Scottish Catholic Church on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Catholic Church in Scotland overseen by the

The Catholic Church in Scotland overseen by the

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of

That remained the case until the

That remained the case until the

Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation deteriorated.J. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5'' (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), , pp. 416–7.

The Pope appointed Thomas Nicolson as the first

Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation deteriorated.J. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5'' (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), , pp. 416–7.

The Pope appointed Thomas Nicolson as the first

While most of the landlords responsible for the Highland Clearances did not target people for ethnic or religious reasons, there is evidence of anti-Catholicism among some of them. In particular, large numbers of Catholics emigrated from the Western Highlands in the period 1770 to 1810 and there is evidence that anti Catholic sentiment (along with famine, poverty and rising rents) was a contributory factor in that period. Noteworthy figures in the late stages of the specifically Catholic clearances and emigration from Scotland include Bishop Alexander Macdonnell, who, against the odds, made possible a Canadian Gaelic-speaking pioneer settlement in Glengarry County, Ontario,

While most of the landlords responsible for the Highland Clearances did not target people for ethnic or religious reasons, there is evidence of anti-Catholicism among some of them. In particular, large numbers of Catholics emigrated from the Western Highlands in the period 1770 to 1810 and there is evidence that anti Catholic sentiment (along with famine, poverty and rising rents) was a contributory factor in that period. Noteworthy figures in the late stages of the specifically Catholic clearances and emigration from Scotland include Bishop Alexander Macdonnell, who, against the odds, made possible a Canadian Gaelic-speaking pioneer settlement in Glengarry County, Ontario,

There are four entities that encompass Scotland, England, and Wales.

* The

There are four entities that encompass Scotland, England, and Wales.

* The

Between 1982 and 2010, the proportion of Scottish Catholics dropped 18%, baptisms dropped 39%, and Catholic church marriages dropped 63%. The number of priests also dropped. Between the

Between 1982 and 2010, the proportion of Scottish Catholics dropped 18%, baptisms dropped 39%, and Catholic church marriages dropped 63%. The number of priests also dropped. Between the

Bishops' Conference of ScotlandFacts about Catholics in ScotlandScottish Catholic ObserverNational Library of Scotland: SCOTTISH SCREEN ARCHIVE

(selection of archive films relating to Catholicism in Scotland) {{DEFAULTSORT:Catholic Church In Scotland

The Catholic Church in Scotland overseen by the

The Catholic Church in Scotland overseen by the Scottish Bishops' Conference

The Bishops' Conference of Scotland (BCOS), under the trust of the Catholic National Endowment Trust, and based in Airdrie, North Lanarkshire, is an episcopal conference for archbishops and bishops of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland. Th ...

, is part of the worldwide Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

headed by the Pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

. After being firmly established in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

for nearly a millennium, the Catholic Church was outlawed following the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Scotland broke with the Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterian in its outlook. It was part of the wider European Protestant Refor ...

in 1560. Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and later the combined United Kingdom in the late 18th century and early 19th century, that involved reducing and removing many of the restricti ...

in 1793 and 1829 helped Catholics regain both religious and civil rights. In 1878, the Catholic hierarchy was formally restored. Throughout these changes, several pockets in Scotland retained a significant pre-Reformation Catholic population, including Banffshire, the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebr ...

, and more northern parts of the Highlands

Highland is a broad term for areas of higher elevation, such as a mountain range or mountainous plateau.

Highland, Highlands, or The Highlands, may also refer to:

Places Albania

* Dukagjin Highlands

Armenia

* Armenian Highlands

Australia

*Sou ...

, Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council area of Dumfries and Galloway.

A native or ...

at Terregles House

Terregles House was a late 18th-century country house, located near Terregles, in the historical county of Kirkcudbrightshire around 2 miles west of Dumfries in Scotland. It replaced an earlier tower house, which had served as the seat of the ...

, Munches House, Kirkconnell House, New Abbey

New Abbey ( gd, An Abaid Ùr) is a village in the historical county of Kirkcudbrightshire in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. It is south of Dumfries. The summit of the prominent hill Criffel is to the south.

History

The village has a wealt ...

and Parton House and at Traquair

Traquair ( gd, Cille Bhrìghde) is a small village and civil parish in the Scottish Borders; until 1975 it was in the county of Peeblesshire. The village is situated on the B709 road south of Innerleithen at .

History

Traquair, said to mea ...

in Peebleshire

Peeblesshire ( gd, Siorrachd nam Pùballan), the County of Peebles or Tweeddale is a historic county of Scotland. Its county town is Peebles, and it borders Midlothian to the north, Selkirkshire to the east, Dumfriesshire to the south, and Lana ...

.

In 1716, Scalan seminary was established in the Highlands and rebuilt in the 1760s by Bishop John Geddes, a well-known figure in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

during the Scottish Enlightenment. When Scottish national poet

A national poet or national bard is a poet held by tradition and popular acclaim to represent the identity, beliefs and principles of a particular national culture. The national poet as culture hero is a long-standing symbo ...

Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who hav ...

, who also gifted the Bishop with the volume now known as '' The Geddes Burns'', wrote to a correspondent that "the first hat is, finestcleric character I ever saw was a Roman Catholick", he was referring to Bishop John Geddes. The Gàidhealtachd

The (; English: ''Gaeldom'') usually refers to the Highlands and Islands of Scotland and especially the Scottish Gaelic-speaking culture of the area. The similar Irish language word refers, however, solely to Irish-speaking areas.

The term ...

has been both Catholic and Protestant in modern times. A number of Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well ...

-speaking areas, including Barra

Barra (; gd, Barraigh or ; sco, Barra) is an island in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, and the second southernmost inhabited island there, after the adjacent island of Vatersay to which it is connected by a short causeway. The island is name ...

, Benbecula

Benbecula (; gd, Beinn nam Fadhla or ) is an island of the Outer Hebrides in the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Scotland. In the 2011 census, it had a resident population of 1,283 with a sizable percentage of Roman Catholics. It is in a ...

, South Uist

South Uist ( gd, Uibhist a Deas, ; sco, Sooth Uist) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the ...

, Eriskay

Eriskay ( gd, Èirisgeigh), from the Old Norse for "Eric's Isle", is an island and community council area of the Outer Hebrides in northern Scotland with a population of 143, as of the 2011 census. It lies between South Uist and Barra and is ...

, and Moidart

Moidart ( ; ) is part of the remote and isolated area of Scotland, west of Fort William, known as the Rough Bounds. Moidart itself is almost surrounded by bodies of water. Loch Shiel cuts off the eastern boundary of the district (along a sout ...

, are mainly Catholic. Poet and novelist Angus Peter Campbell writes frequently about the Catholic Church in his work. (See also the "Religion of the Yellow Stick

The religion of the yellow stick ( gd, Creideamh a’ bhata-bhuidhe) was a facetious name given to the enforcement of the Church of Scotland among certain Roman Catholic churchgoers who lived in the Hebrides of Scotland. Such actions, however, were ...

".)

In the 2011 census, 16% of the population of Scotland

The demography of Scotland includes all aspects of population, past and present, in the area that is now Scotland. Scotland has a population of 5,463,300, as of 2019. The population growth rate in 2011 was estimated as 0.6% per annum according ...

described themselves as being Catholic, compared with 32% affiliated with the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

. Many Roman Catholics are Scottish Highland

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

minorities or the descendants of Irish immigrants and of Highland migrants who moved to Scotland's cities and towns during the 19th century, especially during the famine in Ireland. However, there are also significant numbers of people of Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, Lithuanian, and Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

descent, with more recent Polish immigrants again boosting the numbers of continental Catholic Europeans in Scotland. Owing to immigration (overwhelmingly white European), it is estimated that, in 2009, there were about 850,000 Catholics in a country of 5.1 million. Between 1994 and 2002, Catholic attendance in Scotland declined 19% to just over 200,000. By 2008, the Catholic Bishops' Conference of Scotland estimated that 184,283 attended Mass regularly.

History

Establishment

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now lowland Scotland from Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of Britannia

Britannia () is the national personification of Britain as a helmeted female warrior holding a trident and shield. An image first used in classical antiquity, the Latin ''Britannia'' was the name variously applied to the British Isles, Great ...

. It is presumed to have survived among the Brythonic enclaves in the south of modern Scotland, but retreated as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced. Scotland was largely converted by Irish-Scots missions associated with figures such as St Columba from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions tended to found monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas. Partly as a result of these factors, some scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity, in which abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The ...

s were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy were more relaxed, and there were some significant differences in practice with Roman Rite, particularly the form of tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice i ...

and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-seventh century.C. Evans, "The Celtic Church in Anglo-Saxon times", in J. D. Woods, D. A. E. Pelteret, ''The Anglo-Saxons, synthesis and achievement'' (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1985), , pp. 77–89. After the reconversion of Scandinavian Scotland

Scandinavian Scotland was the period from the 8th to the 15th centuries during which Vikings and Norse settlers, mainly Norwegians and to a lesser extent other Scandinavians, and their descendants colonised parts of what is now the periphery of ...

from the tenth century, Christianity under papal authority was the dominant religion of the kingdom.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , pp. 67–8.

Medieval Catholicism

In the Norman period the Scottish church underwent a series of reforms and transformations. With royal and lay patronage, a clearer parochial structure based around local churches was developed.A. Macquarrie, ''Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation'' (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), , pp. 109–117. Large numbers of new foundations, which followed continental forms of reformed monasticism, began to predominate and the Scottish church established its independence from England and developed a clearer diocesan structure, becoming a "special daughter of the see of Rome" but lacking leadership in the form of archbishops.P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, ''A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry'' (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), , pp. 26–9. In the Late Middle Ages the problems of schism in the Catholic Church allowed the Scottish Crown to gain greater influence over senior appointments and two archbishoprics had been established by the end of the fifteenth century.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 76–87. While some historians have discerned a decline of monasticism in the Late Middle Ages, the mendicant orders offriar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders founded in the twelfth or thirteenth century; the term distinguishes the mendicants' itinerant apostolic character, exercised broadly under the jurisdiction of a superior general, from the ...

s grew, particularly in the expanding burghs, to meet the spiritual needs of the population. New saints and cults of devotion also proliferated. Despite problems over the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and some evidence of heresy in this period, the church in Scotland remained relatively stable before the Reformation in the sixteenth century.

Scottish Reformation

That remained the case until the

That remained the case until the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Scotland broke with the Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterian in its outlook. It was part of the wider European Protestant Refor ...

in the mid-16th century, when the Church in Scotland broke with the papacy and adopted a Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

confession in 1560. At that point, the celebration of the Catholic mass was outlawed. Although officially illegal, the Catholic Church survived in parts of Scotland. The hierarchy of the church played a relatively small role and the initiative was left to lay leaders. Where nobles or local lairds offered protection it continued to thrive, as with Clanranald on South Uist

South Uist ( gd, Uibhist a Deas, ; sco, Sooth Uist) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the ...

, or in the north-east where the Earl of Huntly

Marquess of Huntly (traditionally spelled Marquis in Scotland; Scottish Gaelic: ''Coileach Strath Bhalgaidh'') is a title in the Peerage of Scotland that was created on 17 April 1599 for George Gordon, 6th Earl of Huntly. It is the oldest existin ...

was the most important figure. In these areas Catholic sacraments and practices were maintained with relative openness. Members of the nobility were probably reluctant to pursue each other over matters of religion because of strong personal and social ties. An English report in 1600 suggested that a third of nobles and gentry were still Catholic in inclination.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , p. 133. In most of Scotland, Catholicism became an underground faith in private households, connected by ties of kinship. This reliance on the household meant that women often became important as the upholders and transmitters of the faith, such as in the case of Lady Fernihurst in the Borders. They transformed their households into centres of religious activity and offered places of safety for priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

s.J. E. A. Dawson, ''Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , pp. 232.

Because the reformed kirk took over the existing structures and assets of the Church, any attempted recovery by the Catholic hierarchy was extremely difficult. After the collapse of Mary's cause in the civil wars in the 1570s, and any hope of a national restoration of the old faith, the hierarchy began to treat Scotland as a mission area. The leading order of the Counter-reformation, the newly founded Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

, initially took relatively little interest in Scotland as a target of missionary work. Their effectiveness was limited by rivalries between different orders at Rome. The initiative was taken by a small group of Scots connected with the Crichton family, who had supplied the bishops of Dunkeld

Dunkeld (, sco, Dunkell, from gd, Dùn Chailleann, "fort of the Caledonians") is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The location of a historic cathedral, it lies on the north bank of the River Tay, opposite Birnam. Dunkeld lies close to t ...

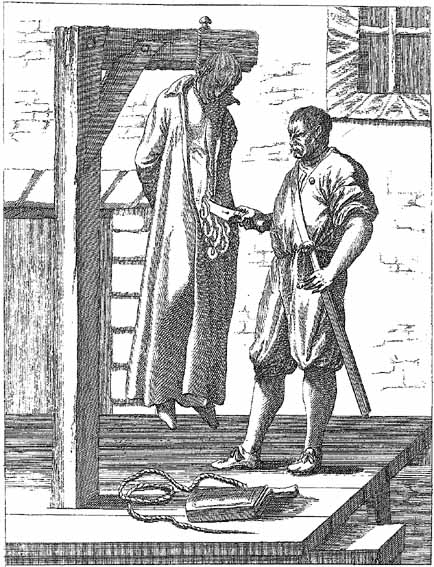

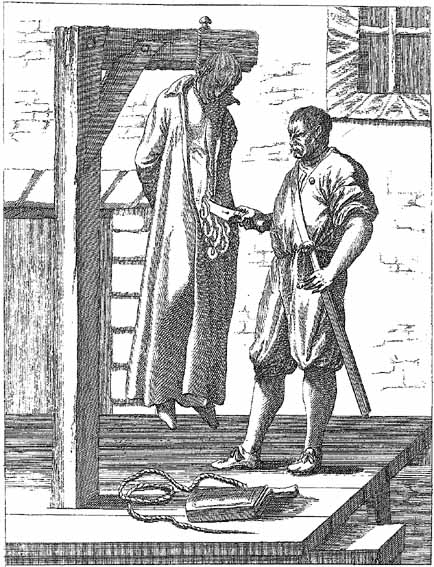

. They joined the Jesuit order and returned to attempt conversions. Their focus was mainly on the court, which led them into involvement in a series of complex political plots and entanglements. The majority of surviving Scottish lay followers were largely ignored. Some were to convert to the Catholic Church, as did John Ogilvie (1569–1615), who went on to be ordained a priest in 1610, later being hanged for proselytism

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invol ...

in Glasgow and often thought of as the only Scottish Catholic martyr of the Reformation era. Nevertheless, the Catholic Church's illegal status had a devastating impact on The Church's fortunes, although a significant congregation did continue to adhere, especially in the more remote Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands.John Prebble, ''Culloden'' (Pimlico: London, 1961), p. 50.

Decline from the 17th century

Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation deteriorated.J. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5'' (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), , pp. 416–7.

The Pope appointed Thomas Nicolson as the first

Numbers probably reduced in the seventeenth century and organisation deteriorated.J. T. Koch, ''Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5'' (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), , pp. 416–7.

The Pope appointed Thomas Nicolson as the first Vicar Apostolic

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pre ...

over the mission in 1694.M. Lynch, ''Scotland: A New History'' (London: Pimlico, 1992), , p. 365. The country was organised into districts and by 1703 there were thirty-three Catholic clergy. In 1733 it was divided into two vicariates, one for the Highland and one for the Lowland, each under a bishop. A Catholic seminary in Scalan

The Scalan was once a seminary and was one of the few places in Scotland where the Roman Catholic faith was kept alive during the troubled times of the 18th century.

History

For much of the 18th century, the college at Scalan in the Braes of Gl ...

in Glenlivet

Glenlivet (Scottish Gaelic: Gleann Lìobhait) is the glen in the Scottish Highlands through which the River Livet flows.

The river rises high in the Ladder Hills, flows through the village of Tomnavoulin and onto the Bridgend of Glenlivet, ...

was the preliminary centre of education for Catholic priests in the area. It was illegal, and it was burned to the ground on several occasions by redcoat soldiers sent from beyond The Highlands. Beyond Scalan

The Scalan was once a seminary and was one of the few places in Scotland where the Roman Catholic faith was kept alive during the troubled times of the 18th century.

History

For much of the 18th century, the college at Scalan in the Braes of Gl ...

there were six attempts to found a seminary in the Highlands between 1732 and 1838, all suffering financially under Catholicism's illegal status. Clergy entered the country secretly and although services were illegal they were maintained.

The aftermath of the failed Jacobite risings

, war =

, image = Prince James Francis Edward Stuart by Louis Gabriel Blanchet.jpg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = James Francis Edward Stuart, Jacobite claimant between 1701 and 1766

, active ...

in 1715 and 1745 further increased the persecution faced by Roman Catholics in Scotland.

According to Bishop John Geddes, "Early in the spring of 1746, some ships of war came to the coast of the isle of Barra

Barra (; gd, Barraigh or ; sco, Barra) is an island in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, and the second southernmost inhabited island there, after the adjacent island of Vatersay to which it is connected by a short causeway. The island is name ...

and landed some men, who threatened they would lay desolate the whole island if the priest was not delivered up to them. Father James Grant, who was missionary then, and afterward Bishop, being informed of the threats in a safe retreat in which he was in a little island, surrendered himself, and was carried prisoner to Mingarry Castle on the Western coast (i.e. Ardnamurchan

Ardnamurchan (, gd, Àird nam Murchan: headland of the great seas) is a peninsula in the ward management area of Lochaber, Highland, Scotland, noted for being very unspoiled and undisturbed. Its remoteness is accentuated by the main access ...

) where he was detained for some weeks."

After long and cruel imprisonment with other Roman Catholic priests at Inverness and in a prison hulk

A prison ship, often more accurately described as a prison hulk, is a current or former seagoing vessel that has been modified to become a place of substantive detention for convicts, prisoners of war or civilian internees. While many nation ...

anchored in the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

, Grant was deported to the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and warned never to return to the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

. Like the other priests deported with him, Fr. Grant returned to Scotland almost immediately. His fellow prisoner, Father Alexander Cameron, the younger brother to the Chief of Clan Cameron

Clan Cameron is a West Highland Scottish clan, with one main branch Lochiel, and numerous cadet branches. The Clan Cameron lands are in Lochaber and within their lands lies Ben Nevis which is the highest mountain in the British Isles. The Chie ...

, was less fortunate and died in the prison hulk due to the hardship of his imprisonment. During the 21st century, the Knights of St. Columba at the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

launched a campaign to canonize Fr. Cameron, "with the hope that he will become a great saint for Scotland and that our nation will merit from his intercession." They erected a small petition book at their altar of St. Joseph in the University Catholic Chapel, Turnbull Hall. It is one of the necessary prerequisites for Canonisation

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of s ...

in the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

that there is a Cult of Devotion to the saint.

Exact numbers of communicants are uncertain, given the illegal status of Catholicism. In 1755 it was estimated that there were some 16,500 communicants, mainly in the north and west.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 298–9. In 1764, "the total Catholic population in Scotland would have been about 33,000 or 2.6% of the total population. Of these 23,000 were in the Highlands". Another estimate for 1764 is of 13,166 Catholics in the Highlands, perhaps a quarter of whom had emigrated by 1790,Lynch, Michael,''Scotland, A New History'' (Pimlico: London, 1992), p. 367. and another source estimates Catholics as perhaps 10% of the population.

Impact of the Clearances

While most of the landlords responsible for the Highland Clearances did not target people for ethnic or religious reasons, there is evidence of anti-Catholicism among some of them. In particular, large numbers of Catholics emigrated from the Western Highlands in the period 1770 to 1810 and there is evidence that anti Catholic sentiment (along with famine, poverty and rising rents) was a contributory factor in that period. Noteworthy figures in the late stages of the specifically Catholic clearances and emigration from Scotland include Bishop Alexander Macdonnell, who, against the odds, made possible a Canadian Gaelic-speaking pioneer settlement in Glengarry County, Ontario,

While most of the landlords responsible for the Highland Clearances did not target people for ethnic or religious reasons, there is evidence of anti-Catholicism among some of them. In particular, large numbers of Catholics emigrated from the Western Highlands in the period 1770 to 1810 and there is evidence that anti Catholic sentiment (along with famine, poverty and rising rents) was a contributory factor in that period. Noteworthy figures in the late stages of the specifically Catholic clearances and emigration from Scotland include Bishop Alexander Macdonnell, who, against the odds, made possible a Canadian Gaelic-speaking pioneer settlement in Glengarry County, Ontario, Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of th ...

Canada for the Glengarry Fencibles, a specifically Catholic regiment in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, and their families, after its disbandment.

Large-scale Catholic immigration

During the 19th century, Irish immigration substantially increased the number of Catholics in the country, especially inGlasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

and its vicinity, and the West of Scotland. Initially, clergymen from the recusant

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

tradition of North-East Scotland played an important part in providing support. Later Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

, and Lithuanian immigrants reinforced the numbers.

The Catholic hierarchy was re-established in 1878 by Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

at the beginning of his pontificate. Six new dioceses were created: five of them

were organised into a single province with the Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh

The Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh is the ordinary of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh. The archdiocese covers an area of 5,504 km2. The metropolitan see is in the City of Edinburgh where the archbishop's s ...

as metropolitan; the Diocese of Glasgow remained separate and directly subject to the Apostolic See.

Sectarian tensions

Mass immigration to Scotland saw the emergence of sectarian tensions. In 1923, theChurch of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

produced a (since repudiated) report, entitled ''The Menace of the Irish Race to our Scottish Nationality'', accusing the largely immigrant Catholic population of subverting Presbyterian values and of spreading drunkenness, crime, and financial imprudence. Rev. John White, one of the senior leadership of the Church of Scotland at the time, called for a "racially pure" Scotland, declaring "Today there is a movement throughout the world towards the rejection of non-native constituents and the crystallization of national life from native elements."

Such officially hostile attitudes started to wane considerably from the 1930s and 1940s onwards, especially as the leadership of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

learned of what was happening in eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

-conscious Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and of the dangers of creating a "racially pure" national church; particularly as German people

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

who were of even partially Slavic or Jewish ancestry were not considered "true" members of the Volk

The German noun ''Volk'' () translates to people,

both uncountable in the sense of ''people'' as in a crowd, and countable (plural ''Völker'') in the sense of '' a people'' as in an ethnic group or nation (compare the English term '' folk ...

.

Social change and communal divisions

In 1986, the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland expressly repudiated the sections of theWestminster Confession

The Westminster Confession of Faith is a Reformed confession of faith. Drawn up by the 1646 Westminster Assembly as part of the Westminster Standards to be a confession of the Church of England, it became and remains the " subordinate standard ...

directly attacking the Catholic Church. In 1990, both the Church of Scotland and the Catholic Church were founding members of the ecumenical bodies Churches Together in Britain and Ireland and Action of Churches Together in Scotland

Action may refer to:

* Action (narrative), a literary mode

* Action fiction, a type of genre fiction

* Action game, a genre of video game

Film

* Action film, a genre of film

* ''Action'' (1921 film), a film by John Ford

* ''Action'' (1980 fil ...

; relations between denominational leaders are now very cordial. Unlike the relationship between the hierarchies of the different churches, however, some communal tensions remain.

The association between football and displays of sectarian behaviour by some fans has been a source of embarrassment and concern to the management of certain clubs. The bitter rivalry between Celtic and Rangers in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, known as the Old Firm

The Old Firm is the collective name for the Scottish football clubs Celtic and Rangers, which are both based in Glasgow. The two clubs are by far the most successful and popular in Scotland, and the rivalry between them has become deeply em ...

, is known worldwide for its sectarian dimension. Celtic was founded by Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

immigrants and Rangers has traditionally been supported by Unionists and Protestants. Sectarian tensions can still be very real, though perhaps diminished compared with past decades. Perhaps the greatest psychological breakthrough was when Rangers signed Mo Johnston

Maurice John Giblin Johnston (born 13 April 1963) is a Scottish football player and coach. Johnston, who played as a forward, started his senior football career with Partick Thistle in 1981. He moved to Watford in 1983, where he scored 23 leag ...

(a Catholic) in 1989. Celtic, on the other hand, have never had a policy of not signing players due to their religion, and some of the club's greatest figures have been Protestants.

From the 1980s the UK government passed several acts that had provisions concerning sectarian violence. These included the Public Order Act 1986, which introduced offences relating to the incitement of racial hatred, and the Crime and Disorder Act 1998

The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 (c.37) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act was published on 2 December 1997 and received Royal Assent in July 1998. Its key areas were the introduction of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders, Sex ...

, which introduced offences of pursuing a racially aggravated course of conduct that amounts to harassment of a person. The 1998 Act also required courts to take into account where offences are racially motivated, when determining sentence. In the twenty-first century the Scottish Parliament legislated against sectarianism. This included provision for religiously aggravated offences in the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003. The Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Can ...

strengthened statutory aggravations for both racially and religiously motivated hate crimes. The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012

The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012 was an Act of the Scottish Parliament which created new criminal offences concerning sectarianism, sectarian behaviour at association football, football games ...

, criminalised behaviour which is threatening, hateful, or otherwise offensive at a regulated football match including offensive singing or chanting. It also criminalised the communication of threats of serious violence and threats intended to incite religious hatred.

The Catholic community in Scotland was once largely working-class. In recent years, the situation has changed markedly: many Catholics can be found in what were called the professions, and it is now unremarkable for Catholics to be occupying posts in the judiciary or in national politics. In 1999, the Rt Hon John Reid MP became the first Catholic to hold the office of Secretary of State for Scotland. His succession by the Rt Hon Helen Liddell

Helen Lawrie Liddell, Baroness Liddell of Coatdyke PC (' Reilly; born 6 December 1950) is a British politician and life peer who served as Secretary of State for Scotland from 2001 to 2003 and British High Commissioner to Australia from 2005 to ...

MP in 2001 attracted considerably more media comment that she was the first woman to hold the post than that she was the second Catholic. Also notable was the appointment of Louise Richardson

Dame Louise Mary Richardson (born 8 June 1958 ) is an Irish political scientist whose specialist field is the study of terrorism. In January 2016 she became the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford, having formerly served as the Principa ...

to the University of St. Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

as its principal and vice-chancellor. St Andrews is the third oldest university in the Anglosphere. Richardson, a Catholic, was born in Ireland and is a naturalised United States citizen. She is the first woman to hold that office and first Catholic to hold it since the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Scotland broke with the Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterian in its outlook. It was part of the wider European Protestant Refor ...

.

The Catholic Church recognises the separate identities of Scotland and England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

. The church in Scotland is governed by its own hierarchy and bishops' conference, not under the control of English bishops. In more recent years, for example, there have been times when it was especially the Scottish bishops who took the floor in the United Kingdom to argue for Catholic social and moral teaching. The presidents of the bishops' conferences of England and Wales, Scotland, and Ireland meet formally to discuss "mutual concerns", though they are separate national entities. "Closer cooperation between the presidents can only help the Church's work", a spokesman noted.

Organisation

There are four entities that encompass Scotland, England, and Wales.

* The

There are four entities that encompass Scotland, England, and Wales.

* The Bishopric of the Forces

The Bishopric of the Forces (in Great Britain) is a Latin Church military ordinariate of the Catholic Church which provides chaplains to the British Armed Forces based in the United Kingdom and their overseas postings.

It is directly exempt ...

serves all members of her majesty's military and naval forces throughout the world, including those stationed on bases in Scotland.

* The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham

The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham in England and Wales is a personal ordinariate in the Latin Church of the Catholic Church immediately exempt, being directly subject to the Holy See. It is within the territory of the Catholic B ...

is a jurisdiction equivalent to a diocese for former Anglicans received into the full communion of the Catholic Church and their families. It has faculty to celebrate a distinct variant of the Roman Rite based on the Anglican Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

.

* The Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy of the Holy Family of London

The Eparchy of the Holy Family of London ( uk, Єпархія Пресвятої Родини у Лондоні; la, Eparchia Sanctae Familiae Londiniensis) is the only Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church ecclesiastical territory or eparchy of the ...

serves members of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, a ''sui juris'' ritual church of Byzantine Rite that is part of the larger Catholic Church.

* The Syro-Malabar Catholic Eparchy of Great Britain serves members of the Syro-Malabar Church

lat, Ecclesia Syrorum-Malabarensium mal, മലബാറിലെ സുറിയാനി സഭ

, native_name_lang=, image = St. Thomas' Cross (Chennai, St. Thomas Mount).jpg

, caption = The Mar Thoma Nasrani Sl ...

.

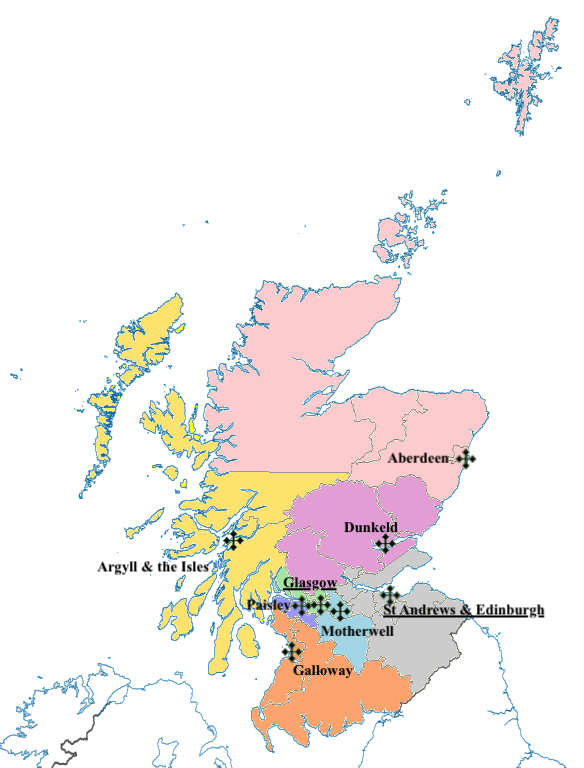

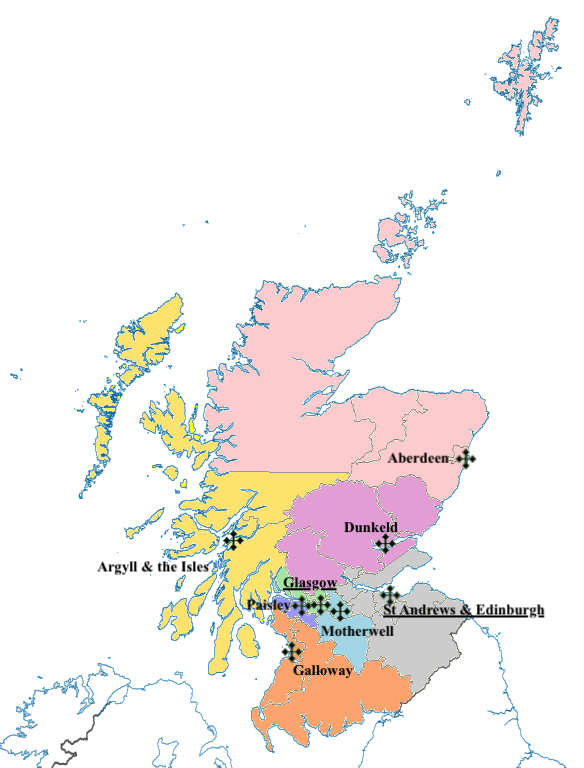

There are two Catholic archdioceses and six diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associa ...

s in Scotland; total membership is 841,000:

The Bishopric of the Forces and the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham are directly subject to the Holy See. The Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy of the Holy Family of London and the Syro-Malabar Catholic Eparchy of Great Britain was subject to their own metropolitans, major archbishops, and major archiepiscopal synods.

21st century

Between 1982 and 2010, the proportion of Scottish Catholics dropped 18%, baptisms dropped 39%, and Catholic church marriages dropped 63%. The number of priests also dropped. Between the

Between 1982 and 2010, the proportion of Scottish Catholics dropped 18%, baptisms dropped 39%, and Catholic church marriages dropped 63%. The number of priests also dropped. Between the 2001 UK Census

A nationwide census, known as Census 2001, was conducted in the United Kingdom on Sunday, 29 April 2001. This was the 20th UK census and recorded a resident population of 58,789,194.

The 2001 UK census was organised by the Office for National ...

and the 2011 UK Census, the proportion of Catholics remained steady while that of other Christians denominations, notably the Church of Scotland dropped.

In 2001, Catholics were a minority in each of Scotland's 32 council areas but in a few parts of the country their numbers was close to those of the official Church of Scotland. The most Catholic part of the country is composed of the western Central Belt council areas near Glasgow. In Inverclyde

Inverclyde ( sco, Inerclyde, gd, Inbhir Chluaidh, , "mouth of the Clyde") is one of 32 council areas used for local government in Scotland. Together with the East Renfrewshire and Renfrewshire council areas, Inverclyde forms part of the hist ...

, 38.3% of persons responding to the 2001 UK Census reported themselves to be Catholic compared to 40.9% as adherents of the Church of Scotland. North Lanarkshire

North Lanarkshire ( sco, North Lanrikshire; gd, Siorrachd Lannraig a Tuath) is one of 32 council areas of Scotland. It borders the northeast of the City of Glasgow and contains many of Glasgow's suburbs and commuter towns and villages. It als ...

also already had a large Catholic minority at 36.8% compared to 40.0% in the Church of Scotland. Following in order were West Dunbartonshire

West Dunbartonshire ( sco, Wast Dunbairtonshire; gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Breatann an Iar, ) is one of the 32 local government council areas of Scotland. The area lies to the west of the City of Glasgow and contains many of Glasgow's commuter to ...

(35.8%), Glasgow City (31.7%), Renfrewshire

Renfrewshire () ( sco, Renfrewshire; gd, Siorrachd Rinn Friù) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland.

Located in the west central Lowlands, it is one of three council areas contained within the boundaries of the historic county of Re ...

(24.6%), East Dunbartonshire

East Dunbartonshire ( sco, Aest Dunbartanshire; gd, Siorrachd Dhùn Bhreatainn an Ear) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It borders the north of Glasgow and contains many of the affluent areas to the north of the city, including Bea ...

(23.6%), South Lanarkshire (23.6%) and East Renfrewshire

East Renfrewshire ( sco, Aest Renfrewshire; gd, Siorrachd Rinn Friù an Ear) is one of 32 council areas of Scotland. Until 1975, it formed part of the county of Renfrewshire for local government purposes along with the modern council areas ...

(21.7%).

In 2011, Catholics outnumbered adherents of the Church of Scotland in several council areas, including North Lanarkshire, Inverclyde, West Dunbartonshire, and the most populous one: Glasgow City.

Between the two censuses, numbers in Glasgow with no religion rose significantly while those noting their affiliation to the Church of Scotland dropped significantly so that the latter fell below those that identified with an affiliation to the Catholic Church.

At a smaller geographic scale, one finds that the two most Catholic parts of Scotland are: (1) the southernmost islands of the Western Isles

The Outer Hebrides () or Western Isles ( gd, Na h-Eileanan Siar or or ("islands of the strangers"); sco, Waster Isles), sometimes known as the Long Isle/Long Island ( gd, An t-Eilean Fada, links=no), is an island chain off the west coast ...

, especially Barra and South Uist, populated by Gaelic-speaking Scots of long-standing; and (2) the eastern suburbs of Glasgow, especially around Coatbridge

Coatbridge ( sco, Cotbrig or Coatbrig, gd, Drochaid a' Chòta) is a town in North Lanarkshire, Scotland, about east of Glasgow city centre, set in the central Lowlands. Along with neighbouring town Airdrie, North Lanarkshire, Airdrie, Coatbrid ...

, populated mostly by the descendants of Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

immigrants.

According to the 2011 UK Census, Catholics comprise 16% of the overall population, making it the second-largest church after the Church of Scotland (32%).

Along ethnic or racial lines, Scottish Catholicism was in the past, and has remained at present, predominantly White or light-skinned in membership, as have always been other branches of Christianity in Scotland. Among respondents in the 2011 UK Census who identified as Catholic, 81% are White Scots, 17% are Other White (mostly other British or Irish), 1% is either Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British, and an additional 1% is either mixed-race or from multiple ethnicities; African; Caribbean or black; or from other ethnic groups.

In recent years the Catholic Church in Scotland has experienced bad publicity due to statements made by bishops in defence of traditional Christian morality

Christian ethics, also known as moral theology, is a multi-faceted ethical system: it is a virtue ethic which focuses on building moral character, and a deontological ethic which emphasizes duty. It also incorporates natural law ethics, whic ...

and in criticism of secular and liberal ideology. Joseph Devine

Joseph Devine (7 August 1937, Kirkintilloch – 23 May 2019) was the Roman Catholic Bishop of Motherwell in Scotland.

He was educated at St Ninian's School, Kirkintilloch, St. Mary's College, Blairs and St. Peter's College, Cardross

Card ...

, Bishop of Motherwell, came under fire after alleging that the "gay lobby" were mounting "a giant conspiracy" to completely destroy Christianity. Criticism was also levelled at perceived intransigence on joint faith schools and threats to withdraw acquiescence unless guarantees of separate staff rooms, toilets, gyms, visitor, and pupil entrances were not met.

In 2003, a Catholic church spokesman branded sex education as "pornography" and now disgraced Cardinal Keith O'Brien claimed plans to teach sex education in pre-schools amounted to "state-sponsored sexual abuse of minors."

There has also been even worse publicity related to the sexual abuse of minors. In 2016, a headteacher and teacher of the St Ninian's Orphanage, Falkland, Fife were sentenced for abuse at the orphanage from 1979 to 1983 when it was run by the Congregation of Christian Brothers

The Congregation of Christian Brothers ( la, Congregatio Fratrum Christianorum; abbreviated CFC) is a worldwide religious community within the Catholic Church, founded by Blessed Edmund Ignatius Rice, Edmund Rice.

Their first school was opened i ...

. Fr John Farrell the last headteacher there was sentenced to five years imprisonment. Paul Kelly, a teacher, was sentenced to ten years. More than 100 charges involving 35 boys were made regarding the orphanage, which had been closed down in 1983. In 2019, it emerged that the Superior General of the Christian Brothers, approved the placement of Farrell at St Ninian's despite previous reports of interfering with boys at a South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

n boarding school where it was recommended by the African provincial that Farrell should never be placed in a boarding school in the future.

Roughly half of Catholic parishes in the West of Scotland were closed or merged because of a priest shortage and over half have closed in the Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburgh

The Archdiocese of Saint Andrews & Edinburgh ( la, Archidioecesis Sancti Andreae et Edimburgensis) is an archdiocese of the Latin Church of the Catholic Church in Scotland. It is the metropolitan see of the province of Saint Andrews and Edinbu ...

.

In early 2013, Scotland's most senior cleric, Cardinal Keith O'Brien, resigned after allegations of sexual misconduct were made against him and partially admitted. Subsequently, allegations were made that several other cases of alleged sexual misconduct took place involving other priests.

See also

* Catholic Church by country *Catholic Church hierarchy

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church consists of its bishop (Catholic Church), bishops, Priesthood (Catholic Church), priests, and deacons. In the Catholic ecclesiology, ecclesiological sense of the term, "hierarchy" strictly means the "holy or ...

* Catholic Church in England and Wales

* Catholic Church in Ireland

, native_name_lang = ga

, image = Armagh, St Patricks RC cathedral.jpg

, imagewidth = 200px

, alt =

, caption = St Patrick's Cathedral, Armagh.

, abbreviation =

, type ...

(includes Northern Ireland)

* Catholic Church in the United Kingdom

* List of Catholic churches in Scotland

* List of Catholic schools in Scotland

In the United Kingdom, there are many 'local authority maintained' (i.e. state funded) Roman Catholic schools. These are theoretically open to pupils of all faiths or none, although if the school is over-subscribed priority will be given to Roma ...

* List of monastic houses in Scotland

List of monastic houses in Scotland is a catalogue of the abbeys, priories, friaries and other monastic religious houses of Scotland.

In this article alien houses are included, as are smaller establishments such as cells and notable monasti ...

* Lists of patriarchs, archbishops, and bishops

This is a directory of patriarchs, archbishops, and bishops across various Christian denominations. To find an individual who was a bishop, see the most relevant article linked below or :Bishops.

Lists

Catholic

* Bishop in the Catholic Chur ...

* Catholicism in the Western Isles

* Carfin Grotto

* Scottish Catholic Observer

The ''Scottish Catholic Observer'' was Scotland's only national Catholic newspaper, founded in 1885. It ceased publication in 2020. It featured news of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland as well as regular international church news and repor ...

* '' The World, the Flesh, and Father Smith'', a novel about the life of a Scottish Catholic priest

References

External links

Bishops' Conference of Scotland

(selection of archive films relating to Catholicism in Scotland) {{DEFAULTSORT:Catholic Church In Scotland

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...