Shanghai Ghetto on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Shanghai Ghetto, formally known as the Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees, was an area of approximately one square mile in the Hongkew district of Japanese-occupied

(Shanghai Jewish Center) by the ''Proclamation Concerning Restriction of Residence and Business of Stateless Refugees''. It was one of the poorest and most crowded areas of the city. Local Jewish families and American Jewish charities aided them with shelter, food, and clothing. The Japanese authorities increasingly stepped up restrictions, surrounded the ghetto with barbed wire, and the local Chinese residents, whose living conditions were often as bad, did not leave.

By Kimberly Chun (AsianWeek)

, Murray Frost. By 21 August 1941, the Japanese government closed Shanghai to Jewish immigration.

The refugees who managed to purchase tickets for luxurious Italian and Japanese cruise steamships departing from

The refugees who managed to purchase tickets for luxurious Italian and Japanese cruise steamships departing from

The authorities were unprepared for massive immigration and the arriving refugees faced harsh conditions in the impoverished Hongkou District: 10 per room, near-starvation, disastrous sanitation, and scant employment.

The Baghdadis and later the

The authorities were unprepared for massive immigration and the arriving refugees faced harsh conditions in the impoverished Hongkou District: 10 per room, near-starvation, disastrous sanitation, and scant employment.

The Baghdadis and later the

According to Dr. David Kranzler,

According to Dr. David Kranzler,

Ye Shanghai

62 min. Film and live audio-visual performance by Roberto Paci Dalò created in Shanghai in 2012. Commissioned by Massimo Torrigiani for SH Contemporary - Shanghai Contemporary Art Fair and produced by Davide Quadrio and Francesca Girelli. * ''Harbor from the Holocaust''. Documentary by Violet Du Feng. 56 min. 2020.

Shanghai Jews

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives

''Jewish Voice of the Far East = Juedisches Nachrichtenblatt der Juedischen Gemeinde mitteleuropaeischer Juden in Shanghai''

is a digitized periodical at the

''Medizinische Monatshefte Shanghai = Shanghai medical monthly''

is a digitized periodical at the

''Mitteilungen der Vereinigung der Emigranten-Aerzte in Shanghai (China)''

is a digitized periodical at the

Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

(the ghetto was located in the southern Hongkou

, formerly spelled Hongkew, is a district of Shanghai, forming part of the northern urban core. It has a land area of and a population of 852,476 as of 2010.

It is the location of the Astor House Hotel, Broadway Mansions, Lu Xun Park, and ...

and southwestern Yangpu districts

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions ...

which formed part of the Shanghai International Settlement

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdictio ...

). The area included the community around the Ohel Moshe Synagogue. Shanghai was notable for a long period as the only place in the world that unconditionally offered refuge for Jews escaping from the Nazis. After the Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

ese occupied all of Shanghai in 1941, the Japanese army

The Japan Ground Self-Defense Force ( ja, 陸上自衛隊, Rikujō Jieitai), , also referred to as the Japanese Army, is the land warfare branch of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. Created on July 1, 1954, it is the largest of the three service b ...

forced about 23,000 of the city's Jewish refugees to be restricted or relocated to the Shanghai Ghetto from 1941 to 1945Shanghai Jewish History(Shanghai Jewish Center) by the ''Proclamation Concerning Restriction of Residence and Business of Stateless Refugees''. It was one of the poorest and most crowded areas of the city. Local Jewish families and American Jewish charities aided them with shelter, food, and clothing. The Japanese authorities increasingly stepped up restrictions, surrounded the ghetto with barbed wire, and the local Chinese residents, whose living conditions were often as bad, did not leave.

By Kimberly Chun (AsianWeek)

, Murray Frost. By 21 August 1941, the Japanese government closed Shanghai to Jewish immigration.

Background

Jews in 1930s Germany

At the end of the 1920s, most German Jews were loyal to Germany, assimilated and relatively prosperous. They served in the German army and contributed to every field of German science, business and culture. After theNazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

were elected to power in 1933, state-sponsored anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

persecution such as the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of ...

(1935) and the Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

(1938) drove masses of German Jews to seek asylum abroad, with over 304,500 German Jews choosing to emigrate from 1933–1939. Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israel ...

wrote in 1936, "The world seemed to be divided into two parts—those places where the Jews could not live and those where they could not enter."

During the 1930s, there was a growing military conflict between Japan and China. However in the Shanghai International Settlement

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdictio ...

there existed demilitarized areas which provided safe havens where tens of thousands of European Jewish refugees could escape to from the growing horrors of the holocaust, and also a place where a half million Chinese civilians could find safety.

The Evian Conference

Evian ( , ; , stylized as evian) is a French company that bottles and commercialises mineral water from several sources near Évian-les-Bains, on the south shore of Lake Geneva. It produces over 2 billion plastic bottles per year.

Today, Evia ...

demonstrated that by the end of the 1930s it was almost impossible to find a destination open for Jewish immigration.

According to Dana Janklowicz-Mann:

''Jewish men were being picked up and put intoconcentration camp Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...s. They were told you have ''X'' amount of time to leave—two weeks, a month—if you can find a country that will take you. Outside, their wives and friends were struggling to get a passport, a visa, anything to help them get out. But embassies were closing their doors all over, and countries, including theUnited States The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ..., were closing their borders. ... It started as a rumor inVienna en, Viennese , iso_code = AT-9 , registration_plate = W , postal_code_type = Postal code , postal_code = , timezone = CET , utc_offset = +1 , timezone_DST ...... ‘There's a place you can go where you don't need a visa. They have free entry.’ It just spread like fire and whoever could, went for it.''

Shanghai after 1937

The International Settlement of Shanghai was established by the Treaty of Nanking. Police, jurisdiction and passport control were implemented by the foreign autonomous board. Under theUnequal Treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

between China and European countries, visas were only required to book tickets departing from Europe.

Following the Battle of Shanghai

The Battle of Shanghai () was the first of the twenty-two major engagements fought between the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Republic of China (ROC) and the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) of the Empire of Japan at the beginning of the ...

in 1937, the city was occupied

' ( Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 Octobe ...

by the army of Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

, except for the Shanghai International Settlement

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdictio ...

, which was not occupied by the Japanese until 1941 in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

. Before 1941, with Japanese permission, the Shanghai International Settlement

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdictio ...

allowed entry without visa or passport. By the time when most German Jews arrived, two other Jewish communities had already settled in the city: the wealthy Baghdadi Jews

The former communities of Jewish migrants and their descendants from Baghdad and elsewhere in the Middle East are traditionally called Baghdadi Jews or Iraqi Jews. They settled primarily in the ports and along the trade routes around the Indian ...

, including the Kadoorie

Kaddouri ( ar, خضوري, derived from "green", ''akhdar'' in Arabic; he, כדורי (transliterated; does not mean ''green'', which would be ירוק, yarok)) and many other transliterations, is an Arabic surname. People with the surname inclu ...

and Sassoon families, and the Russian Jews

The history of the Jews in Russia and areas historically connected with it goes back at least 1,500 years. Jews in Russia have historically constituted a large religious and ethnic diaspora; the Russian Empire at one time hosted the largest pop ...

. The latter fled the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

because of anti-Semitic pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

s pushed by the tsarist regime and counter-revolutionary armies as well as the class struggle manifested by the Bolsheviks. They formed the Russian community in Harbin, then the Russian community in Shanghai.

Ho Feng Shan, Chiune Sugihara, Jan Zwartendijk and Tadeusz Romer

In 1935, the Chinese diplomat Ho Feng-Shan started his diplomatic career within the Foreign Ministry of theRepublic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

. His first posting was in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

. He was appointed First Secretary at the Chinese legation

A legation was a diplomatic representative office of lower rank than an embassy. Where an embassy was headed by an ambassador, a legation was headed by a minister. Ambassadors outranked ministers and had precedence at official events. Legations ...

in Vienna in 1937. When Austria was annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in 1938, and the legation was turned into a consulate, Ho was assigned the post of Consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

-General. After the ''Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

'' in 1938, the situation became rapidly more difficult for the almost 200,000 Austrian Jews. The only way for Jews to escape from Nazism was to leave Europe. In order to leave, they had to provide proof of emigration, usually a visa from a foreign nation, or a valid boat ticket. This was difficult, however, because at the 1938 Évian Conference 31 countries (out of a total of 32, which included Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) refused to accept Jewish immigrants. Motivated by humanitarianism, Ho started to issue transit visas to Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

, under Japanese occupation except for foreign concessions. Twelve hundred visas were issued by Ho in only the first three months of holding office as Consul-General.

At the time it was not necessary to have a visa to enter Shanghai, but the visas allowed the Jews to leave Austria. Many Jewish families left for Shanghai, from where most of them would later leave for Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

. Ho continued to issue these visas until he was ordered to return to China in May 1940. The exact number of visas given by Ho to Jewish refugees is unknown. It is known that Ho issued the 200th visa in June 1938 and signed the 1906th visa on 27 October 1938. How many Jews were saved through his actions is unknown, but given that Ho issued nearly 2,000 visas only during his first half year at his post, the number may be in the thousands. Ho died in 1997 and his actions were recognized posthumously when in 2000 the Israeli

Israeli may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the State of Israel

* Israelis, citizens or permanent residents of the State of Israel

* Modern Hebrew, a language

* ''Israeli'' (newspaper), published from 2006 to 2008

* Guni Israeli (b ...

organization Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

decided to award him the title "Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sa ...

".

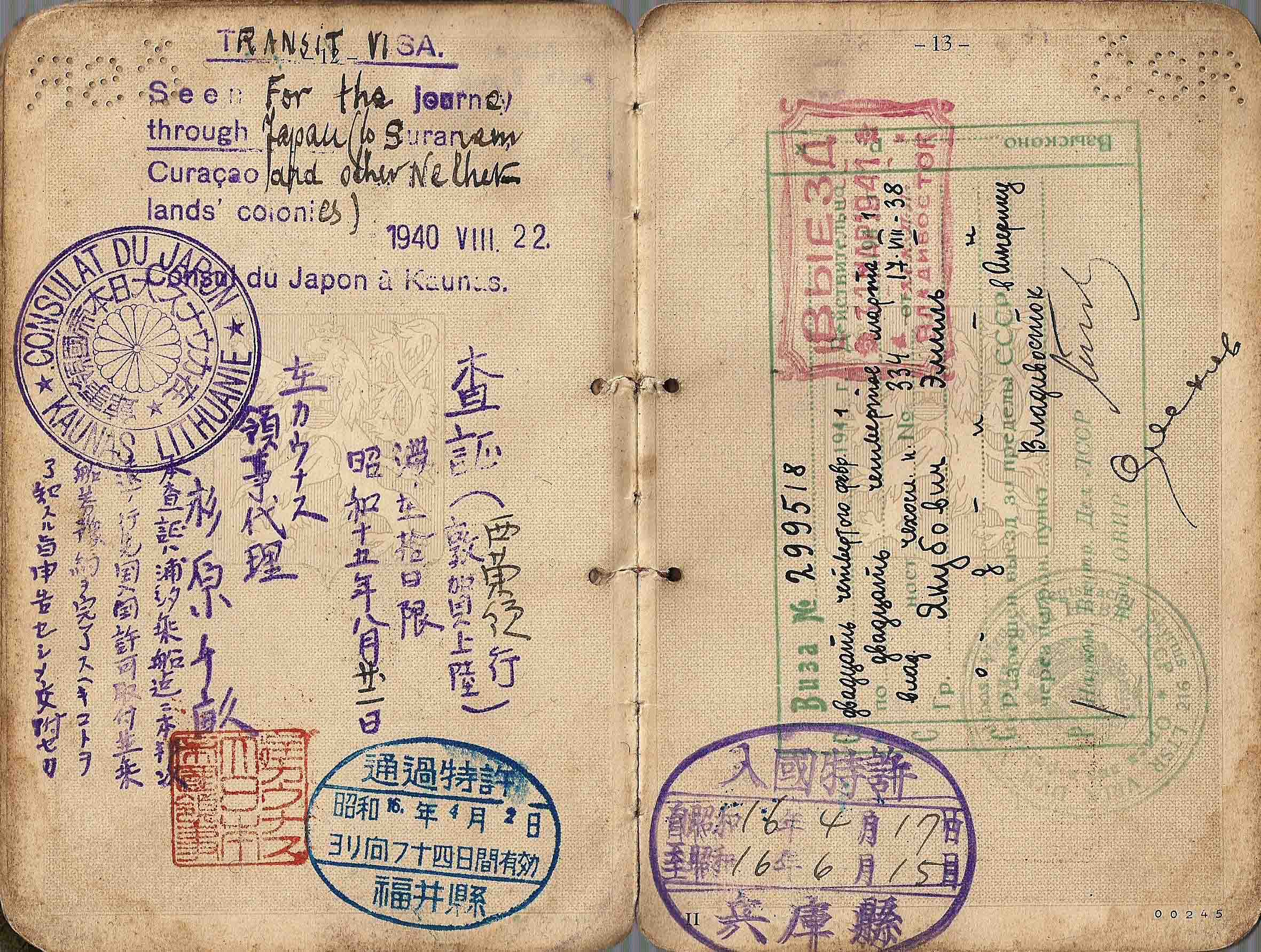

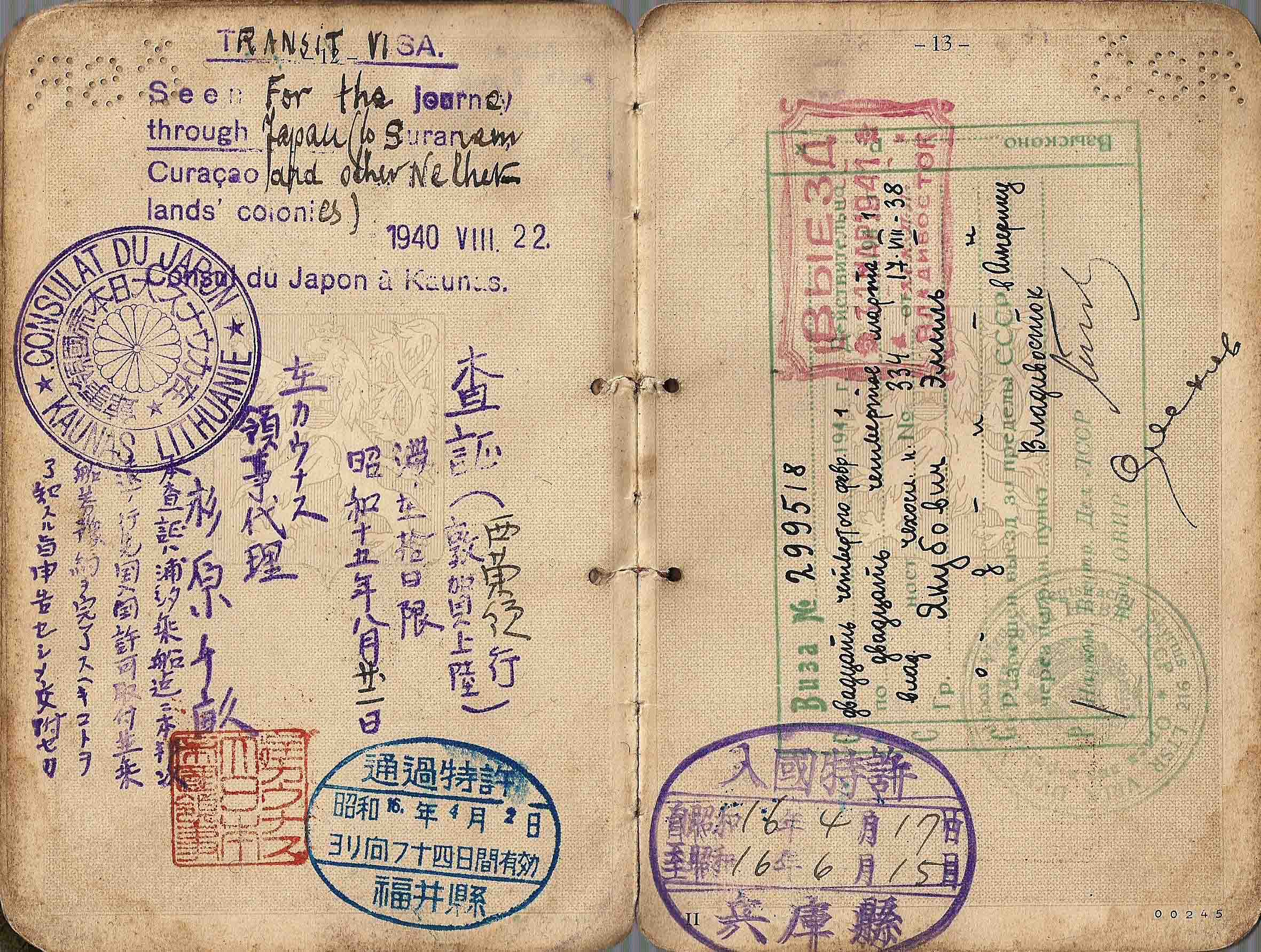

Many in the Polish-Lithuanian Jewish community were additionally saved by Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese consul in Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Traka ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, and Jan Zwartendijk, director of the Philips

Koninklijke Philips N.V. (), commonly shortened to Philips, is a Dutch multinational conglomerate corporation that was founded in Eindhoven in 1891. Since 1997, it has been mostly headquartered in Amsterdam, though the Benelux headquarters is ...

manufacturing plants in Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

and part-time acting consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throu ...

of the Dutch government-in-exile

The Dutch government-in-exile ( nl, Nederlandse regering in ballingschap), also known as the London Cabinet ( nl, Londens kabinet), was the government in exile of the Netherlands, supervised by Queen Wilhelmina, that fled to London after the G ...

. The refugees fled across the vast territory of Russia by train to Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, ...

and then by boat to Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whi ...

in Japan. The refugees, totaling 2,185, arrived in Japan from August 1940 to June 1941.

Tadeusz Romer, the Polish ambassador in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.46 ...

, had managed to get transit visas in Japan, asylum visas to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Burma, immigration certificates to Palestine, and immigrant visas to the United States and some Latin American countries. Tadeusz Romer moved to Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

on November 1, 1941, where he continued to act for Jewish refugees. Among those saved in the Shanghai Ghetto were leaders and students of Mir yeshiva and Tomchei Tmimim

Tomchei Tmimim ( he, תומכי תמימים, "supporters of the complete-wholesome ones") is the central Yeshiva (Talmudical academy) of the Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement. Founded in 1897 in the town of Lubavitch by Rabbi Sholom Do ...

.

Arrival of Ashkenazi Jews

Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

later described their three-week journey with plenty of food and entertainment—between persecution in Germany and squalid ghetto in Shanghai—as surreal. Some passengers attempted to make unscheduled departures in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, hoping to smuggle themselves into the British Mandate of Palestine British Mandate of Palestine or Palestine Mandate most often refers to:

* Mandate for Palestine: a League of Nations mandate under which the British controlled an area which included Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan.

* Mandatory P ...

.

The first German Jewish refugees—twenty-six families, among them five well-known physicians—had already arrived in Shanghai by November 1933. By the spring of 1934, there were reportedly eighty refugee physicians, surgeons, and dentists in China.

On August 15, 1938, the first Jewish refugees from Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germa ...

Austria arrived by Italian ship. Most of the refugees arrived after Kristallnacht

() or the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom(s) (german: Novemberpogrome, ), was a pogrom against Jews carried out by the Nazi Party's (SA) paramilitary and (SS) paramilitary forces along with some participation fro ...

. During the refugee flight to Shanghai between November 1938 and June 1941, the total number of arrivals by sea and land has been estimated at 1,374 in 1938; 12,089 in 1939; 1,988 in 1940; and 4,000 in 1941.

In 1939–1940, Lloyd Triestino ran a sort of "ferry service" between Italy and Shanghai, bringing in thousands of refugees a month - Germans, Austrians, and a few Czechs. Added to this mix were approximately 1,000 Polish Jews in 1941. Among these were the entire faculty of the Mir Yeshiva, some 400 in number, who with the outbreak of World War II in 1939, fled from Mir

''Mir'' (russian: Мир, ; ) was a space station that operated in low Earth orbit from 1986 to 2001, operated by the Soviet Union and later by Russia. ''Mir'' was the first modular space station and was assembled in orbit from 1986 to&n ...

to Vilna

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urba ...

and then to Keidan, Lithuania. In late 1940, they obtained visas from Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese consul in Kaunas

Kaunas (; ; also see other names) is the second-largest city in Lithuania after Vilnius and an important centre of Lithuanian economic, academic, and cultural life. Kaunas was the largest city and the centre of a county in the Duchy of Traka ...

, to travel from Keidan, then Lithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; lt, Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialistiche ...

, via Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

and Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Golden Horn Bay on the Sea of Japan, ...

to Kobe

Kobe ( , ; officially , ) is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture Japan. With a population around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Tokyo and Yokohama. It is located in Kansai region, whi ...

, Japan. By November 1941 the Japanese moved this group and most of the others to the Shanghai Ghetto in order to consolidate the Jews under their control. Finally, a wave of more than 18,000 Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

immigrated to Shanghai; that ended with the Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

by Japan in December 1941.

The Ohel Moshe Synagogue had served as a religious center for the Russian Jewish community since 1907; it is currently the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum

The Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum is a museum commemorating the Jewish refugees who lived in Shanghai during World War II after fleeing Europe to escape the Holocaust. It is located at the former Ohel Moshe or Moishe Synagogue, in the Tilanqia ...

. In April 1941, a modern Ashkenazic Jewish synagogue was built (called the New Synagogue).

Much-needed aid was provided by International Committee for European Immigrants (IC), established by Victor Sassoon

Sir Ellice Victor Sassoon, 3rd Baronet, (20 December 1881 – 13 August 1961) was a businessman and hotelier from the wealthy Baghdadi Jewish Sassoon merchant and banking family.

Biography

Sir Ellice Victor Elias Sassoon was born 30 Decembe ...

and Paul Komor, a Hungarian businessman, and the Committee for the Assistance of European Jewish Refugees (CFA), founded by Horace Kadoorie

Sir Horace Kadoorie, CBE (28 September 1902 – 22 April 1995) was an industrialist, hotelier, and philanthropist.

Early life and education

In 1913–14, he spent a year at Clifton College and was a member of Polacks House; a boarding house so ...

, under the direction of Michael Speelman. These organizations prepared the housing in Hongkou, a relatively cheap suburb compared with the Shanghai International Settlement

The Shanghai International Settlement () originated from the merger in the year 1863 of the British and American enclaves in Shanghai, in which British subjects and American citizens would enjoy extraterritoriality and consular jurisdictio ...

or the Shanghai French Concession

The Shanghai French Concession; ; Shanghainese pronunciation: ''Zånhae Fah Tsuka'', group=lower-alpha was a foreign concession in Shanghai, China from 1849 until 1943, which progressively expanded in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. T ...

. Refugees were accommodated in shabby apartments and six camps in a former school. The Japanese occupiers of Shanghai regarded German Jews as " stateless persons" because Nazi Germany treated them so.

Life in the restricted sector

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, also known as Joint or JDC, is a Jewish relief organization based in New York City. Since 1914 the organisation has supported Jewish people living in Israel and throughout the world. The organization i ...

(JDC) provided some assistance with the housing and food problems. Faced with language barriers, extreme poverty, rampant disease, and isolation, the refugees still were able to transition from being supported by welfare agencies to establishing a functioning community. Jewish cultural life flourished: schools were established, newspapers were published, theaters produced plays, sports teams participated in training and competitions, and even cabarets thrived.

There is evidence that some Jewish men married Chinese women in Shanghai. Although not numerous, “the fact that interracial marriages were able to take place among the relatively conservative Jewish communities demonstrated the considerable degree of cultural interaction between the Jews and the Chinese” in Shanghai.

After Pearl Harbor (1941–1943)

After Japanese forces attackedPearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

, the wealthy Baghdadi Jews

The former communities of Jewish migrants and their descendants from Baghdad and elsewhere in the Middle East are traditionally called Baghdadi Jews or Iraqi Jews. They settled primarily in the ports and along the trade routes around the Indian ...

(many of whom were British subjects) were interned, and American charitable funds ceased. As communication with the US was banned and broken, unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the refe ...

and inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduct ...

intensified, and times got harder for the refugees.

JDC liaison Laura Margolis, who came to Shanghai, attempted to stabilize the situation by getting permission from the Japanese authorities to continue her fundraising effort, turning to the Russian Jews who arrived before 1937 and were exempt from the new restrictions for assistance.

German requests, 1942–1944

During a trial in Germany relating to the Shanghai Ghetto, Fritz Wiedemann reported thatJosef Meisinger

Josef Albert Meisinger (14 September 1899 – 7 March 1947), also known as the "Butcher of Warsaw", was an SS functionary in Nazi Germany. He held a position in the Gestapo and was a member of the Nazi Party. During the early phases of World War ...

had told him that he got the order from Himmler to persuade the Japanese to take measures against the Jews. According to Wiedemann, Meisinger certainly could not have done this in the form of a command to the Japanese.

Since most Japanese were not anti-Semitic, Meisinger used their fear of espionage to achieve his goal. In fall 1942, he conferred with the head of the foreign section of the Japanese Home Ministry

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministr ...

. Meisinger explained that he had orders from Berlin to give the Japanese authorities all the names of "anti-Nazis" among the German community. He explained that "anti-Nazis" were primarily German Jews, of whom 20,000 had emigrated to Shanghai. These "anti-Nazis" were always "anti-Japanese" too.

Later, a subordinate, the interpreter of Meisinger, Karl Hamel, reported to U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) agents that the Japanese, after some consideration, believed in this thesis. According to Hamel, this led to a veritable chase of "anti-Nazis" and to the internment of many people. In response, the Japanese demanded from Meisinger to compile a list of all "anti-Nazis." As his personal secretary later confirmed, this list had already been prepared by Meisinger in 1941. After consulting with General Heinrich Müller in Berlin, it was handed over by Meisinger to the Japanese Home Ministry and to the Kenpeitai

The , also known as Kempeitai, was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945 that also served as a secret police force. In addition, in Japanese-occupied territories, the Kenpeitai arrested or killed those suspec ...

at the end of 1942.

The list contained the names of all Jews with a German passport in Japan. For the Japanese, this official document made clear that, in particular, the large number of refugees who had fled to Shanghai from 1937 onwards represented the highest "risk potential". So the proclamation of a ghetto was just a logical consequence of Meisinger's intervention. This way, Meisinger succeeded, despite the barely existing anti-Semitism of the Japanese, in achieving his goal: The internment of a large part of the Jews in the Japanese sphere of influence. Apparently for this "success", he was promoted Colonel of the police on February 6, 1943, despite the Richard Sorge affair. This information was kept secret by US authorities and was not used in civil proceedings of ghetto inmates to gain redress. That is why, for example, in the case of a woman who was interned in the ghetto, a German court came to the conclusion that even though there was a probability that Meisinger tried to encourage the Japanese to take action against Jews, the establishment of the ghetto in Shanghai was "solely based on Japanese initiative".

On November 15, 1942, the idea of a restricted ghetto was approved after a visit of Shanghai by Meisinger.

As World War II intensified, the Nazis stepped up pressure on Japan to hand over the Shanghai Jews. While the Nazis regarded their Japanese allies as "Honorary Aryans

Honorary Aryan (german: Ehrenarier) was an expression used in Nazi Germany to describe the formal or unofficial status of persons, including some Mischlinge, who were not recognized as belonging to the Aryan race, according to Nazi standards, bu ...

", they were determined that the Final Solution to the Jewish Question would also be applied to the Jews in Shanghai. Warren Kozak describes the episode when the Japanese military governor of the city sent for the Jewish community leaders. The delegation included Amshinover rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

Shimon Sholom Kalish. The Japanese governor was curious and asked, "Why do the Germans hate you so much?"

Without hesitation and knowing the fate of his community hung on his answer, Reb Kalish told the translator (inAccording to another rabbi who was present there, Reb Kalish's answer was "They hate us because we are short and dark-haired." ''Orientalim'' was not likely to have been said because the word is an Israeli academic term in modern Hebrew, not a word in classical Yiddish or Hebrew.Yiddish Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...): "''Zugim weil wir senen orientalim''—Tell him he Germans hate usbecause we areOriental The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of '' Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the ...s." The governor, whose face had been stern throughout the confrontation, broke into a slight smile. In spite of the military alliance, he did not accede to the German demand and the Shanghai Jews were never handed over.

Creation of the Shanghai Ghetto

On February 18, 1943, the occupying Japanese authorities declared a "Designated Area for Stateless Refugees" and ordered those who arrived after 1937 to move their residences and businesses within it by May 18, three months later. The stateless refugees needed permission from the Japanese to dispose of their property; others needed permission to move into the ghetto. About 18,000 Jews were forced to relocate to a 3/4 square mile area of Shanghai's Hongkou district, where many lived in group homes called "Heime" or "Little Vienna". The English version of the order read: While this area was not walled or surrounded with barbed wire, it was patrolled and acurfew

A curfew is a government order specifying a time during which certain regulations apply. Typically, curfews order all people affected by them to ''not'' be in public places or on roads within a certain time frame, typically in the evening and ...

enforced in its precincts. Food was rationed, and everyone needed passes to enter or leave the ghetto.

According to Dr. David Kranzler,

According to Dr. David Kranzler,

Thus, about half of the approximately 16,000 refugees, who had overcome great obstacles and had found a means of livelihood and residence outside the 'designated area' were forced to leave their homes and businesses for a second time and to relocate into a crowded, squalid area of less than one square mile with its own population of an estimated 100,000 Chinese and 8,000 refugees.The US air raids on Shanghai began in 1944. There were no bomb shelters in Hongkou because the water table was close to the surface. The most devastating raid started on July 17, 1945, and was the first attack that hit Hongkou. Thirty-eight refugees and hundreds of Chinese were killed in the 17 July raid. The bombings by the US 7th Air Force continued daily until early August, when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and the Japanese government surrendered shortly thereafter. Refugees in the ghetto improvised their own shelters, with one family surviving the bombing under a bed with a second mattress on top, mounted on two desks. Some Jews of the Shanghai ghetto took part in the

resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objectives ...

. They participated in an underground network to obtain and circulate information and were involved in some minor sabotage and in providing assistance to downed Allied aircrews.

After liberation

The ghetto was officially liberated on September 3, 1945. TheGovernment of Israel

The Cabinet of Israel (officially: he, ממשלת ישראל ''Memshelet Yisrael'') exercises executive authority in the State of Israel. It consists of ministers who are chosen and led by the prime minister. The composition of the governmen ...

bestowed the honor of the Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sa ...

to Chiune Sugihara in 1985 and to Ho Feng Shan in 2001.

Since the establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and China in 1992, the connection between the Jewish people and Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four Direct-administered municipalities of China, direct-administered municipalities of the China, People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the ...

has been recognised in various ways. In 2007, the Israeli consulate-general in Shanghai donated 660,000 Yuan, provided by 26 Israeli companies, to community projects in Hongkou District

, formerly spelled Hongkew, is a district of Shanghai, forming part of the northern urban core. It has a land area of and a population of 852,476 as of 2010.

It is the location of the Astor House Hotel, Broadway Mansions, Lu Xun Park, and H ...

in recognition of the safe harbour provided by the ghetto. The only Jewish monument in Shanghai is located at Huoshan Park (formerly Rabin Park) in Hongkou District.

Partial list of notable refugees in the Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees

* Aaron Avshalomov, Russian composer. * Abba Berman, Haredi rabbi,Rosh yeshiva

Rosh yeshiva ( he, ראש ישיבה, pl. he, ראשי ישיבה, '; Anglicized pl. ''rosh yeshivas'') is the title given to the dean of a yeshiva, a Jewish educational institution that focuses on the study of traditional religious texts, primar ...

.

* Charles K. Bliss, whose Chinese experience inspired him to create Blissymbols

Blissymbols or Blissymbolics is a constructed language conceived as an ideographic writing system called Semantography consisting of several hundred basic symbols, each representing a concept, which can be composed together to generate new symb ...

.

* W. Michael Blumenthal, served as the U.S. Treasury Secretary

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

.

* Morris Cohen, known by his nickname Two-Gun Cohen, he served as bodyguard and aide-de-camp to Sun Yat-sen

Sun Yat-sen (; also known by several other names; 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition . was a Chinese politician who serve ...

, eventually becoming a Chinese general.

* Shaul Eisenberg, who founded and ran the Eisenberg Group of Companies in Israel.

* Kurt Rudolf Fischer, professor at University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest- ...

and University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich hi ...

.

* Eduard Glass, Austrian chess master.

* Leo Hanin, leader of Shanghai Betar

The Betar Movement ( he, תנועת בית"ר), also spelled Beitar (), is a Revisionist Zionist youth movement founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia, by Vladimir (Ze'ev) Jabotinsky. Chapters sprang up across Europe, even during World War II. After ...

.

* Otto Joachim, German composer.

* Shimon Sholom Kalish, Hasidic rebbe of Amshinov–Otvotsk.

* Yisrael Mendel Kaplan, Haredi rabbi, served as Reb Mendel.

* Yechezkel Levenstein, Haredi rabbi, served as Mashgiach Ruchani

A mashgiach ruchani ( he, משגיח רוחני; pl., ''mashgichim ruchani'im'') or mashgicha ruchani – sometimes mashgiach/mashgicha for short – is a spiritual supervisor or guide. He or she is usually a rabbi who has an official position wit ...

.

* Francis Mankiewicz

Francis Mankiewicz (March 15, 1944 in Shanghai, Republic of China, China – August 14, 1993 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada) was a Canadians, Canadian film director, screenwriter and Film producer, producer. In 1945, his family moved to Montreal, ...

, Canadian film director, screenwriter and producer.

* Peter Max

Peter Max (born Peter Max Finkelstein, October 19, 1937) is a German-American artist known for using bright colors in his work. Works by Max are associated with the visual arts and culture of the 1960s, particularly psychedelic art and pop art.

...

, American pop artist.

* Michael Medavoy, a Hollywood executive at Columbia, Orion and TriStar Pictures.

* Rene Rivkin

Rene Walter Rivkin (6 June 1944 – 1 May 2005) was a Chinese-born Australian entrepreneur, investor, investment adviser, and stockbroker. He was convicted of insider trading in 2003 and sentenced to nine months of periodic detention.

Early l ...

, Australian financier.

* Jakob Rosenfeld

Jakob Rosenfeld (January 11, 1903 – April 22, 1952), known in China as General Luo or Luo Shengte, was a Holocaust survivor and urologist who fled to Shanghai, China due to the repression he faced in Austria, which had been annexed by Naz ...

, more commonly known as ''General Luo'', who spent nine years overseeing health care and who served as the Minister of Health in the 1947 Provisional Communist Military Government of China under Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

.

* Hermann Schieberth, a Society photographer in Vienna

* Otto Schnepp, professor at University of Southern California

, mottoeng = "Let whoever earns the palm bear it"

, religious_affiliation = Nonsectarian—historically Methodist

, established =

, accreditation = WSCUC

, type = Private research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $8.1 ...

* Chaim Leib Shmuelevitz

Chaim Leib Halevi Shmuelevitz, ( he, חיים לייב שמואלביץ ;1902–1979) — also spelled Shmulevitz — was a member of the faculty of the Mirrer Yeshiva for more than 40 years, in Poland, Shanghai and Jerusalem, serving as Rosh ...

, Haredi rabbi, served as Rosh yeshiva of the Mirrer Yeshiva in Shanghai (1941–1947), and in Jerusalem (1965–1979).

* John G. Stoessinger, Distinguished Professor of Global Diplomacy at the University of San Diego

The University of San Diego (USD) is a private Roman Catholic research university in San Diego, California. Chartered in July 1949 as the independent San Diego College for Women and San Diego University (comprising the College for Men and Sch ...

* George Szekeres

George Szekeres AM FAA (; 29 May 1911 – 28 August 2005) was a Hungarian–Australian mathematician.

Early years

Szekeres was born in Budapest, Hungary, as Szekeres György and received his degree in chemistry at the Technical University of ...

, professor of mathematics, University of New South Wales

The University of New South Wales (UNSW), also known as UNSW Sydney, is a public research university based in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It is one of the founding members of Group of Eight, a coalition of Australian research-intensiv ...

.

* Sigmund Tobias, professor City University of New York, Fordham University, studied in Mir Yeshiva in Shanghai, President of Northeastern Educational Research Association 1975, President Division of Educational Psychology, American Psychological Association 1987, Distinguished Faculty Fellow US Navy R&D Center San Diego summers 1991-1997, published extensively in professional outlets.

* Laurence Tribe

Laurence Henry Tribe (born October 10, 1941) is an American legal scholar who is a University Professor Emeritus at Harvard University. He previously served as the Carl M. Loeb University Professor at Harvard Law School.

A constitutional law sc ...

, professor, Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

, Carl M. LoeDb University Professor

* George Zames, a control theorist and professor at McGill University

McGill University (french: link=no, Université McGill) is an English-language public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Founded in 1821 by royal charter granted by King George IV,Frost, Stanley Brice. ''McGill Univer ...

, Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

.

See also

*Abraham Kaufman Dr. Abraham Josevich Kaufman (Абрам Иосифович Кауфман, b. November 22, 1885 – d. March 25, 1971) was a Russian-born medical doctor, community organizer and Zionist who helped protect some tens of thousands of Jews seeking saf ...

, a prominent Zionist in China

* ''An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus

was a secret Japanese government report created by the Ministry of Health and Welfare's Institute of Population Problems (now the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research), and completed on July 1, 1943.

The document, co ...

'' (1943)

* History of the Jews in China

Jews and Judaism in China are predominantly composed of Sephardi Jews and their descendants. Other Jewish ethnic divisions are also represented, including Ashkenazi Jews, Mizrahi Jews and a number of converts.

The Jewish Chinese community manif ...

& Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

* Jewish settlement in the Japanese Empire and Fugu Plan, a Japanese plan to bring Jewish refugees to Manchukuo (1934, 1938)

* MS ''St. Louis'' (1939)

* Japan and the Holocaust

* Nanking Safety Zone

Films

* ''Empire of the Sun''. Directed bySteven Spielberg

Steven Allan Spielberg (; born December 18, 1946) is an American director, writer, and producer. A major figure of the New Hollywood era and pioneer of the modern blockbuster, he is the most commercially successful director of all time. Sp ...

. 154 min. 1987.

* ''A Jewish Girl in Shanghai

''A Jewish Girl in Shanghai'' () is a 2010 Chinese animated family film written by Wu Lin and based on his graphic novel of the same name. It is directed by Wang Genfa and Zhang Zhenhui, and voiced by Cui Jie, Zhao Jing and Ma Shaohua.

Set mainl ...

''. Directed by Wang Genfa and Zhang Zhenhui. 80 min. 2010.

* ''The Port of Last Resort: Zuflucht in Shanghai''. Documentary directed by Joan Grossman and Paul Rosdy. 79 min. 1998.

* ''Shanghai Ghetto''. Documentary by Dana Janklowicz-Mann and Amir Mann. 95 min. 2002.

Ye Shanghai

62 min. Film and live audio-visual performance by Roberto Paci Dalò created in Shanghai in 2012. Commissioned by Massimo Torrigiani for SH Contemporary - Shanghai Contemporary Art Fair and produced by Davide Quadrio and Francesca Girelli. * ''Harbor from the Holocaust''. Documentary by Violet Du Feng. 56 min. 2020.

References

Further reading

* Betta, Chiara. "From Orientals to Imagined Britons: Baghdadi Jews in Shanghai." ''Modern Asian Studies'' 37#4 (2003): 999–1023. * Falbaum, Berl, ed. ''Shanghai Remembered...Stories of Jews Who Escaped to Shanghai from Nazi Europe'' (Momentum Books, 2005) , * Headley, Hannelore Heinemann. "Blond China Doll: A Shanghai Interlude, 1939-1953." (Blond China Doll Enterprises), (2004) , * Heppner, Ernest G. ''Shanghai Refuge: A Memoir of the World War II Jewish Ghetto'' (Lincoln:coln University of Nebraska Press: 1993). , * * Kranzler, David. ''Japanese, Nazis & Jews: The Jewish Refugee Community of Shanghai, 1938-1945'' (Yeshiva University Press: 1976). * Malek, Roman. ''From Kaifeng--to Shanghai: Jews in China'' (Steyler Verlag, 2000). * Ristaino, Marcia Reynders. ''Port of Last Resort: The Diaspora Communities of Shanghai'' (Stanford University Press, 2001) * Ross, James R. ''Escape to Shanghai: A Jewish Community in China'' (The Free Press, 1994) * Strobin, Deborah and Ilie Wacs ''An Uncommon Journey: From Vienna to Shanghai to America—A Brother and Sister Escape to Freedom During World War II'' (Barricade Books, 2011) * Tobias, Sigmund. ''Strange Haven: A Jewish Childhood in Wartime Shanghai'' (University of Illinois Press, 1999) * '' Ten Green Bottles (book): The True Story of One Family's Journey from War-torn Austria to the Ghettos of Shanghai'' by Vivian Jeanette Kaplan (St. Martin's Press, 2004) * ''To Wear the Dust of War : From Bialystok to Shanghai to the Promised Land, an Oral History'' by Samuel Iwry, Leslie J.H. Kelley (Editor) (Palgrave Studies in Oral History. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004) *Tokayer, Rabbi Marvin (1979). "The Fugu Plan." New York: Weatherhill, Inc. * Maruyama, Naoki (2005). "Pacific War and Jewish Refugees in Shanghai."(Japanese) Tokyo: Hosei Univ. Press. * ''Survival in Shanghai: The Journals of Fred Marcus 1939-49'' by Audrey Friedman Marcus and Rena Krasno (Pacific View Press, 2008) * ''Far from Where? Jewish Journeys from Shanghai to Australia'' by Antonia Finnane (Melbourne University Press, 1999) * ''Cafe Jause: A Story of Viennese Shanghai'' by Wena Poon (Sutajio Wena, 2015) * *Love and Luck: The story of Jewish Shanghai Ghetto resident, Eva Levi written by her daughter, Karen Levi. * Zhang, Ruoyu (Ed.): ''"Wir in Shanghai" : Pressetexte deutscher und österreichischer Journalisten im Exil (1939-1949)'', München : Iudicium, 021External links

Shanghai Jews

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee Archives

''Jewish Voice of the Far East = Juedisches Nachrichtenblatt der Juedischen Gemeinde mitteleuropaeischer Juden in Shanghai''

is a digitized periodical at the

Leo Baeck Institute

The Leo Baeck Institute, established in 1955, is an international research institute with centres in New York City, London, and Jerusalem that are devoted to the study of the history and culture of German-speaking Jewry. Baeck was its first intern ...

''Medizinische Monatshefte Shanghai = Shanghai medical monthly''

is a digitized periodical at the

Leo Baeck Institute

The Leo Baeck Institute, established in 1955, is an international research institute with centres in New York City, London, and Jerusalem that are devoted to the study of the history and culture of German-speaking Jewry. Baeck was its first intern ...

''Mitteilungen der Vereinigung der Emigranten-Aerzte in Shanghai (China)''

is a digitized periodical at the

Leo Baeck Institute

The Leo Baeck Institute, established in 1955, is an international research institute with centres in New York City, London, and Jerusalem that are devoted to the study of the history and culture of German-speaking Jewry. Baeck was its first intern ...

{{coord, 31, 15, 54, N, 121, 30, 18, E, region:CN-31_type:landmark_source:kolossus-dewiki, display=title

History of Shanghai

Jewish Chinese history

Jewish emigration from Nazi Germany

Jewish Japanese history

International response to the Holocaust

Jewish ghettos

Antisemitism in Japan

Jews and Judaism in Shanghai

Hongkou District