Sir William Beveridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

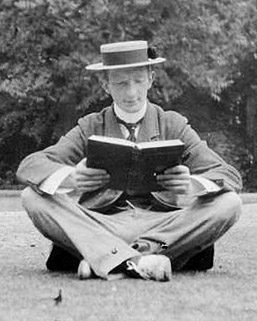

William Henry Beveridge, 1st Baron Beveridge, (5 March 1879 – 16 March 1963) was a British economist and

Beveridge, the eldest son of Henry Beveridge, an

Beveridge, the eldest son of Henry Beveridge, an

After leaving university, Beveridge initially became a lawyer. He became interested in the social services and wrote about the subject for the ''

After leaving university, Beveridge initially became a lawyer. He became interested in the social services and wrote about the subject for the ''

Three years later,

Three years later,

Later in 1944, Beveridge, who had recently joined the

Later in 1944, Beveridge, who had recently joined the

Beveridge married the mathematician

Beveridge married the mathematician

online

(

Prices and Wages in England from the Twelfth to the Nineteenth Century

', 1939. * '' Social Insurance and Allied Services'', 1942. (The

William Beveridge's archives are held at the London School of Economics.

Photographs of William Beveridge held by LSE Archives

*

online

* Hills, John et al. eds. ''Beveridge and Social Security: an International Retrospective'' (1994) * Robertson, David Brian. "Policy entrepreneurs and policy divergence: John R. Commons and William Beveridge." ''Social Service Review'' 62.3 (1988): 504–531. * Sugita, Yoneyuki. "The Beveridge Report and Japan." ''Social work in public health'' 29.2 (2014): 148–161. * Whiteside, Noel. "The Beveridge Report and its implementation: A revolutionary project?." ''Histoire@ Politique'' 3 (2014): 24–37

online

Sir William Beveridge Foundation

* Spartacus Educational o

an

Full text of the report

BBC information

BBC Radio 4, Great Lives – Downloadable 30 minute discussion of William Beveridge

Catalogue of William Beveridge's papers at the London School of Economics (LSE Archives)

Cataloguing the Beveridge papers at LSE Archives

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Beveridge, William 1879 births 1963 deaths Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Alumni of University College, Oxford British agnostics British humanists British economists British reformers British social liberals Civil servants in the Board of Trade English people of Scottish descent Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Liberal Party (UK) hereditary peers Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Masters of University College, Oxford People educated at Charterhouse School People associated with the London School of Economics Permanent Secretaries of the Ministry of Food Presidents of the Royal Statistical Society British social reformers UK MPs 1935–1945 UK MPs who were granted peerages Vice-Chancellors of the University of London Barons created by George VI

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

politician who was a progressive and social reformer who played a central role in designing the British welfare state. His 1942 report ''Social Insurance and Allied Services'' (known as the Beveridge Report

The Beveridge Report, officially entitled ''Social Insurance and Allied Services'' (Command paper, Cmd. 6404), is a government report, published in November 1942, influential in the founding of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It was draft ...

) served as the basis for the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equita ...

put in place by the Labour government elected in 1945.

He built his career as an expert on unemployment insurance

Unemployment benefits, also called unemployment insurance, unemployment payment, unemployment compensation, or simply unemployment, are payments made by authorized bodies to unemployed people. In the United States, benefits are funded by a comp ...

. He served on the Board of Trade as Director of the newly created labour exchange

An employment agency is an organization which matches employers to employees. In developed countries, there are multiple private businesses which act as employment agencies and a publicly-funded employment agency.

Public employment agencies

One ...

s, and later as Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Food

An agriculture ministry (also called an) agriculture department, agriculture board, agriculture council, or agriculture agency, or ministry of rural development) is a ministry charged with agriculture. The ministry is often headed by a minister ...

. He was Director of the London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

from 1919 until 1937, when he was elected Master of University College, Oxford

University College (in full The College of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, colloquially referred to as "Univ") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It has a claim to being the oldest college of the unive ...

.

Beveridge published widely on unemployment and social security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

, his most notable works being: ''Unemployment: A Problem of Industry'' (1909), ''Planning Under Socialism'' (1936), ''Full Employment in a Free Society

''Full Employment in a Free Society'' (1944) is a book by William Beveridge, author of the Beveridge Report. It was first published in the UK by Allen & Unwin.

Overview

The book begins with the thesis that because individual employers are not ca ...

'' (1944), ''Pillars of Security'' (1943), ''Power and Influence'' (1953) and ''A Defence of Free Learning'' (1959). He was elected in a 1944 by-election as a Liberal MP (for Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census reco ...

); following his defeat in the 1945 general election

The following elections occurred in the year 1945.

Africa

* 1945 South-West African legislative election

Asia

* 1945 Indian general election

Australia

* 1945 Fremantle by-election

Europe

* 1945 Albanian parliamentary election

* 1945 Bulgarian ...

, he was elevated to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

where he served as the leader of the Liberal peers.

Early life and education

Beveridge, the eldest son of Henry Beveridge, an

Beveridge, the eldest son of Henry Beveridge, an Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million p ...

officer and District Judge, and scholar Annette Ackroyd, was born in Rangpur, British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

(now Rangpur, Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

), on 5 March 1879.

Beveridge's mother had, with Elizabeth Malleson

Elizabeth Malleson (''née'' Whitehead; 1828–1916) was an English educationalist, suffragist and activist for women's education and rural nursing.

Life

Elizabeth Whitehead was born into a Unitarian family in Chelsea, Malleson was the first chil ...

, founded the Working Women's College in Queen Square, London

Queen Square is a garden square in the Bloomsbury district of central London. Many of its buildings are associated with medicine, particularly neurology.

Construction

Queen Square was originally constructed between 1716 and 1725. It was formed ...

in 1864. She met and married Henry Beveridge in Calcutta where she had gone in 1873 to open a school for Indian girls. William Beveridge was educated at Charterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

Londo ...

, a leading public school near the market town of Godalming in Surrey, followed by Balliol College

Balliol College () is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. One of Oxford's oldest colleges, it was founded around 1263 by John I de Balliol, a landowner from Barnard Castle in County Durham, who provided the ...

at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

, where he studied Mathematics and Classics, obtaining a first class degree

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

in both. He later studied law.Jose Harris, ''William Beveridge: a biography'' (1997) pp 43-78.

While Beveridge's mother had been a member of the Stourbridge

Stourbridge is a market town in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley in the West Midlands, England, situated on the River Stour. Historically in Worcestershire, it was the centre of British glass making during the Industrial Revolution. The ...

Unitarian community, his father was an early humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

and positivist activist and "an ardent disciple" of the French philosopher Auguste Comte. Comte's ideas of a secular religion of humanity

Religion of Humanity (from French ''Religion de l'Humanité'' or '' église positiviste'') is a secular religion created by Auguste Comte (1798–1857), the founder of positivist philosophy. Adherents of this religion have built chapels of Huma ...

were a prominent influence in the household and would exert a lasting influence on Beveridge's thinking. Beveridge himself became a " materialist agnostic", in his words.Jose Harris, ''William Beveridge: a biography'' (1997) pp 1, 323.

Life and career

After leaving university, Beveridge initially became a lawyer. He became interested in the social services and wrote about the subject for the ''

After leaving university, Beveridge initially became a lawyer. He became interested in the social services and wrote about the subject for the ''Morning Post

''The Morning Post'' was a conservative daily newspaper published in London from 1772 to 1937, when it was acquired by ''The Daily Telegraph''.

History

The paper was founded by John Bell. According to historian Robert Darnton, ''The Morning Po ...

'' newspaper. His interest in the causes of unemployment began in 1903 when he worked at Toynbee Hall, a settlement house

The settlement movement was a reformist social movement that began in the 1880s and peaked around the 1920s in United Kingdom and the United States. Its goal was to bring the rich and the poor of society together in both physical proximity and s ...

in London. There he worked closely with Sidney Webb and Beatrice Webb and was influenced by their theories of social reform, becoming active in promoting old age pensions

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

, free school meals

A school meal or school lunch (also known as hot lunch, a school dinner, or school breakfast) is a meal provided to students and sometimes teachers at a school, typically in the middle or beginning of the school day. Countries around the world ...

, and campaigning for a national system of labour exchange

An employment agency is an organization which matches employers to employees. In developed countries, there are multiple private businesses which act as employment agencies and a publicly-funded employment agency.

Public employment agencies

One ...

s.

In 1908, now considered to be Britain's leading authority on unemployment insurance

Unemployment benefits, also called unemployment insurance, unemployment payment, unemployment compensation, or simply unemployment, are payments made by authorized bodies to unemployed people. In the United States, benefits are funded by a comp ...

, he was introduced by Beatrice Webb to Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, who had recently been promoted to the Cabinet as President of the Board of Trade. Churchill invited Beveridge to join the Board of Trade, and he organised the implementation of the national system of labour exchanges and National Insurance

National Insurance (NI) is a fundamental component of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It acts as a form of social security, since payment of NI contributions establishes entitlement to certain state benefits for workers and their fami ...

to combat unemployment and poverty. During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

he was involved in mobilising and controlling manpower. After the war, he was knighted and made permanent secretary to the Ministry of Food

An agriculture ministry (also called an) agriculture department, agriculture board, agriculture council, or agriculture agency, or ministry of rural development) is a ministry charged with agriculture. The ministry is often headed by a minister ...

.

In 1919 he left the civil service to become director of the London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

. Over the next few years he served on several commissions and committees on social policy. He was so highly influenced by the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. T ...

socialists – in particular by Beatrice Webb, with whom he worked on the 1909 ''Poor Laws'' report – that he could be considered one of their number. He published academic economic works including his early work on unemployment (1909). The Fabians made him a director of the LSE in 1919, a post he retained until 1937. During his time as Director, he jousted with Edwin Cannan

Edwin Cannan (3 February 1861, Funchal, Madeira – 8 April 1935, Bournemouth), the son of David Cannan and artist Jane Cannan, was a British economist and historian of economic thought. He was a professor at the London School of Economics from 1 ...

and Lionel Robbins

Lionel Charles Robbins, Baron Robbins, (22 November 1898 – 15 May 1984) was a British economist, and prominent member of the economics department at the London School of Economics (LSE). He is known for his leadership at LSE, his proposed def ...

, who were trying to steer the LSE away from its Fabian roots. From 1929 he led the International scientific committee on price history The International scientific committee on price history was created in 1929 by William Beveridge and Edwin Francis Gay thanks to a five-years grant of the Rockefeller Foundation. The national representatives were William Beveridge for Great Britain, ...

, contributing a large historical study, ''Prices and Wages in England from the Twelfth to the Nineteenth Century'' (1939).

In 1933 he helped set up the Academic Assistance Council. This helped prominent academics who had been dismissed from their posts on grounds of race, religion or political position to escape Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

persecution. In 1937 Beveridge was appointed Master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

of University College, Oxford

University College (in full The College of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, colloquially referred to as "Univ") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It has a claim to being the oldest college of the unive ...

.

Wartime work

Three years later,

Three years later, Ernest Bevin

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour Party politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–194 ...

, Minister of Labour in the wartime National government, invited Beveridge to take charge of the Welfare department of his Ministry. Beveridge refused, but declared an interest in organising British manpower in wartime (Beveridge had come to favour a strong system of centralised planning). Bevin was reluctant to let Beveridge have his way but did commission him to work on a relatively unimportant manpower survey from June 1940 and so Beveridge became a temporary civil servant. Neither Bevin nor the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry Sir Thomas Phillips liked working with Beveridge as both found him conceited.Paul Addison, ''The Road to 1945'', Jonathan Cape, 1975, p. 117.

His work on manpower culminated in his chairmanship of the Committee on Skilled Men in the Services which reported to the War Cabinet in August and October 1941. Two recommendations of the committee were implemented: Army recruits were enlisted for their first six weeks into the General Service Corps

The General Service Corps (GSC) is a corps of the British Army.

Role

The role of the corps is to provide specialists, who are usually on the Special List or General List. These lists were used in both World Wars for specialists and those not allo ...

, so that their subsequent posting could take account of their skills and the Army's needs; and the Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers was created.

Report on social insurance and views on full employment

An opportunity for Bevin to ease Beveridge out presented itself in May 1941 when Minister of Health Ernest Brown announced the formation of a committee of officials to survey existing social insurance and allied services, and to make recommendations. Although Brown had made the announcement, the inquiry had largely been urged by Minister without PortfolioArthur Greenwood

Arthur Greenwood, (8 February 1880 – 9 June 1954) was a British politician. A prominent member of the Labour Party from the 1920s until the late 1940s, Greenwood rose to prominence within the party as secretary of its research department f ...

, and Bevin suggested to Greenwood making Beveridge chairman of the committee. Beveridge, at first uninterested and seeing the committee as a distraction from his work on manpower, accepted only reluctantly. Paul Addison, "The Road to 1945", Jonathan Cape, 1975, p. 169.

The report to Parliament on '' Social Insurance and Allied Services'' was published in November 1942. It proposed that all people of working age

Working age is the range of ages at which people are typically engaged in either paid or unpaid work. It typically sits between the ages of adolescence and retirement

Retirement is the withdrawal from one's position or occupation or from one' ...

should pay a weekly national insurance

National Insurance (NI) is a fundamental component of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It acts as a form of social security, since payment of NI contributions establishes entitlement to certain state benefits for workers and their fami ...

contribution. In return, benefits would be paid to people who were sick, unemployed, retired or widowed. Beveridge argued that this system would provide a minimum standard of living "below which no one should be allowed to fall". It recommended that the government should find ways of fighting the "five giants on the road of reconstruction" of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. Beveridge included as one of three fundamental assumptions the fact that there would be a National Health Service of some sort, a policy already being worked on in the Ministry of Health.Paul Addison, "The Road to 1945", Jonathan Cape, 1975, pp. 169–70.

Beveridge's arguments were widely accepted. He appealed to conservatives and other sceptics by arguing that welfare institutions would increase the competitiveness of British industry in the post-war period, not only by shifting labour costs like healthcare and pensions out of corporate

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and r ...

ledgers and onto the public account but also by producing healthier, wealthier and thus more motivated and productive workers who would also serve as a great source of demand for British goods.

Beveridge saw full employment (defined as unemployment of no more than 3%) as the pivot of the social welfare programme he expressed in the 1942 report. ''Full Employment in a Free Society

''Full Employment in a Free Society'' (1944) is a book by William Beveridge, author of the Beveridge Report. It was first published in the UK by Allen & Unwin.

Overview

The book begins with the thesis that because individual employers are not ca ...

'', written in 1944 expressed the view that it was "absurd" to "look to individual employers for maintenance of demand and full employment." These things must be "undertaken by the State under the supervision and pressure of democracy." Measures for achieving full-employment might include Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

-style fiscal regulation, direct control of manpower, and state control of the means of production. The impetus behind Beveridge's thinking was social justice

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, Equal opportunity, opportunities, and Social privilege, privileges within a society. In Western Civilization, Western and Culture of Asia, Asian cultures, the concept of social ...

, and the creation of an ideal new society after the war. He believed that the discovery of objective socio-economic laws could solve the problems of society.

Later career

Later in 1944, Beveridge, who had recently joined the

Later in 1944, Beveridge, who had recently joined the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

, was elected to the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

in a by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

to succeed George Charles Grey, who had died on the battlefield in Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, France, on the first day of Operation Bluecoat on 30 July 1944. Beveridge briefly served as Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for the constituency of Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census reco ...

, during which time he was prominent in the Radical Action group, which called for the party to withdraw from the war-time electoral pact

The war-time electoral pact was an electoral pact established by the member parties of the UK coalition governments in the First World War, and re-established in the Second World War. Under the pact, in the event of a by-election only the party whi ...

and adopt more radical policies. However, he lost his seat at the 1945 general election

The following elections occurred in the year 1945.

Africa

* 1945 South-West African legislative election

Asia

* 1945 Indian general election

Australia

* 1945 Fremantle by-election

Europe

* 1945 Albanian parliamentary election

* 1945 Bulgarian ...

, when he was defeated by the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

candidate, Robert Thorp, by a majority of 1,962 votes.

Clement Attlee and the Labour Party defeated Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

's Conservative Party in that election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

and the new Labour Government began the process of implementing Beveridge's proposals that provided the basis of the modern Welfare State. Attlee announced he would introduce the Welfare State outlined in the 1942 Beveridge Report. This included the establishment of a National Health Service in 1948 with taxpayer funded medical treatment for all. A national system of benefits was also introduced to provide "social security" so that the population would be protected from the "cradle to the grave". The new system was partly built upon the National Insurance scheme set up by then- Chancellor of the Exchequer and future Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister i ...

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

in 1911.

In 1946, Beveridge was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Beveridge, of Tuggal in the County of Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

, and eventually became leader of the Liberal Party in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

. He was the author of ''Power and Influence'' (1953). He was the President of the charity Attend (then the National Association of Leagues of Hospital Friends) from 1952 to 1962.

Eugenics

Beveridge was a member of the Eugenics Society, which promoted the study of methods to 'improve' the human race by controlling reproduction. In 1909, he proposed that men who could not work should be supported by the state "but with complete and permanent loss of all citizen rights – including not only the franchise but civil freedom and fatherhood." Whilst director of the London School of Economics, Beveridge attempted to create a Department of Social Biology. Though never fully established,Lancelot Hogben

Lancelot Thomas Hogben FRS FRSE (9 December 1895 – 22 August 1975) was a British experimental zoologist and medical statistician. He developed the African clawed frog ''(Xenopus laevis)'' as a model organism for biological research in his ear ...

, a fierce anti-eugenicist, was named its chair. Former LSE director John Ashworth John Ashworth may refer to:

* John Ashworth (cricketer) (1850–1901), English cricketer

* John Ashworth (footballer), English professional footballer

* John Ashworth (judge) (1906–1975), England judge and barrister

*John Ashworth (preacher) (181 ...

speculated that discord between those in favour and those against the serious study of eugenics led to Beveridge's departure from the school in 1937.

In the 1940s, Beveridge credited the Eugenics Society with promoting the children's allowance, which was incorporated into his 1942 report. However, whilst he held views in support of eugenics, he did not believe the report had any overall "eugenic value". Professor Danny Dorling said that "there is not even the faintest hint" of eugenic thought in the report.

Dennis Sewell states that "On the day the House of Commons met to debate the Beveridge Report in 1943, its author slipped out of the gallery early in the evening to address a meeting of the Eugenics Society at the Mansion House. ... His report he was keen to reassure them, was eugenic in intent and would prove so in effect. ... The idea of child allowances had been developed within the society with the twin aims of encouraging the educated professional classes to have more children than they currently did and, at the same time, to limit the number of children born to poor households. For both effects to be properly stimulated, the allowance needed to be graded: middle-class parents receiving more generous payments than working-class parents. ... The Home Secretary had that very day signalled that the government planned a flat rate of child allowance. But Beveridge, alluding to the problem of an overall declining birth rate, argued that even the flat rate would be eugenic. Nevertheless, he held out hope for the purists." 'Sir William made it clear that it was in his view not only possible but desirable that graded family allowance schemes, applicable to families in the higher income brackets, be administered concurrently with his flat rate scheme,' reported the '' Eugenics Review''.

Personal life

Beveridge married the mathematician

Beveridge married the mathematician Janet Philip

Janet Thomson Philip (26 November 1876 – 25 April 1959), known as Jessy Philip, Jessy Mair and later Janet Beveridge, was a member of the third cohort of female students to study at the University of St Andrews and was School Secretary at the ...

, daughter of William Philip and widow of David Mair, in 1942. They had worked together in the civil service and at LSE, and she was instrumental in the drafting and publicising of the Beveridge Report.

He died at his home on 16 March 1963, aged 84, and was buried in Thockrington churchyard, on the Northumbrian moors. His barony became extinct upon his death. His last words were "I have a thousand things to do".

Commemoration

Beveridge Street in theChristchurch Central City

Christchurch Central City or Christchurch City Centre is the geographical centre and the heart of Christchurch, New Zealand. It is defined as the area within the Four Avenues (Bealey Avenue, Fitzgerald Avenue, Moorhouse Avenue and Deans Avenue ...

was named for William Beveridge. It was one of 120 streets that were renamed in 1948 by Peter Fraser

Peter Fraser (; 28 August 1884 – 12 December 1950) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 24th prime minister of New Zealand from 27 March 1940 until 13 December 1949. Considered a major figure in the history of the New Zealand La ...

's Labour Government of New Zealand.

In November 2018, English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

unveiled a blue plaque commemorating Beveridge at 27 Bedford Gardens in Campden Hill

Campden Hill is a hill in Kensington, West London, bounded by Holland Park Avenue on the north, Kensington High Street on the south, Kensington Palace Gardens on the east and Abbotsbury Road on the west. The name derives from the former ''Campden ...

, London W8 7EF where he lived from 1914 until 1921.

University College, Oxford

University College (in full The College of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford, colloquially referred to as "Univ") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It has a claim to being the oldest college of the unive ...

's society for students studying and tutors involved in the study of Philosophy, Politics and Economics was recently renamed the Beveridge Society in his honour.

Works

* ''Unemployment: A problem of industry'', 1909online

(

Archive.org

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

)

* 'Wages in the Winchester Manors', ''Economic History Review'', Vol. VII, 1936–37.

* Prices and Wages in England from the Twelfth to the Nineteenth Century

', 1939. * '' Social Insurance and Allied Services'', 1942. (The

Beveridge Report

The Beveridge Report, officially entitled ''Social Insurance and Allied Services'' (Command paper, Cmd. 6404), is a government report, published in November 1942, influential in the founding of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It was draft ...

)

* ''The Pillars of Security and Other War-Time Essays and Addresses'', 1943, republished 2014.

* ''Full Employment in a Free Society

''Full Employment in a Free Society'' (1944) is a book by William Beveridge, author of the Beveridge Report. It was first published in the UK by Allen & Unwin.

Overview

The book begins with the thesis that because individual employers are not ca ...

'', 1944.

* ''The Economics of Full Employment'', 1944.

* ''Why I am a Liberal'', 1945.

* ''The Price of Peace'', 1945.

* ''Power and Influence'', 1953.

* "''India Called Them''," George Allen & Unwin, 1947

* ''Plan for Britain: A Collection of Essays prepared for the Fabian Society'' by G. D. H. Cole, Aneurin Bevan, Jim Griffiths, L. F. Easterbrook, Sir William Beveridge, and Harold J. Laski (Not illustrated with 127 text pages).Detail taken from ''Plan for Britain'' published by George Routledge with a date of 1943 and no ISBN

* 'Westminster Wages in the Manorial Era', ''Economic History Review'', 2nd Series, Vol. VIII, 1955.

See also

* Aneurin Bevan, Clement Attlee's Health Minister *Beveridge curve

A Beveridge curve, or UV curve, is a graphical representation of the relationship between unemployment and the job vacancy rate, the number of unfilled jobs expressed as a proportion of the labour force. It typically has vacancies on the vertical ...

– the relationship between unemployment and the job vacancy rate

*List of liberal theorists

Individual contributors to classical liberalism and political liberalism are associated with philosophers of the Enlightenment. Liberalism as a specifically named ideology begins in the late 18th century as a movement towards self-government and ...

* List of British university chancellors and vice-chancellors

This following is a current list of the chancellors, vice-chancellors and visitors of universities in the United Kingdom. In most cases, the chancellor is a ceremonial head, while the vice-chancellor is chief academic officer and chief executi ...

* List of United Kingdom MPs with the shortest service

List of United Kingdom MPs with the shortest service is an annotated list of the Members of the United Kingdom Parliament since 1900 having total service of less than 365 days.

''Nominal service'' is the number of days elapsed between the Decla ...

* List of Vice-Chancellors of the University of London

Resources

* Jose Harris, ''William Beveridge: A Biography,''Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1997. .

* Julien Demade, ''Produire un fait scientifique. Beveridge et le Comité international d'histoire des prix'', Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2018. .

William Beveridge's archives are held at the London School of Economics.

Photographs of William Beveridge held by LSE Archives

*

Donald Markwell

Donald John Markwell (born 19 April 1959) is an Australian social scientist, who has been described as a "renowned Australian educational reformer". He was appointed Head of St Mark's College, Adelaide, from November 2019. He was Senior Adviser ...

, ''John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace'', Oxford University Press, 2006.

References

Further reading

* Addison, Paul. ''The Road To 1945: British Politics and the Second World War'' (1977) pp 211–28. * Harris, Jose. ''William Beveridge: a biography'' (1997online

* Hills, John et al. eds. ''Beveridge and Social Security: an International Retrospective'' (1994) * Robertson, David Brian. "Policy entrepreneurs and policy divergence: John R. Commons and William Beveridge." ''Social Service Review'' 62.3 (1988): 504–531. * Sugita, Yoneyuki. "The Beveridge Report and Japan." ''Social work in public health'' 29.2 (2014): 148–161. * Whiteside, Noel. "The Beveridge Report and its implementation: A revolutionary project?." ''Histoire@ Politique'' 3 (2014): 24–37

online

Primary sources

* Williams, Ioan, and Karel Williams, eds. ''A Beveridge Reader'' (2014); (Works of William H. Beveridge).External links

*Sir William Beveridge Foundation

* Spartacus Educational o

an

Full text of the report

BBC information

BBC Radio 4, Great Lives – Downloadable 30 minute discussion of William Beveridge

Catalogue of William Beveridge's papers at the London School of Economics (LSE Archives)

Cataloguing the Beveridge papers at LSE Archives

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Beveridge, William 1879 births 1963 deaths Alumni of Balliol College, Oxford Alumni of University College, Oxford British agnostics British humanists British economists British reformers British social liberals Civil servants in the Board of Trade English people of Scottish descent Knights Commander of the Order of the Bath Liberal Party (UK) hereditary peers Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Masters of University College, Oxford People educated at Charterhouse School People associated with the London School of Economics Permanent Secretaries of the Ministry of Food Presidents of the Royal Statistical Society British social reformers UK MPs 1935–1945 UK MPs who were granted peerages Vice-Chancellors of the University of London Barons created by George VI