egyptian

"The Amarna Succession"

in ''Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane'', ed. P. Brand and L. Cooper. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 37. Leiden: E. J. Brill Academic Publishers, 2006 and Marc Gabolde has suggested that after Smenkhkare's reign, Meritaten succeeded him as Neferneferuaten.

"globular vase"

from

a box (Carter 001k)

from Tutankhamun's tomb that lists Akhenaten, Neferneferuaten, and Meritaten as three separate individuals. There, Meritaten is explicitly listed as Great Royal Wife. Further, various private stelae depict the female pharaoh with Akhenaten. However under this theory, Akhenaten would be dead by the time Meritaten became pharaoh as Neferneferuaten. Gabolde suggest that these depictions are retrospective. Yet since these are private cult stelae it would require a number of people to get the same idea to commission a retrospective, commemorative stela at the same time. Allen notes that the everyday interaction portrayed in them more likely indicates two living people.

There has been much confusion in identifying artifacts related to Smenkhkare because another pharaoh from the Amarna Period bears the same or similar royal titulary. In 1978, it was proposed that there were two individuals using the same name: a male king Smenkhkare and a female Neferneferuaten.

There has been much confusion in identifying artifacts related to Smenkhkare because another pharaoh from the Amarna Period bears the same or similar royal titulary. In 1978, it was proposed that there were two individuals using the same name: a male king Smenkhkare and a female Neferneferuaten.

stele in Berlin

depicts a pair of royal figures, one in the double crown and the other, who appears to be a woman, in the khepresh crown. However, the set of three empty cartouches can only account for the names of a king and queen. This has been interpreted to mean that at one point

* The

* The

now in the

Item UC23800

in the

47 other sequins

bearing the prenomen of Smenkhkare alongside Meritaten's name. * Carter number 101s is

with the name Ankhkheperure * A compound bow (Carter 48h) and the mummy bands (Carter 256b) were both reworked for Tutankhamun.Reeves, C. 1990b * Less certain, but much more impressive is th

containing the mummy of Tutankhamun. The face depicted is much more square than that of the other coffins and quite unlike the gold mask or other depictions of Tutankhamun. The coffin is rishi style and inlaid with coloured glass, a feature only found on this coffin and one from KV55, the speculated resting place for the mummy of Smenkhkare. Since both cartouches show signs of being reworked, Dodson and Harrison conclude this was most likely originally made for Smenkhkare and reinscribed for Tutankhamun. As the evidence came to light in bits and pieces at a time when Smenkhkare was assumed to have also used the name Neferneferuaten, perhaps at the start of his sole reign, it sometimes defied logic. For instance, when the mortuary wine docket surfaced from the 'House of Smenkhkare (deceased)', it seemed to appear that he changed his name back before he died. Since his reign was brief, and he may never have been more than co-regent, the evidence for Smenkhkare is not plentiful, but nor is it quite as insubstantial as it is sometimes made out to be. It certainly amounts to more than just 'a few rings and a wine docket' or that he 'appears only at the very end of Ahkenaton's reign in a few monuments' as is too often portrayed.

The location of Smenkhkare's burial is unconfirmed. He has been put forward as a candidate for the mummy discovered in KV55, which rested in a desecrated

The location of Smenkhkare's burial is unconfirmed. He has been put forward as a candidate for the mummy discovered in KV55, which rested in a desecrated  In 1980, James Harris and Edward F. Wente conducted X-ray examinations of New Kingdom Pharaoh's crania and skeletal remains, which included the supposed mummified remains of Smenkhkare. The authors determined that the royal mummies of the 18th Dynasty bore strong similarities to contemporary Nubians with slight differences.

Initial studies conducted on the KV55 mummy indicated that the individual was a young man with no apparent abnormalities in his mid-twenties or younger.Strouhal, E. "Biological age of skeletonized mummy from Tomb KV 55 at Thebes" in ''Anthropologie: International Journal of the Science of Man'' Vol 48 Issue 2 (2010), pp 97–112. Dr. Strouhal examined KV55 in 1998, but the results were apparently delayed and perhaps eclipsed by Filer's examination in 2000. Strouhal's findings were published in 2010 to dispute the Hawass et al conclusions. Another study used craniofacial analysis and examined past x-rays on several 18th Dynasty mummies. That study found close cranial similarities between the mummies of Tutankhamun, KV55 and Thutmose IV. In addition, seriological tests published in ''Nature'' in 1974 indicated that the KV55 mummy and Tutankhamun shared the same rare blood type. This information led Egyptologists to conclude that the KV55 mummy was either the father or brother of Tutankhamun. A brother seemed more likely since the age would only be old enough to plausibly father a child at the upper extremes.

However, the academic debate was believed concluded following a 2010 genetic study performed by Zahi Hawass that determined that the parents of Tutankhamun were likely the KV55 mummy and “ The Younger Lady” mummy from KV35.Hawass, Z., Y. Z. Gad, et al

In 1980, James Harris and Edward F. Wente conducted X-ray examinations of New Kingdom Pharaoh's crania and skeletal remains, which included the supposed mummified remains of Smenkhkare. The authors determined that the royal mummies of the 18th Dynasty bore strong similarities to contemporary Nubians with slight differences.

Initial studies conducted on the KV55 mummy indicated that the individual was a young man with no apparent abnormalities in his mid-twenties or younger.Strouhal, E. "Biological age of skeletonized mummy from Tomb KV 55 at Thebes" in ''Anthropologie: International Journal of the Science of Man'' Vol 48 Issue 2 (2010), pp 97–112. Dr. Strouhal examined KV55 in 1998, but the results were apparently delayed and perhaps eclipsed by Filer's examination in 2000. Strouhal's findings were published in 2010 to dispute the Hawass et al conclusions. Another study used craniofacial analysis and examined past x-rays on several 18th Dynasty mummies. That study found close cranial similarities between the mummies of Tutankhamun, KV55 and Thutmose IV. In addition, seriological tests published in ''Nature'' in 1974 indicated that the KV55 mummy and Tutankhamun shared the same rare blood type. This information led Egyptologists to conclude that the KV55 mummy was either the father or brother of Tutankhamun. A brother seemed more likely since the age would only be old enough to plausibly father a child at the upper extremes.

However, the academic debate was believed concluded following a 2010 genetic study performed by Zahi Hawass that determined that the parents of Tutankhamun were likely the KV55 mummy and “ The Younger Lady” mummy from KV35.Hawass, Z., Y. Z. Gad, et al

"Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family"

''Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)'', 2010. Chief among the genetic results was, "''The statistical analysis revealed that the mummy KV55 is most probably the father of Tutankhamun (probability of 99.99999981%), and KV35 Younger Lady could be identified as his mother (99.99999997%).''" The study further identified the two mummies as children of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye. CT scans also performed on the KV55 mummy indicated that his age at the time of death was likely higher than previous estimates, based on the reveal of age-related degeneration in the spine and osteoarthritis in the knees and spine. These estimates placed the mummy's age at death closer to 40 years than 25. This led to further belief that the mummy was in fact Akhenaten. However, evidence to support the much older claim was not provided beyond the single point of spinal degeneration. Other scholars still dispute Hawass's assessment of the mummy's age and the identification of KV55 as Akhenaten.Bickerstaffe, D. ''The King is dead. How Long Lived the King?'' in ''Kmt'' vol 22, n 2, Summer 2010.

retrieved Nov 2012 Where Filer and Strouhal relied on multiple indicators to determine the younger age, the new study cited one point to indicate a much older age. One letter to the ''JAMA'' editors came from

Online English Press Release

* * * Filer, J. "Anatomy of a Mummy." ''Archaeology'', Mar/Apr2002, Vol. 55 Issue 2 * Gabolde, Marc. ''D’Akhenaton à Tout-ânkhamon'' (1998) Paris * Giles, Frederick. J. ''Ikhnaton Legend and History'' (1970, Associated University Press, 1972 US) * Giles, Frederick. J. ''The Amarna Age: Egypt'' (Australian Centre for Egyptology, 2001) * Habicht, Michael E. ''Semenchkare – Phantom-König(in) von Achet-Aton'' (e-publication, Berlin 2014). * Habicht, Michael E. ''Smenkhkare: Phantom-Queen/King of Akhet-Aton and the quest for the hitherto unknown chambers in the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV 62)'' (e-publication, Berlin 2017)

* Hawass, Z., Y. Gad, et al. ''Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family'' (2010) in Journal of the American medical Association 303/7. * Hornung, E. ''Akhenaten and the Religion of Light'', Cornell University, 1999 * Hornung, E. "The New Kingdom"', in E. Hornung, R. Krauss, and D. A. Warburton, eds., ''Ancient Egyptian Chronology'' (HdO I/83), Leiden – Boston, 2006. * Krauss, Rolf. ''Das Ende der Amarnazeit'' (The End of the Amarna Period); 1978, Hildesheim * Miller, J. ''Amarna Age Chronology and the Identity of Nibhururiya'' in ''Altoriental. Forsch.'' 34 (2007) * Moran, William L. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992 * Murnane, W. ''Ancient Egyptian Coregencies'' (1977) * Murnane, W. ''Texts from the Amarna Period'' (1995) * Newberry, P. E. 'Appendix III: Report on the Floral Wreaths Found in the Coffins of Tut.Ankh.Amen' in H. Carter, ''The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen Volume Two'' London: Cassell (1927) * O'Connor, D and Cline, E, (eds); ''Amenhotep III: perspectives on his reign'' (1998) University of Michigan Press * Pendlebury J., Samson, J. et al. ''City of Akhenaten, Part III'' (1951) * Petrie, W. M. Flinders; ''Tell el Amarna'' (1894) * Reeves, C.N. ''Akhenaten, Egypt's false Prophet'' (Thames and Hudson; 2001) * Reeves, C.N. ''The Valley of the Kings'' (Kegan Paul, 1990) * Reeves, C.N. ''The Complete Tutankhamun: The King – The Tomb – The Royal Treasure''. London: Thames and Hudson; 1990. * * Theis, Christoffer, ''"Der Brief der Königin Daḫamunzu an den hethitischen König Šuppiluliuma I im Lichte von Reisegeschwindigkeiten und Zeitabläufen"'', in Thomas R. Kämmerer (Hrsg.), ''Identities and Societies in the Ancient East-Mediterranean Regions.'' Comparative Approaches. Henning Graf Reventlow Memorial Volume (= AAMO 1, AOAT 390/1). Münster 2011, S. 301–331 * Wente, E. ''Who Was Who Among the Royal Mummies?'' (1995), Oriental Institute, Chicago {{Authority control 14th-century BC Pharaohs Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt Historical negationism in ancient Egypt Akhenaten

pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

of unknown background who lived and ruled during the Amarna Period

The Amarna Period was an era of Egyptian history during the later half of the Eighteenth Dynasty when the royal residence of the pharaoh and his queen was shifted to Akhetaten ('Horizon of the Aten') in what is now Amarna. It was marked by the ...

of the 18th Dynasty. Smenkhkare was husband to Meritaten, the daughter of his likely co-regent, Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Echnaton, Akhenaton, ( egy, ꜣḫ-n-jtn ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth D ...

. Very little is known of Smenkhkare for certain because later kings sought to erase the Amarna Period from history. Because of this, perhaps no one from the Amarna Interlude has been the subject of so much speculation as Smenkhkare.

Origin and family

Smenkhkare's origins are unknown. It is assumed he was a member of the royal family, likely either a brother or son of the pharaohAkhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Echnaton, Akhenaton, ( egy, ꜣḫ-n-jtn ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth D ...

. If he is Akhenaten's brother, his mother was likely either Tiye

Tiye (c. 1398 BC – 1338 BC, also spelled Tye, Taia, Tiy and Tiyi) was the daughter of Yuya and Thuya. She became the Great Royal Wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III. She was the mother of Akhenaten and grandmother of Tutankhamun. ...

or Sitamun

Sitamun, also Sitamen, Satamun; egy, sꜣ.t-imn, "daughter of Amun" (c. 1370 BCE–unknown) was an ancient Egyptian princess and queen consort during the 18th Dynasty.

Family

Sitamun is considered to be the eldest daughter of Pharaoh Amenhotep ...

. If a son of Akhenaten, he was presumably an older brother of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

, as he succeeded the throne ahead of him; his mother was likely an unknown, lesser wife. An alternative suggestion, based on objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun (reigned c. 1334–1325 BC), a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chambers ...

, is that Smenkhkare was the son of Akhenaten's older brother, Thutmose and an unknown woman, possibly one of his sisters.

Smenkhkare is known to have married Akhenaten's eldest daughter, Meritaten, who was his Great Royal Wife

Great Royal Wife, or alternatively, Chief King's Wife ( Ancient Egyptian: ''ḥmt nswt wrt'', cop, Ⲟⲩⲏⲣ Ⲟⲩⲣϣ), is the title that was used to refer to the principal wife of the pharaoh of Ancient Egypt, who served many official ...

. Inscriptions mention a King's Daughter named Meritaten Tasherit

Meritaten Tasherit, which means ''Meritaten the Younger'' was an ancient Egyptian princess of the 18th Dynasty. She is likely to have been the daughter of Meritaten, eldest daughter of Pharaoh Akhenaten.

Who her father was remains a matter of de ...

, who may be the daughter of Meritaten and Smenkhkare.J. Tyldesley, ''Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt'', 2006, Thames & Hudson, pg 136–137Aldred, Cyril, Akhenaten: King of Egypt ,Thames and Hudson, 1991 (paperback), Furthermore, Smenkhkare has been put forth as a candidate for the mummy in KV55. If so, he would be the father of Tutankhamun.

Reign as pharaoh

Length of reign

Clear evidence for a sole reign for Smenkhkare has not yet been found. There are few artifacts that attest to his existence at all, and so it is assumed his reign was short. A wine docket from "the house of Smenkhkare" attests to Regnal Year 1. A second wine docket dated to Year 1 refers to him as "Smenkhkare, (deceased)" and may indicate that he died during his first regnal year. Some Egyptologists have speculated about the possibility of a two- or three-year reign for Smenkhkare based on a number of wine dockets from Amarna that lack a king's name but bear dates for regnal years 2 and 3. However, they could belong to any of the Amarna kings and are not definitive proof either way.Miller, J. (2007) p 275Smenkhkare Hall

While there are few monuments or artifacts that attest to Smenkhkare's existence, there is a major addition to the Amarna palace complex that bears his name. It was built in approximately Year 15 and was likely built for a significant event related to him.Theories of timing of Smenkhkare's reign

Academic consensus has yet to be reached about when exactly Smenkhkare ruled as pharaoh and where he falls in the timeline of Amarna. In particular, the confusion of his identity compared to that of Pharaoh Neferneferuaten has led to considerable academic debate about the order of kings in the late Amarna Period. Aidan Dodson suggests that Smenkhkare did not have a sole reign and only served as Akhenaten's co-regent for about a year around Regnal Year 13. However, James Peter Allen depicts Smenkhkare as successor toNeferneferuaten

Ankhkheperure-Merit-Neferkheperure/Waenre/Aten Neferneferuaten ( egy, nfr-nfrw-jtn) was a name used to refer to a female pharaoh who reigned toward the end of the Amarna Period during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Her sex is confirmed by feminine ...

James P. Allen"The Amarna Succession"

in ''Causing His Name to Live: Studies in Egyptian Epigraphy and History in Memory of William J. Murnane'', ed. P. Brand and L. Cooper. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 37. Leiden: E. J. Brill Academic Publishers, 2006 and Marc Gabolde has suggested that after Smenkhkare's reign, Meritaten succeeded him as Neferneferuaten.

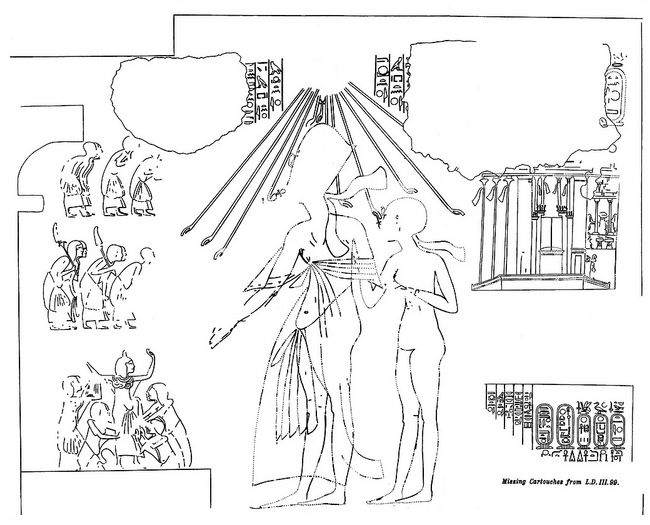

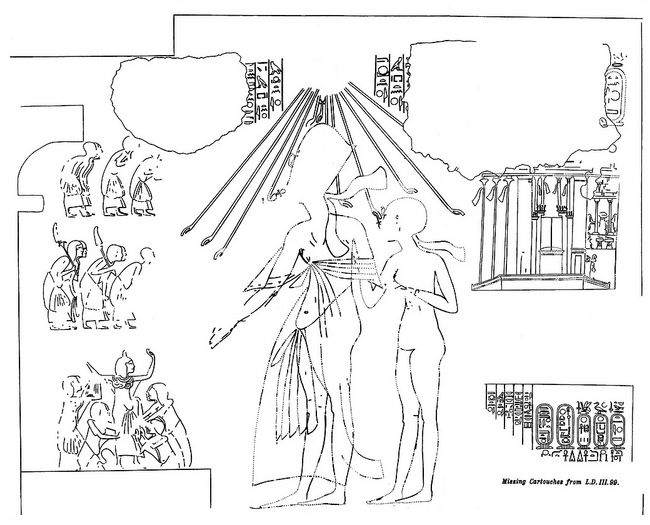

Co-regency with Akhenaten

Per Dodson's theory, Smenkhkare served only as co-regent with Akhenaten and never had an individual rule and Nefertiti became co-regent and eventual successor to Akhenaten. Smenkhkare and Meritaten appear together in the tomb of Meryre II at Amarna, rewarding Meryre. There, Smenkhkare wears the khepresh crown, however he is called the son-in-law of Akhenaten. Further, his name appears only during Akhenaten's reign without certain evidence to attest to a sole reign.Duhig, Corinne. "The remains of Pharaoh Akhenaten are not yet identified: comments on 'Biological age of the skeletonized mummy from Tomb KV55 at Thebes (Egypt)' by Eugen Strouhal" in ''Anthropologie: International Journal of the Science of Man'' Vol 48 Issue 2 (2010), pp 113–115. The names of the king have since been cut out but were recorded around 1850 by Karl Lepsius. Additionally, a calcit"globular vase"

from

Tutankhamun's tomb

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun (reigned c. 1334–1325 BC), a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb consists of four chamber ...

displays the full double cartouches of both pharaohs. However, this is the only object known to carry both names side-by-side. This evidence has been taken by some Egyptologists to indicate that Akhenaten and Smenkhkare were co-regents. However, the scene in Meryre's tomb is undated and Akhenaten is neither depicted nor mentioned in the tomb. The jar may simply be a case of one king associating himself with a predecessor. The simple association of names, particularly on everyday objects, is not conclusive of a co-regency.Allen, J. (2006) p 3

Smenkhkare as successor to Neferneferuaten

Arguing against the co-regency theory, Allen suggests that Neferneferuaten followed Akhenaten and that upon her death, Smenkhkare ascended as pharaoh. Allen proposes that following Nefertiti's death in Year 13 or 14, her daughter Neferneferuaten-tasherit became Pharaoh Neferneferuaten. After Neferneferuaten's short rule of two or three years, according to Allen, Smenkhkare became pharaoh. Under this theory, both pharaohs succeeded Akhenaten: Neferneferuaten as the chosen successor and Smenkhkare as a rival with the same prenomen, perhaps to challenge Akhenaten's unacceptable choice. However, a hieratic inscription discovered at the limestone quarry at Dayr Abu Hinnis suggests that Nefertiti was alive in Akhenaten's Year 16, undermining this theory. There, Nefertiti is referred to as the pharaoh's Great Royal Wife. Furthermore, work is believed to have halted on the Amarna tombs shortly after Year 13. Therefore, the depiction of Smenkhkare in Meryre's tomb must date to no later than Year 13. For him to have succeeded Neferneferuaten means that aside from a lone wine docket, he left not a single trace over the course of five to six years.Meritaten as successor to Smenkhkare

In comparison to the theories mentioned above, Marc Gabolde has advocated that Smenkhkare's Great Royal Wife, Meritaten, became Pharaoh Neferneferuaten after her husband's death. The main argument against this ia box (Carter 001k)

from Tutankhamun's tomb that lists Akhenaten, Neferneferuaten, and Meritaten as three separate individuals. There, Meritaten is explicitly listed as Great Royal Wife. Further, various private stelae depict the female pharaoh with Akhenaten. However under this theory, Akhenaten would be dead by the time Meritaten became pharaoh as Neferneferuaten. Gabolde suggest that these depictions are retrospective. Yet since these are private cult stelae it would require a number of people to get the same idea to commission a retrospective, commemorative stela at the same time. Allen notes that the everyday interaction portrayed in them more likely indicates two living people.

Identity and confusion over regnal name

There has been much confusion in identifying artifacts related to Smenkhkare because another pharaoh from the Amarna Period bears the same or similar royal titulary. In 1978, it was proposed that there were two individuals using the same name: a male king Smenkhkare and a female Neferneferuaten.

There has been much confusion in identifying artifacts related to Smenkhkare because another pharaoh from the Amarna Period bears the same or similar royal titulary. In 1978, it was proposed that there were two individuals using the same name: a male king Smenkhkare and a female Neferneferuaten. Neferneferuaten

Ankhkheperure-Merit-Neferkheperure/Waenre/Aten Neferneferuaten ( egy, nfr-nfrw-jtn) was a name used to refer to a female pharaoh who reigned toward the end of the Amarna Period during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Her sex is confirmed by feminine ...

has since been identified as a female pharaoh who ruled during the Amarna Period and is generally accepted as a separate person from Smenkhkare. Neferneferuaten is theorized to be either Nefertiti

Neferneferuaten Nefertiti () ( – c. 1330 BC) was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for a radical change in national religious policy, in which ...

, Meritaten, or, more rarely, Neferneferuaten Tasherit.

After their initial rediscovery, Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten were assumed to be the same person because of their similar prenomen (throne name). Typically, throne names in Ancient Egypt were unique. Thus, the use of similar titulary led to a great deal of confusion among Egyptologists.Dodson, A. (2009) p 34 For the better part of a century, the repetition of throne names was taken to mean that Smenkhare changed his name to Neferneferuaten at some point, probably upon the start of his sole reign. Indeed, Petrie makes exactly that distinction in his 1894 excavation notes. Later, a different set of names emerged using the same: "''Ankhkheperure mery Neferkheperure'' khenaten''Neferneferuaten mery Wa en Re'' khenaten.

Smenkhkare can be differentiated from Neferneferutaten by the lack of an epithet associated with his throne name. James Peter Allen pointed out the name 'Ankhkheperure' nearly always included the epithet 'desired of Wa en Re' (referring to Akhenaten) when coupled with the nomen 'Neferneferuaten'. There were no occasions where 'Ankhkheprure plus epithet' occurred alongside 'Smenkhkare;' nor was plain 'Ankhkheperure' ever found associated with the nomen Neferneferuaten. However, differentiating between the two individuals when 'Ankhkheperure' occurs alone is complicated by the Pawah graffito from TT139. Here, Ankhkheperure is used alone twice when referring to Neferneferutaten. In some instances, a female version 'Ankhetkheperure' occurs; in this case the individual is Neferneferuaten.

The issue of a female Neferneferuaten was finally settled for the remaining holdouts when Allen confirmed Marc Gabolde's findings that objects from Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

's tomb originally inscribed for Neferneferuaten which had been read using the epithet "...desired of Akhenaten" were originally inscribed as ''Akhet-en-hyes'' or "effective for her husband."

Theories

Akhenaten and Smenkhkare as homosexual couple

Theories arose when the two pharaohs Smenkhkare and Neferneferutaten were still considered the same, male person, that he and Akhenaten could have been homosexual lovers or even married. This is because of artwork clearly showing Akhenaten in familiar, intimate poses with another pharaoh. For examplestele in Berlin

depicts a pair of royal figures, one in the double crown and the other, who appears to be a woman, in the khepresh crown. However, the set of three empty cartouches can only account for the names of a king and queen. This has been interpreted to mean that at one point

Nefertiti

Neferneferuaten Nefertiti () ( – c. 1330 BC) was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for a radical change in national religious policy, in which ...

may have been a coregent, as indicated by the crown, but not entitled to full pharaonic honors such as the double cartouche. Furthermore, it is now accepted that other artifacts similar to this one are depictions of Akhenaten and Neferneferuaten.

Nefertiti as Smenkhkare

Alternatively, once the feminine traces were discovered in some versions of the throne names, it was proposed thatNefertiti

Neferneferuaten Nefertiti () ( – c. 1330 BC) was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for a radical change in national religious policy, in which ...

was masquerading as Smenkhkare and later changed her name back to Neferneferuaten. There would be precedent for presenting a female pharaoh as a male, such as Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut (; also Hatchepsut; Egyptian: '' ḥꜣt- špswt'' "Foremost of Noble Ladies"; or Hatasu c. 1507–1458 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, af ...

had done generations prior.

Evidence

* The

* The Coregency Stela The Coregency Stela is an ancient Egyptian stela dating from the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. It consists of seven limestone fragments, which were found in a tomb at Amarna. The tablet shows the figures of Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Meritaten. ...

br>U.C. 410now in the

Petrie Museum

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London is part of University College London Museums and Collections. The museum contains over 80,000 objects and ranks among some of the world's leading collections of Egyptian and Sudanese material ...

. Although badly damaged, partial inscriptions survive. It shows the double cartouche of Akhenaten alongside that of ''Ankhkheperure mery-Waenre Neferneferuaten Akhet-en-hyes'' ('effective for her husband'). The inscription originally bore the single cartouche of Nefertiti, which was erased along with a reference to Meritaten to make room for the double cartouche of King Neferneferuaten.Dodson, A. (2009); p 43

*Line drawings of a block depicting the nearly complete names of King Smenkhkare and Meritaten as Great Royal Wife were recorded before the block was lost.

* Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Flinders Petrie, was a British Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of Egyp ...

documented six rings bearing only the Throne Name 'Ankhkheperure' (the other six with the same Throne Name show an epithet: or Mery Neferkheperure, no. 92 and no. 93; or Mery Waenre, no. 94, 95, and 96) and two more bearing 'Smenkhkare' (with another one bearing the epithet Djeserkheperu, which belonged to Smenkhkare) in excavations of the palace. One example iItem UC23800

in the

Petrie Museum

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London is part of University College London Museums and Collections. The museum contains over 80,000 objects and ranks among some of the world's leading collections of Egyptian and Sudanese material ...

which clearly shows the "djeser" and "kheperu" elements and a portion of the 'ka' glyph. Pendlebury found more when the town was cleared.

* A ring bearing his name is found at Malqata in Thebes.

* Perhaps the most magnificent was a vast hall more than 125 metres square and including over 500 pillars. This late addition to the central palace has been known as the Hall of Rejoicing, Coronation Hall, or simply Smenkhkare Hall because a number of bricks stamped ''Ankhkheperure in the House of Rejoicing in the Aten'' were found at the site.

* Indisputable images for Smenkhkare are rare. Aside from the tomb of Meryre II, a carved and painted relief showing an Amarna

Amarna (; ar, العمارنة, al-ʿamārnah) is an extensive Egyptian archaeological site containing the remains of what was the capital city of the late Eighteenth Dynasty. The city was established in 1346 BC, built at the direction of the Ph ...

king and queen in a garden is often attributed to him. It is completely without inscription, but since they do not look like Tutankhamun or his queen, they are often assumed to be Smenkhkare and Meritaten, but Akhenaten and Nefertiti

Neferneferuaten Nefertiti () ( – c. 1330 BC) was a queen of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, the great royal wife of Pharaoh Akhenaten. Nefertiti and her husband were known for a radical change in national religious policy, in which ...

are sometimes put forth as well.

* An inscription in the tomb of Pairi, TT139, by the other Ankhkheperure (Neferneferuaten), mentions a functioning Amen 'temple of Ankhkheperure'.

Several items from the tomb of Tutankhamun bear the name of Smenkhkare:

* A linen garment decorated with 39 gold daisies along wit47 other sequins

bearing the prenomen of Smenkhkare alongside Meritaten's name. * Carter number 101s is

with the name Ankhkheperure * A compound bow (Carter 48h) and the mummy bands (Carter 256b) were both reworked for Tutankhamun.Reeves, C. 1990b * Less certain, but much more impressive is th

containing the mummy of Tutankhamun. The face depicted is much more square than that of the other coffins and quite unlike the gold mask or other depictions of Tutankhamun. The coffin is rishi style and inlaid with coloured glass, a feature only found on this coffin and one from KV55, the speculated resting place for the mummy of Smenkhkare. Since both cartouches show signs of being reworked, Dodson and Harrison conclude this was most likely originally made for Smenkhkare and reinscribed for Tutankhamun. As the evidence came to light in bits and pieces at a time when Smenkhkare was assumed to have also used the name Neferneferuaten, perhaps at the start of his sole reign, it sometimes defied logic. For instance, when the mortuary wine docket surfaced from the 'House of Smenkhkare (deceased)', it seemed to appear that he changed his name back before he died. Since his reign was brief, and he may never have been more than co-regent, the evidence for Smenkhkare is not plentiful, but nor is it quite as insubstantial as it is sometimes made out to be. It certainly amounts to more than just 'a few rings and a wine docket' or that he 'appears only at the very end of Ahkenaton's reign in a few monuments' as is too often portrayed.

Death and burial

The location of Smenkhkare's burial is unconfirmed. He has been put forward as a candidate for the mummy discovered in KV55, which rested in a desecrated

The location of Smenkhkare's burial is unconfirmed. He has been put forward as a candidate for the mummy discovered in KV55, which rested in a desecrated rishi coffin

Rishi coffins are funerary coffins adorned with a feather design, which were used in Ancient Egypt. They are typical of the Egyptian Second Intermediate Period, circa 1650 to 1550 BC. The name comes from ريشة (''risha''), Arabic for "feather" ...

with the owner’s name removed. It is generally accepted that the coffin was originally intended for a female and later reworked to accommodate a male. Over the past century, the chief candidates for this individual have been either Akhenaten or Smenkhkare. The case for Smenkhkare comes mostly from the presumed age of the mummy (see below) which, between ages 18 and 26 would not fit Akhenaten who reigned for 17 years and had fathered a child near by his first regnal year. There is nothing in the tomb positively identified as belonging to Smenkhkare, nor is his name found there. The tomb is certainly not befitting any king, but even less so for Akhenaten. In 1980, James Harris and Edward F. Wente conducted X-ray examinations of New Kingdom Pharaoh's crania and skeletal remains, which included the supposed mummified remains of Smenkhkare. The authors determined that the royal mummies of the 18th Dynasty bore strong similarities to contemporary Nubians with slight differences.

Initial studies conducted on the KV55 mummy indicated that the individual was a young man with no apparent abnormalities in his mid-twenties or younger.Strouhal, E. "Biological age of skeletonized mummy from Tomb KV 55 at Thebes" in ''Anthropologie: International Journal of the Science of Man'' Vol 48 Issue 2 (2010), pp 97–112. Dr. Strouhal examined KV55 in 1998, but the results were apparently delayed and perhaps eclipsed by Filer's examination in 2000. Strouhal's findings were published in 2010 to dispute the Hawass et al conclusions. Another study used craniofacial analysis and examined past x-rays on several 18th Dynasty mummies. That study found close cranial similarities between the mummies of Tutankhamun, KV55 and Thutmose IV. In addition, seriological tests published in ''Nature'' in 1974 indicated that the KV55 mummy and Tutankhamun shared the same rare blood type. This information led Egyptologists to conclude that the KV55 mummy was either the father or brother of Tutankhamun. A brother seemed more likely since the age would only be old enough to plausibly father a child at the upper extremes.

However, the academic debate was believed concluded following a 2010 genetic study performed by Zahi Hawass that determined that the parents of Tutankhamun were likely the KV55 mummy and “ The Younger Lady” mummy from KV35.Hawass, Z., Y. Z. Gad, et al

In 1980, James Harris and Edward F. Wente conducted X-ray examinations of New Kingdom Pharaoh's crania and skeletal remains, which included the supposed mummified remains of Smenkhkare. The authors determined that the royal mummies of the 18th Dynasty bore strong similarities to contemporary Nubians with slight differences.

Initial studies conducted on the KV55 mummy indicated that the individual was a young man with no apparent abnormalities in his mid-twenties or younger.Strouhal, E. "Biological age of skeletonized mummy from Tomb KV 55 at Thebes" in ''Anthropologie: International Journal of the Science of Man'' Vol 48 Issue 2 (2010), pp 97–112. Dr. Strouhal examined KV55 in 1998, but the results were apparently delayed and perhaps eclipsed by Filer's examination in 2000. Strouhal's findings were published in 2010 to dispute the Hawass et al conclusions. Another study used craniofacial analysis and examined past x-rays on several 18th Dynasty mummies. That study found close cranial similarities between the mummies of Tutankhamun, KV55 and Thutmose IV. In addition, seriological tests published in ''Nature'' in 1974 indicated that the KV55 mummy and Tutankhamun shared the same rare blood type. This information led Egyptologists to conclude that the KV55 mummy was either the father or brother of Tutankhamun. A brother seemed more likely since the age would only be old enough to plausibly father a child at the upper extremes.

However, the academic debate was believed concluded following a 2010 genetic study performed by Zahi Hawass that determined that the parents of Tutankhamun were likely the KV55 mummy and “ The Younger Lady” mummy from KV35.Hawass, Z., Y. Z. Gad, et al"Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family"

''Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)'', 2010. Chief among the genetic results was, "''The statistical analysis revealed that the mummy KV55 is most probably the father of Tutankhamun (probability of 99.99999981%), and KV35 Younger Lady could be identified as his mother (99.99999997%).''" The study further identified the two mummies as children of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye. CT scans also performed on the KV55 mummy indicated that his age at the time of death was likely higher than previous estimates, based on the reveal of age-related degeneration in the spine and osteoarthritis in the knees and spine. These estimates placed the mummy's age at death closer to 40 years than 25. This led to further belief that the mummy was in fact Akhenaten. However, evidence to support the much older claim was not provided beyond the single point of spinal degeneration. Other scholars still dispute Hawass's assessment of the mummy's age and the identification of KV55 as Akhenaten.Bickerstaffe, D. ''The King is dead. How Long Lived the King?'' in ''Kmt'' vol 22, n 2, Summer 2010.

retrieved Nov 2012 Where Filer and Strouhal relied on multiple indicators to determine the younger age, the new study cited one point to indicate a much older age. One letter to the ''JAMA'' editors came from

Arizona State University

Arizona State University (Arizona State or ASU) is a public research university in the Phoenix metropolitan area. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, ASU is one of the largest public universities by enrollment in the ...

bioarchaeologist Brenda J. Baker. The content was retold on the Archaeology News Network website and is representative of a portion of the dissent:

An examination of the KV55 mummy was conducted in 1998 by Czech anthropologist Eugene Strouhal. He published his conclusions in 2010 where he 'utterly excluded the possibility of Akhenaten':

References

Bibliography

* Aldred, Cyril. ''Akhenaten, King of Egypt'' (Thames & Hudson, 1988) * Aldred, Cyril. ''Akhenaten, Pharaoh of Light'' (Thames & Hudson, 1968) * Allen, James P. ''Two Altered Inscriptions of the Late Amarna Period'', Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 25 (1988) * * Allen, James P. ''Nefertiti and Smenkh-ka-re''. Göttinger Miszellen 141; (1994) * Bryce, Trevor R. “The Death of Niphururiya and Its Aftermath.” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 76, 1990, pp. 97–105. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3822010. * Dayr al-Barsha Project; Press Release, Dec. 2012Online English Press Release

* * * Filer, J. "Anatomy of a Mummy." ''Archaeology'', Mar/Apr2002, Vol. 55 Issue 2 * Gabolde, Marc. ''D’Akhenaton à Tout-ânkhamon'' (1998) Paris * Giles, Frederick. J. ''Ikhnaton Legend and History'' (1970, Associated University Press, 1972 US) * Giles, Frederick. J. ''The Amarna Age: Egypt'' (Australian Centre for Egyptology, 2001) * Habicht, Michael E. ''Semenchkare – Phantom-König(in) von Achet-Aton'' (e-publication, Berlin 2014). * Habicht, Michael E. ''Smenkhkare: Phantom-Queen/King of Akhet-Aton and the quest for the hitherto unknown chambers in the tomb of Tutankhamun (KV 62)'' (e-publication, Berlin 2017)

* Hawass, Z., Y. Gad, et al. ''Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun’s Family'' (2010) in Journal of the American medical Association 303/7. * Hornung, E. ''Akhenaten and the Religion of Light'', Cornell University, 1999 * Hornung, E. "The New Kingdom"', in E. Hornung, R. Krauss, and D. A. Warburton, eds., ''Ancient Egyptian Chronology'' (HdO I/83), Leiden – Boston, 2006. * Krauss, Rolf. ''Das Ende der Amarnazeit'' (The End of the Amarna Period); 1978, Hildesheim * Miller, J. ''Amarna Age Chronology and the Identity of Nibhururiya'' in ''Altoriental. Forsch.'' 34 (2007) * Moran, William L. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992 * Murnane, W. ''Ancient Egyptian Coregencies'' (1977) * Murnane, W. ''Texts from the Amarna Period'' (1995) * Newberry, P. E. 'Appendix III: Report on the Floral Wreaths Found in the Coffins of Tut.Ankh.Amen' in H. Carter, ''The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen Volume Two'' London: Cassell (1927) * O'Connor, D and Cline, E, (eds); ''Amenhotep III: perspectives on his reign'' (1998) University of Michigan Press * Pendlebury J., Samson, J. et al. ''City of Akhenaten, Part III'' (1951) * Petrie, W. M. Flinders; ''Tell el Amarna'' (1894) * Reeves, C.N. ''Akhenaten, Egypt's false Prophet'' (Thames and Hudson; 2001) * Reeves, C.N. ''The Valley of the Kings'' (Kegan Paul, 1990) * Reeves, C.N. ''The Complete Tutankhamun: The King – The Tomb – The Royal Treasure''. London: Thames and Hudson; 1990. * * Theis, Christoffer, ''"Der Brief der Königin Daḫamunzu an den hethitischen König Šuppiluliuma I im Lichte von Reisegeschwindigkeiten und Zeitabläufen"'', in Thomas R. Kämmerer (Hrsg.), ''Identities and Societies in the Ancient East-Mediterranean Regions.'' Comparative Approaches. Henning Graf Reventlow Memorial Volume (= AAMO 1, AOAT 390/1). Münster 2011, S. 301–331 * Wente, E. ''Who Was Who Among the Royal Mummies?'' (1995), Oriental Institute, Chicago {{Authority control 14th-century BC Pharaohs Pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt Historical negationism in ancient Egypt Akhenaten