Sheng Shicai on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sheng Shicai (; 3 December 189513 July 1970) was a Chinese

Not long after Sheng's resignation, a delegation from

Not long after Sheng's resignation, a delegation from

Ma sieged Ürümqi for the second time in January 1934. This time, the Soviets assisted Sheng with air support and two brigades of the

Ma sieged Ürümqi for the second time in January 1934. This time, the Soviets assisted Sheng with air support and two brigades of the

The dependency of the Sheng regime on the Soviet Union was further highlighted with the publication of the "Six Great Policies" in December 1934. The Policies guaranteed his previously enacted "Great Eight-Point Manifesto" and included "anti-imperialism, friendship with the Soviet Union, racial and national equality, clean government, peace and reconstruction". Sheng referred to them as "a skillful, vital application of

The dependency of the Sheng regime on the Soviet Union was further highlighted with the publication of the "Six Great Policies" in December 1934. The Policies guaranteed his previously enacted "Great Eight-Point Manifesto" and included "anti-imperialism, friendship with the Soviet Union, racial and national equality, clean government, peace and reconstruction". Sheng referred to them as "a skillful, vital application of

In

In  After Muhiti's flight to British India, Muhiti's troops revolted. The revolt was Islamic in its nature. Muhiti's officer Abdul Niyaz succeeded him and was proclaimed a general. Niyaz took

After Muhiti's flight to British India, Muhiti's troops revolted. The revolt was Islamic in its nature. Muhiti's officer Abdul Niyaz succeeded him and was proclaimed a general. Niyaz took

During the Islamic rebellion, Sheng launched his own purge in Xinjiang to coincide with Stalin's

During the Islamic rebellion, Sheng launched his own purge in Xinjiang to coincide with Stalin's

During Sheng's rule, the

During Sheng's rule, the

In March 1935,

In March 1935,

Sheng had long prepared to purge the Chinese communists in Xinjiang. In 1939, his agents filled reports on clandestine meetings, the constant exchange of letters, and the unauthorized content of some of their propaganda. A month after the German invasion, in July 1941, the communist cadre had been demoted or cashiered. Chen Tanqiu, the chief liaison of the Communist Party of China (CCP) reported in

Sheng had long prepared to purge the Chinese communists in Xinjiang. In 1939, his agents filled reports on clandestine meetings, the constant exchange of letters, and the unauthorized content of some of their propaganda. A month after the German invasion, in July 1941, the communist cadre had been demoted or cashiered. Chen Tanqiu, the chief liaison of the Communist Party of China (CCP) reported in  The final months of 1942 saw the most turbulent period in Xinjiang-Soviet relations. In October 1942 Sheng demanded from the Soviet General Consul that all Soviet technical and military personnel be withdrawn from Xinjiang within three months. To the Soviets, who were engaged in the

The final months of 1942 saw the most turbulent period in Xinjiang-Soviet relations. In October 1942 Sheng demanded from the Soviet General Consul that all Soviet technical and military personnel be withdrawn from Xinjiang within three months. To the Soviets, who were engaged in the

warlord

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

who ruled Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

from 1933 to 1944. Sheng's rise to power started with a coup d'état in 1933 when he was appointed the ''duban'' or Military Governor of Xinjiang. His rule over Xinjiang is marked by close cooperation with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, allowing the Soviets trade monopoly and exploitation of resources, which effectively made Xinjiang a Soviet puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sove ...

. The Soviet era ended in 1942, when Sheng approached the Nationalist Chinese government, but still retained much power over the province. He was dismissed from post in 1944 and named Minister of Agriculture and Forestry. Growing animosity against him led the government to dismiss him again and appoint to a military post. At the end of the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

, Sheng fled mainland China to Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

with the rest of Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

.

Sheng Shicai was a Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

n-born Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

, educated in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

, where he studied political economy and later attended the Imperial Japanese Army Academy

The was the principal officer's training school for the Imperial Japanese Army. The programme consisted of a junior course for graduates of local army cadet schools and for those who had completed four years of middle school, and a senior course f ...

. Having become a Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

in his youth, Sheng participated in the anti-imperialist May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chin ...

in 1919. He participated in the Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The ...

, a military campaign of the Kuomintang against the Beiyang government

The Beiyang government (), officially the Republic of China (), sometimes spelled Peiyang Government, refers to the government of the Republic of China which sat in its capital Peking (Beijing) between 1912 and 1928. It was internationally ...

.

In 1929, he was called into service of the Governor of Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

, Jin Shuren, where he served as Chief of Staff of the Frontier Military and Chief Instructor at the Provincial Military College. With the Kumul Rebellion ongoing, Jin was overthrown in a coup on 12 April 1933 and Sheng was appointed ''duban'' or Military Governor of Xinjiang. Since then, he led a power struggle against his rivals, of whom Ma Zhongying and Zhang Peiyuan

Zhang Peiyuan (traditional Chinese: 張培元) ( – 1 June 1934) was a Han chinese general, commander of the Ili garrison. He fought against Uighur and Tungans during the Kumul revolt, but then secretly negotiated with the Tungan genera ...

were most notable. The first to be removed were the coup leaders and by them appointed Civil Governor Liu Wenlong by September 1933. Ma and Zhang were defeated militarily by June 1934 with help from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, whom Sheng invited to intervene, subordinating himself to the Soviets in return.

As ruler of Xinjiang, Sheng implemented his Soviet-inspired policies through his political program of Six Great Policies, adopted in December 1934. His rule was marked by his nationality policy which promoted national and religious equality and identity of various nationalities of Xinjiang. The province saw a process of modernisation, but also the subordination of economic interests in Soviet favour. The Soviets had a monopoly over Xinjiang trade and exploited its rare materials and oil. In 1937, in parallel with the Soviet Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

, Sheng conducted a purge on his own, executing, torturing to death and imprisoning 100,000 people, the majority of which were Uyghurs

The Uyghurs; ; ; ; zh, s=, t=, p=Wéiwú'ěr, IPA: ( ), alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central Asia, Cent ...

.

With the Soviets distracted by its war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, Sheng approached the Chinese government in July 1942 and expelled the Soviet military and technical personnel. However, he still maintained effective power over Xinjiang. In the meantime, the Soviets managed to hold off the Germans and the Japanese launched an extensive offensive against the Chinese, which led Sheng to try to change sides again by arresting the Kuomintang officials and invoking Soviet intervention for the second time in 1944. The Soviets ignored the request and the Chinese government removed him from the post naming him Minister of Agriculture and Forestry in August 1944.

Sheng held the ministerial post by July 1945 and later worked as an adviser to Hu Zongnan

Hu Zongnan (; 16 May 1896 – 14 February 1962), courtesy name Shoushan (壽山), was a Chinese general in the National Revolutionary Army and then the Republic of China Army. Together with Chen Cheng and Tang Enbo, Hu, a native of Zh ...

and held a military post. He joined the rest of the Kuomintang in Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

after the defeat in the Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on main ...

in 1949. In Taiwan, Sheng lived in a comfortable retirement and died in Taipei

Taipei (), officially Taipei City, is the capital and a special municipality of the Republic of China (Taiwan). Located in Northern Taiwan, Taipei City is an enclave of the municipality of New Taipei City that sits about southwest of the ...

in 1970.

Early life

Sheng, an ethnicHan Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

, was born in Kaiyuan, Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

in a well-to-do peasant family on 3 December 1895. His great grandfather, Sheng Fuxin(盛福信), was originally from Shandong Province and later fled to Kaiyuan. Sheng enrolled at the Provincial Forestry and Agricultural School in Mukden

Shenyang (, ; ; Mandarin pronunciation: ), formerly known as Fengtian () or by its Manchu name Mukden, is a major Chinese sub-provincial city and the provincial capital of Liaoning province. Located in central-north Liaoning, it is the provinc ...

, aged 14. At age of 17, Sheng enrolled at the Wusong Public School in Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

, where he studied political science and economy. There, he became friendly with students and teachers of "radical inclinations". After graduating in 1915, under their advice he went to study in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

. There, Sheng enrolled at the Waseda University

, mottoeng = Independence of scholarship

, established = 21 October 1882

, type = Private

, endowment =

, president = Aiji Tanaka

, city = Shinjuku

, state = Tokyo

, country = Japan

, students = 47,959

, undergrad = 39,382

, postgrad ...

, where he studied political economy for a year. During that time, Sheng expressed nationalistic attitudes and was exposed to "The ABC of Communism

''The ABC of Communism'' (russian: Азбука коммунизма ''Azbuka Kommunizma'') is a book written by Nikolai Bukharin and Yevgeni Preobrazhensky in 1919, during the Russian Civil War.

" () and other leftist publications.

Ferment in China made him return to homeland. In 1919, he participated in the May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese anti-imperialist, cultural, and political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen (The Gate of Heavenly Peace) to protest the Chin ...

as a representative of the Liaoning students. During this period, he developed radical and anti-Japanese sentiments. By his own admission, Sheng became a Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

the very same year and his political opponents claimed he became a communist during his second stay in Japan in the 1920s. During that time, he realised the "futility of book learning", and decided to enter a military career. He took military training in the southern province of Kwantung, known for liberal and reformist views. Later, he enrolled at the Northeastern Military Academy.

Sheng entered military service under Guo Songling, Deputy of Zhang Zuolin, a Manchurian warlord. He rapidly rose to become Staff Officer with the rank of lieutenant colonel, and was given command of a company. Because of his commendable service, Guo sponsored his admission to the Imperial Japanese Army Academy

The was the principal officer's training school for the Imperial Japanese Army. The programme consisted of a junior course for graduates of local army cadet schools and for those who had completed four years of middle school, and a senior course f ...

for advanced military studies. Three years later he completed his studies, with minor interruptions in 1925, when he was involved in Manchurian politics.

At that time, Sheng supported a campaign against Zhang, briefly returning to Manchuria. Although he supported the anti-Zhang coup, he was able to return to Japan with the support of Feng Yuxiang and Chiang Kai-Shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, from whom he received financial help and considered him as his patron.

Sheng returned from Japan in 1927 to participate in the Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT), also known as the "Chinese Nationalist Party", against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The ...

A rising young officer, Sheng was given the rank of colonel and served as a Staff Officer of the Chiang's field headquarters under He Yingqin. During the Northern Expedition, Sheng proved himself as a worthy officer, serving in various command staff capacities.

Sheng was a member of the Guominjun, a leftist nationalist faction that supported the Nationalist government in China. However, Sheng did not join the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Ta ...

because of his belief in Marxism. After the Expedition was completed, he was made chief of the war operations section of the general staff in Nanking

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

, but resigned in 1929 over a disagreement with his superiors. After the apparent setback in his career, Sheng dedicated himself to the question of strengthening China's border defences.

Power struggle

Rise to power

Not long after Sheng's resignation, a delegation from

Not long after Sheng's resignation, a delegation from Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwes ...

came to Nanking

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

to ask for financial aid. The Governor of Xinjiang Jin Shuren asked one of the members of the delegation, the Deputy General Secretary of Xinjiang Guang Lu, to find a competent officer to reorganise the provincial military. After discreet enquiries, Sheng was appointed to Jin's staff and arrived in Xinjiang via Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

in the winter of 1929–30. Chiang Kai-Shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

may have endorsed Sheng's decision to go to Xinjiang. Therefore, the appointment of Ma Zhongying, a Sheng's rival, as a commander of the 36th Division in Xinjiang embarrassed and frustrated Sheng. Sheng's welcome in Xinjiang was cold. Jin considered him a potential threat. Despite the doubts, Jin appointed him Chief of Staff of the Frontier Army and subsequently named him Chief Instructor at the Provincial Military College.

In the summer of 1932, the fighting between Ma and Jin had significantly intensified. Ma's Hui forces were able to break the defence lines at Hami

Hami (Kumul) is a prefecture-level city in Eastern Xinjiang, China. It is well known as the home of sweet Hami melons. In early 2016, the former Hami county-level city was merged with Hami Prefecture to form the Hami prefecture-level city with t ...

and enter Xinjiang through the Hexi Corridor

The Hexi Corridor (, Xiao'erjing: حْسِ ظِوْلاْ, IPA: ), also known as the Gansu Corridor, is an important historical region located in the modern western Gansu province of China. It refers to a narrow stretch of traversable and rela ...

. In December 1932, Ma's forces started the siege of Ürümqi, but the White Russians and Sheng's troops successfully defended the city. In March 1933, the Manchurian Salvation Army, part of the National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

(NRA), came to their aid through the Soviet territory. During these events, Jin's prestige declined and correspondingly Sheng became increasingly popular. The culmination was the coup staged by the White Russians and a group of provincial bureaucrats led by Chen Zhong, Tao Mingyue and Li Xiaotian on 12 April 1933, who overthrew Jin, who escaped to China proper via Siberia.

Sheng, who was marshalling the provincial forces in eastern Xinjiang, returned to Ürümqi to seize power in the midst of the chaos. Without conferring the Chinese government, the coup leaders appointed Sheng the Commissioner of the Xinjiang Border Defence, i. e., Military Governor or ''duban'' on 14 April 1933, resurrecting the old title. Liu Wenlong, a powerless provincial bureaucrat was installed as the Civil Governor.

Rivalry with Ma and Zhang

Sheng's appointment as ''duban'' did not mean that his position was secured. Installment of Wenlong as governor meant that the bureaucrats had the upper hand over Sheng, whom they considered their protege. His position was also challenged by Ma, as well asZhang Peiyuan

Zhang Peiyuan (traditional Chinese: 張培元) ( – 1 June 1934) was a Han chinese general, commander of the Ili garrison. He fought against Uighur and Tungans during the Kumul revolt, but then secretly negotiated with the Tungan genera ...

, Jin's old ally and a commander of the Yining

YiningThe official spelling according to (), also known as Ghulja ( ug, غۇلجا) or Qulja ( kk, قۇلجا) and formerly Ningyuan (), is a county-level city in Northwestern Xinjiang, People's Republic of China and the seat of the Ili Kazakh A ...

region. The Chinese government, having learned that Zhang refused to cooperate with the new regime in Xinjiang and that Ma's forces represented the gravest threat to the new regime, tried to take the advantage of the situation and take control over the province. Without clearly stating whether it recognised the changes in Xinjiang, the government appointed Huang Musong Huang or Hwang may refer to:

Location

* Huang County, former county in Shandong, China, current Longkou City

* Yellow River, or Huang River, in China

* Huangshan, mountain range in Anhui, China

* Huang (state), state in ancient China.

* Hwang Riv ...

, then a Deputy Chief of General Staff, a "pacification commissioner" in May 1933. He arrived in Ürümqi on 10 June. The appointment of Huang as a pacification commissioner further strained the relations between Shang and the Chinese government.

Sheng expected that the Chinese government would recognise him as ''duban'', and that Huang's visit would affect that decision. Huang was ignorant of the frontier problems and his arrogant behaviour offended some of the provincial leaders. The rumours spread that Huang was already named a new governor or that Chiang decided to split Xinjiang into several smaller provinces. However, the true Huang's task was to secure the cooperation between the coup leaders and establish a new provincial mechanism with a pro-Nanking stance. Sheng exploited the rumours and charged that Huang, an agent of Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei (4 May 1883 – 10 November 1944), born as Wang Zhaoming and widely known by his pen name Jingwei, was a Chinese politician. He was initially a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang, leading a government in Wuhan in oppositi ...

had plotted with Liu, Zhang and Ma to overthrow the provincial government. On 26 June Huang was placed under house arrest, and the three coup leaders were also arrested and immediately executed. After the Chinese government apologised and promised Sheng the recognition of his position, Huang was allowed to return to Nanking three weeks after the arrest.

Shortly afterwards, in August Chiang sent Foreign Minister Luo Wengan, as a sign of goodwill, to preside over Sheng's inauguration ceremony as a Commissioner of the Xinjiang Border Defence. However, at the same time, the Chinese government used Luo's visit to contact two of Sheng's rivals, Ma in Turpan

Turpan (also known as Turfan or Tulufan, , ug, تۇرپان) is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of and a population of 632,000 (2015).

Geonyms

The original name of the cit ...

and Zhang in Yining. They were encouraged to launch an attack against Sheng. As soon as Luo left the province, a war broke out between Sheng on one side, and Ma and Zhang on the other. Sheng accused Luo not only for plotting but also of an assassination attempt. Luo's left Xinjiang in early October, and his departure marked the beginning of the era of deep alienation between Sheng and the Chinese government.

In September 1933, Sheng accused Civil Governor Liu Wenlong of plotting with Ma and Zhang through Luo with Nanking in order to overthrow him. He was forced to resign and was replaced by Zhu Ruichi, a more controllable official. Sheng created a new bureaucratic hierarchy, nepotistically appointing new officials and replacing one of his predecessors.

Confronted by Ma's army outside of Ürümqi, Sheng sent a delegation to Soviet Central Asia to request assistance. Sheng later claimed that the delegation was sent under the aegis of Jin's request for military equipment. However, Sheng made a more comprehensive deal with the Soviets. His delegation returned in December 1933, together with Garegin Apresov, who would later be appointed as the Soviet General Consul in Ürümqi. The Soviets provided substantive military assistance to Sheng, who in return gave the Soviets wide political, economic and military control over Xinjiang.

Ma sieged Ürümqi for the second time in January 1934. This time, the Soviets assisted Sheng with air support and two brigades of the

Ma sieged Ürümqi for the second time in January 1934. This time, the Soviets assisted Sheng with air support and two brigades of the Joint State Political Directorate

The Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU; russian: Объединённое государственное политическое управление) was the intelligence and state security service and secret police of the Soviet Union f ...

. With their aid, Sheng again defeated Ma's forces, who retreated south from Tien Shan

The Tian Shan,, , otk, 𐰴𐰣 𐱅𐰭𐰼𐰃, , tr, Tanrı Dağı, mn, Тэнгэр уул, , ug, تەڭرىتاغ, , , kk, Тәңіртауы / Алатау, , , ky, Теңир-Тоо / Ала-Тоо, , , uz, Tyan-Shan / Tangritog‘ ...

, in a region controlled by the East Turkestan Republic (ETR). The same month, Ma's forces arrived in Kashgar

Kashgar ( ug, قەشقەر, Qeshqer) or Kashi ( zh, c=喀什) is an oasis city in the Tarim Basin region of Southern Xinjiang. It is one of the westernmost cities of China, near the border with Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Pakistan. ...

, extinguishing the ETR. Hoja-Niyaz, president of the ETR escaped upon the arrival of Ma's troops to the Xinjiang-Soviet border, and in town Irkeshtam

Erkeshtam, also Irkeshtam or Erkech-Tam ( ky, Эркеч-Там, Erkech-Tam, ), is a border crossing between Kyrgyzstan and Xinjiang, China, named after a village on the Kyrgyz side of the border in southern Osh Region. The border crossing is a ...

signed an agreement that abolished the East Turkestan Republic and supported Sheng's regime. In early 1934, Zhu Ruichi died and was replaced by Li Rong as Civil Governor.

In January, the Chinese government approved Huang Shaohong

Huang Shaohong (1895 – August 31, 1966) was a warlord in Guangxi province and governed Guangxi as part of the New Guangxi Clique through the latter part of the Warlord era, and a leader in later years of the Republic of China.

Biography

...

's plan for military operation in Xinjiang, in order to put the province under its effective control. Huang had in mind to act pragmatically, offering support either to Sheng or Ma, whoever was willing to cooperate with the Chinese government. The pretext for the operation was the development of Xinjiang and adjacent provinces. For that purpose, the Xinjiang Construction Planning Office was established in Xinjiang with Huang in charge. With enthusiasm from the Minister of Finance H. H. Kung

Kung Hsiang-hsi (; 11 September 1881 – 16 August 1967), often known as Dr. H. H. Kung, was a Chinese banker and politician in the early 20th century. He married Soong Ai-ling, the eldest of the three Soong sisters; the other two married Preside ...

, Huang purchased foreign-manufactured armored vehicles. By April, the preparations reached their final stage. However, the whole plan came to a halt in May because the Soviets have already entered Xinjiang and assisted Sheng against Ma.

Under pressure from Sheng's strengthened military forces, Ma's troops retreated from Kashgar in June–July 1934 to the southeast towards Hotan

Hotan (also known as Gosthana, Gaustana, Godana, Godaniya, Khotan, Hetian, Hotien) is a major oasis town in southwestern Xinjiang, an autonomous region in Western China. The city proper of Hotan broke off from the larger Hotan County to become ...

and Yarkand

Yarkant County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also Shache County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also transliterated from Uyghur as Yakan County, is a county in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous ...

, where they remained until 1937. Ma himself retreated via Irkeshtam to Soviet Central Asia, accompanied by several officers and a Soviet official. Sheng sent requests to the Soviets to turn him in, but they refused. By this move, the Soviets intended to achieve dual benefits. First, by removing Ma from Xinjiang's political arena, they wanted to increase Sheng's rule, which would give them higher control over the province; and second, they intended to use Ma as leverage against Sheng in case he did not comply with their interests in the province. The armistice between the Hui forces and the Xinjiang government was agreed upon in September 1934. Zhang, after suffering defeat, committed suicide.

Following the withdrawal of the Hui forces to Hotan in July 1934, Ma Hushan

Ma Hu-shan (Xiao'erjing: , zh, t=馬虎山, s=马虎山, first=t, p=Mǎ Hushān; 1910 – 1954) was a Hui (Chinese Muslim) warlord and the brother-in-law and follower of Ma Chung-ying, a Dungan/Hui Ma Clique warlord. He ruled over an area of ...

consolidated his power over the remote oases of the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hyd ...

, thus establishing a Hui satrapy, where Hui Muslims ruled as colonial masters over their Turkic Muslim subjects. The region was named Tunganistan by Walther Heissig. Tunganistan was bordering on two, eventually, three sides with Xinjiang province, and on the fourth side bordered the Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

. Despite the fact that negotiations were underway with the command of the 36th Division, the Dungan command did not make concessions on any issues. Moreover, the Soviets, intending to keep the 36th Division as a fallback against Sheng, vacillated regarding the complete annihilation of the 36th Division, giving refuge to the Dungan commanders and establishing trade relations with the 36th Division.

Rule

Consolidation

On the anniversary of the 12 April coup in 1934, the Xinjiang provincial government published an administrative plan called the "Great Eight-Point Manifesto" or "Eight Great Proclamations". These included: the establishment of racial equality, guarantee of religious freedom, equitable distribution of agricultural and rural relief, reform of government finance, the cleaning up of government administration, the expansion of education, the promotion of self-government and the improvement of the judiciary. The program was practicable since each point represented a grievance that one nationality had against the previous government, which enabled Sheng to enact the reforms. The first two points which dealt with "the realisation of equality for all nationalities" and "the protection of the rights of believers" advanced the national and religious rights of the Xinjiang nationalities. Sheng sent a letter toJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

, Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

and Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov (, uk, Климент Охрімович Ворошилов, ''Klyment Okhrimovyč Vorošylov''), popularly known as Klim Voroshilov (russian: link=no, Клим Вороши́лов, ''Klim Vorošilov''; 4 Februa ...

in June 1934. In the letter, Sheng expressed his belief in the victory of Communism and referred to himself as "convinced supporter of Communism". He called for the "fastest possible implementation of Communism in Xinjiang". Sheng also not only denounced the Chinese government

The Government of the People's Republic of China () is an authoritarian political system in the People's Republic of China under the exclusive political leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It consists of legislative, executive, m ...

, but expressed his aim in overthrowing it, suggesting support for the Chinese Soviet Republic

The Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) was an East Asian proto-state in China, proclaimed on 7 November 1931 by Chinese communist leaders Mao Zedong and Zhu De in the early stages of the Chinese Civil War. The discontiguous territories of t ...

and joint offensive against the Chinese government. Sheng also expressed his wish to join the Communist Party of Soviet Union. In a letter sent to the Soviet General Consul Garegin Apresov

Garegin Abramovich Apresov (russian: Гарегин Абрамович Апресов; 6 January 1890 – 11 September 1941) was a Soviet diplomat, most notable for his tenure in Xinjiang during Sheng Shicai's rule.

Life

Garegin A. Apreso ...

in Ürümqi

Ürümqi ( ; also spelled Ürümchi or without umlauts), formerly known as Dihua (also spelled Tihwa), is the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of the People's Republic of China. Ürümqi developed its ...

, Stalin commented that the Sheng's letter made a "depressing impression on our comrades". The content of Sheng's letter led Stalin to refer him as "a provocateur or a hopeless "leftist" having no idea about Marxism". In a reply to Sheng, Stalin, Molotov and Voroshilov refused all of his proposals.

In August 1934, Sheng affirmed that the nine duties of his government are to eradicate corruption, to develop economy and culture, to maintain peace by avoiding war, to mobilise all manpower for the cultivation of land, to improve communication facilities, to keep Xinjiang permanently a Chinese province, to fight against imperialism and Fascism and to sustain a close relationship with Soviet Russia, to reconstruct a "New Xinjiang", and to protect the positions and privileges of religious leaders.

Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, Leninism

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establish ...

, and Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the the ...

in the conditions of the feudal society of economically and culturally backward Xinjiang". They served as the ideological basis of Sheng's rule. With the proclamation of the Six Great Policies, Sheng adopted a new flag with a six-pointed star to represent these policies.

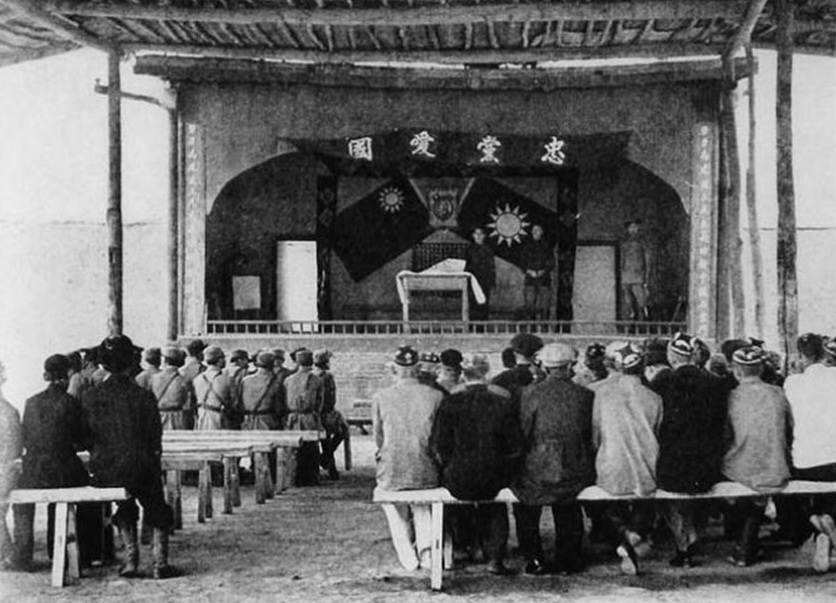

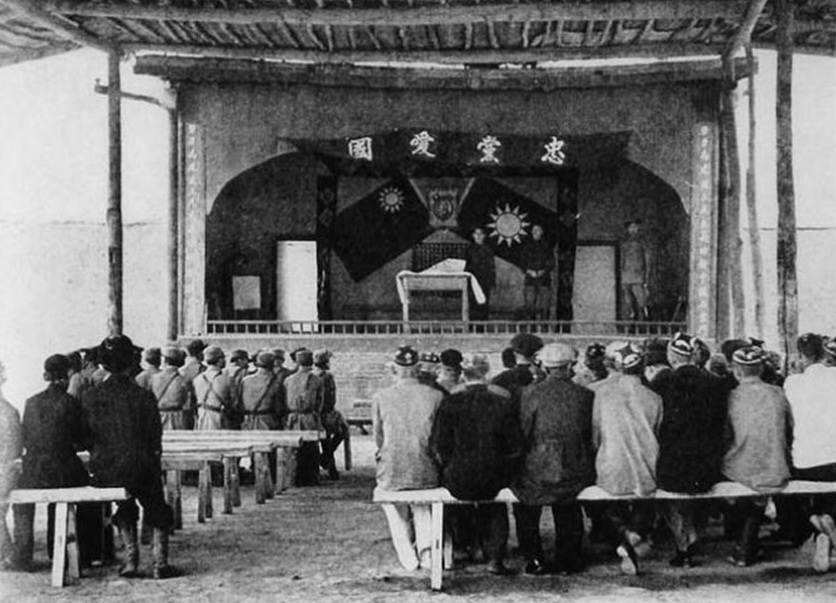

On 1 August 1935, Sheng founded the People's Anti-Imperialist Association

People's Anti-Imperialist Association () was a political party in Xinjiang, China during the rule of Sheng Shicai, between 1935 and 1942.

History

The People's Anti-Imperialist Association was founded by Sheng Shicai in Ürümqi on 1 August 1 ...

in Ürümqi

Ürümqi ( ; also spelled Ürümchi or without umlauts), formerly known as Dihua (also spelled Tihwa), is the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of the People's Republic of China. Ürümqi developed its ...

. Garegin Apresov submitted a presentation to the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (, abbreviated: ), or Politburo ( rus, Политбюро, p=pəlʲɪtbʲʊˈro) was the highest policy-making authority within the Communist Party of th ...

which accepted the creation of the association on 5 August. The association had to be composed of representatives of the Soviet special services bodies. As the leader of the association, Sheng became one of the main figures of Soviet regional policy. The creation of the association strengthened the Soviet position in Xinjiang.

The propaganda of the association was the ''Anti-Imperialist War Front''. Xinjiang's Youth and Xinjiang's Women served as the association's youth and women's wing respectively. In 1935, the association had 2,489 members, and in 1939, the Association's membership rose to 10,000. The membership was nationally diverse, and included Han, Hui and various Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging to ...

.

In 1935 the British consul in Kashgar sent a report to the Foreign Office which stated that the influence of the Soviet Union on Xinjiang and its population increased. In order to check the reliability of these claims, the Chinese government sent a special commission to Ürümqi. However, the commission concluded that Soviet assistance is friendly and commensurate with the assistance previously provided to the province by the Soviet Union. Only after this, the governments of Xinjiang, China, and the Soviet Union issued a joint statement in which the allegedly impending annexation of Xinjiang to the USSR was characterised as untrue. Sheng and the "reliable people" he appointed in the province played a special role in the fact that the Chinese authorities came to this conclusion. After this joint statement, the Soviet Union felt even more comfortable in Xinjiang politics. In 1935 the Politburo made several secret decisions to strengthen Soviet influence in the region.

When in December 1936 Zhang Xueliang

Chang Hsüeh-liang (, June 3, 1901 – October 15, 2001), also romanized as Zhang Xueliang, nicknamed the "Young Marshal" (少帥), known in his later life as Peter H. L. Chang, was the effective ruler of Northeast China and much of northern ...

rebelled against the Chinese government and arrested Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, which led to the Xi'an Incident. Sheng sided with Zhang, who asked for his help, and intended to proclaim that his rebels were under Xinjiang's protection. Only after the Soviets condemned the incident and characterised it as a Japanese provocation, and demanded from Sheng to drop his support for Zhang, did Sheng refuse to support Zhang.

Kashgar region and Islamic Rebellion

Two weeks after Ma Zhongying left for the Soviet territory, in early July 1934,Kashgar

Kashgar ( ug, قەشقەر, Qeshqer) or Kashi ( zh, c=喀什) is an oasis city in the Tarim Basin region of Southern Xinjiang. It is one of the westernmost cities of China, near the border with Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Pakistan. ...

was occupied by a unit of 400 Chinese soldiers under the command of Kung Cheng-han on 20 July. He was accompanied by the 2,000 strong Uighurs commanded by Mahmut Muhiti

Mahmut Muhiti (; ; 1887–1944), nicknamed Shizhang (), was a Uyghur warrior from Xinjiang. He was a commander of the insurgents led by Khoja Niyaz during the Kumul Rebellion against the Xinjiang provincial authorities. After Hoya-Niyaz and ...

, a wealthy ex-merchant. Thus, Kashgar was peacefully taken over by Xinjiang's provincial authority after almost a year.

To reassure the local population and to give himself additional time to consolidate his power in the northern and eastern parts of the province, Sheng appointed Muhiti as the overall Military Commander for the Kashgar region. Sheng was not comfortable with the Muslim officials in Kashgar, therefore a month later, he appointed his fellow Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

n Liu Pin to the position of Commanding Officer in Kashgar. Muhiti was demoted and retained the position of Divisional Commander.

Sheng's Han Chinese appointees took effective control over the Kashgar region, and foremost amongst them was Liu, a Chinese nationalist, and a Christian. Liu understood little about the local Muslim culture. Immediately upon his arrival, he ordered that the picture of Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, the founder of the Chinese Republic, be hung in the Kashgar mosque. The local Muslim population was dismayed by the developments in Kashgar and considered that the "Bolsheviks had taken over the country and were bent on destroying religion". Also Sheng's educational reform which attacked basic Islamic principles, as well as atheistic propaganda, contributed to the alienation of the Xinjiang's Muslim population.

Also in 1936, in the Altay region in northern Xinjiang, local Muslim nationalists, led by Younis Haji, founded the Society of National Defence. This society included influential Muslim figures. Sheng received information on the preparation of a powerful protest movement by this society. However, he did not have the capacity to suppress this movement with his own forces.

In

In Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, Muhammad Amin Bughra

Muhammad Amin Bughra (also Muḥammad Amīn Bughra; ug, مۇھەممەد ئىمىن بۇغرا, محمد أمين بغرا, ; ), sometimes known by his Han name Mao Deming () and his Turkish name Mehmet Emin Buğra; 1901–1965), was a Turkic ...

, the exiled leader of the East Turkestan Republic, approached the Japanese ambassador in 1935 proposing the establishment of the ETR under Japanese patronage and proposed Mahmut Muhiti as the leader of the newly established puppet state. The plan was later aborted when Mahmud in fear for his life fled from Kashgar to British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

in April 1937.

Muhiti became the focal point of the opposition to Sheng's government. From the middle of 1936, he and his supporters began to propagate the idea of creating an "independent Uyghur state". In this case, he was supported by Muslim religious leaders and influential people from Xinjiang. Muhiti, having entered into contact with the Soviet consul in Kashgar Smirnov, even tried to get weapons from the Soviet Union, but his appeal was rejected. Then, by contacting former Dungan opponents, in early April 1937, Muhiti was able to raise an uprising against the Xinjiang authorities. However, only two regiments of the 6th Uyghur Division, stationed north and south of Kashgar in Artush and Yengihissar, came out in his defence, while the other two regiments, 33rd and 34th, stationed in Kashgar itself, declared their loyalty to the Sheng's government.

Urged by the Soviets, Sheng's government sent a peacekeeping mission to Kashgar to resolve the conflict. The negotiations, however, did not take place. The Soviets tried to contact Ma Hushan

Ma Hu-shan (Xiao'erjing: , zh, t=馬虎山, s=马虎山, first=t, p=Mǎ Hushān; 1910 – 1954) was a Hui (Chinese Muslim) warlord and the brother-in-law and follower of Ma Chung-ying, a Dungan/Hui Ma Clique warlord. He ruled over an area of ...

, the new commander of the Dungan 36th Division, via Ma Zhongying, to disarm Muhiti's rebels. However, Muhiti, with 17 of his associated fled to British India on 2 April 1937.

After Muhiti's flight to British India, Muhiti's troops revolted. The revolt was Islamic in its nature. Muhiti's officer Abdul Niyaz succeeded him and was proclaimed a general. Niyaz took

After Muhiti's flight to British India, Muhiti's troops revolted. The revolt was Islamic in its nature. Muhiti's officer Abdul Niyaz succeeded him and was proclaimed a general. Niyaz took Yarkand

Yarkant County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also Shache County,, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency also transliterated from Uyghur as Yakan County, is a county in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous ...

and moved towards Kashgar, eventually capturing it. Those with pro-Soviet inclinations were executed and thus new Muslim administration was established. Simultaneously, the uprising spread amongst the Kirghiz near Kucha and among Muslims in Hami

Hami (Kumul) is a prefecture-level city in Eastern Xinjiang, China. It is well known as the home of sweet Hami melons. In early 2016, the former Hami county-level city was merged with Hami Prefecture to form the Hami prefecture-level city with t ...

. After capturing Kashgar, Niyaz's forces started to move towards Karashar

Karasahr or Karashar ( ug, قاراشەھەر, Qarasheher, 6=Қарашәһәр), which was originally known, in the Tocharian languages as ''Ārśi'' (or Arshi) and Agni or the Chinese derivative Yanqi ( zh, s=焉耆, p=Yānqí, w=Yen-ch'i), is an ...

, receiving assistance from the local population along the way.

In order to jointly fight against the Soviets and Chinese, Niyaz and Ma Hushan signed a secret agreement on 15 May. Ma Hushan used the opportunity and moved from Khotan

Hotan (also known as Gosthana, Gaustana, Godana, Godaniya, Khotan, Hetian, Hotien) is a major oasis town in southwestern Xinjiang, an autonomous region in Western China. The city proper of Hotan broke off from the larger Hotan County to become ...

to take over Kashgar from the rebels in June, as promulgated by the agreement. However, 5,000 Soviet troops, including airborne and armoured vehicles were marching towards southern Xinjiang on Sheng's invitation along with Sheng's forces and Dungan Dungan may refer to:

* Donegan, an Irish surname, sometimes spelled Dungan

* Dungan people, a group of Muslim people of Hui origin

** Dungan language

** Dungan, sometimes used to refer to Hui Chinese people generally

* Dungan Mountains in Sibi Di ...

troops.

The Turkic rebels were defeated and Kashgar retook. After the defeat of the Turkic rebels, the Soviets also stopped maintaining the 36th Division. Ma Hushan's administration collapsed. By October 1937, along with the collapse of the Turkic rebellion and the Tungan satrapy, Muslim control over the southern part of the province ended. Soon afterwards, Yulbars Khan troops in Hami were also defeated. Thus, Sheng became the ruler of the whole province for the first time.

1937–38 purges

During the Islamic rebellion, Sheng launched his own purge in Xinjiang to coincide with Stalin's

During the Islamic rebellion, Sheng launched his own purge in Xinjiang to coincide with Stalin's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

. Sheng started the elimination of "traitors", "pan-Turkists", "enemies of the people", "nationalists" and "imperialist spies". His purges swept the entire Uyghur and Hui political elite. The NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

provided the support during the purges. In the later stages of the purge, Sheng turned against the "Trotskyites", mostly a group of Han Chinese sent to him by Moscow. In the group were Soviet General Consul Garegin Apresov

Garegin Abramovich Apresov (russian: Гарегин Абрамович Апресов; 6 January 1890 – 11 September 1941) was a Soviet diplomat, most notable for his tenure in Xinjiang during Sheng Shicai's rule.

Life

Garegin A. Apreso ...

, General Ma Hushan

Ma Hu-shan (Xiao'erjing: , zh, t=馬虎山, s=马虎山, first=t, p=Mǎ Hushān; 1910 – 1954) was a Hui (Chinese Muslim) warlord and the brother-in-law and follower of Ma Chung-ying, a Dungan/Hui Ma Clique warlord. He ruled over an area of ...

, Ma Shaowu, Mahmud Sijan, the official leader of the Xinjiang province Huang Han-chang, and Hoja-Niyaz. Xinjiang came under virtual Soviet control. It is estimated that between 50,000 and 100,000 people perished during the purge.

In 1937, Sheng initiated a three-year plan for reconstruction, for which he received a Soviet loan of 15 million rubles. At Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

's request, Sheng joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

" Hymn of the Bolshevik Party"

, headquarters = 4 Staraya Square, Moscow

, general_secretary = Vladimir Lenin (first) Mikhail Gorbachev (last)

, founded =

, banned =

, founder = Vladimir Lenin

, newspape ...

(CPSU) in August 1938 and received Party Card No.1859118 directly from Molotov during his secret visit to Moscow. However, Sheng did not set up the provincial branch of the CPSU in Xinjiang.

Having eliminated many of his opponents, Sheng's administration had a staff shortage. For this reason, he turned to the Chinese Communists in Ya'an

Ya'an (, Tibetan: Yak-Nga ) is a prefecture-level city in the western part of Sichuan province, China, located just below the Tibetan Plateau. The city is home to Sichuan Agricultural University, the only 211 Project university and the largest ...

for help. In the circumstances of the united front against the Japanese, the Communists sent dozens of its cadres to Xinjiang. The Communists were mostly employed in high-level administrative, financial, educational and cultural ministerial posts in Ürümqi, Kashgar, Khotan and elsewhere, helping to implement Sheng's policies. They also maintained the only open communication line between Ya'an and the Soviet Union. Among those sent by the Communist Party was Mao Zemin, a younger brother of Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

, who served as Deputy Finance Minister.

Nationality policy

During Sheng's rule, the

During Sheng's rule, the Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive v ...

represented only a small minority in Xinjiang. F. Gilbert Chan claimed that they made up only 6% of the population at the time, while Sheng himself during his visit in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

in 1938, told Kliment Voroshilov

Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov (, uk, Климент Охрімович Ворошилов, ''Klyment Okhrimovyč Vorošylov''), popularly known as Klim Voroshilov (russian: link=no, Клим Вороши́лов, ''Klim Vorošilov''; 4 Februa ...

that the Han made around 10% (roughly 400,000 people) of the population of Xinjiang. In his relationship with Xinjiang's non-Han populace, Sheng adopted the Soviet nationality policy. The non-Han nationalities were for the first time included in the provincial government. The first principle of his Declaration of Ten Guiding Principles stated that "all nationalities enjoy equal rights in politics, economy, and education". He also reorganized Xinjiang Daily, the only regional newspaper at the time, to be issued in Mandarin, Uyghur and Kazakh language

The Kazakh or simply Qazaq (Latin: or , Cyrillic: or , Arabic Script: or , , ) is a Turkic language of the Kipchak branch spoken in Central Asia by Kazakhs. It is closely related to Nogai, Kyrgyz and Karakalpak. It is the official langua ...

. The educational programme encouraged the Han to learn Uyghur and the Uyghurs to learn Mandarin. Sheng's nationality policy also entailed the establishment of the Turkic languages

The Turkic languages are a language family of over 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia ( Siberia), and Western Asia. The Turki ...

schools, the revival of madrassas (Islamic schools), the publication of the Turkic languages newspapers and the formation of the Uyghur Progress Union.

Sheng initiated the idea of 14 separate nationalities in Xinjiang, and these were Han Chinese, Uyghurs

The Uyghurs; ; ; ; zh, s=, t=, p=Wéiwú'ěr, IPA: ( ), alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central Asia, Cent ...

, Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

, Kazakhs

The Kazakhs (also spelled Qazaqs; Kazakh: , , , , , ; the English name is transliterated from Russian; russian: казахи) are a Turkic-speaking ethnic group native to northern parts of Central Asia, chiefly Kazakhstan, but also part ...

, Muslims or Dungan Dungan may refer to:

* Donegan, an Irish surname, sometimes spelled Dungan

* Dungan people, a group of Muslim people of Hui origin

** Dungan language

** Dungan, sometimes used to refer to Hui Chinese people generally

* Dungan Mountains in Sibi Di ...

, Sibe, Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politic ...

, Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name. The Later Jin (1616–1636) an ...

, Kyrgyz Kyrgyz, Kirghiz or Kyrgyzstani may refer to:

* Someone or something related to Kyrgyzstan

*Kyrgyz people

*Kyrgyz national games

*Kyrgyz language

*Kyrgyz culture

*Kyrgyz cuisine

*Yenisei Kirghiz

*The Fuyü Gïrgïs language in Northeastern China

...

, White Russian, Taranchi

Taranchi () is a term denoting the Muslim sedentary population living in oases around the Tarim Basin in today's Xinjiang, China, whose native language is Turkic Karluk and whose ancestral heritages include Tocharians, Iranic peoples such ...

, Tajiks

Tajiks ( fa, تاجيک، تاجک, ''Tājīk, Tājek''; tg, Тоҷик) are a Persian-speaking Iranian ethnic group native to Central Asia, living primarily in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Tajiks are the largest ethnicity in Taj ...

, and Uzbeks

The Uzbeks ( uz, , , , ) are a Turkic ethnic group native to the wider Central Asian region, being among the largest Turkic ethnic group in the area. They comprise the majority population of Uzbekistan, next to Kazakh and Karakalpak mino ...

. To foster this idea, he encouraged the establishment of cultural societies for each nationality. The description of Xinjiang as a home of 14 nationalities, both in Xinjiang, as well as in proper China, brought Sheng popularity. However, Sheng's policy was criticized by the Pan-Turkic

Pan-Turkism is a political movement that emerged during the 1880s among Turkic intellectuals who lived in the Russian region of Kazan (Tatarstan), Caucasus (modern-day Azerbaijan) and the Ottoman Empire (modern-day Turkey), with its aim ...

Jadidists and East Turkestan Independence activists Muhammad Amin Bughra

Muhammad Amin Bughra (also Muḥammad Amīn Bughra; ug, مۇھەممەد ئىمىن بۇغرا, محمد أمين بغرا, ; ), sometimes known by his Han name Mao Deming () and his Turkish name Mehmet Emin Buğra; 1901–1965), was a Turkic ...

and Masud Sabri

Masud Sabri, also known as Masʿūd Ṣabrī ( ug, مەسئۇت سابرى, مسعود صبري; zh, s=麦斯武德·沙比尔, t=麥斯武德·沙比爾, p=Màisīwǔdé·Shābì'ěr; 1886–1952), was an ethnic Uyghur politician of the Republi ...

, who rejected the Sheng's imposition of the name "Uyghur people" upon the Turkic people of Xinjiang. They wanted instead the name "Turkic nationality" (''Tujue zu'' in Chinese) to be applied to their people. Sabri also viewed the Hui people

The Hui people ( zh, c=, p=Huízú, w=Hui2-tsu2, Xiao'erjing: , dng, Хуэйзў, ) are an East Asian ethnoreligious group predominantly composed of Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. They are distributed throughout China, mainly in the ...

as Muslim Han Chinese and separate from his own people. Bughra accused Sheng of trying to sow disunion among the Turkic peoples. However, Sheng argued that such separation was necessary in order to guarantee the success of the future union.

Another agenda from the Soviet Union Sheng implemented in Xinjiang was secularization with the purpose of undermining religious influence. Moreover, many Uyghurs and non-Han people were sent for education abroad, most notably in Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of 2 ...

, Uzbek SSR

Uzbekistan (, ) is the common English name for the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR; uz, Ўзбекистон Совет Социалистик Республикаси, Oʻzbekiston Sovet Sotsialistik Respublikasi, in Russian: Уз ...

to the Central Asia University

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center (disambiguation), center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa ...

or Central Asia Military Academy. With their return, these students would find employment as teachers or within the Xinjiang administration.

Sheng's nationality policy served as a basis for the later Communist regime's nationality policy in Xinjiang, with few exceptions.

Relations with the Soviet Union

In March 1935,

In March 1935, Lazar Kaganovich

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich, also Kahanovich (russian: Ла́зарь Моисе́евич Кагано́вич, Lázar' Moiséyevich Kaganóvich; – 25 July 1991), was a Soviet politician and administrator, and one of the main associates of ...

, who headed a newly established commission for developing areas of cooperation with Xinjiang, submitted a proposal to Politburo. Based on these proposals Politburo adopted a number of resolutions. Xinjiang received loans at low-interest rates, various economic assistance, and the sending of numerous consultants and specialists, which strengthened the position of Sheng's regime.

Kaganovich proposed a trade turnover with Xinjiang in 1935 of 9750 thousand rubles, of which 5000 thousand rubles were to come to the share of import, and 4,750 thousand rubles from export operations. Since Kaganovich's proposal was deemed unrealistic, Politburo once again discussed the issue and adopted the resolution "On Trade with Xinjiang" in June. According to the resolution, imports from Xinjiang were reduced, while exports remained the same. The imports from Xinjiang included cotton, wool, leather, livestock, and other raw materials.

The second section of the proposal deals with financial issues. To improve the financial sector of the Xinjiang economy and strengthen the provincial currency, it was proposed to balance the budget as a priority task. To this end, it was envisaged to reduce costs in administrative and managerial and military areas, centralise expenses and tax operations, replace all taxes with general provincial taxes, ban the issuance of counterfeit money, reconstruct a provincial bank, etc.

The proposal's third section were concerned with agriculture and the fourth with transport issues. In that matter, the construction of the main road connecting Xinjiang and the Soviet Union, the increase of cargo transportation along the Ili and Kara Irtysh Rivers and a number of other measures were planned here. These works were later expanded. In October 1937, begun the construction of the Sary-Tash

, native_name_lang = ky

, settlement_type =

, image_skyline = Sary Tash, Kirghizstan.jpg

, image_alt =

, image_caption = Sary Tash village with the Pamir mountains

, image_flag ...

– Sary-Ozek–Ürümqi–Lanzhou

Lanzhou (, ; ) is the capital and largest city of Gansu Province in Northwest China. Located on the banks of the Yellow River, it is a key regional transportation hub, connecting areas further west by rail to the eastern half of the country. H ...

road with a length of 2,925 km, of which 230 km passed through the territory of the Soviet Union, 1,530 km through Xinjiang, and 1,165 km through the province of Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibe ...

. Several thousands of Soviet citizens worked on the construction of the road.

The fifth section of the proposals prepared by the Kaganovich Commission regulated the issues of commodity credit. According to this section, machines and equipment supplied by the Soviets for the industrial enterprises being built and reconstructed in Xinjiang were to be registered as commodity loans.

The document related to the exploration work in Xinjiang stated that "geological exploration of minerals and, first of all, tin, in Xinjiang, was done at the expense of the USSR" and that the People's Commissar of Heavy Industry (NKTP) was to send a geological expedition. The search for tin, tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isol ...

, and molybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element with the symbol Mo and atomic number 42 which is located in period 5 and group 6. The name is from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'', which is based on Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lead ...

was very important for the Soviets, so they established a special expedition for this task.

The sixth section of the proposal dealt with personnel issues. The section suggests that the departments sending advisers and instructors to Xinjiang pay special attention to the qualitative selection of workers sent to Xinjiang. According to the Kaganovich Commission, the number of advisers and instructors sent to Xinjiang, including military consultants and instructors, should not exceed 50 people.

On 11 September 1935, Politburo adopted five resolutions regarding Xinjiang. In the second resolution, it decided to amend the Kaganovich proposal for the establishment of the joint-stock company and to replace it with a special Soviet trading office. Additionally, Politburo discussed the issue of "Xinjiang Oil" and adopted a resolution. The resolution called for the preparation of the development of oil near the Soviet border under the firm of the Xinjiang government. Exploration was carried out in accordance with this decision and in 1938 oil fields were discovered in Shikho. The same year, the joint Xinjiang-Soviet company "Xinjiangneft" was established. Also, General Consul Apresov was given extended powers. Soviet officials in Xinjiang needed his permission to take any action and he could dismiss any Soviet worker "who did not know how to behave in a foreign country". Two days later he was awarded the Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (russian: Орден Ленина, Orden Lenina, ), named after the leader of the Russian October Revolution, was established by the Central Executive Committee on April 6, 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration ...

"for successful work in Xinjiang".

Along with decisions concerning the economy, Politburo also adopted a resolution on the possibility for Xinjiang young people to receive education in the USSR. At first, there was a quota for 15 students, which was expanded to 100 in June 1936. In the 1930s, 30,000 Xinjiang people, preferably Chinese, received education in the various specialties in the Soviet Union.

The resolutions also concerned the reconstruction of the Xinjiang army. The Soviet Union sent equipment and instructors for this end. Xinjiang received aircraft, equipment for aviation, rifle-machine-guns and artillery workshops, uniforms, personal supplies, and other military equipment. Soviets also opened pilot schools to train local airmen. The Soviets also proposed the reduction of army to 10,000 men, but Sheng refused this proposal and instead reduced it to 20,000 men.

In an agreement from 16 May 1935, ratified without consent from the Chinese government, the Soviet government provided substantial financial and material aid, including a five-year loan of five million "gold rubles" (Sheng actually received silver bullion). At about the same time, again without consent from the Chinese government, Soviet geologists started a survey of Xinjiang's mineral resources. The result was Soviet oil drilling at Dushanzi. During Sheng's rule, Xinjiang's trade came under Soviet control. The Soviet General Consul in Ürümqi was effectively in control of governing, with Sheng required to consult them for any decision he made. Alexander Barmine

Alexander Grigoryevich Barmin (russian: Александр Григорьевич Бармин, ''Aleksandr Grigoryevich Barmin''; August 16, 1899 – December 25, 1987), most commonly Alexander Barmine, was an officer in the Soviet Army and dip ...

, the Soviet official responsible for supplying arms to Sheng, wrote that Xinjiang was "a Soviet colony in all but name".

The Soviet stranglehold around Xinjiang was further enhanced through a secret agreement signed on 1 January 1936. The agreement included a Soviet guarantee to come to the aid of Xinjiang "politically, economically and by armed force... in case of some external attack upon the province". By mid-1936, a significant number of Soviet specialists were active in Xinjiang involved in construction, education, health, and military training. The Russian language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic language mainly spoken in Russia. It is the native language of the Russians, and belongs to the Indo-European language family. It is one of four living E ...

replaced English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

as the foreign language taught in schools. A number of Muslim youths, including Muslim girls, were sent to Soviet Central Asia for education. Sheng's government implemented atheistic propaganda, and Muslim women were encouraged to appear in public without a veil.

Approachment to the Chinese government

Between 1934 and 1942, there were no significant relations between the Sheng's government and theChinese government

The Government of the People's Republic of China () is an authoritarian political system in the People's Republic of China under the exclusive political leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It consists of legislative, executive, m ...

. As the full-scale War of Resistance/WWII broke out between China and the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

, the Chinese government entered the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact in a joint war effort against imperial Japan. However, with the German invasion of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, Sheng saw an opportunity to strike down Soviet proxies, the Chinese communists and to mend his relationship with the Chinese government now seated in Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a municipality in Southwest China. The official abbreviation of the city, "" (), was approved by the State Co ...

.

Sheng had long prepared to purge the Chinese communists in Xinjiang. In 1939, his agents filled reports on clandestine meetings, the constant exchange of letters, and the unauthorized content of some of their propaganda. A month after the German invasion, in July 1941, the communist cadre had been demoted or cashiered. Chen Tanqiu, the chief liaison of the Communist Party of China (CCP) reported in

Sheng had long prepared to purge the Chinese communists in Xinjiang. In 1939, his agents filled reports on clandestine meetings, the constant exchange of letters, and the unauthorized content of some of their propaganda. A month after the German invasion, in July 1941, the communist cadre had been demoted or cashiered. Chen Tanqiu, the chief liaison of the Communist Party of China (CCP) reported in Yan'an

Yan'an (; ), alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several counties, including Zhidan (formerly Bao'an) ...

that his relations with Sheng became "extremely cold".

In the same month, the first sign of a thaw in the relationship between Xinjiang and the Chinese government occurred, a month after the German invasion, when Sheng allowed the Chinese diplomat in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

to visit Xinjiang for an official tour.

On 19 March 1942, Sheng's brother Sheng Shiqi was mysteriously murdered. According to one version, the Soviets, fearing that Sheng Shicai might switch sides, tried to overthrow him. The coup started with Sheng Shiqi's murder committed by his wife, convinced to do so by the Soviet agents. The other version is that he was murdered by Sheng Shicai because of his close ties to Moscow. After his brother's death, Sheng continued his crackdown on the Chinese communists. On 1 July 1942 he ordered their relocation in the Ürümqi outskirts for "protection".

On 3 July 1942, a major delegation of the Chinese government's officials arrived at Ürümqi

Ürümqi ( ; also spelled Ürümchi or without umlauts), formerly known as Dihua (also spelled Tihwa), is the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of the People's Republic of China. Ürümqi developed its ...

upon Sheng's invitation. Chiang Kai-Shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

designated Zhu Shaoliang

Zhu Shaoliang or Chu Shao-liang () (1891 – 1963) was a general in the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China.

In 1935, he was hand-picked by Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also kn ...

as a leader of the mission. The mission was initiated by Sheng's younger brother Sheng Shiji a few months earlier. The reaction of the Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...