Shen Kuo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua,

Shen Kuo was born in Qiantang (modern-day

Shen Kuo was born in Qiantang (modern-day

In 1063 Shen Kuo successfully passed the

In 1063 Shen Kuo successfully passed the  At court Shen was a political favorite of the Chancellor

At court Shen was a political favorite of the Chancellor  Although much of Wang Anshi's reforms outlined in the New Policies centered on state finance, land tax reform, and the Imperial examinations, there were also military concerns. This included policies of raising

Although much of Wang Anshi's reforms outlined in the New Policies centered on state finance, land tax reform, and the Imperial examinations, there were also military concerns. This included policies of raising

The new Chancellor Cai Que (; 1036–1093) held Shen responsible for the disaster and loss of life. Along with abandoning the territory which Shen Kuo had fought for, Cai ousted Shen from his seat of office. Shen's life was now forever changed, as he lost his once reputable career in state governance and the military. Shen was then put under probation in a fixed residence for the next six years. However, as he was isolated from governance, he decided to pick up the

The new Chancellor Cai Que (; 1036–1093) held Shen responsible for the disaster and loss of life. Along with abandoning the territory which Shen Kuo had fought for, Cai ousted Shen from his seat of office. Shen's life was now forever changed, as he lost his once reputable career in state governance and the military. Shen was then put under probation in a fixed residence for the next six years. However, as he was isolated from governance, he decided to pick up the

. Beijing Golden Human Computer Co., Ltd. . Retrieved on 2007-08-27. In the 1070s, Shen had purchased a lavish garden estate on the outskirts of modern-day

Joseph Needham suggests that certain pottery vessels of the

Joseph Needham suggests that certain pottery vessels of the

The writing of Shen Kuo is the only source for the date when the drydock was first used in China. Shen Kuo wrote that during the Xi-Ning reign (1068–1077), the court official Huang Huaixin devised a plan for repairing 60 m (200 ft) long

The writing of Shen Kuo is the only source for the date when the drydock was first used in China. Shen Kuo wrote that during the Xi-Ning reign (1068–1077), the court official Huang Huaixin devised a plan for repairing 60 m (200 ft) long

In the broad field of

In the broad field of

However, it was not until the time of Shen Kuo that the earliest

However, it was not until the time of Shen Kuo that the earliest

Many of Shen Kuo's contemporaries were interested in

Many of Shen Kuo's contemporaries were interested in

The ancient Greek

The ancient Greek  It was Shen Kuo who formulated a hypothesis about the process of land formation (

It was Shen Kuo who formulated a hypothesis about the process of land formation (

Early speculation and hypothesis pertaining to what is now known as

Early speculation and hypothesis pertaining to what is now known as

Being the head official for the Bureau of Astronomy, Shen Kuo was an avid scholar of medieval astronomy, and improved the designs of several astronomical instruments. Shen is credited with making improved designs of the

Being the head official for the Bureau of Astronomy, Shen Kuo was an avid scholar of medieval astronomy, and improved the designs of several astronomical instruments. Shen is credited with making improved designs of the  Shen is also known for his cosmological hypotheses in explaining the variations of

Shen is also known for his cosmological hypotheses in explaining the variations of

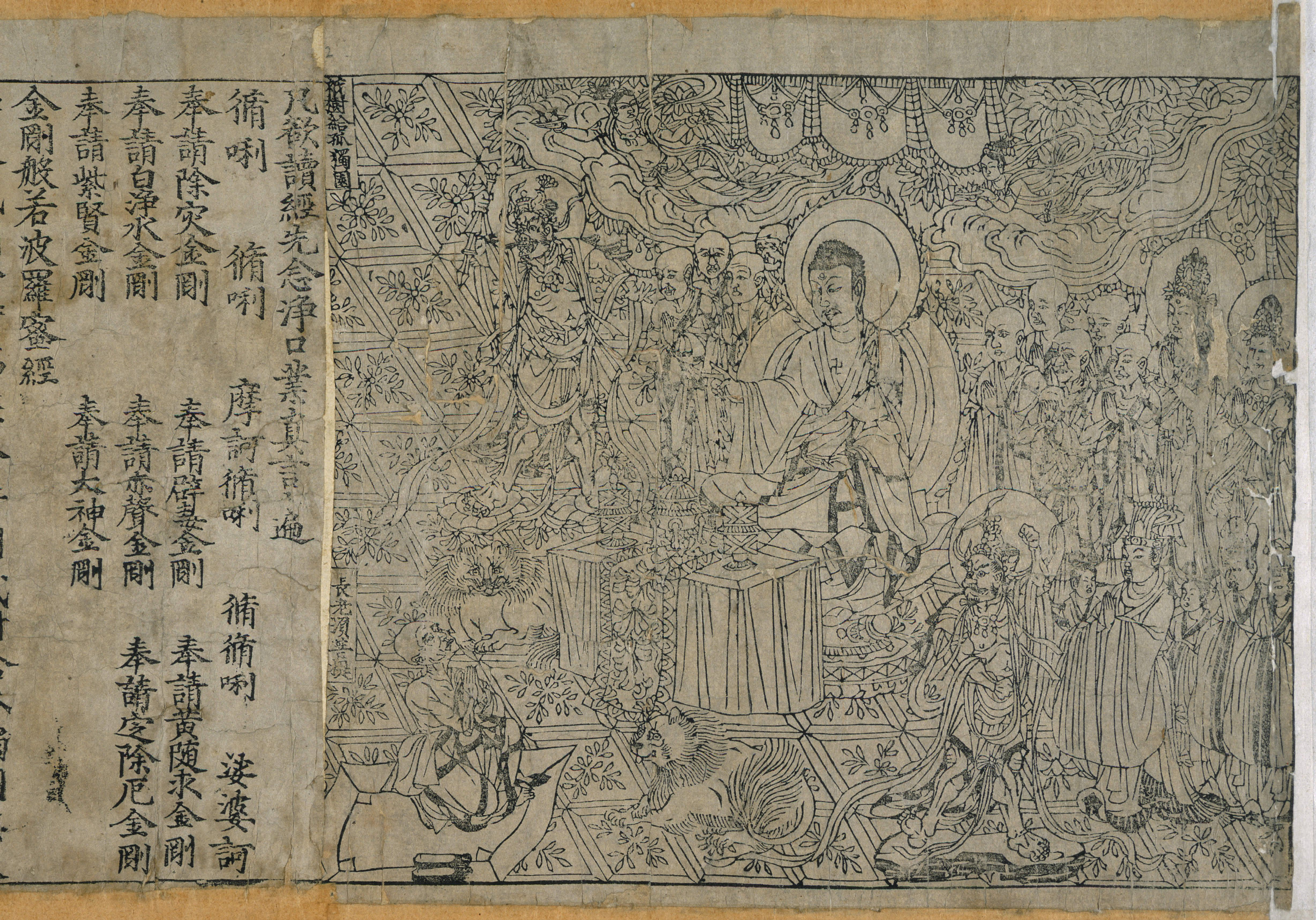

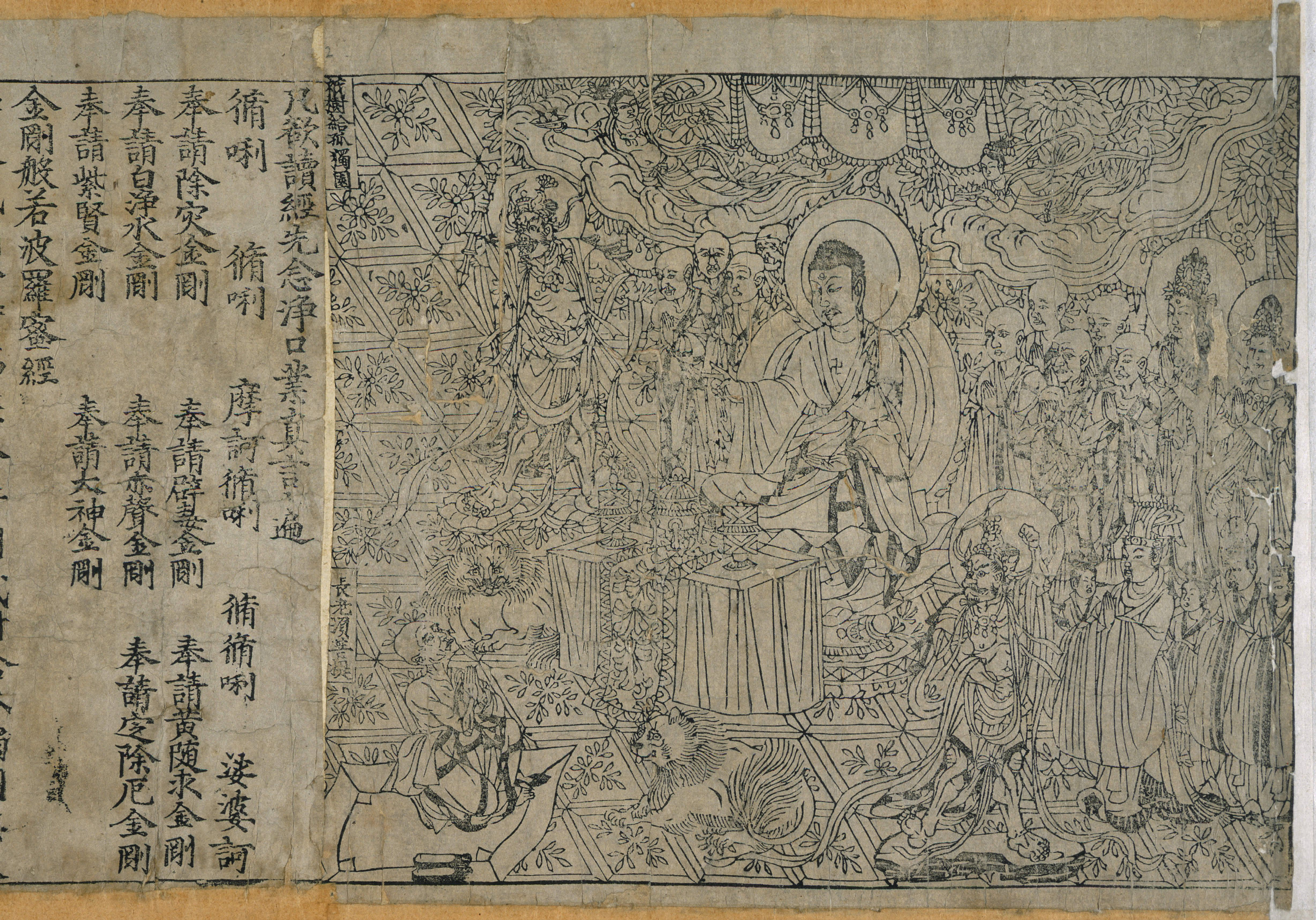

Shen Kuo wrote that during the Qingli reign period (1041–1048), under

Shen Kuo wrote that during the Qingli reign period (1041–1048), under  There are a few surviving examples of books printed in the late Song dynasty using movable type printing.Wu (1943), 211–212. This includes Zhou Bida's ''Notes of The Jade Hall'' () printed in 1193 using the method of baked-clay movable type characters outlined in the ''Dream Pool Essays''. Yao Shu (1201–1278), an advisor to

There are a few surviving examples of books printed in the late Song dynasty using movable type printing.Wu (1943), 211–212. This includes Zhou Bida's ''Notes of The Jade Hall'' () printed in 1193 using the method of baked-clay movable type characters outlined in the ''Dream Pool Essays''. Yao Shu (1201–1278), an advisor to

Shen Kuo was much in favor of philosophical Daoist notions which challenged the authority of empirical science in his day. Although much could be discerned through empirical observation and recorded study, Daoism asserted that the secrets of the universe were boundless, something that scientific investigation could merely express in fragments and partial understandings.Ropp (1990), 170. Shen Kuo referred to the ancient Daoist ''

Shen Kuo was much in favor of philosophical Daoist notions which challenged the authority of empirical science in his day. Although much could be discerned through empirical observation and recorded study, Daoism asserted that the secrets of the universe were boundless, something that scientific investigation could merely express in fragments and partial understandings.Ropp (1990), 170. Shen Kuo referred to the ancient Daoist ''

As an

As an

Although the ''Dream Pool Essays'' is certainly his most extensive and important work, Shen Kuo wrote other books as well. In 1075, Shen Kuo wrote the ''Xining Fengyuan Li'' (; ''The Oblatory Epoch astronomical system of the Splendid Peace reign period''), which was lost, but listed in a 7th chapter of a Song dynasty bibliography.Sivin (1995), III, 46. This was the official report of Shen Kuo on his reforms of the Chinese calendar, which were only partially adopted by the Song court's official calendar system. During his years of retirement from governmental service, Shen Kuo compiled a formulary known as the ''Liang Fang'' (; ''Good medicinal formulas''). Around the year 1126 it was combined with a similar collection by the famous Su Shi (1037–1101), who was ironically a political opponent to Shen Kuo's faction of Reformers and New Policies supporters at court,Sivin (1995), III, 47. yet it was known that Shen Kuo and Su Shi were nonetheless friends and associates.Needham (1986), Volume 1, 137. Shen wrote the ''Mengqi Wanghuai Lu'' (; ''Record of longings forgotten at Dream Brook''), which was also compiled during Shen's retirement. This book was a treatise in the working since his youth on rural life and ethnographic accounts of living conditions in the isolated mountain regions of China.Sivin (1995), III, 48. Only quotations of it survive in the ''Shuo Fu'' () collection, which mostly describe the agricultural implements and tools used by rural people in high mountain regions. Shen Kuo also wrote the ''Changxing Ji'' (; ''Collected Literary Works of he Viscount ofChangxing''). However, this book was without much doubt a posthumous collection, including various poems, prose, and administrative documents written by Shen. By the 15th century (during the

Although the ''Dream Pool Essays'' is certainly his most extensive and important work, Shen Kuo wrote other books as well. In 1075, Shen Kuo wrote the ''Xining Fengyuan Li'' (; ''The Oblatory Epoch astronomical system of the Splendid Peace reign period''), which was lost, but listed in a 7th chapter of a Song dynasty bibliography.Sivin (1995), III, 46. This was the official report of Shen Kuo on his reforms of the Chinese calendar, which were only partially adopted by the Song court's official calendar system. During his years of retirement from governmental service, Shen Kuo compiled a formulary known as the ''Liang Fang'' (; ''Good medicinal formulas''). Around the year 1126 it was combined with a similar collection by the famous Su Shi (1037–1101), who was ironically a political opponent to Shen Kuo's faction of Reformers and New Policies supporters at court,Sivin (1995), III, 47. yet it was known that Shen Kuo and Su Shi were nonetheless friends and associates.Needham (1986), Volume 1, 137. Shen wrote the ''Mengqi Wanghuai Lu'' (; ''Record of longings forgotten at Dream Brook''), which was also compiled during Shen's retirement. This book was a treatise in the working since his youth on rural life and ethnographic accounts of living conditions in the isolated mountain regions of China.Sivin (1995), III, 48. Only quotations of it survive in the ''Shuo Fu'' () collection, which mostly describe the agricultural implements and tools used by rural people in high mountain regions. Shen Kuo also wrote the ''Changxing Ji'' (; ''Collected Literary Works of he Viscount ofChangxing''). However, this book was without much doubt a posthumous collection, including various poems, prose, and administrative documents written by Shen. By the 15th century (during the

Shen Kuo's Tomb

The Yuhang District of Hangzhou Cultural Broadcasting Press and Publications Bureau. Retrieved on 2007-05-06. His tomb was eventually destroyed, yet

Talking Park

The Zhenjiang municipal government office. Retrieved on 2007-05-07. However, the renovated Mengxi Garden is only part of the original of Shen Kuo's time. The Zhenjiang Foreign Experts Bureau (June 2002)

Mengxi Garden

The Zhenjiang Foreign Experts Bureau. Retrieved on 2007-05-07. A

Why the Scientific Revolution Did Not Take Place in China—Or Didn't It?

in ''Transformation and Tradition in the Sciences: Essays in Honor of I. Bernard Cohen'', 531–555, ed. Everett Mendelsohn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . * Sivin, Nathan.

Science and Medicine in Imperial China—The State of the Field

" ''The Journal of Asian Studies'', Vol. 47, No. 1 (Feb., 1988): 41–90. * Stanley-Baker, Joan. "The Development of Brush-Modes in Sung and Yüan," ''Artibus Asiae'' (Volume 39, Number 1, 1977): 13–59. * Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (1997). ''Liao Architecture''. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. * Stock, Jonathan. "A Historical Account of the Chinese Two-Stringed Fiddle Erhu," ''The Galpin Society Journal'' (Volume 46, 1993): 83–113. * Sung, Tz’u, translated by Brian E. McKnight (1981). ''The Washing Away of Wrongs: Forensic Medicine in Thirteenth-Century China''. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. * Tao, Jie, Zheng Bijun and Shirley L. Mow. (2004). ''Holding Up Half the Sky: Chinese Women Past, Present, and Future''. New York: Feminist Press. . * Wu, Kuang Ch'ing. "Ming Printing and Printers," ''Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies'' (February 1943): 203–260. * Yao, Xinzhong. (2003). ''RoutledgeCurzon Encyclopedia of Confucianism: Volume 2, O–Z''. New York: Routledge. . * Zhang, Yunming (1986). ''Isis: The History of Science Society: Ancient Chinese Sulfur Manufacturing Processes''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. According to Sivin (1995), III, 49—historian Nathan Sivin—Zhang's biography on Shen is of great importance as it contains the fullest and most accurate account of Shen Kuo's life.

Shen Kuo at Chinaculture.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shen, Kuo 1031 births 1095 deaths 11th-century antiquarians 11th-century agronomists 11th-century Chinese astronomers 11th-century Chinese historians 11th-century Chinese mathematicians 11th-century Chinese philosophers 11th-century Chinese poets 11th-century diplomats 11th-century geographers 11th-century inventors 11th-century Chinese musicians Agriculturalists Biologists from Zhejiang Chemists from Zhejiang Chinese agronomists Chinese anatomists Chinese antiquarians Chinese antiques experts Chinese archaeologists Chinese art critics 11th-century Chinese scientists Chinese cartographers Chinese civil engineers Chinese climatologists Chinese electrical engineers Chinese encyclopedists Chinese entomologists Chinese ethnographers Chinese geomorphologists Chinese geophysicists Chinese hydrologists Chinese inventors Chinese mechanical engineers Chinese metallurgists Chinese meteorologists Chinese military writers Chinese mineralogists Chinese naturalists Chinese pharmacologists Chinese scientific instrument makers Chinese soil scientists Chinese zoologists Economists from Zhejiang Engineers from Zhejiang Generals from Zhejiang Historians from Zhejiang History of navigation Hydraulic engineers Magneticians Mathematicians from Zhejiang Medieval Chinese geographers Metaphysicians Military strategists Musicians from Hangzhou Optical engineers Optical physicists Philosophers from Zhejiang Physicists from Zhejiang Poets from Zhejiang Politicians from Hangzhou Scientists from Hangzhou Song dynasty Buddhists Song dynasty diplomats Song dynasty essayists Song dynasty generals Song dynasty philosophers Song dynasty poets Song dynasty politicians from Zhejiang Song dynasty science writers Song dynasty Taoists Technical writers Writers from Hangzhou

courtesy name

A courtesy name (), also known as a style name, is a name bestowed upon one at adulthood in addition to one's given name. This practice is a tradition in the East Asian cultural sphere, including China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.Ulrich Theo ...

Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name ( orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individu ...

Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

ic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

(960–1279). Shen was a master in many fields of study including mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultrav ...

, and horology. In his career as a civil servant, he became a finance minister, governmental state inspector, head official for the Bureau of Astronomy in the Song court, Assistant Minister of Imperial Hospitality, and also served as an academic chancellor.Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 2, 33. At court his political allegiance was to the Reformist faction known as the New Policies Group, headed by Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Wang Anshi

Wang Anshi ; ; December 8, 1021 – May 21, 1086), courtesy name Jiefu (), was a Chinese economist, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. He served as chancellor and attempted major and controversial socioeconomic reforms ...

(1021–1085).

In his ''Dream Pool Essays

''The Dream Pool Essays'' (or ''Dream Torrent Essays'') was an extensive book written by the Chinese polymath and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095), published in 1088 during the Song dynasty (960–1279) of China. Shen compiled this encycloped ...

'' or ''Dream Torrent Essays'' (; ''Mengxi Bitan'') of 1088, Shen was the first to describe the magnetic needle compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

, which would be used for navigation (first described in Europe by Alexander Neckam in 1187).Bowman (2000), 599.Mohn (2003), 1. Shen discovered the concept of true north in terms of magnetic declination towards the north pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is the point in the Northern Hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface. It is called the True North Pole to distinguish from the Ma ...

, with experimentation of suspended magnetic needles and "the improved meridian determined by Shen's stronomicalmeasurement of the distance between the pole star and true north".Sivin (1995), III, 22. This was the decisive step in human history to make compasses more useful for navigation, and may have been a concept unknown in Europe for another four hundred years (evidence of German sundials made circa 1450 show markings similar to Chinese geomancers' compasses in regard to declination).Embree (1997), 843.

Alongside his colleague Wei Pu Wei Pu (; Wade-Giles: Wei P'u) was a Chinese astronomer and politician of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD). He was born a commoner, but eventually rose to prominence as an astronomer working for the imperial court at the capital of Kaifeng.Sivin, III ...

, Shen planned to map the orbital paths of the Moon and the planets in an intensive five-year project involving daily observations, yet this was thwarted by political opponents at court. To aid his work in astronomy, Shen Kuo made improved designs of the armillary sphere

An armillary sphere (variations are known as spherical astrolabe, armilla, or armil) is a model of objects in the sky (on the celestial sphere), consisting of a spherical framework of rings, centered on Earth or the Sun, that represent lines of ...

, gnomon

A gnomon (; ) is the part of a sundial that casts a shadow. The term is used for a variety of purposes in mathematics and other fields.

History

A painted stick dating from 2300 BC that was excavated at the astronomical site of Taosi is the ...

, sighting tube, and invented a new type of inflow water clock

A water clock or clepsydra (; ; ) is a timepiece by which time is measured by the regulated flow of liquid into (inflow type) or out from (outflow type) a vessel, and where the amount is then measured.

Water clocks are one of the oldest time- ...

. Shen Kuo devised a geological hypothesis for land formation (geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or ...

), based upon findings of inland marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s, knowledge of soil erosion

Soil erosion is the denudation or wearing away of the upper layer of soil. It is a form of soil degradation. This natural process is caused by the dynamic activity of erosive agents, that is, water, ice (glaciers), snow, air (wind), plants, a ...

, and the deposition

Deposition may refer to:

* Deposition (law), taking testimony outside of court

* Deposition (politics), the removal of a person of authority from political power

* Deposition (university), a widespread initiation ritual for new students practiced f ...

of silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

.Sivin (1995), III, 23–24. He also proposed a hypothesis of gradual climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

, after observing ancient petrified

In geology, petrifaction or petrification () is the process by which organic material becomes a fossil through the replacement of the original material and the filling of the original pore spaces with minerals. Petrified wood typifies this p ...

bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of evergreen perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. The origin of the word "bamboo" is uncertain, ...

s that were preserved underground in a dry northern habitat that would not support bamboo growth in his time. He was the first literary figure in China to mention the use of the drydock to repair boats suspended out of water, and also wrote of the effectiveness of the relatively new invention of the canal pound lock. Although not the first to invent camera obscura, Shen noted the relation of the focal point

Focal point may refer to:

* Focus (optics)

* Focus (geometry)

* Conjugate points, also called focal points

* Focal point (game theory)

* Unicom Focal Point

UNICOM Focal Point is a portfolio management and decision analysis tool used by the p ...

of a concave mirror

A curved mirror is a mirror with a curved reflecting surface. The surface may be either ''convex'' (bulging outward) or ''concave'' (recessed inward). Most curved mirrors have surfaces that are shaped like part of a sphere, but other shapes are ...

and that of the pinhole. Shen wrote extensively about movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation m ...

printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ...

invented by Bi Sheng

Bi Sheng (; 972–1051 AD) was a Chinese artisan, engineer, and inventor of the world's first movable type technology, with printing being one of the Four Great Inventions. Bi Sheng's system was made of Chinese porcelain and was invented betwe ...

(990–1051), and because of his written works the legacy of Bi Sheng and the modern understanding of the earliest movable type has been handed down to later generations. Following an old tradition in China, Shen created a raised-relief map while inspecting borderlands. His description of an ancient crossbow mechanism he unearthed as an amateur archaeologist proved to be a Jacob's staff, a surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

tool which wasn't known in Europe until described by Levi ben Gerson in 1321.

Shen Kuo wrote several other books besides the ''Dream Pool Essays'', yet much of the writing in his other books has not survived. Some of Shen's poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meani ...

was preserved in posthumous written works. Although much of his focus was on technical and scientific issues, he had an interest in divination

Divination (from Latin ''divinare'', 'to foresee, to foretell, to predict, to prophesy') is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history ...

and the supernatural, the latter including his vivid description of unidentified flying objects from eyewitness testimony. He also wrote commentary on ancient Daoist and Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

texts.

Life

Birth and youth

Shen Kuo was born in Qiantang (modern-day

Shen Kuo was born in Qiantang (modern-day Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

) in the year 1031. His father Shen Zhou (; 978–1052) was a somewhat lower-class gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

figure serving in official posts on the provincial level; his mother was from a family of equal status in Suzhou

Suzhou (; ; Suzhounese: ''sou¹ tseu¹'' , Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Soochow, is a major city in southern Jiangsu province, East China. Suzhou is the largest city in Jiangsu, and a major economic center and focal point of trad ...

, with her maiden name being Xu ().Sivin (1995), III, 1. Shen Kuo received his initial childhood education from his mother, which was a common practice in China during this period. She was very educated herself, teaching Kuo and his brother Pi () the military doctrines of her own elder brother Xu Dong (; 975–1016). Since Shen was unable to boast of a prominent familial clan history like many of his elite peers born in the north, he was forced to rely on his wit and stern determination to achieve in his studies, subsequently passing the imperial examinations

The imperial examination (; lit. "subject recommendation") refers to a civil-service examination system in Imperial China, administered for the purpose of selecting candidates for the state bureaucracy. The concept of choosing bureaucrats by ...

and enter the challenging and sophisticated life of an exam-drafted state bureaucrat.

From about 1040 AD, Shen's family moved around Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

province and finally to the international seaport at Xiamen

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong' ...

, where Shen's father accepted minor provincial posts in each new location.Sivin (1995), III, 5. Shen Zhou also served several years in the prestigious capital judiciary

The judiciary (also known as the judicial system, judicature, judicial branch, judiciative branch, and court or judiciary system) is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the law ...

, the equivalent of a national supreme court. Shen Kuo took notice of the various towns and rural features of China as his family traveled, while he became interested during his youth in the diverse topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sc ...

of the land. He also observed the intriguing aspects of his father's engagement in administrative governance and the managerial problems involved; these experiences had a deep impact on him as he later became a government official. Since he often became ill as a child, Shen Kuo also developed a natural curiosity about medicine and pharmaceutics.

Shen Zhou died in the late winter of 1051 (or early 1052), when his son Shen Kuo was 21 years old. Shen Kuo grieved for his father, and following Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

ethics, remained inactive in a state of mourning for three years until 1054 (or early 1055).Sivin (1995), III, 6. As of 1054, Shen began serving in minor local governmental posts. However, his natural abilities to plan, organize, and design were proven early in life; one example is his design and supervision of the hydraulic drainage of an embankment

Embankment may refer to:

Geology and geography

* A levee, an artificial bank raised above the immediately surrounding land to redirect or prevent flooding by a river, lake or sea

* Embankment (earthworks), a raised bank to carry a road, railway ...

system, which converted some one hundred thousand acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

s (400 km2) of swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

land into prime farmland

Agricultural land is typically land ''devoted to'' agriculture, the systematic and controlled use of other forms of lifeparticularly the rearing of livestock and production of cropsto produce food for humans. It is generally synonymous with bo ...

. Shen Kuo noted that the success of the silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Pro ...

method relied upon the effective operation of sluice

Sluice ( ) is a word for a channel controlled at its head by a movable gate which is called a sluice gate. A sluice gate is traditionally a wood or metal barrier sliding in grooves that are set in the sides of the waterway and can be considered ...

gates of irrigation canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface f ...

s.Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 3, 230–231.

Official career

In 1063 Shen Kuo successfully passed the

In 1063 Shen Kuo successfully passed the imperial examinations

The imperial examination (; lit. "subject recommendation") refers to a civil-service examination system in Imperial China, administered for the purpose of selecting candidates for the state bureaucracy. The concept of choosing bureaucrats by ...

, the difficult national-level standard test that every high official was required to pass in order to enter the governmental system. He not only passed the exam however, but was placed into the higher category of the best and brightest students. While serving at Yangzhou

Yangzhou, postal romanization Yangchow, is a prefecture-level city in central Jiangsu Province (Suzhong), East China. Sitting on the north bank of the Yangtze, it borders the provincial capital Nanjing to the southwest, Huai'an to the north, ...

, Shen's brilliance and dutiful character caught the attention of Zhang Chu (; 1015–1080), the Fiscal Intendant of the region. Shen made a lasting impression upon Zhang, who recommended Shen for a court appointment in the financial administration of the central court. Shen would also eventually marry Zhang's daughter, who became his second wife.

In his career as a scholar-official

The scholar-officials, also known as literati, scholar-gentlemen or scholar-bureaucrats (), were government officials and prestigious scholars in Chinese society, forming a distinct social class.

Scholar-officials were politicians and governmen ...

for the central government, Shen Kuo was also an ambassador to the Western Xia

The Western Xia or the Xi Xia (), officially the Great Xia (), also known as the Tangut Empire, and known as ''Mi-nyak''Stein (1972), pp. 70–71. to the Tanguts and Tibetans, was a Tangut-led Buddhist imperial dynasty of China tha ...

dynasty and Liao dynasty

The Liao dynasty (; Khitan: ''Mos Jælud''; ), also known as the Khitan Empire (Khitan: ''Mos diau-d kitai huldʒi gur''), officially the Great Liao (), was an imperial dynasty of China that existed between 916 and 1125, ruled by the Yelü ...

,Steinhardt (1997), 316. a military commander, a director of hydraulic works, and the leading chancellor of the Hanlin Academy

The Hanlin Academy was an academic and administrative institution of higher learning founded in the 8th century Tang China by Emperor Xuanzong in Chang'an.

Membership in the academy was confined to an elite group of scholars, who performed se ...

.Needham (1986), Volume 1, 135. By 1072, Shen was appointed as the head official of the Bureau of Astronomy. With his leadership position in the bureau, Shen was responsible for projects in improving calendrical science,Bowman (2000), 105. and proposed many reforms to the Chinese calendar

The traditional Chinese calendar (also known as the Agricultural Calendar ��曆; 农历; ''Nónglì''; 'farming calendar' Former Calendar ��曆; 旧历; ''Jiùlì'' Traditional Calendar ��曆; 老历; ''Lǎolì'', is a lunisolar calendar ...

alongside the work of his colleague Wei Pu Wei Pu (; Wade-Giles: Wei P'u) was a Chinese astronomer and politician of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD). He was born a commoner, but eventually rose to prominence as an astronomer working for the imperial court at the capital of Kaifeng.Sivin, III ...

.Sivin (1995), III, 18. With his impressive skills and aptitude for matters of economy and finance, Shen was appointed as the Finance Commissioner at the central court.

As written by Li Zhiyi, a man married to Hu Wenrou (granddaughter of Hu Su, a famous minister of the Song dynasty), Shen Kuo was Li's mentor while Shen served as an official.Tao et al. (2004), 19. According to Li's epitaph for his wife, Shen would sometimes relay questions via Li to Hu when he needed clarification for his mathematical work, as Hu Wenrou was esteemed by Shen as a remarkable female mathematician. Shen lamented: "If only she were a man, Wenrou would be my friend."

While employed by the central government, Shen Kuo was also sent out with others to inspect the granary system of the empire, investigating problems of illegal tax-collection, negligence, ineffective disaster relief, and inadequate water-conservancy projects.Hymes & Schirokauer (1993), 109. While Shen was appointed as the regional inspector of Zhejiang in 1073, the Emperor requested that Shen pay a visit to the famous poet Su Shi (1037–1101), then an administrator in Hangzhou.Hartman (1990), 22. Shen took advantage of this meeting to copy some of Su's poetry, which he presented to the Emperor indicating that it expressed "abusive and hateful" speech against the Song court; these poems were later politicized by Li Ding and Shu Dan in order to level a court case against Su. (The Crow Terrace Poetry Trial, of 1079.) With his demonstrations of loyalty and ability, Shen Kuo was awarded the honorary title of a State Foundation Viscount

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicia ...

by Emperor Shenzong of Song

Emperor Shenzong of Song (25 May 1048 – 1 April 1085), personal name Zhao Xu, was the sixth emperor of the Song dynasty of China. His original personal name was Zhao Zhongzhen but he changed it to "Zhao Xu" after his coronation. He reigned ...

(r. 1067–1085), who placed a great amount of trust in Shen Kuo. He was even made 'companion to the heir apparent' (太子中允; 'Taizi zhongyun').

At court Shen was a political favorite of the Chancellor

At court Shen was a political favorite of the Chancellor Wang Anshi

Wang Anshi ; ; December 8, 1021 – May 21, 1086), courtesy name Jiefu (), was a Chinese economist, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. He served as chancellor and attempted major and controversial socioeconomic reforms ...

(1021–1086), who was the leader of the political faction of Reformers, also known as the New Policies Group (, Xin Fa).Sivin (1995), III, 3. Shen Kuo had a previous history with Wang Anshi, since it was Wang who had composed the funerary epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

for Shen's father, Zhou. Shen Kuo soon impressed Wang Anshi with his skills and abilities as an administrator and government agent. In 1072, Shen was sent to supervise Wang's program of surveying the building of silt deposits in the Bian Canal outside the capital city. Using an original technique, Shen successfully dredged the canal and demonstrated the formidable value of the silt gathered as a fertilizer

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

. He gained further reputation at court once he was dispatched as an envoy to the Khitan Liao dynasty in the summer of 1075. The Khitans had made several aggressive negotiations of pushing their borders south, while manipulating several incompetent Song ambassadors who conceded to the Liao Kingdom's demands. In a brilliant display of diplomacy, Shen Kuo came to the camp of the Khitan monarch at Mt. Yongan (near modern Pingquan, Hebei

Hebei or , (; alternately Hopeh) is a northern province of China. Hebei is China's sixth most populous province, with over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. The province is 96% Han Chinese, 3% Manchu, 0.8% Hui, and ...

), armed with copies of previously archived diplomatic negotiations between the Song and Liao dynasties. Shen Kuo refuted Emperor Daozong's bluffs point for point, while the Song reestablished their rightful border line. In regard to the Lý dynasty

The Lý dynasty ( vi, Nhà Lý, , chữ Nôm: 茹李, chữ Hán: 李朝, Hán Việt: ''Lý triều'') was a Vietnamese dynasty that existed from 1009 to 1225. It was established by Lý Công Uẩn when he overthrew the Early Lê dynasty an ...

of Đại Việt (in modern northern Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making ...

), Shen demonstrated in his ''Dream Pool Essays'' that he was familiar with the key players (on the Vietnamese side) in the prelude to the Sino-Vietnamese War of 1075–1077. With his reputable achievements, Shen became a trusted member of Wang Anshi's elite circle of eighteen unofficial core political loyalists to the New Policies Group.

Although much of Wang Anshi's reforms outlined in the New Policies centered on state finance, land tax reform, and the Imperial examinations, there were also military concerns. This included policies of raising

Although much of Wang Anshi's reforms outlined in the New Policies centered on state finance, land tax reform, and the Imperial examinations, there were also military concerns. This included policies of raising militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s to lessen the expense of upholding a million soldiers,Ebrey et al. (2006), 164. putting government monopolies on saltpetre

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt is also known as Indian saltpetre (large deposits of which were historically mined in India). It is an ionic salt of potassium ions K+ and nitra ...

and sulphur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

production and distribution in 1076 (to ensure that gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). T ...

solutions would not fall into the hands of enemies),Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 7, 126.Zhang (1986), 489. and aggressive military policy towards Song's northern rivals of the Western Xia and Liao dynasties.Sivin (1995), III, 4–5. A few years after Song dynasty military forces had made victorious territorial gains against the Tanguts of the Western Xia, in 1080 Shen Kuo was entrusted as a military officer in defense of Yanzhou (modern-day Yan'an

Yan'an (; ), alternatively spelled as Yenan is a prefecture-level city in the Shaanbei region of Shaanxi province, China, bordering Shanxi to the east and Gansu to the west. It administers several counties, including Zhidan (formerly Bao'an) ...

, Shaanxi

Shaanxi (alternatively Shensi, see § Name) is a landlocked province of China. Officially part of Northwest China, it borders the province-level divisions of Shanxi (NE, E), Henan (E), Hubei (SE), Chongqing (S), Sichuan (SW), Gansu (W), N ...

province).Sivin (1995), III, 8. During the autumn months of 1081, Shen was successful in defending Song dynasty territory while capturing several fortified towns of the Western Xia.Sivin (1995), III, 9. The Emperor Shenzong of Song rewarded Shen with numerous titles for his merit in these battles, and in the sixteen months of Shen's military campaign, he received 273 letters from the Emperor. However, Emperor Shenzong trusted an arrogant military officer who disobeyed the emperor and Shen's proposal for strategic fortifications, instead fortifying what Shen considered useless strategic locations. Furthermore, this officer expelled Shen from his commanding post at the main citadel

A citadel is the core fortified area of a town or city. It may be a castle, fortress, or fortified center. The term is a diminutive of "city", meaning "little city", because it is a smaller part of the city of which it is the defensive core.

In ...

, so as to deny him any glory in chance of victory. The result of this was nearly catastrophic, as the forces of the arrogant officer were decimated; Xinzhong Yao states that the death toll was 60,000. Nonetheless, Shen was successful in defending his fortifications and the only possible Tangut invasion-route to Yanzhou.

Impeachment and later life

The new Chancellor Cai Que (; 1036–1093) held Shen responsible for the disaster and loss of life. Along with abandoning the territory which Shen Kuo had fought for, Cai ousted Shen from his seat of office. Shen's life was now forever changed, as he lost his once reputable career in state governance and the military. Shen was then put under probation in a fixed residence for the next six years. However, as he was isolated from governance, he decided to pick up the

The new Chancellor Cai Que (; 1036–1093) held Shen responsible for the disaster and loss of life. Along with abandoning the territory which Shen Kuo had fought for, Cai ousted Shen from his seat of office. Shen's life was now forever changed, as he lost his once reputable career in state governance and the military. Shen was then put under probation in a fixed residence for the next six years. However, as he was isolated from governance, he decided to pick up the ink brush

Ink is a gel, sol, or solution that contains at least one colorant, such as a dye or pigment, and is used to color a surface to produce an image, text, or design. Ink is used for drawing or writing with a pen, brush, reed pen, or quill. ...

and dedicate himself to intensive scholarly studies. After completing two geographical atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geogra ...

es for a state-sponsored program, Shen was rewarded by having his sentence of probation lifted, allowing him to live in a place of his choice. Shen was also pardoned by the court for any previous faults or crimes that were claimed against him.

In his more idle years removed from court affairs, Shen Kuo enjoyed pastimes of the Chinese gentry and literati that would indicate his intellectual level and cultural taste to others.Lian (2001), 24. As described in his ''Dream Pool Essays'', Shen Kuo enjoyed the company of the "nine guests" (九客, ''jiuke''), a figure of speech for the Chinese zither, the older 17x17 line variant of weiqi

Go is an abstract strategy board game for two players in which the aim is to surround more territory than the opponent. The game was invented in China more than 2,500 years ago and is believed to be the oldest board game continuously played to ...

(known today as go), Zen Buddhist meditation, ink (calligraphy

Calligraphy (from el, link=y, καλλιγραφία) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined ...

and painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and a ...

), tea drinking, alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim wo ...

, chanting poetry, conversation, and drinking wine.Lian (2001), 20. These nine activities were an extension to the older so-called Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar

The four arts ( 四 藝, ''siyi''), or the four arts of the Chinese scholar, were the four main academic and artistic talents required of the aristocratic ancient Chinese scholar-gentleman. They were the mastery of the ''qin'' (the guqin, a stri ...

.

According to Zhu Yu's book ''Pingzhou Table Talks'' (; ''Pingzhou Ketan'') of 1119, Shen Kuo had two marriages; the second wife was the daughter of Zhang Chu (), who came from Huainan

Huainan () is a prefecture-level city with 3,033,528 inhabitants as of the 2020 census in north-central Anhui province, China. It is named for the Han-era Principality of Huainan. It borders the provincial capital of Hefei to the south, Lu'an ...

. Lady Zhang was said to be overbearing and fierce, often abusive to Shen Kuo, even attempting at one time to pull off his beard. Shen Kuo's children were often upset over this, and prostrated themselves to Lady Zhang to quit this behavior. Despite this, Lady Zhang went as far as to drive out Shen Kuo's son from his first marriage, expelling him from the household. However, after Lady Zhang died, Shen Kuo fell into a deep depression and even attempted to jump into the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

to drown himself. Although this suicide attempt failed, he would die a year later.Hongen.com (2000–2006). Beijing Golden Human Computer Co., Ltd. . Retrieved on 2007-08-27. In the 1070s, Shen had purchased a lavish garden estate on the outskirts of modern-day

Zhenjiang

Zhenjiang, alternately romanized as Chinkiang, is a prefecture-level city in Jiangsu Province, China. It lies on the southern bank of the Yangtze River near its intersection with the Grand Canal. It is opposite Yangzhou (to its north) a ...

, Jiangsu

Jiangsu (; ; pinyin: Jiāngsū, alternatively romanized as Kiangsu or Chiangsu) is an eastern coastal province of the People's Republic of China. It is one of the leading provinces in finance, education, technology, and tourism, with it ...

province, a place of great beauty which he named "Dream Brook" ("Mengxi") after he visited it for the first time in 1086. Shen Kuo permanently moved to the Dream Brook Estate in 1088, and in that same year he completed his life's written work of the ''Dream Pool Essays

''The Dream Pool Essays'' (or ''Dream Torrent Essays'') was an extensive book written by the Chinese polymath and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095), published in 1088 during the Song dynasty (960–1279) of China. Shen compiled this encycloped ...

'', naming the book after his garden-estate property. It was there that Shen Kuo spent the last several years of his life in leisure, isolation, and illness, until his death in 1095.

Scholarly achievements

Shen Kuo wrote extensively on a wide range of different subjects. His written work included two geographicalatlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geogra ...

es, a treatise on music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspe ...

with mathematical harmonics, governmental administration, mathematical astronomy, astronomical instruments, martial defensive tactics and fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere ...

s, painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and a ...

, tea, medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

, and much poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meani ...

.Sivin (1995), III, 10. His scientific writings have been praised by sinologist

Sinology, or Chinese studies, is an academic discipline that focuses on the study of China primarily through Chinese philosophy, language, literature, culture and history and often refers to Western scholarship. Its origin "may be traced to the ex ...

s such as Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, i ...

and Nathan Sivin, and he has been compared by Sivin to polymaths such as his Song dynasty Chinese contemporary Su Song, as well as to Gottfried Leibniz and Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov (; russian: Михаил (Михайло) Васильевич Ломоносов, p=mʲɪxɐˈil vɐˈsʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ , a=Ru-Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov.ogg; – ) was a Russian polymath, scientist and wr ...

.Sivin (1995), III, 11.

Raised-relief map

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

(202 BC – 220 AD) showing artificial mountains as lid decorations may have influenced the development of the raised-relief map in China. The Han dynasty general Ma Yuan (14 BC – 49 AD) is recorded as having made a raised-relief map of valleys and mountains in a rice-constructed model of 32 AD.Crespigny (2007), 659. Shen Kuo's largest atlas included twenty three maps of China and foreign regions that were drawn at a uniform scale of 1:900,000. Shen also created a raised-relief map using sawdust, wood, beeswax, and wheat paste.Needham (1986), Volume 3, 579–580. Zhu Xi

Zhu Xi (; ; October 18, 1130 – April 23, 1200), formerly romanized Chu Hsi, was a Chinese calligrapher, historian, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. Zhu was influential in the development of Neo-Confucianism. He con ...

(1130–1200) was inspired by the raised-relief map of Huang Shang and so made his own portable map made of wood and clay which could be folded up from eight hinged pieces.

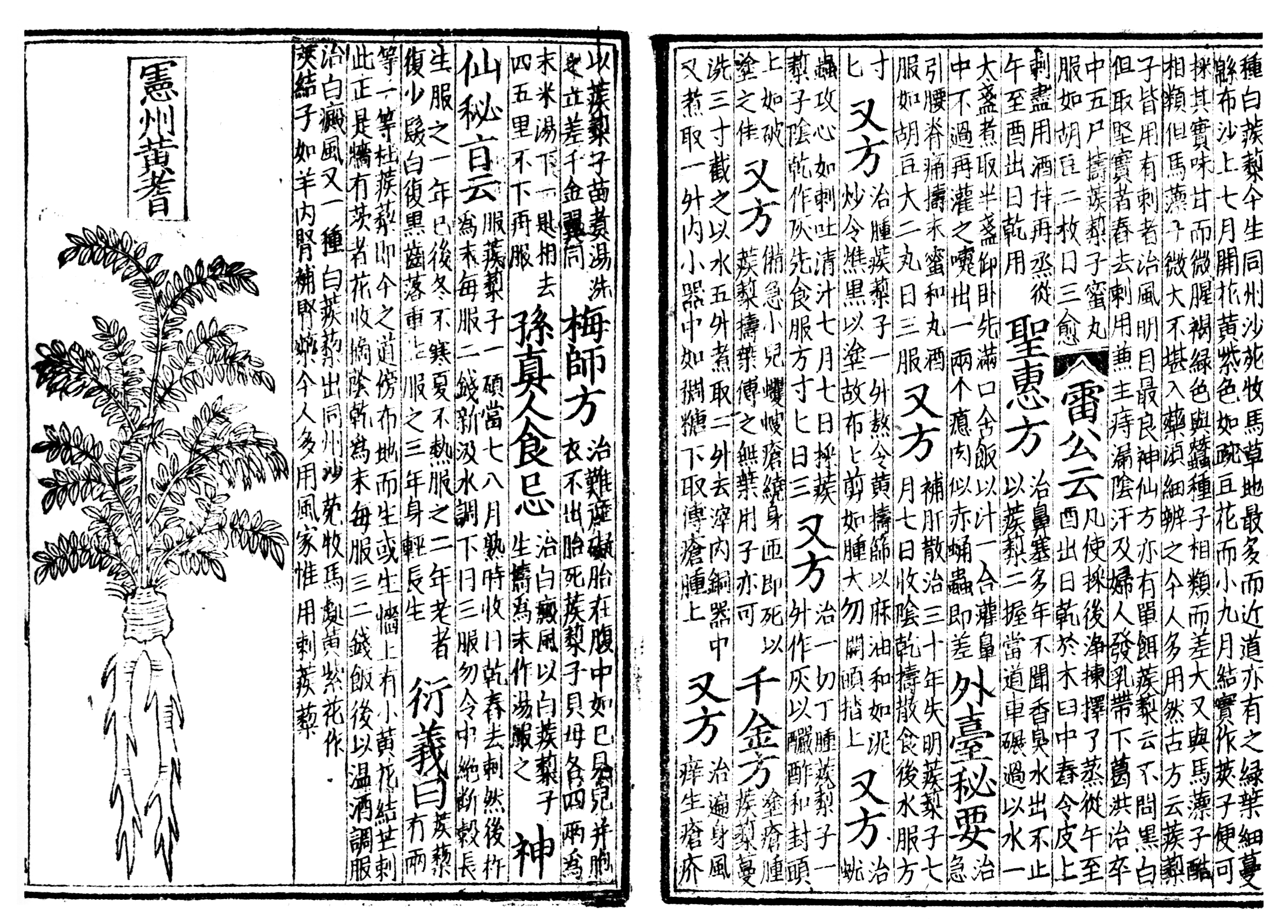

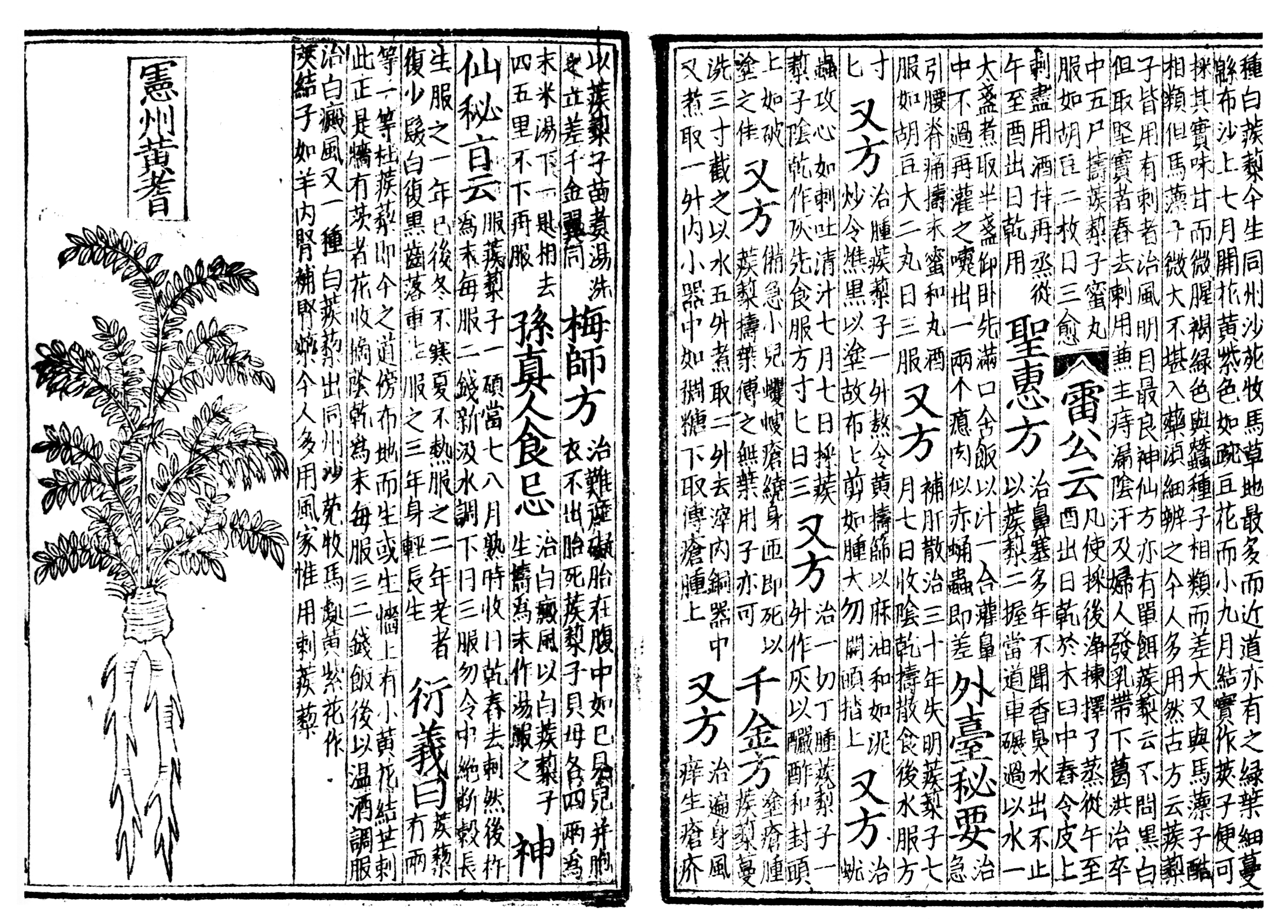

Pharmacology

Forpharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

, Shen wrote of the difficulties of adequate diagnosis

Diagnosis is the identification of the nature and cause of a certain phenomenon. Diagnosis is used in many different disciplines, with variations in the use of logic, analytics, and experience, to determine "cause and effect". In systems engin ...

and therapy

A therapy or medical treatment (often abbreviated tx, Tx, or Tx) is the attempted remediation of a health problem, usually following a medical diagnosis.

As a rule, each therapy has indications and contraindications. There are many differe ...

, as well as the proper selection, preparation, and administration of drugs.Sivin (1995), III, 29. He held great concern for detail and philological accuracy in identification, use and cultivation of different types of medicinal herbs, such as in which months medicinal plants should be gathered, their exact ripening times, which parts should be used for therapy; for domesticated herbs he wrote about planting times, fertilization, and other matters of horticulture

Horticulture is the branch of agriculture that deals with the art, science, technology, and business of plant cultivation. It includes the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, herbs, sprouts, mushrooms, algae, flowers, seaweeds and no ...

. In the realms of botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, an ...

, and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

, Shen Kuo documented and systematically described hundreds of different plants, agricultural crops, rare vegetation, animals, and mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2 ...

s found in China.Needham (1986), Volume 6, Part 1, 475.Needham (1986), Volume 6, Part 1, 499.Needham (1986), Volume 6, Part 1, 501.Sivin (1995), III, 30. For example, Shen noted that the mineral orpiment

Orpiment is a deep-colored, orange-yellow arsenic sulfide mineral with formula . It is found in volcanic fumaroles, low-temperature hydrothermal veins, and hot springs and is formed both by sublimation and as a byproduct of the decay of anothe ...

was used to quickly erase writing errors on paper.

Civil engineering

palatial

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome which ...

boats that were a century old; essentially, Huang Huaixin devised the first Chinese drydock for suspending boats out of water. These boats were then placed in a roof-covered dock warehouse to protect them from weathering.Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 3, 660. Shen also wrote about the effectiveness of the new invention (i.e. by the 10th century engineer Qiao Weiyo) of the pound lock to replace the old flash lock

A flash lock is a type of lock for river or canal transport.

Early locks were designed with a single gate, known as a flash lock or staunch lock. The earliest European references to what were clearly flash locks were in Roman times.

Developm ...

design used in canals. He wrote that it saved the work of five hundred annual labors, annual costs of up to 1,250,000 strings of cash, and increased the size limit of boats accommodated from 21 ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s/21000 kg to 113 ton

Ton is the name of any one of several units of measure. It has a long history and has acquired several meanings and uses.

Mainly it describes units of weight. Confusion can arise because ''ton'' can mean

* the long ton, which is 2,240 pounds

...

s/115000 kg.Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 3, 352.

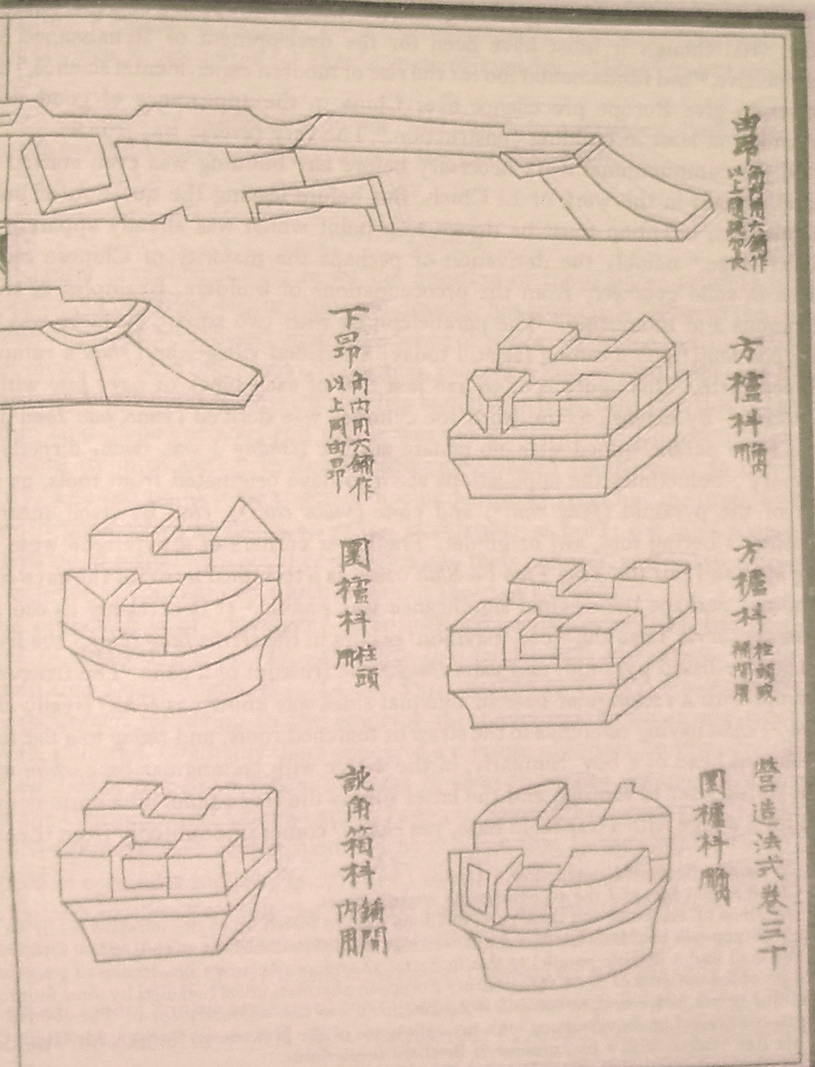

If it were not for Shen Kuo's analysis and quoting in his ''Dream Pool Essays

''The Dream Pool Essays'' (or ''Dream Torrent Essays'') was an extensive book written by the Chinese polymath and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095), published in 1088 during the Song dynasty (960–1279) of China. Shen compiled this encycloped ...

'' of the writings of the architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

Yu Hao

Yu Hao (, 970) was a Chinese architect, structural engineer, and writer during the Song Dynasty.

Legacy

Yu Hao was given the title of Master-Carpenter (Du Liao Jiang) for his architectural skill.Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 81. He wrote the ''Mu J ...

(fl.

''Floruit'' (; abbreviated fl. or occasionally flor.; from Latin for "they flourished") denotes a date or period during which a person was known to have been alive or active. In English, the unabbreviated word may also be used as a noun indicatin ...

970), the latter's work would have been lost to history.Needham (1986), Volume 4, 141. Yu designed a famous wooden pagoda that burned down in 1044 and was replaced in 1049 by a brick pagoda (the ' Iron Pagoda') of similar height, but not of his design. From Shen's quotation—or perhaps Shen's own paraphrasing of Yu Hao's ''Timberwork Manual'' (木經; ''Mujing'')—shows that already in the 10th century there was a graded system of building unit proportions, a system which Shen states had become more precise in his time but stating no one could possibly reproduce such a sound work.Chung (2004), 19. However, he did not anticipate the more complex and matured system of unit proportions embodied in the extensive written work by scholar-official Li Jie (1065–1110), the '' Treatise on Architectural Methods'' (營造法式; ''Yingzao Fashi'') of 1103. Klaas Ruitenbeek states that the version of the ''Timberwork Manual'' quoted by Shen is most likely Shen's summarization of Yu's work or a corrupted passage of the original by Yu Hao, as Shen writes: "According to some, the work was written by Yu Hao."Ruitenbeek (1996), 26.

Anatomy

The Chinese had long taken an interest in examining the human body. For example, in 16 AD, theXin dynasty

The Xin dynasty (; ), also known as Xin Mang () in Chinese historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty which lasted from 9 to 23 AD, established by the Han dynasty consort kin Wang Mang, who usurped the throne of the Emperor Pin ...

usurper Wang Mang

Wang Mang () (c. 45 – 6 October 23 CE), courtesy name Jujun (), was the founder and the only emperor of the short-lived Chinese Xin dynasty. He was originally an official and consort kin of the Han dynasty and later seized the th ...

called for the dissection of an executed man, to examine his arteries and viscera in order to discover cures for illnesses. Shen also took interest in human anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

, dispelling the long-held Chinese theory that the throat contained three valves, writing, "When liquid and solid are imbibed together, how can it be that in one's mouth they sort themselves into two throat channels?"Sivin (1995), III, 30–31. Shen maintained that the larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

was the beginning of a system that distributed vital '' qi'' from the air throughout the body, and that the esophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to t ...

was a simple tube that dropped food into the stomach.Sivin (1995), III, 31. Following Shen's reasoning and correcting the findings of the dissection

Dissection (from Latin ' "to cut to pieces"; also called anatomization) is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause o ...

of executed bandits in 1045, an early 12th-century Chinese account of a bodily dissection finally supported Shen's belief in two throat valves, not three.Sivin (1995), III, 30–31, Footnote 27. Also, the later Song dynasty judge and early forensic expert Song Ci

Song Ci (; 1186–1249) was a Chinese physician, judge, forensic medical scientist, anthropologist, and writer of the Southern Song dynasty. He is most well known for being the world's first forensic entomologist, having recorded his experien ...

(1186–1249) would promote the use of autopsy

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any d ...

in order to solve homicide

Homicide occurs when a person kills another person. A homicide requires only a volitional act or omission that causes the death of another, and thus a homicide may result from accidental, reckless, or negligent acts even if there is no inten ...

cases, as written in his ''Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified

''Collected Cases of Injustice Rectified'' or the ''Washing Away of Wrongs'' is a Chinese book written by Song Ci in 1247 during the Song Dynasty (960-1276) as a handbook for coroners. The author combined many historical cases of forensic scie ...

''.Sung (1981), 12, 19, 20, 72.

Mathematics

In the broad field of

In the broad field of mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, Shen Kuo mastered many practical mathematical problems, including many complex formulas for geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

,Needham (1986), Volume 3, 39. circle packing,Needham (1986), Volume 3, 145. and chords and arcs problems employing trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

.Needham (1986), Volume 3, 109. Shen addressed problems of writing out very large numbers, as large as (104)43. Shen's "technique of small increments" laid the foundation in Chinese mathematics for packing problems involving equal difference series.Katz (2007), 308. Sal Restivo writes that Shen used summation of higher series to ascertain the number of kegs which could be piled in layers in a space shaped like the frustum of a rectangular pyramid.Restivo (1992), 32. In his formula "technique of intersecting circles", he created an approximation of the arc of a circle ''s'' given the diameter ''d'', sagitta ''v'', and length of the chord ''c'' subtending the arc, the length of which he approximated as ''s'' = ''c'' + 2v2/d. Restivo writes that Shen's work in the lengths of arcs of circles provided the basis for spherical trigonometry developed in the 13th century by Guo Shoujing

Guo Shoujing (, 1231–1316), courtesy name Ruosi (), was a Chinese astronomer, hydraulic engineer, mathematician, and politician of the Yuan dynasty. The later Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1591–1666) was so impressed with the preserved astr ...

(1231–1316). He also simplified the counting rods

Counting rods () are small bars, typically 3–14 cm long, that were used by mathematicians for calculation in ancient East Asia. They are placed either horizontally or vertically to represent any integer or rational number.

The written ...

technique by outlining short cuts in algorithm procedures used on the counting board, an idea expanded on by the mathematician Yang Hui

Yang Hui (, ca. 1238–1298), courtesy name Qianguang (), was a Chinese mathematician and writer during the Song dynasty. Originally, from Qiantang (modern Hangzhou, Zhejiang), Yang worked on magic squares, magic circles and the binomial theo ...

(1238–1298).Katz (2007), 308–309. Victor J. Katz asserts that Shen's method of "dividing by 9, increase by 1; dividing by 8, increase by 2," was a direct forerunner to the rhyme scheme method of repeated addition "9, 1, bottom add 1; 9, 2, bottom add 2".Katz (2007), 309.

Shen wrote extensively about what he had learned while working for the state treasury, including mathematical problems posed by computing land tax

A land value tax (LVT) is a levy on the value of land without regard to buildings, personal property and other improvements. It is also known as a location value tax, a point valuation tax, a site valuation tax, split rate tax, or a site-value r ...

, estimating requirements, currency

A currency, "in circulation", from la, currens, -entis, literally meaning "running" or "traversing" is a standardization of money in any form, in use or circulation as a medium of exchange, for example banknotes and coins.

A more general ...

issues, metrology

Metrology is the scientific study of measurement. It establishes a common understanding of units, crucial in linking human activities. Modern metrology has its roots in the French Revolution's political motivation to standardise units in Fran ...

, and so forth.Sivin (1995), III, 12, 14. Shen once computed the amount of terrain

Terrain or relief (also topographical relief) involves the vertical and horizontal dimensions of land surface. The term bathymetry is used to describe underwater relief, while hypsometry studies terrain relative to sea level. The Latin word ...

space required for battle formations in military strategy

Military strategy is a set of ideas implemented by military organizations to pursue desired strategic goals. Derived from the Greek word '' strategos'', the term strategy, when it appeared in use during the 18th century, was seen in its narrow ...

,Sivin (1995), III, 14. and also computed the longest possible military campaign given the limits of human carriers who would bring their own food and food for other soldiers.Ebrey et al. (2006), 162. Shen wrote about the earlier Yi Xing (672–717), a Buddhist monk who applied an early escapement

An escapement is a mechanical linkage in mechanical watches and clocks that gives impulses to the timekeeping element and periodically releases the gear train to move forward, advancing the clock's hands. The impulse action transfers energy ...

mechanism to a water-powered celestial globe

Celestial globes show the apparent positions of the stars in the sky. They omit the Sun, Moon, and planets because the positions of these bodies vary relative to those of the stars, but the ecliptic, along which the Sun moves, is indicated.

...

. By using mathematical permutation

In mathematics, a permutation of a set is, loosely speaking, an arrangement of its members into a sequence or linear order, or if the set is already ordered, a rearrangement of its elements. The word "permutation" also refers to the act or pro ...

s, Shen described Yi Xing's calculation of possible positions on a ''go'' board game. Shen calculated the total number for this using up to five rows and twenty five game pieces, which yielded the number 847,288,609,443.Sivin (1995), III, 15.Needham (1986), Volume 3, 139.

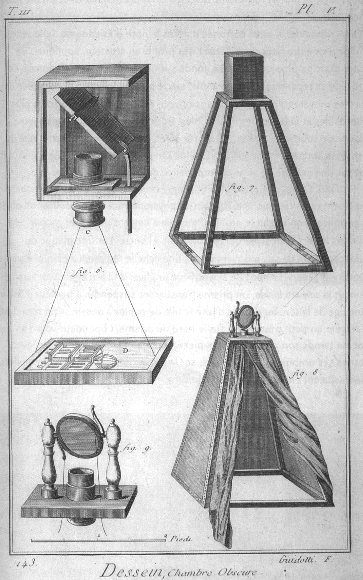

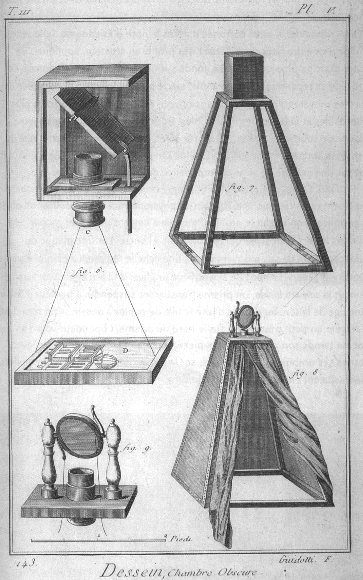

Optics

Shen Kuo experimented with the pinhole camera and burning mirror as the ancient ChineseMohist

Mohism or Moism (, ) was an ancient Chinese philosophy of ethics and logic, rational thought, and science developed by the academic scholars who studied under the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 BC – c. 391 BC), embodied in an eponym ...

s had done in the 4th century BC, as Mozi

Mozi (; ; Latinized as Micius ; – ), original name Mo Di (), was a Chinese philosopher who founded the school of Mohism during the Hundred Schools of Thought period (the early portion of the Warring States period, –221 BCE). The ancie ...

of China's Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in History of China#Ancient China, ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded ...

was perhaps the first to describe the concept of camera obscura, if not his Greek contemporary Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

. The Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

i Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

scientist Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the pr ...

(965–1039) further experimented with camera obscura and was the first to attribute geometrical

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

and quantitative

Quantitative may refer to:

* Quantitative research, scientific investigation of quantitative properties

* Quantitative analysis (disambiguation)

* Quantitative verse, a metrical system in poetry

* Statistics, also known as quantitative analysis

...

properties to it, but Shen was first to note the relationship of the three separate radiation phenomena: the focal point, burning point, and pinhole.Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 98–99. Using a fitting metaphor, Shen compared optical image inversion to an oarlock

A rowlock , sometimes spur (due to the similarity in shape and size), oarlock (USA) or gate, is a brace that attaches an oar to a boat. When a boat is rowed, the rowlock acts as a fulcrum for the oar.

On ordinary rowing craft, the rowlocks are ...

and waisted drum. Along with focal point

Focal point may refer to:

* Focus (optics)

* Focus (geometry)

* Conjugate points, also called focal points

* Focal point (game theory)

* Unicom Focal Point

UNICOM Focal Point is a portfolio management and decision analysis tool used by the p ...

s, he also noted that the image in a concave mirror

A curved mirror is a mirror with a curved reflecting surface. The surface may be either ''convex'' (bulging outward) or ''concave'' (recessed inward). Most curved mirrors have surfaces that are shaped like part of a sphere, but other shapes are ...

is inverted. Shen, who never asserted that he was the first to experiment with camera obscura, hints in his writing that camera obscura was dealt with in the ''Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang

The ''Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang'' () is a book written by Duan Chengshi in the 9th century. It focuses on miscellany of Chinese and foreign legends and hearsay, reports on natural phenomena, short anecdotes, and tales of the wondrous a ...

'' written by Duan Chengshi

Duan Chengshi () (died 863) was a Chinese poet and writer of the Tang Dynasty. He was born to a wealthy family in present-day Zibo, Shandong. A descendant of the early Tang official Duan Zhixuan (, ''Duàn Zhìxuán'') (-642), and the son of Duan ...

(d. 863) during the Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

(618–907), in regard to the inverted image of a Chinese pagoda by a seashore.Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 98. Chinese authors from the 12th to 17th centuries would discuss the optical observations made by Shen Kuo but not advance them further, while Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

(1452–1519) would be the first in Europe to make a similar observation about the focal point and pinhole in camera obscura.

Magnetic needle compass

Since the time of the engineer and inventor Ma Jun (c. 200–265), the Chinese had used the south-pointing chariot, which did not employ magnetism, as a compass. In 1044 the '' Collection of the Most Important Military Techniques'' (; ''Wujing Zongyao'') recorded that fish-shaped objects cut from sheet iron, magnetized by thermoremanence (essentially, heating that produced weak magnetic force), and placed in a water-filled bowl enclosed by a box were used for directional pathfinding alongside the south-pointing chariot.Needham (1986), Volume 4, Part 1, 252. However, it was not until the time of Shen Kuo that the earliest