Sheldon Jackson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sheldon Jackson (May 18, 1834 – May 2, 1909) was a

Jackson found his major life's work in the new territory of

Jackson found his major life's work in the new territory of

correspondence, journals, photographs, photographs, scrapbooks, notebooks and miscellaneous indices and ephemera.

Additional correspondence by Sheldon Jackson is also held at

Digitized page images & text

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

minister, missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

, and political leader

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

. During this career he travelled about one million miles (1.6 million km) and established more than one hundred missions and church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chri ...

es, mostly in the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the We ...

. He performed extensive missionary work in Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of the ...

and the Alaska Territory

The Territory of Alaska or Alaska Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from August 24, 1912, until Alaska was granted statehood on January 3, 1959. The territory was previously Russian America, 1784–1867; th ...

, including his efforts to suppress Native American languages

Over a thousand indigenous languages are spoken by the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. These languages cannot all be demonstrated to be related to each other and are classified into a hundred or so language families (including a large numbe ...

.

Youth, education, early career

Sheldon Jackson was born in 1834 in Minaville in Montgomery County in easternNew York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

. His mother Delia (Sheldon) Jackson was a daughter of New York State Assembly

The New York State Assembly is the lower house of the New York State Legislature, with the New York State Senate being the upper house. There are 150 seats in the Assembly. Assembly members serve two-year terms without term limits.

The Ass ...

Speaker Alexander Sheldon.

Jackson graduated in 1855 from Union College

Union College is a private liberal arts college in Schenectady, New York. Founded in 1795, it was the first institution of higher learning chartered by the New York State Board of Regents, and second in the state of New York, after Columbia Co ...

in Schenectady

Schenectady () is a city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-largest city by population. The city is in eastern New Y ...

, New York, and from the Presbyterian Church's Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a private school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1812 under the auspices of Archibald Alexander, the General Assembly of t ...

in 1858. That same year, he became an ordained Presbyterian minister and married the former Mary Vorhees.

He wanted to become a missionary overseas, but the Presbyterian board told the five foot tall Jackson, who had weak eyesight and was often ill, that he would be better suited for duty in the United States. He first worked in the north-central and western United States, which were still vast and lightly populated areas during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

and thereafter. Jackson's first assignment was at the Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

mission in Oklahoma Territory

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as t ...

, where he worked until poor health forced him to go back East in 1859.

After his recovery, Jackson was appointed to La Crescent in Houston County in southeastern Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over t ...

, where he extended his field hundreds of miles beyond the actual station. He spent ten years in Minnesota and Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, having organized or assisted in the establishment of twenty-three churches.

Jackson traveled as a missionary throughout the American West. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, a huge territory was opened to him. In the summer of 1869, Jackson went on a missionary tour using the railroad and stage lines, establishing a church a day.

Based in Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Jackson became the Presbyterian missions superintendent for Colorado, Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

, Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state ...

, Arizona Territory

The Territory of Arizona (also known as Arizona Territory) was a territory of the United States that existed from February 24, 1863, until February 14, 1912, when the remaining extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state o ...

, and New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomin ...

. From 1872 to 1882, he published the ''Rocky Mountain Presbyterian'' denominational newspaper, which included pictures of places in the West. Ultimately Jackson supervised the building of churches in at least twenty-two Colorado locations, including Greeley, Colorado Springs

Colorado Springs is a home rule municipality in, and the county seat of, El Paso County, Colorado, United States. It is the largest city in El Paso County, with a population of 478,961 at the 2020 United States Census, a 15.02% increase since ...

, Pueblo

In the Southwestern United States, Pueblo (capitalized) refers to the Native tribes of Puebloans having fixed-location communities with permanent buildings which also are called pueblos (lowercased). The Spanish explorers of northern New Spain ...

, Monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, hist ...

, Ouray, and Fairplay in Park County in the central portion of the state. He frequently visited frontier areas to preach, such as the mining camp on Mount Bross in South Park

''South Park'' is an American animated sitcom created by Trey Parker and Matt Stone and developed by Brian Graden for Comedy Central. The series revolves around four boysStan Marsh, Kyle Broflovski, Eric Cartman, and Kenny McCormickand ...

, Colorado.

A friend once said of Jackson and his dedication to the cause of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and relig ...

: "He would not hesitate if he thought he could save an old-hardened sinner, to mount a locomotive and let fly a Gospel message at a group by the wayside while going at a speed of forty miles an hour."Laura King Van Dusen, "Sheldon Jackson's Fairplay Church: One of More than One Hundred in Western U.S.; Jackson Arrested, Jailed in Alaska; Contributed to Settlement of the West", ''Historic Tales from Park County: Parked in the Past'' ( Charleston, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

: The History Press, 2013), , pp. 69-77.

North to Alaska

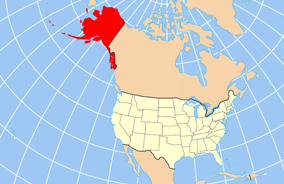

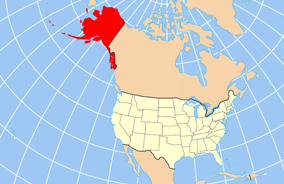

Jackson found his major life's work in the new territory of

Jackson found his major life's work in the new territory of Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

. In 1867, US Secretary of State William H. Seward, during the administration of U.S. President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

, had negotiated the Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase (russian: Продажа Аляски, Prodazha Alyaski, Sale of Alaska) was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a ...

from Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

. The huge territory, with 20,000 miles of coastline, was initially called by many skeptics "Seward's Folly".

In 1877, Jackson began his work in Alaska. He became committed to the Christian spiritual, educational, and economic wellbeing of the Alaska Natives

Alaska Natives (also known as Alaskan Natives, Native Alaskans, Indigenous Alaskans, Aboriginal Alaskans or First Alaskans) are the indigenous peoples of Alaska and include Iñupiat, Yupik, Aleut, Eyak, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, and a num ...

, according to his conception of well-being. He founded numerous schools and training centers that served these native people. At those schools, however, children were punished for speaking in their native languages. His protégés included Edward Marsden

The Rev. Edward Marsden (1869–1932) was a Canadian-American missionary and member of the Tsimshian nation who became the first Alaska Native to be ordained in the ministry.

Early life

He was born May 19, 1869, in Metlakatla, British Columbi ...

, a Tsimshian

The Tsimshian (; tsi, Ts’msyan or Tsm'syen) are an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their communities are mostly in coastal British Columbia in Terrace and Prince Rupert, and Metlakatla, Alaska on Annette Island, the only r ...

missionary among the Tlingit.

Jackson had considerable common ground with another important American in the region. Captain Michael A. Healy of the United States Revenue Cutter Service

)

, colors=

, colors_label=

, march=

, mascot=

, equipment=

, equipment_label=

, battles=

, anniversaries=4 August

, decorations=

, battle_honours=

, battle_honours_label=

, disbanded=28 January 1915

, flying_hours=

, website=

, commander1=

, co ...

, commander of the USRC ''Bear'', was also known for his concern for the native Alaskan Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

. During this time, Captain Healy, primarily of European-American ancestry and the first person of African descent to command a U.S. ship, was essentially the law enforcement officer of the U.S. government in the vast territory. In his twenty years of service between San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

and Point Barrow

Point Barrow or Nuvuk is a headland on the Arctic coast in the U.S. state of Alaska, northeast of Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow). It is the northernmost point of all the territory of the United States, at , south of the North Pole. (The nor ...

, Healy acted as a judge, doctor, and policeman to Alaskan Natives, merchant seamen and whaling crews. His ship also carried doctors and provided the only available trained medical care to many isolated communities. The Native people throughout the vast regions of the north came to know and respect this skipper and called his ship "Healy's Fire Canoe". The ''Bear'' and Captain Healy reportedly inspired author Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

, and are featured prominently, along with Jackson, in James A. Michener

James Albert Michener ( or ; February 3, 1907 – October 16, 1997) was an American writer. He wrote more than 40 books, most of which were long, fictional family sagas covering the lives of many generations in particular geographic locales and ...

's novel, ''Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

''.

Healy and Jackson became allies of a sort. During visits to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

(across the Bering Sea

The Bering Sea (, ; rus, Бе́рингово мо́ре, r=Béringovo móre) is a marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean. It forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasses on Earth: Eurasia and The Am ...

from the Alaskan coast), Healy had observed that the Chukchi people

The Chukchi, or Chukchee ( ckt, Ԓыгъоравэтԓьэт, О'равэтԓьэт, ''Ḷygʺoravètḷʹèt, O'ravètḷʹèt''), are a Siberian indigenous people native to the Chukchi Peninsula, the shores of the Chukchi Sea and the Beri ...

in the remote Asian area had domesticated reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subs ...

and used them for food, travel, and clothing. Recognizing the decline in the seal and whale populations for native consumption because of growing commercial fishing activities, and to aid Eskimos in transportation, Jackson and Healy made numerous trips into Siberia and helped import nearly 1,300 reindeer to bolster the livelihoods of Native people. These became valuable tools in the provision of food, clothing and other necessities for Native peoples. This work was noted in the ''New York Sun

''The New York Sun'' is an American online newspaper published in Manhattan; from 2002 to 2008 it was a daily newspaper distributed in New York City. It debuted on April 16, 2002, adopting the name, motto, and masthead of the earlier New York ...

'' newspaper in 1894.

Jackson was convinced that Americanization was the key to the future of Alaskan Natives. He discouraged the use of indigenous languages, traditional cultural practices, and spiritual celebrations. Because he was worried that Native cultures would vanish with no records of their past (a process which his own educational efforts accelerated), he collected artifacts from those cultures on his many trips throughout the region.

Jackson believed he could further his goals for the Alaskan natives through politics. He became a close friend of U.S. President Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

. He worked toward the passage of the Organic Act

In United States law, an organic act is an act of the United States Congress that establishes a territory of the United States and specifies how it is to be governed, or an agency to manage certain federal lands. In the absence of an organ ...

of 1884, which ensured that Alaska would begin to set up a judicial system and receive aid for education. As a result, Sheldon Jackson was appointed as the First General Agent of Education in Alaska.

Education policy

In 1885, Jackson was appointed General Agent of Education in the Alaska Territory. Concurrent with the values of the expanding colonial administration, Jackson undertook a policy of deliberate acculturation. In particular, Jackson advocated anEnglish-only

The English-only movement, also known as the Official English movement, is a political movement that advocates for the use of only the English language in official United States government operations through the establishment of English as the o ...

policy which forbade the use of indigenous languages. In allocating $25,000 of federal education monies in 1888 he wrote, " books in any Indian language shall be used, or instruction given in that language to Indian pupils." In a letter to newly hired teachers in 1887 he wrote:

: It is the purpose of the government in establishing schools in Alaska to train up English speaking American citizens. ''You will therefore teach in English and give special prominence to instruction in the English language''…. ur teaching should be pervaded by the spirit of the Bible." (emphasis added)

The legacy of Jackson's educational policy is clearly evident in the now precarious state of Alaska's indigenous languages. His policy prohibiting indigenous languages in Alaska schools was enforced from 1910 to 1968. Decades of punishment for speaking Native languages resulted in greatly decreased transmission from one generation to the next, with the result that relatively few indigenous Alaskans speak Native languages in the 21st century.

In March 1885, Judge Ward McAllister Jr. ruled that the contracts Jackson had secured with Tlingit parents, giving up their children for a period of five years for a small sum of money, to be null and void. This greatly reduced the number of students at Jackson's school. Jackson repeatedly sparred with McAllister and the district attorney, and mounted a campaign with President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

's family members to have the officials dismissed. The president dismissed them between May and August of 1885. In May 1885, Jackson was indicted by a grand jury of Russian-Tlingit creoles, in a controversy over land rights. Jackson then found himself in jail for several hours.

Death and legacy

Jackson died on May 2, 1909, in Asheville,North Carolina

North Carolina () is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 28th largest and List of states and territories of the United ...

, sixteen days short of his 75th birthday. He had been planning a trip to Denver at the time of his death to attend meetings three weeks later of the Presbyterian general assembly, to visit some of the chapels that he had built in Colorado, and to renew acquaintances with old friends. He is interred in his hometown of Minaville, New York.

The former Sheldon Jackson College in Sitka

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

, Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

, was named after him. The Sheldon Jackson Museum

Sheldon Jackson College (SJC) was a small private college located on Baranof Island in Sitka, Alaska, United States. Founded in 1878, it was the oldest institution of higher learning in Alaska and maintained a historic relationship with the Pre ...

, on the Sheldon Jackson College grounds, is the oldest concrete

Concrete is a composite material composed of fine and coarse aggregate bonded together with a fluid cement (cement paste) that hardens (cures) over time. Concrete is the second-most-used substance in the world after water, and is the most wid ...

building in the state, and houses much of Sheldon Jackson's collection as well as other examples of Tlingit, Inuit

Inuit (; iu, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ 'the people', singular: Inuk, , dual: Inuuk, ) are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territorie ...

, and Aleut

The Aleuts ( ; russian: Алеуты, Aleuty) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleut people and the islands are politically divided between the ...

culture.

Sheldon Jackson Street is found in the College Village subdivision of Anchorage

Anchorage () is the largest city in the U.S. state of Alaska by population. With a population of 291,247 in 2020, it contains nearly 40% of the state's population. The Anchorage metropolitan area, which includes Anchorage and the neighboring ...

, a neighborhood next to the University of Alaska Anchorage

The University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA) is a public university in Anchorage, Alaska. UAA also administers four community campuses spread across Southcentral Alaska: Kenai Peninsula College, Kodiak College, Matanuska–Susitna College, and Pr ...

campus where the streets are named for colleges and universities (the street forms a loop with Emory Street).

In 1874, while in Fairplay in Park County, Colorado, Jackson built the still standing Sheldon Jackson Memorial Chapel, renamed the South Park Community Church, a one-room Victorian Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

structure, listed in 1977 on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

.

Archival collections

The Presbyterian Historical Society inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, has a collection of Jackson’correspondence, journals, photographs, photographs, scrapbooks, notebooks and miscellaneous indices and ephemera.

Additional correspondence by Sheldon Jackson is also held at

Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a private school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1812 under the auspices of Archibald Alexander, the General Assembly of t ...

.

Jackson’s personal papers include photographs by Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard Muybridge (; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer known for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion, and early work in motion-picture projection. He adopted the first ...

and H.H. Brodeck. The Presbyterian Historical Society also holds the Sheldon Jackson Library, which was Jackson’s personal library donated by him to the historical society. The Sheldon Jackson Museum

Sheldon Jackson College (SJC) was a small private college located on Baranof Island in Sitka, Alaska, United States. Founded in 1878, it was the oldest institution of higher learning in Alaska and maintained a historic relationship with the Pre ...

in Sitka maintains three to four thousand Alaskan artifacts collected by Jackson during his lifetime.

References

Works

* ''Alaska, and missions on the north Pacific coast'' (1880Digitized page images & text

Further reading

*''Alaska and the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service: 1867–1915'', By Truman R. Strobridge, Dennis L. Noble, Published by Naval Institute Press, 1999,External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Jackson, Sheldon 1834 births 1909 deaths 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people) 19th-century Presbyterian ministers American Presbyterian missionaries Christian missionaries in Alaska Christians from Alaska Christians from Colorado Christians from Minnesota People from Denver People from Florida, Montgomery County, New York People from La Crescent, Minnesota People from Park County, Colorado People from Sitka, Alaska People of pre-statehood Alaska Presbyterian Church in the United States of America ministers Presbyterian missionaries in the United States Presbyterianism in Alaska Presbyterians from New York (state) Princeton Theological Seminary alumni Union College (New York) alumni Religious leaders from Colorado Religious leaders from Alaska 19th-century American clergy