Seafloor spreading on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at

In some locations spreading rates have been found to be asymmetric; the half rates differ on each side of the ridge crest by about five percent. This is thought due to temperature gradients in the asthenosphere from

In some locations spreading rates have been found to be asymmetric; the half rates differ on each side of the ridge crest by about five percent. This is thought due to temperature gradients in the asthenosphere from

Animation of a mid-ocean ridge

{{DEFAULTSORT:Seafloor Spreading Geological processes Plate tectonics Oceanographical terminology

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a div ...

s, where new oceanic crust

Oceanic crust is the uppermost layer of the oceanic portion of the tectonic plates. It is composed of the upper oceanic crust, with pillow lavas and a dike complex, and the lower oceanic crust, composed of troctolite, gabbro and ultramafic ...

is formed through volcanic activity

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener and Alexander du Toit ofcontinental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pl ...

postulated that continents in motion "plowed" through the fixed and immovable seafloor. The idea that the seafloor itself moves and also carries the continents with it as it spreads from a central rift axis was proposed by Harold Hammond Hess from Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

and Robert Dietz of the U.S. Naval Electronics Laboratory in San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

in the 1960s. The phenomenon is known today as plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label= Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of larg ...

. In locations where two plates move apart, at mid-ocean ridges, new seafloor is continually formed during seafloor spreading.

Significance

Seafloor spreading helps explaincontinental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pl ...

in the theory of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label= Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of larg ...

. When oceanic plates diverge, tensional stress causes fractures to occur in the lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

. The motivating force for seafloor spreading ridges is tectonic plate slab pull at subduction zones, rather than magma pressure, although there is typically significant magma activity at spreading ridges. Plates that are not subducting are driven by gravity sliding off the elevated mid-ocean ridges a process called ridge push. At a spreading center, basaltic magma rises up the fractures and cools on the ocean floor to form new seabed

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most o ...

. Hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspo ...

s are common at spreading centers. Older rocks will be found farther away from the spreading zone while younger rocks will be found nearer to the spreading zone.

''Spreading rate'' is the rate at which an ocean basin widens due to seafloor spreading. (The rate at which new oceanic lithosphere is added to each tectonic plate on either side of a mid-ocean ridge is the ''spreading half-rate'' and is equal to half of the spreading rate). Spreading rates determine if the ridge is fast, intermediate, or slow. As a general rule, fast ridges have spreading (opening) rates of more than 90 mm/year. Intermediate ridges have a spreading rate of 40–90 mm/year while slow spreading ridges have a rate less than 40 mm/year. The highest known rate was over 200 mm/yr during the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

on the East Pacific Rise

The East Pacific Rise is a mid-ocean rise (termed an oceanic rise and not a mid-ocean ridge due to its higher rate of spreading that results in less elevation increase and more regular terrain), a divergent tectonic plate boundary located alon ...

.

In the 1960s, the past record of geomagnetic reversal

A geomagnetic reversal is a change in a planet's magnetic field such that the positions of magnetic north and magnetic south are interchanged (not to be confused with geographic north and geographic south). The Earth's field has alternate ...

s of Earth's magnetic field was noticed by observing magnetic stripe "anomalies" on the ocean floor. This results in broadly evident "stripes" from which the past magnetic field polarity can be inferred from data gathered with a magnetometer

A magnetometer is a device that measures magnetic field or magnetic dipole moment. Different types of magnetometers measure the direction, strength, or relative change of a magnetic field at a particular location. A compass is one such device, ...

towed on the sea surface or from an aircraft. The stripes on one side of the mid-ocean ridge were the mirror image of those on the other side. By identifying a reversal with a known age and measuring the distance of that reversal from the spreading center, the spreading half-rate could be computed.

In some locations spreading rates have been found to be asymmetric; the half rates differ on each side of the ridge crest by about five percent. This is thought due to temperature gradients in the asthenosphere from

In some locations spreading rates have been found to be asymmetric; the half rates differ on each side of the ridge crest by about five percent. This is thought due to temperature gradients in the asthenosphere from mantle plumes

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hots ...

near the spreading center.

Spreading center

Seafloor spreading occurs at spreading centers, distributed along the crests of mid-ocean ridges. Spreading centers end in transform faults or in overlapping spreading center offsets. A spreading center includes a seismically active plate boundary zone a few kilometers to tens of kilometers wide, a crustal accretion zone within the boundary zone where the ocean crust is youngest, and an instantaneous plate boundary - a line within the crustal accretion zone demarcating the two separating plates. Within the crustal accretion zone is a 1-2 km-wide neovolcanic zone where active volcanism occurs.Incipient spreading

In the general case, seafloor spreading starts as a rift in a continental land mass, similar to theRed Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

- East Africa Rift System today. The process starts by heating at the base of the continental crust which causes it to become more plastic and less dense. Because less dense objects rise in relation to denser objects, the area being heated becomes a broad dome (see isostasy

Isostasy (Greek ''ísos'' "equal", ''stásis'' "standstill") or isostatic equilibrium is the state of gravitational equilibrium between Earth's crust (or lithosphere) and mantle such that the crust "floats" at an elevation that depends on its ...

). As the crust bows upward, fractures occur that gradually grow into rifts. The typical rift system consists of three rift arms at approximately 120-degree angles. These areas are named triple junction

A triple junction is the point where the boundaries of three tectonic plates meet. At the triple junction each of the three boundaries will be one of three types – a ridge (R), trench (T) or transform fault (F) – and triple junctions can b ...

s and can be found in several places across the world today. The separated margins of the continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

s evolve to form passive margins. Hess' theory was that new seafloor is formed when magma is forced upward toward the surface at a mid-ocean ridge.

If spreading continues past the incipient stage described above, two of the rift arms will open while the third arm stops opening and becomes a 'failed rift' or aulacogen

An aulacogen is a failed arm of a triple junction. Aulacogens are a part of plate tectonics where oceanic and continental crust is continuously being created, destroyed, and rearranged on the Earth’s surface. Specifically, aulacogens are a ri ...

. As the two active rifts continue to open, eventually the continental crust is attenuated as far as it will stretch. At this point basaltic oceanic crust and upper mantle lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years ...

begins to form between the separating continental fragments. When one of the rifts opens into the existing ocean, the rift system is flooded with seawater and becomes a new sea. The Red Sea is an example of a new arm of the sea. The East African rift was thought to be a failed arm that was opening more slowly than the other two arms, but in 2005 the Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

n Afar Geophysical Lithospheric Experiment reported that in the Afar region

The Afar Region (; aa, Qafar Rakaakayak; am, አፋር ክልል), formerly known as Region 2, is a regional state in northeastern Ethiopia and the homeland of the Afar people. Its capital is the planned city of Semera, which lies on the pave ...

, September 2005, a 60 km fissure opened as wide as eight meters. During this period of initial flooding the new sea is sensitive to changes in climate and eustasy. As a result, the new sea will evaporate (partially or completely) several times before the elevation of the rift valley has been lowered to the point that the sea becomes stable. During this period of evaporation large evaporite deposits will be made in the rift valley. Later these deposits have the potential to become hydrocarbon seals and are of particular interest to petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crud ...

geologists

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althou ...

.

Seafloor spreading can stop during the process, but if it continues to the point that the continent is completely severed, then a new ocean basin is created. The Red Sea has not yet completely split Arabia from Africa, but a similar feature can be found on the other side of Africa that has broken completely free. South America once fit into the area of the Niger Delta

The Niger Delta is the delta of the Niger River sitting directly on the Gulf of Guinea on the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria. It is located within nine coastal southern Nigerian states, which include: all six states from the South South geopolitic ...

. The Niger River has formed in the failed rift arm of the triple junction

A triple junction is the point where the boundaries of three tectonic plates meet. At the triple junction each of the three boundaries will be one of three types – a ridge (R), trench (T) or transform fault (F) – and triple junctions can b ...

.

Continued spreading and subduction

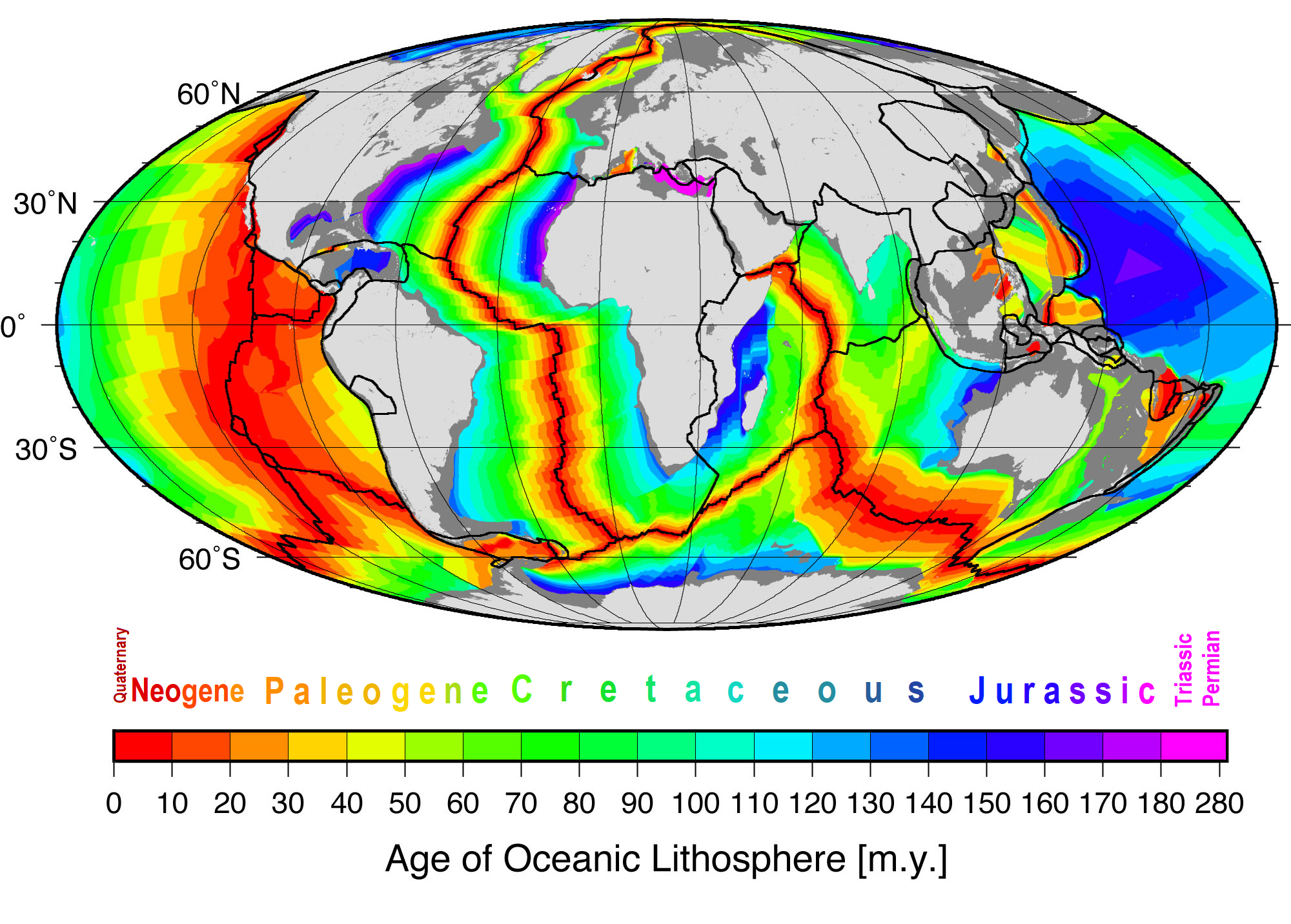

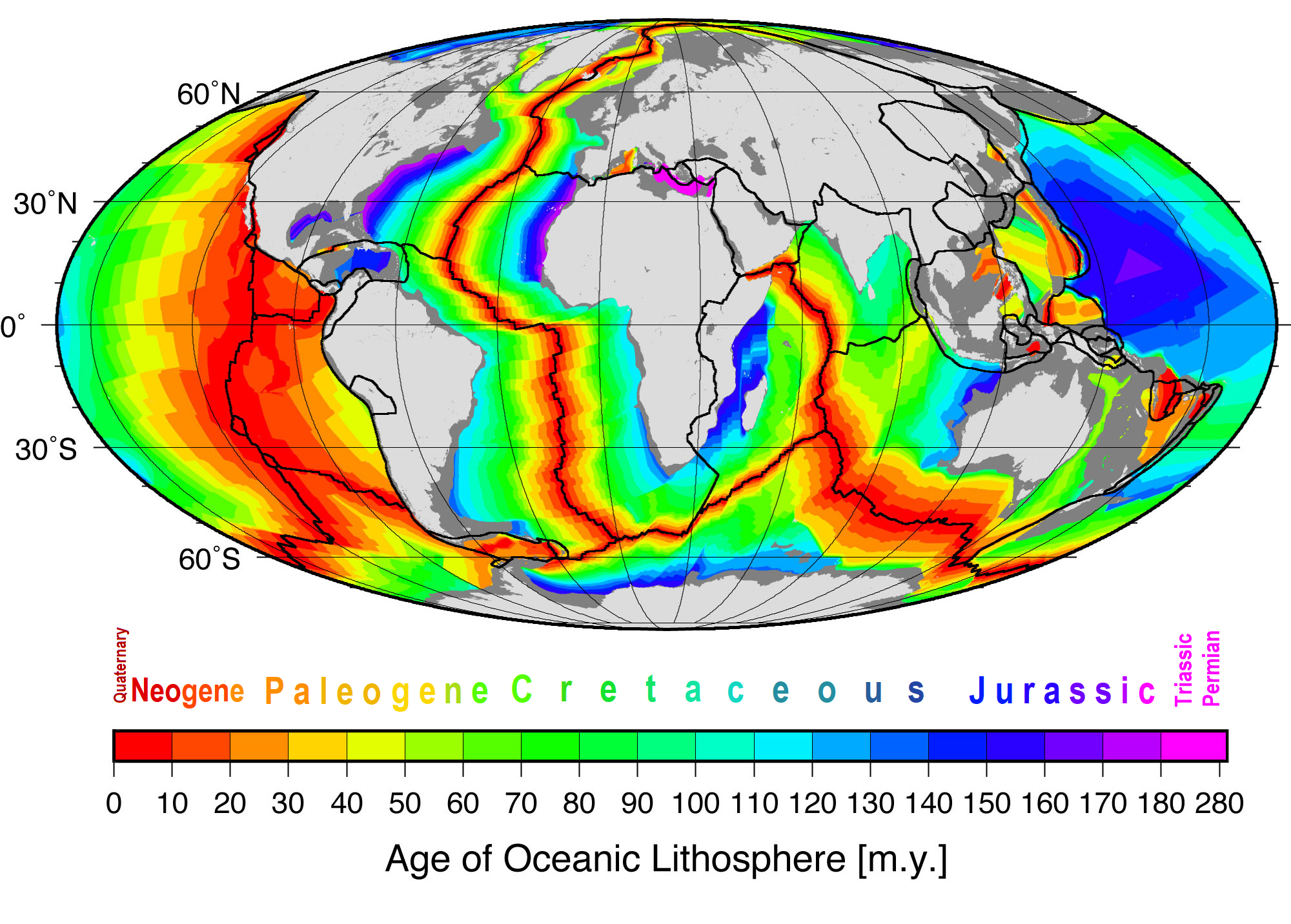

As new seafloor forms and spreads apart from the mid-ocean ridge it slowly cools over time. Older seafloor is, therefore, colder than new seafloor, and older oceanic basins deeper than new oceanic basins due to isostasy. If the diameter of the earth remains relatively constant despite the production of new crust, a mechanism must exist by which crust is also destroyed. The destruction of oceanic crust occurs at subduction zones where oceanic crust is forced under either continental crust or oceanic crust. Today, the Atlantic basin is actively spreading at theMid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North A ...

. Only a small portion of the oceanic crust produced in the Atlantic is subducted. However, the plates making up the Pacific Ocean are experiencing subduction along many of their boundaries which causes the volcanic activity in what has been termed the Ring of Fire

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt) is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many volcanic eruptions and earthquakes occur. The Ring ...

of the Pacific Ocean. The Pacific is also home to one of the world's most active spreading centers (the East Pacific Rise) with spreading rates of up to 145 +/- 4 mm/yr between the Pacific and Nazca plates. The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a slow-spreading center, while the East Pacific Rise is an example of fast spreading. Spreading centers at slow and intermediate rates exhibit a rift valley while at fast rates an axial high is found within the crustal accretion zone. The differences in spreading rates affect not only the geometries of the ridges but also the geochemistry of the basalts that are produced.

Since the new oceanic basins are shallower than the old oceanic basins, the total capacity of the world's ocean basins decreases during times of active sea floor spreading. During the opening of the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

, sea level was so high that a Western Interior Seaway formed across North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

from the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

to the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

.

Debate and search for mechanism

At the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (and in other mid-ocean ridges), material from the uppermantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

rises through the faults between oceanic plates to form new crust as the plates move away from each other, a phenomenon first observed as continental drift. When Alfred Wegener first presented a hypothesis of continental drift in 1912, he suggested that continents plowed through the ocean crust. This was impossible: oceanic crust is both more dense and more rigid than continental crust. Accordingly, Wegener's theory wasn't taken very seriously, especially in the United States.

At first the driving force for spreading was argued to be convection currents in the mantle. Since then, it has been shown that the motion of the continents is linked to seafloor spreading by the theory of plate tectonics, which is driven by convection that includes the crust itself as well.

The driver for seafloor spreading in plates with active margin

Active may refer to:

Music

* ''Active'' (album), a 1992 album by Casiopea

* Active Records, a record label

Ships

* ''Active'' (ship), several commercial ships by that name

* HMS ''Active'', the name of various ships of the British Roya ...

s is the weight of the cool, dense, subducting slabs that pull them along, or slab pull. The magmatism at the ridge is considered to be passive upwelling, which is caused by the plates being pulled apart under the weight of their own slabs. This can be thought of as analogous to a rug on a table with little friction: when part of the rug is off of the table, its weight pulls the rest of the rug down with it. However, the Mid-Atlantic ridge itself is not bordered by plates that are being pulled into subduction zones, except the minor subduction in the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc be ...

and Scotia Arc. In this case the plates are sliding apart over the mantle upwelling in the process of ridge push.

Seafloor global topography: cooling models

The depth of the seafloor (or the height of a location on a mid-ocean ridge above a base-level) is closely correlated with its age (age of the lithosphere where depth is measured). The age-depth relation can be modeled by the cooling of a lithosphere plate or mantle half-space in areas without significantsubduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

.

Cooling mantle model

In the mantle half-space model, the seabed height is determined by theoceanic lithosphere

A lithosphere () is the rigid, outermost rocky shell of a terrestrial planet or natural satellite. On Earth, it is composed of the crust and the portion of the upper mantle that behaves elastically on time scales of up to thousands of years or ...

and mantle temperature, due to thermal expansion. The simple result is that the ridge height or ocean depth is proportional to the square root of its age. Oceanic lithosphere is continuously formed at a constant rate at the mid-ocean ridge

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a div ...

s. The source of the lithosphere has a half-plane shape (''x'' = 0, ''z'' < 0) and a constant temperature ''T''1. Due to its continuous creation, the lithosphere at ''x'' > 0 is moving away from the ridge at a constant velocity ''v'', which is assumed large compared to other typical scales in the problem. The temperature at the upper boundary of the lithosphere (''z'' = 0) is a constant ''T''0 = 0. Thus at ''x'' = 0 the temperature is the Heaviside step function

The Heaviside step function, or the unit step function, usually denoted by or (but sometimes , or ), is a step function, named after Oliver Heaviside (1850–1925), the value of which is zero for negative arguments and one for positive argum ...

. The system is assumed to be at a quasi- steady state, so that the temperature distribution is constant in time, i.e.

By calculating in the frame of reference of the moving lithosphere (velocity ''v''), which has spatial coordinate and the heat equation

In mathematics and physics, the heat equation is a certain partial differential equation. Solutions of the heat equation are sometimes known as caloric functions. The theory of the heat equation was first developed by Joseph Fourier in 1822 for ...

is:

:

where is the thermal diffusivity

In heat transfer analysis, thermal diffusivity is the thermal conductivity divided by density and specific heat capacity at constant pressure. It measures the rate of transfer of heat of a material from the hot end to the cold end. It has the SI ...

of the mantle lithosphere.

Since ''T'' depends on ''x and ''t'' only through the combination :

:

Thus:

:

It is assumed that is large compared to other scales in the problem; therefore the last term in the equation is neglected, giving a 1-dimensional diffusion equation:

:

with the initial conditions

:

The solution for is given by the error function

In mathematics, the error function (also called the Gauss error function), often denoted by , is a complex function of a complex variable defined as:

:\operatorname z = \frac\int_0^z e^\,\mathrm dt.

This integral is a special (non- elementa ...

:

:.

Due to the large velocity, the temperature dependence on the horizontal direction is negligible, and the height at time ''t'' (i.e. of sea floor of age ''t'') can be calculated by integrating the thermal expansion over ''z'':

:

where is the effective volumetric thermal expansion

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to change its shape, area, volume, and density in response to a change in temperature, usually not including phase transitions.

Temperature is a monotonic function of the average molecular kin ...

coefficient, and ''h0'' is the mid-ocean ridge height (compared to some reference).

The assumption that ''v'' is relatively large is equivalent to the assumption that the thermal diffusivity is small compared to , where ''L'' is the ocean width (from mid-ocean ridges to continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

) and ''A'' is the age of the ocean basin.

The effective thermal expansion coefficient is different from the usual thermal expansion coefficient due to isostasic effect of the change in water column height above the lithosphere as it expands or retracts. Both coefficients are related by:

:

where is the rock density and is the density of water.

By substituting the parameters by their rough estimates:

:

we have:

:

where the height is in meters and time is in millions of years. To get the dependence on ''x'', one must substitute ''t'' = ''x''/''v'' ~ ''Ax''/''L'', where ''L'' is the distance between the ridge to the continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

(roughly half the ocean width), and ''A'' is the ocean basin age.

Rather than height of the ocean floor above a base or reference level , the depth of the ocean is of interest. Because (with measured from the ocean surface) we can find that:

:; for the eastern Pacific for example, where is the depth at the ridge crest, typically 2600 m.

Cooling plate model

The depth predicted by the square root of seafloor age derived above is too deep for seafloor older than 80 million years. Depth is better explained by a cooling lithosphere plate model rather than the cooling mantle half-space. The plate has a constant temperature at its base and spreading edge. Analysis of depth versus age and depth versus square root of age data allowed Parsons and Sclater to estimate model parameters (for the North Pacific): :~125 km for lithosphere thickness : at base and young edge of plate : Assuming isostatic equilibrium everywhere beneath the cooling plate yields a revised age depth relationship for older sea floor that is approximately correct for ages as young as 20 million years: :meters Thus older seafloor deepens more slowly than younger and in fact can be assumed almost constant at ~6400 m depth. Parsons and Sclater concluded that some style of mantle convection must apply heat to the base of the plate everywhere to prevent cooling down below 125 km and lithosphere contraction (seafloor deepening) at older ages. Their plate model also allowed an expression for conductive heat flow, ''q(t)'' from the ocean floor, which is approximately constant at beyond 120 million years: :See also

* * * DSV ''ALVIN'' the research submersible that explored spreading centers in the Atlantic ( Project FAMOUS) and Pacific Oceans ( RISE project).References

External links

Animation of a mid-ocean ridge

{{DEFAULTSORT:Seafloor Spreading Geological processes Plate tectonics Oceanographical terminology