Sergeant York on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alvin Cullum York (December 13, 1887 – September 2, 1964), also known as Sergeant York, was one of the most decorated

by Dr. Michael Birdwell. He was the third child born to William Uriah York and Mary Elizabeth (Brooks) York. William Uriah York was born in

Gladys Williams, "Alvin C. York"

accessed September 20, 2010 The York family is mainly of

at ancestry.com The family resided in the Indian Creek area of Fentress County. The family was impoverished, with William York working as a

Despite his history of drinking and fighting, York attended church regularly and often led the hymn singing. A

Despite his history of drinking and fighting, York attended church regularly and often led the hymn singing. A

In an October 8, 1918, attack that occurred during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, York's battalion aimed to capture German positions near Hill 223 () along the

In an October 8, 1918, attack that occurred during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, York's battalion aimed to capture German positions near Hill 223 () along the  During the assault, a German officer led several Germans to the scene of the fighting and ran into York who shot several of them with his pistol.

Imperial German Army First Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer, commanding the 120th Reserve Infantry Regiment's 1st Battalion, emptied his pistol trying to kill York while he was contending with the machine guns. Failing to injure York, and seeing his mounting losses, he offered in English to surrender the unit to York who accepted. At the end of the engagement, York and his seven men marched their German prisoners back to the American lines. Upon returning to his unit, York reported to his brigade commander, Brigadier General Julian Robert Lindsey, who remarked: "Well York, I hear you have captured the whole German army." York replied: "No sir. I got only 132."

York's actions silenced the German machine guns and were responsible for enabling the 328th Infantry to renew its attack to capture the Decauville Railroad.Mastriano, Douglas, Colonel, U.S. Army ''Brave Hearts under Red Skies''and Douglas Mastriano

During the assault, a German officer led several Germans to the scene of the fighting and ran into York who shot several of them with his pistol.

Imperial German Army First Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer, commanding the 120th Reserve Infantry Regiment's 1st Battalion, emptied his pistol trying to kill York while he was contending with the machine guns. Failing to injure York, and seeing his mounting losses, he offered in English to surrender the unit to York who accepted. At the end of the engagement, York and his seven men marched their German prisoners back to the American lines. Upon returning to his unit, York reported to his brigade commander, Brigadier General Julian Robert Lindsey, who remarked: "Well York, I hear you have captured the whole German army." York replied: "No sir. I got only 132."

York's actions silenced the German machine guns and were responsible for enabling the 328th Infantry to renew its attack to capture the Decauville Railroad.Mastriano, Douglas, Colonel, U.S. Army ''Brave Hearts under Red Skies''and Douglas Mastriano

"A Day for Heroes"

, accessed September 21, 2010

York was promptly promoted to sergeant and received the

York was promptly promoted to sergeant and received the

Sergeant York, War Hero, Dies", September 3, 1964

accessed September 20, 2010 He eventually received nearly 50 decorations. York's Medal of Honor citation reads: In attempting to explain his actions during the 1919 investigation that resulted in the Medal of Honor, York told General Lindsey "A higher power than man guided and watched over me and told me what to do." Lindsey replied "York, you are right." Biographer David D. Lee (2000) wrote:

York's heroism went unnoticed in the United States press, even in Tennessee, until the publication of the April 26, 1919, issue of the '' Saturday Evening Post'', which had a circulation in excess of 2 million. In an article titled "The Second Elder Gives Battle", journalist George Pattullo, who had learned of York's story while touring battlefields earlier in the year, laid out the themes that have dominated York's story ever since: the mountaineer, his religious faith and skill with firearms, patriotic, plainspoken and unsophisticated, an uneducated man who "seems to do everything correctly by intuition." In response, the Tennessee Society, a group of Tennesseans living in

York's heroism went unnoticed in the United States press, even in Tennessee, until the publication of the April 26, 1919, issue of the '' Saturday Evening Post'', which had a circulation in excess of 2 million. In an article titled "The Second Elder Gives Battle", journalist George Pattullo, who had learned of York's story while touring battlefields earlier in the year, laid out the themes that have dominated York's story ever since: the mountaineer, his religious faith and skill with firearms, patriotic, plainspoken and unsophisticated, an uneducated man who "seems to do everything correctly by intuition." In response, the Tennessee Society, a group of Tennesseans living in

In 1935 York, sensing the end of his time with the institute, began to work as a project superintendent with the

In 1935 York, sensing the end of his time with the institute, began to work as a project superintendent with the

York cooperated with journalists in telling his life story twice in the 1920s. He allowed Nashville-born freelance journalist Sam Cowan to see his diary and submitted to interviews. The resulting 1922 biography focused on York's Appalachian background, describing his upbringing among the "purest Anglo-Saxons to be found today", emphasizing popular stereotypes without bringing the man to life. A few years later, York contacted a publisher about an edition of his war diary, but the publisher wanted additional material to flesh out the story. Then Tom Skeyhill, an Australian-born veteran of the Gallipoli campaign, visited York in Tennessee and the two became friends. On York's behalf, Skeyhill wrote an "autobiography" in the first person and was credited as the editor of ''Sergeant York: His Own Life Story and War Diary''. With a preface by Newton D. Baker, Secretary of War in World War I, it presented a one-dimensional York supplemented with tales of life in the Tennessee mountains. Reviews noted that York only promoted his life story in the interest of funding educational programs: "Perhaps York's bearing after his famous exploit in the Argonne best reveals his native greatness. ... He will not exploit himself except for his own people. All of which gives his book an appeal beyond its contents."

The mountaineer persona Cowan and Skeyhill promoted reflected York's own beliefs. In a speech at the 1939 New York World's Fair, he said:

For many years, York employed a secretary, Arthur S. Bushing, who wrote the lectures and speeches York delivered. Bushing prepared York's correspondence as well. Like the works of Cowan and Skeyhill, words commonly ascribed to York, though doubtless representing his thinking, were often composed by professional writers. York had refused several times to authorize a film version of his life story. Finally, in 1940, as York was looking to finance an interdenominational Bible school, he yielded to a persistent Hollywood producer and negotiated the contract himself. In 1941 the movie '' Sergeant York'', directed by Howard Hawks with

York cooperated with journalists in telling his life story twice in the 1920s. He allowed Nashville-born freelance journalist Sam Cowan to see his diary and submitted to interviews. The resulting 1922 biography focused on York's Appalachian background, describing his upbringing among the "purest Anglo-Saxons to be found today", emphasizing popular stereotypes without bringing the man to life. A few years later, York contacted a publisher about an edition of his war diary, but the publisher wanted additional material to flesh out the story. Then Tom Skeyhill, an Australian-born veteran of the Gallipoli campaign, visited York in Tennessee and the two became friends. On York's behalf, Skeyhill wrote an "autobiography" in the first person and was credited as the editor of ''Sergeant York: His Own Life Story and War Diary''. With a preface by Newton D. Baker, Secretary of War in World War I, it presented a one-dimensional York supplemented with tales of life in the Tennessee mountains. Reviews noted that York only promoted his life story in the interest of funding educational programs: "Perhaps York's bearing after his famous exploit in the Argonne best reveals his native greatness. ... He will not exploit himself except for his own people. All of which gives his book an appeal beyond its contents."

The mountaineer persona Cowan and Skeyhill promoted reflected York's own beliefs. In a speech at the 1939 New York World's Fair, he said:

For many years, York employed a secretary, Arthur S. Bushing, who wrote the lectures and speeches York delivered. Bushing prepared York's correspondence as well. Like the works of Cowan and Skeyhill, words commonly ascribed to York, though doubtless representing his thinking, were often composed by professional writers. York had refused several times to authorize a film version of his life story. Finally, in 1940, as York was looking to finance an interdenominational Bible school, he yielded to a persistent Hollywood producer and negotiated the contract himself. In 1941 the movie '' Sergeant York'', directed by Howard Hawks with

York and his wife Gracie had ten children, seven sons and three daughters, most named after American historical figures: Infant son (1920, died at 4 days), Alvin Cullum, Jr. (1921–1983), George Edward Buxton (1923–2018), Woodrow Wilson (1925–1998), Samuel Huston (1928–1929), Andrew Jackson (1930–2022), Betsy Ross (born 1933), Mary Alice (1935–1991), Thomas Jefferson (1938–1972), and Infant daughter (1940, died same day).

York had health problems throughout his life. He had gallbladder surgery in the late 1920s and had

York and his wife Gracie had ten children, seven sons and three daughters, most named after American historical figures: Infant son (1920, died at 4 days), Alvin Cullum, Jr. (1921–1983), George Edward Buxton (1923–2018), Woodrow Wilson (1925–1998), Samuel Huston (1928–1929), Andrew Jackson (1930–2022), Betsy Ross (born 1933), Mary Alice (1935–1991), Thomas Jefferson (1938–1972), and Infant daughter (1940, died same day).

York had health problems throughout his life. He had gallbladder surgery in the late 1920s and had

In October 2006, United States Army Colonel Douglas Mastriano, head of the Sergeant York Discovery Expedition (SYDE), conducted research to locate the York battle site. Among the Mastriano expedition's finds were 46 American rifle rounds. In addition, his research located pieces of German ammunition and weaponry. Without the official support of the French government, Mastriano excavated the site and bulldozed the area in order to build two monuments and a historic trail. Mastriano's research has been strongly disputed by other historians who point out numerous errors in the history dissertation and subsequent book that he published on York.

Another team led by Dr. Tom Nolan, head of the Sergeant York Project and a geographer at the R.O. Fullerton Laboratory for Spatial Technology at

In October 2006, United States Army Colonel Douglas Mastriano, head of the Sergeant York Discovery Expedition (SYDE), conducted research to locate the York battle site. Among the Mastriano expedition's finds were 46 American rifle rounds. In addition, his research located pieces of German ammunition and weaponry. Without the official support of the French government, Mastriano excavated the site and bulldozed the area in order to build two monuments and a historic trail. Mastriano's research has been strongly disputed by other historians who point out numerous errors in the history dissertation and subsequent book that he published on York.

Another team led by Dr. Tom Nolan, head of the Sergeant York Project and a geographer at the R.O. Fullerton Laboratory for Spatial Technology at

online

* * * * * *

online free

* * Skeyhill, Thomas. ''Sergeant York: Last of the Long Hunters'' (1930); * Yockelson, Mitchell. ''Forty-Seven Days: How Pershing's Warriors Came of Age to Defeat at the German Army in World War I''. New York: NAL, Caliber, 2016. . *

Alvin C. York Institute

Sgt. Alvin C. York State Historic Park

General information *

at Medal of Honor Recipients Portrayed On Film (lylefrancispadilla.com) *

Sergeant York Project

The Sergeant York Discovery Expedition (SYDE)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:York, Alvin C. 1887 births 1964 deaths United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army personnel of World War II American community activists American conscientious objectors American diarists American people of English descent American people of Scotch-Irish descent American Protestants Burials in Tennessee Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur Civilian Conservation Corps people Military personnel from Tennessee Organization founders People from Harriman, Tennessee People from Pall Mall, Tennessee Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Recipients of the War Merit Cross (Italy) Tennessee Democrats United States Army Medal of Honor recipients United States Army soldiers World War I recipients of the Medal of Honor American anti-communists

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

soldiers of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. He received the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

for leading an attack on a German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) ar ...

nest, gathering 35 machine guns, killing at least 25 enemy soldiers and capturing 132 prisoners. York's Medal of Honor action occurred during the United States-led portion of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, which was intended to breach the Hindenburg line

The Hindenburg Line (German: , Siegfried Position) was a German defensive position built during the winter of 1916–1917 on the Western Front during the First World War. The line ran from Arras to Laffaux, near Soissons on the Aisne. In 1916 ...

and force the Germans to surrender. He earned decorations from several allied countries during WWI, including France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

.

York was born in rural Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, in what is now the community of Pall Mall in Fentress County. His parents farmed, and his father worked as a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, gr ...

. The eleven York children had minimal schooling because they helped provide for the family, including hunting, fishing, and working as laborers. After the death of his father, York assisted in caring for his younger siblings and found work as a blacksmith. Despite being a regular churchgoer, York also drank heavily and was prone to fistfights. After a 1914 conversion experience, he vowed to improve and became even more devoted to the Church of Christ in Christian Union. York was drafted during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

; he initially claimed conscientious objector status on the grounds that his religious denomination forbade violence. Persuaded that his religion was not incompatible with military service, York joined the 82nd Division as an infantry private and went to France in 1918.

In October 1918, Private First Class (Acting Corporal) York was one of a group of seventeen soldiers assigned to infiltrate German lines and silence a machine gun position. After the American patrol had captured a large group of enemy soldiers, German small arms fire killed six Americans and wounded three. Several of the Americans returned fire while others guarded the prisoners. York and the other Americans attacked the machine gun position, killing several German soldiers. The German officer responsible for the machine gun position had emptied his pistol while firing at York but failed to hit him. This officer then offered to surrender and York accepted. York and his men marched back to their unit's command post with more than 130 prisoners. York was later promoted to sergeant and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

. An investigation resulted in the upgrading of the award to the Medal of Honor. York's feat made him a national hero and international celebrity among allied nations.

After Armistice Day

Armistice Day, later known as Remembrance Day in the Commonwealth and Veterans Day in the United States, is commemorated every year on 11 November to mark the armistice signed between the Allies of World War I and Germany at Compiègne, Fran ...

, a group of Tennessee businessmen purchased a farm for York, his new wife, and their growing family. He later formed a charitable foundation to improve educational opportunities for children in rural Tennessee. In the 1930s and 1940s, York worked as a project superintendent for the Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a major part of ...

and managed construction of the Byrd Lake reservoir at Cumberland Mountain State Park

Cumberland Mountain State Park is a state park in Cumberland County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The park consists of situated around Byrd Lake, a man-made lake created by the impoundment of Byrd Creek in the 1930s. The park ...

, after which he served for several years as park superintendent. A 1941 film about his World War I exploits, '' Sergeant York'', was that year's highest-grossing film; Gary Cooper

Gary Cooper (born Frank James Cooper; May 7, 1901May 13, 1961) was an American actor known for his strong, quiet screen persona and understated acting style. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice and had a further three nominations, ...

won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of York, and the film was credited with enhancing American morale as the US mobilized for action in World War II. In his later years, York was confined to bed by health problems. He died in Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and ...

, in 1964 and was buried at Wolf River Cemetery in his hometown of Pall Mall, Tennessee.

Early life

Alvin Cullum York was born in a two-room log cabin inFentress County, Tennessee

Fentress County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 18,489. Its county seat is Jamestown.

History

Fentress County was formed on November 28, 1823, from portions of Morgan, Overton a ...

.Legends and Traditions of the Great War: Sergeant Alvin Yorkby Dr. Michael Birdwell. He was the third child born to William Uriah York and Mary Elizabeth (Brooks) York. William Uriah York was born in

Jamestown, Tennessee

Jamestown is a city in, and the county seat of, Fentress County, Tennessee, United States. The population of the city was 1,959 at the 2010 census.

History

Jamestown was established in 1823 as a county seat for Fentress County. It was incorporate ...

, to Uriah York and Eliza Jane Livingston, who had moved to Tennessee from Buncombe County, North Carolina

Buncombe County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. It is classified within Western North Carolina. The 2020 census reported the population was 269,452. Its county seat is Asheville. Buncombe County is part of the Asheville ...

. Mary Elizabeth York was born in Pall Mall to William Brooks, who took his mother's maiden name as an alias of William H. Harrington after deserting from Company A of the 11th Michigan Cavalry Regiment during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, and Nancy Pyle, and was the great-granddaughter of Conrad "Coonrod" Pyle, an English settler who settled Pall Mall, Tennessee.

William York and Mary Brooks married on December 25, 1881, and had eleven children: Henry Singleton, Joseph Marion, Alvin Cullum, Samuel John, Albert, Hattie, George Alexander, James Preston, Lillian Mae, Robert Daniel, and Lucy Erma.Laughter & Lawter GenealogyGladys Williams, "Alvin C. York"

accessed September 20, 2010 The York family is mainly of

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

ancestry, with Scots-Irish ancestry as well.York Indian Heritageat ancestry.com The family resided in the Indian Creek area of Fentress County. The family was impoverished, with William York working as a

blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, gr ...

to supplement the family's income. The men of the York family farmed and harvested their own food, while the mother made all of the family's clothing. The York sons attended school for only nine months and withdrew from education because William York needed them to help work on the family farm, hunt, and fish to help feed the family. When William York died in November 1911, his son Alvin helped his mother raise his younger siblings. Alvin was the oldest sibling still residing in the county, since his two older brothers had married and relocated. To supplement the family's income, York worked in Harriman, Tennessee

Harriman is a city located primarily in Roane County, Tennessee, with a small extension into Morgan County. The population of Harriman was 6,350 at the time of the 2010 census.

Harriman is included in the Knoxville, Tennessee Metropolitan Statis ...

, first in railroad construction and then as a logger. By all accounts, he was a skilled laborer who was devoted to the welfare of his family, and a crack shot. York was also a violent alcoholic

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomina ...

prone to fighting in saloons

Saloon may refer to:

Buildings and businesses

* One of the bars in a traditional British pub

* An alternative name for a bar (establishment)

* Western saloon, a historical style of American bar

* The Saloon, a bar and music venue in San Francisc ...

. In one of the saloon fights his best friend was killed. York also accumulated several arrests within the area. His mother, a member of a pacifist Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

denomination, tried to persuade York to change his ways.

World War I

Despite his history of drinking and fighting, York attended church regularly and often led the hymn singing. A

Despite his history of drinking and fighting, York attended church regularly and often led the hymn singing. A revival meeting

A revival meeting is a series of Christian religious services held to inspire active members of a church body to gain new converts and to call sinners to repent. Nineteenth-century Baptist preacher Charles Spurgeon said, "Many blessings may come t ...

at the end of 1914 led him to a conversion experience on January 1, 1915. His congregation was the Church of Christ in Christian Union, a Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

denomination that shunned secular politics and disputes between Christian denominations. This church had no specific doctrine of pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

but it had been formed in reaction to the Methodist Episcopal Church, South's support of slavery, including armed conflict during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, and it opposed all forms of violence. In a lecture later in life, York reported his reaction to the outbreak of World War I: "I was worried clean through. I didn't want to go and kill. I believed in my Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

."Capozzola, 2008, p. 67

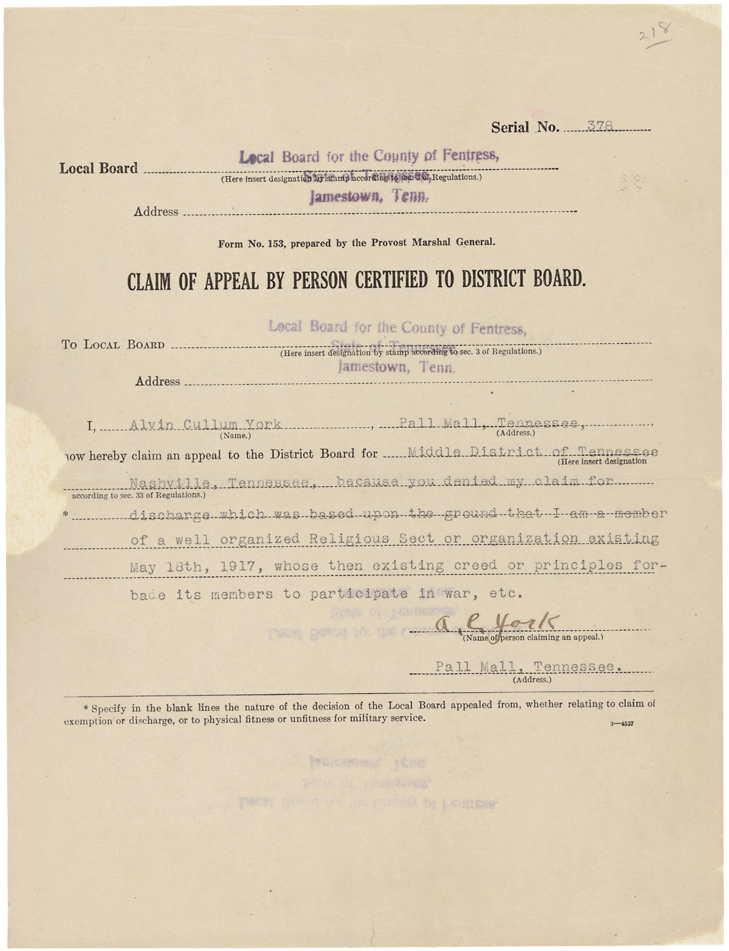

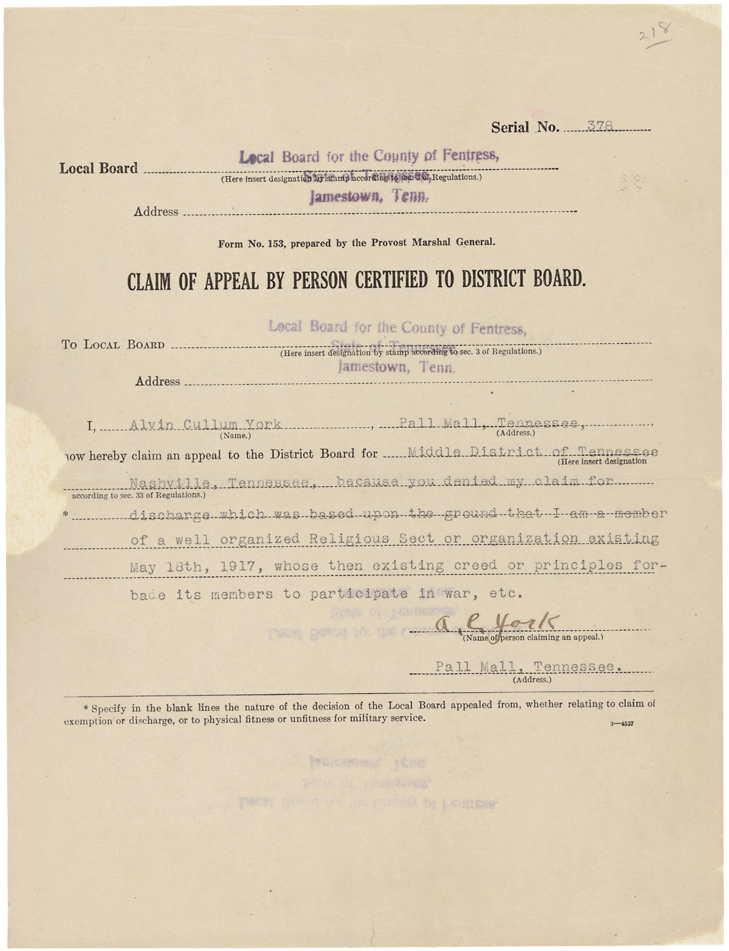

On June 5, 1917, at the age of 29, Alvin York registered for the draft as all men between 21 and 30 years of age were required to do as a result of the Selective Service Act. When he registered for the draft, he answered the question "Do you claim exemption from draft (specify grounds)?" by writing "Yes. Don't Want To Fight."Capozzola, 2008, p. 68, includes a photograph of York's Registration Card from the National Archives When his initial claim for conscientious objector status was denied, he appealed. During World War I, conscientious objector status did not exempt the objector from military duty. Such individuals could still be drafted and were given assignments that did not conflict with their anti-war principles. In November 1917, while York's application was considered, he was drafted and began his army service at Camp Gordon

Fort Gordon, formerly known as Camp Gordon, is a United States Army installation established in October 1941. It is the current home of the United States Army Signal Corps, United States Army Cyber Command, and the Cyber Center of Excellence. It ...

, Georgia.Capozzola, 2008, pp. 67–9

From the day he registered for the draft until he returned from the war on May 29, 1919, York kept a diary of his activities. In his diary, York wrote that he refused to sign documents provided by his pastor seeking a discharge from the Army on religious grounds and similar documents provided by his mother asserting a claim of exemption as the sole support of his mother and siblings. Despite his initial, signed request for an exemption, he later disclaimed ever having been a conscientious objector.

Entry into service

York served in Company G, 328th Infantry, 82nd Division. Deeply troubled by the conflict between his pacifism and his training for war, he spoke at length with hiscompany commander

A company commander is the commanding officer of a company, a military unit which typically consists of 100 to 250 soldiers, often organized into three or four smaller units called platoons. The exact organization of a company varies by countr ...

, Captain Edward Courtney Bullock Danforth Jr. (1894–1974) of Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navigable portion. Georgi ...

, and his battalion commander, Major G. Edward Buxton of Providence, Rhode Island

Providence is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. One of the oldest cities in New England, it was founded in 1636 by Roger Williams, a Reformed Baptist theologian and religious exile from the Massachusetts ...

, a devout Christian himself. Biblical passages about violence ("He that hath no sword, let him sell his cloak and buy one." "Render unto Caesar ..." "... if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight.") cited by Danforth persuaded York to reconsider the morality of his participation in the war. Granted a 10-day leave to visit home, he returned convinced that God meant for him to fight and would keep him safe, as committed to his new mission as he had been to pacifism. He served with his division in the St. Mihiel Offensive

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a major World War I battle fought from 12–15 September 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) and 110,000 French troops under the command of General John J. Pershing of the United States against ...

.

Medal of Honor action

In an October 8, 1918, attack that occurred during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, York's battalion aimed to capture German positions near Hill 223 () along the

In an October 8, 1918, attack that occurred during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, York's battalion aimed to capture German positions near Hill 223 () along the Decauville

Decauville () was a manufacturing company which was founded by Paul Decauville (1846–1922), a French pioneer in industrial railways. Decauville's major innovation was the use of ready-made sections of light, narrow gauge track fastened to stee ...

railroad north of Chatel-Chéhéry

Chatel-Chéhéry () is a commune in the Ardennes department and Grand Est region of north-eastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Ardennes department

The following is a list of the 449 communes of the Ardennes department ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. His actions that day earned him the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

. He later recalled:

Under the command of Cpl. (Acting Sergeant) Bernard Early, four non-commissioned officers, including Acting Corporal York, and thirteen privates were ordered to infiltrate the German lines to take out the machine guns. The group worked their way behind the Germans and overran the headquarters of a German unit, capturing a large group of German soldiers who were preparing a counter-attack against the U.S. troops. Early's men were contending with the prisoners when German machine gun fire suddenly peppered the area, killing six Americans and wounding three others. Several of the Americans returned fire while others guarded the prisoners. From his advantageous position, York fought the Germans. York recalled:

During the assault, a German officer led several Germans to the scene of the fighting and ran into York who shot several of them with his pistol.

Imperial German Army First Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer, commanding the 120th Reserve Infantry Regiment's 1st Battalion, emptied his pistol trying to kill York while he was contending with the machine guns. Failing to injure York, and seeing his mounting losses, he offered in English to surrender the unit to York who accepted. At the end of the engagement, York and his seven men marched their German prisoners back to the American lines. Upon returning to his unit, York reported to his brigade commander, Brigadier General Julian Robert Lindsey, who remarked: "Well York, I hear you have captured the whole German army." York replied: "No sir. I got only 132."

York's actions silenced the German machine guns and were responsible for enabling the 328th Infantry to renew its attack to capture the Decauville Railroad.Mastriano, Douglas, Colonel, U.S. Army ''Brave Hearts under Red Skies''and Douglas Mastriano

During the assault, a German officer led several Germans to the scene of the fighting and ran into York who shot several of them with his pistol.

Imperial German Army First Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer, commanding the 120th Reserve Infantry Regiment's 1st Battalion, emptied his pistol trying to kill York while he was contending with the machine guns. Failing to injure York, and seeing his mounting losses, he offered in English to surrender the unit to York who accepted. At the end of the engagement, York and his seven men marched their German prisoners back to the American lines. Upon returning to his unit, York reported to his brigade commander, Brigadier General Julian Robert Lindsey, who remarked: "Well York, I hear you have captured the whole German army." York replied: "No sir. I got only 132."

York's actions silenced the German machine guns and were responsible for enabling the 328th Infantry to renew its attack to capture the Decauville Railroad.Mastriano, Douglas, Colonel, U.S. Army ''Brave Hearts under Red Skies''and Douglas Mastriano"A Day for Heroes"

, accessed September 21, 2010

Post-battle

Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) is a military decoration awarded to ...

. A few months later, an investigation by York's chain of command resulted in an upgrade of his Distinguished Service Cross to the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valo ...

, which was presented by the commanding general of the American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (A. E. F.) was a formation of the United States Army on the Western Front of World War I. The A. E. F. was established on July 5, 1917, in France under the command of General John J. Pershing. It fought along ...

, General John J. Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was a senior United States Army officer. He served most famously as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on the We ...

. The French Republic awarded him the Croix de Guerre, Medaille Militaire and Legion of Honor.

In addition to his French medals, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

awarded York the Croce al Merito di Guerra

The War Merit Cross ( it, Croce al Merito di Guerra) is an Italian military decoration. It was instituted by King Victor Emmanuel III during World War I on 19 January 1918. The award received major changes during World War II and is issued by the I ...

and Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

decorated him with its War Medal.''New York Times''Sergeant York, War Hero, Dies", September 3, 1964

accessed September 20, 2010 He eventually received nearly 50 decorations. York's Medal of Honor citation reads: In attempting to explain his actions during the 1919 investigation that resulted in the Medal of Honor, York told General Lindsey "A higher power than man guided and watched over me and told me what to do." Lindsey replied "York, you are right." Biographer David D. Lee (2000) wrote:

Homecoming and fame

Before leaving France, York was his division's noncommissioned officer delegate to the caucus which created the American Legion, of which York was a charter member. York's heroism went unnoticed in the United States press, even in Tennessee, until the publication of the April 26, 1919, issue of the '' Saturday Evening Post'', which had a circulation in excess of 2 million. In an article titled "The Second Elder Gives Battle", journalist George Pattullo, who had learned of York's story while touring battlefields earlier in the year, laid out the themes that have dominated York's story ever since: the mountaineer, his religious faith and skill with firearms, patriotic, plainspoken and unsophisticated, an uneducated man who "seems to do everything correctly by intuition." In response, the Tennessee Society, a group of Tennesseans living in

York's heroism went unnoticed in the United States press, even in Tennessee, until the publication of the April 26, 1919, issue of the '' Saturday Evening Post'', which had a circulation in excess of 2 million. In an article titled "The Second Elder Gives Battle", journalist George Pattullo, who had learned of York's story while touring battlefields earlier in the year, laid out the themes that have dominated York's story ever since: the mountaineer, his religious faith and skill with firearms, patriotic, plainspoken and unsophisticated, an uneducated man who "seems to do everything correctly by intuition." In response, the Tennessee Society, a group of Tennesseans living in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

, arranged celebrations to greet York upon his return to the United States, including a 5-day furlough to allow for visits to New York City and Washington, D.C. York arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,690 i ...

, on May 22, stayed at the Waldorf Astoria, and attended a formal banquet in his honor. He toured the subway system in a special car before continuing to Washington, where the House of Representatives gave him a standing ovation and he met Secretary of War Newton D. Baker and the President's secretary Joe Tumulty, as President Wilson was still in Paris.

York proceeded to Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia

Fort Oglethorpe is a city predominantly in Catoosa County with some portions in Walker County in the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 10,423. It is part of the Chattanooga, TN–GA Metropolitan St ...

, where he was discharged from the service, and then to Tennessee for more celebrations. He had been home for barely a week when, on June 7, 1919, York and Gracie Loretta Williams were married by Tennessee Governor Albert H. Roberts in Pall Mall. More celebrations followed the wedding, including a week-long trip to Nashville where York accepted a special medal awarded by the state.

York refused many offers to profit from his fame, including thousands of dollars offered for appearances, product endorsements, newspaper articles, and movie rights to his life story. Instead, he lent his name to various charitable and civic causes. To support economic development, he campaigned for the Tennessee government to build a road to service his native region, succeeding when a highway through the mountains was completed in the mid-1920s and named Alvin C. York Highway. The Nashville Rotary organized the purchase, by public subscription, of a farm, the one gift that York accepted. However, it was not the fully equipped farm he was promised, requiring York to borrow money to stock it. He subsequently lost money in the farming depression that followed the war. Then the Rotary was unable to continue the installment payments on the property, leaving York to pay them himself. In 1921, he had no option but to seek public help, resulting in an extended discussion of his finances in the press, some of it sharply critical. Debt in itself was a trial: "I could get used to most any kind of hardship, but I'm not fitted for the hardship of owing money." Only an appeal to Rotary Clubs nationwide and an account of York's plight in the ''New York World'' brought in the required contributions by Christmas 1921.

After the war

In the 1920s, York formed the Alvin C. York Foundation with the mission of increasing educational opportunities in his region of Tennessee. Board members included the area's congressman, Cordell Hull, who later became Secretary of State under PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

, who was President Wilson's son-in-law, and Tennessee Governor Albert Roberts. Plans called for a non-sectarian institution providing vocational training to be called the York Agricultural Institute. York concentrated on fund-raising, though he disappointed audiences who wanted to hear about the Argonne when he instead explained that "I occupied one space in a fifty mile front. I saw so little it hardly seems worthwhile discussing it. I'm trying to forget the war in the interest of the mountain boys and girls that I grew up among." He fought first to win financial support from the state and county, then battled local leaders about the school's location. Refusing to compromise, he resigned and developed plans for a rival York Industrial School. After a series of lawsuits he gained control of the original institution and was its president when it opened in December 1929. As the Great Depression deepened, the state government failed to provide promised funds, and York mortgaged his farm to fund bus transportation for students. Even after he was ousted as president in 1936 by political and bureaucratic rivals, he continued to donate money.

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a major part of ...

overseeing the creation of Cumberland Mountain State Park

Cumberland Mountain State Park is a state park in Cumberland County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. The park consists of situated around Byrd Lake, a man-made lake created by the impoundment of Byrd Creek in the 1930s. The park ...

's Byrd Lake, one of the largest masonry projects the program ever undertook. York served as the park's superintendent until 1940. In the second half of 1930s and early 1940s, in the run-up to the America's entry in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, York was a forceful and public advocate for interventionism, calling for U.S. involvement in the war against Germany, Italy and Japan.Mastriano, pp. 176–177. At the time, U.S. public opinion was overwhelmingly in favor of the isolationist and non-interventionist approach, and York's unpopular views led to accusations that he was engaged in war-mongering. York became a relatively rare high-profile public voice for intervention. In a speech at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

A Tomb of the Unknown Soldier or Tomb of the Unknown Warrior is a monument dedicated to the services of an unknown soldier and to the common memories of all soldiers killed in war. Such tombs can be found in many nations and are usually high-prof ...

in May 1941, York said: "We must fight again! The time is not now ripe, nor will it ever be, to compromise with Hitler, or the things he stands for."

York's speeches attracted the attention of President Roosevelt, who frequently quoted York, particularly a passage from York's Tomb of the Unknown Soldier speech:

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, York attempted to re-enlist in the Army.David E. Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero (Lexington, 1985).

However, at fifty-four years of age, overweight, near-diabetic

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

, and with evidence of arthritis, he was denied enlistment as a combat soldier. Instead, he was commissioned as a major in the Army Signal Corps and he toured training camps and participated in bond drives in support of the war effort, usually paying his own travel expenses. Gen. Matthew Ridgway

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway (March 3, 1895 – July 26, 1993) was a senior officer in the United States Army, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1952–1953) and the 19th Chief of Staff of the United States Army (1953–1955). Altho ...

later recalled that York "created in the minds of farm boys and clerks ... the conviction that an aggressive soldier, well-trained and well-armed, can fight his way out of any situation." He also raised funds for war-related charities, including the Red Cross. He served on his county draft board and, when literacy requirements forced the rejection of large numbers of Fentress County men, he offered to lead a battalion of illiterates himself, saying they were "crack shots". Although York served during the war as a Signal Corps major and as a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

with the 7th Regiment of the Tennessee State Guard

The Tennessee State Guard (TNSG) is the state defense force of the state of Tennessee. The TNSG is organized as an all-volunteer military reserve force whose members drill once per month unless called to active duty. The TNSG is a branch of the ...

, newspapers continued to refer to him as "Sergeant York".

Legacy and film story

Biographer David Lee explored the reason Americans responded so favorably to his story: York cooperated with journalists in telling his life story twice in the 1920s. He allowed Nashville-born freelance journalist Sam Cowan to see his diary and submitted to interviews. The resulting 1922 biography focused on York's Appalachian background, describing his upbringing among the "purest Anglo-Saxons to be found today", emphasizing popular stereotypes without bringing the man to life. A few years later, York contacted a publisher about an edition of his war diary, but the publisher wanted additional material to flesh out the story. Then Tom Skeyhill, an Australian-born veteran of the Gallipoli campaign, visited York in Tennessee and the two became friends. On York's behalf, Skeyhill wrote an "autobiography" in the first person and was credited as the editor of ''Sergeant York: His Own Life Story and War Diary''. With a preface by Newton D. Baker, Secretary of War in World War I, it presented a one-dimensional York supplemented with tales of life in the Tennessee mountains. Reviews noted that York only promoted his life story in the interest of funding educational programs: "Perhaps York's bearing after his famous exploit in the Argonne best reveals his native greatness. ... He will not exploit himself except for his own people. All of which gives his book an appeal beyond its contents."

The mountaineer persona Cowan and Skeyhill promoted reflected York's own beliefs. In a speech at the 1939 New York World's Fair, he said:

For many years, York employed a secretary, Arthur S. Bushing, who wrote the lectures and speeches York delivered. Bushing prepared York's correspondence as well. Like the works of Cowan and Skeyhill, words commonly ascribed to York, though doubtless representing his thinking, were often composed by professional writers. York had refused several times to authorize a film version of his life story. Finally, in 1940, as York was looking to finance an interdenominational Bible school, he yielded to a persistent Hollywood producer and negotiated the contract himself. In 1941 the movie '' Sergeant York'', directed by Howard Hawks with

York cooperated with journalists in telling his life story twice in the 1920s. He allowed Nashville-born freelance journalist Sam Cowan to see his diary and submitted to interviews. The resulting 1922 biography focused on York's Appalachian background, describing his upbringing among the "purest Anglo-Saxons to be found today", emphasizing popular stereotypes without bringing the man to life. A few years later, York contacted a publisher about an edition of his war diary, but the publisher wanted additional material to flesh out the story. Then Tom Skeyhill, an Australian-born veteran of the Gallipoli campaign, visited York in Tennessee and the two became friends. On York's behalf, Skeyhill wrote an "autobiography" in the first person and was credited as the editor of ''Sergeant York: His Own Life Story and War Diary''. With a preface by Newton D. Baker, Secretary of War in World War I, it presented a one-dimensional York supplemented with tales of life in the Tennessee mountains. Reviews noted that York only promoted his life story in the interest of funding educational programs: "Perhaps York's bearing after his famous exploit in the Argonne best reveals his native greatness. ... He will not exploit himself except for his own people. All of which gives his book an appeal beyond its contents."

The mountaineer persona Cowan and Skeyhill promoted reflected York's own beliefs. In a speech at the 1939 New York World's Fair, he said:

For many years, York employed a secretary, Arthur S. Bushing, who wrote the lectures and speeches York delivered. Bushing prepared York's correspondence as well. Like the works of Cowan and Skeyhill, words commonly ascribed to York, though doubtless representing his thinking, were often composed by professional writers. York had refused several times to authorize a film version of his life story. Finally, in 1940, as York was looking to finance an interdenominational Bible school, he yielded to a persistent Hollywood producer and negotiated the contract himself. In 1941 the movie '' Sergeant York'', directed by Howard Hawks with Gary Cooper

Gary Cooper (born Frank James Cooper; May 7, 1901May 13, 1961) was an American actor known for his strong, quiet screen persona and understated acting style. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice and had a further three nominations, ...

in the title role, told about his life and Medal of Honor action. The screenplay included much fictitious material though it was based on York's ''Diary''. The marketing of the film included a visit by York to the White House where FDR praised the film. Some of the response to the film divided along political lines, with advocates of preparedness and aid to Great Britain enthusiastic ("Hollywood's first solid contribution to the national defense", said ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'') and isolationists calling it "propaganda" for the administration. It received 11 Oscar

Oscar, OSCAR, or The Oscar may refer to:

People

* Oscar (given name), an Irish- and English-language name also used in other languages; the article includes the names Oskar, Oskari, Oszkár, Óscar, and other forms.

* Oscar (Irish mythology) ...

nominations and won two, including the Academy Award for Best Actor for Cooper. It was the highest-grossing picture of 1941. York's earnings from the film, about $150,000 in the first two years as well as later royalties, resulted in a decade-long battle with the Internal Revenue Service. York eventually built part of his planned Bible school, which hosted 100 students until the late 1950s.

Political views

York originally believed in the morality of America's intervention in World War I. By the mid-1930s, he looked back more critically: "I can't see that we did any good. There's as much trouble now as there was when we were over there. I think the slogan 'A war to end war' is all wrong." He fully endorsed American preparedness, but showed sympathy for isolationism by saying that he would fight only if war came to America. A consistentDemocrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

– "I'm a Democrat first, last, and all the time", he said – in January 1941 he praised FDR

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's support for Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

and in an address at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

A Tomb of the Unknown Soldier or Tomb of the Unknown Warrior is a monument dedicated to the services of an unknown soldier and to the common memories of all soldiers killed in war. Such tombs can be found in many nations and are usually high-prof ...

on Memorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have fought and died while serving in the United States armed forces. It is observed on the last Monda ...

of that year he attacked isolationists and said that veterans understood that "liberty and freedom are so very precious that you do not fight and win them once and stop." They are "prizes awarded only to those peoples who fight to win them and then keep fighting eternally to hold them!" At times he was blunt: "I think any man who talks against the interests of his own country ought to be arrested and put in jail, not excepting senators and colonels." Everyone knew that the colonel in question was Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

.

In the late 1940s he called for toughness in dealing with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and did not hesitate to recommend using the atomic bomb in a first strike: "If they can't find anyone else to push the button, I will."Lee, 1985, 125 He questioned the failure of United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

forces to use the atomic bomb in Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

. In the 1960s he criticized Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American business executive and the eighth United States Secretary of Defense, serving from 1961 to 1968 under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He remains the ...

's plans to reduce the ranks of the National Guard

National Guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

Nat ...

and reserves: "Nothing would please Khrushchev better."

Personal life and death

York and his wife Gracie had ten children, seven sons and three daughters, most named after American historical figures: Infant son (1920, died at 4 days), Alvin Cullum, Jr. (1921–1983), George Edward Buxton (1923–2018), Woodrow Wilson (1925–1998), Samuel Huston (1928–1929), Andrew Jackson (1930–2022), Betsy Ross (born 1933), Mary Alice (1935–1991), Thomas Jefferson (1938–1972), and Infant daughter (1940, died same day).

York had health problems throughout his life. He had gallbladder surgery in the late 1920s and had

York and his wife Gracie had ten children, seven sons and three daughters, most named after American historical figures: Infant son (1920, died at 4 days), Alvin Cullum, Jr. (1921–1983), George Edward Buxton (1923–2018), Woodrow Wilson (1925–1998), Samuel Huston (1928–1929), Andrew Jackson (1930–2022), Betsy Ross (born 1933), Mary Alice (1935–1991), Thomas Jefferson (1938–1972), and Infant daughter (1940, died same day).

York had health problems throughout his life. He had gallbladder surgery in the late 1920s and had pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

in 1942. Described in 1919 as a "red-haired giant with the ruddy complexion of the outdoors" and "standing more than 6 feet ... and tipping the scale at more than 200 pounds", by 1945 he weighed 250 pounds and in 1948 he had a stroke. More strokes and another case of pneumonia followed, and he was confined to bed from 1954, further impaired by failing eyesight. He was hospitalized several times during his last two years. York died at the Veterans Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and ...

, on September 2, 1964, of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 76. After a funeral service in his Jamestown church, with Gen. Matthew Ridgway

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway (March 3, 1895 – July 26, 1993) was a senior officer in the United States Army, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1952–1953) and the 19th Chief of Staff of the United States Army (1953–1955). Altho ...

representing President Lyndon Johnson, York was buried at the Wolf River Cemetery in Pall Mall. His funeral sermon was delivered by Richard G. Humble, General Superintendent of the Churches of Christ in Christian Union. Humble also preached Mrs. York's funeral sermon in 1984.

Awards

York was the recipient of the following awards:Legacy

Controversy

Beginning soon after York's return to the United States at the end of the war, doubt and controversy periodically surfaced over whether the events detailed in his Medal of Honor documents had taken place as officially described, and whether other soldiers in York's unit should also have been recognized for their heroism.Mastriano, p. 153. Otis Merrithew (William Cutting) and Bernard Early were among those who argued against the official version. Of the 17 American soldiers who were involved in York's Medal of Honor action, six were killed. York received the Medal of Honor, and over the years, three of the others who lived through that day's fighting also received valor awards, including the Distinguished Service Cross for Early in 1929, and the Silver Star for Merrithew in 1965.Discovery of 'lost' battlefield

Middle Tennessee State University

Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU or MT) is a public university in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Founded in 1911 as a normal school, the university consists of eight Undergraduate education, undergraduate colleges as well as a college of Postgr ...

, placed the site 600 meters south of the location identified by Mastriano. Nolan's research relied on contemporary army graves registration Forms, the 82nd Division's wartime history, and maps drawn by Colonel G. Edward Buxton Jr.

Gonzalo Edward Buxton Jr. (May 13, 1880 – March 15, 1949) was a colonel in the American Expeditionary Force in World War I and the commanding officer of Sergeant Alvin C. York. In later life he was the first assistant director of the OSS.

...

and Captain Edward C. B. Danforth, both of whom walked the ground with York during the Medal of Honor investigation.

Monuments and memorials

Many places and monuments throughout the world have been named in honor of York, most notably his farm in Pall Mall, which is now open to visitors as the Sgt. Alvin C. York State Historic Park. Several government buildings have been named for York, including the Alvin C. York Veterans Hospital located in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Murfreesboro. The Alvin C. York Institute was founded in 1926 as an agricultural high school by York and residents of Fentress County and continues to serve as Jamestown's high school. York Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan,New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

was named for York in 1928.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Robert Penn Warren used York as the model for characters in two of his novels, both explorations of the burden of fame faced by battlefield heroes in peacetime. In ''At Heaven's Gate'' (1943), a Tennessee mountaineer who was awarded the Medal of Honor in World War I returns from combat, becomes a state legislator, and then a bank president. Others exploit his decency and fame for their own selfish ends as the novel explores the real-life experience of an old-fashioned hero in a cynical world. In ''The Cave'' (1959), a similar hero from a similar background has aged and become an invalid. He struggles to maintain his identity as his real self diverges from the robust legend of his youth.

A statue of York by sculptor Felix de Weldon was placed on the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol in 1968.

In the 1980s, the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

named its M247 Sergeant York, DIVAD weapon system "Sergeant York"; the project was cancelled because of technical problems and cost overruns.

In 1993, York was among 35 Medal of Honor recipients whose portraits were painted and biographies included in a boxed set of "Congressional Medal of Honor Trading Cards," issued by Eclipse Comics, Eclipse Enterprises under license from the Medal of Honor Society. The text is by Kent DeLong, the paintings by Tom Simonton, and the set edited by Catherine Yronwode.

On May 5, 2000, the United States Postal Service issued the "Distinguished Soldiers" stamps, one of which honored York.

The riderless horse in the 2004 funeral procession of President Ronald Reagan was named Sergeant York.

Laura Cantrell's 2005 song "Old Downtown" talks about York in depth.

In 2007, the 82nd Airborne Division (United States), 82nd Airborne Division's movie theater at Fort Bragg (North Carolina), Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was named York Theater.

The traveling American football trophy between University of Tennessee at Martin, UT Martin, Austin Peay State University, Austin Peay, Tennessee State University, Tennessee State, and Tennessee Technological University, Tennessee Tech is called the Alvin C. York trophy.

The U.S. Army ROTC's Sergeant York Award is presented to cadets who excel in the program and devote additional time and effort to maintaining and expanding it.

A memorial to graduates of the East Tennessee State University ROTC program who have given their lives for their country carries a quotation from York.

The Third Regiment of the Tennessee State Guard is named for York.

The Association of the United States Army published a digital graphic novel about York in 2018.

Swedish power metal band Sabaton (band), Sabaton's 2019 album ''The Great War (Sabaton album), The Great War'' contained a track titled "82nd All the Way" (What Sergeant York achieved that day, echoed from France to the USA, its 82nd all the way. Death from above is what they now say.) , a tribute to York's Medal of Honor action.

See also

* List of Medal of Honor recipients for World War I * List of members of the American Legion * List of people from Tennessee * List of people on stamps of the United StatesNotes

References

* * * Lee, David D. (2000) "York, Alvin Cullum" ''American National Biography'' (online 2000online

* * * * * *

Further reading

*online free

* * Skeyhill, Thomas. ''Sergeant York: Last of the Long Hunters'' (1930); * Yockelson, Mitchell. ''Forty-Seven Days: How Pershing's Warriors Came of Age to Defeat at the German Army in World War I''. New York: NAL, Caliber, 2016. . *

External links

Official *Alvin C. York Institute

Sgt. Alvin C. York State Historic Park

General information *

at Medal of Honor Recipients Portrayed On Film (lylefrancispadilla.com) *

Sergeant York Project

The Sergeant York Discovery Expedition (SYDE)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:York, Alvin C. 1887 births 1964 deaths United States Army personnel of World War I United States Army personnel of World War II American community activists American conscientious objectors American diarists American people of English descent American people of Scotch-Irish descent American Protestants Burials in Tennessee Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur Civilian Conservation Corps people Military personnel from Tennessee Organization founders People from Harriman, Tennessee People from Pall Mall, Tennessee Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France) Recipients of the War Merit Cross (Italy) Tennessee Democrats United States Army Medal of Honor recipients United States Army soldiers World War I recipients of the Medal of Honor American anti-communists