Sir Humphrey Gilbert on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 – 9 September 1583) was an

After the assassination of Shane O'Neill in 1567, he was appointed Governor of

After the assassination of Shane O'Neill in 1567, he was appointed Governor of

In 1570 Gilbert returned to England, where he married Anne Ager, daughter of John Ager (''alias'' Aucher, etc.) of Otterden, who bore him six sons and one daughter. In 1571 he was elected to the

In 1570 Gilbert returned to England, where he married Anne Ager, daughter of John Ager (''alias'' Aucher, etc.) of Otterden, who bore him six sons and one daughter. In 1571 he was elected to the

On arriving at the port of St John's, Gilbert was blockaded by the fishing fleet under the organisation of the port admiral (an Englishman) on account of piracy committed against a Portuguese vessel in 1582 by one of Gilbert's commanders. Once this resistance was overcome, Gilbert waved his letters patent about and, in a formal ceremony, took possession of Newfoundland (including the lands 200 leagues to the north and south) for the English crown on 5 August 1583. This involved the cutting of turf to symbolise the transfer of possession of the soil, according to the common law of England. The locals presented him with a dog, which he named Stella after the North Star. He claimed authority over the fish stations at St John's and levied tax on the fishermen from several countries who worked this rich sea near the

On arriving at the port of St John's, Gilbert was blockaded by the fishing fleet under the organisation of the port admiral (an Englishman) on account of piracy committed against a Portuguese vessel in 1582 by one of Gilbert's commanders. Once this resistance was overcome, Gilbert waved his letters patent about and, in a formal ceremony, took possession of Newfoundland (including the lands 200 leagues to the north and south) for the English crown on 5 August 1583. This involved the cutting of turf to symbolise the transfer of possession of the soil, according to the common law of England. The locals presented him with a dog, which he named Stella after the North Star. He claimed authority over the fish stations at St John's and levied tax on the fishermen from several countries who worked this rich sea near the  When ''Golden Hind'' came within hailing distance, the crew heard Gilbert cry out repeatedly, "We are as near to Heaven by sea as by land!" as he lifted his palm to the skies to illustrate his point. At midnight the frigate's lights were extinguished and the watch on ''Golden Hind'' cried out "the Generall was cast away". ''Squirrel'' had gone down with all hands. The frigate was devoured and swallowed up by the sea.

Coincidentally, Gilbert's distant cousin

When ''Golden Hind'' came within hailing distance, the crew heard Gilbert cry out repeatedly, "We are as near to Heaven by sea as by land!" as he lifted his palm to the skies to illustrate his point. At midnight the frigate's lights were extinguished and the watch on ''Golden Hind'' cried out "the Generall was cast away". ''Squirrel'' had gone down with all hands. The frigate was devoured and swallowed up by the sea.

Coincidentally, Gilbert's distant cousin

Charter to Sir Walter Raleigh: 1584

from the based in part from Gilbert's earlier patent; with this backing he undertook the Roanoke expeditions, the first sustained attempt by the English crown to establish colonies in North America.

* Gilbert was father to Ralegh Gilbert, who was to become second in command of the failed

Buried-FireAbyss

. * '' The Gate of Time'' (1966) by Philip José Farmer – Gilbert is not displaced forward in time but sidewise into an

Newfoundland voyage

– The Modern History Sourcebook

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gilbert, Humphrey English explorers Walter Raleigh 1530s births 1583 deaths People of British North America People of Elizabethan Ireland English MPs 1571 English MPs 1572–1583 Explorers of Canada People educated at Eton College People from Brixham Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Members of the Parliament of England for Plymouth People from Marldon

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

adventurer, explorer, member of parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

and soldier who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

and was a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America and the Plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, an ...

. He was a maternal half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebelli ...

and a cousin of Sir Richard Grenville

Sir Richard Grenville (15 June 1542 – 10 September 1591), also spelt Greynvile, Greeneville, and Greenfield, was an English privateer and explorer. Grenville was lord of the manors of Stowe, Cornwall and Bideford, Devon. He subsequently ...

.

Biography

Early life

Gilbert was the fifth son of Otho Gilbert of Compton, Greenway and Galmpton, all inDevon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

, by his wife Catherine Champernowne. His brothers Sir John Gilbert and Adrian Gilbert, and his half-brother

A sibling is a relative that shares at least one parent with the subject. A male sibling is a brother and a female sibling is a sister. A person with no siblings is an only child.

While some circumstances can cause siblings to be raised separa ...

s Carew Raleigh

:''This article concerns Sir Walter Raleigh's brother. For his namesake and nephew, Sir Walter's son, see Carew Raleigh (1605–1666)''

Sir Carew Raleigh or Ralegh (ca. 1550ca. 1625) was an English naval commander and politician who sat in the ...

and Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebelli ...

, were also prominent during the reigns of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

and King James VI and I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

. Catherine Champernowne was a niece of Kat Ashley

Katherine Astley (née Champernowne; circa 1502 – 18 July 1565), also known as Kat Astley, was the first close friend, governess, and Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Elizabeth I of England.

Sh ...

, Elizabeth's governess, who introduced her young kinsmen to the court. Gilbert's uncle, Sir Arthur Champernowne, involved him in the plantation of Ireland between 1566 and 1572.

Gilbert's mentor was Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586), Lord Deputy of Ireland, was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst, a prominent politician and courtier during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, from both of whom he received ...

. He was educated at Eton College

Eton College () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI of England, Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. i ...

and the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

, where he learned to speak French and Spanish and studied war and navigation. He went on to reside at the Inns of Chancery

The Inns of Chancery or ''Hospida Cancellarie'' were a group of buildings and legal institutions in London initially attached to the Inns of Court and used as offices for the clerks of chancery, from which they drew their name. Existing from a ...

in London in about 1560–1561.

Gilbert's Latin motto

A motto (derived from the Latin , 'mutter', by way of Italian , 'word' or 'sentence') is a sentence or phrase expressing a belief or purpose, or the general motivation or intention of an individual, family, social group, or organisation. M ...

es, ''Quid Non'' ("Why not?") and ''Mutare vel Timere Sperno'' ("I scorn to change or to fear"), indicate his chosen philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

.

Gilbert was present at the siege of Newhaven in Havre-de-Grâce (Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, very ...

), Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, where he was wounded in June 1563. By July 1566 he was serving in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

under the command of Sir Henry Sidney

Sir Henry Sidney (20 July 1529 – 5 May 1586), Lord Deputy of Ireland, was the eldest son of Sir William Sidney of Penshurst, a prominent politician and courtier during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, from both of whom he received ...

(then Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the representative of the monarch and head of the Irish executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and then the Kingdom of Ireland. He deputised prior to 1523 for the Viceroy of Ireland. The plural form is ' ...

) against Shane O'Neill, but was sent to England later in the year with dispatches for the Queen. (See Plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, an ...

and Tudor conquest of Ireland

The Tudor conquest (or reconquest) of Ireland took place under the Tudor dynasty, which held the Kingdom of England during the 16th century. Following a failed rebellion against the crown by Silken Thomas, the Earl of Kildare, in the 1530s, ...

). At that point he took the opportunity of presenting the Queen with his ''A Discourse of a Discoverie for a New Passage to Cataia'' (Cathay

Cathay (; ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which ...

) (published in revised form in 1576), treating of the exploration of a Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

by America to China.

Gilbert was described as "of higher stature than of the common sort, and of complexion cholerike". Certain contemporaries speculated that he was a pederast.

Military career in Ireland

After the assassination of Shane O'Neill in 1567, he was appointed Governor of

After the assassination of Shane O'Neill in 1567, he was appointed Governor of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

and served as a member of the Irish Parliament. At about this time he petitioned William Cecil, Queen Elizabeth's principal secretary, for a recall to England citing "for the recovery of my eyes", but his ambitions still rested in Ireland, and particularly in the southern province of Munster. In April 1569 he proposed the establishment of a presidency and council for the province, and pursued the notion of an extensive settlement around Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

(at the southwest tip of modern County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns a ...

), which was approved by the Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

council. At the same time, he was involved with Sidney and Sir Thomas Smith, the Secretary of State, in planning the Enterprise of Ulster, a large settlement in the east of the northern province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

, by Devonshire

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, ...

gentlemen.

Gilbert's actions in the south of Ireland played a significant part in the outbreak of the first of the Desmond Rebellions

The Desmond Rebellions occurred in 1569–1573 and 1579–1583 in the Irish province of Munster.

They were rebellions by the Earl of Desmond, the head of the Fitzmaurice/FitzGerald Dynasty in Munster, and his followers, the Geraldines an ...

. Sir Peter Carew

Sir Peter Carew (1514? – 27 November 1575) of Mohuns Ottery, Luppitt, Devon, was an English adventurer, who served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I of England and took part in the Tudor conquest of Ireland. His biography was written by h ...

(d.1575), his Devonshire kinsman, was pursuing a provocative, and somewhat far-fetched, claim to the inheritance of certain lands within the Butler

A butler is a person who works in a house serving and is a domestic worker in a large household. In great houses, the household is sometimes divided into departments with the butler in charge of the dining room, wine cellar, and pantries, pantry ...

territories in south Leinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of ...

. The 3rd Earl of Ormonde, a bosom companion of Queen Elizabeth's from childhood and head of the Butler dynasty

Butler ( ga, de Buitléir) is the name of a noble family whose members were, for several centuries, prominent in the administration of the Lordship of Ireland and the Kingdom of Ireland. They rose to their highest prominence as Dukes of Ormonde ...

, was absent in England, and the clash of Butler influence with the Carew claim created havoc.

Gilbert was eager to participate and, after Carew's seizure of the barony Barony may refer to:

* Barony, the peerage, office of, or territory held by a baron

* Barony, the title and land held in fealty by a feudal baron

* Barony (county division), a type of administrative or geographical division in parts of the British ...

of Idrone (in modern County Carlow

County Carlow ( ; ga, Contae Cheatharlach) is a Counties of Ireland, county located in the South-East Region, Ireland, South-East Region of Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. Carlow is the List of Irish counties by ...

) in the summer of 1569, he pushed westward with his forces across the River Blackwater and joined up with his kinsman to defeat Sir Edmund Butler, the Earl of Ormond's younger brother. Violence spread in a confusion from Leinster and across the province of Munster, when the Geraldines of Desmond, led by James FitzMaurice FitzGerald

James fitz Maurice FitzGerald (died 1579), called "fitz Maurice", was captain-general of Desmond while Gerald FitzGerald, 14th Earl of Desmond, was detained in England by Queen Elizabeth after the Battle of Affane in 1565. He led the first ...

, rose against the incursion.

Gilbert was then created Colonel by Lord Deputy Sidney and was charged with the pursuit of FitzGerald. The Geraldines were driven out of Kilmallock

Kilmallock () is a town in south County Limerick, Ireland, near the border with County Cork. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King's Castle (or King John's Castle). The remains of medieval walls which encircled the settlement are st ...

, but returned to lay siege to Gilbert, who drove off their superior force in a sally during which his horse was shot from under him and his buckler transfixed with a spear. After that initial success, he marched unopposed through Kerry and Connello, taking 30 to 40 castles.

During the three weeks of this campaign, all Irish were treated without quarter and put to the sword, including women and children. A gruesome spectacle was devised by Gilbert to cow the rebel supporters, utilising the decapitated

Decapitation or beheading is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is invariably fatal to humans and most other animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood, while all other organs are deprived of the i ...

heads of his Irish enemies:

Gilbert explicitly advocated the killing of Irish non-combatant women and others under the following rationale;

John Perrot

Sir John Perrot (7 November 1528 – 3 November 1592) served as lord deputy to Queen Elizabeth I of England during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. It was formerly speculated that he was an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, though the idea is re ...

used a similar practice at Kilmallock

Kilmallock () is a town in south County Limerick, Ireland, near the border with County Cork. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King's Castle (or King John's Castle). The remains of medieval walls which encircled the settlement are st ...

a few years later. Gilbert is also said to have sent Captain Apsley into Kerry to inspire terror.

Gilbert's attitude to the Irish may be captured in one quote from him, dated 13 November 1569: "These people are headstrong and if they feel the curb loosed but one link they will with bit

The bit is the most basic unit of information in computing and digital communications. The name is a portmanteau of binary digit. The bit represents a logical state with one of two possible values. These values are most commonly represente ...

in the teeth in one month run further out of the career of good order than they will be brought back in three months."

Once Ormond had returned from England and called in his brothers, the Geraldines found themselves outgunned. In December 1569, after one of the chief rebels had surrendered, Gilbert was knighted at the hands of Sidney in the ruined FitzMaurice camp, reputedly amid heaps of dead gallowglass

The Gallowglass (also spelled galloglass, gallowglas or galloglas; from ga, gallóglaigh meaning foreign warriors) were a class of elite mercenary warriors who were principally members of the Norse-Gaelic clans of Ireland between the mid 13t ...

warriors.

A month after Gilbert's return to England FitzMaurice retook Kilmallock

Kilmallock () is a town in south County Limerick, Ireland, near the border with County Cork. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King's Castle (or King John's Castle). The remains of medieval walls which encircled the settlement are st ...

with 120 soldiers, defeating the garrison and sacking the town for three days, leaving it "the abode of wolves". Three years later FitzMaurice surrendered.

Member of Parliament and adventurer

In 1570 Gilbert returned to England, where he married Anne Ager, daughter of John Ager (''alias'' Aucher, etc.) of Otterden, who bore him six sons and one daughter. In 1571 he was elected to the

In 1570 Gilbert returned to England, where he married Anne Ager, daughter of John Ager (''alias'' Aucher, etc.) of Otterden, who bore him six sons and one daughter. In 1571 he was elected to the Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advise ...

as a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

, Devon, and in 1572 for Queenborough

Queenborough is a town on the Isle of Sheppey in the Swale borough of Kent in South East England.

Queenborough is south of Sheerness. It grew as a port near the Thames Estuary at the westward entrance to the Swale where it joins the R ...

. Controversially he argued in favour of the crown prerogative in the matter of royal licenses for purveyance. In business

Business is the practice of making one's living or making money by producing or buying and selling products (such as goods and services). It is also "any activity or enterprise entered into for profit."

Having a business name does not separ ...

affairs, he involved himself in an alchemical

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

project with Smith, hoping for iron to be transmuted into copper and antimony, and lead into mercury.

By 1572 Gilbert had turned his attention to the Spanish Netherlands

Spanish Netherlands ( Spanish: Países Bajos Españoles; Dutch: Spaanse Nederlanden; French: Pays-Bas espagnols; German: Spanische Niederlande.) (historically in Spanish: ''Flandes'', the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the ...

, where he fought an unsuccessful campaign in support of the Dutch Sea beggars

Geuzen (; ; french: Les Gueux) was a name assumed by the confederacy of Calvinist Dutch nobles, who from 1566 opposed Spanish rule in the Netherlands. The most successful group of them operated at sea, and so were called Watergeuzen (; ; frenc ...

at the head of a force of 1,500 men, many of whom had deserted from Smith's aborted plantation in the Ards of Ulster. In the period 1572–1578 Gilbert settled down and devoted himself to writing. In 1573 he presented the Queen with a proposal for an academy in London, which was eventually put into effect by Sir Thomas Gresham with the establishment of Gresham College

Gresham College is an institution of higher learning located at Barnard's Inn Hall off Holborn in Central London, England. It does not enroll students or award degrees. It was founded in 1596 under the will of Sir Thomas Gresham, and hosts ove ...

. Gilbert also helped to set up the Society of the New Art with William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (13 September 15204 August 1598) was an English statesman, the chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, twice Secretary of State (1550–1553 and 1558–1572) and Lord High Treasurer from 1 ...

and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, (24 June 1532 – 4 September 1588) was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Dudley's youth was o ...

, both of whom maintained an alchemical laboratory in Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through ...

.

The rest of Gilbert's life was spent in a series of failed maritime expeditions, the financing of which exhausted his family fortune.

After receiving letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

on 11 June 1578, Gilbert set sail in November 1578 with a fleet of seven vessels from Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to ...

in Devon for North America. The fleet was scattered by storms and forced back to port some six months later. The only vessel to have penetrated the Atlantic to any great distance was the ''Falcon'' under Raleigh's command.

In the summer of 1579 William Drury, Lord Deputy of Ireland, commissioned Gilbert and Raleigh to attack James FitzMaurice Fitzgerald again by sea and land and to intercept a fleet expected to arrive from Spain with aid for the Irish. At this time Gilbert had three vessels under his command: the 250-ton ''Anne Ager'' (named after his wife), the ''Relief'', and the 10-ton '' Squirrell'', a small frigate notable for having completed the voyage to America and back within three months under the command of a captured Portuguese pilot.

Gilbert set sail in June 1579 after a spell of bad weather, and promptly got lost in fog and heavy rain off Land's End

Land's End ( kw, Penn an Wlas or ''Pedn an Wlas'') is a headland and tourist and holiday complex in western Cornwall, England, on the Penwith peninsula about west-south-west of Penzance at the western end of the A30 road. To the east of it is ...

, Cornwall, an incident which caused the Queen to doubt his seafaring ability. His fleet was then driven into the Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

and the Spanish soon slipped past and sailed into Dingle

Dingle ( Irish: ''An Daingean'' or ''Daingean Uí Chúis'', meaning "fort of Ó Cúis") is a town in County Kerry, Ireland. The only town on the Dingle Peninsula, it sits on the Atlantic coast, about southwest of Tralee and northwest of Kill ...

harbour, where they made their rendezvous with the Irish. In October Gilbert put into the port of Cobh

Cobh ( ,), known from 1849 until 1920 as Queenstown, is a seaport town on the south coast of County Cork, Ireland. With a population of around 13,000 inhabitants, Cobh is on the south side of Great Island in Cork Harbour and home to Ireland's ...

in Cork, where he delivered a terrible beating to a local gentleman, smashing him about the head with a sword. He then fell into a row with a local merchant, whom he murdered on the dockside.

Gilbert became one of the leading advocates for the then-mythical Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the ...

to Cathay

Cathay (; ) is a historical name for China that was used in Europe. During the early modern period, the term ''Cathay'' initially evolved as a term referring to what is now Northern China, completely separate and distinct from China, which ...

(China), a country written up in great detail by Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

in the 13th century for its abundance of riches. Gilbert made an elaborate case to counter the calls for a Northeast Passage

The Northeast Passage (abbreviated as NEP) is the Arctic shipping routes, shipping route between the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic and Pacific Ocean, Pacific Oceans, along the Arctic coasts of Norway and Russia. The western route through the islands o ...

to China. During the winter of 1566 he and his principal antagonist Anthony Jenkinson (who had sailed to Russia and crossed that country down to the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, often described as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia; east of the Caucasus, west of the broad steppe of Central A ...

) argued the pivotal question of polar routes before Queen Elizabeth. Gilbert claimed that any north-east passage was far too dangerous: "the air is so darkened with continual mists and fogs so near the pole that no man can well see either to guide his ship or direct his course." By logic and reason a north-west passage was assumed to exist, and Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

had discovered America with far less evidence; it was imperative for England to catch up, to settle in new lands and thus to challenge the Iberian powers. Gilbert's contentions won support and money was raised, chiefly by the London merchant Michael Lok

Michael Lok, also Michael Locke, (c.1532 – c.1621) was an English merchant and traveller, and the principal backer of Sir Martin Frobisher's voyages in search of the Northwest Passage.

Family

Michael Lok was born in Cheapside in London, by his ...

, for an expedition. The fearless Martin Frobisher

Sir Martin Frobisher (; c. 1535 – 22 November 1594) was an English seaman and privateer who made three voyages to the New World looking for the North-west Passage. He probably sighted Resolution Island near Labrador in north-eastern Canad ...

was appointed captain and left England in June 1576, but the quest for a north-west passage failed: Frobisher returned with a cargo of a black stone – which was found to be worthless – and a native Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

.

Newfoundland and death

It was assumed that Gilbert would be appointedPresident of Munster

The post of Lord President of Munster was the most important office in the English government of the Irish province of Munster from its introduction in the Elizabethan era for a century, to 1672, a period including the Desmond Rebellions in Munste ...

after the dismissal of Ormond as lord lieutenant of the province in the spring of 1581. At this time Gilbert was member of parliament for Queenborough

Queenborough is a town on the Isle of Sheppey in the Swale borough of Kent in South East England.

Queenborough is south of Sheerness. It grew as a port near the Thames Estuary at the westward entrance to the Swale where it joins the R ...

, Kent, but his attention was again drawn to North America, where he hoped to seize territory on behalf of the English crown.

The six-year exploration licence Gilbert had secured by letters patent from the crown in 1578 was on the point of expiring, when he succeeded in 1583 in raising significant sums from English Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

investors. The investors were constrained by penal laws in their own country, and loath to go into exile in hostile parts of Europe; the prospect of American settlement appealed to them, especially as Gilbert was proposing to seize some nine million acres (36,000 km2) around the river Norumbega

Norumbega, or Nurembega, is a legendary settlement in northeastern North America which was featured on many early maps from the 16th century until European colonization of the region. It was alleged that the houses had pillars of gold and the inh ...

, to be parcelled out under his authority (although to be held ultimately by the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differ ...

).

However, the Privy Council insisted that the investors pay recusancy

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

fines before departing, and Catholic clergy and Spanish agents worked to dissuade them from interfering in America. Shorn of his Catholic financing, Gilbert set sail with a fleet of five vessels in June 1583. One of the vessels – ''Bark Raleigh'', owned and commanded by Raleigh – turned back owing to lack of victuals. Gilbert's crews were made up of misfits, criminals and pirates, but in spite of the many problems caused by their lawlessness, the fleet reached Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

.

On arriving at the port of St John's, Gilbert was blockaded by the fishing fleet under the organisation of the port admiral (an Englishman) on account of piracy committed against a Portuguese vessel in 1582 by one of Gilbert's commanders. Once this resistance was overcome, Gilbert waved his letters patent about and, in a formal ceremony, took possession of Newfoundland (including the lands 200 leagues to the north and south) for the English crown on 5 August 1583. This involved the cutting of turf to symbolise the transfer of possession of the soil, according to the common law of England. The locals presented him with a dog, which he named Stella after the North Star. He claimed authority over the fish stations at St John's and levied tax on the fishermen from several countries who worked this rich sea near the

On arriving at the port of St John's, Gilbert was blockaded by the fishing fleet under the organisation of the port admiral (an Englishman) on account of piracy committed against a Portuguese vessel in 1582 by one of Gilbert's commanders. Once this resistance was overcome, Gilbert waved his letters patent about and, in a formal ceremony, took possession of Newfoundland (including the lands 200 leagues to the north and south) for the English crown on 5 August 1583. This involved the cutting of turf to symbolise the transfer of possession of the soil, according to the common law of England. The locals presented him with a dog, which he named Stella after the North Star. He claimed authority over the fish stations at St John's and levied tax on the fishermen from several countries who worked this rich sea near the Grand Banks of Newfoundland

The Grand Banks of Newfoundland are a series of underwater plateaus south-east of the island of Newfoundland on the North American continental shelf. The Grand Banks are one of the world's richest fishing grounds, supporting Atlantic cod, sword ...

.

Within weeks his fleet departed, having made no attempt to form a settlement, due to lack of supplies. During the return voyage, Gilbert insisted on sailing in his hardy old favourite, . He soon ordered a controversial change of course for the fleet. Owing to his obstinacy and disregard of the views of superior mariners, the ship ''Delight'' ran aground and soon sank with the loss of all but sixteen of its crew on one of the sandbars of Sable Island

Sable Island (french: île de Sable, literally "island of sand") is a small Canadian island situated southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and about southeast of the closest point of mainland Nova Scotia in the North Atlantic Ocean. The island ...

. ''Delight'' had been the largest remaining ship in the squadron (an unwise choice to lead in uncharted coastal waters) and contained most of the remaining supplies. Later in the voyage a sea monster

Sea monsters are beings from folklore believed to dwell in the sea and often imagined to be of immense size. Marine monsters can take many forms, including sea dragons, sea serpents, or tentacled beasts. They can be slimy and scaly and are o ...

was sighted, said to have resembled a lion with glaring eyes.

After discussions with Edward Hayes and William Cox, captain and master of ''Golden Hind'', Gilbert decided on 31 August to return. The fleet made good speed, clearing Cape Race

Cape Race is a point of land located at the southeastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland, in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Its name is thought to come from the original Portuguese name for this cape, "Raso", mean ...

after two days, and was soon clear of land. Gilbert had stepped on a nail on the ''Squirrel'' and, on 2 September, went aboard ''Golden Hind'' to have his foot bandaged and to discuss means of keeping the two little ships together on their Atlantic crossing. Gilbert refused to leave ''Squirrel'' and after a strong storm they had a spell of clear weather and made fair progress. Gilbert went aboard ''Golden Hind'' again, visited with Hayes, and insisted once more on returning to ''Squirrel'', even though Hayes insisted she was over-gunned and unsafe for sailing. Nearly away from Cape Race, near the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

, they encountered high waves of heavy seas, "breaking short and high Pyramid wise", said Hayes.

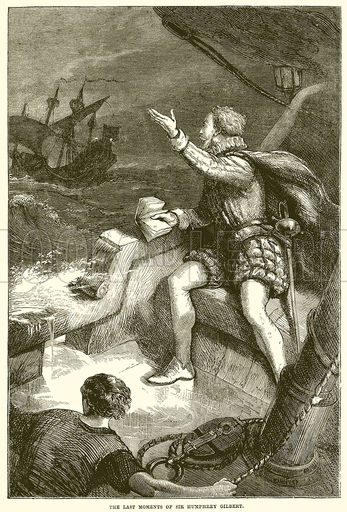

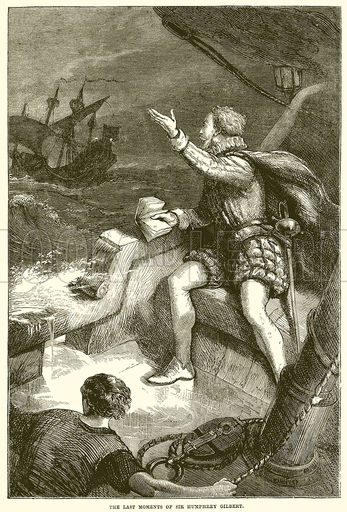

On 9 September, ''Squirrel'' was nearly overwhelmed but recovered. Despite the persuasions of others, who wished him to take to the larger vessel, Gilbert stayed put and was observed sitting in the stern of his frigate, reading a book.

When ''Golden Hind'' came within hailing distance, the crew heard Gilbert cry out repeatedly, "We are as near to Heaven by sea as by land!" as he lifted his palm to the skies to illustrate his point. At midnight the frigate's lights were extinguished and the watch on ''Golden Hind'' cried out "the Generall was cast away". ''Squirrel'' had gone down with all hands. The frigate was devoured and swallowed up by the sea.

Coincidentally, Gilbert's distant cousin

When ''Golden Hind'' came within hailing distance, the crew heard Gilbert cry out repeatedly, "We are as near to Heaven by sea as by land!" as he lifted his palm to the skies to illustrate his point. At midnight the frigate's lights were extinguished and the watch on ''Golden Hind'' cried out "the Generall was cast away". ''Squirrel'' had gone down with all hands. The frigate was devoured and swallowed up by the sea.

Coincidentally, Gilbert's distant cousin Richard Grenville

Sir Richard Grenville (15 June 1542 – 10 September 1591), also spelt Greynvile, Greeneville, and Greenfield, was an English privateer and explorer. Grenville was lord of the manors of Stowe, Cornwall and Bideford, Devon. He subsequently ...

would also die at sea off the Azores.

It is thought Gilbert's reading material was the ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island soc ...

'' of Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

, which contains the following passage: "He that hathe no grave is covered with the skye: and, the way to heaven out of all places is of like length and distance."

Legacy

Gilbert was part of a remarkable generation of Devonshire men, who combined the roles of adventurer, writer, soldier and mariner.A. L. Rowse

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on Elizabethan England and books relating to Cornwall.

Born in Cornwall and raised in modest circumstances, he was encour ...

wrote of him as,

an interesting psychological case, with the symptoms of disturbed personality that often go with men of mark, not at all the simple Elizabethan seaman of Froude's Victorian view. He was passionate and impulsive, a nature liable to violence and cruelty – as came out in his savage repression of rebels in Ireland – but also intellectual and visionary, a questing and original mind, with the personal magnetism that went with it. People were apt to be both attracted and repelled by him, to follow his leadership and yet be mistrustful of him.He was outstanding for his initiative and originality, if not for his successes, but it is in his efforts at colonisation that he had most influence. In Ireland Ulster and Munster were forcibly colonised by the English, and the American adventure did eventually flourish. The formality of his annexation of Newfoundland eventually achieved reality in 1610. Perhaps of more significance was the issuance of a

royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, b ...

to Raleigh in 1584,from the

Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the ...

Popham Colony

The Popham Colony—also known as the Sagadahoc Colony—was a short-lived English colonial settlement in North America. It was established in 1607 by the proprietary Plymouth Company and was located in the present-day town of Phippsburg, Ma ...

in Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

. One of his later relatives was the architect C. P. H. Gilbert

Charles Pierrepont Henry Gilbert (August 29, 1861 – October 25, 1952) was an American architect of the late-19th and early-20th centuries best known for designing townhouses and mansions.

Background and early life

Born in New York City, ...

.

* Gilbert Sound near Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland ...

was named after him by John Davis.

* At Memorial University of Newfoundland

Memorial University of Newfoundland, also known as Memorial University or MUN (), is a public university in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, based in St. John's, with satellite campuses in Corner Brook, elsewhere in Newfoundland and ...

, a court of the Burton's Pond Apartments are named "Gilbert Court" in his honour.

Popular culture

* '' Fire in the Abyss'' (1983) byStuart Gordon

Stuart Alan Gordon (August 11, 1947 – March 24, 2020) was an American filmmaker, theatre director, screenwriter, and playwright. Initially recognized for his provocative and frequently controversial work in experimental theatre, Gordon is ...

– Gilbert is the main character, and is transported four hundred years into the future"Horror Fiction Reviews – Fire in the Abyss (1983)" (book review), Horror.net: The Web's Deadliest Horror Network, 2006, ''Buried.com'Buried-FireAbyss

. * '' The Gate of Time'' (1966) by Philip José Farmer – Gilbert is not displaced forward in time but sidewise into an

alternate timeline

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, altern ...

Notes

Bibliography

* Payne, Edward John. (1893, 1900). ''Voyages of the Elizabethan Seamen to America''. 1, 2. * Ronald, Susan. (2007). ''The Pirate Queen: Queen Elizabeth I, her Pirate Adventurers, and the Dawn of Empire''. HarperCollins: New York. . *External links

Newfoundland voyage

– The Modern History Sourcebook

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Gilbert, Humphrey English explorers Walter Raleigh 1530s births 1583 deaths People of British North America People of Elizabethan Ireland English MPs 1571 English MPs 1572–1583 Explorers of Canada People educated at Eton College People from Brixham Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada) Members of the Parliament of England for Plymouth People from Marldon