Shah-Nameh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Shahnameh'' or ''Shahnama'' ( fa, شاهنامه, Šāhnāme, lit=The Book of Kings, ) is a long epic poem written by the Persian literature, Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 "distichs" or couplets (two-line verses), the ''Shahnameh'' is one of the world's longest epic poems. It tells mainly the Persian mythology, mythical and to some extent the historical past of the Persian Empire from the creation of the world until the Muslim conquest of Persia, Muslim conquest in the seventh century. Iran, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and the greater Greater Iran, region influenced by Persian culture such as Armenia, Dagestan, Georgia (country), Georgia, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan celebrate this national epic.

The work is of central importance in Persian culture and Persian language, regarded as a literary masterpiece, and definitive of the ethno-national cultural identity of Iran. It is also important to the contemporary adherents of Zoroastrianism, in that it traces the historical links between the beginnings of the religion and the death of the Fall of the Sasanian Empire, last Sasanian emperor, which brought an end to the Zoroastrian influence in Iran.

The ''Shahnameh'' or ''Shahnama'' ( fa, شاهنامه, Šāhnāme, lit=The Book of Kings, ) is a long epic poem written by the Persian literature, Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 "distichs" or couplets (two-line verses), the ''Shahnameh'' is one of the world's longest epic poems. It tells mainly the Persian mythology, mythical and to some extent the historical past of the Persian Empire from the creation of the world until the Muslim conquest of Persia, Muslim conquest in the seventh century. Iran, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and the greater Greater Iran, region influenced by Persian culture such as Armenia, Dagestan, Georgia (country), Georgia, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan celebrate this national epic.

The work is of central importance in Persian culture and Persian language, regarded as a literary masterpiece, and definitive of the ethno-national cultural identity of Iran. It is also important to the contemporary adherents of Zoroastrianism, in that it traces the historical links between the beginnings of the religion and the death of the Fall of the Sasanian Empire, last Sasanian emperor, which brought an end to the Zoroastrian influence in Iran.

This portion of the ''Shahnameh'' is relatively short, amounting to some 2100 verses or four percent of the entire book, and it narrates events with the simplicity, predictability, and swiftness of a historical work.

After an opening in praise of God and Wisdom, the ''Shahnameh'' gives an account of the creation of the world and of man as believed by the Sassanians. This introduction is followed by the story of the first man, Keyumars, who also became the first king after a period of mountain-dwelling. His grandson Hushang, son of Siamak, Sīyāmak, accidentally discovered fire and established the Sadeh Feast in its honor. Stories of Tahmuras, Jamshid, Zahhak, Zahhāk, Kaveh the blacksmith, Kawa or Kaveh the blacksmith, Kaveh, Fereydun, Fereydūn and his three sons Salm (son of Fereydun), Salm, Tur (son of Fereydun), Tur, and Iraj, and his grandson Manuchehr are related in this section.

This portion of the ''Shahnameh'' is relatively short, amounting to some 2100 verses or four percent of the entire book, and it narrates events with the simplicity, predictability, and swiftness of a historical work.

After an opening in praise of God and Wisdom, the ''Shahnameh'' gives an account of the creation of the world and of man as believed by the Sassanians. This introduction is followed by the story of the first man, Keyumars, who also became the first king after a period of mountain-dwelling. His grandson Hushang, son of Siamak, Sīyāmak, accidentally discovered fire and established the Sadeh Feast in its honor. Stories of Tahmuras, Jamshid, Zahhak, Zahhāk, Kaveh the blacksmith, Kawa or Kaveh the blacksmith, Kaveh, Fereydun, Fereydūn and his three sons Salm (son of Fereydun), Salm, Tur (son of Fereydun), Tur, and Iraj, and his grandson Manuchehr are related in this section.

The Shirvanshah dynasty adopted many of their names from the ''Shahnameh''. The relationship between Shirwanshah and his son, Manuchihr, is mentioned in chapter eight of Nizami Ganjavi, Nizami's ''Layla and Majnun, Leili o Majnoon''. Nizami advises the king's son to read the ''Shahnameh'' and to remember the meaningful sayings of the wise.

According to the Turkish historian Mehmet Fuat Köprülü:

Shah Ismail I (d.1524), the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, was also deeply influenced by the Persian literature, Persian literary tradition, particularly by the ''Shahnameh'', which probably explains the fact that he named all of his sons after ''Shahnameh'' characters. Dickson and Welch suggest that Ismail's ''Shāhnāmaye Shāhī'' was intended as a present to the young Tahmasp I, Tahmāsp. After defeating Muhammad Shaybani, Muhammad Shaybāni's Uzbeks, Ismāil asked Hatefi (poet), Hātefī, a famous poet from Ghor Province, Jam (Khorasan), to write a ''Shahnameh''-like epic about his victories and his newly established dynasty. Although the epic was left unfinished, it was an example of ''mathnawis'' in the heroic style of the ''Shahnameh'' written later on for the Safavid kings.

The ''Shahnameh''

The Shirvanshah dynasty adopted many of their names from the ''Shahnameh''. The relationship between Shirwanshah and his son, Manuchihr, is mentioned in chapter eight of Nizami Ganjavi, Nizami's ''Layla and Majnun, Leili o Majnoon''. Nizami advises the king's son to read the ''Shahnameh'' and to remember the meaningful sayings of the wise.

According to the Turkish historian Mehmet Fuat Köprülü:

Shah Ismail I (d.1524), the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, was also deeply influenced by the Persian literature, Persian literary tradition, particularly by the ''Shahnameh'', which probably explains the fact that he named all of his sons after ''Shahnameh'' characters. Dickson and Welch suggest that Ismail's ''Shāhnāmaye Shāhī'' was intended as a present to the young Tahmasp I, Tahmāsp. After defeating Muhammad Shaybani, Muhammad Shaybāni's Uzbeks, Ismāil asked Hatefi (poet), Hātefī, a famous poet from Ghor Province, Jam (Khorasan), to write a ''Shahnameh''-like epic about his victories and his newly established dynasty. Although the epic was left unfinished, it was an example of ''mathnawis'' in the heroic style of the ''Shahnameh'' written later on for the Safavid kings.

The ''Shahnameh''' s influence has extended beyond the Persian sphere. Professor Victoria Arakelova of Yerevan University states:

Jamshid Giunashvili, Jamshid Sh. Giunashvili remarks on the connection of Georgian culture with that of ''Shahnameh'':

Farmanfarmaian in the ''Journal of Persianate Studies'':

Jamshid Giunashvili, Jamshid Sh. Giunashvili remarks on the connection of Georgian culture with that of ''Shahnameh'':

Farmanfarmaian in the ''Journal of Persianate Studies'':

Barbarian Incursions: The Coming of the Turks into the Islamic World

. In ''Islamic Civilization'', ed. D.S. Richards. Oxford, 1973. p. 2. "Firdawsi's Turan are, of course, really Indo-European nomads of Eurasian Steppes... Hence as Kowalski has pointed out, a Turkologist seeking for information in the Shahnama on the primitive culture of the Turks would definitely be disappointed. " Turan, which is the Persian name for the areas of Central Asia beyond the Oxus up to the 7th century (where the story of the ''Shahnameh'' ends), was generally an Iranian-speaking land. According to Richard Frye, "The extent of influence of the Iranian epic is shown by the Turks who accepted it as their own ancient history as well as that of Iran... The Turks were so much influenced by this cycle of stories that in the eleventh century AD we find the Qarakhanid dynasty in Central Asia calling itself the 'family of Afrasiyab' and so it is known in the Islamic history." Turks, as an ethno-linguistic group, have been influenced by the ''Shahnameh'' since advent of Saljuqs. Toghrul III of Seljuqs is said to have recited the ''Shahnameh'' while swinging his mace in battle. According to Ibn Bibi, in 618/1221 the Saljuq of Kayqubad I, Rum Ala' al-Din Kay-kubad decorated the walls of Konya and Sivas with verses from the ''Shahnameh''. The Turks themselves connected their origin not with Turkish tribal history but with the Turan of ''Shahnameh''.Schimmel, Annemarie. "Turk and Hindu: A Poetical Image and Its Application to Historical Fact". In ''Islam and Cultural Change in the Middle Ages'', ed. Speros Vryonis, Jr. Undena Publications, 1975. pp. 107–26. "In fact as much as early rulers felt themselves to be Turks, they connected their Turkish origin not with Turkish tribal history but rather with the Turan of Shahnameh: in the second generation their children bear the name of Firdosi’s heroes, and their Turkish lineage is invariably traced back to Afrasiyab—whether we read Barani in the fourteenth century or the Urdu master poet Ghalib in the nineteenth century. The poets, and through them probably most of the educated class, felt themselves to be the last outpost tied to the civilized world by the thread of Iranianism. The imagery of poetry remained exclusively Persian. " Specifically in India, through the ''Shahnameh'', they felt themselves to be the last outpost tied to the civilized world by the thread of Iranianism.

Ferdowsi concludes the ''Shahnameh'' by writing:

Another translation of by Reza Jamshidi Safa:

This prediction of Ferdowsi has come true and many Persian literary figures, historians and biographers have praised him and the ''Shahnameh''. The ''Shahnameh'' is considered by many to be the most important piece of work in Persian literature.

Western writers have also praised the ''Shahnameh'' and Persian literature in general. Persian literature has been considered by such thinkers as Goethe as one of the four main bodies of world literature. Goethe was inspired by Persian literature, which moved him to write his ''West–östlicher Divan, West-Eastern Divan''. Goethe wrote:

Ferdowsi concludes the ''Shahnameh'' by writing:

Another translation of by Reza Jamshidi Safa:

This prediction of Ferdowsi has come true and many Persian literary figures, historians and biographers have praised him and the ''Shahnameh''. The ''Shahnameh'' is considered by many to be the most important piece of work in Persian literature.

Western writers have also praised the ''Shahnameh'' and Persian literature in general. Persian literature has been considered by such thinkers as Goethe as one of the four main bodies of world literature. Goethe was inspired by Persian literature, which moved him to write his ''West–östlicher Divan, West-Eastern Divan''. Goethe wrote:

' s impact on Persian historiography was immediate and some historians decorated their books with the verses of Shahnameh. Below is sample of ten important historians who have praised the ''Shahnameh'' and Ferdowsi:

# The unknown writer of the ''Tarikh Sistan'' ("History of Sistan") written around 1053

# The unknown writer of ''Majmal al-tawarikh, Majmal al-Tawarikh wa Al-Qasas'' (c. 1126)

# Mohammad Ali Ravandi, the writer of the ''Rahat al-Sodur wa Ayat al-Sorur'' (c. 1206)

# Ibn Bibi, the writer of the history book, ''Al-Awamir al-'Alaiyah'', written during the era of Kayqubad I, 'Ala ad-din KayGhobad

# Ibn Esfandyar, the writer of the ''Tarikh-e Tabarestan''

# Ata al-Mulk Juvayni, Muhammad Juwayni, the early historian of the Mongol era in the ''Tarikh-e Jahan Gushay'' (Ilkhanid era)

# Hamdollah Mostowfi, Hamdollah Mostowfi Qazwini also paid much attention to the ''Shahnameh'' and wrote the ''Zafarnamah (Mustawfi), Zafarnamah'' based on the same style in the Ilkhanid era

# Hafiz-i Abru, Hafez-e Abru (1430) in the ''Majma' al-Tawarikh''

# Muhammad Khwandamir, Khwand Mir in the ''Habib al-Siyar, Habab al-Siyar'' (c. 1523) praised Ferdowsi and gave an extensive biography on Ferdowsi

# The Arab historian Ibn Athir remarks in his book, ''The Complete History, Al-Kamil'', that, "If we name it the Quran of 'Ajam, we have not said something in vain. If a poet writes poetry and the poems have many verses, or if someone writes many compositions, it will always be the case that some of their writings might not be excellent. But in the case of Shahnameh, despite having more than 40 thousand couplets, all its verses are excellent."

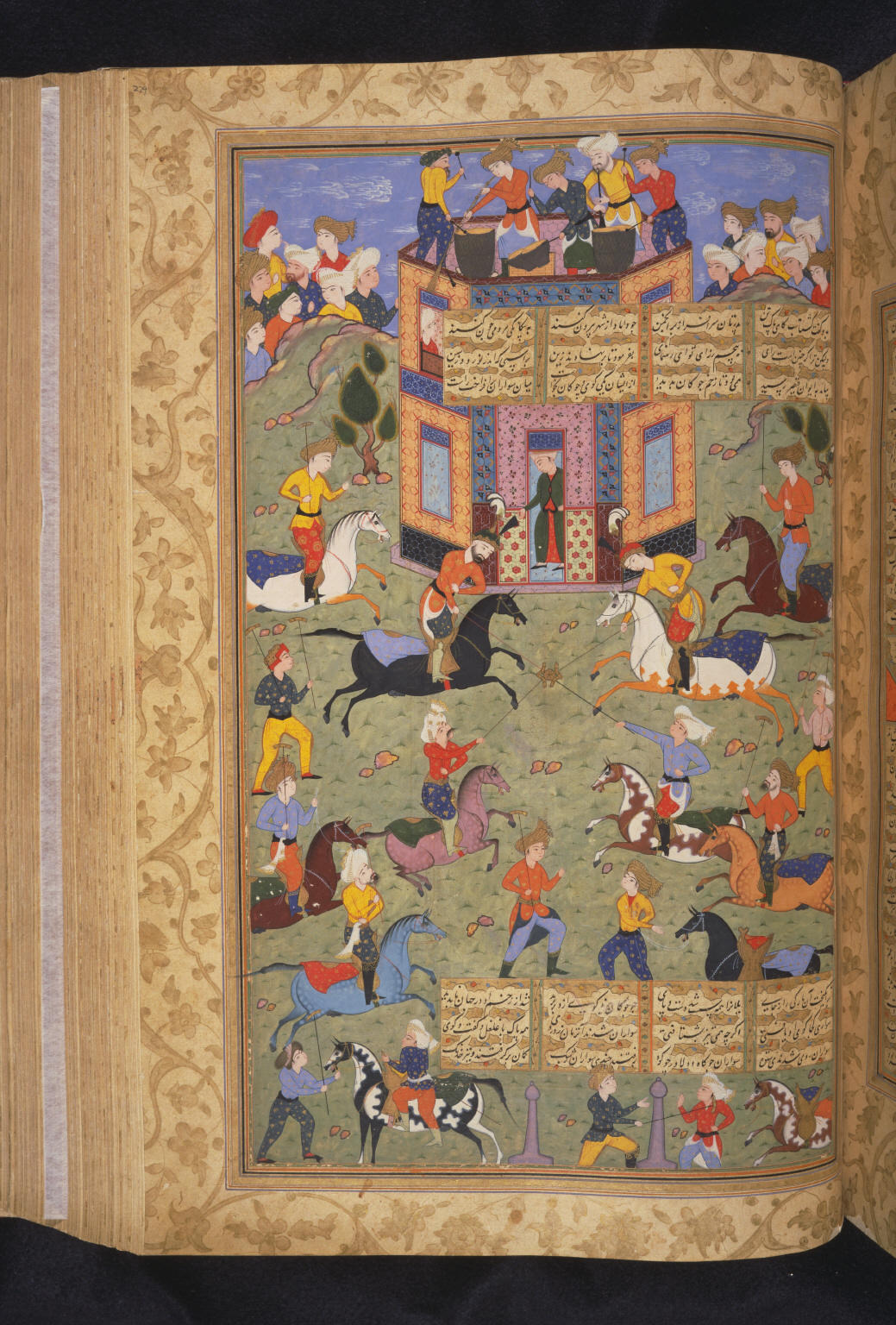

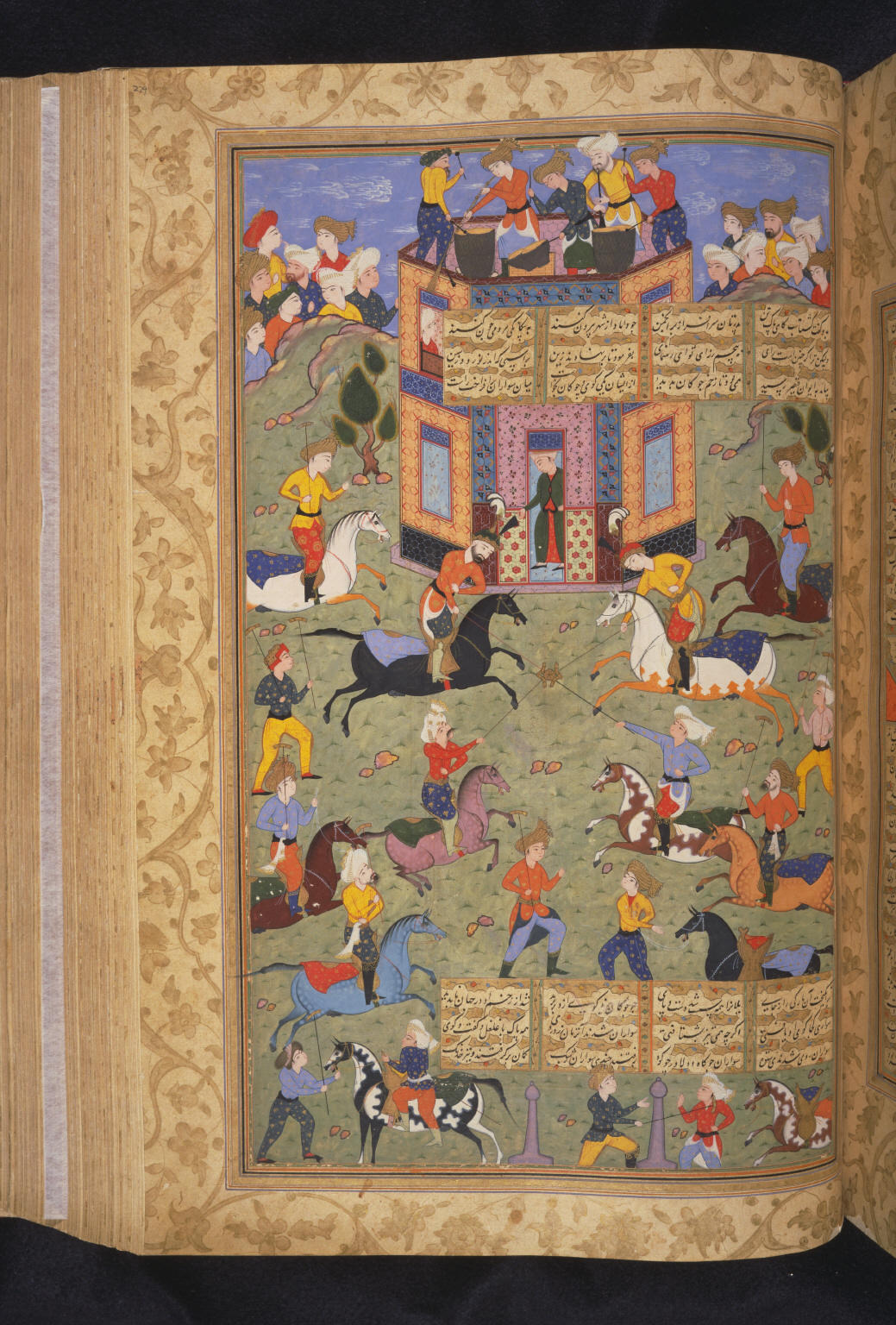

Illustrated copies of the work are among the most sumptuous examples of Persian miniature painting. Several copies remain intact, although two of the most famous, the Houghton Shahnameh, Houghton ''Shahnameh'' and the Great Mongol Shahnameh, Great Mongol ''Shahnameh'', were broken up for sheets to be sold separately in the 20th century. A single sheet from the former was sold for £904,000 in 2006. The Baysonghori Shahnameh, Baysonghori ''Shahnameh'', an illuminated manuscript copy of the work (Golestan Palace, Iran), is included in UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme, Memory of the World Register of cultural heritage items.

The Mongol rulers in Iran revived and spurred the patronage of the ''Shahnameh'' in its manuscript form. The "Great Mongol" or Demotte Shahnameh, Demotte ''Shahnameh'', produced during the reign of the Ilkhanid Sultan Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, Abu Sa'id, is one of the most illustrative and important copies of the ''Shahnameh''.

The Timurids continued the tradition of manuscript production. For them, it was considered ''de rigueur'' for the members of the family to have personal copies of the epic poem. Consequently, three of Timur’s grandsons—Baysonqor, Bāysonḡor, Sultan Ibrahim (Timurid), Ebrāhim Solṭān, and Muhammad Juki, Moḥammad Juki—each commissioned such a volume. Among these, the Baysonghor Shahnameh commissioned by Baysonqor, Ḡīāṯ-al-Dīn Bāysonḡor is one of the most voluminous and artistic ''Shahnameh'' manuscripts.

The production of illustrated ''Shahnameh'' manuscripts in the 15th century remained vigorous during the Kara Koyunlu, Qarā-Qoyunlu or Black Sheep (1380–1468) and Aq Qoyunlu, Āq Qoyunlu or White Sheep (1378–1508) Turkman dynasties. Many of the extant illustrated copies, with more than seventy or more paintings, are attributable to Tabriz, Shiraz, and Baghdad beginning in about the 1450s–60s and continuing to the end of the century.

The Safavid era saw a resurgence of ''Shahnameh'' productions. Shah Ismail I used the epic for propaganda purposes: as a gesture of Persian patriotism, as a celebration of renewed Persian rule, and as a reassertion of Persian royal authority. The Safavids commissioned elaborate copies of the ''Shahnameh'' to support their legitimacy. Among the high points of ''Shahnameh'' illustrations was the series of 250 miniatures commissioned by Shah Ismail for his son's Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. Two similar cycles of illustration of the mid-17th century, the Shahnameh of Rashida, ''Shahnameh'' of Rashida and the Windsor Shahnameh, Windsor ''Shahnameh'', come from the last great period of the Persian miniature.

In honour of the ''Shahnameh''

Illustrated copies of the work are among the most sumptuous examples of Persian miniature painting. Several copies remain intact, although two of the most famous, the Houghton Shahnameh, Houghton ''Shahnameh'' and the Great Mongol Shahnameh, Great Mongol ''Shahnameh'', were broken up for sheets to be sold separately in the 20th century. A single sheet from the former was sold for £904,000 in 2006. The Baysonghori Shahnameh, Baysonghori ''Shahnameh'', an illuminated manuscript copy of the work (Golestan Palace, Iran), is included in UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme, Memory of the World Register of cultural heritage items.

The Mongol rulers in Iran revived and spurred the patronage of the ''Shahnameh'' in its manuscript form. The "Great Mongol" or Demotte Shahnameh, Demotte ''Shahnameh'', produced during the reign of the Ilkhanid Sultan Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, Abu Sa'id, is one of the most illustrative and important copies of the ''Shahnameh''.

The Timurids continued the tradition of manuscript production. For them, it was considered ''de rigueur'' for the members of the family to have personal copies of the epic poem. Consequently, three of Timur’s grandsons—Baysonqor, Bāysonḡor, Sultan Ibrahim (Timurid), Ebrāhim Solṭān, and Muhammad Juki, Moḥammad Juki—each commissioned such a volume. Among these, the Baysonghor Shahnameh commissioned by Baysonqor, Ḡīāṯ-al-Dīn Bāysonḡor is one of the most voluminous and artistic ''Shahnameh'' manuscripts.

The production of illustrated ''Shahnameh'' manuscripts in the 15th century remained vigorous during the Kara Koyunlu, Qarā-Qoyunlu or Black Sheep (1380–1468) and Aq Qoyunlu, Āq Qoyunlu or White Sheep (1378–1508) Turkman dynasties. Many of the extant illustrated copies, with more than seventy or more paintings, are attributable to Tabriz, Shiraz, and Baghdad beginning in about the 1450s–60s and continuing to the end of the century.

The Safavid era saw a resurgence of ''Shahnameh'' productions. Shah Ismail I used the epic for propaganda purposes: as a gesture of Persian patriotism, as a celebration of renewed Persian rule, and as a reassertion of Persian royal authority. The Safavids commissioned elaborate copies of the ''Shahnameh'' to support their legitimacy. Among the high points of ''Shahnameh'' illustrations was the series of 250 miniatures commissioned by Shah Ismail for his son's Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. Two similar cycles of illustration of the mid-17th century, the Shahnameh of Rashida, ''Shahnameh'' of Rashida and the Windsor Shahnameh, Windsor ''Shahnameh'', come from the last great period of the Persian miniature.

In honour of the ''Shahnameh''' s millennial anniversary, in 2010 the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge hosted a major exhibition, called "Epic of the Persian Kings: The Art of Ferdowsi’s ''Shahnameh''", which ran from September 2010 to January 2011. The Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC also hosted an exhibition of folios from the 14th through the 16th centuries, called "Shahnama: 1000 Years of the Persian Book of Kings", from October 2010 to April 2011.

In 2013 Hamid Rahmanian illustrated a new English translation of the ''Shahnameh'' (translated by Ahmad Sadri) creating new imagery from old manuscripts.

Eleanor Sims. 1992. ''The Illustrated Manuscripts of Firdausī's "shāhnāma" Commissioned by Princes of the House of Tīmūr'' Ars Orientalis 22. The Smithsonian Institution: 43–68.

Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University

Iraj Bashiri, ''Characters of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh'', Iran Chamber Society, 2003

* Encyclopædia Iranica entry o

''Baysonghori Shahnameh''

Pages from the ''Illustrated Manuscript of the Shahnama''

at the Brooklyn Museum

Folios from the Great Mongol ''Shahnama''

at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The ''Shahnameh'' Project

Cambridge University (includes large database of miniatures)

Ancient Iran’s Geographical Position in Shah-Nameh

A richly illuminated and almost complete copy of the ''Shahnamah''

in Cambridge Digital Library

Resources about ''Shahnama''

at the University of Michigan Museum of Art ; English translations by: * Helen Zimmern, 1883

''Iran Chamber Society''

* Arthur and Edmond Warner, 1905–1925, (in nine volumes) at the Internet Archive

123456789

''A king's book of kings: the Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp''

an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

Firdowsi & the Shahname , Kaveh Farrokh

Text of the ''Shahnameh'' in Persian, section by section

{{Authority control Shahnameh, 1010 works 1010s books 11th-century poems Epic poems in Persian Ferdowsi Iranian books Persian mythology Persian poems Persian words and phrases 10th-century books 11th-century books Ghaznavid Empire Samanid Empire Historical poems Alexander Romance Filicide in fiction Memory of the World Register in Iran 10th century in Iran 11th century in Iran Poems adapted into films Mathnawi

The ''Shahnameh'' or ''Shahnama'' ( fa, شاهنامه, Šāhnāme, lit=The Book of Kings, ) is a long epic poem written by the Persian literature, Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 "distichs" or couplets (two-line verses), the ''Shahnameh'' is one of the world's longest epic poems. It tells mainly the Persian mythology, mythical and to some extent the historical past of the Persian Empire from the creation of the world until the Muslim conquest of Persia, Muslim conquest in the seventh century. Iran, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and the greater Greater Iran, region influenced by Persian culture such as Armenia, Dagestan, Georgia (country), Georgia, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan celebrate this national epic.

The work is of central importance in Persian culture and Persian language, regarded as a literary masterpiece, and definitive of the ethno-national cultural identity of Iran. It is also important to the contemporary adherents of Zoroastrianism, in that it traces the historical links between the beginnings of the religion and the death of the Fall of the Sasanian Empire, last Sasanian emperor, which brought an end to the Zoroastrian influence in Iran.

The ''Shahnameh'' or ''Shahnama'' ( fa, شاهنامه, Šāhnāme, lit=The Book of Kings, ) is a long epic poem written by the Persian literature, Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,000 "distichs" or couplets (two-line verses), the ''Shahnameh'' is one of the world's longest epic poems. It tells mainly the Persian mythology, mythical and to some extent the historical past of the Persian Empire from the creation of the world until the Muslim conquest of Persia, Muslim conquest in the seventh century. Iran, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and the greater Greater Iran, region influenced by Persian culture such as Armenia, Dagestan, Georgia (country), Georgia, Turkey, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan celebrate this national epic.

The work is of central importance in Persian culture and Persian language, regarded as a literary masterpiece, and definitive of the ethno-national cultural identity of Iran. It is also important to the contemporary adherents of Zoroastrianism, in that it traces the historical links between the beginnings of the religion and the death of the Fall of the Sasanian Empire, last Sasanian emperor, which brought an end to the Zoroastrian influence in Iran.

Composition

Ferdowsi started writing the ''Shahnameh'' in 977 and completed it on 8 March 1010. The ''Shahnameh'' is a monument of poetry and historiography, being mainly the poetical recast of what Ferdowsi, his contemporaries, and his predecessors regarded as the account of Iran's ancient history. Many such accounts already existed in prose, an example being the Abu-Mansuri Shahnameh. A small portion of Ferdowsi's work, in passages scattered throughout the ''Shahnameh'', is entirely of his own conception. The ''Shahnameh'' is an epic poem of over 50,000 couplets written in Persian language#Early New Persian, Early New Persian. It is based mainly on a prose work of the same name compiled in Ferdowsi's earlier life in his native Tus, Iran, Tus. This prose ''Shahnameh'' was in turn and for the most part the translation of a Pahlavi (Middle Persian) work, known as the ''Khwaday-Namag, Xwadāynāmag'' "Book of Kings", a late Sasanian compilation of the history of the kings and heroes of Persia from mythical times down to the reign of Khosrau II (590–628). The ''Xwadāynāmag'' contained historical information on the later Sasanian period, but it does not appear to have drawn on any historical sources for the earlier Sasanian period (3rd to 4th centuries). Ferdowsi added material continuing the story to the overthrow of the Sasanians by the Muslim armies in the middle of the seventh century. The first to undertake the versification of the Pahlavi chronicle was Daqiqi, a contemporary of Ferdowsi, poet at the court of the Samanid Empire, who came to a violent end after completing only 1,000 verses. These verses, which deal with the rise of the prophet Zoroaster, were afterward incorporated by Ferdowsi, with acknowledgment, in his own poem. The style of the ''Shahnameh'' shows characteristics of both written and oral literature. Some claim that Ferdowsi also used Zoroastrian ''nasks'', such as the now-lost ''Chihrdad,'' as sources as well. Many other Pahlavi scripts, Pahlavi sources were used in composing the epic, prominent being the ''Kārnāmag-ī Ardaxšīr-ī Pābagān'', which was originally written during the late Sassanid era and gave accounts of how Ardashir I came to power which, because of its historical proximity, is thought to be highly accurate. The text is written in the late Middle Persian, which was the immediate ancestor of Persian language, Modern Persian. A great portion of the historical chronicles given in ''Shahnameh'' is based on this epic and there are in fact various phrases and words which can be matched between Ferdowsi's poem and this source, according to Zabihollah Safa.Content

Traditional historiography in Iran has claimed that Ferdowsi was grieved by the fall of the Sassanid Empire and its subsequent rule by "Arabs" and "Turks". The ''Shahnameh'', the argument goes, is largely his effort to preserve the memory of Persia's golden days and transmit it to a new generation so that they could learn and try to build a better world. Although most scholars have contended that Ferdowsi's main concern was the preservation of the pre-Islamic legacy of myth and history, a number of authors have formally challenged this view.Mythical age

This portion of the ''Shahnameh'' is relatively short, amounting to some 2100 verses or four percent of the entire book, and it narrates events with the simplicity, predictability, and swiftness of a historical work.

After an opening in praise of God and Wisdom, the ''Shahnameh'' gives an account of the creation of the world and of man as believed by the Sassanians. This introduction is followed by the story of the first man, Keyumars, who also became the first king after a period of mountain-dwelling. His grandson Hushang, son of Siamak, Sīyāmak, accidentally discovered fire and established the Sadeh Feast in its honor. Stories of Tahmuras, Jamshid, Zahhak, Zahhāk, Kaveh the blacksmith, Kawa or Kaveh the blacksmith, Kaveh, Fereydun, Fereydūn and his three sons Salm (son of Fereydun), Salm, Tur (son of Fereydun), Tur, and Iraj, and his grandson Manuchehr are related in this section.

This portion of the ''Shahnameh'' is relatively short, amounting to some 2100 verses or four percent of the entire book, and it narrates events with the simplicity, predictability, and swiftness of a historical work.

After an opening in praise of God and Wisdom, the ''Shahnameh'' gives an account of the creation of the world and of man as believed by the Sassanians. This introduction is followed by the story of the first man, Keyumars, who also became the first king after a period of mountain-dwelling. His grandson Hushang, son of Siamak, Sīyāmak, accidentally discovered fire and established the Sadeh Feast in its honor. Stories of Tahmuras, Jamshid, Zahhak, Zahhāk, Kaveh the blacksmith, Kawa or Kaveh the blacksmith, Kaveh, Fereydun, Fereydūn and his three sons Salm (son of Fereydun), Salm, Tur (son of Fereydun), Tur, and Iraj, and his grandson Manuchehr are related in this section.

Heroic age

Almost two-thirds of the ''Shahnameh'' is devoted to the age of heroes, extending from Manuchehr's reign until the conquest of Alexander the Great. This age is also identified as the kingdom of Keyaniyan, which established a long history of heroic age in which myth and legend are combined. The main feature of this period is the major role played by the Saka or Sistan, Sistānī heroes who appear as the backbone of the Empire. Garshasp, Garshāsp is briefly mentioned with his son Nariman (father of Sām), Narimān, whose own son Saam, Sām acted as the leading paladin of Manuchehr while reigning in Sistān in his own right. His successors were his son Zal, Zāl and Zal's son Rostam, the bravest of the brave, and then Farāmarz. Among the stories described in this section are the romance of Zal and Rudaba, Rudāba, the Seven Stages (or Labors) of Rostam, Rostam and Sohrab, Siyavash, Sīyāvash and Sudabeh, Sudāba, Rostam and Akvān Dīv, the romance of Bijan and Manijeh, the wars with Afrasiab, Afrāsīyāb, Daqiqi's account of the story of Goshtāsp and Arjāsp, and Rostam and Esfandyar, Esfandyār.Historical age

A brief mention of the Parthian Empire, Arsacid dynasty follows the history of Alexander and precedes that of Ardashir I, founder of the Sasanian Empire. After this, Sasanian history is related with a good deal of accuracy. The fall of the Sassanids and the Arab conquest of Persia are narrated romantically.Message

According to Jalal Khaleghi Mutlaq, the ''Shahnameh'' teaches a wide variety of moral virtues, like worship of one God; religious uprightness; patriotism; love of wife, family and children; and helping the poor. There are themes in the Shahnameh that were viewed with suspicion by the succession of Iranian regimes. During the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah, the epic was largely ignored in favor of the more obtuse, esoteric and dryly intellectual Persian literature. Historians note that the theme of regicide and the incompetence of kings embedded in the epic did not sit well with the Iranian monarchy. Later, there were Muslim figures such as Ali Shariati, the hero of Islamic reformist youth of the 1970s, who were also antagonistic towards the contents of the Shahnameh since it included verses critical of Islam. These include the line: ''tofu bar to, ey charkh-i gardun, tofu!'' (spit on your face, oh heavens spit!), which Ferdowsi used as a reference to the Muslim invaders who despoiled Zoroastrianism.Influence on Persian language

After the ''Shahnameh'', a number of other works similar in nature surfaced over the centuries within the cultural sphere of the Persian language. Without exception, all such works were based in style and method on the ''Shahnameh'', but none of them could quite achieve the same degree of fame and popularity. Some experts believe the main reason the Persian language, Modern Persian language today is more or less the same language as that of Ferdowsi's time over 1000 years ago is due to the very existence of works like the ''Shahnameh'', which have had lasting and profound cultural and linguistic influence. In other words, the ''Shahnameh'' itself has become one of the main pillars of the modern Persian language. Studying Ferdowsi's masterpiece also became a requirement for achieving mastery of the Persian language by subsequent Persian poets, as evidenced by numerous references to the ''Shahnameh'' in their works. Although 19th century British Iranologist E. G. Browne has claimed that Ferdowsi purposefully avoided Arabic vocabulary, this claim has been challenged by modern scholarship, specifically Mohammed Moinfar, who has noted that there are numerous examples of Arabic words in the ''Shahnameh'' which are effectively synonyms for Persian words previously used in the text. This calls into question the idea of Ferdowsi's deliberate eschewing of Arabic words. The ''Shahnameh'' has 62 stories, 990 chapters, and some 50,000 rhyming couplets, making it more than three times the length of Homer's ''Iliad'', and more than twelve times the length of the German ''Nibelungenlied''. According to Ferdowsi himself, the final edition of the ''Shahnameh'' contained some sixty thousand distichs. But this is a round figure; most of the relatively reliable manuscripts have preserved a little over fifty thousand distichs. Nizami Arudhi Samarqandi, Nezami-e Aruzi reports that the final edition of the ''Shahnameh'' sent to the court of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni was prepared in seven volumes.Cultural influence

The Shirvanshah dynasty adopted many of their names from the ''Shahnameh''. The relationship between Shirwanshah and his son, Manuchihr, is mentioned in chapter eight of Nizami Ganjavi, Nizami's ''Layla and Majnun, Leili o Majnoon''. Nizami advises the king's son to read the ''Shahnameh'' and to remember the meaningful sayings of the wise.

According to the Turkish historian Mehmet Fuat Köprülü:

Shah Ismail I (d.1524), the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, was also deeply influenced by the Persian literature, Persian literary tradition, particularly by the ''Shahnameh'', which probably explains the fact that he named all of his sons after ''Shahnameh'' characters. Dickson and Welch suggest that Ismail's ''Shāhnāmaye Shāhī'' was intended as a present to the young Tahmasp I, Tahmāsp. After defeating Muhammad Shaybani, Muhammad Shaybāni's Uzbeks, Ismāil asked Hatefi (poet), Hātefī, a famous poet from Ghor Province, Jam (Khorasan), to write a ''Shahnameh''-like epic about his victories and his newly established dynasty. Although the epic was left unfinished, it was an example of ''mathnawis'' in the heroic style of the ''Shahnameh'' written later on for the Safavid kings.

The ''Shahnameh''

The Shirvanshah dynasty adopted many of their names from the ''Shahnameh''. The relationship between Shirwanshah and his son, Manuchihr, is mentioned in chapter eight of Nizami Ganjavi, Nizami's ''Layla and Majnun, Leili o Majnoon''. Nizami advises the king's son to read the ''Shahnameh'' and to remember the meaningful sayings of the wise.

According to the Turkish historian Mehmet Fuat Köprülü:

Shah Ismail I (d.1524), the founder of the Safavid dynasty of Iran, was also deeply influenced by the Persian literature, Persian literary tradition, particularly by the ''Shahnameh'', which probably explains the fact that he named all of his sons after ''Shahnameh'' characters. Dickson and Welch suggest that Ismail's ''Shāhnāmaye Shāhī'' was intended as a present to the young Tahmasp I, Tahmāsp. After defeating Muhammad Shaybani, Muhammad Shaybāni's Uzbeks, Ismāil asked Hatefi (poet), Hātefī, a famous poet from Ghor Province, Jam (Khorasan), to write a ''Shahnameh''-like epic about his victories and his newly established dynasty. Although the epic was left unfinished, it was an example of ''mathnawis'' in the heroic style of the ''Shahnameh'' written later on for the Safavid kings.

The ''Shahnameh''On Georgian identity

Jamshid Giunashvili, Jamshid Sh. Giunashvili remarks on the connection of Georgian culture with that of ''Shahnameh'':

Farmanfarmaian in the ''Journal of Persianate Studies'':

Jamshid Giunashvili, Jamshid Sh. Giunashvili remarks on the connection of Georgian culture with that of ''Shahnameh'':

Farmanfarmaian in the ''Journal of Persianate Studies'':

On Turkic identity

Despite a belief held by some, the Turanians of ''Shahnameh'' (whose sources are based on Avesta and Pahlavi scripts, Pahlavi texts) have no relationship with Turkic peoples, Turks. The Turanians of ''Shahnameh'' are an Iranian peoples, Iranian people representing Iranian nomads of the Eurasian Steppes and have no relationship to the culture of the Turks.Bosworth, C.E.Barbarian Incursions: The Coming of the Turks into the Islamic World

. In ''Islamic Civilization'', ed. D.S. Richards. Oxford, 1973. p. 2. "Firdawsi's Turan are, of course, really Indo-European nomads of Eurasian Steppes... Hence as Kowalski has pointed out, a Turkologist seeking for information in the Shahnama on the primitive culture of the Turks would definitely be disappointed. " Turan, which is the Persian name for the areas of Central Asia beyond the Oxus up to the 7th century (where the story of the ''Shahnameh'' ends), was generally an Iranian-speaking land. According to Richard Frye, "The extent of influence of the Iranian epic is shown by the Turks who accepted it as their own ancient history as well as that of Iran... The Turks were so much influenced by this cycle of stories that in the eleventh century AD we find the Qarakhanid dynasty in Central Asia calling itself the 'family of Afrasiyab' and so it is known in the Islamic history." Turks, as an ethno-linguistic group, have been influenced by the ''Shahnameh'' since advent of Saljuqs. Toghrul III of Seljuqs is said to have recited the ''Shahnameh'' while swinging his mace in battle. According to Ibn Bibi, in 618/1221 the Saljuq of Kayqubad I, Rum Ala' al-Din Kay-kubad decorated the walls of Konya and Sivas with verses from the ''Shahnameh''. The Turks themselves connected their origin not with Turkish tribal history but with the Turan of ''Shahnameh''.Schimmel, Annemarie. "Turk and Hindu: A Poetical Image and Its Application to Historical Fact". In ''Islam and Cultural Change in the Middle Ages'', ed. Speros Vryonis, Jr. Undena Publications, 1975. pp. 107–26. "In fact as much as early rulers felt themselves to be Turks, they connected their Turkish origin not with Turkish tribal history but rather with the Turan of Shahnameh: in the second generation their children bear the name of Firdosi’s heroes, and their Turkish lineage is invariably traced back to Afrasiyab—whether we read Barani in the fourteenth century or the Urdu master poet Ghalib in the nineteenth century. The poets, and through them probably most of the educated class, felt themselves to be the last outpost tied to the civilized world by the thread of Iranianism. The imagery of poetry remained exclusively Persian. " Specifically in India, through the ''Shahnameh'', they felt themselves to be the last outpost tied to the civilized world by the thread of Iranianism.

Legacy

Ferdowsi concludes the ''Shahnameh'' by writing:

Another translation of by Reza Jamshidi Safa:

This prediction of Ferdowsi has come true and many Persian literary figures, historians and biographers have praised him and the ''Shahnameh''. The ''Shahnameh'' is considered by many to be the most important piece of work in Persian literature.

Western writers have also praised the ''Shahnameh'' and Persian literature in general. Persian literature has been considered by such thinkers as Goethe as one of the four main bodies of world literature. Goethe was inspired by Persian literature, which moved him to write his ''West–östlicher Divan, West-Eastern Divan''. Goethe wrote:

Ferdowsi concludes the ''Shahnameh'' by writing:

Another translation of by Reza Jamshidi Safa:

This prediction of Ferdowsi has come true and many Persian literary figures, historians and biographers have praised him and the ''Shahnameh''. The ''Shahnameh'' is considered by many to be the most important piece of work in Persian literature.

Western writers have also praised the ''Shahnameh'' and Persian literature in general. Persian literature has been considered by such thinkers as Goethe as one of the four main bodies of world literature. Goethe was inspired by Persian literature, which moved him to write his ''West–östlicher Divan, West-Eastern Divan''. Goethe wrote:

Biographies

''Sargozasht-Nameh'' or biography of important poets and writers has long been a Persian tradition. Some of the biographies of Ferdowsi are now considered apocryphal, nevertheless this shows the important impact he had in the Persian world. Among the famous biographies are: # ''Chahar Maqaleh'' ("Four Articles") by Nizami Aruzi, Nezami 'Arudi-i Samarqandi # ''Tazkeret Al-Shu'ara'' ("The Biography of poets") by Dowlat Shah-i Samarqandi # ''Baharestan'' ("Abode of Spring") by Jami # ''Lubab ul-Albab'' by Muhammad Aufi, Mohammad 'Awfi # ''Natayej al-Afkar'' by Mowlana Muhammad Qudrat Allah # ''Arafat Al-'Ashighin'' by Taqqi Al-Din 'Awhadi BalyaniPoets

Famous poets of Persia and the Persian tradition have praised and eulogized Ferdowsi. Many of them were heavily influenced by his writing and used his genre and stories to develop their own Persian epics, stories and poems: * Anvari remarked about the eloquence of the ''Shahnameh'', "He was not just a Teacher and we his students. He was like a God and we are his slaves". * Asadi Tusi was born in the same city as Ferdowsi. His ''Garshaspnama'' was inspired by the ''Shahnameh'' as he attests in the introduction. He praises Ferdowsi in the introduction and considers Ferdowsi the greatest poet of his time. * Masud Sa'd Salman, Masud Sa'ad Salman showed the influence of the ''Shahnameh'' only 80 years after its composition by reciting its poems in the Ghaznavids, Ghaznavid court of India. * Uthman Mukhetari, Othman Mokhtari, another poet at the Ghaznavid court of India, remarked, "Alive is Rustam through the epic of Ferdowsi, else there would not be a trace of him in this World". * Sanai believed that the foundation of poetry was really established by Ferdowsi. * Nizami Ganjavi was influenced greatly by Ferdowsi and three of his five "treasures" had to do with pre-Islamic Persia. His ''Khosro-o-Shirin'', ''The Seven Beauties (poem), Haft Peykar'' and ''Eskandar-nameh'' used the ''Shahnameh'' as a major source. Nizami remarks that Ferdowsi is "the wise sage of Tus" who beautified and decorated words like a new bride. * Khaghani, the court poet of the Shirvanshah, wrote of Ferdowsi: * Attar of Nishapur, Attar wrote about the poetry of Ferdowsi: "Open eyes and through the sweet poetry see the heavenly eden of Ferdowsi." * In a famous poem, Saadi (poet), Sa'adi wrote: * In the ''Baharestan'', Jami wrote, "He came from Tus and his excellence, renown and perfection are well known. Yes, what need is there of the panegyrics of others to that man who has composed verses as those of the Shah-nameh?" Many other poets, e.g. Hafez, Rumi and other mystical poets, have used imageries of ''Shahnameh'' heroes in their poetry.Persian historiography

The ''Shahnameh''Illustrated copies

Illustrated copies of the work are among the most sumptuous examples of Persian miniature painting. Several copies remain intact, although two of the most famous, the Houghton Shahnameh, Houghton ''Shahnameh'' and the Great Mongol Shahnameh, Great Mongol ''Shahnameh'', were broken up for sheets to be sold separately in the 20th century. A single sheet from the former was sold for £904,000 in 2006. The Baysonghori Shahnameh, Baysonghori ''Shahnameh'', an illuminated manuscript copy of the work (Golestan Palace, Iran), is included in UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme, Memory of the World Register of cultural heritage items.

The Mongol rulers in Iran revived and spurred the patronage of the ''Shahnameh'' in its manuscript form. The "Great Mongol" or Demotte Shahnameh, Demotte ''Shahnameh'', produced during the reign of the Ilkhanid Sultan Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, Abu Sa'id, is one of the most illustrative and important copies of the ''Shahnameh''.

The Timurids continued the tradition of manuscript production. For them, it was considered ''de rigueur'' for the members of the family to have personal copies of the epic poem. Consequently, three of Timur’s grandsons—Baysonqor, Bāysonḡor, Sultan Ibrahim (Timurid), Ebrāhim Solṭān, and Muhammad Juki, Moḥammad Juki—each commissioned such a volume. Among these, the Baysonghor Shahnameh commissioned by Baysonqor, Ḡīāṯ-al-Dīn Bāysonḡor is one of the most voluminous and artistic ''Shahnameh'' manuscripts.

The production of illustrated ''Shahnameh'' manuscripts in the 15th century remained vigorous during the Kara Koyunlu, Qarā-Qoyunlu or Black Sheep (1380–1468) and Aq Qoyunlu, Āq Qoyunlu or White Sheep (1378–1508) Turkman dynasties. Many of the extant illustrated copies, with more than seventy or more paintings, are attributable to Tabriz, Shiraz, and Baghdad beginning in about the 1450s–60s and continuing to the end of the century.

The Safavid era saw a resurgence of ''Shahnameh'' productions. Shah Ismail I used the epic for propaganda purposes: as a gesture of Persian patriotism, as a celebration of renewed Persian rule, and as a reassertion of Persian royal authority. The Safavids commissioned elaborate copies of the ''Shahnameh'' to support their legitimacy. Among the high points of ''Shahnameh'' illustrations was the series of 250 miniatures commissioned by Shah Ismail for his son's Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. Two similar cycles of illustration of the mid-17th century, the Shahnameh of Rashida, ''Shahnameh'' of Rashida and the Windsor Shahnameh, Windsor ''Shahnameh'', come from the last great period of the Persian miniature.

In honour of the ''Shahnameh''

Illustrated copies of the work are among the most sumptuous examples of Persian miniature painting. Several copies remain intact, although two of the most famous, the Houghton Shahnameh, Houghton ''Shahnameh'' and the Great Mongol Shahnameh, Great Mongol ''Shahnameh'', were broken up for sheets to be sold separately in the 20th century. A single sheet from the former was sold for £904,000 in 2006. The Baysonghori Shahnameh, Baysonghori ''Shahnameh'', an illuminated manuscript copy of the work (Golestan Palace, Iran), is included in UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme, Memory of the World Register of cultural heritage items.

The Mongol rulers in Iran revived and spurred the patronage of the ''Shahnameh'' in its manuscript form. The "Great Mongol" or Demotte Shahnameh, Demotte ''Shahnameh'', produced during the reign of the Ilkhanid Sultan Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, Abu Sa'id, is one of the most illustrative and important copies of the ''Shahnameh''.

The Timurids continued the tradition of manuscript production. For them, it was considered ''de rigueur'' for the members of the family to have personal copies of the epic poem. Consequently, three of Timur’s grandsons—Baysonqor, Bāysonḡor, Sultan Ibrahim (Timurid), Ebrāhim Solṭān, and Muhammad Juki, Moḥammad Juki—each commissioned such a volume. Among these, the Baysonghor Shahnameh commissioned by Baysonqor, Ḡīāṯ-al-Dīn Bāysonḡor is one of the most voluminous and artistic ''Shahnameh'' manuscripts.

The production of illustrated ''Shahnameh'' manuscripts in the 15th century remained vigorous during the Kara Koyunlu, Qarā-Qoyunlu or Black Sheep (1380–1468) and Aq Qoyunlu, Āq Qoyunlu or White Sheep (1378–1508) Turkman dynasties. Many of the extant illustrated copies, with more than seventy or more paintings, are attributable to Tabriz, Shiraz, and Baghdad beginning in about the 1450s–60s and continuing to the end of the century.

The Safavid era saw a resurgence of ''Shahnameh'' productions. Shah Ismail I used the epic for propaganda purposes: as a gesture of Persian patriotism, as a celebration of renewed Persian rule, and as a reassertion of Persian royal authority. The Safavids commissioned elaborate copies of the ''Shahnameh'' to support their legitimacy. Among the high points of ''Shahnameh'' illustrations was the series of 250 miniatures commissioned by Shah Ismail for his son's Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp. Two similar cycles of illustration of the mid-17th century, the Shahnameh of Rashida, ''Shahnameh'' of Rashida and the Windsor Shahnameh, Windsor ''Shahnameh'', come from the last great period of the Persian miniature.

In honour of the ''Shahnameh''Modern editions

Scholarly editions

Scholarly editions have been prepared of the ''Shahnameh''. In 1808 Mathew Lumsden (1777–1835) undertook the work of an edition of the poem. The first of eight planned volumes was published in Kolkata in 1811. But Lumsden didn't finish any further volumes. In 1829 Turner Macan published the first complete edition of the poem. It was based on a comparison of 17 manuscript copies. Between 1838 and 1878, an edition appeared by French scholar Julius von Mohl, which was based on a comparison of 30 manuscripts. After Mohl's death in 1876, the last of its seven volumes was completed by Charles Barbier de Meynard, Mohl's successor to the chair of Persian of the College de France. Both editions lacked critical apparatuses and were based on secondary manuscripts dated after the 15th century; much later than the original work. Between 1877 and 1884, the German scholar Johann August Vullers prepared a synthesized text of the Macan and Mohl editions under the title ''Firdusii liber regum'', but only three of its expected nine volumes were published. The Vullers edition was later completed in Tehran by the Iranian scholars S. Nafisi, Iqbal, and M. Minowi for the millennial jubilee of Ferdowsi, held between 1934 and 1936. The first modern critical edition of the ''Shahnameh'' was prepared by a Russian team led by E. E. Bertels, using the oldest known manuscripts at the time, dating from the 13th and 14th centuries, with heavy reliance on the 1276 manuscript from the British Museum and the 1333 Leningrad manuscript, the latter of which has now been considered a secondary manuscript. In addition, two other manuscripts used in this edition have been so demoted. It was published in Moscow by the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR in nine volumes between 1960 and 1971. For many years, the Moscow edition was the standard text. In 1977, an early 1217 manuscript was rediscovered in Florence. The 1217 Florence manuscript is one of the earliest known copies of the ''Shahnameh'', predating the Moghul invasion and the following destruction of important libraries and manuscript collections. Using it as the chief text, Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh began the preparation of a new critical edition in 1990. The number of manuscripts that were consulted during the preparation of Khaleghi-Motlagh edition goes beyond anything attempted by the Moscow team. The critical apparatus is extensive and a large number of variants for many parts of the poem were recorded. The last volume was published in 2008, bringing the eight-volume enterprise to a completion. According to Dick Davis (translator), Dick Davis, professor of Persian at Ohio State University, it is "by far the best edition of the ''Shahnameh'' available, and it is surely likely to remain such for a very long time".Arabic translation

The only known Arabic translation of the ''Shahnameh'' was done in c. 1220 by Bondari Esfahani, al-Fath bin Ali al-Bondari, a Persian scholar from Isfahan and at the request of the Ayyubid ruler of Damascus Al-Mu'azzam Isa. The translation is ''Nathr'' (unrhyming) and was largely forgotten until it was republished in full in 1932 in Egypt, by historian Abdelwahhab Azzam. This modern edition was based on incomplete and largely imprecise fragmented copies found in University of Cambridge, Cambridge, Paris, Astana, Cairo and Berlin. The latter had the most complete, least inaccurate and well-preserved Arabic version of the original translation by al-Bondari.English translations

There have been a number of English translations, almost all abridged. James Atkinson (Persian scholar), James Atkinson of the East India Company's medical service undertook a translation into English in his 1832 publication for the Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland, now part of the Royal Asiatic Society. Between 1905 and 1925, the brothers Arthur and Edmond Warner published a translation of the complete work in nine volumes, now out of print. There are also modern incomplete translations of the ''Shahnameh'': Reuben Levy's 1967 prose version (later revised by Amin Banani), and another by Dick Davis in a mixture of poetry and prose which appeared in 2006. Also a new English translation of the book in prose by Ahmad Sadri was published in 2013. The Parsis, Zoroastrians, whose ancestors had migrated to India in the 8th or 10th century so they could continue practice of their religion in peace, have also kept the ''Shahnameh'' traditions alive. Dr. Bahman Sohrabji Surti, assisted by Marzban Giara, published between 1986 and 1988 the first detailed and complete translation of the ''Shahnameh'' from the original Persian verse into English prose, in seven volumes.Other languages

There are various translations in French and German. An Italian translation was published in eight volumes by Italo Pizzi with the title ''Il libro dei re.'' Poema epico recato dal persiano in versi italiani da Italo Pizzi, 8 voll., Torino, Vincenzo Bona, 1886–1888 (later reissued in two volumes with a compendium, from UTET, Turin, 1915). Dastur Faramroz Kutar and his brother Ervad Mahiyar Kutar translated the ''Shahnameh'' into Gujarati verse and prose and published 10 volumes between 1914 and 1918. A Spanish translation was published in two volumes by the Islamic Research Institute of the Tehran Branch of McGill University.In popular culture

The ''Shahnameh'', especially the legend of Rostam and Sohrab, is cited and plays an important role in the novel ''The Kite Runner'' by Afghan-American writer Khaled Hosseini. The ''Shahnameh'' has also been adapted to many films and animations: * Shirin Farhad (1931 film), ''Shirin Farhad'' (1931), Indian Hindi-language feature film based on the story of Khosrow and Shirin, directed by J.J. Madan and starring Jehanara Kajjan and Master Nissar. It was the second Indian sound film after ''Alam Ara'' (also released in the same year). *Shirin Farhad (1956 film), ''Shirin Farhad'' (1956), Indian Romance film, romantic adventure drama film based on the story of Khosrow and Shirin, directed by Aspi Irani and starring Madhubala and Pradeep Kumar. *''Rustom Sohrab (1963 film), Rustom Sohrab'' (1963), Indian adventure drama film based on the story of Rustam and Sohrab, directed by Vishram Bedekar and starring Prithviraj Kapoor and Prem Nath, Premnath. *In 1971–1976, Tajikfilm produced a trilogy comprising ''Skazanie o Rustame'', ''Rustam i Sukhrab'' and ''Skazanie o Sijavushe''. *''Zal & Simorgh'' (1977), Persian short animation directed by Ali Akbar Sadeghi, narrates the story of Zal from birth until returning to the human society. * ''Chehel Sarbaz'' (2007), Persian TV series directed by Mohammad Nourizad, concurrently tells the story of Rostam and Esfandiar, biography of Ferdowsi, and a few other historical events. * ''The Legend of Mardoush'' (2005), a long animated Persian trilogy, tells the mythical stories of ''Shahnameh'' from the kingdom of Jamshid to the victory of Fereydun over Zahhak. *''Shirin Farhad Ki Toh Nikal Padi'' (2012), Indian Hindi-language romantic comedy film about the love affair of a middle-aged Parsis, Parsi couple loosely based on the story of Khosrow and Shirin, directed by Bela Segal and starring Farah Khan and Boman Irani. * ''The Last Fiction'' (2017), a long animated movie, has an open interpretation of the story of Zahhak.See also

Notes

References

Sources

*Further reading

* Poet Moniruddin Yusuf (1919–1987) translated the full version of ''Shahnameh'' into the Bengali language (1963–1981). It was published by the National Organisation of Bangladesh Bangla Academy, in six volumes, in February 1991. * Borjian, Habib and Maryam Borjian. 2005–2006. The Story of Rostam and the White Demon in Māzandarāni. ''Nāme-ye Irān-e Bāstān'' 5/1-2 (ser. nos. 9 & 10), pp. 107–116. * Shirzad Aghaee, ''Imazh-ha-ye mehr va mah dar Shahnama-ye Ferdousi'' (Sun and Moon in the Shahnama of Ferdousi, Spånga, Sweden, 1997. () * Shirzad Aghaee, ''Nam-e kasan va ja'i-ha dar Shahnama-ye Ferdousi'' (Personalities and Places in the Shahnama of Ferdousi, Nyköping, Sweden, 1993. ()Eleanor Sims. 1992. ''The Illustrated Manuscripts of Firdausī's "shāhnāma" Commissioned by Princes of the House of Tīmūr'' Ars Orientalis 22. The Smithsonian Institution: 43–68.

Persian text

* A. E. Bertels (editor), ''Shāx-nāme: Kriticheskij Tekst'', nine volumes (Moscow: Izdatel'stvo Nauka, 1960–71) (scholarly Persian text) * Jalal Khāleghi Motlagh (editor), ''The Shahnameh'', in 12 volumes consisting of eight volumes of text and four volumes of explanatory notes. (Bibliotheca Persica, 1988–2009) (scholarly Persian text). SeeCenter for Iranian Studies, Columbia University

Adaptations

Modern English graphic novels: * , about the story of Rostam & Sohrab. * , about the story of Kai-Kavous and Soodabeh. * , the story of the evil White Deev. * , the story of Rostam's childhood.External links

Iraj Bashiri, ''Characters of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh'', Iran Chamber Society, 2003

* Encyclopædia Iranica entry o

''Baysonghori Shahnameh''

Pages from the ''Illustrated Manuscript of the Shahnama''

at the Brooklyn Museum

Folios from the Great Mongol ''Shahnama''

at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The ''Shahnameh'' Project

Cambridge University (includes large database of miniatures)

Ancient Iran’s Geographical Position in Shah-Nameh

A richly illuminated and almost complete copy of the ''Shahnamah''

in Cambridge Digital Library

Resources about ''Shahnama''

at the University of Michigan Museum of Art ; English translations by: * Helen Zimmern, 1883

''Iran Chamber Society''

* Arthur and Edmond Warner, 1905–1925, (in nine volumes) at the Internet Archive

1

''A king's book of kings: the Shah-nameh of Shah Tahmasp''

an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)

Firdowsi & the Shahname , Kaveh Farrokh

Text of the ''Shahnameh'' in Persian, section by section

{{Authority control Shahnameh, 1010 works 1010s books 11th-century poems Epic poems in Persian Ferdowsi Iranian books Persian mythology Persian poems Persian words and phrases 10th-century books 11th-century books Ghaznavid Empire Samanid Empire Historical poems Alexander Romance Filicide in fiction Memory of the World Register in Iran 10th century in Iran 11th century in Iran Poems adapted into films Mathnawi