Siege of Toulon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The siege of Toulon (29 August – 19 December 1793) was a military engagement that took place during the Federalist revolts of the

The troops of the army said to be of the " Carmagnoles", under the command of

The troops of the army said to be of the " Carmagnoles", under the command of  Despite the mutual dislike between Bonaparte and the chief of artillery, the young artillery officer was able to muster an artillery force that was worthy of a siege of Toulon and the fortresses that were quickly built by the British in its immediate environs. He was able to requisition equipment and cannon from the surrounding area. Guns were taken from Marseille, Avignon and the Army of Italy. The local populace, which was eager to prove its loyalty to the republic which it had recently rebelled against, was blackmailed into supplying the besieging force with animals and supplies. His activity resulted in the acquisition of 100 guns for the force. With the help of his friends, the deputies Saliceti and Augustin Robespierre, who held power of life and death, he was able to compel retired artillery officers from the area to re-enlist. The problem of manning the guns was not remedied by this solution alone, and under Bonaparte's intensive training he instructed much of the infantry in the practice of employing, deploying and firing the artillery that his efforts had recently acquired. However, in spite of this effort, Bonaparte was not as confident about this operation as was later his custom. The officers serving with him in the siege were incompetent, and he was becoming concerned about the needless delays due to these officers' mistakes. He was so concerned that he wrote a letter of appeal to the Committee of Public Safety requesting assistance. To deal with his superiors who were wanting in skill, he proposed the appointment of a general for command of the artillery, succeeding himself, so that "... (they could) command respect and deal with a crowd of fools on the staff with whom one has constantly to argue and lay down the law in order to overcome their prejudices and make them take steps which theory and practice alike have shown to be axiomatic to any trained officer of this corps".Correspondence of Napoleon I, Vol. I, No. 2, p. 12

After some reconnaissance, Bonaparte conceived a plan which envisaged the capture of the forts of l'Eguillette and Balaguier, on the hill of Cairo, which would then prevent passage between the small and large harbours of the port, so cutting maritime resupply, necessary for those under siege. Carteaux, reluctant, sent only a weak detachment under Major General Delaborde, which failed in its attempted conquest on 22 September. The allies now alerted, built "Fort Mulgrave", so christened in honour of the British commander, Henry Phipps, 1st Earl of Mulgrave, on the summit of the hill. It was supported by three smaller ones, called Saint-Phillipe, Saint-Côme, and Saint-Charles. The apparently impregnable collection was nicknamed, by the French, "Little Gibraltar".

Bonaparte was dissatisfied by the sole battery—called the "Mountain", positioned on the height of Saint-Laurent since 19 September. He established another, on the shore of Brégallion, called the "'' sans-culottes''". Hood attempted to silence it, without success, but the British fleet was obliged to harden its resolve along the coast anew, because of the high seabed of Mourillon and la Tour Royale. On the first of October, after the failure of General La Poype against the "Eastern Fort" of Faron, Bonaparte was asked to bombard the large fort of Malbousquet, whose fall would be required to enable the capture of the city. He therefore requisitioned artillery from all of the surrounding countryside, holding the power of fifty batteries of six cannon apiece. Promoted to Chief of Battalion on 19 October, he organised a grand battery, said to be "of the Convention", on the hill of Arènes and facing the fort, supported by those of the "Camp of the Republicans" on the hill of Dumonceau, by those of the "Farinière" on the hill of Gaux, and those of the "Poudrière" at Lagoubran.

On 11 November, Carteaux was dismissed and replaced by François Amédée Doppet, formerly a doctor, whose indecision would cause an attempted surprise against Fort Mulgrave to fail on the 16th. Aware of his own incompetence, he resigned. He was succeeded by a career soldier, Dugommier, who immediately recognized the virtue of Bonaparte's plan, and prepared for the capture of Little Gibraltar. On the 20th, as soon as he arrived, the battery "

Despite the mutual dislike between Bonaparte and the chief of artillery, the young artillery officer was able to muster an artillery force that was worthy of a siege of Toulon and the fortresses that were quickly built by the British in its immediate environs. He was able to requisition equipment and cannon from the surrounding area. Guns were taken from Marseille, Avignon and the Army of Italy. The local populace, which was eager to prove its loyalty to the republic which it had recently rebelled against, was blackmailed into supplying the besieging force with animals and supplies. His activity resulted in the acquisition of 100 guns for the force. With the help of his friends, the deputies Saliceti and Augustin Robespierre, who held power of life and death, he was able to compel retired artillery officers from the area to re-enlist. The problem of manning the guns was not remedied by this solution alone, and under Bonaparte's intensive training he instructed much of the infantry in the practice of employing, deploying and firing the artillery that his efforts had recently acquired. However, in spite of this effort, Bonaparte was not as confident about this operation as was later his custom. The officers serving with him in the siege were incompetent, and he was becoming concerned about the needless delays due to these officers' mistakes. He was so concerned that he wrote a letter of appeal to the Committee of Public Safety requesting assistance. To deal with his superiors who were wanting in skill, he proposed the appointment of a general for command of the artillery, succeeding himself, so that "... (they could) command respect and deal with a crowd of fools on the staff with whom one has constantly to argue and lay down the law in order to overcome their prejudices and make them take steps which theory and practice alike have shown to be axiomatic to any trained officer of this corps".Correspondence of Napoleon I, Vol. I, No. 2, p. 12

After some reconnaissance, Bonaparte conceived a plan which envisaged the capture of the forts of l'Eguillette and Balaguier, on the hill of Cairo, which would then prevent passage between the small and large harbours of the port, so cutting maritime resupply, necessary for those under siege. Carteaux, reluctant, sent only a weak detachment under Major General Delaborde, which failed in its attempted conquest on 22 September. The allies now alerted, built "Fort Mulgrave", so christened in honour of the British commander, Henry Phipps, 1st Earl of Mulgrave, on the summit of the hill. It was supported by three smaller ones, called Saint-Phillipe, Saint-Côme, and Saint-Charles. The apparently impregnable collection was nicknamed, by the French, "Little Gibraltar".

Bonaparte was dissatisfied by the sole battery—called the "Mountain", positioned on the height of Saint-Laurent since 19 September. He established another, on the shore of Brégallion, called the "'' sans-culottes''". Hood attempted to silence it, without success, but the British fleet was obliged to harden its resolve along the coast anew, because of the high seabed of Mourillon and la Tour Royale. On the first of October, after the failure of General La Poype against the "Eastern Fort" of Faron, Bonaparte was asked to bombard the large fort of Malbousquet, whose fall would be required to enable the capture of the city. He therefore requisitioned artillery from all of the surrounding countryside, holding the power of fifty batteries of six cannon apiece. Promoted to Chief of Battalion on 19 October, he organised a grand battery, said to be "of the Convention", on the hill of Arènes and facing the fort, supported by those of the "Camp of the Republicans" on the hill of Dumonceau, by those of the "Farinière" on the hill of Gaux, and those of the "Poudrière" at Lagoubran.

On 11 November, Carteaux was dismissed and replaced by François Amédée Doppet, formerly a doctor, whose indecision would cause an attempted surprise against Fort Mulgrave to fail on the 16th. Aware of his own incompetence, he resigned. He was succeeded by a career soldier, Dugommier, who immediately recognized the virtue of Bonaparte's plan, and prepared for the capture of Little Gibraltar. On the 20th, as soon as he arrived, the battery "

Lángara ordered Don Pedro Cotiella to take three boats into the arsenal to destroy the French fleet.

Lángara ordered Don Pedro Cotiella to take three boats into the arsenal to destroy the French fleet.  At 20:00 Captain Charles Hare brought the fire ship HMS ''Vulcan'' into the New Arsenal. Smith halted the ship across the row of anchored French ships of the line, and lit the fuses at 22:00. Hare was badly wounded by an early detonation as he attempted to leave his ship.Tracy, p. 42 Simultaneously, fire parties set alight the warehouses and stores ashore, including the mast house and the hemp and timber stores, creating an inferno across the harbour as ''Vulcan''s cannons fired a last salvo at the French positions on the shore.James, p. 78 With the fires spreading through the dockyards and New Arsenal, Smith began to withdraw. His force was illuminated by the flames, making an inviting target for the Republican batteries. As his boats passed the ''Iris'', however, the powder ship suddenly and unexpectedly exploded, blasting debris in a wide circle and sinking two of the British boats. On ''Britannia'' all of the crew survived, but the blast killed the master and three men on ''Union''.Mostert, p. 116

With the New Arsenal in flames, Smith realised that the Old Arsenal appeared intact; only a few small fires marked the Spanish effort to destroy the French ships anchored within. He immediately led ''Swallow'' back towards the arsenal but found that Republican soldiers had captured it intact, their heavy musketry driving him back.Tracy, p. 29 Instead he turned to two disarmed ships of the line, '' Héros'' and '' Thémistocle'', which lay in the inner roads as prison hulks. The French Republican prisoners on board had initially resisted British efforts to burn the ships, but with the evidence of the destruction in the arsenal before them they consented to be safely conveyed to shore as Smith's men set the empty hulls on fire.

At 20:00 Captain Charles Hare brought the fire ship HMS ''Vulcan'' into the New Arsenal. Smith halted the ship across the row of anchored French ships of the line, and lit the fuses at 22:00. Hare was badly wounded by an early detonation as he attempted to leave his ship.Tracy, p. 42 Simultaneously, fire parties set alight the warehouses and stores ashore, including the mast house and the hemp and timber stores, creating an inferno across the harbour as ''Vulcan''s cannons fired a last salvo at the French positions on the shore.James, p. 78 With the fires spreading through the dockyards and New Arsenal, Smith began to withdraw. His force was illuminated by the flames, making an inviting target for the Republican batteries. As his boats passed the ''Iris'', however, the powder ship suddenly and unexpectedly exploded, blasting debris in a wide circle and sinking two of the British boats. On ''Britannia'' all of the crew survived, but the blast killed the master and three men on ''Union''.Mostert, p. 116

With the New Arsenal in flames, Smith realised that the Old Arsenal appeared intact; only a few small fires marked the Spanish effort to destroy the French ships anchored within. He immediately led ''Swallow'' back towards the arsenal but found that Republican soldiers had captured it intact, their heavy musketry driving him back.Tracy, p. 29 Instead he turned to two disarmed ships of the line, '' Héros'' and '' Thémistocle'', which lay in the inner roads as prison hulks. The French Republican prisoners on board had initially resisted British efforts to burn the ships, but with the evidence of the destruction in the arsenal before them they consented to be safely conveyed to shore as Smith's men set the empty hulls on fire.

Engraved map plate "Siege of Toulon, 19 December 1793"

Atlas to Alison's History of Europe, by Alison & Johnston, published by William Blackwood and Sons in 1850. * {{Authority control French Revolutionary Wars 1793 in France Toulon

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

. It was undertaken by Republican forces against Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gov ...

rebels supported by Anglo-Spanish forces in the southern French city of Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

. It was during this siege that young Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

first won fame and promotion when his plan, involving the capture of fortifications above the harbour, was credited with forcing the city to capitulate and the Anglo-Spanish fleet to withdraw. The British siege of 1793 marked the first involvement of the Royal Navy with the French Revolution.

Background

After the arrest of the Girondist deputies on the 2 June 1793, there followed a series of insurrections within the French cities ofLyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

, Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

, Nîmes

Nîmes ( , ; oc, Nimes ; Latin: ''Nemausus'') is the prefecture of the Gard department in the Occitanie region of Southern France. Located between the Mediterranean Sea and Cévennes, the commune of Nîmes has an estimated population of ...

, and Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

known as Federalist revolts. In Toulon the revolutionaries evicted the existing Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

faction but were soon supplanted by the more numerous royalists. Upon the announcement of the recapture of Marseille and of the reprisals which had taken place there at the hands of the revolutionaries, the royalist forces, directed by the Baron d'Imbert, requested support from the Anglo-Spanish fleet. On the 28th of August, the British and Spanish commanders of the fleet, Admiral Sir Samuel Hood

Samuel Hood, 1st Viscount Hood (12 December 1724 – 27 January 1816) was an admiral in the Royal Navy. As a junior officer he saw action during the War of the Austrian Succession. While in temporary command of , he drove a French ship ashore in ...

(Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

) and Admiral Juan de Lángara ( Spanish Navy), responded with 13,000 troops of British, Spanish, Neapolitan

Neapolitan means of or pertaining to Naples, a city in Italy; or to:

Geography and history

* Province of Naples, a province in the Campania region of southern Italy that includes the city

* Duchy of Naples, in existence during the Early and Hig ...

and Piedmontese origin. Baron d'Imbert delivered the port of Toulon to the British navy. Toulon hoisted the royal flag, the fleur de lys, and d'Imbert declared the eight-year-old Louis XVII king of France on the first of October. This result produced a potentially mortal situation for the French republic, as the city had a key naval arsenal and was the base for 26 ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colu ...

(about one-third of the total available to the French Navy). Without this port, the French could not hope to challenge the Allies, and specifically the British, for control of the seas. In addition, Toulon's loss would send a dangerous signal to others preparing to revolt against the republic. Although France had a large army due to its ''levée en masse

''Levée en masse'' ( or, in English, "mass levy") is a French term used for a policy of mass national conscription, often in the face of invasion.

The concept originated during the French Revolutionary Wars, particularly for the period follo ...

'', the Republic could not easily rebuild its navy, which had been the third largest in Europe, if the Allies and Royalists destroyed or captured much of it. Both the strategic importance of the naval base and the prestige of the Revolution demanded that the French recapture Toulon.

Siege

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Jean François Carteaux, arrived at Toulon on 8 September, after those troops had recovered Avignon and Marseille, and then Ollioules. They joined up with the 6,000 men of the Alpine Maritime Army, commanded by General Jean François Cornu de La Poype, who had just taken La Valette-du-Var, and sought to take the forts of Mont Faron, which dominated the city to the East. They were reinforced by 3,000 sailors under the orders of Admiral de Saint Julien, who refused to serve the British with his chief, Jean-Honoré de Trogoff de Kerlessy. A further 5,000 soldiers under General La Poype were attached to the army to retake Toulon from the Army of Italy.Chandler 1966, p. 20

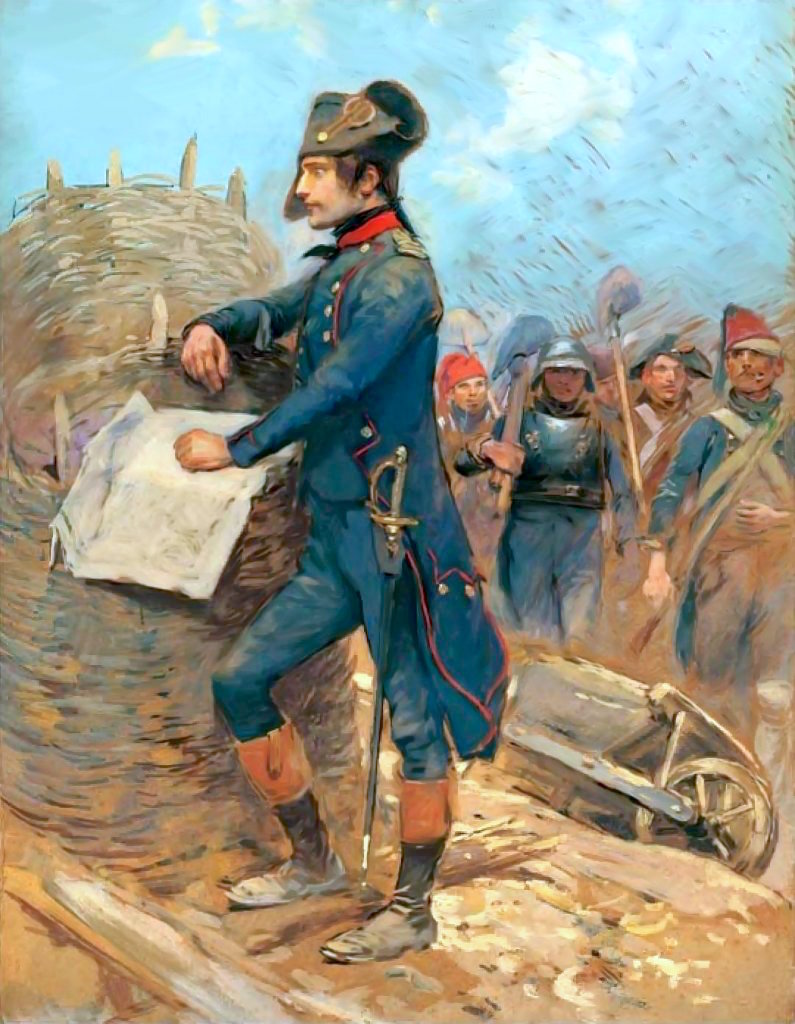

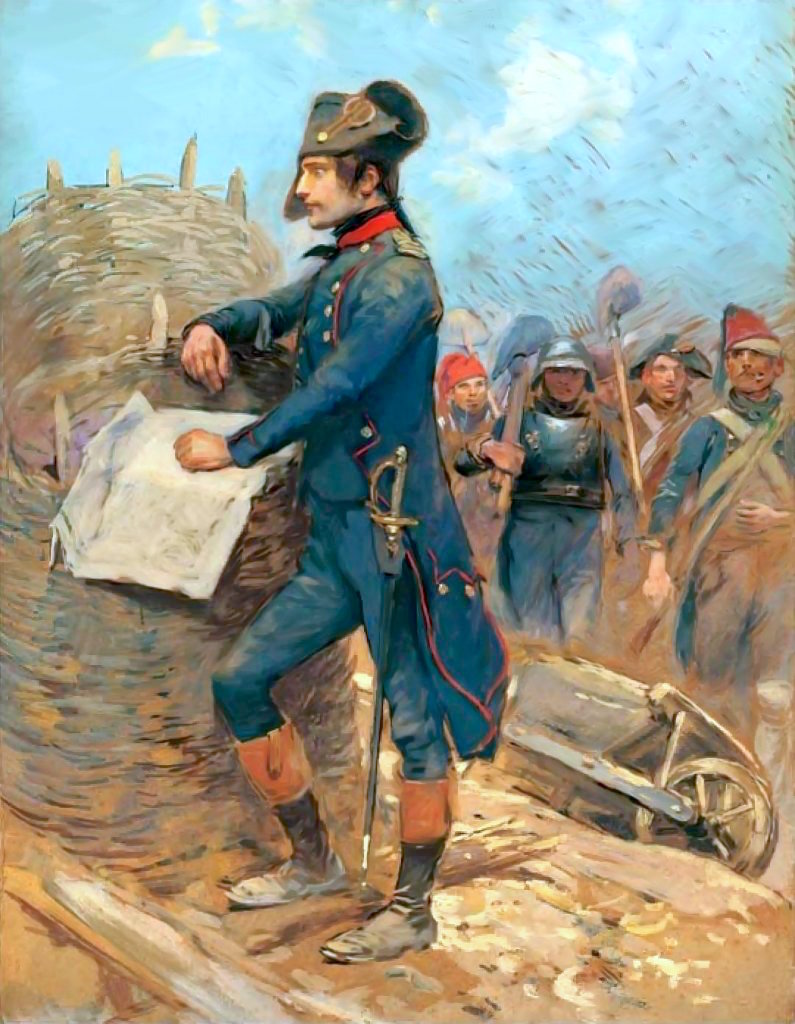

The Chief of Artillery, commander Elzéar Auguste Cousin de Dommartin, having been wounded at Ollioules, had the young captain Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

imposed upon him by the special representatives of the Convention and Napoleon's friends — Augustin Robespierre and Antoine Christophe Saliceti

Antoine Christophe Saliceti (baptised in the name of ''Antonio Cristoforo Saliceti'': ''Antoniu Cristufaru Saliceti'' in Corsican; 26 August 175723 December 1809) was a French politician and diplomat of the Revolution and First Empire.

Early c ...

. Bonaparte had been in the area escorting a convoy of powder wagons en route to Nice and had stopped in to pay his respects to his fellow Corsican, Saliceti. Bonaparte had been present in the army since the Avignon insurrection (July, 1793), and was imposed on Dommartin in this way despite the mutual antipathy between the two men.

Despite the mutual dislike between Bonaparte and the chief of artillery, the young artillery officer was able to muster an artillery force that was worthy of a siege of Toulon and the fortresses that were quickly built by the British in its immediate environs. He was able to requisition equipment and cannon from the surrounding area. Guns were taken from Marseille, Avignon and the Army of Italy. The local populace, which was eager to prove its loyalty to the republic which it had recently rebelled against, was blackmailed into supplying the besieging force with animals and supplies. His activity resulted in the acquisition of 100 guns for the force. With the help of his friends, the deputies Saliceti and Augustin Robespierre, who held power of life and death, he was able to compel retired artillery officers from the area to re-enlist. The problem of manning the guns was not remedied by this solution alone, and under Bonaparte's intensive training he instructed much of the infantry in the practice of employing, deploying and firing the artillery that his efforts had recently acquired. However, in spite of this effort, Bonaparte was not as confident about this operation as was later his custom. The officers serving with him in the siege were incompetent, and he was becoming concerned about the needless delays due to these officers' mistakes. He was so concerned that he wrote a letter of appeal to the Committee of Public Safety requesting assistance. To deal with his superiors who were wanting in skill, he proposed the appointment of a general for command of the artillery, succeeding himself, so that "... (they could) command respect and deal with a crowd of fools on the staff with whom one has constantly to argue and lay down the law in order to overcome their prejudices and make them take steps which theory and practice alike have shown to be axiomatic to any trained officer of this corps".Correspondence of Napoleon I, Vol. I, No. 2, p. 12

After some reconnaissance, Bonaparte conceived a plan which envisaged the capture of the forts of l'Eguillette and Balaguier, on the hill of Cairo, which would then prevent passage between the small and large harbours of the port, so cutting maritime resupply, necessary for those under siege. Carteaux, reluctant, sent only a weak detachment under Major General Delaborde, which failed in its attempted conquest on 22 September. The allies now alerted, built "Fort Mulgrave", so christened in honour of the British commander, Henry Phipps, 1st Earl of Mulgrave, on the summit of the hill. It was supported by three smaller ones, called Saint-Phillipe, Saint-Côme, and Saint-Charles. The apparently impregnable collection was nicknamed, by the French, "Little Gibraltar".

Bonaparte was dissatisfied by the sole battery—called the "Mountain", positioned on the height of Saint-Laurent since 19 September. He established another, on the shore of Brégallion, called the "'' sans-culottes''". Hood attempted to silence it, without success, but the British fleet was obliged to harden its resolve along the coast anew, because of the high seabed of Mourillon and la Tour Royale. On the first of October, after the failure of General La Poype against the "Eastern Fort" of Faron, Bonaparte was asked to bombard the large fort of Malbousquet, whose fall would be required to enable the capture of the city. He therefore requisitioned artillery from all of the surrounding countryside, holding the power of fifty batteries of six cannon apiece. Promoted to Chief of Battalion on 19 October, he organised a grand battery, said to be "of the Convention", on the hill of Arènes and facing the fort, supported by those of the "Camp of the Republicans" on the hill of Dumonceau, by those of the "Farinière" on the hill of Gaux, and those of the "Poudrière" at Lagoubran.

On 11 November, Carteaux was dismissed and replaced by François Amédée Doppet, formerly a doctor, whose indecision would cause an attempted surprise against Fort Mulgrave to fail on the 16th. Aware of his own incompetence, he resigned. He was succeeded by a career soldier, Dugommier, who immediately recognized the virtue of Bonaparte's plan, and prepared for the capture of Little Gibraltar. On the 20th, as soon as he arrived, the battery "

Despite the mutual dislike between Bonaparte and the chief of artillery, the young artillery officer was able to muster an artillery force that was worthy of a siege of Toulon and the fortresses that were quickly built by the British in its immediate environs. He was able to requisition equipment and cannon from the surrounding area. Guns were taken from Marseille, Avignon and the Army of Italy. The local populace, which was eager to prove its loyalty to the republic which it had recently rebelled against, was blackmailed into supplying the besieging force with animals and supplies. His activity resulted in the acquisition of 100 guns for the force. With the help of his friends, the deputies Saliceti and Augustin Robespierre, who held power of life and death, he was able to compel retired artillery officers from the area to re-enlist. The problem of manning the guns was not remedied by this solution alone, and under Bonaparte's intensive training he instructed much of the infantry in the practice of employing, deploying and firing the artillery that his efforts had recently acquired. However, in spite of this effort, Bonaparte was not as confident about this operation as was later his custom. The officers serving with him in the siege were incompetent, and he was becoming concerned about the needless delays due to these officers' mistakes. He was so concerned that he wrote a letter of appeal to the Committee of Public Safety requesting assistance. To deal with his superiors who were wanting in skill, he proposed the appointment of a general for command of the artillery, succeeding himself, so that "... (they could) command respect and deal with a crowd of fools on the staff with whom one has constantly to argue and lay down the law in order to overcome their prejudices and make them take steps which theory and practice alike have shown to be axiomatic to any trained officer of this corps".Correspondence of Napoleon I, Vol. I, No. 2, p. 12

After some reconnaissance, Bonaparte conceived a plan which envisaged the capture of the forts of l'Eguillette and Balaguier, on the hill of Cairo, which would then prevent passage between the small and large harbours of the port, so cutting maritime resupply, necessary for those under siege. Carteaux, reluctant, sent only a weak detachment under Major General Delaborde, which failed in its attempted conquest on 22 September. The allies now alerted, built "Fort Mulgrave", so christened in honour of the British commander, Henry Phipps, 1st Earl of Mulgrave, on the summit of the hill. It was supported by three smaller ones, called Saint-Phillipe, Saint-Côme, and Saint-Charles. The apparently impregnable collection was nicknamed, by the French, "Little Gibraltar".

Bonaparte was dissatisfied by the sole battery—called the "Mountain", positioned on the height of Saint-Laurent since 19 September. He established another, on the shore of Brégallion, called the "'' sans-culottes''". Hood attempted to silence it, without success, but the British fleet was obliged to harden its resolve along the coast anew, because of the high seabed of Mourillon and la Tour Royale. On the first of October, after the failure of General La Poype against the "Eastern Fort" of Faron, Bonaparte was asked to bombard the large fort of Malbousquet, whose fall would be required to enable the capture of the city. He therefore requisitioned artillery from all of the surrounding countryside, holding the power of fifty batteries of six cannon apiece. Promoted to Chief of Battalion on 19 October, he organised a grand battery, said to be "of the Convention", on the hill of Arènes and facing the fort, supported by those of the "Camp of the Republicans" on the hill of Dumonceau, by those of the "Farinière" on the hill of Gaux, and those of the "Poudrière" at Lagoubran.

On 11 November, Carteaux was dismissed and replaced by François Amédée Doppet, formerly a doctor, whose indecision would cause an attempted surprise against Fort Mulgrave to fail on the 16th. Aware of his own incompetence, he resigned. He was succeeded by a career soldier, Dugommier, who immediately recognized the virtue of Bonaparte's plan, and prepared for the capture of Little Gibraltar. On the 20th, as soon as he arrived, the battery "Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

" was established, on the ridge of l'Evescat. Then, on the left, on 28 November, the battery of the "Men Without Fear", and then on 14 December, the "Chasse Coquins" were constructed between the two. Two other batteries were organized to repel the eventual intervention of the allied ships, they were called "The Great Harbour" and the "Four Windmills".

Pressured by the bombardment, the Anglo-Neapolitans executed a sortie, and took hold of the battery of the "Convention". A counter-attack, headed by Dugommier and Bonaparte, pushed them back and the British general, Charles O'Hara

General Charles O'Hara (1740 – 25 February 1802) was a British Army officer who served in the Seven Years' War, the American War of Independence, and the French Revolutionary War and later served as governor of Gibraltar. He served with di ...

, was captured. He initiated surrender negotiations with Robespierre the Younger and Antoine Louis Albitte and the Federalist and Royalist battalions were disarmed.

Following O'Hara's capture, Dugommier, La Poype, and Bonaparte (now a colonel) launched a general assault during the night of 16 December. Around midnight, the assault began on Little Gibraltar and the fighting continued all night. Bonaparte was injured in the thigh by a British sergeant with a bayonet. However, in the morning, the position having been taken, Marmont was able to place artillery there, against l'Eguillette and Balaguier, which the British had evacuated without confrontation on the same day. During this time, La Poype finally was able to take the forts of Faron and Malbousquet. The allies then decided to evacuate by their maritime route. Commodore Sydney Smith was instructed by Hood to have the delivery fleet and the arsenal burnt.

Destruction of the French fleet

Lángara ordered Don Pedro Cotiella to take three boats into the arsenal to destroy the French fleet.

Lángara ordered Don Pedro Cotiella to take three boats into the arsenal to destroy the French fleet. Sir Sidney Smith

Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith (21 June 176426 May 1840) was a British naval and intelligence officer. Serving in the American and French revolutionary wars and Napoleonic Wars, he rose to the rank of Admiral.

Smith was known for his offe ...

, who had recently arrived, volunteered to accompany him with his ship ''Swallow'' and three British boats. Cotiella was tasked with sinking Toulon's hulks; one was a disarmed former British frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed an ...

captured during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, ''Montréal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple-p ...

'', and the other was the French frigate '' Iris''.Clowes, p. 209 These ships contained the gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

stores for the entire fleet and due to the danger of explosion were anchored in the outer roads, some distance from the city. He was then instructed to enter the Old Arsenal and destroy the ships there. The dock gates, which had been barred against attack and manned by 800 former galley slaves freed during the retreat. Their sympathies were with the advancing Republicans so to ensure that they did not interfere, Smith kept his guns trained on them throughout the operation.James, p. 80 His boats were spotted by the Republican batteries on the heights and cannonballs and shells landed in the arsenal, although none struck Smith's men. As darkness fell Republican troops reached the shoreline and contributed musketry to the fusillade; Smith replied with grapeshot from his boat's guns.Tracy, p. 44

At 20:00 Captain Charles Hare brought the fire ship HMS ''Vulcan'' into the New Arsenal. Smith halted the ship across the row of anchored French ships of the line, and lit the fuses at 22:00. Hare was badly wounded by an early detonation as he attempted to leave his ship.Tracy, p. 42 Simultaneously, fire parties set alight the warehouses and stores ashore, including the mast house and the hemp and timber stores, creating an inferno across the harbour as ''Vulcan''s cannons fired a last salvo at the French positions on the shore.James, p. 78 With the fires spreading through the dockyards and New Arsenal, Smith began to withdraw. His force was illuminated by the flames, making an inviting target for the Republican batteries. As his boats passed the ''Iris'', however, the powder ship suddenly and unexpectedly exploded, blasting debris in a wide circle and sinking two of the British boats. On ''Britannia'' all of the crew survived, but the blast killed the master and three men on ''Union''.Mostert, p. 116

With the New Arsenal in flames, Smith realised that the Old Arsenal appeared intact; only a few small fires marked the Spanish effort to destroy the French ships anchored within. He immediately led ''Swallow'' back towards the arsenal but found that Republican soldiers had captured it intact, their heavy musketry driving him back.Tracy, p. 29 Instead he turned to two disarmed ships of the line, '' Héros'' and '' Thémistocle'', which lay in the inner roads as prison hulks. The French Republican prisoners on board had initially resisted British efforts to burn the ships, but with the evidence of the destruction in the arsenal before them they consented to be safely conveyed to shore as Smith's men set the empty hulls on fire.

At 20:00 Captain Charles Hare brought the fire ship HMS ''Vulcan'' into the New Arsenal. Smith halted the ship across the row of anchored French ships of the line, and lit the fuses at 22:00. Hare was badly wounded by an early detonation as he attempted to leave his ship.Tracy, p. 42 Simultaneously, fire parties set alight the warehouses and stores ashore, including the mast house and the hemp and timber stores, creating an inferno across the harbour as ''Vulcan''s cannons fired a last salvo at the French positions on the shore.James, p. 78 With the fires spreading through the dockyards and New Arsenal, Smith began to withdraw. His force was illuminated by the flames, making an inviting target for the Republican batteries. As his boats passed the ''Iris'', however, the powder ship suddenly and unexpectedly exploded, blasting debris in a wide circle and sinking two of the British boats. On ''Britannia'' all of the crew survived, but the blast killed the master and three men on ''Union''.Mostert, p. 116

With the New Arsenal in flames, Smith realised that the Old Arsenal appeared intact; only a few small fires marked the Spanish effort to destroy the French ships anchored within. He immediately led ''Swallow'' back towards the arsenal but found that Republican soldiers had captured it intact, their heavy musketry driving him back.Tracy, p. 29 Instead he turned to two disarmed ships of the line, '' Héros'' and '' Thémistocle'', which lay in the inner roads as prison hulks. The French Republican prisoners on board had initially resisted British efforts to burn the ships, but with the evidence of the destruction in the arsenal before them they consented to be safely conveyed to shore as Smith's men set the empty hulls on fire.

Evacuation

With all the available targets on fire or in French hands, Smith withdrew once more, accompanied by dozens of small watercraft packed with Toulonnais refugees and Neapolitan soldiers separated during the retreat. As he passed the second powder hulk, ''Montréal'', she also exploded unexpectedly. Although his force was well within the blast radius, on this occasion none of Smith's men were struck by falling debris and his boats retired to the waiting British fleet without further incident. As Smith's boats had gone about their work Hood had ordered HMS ''Robust'' under CaptainGeorge Elphinstone

George Elphinstone of Blythswood (died 1634) was a Scottish landowner, courtier, and Provost of Glasgow.

Life

George Elphinstone was the son of George Elphinstone of Blythswood (died 2 April 1585), a leading Glasgow merchant and shipowner, and ...

and HMS ''Leviathan'' under Captain Benjamin Hallowell to evacuate the allied troops from the waterfront. They were joined by HMS ''Courageux'' under Captain William Waldegrave, which had been undergoing repairs in the Arsenal to replace a damaged rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally air or water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to counter adve ...

. Despite this handicap, ''Courageux'' was able to participate in the evacuation and warp

Warp, warped or warping may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books and comics

* WaRP Graphics, an alternative comics publisher

* ''Warp'' (First Comics), comic book series published by First Comics based on the play ''Warp!''

* Warp (comics), a ...

out of the harbour with the replacement rudder following behind, suspended between two ship's boats. The fireship HMS ''Conflagration'', also undergoing repairs, was unable to sail and was destroyed during the evacuation. By the morning of 19 December Elphinstone's squadron had retrieved all of the Allied soldiers from the city without losing a single man.

In addition to the soldiery, the British squadron and their boats took on board thousands of French Royalist refugees, who had flocked to the waterfront when it became clear that the city would fall to the Republicans. ''Robust'', the last to leave, carried more than 3,000 civilians from the harbour and another 4,000 were recorded on board ''Princess Royal'' out in the roads. In total the British fleet rescued 14,877 Toulonnais from the city; witnesses on board the retreating ships reported scenes of panic on the waterfront as stampeding civilians were crushed or drowned in their haste to escape the advancing Republican soldiers, who fired indiscriminately into the fleeing populace.Clowes, p. 210

Aftermath

Suppression

The troops of the Convention entered the city on the 19 December. The subsequent suppression of Royalists, directed by Paul Barras and Stanislas Fréron, was extremely bloody. It is estimated that between 700 and 800 prisoners were shot or slain by bayonet on Toulon's Champ de Mars. Bonaparte, treated for his injuries by Jean François Hernandez, was not present at the massacre. Promoted tobrigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

on 22 December, he was already on his way to his new post in Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative ...

as the artillery commander for the Army of Italy. A gate, which comprises part of the old walls of the city of Toulon, evokes his departure; a commemorative plaque has been affixed there. This gate is called the ''Porte d'Italie''.

Order of battle

Below is the full order of battle of forces involved. Because no centralised command existed for the allies, they are simply designated as the 'Allied Army', however this was neither a field formation, nor a coherent force. The order of battle below is shown for the last part of the siege (from September).French Republicans

Allied Army

Allied Fleet

See also

*Military career of Napoleon Bonaparte

The military career of Napoleon Bonaparte spanned over 20 years. As military leader, he led the French armies to defeat in the Napoleonic Wars. Despite his losing war record and ending in defeat, Napoleon is regarded in Europe as a military geniu ...

Notes and citations

NotesReferences

* * * * * * * Chandler, David. ''The Campaigns of Napoleon''. Simon & Schuster, 1966. * * Ireland, Bernard. ''The Fall of Toulon: The Last Opportunity to Defeat the French Revolution''. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2005. * * * Smith, Digby. ''The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book''. Greenhill Books, 1998. * * Usherwood, Stephen. "The Siege of Toulon, 1793." ''History Today'' (Jan 1972), Vol. 22 Issue 1, pp17–24 online.External links

Engraved map plate "Siege of Toulon, 19 December 1793"

Atlas to Alison's History of Europe, by Alison & Johnston, published by William Blackwood and Sons in 1850. * {{Authority control French Revolutionary Wars 1793 in France Toulon